Abstract

To address the challenge of user behavior prediction on artificial intelligence (AI)-based online education platforms, this study proposes a novel ensemble model. The model combines the strengths of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Multi-Head Attention Mechanism (MHAM), Weighted Random Forest (WRF), and Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN), forming an integrated architecture that enhances WRF and BPNN with CNN and MHAM. Experimental results demonstrate that the improved BPNN model, when combined with WRF, outperforms individual models in predicting user behavior. Specifically, the integrated model achieves a prediction accuracy of 92.3% on the test dataset—approximately 5% higher than that of the traditional BPNN. For imbalanced datasets, it attains a recall rate of 89.7%, significantly surpassing the unweighted random forest’s 82.4%. The model also achieves an F1-score of 90.8%, reflecting strong overall performance in terms of both precision and recall. Overall, the proposed method effectively leverages the classification capabilities of WRF and the nonlinear fitting power of BPNN, substantially enhancing the accuracy and reliability of user behavior prediction, and offering valuable support for optimizing AI-driven online education platforms.

Keywords: User behavior prediction, Weighted random forest, Back propagation neural network, Online education, Resource configuration

Subject terms: Mathematics and computing, Applied mathematics, Computational science, Computer science, Information technology, Pure mathematics, Scientific data, Software, Statistics

Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving information age, online education platforms have emerged as a widely adopted educational model. Their convenience and flexibility have attracted a vast number of students and educators, resulting in a large and complex user base1,2. As user numbers and activity levels continue to grow, the challenge of accurately predicting user behavior has become increasingly urgent. Effective behavior prediction is essential for optimizing learning paths, enhancing user experience, and improving learning outcomes on these platforms3–6. Accurate user behavior prediction plays a critical role in helping platform administrators understand users’ learning habits, interests, and progress. This understanding supports personalized recommendations, efficient resource allocation, and teaching effectiveness evaluation7,8.

Traditional methods—such as linear regression and decision trees—perform adequately on simple, linear datasets. However, they often fall short when applied to the complex and diverse behavioral data found on online education platforms9–11. These limitations are particularly evident when handling high-dimensional, nonlinear, and imbalanced data, where traditional models struggle to extract meaningful insights, resulting in low prediction accuracy and weak robustness12,13. The advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in machine learning and deep learning, has introduced new tools and methods for user behavior prediction14. Among them, the Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) has gained considerable attention due to its strong nonlinear mapping capabilities, along with its self-learning and adaptive properties15,16.

Although the BPNN performs well in predicting user behavior, it faces limitations when handling imbalanced data17. On online education platforms, user behavior data is often highly imbalanced—most behaviors are concentrated around a few common activities, while more critical actions, such as course completion or deep engagement, occur far less frequently. Training a BPNN directly on such data can lead to poor prediction accuracy for these less common but important behaviors, ultimately reducing the overall effectiveness of the model 18, 19. To address this issue, this study introduces a Weighted Random Forest (WRF) as a preprocessing step. The WRF is used to perform initial classification and assign weights to the user behavior data. Building on this, a new predictive model is proposed by combining the strengths of WRF and BPNN. This hybrid approach effectively tackles both data imbalance and nonlinear relationships present in user behavior data on online education platforms. The proposed model significantly improves prediction accuracy and reliability. It also provides valuable support for platform optimization and the delivery of personalized educational services.

Research objectives

This study addresses the challenge of user behavior prediction on AI-driven online education platforms by proposing an improved BPNN model enhanced with a WRF. The primary goal is to overcome the issue of data imbalance in user behavior datasets, improve the recognition of minority classes through ensemble learning techniques, and leverage the nonlinear fitting capability of BPNN to develop a more accurate and reliable predictive model. The proposed integrated model combines the strengths of WRF and BPNN to enable efficient prediction and analysis of user behavior. It effectively mitigates the impact of data imbalance and enhances predictive performance, offering strong support for the optimization and advancement of online education platforms.

The structure of the study is as follows: “Research objectives” section presents the introduction, outlining the research background, motivation, and objectives, along with a summary of the paper’s organization. “Literature review” section provides a literature review, exploring the current applications and limitations of ensemble learning and deep learning techniques in user behavior prediction. This section analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of existing approaches and establishes the theoretical foundation for the proposed integrated model. “Research methodology” section details the study methodology, describing the construction and optimization of the WRF model, BPNN model, and the improved integrated model. “Experimental design and performance evaluation” section focuses on experimental design and performance evaluation, including data collection, experimental setup, parameter configuration, and evaluation metrics. It also presents experimental results and a comparative analysis between the proposed model and several baseline algorithms. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes the study by summarizing the study contributions and outlining potential directions for future work.

Literature review

In recent years, the rapid development of AI has significantly expanded the application of machine learning and neural networks across various domains—particularly in predicting user behavior on online education platforms. This topic has garnered global attention, with researchers striving to extract and analyze large-scale user behavior data to build accurate prediction models that support platform optimization and enhance the learning experience. For example, Aydoğdu proposed a prediction model based on Support Vector Machines (SVM) to forecast student performance in online courses20. Chen et al. applied the random forest algorithm to address user behavior prediction challenges on educational platforms21. Disha et al. introduced the WRF model, which improved the identification of minority classes by assigning different weights to various sample categories22. Khan et al. explored the application of BPNNs for behavior prediction23but noted issues such as gradient vanishing and local minima during training, which negatively affected model stability and convergence speed.

To overcome these challenges, Shirabayashi et al. proposed a hybrid model that combined Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with traditional BPNN to enhance the extraction of local features from user behavior data24. Alshurideh et al. studied ensemble learning approaches and integrated multiple base models to improve prediction performance25. While this method effectively balanced accuracy and recall, it also increased the complexity of model design and optimization, which made implementation more difficult. Ray et al. adopted a transfer learning approach, utilized pre-trained models and datasets, and enhanced the learning capability of new models26. Although this method partially addressed the issue of data scarcity, its effectiveness depended heavily on the similarity between source and target domains, which introduced uncertainty in practical applications.

Traditional machine learning methods play a central role in the early stages of user behavior prediction research. However, the emergence of deep learning has revitalized the field. Models based on deep neural networks—such as deep belief networks (DBNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and their variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent units (GRUs)—have shown strong capabilities in feature extraction and in capturing complex data patterns. These models have achieved significant success in user behavior prediction tasks. For example, Onan used decision trees and Naive Bayes classifiers to predict students’ academic outcomes, demonstrating that simple classification algorithms performed well on small-scale datasets. However, such traditional approaches often fell short in terms of accuracy and generalization when applied to high-dimensional, complex user behavior data27. In contrast, Lyu et al. proposed a Deep Knowledge Tracing (DKT) model based on LSTM, which substantially improved prediction accuracy28. Similarly, Hu et al. employed CNNs to extract temporal features from user behavior data, further validated the effectiveness of deep learning in processing complex data29.

Class imbalance remains a major challenge in predicting user behavior on online education platforms. Devan et al. addressed this issue by applying an XGBoost model, which improved minority class recognition through class weight adjustments and learning rate tuning30. Manokaran et al. explored the use of WRF for handling imbalanced data—a method that was conceptually similar to the approach proposed in this study. However, their model did not fully utilize the nonlinear fitting strengths of deep learning techniques31. In recent years, the use of multimodal data has emerged as a leading trend in user behavior analysis. For instance, Zhang et al. employed graph neural networks (GNNs) to integrate interaction data, learning logs, and textual content. This approach enabled multi-level modeling of user behavior and led to significant improvements in prediction accuracy32. Li et al. investigated the transferability of user behavior prediction models across different educational platforms. Their findings emphasized the importance of model stability and robustness under varying data distributions, providing valuable insights for improving user experience on online education platforms33.

Yan and Au used students’ course grades as predictive labels and employed a classical three-layer feedforward neural network as the machine learning model. They trained the model using the scaled conjugate gradient algorithm and conducted Pearson correlation analysis to explore the relationship between course performance and various student features34. The results showed that the number of days students accessed the platform had the strongest correlation with course grades, followed by the number of clicks. Connection time showed a weaker association, while age and gender had the lowest correlation with academic outcomes. Amin et al. applied an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to analyze and classify user behavior data on MOOC platforms. Their goal was to better understand learners’ engagement patterns and educational needs35. The model enabled the identification of user categories such as highly engaged users, low-engagement users, and potential dropouts. This classification approach supported the delivery of personalized learning experiences and targeted interventions, ultimately enhancing user satisfaction and learning outcomes. Talebi et al. focused on predicting student dropout in MOOCs by introducing a deep learning-based model36. They used LSTM networks to automatically learn temporal features from behavioral data. This approach allowed for more accurate prediction of dropout risk. Compared with traditional methods, the LSTM model was more effective in capturing dynamic changes and long-term dependencies in student behavior—key factors in identifying dropout trends.

Despite the promising results of ensemble learning and deep learning in user behavior prediction, both approaches presented notable challenges in real-world applications. Ensemble methods, while improving accuracy and robustness, often required significant computational resources and prolonged training times due to model complexity. In addition, their limited interpretability made it difficult to understand the rationale behind predictions. Deep learning models also encountered issues such as gradient vanishing and local optima, which compromised training stability and convergence speed. Moreover, their dependency on large, labeled datasets and lack of transparency further restricted their practical deployment in certain scenarios.

In summary, previous research has made considerable progress in user behavior prediction but still faces several limitations. For instance, SVM and traditional Random Forest models perform poorly when handling imbalanced data. While a single BPNN can model nonlinear relationships, it is prone to getting stuck in local optima during training. Although hybrid and ensemble learning models achieve strong predictive performance, they often involve high implementation complexity. Additionally, the effectiveness of transfer learning is constrained by the similarity between the source and target domains, introducing uncertainty in practical applications. The integrated model proposed in this study addresses these issues by combining the classification strength of WRF with the nonlinear fitting capabilities of BPNN. It further incorporates a Multi-Head Attention Mechanism (MHAM) to dynamically weight features. This approach effectively tackles challenges such as imbalanced data and complex pattern recognition in online education user behavior prediction. Compared with existing methods, this study is the first to integrate WRF with MHAM and optimize model parameters through cross-validation, resulting in significantly improved prediction accuracy.

Research methodology

WRF model

On AI-powered online education platforms, the diversity and complexity of user behavior demand prediction models with high accuracy and strong generalization capabilities37. However, traditional deep forest models face limitations when handling imbalanced datasets. To address this issue and enhance prediction accuracy, this study proposes a Weighted Deep Forest Model—an ensemble learning approach that assigns different weights to the outputs of multiple cascaded decision trees for more precise user behavior prediction.

The proposed model comprises several cascaded decision trees, each independently classifying the input data. Unlike traditional random forests, which rely on a simple majority voting mechanism, the weighted deep forest integrates predictions using a weighted average strategy. This approach determines weights based on three key factors:

Node Purity in Decision Trees: The model calculates the total purity of non-leaf nodes. Nodes with lower purity are more effective in classifying data and are therefore assigned higher weights.

Feature Importance via Gradient Boosting: Features deemed more important through the gradient boosting method play a greater role in data segmentation. Decision trees that rely heavily on such features are given higher weights.

Category Distribution in Leaf Nodes: The model evaluates the proportion of each class within the leaf nodes. A class that dominates a leaf node is considered more reliable, and its corresponding prediction receives a higher weight38–40.

The weight assigned to each decision tree is computed using Eq. (1):

|

1 |

In Eq. (1),  represents the weighted sum of node purity.

represents the weighted sum of node purity.  is the importance of features, which is calculated by gradient lifting tree method.

is the importance of features, which is calculated by gradient lifting tree method.  is to count the number of samples of each category in each leaf node, indicating the category distribution. Equation (2) shows the calculation of

is to count the number of samples of each category in each leaf node, indicating the category distribution. Equation (2) shows the calculation of  :

:

|

2 |

In Eq. (2),  is the weight of the node.

is the weight of the node.  is the information entropy of the node, and

is the information entropy of the node, and  is the sum operation41–43. Figure 1 shows the training process of the weighted depth forest model.

is the sum operation41–43. Figure 1 shows the training process of the weighted depth forest model.

Fig. 1.

Training process of weighted depth forest model.

Design and training of BPNN model

BPNN is a multi-layer feedforward neural network, which is trained by error backpropagation44,45. Figure 2 shows the structure of BPNN model.

Fig. 2.

BPNN model structure.

Figure 2 includes an input layer, a hidden layer and an output layer. Each layer consists of several nodes (neurons), which are connected by weighted connections. The working principle of the network is to propagate the input data forward to the output layer, and then adjust the weight reversely according to the output error46,47. Equations (3) and (4) show the calculation of forward propagation algorithm:

|

3 |

|

4 |

The input data  passes through the weighted summation and activation function

passes through the weighted summation and activation function  of the hidden layer.

of the hidden layer.  is the weight connecting the input layer and the hidden layer.

is the weight connecting the input layer and the hidden layer.  is the bias term of the hidden layer. The output

is the bias term of the hidden layer. The output  of the hidden layer passes through the weighted sum of the output layer and the activation function

of the hidden layer passes through the weighted sum of the output layer and the activation function  to get the final output

to get the final output  .

.  is the weight connecting the hidden layer and the output layer.

is the weight connecting the hidden layer and the output layer.  is the bias term of the output layer. According to the error between the prediction result and the actual label, the backpropagation algorithm adjusts the weights in the network layer by layer from the output layer to the input layer to minimize the overall error48. The error

is the bias term of the output layer. According to the error between the prediction result and the actual label, the backpropagation algorithm adjusts the weights in the network layer by layer from the output layer to the input layer to minimize the overall error48. The error  of the output layer is calculated, as shown in Eq. (5):

of the output layer is calculated, as shown in Eq. (5):

|

5 |

is the target value.

is the target value.  is the derivative of the activation function

is the derivative of the activation function  of the output layer. Equation (6) for calculating the error of hidden layer:

of the output layer. Equation (6) for calculating the error of hidden layer:

|

6 |

is the derivative of the hidden layer activation function

is the derivative of the hidden layer activation function  . The weights and offsets are updated as shown in Eqs. (7)–(10):

. The weights and offsets are updated as shown in Eqs. (7)–(10):

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

is the learning rate.

is the learning rate.  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  respectively represent the updated weight and offset. This updating process helps to minimize the overall loss function through the gradient descent rule, thus optimizing the prediction performance of the neural network49.

respectively represent the updated weight and offset. This updating process helps to minimize the overall loss function through the gradient descent rule, thus optimizing the prediction performance of the neural network49.

Construction and optimization of integrated model

To address the problem of user behavior prediction on AI-powered online education platforms, this study proposes an improved ensemble model that integrates a WRF with a BPNN. By combining the strengths of both WRF and BPNN, the model enhances the accuracy and robustness of user behavior prediction. First, the WRF is employed to classify user behavior data. Through ensemble learning, WRF effectively handles class imbalance and produces classification results along with corresponding weights for each sample. These classification results, including both preliminary class information and sample weights, are then used as input features for the BPNN. This enables the neural network to directly leverage the classification capability of WRF, providing richer and more precise input data. After receiving the WRF outputs, the BPNN is trained using the backpropagation algorithm. During training, the network’s weights and biases are updated by considering the sample weight information to minimize a weighted loss function. This approach effectively integrates the classification advantages of WRF with the nonlinear fitting capability of BPNN, allowing the model to better adapt to the complex characteristics of user behavior data. Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the ensemble model based on WRF and BPNN.

Fig. 3.

An ensemble model based on WRF and BPNN.

In order to consider the weight information of the WRF, the loss function adopts the weighted cross entropy loss function. The weighted cross entropy loss function can effectively reflect the importance of different categories of samples and improve the influence of a few categories in the training process. Equation (11) shows the calculation:

|

11 |

In Eq. (11),  represents the weight of sample

represents the weight of sample  .

.  represents the actual label of sample

represents the actual label of sample  .

.  represents the output probability of neural network prediction. The detailed definitions of the symbols used in this study are listed in Table 1.

represents the output probability of neural network prediction. The detailed definitions of the symbols used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols.

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

|

Weighted sum of the purity of non-leaf nodes in the decision tree |

|

Feature importance calculated using the gradient boosting tree method |

|

Distribution of sample categories within each leaf node |

|

Weight of sample ii |

|

True label of sample ii |

|

Predicted probability output by the neural network for sample ii |

|

Activation function of the hidden layer |

|

Activation function of the output layer |

|

Learning rate |

|

Error term at the output layer |

|

Error term at the hidden layer |

|

Weight between input layer and hidden layer |

|

Weight between hidden layer and output layer |

|

Bias of the hidden layer |

|

Bias of the output layer |

|

Weighted cross-entropy loss function |

|

Output of the hidden layer |

|

Summation operator |

|

Weighted sum of purity across all non-leaf nodes in the decision tree |

To further improve user behavior prediction on AI online education platforms, this study proposes a novel integrated model that combines CNN, MHAM, WRF, and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN). The model is designed to efficiently extract features from user behavior data using CNN, while MHAM assigns dynamic weights to these features to enhance the model’s perception and decision-making capabilities. Specifically, CNN captures local features from user behavior data through multiple convolutional layers. This enables the model to detect complex patterns and structures, which are crucial for accurate user behavior prediction in online education. Following the convolution layers, MHAM fuses the extracted features by dynamically weighting each one. This attention mechanism helps the model focus more on features that significantly impact prediction. MHAM processes multiple “perspectives” simultaneously, which improves the model’s global learning and representation abilities. Building on this, WRF classifies and weights the user behavior data. Using an ensemble learning approach, WRF applies weighted voting across multiple decision trees to address class imbalance. It dynamically adjusts the weight of each tree based on prediction accuracy, feature importance, and class distribution, thereby enhancing recognition of minority user behaviors. The outputs from WRF serve as input features for the CNN and MHAM components. These features then undergo nonlinear fitting through BPNN. The BPNN trains on WRF outputs and optimizes the network by adjusting weights via backpropagation. This integration results in more accurate user behavior prediction.

The training process of the integrated model proceeds as follows. First, the CNN extracts features from the original user behavior data, producing a high-dimensional feature map through its convolutional layers. Next, this feature map is fed into the MHAM module, where features are weighted and fused to generate richer representations. The fused features are then classified by the WRF, which outputs both the predicted category and corresponding weight for each data point. Finally, the WRF output serves as input to the BPNN for training and optimization. By minimizing a weighted cross-entropy loss function and updating network weights via backpropagation, the BPNN enhances the model’s prediction accuracy and robustness.

This study improved the model in several key ways. First, the use of CNN went beyond simple feature extraction. It was specifically optimized to handle the high-dimensional and locally dependent nature of user behavior data on online education platforms. The carefully designed convolution and pooling layers enabled extraction of distinctive local features from raw data, which are crucial for capturing user behavior patterns under different contexts. For instance, users’ login frequency and learning duration often exhibit local dependencies over time and space, and CNN’s local receptive fields effectively identify these patterns. Second, the MHAM in the integrated model offered unique advantages for processing user behavior data. Such data not only includes behavioral metrics like learning time and course clicks but also contains multi-dimensional interaction information. Each feature contributes differently to the prediction task, with complex nonlinear relationships among them. By incorporating MHAM, the model dynamically assigned varying weights to features during training, prioritizing those most influential to prediction accuracy. This significantly enhanced the model’s performance on complex data. Third, the WRF model addressed the common problem of data imbalance in online education platforms. Typically, user behavior data are heavily skewed, with most users being inactive and only a small fraction being highly active or potential long-term payers. WRF tackled this by incorporating sample weights into the decision tree training, improving classification performance especially for minority user groups. Finally, the BPNN performed nonlinear fitting on the WRF outputs, enabling the integrated model not only to classify different user behavior types accurately but also to further optimize performance through error backpropagation. This process helped reduce overfitting and improved the model’s generalization ability.

Experimental design and performance evaluation

Datasets collection

The user behavior dataset used in this study was collected from multiple well-known online education platforms, including the international platform Coursera and the domestic platform NetEase Cloud Classroom.

The Coursera dataset covers user activity from 2019 to 2022 and includes detailed logs of various learning-related interactions, such as course browsing, video viewing, quiz submissions, and forum participation. These multidimensional records provide a comprehensive view of users’ learning behaviors and habits. In contrast, the data from NetEase Cloud Classroom spans from June 2020 to January 2023 and features a diverse user base, including high school students, university students, and working professionals across different age groups and educational backgrounds. This dataset not only captures core learning behaviors—such as course selection and study duration—but also includes user interaction data such as comments, likes, and discussions, offering rich, multidimensional insights for behavior analysis.

The dataset was collected through direct collaboration with the online education platforms and constitutes proprietary experimental data. Rigorous preprocessing and cleaning procedures were applied to ensure data quality and usability. In total, the dataset contains approximately 200,000 samples with multiple feature dimensions, including user demographics, course selection, study time, and interaction behaviors—allowing for a comprehensive representation of user activity on online education platforms. To safeguard user privacy and ensure data anonymity, the study strictly adhered to data protection regulations and privacy standards during data collection. All user information was encrypted to prevent any disclosure of personal data. During preprocessing, a variety of methods were employed: missing values were handled using mean imputation or interpolated based on behavioral correlations; outliers were detected and removed using box plot techniques; and all numerical features were standardized to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. This normalization allowed different features to be compared on the same scale, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of model training. Through these preprocessing steps, data quality was significantly improved, ensuring the stability and performance of the predictive models.

Experimental environment

The experiments in this study were conducted on a high-performance computing server equipped with multiple GPU accelerators to support the training and validation of deep learning models. Python was used as the primary programming language, with TensorFlow and Keras frameworks employed to construct and train the BPNN model. Additionally, the WRF model was implemented using the Random Forest Classifier from the Scikit-learn library, with custom adjustments made to incorporate weighting mechanisms.

Parameters setting

To optimize the improved BPNN model based on the WRF framework, this study carefully configured several key parameters. Table 2 presents the main parameters and their corresponding values used during model training. The number of decision trees in the WRF model was set to 100, based on extensive experimentation and cross-validation. This number was chosen to strike a balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. While increasing the number of trees can reduce variance and improve stability, it also leads to diminishing returns and higher computational costs beyond a certain point. Empirical results showed that 100 trees offered sufficient ensemble diversity to achieve high prediction accuracy without introducing excessive computational overhead. Moreover, this configuration helped mitigate overfitting in the presence of imbalanced data by enhancing model robustness. The maximum depth of each decision tree was set to 10, a parameter that directly influences model complexity. Deeper trees are capable of capturing more intricate patterns, but they also increase the risk of overfitting, particularly in noisy or limited datasets. Conversely, overly shallow trees may underfit and fail to capture key relationships. After testing various depth values ranging from 5 to 20, a depth of 10 was selected as the optimal setting. This depth offered a balanced trade-off, allowing the model to capture meaningful patterns without overfitting. It also ensured the model remained interpretable—an important factor for understanding user behavior on online education platforms. Other parameters were configured based on best practices in decision tree modeling and the specific characteristics of the user behavior data. For instance, the “gini” criterion was used to measure split quality due to its computational efficiency and effectiveness, especially with moderately balanced datasets. The min_samples_split parameter was set to 2, allowing internal nodes to continue splitting until all leaves reached purity, which is a standard setting in many decision tree implementations.

Table 2.

Key parameters used in model training and their set values.

| Parameter name | Parameter description | Set value |

|---|---|---|

| n_estimators | The number of decision trees in WRF | 100 |

| max_depth | Maximum depth of decision tree | 10 |

| min_samples_split | Minimum number of samples required to segment internal nodes | 2 |

| min_samples_leaf | Minimum number of samples required for leaf nodes | 1 |

| max_features | The maximum number of features to consider when finding the best split | “auto” |

| criterion | The standard used when building the tree, “gini” or “entropy” | “gini” |

| learning_rate | Learning rate in the training process of BPNN | 0.001 |

| hidden_layers | The number of hidden layers in BPNN, in the format of “number of layers _ number of nodes” | “2_50” |

| epochs | The number of iterations in the training process | 200 |

| batch_size | Number of samples used in each iteration | 32 |

| activation_function | Activation function for hidden layer and output layer | “relu” |

| optimizer | An optimizer for updating the model weights | “adam” |

| dropout_rate | Dropout ratio for regularization to prevent over-fitting | 0.2 |

| weight_decay | L2 regularization term, which is used to control the model complexity | 0.001 |

The selection of hyperparameters in deep learning models—such as learning rate, number of hidden layers, dropout rate, and regularization coefficient—is inherently complex and computationally demanding. Although this study carefully determined these values based on experimental results using data from an online education platform, it remains important to discuss the generalizability of these parameters in similar contexts and the associated cost of their selection. In this study, hyperparameters including a learning rate of 0.001, 50 hidden layer nodes, and a regularization coefficient of 0.001 were selected to align with the characteristics of the dataset, which comprised user login data, course interactions, and other behavioral metrics. These settings were chosen to optimize the performance of the integrated WRF-BPNN model for predicting user behavior within the AI-driven online education context. However, these parameter settings may not be universally applicable across all platforms or datasets. Variations in user demographics, engagement patterns, or course content may necessitate different configurations. For example, if a dataset is skewed toward a small group of highly active users, adjustments to the learning rate or the number of hidden layers may be required to prevent overfitting or underfitting. For more diverse user behaviors or larger datasets, more complex architectures—such as deeper networks or larger batch sizes—may be necessary to effectively capture interaction patterns. Conversely, for simpler or smaller datasets, a more lightweight configuration with fewer hidden layers or a lower learning rate may still yield satisfactory results.

Hyperparameter tuning is inherently resource-intensive and can significantly increase the time and computational cost of model training. While methods such as Grid Search and Random Search are commonly used and effective, they become computationally expensive when applied to large datasets or deep learning models with many parameters. In this study, the chosen hyperparameters reflect a balance between model performance and computational feasibility. Initial parameter selection was conducted using Random Search, followed by cross-validation to fine-tune these values, ensuring an optimal trade-off between prediction accuracy and training efficiency. To mitigate the high cost of hyperparameter tuning, future work could explore automated optimization techniques such as Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms. These methods provide more efficient exploration of the hyperparameter space and can significantly reduce computational demands without compromising model performance.

In practical applications, transferring hyperparameters across different datasets or platforms presents another challenge. This study suggests that certain parameters—such as the learning rate and regularization coefficient—tend to be relatively robust across varying data characteristics. However, others, such as the number of hidden layers or the overall network architecture, may require adjustment based on dataset size and behavioral complexity. For large-scale or behaviorally rich datasets, advanced tuning techniques like cross-validation or sensitivity analysis can help identify the most impactful parameters. Incorporating domain knowledge into this process can further improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of hyperparameter selection. In summary, hyperparameter selection is a critical step in model development. In the context of dynamic and diverse datasets—such as those from online education platforms—careful consideration must be given to both the computational cost and generalizability of the chosen parameters.

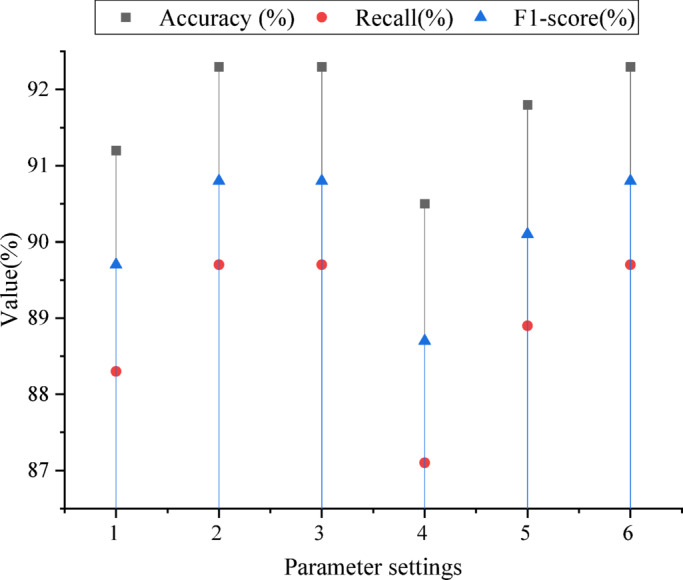

Performance evaluation

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of different hyperparameters on the model’s prediction performance. When the learning rate is reduced from 0.01 to 0.001, the model’s Accuracy, Recall, and F1-score improve to 92.3%, 89.7%, and 90.8%, respectively. This indicates that a lower learning rate helps the model converge more effectively and reduces the risk of overfitting. Additionally, the model performs best when the number of hidden layer nodes is set to 50. Increasing the nodes to 100 leads to a decline in performance, suggesting that excessive model complexity can hinder learning. Furthermore, the model achieves optimal performance with a regularization coefficient of 0.001, highlighting the role of appropriate regularization in enhancing generalization.

Fig. 4.

The influence of different parameters on the prediction results of the model (the abscissa “1” in the figure is learning _ rate = 0.01; “2” is learning _ rate = 0.001; “3” is hidden _ layers = 50; “4” is hidden _ layers = 100; “5” means regularization coefficient = 0.01; “6” is regularization coefficient = 0.001).

Figure 5 shows the performance comparison results among different models. The proposed integrated model performs well in several benchmark models, especially in three important evaluation indexes: Accuracy, Recall and F1-score, which are significantly improved compared with other models. Firstly, in terms of accuracy, the proposed ensemble model (WRF + BPNN + CNN + Attention) reaches 92.3%, which is obviously improved compared with the traditional BPNN (87.3%) and the unweighted random forest (89.2%). In addition, the CNN and LSTM are 90.5% and 90.1% respectively, while the accuracy of extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) is 91.0%. It shows that the integrated model is not only superior to the traditional single model (such as BPNN and unweighted random forest), but also surpasses other deep learning methods, such as CNN, LSTM and XGBoost. This shows that the integration method can better handle complex user behavior data by combining the advantages of different models, thus improving the overall prediction accuracy. In the recall rate, the performance of the proposed integrated model is equally outstanding, reaching 89.7%. This result is obviously higher than other models, especially traditional BPNN (84.1%) and unweighted random forest (82.4%). In addition, the recall rates of CNN, LSTM and XGBoost are 85.3%, 86.2% and 87.5% respectively. Improving the recall rate means that the model can better identify minority samples and reduce the situation of missing detection. The integrated model shows great ability in this respect, especially when dealing with unbalanced data, which can better capture the feature information of minority categories and further improve the practicability and reliability of the model. F1 score, as an indicator of comprehensive consideration of accuracy and recall, directly reflects the overall performance of the model. In terms of F1 score, the score of integrated model reaches 90.8%, which is significantly higher than all benchmark models. The F1 score of traditional BPNN is 85.6%, that of unweighted random forest is 85.6%, that of CNN and LSTM is 87.8% and 88.1%, and that of XGBoost is 89.2%. The integrated model achieved the highest F1 score among all compared models, indicating its strong overall predictive capability by balancing both accuracy and recall. This balanced performance helps avoid the common pitfall of overemphasizing one metric at the expense of the other. Overall, the proposed model demonstrates clear advantages in accuracy, recall, and F1 score, particularly when handling complex user behavior data. It effectively addresses the limitations of traditional models and enhances prediction accuracy. Compared to other advanced deep learning methods such as CNN, LSTM, and XGBoost, the ensemble model—by combining the strengths of WRF, BPNN, and MHAM—offers superior overall performance, improved generalization, and greater application potential.

Fig. 5.

Performance comparison results among different models.

Figure 6 presents the cross-validation results. Increasing the number of folds from 5 to 10 improves the model’s average accuracy, recall, and F1 score to 92.3%, 89.7%, and 90.8%, respectively. However, further increasing the folds to 15 causes a slight decline in performance. This suggests that 10-fold cross-validation offers a good balance, ensuring strong generalization while avoiding over-fitting.

Fig. 6.

Cross-validation results.

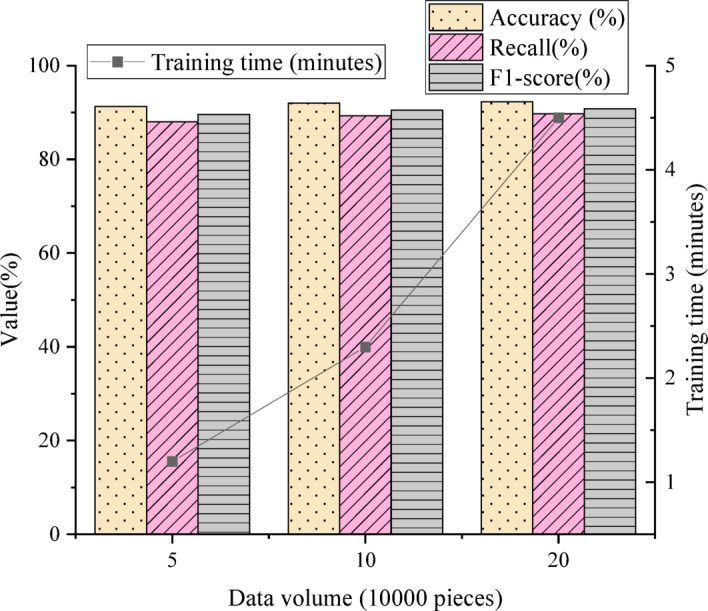

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between training time and predictive performance. As the data volume increases, training time grows linearly, while accuracy, recall, and F1 score also improve. Specifically, when the dataset size rises from 50,000 to 200,000, accuracy increases from 91.3 to 92.3%, recall from 88 to 89.7%, and F1 score from 89.6 to 90.8%. This indicates that larger datasets enhance the model’s predictive ability, but require greater computational resources.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between training time and prediction performance.

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of different user behavior features on the model’s prediction results. Using the correct answer rate as a feature yields the highest accuracy, recall, and F1 score—92.3%, 89.7%, and 90.8%, respectively. This highlights the correct answer rate as a key predictor that significantly enhances model performance. Features like learning time and course clicks also improve the model’s performance, though to a lesser extent. In contrast, interaction frequency has relatively little effect on the model’s accuracy.

Fig. 8.

Influence of user behavior characteristics on prediction results.

Figure 9 compares the proposed improved integrated model with several benchmark algorithms. All experiments were conducted on the same dataset, and multiple evaluation metrics were recorded for each model to assess the superiority and effectiveness of the improved integrated model. The results show that performance differences between the improved WRF-BPNN ensemble model and traditional models like SVM, Neural Networks, and LightGBM are statistically significant. Paired t-tests confirm that the integrated model outperforms others in accuracy, recall, and F1 score, with all p-values below 0.05, indicating strong statistical significance.

Fig. 9.

Performance comparison of different models.

Compared to SVM, the improved integrated model clearly excels at handling nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional data. While SVM performs well on small datasets, its effectiveness decreases with larger, more complex data. In contrast, the integrated model leverages the strengths of both WRF and BPNN to effectively manage large-scale data and capture nonlinear patterns. Against Neural Networks, the integrated model achieves higher recall and F1 scores, particularly in addressing class imbalance. Although neural network has strong feature-learning capabilities, it often struggles to detect minority classes in imbalanced datasets. The weighted mechanism in WRF enhances minority class recognition, helping maintain strong predictive performance under imbalance. Compared to LightGBM, the integrated model offers better prediction accuracy and stability. LightGBM, a fast and efficient gradient boosting algorithm, performs well on large datasets but can be challenged by complex nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional features. By incorporating BPNN’s nonlinear fitting capability, the integrated model better captures these complexities, resulting in superior accuracy and stability.

To assess the competitiveness and originality of the proposed model, this study conducts a direct evaluation against four representative works. These works focus on user or student behavior prediction in educational settings. To ensure fairness and consistency, the key predictive models from these studies are re-implemented on the same test dataset, with all parameter settings replicated precisely as originally reported. Table 3 presents a detailed comparison between the proposed ensemble model (WRF + BPNN + CNN + Attention) and the benchmark models from the literature.

Table 3.

Model performance comparison results.

| References | Model description | Accuracy (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo et al.50 | Machine learning algorithm (based on online behavior) | 89.1 | 83.5 | 86.2 |

| Yildiz Durak and Onan51 | PLS-SEM + ML (partial least squares structural equation modeling + machine learning) | 90.3 | 84.8 | 87.4 |

| Jain and Raghuram52 | SEM-ANN (structural equation modeling - artificial neural network) | 90.7 | 86.1 | 88.3 |

| Mathur et al.53 | Hybrid SEM-ANN (structural equation modeling - artificial neural network) | 91.2 | 86.9 | 89.0 |

| Proposed (this study) | WRF + BPNN + CNN + Attention | 92.3 | 89.7 | 90.8 |

As shown in Table 3, the results clearly demonstrate the consistent performance advantage of the proposed ensemble model (WRF + BPNN + CNN + Attention) over several recent state-of-the-art approaches. In terms of accuracy, this model achieved 92.3%, surpassing Luo et al.’s machine learning method by 3.2%, Yildiz Durak & Onan’s PLS-SEM + ML approach by 2.0%, Jain & Raghuram’s SEM-ANN model by 1.6%, and Mathur et al.’s hybrid SEM-ANN framework by 1.1%. The performance gains are even more notable in recall, where the proposed model achieved 89.7%—substantially higher than the baseline models, which ranged from 83.5 to 86.9%. This demonstrates a stronger capacity to detect minority behavior classes, such as high-engagement users or at-risk students, particularly within imbalanced datasets. Additionally, the F1-score—a balanced measure that considers both precision and recall—reached 90.8%, underscoring the overall predictive superiority of this model.

These improvements stem from several targeted architectural innovations. First, unlike traditional machine learning methods or shallow ANN/SEM models, this approach incorporates a CNN. The CNN automatically and effectively extracts complex local temporal patterns in user behavior data. Examples include login frequency trends and time-specific engagement peaks. These patterns are often missed by conventional methods. Second, a MHAM is integrated to dynamically reweight the extracted features. This significantly enhances the model’s ability to detect critical discriminative cues, such as consistently high-performance behaviors or key course interactions. The addition of MHAM also overcomes the limitations of earlier SEM and ANN models, which tend to rely on static feature weights or implicitly learned feature relevance. Third, to address the pervasive issue of class imbalance in online education datasets, a WRF is incorporated either as a preprocessing component or as the core classifier. By applying class-weighting strategies based on node purity, feature importance, and skewed class distributions, the WRF significantly enhances the model’s ability to detect minority class instances. These include high-value user behaviors and dropout risks. This aspect is often underemphasized in prior studies. Finally, a BPNN is employed for the final prediction stage. Leveraging its strong nonlinear fitting capabilities, the BPNN models the complex patterns extracted and enhanced through CNN-MHAM and refined via WRF-based classification.

From the perspective of academic innovation and competitive performance, the core strength of this study lies in its deep integration of four components. These are CNN (for feature extraction), MHAM (for dynamic feature weighting), WRF (for handling class imbalance), and BPNN (for nonlinear modeling). All components work together within a unified predictive framework. This architecture is specifically tailored to the high-dimensional, temporally structured, locally dependent, nonlinear, and highly imbalanced nature of user behavior data on AI-driven online education platforms. Compared to traditional machine learning methods or hybrid SEM-ANN models, which primarily focus on structural relationships and shallow predictive capabilities, this model represents a significant technical advancement. It excels in automated feature engineering, adaptive feature importance learning, minority class detection, and the modeling of complex behavioral patterns. In particular, the CNN-MHAM module’s enhancement of local and discriminative features, combined with WRF’s effectiveness in identifying minority behavior patterns, are key drivers of this model’s superior performance—especially in terms of recall. These innovations collectively demonstrate the model’s robustness and competitiveness in addressing real-world, complex, and imbalanced behavioral prediction tasks in educational settings.

Discussion

An integrated model combining WRF and BPNN is proposed, and by incorporating CNN and MHAM, the accuracy and reliability of user behavior prediction on AI online education platforms are significantly enhanced. Chi et al. explored the use of a traditional random forest algorithm for predicting user behavior on such platforms54. Their findings showed that random forests performed well on large-scale datasets, particularly in terms of prediction accuracy. However, traditional random forests often struggle with imbalanced data, tending to overlook minority samples, which leads to a low recall rate. To address this issue, this study adopts the WRF model, which improves recognition of minority classes and enhances overall prediction performance by weighting the prediction results of each decision tree. Experimental results show that the integrated model achieves a recall rate of 89.7%, significantly higher than the 82.4% recall rate of the unweighted random forest. This improvement confirms the effectiveness of the WRF model in handling imbalanced data and highlights the importance of the weighting strategy for identifying minority classes. As Chi et al. noted, WRF effectively mitigated data imbalance problems. Xiao et al. examined the application of BPNN for user behavior prediction55. By adjusting the network structure and hyperparameters, they improved prediction accuracy to some extent. However, single BPNN models can suffer from overfitting and slow convergence when handling complex nonlinear relationships. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an integration method combining WRF and BPNN. In this approach, WRF serves as a preliminary classifier, enhancing data processing efficiency and providing more accurate initial weight distributions, thereby addressing the shortcomings of standalone BPNN models. This allows the BPNN to converge faster and better capture the nonlinear relationships in the data. Experimental results show that the integrated model achieves an accuracy of 92.3%, approximately 5% points higher than the traditional BPNN’s 87.3%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the integration method in improving prediction accuracy. Ferdinandy et al. highlighted the importance of cross-validation in model training and examined how the generalization ability changed with different fold numbers56. While their study concluded that 10-fold cross-validation is preferable, it primarily focused on optimizing single algorithms and did not explore integrated models in depth. In this study, 10-fold cross-validation is applied to the integrated model, and its performance is evaluated accordingly. Results indicate that increasing the number of folds improves the average accuracy, recall, and F1 score, with 10-fold cross-validation yielding the best generalization. However, when the number of folds increases to 15, performance slightly declines, confirming that 10-fold cross-validation strikes a good balance between generalization and overfitting prevention. The application of the proposed integrated model in online education platforms holds significant practical value. Accurate user behavior prediction helps platforms better understand user needs, optimize course recommendations, and personalize learning paths, thereby enhancing user experience and learning outcomes. Furthermore, the model’s strong performance with imbalanced data is crucial for identifying minority user behaviors, enabling the platform to serve diverse user groups more effectively.

Conclusion

Research contribution

The main contribution of this study is the proposal and exploration of an improved BPNN model based on WRF to address user behavior prediction in AI-driven online education platforms. First, WRF is introduced as a preprocessing step to effectively tackle data imbalance challenges common in such platforms. By using ensemble learning, WRF enhances the model’s ability to recognize minority classes, thereby improving overall prediction performance. Second, the BPNN model employs the backpropagation algorithm to optimize weights, enabling it to better capture and fit the nonlinear relationships in user behavior data, which further boosts prediction accuracy and generalization. Finally, WRF and BPNN are integrated into a unified model. Its performance is optimized through cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness and reliability in practical applications.

Although the proposed model is developed and validated for user behavior prediction on AI-enabled online education platforms, its core design principles and technical components exhibit strong generalizability. This suggests significant potential for broader applications. The model integrates several widely used machine learning and deep learning techniques: CNN, which effectively captures local patterns and spatial-temporal dependencies; MHAM, which dynamically identifies and weights key features; WRF, which addresses class imbalance and improves recognition of minority classes; and BPNN, known for robust nonlinear modeling capabilities. These components are not limited to a specific domain, making the model adaptable to a variety of complex prediction tasks. Its main strength lies in handling data characterized by high dimensionality, complex temporal or sequential patterns, strong local dependencies, pronounced nonlinearity, and imbalanced class distributions. This makes it well suited for user or customer behavior prediction across diverse domains, including:

E-commerce platforms: Predicting user purchase intent, click behavior, churn risk, or identifying high-value customers. E-commerce data typically involve rich interaction sequences (e.g., browsing, clicking, adding to cart, purchasing), high-dimensional features (e.g., product attributes, user profiles), and imbalanced behavior classes (e.g., buyers vs. browsers).

Social media analytics: Forecasting user engagement (likes, comments, shares), topic virality, or community affiliation. Social media data streams are highly temporal and diverse, with large variations in user activity levels.

Fintech and risk management: Applications include credit scoring, fraud detection, and behavioral forecasting in personal finance. These tasks involve complex transactional sequences and rare but critical events (e.g., fraud), demanding accurate pattern recognition and effective handling of data imbalance.

Smart healthcare and health management: Predicting disease risk, treatment adherence, or intervention effectiveness. Healthcare data are similarly high-dimensional, sequential (e.g., biometric monitoring), and often imbalanced due to the rarity of certain conditions. Successfully adapting this model to new domains requires domain-specific feature engineering and, where necessary, model fine-tuning. The input layer must be reconfigured to match the dimensionality of the new feature set. More importantly, CNN components may need adjustments to kernel size and stride to effectively capture domain-relevant local patterns—for example, browsing sequences in e-commerce or transaction windows in financial data. The MHAM component can automatically learn dynamic feature weights in the new context. The WRF module’s weighting strategies—based on node purity, feature importance, and class distribution—are inherently generalizable and remain effective for addressing class imbalance. The BPNN can be retrained or fine-tuned on new data to model complex, domain-specific nonlinear relationships. Overall, the model architecture offers a robust and flexible foundation. Although this study focuses on the online education context, the proposed ensemble model demonstrates strong generalizability and transferability for user behavior prediction across various domains. A key direction for future research involves deploying and evaluating the model across diverse application areas, such as e-commerce and financial risk assessment. This will help further validate its robustness, scalability, and practical applicability. These efforts aim to facilitate the model’s adoption across a broader range of user behavior prediction tasks.

Future works and research limitations

Although the improved BPNN model based on WRF has shown significant success in predicting user behavior, several areas still require further investigation and enhancement. Data imbalance remains a major challenge in online education platforms. While existing methods have made progress, there is room for improvement. Future research should explore more advanced weighting strategies and sampling techniques to better identify minority classes. Additionally, incorporating cutting-edge methods such as transfer learning and generative adversarial networks could more effectively utilize limited minority class data, improving the model’s generalization and adaptability. Further work could also examine more complex ensemble learning frameworks and deep learning models to enhance predictive performance and better handle complex data. For example, combining different ensemble approaches with deep learning techniques may yield more robust and adaptable prediction systems. Finally, developing customized feature engineering and model optimization methods tailored to specific types of user behavior data could uncover deeper insights, thereby improving prediction accuracy and reliability.

Author contributions

Kaixin Zheng: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation Zhensen Liang: writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Zhensen Liang on reasonable request via e-mail zhensenl97@gmail.com.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Antai College of Economics & Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 2022.5985876). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sun, Z., Anbarasan, M. & Kumar, D. P. Design of online intelligent english teaching platform based on artificial intelligence techniques. Comput. Intell.37, 1166–1180 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao, P., Li, J. & Liu, S. An introduction to key technology in artificial intelligence and big data driven e-learning and e-education. Mob. Netw. Appl.26, 2123–2126 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, Y. & Ren, L. The influence of artificial intelligence technology on teaching under the threshold of Internet+: Based on the application example of an English education platform. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput.2022, 5728569 (2022).

- 4.Dai, D. D. Artificial intelligence technology assisted music teaching design. Sci. Program.2021, 9141339 (2021).

- 5.Hooda, M. et al. Artificial intelligence for assessment and feedback to enhance student success in higher education. Math. Probl. Eng.2022, 5215722 (2022).

- 6.Khan, M. A., Khojah, M. & Vivek Artificial Intelligence and Big Data: The advent of new pedagogy in the adaptive e-learning system in the higher educational institutions of Saudi Arabia. Educ. Res. Int.2022, 1263555 (2022).

- 7.Mubarak, A. A., Cao, H. & Zhang, W. Prediction of students’ early dropout based on their interaction logs in online learning environment. Interact. Learn. Environ.30, 1414–1433 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou, M. et al. Consumer behavior in the online classroom: Using video analytics and machine learning to understand the consumption of video courseware. J. Mark. Res.58, 1079–1100 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albreiki, B., Zaki, N. & Alashwal, H. A systematic literature review of student’ performance prediction using machine learning techniques. Educ. Sci.11, 552 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, Z. Y., Lomovtseva, N. & Korobeynikova, E. Online learning platforms: Reconstructing modern higher education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn.15, 4–21 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu, H. et al. Big data analytics for MOOC video watching behavior based on spark. Neural Comput. Appl.32, 6481–6489 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yağcı, M. Educational data mining: prediction of students’ academic performance using machine learning algorithms. Smart Learn. Environ.9, 11 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moubayed, A. et al. Student engagement level in an e-learning environment: Clustering using k-means. Am. J. Distance Educ.34, 137–156 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv, C. et al. Machine learning: an advanced platform for materials development and state prediction in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater.34, 2101474 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin, X. et al. User OCEAN personality model construction method using a BP neural network. Electronics11, 3022 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiahou, X. & Harada, Y. Customer churn prediction using adaboost classifier and BP neural network techniques in the E-commerce industry. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag.12, 277–293 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitsios, F. et al. User-generated content behavior and digital tourism services: A SEM-neural network model for information trust in social networking sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag Data Insights2, 100056 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng, Y. et al. An optimal BP neural network track prediction method based on a GA–ACO hybrid algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.10, 1399 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, X., Wang, J. & Yang, C. Risk prediction in financial management of listed companies based on optimized BP neural network under digital economy. Neural Comput. Appl.35, 2045–2058 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aydoğdu, Ş. Predicting student final performance using artificial neural networks in online learning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol.25, 1913–1927 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, F. & Cui, Y. Utilizing student time series behaviour in learning management systems for early prediction of course performance. J. Learn. Anal.7, 1–17 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Disha, R. A. & Waheed, S. Performance analysis of machine learning models for intrusion detection system using Gini impurity-based weighted random forest (GIWRF) feature selection technique. Cybersecurity5, 1 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan, N. U. et al. Prediction and classification of user activities using machine learning models from location-based social network data. Appl. Sci.13, 3517 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirabayashi, J. V., Braga, A. S. M. & da Silva, J. Comparative approach to different convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures applied to human behavior detection. Neural Comput. Appl.35, 12915–12925 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alshurideh, M., Kurdi, A. & Salloum, B. Predicting the actual use of m-learning systems: a comparative approach using PLS-SEM and machine learning algorithms. Interact. Learn. Environ.31, 1214–1228 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray, A. et al. Transfer learning enhanced vision-based human activity recognition: A decade-long analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag Data Insights. 3, 100142 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onan, A. Sentiment analysis on massive open online course evaluations: A text mining and deep learning approach. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ.29, 572–589 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyu, L. et al. Deep knowledge tracing based on Spatial and Temporal representation learning for learning performance prediction. Appl. Sci.12, 7188 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu, N. et al. Graph learning-based spatial-temporal graph convolutional neural networks for traffic forecasting. Connect. Sci.34, 429–448 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devan, P. & Khare, N. An efficient XGBoost–DNN-based classification model for network intrusion detection system. Neural Comput. Appl.32, 12499–12514 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manokaran, J. & Vairavel, G. GIWRF-SMOTE: Gini impurity-based weighted random forest with SMOTE for effective malware attack and anomaly detection in IoT-Edge. Smart Sci.11, 276–292 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, J., Tsai, P. H. & Tsai, M. H. Semantic2Graph: Graph-based multi-modal feature fusion for action segmentation in videos. Appl. Intell.54, 2084–2099 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, X. et al. Conditional cross-platform user engagement prediction. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst.42, 1–28 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan, N. & Au, O. T. S. Online learning behavior analysis based on machine learning. Asian Assoc. Open. Univ. J.14, 97–106 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin, S. et al. Developing a personalized E-learning and MOOC recommender system in IoT-enabled smart education. IEEE Access.11, 136437–136455 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talebi, K., Torabi, Z. & Daneshpour, N. Ensemble models based on CNN and LSTM for dropout prediction in MOOC. Expert Syst. Appl.235, 121187 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu, G. & Zhuang, H. Evaluation model of multimedia-aided teaching effect of physical education course based on random forest algorithm. J. Intell. Syst.31, 555–567 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dass, S., Gary, K. & Cunningham, J. Predicting student dropout in self-paced MOOC course using random forest model. Information12, 476 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu, C. et al. Prediction of prognosis and survival of patients with gastric cancer by a weighted improved random forest model: an application of machine learning in medicine. Arch. Med. Sci.18, 1208 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smirani, L. K. et al. Using ensemble learning algorithms to predict student failure and enabling customized educational paths. Sci. Program.2022, 3805235 (2022).

- 41.Bagunaid, W., Chilamkurti, N., Veeraraghavan, P. & Aisar Artificial intelligence-based student assessment and recommendation system for e-learning in big data. Sustainability14, 10551 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alhothali, A. et al. Predicting student outcomes in online courses using machine learning techniques: A review. Sustainability14, 6199 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pellegrino, E. et al. Machine learning random forest for predicting oncosomatic variant NGS analysis. Sci. Rep.11, 21820 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong, Z. et al. Robust optimization design method for structural reliability based on active-learning MPA-BP neural network. Int. J. Struct. Integr.14, 248–266 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar, M. G. V. et al. Evaluation of the quality of practical teaching of agricultural higher vocational courses based on BP neural network. Appl. Sci.13, 1180 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Momeni, A. et al. Backpropagation-free training of deep physical neural networks. Science382, 1297–1303 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng, Z. et al. Dual adaptive training of photonic neural networks. Nat. Mach. Intell.5, 1119–1127 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 48.He, S. et al. Short-term runoff prediction optimization method based on BGRU-BP and BLSTM-BP neural networks. Water Resour. Manag. 37, 747–768 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ang, K. M. et al. MTLBORKS-CNN: an innovative approach for automated convolutional neural network design for image classification. Mathematics11, 4115 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo, Y., Han, X. & Zhang, C. Prediction of learning outcomes with a machine learning algorithm based on online learning behavior data in blended courses. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev.25, 267–285 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yildiz Durak, H. & Onan, A. Predicting the use of chatbot systems in education: A comparative approach using PLS-SEM and machine learning algorithms. Curr. Psychol.43, 23656–23674 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jain, K. K. & Raghuram, J. N. V. Gen-AI integration in higher education: Predicting intentions using SEM-ANN approach. Educ. Inf. Technol.29, 17169–17209 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathur, S. et al. An integrated model to predict students’ online learning behavior in emerging economies: A hybrid SEM–ANN approach. J. Int. Educ. Bus.18, 102–126 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chi, Z., Zhang, S. & Shi, L. Analysis and prediction of MOOC learners’ dropout behavior. Appl. Sci.13, 1068 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao, Y. et al. User behavior prediction of social hotspots based on multimessage interaction and neural network. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst.7, 536–545 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferdinandy, B. et al. Challenges of machine learning model validation using correlated behaviour data: evaluation of cross-validation strategies and accuracy measures. PLoS One15, e0236092 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Zhensen Liang on reasonable request via e-mail zhensenl97@gmail.com.