Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to enhance prostate cancer (PCa) detection in patients with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels within the “gray zone” (4–10 ng/mL) by comparing PSA density (PSAD) calculations derived from the traditional ellipsoid formula (TEF) and the biproximate ellipsoid formula (BPEF).

Materials and methods

A total of 99 patients were enrolled. All participants underwent transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) for prostate volume estimation, followed by PSAD calculation using both the BPEF and TEF methods. The BPEF method, which incorporates well-defined anatomical landmarks, was assessed for its accuracy in prostate volume measurement and diagnostic performance for PCa compared to TEF. Inter- and intra-observer consistency were also evaluated for both approaches.

Results

Both BPEF and TEF reliably measured prostate volume, however, BPEF demonstrated superior accuracy and higher consistency in inter- and intra-observer assessments. PSAD calculated using BPEF (BPEF-PSAD) exhibited significantly greater diagnostic performance than TEF-PSAD, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.84. At the optimal diagnostic threshold of 0.15 ng/mL/cm³, BPEF-PSAD achieved a sensitivity of 88.89% and a specificity of 74.60%, enhancing the discrimination between PCa and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified BPEF-PSAD as an independent predictor of PCa.

Conclusions

The study concluded that the BPEF method, when combined with TRUS, improves the accuracy of PSA density measurements, potentially reducing unnecessary biopsies in patients with intermediate PSA levels, particularly in cases where MRI is unavailable or contraindicated.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, PSA gray zone, PSA density, Biproximate ellipsoid formula, Transrectal ultrasound

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men worldwide [1]. With changing lifestyles and increased life expectancy, the incidence and mortality of PCa have risen significantly, particularly in China [2]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020, China accounts for 8.2% of global PCa cases and 13.6% of PCa-related deaths [3]. A recent multicenter study revealed that only one-third of Chinese PCa patients are diagnosed at a localized stage, while the majority present with advanced disease, resulting in poorer prognoses compared to Western countries [4]. Early diagnosis and timely interventions, such as surgery or endocrine therapy, can significantly improve patient outcomes. However, early-stage PCa is often asymptomatic, leading to delayed diagnosis and reduced treatment success [5]. Consequently, screening and early detection in high-risk populations are crucial for improving survival rates.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is widely used as a screening tool for PCa [6]. PSA is produced by prostate epithelial cells and enters the bloodstream when prostate tissue is damaged or diseased, resulting in elevated serum PSA levels. However, distinguishing PCa from benign conditions becomes challenging when PSA levels fall within the “PSA gray zone” (4–10 ng/mL) [7]. Studies indicate that only 22% of patients within this range are biopsy-confirmed to have PCa, suggesting that up to 78% of biopsies may be unnecessary [8]. Thus, more accurate biomarkers are needed to better differentiate PCa from benign conditions in PSA gray zone patients, potentially reducing unnecessary invasive procedures.

Prostate-specific antigen density (PSAD), introduced by Benson et al., is the ratio of serum PSA to prostate volume [9]. In China, current guidelines recommend using PSAD to improve diagnostic accuracy in PSA gray zone patients [10]. T Similarly, the European Association of Urology advocates the use of PSAD to guide biopsy decisions when PSA levels and imaging findings are inconclusive [11]. Recent studies have demonstrated that PSAD is a strong predictor of PCa, particularly in patients with low to intermediate risk [12, 13]. Moreover, PSAD has shown promise as an early indicator of PCa, emphasizing the importance of accurate prostate volume estimation.

Prostate volume can be estimated through various methods, including digital rectal examination (DRE), abdominal ultrasound, transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [14]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) currently represents the gold standard for prostate volume measurement, offering superior soft tissue contrast and three-dimensional reconstruction capabilities [15]. Recent advances in MRI-based prostate assessment, including PI-RADS lesion volume measurements, have further enhanced diagnostic accuracy [16, 17]. However, MRI remains costly, time-consuming, and often contraindicated in elderly patients with cardiac pacemakers or claustrophobia, who represent a significant proportion of the prostate cancer population. Additionally, MRI availability varies significantly across different healthcare settings, particularly in resource-limited environments.

In contrast, TRUS is widely available, cost-effective, and patient-friendly, making it an attractive alternative for routine clinical practice. Although TRUS is effective, the conventional ellipsoid formula used for prostate volume estimation can introduce inaccuracies, particularly in cases with irregular prostate morphology commonly seen in BPH patients with significant median lobe enlargement or intravesical prostatic protrusion. Recent research has introduced the Biproximate Ellipsoid Formula (BPEF), which enhances precision by using well-defined anatomical landmarks to measure prostate volume [18]. Validated through comparisons with pathology and MRI, the BPEF method has demonstrated superior accuracy and consistency across evaluators, particularly in cases with complex prostate anatomy.

This study investigates the adaptation of the BPEF method for use with TRUS to provide more accurate PSAD values, thereby improving the early detection of PCa in PSA gray zone patients. The primary objective is to compare prostate volume measurements obtained using the traditional ellipsoid formula (TEF) and the BPEF method with TRUS, and to evaluate the diagnostic value of PSAD in PSA gray zone patients.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective study included patients diagnosed with prostate diseases and admitted to our hospital between January 2023 and June 2024. All diagnoses were pathologically confirmed through surgery or biopsy. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) serum PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng/mL, (2) patients who underwent TRUS examination prior to biopsy, and (3) informed consent obtained, with patients able to tolerate the biopsy and provide definitive diagnostic results. The exclusion criteria were: (1) conditions affecting PSA measurements, such as prostatitis, urinary tract infection, or the presence of an indwelling catheter, (2) a history of prostate surgery, medication treatment, or prior prostate biopsy, and (3) severe cardiopulmonary diseases that prevented the patient from tolerating biopsy or surgery.

Patients were divided into two groups based on pathology results: PCa group and the benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) group.

Ultrasound instruments and examination protocol

Ultrasonographic examinations were performed using a GE LOGIQ E11 color Doppler ultrasound system with an intracavitary probe, operating at a frequency of 5.5-9 MHz. Multiplanar scanning was conducted to assess prostate morphology, capsule integrity, and internal glandular echogenicity.

To compare the accuracy of prostate volume measurement, two formulas were used: the BPEF and TEF methods.

BPEF method

The BPEF method incorporates specific anatomical landmarks to improve measurement accuracy. The transverse and anteroposterior (AP) diameters were measured from the transverse ultrasound image of the prostate at its maximum dimension. The longitudinal diameter was measured using a modified sagittal view that specifically identifies the vesico-prostatic angle (VPA), where the bladder detrusor muscle meets the prostate capsule. A vesico-prostatic line (VPL) was drawn connecting these anatomical points, and an apical line (AL) was created through the urethral outlet at the prostatic apex.

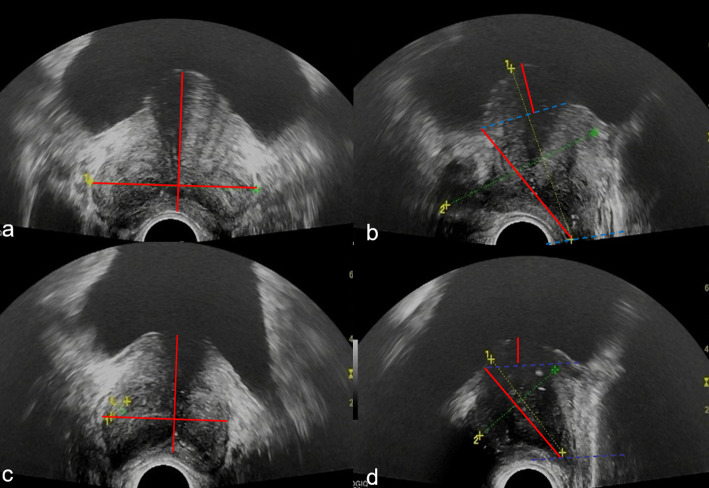

For prostates entirely below the VPL, the superior-inferior diameter was measured vertically from the midpoint of the urethra at the AL level to the VPL. For prostates extending above the VPL (commonly seen in BPH with intravesical protrusion), the total superior-inferior diameter was calculated as the sum of the distances below and above the VPL, measured perpendicularly to account for the irregular morphology (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative transrectal ultrasound images demonstrating BPEF measurement technique across different pathological conditions. Images (a) and (c) show axial views displaying the prostate’s transverse and anteroposterior diameters at maximum dimensions. Images (b) and (d) show sagittal views for superior-inferior diameter measurement, calculated as the sum of distances above and below the vesico-prostatic line (indicated by red lines). Images (a) and (b) are from a 70-year-old male patient with surgically confirmed BPH, demonstrating irregular prostate morphology with median lobe enlargement and intravesical protrusion (BPEF-calculated volume: 57.34 cm³). Images (c) and (d) are from a 68-year-old male patient with surgically confirmed (PCa (BPEF-calculated volume: 46.83 cm³)

TEF method

The traditional ellipsoid formula measured the AP diameter in the sagittal plane, assuming a uniform prolate ellipsoid shape without accounting for anatomical variations or intravesical prostatic protrusion.

Formula: Prostate volume was calculated using the following formula for both methods:

|

|

Two radiologists, with 8 and 15 years of experience in prostate ultrasound, independently calculated prostate volume using both the BPEF and TEF methods. Measurements were repeated one week later to assess intra-observer reliability. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate consistency, with an ICC > 0.80 indicating good agreement.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For normally distributed data with equal variances, independent sample t-tests were applied. For non-normally distributed data or unequal variances, the Mann-Whitney U test was used.

Prostate volume measurements obtained using the BPEF and TEF methods were compared using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, depending on the data distribution.

The diagnostic efficacy of PSAD was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with the area under the curve (AUC) calculated. The optimal diagnostic threshold was determined using the Youden index, and sensitivity and specificity were calculated at this threshold. ROC curves were also used to compare the diagnostic performance of PSAD in distinguishing PCa from BPH based on volumes derived from both the BPEF and TEF methods, with AUC values reflecting diagnostic accuracy.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0, with a P-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 99 patients were included in this study: 36 patients were diagnosed with PCa and 63 patients with BPH. The mean age of the PCa group was 68.1 years (range: 50–82 years), while the mean age of the BPH group was 65.1 years (range: 51–81 years). No significant difference in age between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| PCa(n = 36) | BPH (n = 63) | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.14 ± 7.74 | 65.14 ± 6.88 | -0.013 | 0.898 |

| PSA(ng·mL− 1) | 7.15 ± 1.57 | 6.53 ± 1.38 | 1.963 | 0.054 |

| BPEF (cm3) | 41.46 ± 7.19 | 48.18 ± 9.37 | -3.994 | 0.001 |

| TEF (cm3) | 44.39 ± 8.58 | 48.36 ± 9.62 | -1.98 | 0.052 |

|

BPEF-PSAD (ng.ml− 1.cm3) |

0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 6.652 | <0.001 |

|

TEF-PSAD (ng.ml− 1.cm3) |

0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 4.465 | <0.001 |

The mean prostate volume measured using the BPEF method was 41.46 mL in the PCa group, which was significantly lower than the 48.18 mL observed in the BPH group (P = 0.001). In contrast, the mean prostate volume measured using the TEF method was 44.39 mL in the PCa group and 48.36 mL in the BPH group, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.052). Figure 1 demonstrates representative ultrasound images from two patients with pathologically confirmed diagnoses through surgical specimens.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for prostate volume measurement using the BPEF method was 0.85, indicating good agreement between the two radiologists. This suggests that the BPEF method provides consistent prostate volume measurements across evaluators, ensuring its reliability for clinical applications. Inter-observer agreement for prostate volume measurement was also assessed for both the BPEF and TEF methods. The ICC for the BPEF method (0.85) demonstrated slightly stronger agreement between radiologists compared to the TEF method, which had an ICC of 0.82. Both methods exhibited good reliability; however, the BPEF method showed marginally better inter-observer consistency.

The mean PSA density (PSAD) calculated using the BPEF method (BPEF-PSAD) was significantly higher in the PCa group (0.17 ng/mL/cm³) compared to the BPH group (P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean PSAD calculated using the TEF method (TEF-PSAD) was 0.16 ng/mL/cm³ in the PCa group and 0.14 ng/mL/cm³ in the BPH group, also showing a significant difference (P < 0.001).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified BPEF-PSAD as an independent predictor of PCa (Table 2). The optimal diagnostic threshold for BPEF-PSAD, determined using the Youden index, was 0.15 ng/mL/cm³. At this threshold, BPEF-PSAD demonstrated a sensitivity of 88.89% and a specificity of 74.6% for predicting PCa. The area under the curve (AUC) for BPEF-PSAD was 0.84, indicating strong diagnostic performance (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis: association between prostate volume and PSA density calculation methods with prostate cancer risk

| Standard Error | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | Z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPEF (cm3) | 0.033 | -0.061 (-0.125- 0.003) | -1.871 | 0.061 |

|

BPEF-PSAD (ng.ml− 1.cm3) |

14.593 | 45.221 (16.619–73.824) | 3.099 | 0.002 |

|

TEF-PSAD (ng.ml− 1.cm3) |

12.84 | 0.597 (-24.568–25.762) | 0.047 | 0.963 |

Table 3.

Comparison of diagnostic performance between different PSA density calculation methods

| Optimal Threshold | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPEF-PSAD | 0.15 | 88.89 | 74.60 | 66.67 | 92.16 | 0.84 |

PPV = Positive Predictive Value, NPV = Negative Predictive Value

Fig. 2.

Performance of PSAD calculated by using BPEF formulas-derived volume for detection of lesions

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we compared two methods for calculating prostate volume and subsequent PSAD in patients within the PSA gray zone (4–10 ng/mL). Our findings demonstrate that PSAD calculated using the BPEF provides superior diagnostic accuracy compared to the TEF. These results highlight the critical role of PSAD as a reliable biomarker for distinguishing PCa from BPH in this diagnostically challenging range.

The high intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.85 observed in our study indicates strong measurement consistency between radiologists. This is consistent with the findings of Wasserman et al., who reported similar reliability using the BPEF method with MRI [18]. The relatively low variability in prostate volume measurements achieved with BPEF enhances the diagnostic value of PSAD, as accurate volume estimation is crucial for correctly identifying patients at risk for PCa [2]. Furthermore, the slightly higher ICC for BPEF (0.85) compared to TEF (0.82) suggests that BPEF provides marginally better inter-observer consistency, further supporting its use in clinical practice.

Our study corroborates previous research demonstrating PSAD as a robust predictor of PCa [12], particularly within the PSA gray zone, where distinguishing malignant from benign conditions remains a significant challenge. The significantly higher mean PSAD observed in the PCa group compared to the BPH group aligns with the findings of Bruno et al. [19], who first introduced PSAD as a diagnostic tool to enhance PCa detection accuracy in patients with intermediate PSA levels. In our study, the ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.84 for BPEF-PSAD, confirming its excellent discriminatory power in differentiating PCa from BPH, particularly when compared to traditional calculation methods.

The accuracy of PSAD is fundamentally dependent on the precision of prostate volume measurements. In this study, the BPEF method demonstrated higher accuracy in prostate volume assessment compared to the TEF. The superior performance of the BPEF method can be attributed to its incorporation of well-defined anatomical landmarks that better account for prostate morphological variations. The VPA and VPL provide consistent reference points that are particularly valuable in BPH cases with irregular prostate contours. In our study, the volumetric differences between BPEF and TEF were indeed more pronounced in the BPH group, as hypothesized, due to the increased frequency of intravesical prostatic protrusion and median lobe enlargement in these patients. Previous studies validating the reliability of the BPEF method, such as those by Hamzaoui et al. [15], have attributed its precision to the incorporation of intravesical prostatic protrusion, which is particularly beneficial in cases of irregular prostate morphology. Conversely, the traditional ellipsoid formula assumes a uniform prolate ellipsoid shape, which inadequately represents the complex three-dimensional anatomy of enlarged prostates. This limitation is particularly evident in BPH patients, where asymmetric growth patterns and median lobe protrusion create irregular contours that deviate significantly from the ellipsoid model. The BPEF method addresses this limitation by measuring the actual prostatic boundaries relative to anatomical landmarks, resulting in more accurate volume calculations.

The superior diagnostic performance of BPEF-PSAD can be attributed to the improved precision of prostate volume measurements using this method. Unlike TEF, which assumes a uniform ellipsoidal shape, BPEF integrates well-defined anatomical landmarks to account for individual variations in prostate morphology. This adjustment significantly enhances volume estimation accuracy, leading to more reliable PSAD calculations. At the optimal diagnostic threshold of 0.15 ng/mL/cm³, BPEF-PSAD demonstrated higher sensitivity (88.89%) and specificity (74.60%) for distinguishing PCa from BPH. These findings suggest that BPEF-PSAD has the potential to reduce unnecessary biopsies in PSA gray zone patients. Furthermore, these results align with previous studies [20, 21] emphasizing the importance of precise prostate volume measurements for optimizing PSAD as a diagnostic biomarker.

The improved diagnostic accuracy of BPEF-PSAD may also reflect biological differences between PCa and BPH. PCa often involves alterations in tissue density and prostate architecture that may not be fully captured by the uniform assumptions underlying the TEF method. By incorporating anatomical landmarks such as the VPA and VPL, the BPEF method may better account for these structural changes. The observed higher PSAD in PCa patients (mean BPEF-PSAD: 0.17 ng/mL/cm³) supports the established concept that malignant tissue produces PSA more efficiently per unit volume, a hallmark of aggressive prostate pathology. These findings underscore the value of volume-corrected PSA as a meaningful marker of cancer biology, particularly when calculated using more anatomically accurate volume measurements.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size of 99 patients, while adequate for preliminary analysis, is relatively modest for comprehensive evaluation of a diagnostic method. Second, as a single-center study, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other clinical settings with different equipment or operator expertise. Third, we did not perform direct comparison with pathological prostate volumes obtained from radical prostatectomy specimens. Many patients in our cohort underwent biopsy rather than radical prostatectomy, and some BPH patients were managed conservatively, limiting our ability to obtain gold standard volume measurements. Future prospective studies should systematically incorporate pathological volume correlation as a primary validation endpoint. Fourth, while we compared BPEF to TEF, direct comparison with MRI-derived volumes would have provided additional validation, given MRI’s status as the current imaging gold standard for prostate volume measurement. Fifth, the study focused exclusively on patients with PSA levels in the gray zone, and the utility of BPEF-PSAD for patients with PSA levels outside this range requires further investigation. Finally, although inter-observer and intra-observer reliability were assessed, ultrasound examination remains inherently operator-dependent, and the implementation of BPEF in broader clinical practice may require standardized training protocols to ensure consistent results across diverse clinical settings.

Conclusion

We used the BPEF method with TRUS, which offers a practical and accessible method for calculating prostate volume and PSAD. Additionally, the strong correlation between PSAD and PCa risk observed in this study reinforces the potential of PSAD to reduce unnecessary biopsies, thereby minimizing the risks associated with invasive procedures. The identification of BPEF-PSAD as an independent predictor of PCa in multivariate logistic regression analysis further validates its clinical utility for risk stratification in this challenging patient population.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception and design: XW and HZ; Substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of the data: XW and DDX; Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: XW and JXS; Final approval of the version of the article to be published: XW and HZ.

Funding

This work was supported by the Special Research Project of Wuxi Second Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2023YJ12) and Special Scientific Research Project of Guangzhou Cadre and Talent Health Management Center (No. JGZX20230201).

Data availability

For access to the raw data used in this research, please request it from the corresponding author with a valid reason.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuxi Second Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, with ethical approval number 2023SWJJ03. The study adhered to all relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia C, Dong X, Li H, et al. Cancer statistics in China and united states, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135(5):584–90. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J et al. Cancer statistics in china, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016 Mar-Apr;66(2):115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Na R, Ye D, Qi J, et al. Prostate cancer aggressiveness prediction using CT images. Life (Basel). 2021;11(11):1164. 10.3390/life11111164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendes B, Domingues I, Silva A, et al. Prostate cancer aggressiveness prediction using CT images. Life (Basel). 2021;11(11):1164. 10.3390/life11111164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nogueira L, Corradi R, Eastham JA. Prostatic specific antigen for prostate cancer detection. Int Braz J Urol. 2009 Sep-Oct;35(5):521–9. 10.1590/s1677-55382009000500003. discussion 530-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lin K, Lipsitz R, Janakiraman S, et al. Preventive services task force. Benefits and harms of prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3):192–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(17):1156–61. 10.1056/NEJM199104253241702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam JS, Cheung YK, Benson MC, et al. Comparison of the predictive accuracy of serum prostate specific antigen levels and prostate specific antigen density in the detection of prostate cancer in Hispanic-American and white men. J Urol. 2003;170(2 Pt 1):451–6. 10.1097/01.ju.0000074707.49775.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang P, Du W, Xie K, et al. Transition zone PSA density improves the prostate cancer detection rate both in PSA 4.0–10.0 and 10.1–20.0 ng/ml in Chinese men. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(6):744–8. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falagario UG, Martini A, Wajswol E, et al. Avoiding unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and biopsies: negative and positive predictive value of MRI according to Prostate-specific antigen density, 4Kscore and risk calculators. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(5):700–4. 10.1016/j.euo.2019.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park DH, Yu JH. Prostate-specific antigen density as the best predictor of low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer: a cohort study. Transl Cancer Res. 2023;12(3):502–14. 10.21037/tcr-22-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Jiang W, Ding J, et al. Risk factor analysis and optimal cutoff value selection of PSAD for diagnosing clinically significant prostate cancer in patients with negative mpmri: results from a high-volume center in Southeast China. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22(1):140. 10.1186/s12957-024-03420-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo S, Zhang J, Jiao J, et al. Comparison of prostate volume measured by transabdominal ultrasound and MRI with the radical prostatectomy specimen volume: a retrospective observational study. BMC Urol. 2023;23(1):62. 10.1186/s12894-023-01234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamzaoui D, Montagne S, Granger B et al. Prostate volume prediction on MRI: tools, accuracy and variability. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(7):4931–4941. 10.1007/s00330-022-08554-4. Epub 2022 Feb 15. Erratum in: Eur Radiol. 2022;32(7):5035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-022-08688-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Choudhary MK, Kolanukuduru KP, Tillu N, Kotb A, Dovey Z, Buscarini M, Zaytoun O. Lesion volume on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging as a non-invasive prognosticator for clinically significant prostate cancer. Cent Eur J Urol. 2024;77(4):592–8. 10.5173/ceju.2024.0157. Epub 2024 Dec 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellegrino F, Stabile A, Sorce G, et al. Added value of prostate-specific antigen density in selecting prostate biopsy candidates among men with elevated prostate-specific antigen and PI-RADS ≥ 3 lesions on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate: A systematic assessment by PI-RADS score. Eur Urol Focus. 2024;10(4):634–40. Epub 2023 Oct 19. PMID: 37865591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasserman NF, Niendorf E, Spilseth B. Measurement of prostate volume with MRI (A guide for the Perplexed): Biproximate Method with Analysis of Precision and Accuracy. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):575. 10.1038/s41598-019-57046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruno SM, Falagario UG, d’Altilia N, et al. PSA density help to identify patients with elevated PSA due to prostate cancer rather than intraprostatic inflammation: A prospective single center study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:693684. 10.3389/fonc.2021.693684. Published 2021 May 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Yuan L, Shen D, et al. Combination of PI-RADS score and PSAD can improve the diagnostic accuracy of prostate cancer and reduce unnecessary prostate biopsies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1024204. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1024204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong QF, Liu YX, Chen YH, et al. A strategy to reduce unnecessary prostate biopsies in patients with tPSA > 10 Ng ml-1 and PI-RADS 1–3. Asian J Androl. 2025 Jan;28. 10.4103/aja202499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

For access to the raw data used in this research, please request it from the corresponding author with a valid reason.