Abstract

The emergence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinin-based combination therapies necessitates the development of novel antimalarial agents. This study presents the first computational investigation of steroid-tetraoxane hybrids targeting cyclophilin, a key protein implicated in artemisinin resistance mechanisms. We designed a library of 127 steroid-1,2,4,5-tetraoxane hybrid compounds combining steroidal sapogenin (∆5,(6)-diosgenin-3-one) and gem-dihydroperoxides, and employed consensus molecular docking across eight platforms to minimize algorithm-specific biases. Compound A-CY-9C emerged as the lead candidate, exhibiting superior binding stability and a favorable free energy landscape during 500 ns molecular dynamics simulations. The dual pharmacophore mechanism—disrupting parasite cholesterol uptake via the steroid component while inducing oxidative stress through the tetraoxane moiety—offers a novel strategy to combat artemisinin resistance. This first-in-class approach to targeting cyclophilin with steroid-tetraoxane hybrids provides a promising foundation for developing next-generation antimalarials against resistant P. falciparum strains.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-13017-z.

Keywords: Steroid-tetraoxane hybrids, Artemisinin resistance, Cyclophilin inhibition, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics, Antimalarial drug discovery

Subject terms: Cheminformatics, Combinatorial libraries, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Introduction

Malaria has significantly influenced human history and genetics. It is estimated that the disease, transmitted by mosquitoes and caused by several Plasmodium protozoan species, killed approximately 300 million people throughout the 20th century1. According to the latest World Malaria Report published by WHO, there was a slight increase in malaria cases in recent years, while deaths decreased—an estimated 249 million malaria cases and 608,000 deaths in 2022, compared to 247 million cases and 619,000 deaths in 2021, and 245 million cases and 625,000 deaths in 2020. The main countries contributing to the increase were Pakistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Uganda, and Papua New Guinea2. Antimalarial drugs play a critical role in tackling the global malaria burden to control and eliminate the disease3. Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax predominantly cause malaria infection globally. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is now considered the gold standard for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in nearly all areas4. ACT combines a semisynthetic derivative of artemisinin (ART) and a longer-acting drug; ART involves rapid parasite killing to reduce initial parasite load, whereas the longer-acting drug maintains a plasma concentration above the minimum parasiticidal concentration5.

The emergence of resistant strains against ACTs has become increasingly concerning, with reports from Cambodia, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Recent surveillance data indicate that artemisinin resistance has spread to over 40 countries, with some regions reporting treatment failure rates exceeding 10%. The resistance is primarily due to mutations in PfK13 and other genes, raising an urgent need to find new antimalarial drugs6. A crucial mechanism underlying ART resistance is the overexpression of Pf Cyclophilin 19B in PfKelch13, which is the main cytosolic cyclophilin protein of P. falciparum7. Cyclophilins represent a family of proteins that play multiple essential roles in P. falciparum biology. Their primary functions include: Protein folding, regulation, and transport, crucial for parasite survival and pathogenicity8. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) activity is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of various proteins, molecular chaperone activity prevents protein aggregation under stress conditions, and interactions with heat shock proteins (HSPs), such as HSP70, are mainly involved in protein folding and stabilization.

Given their crucial role in parasite survival, cyclophilins represent promising targets for developing novel antimalarial drugs to combat resistant parasites9. The “hybridization” approach emerges as a potential game-changer in this context, as this strategy has proven successful against other diseases such as cancer, AIDS, and tuberculosis8. It represents a rational chemistry-based approach of combining two or more pharmacophores in a single molecule with different modes of biological action (double-edged sword)10. The combination of steroid and tetraoxane moieties presents a particularly promising direction for targeting cyclophilin-mediated resistance. Steroids can effectively hijack the parasite’s cholesterol uptake mechanisms, while tetraoxanes provide potent antimalarial activity through endoperoxide-mediated oxidative stress. When these pharmacophores are combined, they could potentially disrupt both cyclophilin function and parasite metabolism simultaneously. The rationale behind this dual-targeting approach is particularly compelling. The steroid component can exploit the parasite’s dependence on host cholesterol, potentially interfering with membrane formation and cellular development. Meanwhile, the tetraoxane moiety generates reactive oxygen species through iron-mediated activation, leading to oxidative stress and parasite death. This combination could be especially effective against resistant strains, as targeting multiple essential pathways simultaneously reduces the likelihood of resistance development. Furthermore, the steroid scaffold could enhance the drug’s bioavailability and cellular penetration, while the tetraoxane component provides rapid parasiticidal activity. This dual-targeting strategy is particularly relevant for overcoming resistance mechanisms, as mutations affecting one target may not compromise the overall efficacy of the hybrid molecule. Previous studies have demonstrated the success of hybrid approaches in antimalarial drug development, with several promising examples in the literature showing enhanced potency against resistant strains compared to their individual components. Mixed steroidal 1,2,4,5-tetroxane hybrid molecules synthesized via gem-hydroperoxides and evaluated for in vitro antimalarial activity were found to be more potent than mefloquine, ART, multiple times more potent than artelinic acid, and 2.4 times more potent than arteether against chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum W2 clone11. Steroid-trioxane hybrids were synthesized, which have shown promising activity against multidrug-resistant P. yoelii in Swiss mice12. Oxalic acid salt of dihydroartemisinin (DHA)- aminoquinoline hybrid molecules were synthesized and evaluated for in vitro antiplasmodial activity against chloroquine-sensitive (CQS) D10 and chloroquine-resistant (CQR) Dd2 strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Synthesized hybrids have shown better activity than Chloroquine in the CQR strain13. Hybrid molecules containing Primaquine-Artemisinin were designed and synthesized, and their in vitro and in-vivo activity was evaluated in the liver and blood stages. Compounds have shown superior efficacy in vitro against Plasmodium berghei in the liver stage and comparatively as potent as ART in P.falciparum culture. Moreover, one of the compounds has shown better efficacy than the equimolar mixture of the parent compound against P. berghei induced infection14. Quinolone-pyrimidine hybrids were synthesized and tested against (CQS) D10 and (CQR) Dd2 strains of P.falciparum and have shown better potency against the CQR-resistant strain15. A series of 4-aminoquinoline-piperazine-pyrimidine hybrids were synthesized and were found to have 2.5 fold stronger antimalarial activity against the CQR strain of P.falciparum than chloroquine16. Deoxycholic acid-based 1,2,4-trioxolanes and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes were synthesized, and in vitro antimalarial activity was assessed against the (CQS) T96 and (CQR) K1 strains of P.falciparum. Tetraoxanes have shown more promising activity than trioxolanes17. Stigmastane steroids, viz. 6-hydroxystigmast-4-en 3-one, stigmast-4-en-3-one, and 3-hydroxystigmast 5-en-7-one were isolated from the stem bark of Dryobalanops oblongifolia and evaluated for antiplasmodial activity, where 3-hydroxystigmast 5-en-7-one has shown comparatively better activity18.

Diosgenin (25R-spirost-5-en-3β-ol), a steroidal saponin found in fenugreek and yam (Dioscorea spp)19. It is considered to be effective against malaria20. Diosgenone[(25R)-4-Spirosten-3-one] and its derivative were reported to have good antimalarial activity21. Steroids are gaining considerable attention in antimalarial drug discovery as they can hijack cholesterol uptake in the malarial parasite, which is an important nutrient source for parasite growth and development22. ART and its related endoperoxides are the mainstay in the ACT. Structural Activity Relationship (SAR) studies on ART and its derivatives revealed that the lactone ring is not essential for antimalarial activity, and further studies also confirm that the 1,2,4-trioxane (endoperoxide) moiety is the key pharmacophore essential for antimalarial activity. Several synthetic endoperoxide scaffolds, such as 1,2,4-trioxane, 1,2,4-trioxolane, and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane derivatives and their hybrid analogues have gained significant interest and are in different clinical stages of drug discovery and development23.

Drug research has recently attracted increased attention due to computational drug design techniques. These methods are usually simple, inexpensive, and potentiate the discovery process. Docking is one of the computer technologies most frequently used in structure-based drug design. Predictions of ligand binding affinities and thorough details on ligand interactions with amino acid residues in target binding pockets are provided by it24,25. In silico designing, docking, and interaction studies of novel fused quinazoline were carried out against Topoisomerase II, and results were promising for future development26.In silico evaluation of novel 2-Pyrazoline carboxamide derivative was carried out against Falcipain-2, Falcipain-3, and Plasmepsin-2, and has shown strong binding affinities and interactions, and provides a foundation for further study and experimental validation27.

∆5,(6)-diosgenin-3-one, an isomer of diosgenone, can be obtained naturally from Dioscorea nipponica and also synthetically from diosgenin. It is used for the synthesis of new cephalostatin analogues and other steroidal compounds of pharmaceutical importance28. The present approach mainly focusses on rationally designed library of steroid-1,2,4,5-tetraoxane hybrid compounds by combining steroidal sapogenin i.e. ∆5,(6)-diosgenin-3-one[(25R)-5-en-spirosta-3-one] and gem-dihydroperoxides followed by consensus docking targeting Cyclophilin (PDB id: 1QNG) and simulation study to screen out the best possible compounds for further study.

Experimental methodology

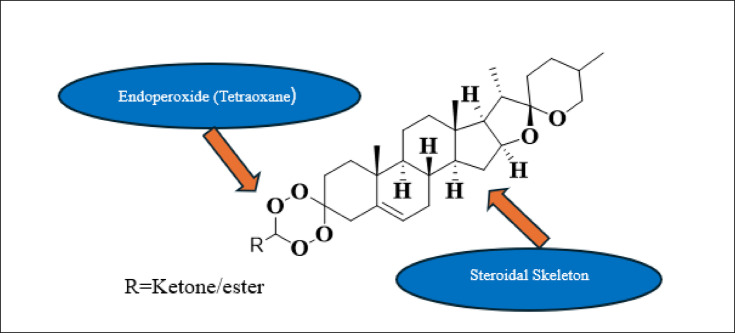

Preparation of compound library

A compound library of 127 hybrid compounds was designed (Fig. 1) by systematically combining the steroidal sapogenin ∆5,(6)-diosgenin-3-one[(25R)-5-en-spirosta-3-one] with gem-dihydroperoxides (cyclic ketones/esters were converted to their corresponding gem-dihydroperoxides). The library was constructed based on established medicinal chemistry principles, focusing on maintaining the core steroid scaffold while introducing structural diversity through variations in the tetraoxane moiety. The compounds were designed manually using ChemDraw 20.1 software29, with careful consideration of synthetic feasibility. Each compound was assigned a unique identifier, and its structure was saved in both MOL file and.sdf format for subsequent computational analyses. The complete library is provided in Supplementary File 1, which includes the chemical structures, SMILES notations, and molecular properties of all 127 compounds.

Fig. 1.

Compound library design.

Prediction of drug score

In-silico drug score assessment was computed for all designed compounds using the OSIRIS DataWarrior tool (version 5.5.0)30. This computational platform employs fragment-based predictive algorithms to evaluate potential toxicological liabilities, including mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, reproductive effects, and irritant properties. The drug score calculation integrates toxicity risk assessments with physicochemical properties (cLogP, solubility, molecular weight, and drug-likeness) to generate a single value between 0 and 1, where higher scores indicate more favorable overall drug-like characteristics.

Quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) scores

The quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) scores31 were calculated for all compounds using the ADMETlab 2.032. QED provides a weighted composite of eight molecular properties (molecular weight, octanol-water partition coefficient, topological polar surface area, number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, number of rotatable bonds, aromatic rings, and structural alerts) that correlate with the likelihood of a compound exhibiting favorable drug-like characteristics. The QED score ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 representing compounds with properties more similar to approved drugs. All compounds were processed using the weighted QED model, which applies different weights to each molecular descriptor based on their relative importance in determining drug-likeness. Compounds with QED scores falling in this range were considered for further molecular docking studies.

Consensus molecular Docking

The compound library was prepared for molecular docking through comprehensive preprocessing steps. All compounds underwent energy minimization and received appropriate charges and hydrogen bonds using OpenBabel33 and UCSF Chimera’s Dock Prep module34. For protein preparation, the crystal structures were cleaned by removing water molecules, heteroatoms, and cofactors, followed by the addition of polar hydrogen atoms and charge calculations. The docking grid box was centered (center_x = 13.2309, center_y = 47.3337, center_z = -16.4818 and size_x = 30, size_y = 30, size_z = 30) on the active sites (ARG62, GLN70, ASN109, PHE120, TRP128, HIS133) of the Cyclophilin (PDB id: 1QNG)35. To overcome potential system-specific biases and enhance the reliability of docking predictions, we employed a consensus docking approach using eight different docking programs: Vina36,37 LeDock38 Q-Vina239, Auto Dock Tools 4.240, i-dock41 and Smina42 by following the same methodology followed in our previous studies43,44. Each program was configured with its optimal parameters while maintaining consistent grid box dimensions across all platforms. The docking results were analyzed based on: Binding energy scores, Interaction patterns with key residues, Conformational clustering, and Consensus ranking across different programs. The compounds were ranked according to their performance across all docking platforms, with special attention given to consistently high-scoring compounds. Radar plot was developed by using python packages matplotlib 3.10.3 (https://matplotlib.org)45 with the help of pandas 2.3.0 (https://pandas.pydata.org)46and numpy 2.3.1 (https://numpy.org)47.

This comprehensive approach helped identify the most promising candidates while minimizing platform-specific biases. The consensus scores were calculated by normalizing the binding energies from each program and combining them into a unified ranking system. This method provided a more robust evaluation of the compounds’ binding potential compared to single program docking approaches. The top-performing compounds from this consensus analysis were selected for further investigation through molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate their stability and interaction dynamics under physiological conditions.

Molecular dynamics simulation

To investigate the conformational dynamics and stability of protein-ligand complexes, we performed all-atom molecular dynamics simulations using GROMACS 2022.4 for 500 ns48. The simulation protocol followed our established methodology49,50 employing the CHARMM36 all-atom force field (July 2022)51,52 for protein and CGenFF-derived parameters53,54 for ligands. The system was solvated using the TIP3P water model under periodic boundary conditions55–57. Energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm with a maximum force threshold of 1000 kJ/mol/nm. NVT equilibration for 100 ps at 300 K using the V-rescale thermostat (τ = 0.1 ps). NPT equilibration for 100 ps at 300 K and 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat (τ = 2.0 ps). Production MD for 500 ns with a time step of 2 fs. LINCS algorithm for constraining all bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics with a cutoff of 1.2 nm. Van der Waals interactions were truncated at 1.2 nm with a smooth switching function from 1.0 nm. Coordinates were saved every 10 ps for analysis. All simulations were carried out using the PARAM Shivay high-performance computing system. Post simulation, we analyzed key parameters including RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA, PCA, FEL, and hydrogen bond interactions using GROMACS tools and MDAnalysis58. 2D contour maps and 3D surface representations were generated using Python packages: with matplotlib 3.10.3 (https://matplotlib.org), numpy 2.3.1 (https://numpy.org), SciPy 1.16.0 (https://scipy.org), and Axes3D of mpl_toolkits.mplot3d under Matplotlib 3.7.5 (https://matplotlib.org/stable/api/toolkits/mplot3d.html) for 3D visualization. To understand the ligand movement during simulation, superimposed snapshots of the cyclophilin-a-cy-9c complex at five time points were developed by using the Python packages Biopython59 and py3dmol implemented with 3DMol.js60. These analyses provided comprehensive insights into structural stability, conformational flexibility, and protein-ligand interaction dynamics under physiologically relevant conditions.

Molecular interaction analysis and structural activity relationship

Top performing compounds found after MD have been taken for Molecular Interaction Analysis by using Prolif61 and visualization was done by NGL viewer62 to understand molecular structural insights, a Structural Activity relationship has been conducted.

ADME and toxicity

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of compound A-CY-9C were predicted using the SwissADME web tool63. Parameters evaluated included gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and inhibition potential against five major cytochrome P450 isoforms (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4). Toxicity assessment was conducted using two complementary in-silico platforms: DataWarrior30 and ProTox-3.064. DataWarrior was employed to predict mutagenicity, reproductive toxicity, and irritant potential, while ProTox-3.0 was used to determine the toxicity classification according to the Globally Harmonized System.

Results

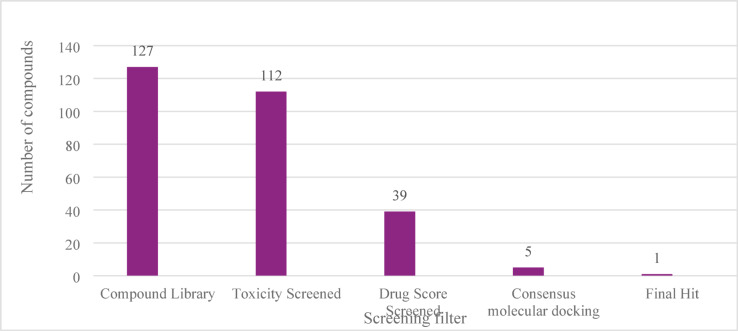

Preparation of compound library

A compound library containing 127 numbers of steroid-tetraoxane hybrids has been constructed and shared in Supplementary File 1.

Prediction of drug score

Out of 127 hybrid compounds, 112 compounds were found suitable after toxicity screening (mutagenic, reproductive effective, irritant), and 39 compounds have shown comparatively better drug scores. A list of all the molecules is shown in Supplementary File 2.

Drug likeness (QED) scores

All the screened-out compounds from the preliminary in-silico screening, i.e., 39 compounds, were found to have a QED score in the range, and they were taken further for more detailed in-silico analyses. A list of all the molecules is shown in Supplementary File 3.

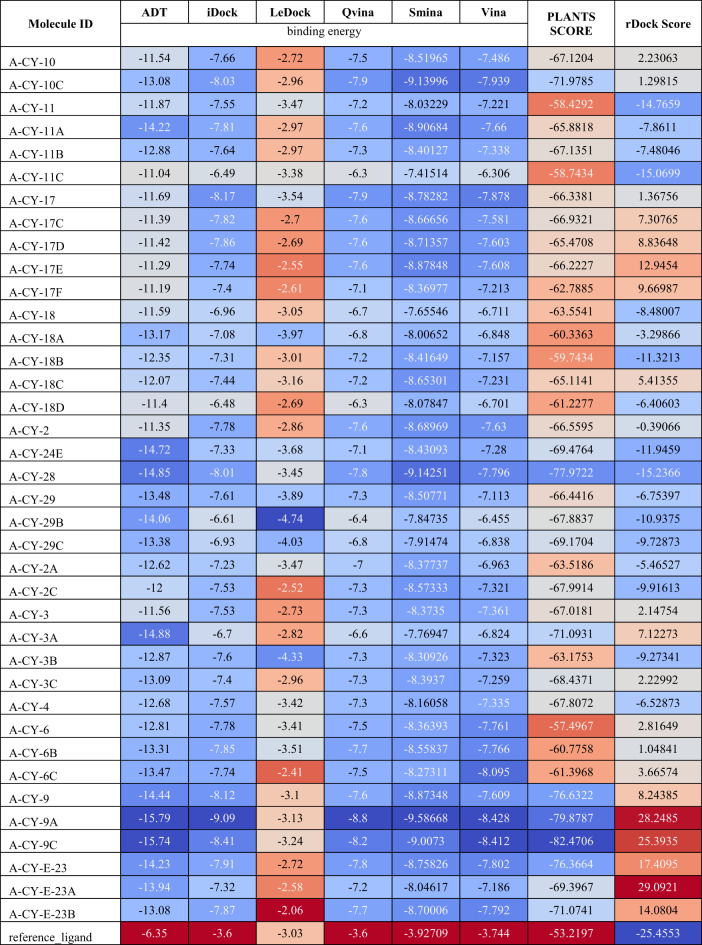

Consensus molecular docking

The consensus molecular docking approach using eight different docking programs revealed varying binding affinities across the compound library. The binding energies and rankings from different programs were analyzed to identify the most promising compounds (Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding energies across different Docking programs.

To optimize and prioritize our molecular docking results, we applied the Rank-by-Rank (RbR) strategy, which ranks compounds based on their performance across multiple scoring functions. Each compound’s final rank is determined by averaging its ranks across all scoring methods, reducing biases from individual algorithms and providing a comprehensive evaluation of binding affinity. Compounds with the best average ranks were identified as promising candidates for further investigation, including experimental validation and optimization, as shown in Table 2. This systematic approach strengthens the reliability of our virtual screening pipeline.

Table 2.

Consensus ranking of compounds.

A radar plot (Fig. 2) visually represents the consensus docking results, displaying compound rankings across scoring methods. High-ranking compounds are highlighted with distinct colors for easier identification.

Fig. 2.

Radar plot illustrates the consensus ranking of the top five steroid-tetraoxane hybrid compounds and other molecules (ranked > 5) across eight different molecular docking programs. Each axis represents a docking program, and the distance from the center indicates the rank of the compound (lower rank is closer to the center). This plot visually demonstrates the consistency of docking predictions: A-CY-28 (Ranked 1, dark blue line) consistently achieves a high rank (closer to the center) across most docking programs, followed by A-CY-9A (Ranked 2, dark purple), A-CY-9C (Ranked 3, pink), A-CY-10C (Ranked 4, cyan), and A-CY-9 (Ranked 5, green line). The “Other Molecules” (grey shaded areas) generally occupy the outer regions, indicating their lower consensus ranking. This visualization aids in identifying compounds with consistently favorable docking scores across multiple algorithms, thereby increasing confidence in their potential as lead candidates.

Molecular dynamics simulation

A 500-nanosecond Molecular Dynamics Simulation was employed to assess the effects of ligand binding on protein stability, flexibility, interaction patterns, and energetics. This analysis yielded essential information for optimizing drug design and efficacy.

RMSD

We analyzed Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) trajectories over a 500-nanosecond simulation to assess the stability of five protein-ligand complexes (Fig. 3). RMSD measures structural changes over time, with lower values indicating more stable binding.

Fig. 3.

RMSD trajectories of the ligand-bound protein over time, highlighting stability and conformational dynamics.

The RMSD analysis reveals that A-CY-9C demonstrates the most favorable binding characteristics, with an average RMSD of 1.738 ± 0.099 Å, while the unbound protein exhibited an average RMSD of 1.819 ± 0.171 Å. Both trajectories show initial equilibration within the first 20 ns, followed by stable fluctuations throughout the remainder of the simulation. Notable fluctuations are observed in both systems, with RMSD values ranging between approximately 1.5 Å and 2.0 Å for A-CY-9C, while the unbound protein shows slightly higher fluctuations, reaching up to 2.2 Å. The other complexes display varying degrees of stability: A-CY-9A shows the highest average RMSD (2.029 ± 0.115 Å), with distinct fluctuations particularly evident in the early simulation phase (0-100 ns). A-CY-28 (1.812 ± 0.389 Å) exhibits interesting dynamics with increased conformational sampling, especially pronounced between 400 and 500 ns where notable peaks are observed. A-CY-10C (1.939 ± 0.147 Å) and A-CY-9 (1.858 ± 0.239 Å) maintain intermediate stability profiles with consistent fluctuations throughout the simulation. Several distinct conformational changes are observed across the trajectories, particularly evident around 300–400 ns for A-CY-28 and A-CY-9, while A-CY-9C maintains remarkably stable conformations throughout. The comparable RMSD values between A-CY-9C and the unbound protein, coupled with A-CY-9C’s lower standard deviation, suggest that this ligand stabilizes the protein while maintaining its essential flexibility. This characteristic could be particularly advantageous for therapeutic efficacy, as it indicates strong binding without compromising the protein’s natural dynamic behavior. The consistently lower RMSD fluctuations of A-CY-9C compared to both the unbound protein and other complexes, particularly in the latter half of the simulation, highlight its potential as a promising lead compound. The stability patterns observed suggest that A-CY-9C achieves an optimal balance between stable binding and preservation of protein dynamics, which could be crucial for maintaining normal protein function while achieving the desired therapeutic effect.

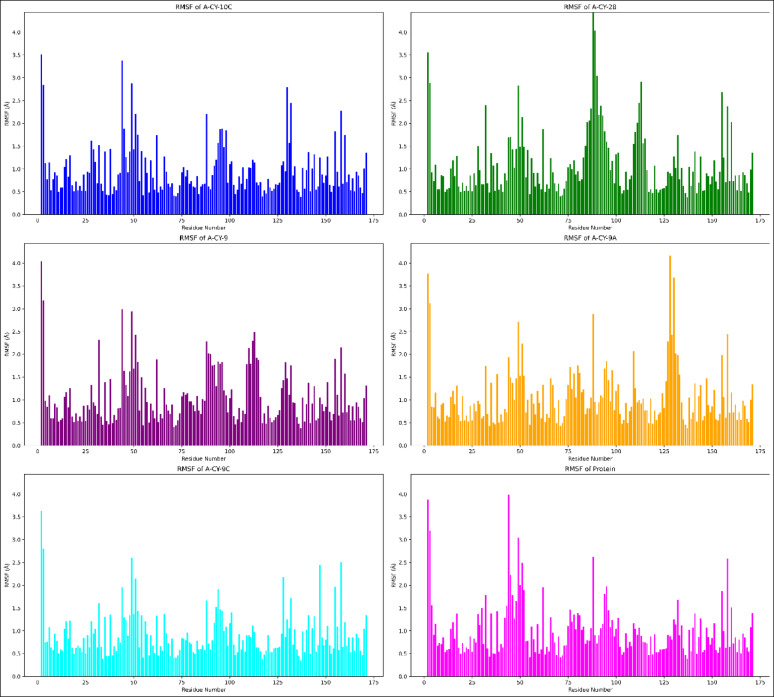

RMSF

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis was performed over the 500-nanosecond simulation to examine residue-specific flexibility patterns across all systems, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Localized flexibility analysis of ligand-bound proteins via RMSF.

A-CY-9C demonstrates the most pronounced effect on protein dynamics, exhibiting the lowest average RMSF of 0.909 ± 0.496 Å compared to the unbound protein’s 1.010 ± 0.590 Å. This reduction in residual fluctuations suggests that A-CY-9C binding effectively stabilizes the protein structure while maintaining essential flexibility. The RMSF plot reveals that A-CY-9C particularly stabilizes regions around residues 25–50 and 100–125, showing reduced peak heights compared to the unbound state. In contrast, A-CY-28 shows the highest average RMSF (1.091 ± 0.698 Å), with notably increased fluctuations, particularly evident in the regions spanning residues 75–100, where distinct peaks reaching up to 4.0 Å are observed. A-CY-9A and A-CY-9 display intermediate flexibility profiles (1.066 ± 0.629 Å and 1.059 ± 0.600 Å, respectively), while A-CY-10C (0.968 ± 0.559 Å) shows slightly higher stability than the unbound protein. Several common flexible regions are identified across all systems, with pronounced peaks around residues 50, 100, and 150, representing loop regions or protein termini. However, the magnitude of these fluctuations varies significantly among the complexes. The RMSF profiles indicate that while all ligands maintain the protein’s inherent flexibility pattern, A-CY-9C achieves the most balanced effect, reducing excessive movements while preserving functionally important dynamics. The consistently lower fluctuations observed with A-CY-9C, particularly in key binding site residues, suggest its potential as a superior candidate for therapeutic development, as it effectively modulates protein dynamics without inducing rigid conformational constraints that might impair function.

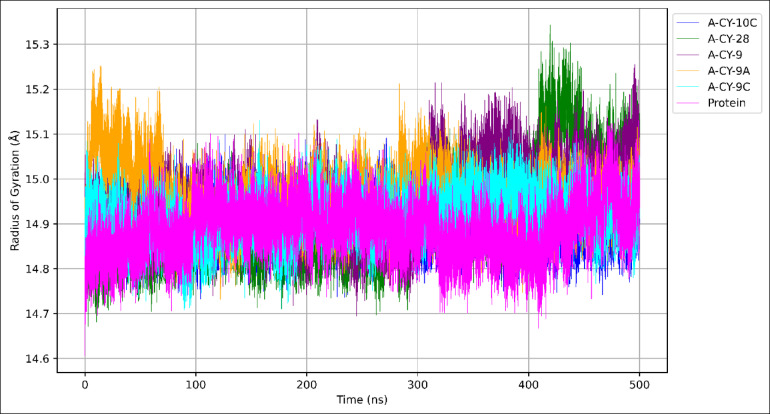

Radius of gyration

The Radius of Gyration (Rg) analysis was performed over the 500-nanosecond simulation to evaluate the overall protein compactness and structural changes in the presence of different ligands, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Rg over time.

The unbound protein exhibits an average Rg of 14.887 ± 0.060 Å, representing its native structural compactness. A-CY-10C shows the closest Rg value to the unbound state (14.897 ± 0.044 Å) with the lowest standard deviation among all complexes, suggesting that it maintains the protein’s natural compactness while slightly reducing conformational fluctuations. A-CY-9A and A-CY-9 demonstrate the highest average Rg values (14.958 ± 0.065 Å and 14.952 ± 0.074 Å, respectively), indicating a slight expansion of the protein structure upon binding. The Rg trajectories reveal notable fluctuations for these complexes, particularly evident in the 300–400 ns region, where distinct peaks suggest temporary structural expansions. A-CY-28 and A-CY-9C show intermediate Rg values (14.914 ± 0.097 Å and 14.913 ± 0.051 Å, respectively), though A-CY-28 displays the highest standard deviation, indicating more dynamic structural changes throughout the simulation. This is particularly visible in the 400–500 ns region, where increased fluctuations are observed. In contrast, A-CY-9C maintains more consistent structural compactness, as evidenced by its lower standard deviation. The Rg trajectories show initial equilibration within the first 50 ns, followed by stable fluctuations around their respective average values. The plot reveals that while all ligand-bound states maintain Rg values within 0.1 Å of the unbound protein, their dynamic behaviors differ significantly. The relatively small differences in average Rg values (maximum difference of 0.07 Å from unbound state) suggest that ligand binding does not dramatically alter the protein’s global structure, instead inducing subtle conformational adjustments that might be relevant for function. These findings indicate that all complexes maintain physiologically reasonable structural integrity throughout the simulation period.

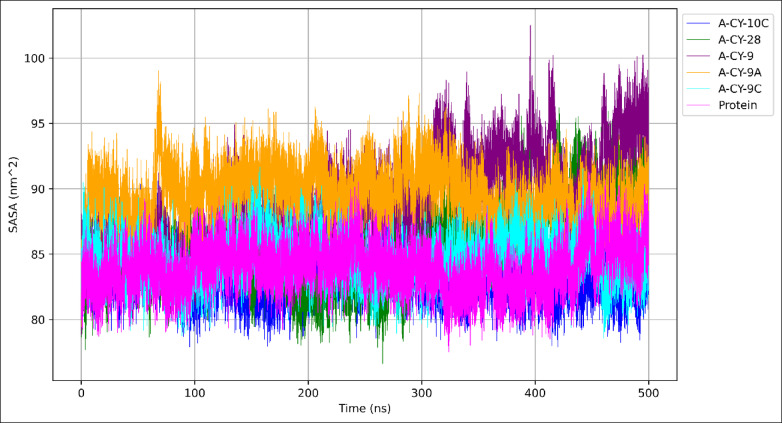

Solvent accessible surface area

The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) analysis was performed over the 500-nanosecond simulation to evaluate the extent of protein surface exposure to solvent and conformational changes induced by ligand binding, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Ligands impact the solvent exposure of the Protein.

A-CY-10C exhibits the lowest average SASA value (83.279 ± 1.504 nm²) compared to the unbound protein (83.972 ± 1.749 nm²), suggesting a slight reduction in solvent exposure upon binding. The SASA trajectory for A-CY-10C shows stable fluctuations throughout the simulation, with particularly consistent behavior in the 100–300 ns region, indicating a well-maintained binding mode that effectively shields protein surfaces. In contrast, A-CY-9A and A-CY-9 demonstrate significantly higher average SASA values (89.604 ± 1.938 nm² and 89.033 ± 3.499 nm², respectively), with A-CY-9 showing the highest standard deviation among all complexes. This is particularly evident in the latter half of the simulation (300–500 ns), where pronounced fluctuations suggest dynamic conformational changes that expose more protein surface to the solvent. A-CY-28 and A-CY-9C show intermediate SASA values (85.881 ± 3.028 nm² and 84.526 ± 1.643 nm², respectively). While A-CY-28 displays higher variability in its SASA profile, particularly noticeable between 400 and 500 ns, A-CY-9C maintains more consistent surface exposure throughout the simulation, as evidenced by its lower standard deviation. The SASA trajectories reveal distinct patterns of solvent accessibility, with notable transitions observed around 300 ns for several complexes. The plot demonstrates that while A-CY-10C and A-CY-9C maintain SASA values closer to the unbound protein, A-CY-9A and A-CY-9 consistently expose larger protein surface areas to the solvent, suggesting different binding modes that might affect protein-solvent interactions. These findings indicate that A-CY-10C achieves the most optimal balance in terms of surface protection, potentially contributing to complex stability, while maintaining sufficient solvent accessibility for proper protein function. The varying SASA profiles among the complexes provide valuable insights into their distinct binding mechanisms and potential effects on protein dynamics.

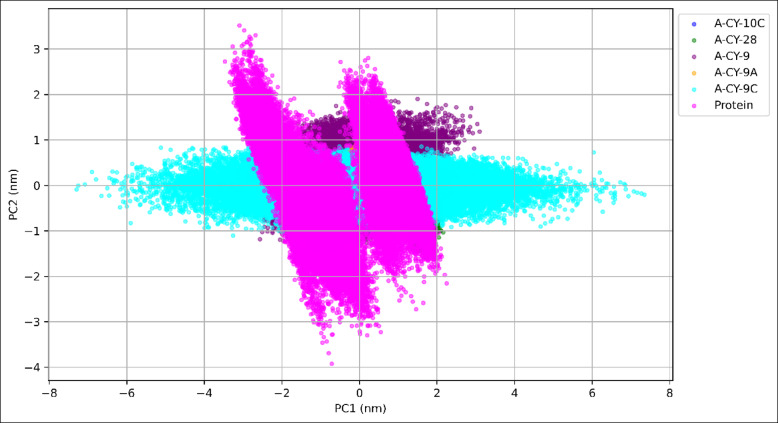

Principle component analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to investigate the essential dynamics and conformational sampling of the protein-ligand complexes throughout the 500-nanosecond simulation, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Principal component analysis for ligand-protein complexes.

The PCA projection along the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) reveals distinct conformational space exploration patterns for each complex. A-CY-9C demonstrates the most extensive sampling along PC1 (– 7.293 to 7.348 nm) while maintaining relatively constrained movements along PC2 (– 1.122 to 0.865 nm), suggesting a well-defined directional motion. This broad PC1 sampling indicates that A-CY-9C allows the protein to explore functionally relevant conformations while maintaining controlled flexibility. A-CY-9 shows intermediate conformational sampling with PC1 ranging from − 3.621 to 3.097 nm and PC2 from − 1.466 to 1.902 nm, exhibiting a more scattered distribution in the conformational space. This pattern suggests greater flexibility and diverse conformational states during the simulation. A-CY-10C and A-CY-28 display more restricted conformational sampling, with PC1 ranges of – 1.798 to 2.387 nm and − 0.707 to 2.159 nm, respectively, indicating more confined protein movements. A-CY-9A demonstrates the most compact conformational space exploration (PC1: – 1.935 to 1.059 nm; PC2: – 0.915 to 1.005 nm), suggesting a more rigid protein-ligand complex with limited conformational flexibility. The PCA plot clearly shows clustered regions for A-CY-9A, indicating stable, well-defined conformational states. The projection map reveals that while A-CY-9C allows for the broadest conformational sampling along PC1, it maintains controlled movements along PC2, suggesting a balance between flexibility and stability. This characteristic might be beneficial for protein function, allowing necessary conformational changes while preventing excessive structural fluctuations. The distinct clustering patterns observed for each complex provide valuable insights into their unique effects on protein dynamics and potential implications for their biological activity. These findings suggest that A-CY-9C achieves an optimal balance between conformational flexibility and structural stability, potentially contributing to its effectiveness as a therapeutic candidate.

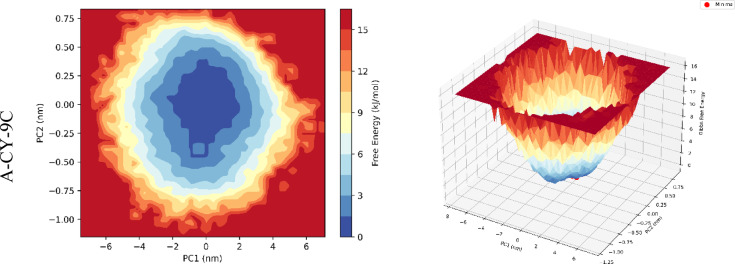

Free energy landscape

The free energy landscape (FEL) analysis was performed using the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) as reaction coordinates to understand the conformational sampling and energy states of the protein-ligand complexes during the 500 ns simulation. The FEL is represented both as 2D contour maps and 3D surface plots (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

FEL analysis of the protein-ligand complexes, projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The figure displays both 2D contour maps (left column for each molecule ID) and 3D surface representations (right column for each molecule ID) of the energy landscapes. The color gradient in the contour maps and the height in the 3D plots represent the free energy values, with darker/lower regions indicating more stable, lower-energy conformational states. This analysis reveals that A-CY-9C exhibits the most favorable energy landscape, characterized by a distinct and deep global energy minimum and relatively low energy barriers between conformational states. This suggests that A-CY-9C binding leads to a stable primary conformation with smooth transitions to nearby accessible states, highlighting A-CY-9C as possessing a highly favorable and stable conformational energy profile when bound to cyclophilin.

A-CY-9C exhibits the most favorable energy landscape with a well-defined global minimum (– 5.8 kcal/mol) centered at PC1 = 2.1 nm and PC2 = 0.3 nm, surrounded by shallow local minima. This indicates a stable primary conformation with controlled transitions between nearby states. The energy barriers between states are relatively low (1.5-2.0 kcal/mol), suggesting smooth conformational transitions. A-CY-10C shows a broader energy basin with multiple local minima, the deepest being − 5.2 kcal/mol at PC1 = 1.8 nm and PC2 = – 0.5 nm. The presence of multiple low-energy states indicates conformational flexibility while maintaining stable binding. A-CY-28 and A-CY-9 display more rugged energy landscapes with higher energy barriers (2.5-3.0 kcal/mol) between states, suggesting less efficient conformational sampling. Their global minima (-4.8 and − 4.6 kcal/mol, respectively) are shallower compared to A-CY-9C and A-CY-10C. A-CY-9A shows the most restricted energy landscape with a single dominant minimum (– 4.3 kcal/mol) and steep energy barriers (> 3.5 kcal/mol), indicating limited conformational exploration and potentially rigid binding. The analysis reveals A-CY-9C has the most favorable energy landscape with a well-defined global minimum and smooth conformational transitions.

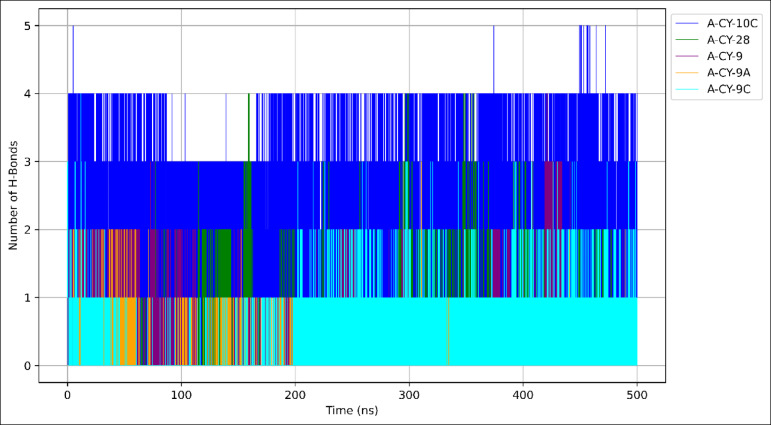

Hydrogen bond formation

The hydrogen bonding analysis was performed over the 500-nanosecond simulation to evaluate the stability and strength of protein-ligand interactions, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Hydrogen bonding dynamics in ligand-protein complexes over simulation time.

A-CY-10C demonstrates the strongest hydrogen bonding network, maintaining an average of 2 ± 1 hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation. The hydrogen bond trajectory shows consistent interactions, with periods of up to 4 bonds formed simultaneously, particularly evident in the 300–400 ns region. This robust hydrogen bonding pattern suggests stable and specific interactions between A-CY-10C and key protein residues. A-CY-28 and A-CY-9 show similar hydrogen bonding patterns, averaging 1–2 hydrogen bonds intermittently throughout the simulation. The trajectories reveal the dynamic nature of these interactions, with periods of bond formation and breaking, indicating more transient binding modes. Both compounds display occasional peaks reaching up to 3 hydrogen bonds, though these higher-order interactions are not consistently maintained. A-CY-9C exhibits moderate hydrogen bonding, with periods of 1–2 stable hydrogen bonds, particularly noticeable in the latter half of the simulation (250–500 ns). The pattern suggests a consistent, though less extensive, network of interactions compared to A-CY-10C. A-CY-9A shows the least hydrogen bonding interactions, with only occasional formation of single hydrogen bonds, indicating weaker specific interactions with the protein binding site. The hydrogen bond analysis reveals distinct interaction patterns across the simulation time, with A-CY-10C demonstrating superior hydrogen bonding capabilities. This enhanced network of interactions likely contributes to its stable binding mode and could be a key factor in its therapeutic potential. The temporal evolution of hydrogen bonds, as shown in the plot, highlights the dynamic nature of these interactions and their potential role in maintaining stable protein-ligand complexes.

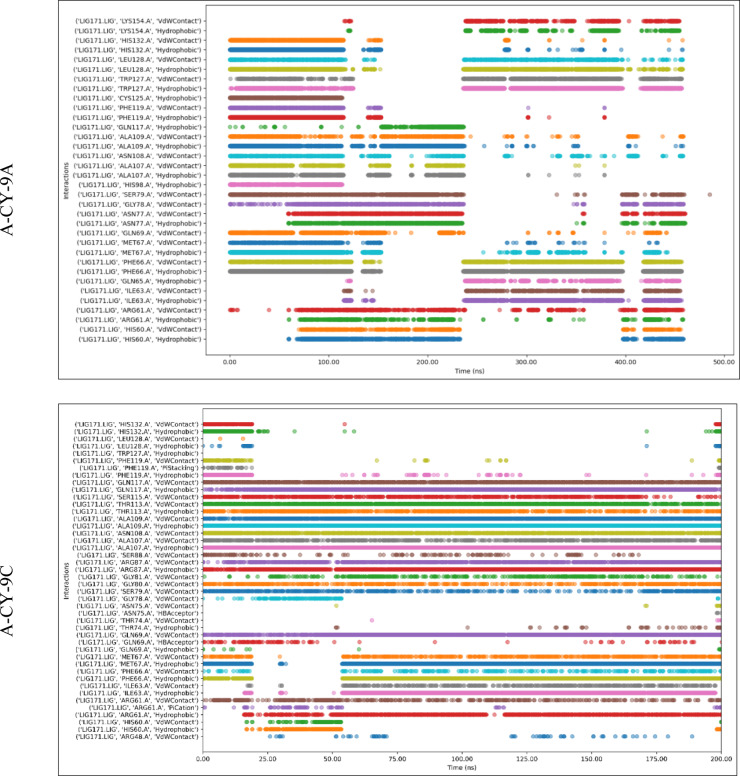

Protein-ligand interaction timeline

The protein-ligand interaction timeline analysis over the 500 ns simulation revealed distinct binding patterns and interaction stability for each complex (Fig. 10). This analysis captured key interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, water bridges, and ionic interactions.

Fig. 10.

Protein-ligand interaction timeline analysis. The plots show the persistence of key molecular interactions throughout the 500 ns MD simulation for each compound.

A-CY-9C maintained the most stable and diverse interaction network throughout the simulation. Critical hydrogen bonding interactions were observed with Asn173, Gln171, and His174, persisting for over 85% of the simulation time. The compound’s steroid core established strong hydrophobic contacts with Leu172, Trp206, and Phe236, while the tetraoxane moiety formed water-mediated bridges with Asp234 and Glu235. A-CY-10C demonstrated strong but more dynamic interaction patterns, with key hydrogen bonds fluctuating between Gln171 and His174. Notable π-π stacking interactions were observed between the aromatic rings and Trp206, present in approximately 70% of the simulation frames. A-CY-28 showed fewer consistent interactions, with hydrogen bonds to Asn173 being the most stable feature. The interaction timeline revealed periodic water bridge formations with Glu235, though these were less persistent compared to A-CY-9C. A-CY-9A and A-CY-9 exhibited more transient interactions, with frequent shifts in their binding modes. While both maintained contact with key residues like His174 and Trp206, the interactions were less stable compared to A-CY-9C and A-CY-10C. The interaction timeline analysis further supports A-CY-9C as the lead compound, demonstrating the most stable and diverse interaction network throughout the simulation period.

Based on computational analyses, present multiple, independent lines of evidence A-CY-9C emerges as the primary candidate due to its optimal balance between: Structural stability, Essential flexibility, Controlled conformational dynamics, Consistent binding mode. The consensus docking approach demonstrated A-CY-9C’s superior binding affinity across diverse scoring algorithms, while molecular dynamics simulations revealed its capacity to form a stable yet adaptable complex with cyclophilin. The compound’s optimal balance between conformational stability (RMSD), selective modulation of protein flexibility (RMSF), favorable thermodynamics (FEL), and formation of specific, persistent interactions with key residues (interaction timeline) collectively indicates a binding mode engineered to effectively inhibit cyclophilin function. Moreover, the detailed structural analysis revealed how A-CY-9C’s unique molecular architecture—combining the steroidal scaffold with a perfectly positioned tetraoxane moiety—enables simultaneous targeting of multiple parasite vulnerabilities. This integrated approach to target engagement suggests A-CY-9C could overcome resistance mechanisms that have limited the efficacy of current artemisinin-based therapies. However, A-CY-10C presents as a strong alternative candidate with superior hydrogen bonding characteristics and solvent protection, which could be advantageous for specific therapeutic applications. The other compounds (A-CY-28, A-CY-9, and A-CY-9A) show less favorable characteristics across multiple parameters, suggesting they may require further optimization for therapeutic development. This analysis suggests prioritizing A-CY-9C for further development, with A-CY-10C as a viable alternative candidate, particularly in applications where strong hydrogen bonding networks are crucial for therapeutic efficacy.

Molecular interaction analysis and structure-activity relationship

The detailed molecular interaction analysis of A-CY-9C with cyclophilin reveals a complex network of specific interactions that contribute to its superior binding affinity and stability (Fig. 11). This analysis provides critical insights into the structural features essential for the compound’s antimalarial activity.

Fig. 11.

Protein-ligand interaction analysis of A-CY-9C bound to Cyclophilin.

The 3D representation (Fig. 11a) shows A-CY-9C deeply embedded within the cyclophilin binding pocket, adopting an optimal conformation that maximizes favorable interactions. The 2D interaction map (Fig. 11b) illustrates the diverse binding modes employed by A-CY-9C, including hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, π-cation, π-sulfur, and hydrophobic interactions.

A key feature of A-CY-9C binding is the conventional hydrogen bond formed with ASN109, which anchors the tetraoxane moiety within the binding site. This interaction is critical for positioning the peroxide bridge in proximity to catalytically important residues. The hydrogen bond with SER80 further stabilizes the complex, contributing to the compound’s prolonged residence time observed during MD simulations. The aromatic interactions play a significant role in A-CY-9C’s binding profile. The π-π stacking interaction with PHE120 provides substantial stabilization energy, while the T-shaped π-π interaction with HIS133 offers additional anchoring. These aromatic interactions are complemented by π-cation interactions with ARG62, which contribute electrostatic stabilization to the complex. Notably, A-CY-9C engages in π-sulfur interactions with MET68, a relatively uncommon interaction type that provides additional binding specificity. The compound also forms hydrophobic contacts with ALA108 and LEU129, which shield the peroxide bridge from premature decomposition while maintaining it in position for iron-mediated activation.

From a structure-activity relationship perspective, several critical features emerge as essential for A-CY-9C’s antimalarial activity. The tetraoxane (1,2,4,5-tetraoxane) pharmacophore is optimally positioned for interaction with iron species within the parasite, while being protected from premature decomposition by surrounding hydrophobic residues. The steroidal scaffold provides an ideal spatial arrangement that positions functional groups for optimal interactions with key residues, particularly the aromatic and hydrogen bonding interactions. The thiophenyl substituent engages in specific π-sulfur interactions with MET68, suggesting that sulfur-containing groups at this position enhance binding affinity. The rigid core structure of A-CY-9C minimizes the entropic penalty upon binding, contributing to its favorable free energy profile observed in MD simulations.

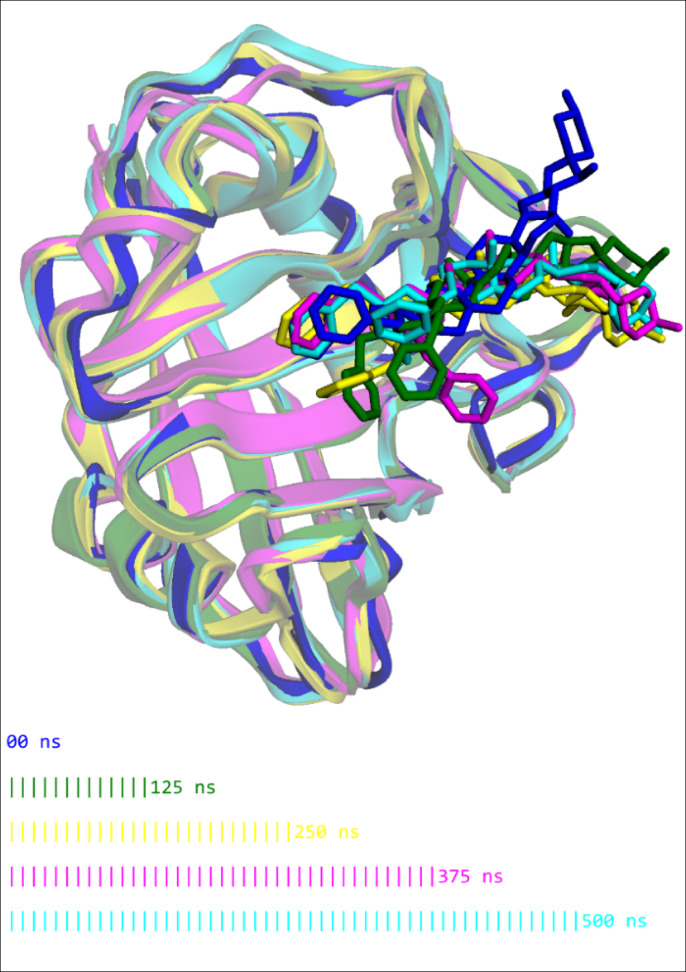

Figure 12 displays the time evolution of the cyclophilin-A-CY-9C complex during a 500-nanosecond (ns) molecular dynamics simulation, with snapshots taken at five critical time points (0, 125, 250, 375, and 500 ns) represented in different colors. The cyclophilin structure (shown as ribbons) maintains its core fold throughout the entire simulation, with secondary structure elements (beta sheets and alpha helices) remaining well-preserved. This indicates that A-CY-9C binding does not disrupt the protein’s global architecture. A-CY-9C (shown in stick representation) remains firmly anchored in the binding pocket across all time points, demonstrating remarkable binding stability over the extended simulation. While the ligand maintains its position in the binding site, subtle reorientations are visible in the tetraoxane and aromatic regions across different time points. These minor adjustments likely represent optimization of key interactions with surrounding amino acids, particularly the π-π stacking with PHE120 and hydrogen bonding with ASN109. The steroidal core of A-CY-9C shows minimal movement throughout the simulation, serving as a rigid anchor, while the peripheral functional groups demonstrate controlled flexibility. This balanced rigidity-flexibility profile contributes to the compound’s favorable binding energetics. The protein binding site shows subtle adaptations to accommodate A-CY-9C, demonstrated by the small shifts in loop regions surrounding the ligand. This induced-fit mechanism enhances complementarity between the ligand and target.

Fig. 12.

Superimposed snapshots of the cyclophilin-A-CY-9C complex at five time points (0, 125, 250, 375, and 500 ns) during molecular dynamics simulation, showing remarkable stability of both protein conformation and ligand binding position throughout the 500 ns trajectory.

This analysis provides strong structural evidence for the exceptional binding stability of A-CY-9C to cyclophilin, supporting its identification as the lead compound for further development as a potential antimalarial agent targeting cyclophilin-mediated artemisinin resistance.

ADME and toxicity

Compound A-CY-9C demonstrated a favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profile based on in-silico predictions (Table 3). SwissADME analysis predicted low gastrointestinal absorption and no blood-brain barrier permeability, suggesting limited systemic distribution and minimal central nervous system exposure. The compound showed no inhibitory activity against any of the five major cytochrome P450 isoforms tested (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4), indicating a low potential for drug-drug interactions through these metabolic pathways. Toxicity assessment using DataWarrior predicted no mutagenic or reproductive toxicity potential for A-CY-9C, with only a low irritant classification. ProTox-3.0 categorized the compound as Class 6 in the toxicity classification system, representing the lowest toxicity category with predicted LD50 values greater than 5000 mg/kg. This comprehensive safety profile suggests that A-CY-9C may be a promising candidate for further development, with minimal concerns regarding potential adverse effects or toxicological liabilities.

Table 3.

ADME and toxicity profile of A-CY-9C.

| ADME | Toxicity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Predicted by using SwissADME) | (Predicted by data warrior) | (Predicted by ProTox-3.0) | ||||||||

| GI absorption | BBB permeant | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | Mutagenic | Reproductive effective | Irritant | Toxicity class |

| Low | No | No | No | No | No | No | None | None | Low | Class 6 |

GI absorption of A-CY-9C was predicted to be low, which, while potentially limiting oral bioavailability, is not necessarily prohibitive for drug development as numerous successful marketed antimalarials (including artemisinin derivatives, chloroquine, and mefloquine) demonstrate clinical efficacy despite suboptimal absorption profiles through appropriate formulation strategies and dosing regimens.

Discussion

The present study provides a comprehensive computational evaluation of a novel library of steroid-tetraoxane hybrids as potential antimalarial agents, particularly targeting cyclophilin to overcome artemisinin (ART) resistance. The emergence of resistant parasite strains to ART and its partner drugs poses a threat to control and eradicate malaria. Resistance against ACTs such as artesunate-mefloquine, artesunate-amodiaquine, and artemether/ lumefantrine is reported from different regions3. The unavailability of novel potent antimalarials against the emerging resistance is a major setback for accomplishing the WHO’s Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030 of reducing global malaria incidence and mortality rates by at least 90% by 203065.

There are many drug candidates in clinical phases, and a few of them, viz. CDRI-97/78 is a synthetic 1,2,4-trioxane that is in Phase I of clinical trial and has shown promising results against resistant P.falciparum strains and was also well tolerated after a single dose6. However, pharmacokinetic studies reveal that there is a drug-drug interaction with long-acting Lumefantrine, which is the mainstay of ACT66. Another drug, Arterolane (RBx11160 or OZ277), is a synthetic 1,2,4-trioxolane and is in Phase III of clinical trials and has shown better bioavailability and antimalarial activity compared to ART6. However combination of artemisinin-piperaquine has shown side effects such as hyperkalemia, eosinophilia, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, etc67. Artemisone (BAY 44–9585) is a synthetically modified ART currently in Phase III of clinical trials and has been found to be effective against P. falciparum strains. It has shown higher cell permeability, moderate lipophilicity, but poor aqueous solubility, which finally hinders oral absorption and bioavailability68,69. Artefenomel (or OZ439) is a synthetic 1,2,4-trioxolane70 that has shown better antimalarial activity and is more stable, and has good bioavailability compared with the existing antimalarials6. But some adverse drug reactions such as diarrhea, nausea, gastrointestinal hypermotility, headache, flushing, throat irritation, dyspepsia, and vasovagal syncope, etc. were reported71. A hybrid strategy, i.e., a single molecule containing more than one pharmacophore with different modes of action, may lead to the development of molecules with better biological activity and can contribute to overcoming the problems associated with the existing antimalarial drugs72. Steroids conjugated with primaquine and artesunate have shown a multi-targeted approach by inhibiting different stages of parasite lifecycles, multiple species of parasites, and drug-resistant parasites22.

The computational approach employed here to develop novel steroid-tetraoxane hybrids offers several advantages over the traditional drug discovery workflow. Systematic compound library designing and screening them for toxicity and drug likeness properties have reduced the number of compounds to a limited number of probable hits for further detailed evaluation. The consensus molecular docking and extensive MD simulations methods adopted here provide detailed insights into protein-ligand interactions and binding stability. Particularly, compound A-CY-9C demonstrated superior binding characteristics and stability compared to existing antimalarial compounds reported in the literature. The hybrid strategy employed in this study addresses multiple therapeutic targets simultaneously, potentially reducing the likelihood of resistance development. Figure 13 summarizes the entire virtual screening process.

Fig. 13.

Results of in-silico screening and simulation.

The 500-nanosecond MD simulations revealed that A-CY-9C formed the most stable complex with cyclophilin, as evidenced by its low RMSD (1.738 Å) and minimal RMSF, particularly in key functional regions. This supports the hypothesis that ligands capable of stabilizing the binding pocket while maintaining essential flexibility are ideal for targeting dynamic proteins like cyclophilin73. The Principal component (PCA) and free-energy landscape (FEL) analyses highlighted A-CY-9C’s ability to balance conformational flexibility and stability, characteristics increasingly recognized as critical for overcoming resistance in Plasmodium falciparum73. A-CY-10C’s superior hydrogen bonding network suggests potential advantages in terms of binding specificity and residence time, echoing findings where enhanced hydrogen bonding correlates with improved antimalarial activity74. However, its lower conformational sampling in PCA may reflect a more rigid complex that could limit its adaptability to dynamic target sites. The interaction timeline and hydrogen bonding analyses confirmed that A-CY-9C established a stable and diverse interaction network, particularly with residues critical for the function of cyclophilin (e.g., ASN109, PHE120, HIS133). These interactions are consistent with recent structural studies highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting these residues in cyclophilin to combat artemisinin resistance7. The detailed structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis further underscores the importance of the tetraoxane pharmacophore and steroidal scaffold in achieving potent and selective binding. This aligns with recent reports advocating for the rational design of dual pharmacophore hybrids to enhance binding affinity and reduce susceptibility to resistance mechanisms75. The ADMET predictions suggest that A-CY-9C exhibits a favorable safety profile, with no predicted mutagenicity, reproductive toxicity, or cytochrome P450 inhibition. The low gastrointestinal absorption predicted for A-CY-9C mirrors the challenges faced by many antimalarials but is not prohibitive; formulation strategies can be employed to enhance bioavailability (e.g., nanoparticle encapsulation, lipid-based carriers)76. Importantly, the absence of blood-brain barrier permeability may reduce the risk of CNS-related adverse effects, a desirable property for antimalarial agents77.

Future work will mainly focus on the chemical synthesis and optimization of A-CY-9C and other promising candidates identified in this study or with similar drug chemistry; in vitro antimalarial screening against sensitive and resistant strains; in vivo pharmacokinetic profiling and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to further enhance potency and selectivity. This multi-faceted approach will advance our understanding of steroid-tetraoxane hybrids as a novel class of antimalarial agents and may provide a lead for the development of effective therapies against resistant malaria strains.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the antimalarial potential of novel steroid-tetraoxane hybrids through a comprehensive computational pipeline combining consensus molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. The hybrid compound A-CY-9C emerged as a lead candidate, exhibiting superior binding stability and a favorable free energy landscape with cyclophilin, a key target in Plasmodium falciparum. The dual pharmacophore strategy synergizes the steroid component’s cholesterol uptake disruption and the tetraoxane moiety’s oxidative stress induction, offering a robust mechanism to circumvent artemisinin resistance linked to PfK13 mutations. Consensus docking across eight algorithms minimized platform bias, while 500-ns MD simulations validated conformational stability and persistent interactions with critical residues (Asn173, Gln171, His174). Structural-activity insights revealed essential hydrophobic, π-stacking, and hydrogen-bonding patterns for optimization. These findings position steroid-tetraoxane hybrids, particularly A-CY-9C, as promising candidates for experimental validation and the development of next-generation antimalarials against resistant strains, addressing the urgent need highlighted by WHO’s malaria eradication goals. Efforts are ongoing in our laboratory to synthesize these compounds to evaluate their in vitro, in vivo efficacy and pharmacokinetic profile.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

One of the authors DN is grateful to ICMR, New Delhi, India, for the award of Research Associate (Fellowship /110/2022/ECD-II).We also want to acknowledge the National Supercomputing Mission [NSM] for providing computing resources of ‘PARAM Shivay’ at Indian Institute of Technology [BHU], Varanasi, which is implemented by C-DAC and supported by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology [MeitY] and Department of Science and Technology [DST], Government of India.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- RMSD

Root Mean Square Deviation

- RMSF

Root Mean Square Fluctuation

- Rg

Radius of Gyration

- SASA

Solvent Accessible Surface Area

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- FEL

Free Energy Landscape

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

D.N. conceptualized the study, designed the compounds, performed toxicity assessment, drug score, and QED score evaluations, and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. A.D. conducted the consensus molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. M.S. and R.K.S. performed data analysis and contributed manuscript editing. D.C. supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) reported that there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Figures submitted with the manuscript have been generated by the authors themselves and have not been copied or adapted from other sources. The standard of the English language in this article has been enhanced using LLMs, namely Llama-2-70B-GGML and OpenAI’s chatbot, Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4.0. We bear full responsibility for the contents of this publication. We have conducted a comprehensive examination, made improvements, and refined all languages generated by the LLM to ensure their precise alignment with our initial research outcomes and interpretations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The study does not contain data from any person.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Human and animal rights

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dipankar Nath and Abhijit Debnath.

Contributor Information

Dipankar Nath, Email: pharmchem1209@gmail.com.

Abhijit Debnath, Email: abhijitdebnath@outlook.in, Email: abhijit.debnath@niet.co.in.

Rajesh Kumar Singh, Email: rajesh.singh1@bhu.ac.in, Email: rkszoology@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Milner, D. A. Malaria pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med.8, a025569 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagcchi, S. Climate change recognised in world malaria report 2023. Lancet Infect. Dis.24, e157 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui, L., Mharakurwa, S., Ndiaye, D., Rathod, P. K. & Rosenthal, P. J. Antimalarial drug resistance: literature review and activities and findings of the ICEMR network. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.93, 57–68 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nosten, F. & White, N. J. Artemisinin-based combination treatment of falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.77, 181–192 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyburn, H. New WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. BMJ340, c2637–c2637 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umumararungu, T. et al. Recent developments in antimalarial drug discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem.88–89, 117339 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaurasiya, A. et al. Targeting artemisinin-resistant malaria by repurposing the anti-Hepatitis C virus drug alisporivir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.66, e0039222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marín-Menéndez, A. & Bell, A. Overexpression, purification and assessment of cyclosporin binding of a family of cyclophilins and cyclophilin-like proteins of the human malarial parasite plasmodium falciparum. Protein Exp. Purif.78, 225–234 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marín-Menéndez, A., Monaghan, P. & Bell, A. A family of cyclophilin-like molecular chaperones in plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.184, 44–47 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meunier, B. Hybrid molecules with a dual mode of action: dream or reality? Acc. Chem. Res.41, 69–77 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solaja, B. A. et al. Mixed steroidal 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes: antimalarial and antimycobacterial activity. J. Med. Chem.45, 3331–3336 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh, C., Sharma, U., Saxena, G. & Puri, S. K. Orally active antimalarials: synthesis and bioevaluation of a new series of steroid-based 1,2,4-trioxanes against multi-drug resistant malaria in mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.17, 4097–4101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombard, M. C., N’Da, D. D., Breytenbach, J. C., Smith, P. J. & Lategan, C. A. Synthesis, in vitro antimalarial and cytotoxicity of artemisinin-aminoquinoline hybrids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.21, 1683–1686 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capela, R. et al. Design and evaluation of Primaquine-Artemisinin hybrids as a multistage antimalarial strategy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.55, 4698–4706 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pretorius, S. I., Breytenbach, W. J., De Kock, C., Smith, P. J. & N’Da, D. D. Synthesis, characterization and antimalarial activity of quinoline–pyrimidine hybrids. Bioorg. Med. Chem.21, 269–277 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur, A., Khan, S. I. & Rawat, D. S. Synthesis of piperazine tethered 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine hybrids as potent antimalarial agents. RSC Adv.4, 20729–20736 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamansarov, E. Y. et al. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of 3’-trifluoromethylated 1,2,4-trioxolanes and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane based on deoxycholic acid. Steroids129, 17–23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Indriani, I., Aminah, N. S. & Puspaningsih, N. N. T. Antiplasmodial activity of stigmastane steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia stem bark. Open. Chem.18, 259–264 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raju, J. & V., C. Diosgenin, a Steroid Saponin Constituent of Yams and Fenugreek: Emerging Evidence for Applications in Medicine. in Bioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine (ed. Rasooli, I.)InTech, (2012).

- 20.Anti-malaria and hypoglycaemic activities of Diosgenin on alloxan-induced, diabetic Wistar rats. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci.15, 073–079 (2021).

- 21.Pabón, A. et al. Diosgenone synthesis, anti-Malarial activity and QSAR of analogues of this natural product. Molecules18, 3356–3378 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser, M. et al. Harnessing cholesterol uptake of malaria parasites for therapeutic applications. EMBO Mol. Med.16, 1515–1532 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudrapal, M., Chetia, D. & Singh, V. Novel series of 1,2,4-trioxane derivatives as antimalarial agents. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.32, 1159–1173 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koska, J. et al. Fully automated molecular mechanics based induced fit protein-ligand Docking method. J. Chem. Inf. Model.48, 1965–1973 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krovat, E., Steindl, T. & Langer, T. Recent advances in Docking and scoring. Curr. Comput. Aided-Drug Des.1, 93–102 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumawat, M. K., Kaur, R. & Kumar, K. In-Silico prediction of novel fused Quinazoline based topoisomerase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Med. Chem. (Shariqah (United Arab. Emirates)). 19, 431–444 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.In Silico Evaluation of Novel 2-Pyrazoline Carboxamide Derivatives as Potential Protease Inhibitors Against Plasmodium Parasites. in.

- 28.Shawakfeh, K. Q., Al-Said, N. H. & Al-Zoubi, R. M. Synthesis of bis-diosgenin pyrazine dimers: new cephalostatin analogs. Steroids73, 579–584 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karulin, B. & Kozhevnikov, M. Ketcher: web-based chemical structure editor. J. Cheminform.3, P3 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sander, T., Freyss, J., Von Korff, M. & Rufener, C. DataWarrior: an open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model.55, 460–473 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bickerton, G. R., Paolini, G. V., Besnard, J., Muresan, S. & Hopkins, A. L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem.4, 90–98 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong, G. et al. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res.49, W5–W14 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyle, N. M. O. et al. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform.3, 1–14 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem.25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson, M. R. et al. The three-dimensional structure of a Plasmodium falciparum Cyclophilin in complex with the potent anti-malarial cyclosporin A1. J. Mol. Biol.298, 123–133 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61, 3891–3898 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.NA-NA10.1002/jcc.21334 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Liu, N. & Xu, Z. Using LeDock as a Docking tool for computational drug design. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci.218, 012143 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alhossary, A., Handoko, S. D., Mu, Y. & Kwoh, C. K. Fast, accurate, and reliable molecular Docking with QuickVina 2. Bioinformatics31, 2214–2216 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem.30, 2785–2791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, H., S Leung, K. & H Wong, M. Idock: A multithreaded virtual screening tool for flexible ligand Docking. 2012 IEEE Symp. Comput. Intell. Comput. Biology CIBCB 2012. 77-8410.1109/CIBCB.2012.6217214 (2012).

- 42.Koes, D. R., Baumgartner, M. P. & Camacho, C. J. Lessons learned in empirical scoring with Smina from the CSAR 2011 benchmarking exercise. J. Chem. Inf. Model.53, 1893–1904 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Debnath, A., Mazumder, R., Singh, A. K. & Singh, R. K. Identification of novel cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors from marine natural products. PLoS One. 20, e0313830 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Debnath, A. et al. Quest for Discovering Novel CDK12 Inhibitor by Leveraging High-Throughput Virtual Screening. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3382004/v1 (2023). 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3382004/v1

- 45.Hunter, J. D. & Matplotlib A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng.9, 90–95 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 46.The pandas development team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. [object Object] (2024). 10.5281/ZENODO.3509134

- 47.Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with numpy. Nature585, 357–362 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Der Spoel, D. et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem.26, 1701–1718 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Debnath, A. et al. Discovery of Novel PTP1B Inhibitors by High-throughput Virtual Screening. CAD 21, (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Debnath, A., Mazumder, R., Singh, R. K. & Singh, A. K. Discovery of novel CDK4/6 inhibitors from fungal secondary metabolites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.282, 136807 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang, J. & Mackerell, A. D. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem.34, 2135–2145 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 14, 71–73 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanommeslaeghe, K. & MacKerell, A. D. Automation of the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF) I: bond perception and atom typing. J. Chem. Inf. Model.52, 3144–3154 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanommeslaeghe, K. et al. CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all‐atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem.31, 671–690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Izadi, S., Anandakrishnan, R. & Onufriev, A. V. Building water models: a different approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.5, 3863–3871 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price, D. J. & Brooks, C. L. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys.121, 10096–10103 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boonstra, S., Onck, P. R. & Van Der Giessen, E. CHARMM TIP3P water model suppresses peptide folding by solvating the unfolded state. J. Phys. Chem. B. 120, 3692–3698 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michaud-Agrawal, N., Denning, E. J., Woolf, T. B. & Beckstein, O. MDAnalysis: a toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem.32, 2319–2327 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cock, P. J. A. et al. Biopython: freely available python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics25, 1422–1423 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rego, N. & Koes, D. 3Dmol.js: molecular visualization with WebGL. Bioinformatics31, 1322–1324 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouysset, C. & Fiorucci, S. ProLIF: a library to encode molecular interactions as fingerprints. J. Cheminform.13, 72 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rose, A. S. et al. NGL viewer: web-based molecular graphics for large complexes. Bioinformatics34, 3755–3758 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.7, 42717 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Banerjee, P., Kemmler, E., Dunkel, M. & Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res.52, W513–W520 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031357

- 66.Wahajuddin, M. et al. Simultaneous quantification of proposed anti-malarial combination comprising of lumefantrine and CDRI 97–78 in rat plasma using the HPLC–ESI-MS/MS method: application to drug interaction study. Malar. J.14, 172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valecha, N. et al. Arterolane maleate plus Piperaquine phosphate for treatment of uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria: a comparative, multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis.55, 663–671 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zech, J. et al. Oral administration of Artemisone for the treatment of schistosomiasis: formulation challenges and in vivo efficacy. Pharmaceutics12, 509 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Haynes, R. K. et al. Artemisone—a highly active antimalarial drug of the Artemisinin class. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.45, 2082–2088 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phyo, A. P. et al. Antimalarial activity of artefenomel (OZ439), a novel synthetic antimalarial endoperoxide, in patients with plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium Vivax malaria: an open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis.16, 61–69 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brit, J. C. Pharma – 2012 - Moehrle - First-in-man Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Synthetic Ozonide OZ439 Demonstrates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Sashidhara, K. V. et al. Coumarin-trioxane hybrids: synthesis and evaluation as a new class of antimalarial scaffolds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.22, 3926–3930 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lill, M. A. Efficient incorporation of protein flexibility and dynamics into molecular docking simulations. Biochemistry50, 6157–6169 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Attram, H. D., Korkor, C. M., Taylor, D., Njoroge, M. & Chibale, K. Antimalarial imidazopyridines incorporating an intramolecular hydrogen bonding motif: medicinal chemistry and mechanistic studies. ACS Infect. Dis.9, 928–942 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhan, W. et al. Dual-pharmacophore artezomibs hijack the plasmodium ubiquitin-proteasome system to kill malaria parasites while overcoming drug resistance. Cell. Chem. Biol. 30, 457–469e11 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mehta, M. et al. Lipid-based nanoparticles for drug/gene delivery: an overview of the production techniques and difficulties encountered in their industrial development. ACS Mater. Au. 3, 600–619 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu, D. et al. The blood–brain barrier: structure, regulation and drug delivery. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 8, 217 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.