Abstract

Facial paralysis is a common neurological disorder that can result from various central or peripheral nervous system diseases, impairing facial expression and significantly affecting the quality of life. Traditional Chinese external therapies, including facial acupuncture and scalp Gua Sha, have shown promise in rehabilitation. However, clinical evaluations of their combined application remain limited. This study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha in treating facial paralysis. This retrospective controlled study analyzed 132 patients with facial paralysis treated at our hospital between January 2023 and January 2025. Patients were assigned to a combined treatment group (facial acupuncture + scalp Gua Sha, n = 68) or a control group (facial acupuncture alone, n = 64). Both groups underwent 4 weeks of treatment. Outcomes included House-Brackmann facial nerve grading, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) syndrome scores, onset time of symptom relief, facial muscle electromyography recovery, adverse events, and patient satisfaction. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0. After 4 weeks, the proportion of patients reaching House-Brackmann grade I–II was higher in the combined group (82.4%) than in the control group (64.1%) (P = .015). TCM syndrome scores decreased significantly in both groups, with a higher effectiveness rate in the combined group (91.2% vs 76.6%, P = .018). The combined group showed faster symptom relief (5.2 ± 1.3 vs 7.6 ± 2.1 days, P < .001) and better electromyography recovery rates (79.4% vs 61.5%, P = .042). No serious adverse events occurred in either group; mild reactions were similar (P = .382). Patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the combined group (4.6 ± 0.5 vs 4.2 ± 0.6, P = .009). Facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha significantly improves facial nerve function and TCM syndromes, accelerates symptom relief, and enhances patient satisfaction. With high safety and patient compliance, this integrative approach offers notable clinical benefits and warrants broader application in facial paralysis rehabilitation.

Keywords: electromyography, facial acupuncture, facial paralysis, patient satisfaction, scalp Gua Sha, traditional Chinese external therapy

1. Introduction

Facial paralysis is a common neurological disorder resulting from dysfunction of the facial nerve, which can be caused by a variety of central or peripheral nervous system diseases. These causes include viral infections, trauma, tumors, or idiopathic conditions, among others. The clinical manifestations of facial paralysis typically involve unilateral facial muscle weakness, mouth deviation, loss of forehead wrinkles, and incomplete eye closure. These symptoms can significantly impact a patient’s daily life, social interactions, and psychological well-being.[1–3] Epidemiological studies indicate an annual incidence of approximately 20 to 30 cases per 100,000 population, with no significant sex difference, but a higher prevalence among young and middle-aged adults, particularly during winter and spring.[4] Etiologically, the condition involves complex mechanisms and may be associated with viral infections (such as herpes simplex virus), cold exposure, impaired local microcirculation, and immune dysfunction. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), facial paralysis is classified under “deviation of the mouth and eyes” or “invasion of pathogenic wind.” The pathogenesis is primarily attributed to wind-cold pathogens invading the meridians, obstructing the flow of Qi and blood, and resulting in malnourishment of the facial muscles.[5,6]

Currently, the mainstream treatment of facial paralysis in Western medicine includes corticosteroids, antiviral medications, and physical rehabilitation. However, these therapies are often limited by delayed onset of efficacy, potential adverse effects, and inconsistent clinical outcomes.[7,8] As a traditional therapeutic modality in Chinese medicine, acupuncture has been widely used in the rehabilitation of facial paralysis due to its proven efficacy, minimal side effects, and ease of application.[9] Facial acupuncture, an important branch of acupuncture, emphasizes localized needling at specific facial points such as Yangbai, Sibai, Dicang, Jiache, and Yifeng. This technique aims to regulate local Qi and blood circulation, dredge meridians, and promote facial nerve function recovery.[10] Numerous studies have confirmed that facial acupuncture can effectively improve facial muscle mobility, relieve numbness, and enhance nerve conduction. Nevertheless, the limitations of monotherapy—such as slower onset, difficulty in maintaining efficacy, and variable patient compliance—have prompted the clinical need to explore integrative treatment approaches with synergistic effects.[11–13]

Gua Sha, another key external therapy in TCM, is known for its effects in “activating meridians and collaterals, removing stasis and alleviating pain, and expelling external pathogens.” It is commonly applied to treat syndromes such as wind-cold-damp obstruction, muscle pain, and early-stage febrile diseases.[14] Modern research suggests that Gua Sha exerts mechanical stimulation on cutaneous receptors, thereby activating neuro-immune-endocrine regulatory pathways, enhancing regional blood perfusion, and promoting local tissue metabolism.[14,15] Additionally, it facilitates the release of signaling molecules such as nitric oxide, ultimately improving tissue oxygenation. Scalp Gua Sha, a specialized technique within Gua Sha therapy, targets the scalp, temples, forehead, and occipital region, potentially providing more direct modulation of facial neurovascular structures and improving meridian flow and facial muscle tension regulation.[15] However, existing studies on acupuncture combined with Gua Sha in facial paralysis remain scarce, predominantly limited to small-sample clinical observations, lacking comprehensive efficacy assessments and multidimensional mechanistic evaluations.

This study proposes a combined intervention strategy of facial acupuncture and scalp Gua Sha, grounded in the TCM principle of “treating both the symptoms and root causes.” The approach integrates localized acupoint activation with scalp meridian regulation to establish a synergistic external therapy model. Facial acupuncture directly stimulates neuromuscular tissues to facilitate nerve repair, while scalp Gua Sha enhances regional blood flow and skin temperature, fostering a microenvironment conducive to neural regeneration and establishing systemic-local therapeutic synergy. To comprehensively evaluate clinical efficacy, this study adopts both subjective indicators (House-Brackmann grading, TCM syndrome scoring, and patient satisfaction) and objective outcomes (electromyography, onset time, and adverse events), aiming for a multidimensional assessment of functional recovery, safety, and patient compliance. Compared to previous studies focused on single endpoints or short-term efficacy, our study design offers greater methodological rigor and practical applicability, with distinct innovation and clinical value.

Given the growing use of acupuncture combined with external therapies in rehabilitation medicine, high-quality evidence remains insufficient, particularly for specific conditions such as facial paralysis. Key clinical aspects including onset time, electrophysiological recovery, and patient experience require further investigation. Therefore, this retrospective controlled study enrolled patients with facial paralysis treated at our hospital from January 2023 to January 2025, to compare the efficacy and safety of facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha versus facial acupuncture alone. The goal is to provide evidence-based support for optimizing integrative traditional Chinese therapeutic approaches in the treatment of facial paralysis.

2. Method

2.1. Study design and participants

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. This was a single-center, retrospective controlled study conducted at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of our hospital. Patients diagnosed with facial paralysis who received either outpatient or inpatient treatment between January 2023 and January 2025 were included. All participants met the diagnostic criteria for “facial paralysis” as outlined in the standards for diagnosis and therapeutic effect of diseases and syndromes in TCM, and central facial paralysis was excluded by cranial MRI.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) age between 18 and 70 years; (2) first episode or disease duration ≤ 1 month; and (3) no prior systematic acupuncture or physical therapy. Exclusion criteria included: (1) pregnancy or lactation; (2) comorbid severe heart, brain, liver, or kidney diseases; (3) mental disorders or poor treatment compliance; and (4) skin infections or local ulcerations not suitable for Gua Sha treatment.

2.2. Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated based on a two-tailed t test, using satisfaction score as the primary effect indicator. It was assumed that the mean satisfaction score would be 4.6 ± 0.5 in the combined treatment group and 4.2 ± 0.6 in the control group, with α = 0.05 and power (1 ‐ β) = 0.90. Using G*Power software, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 58 patients per group. Considering a 10% potential dropout or incomplete data, at least 64 patients were planned to be included in each group.

2.3. Grouping and interventions

Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the treatment modality. The control group received routine facial acupuncture, targeting standard acupoints such as Yangbai, Sibai, Dicang, Jiache, and Yifeng. Treatment was administered once daily for 30 minutes over 4 consecutive weeks.

The combined treatment group received facial acupuncture as above, along with scalp Gua Sha. Gua Sha was performed using a buffalo horn scraping board applied to the top of the head, forehead, temples, and occipital region. Each session lasted 10 minutes and was conducted 3 times per week for 4 weeks. The frequency and duration of treatment were kept consistent across both groups.

2.4. Outcome measures and evaluation

The primary outcome was facial nerve function assessed using the House-Brackmann (HB) grading scale, evaluated before treatment and on day 28 of treatment. TCM syndrome scoring was based on the relevant section in the clinical guidelines of Traditional Chinese Medicine, using a 0 to 3 point scale. Two experienced physicians independently rated the symptoms, and the mean score was used for analysis. The onset time was defined as the number of days from the initiation of treatment to the first subjective report of symptom improvement, confirmed jointly by the patient and physician.

Secondary outcomes included: (1) facial muscle electromyography (EMG) recovery, assessed using a keypoint. EMG device to evaluate normalization of EMG activity patterns; (2) treatment-related adverse events, such as contact dermatitis, itching, or dizziness; and (3) patient satisfaction, measured using a 5-point likert scale questionnaire completed independently at the end of treatment.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation x±s and compared using independent samples t tests. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and group comparisons were conducted using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Missing data, which accounted for <5% of the total data, were handled using multiple imputation. To account for potential confounding factors, such as baseline differences in symptom severity, we conducted multivariate regression analysis to adjust for these variables and ensure more accurate assessment of treatment effects. A P-value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 132 patients with facial paralysis were included in this study, with 68 cases in the combined treatment group and 64 cases in the control group. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of general demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, age, disease duration, affected side, and initial HB grading (all P > .05).

Similarly, no significant differences were observed in physical parameters (height, weight, and BMI) or vital signs (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate) between the 2 groups (all P > .05). In addition, the proportions of patients with hyperglycemia and smoking history did not differ significantly between groups (P = .698 and P = .731, respectively). Overall, baseline variables were well balanced, indicating good comparability between groups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the 2 groups.

| Variable | Combined treatment group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 64) | Statistic (χ2/t) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 34/34 | 31/33 | χ2 = 0.026 | .875 |

| Age (yr) | 45.7 ± 12.3 | 47.1 ± 11.5 | t = 0.79 | .429 |

| Disease duration (d) | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 7.0 ± 2.4 | t = 0.58 | .561 |

| Affected side (left/right) | 36/32 | 34/30 | χ2 = 0.045 | .774 |

| Initial HB grade (III/IV/V) | 21/29/18 | 19/27/18 | χ2 = 0.057 | .973 |

| Height (cm) | 165.3 ± 7.6 | 164.6 ± 8.1 | t = 0.52 | .602 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.8 ± 10.2 | 66.2 ± 9.5 | t = 0.84 | .402 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | t = 1.15 | .253 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 129.5 ± 12.4 | 131.0 ± 11.9 | t = 0.68 | .497 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 78.3 ± 9.2 | 77.6 ± 8.5 | t = 0.42 | .676 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 76.2 ± 6.7 | 77.0 ± 7.1 | t = 0.62 | .536 |

| Hyperglycemia (yes/no) | 12/56 | 14/50 | χ2 = 0.151 | .698 |

| Smoking history (yes/no) | 18/50 | 20/44 | χ2 = 0.118 | .731 |

HB = House-Brackmann.

3.2. Comparison of facial nerve function improvement

After 4 weeks of treatment, facial nerve function was evaluated in both groups using the HB grading scale. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, 28 patients in the combined treatment group achieved grade I recovery and 28 achieved grade II, totaling 56 patients (82.4%) with HB grades I–II. In the control group, 20 patients achieved grade I and 21 achieved grade II, totaling 41 patients (64.1%) with HB grades I–II. The difference in favorable outcome rate (HB grades I–II) between the 2 groups was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.89, P = .015).

Figure 1.

Distribution of HB grades after 4 weeks of treatment. HB = House-Brackmann.

Table 2.

Comparison of HB grade distribution after 4 weeks of treatment.

| HB grade | Combined group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 64) |

|---|---|---|

| I | 28 | 20 |

| II | 28 | 21 |

| III | 8 | 14 |

| IV | 3 | 6 |

| V | 1 | 3 |

| I + II (excellent) | 56 (82.4%) | 41 (64.1%) |

| χ 2 | 5.89 | |

| P-value | .015 |

HB = House-Brackmann.

Further analysis of the HB grade distribution revealed that the proportion of patients with HB grades below III was significantly higher in the combined treatment group, whereas the control group had a relatively higher proportion of patients with grades III and above. These findings suggest that the combined therapy was more effective in promoting recovery of facial nerve function.

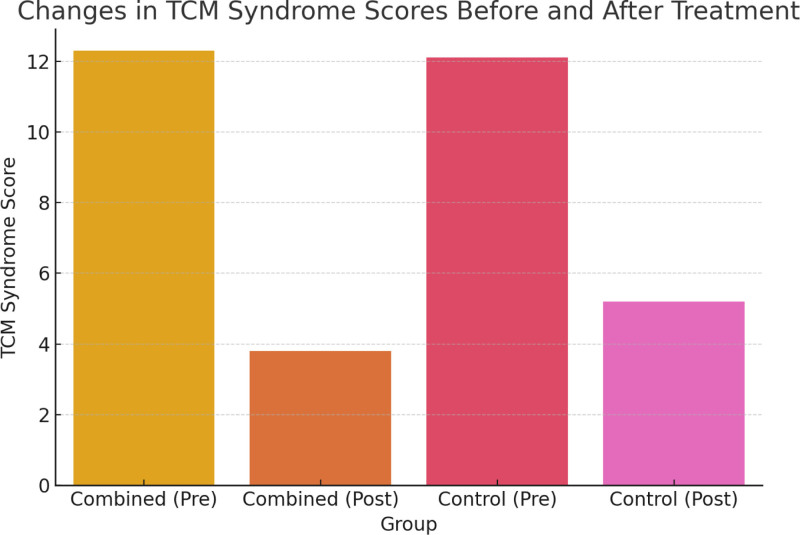

3.3. Changes in TCM syndrome scores

Before treatment, the TCM syndrome scores were comparable between the 2 groups: 12.3 ± 2.4 in the combined treatment group and 12.1 ± 2.7 in the control group, with no statistically significant difference (P > .05). After 4 weeks of treatment, both groups showed significant reductions in TCM syndrome scores. However, the reduction in the combined group was more pronounced, with posttreatment scores of 3.8 ± 1.9 and 5.2 ± 2.1 in the combined and control groups, respectively (t = 3.12, P < .01).

When therapeutic efficacy was categorized based on the degree of TCM symptom improvement, the total effective rate in the combined treatment group was 91.2%, significantly higher than 76.6% in the control group (χ2 = 5.62, P = .018), as shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. These findings indicate that facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha is more effective in improving TCM-related clinical syndromes.

Figure 2.

Changes in TCM syndrome scores before and after treatment. TCM = Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Table 3.

Comparison of TCM syndrome scores and overall efficacy.

| Variable | Combined treatment group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 64) |

|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment score (points) | 12.3 ± 2.4 | 12.1 ± 2.7 |

| Posttreatment score (points) | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 5.2 ± 2.1 |

| Score reduction | 8.5 ± 2.0 | 6.9 ± 2.3 |

| Total effective rate | 91.20% | 76.60% |

| t/χ2 value | t = 3.12 | χ2 = 5.62 |

| P-value | <.01 | .018 |

TCM = Traditional Chinese Medicine.

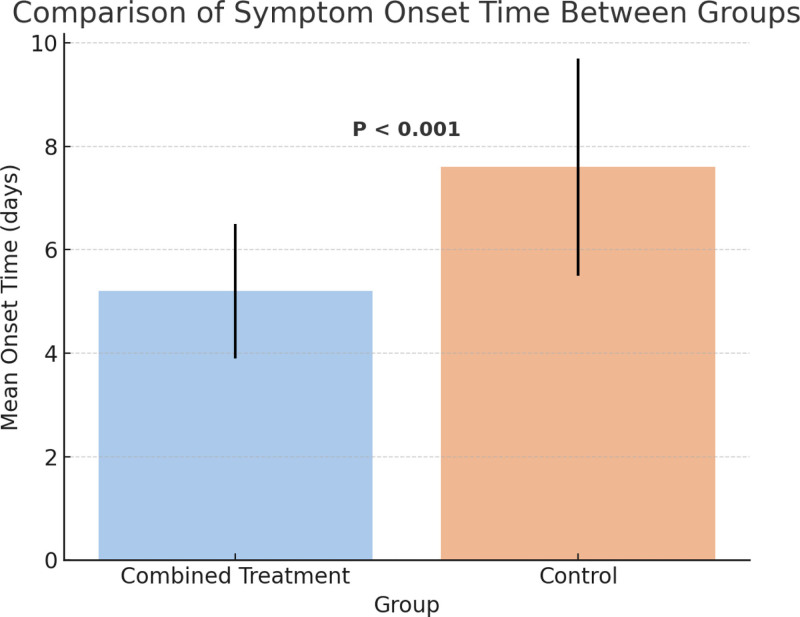

3.4. Comparison of time to symptom onset

The comparison of treatment onset time revealed that the combined treatment group had a significantly shorter mean onset time (5.2 ± 1.3 days) compared to the control group (7.6 ± 2.1 days), with a statistically significant difference (t = 6.18, P < .001).

These results suggest that facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha results in faster symptom relief and an early therapeutic advantage in patients with facial paralysis. As shown in Figure 3, the combined group exhibited a more favorable trend in early symptom improvement, offering support for optimizing early-stage intervention strategies.

Figure 3.

Comparison of symptom onset time between groups.

3.5. Recovery of facial muscle EMG

Among patients who underwent facial muscle EMG evaluation, 54 cases in the combined treatment group showed normalized EMG patterns, with a recovery rate of 79.4%, while 40 cases in the control group recovered, with a rate of 61.5%. The difference in recovery rates between the 2 groups was statistically significant (χ2 = 4.13, P = .042), suggesting a greater advantage of the combined treatment in promoting neurophysiological recovery.

As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4, the EMG recovery rate was significantly higher in the combined treatment group, further supporting its clinical value in improving facial nerve conduction function.

Figure 4.

EMG recovery rate of facial muscles. EMG = electromyography.

Table 4.

Comparison of facial muscle EMG recovery between the 2 groups.

| Variable | Combined treatment group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 65) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of recovered | 54 | 40 |

| Number of not recovered | 14 | 25 |

| Total number | 68 | 65 |

| Recovery rate | 79.40% | 61.50% |

| χ2 value | χ2 = 4.13 | |

| P-value | .042 |

EMG = electromyography.

3.6. Adverse events and patient satisfaction

No serious adverse events occurred in either group during the treatment period, as detailed in Table 5. Mild adverse reactions such as localized erythema and itching were reported in 6 patients (8.8%) in the combined treatment group and in 3 patients (4.7%) in the control group. The difference in adverse event rates between groups was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.76, P = .382), indicating that both treatment approaches were well tolerated and safe.

Table 5.

Comparison of adverse events and patient satisfaction between the 2 groups.

| Variable | Combined treatment group (n = 68) | Control group (n = 64) |

|---|---|---|

| Mild adverse events (n) | 6 | 3 |

| Incidence of adverse events (%) | 8.80% | 4.70% |

| Satisfaction score (mean ± SD) | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.6 |

| t/χ2 value | t = 2.65 | χ2 = 0.76 |

| P-value | .009 | .382 |

In terms of patient satisfaction, the combined treatment group reported significantly higher scores (4.6 ± 0.5) compared to the control group (4.2 ± 0.6), with a statistically significant difference (t = 2.65, P = .009). These findings suggest that facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha is more readily accepted by patients, promotes better compliance, and holds promising clinical applicability.

4. Discussion

Facial paralysis, also referred to as facial neuritis or Bell palsy, is a common cranial nerve disorder characterized primarily by impaired function of the facial expression muscles.[16] Although its exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it is widely believed to be associated with viral infections, autoimmune responses, and disturbances in local microcirculation.[17,18] Conventional treatments mainly include pharmacotherapy, physical therapy, and acupuncture, but their effectiveness varies significantly among individuals. These approaches are often limited by slow onset and prolonged recovery periods. In recent years, as traditional Chinese external therapies have evolved, integrated approaches combining multiple traditional modalities have received growing attention. This study investigated the clinical effects of facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha in patients with facial paralysis. The results showed that this combined therapy was superior to facial acupuncture alone in improving facial nerve function, alleviating TCM syndromes, shortening onset time, enhancing EMG recovery rate, and improving patient satisfaction, while maintaining a favorable safety profile.[19–21]

Rigorous inclusion criteria were applied to ensure baseline comparability between the 2 groups, including age, sex, disease duration, initial HB grade, vital signs, and BMI. This ensured the internal validity of the results and provided a robust foundation for subsequent outcome comparisons.

Facial nerve function recovery is a key indicator for assessing therapeutic efficacy. After 4 weeks of treatment, the combined therapy group achieved an 82.4% recovery rate in HB grades I–II, significantly higher than the 64.1% observed in the control group. This suggests that the combined intervention more effectively promotes facial nerve functional restoration. Previous studies have reported that traditional acupuncture improves symptoms of facial paralysis by increasing local blood flow, reducing muscle spasms, and enhancing neural regeneration.[22] In our study, the addition of scalp Gua Sha to standard facial acupuncture may have further enhanced local circulation and immune modulation through the stimulation of cranial meridians, thus accelerating the nerve repair process.

In terms of TCM syndrome scores, both groups showed significant reductions posttreatment, but the combined group exhibited a more pronounced decrease, with a total effectiveness rate of 91.2% compared to 76.6% in the control group. This indicates the superior efficacy of the integrated therapy in alleviating TCM syndromes such as wind-cold obstruction and Qi-blood stasis. Gua Sha is traditionally believed to possess effects such as “clearing heat,” “unblocking channels,” and “activating blood circulation.” When used alongside acupoint stimulation via facial acupuncture, a synergistic effect likely occurs, achieving both localized and systemic regulation.

Another noteworthy finding is the significant difference in the onset time of symptom relief between groups. The average onset time in the combined group was 5.2 days, significantly shorter than the 7.6 days observed in the control group. Early symptom relief plays a crucial role in patient confidence and compliance. Rapid improvement not only alleviates psychological distress but also allows clinicians to assess and adjust treatment strategies more promptly. Our results align with previous studies, such as those involving fire needling combined with moxibustion, which also demonstrated shorter symptom onset times in patients receiving combined therapies.[23]

From a neurophysiological perspective, the facial muscle EMG recovery rate in the combined group reached 79.4%, notably higher than the 61.5% observed in the control group. This suggests that the combined treatment more effectively promotes facial nerve conduction and regeneration. The enhanced recovery may be attributed to improved regional blood perfusion and a more favorable neuroregenerative microenvironment induced by Gua Sha. It may also involve the activation of neuro-immune signaling pathways. Previous studies have shown that acupuncture can upregulate the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, supporting the hypothesis that traditional Chinese external therapies may facilitate nerve regeneration through molecular signaling cascades.[24]

Although the incidence of mild adverse events such as localized erythema or itching was slightly higher in the combined group (8.8%) than in the control group (4.7%), no serious adverse reactions were observed in either group. This indicates good clinical tolerability, which is consistent with previous studies that have reported minimal side effects with acupuncture and Gua Sha treatments in similar settings. Importantly, patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the combined group (4.6 ± 0.5) compared to the control group (4.2 ± 0.6), highlighting better patient acceptance and adherence. These findings further support the clinical value and feasibility of integrating scalp Gua Sha with facial acupuncture. As seen in previous studies examining acupuncture and Gua Sha separately, the combined approach has the potential to enhance therapeutic outcomes.[22]

From an innovation standpoint, this study is the first to systematically evaluate the combination of facial acupuncture and scalp Gua Sha in the treatment of facial paralysis. A multidimensional evaluation system was constructed, integrating both subjective measures (HB grading, TCM syndrome scores, and satisfaction scales) and objective physiological indicators (EMG, onset time, and adverse events). Unlike previous studies that focused on a single intervention or outcome, our design offers a more comprehensive and realistic assessment of therapeutic efficacy, with added methodological value. Moreover, we included onset time as a key outcome, which is a highly relevant indicator from the patient’s perspective and extends the evaluation of treatment effectiveness into the temporal dimension.[23]

However, this study has several limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective analysis, the findings require confirmation through future multicenter randomized controlled trials. Second, subgroup analysis based on syndrome differentiation or disease stage was not performed, limiting the exploration of individualized intervention strategies. Third, EMG assessments were only available for a subset of patients, which may have reduced statistical power. Additionally, the study did not address long-term outcomes or recurrence rates, which are important factors in assessing the lasting effectiveness of the combined treatment. Future studies should consider evaluating long-term outcomes and recurrence to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the treatment’s sustained effects. Finally, future research may benefit from incorporating multimodal imaging and neurochemical biomarkers to further elucidate the mechanisms of action.

In summary, facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha demonstrates promising comprehensive efficacy in the treatment of facial paralysis. This integrative approach not only significantly improves facial nerve function and TCM syndromes, but also accelerates clinical onset, enhances EMG recovery, and achieves high patient satisfaction with good safety. The combined therapy offers a feasible and effective strategy for integrating traditional Chinese external therapies into modern rehabilitation medicine and provides a new direction for optimizing the treatment of facial paralysis.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha offers significant clinical advantages in the treatment of facial paralysis. The combined therapy effectively promotes facial nerve function recovery, improves TCM syndrome scores, shortens the time to symptom onset, enhances electromyographic recovery of facial muscles, and exhibits good safety and patient satisfaction. These findings suggest that the integration of scalp Gua Sha with traditional facial acupuncture produces synergistic benefits and may provide a more efficient, convenient, and generalizable therapeutic strategy for clinical intervention in facial paralysis. Although this study was retrospective in nature, it lays the groundwork for future prospective, multicenter clinical trials. Overall, the facial acupuncture plus Gua Sha treatment model shows strong clinical applicability and warrants further exploration and optimization in both rehabilitation settings and primary care practices.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xuan Wang.

Data curation: Yihan Yu, Xuan Wang.

Formal analysis: Yihan Yu, Xuan Wang.

Investigation: Yihan Yu.

Methodology: Yihan Yu.

Writing – original draft: Yihan Yu, Xuan Wang.

Writing – review & editing: Yihan Yu, Xuan Wang.

Abbreviations:

- EMG

- electromyography

- HB

- House-Brackmann

- TCM

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Wang X, Yu Y. Observation on the therapeutic effect of facial acupuncture combined with scalp Gua Sha in the treatment of facial paralysis. Medicine 2025;104:33(e43546).

References

- [1].Molinari G, Lucidi D, Fernandez IJ, et al. Acquired bilateral facial palsy: a systematic review on aetiologies and management. J Neurol. 2023;270:5303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tollefson TT, Hadlock TA, Lighthall JG. Facial paralysis discussion and debate. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018;26:163–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moncaliano MC, Ding P, Goshe JM, Genther DJ, Ciolek PJ, Byrne PJ. Clinical features, evaluation, and management of ophthalmic complications of facial paralysis: a review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;87:361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Terzis JK, Anesti K. Developmental facial paralysis: a review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1318–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hohman MH, Hadlock TA. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of facial palsy: 2000 patients at a facial nerve center. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:E283–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mandava S, Gutierrez CN, Oyer SL. Persistent facial paralysis diagnosed as “bell’s palsy”. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2024;26:98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Owusu JA, Stewart CM, Boahene K. Facial nerve paralysis. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:1135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pereira LM, Obara K, Dias JM, Menacho MO, Lavado EL, Cardoso JR. Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:649–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pou JD, Patel KG, Oyer SL. Treating nasal valve collapse in facial paralysis: what I do differently. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2021;29:439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ishii LE. Facial nerve rehabilitation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24:573–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morley SE. Are dynamic procedures superior to static in treating the paralytic eyelid in facial paralysis?. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;77:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cao Z, Jiao L, Wang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of cupping therapy for treating of intractable peripheral facial paralysis: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim). 2021;100:e25388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].O TM. Medical management of acute facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:1051–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nielsen A, Knoblauch NT, Dobos GJ, Michalsen A, Kaptchuk TJ. The effect of Gua Sha treatment on the microcirculation of surface tissue: a pilot study in healthy subjects. Explore (NY). 2007;3:456–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen T, Liu N, Liu J, et al. Gua Sha, a press-stroke treatment of the skin, boosts the immune response to intradermal vaccination. Peer J. 2016;4:e2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gaudin RA, Jowett N, Banks CA, Knox CJ, Hadlock TA. Bilateral facial paralysis: a 13-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mehdizadeh OB, Diels J, White WM. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang X, Jiang F, Zhou T, Gu Q, Li X. Effectiveness of low-frequency pulse electrical stimulation combined with dexamethasone in treating facial nerve paralysis and its impact on facial nerve function and electromyography. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024;30:530–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Su D, Li D, Wang S, et al. Hypoglossal-facial nerve “side-to-side” neurorrhaphy for facial paralysis resulting from closed temporal bone fractures. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2018;36:443–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Varelas EA, Gidumal S, Verma H, Vujovic D, Rosenberg JD, Gray M. Physical therapy for idiopathic facial paralysis: a systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2025;46:104511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stefaniak AA, Knecht K, Matusiak L, Szepietowski JC. Sudden onset of unilateral facial paralysis with ear pruritus: a quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00675. Published March 22, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang N, Bogart K, Michael J, McEllin L. Web-based sensitivity training for interacting with facial paralysis. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0261157. Published January 21, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Langhals NB, Urbanchek MG, Ray A, Brenner MJ. Update in facial nerve paralysis: tissue engineering and new technologies. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22:291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang L, Wang Z, Wan C, Cai X, Zhang G, Lai C. Facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of infant leukemia: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltim). 2018;97:e13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]