Abstract

Gem‐diols are defined as organic molecules carrying two hydroxyl groups at the same carbon atom, which is the result of the nucleophilic addition of water to a carbonyl group. In this work, the generation of the hydrated or hemiacetal forms using pyridine‐ and imidazole‐carboxaldehyde isomers in different chemical environments was studied by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) recorded in different media and combined with theoretical calculations. The change in the position of aldehyde group in either the pyridine or the imidazole ring had a clear effect in the course of the hydration/hemiacetal generation reaction, which was favored in protic solvents mainly in the presence of methanol. For pyridinecarboxaldehydes, the acidity/basicity degree of the reaction medium influenced not only the generation of the gem‐diol or hemiacetal forms but also the oxidation to the corresponding carboxylic acid. However, imidazolecarboxaldehyde was found to be less reactive to the nucleophilic addition of water and methanol than the other compounds in all the environments evaluated. Furthermore, both the gem‐diol/hemiacetal generation and the Cannizzaro reaction products were studied in alkaline medium.

Keywords: Pyridinecarboxaldehydes, Imidazolecarboxaldehydes, NMR, Gem-diol, Theoretical calculations

The generation of the gem‐diol and hemiacetal forms using pyridine‐ and imidazole‐carboxaldehyde isomers in different chemical environments was studied by NMR spectra and combined with theoretical calculations. Unlike aprotic solvents, protic ones, as water and methanol, favored the generation of the gem‐diol and hemiacetal structures.

Introduction

Nucleophilic addition reactions to carbonyl groups (of ketones and aldehydes) [1] have been intensively studied because of their importance in the obtention of a wide variety of products such as gem‐diols (or geminal diols), alcohols, hemiacetals, imines, semicarbazones and α‐hydroxysilanes.[ 2 , 3 , 4 ] These compounds are key building blocks in the synthesis of pharmaceutical drugs, biologically active molecules, metal complexes and supramolecular structures.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Particularly, gem‐diols and hemiacetals, which are obtained by the nucleophilic addition of water and alcohol molecules to a carbonyl group, respectively, are unstable and difficult to isolate because they easily revert to the original carbonyl compound.[ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] In general, they are found as intermediates in key chemical reactions, such as those taking place at the active site of an enzyme[ 20 , 21 ] or in the obtention of a product of interest such as the critical gem‐diol intermediate for anodic hydrogen production using 5‐hydroxymethylfurfural. [22]

As benzaldehydes, pyridine‐ and imidazole‐carboxaldehydes undergo addition reactions with a wide variety of nucleophiles. These compounds and their derivatives have aroused great interest due to their many applications in organic synthesis, coordination chemistry, polymeric chemistry, and catalysis; due to the reactivity of both the carbonyl group and the nitrogen heteroatom.[ 17 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] For heterocyclic compounds, the electronic structure of the ring significantly influences the reactivity of the carbonyl group present at different positions. In pyridines, positions 2, 4, and 6 exhibit lower electron density due to the electron‐withdrawing effect of the nitrogen atom. In imidazoles, this effect is predominantly observed at position 2, which is between a pyridine‐ and a pyrrolic‐like nitrogens. In a previous work, the susceptibility of pyridinecarboxaldehydes to the nucleophilic addition of water and water‐trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was analyzed in solution and solid‐state NMR, and single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction techniques. The hydration studies indicated that the position of the carbonyl group was crucial to stabilize the gem‐diol form, therefore allowing its isolation. The hydration of pyridinecarboxaldehyde compounds was favored by the electron‐withdrawing character of the aromatic system at positions 2 and 4, where the gem‐diol moiety was particularly stable. [27] In particular, the gem‐diol form could be isolated as a trifluoroacetate derivative in those positions. However, 3‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde only rendered the carbonyl form in the solid state even as a trifluoroacetate. Particularly, the neutral solid gem‐diol form for the 4‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde could be directly isolated by reaction with water, during which the gem‐diol precipitates. Moreover, the isomers substituted with electron withdrawing groups increased the hydration degree when compared to those with electron donor substituents. As for imidazolecarboxaldehyde, the same analyses demonstrated a major reactivity at the position 2 in comparison with position 4.[ 28 , 29 ] Scheme 1 shows some of the gem‐diol and bis‐hemiacetal forms generated from 2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde,[ 28 , 29 ] N‐methyl‐2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde, [28] pyridinecarboxaldehyde and the pyridoxal molecules.[ 27 , 30 ] Furthermore, the chemical conversion of the carbonyl group in 4‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde or N‐methylimidazole‐2‐carboxaldehyde ligands in copper(II) complexes to the corresponding ortho ester and hemiacetal moieties [24] or gem‐diol forms, [25] respectively were demonstrated in the crystalline state.

Scheme 1.

Neutral (A) and the trifluoroacetate derivatives for the gem‐diol (B) and the bis‐hemiacetal forms (C) of 2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde. Trifluoroacetate derivatives of the gem‐diol (D) and the bis‐hemiacetal forms (E) of the N‐methyl‐2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde. Trifluoroacetate derivatives of the gem‐diol (F), carboxylic acid (G) and aldehyde forms (H) for the 2‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde. Neutral gem‐diol (I) and trifluoroacetate derivatives of the gem‐diol form (J) of the 4‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde. Cyclic hemiacetal form (K) of the pyridoxal hydrochloride.

This work analyzes the influence of the chemical environment, mainly as regards the type of solvent (protic or aprotic) and the medium acidity, in the nucleophilic addition of water or methanol molecules to pyridinecarboxaldehyde and imidazolecarboxaldehyde isomers. The study aims to study the susceptibility for the generation of the gem‐diol or hemiacetal forms of the 4‐, 3‐, and 2‐pyridinecarboxaldehydes; 4‐, 2‐imidazolecarboxaldehydes, and N‐methyl‐2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde using NMR and theoretical calculations.

Results and Discussion

Gem‐Diol and Hemiacetal Generation in Pyridinecarboxaldehydes

The three pyridine isomers, 2‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde (A2 ), 3‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde (A3 ) and 4‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde (A4 ) were compared for the hydrate formation in D2O and DMSO‐d 6, and in presence of TFA in a relation of 99 : 1 (solvent: TFA). The equilibrium of the gem‐diol and carbonyl form in solution was studied directly by NMR. Also, the hemiacetal formation was conducted in CD3OD under different conditions. Particularly, the integration of each 1H‐NMR signal for the gem‐diol/hemiacetal (δ1H=5.0–6.50 ppm) and/or the aldehyde groups (δ1H=9.10–10.50 ppm) allowed obtaining the relative content in terms of each functional moiety in the different media. Besides, the carboxylic acid and/or hemiacetal forms can be identified from the unequivocal assignment of the NMR signals using 2D‐HSQC and 2D‐HMBC experiments as described.[ 27 , 30 ] Noteworthy, these hydration studies for the gem‐diol generation in the different carbonyl compounds were done using D2O or the remaining water content present in the DMSO‐d 6 NMR solvent. The observed δ1H was dependent on the position of the aldehyde group in the pyridine ring (Supporting Information).

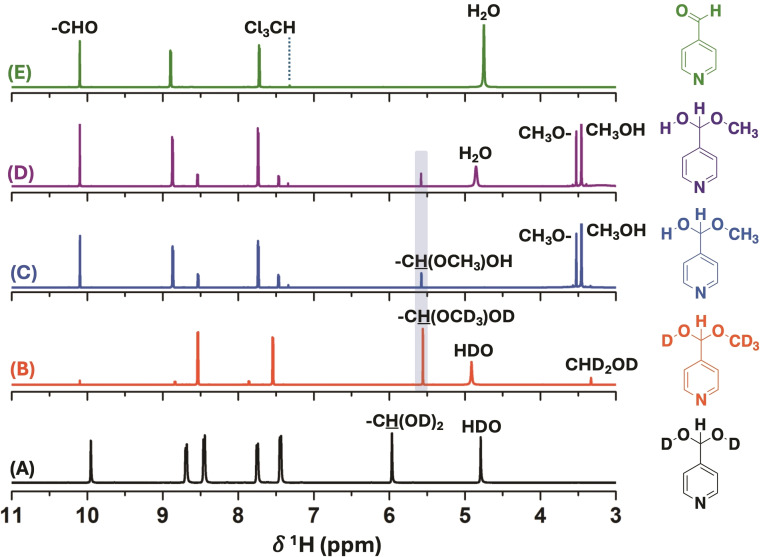

The gem‐diol was only observed in D2O solution in equilibrium with the aldehyde form (Figure 1A and Table 1). The addition of water to the aldehyde group was not observed in the 1H‐NMR experiments in CD3OD due to the low amount of water present in the 4‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde reagent (∼10 mg H2O per 500 μL of aldehyde), and the higher nucleophilicity of methanol in comparison with water (Figure 1B). [31] Special attention must be paid to the correct assignment of the gem‐diol against the hemiacetal form. Potential misassignments may occur due to the use of perdeuterated methanol as a solvent, which hinders the detection of the ‐OCHD2 group in both 1H‐ and 13C‐NMR spectra. Also, different NMR experiments were conducted for A4 to evidence the formation of the hemiacetal derivative with methanol in CDCl3 (Figure 1). The 1H‐NMR spectrum of A4 in CDCl3 with the addition of water (4 %) did not show the gem‐diol generation (Figure 1E), however, the hemiacetal compound was confirmed after the addition of methanol (4 %) in CDCl3 (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the addition of water to this last NMR experiment did not affect the hemiacetal content (30 %) nor showed the evidence of gem‐diol generation (Figure 1D). Remarkably, the hemiacetal content of A4 in CD3OD and TFA:CD3OD was 95 % (with 5 % of aldehyde form) and 97 % (with 3 % of carboxylic acid form), respectively, showing the higher reactivity of the aldehyde group in methanol than in water (Figure 1, S5 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

1H‐NMR spectra for A4 in the presence of D2O (A), CD3OD (B), CDCl3 (with 20 μL of CH3OH) (C), CDCl3 (with 20 μL of CH3OH and 20 μL of H2O) (D) and CDCl3 (with 20 μL of H2O) (E). The final volume in all the NMR tubes was 500 μL.

Table 1.

Relative percentages of gem‐diol (GD), aldehyde (AL), hemiacetal (HA) and carboxylic acid (CA) forms of each pyridinecarboxaldehyde compound obtained from the 1H‐NMR spectra under different experimental conditions.

|

1H‐NMR | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

||||||||||

|

Experimental condition |

GD |

AL |

HA |

CA |

GD |

AL |

HA |

CA |

GD |

AL |

HA |

CA |

|

D2O |

30 |

61 |

– |

9 |

10 |

90 |

– |

– |

48 |

52 |

– |

– |

|

D2O/TFA |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

85 |

15 |

– |

– |

99 |

1 |

– |

– |

|

CD3OD |

– |

19 |

68 |

13 |

– |

27[a] |

72[a] |

– |

– |

5 |

95 |

– |

|

CD3OD/TFA |

– |

2[b] |

85[b] |

13[b] |

– |

31 |

68 |

1 |

– |

3 |

97 |

– |

|

DMSO‐d 6 |

nd [b] |

– |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

100 |

– |

– |

|||

|

DMSO‐d 6/TFA |

nd [b] |

3 |

97 |

– |

– |

1 |

99 |

– |

– |

|||

[a] 1 % acetal. [b] Particularly, it is very difficult to analyze this sample due to its decomposition and/or chemical reactions with TFA. [30]

Table 1 shows a comparison between the hydrate/hemiacetal formation and the remaining carbonyl form for each compound. It is expected that the carbonyl group at position 3 will be less activated for the nucleophilic addition, as compared to positions 2 and 4. For the pyridinecarboxaldehyde isomers, the 1H‐NMR spectra obtained under neutral conditions showed the presence of the gem‐diol form only in D2O and the hemiacetal in CD3OD, while in DMSO‐d6 the isomers were only in the carbonyl form. Particularly, the percentage of hemiacetal generation in CD3OD was much higher when compared to that obtained for the gem‐diol in water (Table 1). The difference was particularly notable in the case of compound A3 , considering that positions 2 and 4 of the pyridine ring are electro‐deficient, as compared to position 3 due to the electron‐withdrawing effect of the nitrogen atom.

A2 and A4 compounds led to the formation of gem‐diol in D2O, but in CD3OD an increase in the formation of pyridinecarboxylic acid was detected for A2 . This denotes the high reactivity of this position since the hemiacetal form usually undergoes oxidization to the acid form. [32] Different single‐crystals were isolated for 2‐pyridinecarboxylic acid when 2‐pyridinecarboxaldehyde molecules were incubated in acidic solutions (TFA or HCl solutions) for the isolation of the gem‐diol forms, as reported previously. [30] However, it is worth mentioning that the bulk solid materials based on both crystalline and amorphous forms were analyzed by NMR in D2O. In this experiment, a mixture of the gem‐diol, the hemiacetal, and the carboxylic acid molecules was detected. Notably, the incubation of the trifluoroacetate of A3 in the presence of ethanol, allowed obtaining the carboxylic acid form of A3 (CA3 ) in the solid state, which was suitable for its study by single‐crystal X‐ray crystallography (CCDC 236209 [33] and Figures S65–S66). The results of the crystallographic study showed the evolution of the aldehyde group to the carboxylic acid moiety, which was indicative of the low stability of the generated hemiacetal form, as the trifluoroacetate derivative which evolved to the corresponding carboxylic acid forms in ethanol. This single‐crystal structure has previously been reported, but in that case, the trifluoroacetate derivative has been synthesized from the corresponding nicotinic acid and TFA (1 : 1). [34]

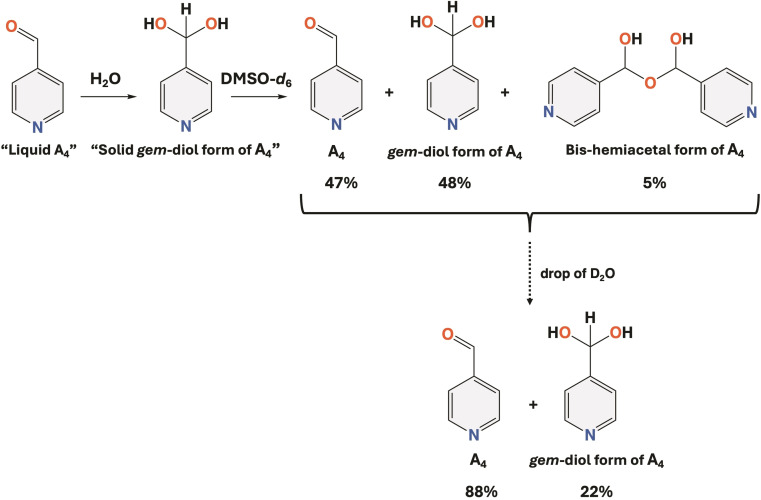

Furthermore, the solid sample of the neutral gem‐diol of A4 (synthesized from A4 in water)[ 27 , 35 ] was dissolved in DMSO‐d 6, showing that 47 % of the mixture remained as the hydrated form, while the rest either reverted to the parent aldehyde (49 %) or evolved to the bis‐hemiacetal structures (4 %) (Scheme 2). By adding a drop of D2O to the NMR tube, the bis‐hemiacetal content was depleted, and the gem‐diol increased its percentage to 53 % (Scheme 2 and Figure S13). These results evidenced that the stability of the gem‐diol or hemiacetal form is extremely dependent on the solvent used.

Scheme 2.

Chemical conversion of the solid gem‐diol form of A4 in DMSO‐d 6.

The results obtained at low pH in the presence of TFA indicated a high content of the gem‐diol/hemiacetal forms in the corresponding solvents (Table 1), evidencing that the protonation of the pyridine ring increased both the electro‐attracting effect of the nitrogen atom and the reactivity of the aldehyde group, in parallel with the transient protonation of the carbonyl group. [36]

When aprotic solvents, as DMSO‐d 6, were used, the hydrated form was either observed in a very low proportion or was not observed at all, even in the presence of TFA due to the low water content (Table 1).[ 37 , 38 ]

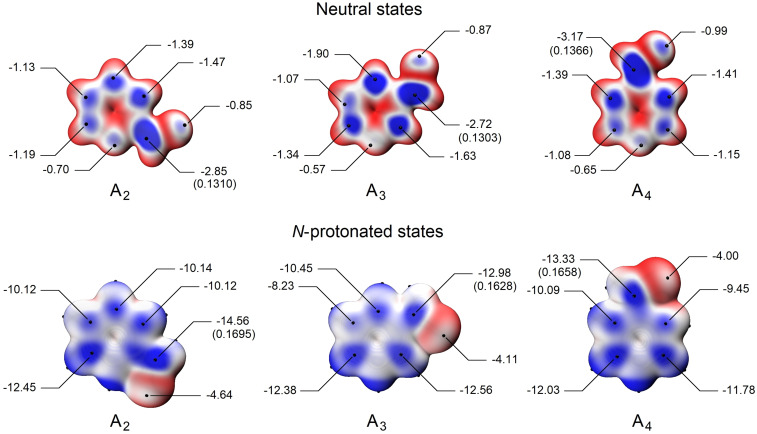

To further study the reactivity profile of pyridinecarboxaldehydes against weak nucleophiles such as water or methanol, we used molecular modelling techniques based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) to model the structure and molecular properties of compounds A2 , A3 and A4 . In this context, each compound was initially considered to be in a neutral state and was modelled as a conformational ensemble by applying the CREST+CENSO strategy. Next, taking the lowest energy conformer as a representative structure of each cluster, two independent computational simulation methodologies were applied for the estimation of the relative electrophilicity of each carbonyl group: the Hirshfeld charge distribution and the local electron attachment energy (LEAE). [39] When the Hirshfeld charges were calculated in vacuo, the carbon atom of the carbonyl group at positions 2 and 4 of the pyridine ring showed the highest positive charge densities. In the absence of net charge on the pyridine ring, the order of reactivity based on the calculated charge distribution was A4 >A2 >A3 (Figure 2). According to the computed Hirshfeld charges, however, the protonation of the pyridine nitrogen changed the predicted order of reactivity to A2 >A4 >A3 . Since these results only explain the experimental profile observed in neutral conditions, the calculations were repeated with the inclusion of implicit solvents. Regardless of the solvent used (water, methanol, or DMSO), the calculated Hirshfeld charge distribution predicted the reactivity of the carbonyl group of the neutral species as A4 >A3 >A2 . The protonation of the pyridine nitrogen atom in the three isomers changed this order to A2 >A4 >A3 .

Figure 2.

Computed ES(r) values for compounds A2 , A3 and A4 at the 0.004 au isodensity surface for neutral (upper panel) and N‐protonated (lower panel) species, considered in vacuo. Images coloured according to a red‐to‐blue scale, being the blue regions the ones with the lowest ES(r) values. The points indicated by lines represent the lowest values on the isodensity surface (ES,min), expressed in eV units. The values indicated in brackets correspond to computed Hirshfeld partial charges on the respective reactive center.

Therefore, in vacuo calculations were suitable to predict the order of reactivity in neutral conditions for the three compounds, and the N‐protonation observed in an acidic medium. In this context, the LEAE methodology, [39] which is recommended for the study of nucleophilic reactions, was applied in further theoretical calculations. This methodology allows predicting the reactivity of electrophilic centers for the nucleophilic attack based on the value adopted by the electronic descriptor ES,min. The latter parameter indicates that the lower the value reached, the higher the electrophilic character of the reactive center, and therefore, the higher susceptibility to nucleophilic attack. In the absence of net charge on the pyridine ring, the order of reactivity of the carbonyl carbon in the nucleophilic reaction, based on the ES,min values calculated in vacuo, was A4 >A2 >A3 (Figure 3). However, the protonation of the nitrogen atom changed the order of reactivity to A2 >A4 >A3 , thus repeating the profile predicted by the Hirshfeld charges. The ES,min calculated in the presence of any of the three solvents for the neutral forms was A4 ≥A2 >A3 . The calculated ES,min values for species that are protonated in the nitrogen atom allowed assigning the following order of reactivity with either any solvent or in vacuo as A2 >A4 >A3 , which is the same order as that obtained through the calculations of the Hirshfeld charges.

Figure 3.

Computed ES(r) values for compounds B1 and B4 at the 0.004 au isodensity surface for N‐protonated species, considered in methanol media. Images coloured according to a red‐to‐blue scale, being the blue regions the ones with the lowest ES(r) values. The points indicated by lines represent the lowest values on the isodensity surface (ES,min), expressed in eV units. The values indicated in brackets correspond to computed Hirshfeld partial charges on the respective reactive center.

Both methodologies predicted the order of experimental reactivity in vacuo under neutral conditions. However, the LEAE methodology also achieved accurate predictions in the presence of different solvents. Under acidic conditions, both computational methods predicted the order of reactivity observed for the gem‐diol and hemiacetal generation when the species considered were N‐protonated and in vacuo or in the presence of the indicated solvents.

Gem‐Diol and Hemiacetal Generation in Imidazolecarboxaldehydes

The 1H‐NMR spectra of the three imidazolecarboxaldehyde derivatives, 2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde (B1 ), N‐methyl‐2‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde (B2 ) and 4‐imidazolecarboxaldehyde (B4 ), under neutral conditions, indicated that the hydrate form is not generally present in D2O and that the hemiacetal form is generated in CD3OD (Table 2). The three compounds exhibited a higher susceptibility to the nucleophilic addition of CD3OD molecules, as compared to D2O, a solvent where only B2 shows 2 % of gem‐diol content. Moreover, the 1H‐NMR spectra of the isomers in DMSO‐d 6 only showed the presence of the aldehyde form (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative percentages of gem‐diol (GD), aldehyde (AL) and hemiacetal (HA) forms of each imidazolecarboxaldehyde obtained from the 1H‐NMR spectra under different experimental conditions.

The 1H‐NMR spectra of B1 , B2 and B4 dissolved in D2O or CD3OD with 1 % of TFA evidenced an increase in the reactivity towards the nucleophilic addition of water or methanol molecules. In previous reports, the dissolution of compound B2 in D2O/TFA induced the generation of both the gem‐diol and the bis‐hemiacetal molecules. [28] Furthermore, the formation of the hemiacetal of the corresponding imidazolecarboxaldehyde was enhanced in CD3OD under acidic conditions (Table 2).

Although one of the nitrogen atoms of the imidazole ring has pyridine characteristics, the behavior of these heterocycles differs from that of the pyridinecarboxaldehydes in solution. [29] On the other hand, as with pyridinecarboxaldehydes, the presence of the acid medium favors the addition of weak nucleophiles. This could be partially explained in terms of the Hirshfeld charges (Figure 3), because these cannot explain the observed reactivity order when B2 is considered. Nevertheless, computed charges only predict the higher reactivity of B1 relative to B4 , in acidic medium for all the solvents studied, as well as in vacuo, when the mono protonated species are having into account.

The LEAE methodology applied to imidazole compounds as neutral forms rendered ES,min values that predicted a reactivity that was higher for B1 than for B4 , regardless of the reaction medium. However, the ES,min value could not explain the reactivity order corresponding to B2 . Using an implicit solvent for protonated imidazole derivatives, the experimental order of reactivity observed for compounds B1 and B4 was consistent with the calculated ESmin (Figure 3).

Pyridine‐ and Imidazole‐Carboxaldehydes in Alkaline Medium

The reactivity of pyridine‐ and imidazole‐carboxaldehydes was evaluated in alkaline medium using the same solvents and the results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. For imidazole derivatives (B1 , B2 , and B4 ) in 0.1 M NaOH in D2O or DMSO‐d 6, the aldehyde group was predominantly observed as it was reported by Grimmet. [40] An exception occurred in 0.1 M NaOH in methanol, where B4 was converted to the hydroxymethyl and the sodium carboxylate moieties, products of the Cannizzaro reaction,[ 11 , 41 ] in which two molecules of a nonenolizable aldehyde are disproportionated by a base to produce a carboxylic acid and a primary alcohol. In this case, the high content of carboxylic acid may be due to some degree of oxidation of the hemiacetal derivatives in methanol (Table 2). Likewise, B4 showed a minor content of the hemiacetal form in 0.1 M NaOH in methanol. Particularly, those isomers that do not have the methyl group in the pyrrolic nitrogen remain in the carbonyl form in a basic medium.

Table 3.

Relative percentages of gem‐diol (GD), aldehyde (AL), hemiacetal (HA), sodium carboxylate (SC) and hydroxymethyl (ALC) forms of each imidazolecarboxaldehyde compound obtained from the 1H‐NMR spectra under different experimental conditions.

|

1H‐NMR |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B1 |

B2 |

B4 |

||||||||

|

Experimental condition |

AL |

HA |

GD |

AL |

HA |

SC |

ALC |

GD |

AL |

HA |

|

0.1 M NaOH in D2O |

100 [29] |

– |

– |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

100 |

– |

|

0.1 M NaOH in CD3OD |

100 |

– |

– |

4 |

– |

60 |

36 |

– |

96 |

4 |

|

0.1 M NaOH in DMSO‐d 6 |

100 |

– |

– |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

100 |

– |

Table 4.

Relative percentages of gem‐diol (GD), aldehyde (AL), hemiacetal (HA), sodium carboxylate (SC) and hydroxymethyl (ALC) forms of each pyridinecarboxaldehyde compound obtained from the 1H‐NMR spectra under different experimental conditions.

|

1H‐NMR |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Experimental condition |

GD |

AL |

HA |

SC |

ALC |

GD |

AL |

HA |

SC |

ALC |

GD |

AL |

HA |

SC |

ALC |

|

0.1 M NaOH in D2O |

21 |

48 |

– |

21 |

10 |

70 |

12 |

– |

9 |

9 |

47 |

43 |

‐ |

5 |

5 |

|

0.4 M NaOH in D2O |

nd [a] |

– |

– |

– |

51 |

49 |

7 |

7 |

‐ |

43 |

43 |

||||

|

0.1 M NaOH in CD3OD |

nd [a] |

– |

26 |

74 |

– |

– |

– |

4 |

96 |

– |

– |

||||

|

0.4 M NaOH in CD3OD |

nd [a] |

nd [a] |

– |

– |

81 |

14 |

5 |

||||||||

|

0.1 M NaOH in DMSO‐d 6 |

nd [a] |

– |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

18 |

82 |

– |

– |

– |

||||

|

0.4 M NaOH in DMSO‐d 6 |

nd [a] |

nd [a] |

40 |

60 |

– |

– |

– |

||||||||

[a] Particularly, it is very difficult to analyze this sample due to its decomposition and chemical reactions.

On the other hand, the pyridinecarboxaldehyde isomers displayed higher reactivity in the Cannizzaro reaction than the imidazolecarboxaldehydes, influenced by the position of the aldehyde group and the solvent. In this sense, 0.1 or 0.4 M NaOH solutions were studied in the different solvents (Table 4).

For A3 , the Cannizzaro reaction products were favored at both 0.1 and 0.4 M NaOH solutions in D2O. However, 70 % of the gem‐diol for A3 was obtained at 0.1 M NaOH. With 0.4 M NaOH concentration the reaction was quantitative with the hydroxymethyl and sodium carboxylate derivatives as the main products. Furthermore, in the last condition the aldehyde or gem‐diol forms were not observed. In 0.1 M NaOH in CD3OD, only the hemiacetal and aldehyde forms were detected with no acetal or Cannizzaro products. In DMSO‐d 6, A3 remained solely in its aldehyde form (Table 4).

Besides, A4 shows greater susceptibility to the Cannizzaro reaction in both water and methanol solvents, being quantitative higher in water. In methanol, the reaction condition requires higher NaOH concentrations. In DMSO‐d 6, only the gem‐diol and aldehyde forms were detected. Remarkably, 47 % of gem‐diol form was generated with 0.1 M NaOH in D2O with a significant reduction to 7 % with 0.4 M NaOH in D2O.

Finally, A2 displays the products of the Cannizzaro in a similar content than A3 and A4 in 0.1 M NaOH in D2O, but with a lower evolution to the gem‐diol generation. Also, some degree of oxidation to the carboxylic acid form is observed (Table 4). Particularly, no other NMR studies were conducted for A2 due to its higher tendency to render degradation products, hindering the assignment of the NMR signals. In this sense, the analysis of A3 at 0.4 M NaOH in methanol or DMSO‐d 6 was also intricated due to multiple side products.

Regarding the gem‐diol generation, A3 shows the higher reactivity to the hydrate formation in comparison with A4 and A2 in alkaline medium (Table 4). This higher percentage of hydration for A3 was not expected in the context of this study, where both A2 and A4 compounds showed similar percentages of hydration than in D2O (Table 1).

Conclusions

This work assessed the generation of the gem‐diol or hemiacetal forms derived from pyridine‐ and imidazolecarboxaldehyde derivatives, as well as its stability in various chemical environments in solution. The solution‐state NMR studies indicated that the position of the formyl group was essential to stabilize the gem‐diol or hemiacetal form.

Pyridinecarboxaldehydes showed a great dependance on protic solvents for the gem‐diol/hemiacetal generation as well as on the protonation state of pyridine ring.

The computed Hirshfeld charge distribution for the studied pyridinecarboxaldehydes was a good predictor of the order of experimental reactivity in vacuo under neutral conditions. The LEAE methodology was equally useful to predict reactivities in the presence of the different solvents. Both methodologies predicted the order observed when the species considered were N‐protonated in the presence of each solvent.

Particularly, the three pyridinecarboxaldehyde isomers showed greater reactivity to the methanol molecule addition in CD3OD in neutral conditions, relative to the behavior observed in water.

On the other hand, imidazolecarboxaldehydes showed much more dependance on the protonation state on the pyridine‐type nitrogen for the nucleophilic reaction. Notably, the hemiacetal generation was increased in CD3OD, even when the three compounds remained practically in the aldehyde form in D2O.

Computed Hirshfeld charges and ES,min provided a limited explanation about the order of reactivity in acidic media for compounds B1 and B4 and the reactivity of compound B2 could not be explained by the calculated parameters.

As for gem‐diol generation in alkaline medium, A3 showed the highest reactivity to the hydrate formation compared with A4 and A2 . This unexpected result allows us to continue studying the behavior of this type of aldehyde derivatives in different aromatic heterocyclic compounds through theoretical calculations and experimental analysis.

Regarding the Cannizzaro reaction, the pyridinecarboxaldehydes were highly reactive than the imidazolecarboxaldehydes, influenced by the position of the aldehyde group and the solvent, being A3 quantitative converted to the carboxylic acid and alcohol moieties in 0.4 M NaOH in D2O. For A4 the reaction also took place, but the gem‐diol and aldehyde forms remained in low content.

Finally, the NMR spectroscopy was useful to analyze the evolution of the aldehyde to the gem‐diol/hemiacetal forms in a fast and simple way while allowing the evaluation of a wide range of solvents and acidity degree of the medium. Thus, this method is a very useful tool to evaluate the chemical composition in cases where the hydroxymethyl, carbonyl, gem‐diol, hemiacetal, acetal and oxidized forms coexist for a particular carbonyl compound with electron withdrawing character.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

This work was performed with the financial support from ANPCYT (PICT 2019‐00845) and Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBACyT 2020‐2024/11BA). A.F.C., G.J. and E.B. thank Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnológicas (CONICET) for their Posdoctoral and his Doctoral Fellowships, respectively. Authors would like to thank Dr. G. Nuñez‐Taquía for the English grammar revision.

Crespi A. F., Barrionuevo E., Jasinski G., Moglioni A. G., Vega D., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., ChemistryOpen 2025, e202400411. 10.1002/open.202400411

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Bell R. P., McDougall A. O., Trans. Faraday Soc. 1960, 56, 1281. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang Q., Yu Z., Wang Q., Li W., Gao F., Li S., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 383, 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jinzaki T., Arakawa M., Kinoshita H., Ichikawa J., Miura K., Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3750–3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rawashdeh A. M. M., Thangavel A., Sotiriou-Leventis C., Leventis N., Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1131–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.E. J. Corey, Xue-Min Cheng, The Logic of Chemical Synthesis, Wiley, 1995.

- 6. Guan Q., Zhou L.-L., Dong Y.-B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 1475–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu K., Wang Y., Hirao H., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4175–4179. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bilbeisi R. A., Olsen J.-C., Charbonnière L. J., Trabolsi A., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 417, 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- 9.J. Lewiński, D. Prochowicz, Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II, Elsevier, 2017, 279–304.

- 10. Crespi A. F., Campodall orto V., Lázaro Martínez J. M., Diols: Synthesis and Reactions (Ed.: Ballard E.), Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2020, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verma D. K., Dewangan Y., Verma C., Handbook of Organic Name Reactions, Elsevier, 2023, 155–241. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bo Z., Sitong C., Weiming G., Weijing Z., Lin W., Li Y., Jianguo Z., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pocker Y., Meany J. E., Nist B. J., J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 4509–4513. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang B., Cao Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3266–3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe S., Kim C.-K., Yang K., Weinberg N., Shi Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 4240–4260. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu C., Zeng X. C., Francisco J. S., Gladich I., J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 5574–5582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loh T.-P., Feng L.-C., Wei L.-L., Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 7309–7312. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaptein B., Kellogg R. M., van Bolhuis F., Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1990, 109, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barman S., Diehl K. L., Anslyn E. V., RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 28893–28900. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li J.-J., Li C., Blindauer C. A., Bugg T. D. H., Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12461–12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleming S. M., Robertson T. A., Langley G. J., Bugg T. D. H., Biochemistry 2000, 39, 1522–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fu G., Kang X., Zhang Y., Guo Y., Li Z., Liu J., Wang L., Zhang J., Fu X.-Z., Luo J.-L., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crespi A. F., Zomero P. N., Sánchez V. M., Pérez A. L., Brondino C. D., Vega D., Rodríguez-Castellón E., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., Chempluschem 2022, 87, DOI: 10.1002/cplu.202200169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crespi A. F., Sánchez V. M., Vega D., Pérez A. L., Brondino C. D., Linck Y. G., Hodgkinson P., Rodríguez-Castellón E., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 20216–20231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crespi A. F., Vega D., Pérez A. L., Rodríguez-Castellón E., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 26, e202200737. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Y., Li Y., Ni Y., Bučar D.-K., Dalby P. A., Ward J. M., Jeffries J. W. E., Hailes H. C., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 2390–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crespi A. F., Vega D., Chattah A. K., Monti G. A., Buldain G. Y., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 7778–7785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crespi A. F., Byrne A. J., Vega D., Chattah A. K., Monti G. A., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lázaro Martínez J. M., Romasanta P. N., Chattah A. K., Buldain G. Y., J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3208–3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crespi A. F., Vega D., Sánchez V. M., Rodríguez-Castellón E., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 13427–13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minegishi S., Kobayashi S., Mayr H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5174–5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bondue C. J., Spallek M., Sobota L., Tschulik K., ChemSusChem 2023, 16, 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deposition number 2362091 (for CA3) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- 34. Athimoolam S., Natarajan S., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2007, 63, o2656–o2656. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crespi A. F., Lázaro-Martínez J. M., J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 4536–4542. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klumpp D. A., Zhang Y., Kindelin P. J., Lau S., Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 5915–5921. [Google Scholar]

- 37. El-Shall M. S., Ibrahim Y. M., Alsharaeh E. H., Meot-Ner (Mautner) M., Watson S. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10066–10076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chmurzyński L., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2000, 37, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brinck T., Carlqvist P., Stenlid J. H., J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 10023–10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grimmett M. R., Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, Elsevier, 1984, 373–456. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luca O. R., Fenwick A. Q., J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 152, 26–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bastiaansen L. A. M., Van Lier P. M., Godefroi E. F., Organic Syntheses, Wiley, 2003, 72–72. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bastiaansen L. A. M., Godefroi E. F., J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 1603–1604. [Google Scholar]

- 44.GaussView, Version 6.1, Roy Dennington, Todd A. Keith, and John M. Millam, Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016..

- 45.M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, D. Williams-Young, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery, Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, D. J. Fox, Gaussian 16, Rev. C. 01 2016.

- 46. Brandenburg J. G., Caldeweyher E., Grimme S., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 15519–15523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grimme S., Bohle F., Hansen A., Pracht P., Spicher S., Stahn M., J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 4039–4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pracht P., Bohle F., Grimme S., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7169–7192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neese F., WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, DOI: 10.1002/wcms.1606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marenich A. V., Cramer C. J., Truhlar D. G., J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu T., Chen F., J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.