Abstract

This study presents the development and validation of a fluorescence-based high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method for the quantification of alectinib in rat plasma, with a focus on the application of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) to bioanalytical method development. Unlike conventional QbD applications, which primarily address synthetic formulations or instrumental settings, this study systematically applied AQbD principles to the complex environment of biological matrices. Critical method parameters, including the organic phase ratio, buffer concentration, and flow rate, were identified through Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, and optimized using a Box–Behnken design. The final method exhibited excellent linearity (R² >0.99) over a concentration range of 5–1,000 ng/mL, with a lower limit of quantification of 5 ng/mL. It also showed high accuracy (95.6–102%), precision (relative standard deviation < 11%), and consistent recovery (98.3–105%), with minimal matrix effects. Alectinib stability was confirmed under various handling conditions. This method was successfully applied in a pharmacokinetic study after intravenous and oral administration of alectinib in rats. These results highlight the value of AQbD in addressing specific challenges of bioanalysis and demonstrate its utility in establishing a sensitive, robust, and regulatory-compliant method suitable for pharmacokinetic applications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13065-025-01613-z.

Keywords: Alectinib, Analytical quality by design, Taguchi method, Box–Behnken design, Method development and validation

Introduction

Alectinib is a potent and selective second-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor that has significantly improved the treatment of patients with ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Initially approved for use in patients who had progressed on or were intolerant to crizotinib [1], alectinib is now recommended as a first-line therapy based on the results of several landmark clinical trials [2]. In the global phase III ALEX trial, alectinib demonstrated a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 34.8 months compared to 10.9 months with crizotinib [3]. It also resulted in a significantly lower risk of central nervous system (CNS) progression, with a response rate of 81% versus 50% for crizotinib [4]. Similarly, the J-ALEX trial, conducted in a Japanese population, confirmed the superior efficacy of alectinib in terms of PFS, overall response rate (ORR), and CNS activity [5]. These findings have led to regulatory approval worldwide, including by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and other health authorities, with a standard dosage of 600 mg administered orally twice daily [2, 6].

In addition to its established role in advanced or metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC, alectinib is currently under investigation for multiple expanded indications. A key area of research is their use in adjuvant settings. The ALINA trial (NCT03456076), a randomized phase III study, recently demonstrated that alectinib significantly reduced the risk of disease recurrence or death compared with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with resected, early stage (IB–IIIA) ALK-positive NSCLC [7]. These results suggest that alectinib is a standard option for adjuvant therapy following curative surgery to prevent relapse and improve long-term survival. Alectinib is also being explored as a combination therapy for other tumor types harboring ALK rearrangements. Studies have evaluated its efficacy in pediatric malignancies such as ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and rare ALK-driven cancers, including inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) [8–10]. Furthermore, studies evaluating the possibility of combination regimens involving alectinib and DNA-demethylating agents or anti-angiogenic agents have shown promising efficacy, providing an additional strategy to overcome resistance and enhance therapeutic outcomes in patients with cancer [11, 12].

Alectinib displays characteristic oral pharmacokinetics, with plasma concentrations rising gradually following administration and reaching peak levels at approximately 4 to 6 h post-dose. After reaching the maximum concentration, plasma levels decline slowly, reflecting a prolonged elimination half-life of 20 to 24 h [13]. The pharmacokinetic profile was dose-proportional across a dosing range of 300–900 mg twice daily, supporting predictable systemic exposure. Hepatic metabolism plays a predominant role in the biotransformation of alectinib, primarily through cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) [14, 15], and clinical mass balance studies have confirmed that elimination occurs mainly via the hepatobiliary route, with fecal excretion accounting for the majority of alectinib clearance and minimal renal involvement [13].

The accurate and reliable quantification of alectinib in biological matrices is essential for understanding its pharmacokinetic behavior and optimizing its clinical application. In bioanalytical studies, validated analytical methods must meet rigorous standards for accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and matrix compatibility in line with regulatory guidelines set by agencies such as the FDA of the United States and EMA. To date, several methods have been developed for the quantification of alectinib, most notably, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with ultraviolet (UV) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection [16, 17]. Although liquid chromatography-MS/MS (LC-MS/MS) methods offer high sensitivity and specificity, their complexity, cost, and maintenance requirements limit their routine accessibility. In contrast, UV-based HPLC methods are more cost-effective but typically lack the sensitivity necessary to detect alectinib at low plasma concentrations [18]. Despite the increasing demand for robust and practical bioanalytical methods, no fluorescence detector (FLD)-based HPLC method has been reported for the quantification of alectinib in plasma. As alectinib continues to be investigated in diverse clinical settings, the development of various analytical methods that can reliably support preclinical pharmacokinetic evaluations is essential to enable translational research and ensure successful therapeutic expansion.

In recent years, Quality by Design (QbD) has become a foundational paradigm in pharmaceutical development, providing a structured, science-based, and risk-oriented approach to method and process optimization [19, 20]. The central principle of QbD is to design quality into a product or method from the outset rather than relying solely on end-product testing. This is achieved by defining a quality target product profile (QTPP), identifying critical quality attributes (CQAs), and understanding the relationships between critical process parameters (CPPs) and CQAs through systematic experimentation and modeling. The ultimate goal is to establish a robust design space, a multidimensional combination of input variables, and process parameters, that consistently delivers the desired quality within acceptable variability. In the realm of analytical science, these principles have been adapted and refined into what is now known as Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD). AQbD extends the QbD framework to the development and validation of analytical methods, emphasizing early-stage risk assessment, multivariate optimization, and lifecycle management. Compared with conventional method development strategies, often characterized by trial-and-error or one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) testing, AQbD offers several advantages, such as improved method robustness, greater regulatory flexibility (e.g., post-approval change management), and enhanced scientific understanding of method performance and failure modes [21, 22].

Therefore, we developed and validated a fluorescence-based HPLC method for quantifying alectinib in rat plasma using the AQbD approach. The method development process included a systematic risk assessment using Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), screening and optimization of critical method parameters using the Taguchi method and Box–Behnken Design (BBD), and full validation according to bioanalytical guidelines. The final method was applied in a pharmacokinetic study in rats to demonstrate its suitability for preclinical drug development. This work not only addresses a methodological gap in the quantification of alectinib but also provides a practical example of how AQbD can be effectively applied to the development of robust, regulatory-compliant bioanalytical methods.

Materials and methods

Materials and methods

Alectinib and ponatinib (Fig. 1), with purities of 99.78% and 99.67% respectively, were obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Reagents including dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), potassium dihydrogen phosphate, potassium hydrogen phosphate, N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC), Cremophor EL, and 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Blank plasma samples from heparinized ICR mice, Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, and humans were commercially obtained from Innovative Research (Novi, MI, USA), and intravascular catheters for the cannulation of rat thoracic jugular veins were purchased from Braintree Science (Braintree, MA, USA). All the solvents used for chromatography and sample preparation, including HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile, were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Ultrapure water, suitable for analytical use, was purchased from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, PA, USA). All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of (A) alectinib and (B) the internal standard (ponatinib)

Risk assessment and factor screening study

To establish a robust and reliable LC-FLD-based analytical method for the quantification of alectinib in rat plasma, a systematic risk assessment was conducted according to the QbD framework. FMEA was employed to prioritize potential method parameters that could influence assay performance. Each parameter was evaluated based on three criteria: probability of occurrence, severity of impact on the CAAs, and detectability of the failure mode. These values were multiplied to generate a Risk Priority Number (RPN), which was used to determine the relative importance of each factor (Table 1). Eleven method parameters were subjected to risk assessment, including injection volume, mobile phase composition, organic solvent ratio, mobile phase pH, buffer concentration, flow rate, sample temperature, column temperature, detection wavelength, sample pretreatment method, and column type. Based on the FMEA results, seven parameters with higher RPN values (> 20) were selected for further investigation using the Taguchi design of experiments.

Table 1.

FMEA for risk assessment in HPLC-FLD method development by AQbD

| Parameter | Effect | Probability | Severity | Detectability | RPN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injection volume* | Changes in peak resolutions | 2 | 3 | 4 | 24 |

| Mobile phase composition | Changes in retention time, peak resolutions, and shape | 2 | 3 | 3 | 18 |

| Organic phase %* | Changes in retention time and peak resolutions | 3 | 3 | 3 | 27 |

| Mobile phase pH* | Changes in retention time, peak resolutions, and shape | 4 | 3 | 2 | 24 |

| Buffer concentration * | Changes in retention time, peak resolutions, and shape | 3 | 2 | 4 | 24 |

| Flow rate* | Changes in retention time and peak resolutions | 3 | 4 | 2 | 24 |

| Sample temperature | Degradation of analyte and changes in peak resolutions | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Column temperature* | Changes in retention time and peak resolutions | 3 | 3 | 3 | 27 |

| Detection wavelength | Decrease of sensitivity or selectivity | 2 | 3 | 2 | 12 |

| Sample pretreatment method* | Changes of matrix effects or reproducibility | 3 | 4 | 3 | 24 |

| Column type | Changes in retention time, peak resolutions and shape | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

RPN: risk priority number

* Selected for the factor screening assay

A Taguchi L8 orthogonal array was employed to screen these parameters efficiently and to evaluate their influences on CAAs. The selected factors included the injection volume, organic phase ratio, mobile phase pH, buffer concentration, flow rate, column temperature, and sample pretreatment method. Each parameter was tested at two levels that were determined based on preliminary experiments (Table S1). Eight experiments were performed using rat plasma samples spiked with 10 ng/mL alectinib. For each run, chromatographic performance was assessed by evaluating the peak area, retention time, and theoretical plate number. Additionally, the resolutions between the alectinib peak and the adjacent peaks were included as CAAs to ensure adequate selectivity, given the complexity of the plasma matrices. The collected data were analyzed using Design-Expert® software version 13.0.5.0 (Stat-Ease Inc., USA). A main-effects linear model was used to assess the contribution of each factor to the variation in CAAs.

Method optimization using response surface methodology

Following the screening study using the Taguchi design, three CMPs (organic phase ratio, buffer concentration, and flow rate ) were identified as significantly influencing the key chromatographic responses and were selected for further optimization. The goal of the optimization process was to maximize the peak area and ensure a theoretical plate number above 8000, a retention time below 10 min, and a resolution above 2.0 (Table 2). A three-factor, three-level BBD was applied to explore the effects and interactions of the CMPs. The selected levels of the CMPs were as follows: organic solvent ratios (60, 70, and 80%), flow rates (0.8, 1.0, and 1.2 mL/min), and buffer concentrations (10, 15, and 20 mM). A total of 15 experimental runs were performed, including 12 at the midpoints of the edges of the design cube and three replicates at the center point, to assess the experimental error and ensure model reliability. Experimental data were analyzed using Design-Expert® software version 13.0.5.0. A second-order polynomial regression model incorporating linear, interactive, and quadratic terms was used to fit the data. The model equation for each CAA was expressed as follows:

Table 2.

Goals to independent and dependent variables for analytical method optimization

| Variables | Goal | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||

| Organic phase ratio (%) | In range | 60 | 80 |

| Buffer concentration (mM) | In range | 10 | 20 |

| Flow rate (mL/min) | In range | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Dependent variables | |||

| Theoretical plate number | In range | 8000 | - |

| Retention time (min) | In range | - | 10 |

| Peak area (LU·s) * | Maximize | 2.5 | |

| Resolution 1 | In range | 2 | - |

| Resolution 2 | In range | 2 | - |

* The optimization objective was to maximize the peak area, while the design space was constrained to ensure a minimum response of 2.5 LU·s, which is sufficient to meet the sensitivity required for achieving a LLOQ of 5 ng/mL

|

where Y is the predicted response (e.g., theoretical plate number, retention time, peak area, and resolution, ); A, B, and C represent the organic solvent ratio, flow rate, and buffer concentration, respectively; and β₀ to β₉ denote the regression coefficients.

The adequacy of the fitted models was evaluated by using analysis of variance (ANOVA), model p-values, lack-of-fit tests, coefficient of determination (R²), and diagnostic plots, such as normal probability plots of residuals and predicted versus actual plots. Both numerical and graphical optimization approaches were employed to identify the optimal method conditions and define the design space in which a robust analytical performance can be achieved.

Model validation and predictive performance

A validation study was conducted to assess the predictive capability and robustness of the proposed model. Five validation experiments were conducted under randomly selected conditions in the established design space. For each condition, the observed chromatographic responses were compared with the values predicted by the model. Predictive accuracy was evaluated by calculating the percent prediction error (%PE) using the following equation:

|

HPLC conditions

Chromatographic analysis was performed using an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC system equipped with an FLD (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Separation of alectinib and the internal standard (IS, ponatinib) from endogenous components was achieved on a Gemini® NX-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), maintained at 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 16 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.8) and acetonitrile at a 40:60 (v/v) ratio, delivered at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The total run time was 10.5 min per sample. The autosampler was maintained at 10 °C, and detection was performed using fluorescence with excitation and emission wavelengths of 342 and 461 nm, respectively. Data acquisition and processing were conducted using the Agilent ChemStation software.

Sample preparation

To extract alectinib from plasma, 20 µL of rat plasma was combined with 100 µL of acetonitrile containing the IS (ponatinib, 100 ng/mL). This protein precipitation step was carried out by vortexing the mixture for 4 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 4 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the clear supernatant was carefully transferred into an HPLC vial, and a 10 µL aliquot was injected for chromatographic analysis.

Preparation of standard and quality control samples

Stock solutions of alectinib and the IS were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Working solutions of alectinib were subsequently obtained by serial dilution with 70% methanol in water. The IS working solution was diluted with methanol to a final concentration of 100 ng/mL in acetonitrile. Calibration standards were generated by mixing 18 µL of blank rat plasma with 2 µL of the appropriate working solution, resulting in final alectinib concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 750, and 1,000 ng/mL. Quality control (QC) samples were independently prepared using the same procedure at concentrations of 15 ng/mL (low QC, LQC), 100 ng/mL (medium QC, MQC), and 800 ng/mL (high QC, HQC).

Analytical method validation

The HPLC method developed to quantify alectinib in the rat plasma was validated in accordance with the guidelines provided by the US FDA and EMA [23, 24]. The validation parameters included selectivity, sensitivity, linearity, accuracy, precision, recovery, matrix effects, stability, dilution integrity, and carryover.

Selectivity was assessed using blank plasma from six different rats to confirm the absence of interfering endogenous peaks at the retention times of alectinib and the IS. Sensitivity was determined by evaluating the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), which was defined as the lowest concentration with acceptable accuracy (within ± 20%) and precision (relative standard deviation [RSD] ≤ 20%). Calibration curves were established using plasma samples spiked with alectinib at concentrations ranging from 5 to 1,000 ng/mL. The response was plotted using weighted (1/x²) linear regression analysis. Linearity was confirmed based on the R² and the back-calculated concentrations. Intra- and inter-day accuracy and precision were evaluated at four levels: LLOQ (5 ng/mL), LQC (15 ng/mL), MQC (100 ng/mL), and HQC (800 ng/mL). For each level, five replicates were analyzed on three separate days. Accuracy was expressed as the percentage deviation from the nominal concentration and was required to be within ± 15% (± 20% for LLOQ). Precision was evaluated as RSD, with an acceptance criterion of ≤ 15% (≤ 20% for LLOQ).

Recovery was calculated by comparing the peak area of alectinib spiked before protein precipitation with that of the samples spiked after extraction at each QC level. Matrix effects were assessed by comparing the peak areas of the analytes spiked into post-extraction blank plasma with those spiked into a neat mobile phase. The same evaluation was applied to IS at 100 ng/mL.

The stability of alectinib in rat plasma was assessed under various storage and handling conditions using the LQC and HQC samples (n = 3). Stability tests included short-term (2 h at room temperature), long-term (3 weeks at − 20 °C), three freeze-thaw cycles, and post-preparative stability in the autosampler (10 °C for 24 h). Stability was determined acceptable if the concentration remained within ± 15% of the nominal value under each condition.

Dilution integrity was evaluated by spiking plasma samples with alectinib at 10 times the HQC level, followed by a 10-fold dilution with blank plasma. The samples were processed and analyzed as described above. Accuracy and precision after dilution were required to meet the acceptance criteria of ± 15% and RSD ≤ 15%. The carryover was assessed by injecting blank plasma samples immediately after reaching the highest calibration standard. The method was considered free of carryover if the peak area of alectinib in blank samples was less than 20% of that at the LLOQ and the IS response was less than 5% of the IS in standard samples.

Pharmacokinetic study of alectinib

All in vivo studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (approval no. KRIBB-AEC-25005). Male SD rats (Koatech, Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea) were acclimatized to standard laboratory conditions for at least 1 week before the study. The animals were provided with unrestricted access to food and water, except during an 8 h fasting period before drug administration, during which only water was available.

Alectinib was administered either orally or intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg using a formulation composed of DMAC, Cremophor EL, and 20% HPβCD in water at a volume ratio of 10:10:80. Oral administration was primarily selected because alectinib is clinically used via the oral route, and intravenous administration at the same dose was additionally conducted to evaluate absolute bioavailability. The dosing regimen (10 mg/kg) was selected by first converting the human clinical dose of alectinib to a rat equivalent dose based on body surface area (approximately 50 mg/kg), and then reducing it to about one-fifth (10 mg/kg) to broaden the applicability of the analytical method to various preclinical settings. For pharmacokinetic evaluation, blood samples were collected from the thoracic jugular vein into lithium-heparin-coated tubes at predetermined time points. Following cannulation, the animals were allowed to recover fully and were freely moving during the study period. The blood sampling time points for the IV group were 5 and 30 min and 1, 3, 5, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h post-dose (n = 3). In the oral group, blood samples were collected at 30 min and 1, 3, 5, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after administration (n = 3). Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 13,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and stored at − 20 °C until further analysis. At the end of the study, animals were euthanized using CO₂ inhalation, in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by non-compartmental analysis using PKanalix version 2024R1 (Lixoft, France). The area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to the last measurable concentration (AUClast) and extrapolated to infinity (AUCinf) were estimated using the linear trapezoidal method. The terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) was derived from the slope of the terminal log-linear portion of the concentration-time curve. Additional parameters, including total systemic clearance (CL) and steady-state volume of distribution (Vss), were determined. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach Cmax (Tmax) were determined directly from the data obtained after oral dosing. The absolute oral bioavailability was calculated by comparing the dose-normalized AUCinf values between the oral and intravenous groups.

The plasma stability of alectinib in mice, rats, and humans was evaluated in vitro. The alectinib working solution (1,000 ng/mL) was spiked into the blank plasma from each species to yield a final concentration of 100 ng/mL. The prepared plasma samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30, 60, and 120 min (n = 3 at each time point). At designated time points, the residual alectinib concentration was measured using the validated HPLC-FLD method. Based on these data, the percentage of alectinib remaining at each time point was calculated to determine the species-dependent plasma stability.

Results

Risk assessment and Taguchi screening study

An FMEA was conducted to systematically identify factors with a potential impact on method performance. Eleven method parameters were evaluated, and the organic phase ratio and column temperature showed the highest RPN values, indicating a high degree of risk associated with changes in the retention time and peak resolution. Several other parameters, including the injection volume, mobile phase pH, buffer concentration, flow rate, and sample pretreatment method, also yielded RPN values of 24 (Table 1). Based on the FMEA outcomes, seven parameters with RPN values ≥ 20 were selected for further analysis using a Taguchi L8 orthogonal array.

The main-effects model used in the Taguchi analysis showed good predictive ability with adjusted R² values of 0.9042, 0.9972, 0.9914, 0.9881, and 0.9345 for the theoretical plate number, retention time, peak area, resolution 1, and resolution 2, respectively. These values indicate that the selected factors effectively accounted for the variability in the system. ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the statistical significance of each factor on the CAAs, including the theoretical plate number, retention time, peak area, and resolution. Among the evaluated parameters, the organic phase ratio was identified as a statistically significant factor that influenced the theoretical plate number (p < 0.05), peak area (p < 0.01), and retention time (p < 0.05). The buffer concentration significantly affected the retention time (p < 0.05), peak area (p < 0.01), and resolution 1 (p < 0.05). Additionally, the flow rate had a notable impact on retention time (p < 0.01), peak area (p < 0.05), and resolutions 1 and 2 (p < 0.05). In contrast, the pretreatment method, injection volume, column oven temperature, and buffer pH exhibited limited or negligible effects on the CAAs within the tested range, suggesting that their influence on chromatographic performance was minimal. These findings highlight the critical importance of optimizing the organic phase ratio, buffer concentration, and flow rate to ensure robust and reproducible chromatographic performance for alectinib quantification in rat plasma.

Method optimization by BBD

BBD was employed to evaluate the influence of three CMPs, organic phase ratio (A), buffer concentration (B), and flow rate (C), on five CAAs: the theoretical plate number, retention time, peak area, resolution 1, and resolution 2. A quadratic regression model was constructed for each response variable, incorporating linear, interactive, and quadratic terms. The regression coefficients, adjusted R² values, and significance levels (p-values) for each model are listed in Table 3. All models were statistically significant (p < 0.01), with high adjusted R² values of 0.9382 for theoretical plate number, 0.9979 for retention time, 0.9001 for peak area, 0.9499 for resolution 1, and 0.9848 for resolution 2, indicating strong explanatory power and good model fit. The lack-of-fit was not significant for any of the models, confirming their reliability. For theoretical plate number, organic phase ratio (β₁ = − 1046.75) and flow rate (β₃ = − 1867.08) had strong negative linear effects, whereas the quadratic terms β₈ and β₉ also contributed significantly, suggesting a curvature in the response surface. For retention time, the organic phase ratio exhibited a dominant negative linear effect (β₁ = − 1.64), consistent with expectations that higher organic content leads to faster elution. Flow rate (β₃ = − 1.19) also negatively affected retention time. The interaction terms AB and AC exhibited a slight influence, indicating the importance of multivariate optimization rather than the OFAT approach. For peak area, the most influential factor was again the organic phase ratio, showing a negative linear effect (β₁ = − 0.5021) and significant interaction terms with buffer concentration (β₄ = − 0.1058) and flow rate (β₅ = 0.0737). Buffer concentration itself had a positive linear effect (β₂ = 0.1181), suggesting enhanced signal intensity at higher ionic strength within the tested range. In terms of resolution, the buffer concentration and organic phase ratio were the primary influencers. The interaction between buffer concentration and organic phase ratio (β₄ = 0.5233) showed a positive effect, indicating that their combined influence improved resolution. However, the main effect of buffer concentration (β₂ = − 0.1671) was slightly negative. For resolution 2, the flow rate had a positive effect, and the interaction terms between the organic phase and flow rate and between the buffer concentration and flow rate also negatively influenced the response. The negative quadratic terms indicated a curved response surface, suggesting that extreme values of buffer concentration and flow rate reduced the resolution.

Table 3.

Coefficients of polynomial equations for the quadratic model and their statistical parameters

| Coefficient code | Coefficient estimate for response variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Plate | Retention time | Peak area | Resolution 1 | Resolution 2 | ||

| β0 | 9425.89 | 5.49 | 2.38 | 1.48 | 4.77 | |

| β1 | -1046.75 | -1.64 | -0.5021 | 0.1921 | -0.6485 | |

| β2 | 134.42 | -0.0834 | 0.1181 | -0.1671 | -0.645 | |

| β3 | -1867.08 | -1.19 | -0.3983 | -0.0842 | 0.2673 | |

| β4 | 111.25 | 0.0645 | -0.1058 | 0.5233 | 0.2838 | |

| β5 | 216.92 | 0.3197 | 0.0737 | -0.2867 | -0.2067 | |

| β6 | -228.92 | 0.0147 | -0.087 | 0.0267 | -0.3162 | |

| β7 | 228.93 | 0.5697 | 0.0273 | 1.15 | -2.26 | |

| β8 | -492.9 | 0.0243 | -0.3782 | -0.2336 | -0.9942 | |

| β9 | 721.76 | 0.2244 | -0.1462 | 0.3547 | -0.4888 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9382 | 0.9979 | 0.9001 | 0.9499 | 0.9848 | |

| p value | 0.0013 | < 0.00001 | 0.0041 | 0.0008 | < 0.0001 | |

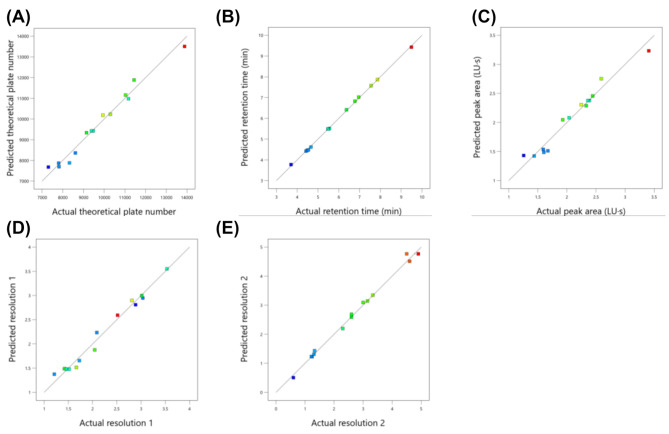

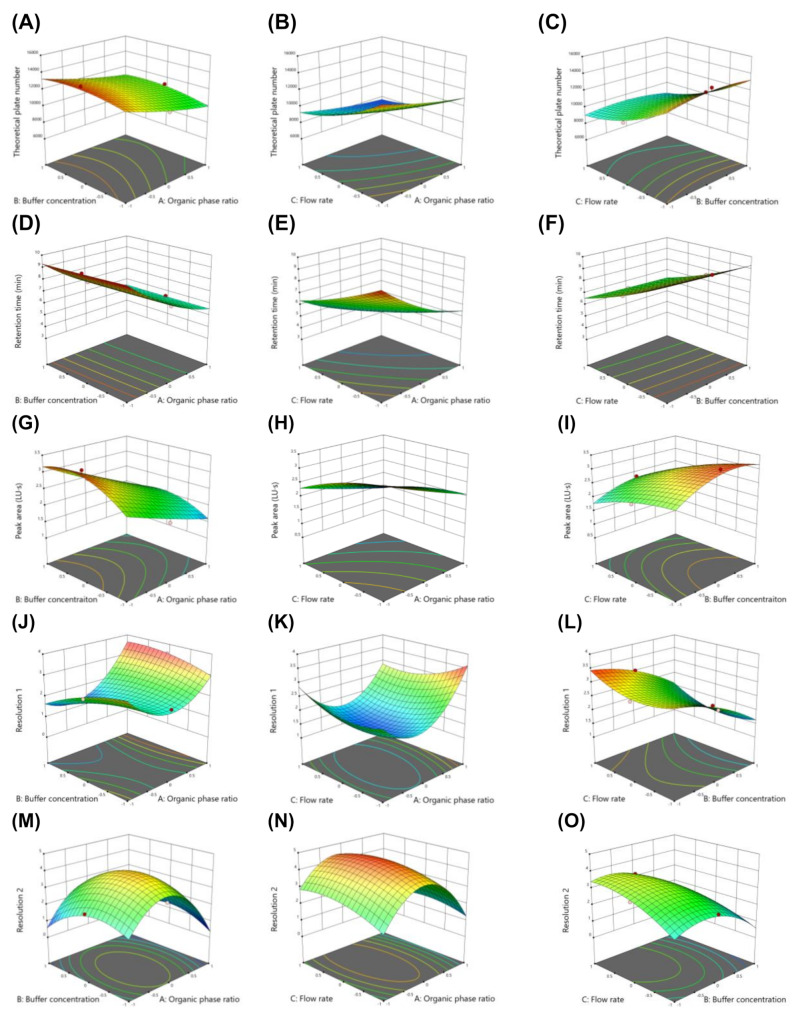

The model predictions were further validated by plotting the predicted versus the actual values (Fig. 2), which showed strong linear correlations with minimal scatter, thereby confirming the predictive accuracy of the models. In addition, two- or three-dimensional response surface plots (Figures S1 and 3) provided a comprehensive visualization of the factor effects and their interactions on each response.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of predicted versus actual chromatographic performance parameters using the AQbD-optimized HPLC method for determination of alectinib in rat plasma. (A) theoretical plate number, (B) retention time (min), (C) peak area (LU·s), (D) resolution 1, and (E) resolution 2. Each scatter plot displays the predicted values generated from the response surface model against the experimentally observed values

Fig. 3.

3D-response surface plots showing the influence of CMPs on CAAs. Effect of organic solvent ratio, flow rate, and buffer concentration on theoretical plate number (A-C), peak area (D-F), retention time (G-I), resolution 1 (J-L), and resolution 2 (M-O). Each CMP was tested with low (-1), middle (0), and high (1) levels of the following variables: organic solvent 60, 70, and 80%; and flow rate 0.8, 1, and 1.2 mL/min; and buffer 10, 15, and 20 mM

To identify the optimal conditions, a numerical optimization was conducted using a desirability function approach, setting the goals listed in Table 2. The optimal chromatographic conditions, 60% organic phase, 16 mM buffer concentration, and flow rate of 0.8 mL/min, yielded the highest desirability value of 0.865. This optimal setting is visually represented within the design space overlay plot (Figure S2).

The experimental validation of the model was performed under five different HPLC conditions, including an optimized setting. As shown in Table S2, the observed values closely matched the predicted values, with percentage prediction errors mostly within 15%, confirming the accuracy and robustness of the models.

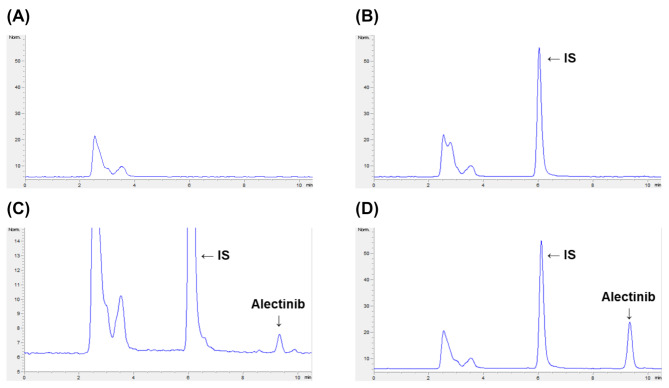

Selectivity and sensitivity

The developed method exhibited excellent selectivity, with no observable interference from endogenous plasma components at the retention times of alectinib (9.3 min) and the IS (ponatinib, 6.1 min), as shown in the representative chromatograms (Fig. 4). The LLOQ was 5 ng/mL, which met the regulatory criteria for accuracy and precision across six replicates in three validation runs (Table 4). Analyses of blank plasma, plasma spiked with only IS, and plasma samples containing alectinib at the LLOQ (5 ng/mL), as well as post-dosing plasma from rats administered 10 mg/kg alectinib, all showed distinct and interference-free peaks. These results demonstrate the high sensitivity and capability of this analytical method to reliably detect low concentrations of alectinib in rat plasma.

Fig. 4.

Representative chromatograms of alectinib and the internal standard (IS; ponatinib). (A) Blank rat plasma; (B) blank rat plasma spiked with the IS (100 ng/mL); (C) LLOQ (5 ng/mL) sample in rat plasma; (D) rat plasma sample collected at 1 h after oral administration of ponatinib at a dose of 10 mg/kg to rats

Table 4.

Inter- and intra-day accuracy and precision of alectinib quantification in rat plasma

| QC | Nominal concentration (ng/mL) | Measured concentration (ng/mL; mean ± SD) |

Accuracy (%)a | Precision (RSD, %)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-day | LLOQ | 5 | 4.87 ± 0.53 | 97.4 | 10.9 |

| LQC | 15 | 14.3 ± 1.0 | 95.6 | 7.46 | |

| MQC | 100 | 95.8 ± 6.9 | 95.8 | 7.21 | |

| HQC | 800 | 808 ± 54 | 102 | 6.66 | |

| Intra-day | LLOQ | 5 | 4.82 ± 0.53 | 96.0 | 10.5 |

| LQC | 15 | 14.7 ± 1.2 | 98.0 | 8.36 | |

| MQC | 100 | 97.0 ± 10.5 | 97.1 | 10.8 | |

| HQC | 800 | 812 ± 46 | 101 | 5.64 |

a Accuracy was calculated by measured concentration/nominal concentration × 100%

b Precision, expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD), was calculated as the standard deviation of the concentration/mean concentration × 100%

Linearity

This method demonstrated excellent linearity over a concentration range of 5–1,000 ng/mL in rat plasma. The regression equation of the representative calibration curve was y = 0.079x + 0.00990, where y is the peak area ratio of alectinib to the IS and x is the analyte concentration. The R² exceeded 0.99 in all analytical runs, indicating a strong linear correlation between the concentration and detector response. Additionally, more than 75% of calibration standards in each run satisfied the guideline criteria, with deviations within ± 15% of the nominal concentrations, and within ± 20% for the LLOQ. These results confirmed the linear and reliable quantification of alectinib in rat plasma over a wide concentration range.

Accuracy and precision

As summarized in Table 4, both intra- and inter-day accuracy and precision were within the acceptable limits across all QC levels. The method demonstrated excellent accuracy, ranging from 95.6 to 102%, and high precision, expressed as RSD, ranging from 5.64 to 10.9%. At the LLOQ (5 ng/mL), the accuracies were 97.4% (inter-day) and 96.0% (intra-day), with an RSD below 11%, satisfying the predefined acceptance criteria.

Recovery and matrix effect

The recovery and matrix effects of the analytical methods are presented in Table 5. The mean recovery of alectinib was consistent and reproducible across low (LQC), medium (MQC), and high (HQC) concentrations, ranging from 98.3 to 105% with low standard deviations, indicating high extraction efficiency. The IS, ponatinib, showed a recovery of 98.6 ± 2.1%. Matrix effects were minimal, with values between 86.1% and 89.6% for alectinib, and 92.1 ± 4.6% for the IS, confirming negligible suppression or enhancement by the matrix.

Table 5.

Recovery and matrix effect of alectinib and the internal standard (ponatinib) in rat plasma (mean ± SD, n = 5)

| Alectinib | Internal standard (ponatinib) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQC (15 ng/mL) | MQC (100 ng/mL) | HQC (800 ng/mL) | 100 ng/mL | |

| Recovery (%)a | 105 ± 3 | 104 ± 7 | 98.3 ± 5.3 | 98.6 ± 2.1 |

| Matrix effect (%)b | 87.5 ± 9.3 | 89.6 ± 8.9 | 86.1 ± 8.2 | 92.1 ± 4.6 |

a Matrix effect (%) = peak area of analyte-added post-precipitation/peak area of analyte in neat analyte solution × 100

b Recovery (%) = analyte peak area of an analyte added before precipitation/peak area of an analyte added after precipitation × 100

Stability test

Alectinib was stable under all the tested conditions (Table 6). Bench-top stability for 2 h at room temperature showed recoveries of 110 ± 10% (LQC) and 109 ± 2% (HQC). Long-term storage stability at − 20 °C for 3 weeks maintained over 104–110% recovery. After three freeze-thaw cycles, the drug remained stable with a recovery of 87.3 ± 9.5% (LQC) and 100 ± 6% (HQC). Post-preparation stability at 10 °C for 24 h also showed acceptable stability (> 93%), indicating sample integrity during typical analytical procedures.

Table 6.

Stability of alectinib in rat plasma (mean ± SD, n = 3)

| Storage condition | Stability (%, mean ± SD)a | |

|---|---|---|

| LQC (15 ng/mL) | HQC (800 ng/mL) | |

| Bench top (room temperature for 2 h) | 110 ± 10 | 109 ± 2 |

| Long term (-20 °C for 3 weeks) | 104 ± 9 | 110 ± 6 |

| Freeze-thaw (3 cycles) | 87.3 ± 9.5 | 100 ± 6 |

| Post-preparation stability (10 °C for 24 h) | 93.8 ± 6.4 | 95.7 ± 3.4 |

a Stability (%) = measured concentration after the designated storage condition/nominal concentration × 100

Dilution integrity and carryover

Dilution integrity was confirmed by analyzing the plasma samples spiked with alectinib at a concentration 10 times higher than the HQC level, followed by a 10-fold dilution using a blank matrix. The diluted samples yielded an accuracy of 89.1% and RSD of 5.7%, indicating that the method remained reliable and precise even after dilution. The peak areas of alectinib and the IS in the blank samples were less than 20% and 5% of those at the LLOQ, respectively, implying that the carryover effect of this analytical method was negligible.

Pharmacokinetic study of alectinib in rats

The validated analytical method was successfully applied in a pharmacokinetic study of alectinib in rats. Alectinib was administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg via both the intravenous and oral routes, and plasma samples were collected at designated time points. All the analytical runs met the bioanalytical method validation criteria outlined in the US FDA and EMA guidelines. More than 67% of the QC samples and over 50% of the QC samples at each concentration level were within 15% of their nominal values, confirming acceptable accuracy and precision across the runs. For samples exceeding the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ), a 10-fold dilution was performed using a blank plasma matrix to bring the concentrations within the validated calibration range.

After IV administration, alectinib exhibited a rapid decline in plasma concentration, suggesting first-order elimination kinetics. The initial plasma concentration (C₀) was 8,390 ± 160 ng/mL, and the t1/2 was determined to be 6.15 ± 0.08 h. The AUCinf reached 31,100 ± 800 ng·h/mL, indicating extensive systemic exposure. The calculated CL was 129 ± 3 mL/h/kg, and the Vss was 1,010 ± 20 mL/kg (Table 7; Fig. 5A).

Table 7.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of alectinib after intravenous or oral administration to rats (mean ± SD, n = 3)

| Parameter | PO (10 mg/kg) | IV (10 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| C0 (ng/mL) | - | 8,390 ± 160 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 224 ± 1 | - |

| Tmax (h) | 3 ± 0 | - |

| T1/2 (h) | 10.2 ± 0.1 | 6.15 ± 0.08 |

| AUClast (ng∙h/mL) | 4,040 ± 20 | 31,000 ± 800 |

| AUCinf (ng∙h/mL) | 4,200 ± 10 | 31,100 ± 800 |

| CL (mL/h/kg) | - | 129 ± 3 |

| Vss (mL/kg) | - | 1,010 ± 20 |

| Bioavailability (%) | 13.5 ± 0.3 | - |

a Calculated using the dose-normalized AUCPO / dose-normalized AUCIV × 100

AUC, area under the plasma concentration-time curve; CL, total clearance; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; MRT, mean residence time; SD, standard deviation; T1/2, terminal half-life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; Vss, steady-state volume of distribution

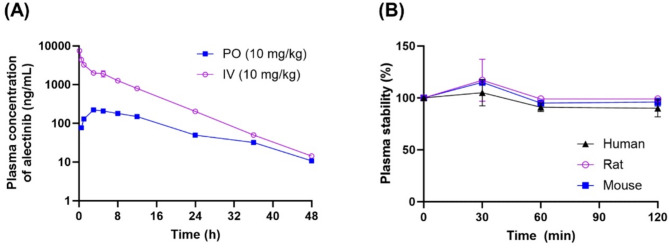

Fig. 5.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of alectinib. (A) Plasm concentration-time curve of alectinib after intravenous (IV, 10 mg/kg; purple open circles) or oral administration (PO, 10 mg/kg; blue closed squares) to rats. (B) Plasma stability of alectinib in humans (black closed triangles), rats (purple open circles), and mice (blue closed squares). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 for each group)

Following oral administration, alectinib was absorbed slowly, reaching a maximum plasma concentration of 224 ± 1 ng/mL at 3.0 h. The t1/2 was 10.2 ± 0.1 h, slightly longer than that observed after IV administration, possibly reflecting absorption-rate limitations. The AUCinf after oral dosing was 4,200 ± 10 ng·h/mL, substantially lower than that of the IV group. Based on dose-normalized AUC comparisons, the absolute oral bioavailability of alectinib was calculated to be 13.5 ± 0.3%, indicating limited systemic availability when administered orally.

In vitro plasma stability studies revealed that alectinib remained stable for up to 2 h at 37 °C in mouse, rat, and human plasma. These findings suggest that the degradation of alectinib in the plasma is minimal under physiological conditions and is unlikely to significantly contribute to its overall elimination in vivo (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

In this study, a robust and selective HPLC method for alectinib quantification in rat plasma was developed and validated. The development of the analytical method followed a QbD approach, incorporating comprehensive risk assessment and multivariate optimization to ensure high performance, regulatory compliance, and scientific soundness. Through a detailed FMEA, CMPs such as the organic phase ratio, buffer concentration, and flow rate were identified as having a significant impact on key chromatographic responses. Subsequent optimization using BBD enabled a comprehensive understanding of both the individual and interactive effects of these parameters, leading to a well-characterized and robust design space. Among the CMPs, the organic phase ratio emerged as the most influential factor affecting all CAAs, including the retention time, theoretical plate number, and peak area. Additionally, the presence of negative quadratic coefficients for buffer concentration and flow rate in the regression models indicated nonlinear relationships, underscoring the importance of carefully controlled optimization to avoid suboptimal sensitivity and resolution. These findings highlight the value of a multidimensional experimental design over traditional univariate approaches in achieving a stable and reliable chromatographic system suitable for use in complex bioanalytical workflows.

This study also highlights the thoughtful adaptation of QbD principles to specific challenges in the development of bioanalytical methods. Unlike traditional QbD applications that primarily focus on instrumental parameters and synthetic active pharmaceutical ingredients or drug products, this study extended QbD to the biological matrix context, where additional variables such as matrix complexity, sample pretreatment, and analyte stability are critical for achieving regulatory-acceptable performance. Bioanalytical methods must address a wide dynamic range, very low detection limits, and potential interference from endogenous substances, making their optimization inherently complex. In this study, matrix-related factors and extraction efficiency were incorporated into the risk assessment, and the experimental design accounted for potential interaction effects among the parameters. Method validation included not only traditional accuracy and precision, but also matrix effects, recovery, dilution integrity, and incurred sample stability. The integrative QbD-based strategy ultimately led to the development of a reliable, reproducible, and regulatory-compliant method that was well suited for the preclinical pharmacokinetic evaluation of alectinib.

Several analytical methods have been reported for the quantification of alectinib, primarily LC coupled with UV, photodiode arrays (PDA), and MS/MS detection. Although each approach has its merits, they differ considerably in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, operational complexity, and applicability to routine settings. UV- and PDA-based HPLC methods are favored because of their simplicity and accessibility, particularly for routine QC or formulation stability testing. For example, Kumar et al. developed a PDA-based method for quantifying alectinib in bulk drug and pharmaceutical formulations, achieving adequate linearity and selectivity, but with limited sensitivity (LLOQ 70 ng/mL) [25]. Similarly, Lee et al. reported a stability-indicating LC-PDA method that was successfully applied to drug degradation studies but was not suited for plasma-level detection owing to matrix interference and inadequate sensitivity in biological samples (LLOQ 100 ng/mL) [18]. In contrast, LC-MS/MS is the gold standard for bioanalysis because of its superior sensitivity and specificity. Multiple studies have reported LLOQs as low as 1 ng/mL for alectinib in the plasma using electrospray ionization and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [17]. However, the advantages of LC-MS/MS come at the cost of expensive instrumentation, high maintenance demands, and susceptibility to matrix effects. Additionally, sample preparation typically involves complex procedures such as liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) to minimize matrix effects and enhance sensitivity [26]. These techniques, which are effective for improving signal-to-noise ratios, are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often require specialized cartridges or large volumes of organic solvents, thereby increasing costs, reducing throughput, and limiting their routine use in resource-limited laboratories or high-throughput environments. The HPLC-FLD method developed in this study offers a compelling middle ground between simplicity and sensitivity. The use of the FLD allowed for the selective and sensitive quantification of alectinib with an LLOQ of 5 ng/mL, which is sufficient for non-clinical pharmacokinetic studies. Compared to PDA- or UV-based methods, FLD significantly reduced baseline noise and enhanced peak discrimination, even in complex plasma matrices. Furthermore, the method relied on a straightforward one-step protein precipitation procedure using acetonitrile containing the IS, without the need for reconstitution, evaporation, or derivatization. This not only minimized the analysis time but also improved reproducibility and sample integrity. Importantly, the method was rigorously validated according to FDA and EMA guidelines, demonstrating excellent linearity (R² >0.99), accuracy (95.6–102%), precision (RSD < 11%), high recovery (98.3–105%), minimal matrix effects (86–90%), and confirmed stability under various conditions. The successful application of this method in the pharmacokinetic study of alectinib in rats, covering both the intravenous and oral routes, further supports its reliability and practicality. Thus, although LC-MS/MS remains the preferred option when ultratrace detection is essential, the HPLC-FLD method described in this study provides a highly effective, reproducible, and cost-efficient alternative. Its balance of sensitivity, operational ease, and regulatory compliance makes it particularly valuable for preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetic studies and routine bioanalytical applications without access to MS.

In this study, the developed and validated HPLC-FLD method was successfully applied to the pharmacokinetic study of alectinib in rats. Rats are widely used in preclinical studies not only for the development of novel therapeutic agents but also for investigating additional mechanisms of action, toxicity profiles, and potential indications of already marketed drugs. One of the practical advantages of using rats in PK studies is the relatively large volume of blood that can be collected compared to mice, allowing for detailed time-course plasma concentration profiling. Compared to the study by Huang et al. [17], our study showed less than a 1.5-fold difference in systemic exposure at the same dose (10 mg/kg) after oral administration and a comparable t1/2. However, a shorter Tmax was observed in our study (3.0 h vs. 7.33 h), likely resulting from the use of a fully solubilized formulation as opposed to a suspension in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) in the study by Huang et al. Given that alectinib is classified as a Biopharmaceutics Classification System Class IV drug with low solubility and permeability, the formulation plays a critical role in its absorption profile.

In this study, we used a 10 mg/kg dose of alectinib in rats, which was significantly lower than the human equivalent dose (~ 50 mg/kg) when normalized to body surface area. This design allowed us to evaluate the sensitivity and applicability of the developed method at the subtherapeutic level. The method performed reliably at this low dose with excellent reproducibility and minimal matrix interference. Moreover, the validated dilution integrity of the method supports its use at higher doses through simple sample dilution without compromising accuracy or precision. Given the minimal matrix effects observed during validation, this method may also be adaptable to biological matrices other than plasma, including tissue homogenates and other species. This flexibility further enhances the utility of the developed method for diverse pharmacokinetic and toxicological studies.

In conclusion, the integration of risk-based method development, multivariate statistical optimization, and comprehensive validation resulted in a highly effective analytical platform for alectinib quantification in preclinical models. The balance of sensitivity, simplicity, and robustness of this method offers a practical alternative to LC-MS/MS and fills a critical methodological gap in non-clinical research. As a cost-effective and efficient tool, the HPLC-FLD method is well positioned to support ongoing pharmacokinetic investigations, formulation development, and exploratory studies aimed at expanding the clinical utility of alectinib.

Conclusion

A fluorescence-based HPLC method for quantifying alectinib in rat plasma was successfully developed and validated using AQbD. The CMPs were identified through FMEA and optimized via BBD, resulting in a robust and reliable method with excellent linearity, sensitivity, accuracy, and precision. This simple sample preparation method, minimal matrix effects, and validated stability support its application in preclinical pharmacokinetic studies. Its successful use in a rat pharmacokinetic study confirmed its suitability for the evaluation of formulation effects and systemic exposure. This study demonstrates the effective integration of AQbD principles into bioanalytical method development and offers a practical, regulatory-compliant alternative to LC-MS/MS for alectinib quantification.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Eun Ji Lee: Investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and writing of the original manuscript draft. Nahyun Koo: Investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and writing of the original manuscript draft. Min Ju Kim: Investigation, data curation, and writing of the original manuscript draft. Kyeong-Ryoon Lee: Conceptualization, methodology, writing - review, and supervision. Yoon-Jee Chae: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing - review, and supervision.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1A3056261), a grant from the KRIBB Research Initiative Program, and a grant from the Korea Machine Learning Ledger Orchestration for Drug Discovery Project (K-MELLODDY), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00459727).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All in vivo studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (approval no. KRIBB-AEC-25005).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Eun Ji Lee and Nahyun Koo contributed equally to this work.

Change history

12/17/2025

The original online version of this article was revised: The grant number in Funding section has been corrected.

References

- 1.Drug label of alectinib. Food and Drug Administration of United States. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/208434s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2025.

- 2.Drug label of alectinib. Food and Drug Administration of United States. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/208434s015lbl.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2025.

- 3.Mok T, Camidge DR, Gadgeel SM, Rosell R, Dziadziuszko R, Kim D-W, et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1056–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solange P, Ross CD, SA T, Shirish G, AJ S, Dong-Wan K, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025;377:829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotta K, Hida T, Nokihara H, Morise M, Kim YH, Azuma K et al. Final overall survival analysis from the phase III J-ALEX study of alectinib versus crizotinib in ALK inhibitor-naïve Japanese patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2022;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Summary of Product Characteristics for Alectinib. European Medicines Agency. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/alecensa-epar-product-information_en.pdf#page=2.14. Accessed 10 Apr 2025.

- 7.Yi-Long W, Rafal D, Seok AJ, Fabrice B, Makoto N, Ho LD, et al. Alectinib in resected ALK-positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1265–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukano R, Mori T, Sekimizu M, Choi I, Kada A, Saito AM, et al. Alectinib for relapsed or refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma: an open-label phase II trial. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:4540–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunga CGG, Higgins MS, Ricciotti RW, Liu YJ, Cranmer LD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the mesentery with a SQSTM1::ALK fusion responding to alectinib. Cancer Rep. 2023;6:e1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakoda S, Tanaka K, Koga Y, Mikumo H, Tsuchiya-Kawano Y, Harada E, et al. A case of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor harboring fusion with a brain metastasis responding to alectinib. Thorac Cancer. 2024;15:415–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe S, Sakai K, Matsumoto N, Koshio J, Ishida A, Abe T et al. Phase II trial of the combination of alectinib with bevacizumab in alectinib refractory ALK-positive nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NLCTG1501). Cancers. 2023;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kawasoe K, Watanabe T, Yoshida-Sakai N, Yamamoto Y, Kurahashi Y, Kidoguchi K et al. A combination of alectinib and DNA-demethylating agents synergistically inhibits anaplastic-lymphoma-kinase-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma cell proliferation. Cancers. 2023;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Morcos PN, Li Y, Katrijn B, Mika S, Hisakazu K, Kosuke K, et al. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of the ALK inhibitor alectinib: results from an absolute bioavailability and mass balance study in healthy subjects. Xenobiotica. 2017;47:217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morcos PN, Guerini E, Parrott N, Dall G, Blotner S, Bogman K, et al. Effect of food and esomeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of alectinib, a highly selective ALK inhibitor, in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6:388–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato-Nakai M, Kawashima K, Nakagawa T, Tachibana Y, Yoshida M, Takanashi K, et al. Metabolites of alectinib in human: their identification and pharmacological activity. Heliyon. 2017;3:e00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinig K, Herzog D, Ferrari L, Fraier D, Miya K, Morcos PN. LC-MS/MS determination of alectinib and its major human metabolite M4 in human urine: prevention of nonspecific binding. Bioanalysis. 2017;9:459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang X-X, Li Y-X, Li X-Y, Hu X-X, Tang P-F, Hu G-X. An UPLC-MS/MS method for the quantitation of alectinib in rat plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;132:227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Nath CE, Balzer BWR, Lewis CR, Trahair TN, Anazodo AC, et al. An HPLC–PDA method for determination of alectinib concentrations in the plasma of an adolescent. Acta Chromatogr Acta Chromatogr. 2020;32:166–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu LX, Amidon G, Khan MA, Hoag SW, Polli J, Raju GK, et al. Understanding pharmaceutical quality by design. AAPS J. 2014;16:771–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovács B, Péterfi O, Kovács-Deák B, Székely-Szentmiklósi I, Fülöp I, Bába L-I, et al. Quality-by-design in pharmaceutical development: from current perspectives to practical applications. Acta Pharm. 2021;71:497–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiarentin L, Gonçalves C, Augusto C, Miranda M, Cardoso C, Vitorino C. Drilling into quality by design approach for analytical methods. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2024;54:3478–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park G, Kim MK, Go SH, Choi M, Jang YP. Analytical quality by design (AQbD) Approach to the development of analytical procedures for medicinal plants. Plants (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Food and Drug Administration of United States. Bioanalytical method validation guidance for industry. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/70858/download. Accessed 7 Jun 2024.

- 24.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on bioanalytical method validation. 2011. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-bioanalytical-method-validation_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2024.

- 25.Kumar HK, Sahu SK, Debata J. A novel ultra performance liquid chromatography-PDA method development and validation for alectinib in bulk and its application to tablet dosage form. Int J Pharm Investig. 2020;10.

- 26.n der Heijden LT, Tibben MM, Mohmaed Ali MI, Aardenburg LGJ, Steeghs N, Beijnen JH, et al. An ultra-sensitive liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of 2H6-alectinib and alectinib in human plasma to support a microtracer food-effect trial. J Chromatogr B. 2025;1253:124488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.