ABSTRACT

Aim

The aim of this study is to determine the possible role of N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor (NMDAR) dysregulation in the ischemic electrical remodeling observed in patients with myocardial infarction (MI) and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Human heart tissue was obtained from the border of the infarct and remote zones of patients with ischemic heart disease, and mouse heart tissue was obtained from the peri‐infarct zone. NMDAR expression was detected using immunofluorescence (IF) and Western blotting (WB). Spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) in mice were detected using electrocardiogram backpacks. Electrical remodeling post‐MI was detected using patch clamp recordings, quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reactions, IF, and WB. Mechanistic studies were performed using bioinformatic analysis, plasmid and small interfering RNA transfection, lentiviral packaging, and site‐directed mutagenesis.

Results

NMDAR is highly expressed in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI. NMDAR inhibition reduces the occurrence of VAs. Mechanistically, NMDAR activation promotes electrophysiological remodeling, as characterized by decreased Nav1.5, Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 expression in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI and rescues these ion channels dysregulation in mice with MI to varying degrees by NMDAR inhibition. Decreased Nav1.5 expression and inward sodium current density were attenuated by NMDAR inhibition in primary rat cardiomyocytes. Moreover, NMDAR activation upregulates T‐Box Transcription Factor 3 (TBX3) post‐translationally, further downregulating Nav1.5 transcriptionally. Furthermore, AKT1 is the predominant isoform in the ventricular myocardium upstream of TBX3 and mediates NMDAR‐induced TBX3 upregulation in cardiomyocytes.

Conclusion

NMDAR activation contributes to MI‐induced VAs by regulating the AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 axis, providing novel therapeutic strategies for treating ischemic arrhythmias.

Keywords: electrophysiological remodeling, myocardial infarction, NMDAR, pseudo‐phosphorylation, ventricular arrhythmias

1. Introduction

Malignant ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) are common complications of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and a major cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) [1]. Early evidence suggests that patients with a severely low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) are at high risk of malignant VAs and SCD [2]. Fatal VAs in patients with ischemic heart disease have been shown to be independent of the degree of LVEF reduction [3]. Additionally, patients with an LVEF of 50% experience fatal arrhythmias, mainly due to ion channel remodeling and cardiac electrical abnormalities [3, 4].

Cardiac electrical remodeling in response to structural damage after MI involves changes in the inward sodium (Na+), outward potassium (K+), and inward calcium (Ca) currents [5]. These changes contribute to myocardial conduction disturbances and increase ventricular repolarization abnormalities, resulting in arrhythmias [6]. The alpha subunit of the cardiac voltage‐gated sodium channel, Nav1.5, is encoded by the sodium voltage‐gated channel alpha subunit 5 (SCN5A) and is crucial in cardiac conduction velocity [7] and arrhythmic risk [8]. Previous studies have shown that SCN5A expression is significantly reduced in ischemic hearts [9], and loss of function in Nav1.5 may be associated with arrhythmic storm development in patients with acute MI [10]. Therefore, reversing downregulation of Nav1.5 may reduce the risk of ischemic arrhythmias [11]. In addition, SCN5A mutations are associated with various arrhythmogenic diseases such as Brugada and long QT syndromes [12].

Of course, cardiac electrical disorders also include potassium channel abnormalities. Among them, there are two components of delayed rectifier currents: the rapid (IKr) and the slow (IKs) components. IKr moves through the α subunit pore Kv11.1, and IKs flows through the α subunit Kv7.1. Studies show that both IKr and IKs current densities were reduced in canine ventricular myocytes from infarcted hearts [13]. The downregulation of Kv4.3/Kv4.2 leads to a decrease in the density of the transient outward potassium current (Ito) in MI models [14]. Improving ischemia‐induced Kv4.3/Kv4.2 dysfunction can reduce the incidence of post‐MI VAs in mice [15]. The inward‐rectifier K current (IK1) contributes to the resting membrane potential, controls cardiac excitability, and modulates late‐phase repolarization and action potential duration in cardiac cells. Decreased IK1 and decreased expression of the principle underlying subunit potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel subfamily J member 2 (KCNJ2) messenger RNA (mRNA) and its encoded Kir2.1 protein are prominent features of ventricular electrical remodeling after MI [16]. Additionally, Cav1.2, a classical L‐type Ca2+ channel activated in the sarcolemma, forms excitation‐contraction couplings that affect the duration of action potential [17]. Downregulation of Cav1.2 in mice with MI results in early repolarization and increased susceptibility to arrhythmias [18, 19].

The N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are ligand‐gated voltage‐dependent ionotropic glutamate receptors at the cell–cell contact site. NMDARs are assembled as heteromers that differ in subunit composition. To date, seven different subunits have been identified, namely the GluN1 subunit (also known as NR1), four distinct GluN2 subunits (GluN2A, GluN2B, GluN2C, and GluN2D) and a pair of GluN3 (GluN3A and GluN3B) [20, 21]. Functional NMDARs require the assembly of two NR1 subunits together with two GluN2 subunits or a combination of GluN2 and GluN3 subunits. Activation of most NMDAR configurations requires binding of glutamate to GluN2 and co‐agonist, glycine, or D‐serine, to NR1 [20], leading to calcium ion overload and neuronal apoptosis [22]. Studies have demonstrated that NMDAR is associated with various neurological and psychiatric diseases. NMDAR antagonists are neuroprotective when administered before or shortly after traumatic brain injury or an ischemic insult in animal models [23, 24]. Inhibiting the GluN2B subunit‐containing NMDAR can reduce the gradual loss of synaptic function [25] and eventually lead to neuronal cell death [26], which is considered one of the underlying mechanisms of neurodegeneration in patients with AD. Furthermore, by interfering with the GluN2A subunit, synaptic localization reduces the percentage of rats with Parkinson's disease that develop dyskinetic movements [27]. In addition, altered glutamate signaling and abnormal NMDAR function may provide a pathological basis for the occurrence of schizophrenia [28], depression [29], autism [30], and other mental disorders [31, 32].

Recent studies have shown that NMDAR also exists in the cardiovascular system, mainly in atrial myocytes, ventricular myocytes, heart conduction systems, and vascular endothelium [33]. In a rat model of ischemia–reperfusion injury, NMDAR‐driven calcium influx potentiated adverse effects [34]. Furthermore, pharmacological NMDAR blockade in a monocrotaline rat model of pulmonary hypertension had beneficial effects on cardiac and vascular remodeling, decreasing endothelial dysfunction, cell proliferation, and apoptosis resistance while disrupting the NMDAR pathway in the pulmonary arteries [35]. Moreover, NMDAR inhibition attenuates cardiac remodeling, lipid peroxidation, and neutrophil recruitment in rats with heart failure [36]. Furthermore, accumulating evidence shows that it is closely associated with cardiac electrical activity and arrhythmias. In the atria of healthy rats, NMDAR activation reduces heart rate variability and increases susceptibility to atrial fibrillation [37]. Long‐term chronic activation of NMDAR downregulated the K+ channel protein of ventricular myocytes, accompanied by mild myocardial interstitial fibrosis, and promoted the occurrence of VAs [38]. In rat models of MI and ischemia–reperfusion, NMDAR activation induces ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation [39], which are effectively attenuated by the NMDAR‐specific inhibitor Dizocilpine (MK801, a non‐competitive NMDAR inhibitor) after ischemia–reperfusion [40]. NMDAR inhibition also reduces the Ca2+ load in the mitochondria [41] and induces antioxidant effects [39]. However, the mechanism underlying the role of NMDAR in post‐MI VAs remains unclear.

Therefore, we aimed to determine the possible role of NMDAR dysregulation in the ischemic electrical remodeling observed in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that NMDAR activation promotes ischemic arrhythmia by targeting the AKT1–T‐Box Transcription Factor 3 (TBX3)–Nav1.5 axis, highlighting NMDAR inhibition as a potential anti‐arrhythmic therapy for ischemic heart disease.

2. Results

2.1. Ischemic Myocardium Shows NMDAR Activation in Patients With Ischemic Heart Disease and Mice With MI

First, we investigated NMDAR expression and activation in the cardiomyocytes of patients with ischemic heart disease. The results showed that the NR1 and Ser‐896‐phosphorylated NR1 (p‐NR1) levels were higher at the border of the infarct zone than in the remote zone in patients with ischemic heart disease (Figure 1a,b,e). One week after left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) ligation in mice with MI, NR1 and p‐NR1 levels increased in the peri‐infarct zone compared with those in the corresponding region of the sham‐operated hearts. NR1 remained highly expressed and activated 2 weeks after MI (Figure 1c,d,f).

FIGURE 1.

The expression and activation of NMDAR in patients with ischemic heart disease and MI mice. (a) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot. (b) Quantitative analysis of (a). (c) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (d) Quantitative analysis of (c). (e) Levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in patients with ischemic heart disease measured using IF. (f) Levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in MI mice measured using IF. BIZ, The border of the infarct zone; IF, Immunofluorescence; MI, Myocardial infarction; NR1, N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor 1; RZ, The remote zone. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.2. NMDAR Inhibition Reduces Incidence of VAs After MI

To determine whether NMDAR activation is involved in MI‐induced VAs, we conducted another in vivo study, as shown in Figure 2a, in which MK801 was administered to mice with MI. First, the results verified that increased NR1 expression and activation levels in mice with MI were attenuated by MK801 (Figure S1a,b), indicating the potential role of NMDAR in MI cases. Furthermore, five of eight mice in the MI group and three of eight mice in the MI‐MK801 group showed spontaneous VAs (Figure 2b,c). No arrhythmias were observed in the sham group. Notably, one mouse in the MI group died during the electrocardiogram (ECG) tracing. ECG showed that the mouse first developed frequent ventricular fibrillation, with occasional effective ventricular contractions, followed by ventricular tachycardia, which lasted for approximately 13 s, after which the ventricle developed a spontaneous ventricular rhythm (Figure 2d). However, mice in the sham and MI‐MK801 groups did not die when the ECG was traced.

FIGURE 2.

NMDAR inhibition reduces the incidence of VAs after MI. (a) Schematic illustration of the procedure for in vivo study. (b, c) The number of ventricular arrhythmias (VT or VF) and representative traces recorded by ECG backpacks in mice of the sham, MI, and MI‐MK801 groups. (d) Representative ECG of VAs before death in 1 mouse in the MI group. (e) Representative M‐mode echocardiography images of the sham, MI, and MI‐MK801 groups. (f, g) Summary of LV ejection fraction and fractional shortening of mice from the sham, MI, and MI‐MK801 groups. (h) Correct LV mass of mice from the sham, MI, and MI‐MK801 groups. (i, j) Masson‐trichrome staining of the heart sections from each group. ECG, Electrocardiogram; ip, Intraperitoneal injection; LV, Left ventricular; VF, Ventricular fibrillation; VT, Ventricular tachycardia. Small sample size categorical data were expressed as percentages and analyzed using Fisher's exact test. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). One‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

In addition, echocardiography showed that LVEF and fractional shortening (LVFS) decreased in the MI group, which was attenuated by MK801 administration (Figure 2e–g). Furthermore, MK801 attenuated the MI‐induced increase in the LV mass (Figure 2h), and the collagen size of MK801‐treated mouse hearts reduced 2 weeks after MI compared with that of the MI group (Figure 2i,j).

2.3. NMDAR Inhibition Improves Ion Channel Dysregulation in Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

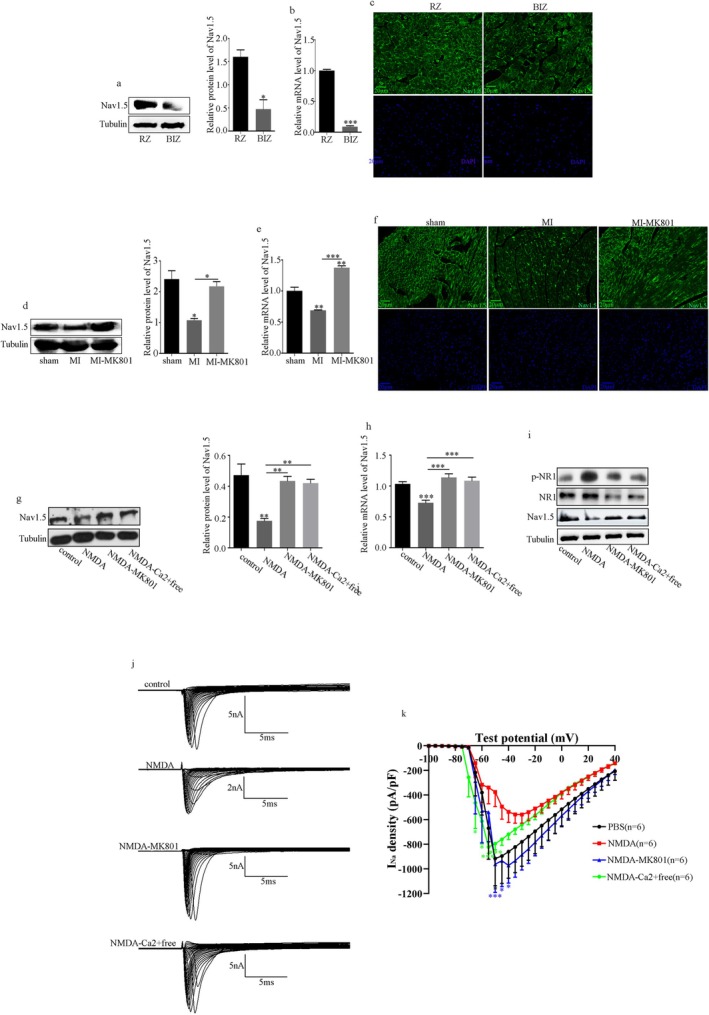

To further study the mechanisms underlying NMDAR regulation of MI‐induced VAs, we examined several major ion channels, Nav1.5, Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI. The results showed that Nav1.5 expression decreased at the border of the infarct zone compared with that at the border of the remote zone in patients with ischemic heart disease (Figure 3a–c). In mice with MI, Nav1.5 decreased and was intensively attenuated by MK801 (Figure 3d–f). The results also showed that Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 decreased in the hearts of patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI; however, the decrease in mice with MI was attenuated to varying degrees by MK801 (Figures S2 and S3).

FIGURE 3.

NMDAR inhibition improves Nav1.5 dysregulation in ventricular cardiomyocytes. (a) Protein levels of Nav1.5 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of Nav1.5 in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using RT‐PCR. (c) Levels of Nav1.5 in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using IF. (d) Protein levels of Nav1.5 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (e) Levels of Nav1.5 in MI mice evaluated using RT‐PCR. (f) Levels of Nav1.5 in MI mice evaluated using IF. (g) Protein levels of Nav1.5 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells evaluated using Western blot. (h) Levels of Nav1.5 in H9C2 cells evaluated using RT‐PCR. (i) Protein levels of Nav1.5, NR1, and p‐NR1 and quantitative analysis in primary rat cardiomyocytes. (j–k) The INa density in primary rat cardiomyocytes. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

To investigate the specific mechanism of NMDAR regulating VAs after MI through the Nav1.5 expression, cellular models of NMDAR activation in vitro have been studied. According to the results in Figure S4, H9C2 cells were treated with NMDA for 36 h (the optimum NMDA treatment time) to effectively activate NMDAR. This activation reduced Nav1.5, which was attenuated by MK801 or the removal of Ca2+ from the medium (Figure 3g,h).

Furthermore, we recorded the INa density in primary rat cardiomyocytes using whole‐cell patch‐clamp techniques. Figure 3i–k shows that Nav1.5 expression and the current densities of INa were reduced during NMDAR activation, in contrast to the control, MK801 administration, or removal of Ca2+ from the medium groups.

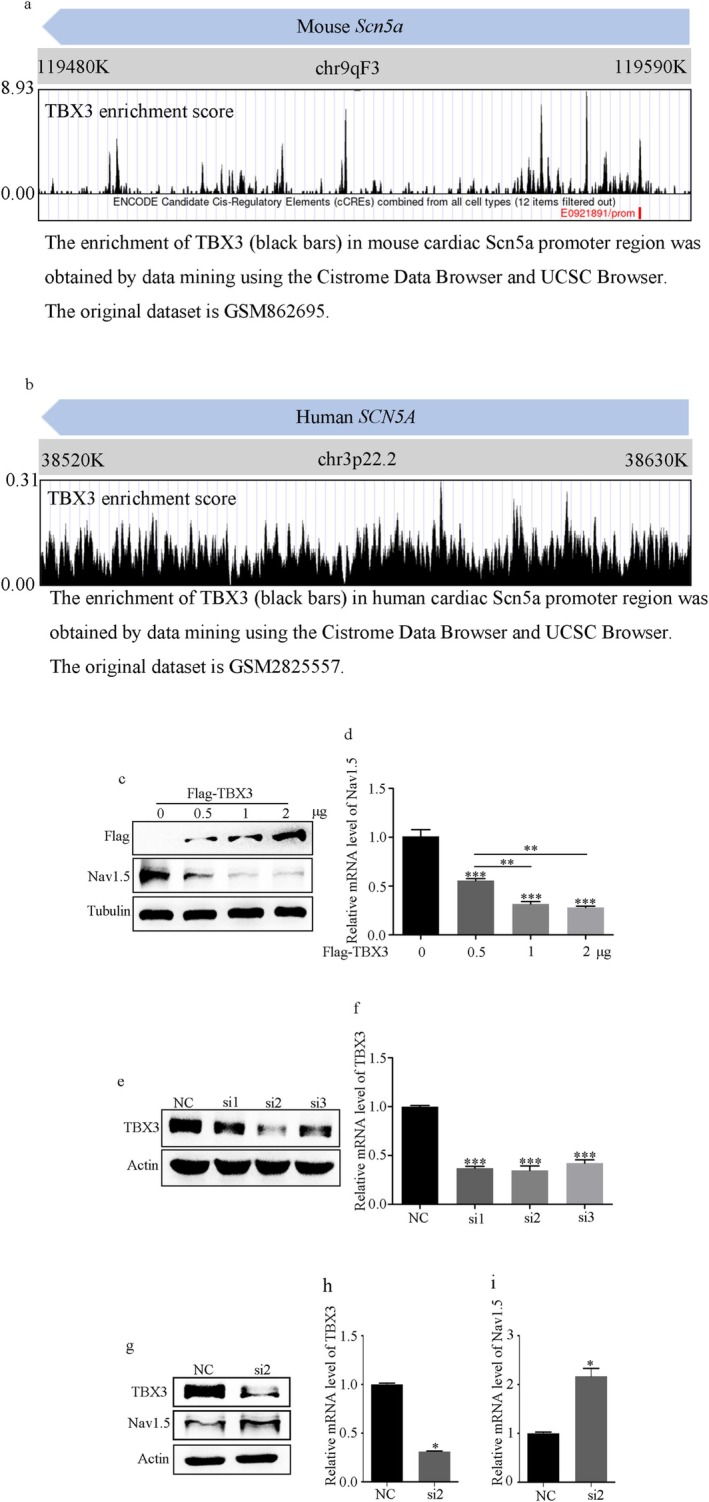

2.4. NMDAR Activation Inhibits Nav1.5 by Regulating TBX3 Post‐Translationally

Mechanistically, we screened for potential binding sites and confirmed the enrichment of TBX3 in the promoter regions of mouse and human SCN5A using the Cistrome Data and UCSC database (Figure 4a,b) [42, 43]. Furthermore, different amounts of porcine cytomegalovirus (pCMV)‐flag‐TBX3 were transfected, and the results showed that TBX3 overexpression inhibited the expression of Nav1.5 in H9C2 cells (Figure 4c,d). Conversely, TBX3 knockdown using the screened small interfering RNA with the best interference effect (Figure 4e,f) caused an increase in Nav1.5 (Figure 4g–i). We simultaneously validated the in vivo expression of TBX3. We found increased TBX3 protein levels in the peri‐infarct zone of patients with ischemic heart disease (Figure S5a) and mice with MI (Figure S5c), which MK801 attenuated. However, there was no difference in TBX3 mRNA levels in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI (Figure S5b,d). Additionally, in H9C2 cells, NMDAR activation upregulated the protein level rather than the mRNA level of TBX3, which was attenuated by MK801 or Ca2+ removal (Figure S5e–g).

FIGURE 4.

TBX3 was a negative controller of Scn5a transcription. (a, b) The enrichment of TBX3 in the mouse and human cardiac SCN5A promoter region was obtained by data mining using the Cistrome and UCSC databases. The original dataset is GSM862695 and GSM2825557. (c, d) Nav1.5 protein and mRNA levels overexpressed with different amounts of pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3 in H9C2 cells. (e, f) Screening of the best small interfering RNAs for TBX3 (si‐TBX3) using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (g–i) TBX3 knockdown caused an increase in both the mRNA and protein levels of Nav1.5. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

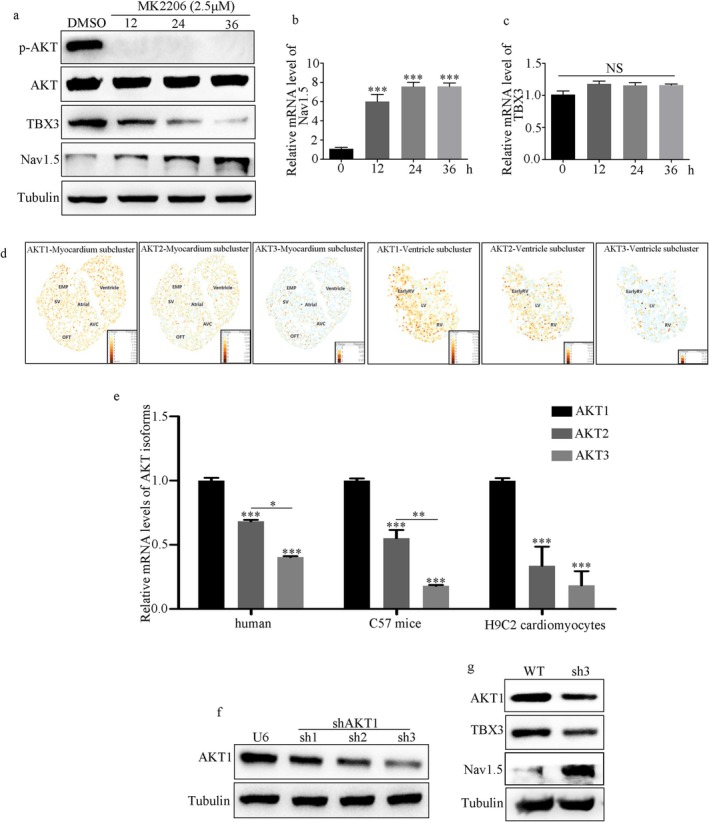

2.5. AKT1 Is the Predominant AKT Isoform in the Myocardium and Post‐Translationally Regulates TBX3

Firstly, H9C2 cardiomyocytes were treated with MK2206 at various time points. A significant decrease in p‐AKT and endogenous TBX3 protein levels compared with mRNA levels was observed at all tested time points, corresponding with increased endogenous Nav1.5 expression (Figure 5a–c). Furthermore, considering that there are three AKT isoforms (AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3), based on reported single‐cell transcriptome data [44, 45], AKT1 is the dominant isoform in the myocardium and ventricle subclusters during the development of mice (Figure 5d). Moreover, real‐time polymerase chain reaction was performed to verify that AKT3 was barely expressed and that AKT1 was the predominant isoform in human, mouse, and rat ventricular myocardia (Figure 5e). Finally, we depleted AKT1 with short hairpin RNAs that target the three prime untranslated region of AKT1 (Figure 5f). A decrease in TBX3 protein levels and an increase in Nav1.5 were observed in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells (Figure 5g).

FIGURE 5.

AKT1 is the predominant AKT isoform in myocardium and post‐translationally upregulates TBX3. (a) Protein levels of TBX3 and Nav1.5 in H9C2 cells treated with MK2206 at different time points. (b, c) mRNA levels of Nav1.5 and TBX3 in H9C2 cells treated with MK2206 at different time points. (d) Bioinformatics analysis based on the reported single‐cell transcriptome data. The original dataset is GSE126128. (e) qRT‐PCR analyses using primers specific to AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3 of human, mice, and H9C2 cells. (f) Screening of the best small hairpin RNAs for AKT1 (sh‐AKT1) using Western blot. (g) AKT1 knockdown caused a decrease in TBX3 protein level and an increase in Nav1.5 protein level. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

2.6. AKT1 Promotes TBX3 Protein Stability and Enhances Its Ability to Repress Nav1.5 by Pseudo‐Phosphorylation of TBX3 at Serine 720

To further determine how AKT1 modulates TBX3, we observed that MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, improved TBX3 protein levels in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells (Figure 6a). Furthermore, H9C2 and AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cardiomyocytes were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, a protein translation inhibitor) at different time points (0, 2, 4, and 6 h), and endogenous TBX3 was evaluated using Western blotting. The results showed that the stability of TBX3 decreased in AKT1‐silenced cells (Figure 6b,c).

FIGURE 6.

AKT1 promotes TBX3 protein stability and enhances its ability to repress Nav1.5 by pseudo‐phosphorylation of TBX3 at serine 720. (a) MG132, an inhibitor of the proteasome, rescued TBX3 protein levels in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells. (b, c) The decay rates of TBX3 protein level in both H9C2 cells and AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells were evaluated using Western blot. (d, e) AKT1 phosphorylation of TBX3 at serine 720 enhanced the ability to inhibit Nav1.5 in H9C2 cells, identified using Western blot and RT‐PCR. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). One‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Furthermore, H9C2 cells were transiently transfected with pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3, pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3‐S720A, and pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3‐S720E plasmids to test whether pseudo‐phosphorylation of TBX3 at serine 720 could affect its ability to repress Nav1.5. Compared with the control group, Nav1.5 expression decreased after pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3 and pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3‐S720E were overexpressed. Compared with the overexpression of pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3, Nav1.5 expression was reduced after the overexpression of pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3‐S720E and increased after the overexpression of pCMV‐Flag‐TBX3‐S720A (Figure 6d,e).

2.7. NMDAR Activation Promotes Post‐MI Arrhythmias Through AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 Axis

Based on these results, we hypothesized that NMDAR activation promotes post‐MI arrhythmia through the AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 axis. Primarily, our results showed that p‐AKT1 was increased at the border of the infarct zone compared with that at the remote zone in patients with ischemic heart disease (Figure 7a). The level of p‐AKT1 was elevated in mice with MI, which was attenuated by MK801 (Figure 7b). NMDAR activation consistently increased the expression of p‐AKT1 in H9C2 cells, which was attenuated by MK801 or Ca2+ removal (Figure 7c). Furthermore, p‐AKT1 was decreased following the inhibition of AKT phosphorylation by MK2206, and NMDAR activation failed to increase TBX3 or decrease Nav1.5 levels (Figure 7d). Moreover, NMDAR activation failed to promote TBX3 and decrease Nav1.5 in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells coherently (Figure 7e).

FIGURE 7.

NMDAR activation promotes post‐MI arrhythmias through the AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 axis. (a) Protein levels of p‐AKT1 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot. (b) Protein levels of p‐AKT1 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (c) Protein levels of p‐AKT1 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells evaluated using Western blot. (d) NMDAR activation failed to increase TBX3 expression and decrease Nav1.5 levels when inhibiting AKT1 phosphorylation. (e) NMDAR activation failed to promote the expression of TBX3 and decrease Nav1.5 levels in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

3. Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that NMDAR inhibition attenuates MI‐induced Nav1.5 reduction, preventing the incidence of VAs in post‐MI hearts by targeting the AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 axis. Therefore, our findings provide a new treatment strategy for ischemic VAs and suggest that NMDAR is a promising target for preventing VAs and SCD in patients with MI.

NMDARs are ion channels gated by the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and are widespread in the CNS as essential mediators of synaptic transmission and plasticity. Accumulating evidence shows the role of NMDAR in ischemic stroke [24], and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [46], Parkinson's disease [27], and Huntington's disease [47]. Besides, NMDAR is vital in schizophrenia [28], depression [29], epilepsy [48], and other mental disorders [31]. Studies have shown that NMDAR is also present in the cardiovascular system. Glutamate accumulation and NMDAR upregulation have been demonstrated in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension [35]. The functional subunit NR1 is found in all NMDAR subtypes, and the p‐NR1 regulates NMDAR activation [49]. In the present study, we demonstrated that the ischemic myocardium displayed high NR1‐subunit expression and activation in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI. NMDAR activation reduces heart rate variability and increases the susceptibility of the atria of healthy rats to atrial fibrillation [37]. In rat models of MI and ischemia–reperfusion, NMDAR activation induced ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation [39]. NMDAR inhibition consistently exerted anti‐arrhythmic effects on the post‐infarct ventricular myocardium, as shown by the spontaneous decrease in the incidence of VAs 2 weeks after MI. Our results indicate that NMDAR inhibition could protect cardiac function and myocardial fibrosis after MI.

Electrical remodeling of cardiac ion channels after MI contributes to myocardial conduction disturbances and increases ventricular repolarization dispersion, resulting in the development of arrhythmias [50]. Notably, several cardiac ion channels, such as Na, K, and Ca channels, participate in susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias after MI [17, 51, 52]. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that Nav1.5, Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 decreased in MI hearts [17, 53]. Dysfunction of intracellular Na channels is a critical predisposing factor for life‐threatening VAs [54]. Ikr inhibition leads to delayed ventricular repolarization and prolonged QT intervals, thus triggering fatal VA [55]. The functional expression of IKs channels decreases, leading to an increase in the duration of action potentials [56]. Improving the decreased expression of Ito, Iks, and Ikr can reduce the occurrence of VAs [17]. Decreased IK1 expression after MI leads to an increased action potential duration [19]. Cav1.2 participates in excitation‐contraction coupling and affects action potential duration [17, 18]. Our results also showed that the expression of Nav1.5 was significantly decreased in the hearts of patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI, which MK801 attenuated. In addition, we demonstrated that Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 decreased in the hearts of human patients with ischemic heart disease and MI mice, and they were attenuated by MK801 in MI mice to relatively moderate degrees, although the detailed mechanism remained unclear in this study.

Next, we investigated the mechanism of NMDAR regulating VAs after MI through the Nav1.5 expression. Therefore, it was activated or inhibited at the cellular level to study this potential mechanism. Notably, NMDAR is the main pathway of neuronal Ca2+ entry under the action of glutamate [57], which is temporarily compensated by Na/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX)‐mediated Ca2+ extrusion [58]. In neurons, NCX exhibits the highest transport capacity for Ca2+ [58]. In the forward mode, NCX catalyzes the extrusion of 1 Ca2+ to exchange 3 Na+, thus maintaining a low intracellular Ca2+ concentration [59]. However, NCX was reversed when the intracellular Na+ concentration increased [60]. In this case, the reverse operation of NCX (NCXrev) may continuously increase Ca2+, leading to delayed calcium dysregulation [61]. Therefore, we speculated that the effect of Ca2+ on NMDAR‐dependent arrhythmogenesis may also be crucial. In another subgroup, we removed Ca2+ from the external environment of the cells using a calcium‐free minimal essential medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum and then treated them with NMDA. Similarly, p‐NR1 and NR1 expression increased, whereas Nav1.5 and INa current density decreased after NMDA treatment, which was attenuated by MK801 or by removing Ca2+ from the medium. These results suggest that NMDAR regulates Nav1.5 expression and INa current density in ischemic cardiomyocytes, which may be a potential mechanism by which NMDAR regulates VAs after MI; however, the effect of Ca2+ on NMDAR‐dependent arrhythmogenesis should be considered.

Previous studies have demonstrated that T‐box factors belong to an ancient protein family and consist of a series of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors. They share a common DNA‐binding motif called the T‐box domain, which is critical in developing organs such as the heart and kidneys [62]. In the normal adult heart, TBX3 overexpression inhibits the expression of Gap junction protein alpha‐1, Gap junction protein alpha‐5, SCN5A, and natriuretic peptide precursor A, significantly reducing conduction velocity [63]. We screened for potential binding sites and confirmed the enrichment of TBX3 in the promoter regions of human [42] and mouse [43] SCN5A using the Cistrome and UCSC databases. Further results demonstrated that TBX3 negatively correlated with Nav1.5 expression in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. Notably, the protein level of TBX3 increased significantly in the peri‐infarct area of patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI and was attenuated by MK801 in mice with MI. However, there was no significant difference in the mRNA level of TBX3 in patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI. In H9C2 cardiomyocytes, NMDAR activation upregulated TBX3 protein levels rather than mRNA levels, which were attenuated by MK801 treatment or Ca2+ removal. Therefore, NMDAR activation inhibits Nav1.5 transcriptionally by regulating TBX3 post‐translationally.

Post‐translational modifications, including phosphorylation of transcription factors, are crucial in regulating gene expression because they can affect transcription factor target gene binding and regulation [64]. Previous studies have shown that TBX3 is a key substrate of AKT3 in the occurrence of melanoma, and pseudo‐phosphorylation at serine 720 promotes protein stability and enhances its ability to repress E‐cadherin in melanoma cells [65]. Pseudo‐phosphorylation of TBX3 at serine 720 enhances the activation of the collagen type I alpha 2 chain in fibrosarcoma and chondrosarcoma cells [66]. Therefore, although previous studies report that NMDAR activation mainly exerts downstream biological effects through the Ca2+/CAM/CaMKII/Ras and PI3K/AKT pathways [67, 68], we investigated whether NMDAR might regulate VAs after MI through the AKT‐TBX3 pathway. MK2206 was used to inhibit AKT phosphorylation at various time points. The results showed a sharp decrease in p‐AKT and endogenous TBX3 protein levels instead of mRNA levels at all tested time points, corresponding to an increase in endogenous Nav1.5 expression levels. Furthermore, considering that there are three AKT isoforms (AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3), we reanalyzed based on the reported single‐cell transcriptome data [44, 45]. The results illustrated that AKT1 is the dominant isoform in the myocardium and ventricle subclusters. We then verified that AKT1 is the dominant isoform in human, rat, and mouse ventricular myocardium and is a critical upstream regulator of TBX3. Similar to previous studies, we showed that TBX3 is post‐translationally modified by AKT1, likely through phosphorylation, increasing TBX3 protein stability. Furthermore, results showed that AKT1 regulates TBX3 through phosphorylation at serine 720, which enhances its ability to inhibit Nav1.5 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes.

These results were then validated in vivo. In patients with ischemic heart disease and mice with MI, p‐AKT1 was increased, which was attenuated by MK801 in mice with MI and H9C2 cells. Finally, MK2206 inhibition of AKT phosphorylation decreased p‐AKT1, and NMDAR activation failed to increase TBX3 expression and decrease Nav1.5 expression. Moreover, NMDAR activation failed to promote TBX3 expression and inhibit Nav1.5 expression in AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells, demonstrating that AKT1 mediated NMDAR‐induced TBX3 upregulation in ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Our study has some limitations. First, our early results showed that NMDAR also regulates K and Ca current in ischemic cardiomyocytes, which may be another potential mechanism through which NMDAR regulates VAs after MI. The specific mechanisms and ion channels that are mainly involved will be the focus of our follow‐up studies. Second, studies have proven that both NMDAR and NCXrev are critical contributors to delayed calcium dysregulation in neurons exposed to glutamate, and inhibiting both Ca2+ entry mechanisms is necessary [69]. However, the role of NCXrev in NMDA‐induced changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration remains unclear, and this is a vital research area for follow‐up studies. Third, we observed that AKT1 is the predominant form in ventricular myocytes. However, further investigation is required to determine whether AKT2 is involved in NMDAR‐induced TBX3 upregulation. Finally, we investigated NMDAR‐promoted electrical remodeling after MI. However, the role of NMDAR in structural remodeling and myocardial fibrosis after MI remains unclear.

In conclusion, our data revealed a novel AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 axis that may promote electrical remodeling after MI. These findings have critical implications for developing new therapeutic strategies for ischemic VAs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human Heart Tissue Samples

Human heart tissues were obtained from the failing hearts of patients with end‐stage ischemic heart disease (n = 7). Details of coronary angiography of patients were shown in Table S5. These samples were obtained from patients admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (reference number: 2021‐763). According to the coronary angiography results, tissues from the border of the infarct zone and the remote zone (the posterior wall of the left ventricle—close to the coronary sulcus) were selected.

4.2. Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (20–25 g) were housed under standard animal room conditions (temperature of 22°C ± 1°C, humidity of 55%–60%). First, we constructed a mouse model of MI at different time points. The animals were randomly divided into three groups: sham (n = 6), MI (1 week, n = 6), and MI (2 weeks, n = 6). The mice were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium. LAD ligation was performed as previously described. Sham group animals were subjected to the same procedures as the MI group, except for LAD ligation. ECGs were used to detect the presence of MI after 24 h of LAD ligation. MI was confirmed on the basis of ST‐segment elevation and T‐wave inversion on ECG lead II. Second, the animals were randomly divided into three groups: sham (n = 7), MI (2 weeks, n = 8), and MI‐MK801 (2 weeks, n = 8). The MI mice were randomized to receive MK801 (0.5 mg/kg) or DMSO by intraperitoneal injection once every day for 2 weeks 24 h after MI surgery. The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) and was approved by the Institution Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (reference number: 2021‐1405).

4.3. Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed by an investigator blinded to the study design using a Vevo 2100 system (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2%–4% isoflurane (MIDMARK, USA) using a gas chamber. Anesthesia was monitored by ensuring that the pedal withdrawal reflex was absent. Measurements were performed by an independent investigator.

4.4. ECG Testing

Two weeks later, the mice were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium. ECG backpacks were used to record the ECG of mice for 24 h in an awakened state. All ECG data were acquired using a multichannel electrophysiological recording system (Transonic Scisense Inc., London, ON, Canada). The definition of VAs is based on the Lambeth Convention II [70].

4.5. Plasmid Constructs

TBX3 was amplified and cloned into the pCMV‐Flag‐N vector (635 688; Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). All mutants of Flag‐TBX3 (Flag‐TBX3‐S720A, Flag‐TBX3‐S720E) were created by site‐specific mutation experiments.

4.6. Cell Cultures and Transfections

H9C2 and 293T cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (5.5 mM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2 and 95% air).

Transient knockdown of TBX3 expression was achieved by transfecting the cells with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that specifically targeted mRNA expression of TBX3. Briefly, H9C2 cells were plated at 7 × 104/well of a 12‐well plate and transfected with 50 nM siTBX3‐1 (Forward 5‐CAGAGAUGGUCAUUACGAATT‐3; Reverse 5‐UUCGUAAUGACCAUCUCUGTT‐3), 50 nM siTBX3‐2 (Forward 5‐GCUGAUGACUGUCGAUAUATT‐3; Reverse 5‐UAUAUCGACAGUCAUCAGCTT‐3), 50 nM siTBX3‐3 (Forward 5‐CUAUCAGAAUGACAAGAUATT‐3; Reverse 5‐UAUCUUGUCAUUCUGAUAGTT‐3), or a control siRNA (non‐silencing, si‐CON), using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen Life Technology,San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Overexpression of Flag‐TBX3 and the mutant forms (pCMV‐TBX3‐S720A, pCMV‐TBX3‐S720E) was achieved as follows: H9C2 cells were plated at 7 × 104/well of a 12‐well plate, and the next day transiently transfected with the above vectors or the pCMV‐Flag‐N vector using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen Life Technology, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

AKT1 knockdown was achieved by lentivirus‐mediated RNA interference.

Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting AKT1 (sh1‐AKT1: Forward 5′‐GATCC GCACCTTTATTGGCTACAAGGCAAGAGCCTTGTAGCCAATAAAGGTGC TTTTTG‐3′, Reverse 5′‐AATTCAAAAAGCACCTTTATTGGCTACAAGGCTCTTGCCTTGTAGCCAATAAAGGTGC G‐3′; sh2‐AKT1: Forward 5′‐GATCCGCACATCAAGATAACGGACTTCAAGAG AAGTCCGTTATCTTGATGTGCTTTTTG‐3′, Reverse 5′‐AATTCAAAAA GCACATCAAGATAACGGACTTCTCTTGAAGTCCGTTATCTTGATGTGCG‐3′; sh3‐AKT1: Forward 5′‐GATCCGCTGTTCGAGCTCATCCTAATCAAGAGATTAGGATGAGCTCGAACAGC TTTTTG‐3′, Reverse 5′‐AATTCAAAAAGCTGTTCGAGCTCATCCTAATCTCTTG ATTAGGATGAGCTCGAACAGCG‐3′), and negative‐control shRNA (sh‐CON) were designed and cloned into the lentivector pGreenPuro shRNA vector (SI505A‐1; System Biosciences, Pale Alto, CA, USA), and were then cotransfected with ViraPower lentiviral packaging mix (Thermo) into 293T cells to produce the lentivirus‐containing shAKT1 or sh‐CON. The H9C2 cells were then infected with the resultant lentiviruses and screened using puromycin (5 g/mL) (A1113803; Invitrogen) to obtain AKT1‐silenced cells. AKT1 knockdown was assessed using Western blot.

4.7. Treatments

The H9C2 cells were maintained as described previously [71]. NMDA (0.1 mM, Sigma, USA) and MK801 (30 μM, Sigma, USA) were used to activate and inhibit NMDAR, respectively. MK2206 (2.5 μM, GLPBIO, USA) was used to inhibit AKT kinase activity in the H9C2 cells. The H9C2 cells in the NMDA‐Ca2+‐free group were treated with the calcium‐free MEM medium containing 2% FBS. To inhibit ubiquitin‐mediated protein degradation, AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells were treated with MG132 (20 μM, Selleckchem, USA) for 16 h. The AKT1‐silenced H9C2 cells and H9C2 cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 20 μg/mL, GLPBIO, USA) to block de novo protein synthesis. The control cells were treated with DMSO.

4.8. Primary Rat Cardiomyocytes Culture

Primary rat cardiomyocytes were dissociated from 0‐ to 1‐day‐old SPF‐grade rat hearts. In brief, cardiomyocytes were isolated using a selective adherent technique after digestion with 0.25% trypsin solution. Cardiomyocytes were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C for 48 h.

4.9. Patch Clamp Recordings

Patch‐clamp recordings were obtained at room temperature (23°C–25°C). The EPC‐10 USB amplifier (HEKA Electronics, Germany) was connected to a computer running Patchmaster software (Heka, Germany). Offset potentials were nulled directly before the formation of a seal. No leak subtraction was made. Fast capacitance compensation was made after a high seal was achieved; membrane capacitance (in pF) compensation was made from whole‐cell capacitance compensation after the whole‐cell mode was achieved. Data were sampled at 20 kHz in voltage‐clamp mode. The tip resistance was in the range of 3–5 MΩ when the electrode was backfilled with internal solution. All data were analyzed offline using PatchMaster (Axon Instruments, USA), and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad, USA). Values are represented as either raw or normalized means±SEM, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. Two‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison was used to analyze significance between independent samples under multiple conditions. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to compare multiple independent groups.

4.10. Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described [71]. The primary antibodies used were NR1 (1:100, Abcam), p‐NR1 (1:50, Abcam), cTnT (1:100, Proteintech), Nav1.5 (1:200, Proteintech), Kv11.1 (1:200, Abcam), Kv4.2 (1:200, Proteintech), Kv7.1 (1:200, Abcam), Kir2.1 (1:200, Proteintech), Cav1.2 (1:200, Proteintech), and TBX3 (1:200, Abcam).

4.11. Quantitative Real‐Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the myocardial samples and cells using TRIzol reagent and an RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology [Dalian] Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). qRT–PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Biotechnology [Dalian] Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) and a Mastercycler EP realplex detection system (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Tables S2–S4 summarizes the primer sequences used in this study.

4.12. Western Blot

Heart tissues and cell proteins were prepared as previously described [71]. The primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit polyclonal anti‐NR1 (1:1000, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti‐p‐NR1 (1:1000, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti‐Nav1.5 (1:1000, Proteintech), rabbit monoclonal anti‐Kv11.1 (1:1000, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti‐Kv4.2 (1:1000, Proteintech), mouse monoclonal anti‐Kv7.1 (1:1000, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti‐Kir2.1 (1:1000, Proteintech), rabbit polyclonal anti‐Cav1.2 (1:1000, Proteintech), rabbit polyclonal anti‐TBX3 (1:1000, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti‐Flag M2 (1:1000, Sigma‐Aldrich), rabbit polyclonal AKT (1:1000, Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal p‐AKT (1:1000, Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal AKT1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal p‐AKT1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling), mouse polyclonal anti‐tubulin (1:1000, Proteintech), and mouse polyclonal anti‐actin (1:1000, Proteintech). The secondary antibodies, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse (1:5000, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and goat anti‐rabbit (1:5000, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), were used.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Data from three independent experiments are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Two‐tailed Student's t‐test was performed for comparison between two groups; one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. Small sample size categorical data were expressed as percentages and analyzed using Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Author Contributions

Lihong Wang, Liangrong Zheng, and Ling Xia: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. Yuxian He, Han Zhang, and Qinggang Zhang: investigation, methodology, validation, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. Zewei Sun: Investigation, writing the original draft. Xingang Sun: Investigation, writing – review and editing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Ischemic myocardium display of NMDAR activation in MI mice and attenuation by MK801. (a) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in MI mice measured using IF. (c) Electrocardiogram before and after surgery to induce myocardial infarction. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). One‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure S2: NMDAR inhibition improves Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 dysregulation in patients with ischemic heart disease. (a) Protein levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using IF.

Figure S3: NMDAR inhibition improves Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 dysregulation in MI mice. (a) Protein levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 in MI mice evaluated using IF.

Figure S4: Pre‐experiments of NMDAR activation and inhibition in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. (a) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells treated with NMDA for different time points in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. (b) NMDAR activation and inhibition in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. One‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure S5: NMDAR activation inhibits Nav1.5 by regulating TBX3 post‐translationally. (a, b) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (c, d) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (e, f) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (g) The level of TBX3 in H9C2 cells evaluated using IF. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). A two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and a one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Appendix S1: All western blots used to make the bar graphs in the document.

Table S1: Abbreviation.

Table S2: Primer sequences for humans.

Table S3: Primer sequences for mice.

Table S4: Primer sequences for rats.

Table S5: Demographic and basic clinical characteristics of patients involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81873484 and No. 82000316) and Guizhou Province Special Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ethnic Medicine Science and Technology (No. QZYY‐2024‐042).

He Y., Zhang H., Zhang Q., et al., “NMDA‐Type Glutamate Receptor Activation Promotes Ischemic Arrhythmias by Targeting the AKT1–TBX3–Nav1.5 Axis,” Acta Physiologica 241, no. 9 (2025): e70085, 10.1111/apha.70085.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81873484 and No. 82000316) and the Guizhou Province Special Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ethnic Medicine Science and Technology (No. QZYY‐2024‐042).

Yuxian He and Han Zhang contributed equally to this study.

Abbreviations: All abbreviations used in the document are organized in Table S1.

Contributor Information

Ling Xia, Email: xialing@zju.edu.cn.

Liangrong Zheng, Email: 1191066@zju.edu.cn.

Lihong Wang, Email: wanglhnew@126.com.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in Figure 4a,b of this study are openly available in [Cistrome DB] at http://cistrome.org/db/#/ [doi: 10.1038/nature11247; and doi: 10.1172/JCI62613], reference number [37, 38]. The data that support the findings in Figure 5d of this study are openly available in [The UCSC Cell Browser] at https://cells.ucsc.edu/ [doi: 10.1038/s41586‐019‐1414‐x; and doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab503], reference number [39, 40].

References

- 1. Myerburg R. J. and Junttila M. J., “Sudden Cardiac Death Caused by Coronary Heart Disease,” Circulation 125, no. 8 (2012): 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rouleau J. L., Talajic M., Sussex B., et al., “Myocardial Infarction Patients in the 1990s—Their Risk Factors, Stratification and Survival in Canada: The Canadian Assessment of Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Study,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 27, no. 5 (1996): 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pezawas T., Diedrich A., Robertson D., et al., “Risk of Arrhythmic Death in Ischemic Heart Disease: A Prospective, Controlled, Observer‐Blind Risk Stratification Over 10 Years,” European Journal of Clinical Investigation 47, no. 3 (2017): 231–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wasson S., Reddy H. K., and Dohrmann M. L., “Current Perspectives of Electrical Remodeling and Its Therapeutic Implications,” Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 9, no. 2 (2004): 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen T. P., Qu Z., and Weiss J. N., “Cardiac Fibrosis and Arrhythmogenesis: The Road to Repair Is Paved With Perils,” Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 70 (2014): 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyer C. and Scherschel K., “Ventricular Tachycardia in Ischemic Heart Disease: The Sympathetic Heart and Its Scars,” American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology 312, no. 3 (2017): H549–H551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kelly A., Salerno S., Connolly A., et al., “Normal Interventricular Differences in Tissue Architecture Underlie Right Ventricular Susceptibility to Conduction Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Brugada Syndrome,” Cardiovascular Research 114, no. 5 (2018): 724–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Remme C. A. and Bezzina C. R., “Sodium Channel (Dys)function and Cardiac Arrhythmias,” Cardiovascular Therapeutics 28, no. 5 (2010): 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kepenek E. S., Ozcinar E., Tuncay E., Akcali K. C., Akar A. R., and Turan B., “Differential Expression of Genes Participating in Cardiomyocyte Electrophysiological Remodeling via Membrane Ionic Mechanisms and Ca(2+)‐Handling in Human Heart Failure,” Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 463, no. 1–2 (2020): 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Han D., Tan H., Sun C., et al., “Dysfunctional Nav1.5 Channels due to SCN5A Mutations,” Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.) 243, no. 10 (2018): 852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang G. J., Xie A., Liu H., and S. C. Dudley, Jr. , “MIR448 Antagomir Reduces Arrhythmic Risk After Myocardial Infarction by Upregulating the Cardiac Sodium Channel,” JCI Insight 5, no. 23 (2020): e140759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veerman C. C., Wilde A. A., and Lodder E. M., “The Cardiac Sodium Channel Gene SCN5A and Its Gene Product NaV1.5: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology,” Gene 573, no. 2 (2015): 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang M., Cabo C., Yao J., et al., “Delayed Rectifier K Currents Have Reduced Amplitudes and Altered Kinetics in Myocytes From Infarcted Canine Ventricle,” Cardiovascular Research 48, no. 1 (2000): 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu M., Liu H., Parthiban P., et al., “Inhibition of the Unfolded Protein Response Reduces Arrhythmia Risk After Myocardial Infarction,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 131, no. 18 (2021): e147836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J., Ma Z. Y., Cui Y. F., et al., “Cardiac‐Specific Deletion of BRG1 Ameliorates Ventricular Arrhythmia in Mice With Myocardial Infarction,” Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 45, no. 3 (2024): 517–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li X., Chu W., Liu J., et al., “Antiarrhythmic Properties of Long‐Term Treatment With Matrine in Arrhythmic Rat Induced by Coronary Ligation,” Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 32, no. 9 (2009): 1521–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen T., Kong B., Shuai W., Gong Y., Zhang J., and Huang H., “Vericiguat Alleviates Ventricular Remodeling and Arrhythmias in Mouse Models of Myocardial Infarction via CaMKII Signaling,” Life Sciences 334 (2023): 122184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fo Y., Zhang C., Chen X., et al., “Chronic Sigma‐1 Receptor Activation Ameliorates Ventricular Remodeling and Decreases Susceptibility to Ventricular Arrhythmias After Myocardial Infarction in Rats,” European Journal of Pharmacology 889 (2020): 173614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu H., Jiang M., Cao Y., et al., “HuR Regulates Phospholamban Expression in Isoproterenol‐Induced Cardiac Remodelling,” Cardiovascular Research 116, no. 5 (2020): 944–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Traynelis S. F., Wollmuth L. P., Mcbain C. J., et al., “Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels: Structure, Regulation, and Function,” Pharmacological Reviews 62, no. 3 (2010): 405–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szychowski K. A., Wnuk A., Rzemieniec J., Kajta M., Leszczyńska T., and Wójtowicz A. K., “Triclosan‐Evoked Neurotoxicity Involves NMDAR Subunits With the Specific Role of GluN2A in Caspase‐3‐Dependent Apoptosis,” Molecular Neurobiology 56, no. 1 (2019): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim J. R., Lee H. J., Jung Y. H., et al., “Ethanol‐Activated CaMKII Signaling Induces Neuronal Apoptosis Through Drp1‐Mediated Excessive Mitochondrial Fission and JNK1‐Dependent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation,” Cell Communication and Signaling: CCS 18, no. 1 (2020): 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lai T. W., Shyu W. C., and Wang Y. T., “Stroke Intervention Pathways: NMDA Receptors and Beyond,” Trends in Molecular Medicine 17, no. 5 (2011): 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Camacho A. and Massieu L., “Role of Glutamate Transporters in the Clearance and Release of Glutamate During Ischemia and Its Relation to Neuronal Death,” Archives of Medical Research 37, no. 1 (2006): 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rönicke R., Mikhaylova M., Rönicke S., et al., “Early Neuronal Dysfunction by Amyloid β Oligomers Depends on Activation of NR2B‐Containing NMDA Receptors,” Neurobiology of Aging 32, no. 12 (2011): 2219–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ittner L. M., Ke Y. D., Delerue F., et al., “Dendritic Function of Tau Mediates Amyloid‐Beta Toxicity in Alzheimer's Disease Mouse Models,” Cell 142, no. 3 (2010): 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gardoni F., Sgobio C., Pendolino V., Calabresi P., Di Luca M., and Picconi B., “Targeting NR2A‐Containing NMDA Receptors Reduces L‐DOPA‐Induced Dyskinesias,” Neurobiology of Aging 33, no. 9 (2012): 2138–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ju P. and Cui D., “The Involvement of N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Receptor (NMDAR) Subunit NR1 in the Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia,” Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 48, no. 3 (2016): 209–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sadeghi M. A., Hemmati S., Mohammadi S., et al., “Chronically Altered NMDAR Signaling in Epilepsy Mediates Comorbid Depression,” Acta Neuropathologica Communications 9, no. 1 (2021): 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fan C., Gao Y., Liang G., et al., “Transcriptomics of Gabra4 Knockout Mice Reveals Common NMDAR Pathways Underlying Autism, Memory, and Epilepsy,” Molecular Autism 11, no. 1 (2020): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Q. W., Lu S. Y., Liu Y. N., et al., “Synaptotagmin‐7 Deficiency Induces Mania‐Like Behavioral Abnormalities Through Attenuating GluN2B Activity,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, no. 49 (2020): 31438–31447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolosker H. and Balu D. T., “D‐Serine as the Gatekeeper of NMDA Receptor Activity: Implications for the Pharmacologic Management of Anxiety Disorders,” Translational Psychiatry 10, no. 1 (2020): 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bozic M. and Valdivielso J. M., “The Potential of Targeting NMDA Receptors Outside the CNS,” Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 19, no. 3 (2015): 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Z. Y., Hu S., Zhong Q. W., Tian C. N., Ma H. M., and Yu J. J., “N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Receptor‐Driven Calcium Influx Potentiates the Adverse Effects of Myocardial Ischemia‐Reperfusion Injury Ex Vivo,” Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 70, no. 5 (2017): 329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dumas S. J., Bru‐Mercier G., Courboulin A., et al., “NMDA‐Type Glutamate Receptor Activation Promotes Vascular Remodeling and Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension,” Circulation 137, no. 22 (2018): 2371–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abbaszadeh S., Javidmehr A., Askari B., Janssen P. M. L., and Soraya H., “Memantine, an NMDA Receptor Antagonist, Attenuates Cardiac Remodeling, Lipid Peroxidation and Neutrophil Recruitment in Heart Failure: A Cardioprotective Agent?,” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 108 (2018): 1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi S., Liu T., Wang D., et al., “Activation of N‐Methyl‐d‐Aspartate Receptors Reduces Heart Rate Variability and Facilitates Atrial Fibrillation in Rats,” Europace 19, no. 7 (2017): 1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi S., Liu T., Li Y., et al., “Chronic N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Receptor Activation Induces Cardiac Electrical Remodeling and Increases Susceptibility to Ventricular Arrhythmias,” Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 37, no. 10 (2014): 1367–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Govoruskina N., Jakovljevic V., Zivkovic V., et al., “The Role of Cardiac N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Receptors in Heart Conditioning‐Effects on Heart Function and Oxidative Stress,” Biomolecules 10, no. 7 (2020): 1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lü J., Gao X., Gu J., et al., “Nerve Sprouting Contributes to Increased Severity of Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias by Upregulating iGluRs in Rats With Healed Myocardial Necrotic Injury,” Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 48, no. 2 (2012): 448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun X., Zhong J., Wang D., et al., “Increasing Glutamate Promotes Ischemia‐Reperfusion‐Induced Ventricular Arrhythmias in Rats In Vivo,” Pharmacology 93, no. 1–2 (2014): 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. ENCODE Project Consortium , “An Integrated Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in the Human Genome,” Nature 489, no. 7414 (2012): 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van den Boogaard M., Wong L. Y., Tessadori F., et al., “Genetic Variation in T‐Box Binding Element Functionally Affects SCN5A/SCN10A Enhancer,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 122, no. 7 (2012): 2519–2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Soysa T. Y., Ranade S. S., Okawa S., et al., “Single‐Cell Analysis of Cardiogenesis Reveals Basis for Organ‐Level Developmental Defects,” Nature 572, no. 7767 (2019): 120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Speir M. L., Bhaduri A., Markov N. S., et al., “UCSC Cell Browser: Visualize Your Single‐Cell Data,” Bioinformatics 37, no. 23 (2021): 4578–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parsons C. G., Stöffler A., and Danysz W., “Memantine: A NMDA Receptor Antagonist That Improves Memory by Restoration of Homeostasis in the Glutamatergic System—Too Little Activation Is Bad, Too Much Is Even Worse,” Neuropharmacology 53, no. 6 (2007): 699–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fan M. M. and Raymond L. A., “N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Function and Excitotoxicity in Huntington's Disease,” Progress in Neurobiology 81, no. 5–6 (2007): 272–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu X. X. and Luo J. H., “Mutations of N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Receptor Subunits in Epilepsy,” Neuroscience Bulletin 34, no. 3 (2018): 549–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu H., Bae M., Tovar‐Y‐Romo L. B., et al., “The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Coat Protein gp120 Promotes Forward Trafficking and Surface Clustering of NMDA Receptors in Membrane Microdomains,” Journal of Neuroscience 31, no. 47 (2011): 17074–17090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nattel S., Maguy A., Le Bouter S., et al., “Arrhythmogenic Ion‐Channel Remodeling in the Heart: Heart Failure, Myocardial Infarction, and Atrial Fibrillation,” Physiological Reviews 87, no. 2 (2007): 425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhai X., Qiao X., Zhang L., et al., “I(K1) Channel Agonist Zacopride Suppresses Ventricular Arrhythmias in Conscious Rats With Healing Myocardial Infarction,” Life Sciences 239 (2019): 117075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu Y., Li J., Xu N., et al., “Transcription Factor Meis1 Act as a New Regulator of Ischemic Arrhythmias in Mice,” Journal of Advanced Research 39 (2022): 275–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Abdelrady A. M., Zaitone S. A., Farag N. E., Fawzy M. S., and Moustafa Y. M., “Cardiotoxic Effect of Levofloxacin and Ciprofloxacin in Rats With/Without Acute Myocardial Infarction: Impact on Cardiac Rhythm and Cardiac Expression of Kv4.3, Kv1.2 and Nav1.5 Channels,” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 92 (2017): 196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wagner S., Maier L. S., and Bers D. M., “Role of Sodium and Calcium Dysregulation in Tachyarrhythmias in Sudden Cardiac Death,” Circulation Research 116, no. 12 (2015): 1956–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dong X., Liu Y., Niu H., et al., “Electrophysiological Characterization of a Small Molecule Activator on Human Ether‐a‐Go‐Go‐Related Gene (hERG) Potassium Channel,” Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 140, no. 3 (2019): 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gui Y., Li D., Chen J., et al., “Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitors, t‐AUCB, Downregulated miR‐133 in a Mouse Model of Myocardial Infarction,” Lipids in Health and Disease 17, no. 1 (2018): 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tymianski M., Charlton M. P., Carlen P. L., and Tator C. H., “Source Specificity of Early Calcium Neurotoxicity in Cultured Embryonic Spinal Neurons,” Journal of Neuroscience 13, no. 5 (1993): 2085–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Carafoli E., Santella L., Branca D., and Brini M., “Generation, Control, and Processing of Cellular Calcium Signals,” Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 36, no. 2 (2001): 107–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Blaustein M. P. and Lederer W. J., “Sodium/Calcium Exchange: Its Physiological Implications,” Physiological Reviews 79, no. 3 (1999): 763–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kiedrowski L., Brooker G., Costa E., and Wroblewski J. T., “Glutamate Impairs Neuronal Calcium Extrusion While Reducing Sodium Gradient,” Neuron 12, no. 2 (1994): 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kiedrowski L., “N‐Methyl‐D‐Aspartate Excitotoxicity: Relationships Among Plasma Membrane Potential, Na(+)/ca(2+) Exchange, Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Overload, and Cytoplasmic Concentrations of Ca(2+), H(+), and K(+),” Molecular Pharmacology 56, no. 3 (1999): 619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Naiche L. A., Harrelson Z., Kelly R. G., and Papaioannou V. E., “T‐Box Genes in Vertebrate Development,” Annual Review of Genetics 39 (2005): 219–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhao H., Wang F., Zhang W., et al., “Overexpression of TBX3 in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs) Increases Their Differentiation Into Cardiac Pacemaker‐Like Cells,” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 130 (2020): 110612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hunter T. and Karin M., “The Regulation of Transcription by Phosphorylation,” Cell 70, no. 3 (1992): 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peres J., Mowla S., and Prince S., “The T‐Box Transcription Factor, TBX3, Is a Key Substrate of AKT3 in Melanomagenesis,” Oncotarget 6, no. 3 (2015): 1821–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Omar R., Cooper A., Maranyane H. M., et al., “COL1A2 Is a TBX3 Target That Mediates Its Impact on Fibrosarcoma and Chondrosarcoma Cell Migration,” Cancer Letters 459 (2019): 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen H. J., Rojas‐Soto M., Oguni A., and Kennedy M. B., “A Synaptic Ras‐GTPase Activating Protein (p135 SynGAP) Inhibited by CaM Kinase II,” Neuron 20, no. 5 (1998): 895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yoshii A. and Constantine‐Paton M., “BDNF Induces Transport of PSD‐95 to Dendrites Through PI3K‐AKT Signaling After NMDA Receptor Activation,” Nature Neuroscience 10, no. 6 (2007): 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brittain M. K., Brustovetsky T., Sheets P. L., et al., “Delayed Calcium Dysregulation in Neurons Requires Both the NMDA Receptor and the Reverse Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger,” Neurobiology of Disease 46, no. 1 (2012): 109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Curtis M. J., Hancox J. C., Farkas A., et al., “The Lambeth Conventions (II): Guidelines for the Study of Animal and Human Ventricular and Supraventricular Arrhythmias,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics 139, no. 2 (2013): 213–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sun Z., Han J., Zhao W., et al., “TRPV1 Activation Exacerbates Hypoxia/Reoxygenation‐Induced Apoptosis in H9C2 Cells via Calcium Overload and Mitochondrial Dysfunction,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 10 (2014): 18362–18380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Ischemic myocardium display of NMDAR activation in MI mice and attenuation by MK801. (a) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 in MI mice measured using IF. (c) Electrocardiogram before and after surgery to induce myocardial infarction. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). One‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure S2: NMDAR inhibition improves Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 dysregulation in patients with ischemic heart disease. (a) Protein levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using IF.

Figure S3: NMDAR inhibition improves Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 dysregulation in MI mice. (a) Protein levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot. (b) Levels of Kv11.1, Kv4.2, Kv7.1, Kir2.1, and Cav1.2 in MI mice evaluated using IF.

Figure S4: Pre‐experiments of NMDAR activation and inhibition in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. (a) Protein levels of NR1 and phosphorylated‐NR1 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells treated with NMDA for different time points in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. (b) NMDAR activation and inhibition in cultured ventricular myocyte H9C2 cells. One‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure S5: NMDAR activation inhibits Nav1.5 by regulating TBX3 post‐translationally. (a, b) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in patients with ischemic heart disease evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (c, d) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in MI mice evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (e, f) The level of TBX3 and quantitative analysis in H9C2 cells evaluated using Western blot and RT‐PCR. (g) The level of TBX3 in H9C2 cells evaluated using IF. Data from three independent repetitions of experiments are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). A two‐tailed Student's t test was performed for comparison between two groups, and a one‐way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was used to compare the data from multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Appendix S1: All western blots used to make the bar graphs in the document.

Table S1: Abbreviation.

Table S2: Primer sequences for humans.

Table S3: Primer sequences for mice.

Table S4: Primer sequences for rats.

Table S5: Demographic and basic clinical characteristics of patients involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in Figure 4a,b of this study are openly available in [Cistrome DB] at http://cistrome.org/db/#/ [doi: 10.1038/nature11247; and doi: 10.1172/JCI62613], reference number [37, 38]. The data that support the findings in Figure 5d of this study are openly available in [The UCSC Cell Browser] at https://cells.ucsc.edu/ [doi: 10.1038/s41586‐019‐1414‐x; and doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab503], reference number [39, 40].