Abstract

Background

The development of functional muscles in Drosophila melanogaster relies on precise spatial and temporal transcriptional control, orchestrated by complex gene regulatory networks. Central to this regulation are cis-regulatory modules (CRMs), which integrate inputs from transcription factors to fine-tune gene expression during myogenesis. In this study, we investigate the transcriptional regulation of the LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Tup (Tailup/Islet-1), a key regulator of dorsal muscle development.

Methods

Using a combination of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion and transcriptional analyses, we examined the role of multiple CRMs in regulating tup expression.

Results

We demonstrate that tup expression is controlled by multiple CRMs that function redundantly to maintain robust tup transcription in dorsal muscles. These mesodermal tup CRMs act sequentially and differentially during the development of dorsal muscles and other tissues, including heart cells and alary muscles. We show that activity of the two late-acting CRMs govern late-phase tup expression through positive autoregulation, whereas an early enhancer initiates transcription independently. Deletion of both late-acting CRMs results in muscle identity shifts and defective muscle patterning. Detailed morphological analyses reveal muscle misalignments at intersegmental borders.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore the importance of CRM-mediated autoregulation and redundancy in ensuring robust and precise tup expression during muscle development. These results provide insights into how multiple CRMs coordinate gene regulation to ensure proper muscle identity and function.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13395-025-00392-4.

Keywords: Myogenesis, Enhancers, Transcriptional regulation, Multiple CRMs, Muscle identity, Muscle patterning

Background

Animals display an assembly of skeletal muscles of various sizes and shapes that underlies/allows specific movements. In most cases, multiple muscles are cooperatively involved. The diversity of muscles raises the question of how individual muscles acquire the necessary shapes and specific attachment sites during development. In Drosophila larvae, muscles are single multinucleated fibers which develop by fusion of one founder cell with fusion-competent myoblasts. The identity of each founder cell (FC) is determined by its unique combination of identity transcription factors (iTFs) and by the precise timing and levels at which those factors are expressed [6, 17, 21]. FC identity specification is a multi-step process, starting with the delineation of promuscular clusters (PMCs), groups of equipotent cells from which progenitor cells (PCs) are selected. PCs then divide asymmetrically, giving rise to two different FCs, or, in a few cases, one FC and another lineage [5, 18]. Expression of different iTFs in different FCs starts with iTF activation in PMCs in response to positional information and progressive refinement in PCs and FCs through cross-regulations between different iTFs and response to Notch signaling and Hox information [14, 15]; Enriquez et al., 2010; Dubois et al., [21]. During the fusion process, the specific iTF code expressed by the founder cell (FC) is transferred to the nuclei of fusion-competent myoblasts (FCMs) in the syncytium, effectively reprogramming FCMs to adopt FC identity (Knirr et al., 1999; Crozatier and Vincent [3, 16],. This reprogramming is thought to activate downstream genes that control the final muscle morphology [4]; Junion and Jagla, 2022) (Fig. 1A).

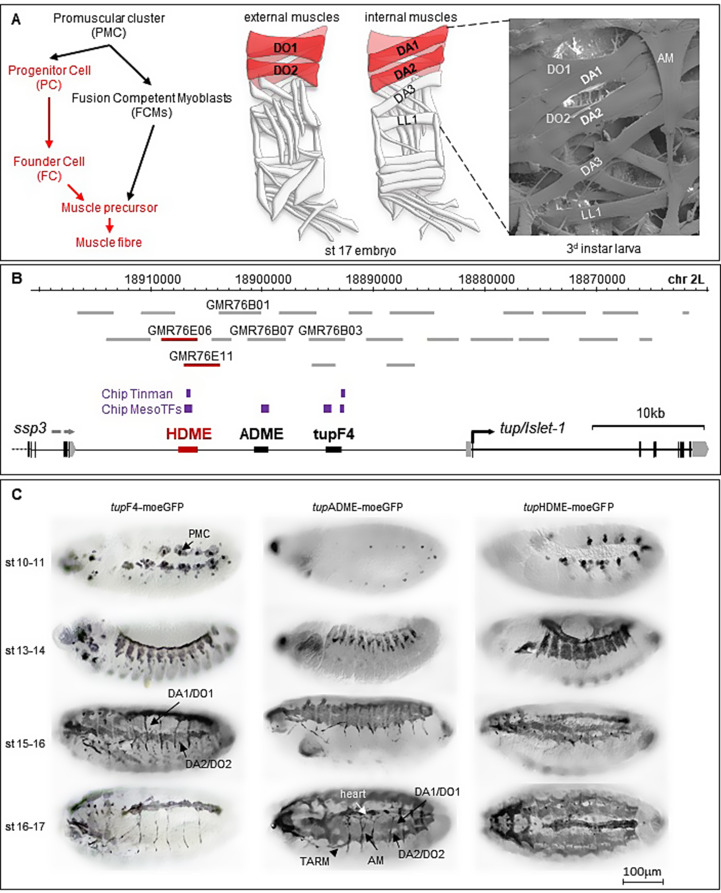

Fig. 1.

Three distinct Cis-Regulatory Modules regulate tup expression in dorsal muscle tissue. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the external (left) and internal (middle) somatic muscles in a late embryo (st17). The shape and position of the four dorsal muscles (DA1/DO1 and DA2/DO2) within an abdominal segment are highlighted in red. The dorso-lateral (DA3) and lateral (LL1) muscles are also indicated. Scanning electron microscopy of an abdominal segment (right) from a third instar larva (L3) shows the shape and position of the four dorsal muscles and the alary muscle (AM). (B) Schematic representation of the tup transcribed region. The positions of tested GMR and VT fragments are shown as grey horizontal bars, with numbers indicating those active in dorsal muscles. Clusters of in vivo mesodermal transcription factor binding sites (chip meso TFs) and Tinman (chip Tinman) binding sites are marked by purple bars. Two previously identified cis-regulatory modules (tupF4 and tupADME) and a newly identified module (tupHDME, red bar) are shown. (C) Each CRM was fused to moe-GFP reporter gene, and GFP expression detected using an anti-GFP antibody. The three CRMs together recapitulate tup expression in promuscular clusters (PMC), dorsal muscles (DA1/DO1 and DA2/DO2), alary muscles (AM), thoracic alary-related muscles (TARM), and heart cells during embryonic development (stages 10 to 17). Scale bar: 1 cm = 100 μm

The development of functional muscles in Drosophila melanogaster therefore relies on precise spatial and temporal transcriptional control of each iTF expression [21]. Central to this regulatory architecture are cis-regulatory modules (CRMs); short DNA sequences that integrate inputs from multiple transcription factors/signaling pathways to finely regulate gene expression. CRMs essentially determine when, where, and how much a gene is expressed, providing both flexibility and robustness to developmental gene expression [8, 40]; Kvon et al., 2021). Developmental genes typically display multiple CRMs, often spread across large genomic regions [31, 35]. Originally, it was thought that CRMs each drive distinct spatiotemporal aspects of gene expression, following a model of modular regulation [1, 23, 24]; Long et al. 2016; Shlyueva et al., [32]. This was an oversimplified model, however, since, in many cases CRMs regulating the same gene exhibit overlapping spatiotemporal activity, leading to the notion of cumulative regulation including by primary and shadow enhancers (Hoch et al., 1990; Jeong et al., 2006; Zeitlinger et al., [9, 12, 33, 39]; Cannavo et al., 2016; Whitney et al., [37].

The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Tailup (Tup) is the Drosophila ortholog of vertebrate Islet1. We have shown that embryos carrying null tup mutations (tupex4) display a disorganized dorsal musculature, indicating that tup plays a key role in establishing the stereotypical pattern of the dorsal muscles of Drosophila larvae [10]. However, the pleiotropy of tupex4 mutant phenotypes, including germ band retraction failure and defects in cardiogenesis and hematopoietic organ (lymph gland, LG) formation [34]; Mann et al., 2009) precluded precise analysis of muscle patterning defects. To overcome this difficulty, we undertook to further characterize the tup regulatory region, in order to identify CRMs which could be used to generate and characterize muscle-specific tup mutants.

Here, we first report that transcription of tup in 4 dorsal larval muscles and the alary muscles (AM) relies upon three distinct CRMs spread over 26 kb of regulatory region. Two CRMs, namely tupADME and tupHDME, function in a partially redundant manner to maintain robust tup expression in the dorsal FCs and their growing muscle syncytia, and this involves Tup direct autoregulation. The third CRM, tupF4 [34], initiates tup transcription in the two dorsal progenitors that give rise to these four founder cells, as well as in the alary muscle lineage, but appears not strictly required to trigger tup autoregulation in FCs. CRISPR-Cas9–mediated deletions of late-acting tup muscle CRMs show that tup function in specifying dorsal muscle identity relies on the combined activity of these two CRMs. Loss of tup transcription in growing muscle syncitia, leads to mis-matching of dorsal muscles attachment sites at segmental borders.

In summary, this study provides new insights into the transcriptional regulation of tup/Islet1 during Drosophila muscle development. By dissecting the contributions of individual CRMs, we propose a model in which sequential and lineage-specific activity of different CRMs allows for the progressive acquisition of muscle identity, ensuring robust muscle patterning. These findings contribute to a broader understanding of how multiple CRM-mediated gene regulation orchestrates complex developmental processes and provides resilience against genetic or environmental perturbations.

Methods

Fly strains

All Drosophila melanogaster stocks and genetic crosses were grown using standard medium at 25 °C. All the lines were provided by the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center except tupex4 (de Navascues and Modolell, 2007). Lines used are white[1118] (BDSC_3605), vasa-cas9VK00027 (BDSC_51324 ) and the 21 tup Janelia-Gal4 lines (GMR) (Pfeiffer and al., 2008) listed in the Table 1. We also used 5 Vienna tiles enhancer-Gal4 lines (VT) from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (Kvon et al., 2014) listed in the Table 1.

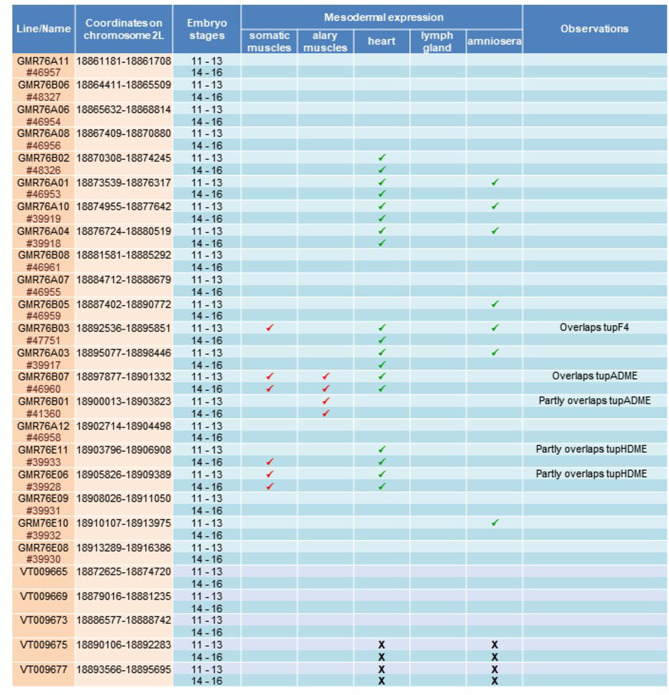

Table 1.

Expression patterns of Janelia (GMR) and Vienna tiles (VT) lines. Summary of Janelia (GMR) and Vienna tiles (VT) lines used to characterize the cis-regulatory sequences of Tup/Islet-1, with expression in different mesodermal tissues indicated by a green tick. A total of 26 lines were tested (21 Janelia and 5 VT) covering 50 kb of tup genomic region (see also Fig. 1B). Five lines displayed expression in somatic muscles (red tick): lines 76B03, 76B07, 76B01, 76E11, and 76E06, two of which, 76B01 and 76B07 showed also expression in alary muscles (AMs)

CRM deletions generated by Crispr/Cas9

Genomic tup target sites were identified using http://tools.flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/targetFinder/ [25]. Prior to final selection of RNA guides (gRNA) for deletions of tup CRMs, genomic PCR and sequencing of DNA from vasa-cas9VK00027 flies was performed to check for polymorphisms in the targeted regions. Guides targeting tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME were inserted in the pCFD4: U6:3-gRNA vector (Addgene no: 49411) as described [27], (see http://www.crisprflydesign.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/06/Cloning-with-pCFD4.pdf). All guides were verified by sequencing. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used to construct each gRNA expression plasmid are:

tupF4: gRNA1: 5’-TTGTTGGCACTCCGATCTGAAGG-3’ and gRNA2: 5’-TTGTCTGC GGCAAGCGTCGAAGG-3’;

tupADME: gRNA1: 5’-GCAGCCCTGATCCTGACCGTTGG-3’ and gRNA2: 5’-GGCAG ATTTAGTCCGTCAGTCGG-3’;

tupHDME: gRNA1: 5’-CTCTTTAAAGGGAAGCTCAACC-3’ and gRNA2: 5’-CACCAAC TGGAGTGCCAGTGCC-3’.

To delete the core region of tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME, vasa-cas9 embryos were microinjected with gRNAs in pCFD4 (200 ng/µl). Each adult hatched from an injected embryo was crossed to the balancer stock snaSco/CyO, {wgen11-LacZ} and 100–200 F1 flies were individually tested for either tup CRM deletion by PCR on genomic DNA.

Reporter constructs, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization

The yellow intron (yi), FlyBase ID #FBgn0004034 (position: 356918–359616) was inserted in the lacZ coding region between aa (Tyr 952) and aa (Ser 953) by standard PCR-based cloning position [13]. The resulting fragment was cloned downstream of tupCRM (tupF4, tupHDME and tupADME) inserted in a pAttB vector, and micro-injected in embryos for chromosomal insertion at position 68A4. Antibody staining and in situ hybridization with intronic probes were as described previously [21]. Primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-Kr (1/300), mouse anti-LacZ (1/1000; Promega), rabbit anti-GFP (1/1000; Torrey Pines Biolabs), chicken anti-GFP (1/500; Abcam), Phalloidine-Texas RedX (1/500; Thermofisher Scientific). Secondary antibodies were: Alexa Fluor 488-, 555- and 647- conjugated antibodies (1/300; Molecular Probes) and biotinylated goat anti-mouse (1/2000; Vector Laboratories). Digoxygenin-labelled antisense RNA probes were transcribed in vitro from PCR-amplified DNA sequences, using T7 polymerase (Roche Digoxigenin labelling Kit).

In situ Hybridization were done as described [21]. When antibody staining and FISH were combined, the standard immuno-histochemistry protocol was performed first, with 1U/µl of RNase inhibitor from Promega included in all solutions, followed by the FISH protocol. Confocal sections were acquired on Leica SP8 or SPE microscopes at 40x magnifications, 1024 × 1024 pixels resolution. Images were assembled using ImageJ and Photoshop softwares.

Phenotype quantification at embryonic and larval stages

To quantify embryonic phenotypes, wt; VgM1-moeGFP and ΔtupADME + HDME; VgM1-moeGFP embryos were immunostained with a primary mouse anti-GFP (1/500) (Roche) and secondary biotinylated goat anti-mouse (1/2000) (VECTASTAIN® ABC Kit). Stained embryos were imaged using a Nikon eclipse 80i microscope and a Nikon digital camera DXM 1200 C. A minimum 50 abdominal segments of stage 16 embryos were analyzed for each genotype. (wt: N = 10 embryos; ΔtupADME + HDME: N = 10 embryos). The percentage of altered DA2 or DA1 per embryo was determined by analyzing the morphology of DA2 and DA1 muscles in 76 and 77 segments respectively in wt embryos (N = 10) and 67 and 52 segments in ΔtupADME + HDME embryos (N = 10). To quantify larval phenotypes, wandering L3 larvae were analyzed. 6 wt (N = 6) and 11 ΔtupADME + HDME (N = 11) larvae were used. Morphologies of DA2 and DA1 muscles were examined in 31 wt segments (N = 6) and in 55 ΔtupADME + HDME segments (N = 11) by scanning electron microscopy.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.). Significance levels are indicated as follows: P-value < 0.01:** and P-value < 0.001:***).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

To prepare fillets, third instar wild type and homozygous ΔtupADME + HDME larvae raised at 25 °C were dissected in myorelaxant buffer, according to [38]. Larvae were cut longitudinally on the ventral side to preserve and expose the dorsal and dorso-lateral musculature. Fillets were then fixed 1 h in a 4% formaldehyde/ 2.5% glutaraldehyde mixture in 1X PBS, washed in water and dehydrated gradually in ethanol. Fillets were dried at the critical point (Leica EM CPD 300 critical point apparatus), covered with a platinum layer (Leica EM MED 020 metalliser) and imaged with a Quanta 250 FEG FEI scanning microscope.

Results

Three separate tup CRMs regulate tup expression in dorsal skeletal muscles

Tup is expressed in the muscle progenitor cells (PCs) at the origin of the four dorsal-most somatic muscles of the Drosophila embryo and larva: DA1, DA2, DO1, and DO2 [10]; Fig. 1A). Two cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) have previously been associated to this expression: tupF4, a 1.5-kb DNA fragment located between − 13.5 and − 12 kb upstream of the tup transcription start site drives tup expression in various cell types issued from the dorsal mesoderm: lymph gland cells, alary muscles (AMs), pericardial cells, and cardioblasts, in addition to skeletal muscles [34]; tupADME, a 1,3-kb fragment located between − 19.8 and − 18.5 kb upstream of the transcription start site which drives tup expression only in the alary muscles and dorsal somatic muscles [11]; Fig. 1B). These two CRMs were identified through in silico search of evolutionarily conserved sequence blocks and ChiP-seq-experiments targeting mesodermal transcription factors (MesoTFs), including Tinman (Tin) (Philippakis et al., 2006; Zinzen et al., [40]; Jin et al., 2013; Fig. 1B and Fig.S1-S2). Both tupF4 and tupADME also contain conserved Org-1 binding sites critical for regulating tup transcription in the alary muscles [11]. ChIP-seq analyses identified a third cluster of MesoTFs binding sites upstream of tupADME, suggesting the existence of an additional mesodermal tupCRM. (Fig. 1B). To sustain in silico analyses, we screened the full set of publicly available (GMR and VT) expression reporter lines (Pfeiffer et al., 2008; Kvon et al., 2014) covering 55-kb of tup genomic region (Fig. 1B). Five GMR lines, GMR76B01, GMR76B03, GMR76B07, GMR76E06 and GMR76E11 showed expression in heart cells, alary muscles and dorsal muscles (Table 1). GMR76B03 overlaps with tupF4, while GMR76B01 and GMR76B07 overlap with tupADME (Fig. 1B; Table 1). The other lines, GMR76E06 and GMR76E11 displayed expression in heart cells and dorsal muscles, identifying and additional tup mesodermal CRM located between − 26.7 and − 25 kb upstream of the tup transcription start site, i.e., around 5 kbp upstream of tupADME (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Interestingly, GMR76E11 showed delayed and weaker expression in DA2 and DO2 muscles than GMR76E06 (Fig.S3), suggesting that GMR76E06 contains regulatory information absent in GMR76E11. In support of this, DNA sequence analysis indicated that GMR76E06 contains evolutionarily conserved Tup binding sites not present in GMR76E11, while both reporters contain Tin binding sites (Fig.S4). Based on sequence and expression data, a new reporter construct was designed to both encompass conserved sequence blocks shared by GMR76E06 and GMR76E11 and the Tup binding sites (Fig.S4). Expression analysis of this construct confirmed activity both in heart cells and dorsal muscles, leading us to name it tupHDME (Heart and Dorsal Muscles Enhancer) (Fig. 1B and C).

We then compared the activity of tupF4, tupADME, and tupHDME at different embryonic stages, using moe-GFP as reporter (Fig. 1C). The expression of tupF4-moeGFP in promuscular clusters (st10-11), suggested that it plays an early role in early tup mesodermal expression. From embryonic stages 13 to 15, the three CRMs showed overlapping expression in dorsal muscles precursors, suggesting a relay of the proximal tup activating CRM by the distal CRMs. By stage 15, tupF4-moeGFP expression began to decrease in DA1 and DO1, to become undetectable in all dorsal muscles by stage 16. Dorsal views of stage 16 embryos showed both tupF4-moeGFP and tupHDME-moeGFP expression in the lymph gland, pericardial cells, and cardiomyocytes, and tupADME-moeGFP expression only in Svp-positive cardioblasts which give rise to ostiae (Molina and Cripps, 2001; Tao et al., [34] (Fig.S5A). On top of that, tupF4-moeGFP and tupADME-moeGFP expression is detected in the alary muscles, whereas tupHDME-moeGFP expression is detected in anterior pharyngeal muscles (Fig.S5A, B).

In summary, characterisation of the tup cis-regulatory landscape shows three distinct CRMs, tupF4, tupADME, and tupHDME, scattered within 26 kb of tup upstream DNA, contribute to control tup transcription in different mesodermal tissues in Drosophila embryos (Fig. 1 and S5B). Their partly overlapping patterns of activity, both spatially and temporally, suggests that these three CRMs combinatorically ensure precise control of tup expression in somatic muscles and AM, as well as heart and lymph gland cells during embryonic development.

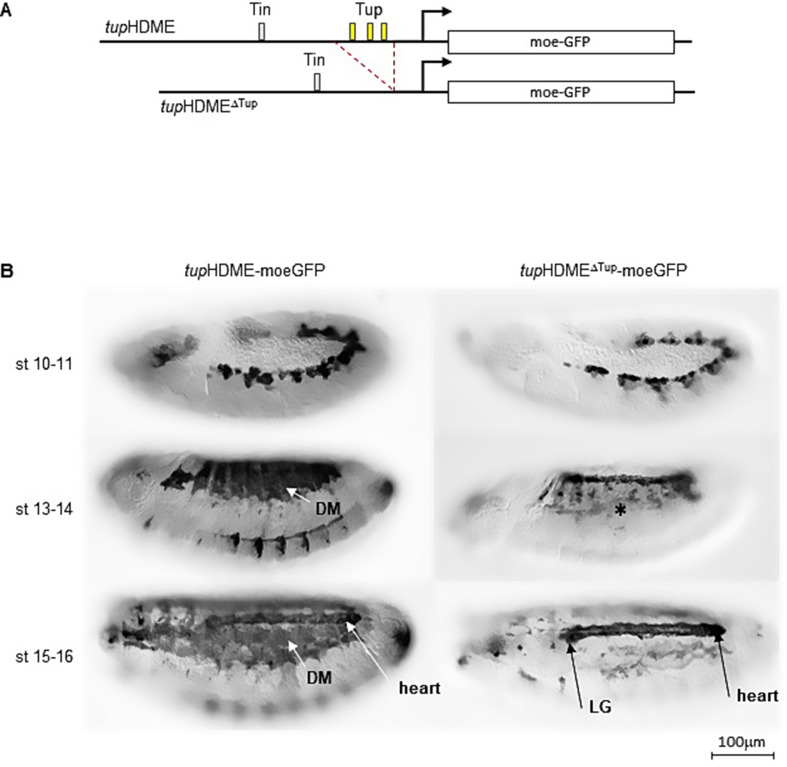

Direct autoregulation of tuphdme in dorsal muscles

We previously showed that tup transcription in dorsal muscles is lost in Tup protein null (tupex4) embryos, indicating a positive autoregulation mechanism [10]. To investigate whether Tup protein directly regulates its own expression through the three CRMs, we performed in situ hybridization using a LacZ probe in tupex4 mutant embryos carrying LacZ reporter gene driven by each individual CRM (Fig.S6). We observed that tupF4 activity in dorsal muscles is unaffected by the loss of Tup protein (Fig.S6A), consistent with the absence of Tup binding sites in this CRM (Fig.S1). In contrast, tupADME (Fig.S6B) and tupHDME (Fig.S6C) showed a complete loss of LacZ transcription in the dorsal muscles, indicating that Tup protein is required for the activation of these CRMs. Both tupADME and tupHDME contain predicted Tup binding sites (Fig.S2 and S4), suggesting that Tup directly autoregulates its expression through one or both these CRMs in the embryos. In support of this, previous work showed that mutation of the single tupADME Tup binding site reduced tupADME activity in dorsal muscles, while not in alary muscles [11]. tupHDME contains three clustered conserved Tup binding sites (Fig. 2A and Fig. S4). To determine whether tupHDME is also subject to autoregulation, we generated a modified tupHDME reporter construct lacking all three predicted Tup binding sites, tupHDMEΔTup (Fig. 2A). We found that tupHDMEΔTup activity was completely lost in dorsal muscles while maintained in heart cells and the lymph gland (Fig. 2B), showing that Tup autoregulation is required for tupHDME activity in developing dorsal muscles.

Fig. 2.

Tup binding sites are required for specific tupHDME autoregulation in dorsal muscles. (A) A deletion removing all the three Tup binding sites gave the tupHDMEΔTup-moeGFP reporter. (B) While tupHDME-moeGFP is expressed both in the heart, lymph gland (LG) and dorsal muscles (DM), tupHDMEΔTup-moeGFP is only expressed in the heart and LG, highlighting tup direct autoregulation in muscles. Scale bar: 1.3 cm = 100 μm

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that Tup autoregulation is essential for maintaining tup expression specifically in dorsal muscles by directly binding to the tupHDME in addition of tupADME CRM. However, tup expression in other mesodermal tissues, such as heart cells and the lymph gland, occurs independently of Tup protein, suggesting that other combinations of transcription factors, which include Org-1, tunes the level of tup expression in different mesodermal tissues.

Combinatorial regulation of tup transcription in dorsal muscles

To further investigate temporal and lineage-specific aspects of tup regulation by different CRMs and overcome limitations associated with reporter protein stability, we compared the patterns of endogenous and reporter nascent transcripts using in situ hybridization with intronic probes (Fig. 3). We first examined endogenous tup transcription throughout embryonic development, using a probe against the first tup intron. To help identifying individual dorsal muscles, we immunostained embryos for Krüppel (Kr) which marks the DA1, DO1 (and LL1) progenitor cells, founder cells and muscle precursors, in addition to amnioserosa cells [7, 19] (Fig.S7). In situ data confirmed that tup transcription starts at the promuscular stage, embryonic stage 10 and is maintained in dorsal muscles until stages 14–15. Overlap between tup nascent transcripts and Kr immunostaining from stages 12 to 14 (Fig.S7 - yellow frames A, B, C) confirmed that tup is transcribed in the nuclei of DA1 and DO1 founder cells and later in the nuclei of developing DA1 and DO1 fibers. By stage 16, tup transcription was no longer observed in dorsal muscles, while persisting in cardiac and pericardial cells and the alary muscles. At stage 16, Kr expression is also lost in the muscle fibers and solely detected in the trachea, which runs internal to the somatic musculature.

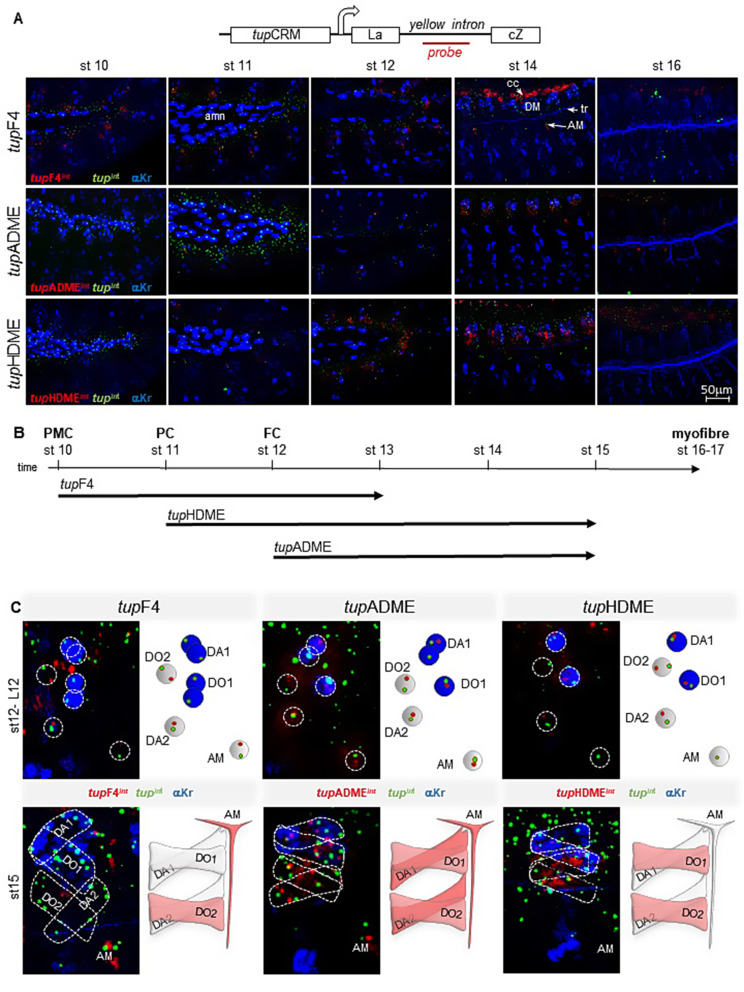

Fig. 3.

tupCRMs sequential activities during dorsal muscles development. (A) Activity of tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME compared to endogenous tup expression between embryonic stages 10 and 16. Nascent transcripts were visualized using intronic probes for tup (green dots) and the reporter gene (yellow intron into lacZ) red dots. Krüppel (Kr) antibody staining (blue) identifies the amnioserosa (amn), cardiac and pericardial cells (cc and pc), the DA1/DO1 progenitors and muscles, and the trachea (tr) (see also Fig.S8). Scale bar: 0.6 cm = 50 μm. (B) Diagram summarizing the sequential activity of tup CRMs at the different stages of muscle development: promuscular cluster (PMC), progenitor cell (PC), founder cell (FC) and myofiber. (C) Left panels: detailed view of tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME activity at the FC (stage 12) and syncytial fiber (stage 15) stages, using in situ hybridization as in Fig. 3A. Right panels: schematized activity of each CRM in the DA1, DO1, DA2, DO2 and AM FCs (stage 12, red dots) and growing muscles (stage 15, red colored)

To precisely determine which aspects of tup transcription correlated with each tup CRM, we introduced a yellow intron into the LacZ reporter coding region (Fig. 3A). Using dual in situ hybridization for intronic probes enabled us to precisely compare endogenous tup transcription (tupint) and each tupCRM-driven transcription (tupF4int, tupADMEint and tupHDMEint) at each step of muscle development. To facilitate their identification, DA1/DO1 nuclei were labeled by Kr immunostaining. The results showed that only tupF4 is active in promuscular clusters, stage 10, confirming its role in initiating tup transcription. By stage 14, tupF4-driven transcription was no longer detected in dorsal muscles, while it persisted in cardiac and pericardial cells, and alary muscles. tupHDME activity was first detected at stage 11, in dorsal muscle progenitor cells, whereas tupADME activity was detected later, in dorsal muscles founder cells (FCs), stage 12 (Fig. 3A). Unlike tupF4, tupHDME and tupADME kept being active during myofiber elongation, stage 14. tupADME and tupHDME-driven transcription was no more detected in dorsal muscles by stage 16 (Fig. 3A). Together, these findings show that tupF4 is active in dorsal promuscular clusters and that tupADME and tupHDME regulate tup transcription during muscle fiber development, with partial temporal overlap between the three CRMS (Fig. 3B). Previous analysis of dorso-lateral muscle lineages has shown that the birth time of different muscle FCs follows a precise sequence and that temporal windows of a given iTF expression may differ in different muscle lineages [21]. To determine the lineage-specificity of individual tupCRMs, we focused our analysis on two key stages of muscle development: stage 12, when FC identity is specified (Frasch, 1999; De Joussineau et al., [17, 21], and stage 15, when FC transcriptional identity has been propagated to nuclei of fused myoblasts, a process known as identity reprogramming of syncytial nuclei [3, 16, 20]. Kr immunostaining and positional information were used to identify each dorsal muscle lineage at stage 12 (Fig. 3C). tup in situ confirmed tup transcription in the four dorsal muscle FCs, and initiation of tup transcription in the nuclei of “naïve” myoblasts (FCMs) incorporated into developing dorsal muscles. It also showed that tupF4 remains active in the DA2 and DO2 (and AM) FCs and not the dorsal-most DA1 and DO1 FCs. At that stage, both tupADME and tupHDME become active in the four dorsal FCs. By stage 15, the dynamics have shifted, with tupF4 remaining active only in DO2, tupADME being active in all four muscle lineages, and tupHDME active only in the DO1 and DO2 lineages (Fig. 3C). As documented above, (Fig. 2), the temporal relay between early and late CRMs in dorsal muscles involves direct Tup autoregulation, a mechanism which operates neither in heart nor lymph gland cells, nor in the alary muscles.

Taken together, analysis of nascent endogenous and reporter transcripts revealed a temporal, lineage-specific sequence of tup regulation during Drosophila muscle development. tupF4-driven early tup transcription in promuscular clusters is relayed by tupADME and tupHDME activities which ensure propagation of tup transcription to fused nuclei during muscle fiber formation in a lineage-specific manner.

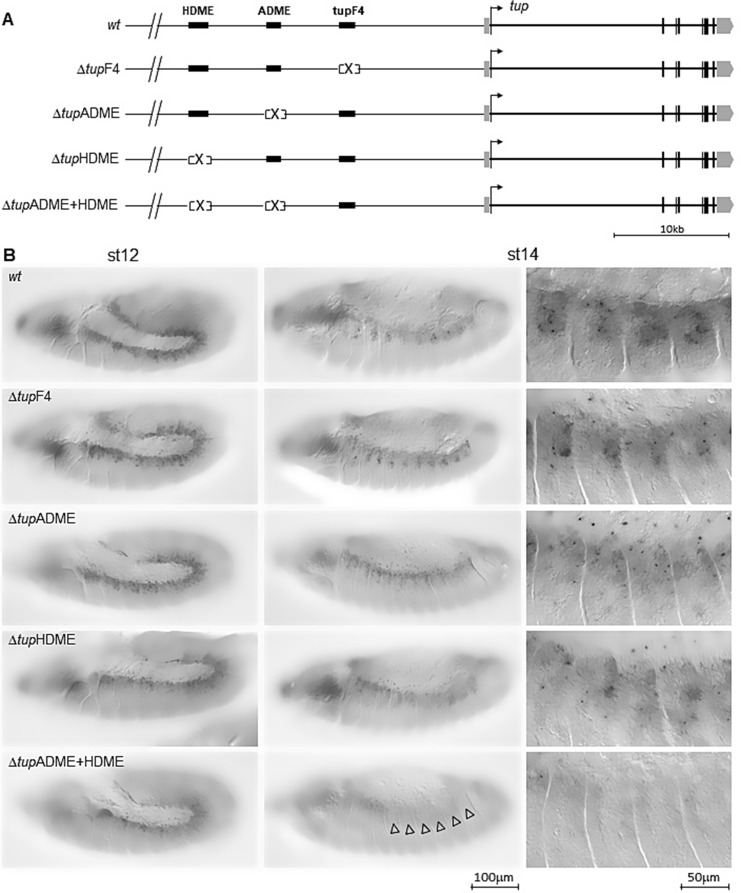

Deletion of TupADME and tuphdme impairs tup transcription in dorsal muscles

To investigate the individual roles of each tup cis-regulatory module (CRM) and their combined effect on somatic muscle identity, we generated dorsal muscle-specific tup mutants by using CRISPR-Cas9 to delete the muscle-specific tup CRMs (Fig. 4A). Neither individual CRM deletion resulted in germ band retraction failure, allowing to analyse in detail muscle development. As a first step, we analysed tup transcription in embryos homozygous for each CRM deletion (Fig. 4B). Global analysis at stages 12 and 14 showed that deletion of neither individual CRMs was sufficient to eliminate tup transcription in developing muscles. The detection of tup transcription in ΔtupF4 embryos, indicated that, while subject to direct autoregulation, tupADME or/and tupHDME activity does not depend upon earlier tupF4 activity. tup transcription in at least a fraction of dorsal muscle nuclei, was detected as well at stage 14 upon deletion of either tupADME or tupHDME, suggesting their redundancy. In contrast, tup transcription was lost at stage 14 in the double tupADME and tupHDME (ΔtupADME + HDME) deletion mutant (clear arrowheads), indicating that these two CRMs are together required for propagating transcriptional identity of FCs during reprogramming of fused FCMs into growing syncitia (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Deletion of ADME + HDME CRMs abolishes tup transcription in dorsal muscles. (A) Schematic representation of the different deletions of tup CRMs. Homozygous flies lines were generated for each CRM (ΔtupF4, ΔtupADME, ΔtupHDME) and a double tupADME and tupHDME deletion (ΔtupADME + HDME). (B)tup transcription in these homozygous lines compared to wt, using in situ hybridization to nascent transcripts (small black dots). tup transcription in the dorsal muscles is lost at stage 14 upon removing both ADME + HDME CRMs (empty arrowheads). Scale bar: 1.2 cm = 100 μm for the whole panels except for the five rightmost panels; scale bar: 1.2 cm = 50 μm

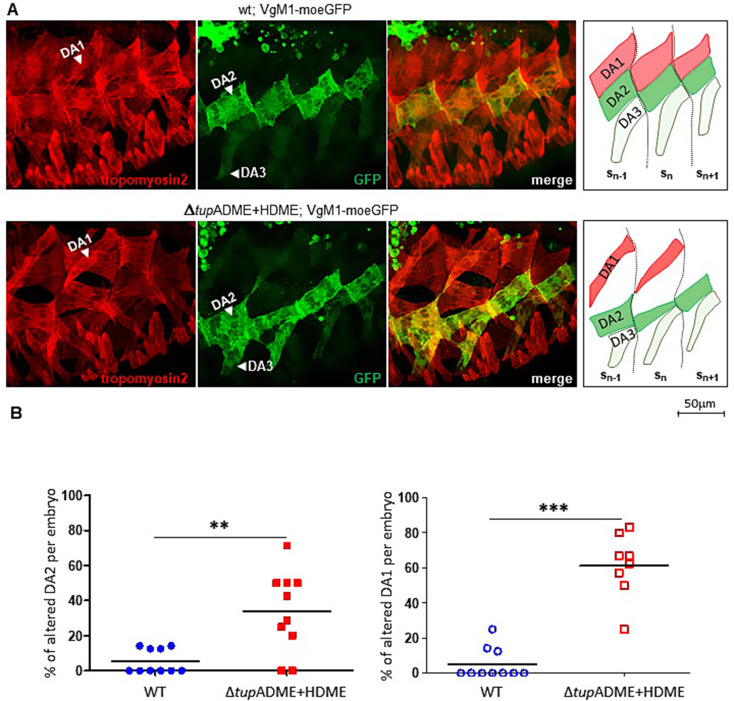

Deletion of TupADME and tuphdme disrupts the dorsal muscle pattern

Since tup transcription in developing muscles was only abolished in the double ΔtupADME + ΔtupHDME CRM deletion mutants, we focused our analysis on muscle morphology in these mutants in late embryos and third instar larvae, as the new tup alleles did not display the embryonic lethality and pleiotropic effects typically associated with complete tup loss-of-function. We first analysed the muscle patterns in stage 16 embryos, using Tropomyosin 2 immuno-staining of the somatic musculature together with the VgM1-moeGFP reporter line [13] which allows morphological inspection of the DA2 and DA3 muscle lineages. In wt embryos, VgM1-moeGFP expression illustrates the staggered rows pattern of DA muscles, with the posterior attachment sites of the DA2 and DA3 muscles of one segment facing the anterior attachments of DA1 and DA2, respectively, in the next segment (Fig. 5A), a pattern repeated between successive adjacent segments reflecting muscle attachment sites matching [13]. ΔtupADME + HDME mutant embryos displayed a disorganised dorsal muscle pattern (Fig. 5A), showing that tupADME/HDME combinatorial activity is required for tup role in dorsal muscle identity. Detailed analysis or VgM1-moeGFP expression shows that the DA1 and the DA2 muscles are misshaped or absent in 61.0 ± 6.5% and 33.8 ± 7.3% of segments per embryo, respectively, compared to 5.2 ± 2.8% and 5.3 ± 2.2%, respectively in wt-type embryos (Fig. 5A-B). ΔtupADME + ΔtupHDME mutant embryos exhibit a partial transformation of the DA2 muscle into a DA3 identity, rather than the complete transformation observed in tup null embryos [11]. Misalignment of DA1/DA2 and DA2/DA3 are illustrated by schematic drawings across three consecutive segments Sn−1, Sn, and Sn+1 (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Loss of tup transcription disrupts the pattern of embryonic dorsal muscle. (A) Dorsolateral views of stage 16 wt (top panels) and homozygous ΔtupADME + HDME embryos (bottom panels) carrying the Vg1-4-moeGFP reporter, stained for tropomyosin 2 (red) and GFP (green). Four consecutive segments are shown. Vg1-4-moeGFP is strongly expressed in the DA2 and weakly the DA3 muscles. Right panels are schematic representations of the position, shape, and segmental attachments of the DA1 (red), DA2 (green), and DA3 (light green) muscles in three consecutive segments (Sn−1, Sn, and Sn+1). The intersegmental boundaries are represented by dashed black lines. In absence of tup transcription (ΔtupADME + HDME; Vg1-4-moeGFP embryos), the DA1 and DA2 shapes and attachment sites are strongly abnormal and the matching of DA3-DA2, DA2-DA1 intersegmental attachment sites vastly disturbed. tup transcription in these homozygous lines compared to wt, using in situ hybridization to nascent transcripts (small black dots). tup transcription in the dorsal muscles is lost at stage 14 upon removing both ADME + HDME CRMs (clear arrowheads). Scale bar: 1.2 cm = 50 μm. (B) Percentage of altered DA2 and DA1 muscles in wt and ΔtupADME + HDME embryos. Scatter plots show data from 10 embryos per genotype (N = 10; blue circles: wt; red squares: ΔtupADME + HDME). Each point represents the percentage of altered DA2 (left) or DA1 (right) muscles per embryo. (P-value < 0.01:** and P-value < 0.001:***)

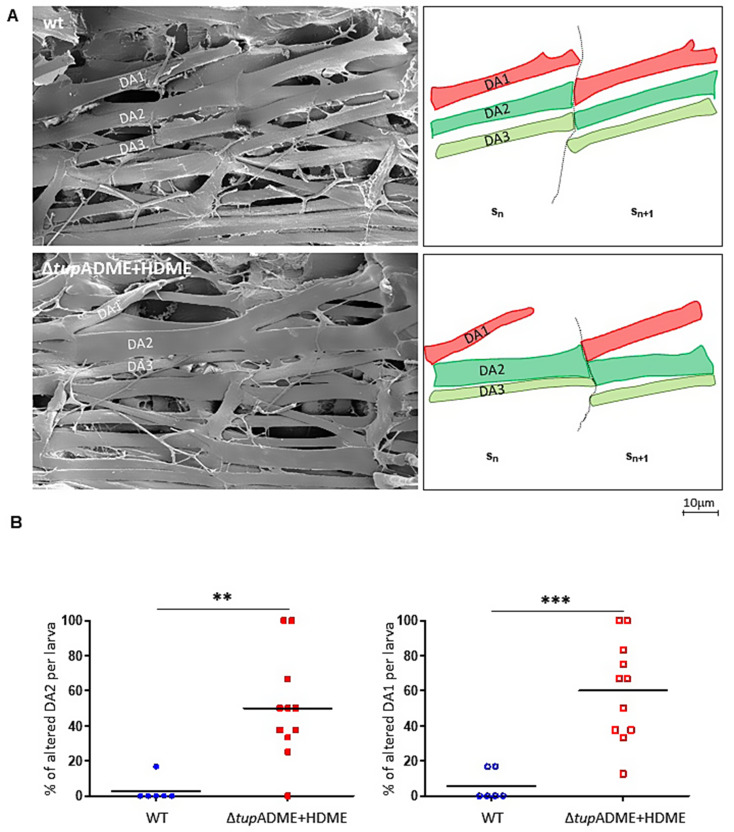

Dorsal muscle attachment matching is disrupted in ΔtupADME + HDME 3rd instar larvae

To further investigate muscle morphological defects due to ΔtupADME + HDME CRMs deletion, we analysed the somatic musculature of third instar larvae using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of dissected fillets (Fig. 6). This allows precise investigation of the DA muscles attachments [13]. As previously described, the staggered ends pattern of dorsal muscles established in wt late embryos (Fig. 5A) is maintained in wt larvae (Fig. 6A). In ΔtupADME + HDME larvae, the muscle attachment matching is severely disrupted, with defects in DA1 and DA2 muscle morphology and attachment sites observed in 60.2 ± 8.6% and 50.1 ± 9.0% of segments per larva, respectively, compared to 2.8 ± 2.7% and 5.6 ± 3.5%, respectively, in wt larvae (Fig. 6B). Beside the loss of dorsal attachment of the DA1 muscle, one striking phenotype is the homotypic (DA2/DA2) attachment of DA2 muscles in consecutive segments, while only heterotypic DA3/DA2 and DA2/DA1 matchings are observed in wt embryos. This observation is consistent with an identity shift of the DA2 muscle towards a DA3 muscle identity.

Fig. 6.

Muscle mismatching in ΔtupADME + HDME L3 larvae. (A) Left, scanning electron microscopy of filleted wt and ΔtupADME + HDME larvae showing dorso-lateral muscles in two consecutive segments. Right, schematic representations of the position, shape and attachment sites of DA1 (red), DA2 (green), and DA3 (light green) muscles. In the absence of tup, there is muscle attachment sites mismatching at the intersegmental boundary (dashed black line). Scale bar: 0.8 cm = 10 μm. (B) Percentage of altered DA2 and DA1 muscles in wt and ΔtupADME + HDME larvae. Scatter plots show data from 6 wt larvae (blue circles, N = 6) and 11 ΔtupADME + HDME larvae (red squares, N = 11). Each point represents the percentage of altered DA2 (left) or DA1 (right) muscles per larva. (P-value < 0.01:** and P-value < 0.001:***)

The similarity between the late embryonic and 3rd instar larval phenotypes confirm the key role of Tup in establishing the correct morphological identity of dorsal muscles during embryogenesis. Together with previous analysis of mutants for another DA identity gene, collier [13], analysis of muscle-specific tup mutations shows that the precise heterotypic matching of muscles attachment sites at segmental borders is a sensitive read-out of muscle transcriptional identity.

Discussion

A stereotyped set of 30 somatic muscles in each abdominal segment underlies Drosophila larval crawling [5]. Each muscle morphology reflects expression of a specific combination of “identity transcription factors” (iTFs) by its founder cell (Frasch, 1999; De Joussineau et al., [17, 21]. A subset of iTFs is already activated in PMCs from which PCs and FCs are selected. For example, the PCs which give rise to the DA2 and DA3 FCs are both selected from a PMC expressing Tinman (NKx2.5), Collier (Col/Kn) and Tup. It is the sequential birth of the DA2 and DA3 PCs which determines that Tup remains expressed in the DA2 PC and FC and Col in the DA3 FC (Enriquez et al., 2010; Boukhatmi et al., [10]. Here, we further investigated the regulation and role of Tup/Islet1 in PCs/FCs seeding the formation of dorsal muscles.

CRM redundancy and robustness of tup expression in the dorsal mesoderm

We identified a third, distal, tup CRM, which we named Heart and Dorsal Muscles (tupHDME) CRM, which regulates tup transcription in the dorsal mesoderm. Comparison with the previously known CRMs, tupF4 and tupADME [10, 34], using detailed transcriptional analyses with endogenous and reporter intronic probes shows that each CRM displays a specific timing of activity during dorsal muscle development. Both tupHDME and tupADME control tup transcription in dorsal muscles beyond the FC step. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of either CRM individually did not result in significant disruption of muscle tup expression, whereas deletion of both supressed tup transcription at late stages of muscle development (stages 14–16). This, at least partial, CRM redundancy suggests that robust tup function is key in specifying skeletal muscle identities.

The redundancy and robustness of tup regulation via multiple CRMs could be part of a more general mechanism of transcriptional control during muscle development. Other transcription factors, either “generic”, such as Mef2 (Nguyen and Xu, 1998; Sandmann et al., [29], or specific to a subset of skeletal muscles (iTFs) like Collier [22];) are regulated by multiple CRMs working sequentially or/and synergistically during muscle development, an evolutionary strategy for ensuring a precise level of expression across different stages of development [28]; Kvon et al., 2021). This could be part of a general mechanism for robustness of integrating generic and identity aspects of muscle development (Bataille et al., 2017). In case of tup, each of skeletal muscle CRM is also active in other mesodermal derivatives which differ between CRMs. An evolutionarily selection of this combinatorial set up could be essential to coordinate development of a stereotypical muscle pattern and development of the heart and associated tissues, the cardiac outflow, valves cells, AMs and lymph gland [11, 34, 41]; Meyer et al., 2023).

Autoregulation of tup expression in dorsal muscles

Interestingly, the deletion of the early-active tupF4 CRM did not abolish tup transcription or perturb dorsal muscle patterning, suggesting that tup transcription at the PMC stage is not critical for dorsal muscle identity. Moreover, since tupHDME activity, which overlaps with tupF4 at the PC stage, remains unaffected by tupF4 deletion, this rules out a simple handover mechanism initiating tupHDME autoregulation. One possible explanation is that the same upstream transcription factors (TFs) or chromatin-opening factors bind to both tupF4 and tupHDME, but at different times or concentrations, with tupHDME maintaining tup transcription via its direct autoregulatory sites (Fig. 2). On support of this, Chip-SEQ analyses have shown Tin binding to both tupF4 and tupHDME in 4–6 h embryos, Twi sequentially binds to tupF4 and tupADME in 2–4 and 6–8 h embryos, respectively and Mef2 sequentially binds to tupF4 and tupADME in 4–6 and 6–12 h embryos, respectively [40]; Philippakis et al., 2013; http://furlonglab.embl.de/tissue_specific_DHS). We attempted to confirm these observations by generating a double CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of tupF4 and tupHDME, but for technical reasons, we were unable to collect double mutant individuals.

This is not the first occurrence where deletion of a CRM driving iTF expression in PMCs does not lead to muscle patterning defects. Similar results were indeed observed in studying the respective roles of early (PMC) and late (FC/muscle) col CRMs. In this case as well, the early CRM was not required to prime autoregulation [13]. This raises important questions about the specific role of early-active CRMs in muscle identity specification within specific subsets of muscle, while highlighting the pivotal role of late-active CRMs via autoregulation in maintaining and propagating muscle identity. Whether there is a specific role of iTFs expression in PMC prior to the process of PC/FC identity specification remains to be fully elucidated. Our results support a model of muscle identity specification that progressively refined at each stage of muscle development - PMC to PC, PC to FC, and FC to syncytial fiber - through distinct CRM activities. This temporal refinement through separate regulatory elements may ensure that muscle identity is established and maintained through each critical step of muscle development.

Sustained tup transcription in dorsal muscles is dependent on a positive autoregulatory mechanism exerted on both tupADME [10] and tupHDME (Fig. 2). Yet, while tupHDME deleted of its Tup binding sites is inactive in dorsal muscles, it remains active in heart cells or the lymph gland, indicating a tissue specific autoregulation. tup autoregulation mediated by tupADME is also skeletal muscle-specific and is not exerted in AMs. In turn, tupHDME, is not active in AMs, consistent with the absence of Org-1/Tbx1 binding sites which directly control tupADME activity in these peculiar heart-associated muscles [10]. Other transcription factors may regulate tup expression in cardiac cells or the lymph gland, including Tinman, Twist, and/or Bagpipe [2, 30, 40]. Future understanding of the regulatory roles of other TF binding motifs present within combinations of tup enhancers and enhancer-promoter interactions will certainly benefit from newly developed technologies such as Quantitative enhancer-FACS-Seq analysis [36] and Capture-C in purified myogenic cells [26].

Impact of tup transcription loss on muscle patterning and alignment

Previous analysis of tup null (tupex4) embryos, using a DA3 muscle marker Collier, revealed a DA2-to-DA3 (DA2 > DA3) identity shift. tupex4 embryonic lethality, including germ band retraction defects, precluded, however detailing this identity shift at the morphological level [10]. Expression of the VgM1-moeGFP reporter in double tupCRM mutants allowed to visualise the DA2 > DA3 transformation in fully developed embryos (Fig. 5A).

In wild-type embryos and larvae, the DA2 muscle of segment Sn aligns with the DA3 muscle of Sn−1 and the DA1 muscle of segment Sn+1, at intersegmental borders (Fig. 5A; Carayon et al., [13]. However, in the double tupADME and tupHDME deletion mutants, this DA3-DA2, DA2-DA1 intersegmental matching is often replaced by homotypic alignment between DA2 muscles in consecutive segments (Fig. 5A, B). Residual heterotypic matching could possibly reflect either the late timing of loss of tup transcription, in other terms, residual expression driven by tupF4 or/and the involvement of other iTFs expressed in DA muscles FCs (Dubois et al., 2017). DA muscle mismatching at intersegmental borders persists until the end of larval development (Fig. 6A, B), confirming that the specific morphology of somatic muscles at work in larval crawling, which includes muscle growth, elongation and choice of tendon and/or muscle attachment sites, reflects the combination of iTFs expressed by muscle FCs in early embryos.

The DA3-DA2-DA1 misalignments mirror those observed in collier (col) muscle CRMs mutants, which show a DA3-to-DA2 identity shift with DA3-DA3 homotypic matching replacing DA3-DA2 matching at intersegmental segmental borders [13]. The similarity of the symmetrically opposite tup and col dorsal muscle phenotypes shows that the col > tup transcriptional regulation which ensures that Tup is expressed in the DA2 FC and Col in the DA3 FC [10], is critical for the proper alignment and orientation of dorsal muscles and larval locomotion. The defects observed in ΔtupADME + HDME mutants further underscore the importance of coordinated CRM activity in establishing a stereotypical muscle pattern, with in the case of tup, tupADME and tupHDME redundant function ensuring robustness to this pattern.

Interestingly, we observe that DA1 and DA2 muscles are differentially affected in ΔtupADME + HDME mutants. While DA1 defects appear more frequent, the heterogeneity of the phenotype complicates direct comparison. The differential sensitivity of DA1 and DA2 may reflect both the complexity of dorsal muscle patterning and the influence of developmental time. Early Tup expression driven by the tupF4 enhancer—active in DA2 but not in DA1 progenitors—may allow DA2 to “secure” its identity before late enhancer activity becomes necessary. This hypothesis is consistent with our earlier findings that developmental time (i.e. the relative amount of iTFs) is a key factor in muscle identity specification [3, 10, 21].

Our analysis focused on DA1 and DA2 muscles. The DO1 and DO2 muscles are more difficult to visualize with confidence, in current absence of specific markers and their anatomical position beneath internal muscles makes them hard to access in larval fillets. This technical limitation precluded a systematic analysis. Yet, occasional observations revealed only mild and infrequent defects of DO muscles in ΔtupADME + HDME mutants, suggesting that their morphology relies on other regulatory inputs and/or is less sensitive than internal muscles to modifying Tup dosage and timing of expression.

Conclusions

The involvement of multiple CRMs for precise tup regulation in skeletal muscles, similar to previously reported for col, another TF critical for muscle identity and optimal larval locomotion [13, 20, 22] supports that temporal cascade strategies provide robustness to transcription control of muscle identity, and resilience of species-specific muscle patterns against genetic or environmental perturbations. Future work should investigate the physiological consequences of muscle mismatching observed in tup mutants. Additionally, exploring the interaction of tup with other muscle-specific transcription factors and their associated CRMs may uncover further complexities in the regulatory networks that govern muscle identity and development.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the tupF4 Cis-Regulatory Module. The tupF4 sequence was annotated using EvoPrinter, a comparative genomics tool designed to identify conserved DNA sequences shared among several orthologous DNAs. Black capital letters represent bases in the Drosophila melanogaster reference sequence that are conserved in the orthologous sequences of other Drosophila species: D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. pseudoobscura, and D. persimilis. Transcription factor binding sites were predicted using the JASPAR core database, an open-access resource of curated, non-redundant transcription factor binding profiles. Binding sites for Org-1 (blue) and Tin (grey) are highlighted. The blue box indicates a cluster of mesodermal transcription factor binding sites identified in previous ChIP-seq experiments (ChIP Tinman and ChIP Meso TFs). The coordinates of the tupF4 cis-regulatory module (CRM) are chr2L:18892809–18894301 (FlyBase release: r6.53). The nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used to amplify the tupF4 CRM are underlined in red.

Supplementary Material 2: conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the TupADME Cis-Regulatory module. The tupADME sequence was annotated as indicated in Fig.S1. Binding sites for Org-1 (blue), Tup/Islet-1 (yellow), Mef2 (purple), and Twist (green) are highlighted. The coordinates of the tupADME cis-regulatory module (CRM) are chr2L:18899345–18900688 (FlyBase release: r6.53). The nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used to amplify the tupADME CRM are underlined in red.

Supplementary Material 3: Expression of GMR 76E06 and GMR 76E11 delineate a new tup cis-regulatory module (A) GMR 76E06 and 76E11 expression during embryonic stages 11 to 16 (nuclear LacZ immunostaining). Both GMRs are expressed in the heart and dorsal muscles. At stage 16, GMR 76E06 is expressed in the DA1/DO1 and DA2/DO2 muscles, while GMR 76E11 expression is restricted to DA1/DO1 (white box). Scale bar: 1 cm = 100 μm. (B) GMR 76E06 and 76E11 sequences partly overlap. The newly identified CRM TupHDME (in red) spans this overlap and the predicted binding sites for the transcription factors Tup/Islet-1 (Tup) and Tinman (Tin).

Supplementary Material 4: conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the tuphdme Cis-Regulatory module. The tupHDME sequence was annotated as indicated in Fig.S1. Binding sites for Tup/Islet-1 (yellow) and Tin (grey) binding sites are highligthed. A cluster of binding sites for mesodermal transcription factors, determined by previous ChIP-seq experiments (ChIP Tinman and ChIP Meso TFs), is indicated by the blue box. The coordinates of the tupHDME-CRM are chr2L:18905826–18907523 (FlyBase release: r6.53). Nucleotide sequences of the PCR primers used to amplify the tupHDME CRM are underlined in red. The primer used to delete the three Tup binding sites and generate the tupHDMEΔTup construct for autoregulation experiments (see Fig. 2A) is underlined in grey.

Supplementary Material 5: combinatorial activity of the three tup CRMs in different mesodermal cell derivatives (A) Dorsal view of the expression patterns of tupF4-moeGFP, tupADME-moeGFP and TupHDME-moeGFP CRMs in late embryos (st 16) immunostained with an anti-GFP antibody. Depending on the CRM observed, expression is detected in the pharyngeal muscles (pm), alary muscles (AM), and the lymph gland (LG) (top pannels), in cardiac cells (CC) or pericardiac cells (pc) (bottom pannels). Scale bar: 1.5 cm = 50 μm. (B) The table summarizes the expression of tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME in mesodermal tissues during the embryonic development (from stage 13 to stage 16) as indicated by a green tick.

Supplementary Material 6: Autoregulation by Tup maintains tupADME and tupHDME activity in dorsal muscles. tupF4 (A), tupADME (B) and tupHDME (C) LacZ reporter expression in wild-type (+) and tupex4 mutant embryos lacking Tup protein visualized by in situ hybridization using a LacZ probe. (A) tupF4-LacZ activity in promuscular clusters and progenitor cells is independent of Tup. (B-C) Both activity of tupADME (B) and tupHDME (C) is lost in dorsal muscles in tupex4 mutant embryos, showing that Tup is required. Scale bar: 1 cm = 100 μm.

Supplementary Material 7: tup transcription during embryonic development. tup transcription revealed by in situ hybridization (green signal) in stage 10 to 16 embryos immuno-stained for Krüppel (Kr), blue, which labels amniosera cells (amn), and the dorsal muscles DA1 and DO1 in addition to lateral (LM) muscle lineages. tup is transcribed in amn, cardiac cells (cc), pericardial cells (pc), dorsal muscles (DM), and alary muscles (AM) up to stage 14, before being restricted to cc and pc cells and AMs, stage 16. Kr is initially expressed in the amniosera at stage 10, followed by expression in DA1 and DO1 progenitor cells at stages 11–12. Later in development, Kr expression is restricted to the trachea (tr). Scale bar: 0.7 cm = 50 μm. The bottom panels are enlarged views of the yellow framed regions, designated A, B and C. Scale bar: 1.7 cm = 50 μm. (A, B) At stages 12 (A) and 13 (B), tup is transcribed (green dots) in the nuclei of the DA1 and DO1 founder cells identified by Kr expression and the AM founder cell. (C) At stage 14, multiple nuclei of the DA1 and DO1 (and AM) developing muscles actively transcribe tup.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Alain Vincent, whose initiative led to this project. They are grateful for his unwavering commitment, valuable assistance in writing and proofreading, and insightful advice and discussions.

We thank the Bloomington Stock Center and the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center for Drosophila strains, and Julien Favier, Drosophila embryos microinjection platform from the Center of Integrative Biology in Toulouse– France.

Abbreviations

- CRM

Cis-Regulatory Module

- iTFs

Identity Transcription Factors

- FC

Founder Cell

- FCM

Fusion-Competent Myoblast

- PMCs

Promuscular Clusters

- PCs

Progenitor Cells

- tup

Tailup (also known as Islet1 in vertebrates)

- tupex4

tup mutant allele

- Mef2

Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2

- Col

Collier

- Tin

Tinman

- Twi

Twist

- DA

Dorsal Acute Muscles

- DO

Dorsal Oblique Muscle 1

- HDME

Heart and Dorsal Muscles Enhancer

- ADME

Alary and Dorsal Muscles Enhancer

- AMs

Alary Muscles

- CRISPR-Cas9

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and Caspase 9-associated protein

- gRNA

Guide RNA (used for CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing)

- ChIP-Seq

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing

Author contributions

J-L.F managed the project. L.D and J-L.F conceptualized and designed the experiments. A.P, A.C, Y.C, L.D and J-L.F performed the experiments. A.P, Y.C, L.D, C.S and J-L.F analysed the data and prepared the figures for the manuscript. J-L.F wrote the manuscript with input from co-authors.

Funding

This work was supported by CNRS, Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM) Research Grant 21887, ANR grant 13-BSVE2-0010-01.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Andersson R, Sandelin A. Determinants of enhancer and promoter activities of regulatory elements. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21:71–87. 10.1038/s41576-019-0173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azpiazu N, Frasch M. Tinman and bagpipe: two homeobox genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–40. 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bataillé L, Boukhatmi H, Frendo JL, Vincent A. Dynamics of transcriptional (re)-programming of syncytial nuclei in developing muscles. BMC Biol. 2017;15:48. 10.1186/s12915-017-0386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bataillé L, Delon I, Da Ponte JP, Brown NH, Jagla K. Downstream of identity genes: muscle-type-specific regulation of the fusion process. Dev Cell. 2010;19:317–28. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bate M. The embryonic development of larval muscles in drosophila. Development. 1990;110:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baylies MK, Bate M, Ruiz Gomez M. Myogenesis: a view from drosophila. Cell. 1998;93:921–7. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckett K, Baylies MK. 3D analysis of founder cell and fusion competent myoblast arrangements outlines a new model of myoblast fusion. Dev Biol. 2007;309:113–25. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonn S, Zinzen RP, Girardot C, Gustafson EH, Perez-Gonzalez A, Delhomme N, Ghavi-Helm Y, Wilczyński B, Riddell A, Furlong EE. Tissue-specific analysis of chromatin state identifies Temporal signatures of enhancer activity during embryonic development. Nat Genet. 2012;44:148–56. 10.1038/ng.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bothma JP, Garcia HG, Ng S, Perry MW, Gregor T, Levine M. Enhancer additivity and non-additivity are determined by enhancer strength in the drosophila embryo. Elife. 2015;4:e07956. 10.7554/eLife.07956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boukhatmi H, Frendo JL, Enriquez J, Crozatier M, Dubois L, Vincent A. Tup/Islet1 integrates time and position to specify muscle identity in drosophila. Development. 2012;139:3572–82. 10.1242/dev.083410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boukhatmi H, Schaub C, Bataillé L, Reim I, Frendo JL, Frasch M, Vincent A. An Org-1-Tup transcriptional cascade reveals different types of alary muscles connecting internal organs in drosophila. Development. 2014;141:3761–71. 10.1242/dev.111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannavò E, Khoueiry P, Garfield DA, Geeleher P, Zichner T, Gustafson EH, Ciglar L, Korbel JO, Furlong EE. Shadow enhancers are pervasive features of developmental regulatory networks. Curr Biol. 2015;26:38–51. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carayon A, Bataillé L, Lebreton G, Dubois L, Pelletier A, Carrier Y, Wystrach A, Vincent A, Frendo JL. Intrinsic control of muscle attachment sites matching. Elife. 2020;9:e57547. 10.7554/eLife.57547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmena A, Gisselbrecht S, Harrison J, Jiménez F, Michelson AM. Combinatorial signaling codes for the progressive determination of cell fates in the drosophila embryonic mesoderm. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3910–22. 10.1101/gad.12.24.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmena A, Buff E, Halfon MS, Gisselbrecht S, Jiménez F, Baylies MK, Michelson AM. Reciprocal regulatory interactions between the Notch and Ras signaling pathways in the drosophila embryonic mesoderm. Dev Biol. 2002;244:226–42. 10.1006/dbio.2002.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crozatier M, Vincent A. Requirement for the drosophila COE transcription factor collier in formation of an embryonic muscle: transcriptional response to Notch signaling. Development. 1999;126:1495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Joussineau C, Bataillé L, Jagla T, Jagla K. Diversification of muscle types in drosophila: upstream and downstream of identity genes. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;98:277–301. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386499-4.00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng S, Azevedo M, Baylies M. Acting on identity: myoblast fusion and the formation of the syncytial muscle fiber. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;72:45–55. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobi KC, Schulman VK, Baylies MK. Specification of the somatic musculature in drosophila. Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:357–75. 10.1002/wdev.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois L, Enriquez J, Daburon V, Crozet F, Lebreton G, Crozatier M, Vincent A. Collier transcription in a single drosophila muscle lineage: the combinatorial control of muscle identity. Development. 2007;134:4347–55. 10.1242/dev.008409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois L, Frendo JL, Chanut-Delalande H, Crozatier M, Vincent A. Genetic dissection of the transcription factor code controlling serial specification of muscle identities in drosophila. Elife. 2016;5:e14979. 10.7554/eLife.14979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enriquez J, de Taffin M, Crozatier M, Vincent A, Dubois L. Combinatorial coding of drosophila muscle shape by collier and nautilus. Dev Biol. 2012;363:27–39. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Field A, Adelman K. Evaluating enhancer function and transcription. Annu Rev Biochem. 2020;89:213–34. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-011420-095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furlong EE, Levine M. Developmental enhancers and chromosome topology. Science. 2018;361:1341–5. 10.1126/science.aau0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gratz SJ, Ukken FP, Rubinstein CD, Thiede G, Donohue LK, Cummings AM, O’Connor-Giles KM. Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in drosophila. Genetics. 2014;196:961–71. 10.1534/genetics.113.160713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollex T, Rabinowitz A, Gambetta MC, Marco-Ferreres R, Viales RR, Jankowski A, Schaub C, Furlong EEM. Enhancer-promoter interactions become more instructive in the transition from cell-fate specification to tissue differentiation. Nat Genet. 2024;56:686–96. 10.1038/s41588-024-01678-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized crispr/cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2967–76. 10.1073/pnas.1405500111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddington JP, Garfield DA, Sigalova OM, Karabacak Calviello A, Marco-Ferreres R, Girardot C, Viales RR, Degner JF, Ohler U, Furlong EEM. Lineage-Resolved enhancer and promoter usage during a time course of embryogenesis. Dev Cell. 2020. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandmann T, Girardot C, Brehme M, Tongprasit W, Stolc V, Furlong EE. A core transcriptional network for early mesoderm development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 2007;21:436–49. 10.1101/gad.1509007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandmann T, Jensen LJ, Jakobsen JS, Karzynski MM, Eichenlaub MP, Bork P, Furlong EE. A Temporal map of transcription factor activity: mef2 directly regulates target genes at all stages of muscle development. Dev Cell. 2006;10:797–807. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenfelder S, Fraser P. Long-range enhancer-promoter contacts in gene expression control. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:437–55. 10.1038/s41576-019-0128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shlyueva D, Stampfel G, Stark A. Transcriptional enhancers: from properties to genome-wide predictions. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:272–86. 10.1038/nrg3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Small S, Arnosti DN. Transcriptional enhancers in Drosophila. Genetics. 2020;216:1–26. 10.1534/genetics.120.301370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao Y, Wang J, Tokusumi T, Gajewski K, Schulz RA. Requirement of the LIM homeodomain transcription factor tailup for normal heart and hematopoietic organ formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3962–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visel A, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. Genomic views of distant-acting enhancers. Nature. 2009;461:199–205. 10.1038/nature08451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waters CT, Gisselbrecht SS, Sytnikova YA, Cafarelli TM, Hill DE, Bulyk ML. Quantitative-enhancer-FACS-seq (QeFS) reveals epistatic interactions among motifs within transcriptional enhancers in developing Drosophila tissue. Genome Biol. 2021;22:348. 10.1186/s13059-021-02574-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitney PH, Shrestha B, Xiong J, Zhang T, Rushlow CA. Shadow enhancers modulate distinct transcriptional parameters that differentially affect downstream patterning events. Development. 2022;149:dev200940. 10.1242/dev.200940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yalgin C, Karim MR, Moore AW. Immunohistological labeling of microtubules in sensory neuron dendrites, tracheae, and muscles in the Drosophila larva body wall. J Vis Exp. 2011;10:3662. 10.3791/3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeitlinger J, Zinzen RP, Stark A, Kellis M, Zhang H, Young RA, Levine M. Whole-genome ChIP-chip analysis of dorsal, twist, and snail suggests integration of diverse patterning processes in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2007;21:385–90. 10.1101/gad.1509607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zinzen RP, Girardot C, Gagneur J, Braun M, Furlong EE. Combinatorial binding predicts spatio-temporal cis-regulatory activity. Nature. 2009;462:65–70. 10.1038/nature08531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zmojdzian M, Jagla K. Tailup plays multiple roles during cardiac outflow assembly in Drosophila. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:639–45. 10.1007/s00441-013-1644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the tupF4 Cis-Regulatory Module. The tupF4 sequence was annotated using EvoPrinter, a comparative genomics tool designed to identify conserved DNA sequences shared among several orthologous DNAs. Black capital letters represent bases in the Drosophila melanogaster reference sequence that are conserved in the orthologous sequences of other Drosophila species: D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. pseudoobscura, and D. persimilis. Transcription factor binding sites were predicted using the JASPAR core database, an open-access resource of curated, non-redundant transcription factor binding profiles. Binding sites for Org-1 (blue) and Tin (grey) are highlighted. The blue box indicates a cluster of mesodermal transcription factor binding sites identified in previous ChIP-seq experiments (ChIP Tinman and ChIP Meso TFs). The coordinates of the tupF4 cis-regulatory module (CRM) are chr2L:18892809–18894301 (FlyBase release: r6.53). The nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used to amplify the tupF4 CRM are underlined in red.

Supplementary Material 2: conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the TupADME Cis-Regulatory module. The tupADME sequence was annotated as indicated in Fig.S1. Binding sites for Org-1 (blue), Tup/Islet-1 (yellow), Mef2 (purple), and Twist (green) are highlighted. The coordinates of the tupADME cis-regulatory module (CRM) are chr2L:18899345–18900688 (FlyBase release: r6.53). The nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used to amplify the tupADME CRM are underlined in red.

Supplementary Material 3: Expression of GMR 76E06 and GMR 76E11 delineate a new tup cis-regulatory module (A) GMR 76E06 and 76E11 expression during embryonic stages 11 to 16 (nuclear LacZ immunostaining). Both GMRs are expressed in the heart and dorsal muscles. At stage 16, GMR 76E06 is expressed in the DA1/DO1 and DA2/DO2 muscles, while GMR 76E11 expression is restricted to DA1/DO1 (white box). Scale bar: 1 cm = 100 μm. (B) GMR 76E06 and 76E11 sequences partly overlap. The newly identified CRM TupHDME (in red) spans this overlap and the predicted binding sites for the transcription factors Tup/Islet-1 (Tup) and Tinman (Tin).

Supplementary Material 4: conserved sequences and transcription factor binding sites in the tuphdme Cis-Regulatory module. The tupHDME sequence was annotated as indicated in Fig.S1. Binding sites for Tup/Islet-1 (yellow) and Tin (grey) binding sites are highligthed. A cluster of binding sites for mesodermal transcription factors, determined by previous ChIP-seq experiments (ChIP Tinman and ChIP Meso TFs), is indicated by the blue box. The coordinates of the tupHDME-CRM are chr2L:18905826–18907523 (FlyBase release: r6.53). Nucleotide sequences of the PCR primers used to amplify the tupHDME CRM are underlined in red. The primer used to delete the three Tup binding sites and generate the tupHDMEΔTup construct for autoregulation experiments (see Fig. 2A) is underlined in grey.

Supplementary Material 5: combinatorial activity of the three tup CRMs in different mesodermal cell derivatives (A) Dorsal view of the expression patterns of tupF4-moeGFP, tupADME-moeGFP and TupHDME-moeGFP CRMs in late embryos (st 16) immunostained with an anti-GFP antibody. Depending on the CRM observed, expression is detected in the pharyngeal muscles (pm), alary muscles (AM), and the lymph gland (LG) (top pannels), in cardiac cells (CC) or pericardiac cells (pc) (bottom pannels). Scale bar: 1.5 cm = 50 μm. (B) The table summarizes the expression of tupF4, tupADME and tupHDME in mesodermal tissues during the embryonic development (from stage 13 to stage 16) as indicated by a green tick.

Supplementary Material 6: Autoregulation by Tup maintains tupADME and tupHDME activity in dorsal muscles. tupF4 (A), tupADME (B) and tupHDME (C) LacZ reporter expression in wild-type (+) and tupex4 mutant embryos lacking Tup protein visualized by in situ hybridization using a LacZ probe. (A) tupF4-LacZ activity in promuscular clusters and progenitor cells is independent of Tup. (B-C) Both activity of tupADME (B) and tupHDME (C) is lost in dorsal muscles in tupex4 mutant embryos, showing that Tup is required. Scale bar: 1 cm = 100 μm.

Supplementary Material 7: tup transcription during embryonic development. tup transcription revealed by in situ hybridization (green signal) in stage 10 to 16 embryos immuno-stained for Krüppel (Kr), blue, which labels amniosera cells (amn), and the dorsal muscles DA1 and DO1 in addition to lateral (LM) muscle lineages. tup is transcribed in amn, cardiac cells (cc), pericardial cells (pc), dorsal muscles (DM), and alary muscles (AM) up to stage 14, before being restricted to cc and pc cells and AMs, stage 16. Kr is initially expressed in the amniosera at stage 10, followed by expression in DA1 and DO1 progenitor cells at stages 11–12. Later in development, Kr expression is restricted to the trachea (tr). Scale bar: 0.7 cm = 50 μm. The bottom panels are enlarged views of the yellow framed regions, designated A, B and C. Scale bar: 1.7 cm = 50 μm. (A, B) At stages 12 (A) and 13 (B), tup is transcribed (green dots) in the nuclei of the DA1 and DO1 founder cells identified by Kr expression and the AM founder cell. (C) At stage 14, multiple nuclei of the DA1 and DO1 (and AM) developing muscles actively transcribe tup.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.