Abstract

Thrombotic diseases pose life-threatening risks, yet current thrombolytic therapies face limitations including poor targeting and bleeding risks. To address this, ultrasound-activatable nanomotors (hBT-Pt@Pm) were developed through the integration of hollow BaTiO₃/Pt Schottky heterojunctions with platelet membrane (Pm) coatings. The hollow structure enhances piezocatalytic efficiency by shortening charge migration distances, while Pt deposition improves carrier separation, collectively boosting reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation under ultrasound. Finite element simulations confirmed a 5.8-fold increase in piezoelectric potential compared to solid BaTiO₃. Asymmetric Pt caps enable cavitation-driven thrombus penetration, and Pt-mediated H₂O₂ decomposition generates O₂ bubbles to amplify ROS production. In vitro, Pm coating conferred 5.2-fold higher thrombus accumulation than non-targeted nanoparticles. In murine venous thrombosis models, the nanomotors achieved near-complete clot dissolution via synergistic piezocatalysis and mechanical penetration, without systemic toxicity. This approach provides a targeted, ultrasound-powered alternative to conventional thrombolytics, combining precision therapy with inherent biosafety.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03675-6.

Keywords: H2O2-responsiveness, Piezocatalysis therapy, Panomotor penetration, Schottky heterojunction, Target thrombolysis

Introduction

Abnormal coagulation within blood vessels initiates the formation of thrombi, which ultimately cause life-threatening cardiovascular diseases, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke [1]. Clinical interventions are essential for restoring blood supply through the thrombus removal and blood vessel recanalization approach. The predominant strategies for thrombus removal include mechanical thrombectomy and percutaneous intracavitary coronary angioplasty, nonetheless, they are invasive, potentially damaging, and/or prone to thrombosis recurrence [2]. In current clinical practice, the foremost strategies for treating thrombosis mainly involve drug thrombolysis, including streptokinase, urokinase and urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Nevertheless, these thrombolytic agents have drawbacks such as short half-life, lack of thrombus-targeting capacity, limited therapeutic window, and risk of bleeding [3]. Thrombolytic agents have been incorporated into nano-carriers that are specifically designed to respond to thrombus-associated biomarkers, such as low pH levels, elevated thrombin concentrations, and H2O2.This targeted delivery and stimuli-triggered release of anticoagulants enhance treatment efficacy to a certain extent. The primary limitation of current drug delivery carriers is the lack of effective penetration into thrombi, often resulting in thrombolytic drugs merely accumulating on the thrombus surface. Consequently, enhancing the penetration and retention of these agents within the clots is essential to accelerate thrombolysis and improve overall efficacy.

Micromotors, possessing efficient cargo-towing and self-propelling capabilities, are excellent candidates for delivering thrombolytic agents into thrombi. Their propulsion can be derived from self-consumption (e.g., Mg or Zn reacting to produce gas bubbles), enzymatic decomposition of substrates (e.g., H₂O₂ or urea), or external stimuli (e.g., magnetic fields or ultrasound) [4]. Magnetic-field-driven nanomotors represent another frontier in self-propelled thrombolysis [5]. Magnetic soft robots (e.g., helical microcatheters and colloidal microrobots) enable precise navigation through complex vasculature under external fields, achieving mechanical disruption and retrieval of clots without systemic drug exposure [6]. These advances highlight the potential of magnetic actuation in overcoming anatomical accessibility limits and reducing bleeding risks. Nevertheless, magnetically powered carriers face significant limitations, including complex operation and poor feasibility for practical motion control [4]. Alternatively, ultrasound is already established as a noninvasive clinical imaging tool, often utilizing microbubbles for enhancement [7]. This highlights the necessity to develop ultrasound-driven micromotors capable of thrombus penetration, enabling ultrasonication-promoted thrombolysis.

Considering drug based thrombolysis remain several challenges, including low drug payload capacity, suboptimal local release, and persistent bleeding risk. In recent years, non-pharmacological thrombolytic strategies that exploit photo/acoustic kinetic methods to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) have garnered increasing attention [8]. The piezoelectric materials, upon receiving ultrasonic irradiation, induce dipole displacement and spontaneous polarization through electron-hole separation, enabling these charge carriers to react with environmental molecules (O₂/H₂O) to generate various ROS species. These ROS exert thrombolytic effects by specifically disrupting three key structural components within the fibrin matrix: polypeptide linkages, N-linked biantennary glycan regions, and non-covalent interactions, thereby effectively preventing secondary embolism [9]. This new approach, namely ultrasound-activated piezoelectroacoustic dynamic therapy (PEDT), has demonstrated significant potential for non-pharmacological thrombolysis [8]. However, PEDT efficacy is constrained by inherent limitations of piezoelectric materials, including insufficient catalytic active sites and rapid charge recombination kinetics. Various strategies, including surface engineering, dopant incorporation, and morphology modulation, have been explored to augment piezocatalytic performance. Among these, hollow-structured nanomaterials have emerged as particularly promising due to their large specific surface area, porous architecture providing abundant accessible catalytic sites, and exceptional flexibility enabling substantial ultrasonic-induced deformation [10].

These distinctive characteristics collectively contribute to enhanced piezocatalytic activity. Tetragonal barium titanate (BT), a classical piezoelectric/ferroelectric material, has been used for piezoelectric therapy due to its biocompatibility and high piezoelectric coefficient [11]. However, the narrow bandgap of BT often leads to rapid recombination of photoinduced electron-hole pairs, significantly limiting ROS production efficiency. To our knowledge, heterojunction semiconductor nanomaterials demonstrate superior performance through built-in potential barriers that effectively suppress charge carrier recombination during ultrasonic excitation. The combination of noble metal with semiconductors emerges as a highly promising approach to boost the ROS generation. The formation of Schottky barrier could enhance the separation of charge carriers by the built-in electric field. Heterostructures have been intensively studied for applications in the field of energy conversion. In the biomedical field, the research on heterojunctions mainly focuses on anti-tumor and bacteria eradication [12]. For instance, Cai et al. constructed a sonosensitizer based on a piezoelectric metal-organic framework, which achieved remarkable antitumor efficacy [13]. These advancements have demonstrated the promise of piezoelectrics/metal heterostructures for effective piezoelectric-catalyzed therapy. However, hollow piezoelectrics/metal Schottky heterojunctions remain unexplored in thrombus therapy.

Conventional drug delivery systems inevitably trigger immune clearance mechanisms or enhance the retention effect via the reticuloendothelial system and bioadhesion, ultimately resulting in reduced therapeutic efficacy and detrimental toxic side effects [14]. Inherently involved in thrombus formation, platelets possess unique characteristics of thrombus homing [15]. Nanoparticles (NPs) coated with platelet membrane (Pm) not only inherit the natural target recognition capabilities of platelets but also showcase unique biological functionalities, such as immunosuppressive effects and extended circulation half-lives [16]. This is attributed to the presence of biomolecules, including proteins, antigens, and immunoglobulins, that are anchored to the Pm [17]. Nie et al. reported that NPs cloaked with Pm-and conjugated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) can selectively bind to activated platelets, rather than inactivated ones, effectively recruiting the NPs into the thrombus to fulfill the function of tPA [18]. Therefore, the Pm coating approach emerges as a promising targeting strategy for thrombosis therapy.

Herein, the Janus type nanomotor was developed by hollow BT (hBT) and Pt for thrombus targeting and PEDT therapy. As shown in Scheme 1, hBT NPs were synthesized using the template method, followed by sputtering coating of Pt caps to create Janus hBT-Pt heterojunctions. Subsequently, these Janus particles were coated with Pm to obtain hBT-Pt@Pm nanomotors. Upon intravenous administration, hBT-Pt@Pm execute a three-stage therapeutic cascade: (1) thrombus homing, (2) deep thrombus penetration, and (3) PEDT activation. The Pm biomimetic coating first mediates thrombus-targeted accumulation through GPIIb/IIIa receptor recognition. Subsequently, under ultrasonic irradiation, the asymmetric distribution of Pt on the hBT-Pt@Pm nanomotors generates localized microbubble implosion and cavitation effects to enhance thrombus penetration. During this process, ultrasound not only triggers the dissociation of the Pm coating but also induces electron-hole pair separation in hBT, while the hBT-Pt Schottky heterojunction facilitates electron transfer to the Pt layer, effectively suppressing electron-hole recombination and thereby improving piezocatalytic efficiency. Furthermore, the hollow architecture of hBT-Pt provides abundant reactive active sites and undergoes substantial deformation under ultrasonic irradiation to shorten charge migration distances, synergistically enhancing the piezocatalytic performance. Simultaneously, platinum catalyzes H₂O₂ decomposition at the thrombus site to generate O2, both ameliorating the hypoxic microenvironment and promoting ROS production. These coordinated effects ultimately amplify the thrombolytic efficacy mediated by PEDT.

Scheme 1.

The fabrication process and underlying piezothrombolysis mechanism of hBT-Pt@Pm

Experimental section

Materials

Tetraethyl orthosilicate, titanium isopropoxide (TTIP), Ba(OH)2•8 H2O, methylene blue (MB) nafion solution, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), terephthalic acid (TA), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium, L-α-phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, BCA protein assay kit, dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), and FITC were obtained from Aladdin Reagents Company (Shanghai, China). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) stainning reagents are purchased from Solarbio science & technology Co. Ltd (Beijing, China). Calcein-AM/PI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Thrombin was purchased from Shanghai Source Leaf Biotech. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from Kelong Regents Company (Chengdu, China) unless otherwise indicated.

Preparation of Pm

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of China and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chengdu Medical College. Briefly, whole blood was collected from healthy Sprague-Dawley rats (~ 250 g, provided by Sichuan Dashuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) to harvest Platelet-rich plasma (PRP). 10 mL blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min. Subsequently, the upper plasma layer was extracted and centrifuged again at 3000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting pellet was alternately frozen and thawed between room temperature and − 80 °C, then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm to obtain Pm [19].

Preparation of hBT NPs

Briefly, 4.33 mL of tetraethyl orthosilicate was added dropwise into 50 mL of a mixed solution of water/ammonia (28%)/ethyl alcohol (13/17/70, v/v/v), and reacted at 60 ℃ for 4 h to acquire SiO2 NPs. The fabricated SiO2 NPs were mixed in 24 mL of ethanol/acetonitrile (3/1, v/v), followed reacting with 3.6 mL of TTIP at 5 °C for 6 h to obtain TiO2-coated SiO2 NPs, which were then dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol/Ba(OH)2 (0.05 M) solutions (2/3, v/v). The mixture was autoclaved at 160 °C for 6 h, followed by sequential ethanol washing, overnight vacuum drying, and calcination at 900 °C for 3 h to yield hBT NPs. Moreover, for comparison purposes, BT NPs were synthesized as follows: 2 g of Ba(OH)2·8H2O (6 mmol) and 2 mL of TBOT were dispersed in 30 mL of H2O with vigorous stirring for 10 min. The mixture was transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 180 °C for 12 h. Following the reaction, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature in air, and the product was calcined at 900 °C for 3 h [10].

Preparation of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

The hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were fabricated by coating Pm onto hBT-Pt NPs, which were synthesized via sputter-coating Pt caps onto hBT NPs (Scheme 1). Briefly, hBT NPs (1 mg) were ultrasonicated in 10 mL ethanol for 5 min, followed by spin-coating the resulting suspension onto pre-cleaned glass substrates. A Pt layer was then deposited onto the half side of the hBT NPs by an e-beam evaporator to obtain Janus hBT-Pt NPs [20]. For Pm coating, hBT-Pt (1 mg) was added into 200 µL of Pm suspension under ultrasonication for 10 min, followed by extruding through a polycarbonate membrane (0.45 μm poresize) for 10 times to obtain hBT-Pt@Pm. For fluorescent labeling, DiD (1 µg/mL) was added to the NPs suspension to prepare hBT-Pt@Pm/DiD NPs [21].

For contrast purpose, liposome-coated NPS were prepared by dissolving L-α-phosphatidylcholine (5 mg/mL), cholesterol (1.5 mg/mL), and DOPE (1.5 mg/mL) in 2 mL anhydrous chloroform. The solution underwent rotary evaporation at 45 °C to form a thin lipid film, which was subsequently hydrated with 4 mL PBS and probe-sonicated for 30 min [22]. The collected liposomes were combined with hBT-Pt (1 mg) and the mixture was extruded through a polycarbonate membrane, and then labeled with DiD to prepare hBT-Pt@Lip/DiD NPs as non-targeted control group.

Characterization of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

The morphological structure and crystal lattice spacing of the NPs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100 F, Japan) equipped with EDX for elemental mapping. To ascertain Pm content, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were extracted using RIPA lysate supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride protease inhibitor (1 mM). The total protein content in lysate was quantified using BCA kit by measuring the absorbance at 562 nm. The lysate was boiled for 10 min and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis (Bio-Rad PowerPac, USA), followed by performing Western blot analysis was used to detect whether major functional proteins (CD41, CD61) were preserved after platelet membrane coating while intracellar GAPDH and IL-1β were removed. The proteins were transferred to the PVDF membranes, and incubated with primary antibodies including CD41, and CD61, IL-1β, and GADPH (ProteinTech Group, Chicago, IL, USA). After incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, and the signals were detected using a Tanon 5200 system (Bio Tanon, Shanghai, China) [19]. The size and zeta potential of Pm, hBT, hBT-Pt and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyzer (Malvern Nano-ZS90, UK). The crystal phase of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs was analyzed by Raman spectroscopy (LabRAM HR Evolution, HORIBA, France) using a 532 nm laser at 5 mW power (10% attenuation), with 10 s exposure time per accumulation. Phase composition was further characterized by X-ray diffractometry (XRD, Philips X’Pert PRO, Netherlands) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) at 40 kV/40 mA, scanning from 10° to 90° (2θ) at 5°/min with a 0.1° step size. The surface properties and elemental composition were examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific Escalab 250Xi, USA) employing monochromatic Al Kα excitation, and pass energies of 50 eV (survey) and 20 eV (high-resolution). The high-resolution scans used a 0.1 eV step size with charge compensation by flood gun, and all spectra were calibrated to C 1 s at 284.8 eV. The hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was incubated with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 7 days to evaluate its long-term stability.

The O2 generation of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was examined after incubation with H2O2 (200 µM), using alone hBT-Pt@Pm NPs, H2O2 (200 µM) and PBS as controls. Briefly, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (10 mg) were incubation with H2O2 (200 µM) in a thermostated shaker at 37 °C, using PBS, H2O2 (200 µM) and hBT-Pt@Pm groups as controls. At predetermined point, the O2 levels was monitored through a dissolved oxygen meter (JPBJ-608, Shanghai REX Instrument, China) [4].

Piezoelectric properties of NPs

Piezoelectric potential simulations for BT, hBT and hBT-Pt NPs were performed using the finite element method in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.6 [10]. Briefly, A 260 nm diameter hollow sphere model was established with material parameters assigned from the built-in library. The NPs polarization orientation was set al.ong the global z-axis, with the central plane fixed perpendicular to this axis and electrically grounded. Acoustic pressure simulation (10⁵–10⁸ Pa) enabled piezoelectric potential mapping through PARDISO solver analysis [10]. Moreover, experimental verification was conducted via piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM, Bruker MultiMode 8) to quantify nanoscale piezoelectric responses.

First-principles calculation of hBT-Pt NPs

Density functional theory (DFT) was employed to simulate the density of states (DOS), Electron location function (ELF), and differential charge density of hBT and hBT@Pt. The simulations were carried out using CASTEP software, which is based on the plane-wave basis sets with the projector augmented-wave method [10]. The exchange-correlation potential was treated with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation. To avoid interactions between adjacent images, a vacuum region of approximately 18 Å was set. The parameters used included a plane-wave basis set with a k point of 111 and a cut-off energy of 500 eV. The atomic structures were fully relaxed until the maximum force on each atom was less than 0.02 eV Å−1, and the energy convergence criterion was set at 10−5 eV. Subsequently, the Crystal orbital hamilton populations (COHP) was calculated through post-processing of Quantum ESPRESSO output using Lobster software. Finally, the ELF and differential charge density of the structure were mapped with VESTA [23]. The adsorption energy (Ead) was defined as the following equation: Ead= Etot– (Esub+ Emol).

where Etot, Esub, and Emol, were depicted as the total energy of the model, the catalytic substrate, and individual small molecule, respectively.

Electrochemical characterization of NPs

UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra of the NPs were recorded using a Hitachi U-4100 spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere, while absorption profiles were recorded with a UV-Vis spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-3600, Japan). The bandgap energies were determined by double-beam UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra (Shimadzu UV-3600i Plus, Japan) using BaSO4 as the reference. Photoluminescence spectra of NPs were acquired by fluorescence spectrophotometry (Hitachi F-7000, Japan) at the excitation wavelength of 250 nm. Electrochemical properties of NPs were carried out using a three-electrode quartz cells on the electrochemical system (CHI-660B, China), using 0.5 M of Na2SO4 solution (pH = 7.0) as the electrolyte, Pt plate as the counter electrode and Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode. The working electrode was fabricated by vortex-mixing 10 mg NPs in 2 mL anhydrous ethanol containing 0.25 wt% Nafion (100 µL), spin-coated onto 1 × 1 cm² indium tin oxide (ITO) glass, and air-dried [24].

Piezocatalytic activities of NPs

To evaluate the piezocatalytic activities of hBT-Pt@Pm/US, the generation of ROS including •OH and •O2− subpopulations was measured, with hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt@Pm, and PBS serving as controls. All experiments were conducted in the dark at 25 °C in a water bath to exclude photolysis and thermocatalysis effects. Briefly, NPs (1 mg) were mixed with 5 mL of MB solution (5 µg/mL) under ultrasonic condition for 10 min (1.5 W/cm2, 1 MHz). The centrifuged supernatants were analyzed via UV-vis spectroscopy (λ = 664 nm) to determine the ROS-mediated methylene blue degradation efficiency [25]. The ultrasound power (0–1.5 W/cm2, 1 MHz), and NPs (0-1 mg/mL) dosage for different time are also studied to determine ROS regulation effect. To detect •OH generation, NPs (200 µg/mL) were dispersed in 5 mL of TA (0.25 mM), and ultrasonication for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity of the supernatant was determined by fluorescence spectrophotometry (Hitachi F-7000, Japan) at the emission wavelength of 430 nm to detect •OH generation. To measure the generation of •O2−, 1 mL of NPs suspension (200 µg/mL) was mixed with 5 mL of NBT solution (20 µM), followed by ultrasonication for 10 min. The absorptions at 259 nm were recorded by UV-Vis spectrophotometry to examine •O2− productions [9]. ESR spectroscopy (Bruker E500, USA) was employed to verify radical generation, using 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) and 2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-4-piperidinol (TEMP) as •OH and •O2− spin traps, respectively [26].

Cytotoxicity and hemocompatibility of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

The cytocompatibility of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs and ultrasonication was estimated on macrophages (RAW 264.7) and Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) by using MTT method [27]. HUVEC and RAW 264.7 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). Briefly, HUVEC or RAW 264.7 were seeded overnight in 96-well tissue culture plate (TCP) at 1 × 104 cells/well, and then treated with NPs up to 1 mg/mL for 24 h, using alone 10 min of ultrasonication (1.5 W/cm2, 1 MHz) as controls. The treated cells were incubated with 10 µL of CCK8 solution (5.0 mg/mL) for 4 h, followed by adding 200 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide to dissolve the formazan crystals, and then the absorbance quantified at 570 nm using a BioTek ELx800 microplate reader [28]. For live/dead staining, NP-treated cells were co-stained with calcein AM and propidium iodide (PI) for 5 min in the dark, then examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX53, Japan) [29].

The hemocompatibility of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was estimated on RBC and platelets in terms of hemolysis, platelet activation and platelet aggregation assay. Briefly, Sprague-Dawley rats (~ 250 g) were purchased from Sichuan Dashuo Biotech. (Chengdu, China), and fresh bloods were harvested. PRP was collected from fresh blood through centrifugation at 2000 rpm, and RBC were retrieved from the remaining blood through centrifugation at 3000 rpm. Then 200 µL of fresh RBCs or PRP were incubated with 1.3 mL of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs suspensions up to 1.0 mg/mL at 37 °C for 3 h, using alone 10 min of ultrasonication (1.5 W/cm2, 1 MHz) as controls. The hemoglobin release from supernatant was detected by monitoring the absorbance at 540 nm, and the hemolysis rate was examined through comparing with the hemoglobin levels released in the water (positive control) [4]. The platelet aggregation rate was assessed from the absorbance of PRP at 650 nm, in comparison to those after thrombin/CaCl2 (positive control) and PBS treatments (negative control) [9]. To determine platelet activation, platelets were stained with FITC-conjugated CD41 antibody (2.5 µg/mL, BioLegend, CA, USA) for 20 min, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6, USA).

Targeting capability of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Briefly, Fibrin clot formation was induced in 96-well TCP plates by combining 120 µL fibrinogen (3 mg/mL) with 10 µL thrombin (10 U/mL). After adding 150 µL 50% serum and blocking at 4 °C for 30 min to prevent nonspecific binding [17], the wells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with 80 µL DiD-labeled hBT-Pt@Pm or hBT-Pt@Lip NPs (in 50% serum) at 4 °C for 2 h (PBS as negative control). NPs targeting was visualized by CLSM. For platelet-rich thrombus binding assays, PRP (150 µL), thrombin solution (30 µL, 3 U/mL) and CaCl2 solution (10 µL, 0.5 mol/L) were mixed in 96-well TCP, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 5 min. After blocking with 4% BSA for 1 h, 80 µL FITC-labeled NPs were added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Following PBS washes, thrombi were dissolved in 150 µL dmethyl sulfoxide for fluorescence intensity measurement.

For study of activated HUVEC binding ability, cells were seeded in 12-wells TCP (1 × 105 cells), with the activated group treated with TNF-α (50 ng/mL) for 24 h [17]. Both activated and inactivated HUVEC cells underwent sequential 4% paraformaldehyde fixation, 20% mouse serum blocking for 30 min and incubation with DiD-labeled hBT-Pt@Pm or hBT-Pt@Lip NPs. After incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, the cells were washed with cold PBS to remove unbounded NPs. Data were collected using a flow cytometry. For fluorescence microscopy imaging, the cells in 96-well TPC were stained with DAPI, and the binding of NPs to HUVEC was observed using CLSM.

Motion and thrombus penetration of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Agarose gels (1.5%) were prepared at 120 °C to simulate thrombus matrix for analyzing hBT-Pt@Pm/US motion profiles, with hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and PBS serving as controls [27]. After cooling to 60 °C, 0.5 mL agarose was mixed with DiD-labeled NPs (0.5 mg/mL) and transferred to 6-well TCPs for solidification. Then 2.5 mL agarose was added as an upper layer and solidified at room temperature. Under ultrasonication, NP distribution in the upper gel was imaged using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX83, Japan).

Thrombus penetration ability of hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT-Pt@Pm/US were examined in a capillary with filled whole blood clots [27]. Briefly, 1 mL of whole blood was collected from Sprague-Dawley rats and added with 500 µL of thrombin solution (1000 U/mL). A capillary (0.9 mm in diameter) was inserted vertically into the blood and then placed at 37 °C for 3 h to form thrombus. NPs (0.5 mg/mL) were dispersed in PBS and then injected into the capillary, and ultrasonication was performed for 5 min. After incubation for 3 h, the penetration depth of NPs in capillary tubes was measured by a vernier caliper.

Degradation of fibrin and blood clots by hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Fibrin clot degradation of hBT-Pt@Pm/US effect was assesed in vitro, using hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and PBS as controls. Briefly, FITC-labeled fibrin clots were prepared by combining 450 µL fibrinogen (1 mg/mL), 50 µL FITC (1 mg/mL), 50 µL thrombin (25 U/mL), and 50 µL CaCl₂ (25 mM) for 2 h at 37 °C. Resulting clots were treated with 0.3 mL NP suspensions in PBS under 5-min ultrasonication, followed by 4-hour incubation at 37 °C. Fluorescence imaging quantified clot degradation through FITC signal analysis. 0.3 mL of NPs (5 mg) were dispersed in PBS and then incubated with aboved FITC-labeled fibrin clots, followed by ultrasonication for 5 min. Fluorescence images of fibrin clots were captured to observe the clot degradation [4]. For blood clot thrombolysis assays, whole blood (50 µL) was mixed with 25 µL thrombin (1000 U/mL) at 37 °C for 1 h. The blood clots were incubated with 0.5 mL of NPs suspensions in PBS, followed by ultrasonication for 5 min. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, 100 µL of the supernatants were withdrawn to measure the absorbance at 576 nm by a microplate reader. In the meantime, the hemoglobin and fibrin contents in the media was measured from absorbance at 540 and 340 nm by a microplate reader [9].

In vivo thrombus imaging and thrombolysis of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Thrombus imaging and thrombolytic efficacy were evaluated in a rat lower-limb venous thrombosis model using fluorescence imaging, laser speckle analysis, and histology. Briefly, Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg), and the lower limb hair was shaved off and the exposed vein wraped with FeCl3 solution (10%) for thrombus formation. The surgical site underwent saline irrigation followed by suture closure to complete the thrombosis model establishment [27]. The thrombi-bearing rats were intravenously injected with DiD-labeled hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (5 mg/kg), and then imaged using an IVIS spectrum imaging system (PerkinElmer Inc., USA). 1 and 24 h. The tissues were homogenized in PBS, and the NPs content in the supernatant was measured based on fluorescence intensity [9]. The NPs distribution in tissue was determined from the ratio of the actual level in the tissue to the injected amount and normalized to the tissue weight (ID%/g).

To assess the thrombolysis efficacy, thrombus-bearing rats were intravenously administered with different NPs (5 mg/kg). After treatment for 24 h, laser speckle imaging of the lower limb vein was performed using a laser speckle contrast imaging system (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen) [30]. Then, the rats were sacrificed, and the lower limb veins were excised and fixed in paraformaldehyde solution (4%). The samples were processed into sections and stained with H&E and MSB to analyze thrombus morphology and fibrin content [31]. To evaluate treatment safety, blood samples were collected from the tail vein for hematological analysis 24 h after NP treatment. Additionally, major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were harvested 7 days after NP treatment for histopathological analysis via H&E staining.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA (multiple comparisons) or two-tailed Student’s t-test (two groups), with p < 0.05 indicating significance.

Results and discussion

Characterization of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

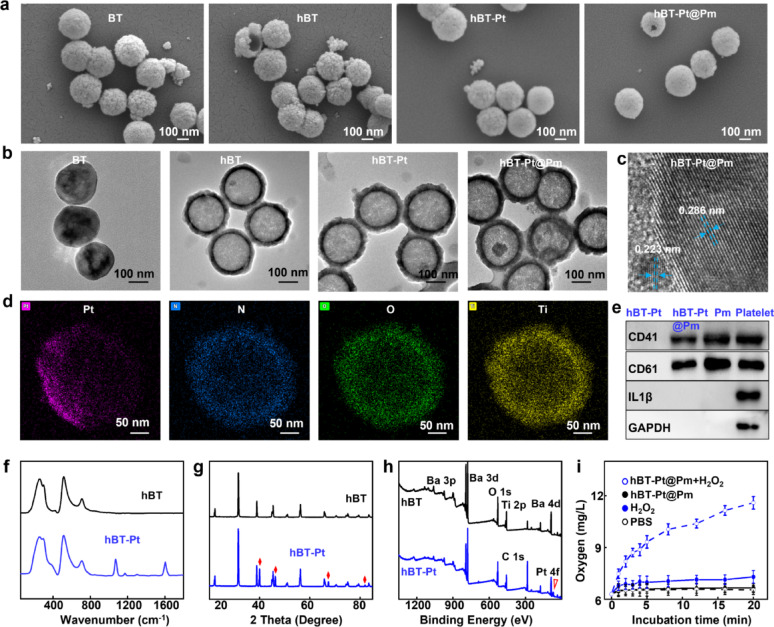

Figure 1a presented SEM images of BT, hBT, hBT-Pt, and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. hBT NPs exhibited an average diameter of 240 nm, featuring a hollow structure and rough surface. For comparison, BT NPs were prepared from Ba(OH)2•8H2O and TTIP and showed an average size of 245 nm. The deposition of Pt layer changed the diameter to 260 nm, and Pm coating decreased the rough surface with a diameter of 270 nm. Figure 1b displayed the TEM images of BT, hBT, hBT-Pt, and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs, clearly showing that hBT NPs possessed a hollow structure with diameter of 240 nm. Pt layer was distinctly deposited on one side of the hBT-Pt NPs, with average size slightly increased to ~ 260 nm. Furthermore, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs exhibited a well-defined core-shell structure with a uniform Pm coating approximately 7 nm thick, confirming the successful functionalization with Pm. The high-resolution TEM images clearly demonstrated high crystallinity and well-defined lattice structures within the hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (Fig. 1c). The interplanar spacings were measured as 0.286 nm for the (110) planes of hBT and 0.223 nm for the (111) planes of the Pt layer [10]. As shown in Fig. S1a, the hydrodynamic diameter of Pm was 245 nm with polydispersity index (PDI) at 0.13. The diameter of hBT NPs was approximately 250 nm, which increased to approximately 275 (hBT-Pt) and 290 nm (hBT-Pt@Pm) after Pt deposition and Pm coating. The PDI of hBT, hBT-Pt and hBT-Pt@Pm are 0.15, 0.16 and 0.18, respectively. In addition, compared to the zeta potential of hBT NPs (−7.8 mV), both Pt deposition and subsequent Pm (−25.6 mV) coating significantly altered the zeta potential of hBT-Pt (−13.3 mV) and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (−21.6 mV) (Fig. S1b). Furthermore, the protein content of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was measured to be 38 µg/mg by performing BCA kit. The long-term stability of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was evaluated by incubating them in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 7 days. As shown in Fig. S1c, the particle size maintained stability over the duration of the study, with no significant agglomeration observed. These results demonstrate excellent colloidal stability and dispersion of the NPs, essential for their potential in vivo applications. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mapping demonstrated that the hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were composed of Pt, N, O, and Ti elements, with the Pt element displaying a pronounced unilateral distribution characteristic (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (a) SEM images and (b) TEM images of BT, hBT, hBT-Pt and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (c) High-resolution TEM image and (d) EDX elemental mapping of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (e) Western bolt analyses of CD41, CD61, IL1-β, and GAPDH expression in hBT-Pt, hBT-Pt@Pm, Pm and Platelet NPs. (f) Raman spectra of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (g) XRD patterns of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (h) Survey XPS spectra of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (i) O2 generation ability of hBt-Pt@Pm NPs after different treatment (n = 3)

Western blot was performed to analysis specific protein markers on the surface of the Pm-coated hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. As shown in Fig. 1e and Fig. S2, the major membrane adhesion-related Pm proteins, including CD41, and CD61, were all present on hBT-Pt@Pm, Pm, and platelet. CD41 and CD61 collectively form GPIIb/IIIa complex, which plays an important role in platelet adhesion and activation [32]. In contrast, platelet granules and cytoplasmic proteins (IL-1β and GAPDH) were not detected on hBT-Pt@Pm and Pm, suggesting that these intracellular components were removed from the Pm during the extraction (Fig. 1e). These results demonstrated that hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were successfully prepared by asymmetric deposition of Pt and Pm encapsulation, with the functional Pm protein profile retained.

The crystallographic structure of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs were investigated by Raman spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 1f, hBT NPs exhibited characteristic peaks at 258, 515, and 711 cm–1, which were consistent with the vibrational modes of tetragonal BaTiO3 [33]. In comparison to hBT NPs, hBT-Pt NPs displayed additional Raman peaks at 1075 and 1602 cm−1, which were attributed to the deposition of Pt onto the surface of hBT NPs. Figure 1g showed XRD patterns of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs, which matched to the tetragonal phase of BaTiO3 with noncentrosymmetric crystal structure (JCPDS card: 79–2263) [10]. Obvious secondary splits appeared in the (200)/(002) diffraction peak at 45°, indicating that both hBT and hBT-Pt NPs possessed a well-defined tetragonal phase structure. Furthermore, hBT-Pt NPs showed new diffraction peaks at 39.9°,46.3°, 67.4° and 87.9°, assigned to cubic crystal of Pt (JCPDS card: 04 − 0802) [34].

The surface elemental composition of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs were studied by XPS. As shown in Fig. 1h, the XPS survey scan results revealed that both hBT and hBT-Pt NPs contained Ba, Ti, and O elements. However, the Pt element was exclusively observed in hBT-Pt NPs. In addition, the C 1 s peaks were likely attributed to adventitious carbon present during the measurement process. Fig. S3 displays the XPS narrow-scan spectra, providing a detailed observation of the chemical states. Three O 1 s peaks were detected at 529.1, 531.7, and 532.9 eV, corresponding to Ba–O, C = O, and Ti–O bonds (Fig. S2a), respectively [35]. As shown in Fig. S2b, two peaks located at 793.6 eV and 777.8 eV can be assigned to the binding energy of Ba 3d3/2 and Ba 3d5/2, respectively [36]. Moreover, the doublet peaks at 70.3 eV and 73.9 eV in Fig. S2c were identified as metallic Pt0 (Pt 4f7/2 and Pt 4f5/2) [37]. Combining with the XRD pattern in Fig. 1g, these data confirmed the successful deposition of metallic Pt on hBT-Pt NPs. Figure 1i compares O2 concentrations after co-incubation of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs with H2O2 (200 µM), alongside control groups containing phosphate buffer solution (PBS), hBT-Pt@Pm, and H2O2. The O2 concentration in PBS was approximately 6.3 mg/L. No significant O2 generation was detected in hBT-Pt@Pm suspensions or in H2O2 solution. In contrast, hBT-Pt@Pm + H2O2 exhibited rapid O2 production (11.6 mg/mL), representing an 84% increase compared to PBS. This catalytic H2O2 decomposition in thrombotic microenvironments effectively alleviated hypoxic while enhancing piezoelectric-mediated thrombolysis.

Piezocatalytic performance of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Finite element method (FEM) analysis (COMSOL Multiphysics) was employed to quantify piezoelectric potential distributions in BT, hBT, and hBT-Pt NPs, validating the effects from both cavity engineering and Pt deposition. The NPs dimensions adopted in the models (diameter: 260 ± 15 nm) matched the actual values estimated in TEM (Fig. 1b), ensuring geometric accuracy in simulations.

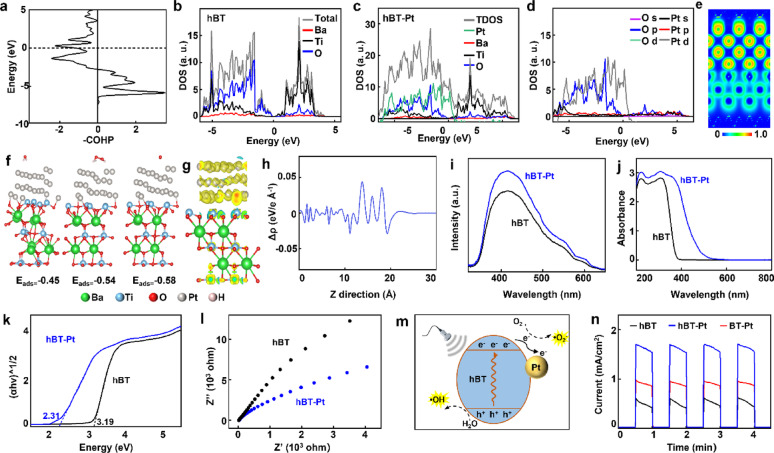

Surface piezoelectric potential conducted under an applied pressure of 108 Pa demonstrated a progressive increase from BT (0.19 V) to hBT (0.79 V) and Pt-modified hBT-Pt NPs (1.11 V), corresponding to enhancements of 3.15 times and 4.84 times, respectively (Fig. 2a). PFM measurement was further performed to investigate the effect of Pt deposition, and the different contrasts of the PFM phase and amplitude images represented the direction of ferroelectric polarization and the strength of piezoelectric response [38]. As shown in Fig. 2b, BT, hBT and hBT-Pt NPs exhibited a clear spheric morphology with a size of about 260 nm, consistent with TEM observations (Fig. 1b). Compared to BT and hBT, hBT-Pt NPs displayed sharper outlines in both amplitude images (Fig. 2c) and phase (Fig. 2d) and, aligning well with their morphology. These results confirmed that hBT-Pt NPs generated a stronger piezoelectric response than BT and hBT NPs under identical voltage. The characteristic butterfly loops exhibited maximum amplitudes of 1.71 nm (BT), 2.36 nm (hBT), and 2.62 nm (hBT-Pt), with corresponding 180° phase reversals confirming ferroelectric domain switching (Fig. 2e). These quantifiable enhancements in both strain-voltage response and polarization switching behavior provide conclusive evidence of the improved piezoelectric performance of hBT-Pt NPs.

Fig. 2.

Piezocatalytic performance of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (a) FEM simulation of piezopotential distribution of BT, hBT, and hBT-Pt NPs under ultrasound-driven cavitation pressures (105~108). (b) Topography image, (c) amplitude images and (d) phase images of BT, hBT, and hBT-Pt NPs. (e) Piezoelectric response amplitude curves (black) and phase curves (blue) of BT, hBT, and hBT-Pt NPs observed by PFM

Piezocatalytic mechanism of hBT-Pt NPs

To elucidate correlations between the inherent electronic configuration and catalytic activity, DFT calculations were performed. COHP analysis revealed bond formation between hBT and Pt in hBT-Pt NPs, as demonstrated by the integrated COHP below the Fermi level showing predominant positive contributions (Fig. 3a). Compared with those of hBT (Fig. 3b), the overlapped peaks in DOS indicated Pt-O interactions (Fig. 3c). Notably, significant overlap between O-p and Pt-d orbitals was observed within the − 5 to −2 eV energy range, suggesting orbital hybridization (Fig. 3d). ELF analysis further confirmed strong Pt-O interfacial interactions at the atomic scale (Fig. 3e) [39]. The energy of adsorption is calculated to be −0.45, −0.54 and − 0.58 eV for H2O, H2O2 and O2 molecules on hBT-Pt, respectively (Fig. 3f), indicating that the heterojunction of hBT-Pt with a hollow structure is more favorable for the adsorption and activation of H2O, H2O2 and O2 molecules, thus facilitating the generation of ROS.

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of the enhanced PEDT performance. (a) The partial COHP of Pt-O in hBT-Pt NPs. Density of states of (b) hBT, (c) hBT-P NPs. (d) The density of states of O and P in hBT-P NPs. (e) Side views of the electron localization function of hBT-Pt NPs. (f) Optimized adsorption energy for the H2O, H2O2, O2 on hBT-Pt NPs. (g) The differential charge density of hBT-Pt NPs. Blue represents electron dissipation, and yellow represents electron aggregation. (h) Plane-averaged charge density difference Δρ between hBT and Pt along the z-direction. (i) Photoluminescence spectra of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (j) The UV-vis absorbance spectra of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (k) Tauc plot of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs according to UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra. (l) Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of hBT and hBT-Pt NPs. (m) Schematic diagram of the piezoelectric effect of hBT-Pt mediated •OH and •O2− generation. (n) Ultrasonic current curves of hBT, BT-Pt, and hBT-Pt NPs

The formation of a Pt-O covalent bond likely facilitated charge transfer in the hBT-Pt heterojunction under ultrasound (Fig. 3g) [39]. As shown in Fig. 3h, the pronounced Δρ oscillation demonstrated substantial charge redistribution at the hBT-Pt interface. Differential charge density analysis further revealed electronic coupling and the charge-transfer direction from hBT to Pt at the interface. Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy was used to investigate the role of heterojunctions in photogenerated carrier separation efficiency [40]. As shown in Fig. 3i, the PL signals originated from the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers. Under 315 nm excitation, both hBT and hBT-Pt NPs showed characteristic emission peaks at ~ 415 nm, confirming consistent PL positions. The hBT-Pt NPs exhibited higher PL intensity than hBT, indicating reduced electron-hole recombination in the Pt-hBT heterojunction. This allowed more photogenerated carriers to form active hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (•O2−), thereby enhancing the photocatalytic activity of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. As shown in Fig. 3j, UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra revealed Pt-induced modifications in optical absorption. While hBT NPs had an absorption edge at 380 nm, hBT-Pt NPs displayed significantly enhanced visible-light absorption due to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of metallic Pt, where coherent electron oscillations amplified localized electromagnetic fields. Bandgap calculations using the Kubelka-Munk function yielded values of 3.19 eV (hBT) and 2.31 eV (hBT-Pt), confirming broader light utilization (Fig. 3k). Moreover, the charge transfer efficiency was further studied by the complementary transient piezocurrents and electrochemical impedance techniques. As shown in Fig. 3l, hBT-Pt demonstrated a smaller arc radius than hBT, consistent with PL results (Fig. 3i), indicating lower e⁻/h⁺ recombination and higher catalytic activity in hBT-Pt.

The hBT component of the hBT-Pt heterojunction generated piezoelectric-induced charge carriers under ultrasonic excitation. The interfacial charge redistribution was driven by the intrinsic Fermi level difference between metallic Pt and semiconductor BT, which facilitated Schottky barrier formation at the Pt/hBT interface (Fig. 3m). This barrier promoted effective electron-hole separation and directed the carriers toward the sample/solution interface, where they reacted with chemical species to produce •O₂⁻ and •OH radicals [41]. For current measurements, the hBT-Pt NPs coated ITO glass, platinum sheet (1 × 1 cm2) and saturated Ag/AgCl electrode were used as working, auxiliary and reference electrodes, respectively [10]. Under ultrasound, carrier separation occurred via the piezoelectric field, and the resulting current was measured using an electrochemical workstation. As shown in Fig. 3n, transient positive currents were observed during ultrasound application, with rapid signal decay upon cessation, confirming mechanical-to-electrical energy conversion. hBT-Pt exhibited the highest piezocurrent response and the output reached 1.68 mA/cm2, which was significantly higher than those of hBT and BT-Pt NPs, respectively.

ROS generation of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

The formation and rupture of ultrasonication cavitation bubble generated transient pressures ranging from 105 to 108 Pa [42]. The resulting deformation and macroscopic polarization induced piezoelectric responses. The piezoelectric potential facilitated redox reactions between surface carriers and environmental O2/H2O, producing ROS. The piezocatalytic performance of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was evaluated using methylene blue (MB, ROS indicator), nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, •O2− probe), and terephthalic acid (TA, •OH detector). As shown in Fig. 4a, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs without ultrasound showed only 8.6% MB absorbance reduction, confirming ultrasound dependence. Accordingly, BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT@Pm/US achieved 64.3% and 52.7% decreases respectively, while hBT-Pt@Pm/US demonstrated 87.2% MB degradation (Fig. 4b), highlighting synergistic enhancement from Pt deposition and hollow architecture. Nonfluorescent TA could be oxidized by •OH into highly fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid [43]. Figure 4c showed fluorescence spectra of TA solutions after different treatments. After PBS normalization, the fluorescence intensities were 6-fold (hBT-Pt@Pm), 26-fold (BT-Pt@Pm/US), 33-fold (hBT@Pm/US), and 59-fold (hBT-Pt@Pm/US) higher than PBS control (Fig. 4d), confirming enhanced piezocatalytic activity and Pt-mediated electron transfer. NBT reduction showed 259 nm absorbance decreases corresponding to •O2− production (Fig. 4e) [44]. Quantitative analysis (Fig. 4f) revealed conversion rates of 40.7% (BT-Pt@Pm/US), 49.5% (hBT@Pm/US), and 81.3% (hBT-Pt@Pm/US), versus 10.1% for non-sonicated hBT-Pt@Pm (p < 0.05). These results confirmed that hollow nanostructuring and Pt modification synergistically enhanced ultrasonic-driven piezoelectricity, significantly boosting the generation of •OH and •O2−.

Fig. 4.

In vitro assessments of ROS-generating ability. (a) UV–vis absorbance spectra of MB and (b) corresponding quantitative degermation (n = 3) under different treatments (1 PBS, 2 hBT-Pt@Pm, 3 BT-Pt@Pm/US, 4 hBT@Pm/US, 5 hBT-Pt@Pm/US). (c) Fluorescence spectra of TA for •OH evaluation and (d) the quantitative analysis after different treatments. (e) NBT for •O₂⁻ evaluation (f) and quantitative analysis (n = 3). (g) ESR signal of DMPO-•OH and (h) TEMP-•O₂⁻ after different treatments. Asterisk denotes statistical significance of indicated groups (***: p < 0.001)

Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy was performed to determine •OH and •O2− generation across different experimental groups. Spin-trap reagents of DMPO and TEMP were employed to capture •OH and •O2− species, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4g, there was negligible •OH signal in hBT-Pt@Pm and PBS groups, whereas distinct DMPO-•OH adduct signals appeared in BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT@Pm/US groups, conclusively demonstrating ultrasound activation of the catalytic process. The hBT-Pt@Pm/US system exhibited the strongest DMPO-•OH signal intensity, demonstrating optimal radical production. In addition, ESR spectra of TEMP-•O₂⁻ adducts (Fig. 4h) confirmed comparable activation behavior, with hBT-Pt@Pm/US exhibiting the most intense spin adduct signals under ultrasound. It should be noted that excessive ROS production may cause oxidative damage to normal tissues. Moreover, the nanomotor concentration (0–1 mg/mL) demonstrated dose-dependent ROS generation (Fig. S4a), allowing therapeutic tuning while maintaining safety thresholds. Fig. S4b showed ROS production scales with US intensity (0–2.0 W/cm²), enabling real-time ROS modulation by adjusting output power. These spectroscopic evidence correlated well with the dye degradation results and suggested that the piezoelectric internal field reduced the Schottky barrier, facilitating electron transfer from hBT to Pt while suppressing charge recombination.

In vitro cytotoxicity of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Comprehensive biocompatibility assessments (cellular and hematological) of the hBT-Pt@Pm NPs were systematically performed through cytotoxicity, hemolysis and platelet function assay. HUVEC and RAW 264.7 cell viability remained unaffected by hBT-Pt@Pm NPs at various concentrations or under ultrasound exposure (Fig. 5a). To visual the specific toxicity of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs, live/dead staining of HUVEC and RAW 264.7 cells was performed after NPs and ultrasound treatment in vitro [30]. As shown in Fig. S5, fluorescence imaging revealed comparable green (live cell) signals between treated groups and untreated controls.

Fig. 5.

In vitro cytotoxicity and thrombus targeting of hBT-Pt@Pm. (a) Relative cell viabilities of HUVEC and RAW 264.7 after treatment with hBT-Pt@Pm NPs after different teratment (n = 3). (b) Hemolysis rate and (c) platelet aggregation of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs after different teratment (n = 3). (d) The fluorescence intensity of fibrin clots after incubation with DiD-labled hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (n = 3). (e) Bright-field and fluorescence images of fibrin-coated substrates incubated with DiD-labled hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (f) Fluorescence intensity of PRP incubated with DiD-labled hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs (n = 3). (g) Flow cytometry profiles of inactivated and (h) activated HUVEC after treated by PBS, hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (i) CLSM co-localization images of NPs with and HUVECs. Asterisk denotes statistical significance of indicated groups (*: p < 0.05)

Hemolytic analysis (Fig. 5b) showed < 5% hemolysis across all NPs concentrations with or without ultrasound after red blood cell (RBC) incubation. PRP absorbance measurements indicated no significant platelet aggregation induced by NPs or ultrasound alone (Fig. 5c). Flow cytometry with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated CD41 antibody confirmed minimal platelet activation (Fig. S6), consistent with aggregation assay results. These findings validated the biocompatibility of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs, demonstrating no detectable toxicity to HUVEC, RAW 264.7, RBC, or platelets under experimental conditions.

In vitro evaluation of thrombus-targeting abilities

To investigate the thrombus-targeting ability of NPs, the binding affinity of NPs to fibrin clots, platelet-rich thrombi, and activated HUVEC was explored in vitro. Fibrin clots were prepared by thrombin-mediated polymerization of fibrinogen. After incubation with DiD-labeled NPs, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs showed significantly stronger fibrin binding than PBS and hBT-Pt@Lip groups (Fig. 5d). Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) further verified enhanced adhesion of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs to fibrin-coated substrates (Fig. 5e). The thrombus-targeting capability was further explored on PRP containing fibrin-platelet composites [45]. Comparative binding analysis revealed superior adhesion of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs to thrombi versus control groups (Fig. 5f). For endothelial interactions, baseline binding to inactivated HUVEC was comparable across groups (Fig. 5g). The flow cytometry results (Fig. 5h) and CLSM co-localization images (Fig. 5i) demonstrated significantly higher intracellular fluorescence intensity on activated HUVEC for hBT-Pt@Pm in activated HUVECs, indicating 2.1-fold greater adhesion than PBS and hBT-Pt@Lip controls. These results confirmed that hBT-Pt@Pm NPs possess optimal affinity for multiple thrombus components, suggesting their potential as targeted delivery systems for thrombolytic therapy.

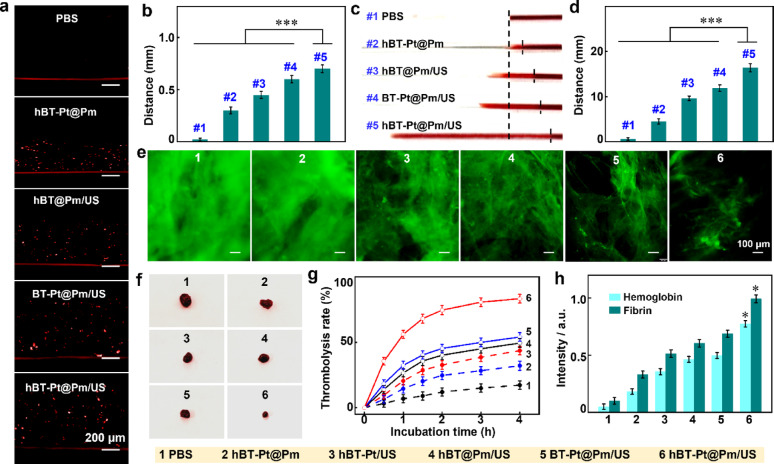

In vitro Ultrasound-activated thrombus penetration dynamics of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

The ultrasound-powered motion behavior of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs was investigated in agarose gels mimicking thrombus matrix [4]. A bilayer system was constructed by encapsulating DiD-labeled NPs in a bottom agarose layer covered with a pristine gel layer. Figure 6a demonstrated the penetration of fluorescent NPs from the bottom into the upper gel layers, with hBT-Pt@Pm/US showing significantly greater fluorescence penetration depth than other treatments. Figure 6b summarized the fluorescence tracking depths of hBT-Pt@Pm/US (~ 700 μm), BT-Pt@Pm/US (~ 600 μm), and hBT@Pm/US (~ 450 μm). This performance difference was attributed to the catalase-mimetic activity of Pt, which facilitates O2 generation. Under static conditions, the migration of hBT-Pt@Pm was limited to ~ 300 μm, underscoring the crucial role of ultrasound in activating asymmetric O2 production and cavitation-driven propulsion.

Fig. 6.

In vitro thrombus penetration and thrombolysis of of hBT-Pt@Pm/US. (a) Fluorescence images and (b) fluorescence depth of hBT-Pt@Pm/US penetration in agarose gels, by using PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT@Pm/US, and BT-Pt@Pm/US as control (n = 3). (c) Visual images and (d) penetration distance in the glass capillary from the top of original thrombi after different treatment (n = 3). (e) Fluorescence images of FITC-labeled fibrin clots after treatment with PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT-Pt@Pm/US (n = 3). (f) Visual images, (g) thrombolysis rates, and (h) hemoglobin and fibrin release levels from blood clots after treatment with PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT-Pt@Pm/US (n = 3). Asterisk denotes statistical significance of indicated groups (*: p < 0.05; ***: p < 0.001)

The thrombus penetration capability of NPs was evaluated in simulated capillary vessels through visual observation [4]. hBT-Pt@Pm/US exhibited significantly greater penetration than other groups (Fig. 6c). Pm functionalization enhanced thrombus targeting, while ultrasound amplified cavitation-induced propulsion forces [27, 45]. As shown in Fig. 6d, the penetration distance of hBT-Pt@Pm/US (16.4 mm) was significantly longer than that of hBT-Pt@Pm (4.5 mm) treatment. However, hBT@Pm/US showed a shorter penetration distance (9.6 mm) due to its lack of asymmetric structure. The hollow architecture of hBT reduces its mass by 80.5% compared to solid BT (calculated from TEM data in Fig. 1b). Lower mass enables greater acceleration under equivalent acoustic radiation forces, causing longer travel distance of hBT-Pt@Pm/US than hBT-Pt@Pm/US group. These results confirmed that ultrasound-driven asymmetric propulsion effectively enhances thrombus penetration.

In vitro thrombolysis of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Previous studies demonstrated that ROS could degrade phospholipids such as platelet factor 3, and destroy the fibrin skeleton [46]. In vitro thrombolysis capability of hBT-Pt@Pm/US was evaluated using blood clots and FITC-labeled fibrin clots, with fluorescence imaging quantifying structural degradation [46]. Figure 6e showed the fluorescent images of fibrin clots after treated with different NPs, there were still a large amount of FITC-labeled fibrin after treatment with hBT-Pt@Pm, indicating no significant fibrin degradation. hBT-Pt/US exhibited partial fluorescence attenuation. In comparison, hBT-Pt@Pm/US achieved superior degradation of the fibrin skeleton matrix, outperforming the hBT@Pm/US and BT-Pt@Pm/US systems, which exhibited lower piezocatalytic activity. Figure 6f displayed visual images of blood clots after treatment with different group for 4 h, and hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment caused much fewer clot residual compared to other treatments.

Quantitative analysis indicated thrombolysis rates of hBT-Pt@Pm (32.1%) was higher than that of PBS (17.3%), suggesting the catalase-like activity of Pt produced O2 bubbles to promote the penetration of NP and slight disruption of clots. Compared with those of hBT-Pt/US (43.6%), hBT@Pm/US (49.4%) and BT-Pt@Pm/US (54.1%), the thrombolysis efficiency reached 83.4% after hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment. This improved performance can be attributed to the synergistic effect of Pm targeting and ultrasound-activated piezocatalytic ROS generation (Fig. 6g). As shown in Fig. 6h, the hemoglobin release level after treatment with hBT-Pt@Pm/US (0.78) was significantly higher than those after BT-Pt@Pm/US (0.49), hBT@Pm/US (0.46), hBT-Pt/US (0.35) and hBT-Pt@Pm (0.18). Likewise, the fibrin release results following hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment was ~ 1.6 folds greater than that observed with hBT@Pm/US and BT-Pt@Pm/US (Fig. 6h). It was proposed the thrombolysis effect of hBT-Pt@Pm/US stemmed from the synergistic effect of Pm-directed targeting and ultrasound-induced piezocatalysis activity. Furthermore, it should be noted that the lifetime of ROS is merely ~ 10 µs, and the diffusion distance is limited to ~ 150 nm [47], thus minimizing the risk of ROS-induced damage to the vascular endothelium.

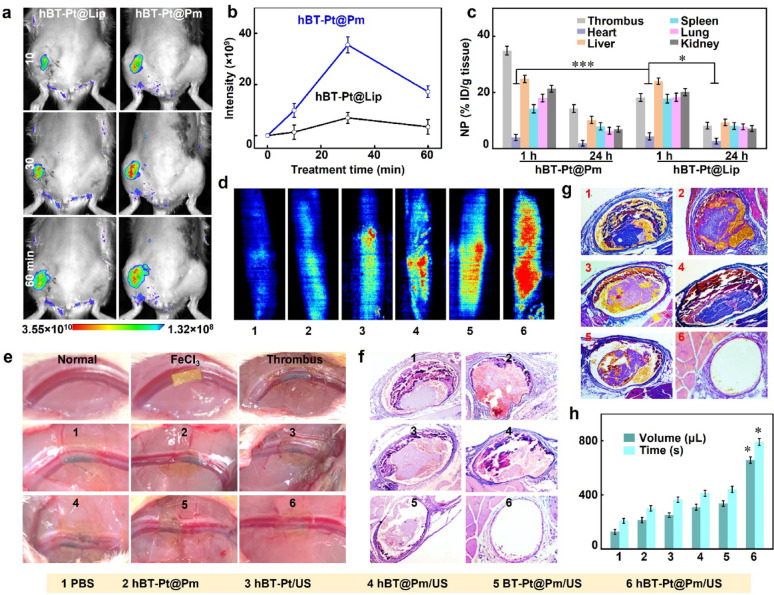

In vivo thrombolysis of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

A limb vein thrombosis model was established in Sprague-Dawley rats to evaluate the thrombus imaging and thrombolysis efficacy. Fluorescence imaging enabled real-time visualization of NPs biodistribution in vivo. As shown in Fig. 7a, fluorescence intensification in thrombotic zones (left limb vein) exhibited significant signal amplification in both the targeted hBT-Pt@Pm and the non-targeted hBT-Pt@Lip after intravenous injection of NPs for 60 min. However, hBT-Pt@Lip showed weaker signals, while hBT-Pt@Pm achieved peak thrombus accumulation within 30 min. Figure 7b showed the quantitatively compared thrombus-targeting efficiency through fluorescence intensity measurements. The hBT-Pt@Pm demonstrated 5.2-fold greater signal accumulation at thrombotic sites compared to hBT-Pt@Lip after 30 min, a disparity directly attributable to the thrombotic affinity of Pm [15]. Figure 7c summarized the pharmacokinetic profiles of NPs in major organs and thrombosed left limb veins at 1 h and 24 h post-injection. Both hBT-Pt@Pm and hBT-Pt@Lip groups exhibited comparable biodistribution patterns in vital organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys), with notable hepatic and renal accumulation observed at 1 h. Quantitative analysis revealed a 1.8-fold higher thrombus accumulation of hBT-Pt@Pm compared to hBT-Pt@Lip (p < 0.05), unequivocally demonstrating Pm-mediated targeting specificity. Although systemic clearance occurred by 24 h, hBT-Pt@Pm maintained significantly greater retention at thrombotic sites (p < 0.01), confirming the sustained targeting efficacy of Pm modification.

Fig. 7.

In vivo thrombus imaging and thrombolysis abilities of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. (a) Representative luminescence images and (b) luminescence intensity of limb vein thrombosis after intravenous injection of DiD-labled hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm NPs for 1 h (n = 5). (c) NPs distribution in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and thrombus after treatment with hBT-Pt@Lip and hBT-Pt@Pm for 1 and 24 h. (d) The laser speckle flow images of the blood flow of limb veins after treated by PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, BT-Pt@Pm/US and hBT-Pt@Pm/US for 24 h. (e) Visual images of thrombus formation after treatment with FeCl3-soaked filter paper on a normal vessel. (f) H&E and (g) MSB staining images of thrombi after treatment with different groups. (h) The quantitative analysis of the bleeding time and volume after 2 h of treatment with above 6 groups

The thrombolytic ability of hBT-Pt@Pm/US was evaluated through visual image, laser speckle imaging and histological measurements. The laser speckle flow imaging system could be utilized to visually monitor the blood flow of limb veins in rats [30]. As shown in Fig. 7d, hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment restored significant blood flow after 24 h compared to PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, and BT-Pt@Pm/US groups, demonstrating Pm-mediated thrombus targeting and ROS generation efficiency. As depicted in Fig. 7e, a filter paper soaked in FeCl3 solution was applied to the left limb vein, resulting in the clear visualization of thrombus within the vessel, thereby confirming the successful establishment of the thrombosis model. Following treatment with PBS and hBT-Pt@Pm, no significant alterations were observed in thrombus. However, after treatment with hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US and BT-Pt@Pm/US, a portion of the endovascular blackening disappeared. Notably, there was less residual black thrombus in the blood vessels following the hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment. Figure 7f showed the H&E stainning of left limb venous thrombosis after 24 h treatment. Significant thrombus remained in the vessels following hBT-Pt@Pm treatment. Partial thrombus dissolution occurred in hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, and BT-Pt@Pm/US treatment groups under ultrasonication irradiation. Notably, the image demonstrated near-complete elimination of the thrombus after a 24 h treatment with hBT-Pt@Pm/US. Histopathological images stained with MSB could be used to evaluate the morphology and composition of fibrin in thrombi, where erythrocytes appeared yellow, fibrins purple-red, and collagen blue [48]. As shown in Fig. 7g, there was no thrombus residue observed in the vascular lumen following hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment. In contrast, significant fibrin residue was present in the vascular lumen after treatment with PBS, hBT-Pt@Pm, hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, and BT-Pt@Pm/US. Experimental data demonstrated that the concurrent application of ultrasonication and Pt deposition collectively enhanced ROS production. ROS facilitated thrombus degradation through lipid peroxidation -mediated inhibition of platelet factor 3, oxidative fragmentation of cell membranes, and structural breakdown of fibrin skeleton within thrombi [46]. The ultrasound-activated hBT-Pt@Pm platform demonstrated significant thrombolytic potential, though clinical application faces challenges such as accessing deep vein thrombi shielded by tissue or bone. Critically, ultrasound penetration depth depends on operational parameters including intensity, focus geometry, beam uniformity, and transducer characteristics. Notably, high-intensity focused ultrasound has successfully treated thrombi beyond 10 cm depth [49], demonstrating considerable clinical potential of ultrasound-based therapies for deep-tissue thrombosis.

Next, the anti-hemostatic properties of hBT-Pt@Pm/US were evaluated using tail bleeding assay, a standardized method for assessing antithrombotic efficacy [46]. Figure 7h showed the bleeding time and volume, which were measured using truncation method after 2 h of treatment with different NPs. PBS-treated controls achieved hemostasis within 209 s (128 µL blood loss), confirming normal platelet function. hBT-Pt@Pm showed comparable parameters (302 s bleeding time; 213 µL volume) to baseline levels. Comparative analysis revealed no statistically significant variations in hemorrhage duration or blood loss volumes between hBT-Pt/US, hBT@Pm/US, and BT-Pt@Pm/US treatments (p > 0.05). Compared with PBS treatment, hBT-Pt@Pm/US treatment significantly prolonged the bleeding time (792 s) of rats and expanded the blood loss (658 µL), implying that hBT-Pt@Pm/US could target clots of truncation and generate peroxidation damage through piezocatalytic activity, and inhibit thrombus formation. Compared to conventional thrombolytic techniques, the hBT-Pt@Pm demonstrates superior efficacy to that of non-targeted piezocatalysis, enabled by synergistic ROS generation and mechanical penetration. To mitigate intrinsic limitations of piezoelectric materials (e.g., rapid charge recombination), the Schottky junctions facilitate electron transfer to Pt, suppress charge recombination, while the hollow architecture shortening charge migration distances and amplifying deformation-induced polarization. Additionally, the Pt-mediated H₂O₂ decomposition sustaining localized O₂ for ROS amplification (Fig. 1i). This engineering ensures repeatable performance, as validated by dose-controlled ROS generation across ultrasound parameters (Fig. S4) and reproducible thrombus penetration in vitro (Fig. 6). Thus, the PEDT system overcomes classical piezoelectric constraints while offering targeted, on-demand thrombolysis versus systemic pharmacologic.

Treatment safety of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs

Hematological and histopathological analyses were performed to evaluate the biosafety of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. Blood samples were collected 24 h after hBT-Pt@Pm treatment for complete blood count and biochemical tests. Rats treated with hBT-Pt@Pm displayed hematological parameters that were physiologically normal, as depicted in Fig. S7a. The RBC count was 6.2 × 1012/L), the white blood cell (WBC) count was 5.4 × 109/L, the platelet (PLT) count was 6.39 × 1011/L, and the hemoglobin (HGB) concentration was 1.25 × 102 g/L. These values were in line with the established reference ranges for healthy rats, namely, RBC (5.60–7.89 × 1012/L), WBC (2.9 −15.3 × 109/L), PLT (100 − 1610 × 109/L), and HGB (1.2–1.5 × 102 g/L). Differential analysis of WBCs in rats treated with hBT-Pt@Pm (Fig. S7b) revealed physiological distributions, namely, neutrophils (10.5%), monocytes (1.6%), and lymphocytes (87.9%). These percentages were consistent with the normal reference values when expressed as absolute counts, namely, neutrophils (7.3% −30.1%), monocytes (1.5% − 4.5%), and lymphocytes (63.7% − 90.1%). This indicates that the subpopulation of WBCs remained unaffected following NPs treatment. Biochemical studies (Fig. S7c) validated the physiological function markers in hBT-Pt@Pm-treated rats, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 47.1 U/L), aspartate transaminase (AST, 104 U/L), creatinine (CREA, 28.6 µmol/L), and urea (UREA, 5.3 mmol/L). These values aligned with established reference intervals, namely, ALT (20 − 61 U/L), AST (39 − 111 U/L), CRET (4.4 − 57 µmol/L), and UREA (2 − 7.7 mmol/L). These findings confirmed the absence of significant hepatorenal toxicity following hBT-Pt@Pm NPs treatment. As one of the typical perovskite based materials, barium titanate possesses remarkable dielectric properties and biocompatibility, rendering it invaluable for applications in nonlinear imaging, drug delivery, and implantable bioelectronic components [50]. Platinum-based NPs demonstrate precisely controllable parameters (size, morphology, structural architecture), enabling their broad application in electronic devices, sensing technologies, energy conversion and storage, biomedical systems, especially catalysis [51].

Figure S7d shows H&E staining images of the main tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) after hBT-Pt@Pm NPs treatment for 7 days. Compared with healthy rats, hBT-Pt@Pm NPs treatment had no significant features of damage, necrosis, or inflammatory. These observations confirm the absence of hematological toxicity and histopathologic abnormalities, collectively supporting the biosafety profile of hBT-Pt@Pm NPs. Nevertheless, the long-term biodistribution and chronic toxicity require further investigation in clinical therapeutic applications. Prior studies indicate BaTiO₃ is predominantly eliminated through fecal excretion, and no overt accumulative toxicity has been noted in short-term studies [52]. Similarly, metallic Pt(0) nanoparticles exhibit inert bioaccumulation, with a substantial decrease in content observed by 7 days [53]. Collectively, the engineered piezoelectric nanomotors demonstrate substantial potential for thrombolytic applications. The future development should prioritize optimizing target specificity, reducing production costs, and minimizing long-term biocompatibility concerns [50].

Conclusion

Ultrasound-responsive hBT-Pt@Pm nanomotors were successfully engineered by integrating hollow BaTiO₃/Pt Schottky heterojunctions with Pm coatings for precision thrombolysis. The hollow structure and Pt deposition synergistically enhanced piezocatalytic efficiency, achieving a 5.8-fold increase in surface potential compared to solid BT NPs, as confirmed by COMSOL simulations. Pm coating enabled 5.2-fold higher thrombus targeting than non-targeted analogs, while Pt-mediated H₂O₂ decomposition generated O₂ to propel nanomotor penetration. In vivo studies demonstrated near-complete clot dissolution and restored blood flow in rat venous thrombosis models via ultrasound-triggered ROS generation and mechanical penetration, without systemic toxicity. This approach offers a targeted, non-pharmacological alternative to conventional thrombolytics, combining high efficacy with inherent biosafety and real-time imaging capabilities. The study highlights the potential of piezoelectric nanomotors for clinical thrombolytic therapy.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2024NSFSC1972), the Health Commission of Sichuan Province Medical Science and Technology Program (24CXTD09), the Nuclear Medicine Science and Technology Innovation of China Nuclear Medicine (ZHYLZD2025012), the Open Project of Sichuan Clinical Research Center for Radiation and Therapy (2024ZX03).

Author contributions

Ye Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Jinchen He: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Yuxi Liu: Visualization. Hassna Soummane: Investigation. Pan Ran: Investigation. Qian Yang: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Xiaofang Gao: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Wenxiong Cao: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Long Zhao: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ye Zhao, Jinchen He and Yuxi Liu contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Xiaofang Gao, Email: Gaoxiaofang_gxf@163.com.

Wenxiong Cao, Email: 996838@hainanu.edu.cn.

Long Zhao, Email: longzhao@cmc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Stone J, Hangge P, Albadawi H, Wallace A, Shamoun F, Knuttien MG, Naidu S, Oklu R. Deep vein thrombosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and medical management. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7(Suppl):S276-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc R, Escalard S, Baharvadhat H, Desilles JP, Boisseau W, Fahed R, Redjem H, Ciccio G, Smajda S, Maier B, Delvoye F, Hebert S, Mazighi M, Piotin M. Recent advances in devices for mechanical thrombectomy. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Qu H, He Q, Gao L, Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Hou L. Thrombus-targeted nanoparticles for thrombin-triggered thrombolysis and local inflammatory microenvironment regulation. J Control Release. 2021;339:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao W, Liu Y, Ran P, He J, Xie S, Weng J, Li X. Ultrasound-propelled Janus rod-shaped micromotors for site-specific sonodynamic thrombolysis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:58411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Wang B, Chan KF, Song X, Wang Q, Ji F, Su L, Ip BYM, Ko H, Chiu PWY, Leung TWH, Zhang L. Rapid blood clot removal via remote delamination and magnetization of clot debris. Adv Sci. 2025;12: 2415305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Wang L, Xiang Y, Liao F, Li N, Wang J, Wu Q, Zhou C, Yang Y, Kou Y, Yang Y, Tang H, Zhou N, Wan C, Yin Z, Yang G, Tao G, Zang J. Magnetic soft microfiberbots for robotic embolization. sci Robot. 2024;9: eadh2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du F, Guo R, Feng Z, Wang Z, Xiang X, Zhu B, Rodriguez RD, Qiu L. Precision gas therapy by ultrasound-triggered for anticancer therapeutics. MedComm – Oncology. 2023;2: e27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu H, Xia L, Wang J, Huang X, Zhao Q, Song X, Hu L, Ren S, Lu C, Ren Y, Qian X, Feng W, Wang Z, Chen Y. Bionanoengineered 2D monoelemental selenene for piezothrombolysis. Biomaterials. 2024;305:122468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao W, Xie S, Liu Y, Ran P, Zhang Z, Fang Q, Li X. Shear Stress-Triggered theranostic nanoparticles for Piezoelectric-fenton-photodynamic thrombolysis and endogenous thrombus imaging. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:2312866. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei J, Xia J, Liu X, Ran P, Zhang G, Wang C, Li X. Hollow-structured BaTiO3 nanoparticles with cerium-regulated defect engineering to promote piezocatalytic antibacterial treatment. Appl Catal B. 2023;328: 122520. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei J, Zhang G, Xie S, Zhang Z, Gao T, Zhang M, Li X. Enhanced interfacial electric field of an s-scheme heterojunction by an ultrasonication-triggered piezoelectric effect for sonocatalytic therapy of bacterial infections. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64: e202500441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan C, Mao Z, Yuan X, Zhang H, Mei L, Ji X, Nanomedicine H. Adv Sci. 2022;9:e2105747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai L, Du J, Han F, Shi T, Zhang H, Lu Y, Long S, Sun W, Fan J, Peng X. Piezoelectric metal-organic frameworks based sonosensitizer for enhanced nanozyme catalytic and sonodynamic therapies. ACS Nano. 2023;17:7901–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su C, Liu Y, Li R, Wu W, Fawcett JP, Gu J. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the biomaterials used in nanocarrier drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu B, Victorelli F, Yuan Y, Shen Y, Hong H, Hou G, Liang S, Li Z, Li X, Yin X, Ren F, Li Y. Platelet membrane cloaked nanotubes to accelerate thrombolysis by thrombus clot-targeting and penetration. Small. 2023;19: e2205260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X, He T, Liang X, Xiang Z, Liu C, Zhou S, Luo R, Bai L, Kou X, Li X, Wu R, Gou X, Wu X, Huang D, Fu W, Li Y, Chen R, Xu N, Wang Y, Le H, Chen T, Xu Y, Tang Y, Gong C. Advances and applications of nanoparticles in cancer therapy. MedComm – Oncology. 2024;3: e67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Wang R, Meng N, Guo H, Wu S, Wang X, Li J, Wang H, Jiang K, Xie C, Liu Y, Wang H, Lu W. Platelet membrane-functionalized nanoparticles with improved targeting ability and lower hemorrhagic risk for thrombolysis therapy. J Control Release. 2020;328:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Zhang Y, Xu J, Liu G, Di C, Zhao X, Li X, Li Y, Pang N, Yang C, Li Y, Li B, Lu Z, Wang M, Dai K, Yan R, Li S, Nie G. Engineered nanoplatelets for targeted delivery of plasminogen activators to reverse thrombus in multiple mouse thrombosis models. Adv Mater. 2020;32:e1905145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan M, Wang Q, Wang R, Wu R, Li T, Fang D, Huang Y, Yu Y, Fang L, Wang X, Zhang Y, Miao Z, Zhao B, Wang F, Mao C, Jiang Q, Xu X, Shi D. Platelet-derived porous nanomotor for thrombus therapy. Sci Adv. 2020;6: eaaz9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He X, Jiang H, Li J, Ma Y, Fu B, Hu C. Dipole-moment induced phototaxis and fuel-free propulsion of zno/pt Janus micromotors. Small. 2021;17:e2101388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu XZ, Wen ZJ, Li YM, Sun WR, Hu XQ, Zhu JZ, Li XY, Wang PY, Pedraz JL, Lee J-H, Kim H-W, Ramalingam M, Xie S, Wang R. Bioengineered bacterial membrane vesicles with multifunctional nanoparticles as a versatile platform for cancer immunotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15:3744–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang R, Yu Y, Gai M, Mateos-Maroto A, Morsbach S, Xia X, He M, Fan J, Peng X, Landfester K, Jiang S, Sun W. Liposomal enzyme nanoreactors based on nanoconfinement for efficient antitumor therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;62:e202308761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson R, Ertural C, George J, Deringer VL, Hautier G, Dronskowski R. Local orbital projections, atomic charges, and chemical-bonding analysis from projector-augmented-wave-based density-functional theory. J Comput Chem. 2020;41:1931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang D, Zuo S, Yang H, Zhou Y, Lu Q, Wang X. Tailoring layer number of 2D porphyrin-based MOFs towards photocoupled electroreduction of CO2. Adv Mater. 2022;34:e2107293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong W, Li L, Chen X, Yao Y, Ru Y, Sun Y, Hua W, Zhuang G, Zhao D, Yan S, Song W. Mesoporous anatase crystal-silica nanocomposites with large intrawall mesopores presenting quite excellent photocatalytic performances. Appl Catal B. 2019;246:284–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang Z, Xu L, Shan Y, Cui X, Shi B, Xi Y, Ren P, Zheng X, Zhao C, Luo D, Li Z. Tumor microenviroment-responsive self-assembly of barium titanate nanoparticles with enhanced piezoelectric catalysis capabilities for efficient tumor therapy. Bioact Mater. 2024;33:251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao W, Wei W, Qiu B, Liu Y, Xie S, Fang Q, Li X. Ultrasound-powered hydrogen peroxide-responsive Janus micromotors for targeted thrombolysis and recurrence inhibition. Chem Eng J. 2024;483: 149187. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang A, Wang M, Liu H, Liu S, Song X, Zou Y, Deng Y, Qin Q, Song Y, Zheng Y. Gasdermin E plasmid DNA/indocyanine green coloaded hybrid nanoparticles with spatiotemporal controllability to induce pyroptosis for colon cancer treatment. MedComm – Oncology. 2023;2: e33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Wang Y, Chen Z, Cai J, Li K, Huang H, Song F, Gao M, Yang Y, Zheng L, Zhao J. NIR-driven polydopamine-based nanoenzymes as ROS scavengers to suppress osteoarthritis progression. Mater Today Nano. 2022;19:100240. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun M, Liu C, Liu J, Wen J, Hao T, Chen D, Shen Y. A microthrombus-driven fixed-point cleaved nanosystem for preventing post-thrombolysis recurrence via inhibiting ferroptosis. J Control Release. 2024;367:587–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong Y, Ye M, Huang L, Hu L, Li F, Ni Q, Zhong J, Wu H, Xu F, Xu J, He X, Wang Z, Ran H, Wu Y, Guo D, Liang X-J. A fibrin site-specific nanoprobe for imaging fibrin-rich thrombi and preventing thrombus formation in venous vessels. Adv Mater. 2022;34:e2109955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jennings LK. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam J, Klein G, Lehnert T. Hydroxyl content of BaTiO3 nanoparticles with varied size. J Am Ceram Soc. 2013;96:2987–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Wang F, Liu C, Wang Z, Kang L, Huang Y, Dong K, Ren J, Qu X. Nanozyme decorated metal-organic frameworks for enhanced photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:651–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Q, Liu D, Wang R, Feng Z, Zuo Z, Qin S, Liu H, Xu X. The dielectric and photochromic properties of defect-rich BaTiO3 microcrystallites synthesized from Ti2O3. Materials Science and Engineering: B. 2012;177:639–44. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xing J, Li YH, Jiang HB, Wang Y, Yang HG. The size and valence state effect of Pt on photocatalytic H2 evolution over platinized TiO2 photocatalyst. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2014;39:1237–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niu F, Chen D, Qin L, Gao T, Zhang N, Wang S, Chen Z, Wang J, Sun X, Huang Y. Synthesis of Pt/BiFeO3 heterostructured photocatalysts for highly efficient visible-light photocatalytic performances. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2015;143:386–96. [Google Scholar]