Abstract

Adult stem cells maintain and rejuvenate a wide range of tissues, and the progressive, age-related decline of adult stem cells is a hallmark of aging. We propose that the Caenorhabditis elegans germline is an experimentally tractable model of adult stem cell aging and that stem cell exhaustion is a cause of reproductive senescence. Because these are the only stem cells in adult worms, this system provides a unique opportunity to exploit the power of C. elegans to address stem cell exhaustion during aging. Here, we show that reproductive aging occurs early in adult life in multiple species in the genus Caenorhabditis, indicating that this is a feature of both female/male and hermaphrodite/male species. Our results indicate that cellular and molecular changes in germline stem cells are a cause of reproductive aging, since we demonstrated that defects in stem cell number and activity were well correlated with extended progeny production in daf-2, eat-2, and phm-2 C. elegans mutants. Ectopic expression of the Notch effector SYGL-1 in germ line stem cells was sufficient to delay stem cell aging, indicating that the conserved Notch pathway can act cell autonomously to control age-related decline of adult stem cells. These animals displayed increased progeny production in midlife without a depression of early progeny production, a pattern of reproductive aging distinct from previous mutants. These results suggest that age-related declines of stem cell number and activity are a cause of reproductive aging in C. elegans and the Notch signaling pathway may be a control point that mediates this decline.

Keywords: germline, reproductive aging, stem cells, nutrient sensing, Notch

Significance Statement.

The progressive, age-related decline in adult stem cells is a hallmark of aging. However, the mechanisms of adult stem cell decline during aging are poorly defined. Here, we demonstrated that the Caenorhabditis elegans germline is an experimentally tractable model of adult stem cell aging in vivo. We characterized the cellular and molecular changes that occur in the germline during reproductive aging and found that (i) cellular and molecular changes in germline stem cells are a cause of reproductive aging and (ii) the conserved Notch pathway can act cell autonomously to control age-related decline of adult stem cell number and activity. Our results provide new insights into the regulation of stem cell exhaustion during aging.

Introduction

As adult animals advance through time, they display progressive degenerative changes in multiple organ systems. Most aging research focuses on the decline of life support systems that result in death and determine adult lifespan. However, there is growing appreciation that the age-related decline of the reproductive system, which results in infertility, is an important dimension of aging (1). Because female reproduction typically declines well before the maximum adult lifespan, reproductive aging offers the possibility to experimentally investigate an aging organ in the context of a relatively intact animal. In addition, reproductive aging is conceptually important because progeny production is the ultimate goal of animal life. Thus, reproductive aging is a central issue in evolutionary theories of aging. Furthermore, reproductive aging is clinically relevant in humans. Age-related infertility is increasingly a concern for women who wait until middle age to start families, and infertility treatments are a major source of medical expenses (2).

The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans is an experimentally powerful model for reproductive aging that is relevant to mammals (1, 3). C. elegans hermaphrodites produce a limited amount of self-sperm, which in turn limits the self-fertile brood size; mating to males provides abundant sperm, increases late-life progeny production, and facilitates studies of reproductive aging. From a fertilized egg, the C. elegans hermaphrodite develops its entire soma and both arms of its reproductive tract and then begins laying eggs at ∼65 h at 20 °C (4). At the peak of reproduction, oocytes are ovulated every ∼23 min (5), resulting in an average of ∼150 progeny per day. Even when sperm are not limiting, reproduction ceases relatively early in adult life; in wild-type (WT) hermaphrodites with excess sperm from mating to males, the reproductive span is ∼9 days and the adult lifespan is ∼16 days scored from the end of the L4 larval stage (6). Further, progeny production declines from a peak of ∼150 progeny per day on adult day 2 to ∼40 progeny per day on adult day 5 and to ∼12 progeny per day on adult day 7, while the animals are all still alive, moving, and feeding (7). Because C. elegans has a self-fertile hermaphrodite/male sexual system (protandrous, androdioecious), it is an open question whether it has evolved an unusual type of reproductive aging compared with the more prevalent female/male (gonochoristic) species. Here, we show that reproductive aging occurs relatively early in two female/male species in the genus Caenorhabditis, suggesting that this is a general feature and not specific to self-fertile hermaphrodites.

Because C. elegans is a premier system for genetic analysis, many mutations have been identified that delay age-related degenerative changes of somatic tissues and extend mean lifespan. Interestingly, only a small subset of these mutations have been reported to delay reproductive aging (8–17). A mutation of daf-2 that impairs the activity of the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway reduces the level of early progeny production, extends the reproductive span, and increases the level of progeny production late in life. Similar patterns are caused by eat-2 and phm-2 mutations that result in pathogenic infections and food avoidance behavior that drives dietary restriction (18). These observations raise the question of whether reduced levels of early progeny production are the cause of delayed reproductive aging or an independent, correlated effect. Because the identification of mutations that delay reproductive aging is an important first step in elucidating the mechanisms of this process, the discovery of additional mutations that cause this phenotype is an important objective.

A detailed description of the molecular and cellular changes that occur during reproductive aging is important for generating hypotheses about the sequence of events that cause these changes (1). This description is an essential foundation to comprehensively understand how genetic mutations influence this phenotype. Kocsisova et al. (7) reasoned that because the most striking decline in reproduction (in hermaphrodites with sufficient sperm) occurs at approximately day 5 of adulthood, when mated hermaphrodites produce only ∼40 progeny—a mere quarter of peak reproduction—it would be relevant to analyze age-related changes in the germline that occur a day or two before this time. The decline in progeny production is preceded by decreased Notch signaling in the distal germ line, a decreased stem cell pool, a slower stem cell cycle, and decreased meiotic entry from the progenitor zone (PZ). Based on these observational studies, Kocsisova et al. (7) hypothesized that these age-related molecular and cellular changes cause reproductive aging. However, this hypothesis has not been rigorously evaluated.

Adult stem cells maintain and rejuvenate a wide range of tissues, and the progressive, age-related decline in adult stem cells is a hallmark mammalian of aging (19). Adult stem cell exhaustion is widespread and important—it occurs in many different tissues across a wide range of taxa (20). However, the mechanisms of adult stem cell decline during aging are poorly defined. Stem cells proliferate and differentiate in an environment called the niche; in principle, stem cell aging might be caused by intrinsic factors in stem cells themselves (autonomous) or age-related changes in the extrinsic niche (nonautonomous) (21, 22). If the niche is responsible for age-related degeneration, then modulating these extrinsic factors to sustain stem cell activity could be an innovative and effective approach to maintain adult stem cells and extend health span. In C. elegans hermaphrodites, germline stem cells and progenitors reside in the distal-most region of the gonad called the PZ. Stem cells are maintained in mitosis by a niche that consists of one somatic cell—the distal tip cell (DTC). The DTC expresses Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 ligands that activate the GLP-1/Notch receptor on the germline stem cells (23–27). Activated GLP-1 promotes the expression of direct transcriptional target genes—lst-1 and sygl-1—which are redundantly necessary and sufficient to maintain germline stem cells throughout development and adulthood (28, 29). The germline represents an assembly line of gamete production; as germ cells progress proximally away from the DTC, they transition through stages of meiotic differentiation.

To test the hypothesis that age-related changes in the distal germline are a cause of reproductive aging, we analyzed daf-2, eat-2, and phm-2 mutants. Delayed changes in the distal germline were well correlated with extended progeny production, supporting the hypothesis that declines in stem cell number and activity are a cause of reproductive aging. We directly manipulated the Notch signaling pathway by increasing the expression levels of sygl-1, a direct Notch target gene that specifies the stem cell fate. Ectopic expression of sygl-1 was sufficient to increase midlife reproduction without reducing the level of early reproduction or extending lifespan. This pattern of delayed reproductive aging is distinct from that caused by previously identified mutations, and this mutant illustrates that reduced early reproduction is not essential for delayed reproductive aging. These findings directly link cell autonomous activity of Notch signaling pathway in germline stem cells to reproductive aging. The results establish the C. elegans germline as an experimentally tractable model of adult stem cell aging in vivo. Because stem cells in the germline are the only stem cells in adult worms, this system provides a unique opportunity to exploit the power of C. elegans to address stem cell exhaustion during aging.

Results

Rapid reproductive aging occurs in hermaphrodite/male and female/male species in the genus Caenorhabditis

Hughes et al. (11) showed that reproductive aging occurs rapidly compared with somatic aging in the species C. elegans that is hermaphrodite/male. To determine whether rapid reproductive aging is specific to hermaphrodite/male nematode species, we analyzed Caenorhabditis species that are female/male. Caenorhabditis is well suited for comparative studies, since the genus contains ∼60 described species (30, 31). At least three of these are hermaphrodite/male (C. elegans, Caenorhabditis briggsae, and Caenorhabditis tropicalis), while the remaining species exhibit the ancestral female/male reproductive strategy (e.g. Caenorhabditis brenneri, Caenorhabditis remanei, and Caenorhabditis angaria) (32). We measured lifespan and progeny production of females of WT C. brenneri and C. remanei, as well as WT and fog-2(lf) mutant C. elegans, where the germline is feminized in hermaphrodites but males are unaffected. Females were mated to conspecific males. All three species displayed a peak of reproduction at days 2–3 of adulthood, followed by a decline in reproduction (Fig. 1). Very few progeny were produced after day 8 (Table S1). By contrast, survival of animals was above 75% until day 10 (Fig. 1). Thus, mated females from both female/male and hermaphrodite/male species in the genus Caenorhabditis displayed age-related reproductive decline several days before animals began to display age-related death.

Fig. 1.

C. elegans, C. brenneri, and C. remanei displayed rapid reproductive aging. The left axis indicates daily progeny production of unmated, self-fertile hermaphrodites (yellow), mated hermaphrodites (red), or mated females (red). Circles are values from one individual, and lines indicate the average. The right axis indicates survival of mated hermaphrodites or mated females (black). Vertical marks on survival plots indicate timepoints when animal(s) were censored due to matricidal hatching or crawling off the dish. In some experiments, the survival curve did not reach zero due to censoring. Dashed line indicates 50% survival. The horizontal axis indicates adult age in days. A) WT C. elegans strain N2 (self-fertile n = 12 mothers/2,091 progeny: mated n = 11 mothers/6035 progeny). B) C. elegans fog-2(oz40) strain BS553 (mated n = 20 mothers/11,268 progeny). C) C. brenneri strain VX02253 (mated n = 10 mothers/1,827 progeny). D) C. remanei strain SB146 (mated n = 20 mothers/7,770 progeny). A) Reproduced with permission from Kocsisova et al. (7) and Pickett et al. (6). See Table S1.

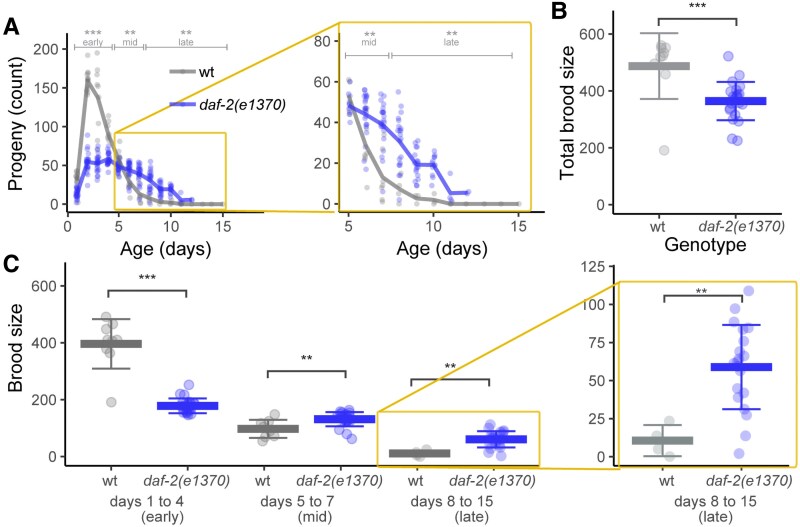

Partial loss of insulin/IGF-1 signaling caused by daf-2(e1370) delayed reproductive aging and age-related changes in germ cells

To investigate the mechanism of rapid reproductive aging, we analyzed mutant strains that display delayed reproductive aging in hermaphrodites with sufficient sperm. daf-2(e1370) is a partial loss-of-function mutation in the insulin/IGF-1 receptor that delays somatic and reproductive aging (11, 33). We counted daily progeny production and analyzed three phases: early (days 1–4), midlife (days 5–7), and late (days 8–15). Early progeny production by mated daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites (180 ± 30) was much lower than WT hermaphrodites (400 ± 90), whereas midlife progeny production was slightly higher than WT (130 ± 25 vs. 100 ± 30), and late progeny production was much higher than WT (60 ± 30 vs. 10 ± 10) (Figs. 2A–C and S1A, Table S2). The total brood size of daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites (360 ± 70) was significantly lower than WT hermaphrodites (490 ± 120) (Fig. 2B, Table S2). Thus, daf-2 is necessary to promote high levels of early progeny production and rapid reproductive aging.

Fig. 2.

The daf-2(e1370) mutation delayed reproductive aging. WT (gray) and daf-2(e1370) (blue) hermaphrodites were mated to males. A) Lines are average daily progeny production, and points are data for individuals. Brackets above indicate early (days 1–4), midlife (days 5–7), and late (days 8–15) progeny production periods. Within each time period, WT and mutant progeny totals were compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The area in the yellow box is enlarged on the right. B) The total brood size, sum of progeny on days 1–15, compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Bar and whiskers indicate mean ± SD. C) The early, midlife, and late brood size. Kruskal–Wallis test. The area in the yellow box is enlarged on the right. WT mothers n = 9 early, 8 mid, and 4 late; daf-2 mothers n = 22 early, 22 mid, and 20 late. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. See Table S2.

To determine whether delayed reproductive aging is a general feature of lifespan extending mutations in the insulin/IGF-1 pathway, we analyzed additional alleles. Late progeny production was not significantly different in mated hermaphrodites of daf-2(e1368) (28 ± 13), age-1(hx546) (11 ± 7), or age-1(am88) (23 ± 18) compared with WT (22 ± 15) (Fig. S1B and C, Table S2). The total mated brood size of daf-2(e1368) (420 ± 70) was significantly smaller than WT (485 ± 120) (Fig. S1D–F, Table S2). daf-2 mutations have been sorted into two classes based on phenotype: e1368 is a Class I allele, whereas e1370 is a Class II alleles (see Discussion for details). Hughes (34) reported that mated hermaphrodites of daf-2(m41) and age-1(hx546) did not display increased progeny production after day 9 (1.3 ± 0.7 and 0.5 ± 0.2, respectively) compared with WT (1.8 ± 0.5). Thus, even among insulin/IGF-1 pathway mutations that extend longevity, the daf-2(e1370) allele is unusual in causing a delay of reproductive aging.

To determine the molecular and cellular changes in daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites that may be responsible for delayed reproductive aging, we used the techniques described in Kocsisova et al. (7) to measure germline phenotypes in day 1, 3, 5, and 7 mated hermaphrodites. To measure the distal–proximal extent of Notch signaling, we used an anti-FLAG antibody to stain sygl-1(am307flag) hermaphrodites, which express from the native locus SYGL-1 fused to 3xFLAG epitope. sygl-1 is a direct target of Notch (28, 29, 35) and thus a readout of the extent of Notch signaling output in the distal germline. We counted the number of cell diameters (cd, a measure of length) from the distal tip of the gonad to the last row with half or more FLAG immunoreactive cells. sygl-1(am307flag) hermaphrodites displayed an age-related decrease in the extent of SYGL-1 staining from 10 ± 2 cd at day 1, to 7.5 ± 2 cd at day 3, to 7 ± 2 cd at day 5 (7). daf-2(e1370); sygl-1(am307flag) hermaphrodites displayed a significantly longer SYGL-1 zone at day 1 (12 ± 1.5 cd) and day 3 (9 ± 1 cd) compared with control. Day 5 displayed a higher value (8.4 ± 3 cd) that did not reach statistical significance with this sample size (P = 0.15) (Fig. 3A–D, Table S3). To evaluate the Notch target gene LST-1, we used an anti-FLAG antibody to stain lst-1(am302flag) hermaphrodites, which express from the native locus LST-1 fused to 3xFLAG epitope (Fig. S1J). daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites were not significantly different from WT (Fig. S1I).

Fig. 3.

The daf-2(e1370) mutation delayed age-related deterioration of germ cells. A) One of two gonad arms of the young adult hermaphrodite. Cells progress from mitotic cycling to meiotic prophase to meiotic maturation before being fertilized by sperm in the spermatheca (yellow). The PZ (red, defined by WAPL-1 staining) contains mitotically cycling stem cells and progenitor cells. The DTC (nucleus in red, as are other somatic gonad cells) provides LAG-2/delta ligand which interacts with GLP-1/Notch receptor on germs cells to maintain the germline stem cell fate via sygl-1 and lst-1. A) Modified with permission from Kocsisova et al. (7). B) Diagram of the sygl-1(am307) genomic locus. DNA encoding a 3xFLAG epitope (magenta) was inserted in-frame using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, resulting in an N-terminally tagged fusion protein expressed from the endogenous locus. C) Representative confocal micrograph of distal germlines at day 5. The genotypes were: top left control—sygl-1(am307flag); bottom left control—wt; top right—sygl-1(am307flag; daf-2(e1370); bottom right—daf-2(e1370). Top: animals with sygl-1(am307flag) were stained for FLAG (gray, row 1), WAPL-1 (red, row 2), FLAG and WAPL-1 overlay (row 3), and DAPI (blue, row 4). Bottom: a second set of animals were exposed to EdU for 10 h and stained for EdU (green, row 5), WAPL-1 (red, row 6), EdU and WAPL-1 overlay (row 7), and DAPI (blue, row 8). Asterisks indicate DTC nucleus position; white dashed line indicates proximal boundary of WAPL-1-positive cells; yellow arrowheads indicate proximal boundary of FLAG:SYGL-1; white arrowheads indicate proximal boundary of EdU. For the control animal, the most proximal EdU-positive nuclei stained faintly; they were visible to the experimenter but did not reproduce well in this nonoverexposed image. Note: all z-planes were checked to determine proximal boundaries. Scale bar 10 μm. D) The extent of SYGL-1 in cd measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more SYGL-1-positive cells. The genotypes were: control—sygl-1(am307flag), n = 41, 14, and 14 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; daf-2—sygl-1(am307flag); daf-2(e1370), n = 29, 22, and 16 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively. E) The length of the PZ in cd, measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more WAPL-1-positive nuclei. Control—n = 204, 98, and 64 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; daf-2—n = 142, 143, 81, and 25 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively. F) The extent of meiotic entry in cd, measured from the end of the PZ to the last EdU+ nucleus following a 10-h EdU label. Control—n = 65, 57, and 34 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; daf-2—n = 48, 42, 34, and 25 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively. D)–F) Bar and whiskers indicate mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. See Table S3.

To measure the length of the PZ, we used the WAPL-1 antibody and counted the number of cd from the distal tip to the last row with half or more WAPL-1 immunoreactive nuclei (36). WT hermaphrodites displayed an age-related decrease in the length of the PZ from 20 ± 2 cd at day 1, to 14 ± 3 cd at day 3, to 11 ± 4 cd at day 5 (Fig. 3C and E, Table S3 (7)). The PZ of daf-2(e1370) mated hermaphrodites at day 1 (17 ± 3 cd) was significantly shorter than WT. This result is similar to the results of Michaelson et al. (37) and Qin and Hubbard (14), who report that the PZ of self-fertile young adult daf-2(e1370) animals contains fewer nuclei than WT. The age-related decline of PZ length was blunted in daf-2(e1370) mated hermaphrodites; at day 5, daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites displayed a significantly longer PZ (14 ± 3 cd) than WT (Fig. 3E, Table S3). Germline deterioration by day 7 in WT hermaphrodites was so severe that it was not possible to reliably measure PZ length. By contrast, day 7 daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites could be analyzed and displayed a PZ that was longer than day 5 WT. Thus, the length of the PZ was well correlated with progeny production.

The rate at which cells exit the PZ and enter meiotic prophase is a sensitive measure of gamete production capacity. To measure meiotic entry, we fed hermaphrodites the nucleoside analog EdU for 10 h and then dissected, fixed, stained for cells that incorporated EdU, and imaged the germline. The number of rows of cells that exhibited EdU signal, but had entered meiotic prophase (WAPL-1 negative) was counted. These cells must have resided in the PZ at the beginning of the experiment to become EdU labeled. WT hermaphrodites displayed an age-related decline in the extent of meiotic entry from 18 ± 3 cd at day 1, to 6 ± 4 cd at day 3, to 3 ± 3 cd at day 5 (Fig. 3C and F, Table S3). Day 7 WT were so deteriorated that it was not possible to measure meiotic entry. The meiotic entry of daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites at day 1 (9 ± 2 cd) was significantly shorter than WT. The age-related decline of meiotic entry was blunted in daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites; at days 3 and 5, daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites displayed significantly higher meiotic entry (10 ± 3 and 7 ± 2 cd) compared with WT. At day 7, the germline of daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites subjectively appeared much healthier and younger than WT. Objectively, daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites displayed measurable meiotic entry at day 7 (7 ± 3 cd) that was significantly higher than day 5 WT (Fig. 3F). To better understand the relationship between PZ length and meiotic entry, we compared the extent of meiotic entry relative to the length of the PZ. We observed a similar pattern of decline, suggesting that the decline in meiotic entry is not fully explained by the shorter PZ (Fig. S1H, Table S3). In general, meiotic entry was well correlated with progeny production.

The somatic DTC provides the niche for the germline stem cells by expressing LAG-2 (delta ligand) (23, 25–27). Kocsisova et al. (7) monitored age-related changes in the positon of the DTC nucleus relative to the distal end of the germline in WT. Day 3 and 5 adults displayed a shift of 5 cd or more in a subset of animals. This is a low-frequency event that might explain reproductive decline in some animals but does not account for reproductive decline in most animals (7). To determine whether the daf-2(e1370) mutation influences this age-related change, we measured the distance in cd between the distal end of the germline and the DTC nucleus. Both WT and daf-2(e1370) mutants displayed a similar age-related increase in the average value (Fig. S1G). Thus, this phenotype does not correlate with extended reproduction in daf-2(e1370) mutants, indicating that extended reproduction in this mutant is unrelated to the position of the DTC.

Overall, the daf-2(e1370) mutation delayed reproductive aging measured by progeny production late in life, and it also delayed age-related decreases in the extent of the Notch effector SYGL-1, the length of the PZ, and meiotic entry from the PZ. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the age-related decrease in Notch signaling reduces stem cell number and function, leading to a decrease in meiotic entry and the age-related decrease in progeny production.

Immune activation and dietary restriction caused by eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) delayed reproductive aging and age-related changes in germ cells

Mutations in eat-2 and phm-2 disrupt the pharynx and allow live E. coli bacteria to enter the intestine, resulting in activation of an immune response, bacterial avoidance behavior, dietary restriction, and extended lifespan (18). In hermaphrodites with sufficient sperm, these mutations delay reproductive aging: the number of progeny produced in late life (after day 10) is significantly higher in mated eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) hermaphrodites than in mated WT hermaphrodites (11, 12, 18). Our strategy was to exploit these mutants to test the hypothesis that molecular changes in the distal germline correlate with extended reproductive function in older adults. To quantitatively evaluate these mutants, we first analyzed progeny production. Early progeny production by mated eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites (110 ± 40) was significantly lower than WT hermaphrodites (400 ± 90), whereas midlife progeny production was not significantly different than WT (70 ± 30 vs. 100 ± 30) and late progeny production was much higher than WT (65 ± 30 vs. 10 ± 10) (Fig. 4A and C, Table S2). The total brood size of eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites (245 ± 80) was significantly lower than WT hermaphrodites (490 ± 120) (Fig. 4D, Table S2). For mated phm-2(am117) hermaphrodites, early (70 ± 30) and midlife (40 ± 10) progeny production was significantly lower than WT hermaphrodites (400 ± 90 and 100 ± 30). Late progeny production was higher than WT (26 ± 30 vs. 10 ± 10), but the difference was not significant with this sample size (P = 0.21) (Fig. 4B and C, Table S2). The total brood size of phm-2(am117) hermaphrodites (130 ± 60) was significantly lower than WT hermaphrodites (490 ± 120) (Fig. 4D, Table S2). Thus, eat-2 and phm-2 are necessary to promote high levels of early progeny production and rapid reproductive aging.

Fig. 4.

The eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) mutations delayed reproductive aging and age-related deterioration of germ cells. WT (gray), eat-2(ad465) (light green), and phm-2(am117) (dark green) hermaphrodites were mated to males. A), B) Lines are average daily progeny production, and points are data for individuals. Brackets above indicate early (days 1–4), midlife (days 5–7), and late (days 8–15) progeny production periods compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The area in the yellow box is enlarged on the right. C) The early, midlife, and late brood size. The area in the yellow box is enlarged on the right. D) The total brood size, sum of progeny on days 1–15, compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. WT mothers n = 9 early, 8 mid, and 4 late; eat-2 mothers n = 15 early, 15 mid, and 15 late; phm-2 mothers n = 17 early, 15 mid, and 15 late. E), H) The extent of SYGL-1 in cd measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more SYGL-1 positive cells. The genotypes were: control—sygl-1(am307flag) n = 41, 14, and 14 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; eat-2—sygl-1(am307flag); eat-2(ad465); n = 13, 31, and 33 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; phm-2—sygl-1(am307flag); phm-2(am117); n = 32, 27, and 1 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively. F), I) The length of the PZ in cd, measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more WAPL-1-positive cells. WT—n = 204, 98, and 64 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; eat-2—n = 67, 118, 118, and 25 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively; phm-2—n = 61, 92, 31, and 7 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively. G), J) The extent of meiotic entry in cd, measured from the end of the PZ to the last EdU + cell following a 10-h EdU label. WT—n = 65, 57, and 34 for days 1, 3, and 5, respectively; eat-2—n = 27, 29, 31, and 25 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively; phm-2—n = 23, 27, 30, and 7 for days 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively. C), E)–J) Bar and whiskers indicate mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. See Tables S2 and S3.

To determine the molecular and cellular changes in eat-2 and phm-2 hermaphrodites that may be responsible for delayed reproductive aging, we measured germline phenotypes in day 1, 3, 5, and 7 mated hermaphrodites. For eat-2(ad465); sygl-1(am307flag) and phm-2(am117); sygl-1(am307flag) mated hermaphrodites, the extent of SYGL-1 at all ages was similar or slightly less compared with control (Fig. 4E and H, Table S3). A similar result was observed with LST-1 (Fig. S2C and F). The PZ of eat-2(ad465) mated hermaphrodites at day 1 (14 ± 3 cd) was significantly shorter than that of WT mated hermaphrodites (20 ± 2 cd), consistent with reports that in self-fertile young adult eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites the PZ is significantly shorter and contains fewer nuclei than WT (38, 39). The age-related decline of PZ length was blunted in eat-2(ad465) mated hermaphrodites; at day 5, eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites displayed a PZ (11 ± 3 cd) that was similar to WT (Fig. 4F and I, Table S3). Day 7 eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites could be analyzed and displayed a PZ that was longer than day 5 WT. phm-2(am117) mated hermaphrodites displayed a similar pattern—the PZ was shorter than WT on days 1 and 3, but the age-related decline was blunted and the PZ was significantly longer than WT by day 5 (14 ± 3 cd vs. 11 ± 4 cd) (Fig. 4F and I, Table S3). Thus, the length of the PZ was well correlated with progeny production.

The meiotic entry of mated eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites at day 1 (5 ± 2 cd) was significantly lower than WT (18 ± 3 cd), consistent with a lower level of early progeny production. The age-related decline of meiotic entry was blunted in eat-2(ad465) hermaphrodites; at days 3 and 5, the values were similar to WT, and at day 7, the germline appeared healthier than WT and displayed measurable meiotic entry (Fig. 4G, Table S3). A similar pattern was observed comparing the extent of meiotic entry relative to the length of the PZ rather than cd (Fig. S2B, Table S3). phm-2(am117) mated hermaphrodites displayed a similar pattern. Meiotic entry was significantly lower than WT in day 1 and 3 hermaphrodites, but the age-related decline was blunted so that the mutants were similar to WT on day 5 and appeared healthier than WT and displayed measurable meiotic entry on day 7 (Figs. 4J and S2E, Table S3). Thus, meiotic entry was well correlated with progeny production.

To investigate the position of the DTC nucleus, we measured the position in cd relative to the distal end of the germline. Mated eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) hermaphrodites displayed an age-related increase in the DTC nucleus shift that was not significantly different from WT (Fig. S2A and D). Thus, the extended reproduction displayed by these mutants is unrelated to the DTC nucleus position.

Taken together, these results indicate that the pattern of PZ length and meiotic entry matched the pattern of progeny production in eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) mated hermaphrodites relative to WT. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the age-related decrease in adult stem cells leads to a decrease in meiotic entry and thus is a cause of the age-related decrease in progeny production.

Ectopic expression of the Notch pathway effector SYGL-1 was sufficient to delay midlife reproductive aging and age-related changes in germ cells

The DTC expresses the Notch ligand LAG-2, which binds GLP-1 Notch expressed by the germline stem cells, thereby maintaining these cells in the proliferative, stem cell fate (40, 41). Kocsisova et al. (7) reported an age-related decline in the length and size of the Notch signaling domain, as measured by the expression of the direct Notch target genes lst-1 and sygl-1. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that an age-related decrease in Notch pathway signaling causes the decrease in stem cells, which leads to age-related decreases in PZ output and progeny production. This hypothesis predicts that sustaining the activity of the Notch pathway in aging animals could delay reproductive aging.

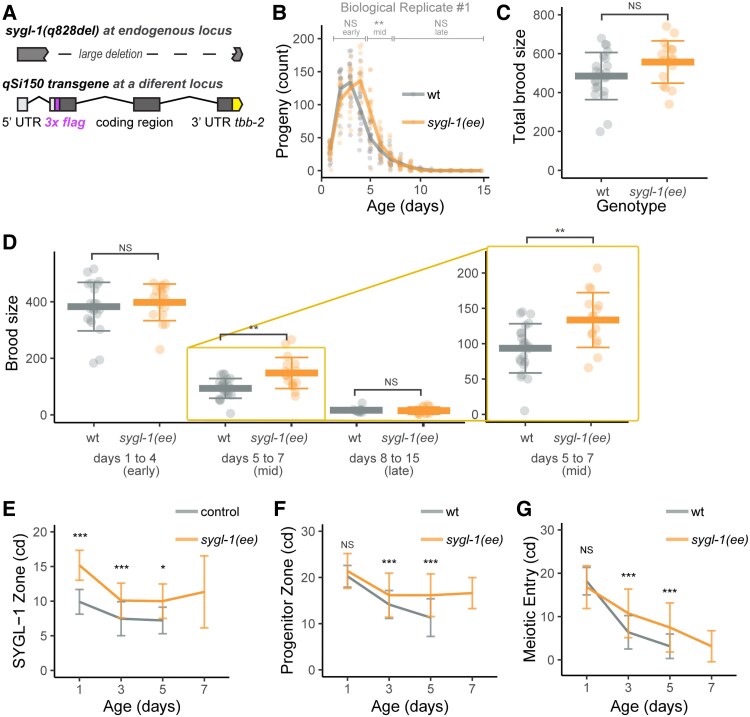

Shin et al. (29) showed that the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the sygl-1 mRNA is a site of negative regulation. Transgenic animals in which the sygl-1 3′UTR is replaced by the unregulated tbb-2 3′UTR result in ectopic expression of SYGL-1 in the distal germline, expanding the zone of accumulation proximally (29). We refer to this ectopic expression strain as sygl-1(ee) (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Ectopic expression of SYGL-1 delayed midlife reproductive aging and age-related deterioration of germ cells. WT (gray) and sygl-1(ee) (orange) hermaphrodites were mated to males. A) Genotype of the sygl-1(ee) strain (JK5500) is sygl-1(q828null), mut-16(unknown) I; unc-119(ed3lf); qSi150[psygl-1::3xflag::sygl-1::tbb-2 3′utr; Cbr-unc-119(+)] II. Diagrams show the endogenous sygl-1 locus containing the q828 deletion mutation (top) and the integrated transgene containing the sygl-1 promoter, an in-frame 3X FLAG epitope (magenta), and the 3′ UTR from tbb-2 (yellow) (bottom) (29). The sygl-1(ee) strain contains the q828 deletion at the endogenous locus and the qSi150 transgene integrated at another location in the genome. B) Lines are average daily progeny production, and points are data for individuals. Brackets above indicate early (days 1–4), midlife (days 5–7), and late (days 8–15) progeny production periods compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. C) The total brood size, sum of progeny on days 1–15, compared by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. D) The early, midlife, and late brood size. The area in the yellow box is enlarged on the right. E) The extent of SYGL-1 in cd measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more SYGL-1-positive cells. The genotypes were: control—sygl-1(am307flag); and treatment sygl-1(q828null), mut-16(unknown) I; unc-119(ed3lf); qSi150[psygl-1::3xflag::sygl-1::tbb-2 3′utr; Cbr-unc-119(+)], abbreviated as sygl-1(ee). F) The length of the PZ in cd, measured from the distal tip to the last row with half or more WAPL-1 positive cells. G) The extent of meiotic entry in cd, measured from the end of the PZ to the last EdU + cell following a 10-h EdU label. C)–G) Bar and whiskers indicate mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001.

To determine whether the expanded accumulation of SYGL-1 is sustained, we used anti-FLAG antibodies to measure the domain of SYGL-1. Mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed significantly larger SYGL-1 extents at days 1, 3, and 5 compared with WT (15 ± 3 vs. 10 ± 2, 10 ± 2.5 vs. 7.5 ± 2, and 10 ± 2.5 vs. 7 ± 2 cd, respectively) (Fig. 5E, Table S3). Day 7 sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed measurable SYGL-1 expression (11 ± 5 cd), when WT is too degenerated to analyze. Thus, mutating the 3′UTR of the sygl-1 transgene resulted in expanded accumulation of SYGL-1 protein that was sustained into midlife.

To determine whether expanded accumulation of SYGL-1 is sufficient to delay reproductive aging, we measured daily progeny production of mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites in two replicates. Early progeny production was slightly but not significantly higher than WT in both replicates (400 ± 65 vs. 380 ± 90 and 530 ± 40 vs. 510 ± 30). Midlife progeny production was significantly higher than WT in both replicates (150 ± 55 vs. 90 ± 35 and 180 ± 60 vs. 100 ± 40). Late progeny production was not significantly different than WT (15 ± 13 vs. 16 ± 9 and 23 ± 22 vs. 9 ± 7) (Figs. 5B–D and S3B–E, Table S2). The total brood size of sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites was higher than WT hermaphrodites (560 ± 110 vs. 485 ± 120 and 730 ± 90 vs. 610 ± 60), and this difference was significant in the second replicate (Table S2).

Thus, sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed a different pattern of delayed reproductive aging compared to daf-2(e1370), eat-2(ad465), and phm-2(am117). Mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites produced WT levels of progeny on days 1–4 and significantly exceeded WT levels on days 5–7. Notably, sygl-1(ee) mutants outperformed WT animals in middle age without a decrease in peak progeny production in young animals.

To determine the cellular changes in sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites that may be responsible for delayed reproductive aging, we measured germline phenotypes in day 1, 3, 5, and 7 mated hermaphrodites. The PZ of sygl-1(ee) mated hermaphrodites at day 1 (21 ± 4 cd) was slightly but not significantly longer than WT mated hermaphrodites (20 ± 2 cd). The age-related decline of PZ length was blunted in sygl-1(ee) mated hermaphrodites; at days 3 and 5, sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed a PZ that was significantly larger than WT (16.5 ± 5 vs. 14 ± 3 and 16 ± 5 vs. 11 ± 4 cd, respectively) (Fig. 5F, Table S3). Day 7 sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites could be analyzed and displayed a PZ that was larger than day 5 WT. Thus, the length of the PZ was well correlated with progeny production.

The meiotic entry of mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites at day 1 (17 ± 5 cd) was similar to WT (18 ± 3 cd), consistent with a similar level of early progeny production. The age-related decline of meiotic entry was blunted in sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites; at days 3 and 5, the values were significantly higher than WT (11 ± 6 vs. 6 ± 4 and 7.5 ± 6 vs. 3 ± 3 cd, respectively) (Fig. 5G, Table S3). A similar pattern was observed comparing the extent of meiotic entry relative to the length of the PZ rather than cd—sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed significantly higher meiotic entry compared with WT at days 3 and 5 (Fig. S3G, Table S3). Thus, meiotic entry was well correlated with progeny production.

To investigate the position of the DTC nucleus, we measured the position in cd relative to the distal end of the germline. Mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites displayed an age-related increase in the DTC nucleus shift that was not significantly different from WT at days 5 and 7 (Fig. S3F). Thus, the extended reproduction displayed by these mutants is unrelated to the DTC nucleus position.

The sygl-1(ee) transgene that increased the number of progeny produced in midlife also increased the length of the PZ and meiotic entry from the PZ. These results support the hypothesis that the age-related decrease in adult stem cell function leads to a decrease in meiotic entry and causes the age-related decrease in progeny production.

To determine whether ectopic expression of SYGL-1 in the germline affected somatic aging, we measured the lifespan of unmated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites. These animals displayed a mean lifespan that was not significantly different from WT (12.5 days; sygl-1(ee) 11.9 days; log-rank test P = 0.7343) (Fig. S3A). Thus, ectopic expression of SYGL-1 can uncouple reproductive and somatic aging.

Discussion

Postreproductive lifespan is a feature of both hermaphrodite/male and female/male Caenorhabditids

Of 63 characterized species in the genus Caenorhabditis, 60 are female/male, whereas only three are hermaphrodite/male. However, these three—C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. tropicalis—have been analyzed extensively because they are convenient for laboratory genetic studies (32). Protandry likely evolved independently three times in the genus Caenorhabditis, and the evolution of a radically different mode of reproduction might have affected reproductive aging. Some genes regulating the development of protandry, such as fog-2 in C. elegans, are new and unique to the species (42, 43). Also, the near-lack of males, small size of self-sperm, radically different ascaroside signaling, and frequency of sperm depletion might have created new evolutionary pressures on the aging reproductive tract (9). To evaluate the generality of conclusions based on C. elegans self-fertile hermaphrodites, we analyzed two female/male species: C. brenneri and C. remanei.

Fertility studies of these female/male species are challenging due to inbreeding depression. Strains suitable for laboratory study can be generated through careful mating protocols to achieve a relatively inbred strain that harbors relatively few deleterious, sterile, and lethal alleles. We analyzed such a strain of C. brenneri (VX02253, a kind gift from Charles Baer). In the case of C. remanei, we obtained the strain from the CGC. In both species, a decline in reproductive function occurred several days before mated females began to die of old age. This is the same pattern previously reported (and confirmed here) in both WT protandrous and feminized C. elegans (11, 44). Thus, a postreproductive lifespan is not likely to be a consequence of an evolutionary history of self-fertile hermaphrodites. This result is consistent with findings in another female/male species, Caenorhabditis inopinata, the sister species to C. elegans (referred to as Caenorhabditis sp. 34 prior to 2017) (45, 46). C. inopinata produce the majority of progeny at days 2–3 of adulthood, few progeny at days 5–7, and are nearly sterile thereafter, while survival remains over 75% until ∼day 15 of adulthood (47).

Examining reproductive aging in more prevalent female/male species is important for understanding the evolution of reproductive aging. Aging varies across the tree of life (48), yet in almost all species that age, reproduction fails earlier in life than somatic functions (49). It has been hypothesized that the evolution of sperm limitation as a consequence of protandrous hermaphroditism could have led to the emergence of a postreproductive lifespan and an adaptive death (50). The results presented here and in Woodruff et al. (47) suggest the explanation for the postreproductive lifespan needs to account for both female/male and hermaphrodite/male species.

The C. elegans germline is a model of adult stem cell aging

Dozens of mutations have been reported to delay somatic aging and extend lifespan, but only a handful have been reported to delay reproductive aging (1). Hughes et al. (11) analyzed daily progeny production of long-lived mutants; whereas some displayed increased late-life progeny production, such as daf-2(e1370) and eat-2(ad465), others did not, such as clk-1(qm30) and isp-1(qm150). A forward genetic screen for extended reproduction by mated hermaphrodites identified that phm-2(am117) increased the number of progeny produced on and after day 10 of adulthood and extended lifespan (12, 18). The mechanism of lifespan extension and increased late-life progeny production in both eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) includes an immune and behavioral response that leads to dietary restriction (18).

Kocsisova et al. (7) described molecular and cellular age-related changes in the WT germline and gonad, leading to the hypothesis that these declines cause reproductive aging. However, the observational studies of Kocsisova et al. (7) did not rigorously establish the causal role of the reported age-related declines. To address the functional significance of the age-related declines observed in WT animals, we measured the same phenotypes in three mutant strains previously reported to display extended reproductive spans and increased numbers of progeny produced in late life: daf-2(e1370), eat-2(ad465), and phm-2(am117) (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Midlife reproductive improvement results from gain-of-function in Notch signaling. A) The model summarizes daily progeny production in mated daf-2(e1370), eat-2(ad465), and phm-2(am117) hermaphrodites that display a decrease in peak progeny production and an increase in late-life reproduction. This pattern is gene and allele specific for the insulin/IGF-1 pathway, since it is displayed by daf-2(e1370) but not several other daf-2 or age-1 mutations (Hughes (34) and this study). The interpretation of eat-2(ad465) and phm-2(am117) phenotypes is complicated by the finding that these strains are infected by E. coli OP50, resulting in an immune response, bacterial avoidance behavior, and dietary restriction (18). B) The model summarizes daily progeny production in mated sygl-1(ee) hermaphrodites that display normal peak progeny production and increased midlife reproduction. C) The diagram shows signaling events that promote progeny production. LAG-2 and APX-1 ligand on the DTC, activation of GLP-1 Notch on germ cells, and transcription of target genes lst-1 and sygl-1 regulate the number of stem cells. The speed of the cell cycle is regulated by unknown factors not included in this diagram. Together, the number of stem cells and cell cycle speed determine PZ output and progeny production. D) The diagram shows an integrated time course linking development and aging. We propose time-limited high LAG-2 and APX-1 expression results in a time-limited pulse of progenitor cells that results in a time-limited pulse of egg laying. A postreproductive period precedes the pulse of senescent death.

In day 1 adults, the germline of these three mutant animals is smaller and meiotic entry is lower than in WT. Thus, these genes function early in life to promote the establishment of a germline with normal size and function (37). However, the analysis of day 3, 5, and 7 adults revealed that the rate of decline is more gradual in these mutants compared with WT. At days 5 and 7, the mutant animals appear more youthful than WT at days 5 and 7. This effect is most pronounced in daf-2(e1370). The mated daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites began adulthood with a shorter PZ and lower rate of meiotic entry than WT; these mutants also produced fewer progeny during the first 4 days of adulthood than WT. With age, the decline in mated daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites was less steep than in mated WT hermaphrodites. By day 3 of adulthood, the mated daf-2(e1370) hermaphrodites maintained a longer SYGL-1 zone, a longer PZ, and a higher rate of meiotic entry than WT; these mutants also produced more progeny in late life than WT. Similarly, the patterns of germline morphology and stem cell activity in the other mutant strains matched the patterns of progeny decline. These correlations support the hypothesis that an age-related decrease in progenitor cell function leads to a decrease in meiotic entry and is a cause of the age-related decrease in progeny production. Because correlations do not definitively establish cause, it remains possible that another cause exists that was not measured. Thus, the C. elegans germline is a model of adult stem cell aging with profound consequences for organ function, since infertility is rapid and progressive.

To elucidate the role of the insulin/IGF-1 pathway in reproductive aging, we analyzed several alleles of age-1 and daf-2. The numerous mutations in daf-2 have been described in an allelic series and sorted into two classes: class I alleles, including e1368 and m41, affect certain extracellular regions of the receptor, while class II alleles, including e1370, are especially pleiotropic and affect either the ligand binding pocket or the tyrosine kinase domain. Class I and class II alleles differ in movement, fecundity, and aging phenotypes (10, 51–54). Of the insulin signaling pathway mutants tested in this study and by Hughes (34) (daf-2(e1368), daf-2(m41), age-1(am88), and age-1(hx546)), only daf-2(e1370) extended reproduction and significantly increased progeny production on and after day 8. This result suggests that the e1370 allele creates levels of insulin signaling that are “just-right” to delay reproductive aging without excessively hindering development. However, daf-2(e1370) does significantly decrease early reproduction (11, 34, this study).

Increased Notch signaling in adult stem cells delays stem cell aging and increases midlife reproduction

Kocsisova et al. (7) hypothesized that the age-related decline in stem cell number and slowing of the stem cell cycle cause reproductive aging. This hypothesis predicts that increasing the number of stem cells and/or the rate of the stem cell cycle will delay reproductive decline. The pathway that regulates the rate of the stem cell cycle has not been defined, but the Notch signaling pathway is well established to affect stem cell number (29, 55, 56). A transgenic strain in which 3′UTR-mediated repression of the Notch effector sygl-1 is interrupted displays a larger stem cell pool in young adults (29). To test whether extending Notch signaling output would be sufficient to delay reproductive aging, we analyzed this sygl-1(ee) strain.

Here, we report that ectopic expression of sygl-1 in germline stem cells was sufficient to increase progeny production in midlife (days 5–7). This mutant was also unusual because it exhibited WT levels of progeny production on days 1–4. Previously reported mutants that extend the reproductive span displayed decreased early peak progeny production and a decreased total brood size in mated hermaphrodites (11, 12, 17, 18). Whereas tradeoff theories propose that reduced early progeny production is the cause of extended reproduction, the analysis of sygl-1(ee) demonstrates that it is possible for a mutation to extend reproductive span without reducing early progeny production or total brood size (Fig. 6B). Unlike other mutant strains reported to delay reproductive aging, this strain was not long-lived. Thus, altering the expression of sygl-1 in the germline can delay reproductive aging without affecting somatic aging. These findings directly support the model that age-related declines in stem cell number contribute to reproductive aging (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, these results show that cell autonomous function of a key signaling pathway can delay the age-related stem cell exhaustion. Based on these findings, we speculate that age-related decreases in the Notch ligand, receptor signaling, or posttranscriptional control of SYGL-1 are an underlying cause of reproductive aging (Fig. 6D). Future experiments to investigate this model could include analyzing reproductive aging in transgenic animals that overexpress the Notch ligand LAG-2 or mutants with a gain-of-function in the glp-1 Notch receptor gene. Furthermore, future experiments could examine the direct Notch target gene lst-1 to determine whether stabilizing the mRNA will delay reproductive aging similar to sygl-1. Having established that ectopic expression of sygl-1 is sufficient to delay reproductive aging, future experiments can examine the interaction of sygl-1(ee) with mutations in daf-2, eat-2, and phm-2 that cause a different pattern of delayed reproductive aging.

Summary and conclusion

We identified a genetic manipulation that increased midlife reproduction without decreasing early progeny production: sygl-1(ee). sygl-1(ee) delays reproductive aging without extending lifespan, which breaks the correlation between reproductive and somatic aging. This pattern is complementary to many mutations that can extend lifespan but do not delay reproductive aging. These results show that while reproductive and somatic aging are connected, they are also separable.

An important difference between nematode and mammalian female germline development is that while mammalian female germline stem cells appear to cease dividing by mitosis before birth, nematode germline stem cell divisions continue into adulthood. Although the results presented here apply to Caenorhabditis nematodes and not humans, an analogy to human female reproductive aging may be illustrative: rather than identifying ways to help women have babies in their early 60 s (reproductive span extension), we identified a manipulation that is analogous to helping women have babies in their late 30 s (midlife reproductive increase), without compromising fertility in their 20 s. In C. elegans, it is possible to increase midlife reproduction without compromising early/peak reproduction.

Experimental procedure summary

All C. elegans strains are listed in Table S4. To measure progeny production of mated hermaphrodites, we placed one L4 hermaphrodite and three young adult, CB4855 males on an individual Petri dish with abundant food. After 24 h, we removed the males and placed each mated hermaphrodite on a fresh dish. We transferred the parent animal to a fresh dish daily. After 2 days, we scored the presence/absence of male progeny and the number of progeny produced.

Studies of lifespan were begun on day 0 by placing ∼60 L4 stage hermaphrodites on a Petri dish. Hermaphrodites were transferred to a fresh Petri dish daily during the reproductive period (approximately the first 10 days) to eliminate self-progeny and every 2–3 days thereafter. Each hermaphrodite was examined daily using a dissecting microscope for survival, determined by spontaneous movement or movement in response to prodding with a platinum wire. Mean lifespan and the log-rank test were calculated using OASIS 2 (57).

EdU labeling experiments were performed as described by Kocsisova et al. (58). The dissection and staining protocol follows the batch method (59), where all dissected tissues were incubated within small glass tubes rather than on a slide. Images were collected using a Zeiss Plan Apo 63X 1.4 oil-immersion objective lens on a PerkinElmer Ultraview Vox spinning disc confocal system on a Zeiss Observer Z1 microscope using Volocity software. Approximately 20 1-μm z-slice images were acquired for each gonad. Images were exported as hyperstack.tif files for further analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed in R (60) using R studio (61) and the following packages: ggplot2 (62), svglite, plyr, and tidyR. Individual measurements are provided in supplemental tables and files. Depending on the type of variable, the following tests were performed. For continuous measurement variables, the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test was used with a Dunn post hoc and P-values adjusted with the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method. Data were also compared using an ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. Brood sizes were compared using a pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as a Mann–Whitney U test). For categorical measurement variables, the Pearson's χ2 test of independence was used with post hoc P-values adjusted with the FDR method. Statistical comparisons were made between mutant and WT animals of the same age, with the exception noted in the supplemental tables and figure legends. In the text, all data are represented as mean ± SD. All error bars shown in figures represent the mean ± SD. NS indicates P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the E. coli stock center for MG1693; Wormbase; the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40OD010440) for strains; Charles Baer for VX02253; the Kimble Lab for JK5500; Aiping Feng for reagents; Andrea Scharf, Sandeep Kumar, Ariz Mohammad, and John Brenner for training, advice, support, reagents, and helpful discussion; and Andrea Scharf for feedback on this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Zuzana Kocsisova, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA; Department of Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Elena D Bagatelas, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Jesus Santiago-Borges, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Hanyue Cecilia Lei, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Brian M Egan, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Matthew C Mosley, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Aaron M Anderson, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Daniel L Schneider, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Tim Schedl, Department of Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Kerry Kornfeld, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, St. Louis, MO 63108, USA.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at PNAS Nexus online.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG02656106A1, R56 AG072169, and R01 AG057748 to K.K., R35 GM152192 to T.S.), a U.S. National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowship (DGE-1143954 and DGE-1745038 to Z.K.), and a Douglas Covey fellowship to Z.K.. Neither the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Science Foundation, nor Douglas Covey had any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Z.K., T.S., and K.K. designed the study. Z.K., E.D.B., J.S.-B., H.C.L., B.M.E., M.C.M., and D.L.S. performed the experiments. Z.K., E.D.B., J.S.-B., and H.C.L. analyzed data. Z.K. wrote the manuscript. Z.K., A.M.A., T.S., and K.K. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Preprints

This manuscript was posted on a preprint: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.04.482923.

Data Availability

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information. All C. elegans strains are listed in Table S4 and available upon request. No genome-wide datasets were generated for this study. Table S1 contains numeric data for Fig. 1. Table S2 contains numeric data for progeny production for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and S1–S3. Table S3 contains numeric data for germline phenotypes for Figs. 3–5 and S1–S3.

References

- 1. Scharf A, Pohl F, Egan BM, Kocsisova Z, Kornfeld K. 2021. Reproductive aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: from molecules to ecology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:718522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crawford NM, Steiner AZ. 2015. Age-related infertility. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 42(1):15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Athar F, Templeman NM. 2022. C. elegans as a model organism to study female reproductive health. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 266:111152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Byerly L, Cassada RC, Russell RL. 1976. The life cycle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. I. Wild-type growth and reproduction. Dev Biol. 51(1):23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCarter J, Bartlett B, Dang T, Schedl T. 1999. On the control of oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 205(1):111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pickett CL, Dietrich N, Chen J, Xiong C, Kornfeld K. 2013. Mated progeny production is a biomarker of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda). 3(12):2219–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kocsisova Z, Kornfeld K, Schedl T. 2019. Rapid population-wide declines in stem cell number and activity during reproductive aging in C. elegans. Development. 146(8):dev173195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andux S, Ellis RE. 2008. Apoptosis maintains oocyte quality in aging Caenorhabditis elegans females. PLoS Genet. 4(12):e1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Angeles-Albores D, et al. 2017. The Caenorhabditis elegans female-like state: decoupling the transcriptomic effects of aging and sperm status. G3 (Bethesda). 7(9):2969–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gems D, et al. 1998. Two pleiotropic classes of daf-2 mutation affect larval arrest, adult behavior, reproduction and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 150(1):129–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hughes SE, Evason K, Xiong C, Kornfeld K. 2007. Genetic and pharmacological factors that influence reproductive aging in nematodes. PLoS Genet. 3(2):e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hughes SE, Huang C, Kornfeld K. 2011. Identification of mutations that delay somatic or reproductive aging of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 189(1):341–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luo S, Shaw WM, Ashraf J, Murphy CT. 2009. TGF-ß Sma/Mab signaling mutations uncouple reproductive aging from somatic aging. PLoS Genet. 5(12):e1000789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qin Z, Hubbard EJ. 2015. Non-autonomous DAF-16/FOXO activity antagonizes age-related loss of C. elegans germline stem/progenitor cells. Nat Commun. 6(1):7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Templeman NM, et al. 2018. Insulin signaling regulates oocyte quality maintenance with age via cathepsin B activity. Curr Biol. 28(5):753–760.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Templeman NM, Cota V, Keyes W, Kaletsky R, Murphy CT. 2020. CREB non-autonomously controls reproductive aging through hedgehog/patched signaling. Dev Cell. 54(1):92–105.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang MC, Oakley HD, Carr CE, Sowa JN, Ruvkun G. 2014. Gene pathways that delay Caenorhabditis elegans reproductive senescence. PLoS Genet. 10(12):e1004752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar S, et al. 2019. Lifespan extension in C. elegans caused by bacterial colonization of the intestine and subsequent activation of an innate immune response. Dev Cell. 49(1):100–117.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. 2013. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 153(6):1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schultz MB, Sinclair DA. 2016. When stem cells grow old: phenotypes and mechanisms of stem cell aging. Development. 143(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goodell MA, Rando TA. 2015. Stem cells and healthy aging. Science. 350(6265):1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oh J, Lee YD, Wagers AJ. 2014. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Med. 20(8):870–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henderson ST, Gao D, Lambie EJ, Kimble J. 1994. lag-2 may encode a signaling ligand for the GLP-1 and LIN-12 receptors of C. elegans. Development. 120(10):2913–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kimble J, Hirsh D. 1979. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 70(2):396–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimble JE, White JG. 1981. On the control of germ cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 81(2):208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nadarajan S, Govindan JA, McGovern M, Hubbard EJ, Greenstein D. 2009. MSP and GLP-1/Notch signaling coordinately regulate actomyosin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming and oocyte growth in C. elegans. Development. 136(13):2223–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tax FE, Yeargers JJ, Thomas JH. 1994. Sequence of C. elegans lag-2 reveals a cell-signalling domain shared with Delta and Serrate of Drosophila. Nature. 368(6467):150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kershner AM, Shin H, Hansen TJ, Kimble J. 2014. Discovery of two GLP-1/Notch target genes that account for the role of GLP-1/Notch signaling in stem cell maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111(10):3739–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shin H, et al. 2017. SYGL-1 and LST-1 link niche signaling to PUF RNA repression for stem cell maintenance in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 13(12):e1007121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dayi M, et al. 2021. Additional description and genome analyses of Caenorhabditis auriculariae representing the basal lineage of genus Caenorhabditis. Sci Rep. 11(1):6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stevens L, et al. 2019. Comparative genomics of 10 new Caenorhabditis species. Evol Lett. 3(2):217–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sudhaus W, Giblin-Davis R, Kiontke K. 2011. Description of Caenorhabditis angaria n. sp. (Nematoda: Rhabditidae), an associate of sugarcane and palm weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Nematology. 13(1):61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. 1993. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 366(6454):461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hughes SE. Reproductive aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Washington University in St. Louis, Saint Louis, MO, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen J, et al. 2020. GLP-1 Notch—LAG-1 CSL control of the germline stem cell fate is mediated by transcriptional targets lst-1 and sygl-1. PLoS Genet. 16(3):e1008650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohammad A, et al. 2018. Initiation of meiotic development is controlled by three post-transcriptional pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 209(4):1197–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Michaelson D, Korta DZ, Capua Y, Hubbard EJ. 2010. Insulin signaling promotes germline proliferation in C. elegans. Development. 137(4):671–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brenner JL, Schedl T. 2016. Germline stem cell differentiation entails regional control of cell fate regulator GLD-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 202(3):1085–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Korta DZ, Tuck S, Hubbard EJ. 2012. S6k links cell fate, cell cycle and nutrient response in C. elegans germline stem/progenitor cells. Development. 139(5):859–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Austin J, Kimble J. 1987. glp-1 is required in the germ line for regulation of the decision between mitosis and meiosis in C. elegans. Cell. 51(4):589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kimble J, Ward S. 1988. Germ-line development and fertilization. Cold Spring Harbor Monograph Archive. 17:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nayak S, Goree J, Schedl T. 2005. fog-2 and the evolution of self-fertile hermaphroditism in Caenorhabditis. PLoS Biol. 3(1):e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schedl T, Kimble J. 1988. fog-2, a germ-line-specific sex determination gene required for hermaphrodite spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 119(1):43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hodgkin J, Barnes TM. 1991. More is not better: brood size and population growth in a self-fertilizing nematode. Proc Biol Sci. 246(1315):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kanzaki N, et al. 2018. Biology and genome of a newly discovered sibling species of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 9(1):3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Woodruff GC, Phillips PC. 2018. Field studies reveal a close relative of C. elegans thrives in the fresh figs of Ficus septica and disperses on its Ceratosolen pollinating wasps. BMC Ecol. 18(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Woodruff GC, Johnson E, Phillips PC. 2019. A large close relative of C. elegans is slow-developing but not long-lived. BMC Evol Biol. 19(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jones OR, et al. 2014. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Nature. 505(7482):169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mitteldorf JJ, Goodnight C. 2013. Post-reproductive life span and demographic stability. Biochemistry (Mosc). 78(9):1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lohr JN, Galimov ER, Gems D. 2019. Does senescence promote fitness in Caenorhabditis elegans by causing death? Ageing Res Rev. 50:58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arantes-Oliveira N, Apfeld J, Dillin A, Kenyon C. 2002. Regulation of life-span by germ-line stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 295(5554):502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ewald CY, Landis JN, Porter Abate J, Murphy CT, Blackwell TK. 2015. Dauer-independent insulin/IGF-1-signalling implicates collagen remodelling in longevity. Nature. 519(7541):97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel DS, et al. 2008. Clustering of genetically defined allele classes in the Caenorhabditis elegans DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor. Genetics. 178(2):931–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Podshivalova K, Kerr RA, Kenyon C. 2017. How a mutation that slows aging can also disproportionately extend end-of-life decrepitude. Cell Rep. 19(3):441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fox PM, Schedl T. 2015. Analysis of germline stem cell differentiation following loss of GLP-1 Notch activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 201(1):167–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee C, Sorensen EB, Lynch TR, Kimble J. 2016. C. elegans GLP-1/Notch activates transcription in a probability gradient across the germline stem cell pool. ELife. 5:e18370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Han SK, et al. 2016. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget. 7(35):56147–56152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kocsisova Z, Mohammad A, Kornfeld K, Schedl T. 2018. Cell cycle analysis in the C. elegans germline with the thymidine analog EdU. J Vis Exp. 140:e58339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Francis R, Barton MK, Kimble J, Schedl T. 1995. gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 139(2):579–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; 2013. [accessed 2021]. http://www.r-project.org/.

- 61. RStudio Team . RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; 2015. [accessed 2021]. www.rstudio.com/.

- 62. Wickham H. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information. All C. elegans strains are listed in Table S4 and available upon request. No genome-wide datasets were generated for this study. Table S1 contains numeric data for Fig. 1. Table S2 contains numeric data for progeny production for Figs. 2, 4, 5, and S1–S3. Table S3 contains numeric data for germline phenotypes for Figs. 3–5 and S1–S3.