Abstract

Background

Tooth avulsion is a severe type of dental trauma requiring immediate response and management. Timely treatment according to International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) protocols is important in achieving an optimal outcome. This study aimed to assess the knowledge, perception, and clinical practices of dental professionals located in Sanaa, Yemen, in regard to the management of avulsed teeth.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using a validated questionnaire with 25 closed-ended items that assessed demographics, generalized knowledge of traumatic dental injuries (TDIs), and clinical management of avulsed teeth. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and chi-square tests to determine whether differences are statistically significant (α = 0.05).

Results

A total of 202 individuals completed the shared questionnaire. The majority (87.62%) of the participants recognized that a knocked-out tooth should be reinserted, 40.10% knew about the ideal transport medium for an avulsed tooth, and 63.86% acknowledged the critical time period for successful replantation. Statistically significant differences were noted between the correct and incorrect responses of knowledge items (all p < 0.05), except items related to splinting type and the prognosis of an avulsed tooth. The overall percentage of correct responses to all questions was 69.19%.

Conclusion

The knowledge of dentists in relation to the clinical management of dental avulsions was moderate but inadequate, and certain aspects of the proper management protocol for avulsed teeth could still be improved. Thus, improvement is needed regarding the effective handling of avulsed tooth cases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07791-7.

Keywords: Dental trauma, Trauma management, Avulsion of permanent teeth, Dental professional, Knowledge, IADT

Introduction

Dental trauma is a common emergency in dental practice, especially in children and adolescents [1]. Trauma to dental structures varies from minor tooth fractures to extensive dento-alveolar damage involving the supporting structures, tooth displacement, or tooth avulsion [2–4]. Traumatic tooth avulsion (i.e., exarticulation or knocked-out tooth) is a type of dental trauma in which the whole tooth is displaced out of the bony socket. Globally, tooth avulsion occurs in 0.5–16% of permanent teeth and 7–13% of primary teeth [5], with remarkable regional variations found in epidemiological studies [1, 5].

This disparity highlighted the necessity for region-specific studies. Avulsion injuries in children most frequently occur between the ages of 7 and 9 years when the permanent incisors are erupting [6]. The injury typically involves a single tooth only. The tooth most commonly avulsed in the permanent dentition is the maxillary central incisor [7, 8], although primary teeth may also be avulsed. Primary teeth should not be replanted because of the potential risk of damaging the permanent successors [9].

The International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) states that immediate replantation or storage in physiologic media, such as Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), milk, or saline, is necessary to preserve periodontal ligament (PDL) cell viability and ensure favorable long-term outcomes [10]. Despite the presence of IADT guidelines, which are readily available on the IADT website (www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org), global awareness among dental practitioners remains inconsistent. Previous research in countries like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, and Malaysia has indicated varying degrees of awareness and practice deficiencies regarding dental avulsion [11–17].

Several studies have investigated dentists’ knowledge and awareness about avulsed teeth in children and adults, highlighting the necessity for educational systems to enhance the prognosis of avulsed teeth [3, 4, 11, 13–21]. All those studies emphasized the importance of managing avulsed teeth for effective treatment and focused on points that assist various dental clinicians in preserving the health of avulsed teeth.

To our knowledge, no previous study specifically focused on dental professionals in Sanaa City, Yemen, regarding avulsion management knowledge and practice. Although a single earlier study did cover emergency management of avulsed teeth on a national level [12]. This is a serious gap in the literature, considering that proper and timely intervention is crucial in such situations [5, 7, 22]. Thus, this study aimed to fill this gap by investigating the knowledge, perception, and clinical management of traumatic tooth avulsion among dental practitioners in Sanaa City, Yemen, in alignment with IADT guidelines to determine areas for improvement.

Participants and methods

Study design and ethical considerations

A descriptive cross-sectional study based on a self-administered questionnaire was carried out among dental professionals working in various dental clinics in Sanaa City, Yemen, from April 2024 to May 2024. A cross-sectional design was chosen to effectively assess current levels of knowledge, given that longitudinal observation was impractical because of time limitations. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sciences and Technology, Sann, Yemen (MEC/AD009, 04/05/2024). All participants provided written informed consent after being fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks, and were informed that they could discontinue the questionnaire at any time without providing a reason. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines [23].

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4, University of Dusseldorf) in accordance with the dental professionals (specialists and general practitioners 5 years post-graduation) in Sanaa City, Yemen. The effect size (d), alpha (α), and 1 − β (power) were 0.5, 0.05, and 0.80, respectively. Based on this sample size estimation, a minimum sample size of 128 was required to obtain valid, statistically significant results. To consider non-responders, we invited a sample of 220 dentists to participate through a stratified random sampling technique based on clinic type, geographical location, and years of experience.

Study setting and participant criteria

Different dental professionals were randomly selected from various areas of Sanaa City, Yemen, to ensure a representative sample. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary. A total of 220 questionnaires, written in Arabic and English, were distributed to dental professionals across different locations. The inclusion criteria were practicing dentists at Sana’a City during the study period, willingness to sign informed consent, and ability to understand English or Arabic. The exclusion criteria were non-practicing dentists, interns without clinical practice, and those who did not complete or left the questionnaire blank.

Data collection

A validated questionnaire was developed in Arabic and English and was used as a primary tool for this study. It was mainly distributed to participants in two ways. Initially, in-person distribution: Trained dental demonstrators visited dental clinics in Sanaa City, explained the study’s goals, and invited eligible dental professionals to take part. Respondents were requested to complete the questionnaires on the spot under supervision, ensuring completeness and addressing any questions. Additionally, online distribution: to enhance both coverage and participant convenience, the questionnaire was also shared via Google Forms. The link, which included the consent form, was sent directly to participants through WhatsApp. In both methods of distribution, participants’ responses were collected, anonymized, and stored in a secure database for analysis.

Questionnaire tools

The questionnaire was self-administered and directly distributed to dentists who were required to complete it. Specifically created for this study, the questionnaire’s content was validated based on previous studies, with some modifications [3, 4, 6, 11, 13–21, 24] (Supplementary File 1). The study questionnaires were proposed in Arabic with the help of a native Arabic speaker; thereafter, the questions were subjected to forward and backward translation into English [25, 26].

Questionnaire development and pilot test

A panel of five experts consisted of two prosthodontists and three maxillofacial surgeons. The clarity, relevance, and simplicity of each item were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The Content Validity Index (CVI) was 0.93, indicating excellent validity. A pilot test of the instrument was conducted on 15 selective dentists (excluded from final analysis) to assess its clarity, readability, and response time. The result of this pilot testing led to revisions and rewordings that improved the instrument’s readability and clarity.

Reliability test

Internal consistency and test–retest procedures were used to measure reliability. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated using SPSS (version 26) and yielded a coefficient of 0.875, which indicated high reliability [27]. The final instrument was deemed statistically sound and conceptually valid for implementation. Rounded boxes were provided, and the dental professional in Sanaa City had to tick one choice only per question. Contributors could only respond to the questionnaire once, and all questions needed to be answered. The questionnaires’ outputs were directly organized via Google Forms. Informed consent was included and requested in the Google Form, and the questionnaire copies were sent through WhatsApp.

Questionnaire parts

The questionnaire consisted of 25 closed-ended questions divided into three main sections in Arabic and English, serving as the principal information and data collection instrument for the survey. The first part of the questionnaire included five questions related to participants’ demographic characteristics, namely, age, gender, years of practice, clinical profession or specialty, and work setting. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of seven questions, with five of them relating to knowledge and attitude toward TDIs with a yes/no response. The questions were approved from TDI A. Meanwhile, the other two were related to the practice of TDI [5, 17]. One of them was ‘’Did you attend any educational program regarding traumatic dental injuries to teeth,’’ with an answer of yes or no, and the other was related to ‘’The number of dental avulsion cases encountered per year,’’ and it offered many answer choices.

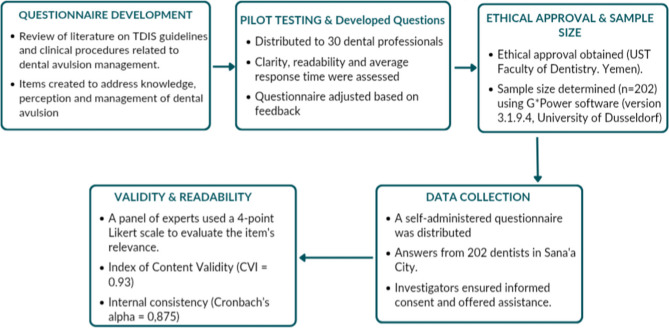

The third section of the questionnaire (13 questions) focused on emergency and clinical management of avulsed teeth, and the questions were based on the guidelines of the lADT. It was further subdivided into five groups of questions. Group 1 addressed the significance of replanting an avulsed permanent tooth immediately and not replanting a primary tooth because of the potential risk of damaging the permanent successors, and it consisted of four questions. Group 2 asked two questions on the appropriate storage medium to use and how to properly clean the avulsed tooth prior to replantation. Group 3 comprised two questions about the appropriate splint type and duration to stabilize a replanted tooth. Group 4 involved three questions focused on post-replantation tooth management, specifically about root canal treatment (RCT) and its complications. Lastly, group 5 included two questions regarding the duration of follow-up and the prescription of antibiotics. The correct answers for the questions in this section (part 3) were determined by referring to the 2012 avulsion guidelines of lADT [10]. Upon receipt, the completed surveys were immediately identified, gathered from the participants, numbered, and organized in an Excel sheet for statistical analysis. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the questionnaire development and the steps of study.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the questionnaire development

Statistical analysis

SPSS software, version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Excel Sheet were used to analyze the data. The correct responses in each section were identified. Descriptive statistics frequency and percentages) were analyzed. The association between the demographic variables of the participants and their knowledge-based item responses was assessed using the chi-square (x²) test. This statistical test was considered suitable due to the categorical nature of the data and sample size. The level of statistical significance was determined with a cutoff value of p < 0.05.

Results

Of the 220 dental professionals, 202 returned the completed questionnaires (response rate 91.8%). The participants’ ages ranged from 24 years to 65 years. The majority of participants were male (65.84%) and general practitioners (49.5%). Over half (56.44%) had five or fewer years of clinical experience, and more than half (58.41%) worked in private practice settings. The demographic characteristics varied significantly across age groups, specialties, and years of experience (p < 0.05), indicating that demographic and professional factors may substantially influence preparedness for managing TDIs Table 1. These findings suggest that targeted educational interventions could be particularly beneficial for early-career clinicians and those in general practice, who may lack exposure to specialized trauma protocols.

Table 1.

Response of respondents’ characteristics and experiences via chi-square test (n = 202)

| Parmeter | Category | Number | Percents | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (in years) | 20–25 | 48 | 23.76 | 63.426 | < 0.0001* |

| 26–30 | 63 | 31.19 | |||

| 31–35 | 41 | 20.30 | |||

| 36–40 | 26 | 12.87 | |||

| 41–45 | 15 | 7.43 | |||

| More than 46 | 9 | 4.46 | |||

| Gender | Male | 133 | 65.84 | 20.277 | < 0.0001* |

| Female | 69 | 34.16 | |||

| Number of years in practice | 0–5 | 114 | 56.44 | 181.218 | < 0.0001* |

| 6–10 | 41 | 20.30 | |||

| 11–15 | 20 | 9.90 | |||

| 16–20 | 18 | 8.91 | |||

| More than 20 years | 9 | 4.46 | |||

| Specialty | General Practitioner | 100 | 49.50 | 305.089 | < 0.0001* |

| Intern | 39 | 19.31 | |||

| Maxillo-facial/Oral surgeon | 29 | 14.36 | |||

| Orthodontist | 17 | 8.42 | |||

| Endodontist | 12 | 5.94 | |||

| Pedodontics | 2 | 0.99 | |||

| Prosthodontist | 1 | 0.50 | |||

| Other | 2 | 0.99 | |||

| Work setting | Private practice | 118 | 58.42 | 58.257 | < 0.0001* |

| Public hospital | 48 | 23.76 | |||

| Mixed | 36 | 17.82 |

* Significant difference by chi-square test, p < 0.05

Table 2 displays the participants’ perceived knowledge and awareness of TDIs and tooth avulsion. Overall, participants showed a moderate level of knowledge in which 66.83% understood dental injuries, and 68.81% correctly identified a knocked-out tooth. However, 58.91% were aware of IADT guidelines. Even though 40% had received formal training on traumatic dental injuries. This lack of awareness about guidelines and structured education is concerning because following evidence-based protocols is essential for the best outcomes in dental trauma cases. Additionally, nearly half (47.03%) of the respondents reported that they had not encountered any avulsion cases in the past year. This may lead to a lack of confidence and practical skills. These findings point to the need for better ongoing education programs, especially for practitioners in environments where traumatic injuries are less common. This underscores how demographic and experiential factors affect clinical confidence and awareness p < 0.050.

Table 2.

Dental professionals’ knowledge and practice regarding traumatic dental injuries (n = 202)

| Question | Category | Number | Percents | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||||

| Do you know what tooth injuries are? | Yes | 135 | 66.83 | 22.891 | < 0.0001* |

| No | 67 | 33.17 | |||

| Do you know what a knocked-out tooth is? | Yes | 139 | 68.81 | 28.594 | < 0.0001* |

| No | 63 | 31.19 | |||

| Do you have information on the avulsed teeth? | Yes | 141 | 69.80 | 31.683 | < 0.0001* |

| No | 61 | 30.20 | |||

| Do you have information regarding the guidelines of the International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT)? | Yes | 119 | 58.91 | 6.416 | 0.011* |

| No | 83 | 41.09 | |||

| Do you know what tooth replantation is? | Yes | 127 | 62.87 | 13.386 | 0.0003* |

| No | 75 | 37.13 | |||

| Practice | |||||

| Did you attend any educational programs regarding traumatic dental injuries to teeth | Yes | 78 | 38.61 | 10.475 | 0.001* |

| No | 124 | 61.39 | |||

| The number of dental avulsion cases encountered in a year | 0 | 95 | 47.03 | 235.465 | < 0.0001* |

| 1–5 | 71 | 35.15 | |||

| 6–20 | 24 | 11.88 | |||

| 21–50 | 9 | 4.46 | |||

| 51–100 | 2 | 0.99 | |||

| > 100 | 1 | 0.50 | |||

* Significant difference by chi-square test, p < 0.05

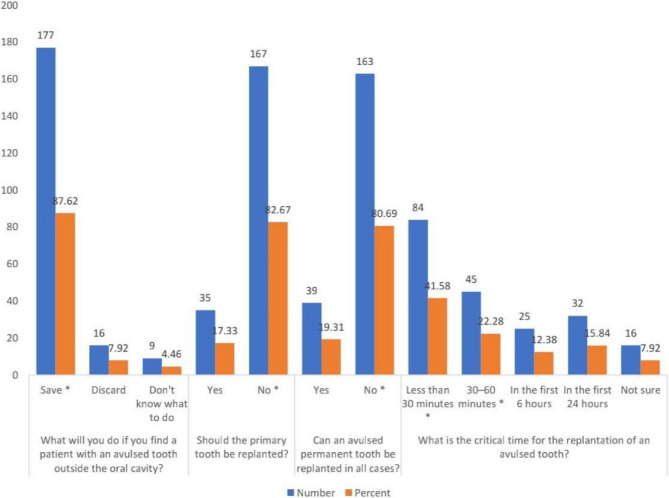

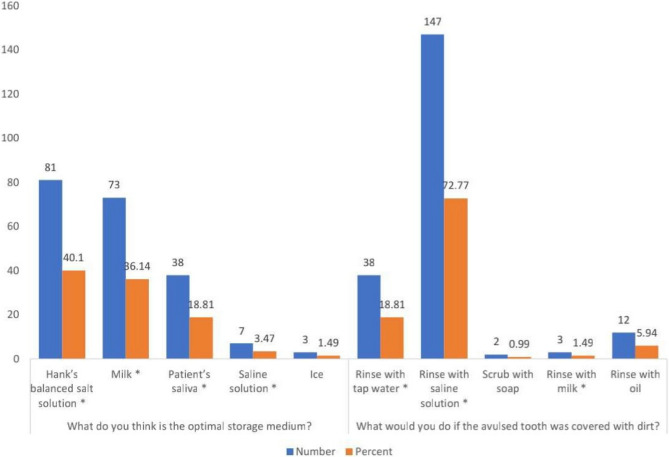

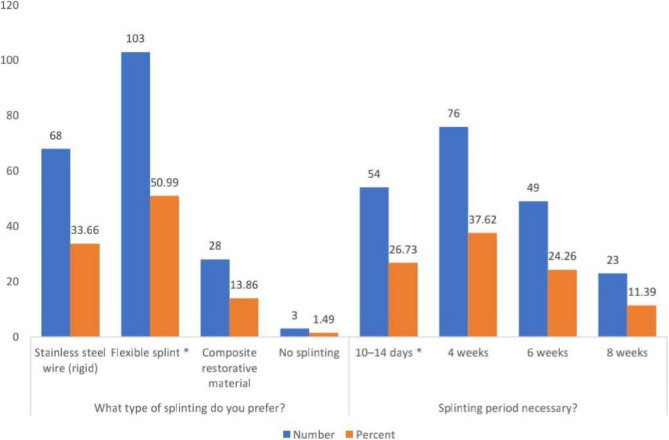

When assessing knowledge regarding the immediate emergency and clinical management of avulsed permanent teeth decision-making in relation to IADT, respondents showed strong adherence to some IADT recommendations but had inconsistencies in time-sensitive and technical aspects of avulsion management. For example, the majority (87.62%) recognized that the importance of preserving an avulsed tooth, and 82.67% correctly advised against replanting primary teeth. 41.58% of the respondents recognized the evidence-based replantation window of less than 30 min (Fig. 2). Knowledge of optimal storage media was unclear: 40.10% chose HBSS, and 36.14% preferred milk (Fig. 3). Regarding avulsed teeth fixation and stabilization, flexible splinting was the preferred way at 50.99% and most participants (73.26%) recommended splinting durations that exceeded the IADT’s 7-to-14-day guideline (Fig. 4). This suggests a gap between current evidence and clinical practice, and post-replantation care also showed variability.

Fig. 2.

Response of significance of replanting an avulsed permanent tooth immediately. * Correct Response (Andersson et al., IADT, 2012) [10]

Fig. 3.

Response of appropriate storage medium. * Correct Response (Andersson et al., IADT, 2012) [10]

Fig. 4.

Response of splint type and duration. * Correct Response (Andersson et al., IADT, 2012) [10]

Only more than third (38.12%) of participants correctly indicated that they would conduct an RCT 7–10 days after replantation if the tooth possessed a fully formed and closed apex. Moreover, the ratios of correct responses for potential complications following tooth replantation, such as ankylosis, pulp necrosis, and root resorption, were significantly low at 35.14%, 26.73%, and 22.77%, respectively (Fig. 5). In addition, most participants (64.85%) understood follow-up protocols and antibiotic use, but there was some confusion about topical antibiotic application and long-term recall intervals. These trends indicate a gap between participants’ theoretical knowledge and effective clinical decision-making (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Response of management and complications of the tooth after replantation. * Correct Response (Andersson et al., IADT, 2012) [10]

Fig. 6.

Response of follow-up duration and antibiotic prescription. * Correct Response (Andersson et al., IADT, 2012) [10]

Table 3 shows the response percentages and chi-square test results in relation to the correct and incorrect answers related to dental avulsion via knowledge-based questions. While over 80% of participants correctly answered questions about tooth preservation and primary tooth replantation, performance declined for time-critical and procedural items. While, only 26.73% correctly answered questions on splinting duration. Follow-up protocols and antibiotic use were well understood, with correct rates between 64.85% and 66.34%. However, this gaps in foundational knowledge, like replantation timing and storage media, indicate that current training programs might not adequately cover these key concepts. The statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) across all knowledge areas, except for splinting type (p = 0.778), highlight the need for standardized, competency-based education to address these gaps. Overall, these results stress the importance of incorporating IADT guidelines into dental curricula and continuing education, focusing on high-fidelity simulations to improve time-sensitive decision-making and technical skills.

Table 3.

Statistical test between correct and incorrect responses on dental avulsion via knowledge-based questions (n = 202)

| (n) Questions | Correct Response No (%) |

Incorrect Response No (%) |

Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (13) What will you do if you find a patient with an avulsed tooth outside the oral cavity? | 177 (87.62) | 25 (12.38) | 114.376 | < 0.0001* |

| (14) Should the primary tooth be replanted? | 167 (82.67) | 35 (17.33) | 86.257 | < 0.0001* |

| (15) Can an avulsed permanent tooth be replanted in all cases? | 163 (80.69) | 39 (19.31) | 76.119 | < 0.0001* |

| (16) What is the critical time for the replantation of an avulsed tooth? | 129 (63.86) | 73 (36.14) | 15.525 | < 0.0001* |

| (17) What do you think is the optimal storage medium? | 199 (98.51) | 3 (1.49) | 190.178 | < 0.0001* |

| (18) What would you do if the avulsed tooth was covered with dirt? | 188 (93.97) | 14 (6.93) | 149.881 | < 0.0001* |

| (19) What type of splitting do you prefer? | 103 (50.99) | 99 (49.01) | 0.079 | 0.778 |

| (20) Splinting period necessary? | 54 (26.73) | 148 (73.72) | 43.743 | < 0.0001* |

| (21) Would you do root canal treatment of an avulsed and replanted tooth? | 77 (38.12) | 125 (61.88) | 11.406 | 0.001* |

| (22) What are the possible complications after tooth replantation? | 171 (84.65) | 31 (15.35) | 97.030 | < 0.0001* |

| (23) Which one has a better prognosis? | 115 (56.93) | 87 (43.07) | 3.881 | 0.049* |

| (24) Duration of follow-up period | 131 (64.85) | 71 (35.15) | 17.822 | < 0.0001* |

| (25) Is antibiotic therapy necessary after replantation? | 134 (66.34) | 68 (33.66) | 21.564 | < 0.0001* |

* Significant difference by chi-square test, p < 0.05

Discussion

Overall, knowledge and clinical preparedness

Dentists are expected to have clinical expertise; diagnostic understanding of dental issues; exceptional emergency care; and appropriate long-term follow-up for emergency treatment, repair, and maintenance of traumatized permanent teeth. The current study examined the knowledge, perception, and clinical practices of dental professionals in Sanaa, Yemen, regarding tooth avulsion management according to IADT guidelines. While 87.6% of respondents recognized the importance of replanting an avulsed permanent tooth, the overall knowledge score was 69.2%. This score shows significant gaps in evidence-based clinical management. These findings align with similar studies in developing countries like Saudi Arabia [28], Pakistan [13], and Brazil [15], where partial adherence to IADT guidelines was noted. However, Yemeni dentists’ knowledge levels seem to fall behind those in countries with strong trauma curricula, such as Turkey [18], Italy [21], and more recently, Pakistan [29], China [30], and India [31]. This suggests that trauma management is still not emphasized enough in the Yemeni dental education system. Table 4 shows a summary of the current study finding and other worldwide studies used in discussion.

Table 4.

Summary of studies included in the discussion

| Title and Reference # | Research (s), Years, Country/ (Sample size) | Reported Knowledge of Dental Avulsion Outcome | Important Aspects of Dental Avulsion Knowledge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replantation Critical time | Storage Media | Splinting Type | Splinting Period | |||

| Assessing Knowledge, Perception and Management Toward Traumatic Tooth Avulsion Among Dentists in Sana'a, Yemen: A Cross sectional Study | AL-Huthaifi et al., 2024, Yemen / (202) Dental professional | All participants showed a moderate level of knowledge. Efforts should be made to enhance the effective handling of such cases. | Less than 30 minutes: 41.58% | HBSS: 40.10% |

Flexible splint: 50.99% |

10–14 days: 26.73% |

| Milk: 36.14% | ||||||

| Awareness about emergency management of avulsed tooth among intern dentists—a cross-sectional observational study [13] | Qureshi et al., 2024,Pakistan / (152) Dental interns | Dental interns are well-informed but lack awareness about proper avulsed tooth management protocol, indicating a need for improvement. | Less than 30 minutes: 43.8% | HBSS: 49.7% | Semi-rigid with nylon wire: 21.6% |

10–14 days: 49.0% |

|

Assessing Knowledge, Perception, and Management Toward Traumatic Tooth Avulsion Among Dentists in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross Sectional Study [28] |

Albassam et al., 2023, Saudi Arabia/ (392) Dental professional | High knowledge of GDPs and post-graduate training. Need to include comprehensive treatment of avulsion emergencies in dental curricula. | More than 30 minutes: 62% | HBSS: 56.9% | Flexible: 52.8% | 7-14 days; 79.8% |

|

An Assessment of the Knowledge of Dentists on the Emergency Management of Avulsed Teeth [36] |

Sen-Yavuz et al., 2020, Turkey/ 142 GDPs | GDPs, moderate overall knowledge. | 30 minutes: 35% | Milk: 27% | Flexible splint: 56% | 2 weeks: 58.5% |

| 30-60 minutes: 42% | Patient saliva: 22% | |||||

| Knowledge of Emergency Management of Avulsed Teeth among Italian Dentists-Questionnaire Study and Next Future Perspectives [21] | Mazur et al., 2021,Italy/ (304) GDPs | Low knowledge of avulsion trauma management, need for improved knowledge among Italian dentists. | Immediately: 81.3% | Milk: 74.7% | Flexible splint: 31.6% |

10–14 days: 13.8% |

| 0–30 minutes: 8.2% | Saline: 74.7% | |||||

| Assessment of Turkish dentists’ knowledge about managing avulsed teeth [17] | Duruk and Erel, 2020,Turkey/ (400) GDPs | Moderate knowledge of Turkish dentists. Need for further education on dento-alveolar trauma. | 30 minutes: 32.8% | Cold milk: 75% | Semi-rigid (S.S. wire: 84% | 2–4 Weeks: 67.8% |

|

60 minutes: 55.5% |

Patient Saliva: 74% |

Semi-rigid (nylon wire): 37.3% | ||||

| 30 minutes: 14.04% | Milk: 13.19 | NRN | ||||

| Assessment of Turkish dentists’ knowledge about managing avulsed teeth [18] | Duruk et.al., 2020, Turkey/ (400) GDP, specialist, and pedodontics | Dentists show acceptable but inadequate Knowledge, while the knowledge of pediatric dentists was good. | 30 minutes: 32.8% | Cold milk: 75% | Semi-rigid with S.S. wire: 84% | 2–4 weeks: 67.8% |

| 60 minutes: 55.5% | Patient's saliva:74% | |||||

| Semi-rigid with S.S. wire + bracket: 54.8% | ||||||

| Hank’s solution: 52.5% | ||||||

|

60 minutes: 59.3% |

HBSS: 40% | |||||

| Awareness about Management of Tooth Avulsion among General Dental Practitioners: A Questionnaire Based Study [4] | Mustafa M, 2017, Saudi Arabia/ (148) GDPs | Aware but lacks proper management protocol, need for improving knowledge among GDPs | 30 minutes: 45% | HBSS: 68% | S. S. wire: 34% | 15 days: 39% |

| Milk: 21% | Semi-rigid nylon wire: 23% | |||||

| Knowledge of managing avulsed tooth among general dental practitioners in Malaysia [11] | Abdullah et al., 2016,Malaysia/ (182) GDPs | Moderate knowledge of GDPs, need for further improvement in their knowledge | NRN | Saliva: 85.7% |

Flexible splint: 45.6% |

7–10 days: 64.8% |

| Milk: 79.7% | ||||||

| General dentists’ knowledge about the emergency management of dental avulsion in Yemen [12] | Al-Zubair N, 2015, Yemen/ (272) GDPs | Inadequate level of knowledge of GDPs, need for further education programs. | minutes: 62% | Saliva: 40% | Semi-rigid with nylon wire: 29% | 15 days: 51% |

| HBSS: 29% | 30 days: 34% | |||||

| 60 minutes: 28% | ||||||

| Milk: 24% | ||||||

| Knowledge of Dental Interns towards Emergency Management of Avulsed Tooth in Dental Colleges in Nepal [20] | Limbu et al., 2014,Nepal/ (121) GDPs | Moderate knowledge for dental interns, need for continued education programs |

15 minutes: 55.4% |

Patients’ saliva: 50.4% | Flexible: 45.5% |

2 weeks: 33.0% |

| Milk: 47.0% | ||||||

| Knowledge of Emergency Management of Avulsed Teeth Among General Dentists in Kathmandu [14] |

Upadhyay et al., 2012, Nepal/ (102) GDPs |

Lack of knowledge among GDPs requires education in this field. | 20 minutes: 71.8% | HBSS: 59.8% | Flexible: 36.3% | 2 Weeks; 19.6% |

|

20-60 minutes: 37.3% |

Patient Saliva: 31.4% | |||||

| Knowledge of Dentists on the Management of Tooth Avulsion Injuries in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [15] | Menezes et al., 2015,Brazil/ (100) GDPs | Inadequate dental knowledge, need to improve strategies for emergency diagnosis and treatment | Time: 14.8% | Milk: 41.1% | NRN | NRN |

| Water: 42.4% | ||||||

| Saline, HBSS, milk: 18% | ||||||

| Knowledge and Attitude of Dental Interns about Management of Tooth Avulsion: A Comparative Cross - Sectional Study [38] | Aboubakr & Elkwatehy, 2020, Egypt and Saudi Arabia/ (324) Dental inters | Dental interns demonstrated adequate knowledge, motivated to attend more educational programs on traumatic tooth injuries. | 15 minutes: 43.2% | Milk: 57.7% |

Flexible splint: 44.4% |

2 weeks: 46% |

| Awareness of dentists regarding immediate management of dental avulsion: Knowledge, attitude, and practice study [39] | Zafar et al., 2018,Pakistan/ (282) GDPs | Knowledge was low, deficient, and significantly associated with the specialty and qualification of the dentist | 30 minutes: 50.0% | HBSS: 50% | NRN | NRN |

|

60 minutes: 59.3% |

HBSS: 40% | |||||

NRN Not Reported Knowledge, GDPs General Dental Practitioners, HBSSHanks' balanced salt solution, S.S. Stainless steel, PDS Preclinical dental student, CDS Clinical dental student, MS Medical student, TMS Training medical student

Critical time awareness and emergency management

The period of extraoral dry time is a critical factor in the prognosis of replantation within 30 min or less is a key predictor of a successful outcome and the association between the dry time and ankylosis as well as resorption as highlighted by IADT guidelines [10]. Yu et al., only 41.6% of respondents correctly identified this golden time window [30]. By contrast, recent studies in Italy (81.3%) [21], Saudi Arabia (62%) [28], Grigore (69.39%) [24], and Turkey (55.5%) [18] show far greater awareness. This discrepancy may highlight not only knowledge gaps but also limited continuing education opportunities; only 38.6% of Yemeni dentists have attended any educational program on dental trauma. This suggests the urgent need for accessible and required training modules that focus on emergency management and the biological effects of delayed replantation, such as replacement resorption and ankylosis [32].

Storage media awareness and practical difficulties

Despite the clear recommendation of HBSS as the best storage medium, which helps preserve PDL cell viability for up to 48 h [29], only 40.10% of participants chose it. Similar shortcomings were found in studies conducted in India (49%) [3] and Pakistan (49.7%) [13]. The preference for milk (36.1%) matches findings from Malaysia [11] and Brazil [15], where HBSS is either hard to find or too expensive. A recent systematic review by Lin et al. (2025) highlighted milk as a practical and accessible alternative, especially in places with limited resources [33]. Since access to HBSS is limited in Yemen, training programs should change their protocols. They should focus on affordable and clinically acceptable alternatives. This can enhance the feasibility of guideline implementation in low-resource settings.

Splinting methods and duration

The IADT recommends the application of a flexible splint for 7–14 days to facilitate physiological movement and periodontal repair [34]. In the current study, we found that 50.99% of dentists favored flexible splints, only 26.73% of dentists correctly suggested the duration of 7–14 days for splint usage, and 37.62% incorrectly suggested a duration of 4 weeks. Previous studies in Nepal [20] and Saudi Arabia [3] similarly reported rigid splinting and long fixation times, such as 4 or 6 weeks. This indicates a persistent misconception that extended fixation yields superior treatment outcomes and fosters the optimal healing environment. Unfortunately, improper and prolonged splinting is associated with an increased risk of ankylosis [35]. Future training workshops on splinting practice should include a clear learning module on the biomechanical principles of splinting and the therapeutic importance of early functional mobilization.

Root canal treatment and follow-up protocols

The IADT recommends RCT for mature, closed apex teeth 7–10 days after replantation to reduce the risk of inflammatory resorption. In this study, only 38.12% of Yemeni dentists performed RCT within the intervention period, and 29.70% of dentists followed a “wait and see” approach. By contrast, in Turkey, 73.3% of dentists who attempted the RCT intervention executed it in the correct duration of 7–10 days [36]. The reluctance to provide timely RCT may stem from fear and anxiety, concerns that treatment could exacerbate an already unfortunate situation, or a lack of confidence in endodontic management. Similarly, 66.34% of dentists recognized the need for systemic antibiotics regardless of the presence of clinical infection indications, whereas 21.78% believed that topical antibiotics only were adequate. This work highlights the need for further education and postgraduate training for dentists in Yemen on the IADT recommendations or the need for evidence-based practice related to post-replantation care.

Obstacles to ideal avulsion management in yemen

Several systemic barriers hinder effective avulsion management in Yemen. Continuing education remains limited; only 38.61% of dentists attended continuing education related to trauma, which was much less than rates reported in Turkey [18] and Malaysia [11]. Additionally, insufficient resources, particularly the lack of HBSS and quality dental materials, prevents IADT clinicians from adhering to IADT protocols [12]. Clinical inertia is also apparent, as many dentists continue to place rigid splints and delay root canal therapy, disregarding changes suggested by the current evidence base [10].

Policy and practice recommendations

Several feasible and policy interventions can help in bridging these gaps. First, Yemen-specific national trauma guidelines must be developed, incorporating the IADT recommendations but considering the limitations of local resources. Second, mandatory dental trauma courses (modules) should be included as part of licensing renewal processes; many initiatives have been implemented to achieve this objective, including those introduced in Turkey [18]. Third, community-level public awareness campaigns that focus on schoolteachers and parents would promote first-response behaviors to provide systemic care for patients experiencing dental trauma, as explained by Shamarao et al. (2014) [37].

Study limitations, and suggestion

This study employed a cross-sectional study design, which limits causal relationships. In addition, self-reported data are susceptible to social desirability bias, thereby inflating perceived levels of knowledge. The study was only conducted on dental professionals in Sanaa City, which likely excluded rural practices and diminished generalizability. Future studies should evaluate wide geographic sampling and assess long-term knowledge retention through a longitudinal methodology design.

Conclusion

Yemeni dentists demonstrated moderate knowledge of avulsion management; nonetheless, significant deficiencies remained regarding replantation time, selection of storage media, and splinting techniques. These gaps require multiple levels of changes, including mandatory IADT protocol certification for licensure, standardized trauma kits with HBSS alternatives and flexible splints, tele-mentoring programs to connect urban and rural areas, and the need for training in trauma management. Future studies should evaluate the cost-effectiveness of these interventions while monitoring long-term clinical educational interventions outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Basem H. AL-Huthaifi and Mohammed M Al Moaleem, Abdulmajeed Okshah, Sahl Waleed Al-Qubati: Conceived and designed experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; Wrote the paper. Basem H. AL-Huthaifi and Mohammed M Al Moaleem, Abdulhamid Al Ghwainem, Adel S. Alqarni: Conceived and designed experiments; Wrote the paper. Abdulhamid Al Ghwainem, Adel S. Alqarni, Muadh A. AlGomaiah, Khalid K Alshamrani: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data. Ashraf Mohammed Alhumaidi, Abdulaziz Abdullah Asiri: Analyzed and interpreted data.

Funding

No funding was received.

Data availability

Data associated with the study have not been deposited into a publicly available repository. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sciences and Technology, Sann, Yemen (MEC/AD009, 04/05/2024). All participants provided written informed consent after being fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks, and were informed that they could discontinue the questionnaire at any time without providing a reason.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Antipovienė A, Narbutaitė J, Virtanen JI. Traumatic dental injuries, treatment, and complications in children and adolescents: a register-based study. Eur J Dent. 2021;15:557–62. 10.1055/s-0041-1723066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venugopal M. Recent advances in transport medium for avulsed tooth: a review. Amrita J Med. 2022;18(2):37–44. 10.4103/AMJM.AMJM_34_21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustafa M. Assessment of knowledge and practice in management of tooth avulsion among dental clinicians: A cross-sectional study. Med Sci. 2021;25(118):3326–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mustafa M. Awareness about management of tooth avulsion among general dental practitioners: a questionnaire based study. J Orthod Endod. 2017;3:1–8. 10.21767/2469-2980.100036. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouad AF, Abbott PV, Tsilingaridis G, Cohenca N, Lauridsen E, Bourguignon C, O’Connell A, Flores MT, Day PF, Hicks L, Andreasen JO, Cehreli ZC, Harlamb S, Kahler B, Oginni A, Semper M, Levin L. International association of dental traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4):331–42. 10.1111/edt.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loo TJ, Gurunathan D, Somasundaram S. Knowledge and attitude of parents with regard to avulsed permanent tooth of their children and their emergency management–Chennai. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2014;32(2):97–107. 10.4103/0970-4388.130781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saputra DS, Prayogo RD, Herninda PA, Puteri MM, Wahluyo S. Management of avulsion tooth within golden period in young permanent tooth. World J Adva Res Reviews. 2024;22(02):1553–6. 10.30574/wjarr.2024.22.2.1565. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parthasarathy R, Srinivasan S, Thanikachalam CV, Ramachandran Y. An interdisciplinary management of avulsed maxillary incisors: A case report. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e23891. 10.7759/cureus.23891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martins-Júnior PA, Franco FA, de Barcelos RV, Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML. Replantation of avulsed primary teeth: a systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24(2):77–83. 10.1111/ipd.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Day P, Heithersay G, Trope M, Diangelis AJ, Kenny DJ, Sigurdsson A, Bourguignon C, Flores MT, Hicks ML, Lenzi AR, Malmgren B, Moule AJ, Tsukiboshi M, International Association of Dental Traumatology. International association of dental traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28(2):88–96. 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdullah D, Soo SY, Kanagasingam S. Knowledge of managing avulsed tooth among general dental practitioners in Malaysia. Singap Dent J. 2016;37:21–6. 10.1016/j.sdj.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Zubair NM. General dentists knowledge about the emergency management of dental avulsion in Yemen. Saudi J Oral Sci. 2015;2(1):25–9. 10.4103/1658-6816.150588. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qureshi R, Iqbal A, Siddanna S, Siddeeq U, Mushtaq F, Arjumand B, Khattak O, Sarfarz S, Aljunaydi NAN, Mohammed Alkhaldi AM, Altassan M, Attar EA, Issrani R, Prabhu N. Awareness about emergency management of avulsed tooth among intern dentists-a cross-sectional observational study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2024;48(2):64–71. 10.22514/jocpd.2024.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyay S, Rokaya D, Upadhayaya C. Knowledge of emergency management of avulsed teeth among general dentists in Kathmandu. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10(38):37–40. 10.3126/kumj.v10i2.7341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menezes MC, Carvalho RG, Accorsi-Mendonça T, De-Deus G, Moreira EJ, Silva EJ. Knowledge of dentists on the management of tooth avulsion injuries in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13(5):457–60. 10.3290/j.ohpd.a33923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alaslami RA, Elshamy FMM, Maamar EM, Ghazwani YH. Awareness about management of tooth avulsion among dentists in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(9):1712–5. 10.3889/oamjms.2018.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duruk G, Daşkıran IC. Evaluation of knowledge on emergency management of avulsed teeth among Turkish medical students. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria. 2022;22:1–9. 10.1590/pboci.2022.057. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duruk G, Erel ZB. Assessment of Turkish dentists’ knowledge about managing avulsed teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4):371–81. 10.1111/edt.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzarevic Z, Ivanisevic Z, Karl M, Tukara M, Karl D, Matijevic M. Knowledge on pre-hospital emergency management of tooth avulsion among Croatian students of the faculty of education. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19): 7159. 10.3390/ijerph17197159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limbu S, Dikshit P, Bhagat T, Mehata S. Knowledge of dental interns towards emergency management of avulsed tooth in dental colleges in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2014;12(26):1–7. PMID: 25574976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazur M, Jedliński M, Janiszewska-Olszowska J, Ndokaj A, Ardan R, Nardi GM, Marasca R, Ottolenghi L, Polimeni A, Vozza I. Knowledge of emergency management of avulsed teeth among Italian dentists-questionnaire study and next future perspectives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2): 706. 10.3390/ijerph18020706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ram D, Cohenca N. Therapeutic protocols for avulsed permanent teeth: review and clinical update. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26(3):251–5 PMID: 15185807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murariu A, Baciu ER, Bobu L, Stoleriu S, Vasluianu RI, Tatarciuc MS, Diaconu-Popa D, Huțanu P, Gelețu GL. Evaluation of knowledge and practice of resident dentists in Iasi, Romania in the management of traumatic dental injuries: a cross-sectional study. Healthcare. 2023;11(9): 1348. 10.3390/healthcare11091348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syed W, Al-Rawi MBA, Bashatah A. Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical trials: a questionnaire-based study of 179 male third- and fourth-year pharmd undergraduates from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e943468. 10.12659/MSM.943468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Moaleem MM, Al Ahmari NM, Alqahtani SM, Gadah TS, Jumaymi AK, Shariff M, Shaiban AS, Alaajam WH, Al Makramani BMA, Depsh MAN, Almalki FY, Koreri NA. Unlocking endocrown restoration expertise among dentists: insights from a multi-center cross-sectional study. Med Sci Monit. 2023;29:e940573. 10.12659/MSM.940573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhafar W, Sabbagh HJ, Albassam A, Turkistani J, Zaatari R, Almalik M, Dafar A, Alhamed S, Bahkali A, Bamashmous N. Outcomes of root canal treatment of first permanent molars among children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a retrospective cohort study. Heliyon. 2022;8(10):e11104. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albassam AA. Assessing knowledge, perception, and management toward traumatic tooth avulsion among dentists in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e46337. 10.7759/cureus.46337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khokhar SA, Waheed A, Asif S, Sarwar N, Fatima N, Knowledge. Attitude and practice towards emergency management of avulsed tooth among dental practitioner in pakistan: A Questionnaire-Based survey. J Health Rehab Resa. 2024;4(1):1137–42. 10.61919/jhrr.v4i1.547. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Liu C, Yu J. Chinese dental students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding traumatic dental injuries in immature permanent teeth. BMC Med Educ. 2025;25(1):1003. 10.1186/s12909-025-07584-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenoy P, Rao A, Sargod S, Suvarna R, Shabbir A, Mahaveeran SS, Manu P, Deepanjan M. Evaluation of knowledge, awareness, and attitude towards management of displaced tooth from socket (Avulsion) amongst nursing fraternity in Mangaluru city: A Cross-Sectional study. J Heal Allied Scien NU. 2024;14(S 01):S120–2. 10.1055/s-0044-1786693. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee ZJ, Ng SL, Soo E, Abdullah D, Yazid F, Abdul Rahman M, Teh LA. Modified hank’s balanced salt solution as a storage medium for avulsed teeth: in vitro assessment of periodontal fibroblast viability. Dent Traumatol. 2025;41(2):194–202. 10.1111/edt.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Z, Huang D, Huang S, Chen Z, Yu Q, Hou B, Qiu L, Chen W, Li J, Wang X, Huang Z, Yu J, Zhao J, Pan Y, Pan S, Yang D, Niu W, Zhang Q, Deng S, Ma J, Meng X, Yang J, Wu J, Zhang L, Zhang J, Xie X, Chu J, Que K, Ge X, Huang X, Ma Z, Yue L, Zhou X, Ling J. Expert consensus on intentional tooth replantation. Int J Oral Sci. 2025;17(1):16. 10.1038/s41368-024-00337-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veras SRA, Bem JSP, de Almeida ECB, Lins CCDSA. Dental splints: types and time of immobilization post tooth avulsion. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(3 Suppl 1):S69–75. 10.17096/jiufd.93579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahler B, Hu JY, Marriot-Smith CS, Heithersay GS. Splinting of teeth following trauma: a review and a new splinting recommendation. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(Suppl 1):59–73. 10.1111/adj.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen Yavuz B, Sadikoglu S, Sezer B, Toumba J, Kargul B. An assessment of the knowledge of dentists on the emergency management of avulsed teeth. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2020;54(2):136–46. 10.15644/asc54/2/3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamarao S, Jain J, Ajagannanavar SL, Haridas R, Tikare S, Kalappa AA. Knowledge and attitude regarding management of tooth avulsion injuries among school teachers in rural India. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014;4(Suppl 1):S44–8. 10.4103/2231-0762.144599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aboubakr RM, Wahdan MA, Elkwatehy. Knowledge and attitude of dental interns about management of tooth avulsion: A comparative Cross - Sectional study. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2020;7(11):891–6. 10.19070/2377-8075-20000177. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zafar K, Ghafoor R, Khan FR, Hameed MH. Awareness of dentists regarding immediate management of dental avulsion: Knowledge, attitude, and practice study. Pakistan Medical Association. 2018;68(4):595–9 PMID: 29808050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with the study have not been deposited into a publicly available repository. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.