Abstract

We investigated the effects of temperature, water activity (aw), and syrup film composition on the CFU growth of Wallemia sebi in crystalline sugar. At a high aw (0.82) at both high (20°C) and low (10°C) temperatures, the CFU growth of W. sebi in both white and extrawhite sugar could be described using a modified Gompertz model. At a low aw (0.76), however, the modified Gompertz model could not be fitted to the CFU data obtained with the two sugars due to long CFU growth lags and low maximum specific CFU growth rates of W. sebi at 20°C and due to the fact that growth did not occur at 10°C. At an aw of 0.82, regardless of the temperature, the carrying capacity (i.e., the cell concentration at t = ∞) of extrawhite sugar was lower than that of white sugar. Together with the fact that the syrup film of extrawhite sugar contained less amino-nitrogen relative to other macronutrients than the syrup film of white sugar, these results suggest that CFU growth of W. sebi in extrawhite sugar may be nitrogen limited. We developed a secondary growth model which is able to predict colony growth lags of W. sebi on syrup agar as a function of temperature and aw. The ability of this model to predict CFU growth lags of W. sebi in crystalline sugar was assessed.

Crystalline sugar is covered with a very thin, nutrient-containing syrup film that originates from the mother syrup from which the sugar is crystallized (4, 12). Under the right environmental conditions, this syrup film can result in unwanted growth of xerophilic molds in crystalline sugar during storage (12). If contaminated crystalline sugar is used without prior treatment, it may increase the risk of downstream spoilage of sucrose-rich foods. Studies of the effects of different environmental conditions relevant for sugar storage, including temperature, water activity (aw), and syrup film composition, on the development of xerophilic molds in crystalline sugar are therefore important.

Wallemia sebi is a xerophilic mold that is able to grow at an exceptionally wide range of aw values in many types of solutes, and it exhibits rapid and vigorous sporulation (14). W. sebi is ubiquitous and is found in most foods with low and intermediate moisture contents, including sucrose-rich foods such as marzipan and cakes (14). W. sebi has no known sexual state (14) and therefore produces only conidia (asexual spores). During the life cycle of W. sebi, conidia germinate to form hyphae, and fertile hyphae rapidly produce conidia by complete fragmentation (9, 14).

Secondary growth models describe a change in a certain aspect of microbial growth as a function of environmental conditions (19). Many secondary growth models used for molds describe the maximum radial growth rate as a function of pH, temperature, or aw (3, 5, 6, 13, 17, 18). The radial growth rate, however, focuses on growth after it has occurred. For the food manufacturer it is often more valuable to know when growth of food spoilage microorganisms occurs or (perhaps even more useful) when it does not. For this purpose, secondary growth models may be used to predict growth lags of food spoilage microorganisms under particular environmental conditions (1, 10, 18). To our knowledge, secondary growth models that predict growth lags of W. sebi in model systems for the syrup film covering crystalline sugar have not been developed previously, nor have such models been validated with real food (i.e., crystalline sugar).

In this study, we investigated the effects of temperature, aw, and syrup film composition on the growth of W. sebi in crystalline sugar. Furthermore, we developed a secondary growth model that is able to predict growth lags of W. sebi in a syrup agar model system as a function of temperature and aw. Finally, we assessed whether this model can be used to predict growth lags of W. sebi in crystalline sugar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintenance of W. sebi and preparation of conidia.

One strain of W. sebi was isolated from crystalline sugar, identified by the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Delft, The Netherlands), and maintained on agar slants of modified DG18 (DG18S), which contained (per kilogram) 20 g of DG18 base (CM729; Oxoid), 142 g of glycerol, 161 g of sucrose (commercial grade white sugar), and 32 g of glucose (pH 5.8; aw, 0.91). Conidia of W. sebi were prepared by incubating DG18S plates that had been inoculated with W. sebi for 1 week at 25°C.

Inoculation of crystalline sugar.

White and extrawhite commercial sugar (European Union sugar standards) was heat treated for 6 h at 70°C in roasting bags (polyethylene terephthalate) to eliminate xerophilic fungi. To verify that the sugars were sterile, 20% (wt/wt) solutions of the heat-treated sugars were made, the solutions were membrane filtered (pore size, 0.45 μm), and the membrane filters were incubated for 7 days at 25°C on the surface of DG18S.

To inoculate the sugar, we used a sterile 25% (wt/wt) sugar solution containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80, which was prepared as follows. Extrawhite sugar was rinsed in 50 ml of a 96% (wt/wt) ethanol solution to remove the syrup film. After excess ethanol was removed by vacuum filtration (5 min) and the remaining ethanol was allowed to evaporate for 24 h, the rinsed sugar was dissolved in Milli-Q water at a concentration of 25% (wt/wt), and then the sugar solution was membrane filtered (pore size, 0.45 μm). Finally, Tween 80 was added to a concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol) to facilitate suspension of conidia.

Before inoculation, the 25% (wt/wt) sugar solution was dispensed onto the surface of a DG18S plate containing W. sebi, and the plate was gently shaken to release the conidia. The conidial suspension was transferred to sterile centrifuge tubes and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g. The resulting pellet was washed in the sterile sucrose solution and then centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g. This washing step was repeated twice. The sugar was subsequently inoculated with 40 CFU g−1. To introduce only a minimum amount of moisture into the sugar preparation, 2 ml of a conidial suspension was used to inoculate 1 kg of sugar. To ensure homogeneous distribution of the conidia in the sugar, the inoculated sugar was vigorously mixed for 1 min with a sterilized paddle mixer (Forberg, Forberg, Norway). Preliminary results obtained with one batch that was mixed showed that the standard deviation based on the CFU data for six different samples, each containing 10 g of inoculated sugar, relative to the sample mean was 7% when this method was used (data not shown).

Growth in crystalline sugar.

Four-gram portions of the inoculated white sugar and extrawhite sugar were transferred to 5-ml plastic sample vials. The sample vials were placed in 1,500-ml airtight plastic containers with saturated solutions of either NaCl (aw, 0.76) or sucrose (aw, 0.82) and incubated at 10 or 20°C for up to 153 days. Each container was equipped with wire netting to separate the sugar sample from the saturated solution.

Determination of CFU growth in crystalline sugar.

At regular intervals in each growth experiment, at least two sample vials were removed and treated as follows. The sugar was dissolved in 7.8 ml of sterile water to produce a 10-ml solution and mixed by whirling. Appropriate dilutions of this solution in 20% (wt/wt) glycerol were prepared, 0.1-ml portions of the dilutions were plated on DG18S, and plate counts were determined after 1 week of incubation at 25°C. For some time points, growth occurred in only one sample vial, probably due to heterogeneous distribution of the conidia in the sugar during inoculation.

Model of primary growth in crystalline sugar.

The CFU growth of W. sebi in crystalline sugar was modeled by fitting a modified Gompertz model (20) to the CFU data:

|

(1) |

where t is the time (in days), N is the cell concentration at time t (in CFU per gram), N0 is the inoculation level (i.e., the cell concentration at time zero) (in CFU per gram), A is ln(N∞/N0) (where N∞ is the carrying capacity of the sugar [i.e., the cell concentration at t = ∞] [in CFU per gram]), μs is the maximum specific CFU growth rate according to the modified Gompertz model (in days−1), and λs is the CFU growth lag (in days).

Preparation of syrup agars and petri slides.

Runoff syrup was used as a model system for the syrup film covering the surface of crystalline sugar, since runoff syrup is the mother syrup from which sugar is crystallized (8). When sugar crystals become moist, the syrup film is diluted and mixes with the dissolving crystal surface. Thus, to mimic the surface of moist sugar crystals, syrup agars were prepared by mixing a saturated sucrose solution (white sugar) and runoff syrup (Danisco Sugar) to produce solutions with aw values ranging from 0.68 (pure runoff syrup; pH 9.6) to 0.85 (pure sugar solution; pH 6.6). Agar (1.5%,wt/wt) was added to these solutions, and the mixtures were heated by steaming them (100°C) for 30 min to dissolve the agar and to eliminate xerophilic fungi.

A syrup agar solution was dispensed into petri slides (PD1504700; Millipore) and distributed by gentle swirling. The cool, but not solidified, syrup agar in each petri slide was inoculated at three points with W. sebi conidia. The petri slides were sealed and incubated at temperatures between 3 and 27°C for up to 160 days. The aw values of sterile petri slide controls were measured at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. These control measurements verified that the aw values of the sealed petri slides were constant throughout the experiments (data not shown).

Determination of colony growth lag in syrup agar.

Petri slides were examined for colony growth by using a stereomicroscope (magnification, ×11; SZH-ILLD; Olympus) at regular intervals ranging from once a day for the petri slides with the highest aw values to once a week for the petri slides with the lowest aw values. The number of days from inoculation of a petri slide with conidia until colony growth (i.e., germination) at all three inoculation points was observed (D+) was recorded. Furthermore, the number of days until the observation preceding D+, when colony growth had not yet occurred (D−), was also recorded. Since colony growth occurred somewhere between D− and D+, both D− and D+ were used as observed colony growth lag data to develop the secondary growth model described below.

Model of secondary growth in syrup agar.

The following secondary growth model describing the colony growth lag of W. sebi as a function of temperature and aw was developed on the basis of a variance stabilizing transformation of the observed colony growth lag data:

|

(2) |

where Y is the transformed colony growth lag {Y = ln(colony growth lag [in days] + 1)}, T is the temperature (in degrees Celsius), and a, b, c, and d are parameters that were estimated by fitting.

The predicted colony growth lag of W. sebi for a specific temperature and aw was calculated using equation 2. The predicted temperature and aw resulting in a 100-day colony growth lag of W. sebi in syrup agar were calculated by using 100 days as the colony growth lag in equation 2 and solving for aw as a function of T.

Fitting procedures and model performance checking.

All fittings were done with IgorPro software, version 4.01A (WaveMetrics Inc.), using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm to minimize the squares of residuals (15). Quality of fit was judged based on the distribution of residuals (normally distributed with zero mean), and the 95% confidence interval for each parameter in the primary (equation 1) and secondary (equation 2) growth models was calculated by IgorPro based on the residuals. The performance of the secondary growth model (equation 2) was evaluated by calculating the percent bias and the percent discrepancy for the observed Y response (2).

Analyses of syrup films and runoff syrup.

The syrup films of 500 g of crystalline white sugar and 500 g of crystalline extrawhite sugar were extracted for 10 min in a tumbler mixer by using 500-g portions of 95% (wt/wt) ethanol. Each sugar-ethanol slurry was filtered with a 1.2-μm-pore-size glass fiber filter (GSC; Whatman) with a 15-μm-pore-size paper filter support (AGF 165-185; Whatman) and then cleared by filtering with a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter (11306-47-N; Sartorius). The cleared filtrate was evaporated to dryness at 50°C in a rotary evaporator, which resulted in approximately 2 g of residue that was subsequently diluted to obtain 50 g of concentrate with distilled water. The glucose, fructose, glycerol, and lactic acid contents in the concentrate were analyzed by enzymatic assays (kits 139-106, 139-106, 148-167, and 1-112-821, respectively; Boehringer Mannheim). The amino-nitrogen (amino-N) content of the concentrate was determined as described by Moore and Stein (11). The potassium content was analyzed with an air-ethylene flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer).

Runoff syrup was analyzed by diluting 2 g of syrup to 50 g with Milli-Q water and carrying out an analysis as described above.

All results were expressed in milligrams per kilogram of crystalline sugar. When sugar samples spiked with known amounts of the components mentioned above were used, preliminary experiments showed that the levels of recovery were more than 90% for all of the components analyzed by the methods used (data not shown). Furthermore, the repeatability values for the methods (expressed as ±2 standard deviations) were as follows: glucose, ±0.8 mg kg−1; fructose, ±4 mg kg−1; glycerol, ±0.6 mg kg−1; lactic acid, ±4 mg kg−1; amino-N, ±1.4 mg kg−1; and potassium, ±26 mg kg−1.

Miscellaneous analytical procedures.

The aw values of solutions and agar preparations at the different temperatures were determined with an Aqualab CX-2 (Decagon Devices) connected to a thermostat-controlled water bath.

RESULTS

CFU growth of W. sebi in crystalline sugar.

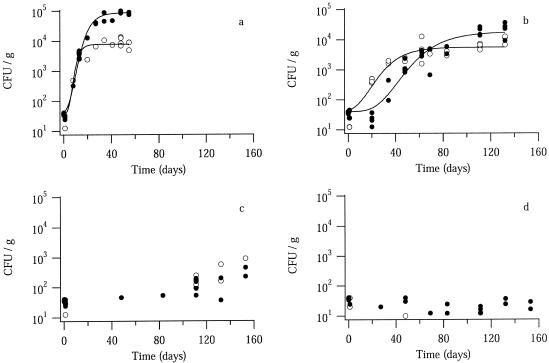

Figure 1 shows the CFU growth of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar at different temperatures and aw values. At an aw of 0.82, CFU growth was observed at both 10 and 20°C (Fig. 1a and b), whereas at an aw of 0.76, CFU growth during the experiment (153 days) was observed only at 20°C (Fig. 1c and d). Microscopic examination of both sugars during the growth experiments revealed no W. sebi mycelia, only W. sebi conidia (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Growth of W. sebi in white sugar (•) and extrawhite sugar (○) at an aw of 0.82 (a and b) or 0.76 (c and d) and at 20°C (a and c) or 10°C (b and d). The solid lines are fitted modified Gompertz models. Each data point represents the results obtained with one sample vial (see Materials and Methods).

At an aw of 0.82, regardless of the sugar type, the modified Gompertz model (equation 1) fit the CFU growth curves of W. sebi at both 10 and 20°C (Fig. 1a and b). At an aw of 0.76, regardless of the sugar type, the stationary phase of CFU growth was not reached at 20°C due to long CFU growth lags and low maximum specific CFU growth rates (Fig. 1c), and growth did not occur at all at 10°C (Fig. 1d). Thus, the modified Gompertz model could not be fitted to the CFU data for W. sebi at an aw of 0.76.

The CFU growth lag of W. sebi in white sugar according to the modified Gompertz model fit was significantly (P < 0.05) shorter at 20°C than at 10°C (Table 1), whereas in extrawhite sugar the values were the same at 10 and 20°C (Table 1). Furthermore, the CFU growth lags of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar were identical (P < 0.05) at 20°C, but the CFU growth lag was significantly (P < 0.05) shorter in extrawhite sugar than in white sugar at 10°C (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Estimated parameters of the modified Gompertz model for CFU growth of W. sebi at an aw of 0.82 in crystalline sugara

| Sugar | Temp (°C) | λs (days) | μs (days−1) | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 20 | 3 ± 2 | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 7.7 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 23 ± 9 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | |

| Extrawhite | 20 | 4 ± 4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 5 ± 8 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

Estimated values ± 95% confidence intervals. λs, CFU growth lag; μs, maximum specific CFU growth rate; A = ln(N∞/N0), where N0 is the inoculation level (40 CFU g−1) and N∞ is the carrying capacity of the sugar (in CFU per gram).

In both white sugar and extrawhite sugar, the maximum specific CFU growth rates of W. sebi according to the modified Gompertz model fit were significantly (P < 0.05) higher at 20°C than at 10°C (Table 1). At both 10 and 20°C, the maximum specific CFU growth rates of W. sebi were not significantly (P < 0.05) influenced by the type of sugar used (Table 1).

The carrying capacity of the sugar was estimated by using the parameter A [ln(N∞/N0)] in the modified Gompertz model (Table 1). The inoculation level was approximately 40 CFU g−1 at both 10 and 20°C (Fig. 1a and b). The carrying capacities were 9 × 104 CFU g−1 for white sugar and 8 × 103 CFU g−1 for extrawhite sugar at 20°C, and they were 2 × 104 CFU g−1 for white sugar and 5 × 103 CFU g−1 for extrawhite sugar at 10°C. These results show that regardless of the sugar type, the carrying capacity was significantly (P < 0.05) lower at 10°C than at 20°C and that regardless of the temperature, the carrying capacity of extrawhite sugar was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than that of white sugar (Table 1).

Colony growth lag of W. sebi in syrup agar model system.

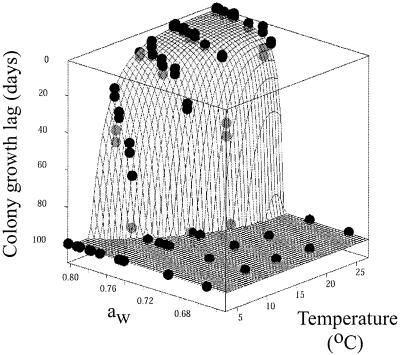

Colony formation by W. sebi conidia on syrup agar was monitored for more than 100 days. The colony growth lag data obtained for W. sebi consisted of two values: the day when growth was observed (D+); and the day of the observation preceding D+, when growth had not yet occurred (D−). Figure 2 shows the observed colony growth lag data (D+ and D−) obtained at various temperatures and aw values in syrup agar. For illustrative purposes, observed colony growth lags greater than 100 days were considered 100 days in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Observed colony growth lags (D+ and D−) of W. sebi in syrup agar as a function of temperature and aw. The lower and upper points for each data pair represent the D+ and D− values, respectively. The fit surface of the secondary growth model describing the predicted colony growth lags (equation 2) is represented by a slightly opaque grid; the data points in front of the grid are indicated by black circles, and the data points behind the grid are indicated by gray circles. For illustrative purposes, observed and predicted colony growth lags greater than 100 days are expressed as 100 days.

The observed colony growth lags described a flat plateau of high temperatures and high aw values, where colony growth occurred within 10 days (Fig. 2). Within the ranges of these temperatures and aw values, changes in temperature and aw had little effect on the colony growth lag of W. sebi (Fig. 2). The plateau was surrounded by an edge of temperature and aw values that resulted in rapidly increasing colony growth lags (Fig. 2), indicating that at these temperatures and aw values it was increasingly difficult for W. sebi to enter the growth phase.

Figure 2 also shows the fit surface of the secondary growth model describing the predicted colony growth lags as a function of temperature and aw (equation 2). The values (±95% confidence intervals) of the model parameters were as follows: a, 0.10 ± 0.03; b, −5 ± 1; c, 70 ± 14; and d, 73 ± 1. For illustrative purposes, predicted colony growth lags greater than 100 days were considered 100 days in Fig. 2. Our results show that the secondary growth model fit the observed colony growth lag data (Fig. 2).

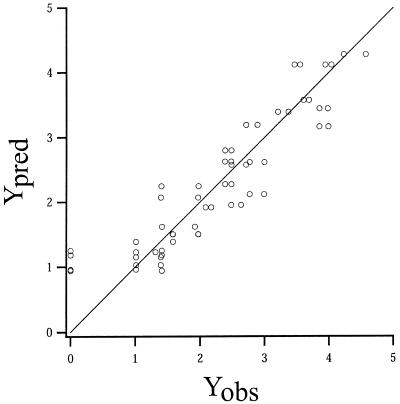

In Fig. 3, the predicted and observed values for the colony growth lag transformation [Y = ln(colony growth lag + 1)] are shown. In addition, the line of equivalence is shown. Except at Yobs = 0, the values were distributed evenly around the line of equivalence (Fig. 3). These results show that the variance of the observed colony growth lag data was stabilized by the Y transformation. Furthermore, they support the conclusion that the secondary growth model fit the observed colony growth lag data.

FIG. 3.

Plot of predicted (Ypred) versus observed (Yobs) values for Y = ln(colony growth lag + 1). Data points are shown together with the line of equivalence.

The percent bias for the observed Y response was −3.1%, indicating that on average the secondary growth model slightly underestimates the colony growth lags (2) (i.e., that it predicts colony growth lags that are shorter than those actually observed). Thus, in the terminology of Ross (16), the model was fail-safe. The percent discrepancy for the observed Y response was 19.2%.

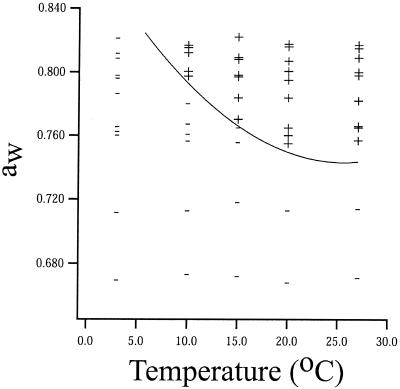

Figure 4 shows the temperatures and aw values of syrup agar at which colony growth of W. sebi was observed to occur and not to occur within 100 days. Colony growth within 100 days was observed only at aw values greater than 0.72 and temperatures greater than 3°C (Fig. 4). Predicted temperature and aw values resulting in a 100-day colony growth lag for W. sebi were calculated using equation 2 and are shown in Fig. 4 as a solid line. The line in Fig. 4 separates a zone in which colony growth of W. sebi is predicted to occur within 100 days (i.e., top right part of Fig. 4) and a zone in which colony growth of W. sebi is predicted not to occur within 100 days (i.e., bottom left part of Fig. 4). The separation predicted by the secondary growth model (equation 2) was in agreement with the observed growth and no-growth data (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Observed growth (+) and no growth (−) of W. sebi in 100 days in syrup agar as a function of temperature and aw. The predicted temperature and aw values resulting in a 100-day colony growth lag obtained by using the secondary growth model for colony growth lag (equation 2) are indicated by the solid line.

Growth lags in crystalline sugar and syrup agar.

The colony growth lags predicted by the secondary growth model were compared to the observed CFU growth lags in white sugar and extrawhite sugar (Table 2). The predicted colony growth lags were calculated using equation 2, and the observed CFU growth lags were derived from Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Observed CFU growth lags of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar and predicted colony growth lag of W. sebi in syrup agar

| Sugar or model | Growth lag (days) at an aw of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.76

|

0.82

|

|||

| 10°C | 20°C | 10°C | 20°C | |

| White sugara | >153 | 83-111 | 20-34 | 1-8 |

| Extrawhite sugara | >153 | 83-111 | 1-20 | 1-8 |

| Secondary growth model | >100 | 25 | 26 | 2 |

The CFU growth lags of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar are represented by the incubation intervals during which growth initiation was observed.

At an aw of 0.82, the predicted colony growth lags were in agreement with the observed CFU growth lags in white sugar at both 10 and 20°C (Table 2). A similar agreement was observed for extrawhite sugar at 20°C (Table 2). At 10°C, however, the predicted colony growth lag was slightly longer than the observed CFU growth lag in extrawhite sugar (Table 2). At an aw of 0.76, the predicted colony growth lag was in agreement with the observed CFU growth lags in both white sugar and extrawhite sugar at 10°C (Table 2). At 20°C, however, the predicted colony growth lag was approximately four times shorter than the observed CFU growth lags in both white sugar and extrawhite sugar (Table 2).

Composition of syrup films and runoff syrup.

White sugar contained approximately five times more lactic acid, six times more amino-N, and four times more potassium in its syrup film than extrawhite sugar (Table 3). White sugar, however, contained eight times less glucose and two times less fructose in its syrup film than extrawhite sugar (Table 3). The glycerol contents of the syrup films of the two types of sugar were about the same (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Compositions of syrup films and runoff syrup

| Sugar or syrup | Amt (mg/kg of crystalline sugar)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Fructose | Glycerol | Lactic acid | Amino-N | Potassium | |

| White sugar | 3 (0.3)b | 11 (1) | 3 (0.3) | 99 (8) | 12 (1) | 160 (13) |

| Extrawhite sugar | 20 (10) | 22 (11) | 2 (1) | 21 (10) | 2 (1) | 38 (19) |

| Runoff syrupc | 31 (1) | 29 (1) | 7 (0.3) | 200 (8) | 26 (1) | 410 (16) |

The values are means based on two determinations.

The value in parentheses is the amount of the components relative to the amount of amino-N.

Amount in 2 g of syrup, which corresponded to the syrup film of 1 kg of sugar.

The absolute nutrient compositions of the runoff syrup and the syrup films of the sugars were very different (Table 3). Therefore, we calculated the relative nutrient compositions by arbitrarily choosing amino-N as the standard in order to compare the runoff syrup with the syrup films. In the syrup film of white sugar, the amounts of glucose, fructose, glycerol, lactic acid, and potassium relative to the amount of amino-N were about the same as they were in runoff syrup (Table 3). In the syrup film of extrawhite sugar, the amounts of lactic acid and potassium relative to the amount of amino-N were about the same as they were in runoff syrup, whereas the amounts of glucose and fructose relative to the amount of amino-N were approximately 10 times larger than they were in runoff syrup and the amount of glycerol relative to the amount of amino-N was three times larger than it was in runoff syrup (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The modified Gompertz model has been used mainly to describe growth of bacteria and yeasts as a function of time in liquid media (19). In this study, we show for the first time that CFU growth of the mold W. sebi in crystalline sugar at an aw of 0.82 can be described using the modified Gompertz model (Fig. 1a and b). The mechanisms underlying the CFU growth behavior of W. sebi in crystalline sugar are not clear yet and require further investigation.

Microscopic examination of crystalline sugar during the growth experiments revealed only conidia of W. sebi (data not shown). These results, indicating that W. sebi sporulates rapidly under the growth conditions used, are consistent with the fact that W. sebi in general exhibits rapid and vigorous sporulation (14). Thus, the CFU growth of W. sebi in this study may essentially have been a measure of the production of conidia. This means that, in principle, the maximum specific CFU growth rate may estimate the rate of formation of conidia. We observed higher maximum specific CFU growth rates of W. sebi in both white sugar and extrawhite sugar at a high temperature (Table 1). These results indicate that a decrease in temperature decreases the rate of formation of conidia in W. sebi.

The carrying capacities of both types of sugar are lower at the low temperature than at the high temperature (Table 1). Similar unexplained effects have been observed with other fungi (7). In addition, extrawhite sugar has a lower carrying capacity than white sugar (Table 1). Together with the fact that the syrup film of extrawhite sugar contains less amino-N relative to the amounts of other macronutrients than the syrup film of white sugar contains (Table 3), these results indicate that the CFU growth of W. sebi in extrawhite sugar may be nitrogen limited.

Since the CFU growth of W. sebi in this study may have been a measure of production of conidia, in principle, the CFU growth lag may provide an estimate of the time comprising initial germination and hyphal growth until sporulation. Thus, our results which showed that the CFU growth lag of W. sebi was shorter in extrawhite sugar than in white sugar at a low temperature (Table 1) suggest that at a low temperature the period of time in which initial germination and hyphal growth of W. sebi occur before sporulation is shorter in extrawhite sugar than in white sugar. These results agree with the fact that production of conidia in molds is induced during depletion of nutrients in the growth medium (7) and with the fact that the syrup film of extrawhite sugar contains less growth-supporting nutrients than the syrup film of white sugar contains (Table 3). The reason why the syrup film composition has no effect on the CFU growth lags of W. sebi at a high temperature remains to be elucidated.

We developed an empirical secondary growth model to describe the colony growth lag of W. sebi as a function of temperature and aw in a syrup agar model system. We found that the secondary growth model fits the observed colony growth lags (Fig. 2 and 3) and that it is able to accurately predict the temperature and aw values that separate growth and no growth of W. sebi within 100 days (Fig. 4). The results show that in the temperature and aw ranges used in this study, the model can be used to predict colony growth lags of W. sebi on syrup agar as a function of temperature and aw. To our knowledge, the only other secondary growth model that has been developed to predict growth lags of W. sebi was recently described by Patriarca et al. (13). These authors, however, used a different growth medium (agar with malt and yeast extract) and a different component to adjust the aw (glycerol) than we used. Furthermore, their model describes the growth lags of W. sebi only as a function of aw. Thus, a comparison of our results and the results of Patriarca et al. (13) is not straightforward.

To examine whether the secondary growth model developed from the syrup agar experiments may be used to predict real CFU growth lags of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar, the colony growth lags predicted by the secondary growth model were compared to the observed CFU growth lags in white sugar and extrawhite sugar. The results show that the secondary growth model could predict the CFU growth lags of W. sebi in white sugar and extrawhite sugar for three and two combinations, respectively, of the four combinations of temperature and aw investigated (Table 2). Thus, the predicted data are in better agreement with the observed data for white sugar than with the observed data for extrawhite sugar. This may be due to the fact that the relative nutrient compositions of runoff syrup and the syrup film of white sugar are almost the same, whereas the relative nutrient compositions of runoff syrup and the syrup film of extrawhite sugar are not the same (Table 3).

Even though runoff syrup seems to be a good model system for the syrup film covering white sugar, as evaluated by nutrient composition, the secondary growth model still failed to predict the CFU growth lag of W. sebi in white sugar at an aw of 0.76 and 20°C. In this context, it should be noted that the colony growth lag estimates the time to germination, whereas the CFU growth lag, as mentioned above, may estimate the time that includes initial germination and hyphal growth until sporulation. Although our results indicate that W. sebi sporulated rapidly in the growth experiments performed with crystalline sugar, they do not rule out the possibility that W. sebi may exhibit more hyphal growth under some growth conditions than under others. In the former situation, the secondary growth model predicts shorter growth lags than those that are actually observed in crystalline sugar. These considerations may explain the discrepancy between the predicted and observed growth lag values at an aw of 0.76 and 20°C (Table 2). Why, however, W. sebi may exhibit more hyphal growth under this combination of growth conditions remains to be investigated.

In conclusion, the results of the present work show that CFU growth of W. sebi in crystalline sugar at an aw of 0.82 can be described by using a modified Gompertz model. Furthermore, we developed a secondary growth model which can predict colony growth lags of W. sebi on syrup agar as a function of temperature and aw. This model could predict real CFU growth lags of W. sebi in crystalline sugar for some, but not all, of the combinations of temperature and aw investigated. Our results indicate that the discrepancies between the predicted data for the syrup agar model system and the observed data obtained with crystalline sugar may be due to the choice of the substrate used for the model system and/or the dependence of the life cycle of W. sebi on growth conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hanne Kröyer and Ralph Matthias Schoth for excellent technical assistance with the analysis of sugars and syrups and Christer Bergwall for assistance with development of the method used for mixing the sugar and conidia.

This work was supported by the Danish Academy of Technical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abellana, M., A. J. Ramos, V. Sanchis, and P. V. Nielsen. 2000. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging and water activity on growth of Eurotium amstelodami, E. chevalieri and E. herbariorum on a sponge cake analogue. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:606-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranyi, J., C. Pin, and T. Ross. 1999. Validating and comparing predictive models. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 48:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuppers, H. G. A. M., S. Oomes, and S. Brul. 1997. A model for the combined effects of temperature and salt concentration on growth rate of food spoilage molds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3764-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichhorn, H. 1998. Separation of the crystals from the mother liquor in centrifugals, p. 829-860. In P. W. Van der Poel, H. Schiweck, and T. Schwartz (ed.), Sugar technology: beet and cane sugar manufacture. Bartens, Berlin, Germany.

- 5.Gervais, P., P. Molin, W. Grajek, and M. Bensoussan. 1988. Influence of the water activity of a solid substrate on the growth rate and sporogenesis of filamentous fungi. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 31:457-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson, A. M., J. Baranyi, J. I. Pitt, M. J. Eyles, and T. A. Roberts. 1994. Predicting fungal growth: the effect of water activity on Aspergillus flavus and related species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 23:419-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin, D. H. 1994. Fungal physiology. Wiley-Liss Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 8.Higginbotham, J. D., and J. McCarthy. 1998. Quality and storage of molasses, p. 973-992. In P. W. Van der Poel, H. Schiweck, and T. Schwartz (ed.), Sugar technology: beet and cane sugar manufacture. Bartens, Berlin, Germany.

- 9.Madelin, M. F., and S. Dorabjee. 1974. Conidium ontogeny in Wallemia sebi. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 63:121-130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molina, M., and L. Giannuzzi. 1999. Combined effect of temperature and propionic acid concentration on the growth of Aspergillus parasiticus. Food Res. Int. 32:677-682. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore, S., and W. H. Stein. 1954. A modified ninhydrin reagent for the photometric determination of amino acids and related compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 211:907-913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen, W. L. 1949. The microbiology of sugars, syrups and molasses. Barr-Owen Research Enterprises, Baton Rouge, La.

- 13.Patriarca, A., G. Vaamonde, V. F. Pinto, and R. Comerio. 2001. Influence of water activity and temperature on the growth of Wallemia sebi: application of a predictive model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 68:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitt, J. I., and A. D. Hocking. 1997. Fungi and food spoilage. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, United Kingdom.

- 15.Press, W. H., S. A. Flannery, S. A. Teukolsky, and W. T. Vetterling. 1988. Numerical recipes of C. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 16.Ross, T. 1996. Indices for performance evaluation of predictive models in food microbiology. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 81:501-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosso, L., and T. P. Robinson. 2001. A cardinal model to describe the effect of water activity on the growth of moulds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 63:265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valik, L., J. Baranyi, and F. Gorner. 1999. Predicting fungal growth: the effect of water activity on Penicillium roqueforti. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 47:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting, R. C., and R. L. Buchanan. 1993. A classification of models for predictive microbiology. Food Microbiol. 10:175-177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwietering, M. H., I. Jongenburger, F. M. Rombouts, and K. van't Riet. 1990. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1875-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]