Abstract

Purpose

This narrative review explores available information on the process for prosthesis design and factors influencing prosthesis design decision making, to support prosthesis user’s participation in shared decision making about lower-limb prosthesis design.

Recent Findings

The prosthesis design process involves the fabrication of a first prosthesis and/or adjustments to a prosthesis throughout the life of the prosthesis user. Factors that influence prosthesis design decisions are extensive and may be specific to the individual prosthesis user, to prosthesis design options, the available resources, and/or the environment.

Summary

This review offers foundational information for a prosthesis user’s participation in shared decision making for prosthesis design, including the process of prosthesis design and factors influencing prosthesis design decisions. Future research is needed to further describe the timing of prosthesis design decisions, prosthesis design changes over time, and the role of physical and life changes of a prosthesis user on prosthesis design decisions.

Keywords: Lower-limb amputation, Prosthesis design, Lower-limb prosthesis, Prosthesis design process, Shared decision making

Introduction

Rehabilitation after lower-limb amputation (LLA) is a complex process, involving many physical, psychosocial, and life adjustments for an individual to adapt to permanent impairment and to maximize function and quality of life [1]. Of those who experience a major LLA, many utilize prosthetic services [2–4]. Provision of a prosthesis involves a process between a person with LLA and rehabilitation team members (e.g., physician, prosthetist, physical therapist) to determine prosthesis design and associated care [5–7]. Prosthesis design includes considering socket, suspension, interface, component, and accessory options for a given individual [7]. However, multiple prosthesis design options exist without strong evidence for matching any one option to an individual [7–9]. Additionally, people with new LLA progress through rehabilitation at their own unique pace, adding further challenges to prosthesis design decisions [10, 11].

Shared decision making (SDM) is a process where patients and healthcare providers collaboratively make health decisions [12]. SDM is foundational to patient-centered care [13], and recommended in clinical practice guidelines for prosthetic rehabilitation [14]. One key tenet of SDM includes exchanging the best available unbiased, high-quality evidence between clinician and patient to achieve informed preferences and make a shared decision [15]. SDM provides an opportunity to incorporate a prosthesis user’s informed preferences, concerns, personal circumstances, and context into prosthesis design decisions.

For successful SDM, the provision of high-quality information on prosthesis design and the prosthetic rehabilitation process is essential to rehabilitation for a person with LLA [11, 14, 16–19]. When clinicians share the best available evidence, people with LLA are supported in managing their life after amputation, forming realistic expectations, and participating in rehabilitation decisions [11, 20, 21]. Information exchange also contributes to psychological recovery for people after LLA, and psychological factors (e.g., self-efficacy, knowledge of treatment options) are associated with greater prosthesis use [20, 22]. However, people with LLA have described a lack of understanding of rehabilitation processes and prostheses, and it remains unclear what specific information should be exchanged about prosthesis design [16, 23], indicating a need for focused, high-quality patient education.

Most existing evidence focuses on rehabilitation team member decisions [5, 18], without acknowledging a prosthesis user’s for information about the prosthesis design process. Given the complexity of prosthesis design, information for potential prosthesis users should be accurate, evidence-based, accessible, and appropriately tailored to the individual. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to examine and summarize available information on (1) the process for lower-limb prosthesis design and (2) factors influencing lower-limb prosthesis design decisions to support SDM and new prosthesis user’s information needs on lower-limb prosthesis design.

Methods

This narrative review was guided by the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles [24]. A narrative review is ideal when evidence is limited, such as information on the process for prosthesis design, and allows for the inclusion of a wide breadth of resources, including those based on clinical expertise rather than research (e.g., patient education materials and prosthetics textbooks) [25, 26]. For this review, “prosthesis design” refers to the components that make up a physical prosthesis (e.g., prosthetic socket, suspension, interface, components, and accessories), and “prosthesis design process” refers to the process by which prosthesis design is determined.

A publication date range of 2000–2021 was set to focus on contemporary rehabilitation and prosthetic care information. Electronic databases including Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar were searched using the following keywords: prosthesis, design, prescription, decision, rehabilitation, lower-limb, amputation, process, and clinical practice guidelines. The search was limited to published articles available with full text in English. Reference lists of included articles were searched to identify additional potentially relevant resources, including patient education materials and prosthetics textbooks.

Titles and abstracts or summaries of resulting publications were reviewed for inclusion. Articles with abstracts that described the lower-limb prosthesis design decision making, prosthesis design decisions, or factors contributing to lower-limb prosthesis design were reviewed in full text for consideration. Other resources (e.g., patient education materials, textbook chapters) were reviewed in full. Specifically, publications were included if they made a direct connection between a patient factor (e.g., comorbidity) and the choice of prosthesis design (e.g., suspension mechanism). Articles focused on populations under 18 years of age, experimental surgical techniques (e.g., osseointegration), or upper limb amputation were excluded, given the fundamental differences in prosthesis design and processes. Additionally, articles with abstracts that focused on surgical techniques, product development, or prosthesis products without comment on their application to prosthesis design decisions for a given prosthesis user were excluded from the review.

Results

Prosthesis Design Process

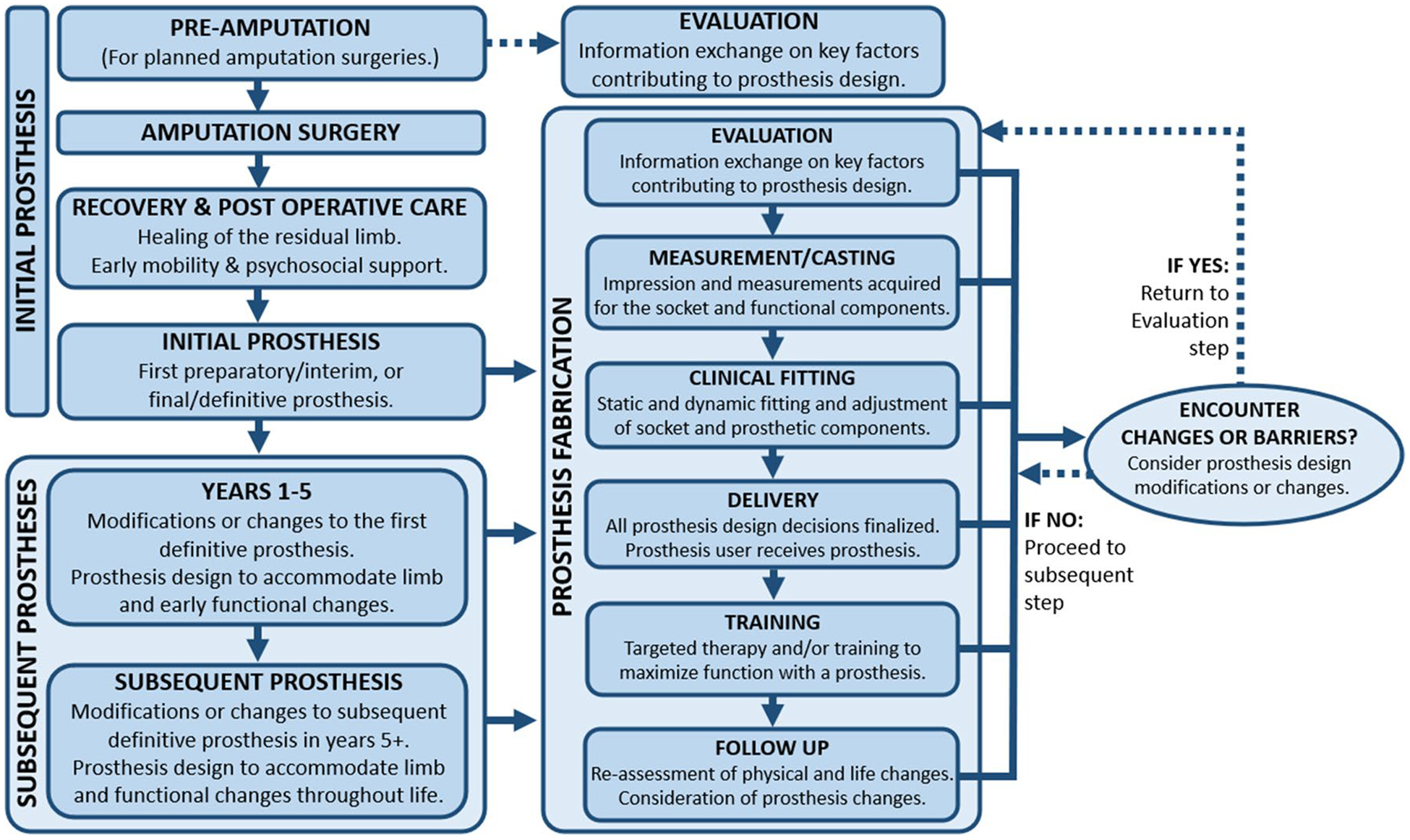

For a new prosthesis user, the process of lower-limb prosthesis design involves considering, choosing, and assembling components together to make a customized prosthesis, based on an individual’s recovery timeline, function, and personal needs (Fig. 1) [18, 14]. New prosthesis users should be informed about the components for a lower-limb prosthesis, including the socket, suspension system, interface, distal components (e.g., prosthetic knees, feet), and accessories (e.g., torsion adaptor, prosthetic cover) (Fig. 2) [7, 18, 27–29]. The prosthesis design process may begin as early as pre-amputation and recurs frequently throughout a prosthesis user’s life [3, 5, 16, 18, 14].

Fig. 1.

Prosthesis design process

Fig. 2.

Prosthesis components

Initial Prosthesis

For a person with new LLA, postoperative care occurs prior to fabricating the first prosthesis and aims to promote residual limb healing and prepare for prosthesis use [27]. Post-operative care may include wound care, pain management, mental and behavioral support, peer visitation, contracture management, and strength, mobility, and safety training [14, 18, 27]. Soft or rigid dressings, shrinkers/elastic bandaging, and/or immediate postoperative prostheses may manage edema and contractures, protect the limb, promote healing, and prepare for prosthesis use [18, 14, 27]. Additionally, assistive devices (e.g., wheelchairs, walkers [27, 29, 30]) are often coordinated with prosthesis design decisions to support mobility and supplement future prosthesis use [27, 29].

If an individual is a candidate for using a prosthesis, design and fabrication of the initial prosthesis begin after LLA surgery, once the residual limb is healed [14, 27]. For planned amputations, prosthesis design options may be introduced prior to surgery [5, 16]. New prosthesis users may receive an “interim” or “preparatory” prosthesis as a first prosthesis and transition to a “definitive” longer-term prosthesis with an alternate design at a later time [18, 27]. A preparatory prosthesis is short-term with limited design options to allow management of early changes in the limb, gait, or a prosthesis user’s needs, or if it is unclear if a prosthesis will be used functionally [27, 31]. However, it is possible to receive a “final” or “definitive” prosthesis as the first prosthesis [27], which may increase potential design options [32]. Once an initial prosthesis is provided, therapy or training with the prosthesis is encouraged for optimizing mobility, function, and success of rehabilitation [27, 33].

Prosthesis Fabrication (Initial and Subsequent Prostheses)

Each initial and subsequent prosthesis is designed and fabricated through a series of clinical visits [14, 34], including evaluation, measurement, trial fittings, delivery, and follow-up care [14, 28, 29] (Fig. 1). For an existing prosthesis user, the evaluation and/or measurement may occur when a new prosthesis or prosthetic component is indicated [33, 35]. During the evaluation and/or casting, a prosthetist works with a prosthesis user to identify factors influencing prosthesis design, and an impression of the residual limb is collected for the fabrication of a socket [5, 18, 28, 36]. The evaluation incorporates a physical assessment and an interview to review a prosthesis user’s current and past lifestyle, goals, and factors contributing to prosthesis design [36]. Collaboration across multiple healthcare team members may inform the process (e.g., information acquired through a surgeon and/or physical therapist may influence prosthesis design options and the care plan) [7].

In subsequent clinical visits, iterative diagnostic socket fittings adjust the fit of the socket over the residual limb [28] and may include assessment and alignment of distal components, via combined feedback of the prosthesis user’s perceived comfort and the prosthetist’s observation of stance and gait [33, 37]. Alignment is the orientation of distal components under the socket and with the prosthesis user’s center of mass and affects a prosthesis user’s comfort, function, and appearance [37–39]. Changes to the final prosthesis design may occur throughout fabrication, prior to delivery [33]. Once the prosthesis’ fit is satisfactory, the final prosthesis is delivered, and therapy or training to use the initial prosthesis may begin [28, 33]. After delivery, follow-up is necessary to monitor and adjust the fit, function, and wear of prosthesis as a prosthesis user’s needs, anatomy, and function change over time [36].

Subsequent Prostheses (First 1–5 Years After First Prosthesis Delivery)

The prosthesis design process for subsequent prostheses includes adjustments to all or parts of the initial prosthesis design to meet a prosthesis user’s evolving needs and goals [40]. Regular follow-up care is necessary for addressing potential changes, repairs, or modifications [3, 5]. For each prosthesis or adjustment, some or all clinical visits may be repeated (Fig. 1). For example, socket replacements may require all clinical visits for fabrication, while repairs may only require an evaluation, fitting, and/or delivery [14]. In the first 1–5 years, changes in prosthesis design may address a prosthesis user’s anticipated physical and personal changes [18, 34, 40], such as volume loss, atrophy, and shape changes.

In the first 1–5 years, prosthesis design changes may address barriers in rehabilitation progress secondary to expected functional changes that accompany increased prosthesis use experience [33, 35]. Alternate prosthesis design (replacement, adjustment, change, or transition from preparatory to definitive prosthesis) may help a prosthesis user overcome physical and functional barriers or support new functional gains [18, 32, 35]. During the first 1–5 years, prosthesis users experience an average of two prosthesis design changes and over four prosthetist visits per year [35, 41].

Subsequent Prostheses (> 5 Years After Initial Prosthesis Delivery)

Over time, prosthesis design changes may accommodate long-term physical changes or meet new needs or goals of experienced prosthesis users (> 5 years) [33, 35, 37, 42]. Physical changes may include changes in strength and functional capacity, pain, health status, comorbidities (e.g., developing new health conditions, diabetes, renal failure, or chronic back pain), body weight, and/or nutrition [18, 43]. There may be a need to account for age-related changes in the prosthesis design, such as changes in strength, muscle coordination, balance, fall risk, vision, and hearing of a prosthesis user [18, 33]. Finally, prosthesis design must accommodate long-term residual limb changes (e.g., revision surgeries, development of neuromas, complications with skin or pain) [27].

Experienced prosthesis users may anticipate changes in prosthesis design associated with a change in goals, activity level, comfort, or function in the prosthesis or difficulties encountered with certain activities [44]. Additionally, prosthesis components will wear with prolonged use of a prosthesis, thus requiring repair, replacement, and/or prosthesis design changes [43]. A prosthesis user’s psychosocial changes may influence prosthesis design changes, including variations in family, social support, and caregiving (e.g., pregnancy, becoming or acquiring a caretaker), changes in lifestyle (e.g., employment), and changes in mood and motivation (e.g., depression) [18, 27]. Finally, peer mentorship may affect the prosthesis design process through introduction to alternative options or assistance with adjusting to life with a prosthesis [16, 45].

Factors Influencing Prosthesis Design

Several factors influence prosthesis design decisions and may be associated with the prosthesis user (physical characteristics, needs, goals, and preferences), available resources and environment, or specific prosthesis components (Table 1). Prosthesis users may place different levels of importance on different factors [15], thus requiring the collaborative expertise of prosthetists and prosthesis users in prosthesis design decisions.

Table 1.

Prosthesis design components, examples of options, and factors influencing decision making

| Prosthesis design component | Example options | Factors influencing decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Socket | Transfemoral: quadrilateral; ischial containment; brimless/subischial Transtibial: patellar tendon-bearing; total surface bearing General: flexible inner socket; adjustable |

Residual limb: skin; condition; shape; length; volume fluctuations; pressure tolerance over different areas; activity level/MFCL*; energy expenditure; gait; balance; comfort; prosthesis user’s preference; prosthetist training & skills; access to prosthetic resources |

| Interface | Molded foam inserts; urethane liner; silicone liner; thermoplastic gel liners; socks & sheaths | Residual limb: skin; shape; length; sensation; stability of volume; heat tolerance/perspiration; pressure tolerance; activity level/MFCL*; cognition; ease of donning/doffing; hand dexterity; vision; allergies; hygiene; comfort; durability; adjustability; cushion/pressure distribution; other components of a prosthesis; cost; frequency of replacement |

| Suspension | Anatomical; strap or belt; sleeve; lanyard; pin; suction; passive or active vacuum | Residual limb: skin condition; shape; length; stability of volume; vascular supply; activity level/MFCL*; proprioception; balance; functional stability; ease of donning/doffing; hand dexterity; safety; proximal joint flexibility and range of motion allowed with the suspension system; comfort; prosthesis user’s preference; effectiveness of suspension; pistoning; durability; pressure distribution; environment; cost; access to prosthetic care |

| Knee | Manual locking; single axis; polycentric; pneumatic or hydraulic controlled; microprocessor knees | Body weight; strength; activity level/MFCL*; stability; amount of use; fall risk; ability to operate the knee; preference; cosmetic appearance; balance confidence; fear; sound; durability; walking speed; energy efficiency; gait & body symmetry; performance on various surfaces; safety features; physical features (e.g., weight, alignment with contralateral knee center); cost; prosthetist training; prosthesis user’s training; access to resources (e.g., electricity, prosthetic care) |

| Foot | Solid ankle cushioned heel (SACH); single-axis; multi-axis; energy storing and dynamic response; hydraulic; powered or microprocessor controlled; activity-specific feet; adjustable heel height | Body weight; activity level/MFCL*; sports involvement; balance; pain; gait deviation; anticipated surfaces for ambulation; prosthesis user’s preference; previous experience; prosthetic foot weight; appearance; shoes and footwear; comfort; balance confidence; fear; pressures on residual limb; need for energy storing properties; durability; energy cost; preferred walking speed; symmetry; effect on proximal joints; cost; prosthetist experience; environment |

| Accessories | Torque absorber; shock absorbing pylon; positional rotator (transfemoral level); prosthesis cover | Activity specific; body image; prosthesis user’s preference |

MFCL: Medicare Functional Classification Level

Prosthesis User’s Physical Characteristics

Prosthesis design matching an individual prosthesis user’s physical characteristics with prosthesis design options [46]. A prosthesis user’s physical characteristics include demographics (age [27, 33, 47–49], sex [49], weight, or body mass index [49, 50]) and residual limb characteristics, such as cause/level of amputation [48, 49], surgery type [27], limb length/shape [27, 47, 51], other amputations (bilateral, contralateral, upper extremity) [27], range of motion and/or muscle contractures [27, 47, 48], strength [27], time since amputation [27]; the presence, type, and severity of pain [47, 49]; and physical condition (sensation, skin condition, soft tissue coverage, volume stability) [27, 47, 48]. Systemic physical characteristics include medical and physical conditions (e.g., illnesses, comorbidities, musculoskeletal impairments, systemic health, back pain, renal or vascular disease) [27, 47–49], global strength (core, contralateral limb, and upper extremity) [27], manual dexterity [27, 52], hearing and vision [47], cognition/memory/learning ability [49, 53–55], and physical ability (fitness, activity level, balance, ability to walk different speeds) [27, 47, 49, 51]. Physical mobility is often described using the Medicare Functional Classification Level (MFCL) [56, 57], which indicates medical necessity for certain prosthesis design options [33, 40, 56–59]. Although a prosthesis user’s physical characteristics affect prosthesis design decisions, existing information lacks strong evidence for recommending a specific prosthesis design option for any given individual physical characteristic or change in physical characteristic [9].

Prosthesis User’s Needs, Goals, and Preferences

Prosthesis design includes matching options with a prosthesis user’s needs, goals, and preferences to maximize prosthesis use, function, and satisfaction [27, 46, 60, 61]. A prosthesis user’s needs include lifestyle (social involvement [47], recreation [45, 49, 51], employment [47, 49, 62, 63]), activities of daily living [47], social support [47, 49], independence [47], or safety (e.g., fall risk, managing back pain) [63]. Prosthesis design should accommodate both present and future goals (e.g., employment needs vs. goal of future employment) [27]. Prosthesis design associated with a prosthesis user’s goals is influenced by a prosthesis user’s motivation and/or optimism [47, 49], psychological factors [49], and self-efficacy [49]. Finally, a prosthesis user’s preferences influence prosthesis design [33, 35], including simplicity of use [51], comfort, [47, 64, 65], quality of life [47], and durability [80], or preferences for prosthetic components [66], color, and weight [65].

Resources and Environment

A prosthesis user’s resources and environment affect prosthesis design decisions. For example, cost and insurance may limit available prosthesis design options [3, 7, 18, 29, 33, 45, 67]. Examples of funding options include public (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Health Administration) or private insurance, and/or self-pay [29, 67]. Additionally, prosthetic care resources influence the availability and access to options (e.g., prosthetist training/experience [45, 51, 63, 68], clinic resources [61, 63, 68], required maintenance and cost [33, 63, 68, 69], and access to therapy/postoperative services [48, 49]). Finally, the prosthesis user’s physical environment will influence prosthesis design decisions (e.g., weather, humidity, temperature) [27, 63].

Factors Specific to Prosthetic Components

Prosthesis factors may influence a prosthesis user’s outcomes in ways that matter to prosthesis users. For example, weight/mass distribution of a prosthesis may affect metabolic efficiency [70], thus influencing skin integrity, muscle atrophy, back pain, user comfort, and systemic and limb health (e.g., weight gain, skin issues) [42, 71]. For both custom and modular components, the raw materials (laminates, thermoplastics, titanium, aluminum, fiberglass, carbon fiber) may affect the overall function, weight, and durability of the prosthesis [18, 33, 72, 73].

Prosthetic Socket

Prosthetic sockets affect a prosthesis user’s satisfaction, comfort, prosthesis use, mobility, and function [7, 16, 29, 34, 74, 75]. Socket designs vary in shape, ability to accommodate volume changes, and pressure distribution [27]. Prosthetic socket design decisions are influenced by a prosthesis user’s limb characteristics, preferences, socket features, and resources [75]. Limb characteristics include limb condition [27, 34], shape [27, 34, 51], length [27], volume and volume fluctuation [27, 34, 51, 76], and pressure tolerance [34, 51, 64, 77]. A prosthesis user’s preferences include comfort [64], perceived balance [77], and preferences in sitting, standing, and dynamic activities [78]. Some evidence suggests that socket design (e.g., ischial containment versus quadrilateral sockets) influences energy expenditure, gait, and balance [37, 75]. Resources affecting socket design decisions include access to prosthetic services and prosthetist training/skill [68, 79].

Interface

Prosthesis interface options (e.g., foam inserts, elastomeric liners, socks, sheathes) affect the prosthesis user’s comfort, residual limb health and skin integrity, and prosthesis use [80]. Interface selection is influenced by a prosthesis user’s characteristics and preferences, interface features, resources, and environment. A prosthesis user’s characteristics and preferences include cognition [53], effort and hand function necessary for donning/doffing [7, 52, 53, 75, 78, 81–83], sensory issues [71, 78], vision [51], skin condition and allergies [72], limb shape/length [78], volume stability [71, 75], heat tolerance and perspiration [72, 78, 81, 82, 84] hygiene, [72, 85] function and mobility [75], comfort [71, 75], and pressure tolerance [72, 77, 78]. Interface features affecting prosthesis design include durability [7, 72, 81, 82], adjustability [18], and cushion/pressure [7, 51, 81, 82] or shear force distribution [51, 72, 77, 78]. Other prosthesis components may influence interface decisions; total surface bearing socket designs or locking suspension systems may require a specific liner material or a liner compatible with a locking mechanism [27–29, 33]. Finally, resources and environment influencing interface decisions include cost [27, 72], replacement frequency [63], and geographic location (e.g., temperature, humidity) [72].

Prosthetic Suspension

Prosthetic suspension affects a prosthesis user’s function, satisfaction, comfort, and prosthesis use [75, 86]. Suspension systems aim to minimize shear forces, pistoning (vertical prosthesis displacement), and perceived weight of the prosthesis [27, 29, 87]. Suspension options (e.g., straps/belts, sleeves, lanyards, pins, passive suction, active vacuum) may be used alone or in combination to optimize prosthesis suspension and/or socket fit or to accommodate a prosthesis user’s needs [7]. Prosthesis suspension decisions are influenced by a prosthesis user’s characteristics, preferences, suspension function, and resources and environment. A prosthesis user’s characteristics and preferences include activity level [18, 78], weight-bearing tolerance [78], limb shape/length [75], volume stability [75, 86], vascular and skin condition [75, 78], proprioception and balance [86], function (including stability) [71, 75], ease of use (including hand dexterity) [75, 83], safety [86, 88], proximal joint flexibility and range of motion available with the suspension system [18, 20], comfort [75, 83, 86], and appearance [75, 89]. Suspension function factors include the system’s effectiveness in suspending the prosthesis [18, 75, 83], pistoning [75, 83, 86], durability [75], and pressure distribution [71, 75]. Finally, resources and environment include cost, a prosthesis user’s physical environment and access to prosthetic care [45, 61, 63, 68].

Prosthetic Knee

Prosthetic knees are considered for amputations at or above the knee and influence a prosthesis user’s function and prosthesis use [27, 29, 68]. Prosthetic knee options may be categorized according to structural and functional differences (e.g., manual locking, single axis, polycentric, pneumatic-, hydraulic-, powered, or microprocessor-control) [27]. Prosthetic knee decisions are influenced by a prosthesis user’s characteristics and preferences [5, 29, 90, 91], prosthetic knee mechanics, and the resources and environment. A prosthesis user’s characteristics include body weight [18, 29], strength [29], past and current physical activity/function (including MFCL) [18, 51, 56], needed stability [39, 51, 78], amount of prosthesis use [92], fall risk [5, 18, 56], and ability to utilize knee features [39]. A prosthesis user’s preferences include cosmetic appearance [51], balance and fear of falling [56, 93], and sound [94]. Prosthetic knee mechanics include durability [68], biomechanical performance that support various walking speeds, energy efficiency, and gait/body symmetry [14, 56, 71, 72, 90, 91, 93, 95, 96], performance on different surfaces (e.g., inclines, uneven terrain) [56, 90, 93], safety features [18, 14, 56, 90], and physical features (e.g., weight of the knee, required space between the socket and the contralateral knee center) [18, 51]. Finally, resources and environment include cost [18, 29, 68], prosthetist training [68], a prosthesis user’s training and therapy [56], maintenance [63, 68], and resources and environment for use (e.g., electricity, water resistance) [14].

Prosthetic Foot

Over 100 prosthetic feet are commercially available [8, 66] and affect a prosthesis user’s mobility [27], comfort, and musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., degenerative joint disease) [37]. Prosthetic feet may be categorized according to structural and functional differences (e.g., solid ankle cushioned heel (SACH), single-axis, multi-axis, energy storing and dynamic response, hydraulic microprocessor-controlled, passive or powered, and activity-specific feet). Factors influencing foot decisions include a prosthesis user’s characteristics and preferences, prosthetic foot mechanics, and resources and environment [7]. A prosthesis user’s characteristics include body weight [94], balance and stability [27, 46, 51, 71, 78, 97, 98], pain or gait deviations [37, 98], sports [71, 94, 99], activity level [46, 51, 71, 78, 98], and anticipated surface levels (e.g., uneven terrain, slopes) [71, 78, 100]. A prosthesis user’s preferences include previous experience [94], prosthetic foot weight [68], appearance and size [20, 68, 101, 102] (e.g., foot performance in shoes [33], heel height [101, 102]), and/or comfort, balance confidence, and fear of falling [71, 94, 103]. Prosthetic foot mechanics include foot durability [68], design/composition [71] (e.g., energy storing material properties [33, 71, 94, 98, 104], material properties influencing residual limb pressure [60, 98]), the foot’s influence on balance and stability, [94, 97, 105–107] energy cost [71, 103, 108], preferred walking speed [71], gait efficiency and symmetry [71, 103, 109, 110], ability to turn [71], uneven or inclined surface performance [71, 100, 111], proximal joint gait mechanics (anatomical or prosthetic) [78, 100, 103, 104], or foot performance in specific activities/sports [96, 112]. Resources and environment include prosthetist experience [7, 46, 51], prosthetist training [97, 103, 113], cost [33, 68, 103], and environmental exposures (e.g., heat/ultraviolet, moisture) [68].

Prosthetic Accessories

Prosthetic accessories (e.g., torque absorbers, shock absorbing pylons, positional rotators, prosthetic covers) may influence a prosthesis user’s comfort and function with a prosthesis [114, 115], prosthesis satisfaction, and body image [20, 41, 116]. Accessory component decisions are influenced by a prosthesis user’s activities and/or preferences. For example, torque absorbers may improve comfort and reduce pain during activities or sports with rotational movements (e.g., golf) [71, 78, 106, 114, 115]. Prosthetic covers provide prosthetic component protection and modify the appearance of a prosthesis, potentially affecting a prosthesis user’s body image, prosthesis satisfaction, and prosthesis use [20, 41, 116, 117]. Thus, a prosthesis user’s preference and desires may warrant prosthetic covers that match the shape and/or color of the contralateral leg [41, 65].

Discussion

This review examines information on the lower-limb prosthesis design process and factors influencing prosthesis design decisions. The prosthesis design process includes the design and fabrication of an initial prosthesis, with subsequent prostheses designs varying throughout a prosthesis user’s life, to address a prosthesis user’s early and long term prosthesis user’s changes. Multiple factors influence prosthesis design decisions, including an individual prosthesis user’s characteristics, needs, and preferences, prosthetic component features, and the available resources and environment. Prosthesis design options exist in abundance, and factors influencing specific prosthesis component decisions vary by component and must be considered in concert with the total prosthesis design and in relation to the individual prosthesis user.

This review outlines information essential for clinicians and prosthesis users to engage in prosthesis design SDM. SDM involves first acknowledging a given decision [12, 15]. In the prosthesis design process, prosthesis design decisions are numerous and change over time [35], warranting a need for SDM early for the first prosthesis design and continuously throughout a prosthesis user’s life. Ensuring that prosthesis users understand the prosthesis design process early will clarify what the potential prosthesis design decisions are, when decisions may be made, when and whether decisions can be changed or modified, factors influencing decisions, and the potential impact of decisions. This review’s information on the stages, potential changes, and steps for initial and subsequent prosthesis design may support prosthesis users in anticipating prosthesis design decisions, considering options, and participating in prosthesis design decision making [12, 15]. Incorporating information on the prosthesis design process early and throughout a prosthesis user’s life may increase participation in design decisions, potentially optimizing health outcomes [16], coping, and adjusting to life after LLA [20].

To promote SDM around health decisions, support should address uncertainty in decision type and timing [118••]. This review demonstrates a deficit in the information available regarding the timing of decisions throughout the prosthesis design process. For example, since distal components (e.g., knees, feet) are evaluated with a socket in subsequent clinical visits, it may be possible for distal component decisions to be finalized later in the prosthesis fabrication process. Additionally, after the first prosthesis, it remains unclear when and what might influence prosthesis users to consider additional prostheses to meet psychosocial or life participation needs, or which prosthesis components are changed at later stages. Information to describe or validate the timing of prosthesis design decisions is lacking, possibly obfuscating a prosthesis user’s participation in prosthesis design decisions [44]. Thus, most current decisions about prosthesis design are based on a healthcare team’s empirical knowledge, training, and experience, with minimal support for a prosthesis user’s role in decision making [36, 46, 119]. Future research should describe the timing of prosthesis design decisions within the prosthesis design process.

SDM also involves exploring options and their associated evidence, to achieve informed preferences [12, 15]. Although many prosthesis components and the factors influencing prosthesis design may be common knowledge to prosthetic healthcare providers [7, 18, 27], people with LLA express uncertainty around prosthesis design decisions [20, 120, 9, 68, 71]. Additionally, results are ambiguous as to how an individual prosthesis user’s priorities for such factors may change over time. One challenge in prosthesis design decision making is both identifying and communicating potential factors influencing prosthesis design decisions; if a prosthesis user is not aware of a given factor, they may not know to articulate their preferences associated with the factor, potentially missing opportunities to inform prosthesis design decisions. This review may aid clinicians and prosthesis users in identifying and discussing factors that influence prosthesis design, and monitoring factors for changes over time, potentially supporting individuals with identifying and prioritizing personal values around potential prosthesis design options and moving to informed preferences.

There are limitations to this review. Although efforts to review relevant literature were made, the search may have missed articles, and conclusions are subject to bias. Additionally, some prosthesis design approaches were excluded from this review (e.g., osseointegration, pediatric prostheses), therefore limiting the application of results.

Conclusion

This review provides insight about the prosthesis design process and factors influencing prosthesis design decisions. The prosthesis design process includes the initial preparatory and definitive prostheses, and subsequent definitive prostheses that change to accommodate a prosthesis user’s changes over time. Factors that influence decisions related to prosthesis design options include a prosthesis user’s characteristics, needs, preferences, prosthetic component features, and the available resources and environment. Results from this work can support SDM for prosthesis design, by supporting prosthesis users in participating in informed prosthesis design decisions. Expanding the body of knowledge on prosthesis design decision making is required to support SDM in clinical practice and to improve a prosthesis user’s outcomes after LLA.

Disclaimer

Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official OPERF and NIH views.

Funding

This work was partly funded by the Orthotic and Prosthetic Education and Research Foundation. This work also received support from NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA grant no. UL1 TR002535.

Footnotes

Competing Interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This work is part of a greater dissertation project, of which some parts have been previously published: Anderson CB. Developing a Shared Decision-Making Aid for Prosthesis Design. Ph.D., University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus, Ann Arbor, 2022. The authors disclose no other previous presentation of this research, manuscript, or abstract.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P. Factors affecting quality of life in lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2011;35(1):90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster JB, Hakimi KN, Williams RM, Turner AP, Norvell DC, Czerniecki JM. Prosthetic fitting, use, and satisfaction following lower-limb amputation: a prospective study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(10):1493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etter K, Borgia M, Resnik L. Prescription and repair rates of prosthetic limbs in the VA healthcare system: implications for national prosthetic parity. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2015;10(6):493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raichle KA, Hanley MA, Molton I, et al. Prosthesis use in persons with lower- and upper-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(7):961–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster JB, Crunkhorn A, Sall J, Highsmith MJ, Pruziner A, Randolph BJ. Clinical Practice guidelines for the rehabilitation of lower limb amputation: an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(9):820–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyns A, Jacobs S, Negrini S, Patrini M, Rauch A. Kiekens C (2021) Systematic Review of clinical practice guidelines for individuals with amputation: identification of best evidence for rehabilitation to develop the WHO’s package of interventions for rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(6):1191–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (In this systematic review of clinical practice guidelines, the World Health Organization determined that evidence is lacking in important patient-centered topics of interest related to vocation and education, sexual and/or intimate relationships, activities of daily living or leisure activities, and education concerning socket/liner fitting).

- 7.Donaghy AC, Morgan SJ, Kaufman GE, Morgenroth DC. Team approach to prosthetic prescription decision-making. Curr Phys Med Rehab. 2020;8(4):386–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Twillert S, Geertzen J, Hemminga T, Postema K, Lettinga A. Reconsidering evidence-based practice in prosthetic rehabilitation: a shared enterprise. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2013;37(3):203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balk EM, Gazula A, Markozannes G, Kimmel HJ, Saldanha IJ, Resnik LJ, Trikalinos TA. Lower limb prostheses: measurement instruments, comparison of component effects by subgroups, and long-term outcomes [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018. Sep. Report No.: 18-EHC017-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stineman MG, Kwong PL, Xie D, et al. Prognostic differences for functional recovery after major lower limb amputation: effects of the timing and type of inpatient rehabilitation services in the Veterans Health Administration. PM R. 2010;2(4):232–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier RH 3rd, Heckman JT. Principles of contemporary amputation rehabilitation in the United States, 2013. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(1):29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. Brit Med J. 2017;359:j4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Rehabilitation of Lower Limb Amputation. Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klute GK, Kantor C, Darrouzet C, et al. Lower-limb amputee needs assessment using multistakeholder focus-group approach. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(3):293–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher P, Maclachlan M. Adjustment to an artificial limb: a qualitative perspective. J Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uustal H. Prosthetic rehabilitation issues in the diabetic and dysvascular amputee. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2009;20(4):689–703. 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith S, Pursey H, Jones A, Baker H, Springate G, Randell T, Moloney C, Hancock A, Newcombe L, Shaw C, Rose A, Slack H, Norman C. Clinical guidelines for the pre and post-operative physiotherapy management of adults with lower limb amputations. 2nd ed. 2016. http://bacpar.csp.org.uk/. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostler C, Ellis-Hill C, Donovan-Hall M. Expectations of rehabilitation following lower limb amputation: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(14):1169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler SL, Schlesinger M, Krueger A, Ludwig A. Amputee Perspectives of Virtual Patient Education. Qual Rep. 2019;24(6):1309–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaghan B, Condie E, Johnston M. Using the common sense self-regulation model to determine psychological predictors of prosthetic use and activity limitations in lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(3):324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett J. Limb loss: the unspoken psychological aspect. J Vasc Nurs. 2016;34(4):128–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(6):e12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sukhera J Narrative reviews in medical education: key steps for researchers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(4):418–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith DG, Michael JW, Bowker JH. Atlas of Amputations and Limb Deficiencies. In: Surgical, Prosthetic and Rehabilitation Principles. 3rd ed. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veterans Affairs Amputation System of Care. The next step: the rehabilitation journey after lower limb amputation. 2018; https://www.qmo.amedd.army.mil/amp/Handbook.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2021.

- 29.America ACo Center NLLI. In: First Step: A Guide for Adapting to Limb Loss, vol. 8. Amputee Coalition of America; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karmarkar AM, Collins DM, Wichman T, et al. Prosthesis and wheelchair use in veterans with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(5):567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts TL, Pasquina PF, Nelson VS, Flood KM, Bryant PR, Huang ME. Limb deficiency and prosthetic management. 4. Comorbidities associated with limb loss. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(3 Suppl 1):21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Highsmith MJ, Kahle JT, Knight M, Olk-Szost A, Boyd M, Miro RM. Delivery of cosmetic covers to persons with transtibial and transfemoral amputations in an outpatient prosthetic practice. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2016;40(3):343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Major MJ, Fey NP. Considering passive mechanical properties and patient user motor performance in lower limb prosthesis design optimization to enhance rehabilitation outcomes. Phys Ther Rev. 2017;22(3–4):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickinson AS, Steer JW, Woods CJ, Worsley PR. Registering methodology for imaging and analysis of residual-limb shape after transtibial amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(2):207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rommers GM, Vos LD, Klein L, Groothoff JW, Eisma WH. A study of technical changes to lower limb prostheses after initial fitting. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2000;24(1):28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hafner BJ, Sanders JE. Considerations for development of sensing and monitoring tools to facilitate treatment and care of persons with lower-limb loss: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gailey R, Allen K, Castles J, Kucharik J, Roeder M. Review of secondary physical conditions associated with lower-limb amputation and long-term prosthesis use. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(1):15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi T, Orendurff MS, Arabian AK, Rosenbaum-Chou TG, Boone DA. Effect of prosthetic alignment changes on socket reaction moment impulse during walking in transtibial amputees. J Biomech. 2014;47(6):1315–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esquenazi A. Gait analysis in lower-limb amputation and prosthetic rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(1):153–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casale R, Maini M, Bettinardi O, et al. Motor and sensory rehabilitation after lower limb amputation: state of art and perspective of change. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2013;35(1):51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ, Burgess AR. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic devices among persons with trauma-related amputations: a long-term outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(8):563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devan H, Carman AB, Hendrick PA, Ribeiro DC, Hale LA. Perceptions of low back pain in people with lower limb amputation: a focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(10):873–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiedler G, Zhang X. Quantifying accommodation to prosthesis interventions in persons with lower limb loss. Gait Posture. 2016;50:14–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray CD. “Don’t you talk to your prosthetist?” Communicational problems in the prescription of artificial limbs. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(6):513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan SJ, Liljenquist KS, Kajlich A, Gailey RS, Amtmann D, Hafner BJ. Mobility with a lower limb prosthesis: experiences of users with high levels of functional ability. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(13):3236–44. 10.1080/09638288.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Der Linde H, Geertzen JH, Hofstad CJ, Van Limbeek J, Postema K. Prosthetic prescription in the Netherlands: an observational study. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaffalitzky E, Gallagher P, MacLachlan M, Wegener ST. Developing consensus on important factors associated with lower limb prosthetic prescription and use. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2085–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munin MC, Espejo-De Guzman MC, Boninger ML, Fitzgerald SG, Penrod LE, Singh J. Predictive factors for successful early prosthetic ambulation among lower-limb amputees. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38(4):379–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kahle JT, Highsmith MJ, Schaepper H, Johannesson A, Orendurff MS, Kaufman K. Predicting walking ability following lower limb amputation: an updated systematic literature review. Technol Innov. 2016;18(2–3):125–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulkarni J, Hannett DP, Purcell S. Bariatric amputee: a growing problem? Prosthet Orthot Int. 2015;39(3):226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Der Linde H, Geertzen JH, Hofstad CJ, Van Limbeek J, Postema K. Prosthetic prescription in the Netherlands: an interview with clinical experts. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2004;28(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baars EC, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JH. Skin problems of the stump and hand function in lower limb amputees: a historic cohort study. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Traballesi M, Delussu AS, Fusco A, et al. Residual limb wounds or ulcers heal in transtibial amputees using an active suction socket system A randomized controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48(4):613–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee DJ, Costello MC. The effect of cognitive impairment on prosthesis use in older adults who underwent amputation due to vascular-related etiology: a systematic review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(2):144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larner S, van Ross E, Hale C. Do psychological measures predict the ability of lower limb amputees to learn to use a prosthesis? Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(5):493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hafner BJ, Smith DG. Differences in function and safety between Medicare Functional Classification Level-2 and-3 transfemoral amputees and influence of prosthetic knee joint control. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(3):417–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borrenpohl D, Kaluf B, Major MJ. Survey of US Practitioners on the validity of the Medicare Functional Classification Level System and Utility of Clinical Outcome Measures for Aiding K-Level Assignment. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2016;97(7):1053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Major MJ, Johnson WB, Gard SA. Interrater reliability of mechanical tests for functional classification of transtibial prosthesis components distal to the socket. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(4):467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spaan MH, Vrieling AH, van de Berg P, Dijkstra PU, van Keeken HG. Predicting mobility outcome in lower limb amputees with motor ability tests used in early rehabilitation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017;41(2):171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pitkin M. What can normal gait biomechanics teach a designer of lower limb prostheses? Acta Bioeng Biomech. 2013;15(1):3–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P. Adjustments to amputation and an artificial limb in lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2014;38(2):115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schoppen T, Boonstra A, Groothoff JW, van Sonderen E, Goeken LN, Eisma WH. Factors related to successful job reintegration of people with a lower limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(10):1425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waldera KE, Heckathorne CW, Parker M, Fatone S. Assessing the prosthetic needs of farmers and ranchers with amputations. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2013;8(3):204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eshraghi A, Abu Osman NA, Gholizadeh H, Ali S, Saevarsson SK, Abas WAW. An experimental study of the interface pressure profile during level walking of a new suspension system for lower limb amputees. Clin Biomech. 2013;28(1):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luza LP, Ferreira EG, Minsky RC, Pires GKW, da Silva R. Psychosocial and physical adjustments and prosthesis satisfaction in amputees: a systematic review of observational studies. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(5):582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van der Linde H, Hofstad CJ, Geurts AC, Postema K, Geertzen JH, van Limbeek J. A systematic literature review of the effect of different prosthetic components on human functioning with a lower-limb prosthesis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(4):555–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pasquina CP, Carvalho AJ, Sheehan TP. Ethics in rehabilitation: access to prosthetics and quality care following amputation. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(6):535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wyss D, Lindsay S, Cleghorn WL, Andrysek J. Priorities in lower limb prosthetic service delivery based on an international survey of prosthetists in low- and high-income countries. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2015;39(2):102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cutti AG, Lettieri E, Del Maestro M, et al. Stratified cost-utility analysis of C-Leg versus mechanical knees: findings from an Italian sample of transfemoral amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017;41(3):227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Handford ML, Srinivasan M. Energy-optimal human walking with feedback-controlled robotic prostheses: a computational study. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2018;26(9):1773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Price MA, Beckerle P, Sup FC. Design optimization in lower limb prostheses: a review. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2019;27(8):1574–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cochrane H, Orsi K, Reilly P. Lower limb amputation Part 3: prosthetics--a 10 year literature review. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25(1):21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaufman KR, Bernhardt K. Functional performance differences between carbon fiber and fiberglass prosthetic feet. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45(3):205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, Ali S. Transfemoral prosthesis suspension systems: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(9):809–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanders JE, Fatone S. Residual limb volume change: systematic review of measurement and management. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(8):949–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, Arifin N, Chung TY. A comparison of pressure distributions between two types of sockets in a bulbous stump. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2016;40(4):509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Linde H, Hofstad CJ, van Limbeek J, Postema K, Geertzen JH. Use of the Delphi Technique for developing national clinical guidelines for prescription of lower-limb prostheses. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(5):693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giesberts B, Ennion L, Hjelmstrom O, et al. The modular socket system in a rural setting in Indonesia. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(3):336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klute GK, Glaister BC, Berge JS. Prosthetic liners for lower limb amputees: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2010;34(2):146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hachisuka K, Matsushima Y, Ohmine S, Shitama H, Shinkoda K. Moisture permeability of the total surface bearing prosthetic socket with a silicone liner: is it superior to the patella-tendon bearing prosthetic socket? J UOEH. 2001;23(3):225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richardson A, Dillon MP. User experience of transtibial prosthetic liners: a systematic review. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017;41(1):6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Kamyab M, Eshraghi A, Luoviksdottir AG, Abas WABW. Clinical evaluation of two prosthetic suspension systems in a bilateral transtibial amputee. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2012;91(10):894–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klute GK, Bates KJ, Berge JS, Biggs W, King C. Prosthesis management of residual-limb perspiration with subatmospheric vacuum pressure. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(6):721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, Shitama H, Shinkoda K. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(9):1286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Samitier CB, Guirao L, Costea M, Camós JM, Pleguezuelos E. The benefits of using a vacuum-assisted socket system to improve balance and gait in elderly transtibial amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2016;40(1):83–8. 10.1177/0309364614546927. Epub 2014 Sep 26. Erratum in: Prosthet Orthot Int. 2016;40(4):NP2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abu Osman NA, Gholizadeh H, Eshraghi A, Wan Abas WAB. Clinical evaluation of a prosthetic suspension system: looped silicone liner. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017;41(5):476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rosenblatt NJ, Ehrhardt T. The effect of vacuum assisted socket suspension on prospective, community-based falls by users of lower limb prostheses. Gait Posture. 2017;55:100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Caliskan Uckun A, Yurdakul FG, Almaz SE, et al. Reported physical activity and quality of life in people with lower limb amputation using two types of prosthetic suspension systems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019;43(5):519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kahle JT, Highsmith MJ, Hubbard SL. Comparison of nonmicroprocessor knee mechanism versus C-Leg on Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire, stumbles, falls, walking tests, stair descent, and knee preference. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Varrecchia T, Serrao M, Rinaldi M, et al. Common and specific gait patterns in people with varying anatomical levels of lower limb amputation and different prosthetic components. Hum Mov Sci. 2019;66:9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moller S, Hagberg K, Samulesson K, Ramstrand N. Perceived self-efficacy and specific self-reported outcomes in persons with lower-limb amputation using a non-microprocessor-controlled versus a microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knee. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(3):220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Highsmith MJ, Kahle JT, Miro RM, et al. Functional performance differences between the Genium and C-Leg prosthetic knees and intact knees. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(6):753–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poonsiri J, van Putten SWE, Ausma AT, Geertzen JHB, Dijkstra PU, Dekker R. Are consumers satisfied with the use of prosthetic sports feet and the provision process? A Mixed-Methods Study Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:109869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iosa M, Paradisi F, Brunelli S, et al. Assessment of gait stability, harmony, and symmetry in subjects with lower-limb amputation evaluated by trunk accelerations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(4):623–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Safaeepour Z, Eshraghi A, Geil M. The effect of damping in prosthetic ankle and knee joints on the biomechanical outcomes: a literature review. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017;41(4):336–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nederhand MJ, Van Asseldonk EH, van der Kooij H, Rietman HS. Dynamic balance control (DBC) in lower leg amputee subjects; contribution of the regulatory activity of the prosthesis side. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon). 2012;27(1):40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stevens PM, Rheinstein J, Wurdeman SR. Prosthetic foot selection for individuals with lower-limb amputation: a clinical practice guideline. J Prosthet Orthot. 2018;30(4):175–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Poonsiri J, Dekker R, Dijkstra PU, Hijmans JM, Geertzen JHB. Bicycling participation in people with a lower limb amputation: a scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lamers EP, Eveld ME, Zelik KE. Subject-specific responses to an adaptive ankle prosthesis during incline walking. J Biomech. 2019;95: 109273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.•.Major MJ, Hansen AH, Esposito ER. Focusing research efforts on the unique needs of women prosthesis users. J Prosthet Orthot. 2021;Online first. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (In this narrative review, preferences of women with amputation are explored and discussed when considering prosthetic foot design and selection. Results suggest that women prefer different characteristics in prosthetic feet related to versatility in footwear and prosthetic foot features, and that evidence on the effects of footwear, prosthesis design, and mobility in women to guide prosthetic foot selection is lacking).

- 102.Esposito ER, Lipe DH, Rabago CA. Creative prosthetic foot selection enables successful ambulation in stiletto high heels. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(3):344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hofstad C, Linde H, Limbeek J, Postema K. Prescription of prosthetic ankle-foot mechanisms after lower limb amputation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004(1):CD003978. 10.1002/14651858.CD003978.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Underwood HA, Tokuno CD, Eng JJ. A comparison of two prosthetic feet on the multi-joint and multi-plane kinetic gait compensations in individuals with a unilateral trans-tibial amputation. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2004;19(6):609–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koehler-McNicholas SR, Savvas Slater BC, Koester K, Nickel EA, Ferguson JE, Hansen AH. Bimodal ankle-foot prosthesis for enhanced standing stability. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204512. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kamali M, Karimi MT, Eshraghi A, Omar H. Influential factors in stability of lower-limb amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(12):1110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Arifin N, Abu Osman NA, Ali S, Wan Abas WA. The effects of prosthetic foot type and visual alteration on postural steadiness in below-knee amputees. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;13(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Delussu AS, Brunelli S, Paradisi F, et al. Assessment of the effects of carbon fiber and bionic foot during overground and treadmill walking in transtibial amputees. Gait Posture. 2013;38(4):876–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Houdijk H, Wezenberg D, Hak L, Cutti AG. Energy storing and return prosthetic feet improve step length symmetry while preserving margins of stability in persons with transtibial amputation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2018;15(Suppl 1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wurdeman SR, Myers SA, Stergiou N. Amputation effects on the underlying complexity within transtibial amputee ankle motion. Chaos. 2014;24(1):013140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koehler-McNicholas SR, Nickel EA, Medvec J, Barrons K, Mion S, Hansen AH. The influence of a hydraulic prosthetic ankle on residual limb loading during sloped walking. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Poonsiri J, Dekker R, Dijkstra PU, et al. Cycling of people with a lower limb amputation in Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hafner BJ, Sanders JE, Czerniecki JM, Fergason J. Transtibial energy-storage-and-return prosthetic devices: a review of energy concepts and a proposed nomenclature. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39(1):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Segal AD, Orendurff MS, Czerniecki JM, Shofer JB, Klute GK. Local dynamic stability of amputees wearing a torsion adapter compared to a rigid adapter during straight-line and turning gait. J Biomech. 2010;43(14):2798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Segal AD, Kracht R, Klute GK. Does a torsion adapter improve functional mobility, pain, and fatigue in patients with transtibial amputation? Clin Orthop Relat R. 2014;472(10):3085–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(14–15):837–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Senra H, Oliveira RA, Leal I, Vieira C. Beyond the body image: a qualitative study on how adults experience lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(2):180–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa decision support framework part 1: a systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(5):555–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (In this systematic review, additional manifestations of patient decision needs were identified for revision to the Ottawa Decision Support Framework for supporting shared decision making. Of note, decisional needs manifestations included information overload, unrealistic expectations for outcome probabilities, and unpredictable decision timing).

- 119.Dillon MP, Major MJ, Kaluf B, Balasanov Y, Fatone S. Predict the Medicare Functional Classification Level (K-level) using the amputee mobility predictor in people with unilateral transfemoral and transtibial amputation: a pilot study. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(2):191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Anderson CB, Kittelson AJ, Wurdeman SR, et al. Understanding decision-making in prosthetic rehabilitation by prosthetists and people with lower limb amputation: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (In this qualitative study of perspectives of prosthetists and lower limb prosthesis users, results demonstrate that lower limb prosthesis users are uncertain about or unaware of the various prosthesis design decisions that take place to receive a prosthesis and that multiple priorities must be balanced in order to contribute to prosthetic rehabilitation decisions).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.