Abstract

A 24-h direct plating method for fecal coliform enumeration with a resuscitation step (preincubation for 2 h at 37 ± 1°C and transfer to 44 ± 1°C for 22 h) using fecal coliform agar (FCA) was compared with the 24-h standardized violet red bile lactose agar (VRBL) method. FCA and VRBL have equivalent specificities and sensitivities, except for lactose-positive non-fecal coliforms such as Hafnia alvei, which could form typical colonies on FCA and VRBL. Recovery of cold-stressed Escherichia coli in mashed potatoes on FCA was about 1 log unit lower than that with VRBL. When the FCA method was compared with standard VRBL for enumeration of fecal coliforms, based on counting carried out on 170 different food samples, results were not significantly different (P > 0.05). Based on 203 typical identified colonies selected as found on VRBL and FCA, the latter medium appears to allow the enumeration of more true fecal coliforms and has higher performance in certain ways (specificity, sensitivity, and negative and positive predictive values) than VRBL. Most colonies clearly identified on both media were E. coli and H. alvei, a non-fecal coliform. Therefore, the replacement of fecal coliform enumeration by E. coli enumeration to estimate food sanitary quality should be recommended.

To estimate food sanitary quality, the classic approach is based on the search for not only pathogenic microorganisms but also indicator microorganisms such as fecal coliforms, whose presence indicates possible pathogens and fecal food contamination of human and/or animal origin (10, 34, 47). According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), fecal coliforms, renamed thermotolerant coliforms, are “Gram negative bacilli, not sporulated, oxidase negative, optional aerobic or anaerobic, able to multiply in presence of bile salts or other surface agents which have equivalent properties and able to ferment lactose with acid and gas production in 48 h at the temperature of 44 ± 0.5°C” (30, 31). From Leclerc and Mossel's classification of enterobacterial coliforms in hygiene and public health, thermotolerant coliforms include several bacterial species: Citrobacter freundii, Citrobacter diversus, Citrobacter amalonaticus, Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Moellerella wisconsensis, Salmonella enterica subsp. III (ex-Arizona) and Yersinia enterocolitica (34, 39).

In the establishment of French and international standards (3, 4, 5, 29, 30, 31), the enumeration of low numbers of fecal coliforms, with more attention paid to water than to foods, uses a most-probable-number calculation method, as in the United States (2, 6, 19, 22, 28, 37). However, this method is subject to variation, slow to arrive at a confirmed result, expensive, and labor-intensive (41). Enumeration of higher levels of fecal coliforms in foods can be carried out by using a violet red bile lactose agar (VRBL) medium (23, 33). However, the use of VRBL suffers from the need to discriminate colonies on the basis of size, and the agar must be cooled to 47 ± 2°C to avoid bacterial damage. The effect of the higher temperature on stressed coliforms as a result of the pour-plating procedure is another, unresolved problem (18, 38). The errors of the plate count method are also well known (20). Its advantage is that it produces confirmed results more rapidly at the expense of some sensitivity.

For this reason, Hsing-Chen and Wu (25) developed a new medium, fecal coliform agar (FCA), to recover stressed fecal coliforms after preincubation (42) of inoculated plates for 2 h at 37 ± 1°C before normal incubation for 22 h at 44 ± 1°C. FCA medium contains bile salts; lactose; bromocresol purple, which becomes yellow if lactose is used by bacteria (13); and calcium lactate, which precipitates around colonies after reaction with carbon dioxide produced by fecal coliforms (11). Thus, typical colonies grown on an FCA medium can be considered to be closer to the ISO definition of fecal coliforms than typical colonies grown on VRBL, as lactose fermentation and gas production are detected simultaneously.

This study was designed to evaluate the usefulness of FCA medium and to compare the performance of this medium to that of the reference standardized VRBL medium by using reference and laboratory strains and food samples, including when FCA was inoculated on the surface and VRBL was inoculated in mass.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and yeast strains.

Fifty bacterial and yeast strains (Table 1), used for the observation of the growth response in FCA and VRBL media, were collected from official reference institutions (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, Va.; Deutsche Sammlung von Mikrooganismen und Zelikulturen Gmbh [DSM], Braunschweig, Germany; Collection of the Pasteur Institute [IP], Paris, France; Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Universiteit of Ghent [LMG], Ghent, Belgium; National Collection of Industrial Bacteria [NCIB], Aberdeen, United Kingdom; and National Collection of Type Cultures [NCTC], London, United Kingdom) and from our laboratory collections (Collection of the Central Laboratory[LC], Armées, France, and Collection of Catholic University of Louvain-MBLA Unit [MA], Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium). The stock cultures of control strains were stored on cryobeads in a cryoprotectant (Armor Equipements Scientifiques Laboratoires, Combourg, France) in aliquots at −80°C, and subcultures of these control strains (stock cultures) were the sources for working cultures. To prepare working cultures, one cryobead of stock culture was placed in a test tube containing 10 ml of Nutrient Broth Standard II (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with 0.5% NaCl (except 3% for Vibrio parahaemolyticus) and incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 16 h. Nutrient Agar Standard II (Merck) slants were inoculated with this culture, controlled for purity, and stored at 3 ± 2°C.

TABLE 1.

Growth response of 50 bacterial and yeast strains on VRBL and FCA

| Species, subspecies, biovar, or serovar | Strain no. | Growth responsea on:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| FCA | VRBL | ||

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | MA AC00/008 | NG | NG |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | MA AH00/005 | NG | NG |

| Bacillus cereus | IP 64.52 | NG | NG |

| Bacillus subtilis | DSM 6633 | NG | NG |

| Citrobacter diversus | IP 72.11 | AT | AT |

| Citrobacter freundii | LC9601 | T | T |

| NCTC 9750 | AT | AT | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | LC9603 | T | T |

| Enterobacter intermedium | IP 79.27T | NG | NG |

| Enterobacter taylorae | LC9602 | NG | NG |

| Enterobacter sakazakii | LC9604 | T | T |

| Erwinia herbicola | MA EH82/373 | NG | NG |

| Escherichia coli | IP 54.8T | T | T |

| ATCC 10536 | T | T | |

| LC9605 | T | T | |

| Escherichia coli serovar O157:H7 | ATCC 35150 | T | T |

| Hafnia alvei | NCTC 8105 | AT | AT |

| LC9607 | T | T | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | NCIB 8017 | AT | AT |

| LC9606 | T | T | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. peumoniae | IP 82.91T | AT | AT |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | LC9610 | T | T |

| Lactobacillus brevis | NCIB 4036 | NG | NG |

| Lactobacillus fermentum | ATCC 14931 | NG | NG |

| Listeria innocua | LMG 11387 | NG | NG |

| Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4/b | LMG 10470 | NG | NG |

| Listeria welshimeri | MA LW95/110 | NG | NG |

| Proteus vulgaris | NCTC 4636 | AT | AT |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | NCIB 9046 | NG | NG |

| Pseudomonas putida | NCIB 9494 | NG | NG |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | MA SC00/011 | NG | NG |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Derby | LC9608 | AT | AT |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis | LC9609 | AT | AT |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Montevideo | MA SM96/08 | AT | AT |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Newport | LC9611 | AT | AT |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | LC9608 | AT | AT |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Virchow | LC9612 | AT | AT |

| Sarcina lutea | MA SL82/01 | NG | NG |

| Serratia marcescens | IP 103235T | NG | NG |

| NCTC 1377 | AT | NG | |

| Shigella sonnei | IP 106345 | AT | AT |

| Staphylococcus aureus | IP 4.83 | NG | NG |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | NCIB 9993 | NG | NG |

| Staphylococcus warnerii | LC9613 | NG | NG |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | MA VP82/05 | NG | NG |

| Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1 serovar O:8 | IP 1105 | AT | AT |

| Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 2 serovar O:9 | MA YE257/94 | AT | AT |

| Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 4 serovar O:3 | MA YE289/94 | NG | NG |

| Yersinia frederiksenii | MA YFE259/94 | AT | AT |

| Yersinia intermedia | MA YIE309/94 | AT | NG |

NG, no growth; T, typical colony; AT, atypical colony. A typical colony on FCA was yellow to yellow-green and surrounded by a pale yellow zone (diameter, 2 to 7 mm). A typical colony on VRBL was fuchsia with a diameter of approximately 0.5 mm and possibly surrounded by a reddish-fuchsia zone of 1 to 2 mm in diameter.

Preparation of media.

FCA medium was prepared with two separate solutions (25). Solution A contained tryptone (20 g) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), bile salts no. 3 (1.5 g) (Difco), lactose (10 g) (Merck), yeast extract (5 g) (Merck), and sodium chloride (5 g) (Merck). Solution B contained calcium lactate pentahydrate (14 g) (Merck) and β-glycerophosphate (1 g) (disodium salt; Merck). All ingredients of solution B were dissolved in 150 ml of distilled water at 50 ± 1°C, and all ingredients of solution A were dissolved in 850 ml of distilled water at 50 ± 1°C. Subsequently, solution B was mixed gradually into solution A and heated slowly on a heater with a magnetic agitator until the mixed solution became cloudy. The pH of the mixture was adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.2 with 1 N NaOH (Merck) after temperature correction of pH measurements. Subsequently, 3 ml of bromocresol purple solution (1 g of bromocresol purple [Merck] in 100 ml of 20% ethanol, protected against light) and 12 g of agar (Merck) were added to the mixture. The final mixture was boiled, agitated for approximately 2 min, and then cooled at 47 ± 2°C before being pour plated and solidified before spread plating. FCA plates, with a final pH of 7.0 ± 0.2 at 25°C, were stored in hermetic plastic bags in darkness at laboratory temperature (or 8 ± 2°C) due to the risk of bile salt precipitation at 3 ± 2°C.

VRBL was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions, using ready-to-use VRBL powder medium (Merck). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1. The medium was boiled for no more than 2 min until it was completely dissolved and then was cooled and stored at 47 ± 2°C for no more than 3 h before being poured into plates.

Moisture and water activity.

We used the method of Alexander and Marshall (1) to examine changes in moisture and water activity of FCA during incubation. Briefly, 15 ml of FCA medium was poured into petri dishes (100 by 15 mm), which were preweighed to the nearest milligram (±0.001 g) on precision scales (Mettler-Toledo, Zurich, Switzerland). The results were plotted for four plates, two for the top incubator shelves and two for the bottom, ensuring that the plates remained inside the working zone 25 mm from the incubator wall. Plates were weighed after incubation at 37 ± 1°C for 2 h and 44 ± 1°C for 22 h in an incubator (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) containing only the plates being tested. The incubator temperature was controlled by thermic probes connected to a temperature measurement recorder (Memodata; Armor Equipements Scientifiques Laboratoires). Amounts of moisture evaporated from the agar medium in plates were calculated from the differences between initial weights and weights after 24 h of incubation. Ten repetitions were performed.

Selective tests using reference strains.

Working cultures of 50 reference and laboratory strains were streaked onto FCA medium in order to allow their growth response to be observed. The size and color of colonies and precipitates around them were examined after incubation at 37 ± 1°C for 2 h and after 22 h at 44 ± 1°C. For VRBL medium, working cultures of reference and laboratory strains were diluted to obtain 10 to 100 CFU/ml, and this dilution was incorporated in the medium for observation of strains' growth responses. The size and color of colonies and precipitates around them were examined after incubation at 44 ± 1°C for 24 h.

FCA and VRBL media were compared by using E. coli IP 54.8T. Serial 10-fold dilutions of a working culture, enumerated on plate count agar (PCA) (Merck) after 72 h at 30 ± 1°C, in buffered peptone water (Merck) were made to obtain suspensions containing 10 to 109 CFU/ml. The plates, two per serial 10-fold dilution for each medium, inoculated with the bacteria were subjected to 37 ± 1°C for 2 h and then transferred to 44 ± 1°C for 22 h for the FCA medium and to 44 ± 1°C for 24 h for the VRBL medium. After incubation, colonies on FCA and VRBL were enumerated and described. Typical colonies on the FCA medium were yellow to yellow-green surrounded by a pale yellow zone (diameter, 2 to 7 mm), and typical colonies on VRBL medium were fuchsia with a diameter of approximately 0.5 mm and sometimes surrounded by a reddish-fuchsia zone (1 to 2 mm in diameter) of precipitated bile salts, which revealed lactose degradation in acid. On the VRBL medium, pale colonies with greenish zones reflected lactose fermentation by fecal coliforms, which appeared slowly.

Preincubation test.

For testing the recovery of injured bacteria, working cultures of E. coli (IP 54.8T) incubated for 16 h in 10 ml of Nutrient Broth Standard II (Merck) were prepared. The CFU of the suspension per milliliter were enumerated using PCA after 72 h at 30 ± 1°C. In addition, 15 bottles of sterilized mashed potatoes were prepared by reconstituting 10 g of lyophilized mashed potatoes in 90 ml of distilled water in each bottle. The bottles were then autoclaved (115 ± 1°C, 20 min) and tested for sterility on PCA (30 ± 1°C, 72 h).

Each bottle of sterilized mashed potatoes was inoculated under sterile conditions with 1 ml of E. coli working culture, homogenized, and incubated for 1 h at 37 ± 1°C to allow bacteria to adapt to the new medium. Enumeration on PCA (30 ± 1°C, 72 h) was carried out directly with three bottles. Six other bottles inoculated with reconstituted mashed potatoes were refrigerated at 2 ± 2°C, and another six were frozen at −18 ± 2°C. Three bottles from each group were collected after 7 days at each temperature, and the other three were collected after 14 days at each temperature. The frozen bottles of inoculated mashed potatoes were then thawed at room temperature for 90 min. For the contents of each bottle, enumeration of E. coli was carried out by spreading on PCA and FCA and in the VRBL medium. FCA and VRBL plates were preincubated at 37 ± 1°C for 0, 2, and 4 h prior to incubation at 42 ± 1°C or 44 ± 1°C for 20, 22, and 24 h. Enumeration on the FCA medium was thus compared with that by the modified standardized VRBL method, except when VRBL was not preincubated at 37 ± 1°C and was incubated only at 44 ± 1°C for 24 h.

Selective tests using food samples.

Food samples, including mostly raw or processed food products (meats, vegetables, milk products, prepared meals, seafood, spices, and dehydrated foods), had been collected by an army veterinary corps, frozen at −18 ± 2°C for 24 to 72 h, and then thawed overnight at 2 ± 2°C. Some food samples purchased from retail markets, such as cheese, were only refrigerated. Each solid food sample was homogenized and 10-fold diluted with buffered peptone water broth after 15 min of resuscitation. Fecal coliforms in each food were enumerated using FCA and VRBL plates, in conformity with standard ISO 7218 (32). For FCA, the inoculum (1 ml of homogenate) was spread in three petri dishes. For subsequent serial dilution, the FCA was inoculated with 0.1 ml of the serial 10-fold dilutions and the VRBL was inoculated with 1 ml. From different food samples after the final incubation (FCA, 37 ± 1°C for 2 h to 44 ± 1°C for 22 h; VRBL, 44 ± 1°C for 24 h), typical and atypical colonies were enumerated. Some colonies were selected on the basis of divergence of morphological appearance and picked. These last colonies were purified on Nutrient Agar Standard II (Merck) incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 24 h. For each isolate, Gram staining, using the Kligler-Hajna test (Merck), and gas production during lactose fermentation (8, 12, 35) were observed with Durham tubes in E. coli broth (Merck) after 48 h at 44 ± 0.5°C, and each isolate was finally identified by using an API 20E (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. With these results, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for each medium (7).

Statistical methods.

To ensure data normality, the colony counts (CFU per gram or CFU per milliliter) were transformed to log counts (log CFU per gram or log CFU per milliliter). Counts reported as <1 or <0.1 were set equal to 0 during statistical analysis. Analysis of variance (with the variables of Table 2, i.e., media, preincubation temperature, incubation temperature, stock storage time, and stock temperature), performed with SAS software (45), was used for tests of significance and completed by the Newman-Keuls test if interaction took place. Linear correlation between plate counts on FCA and VRBL was determined as described by Snedecor and Cochran (46). The sign test (45, 46) was also used to compare VRBL and FCA results for food samples.

TABLE 2.

Recovery of refrigerated and freeze-stressed E. coli IP 54.8T inoculated in mashed potatoes after preincubation at 37 ± 1°C for 0, 2, or 4 h prior to incubation at 42 ± 1°C or 44 ± 1°C for 20, 22, or 24 h

| Time (days) and temp (°C) for storage of inoculated mashed potatoes | Log CFU/g (mean ± SD) on PCA at 30 ± 1°C | % of cold- stressed cellsa | Log CFU/g (mean ± SD)b

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRBL

|

FCA

|

|||||||||||||

| 42 ± 1°C

|

44 ± 1°C

|

42 ± 1°C

|

44 ± 1°C

|

|||||||||||

| 0c | 2c | 4c | 0d | 2c | 4c | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |||

| 0, 0e | 7.05 ± 0.01 | 0 | 7.05 ± 0.01 | 7.05 ± 0.02 | 7.05 ± 0.02 | 7.15 ± 0.07 | 7.15 ± 0.06 | 7.10 ± 0.06 | 7.00 ± 0.05 | 6.92 ± 0.06 | 7.15 ± 0.15 | 7.06 ± 0.02 | 7.05 ± 0.03 | 6.80 ± 0.03 |

| 7, 2 ± 2 | 6.11 ± 0.07 | 13.3 | 4.83 ± 0.02 | 4.80 ± 0.02 | 4.77 ± 0.03 | 4.73 ± 0.03 | 4.73 ± 0.03 | 4.62 ± 0.02 | 5.96 ± 0.12 | 5.98 ± 0.03 | 5.97 ± 0.07 | 6.00 ± 0.11 | 5.93 ± 0.03 | 5.81 ± 0.20 |

| 14, 2 ± 2 | 5.59 ± 0.11 | 20.7 | 4.10 ± 0.10 | 4.06 ± 0.13 | 4.02 ± 0.06 | 3.99 ± 0.08 | 3.98 ± 0.11 | 3.95 ± 0.10 | 5.08 ± 0.02 | 5.12 ± 0.03 | 5.14 ± 0.10 | 5.09 ± 0.08 | 5.05 ± 0.05 | 5.00 ± 0.03 |

| 7, −18 ± 2 | 5.78 ± 0.22 | 18.0 | 4.08 ± 0.13 | 4.18 ± 0.20 | 4.13 ± 0.12 | 4.11 ± 0.15 | 4.10 ± 0.18 | 4.09 ± 0.23 | 4.92 ± 0.02 | 4.83 ± 0.05 | 4.80 ± 0.10 | 4.98 ± 0.02 | 5.02 ± 0.02 | 5.11 ± 0.19 |

| 14, −18 ± 2 | 5.41 ± 0.03 | 23.3 | 3.51 ± 0.03 | 3.08 ± 0.08 | 3.95 ± 0.05 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | 3.65 ± 0.35 | 4.00 ± 0.30 | 4.54 ± 0.07 | 4.89 ± 0.25 | 4.66 ± 0.05 | 4.62 ± 0.14 | 4.69 ± 0.02 | 4.79 ± 0.05 |

The percentage of cold-stressed cells was calculated by enumeration of cells in artificially contaminated mashed potatoes before and after cold preservation.

Results with their standard deviations are for the indicated media, incubation temperatures, and times (hours) of preincubation at 37 ± 1°C. Incubation was for 24, 22, and 20 h for preincubation times of 0, 2, and 4 h, respectively.

Modified standardized VRBL method for fecal coliform enumeration with a preincubation step before incubation or different temperature of incubation.

Standardized VRBL method (2) for fecal coliform enumeration with incubation at 44 ± 1°C for 24 h.

Initial artificial contamination.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Remarks on FCA medium.

Hsing-Chen and Wu (25) replaced K2HPO4 and KH2PO4 with β-glycerophosphate as a potassium phosphate source for bacteria in order to avoid calcium lactate precipitation during medium preparation. Nevertheless, precipitates have appeared after boiling when the temperature of the medium is brought to 47 ± 2°C. To prevent clouding of the medium, the calcium lactate must be added to sterile basal agar cooling at 47 ± 2°C after being dissolved in distilled water with mild heating and filter sterilizing using a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter. In addition, this FCA medium must be kept for a maximum of 3 h at 47 ± 2°C to avoid sedimentation in the medium.

Alexander and Marshall (1) stated that agar medium in plates should not lose more than 15% of its weight in 48 h of incubation. When FCA plates were incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 2 h and at 44 ± 1°C for 22 h, moisture lost by evaporation was on average 5.8% for plates on the top shelf of the incubator and 6.1% for plates on the bottom shelf (data not shown). The position of plates in the incubator is of great importance. Even if characterization of the thermostatic incubator for a given laboratory meets accreditation requirements, differences in incubator heat production systems can produce variations related to the position of plates.

FCA and VRBL specificity and sensitivity.

The appearance of colonies of 50 bacterial and yeast strains on FCA and VRBL is shown in Table 1. Laboratory strains were used because they were more similar to the normal strains found in the food matrices in our laboratory. These strains sometimes have biochemical characteristics, resulting from bacterial evolution, that are absent in bacterial reference strains.

Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus, Listeria, and Staphylococcus and some gram-negative bacteria such as Enterobacter intermedium, Enterobacter taylorae, Pseudomonas putida, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae could not be grown on FCA and VRBL, which shows their selectivity. C. diversus, C. freundii NCTC 9750, Hafnia alvei NCTC 8105, K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae IP 82.91T, K. oxytoca NCIB 8017, Proteus vulgaris, S. enterica, Shigella sonnei, and Y. enterocolitica biovars 1 and 2 produced no typical colonies on FCA and VRBL.

C. freundii LC9601, Enterobacter sakazakii, E. coli, H. alvei LC9607 (lactose positive), K. oxytoca LC9606, and K. pneumoniae LC9610 produced typical colonies. Some non-fecal coliforms tested were able to grow on FCA and produced typical colonies. This fact reflects the capacity of atypical strains to ferment lactose and produce gas, as with H. alvei (48).

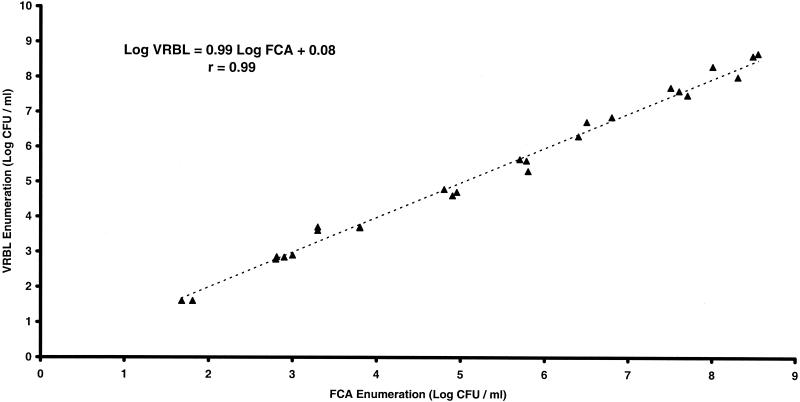

Figure 1 shows enumerations of a serial 10-fold dilution of culture of E. coli IP 54.8T on FCA and VRBL. Each enumeration was made in triplicate. These enumerations are not significantly different (P > 0.05) and show good correlation, with a correlation coefficient of 0.99.

FIG. 1.

Correlation of enumerations of E. coli IP 54.8T using FCA or VRBL medium suspended in buffered peptone water.

Preincubation test.

Resuscitation of stressed bacteria is still a major problem for food microbiologists, as it tends to underestimate numbers of bacteria such as fecal coliforms cultivated in selective media incubated at 44°C (14). The use of a preincubation time to allow injured bacteria to recover (9, 17) and to prepare them for a selective temperature of 44°C was investigated.

Recovery of E. coli IP 54.8T in refrigerated (2 ± 2°C for 7 and 14 days) and frozen (−18 ± 2°C for 7 and 14 days) mashed potatoes was evaluated by preincubating media with cold-stressed bacteria at 37 ± 1°C for 0, 2, and 4 h prior to incubation at 42 ± 1°C or 44 ± 1°C for 20, 22, and 24 h (Table 2). There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the enumeration values of log CFU per gram with and without preincubation in either frozen, refrigerated, or control inoculated mashed potatoes.

A highly significant effect (P < 0.001) on the enumeration at stock temperature and of interaction between stock temperature and stock storage time was observed. This last effect could be explained by different levels of cold stress on cells and the impact on resuscitation of these cells with the media.

No influence of incubation temperature of the media was observed, which goes against Leclerc and Mossel's proposition (34) based on Eijkman's observations (16) involving the reduction of medium temperature from 44 to 42°C (34), which Eijkman found changed the growth selection. There are fewer divergent opinions about the temperature and duration of incubation recommended for plated media than about those for broths (49).

Around a 1-log-unit difference in counts enumerated by PCA and by FCA or VRBL in control and treated samples was observed. Selective components of FCA and VRBL media could affect growth of unhealthy cells in control and freeze-stressed inoculated mashed potatoes. The lactose in FCA or VRBL medium was transformed to organic acids, which are harmful to the cells (26). Also, the main difference between FCA on the one hand and VRBL or PCA on the other is the mode of inoculation. Control samples excepted, enumeration using FCA was in general 1 log unit higher than enumeration using VRBL. However, these results were limited in that inoculation of sterilized mashed potatoes with only one strain did not reflect strain variation in sensitivity to cold stress and recovery by specific media of these other unhealthy cells.

Growth response of bacteria in foods.

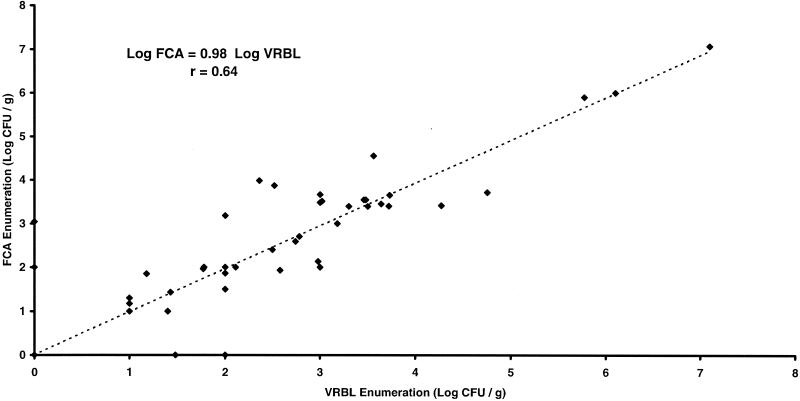

For 170 varied food samples, fecal coliform counts on VRBL and FCA (20) were not significantly different (P > 0.05). Only 44 food samples (26%) were positive for fecal coliforms on FCA and/or VRBL (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Correlation of enumerations of fecal coliforms in 170 food samples using FCA and VRBL media.

VRBL was inoculated by pour plating, and FCA was inoculated on a surface. An attempt to inoculate FCA by pour plating was made. Fermentative bacteria, such as E. coli, metabolize sugars anaerobically to produce organic acids, but if oxygen is available, these are in turn broken down to water and carbon dioxide, which escapes from the pH indicator media. Less acid is therefore produced under aerobic than under anaerobic or semianaerobic conditions (for example, at the surface compared to the depths of a thick agar plate). However, the pour plating procedure (1 ml of homogenate seeded as for VRBL) created gas bubbles in the medium around colonies, which hindered observation.

From 25 food samples (7 cheese, 7 minced beef, 7 sausage meat, and 4 vegetable), typical and atypical colonies growing on FCA and VRBL were selected on the basis of divergence of morphological aspects, picked, purified, and identified (Table 3). For FCA, 80 typical and 52 atypical colonies were isolated, compared to 53 typical and 18 atypical colonies for VRBL.

TABLE 3.

Identification and biochemical characterization of colonies picked from FCA and VRBL media isolated from 25 food samples (7 cheese, 7 minced beef, 7 sausage meat, and 4 vegetables)

| Identification | Type of coliform | No. of identified colonies | Food origin of identified coloniesa | No. of typical colonies

|

No. of atypical colonies

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactose+, gas+

|

Lactose+, gas−

|

Lactose+, gas+

|

Lactose−, gas−

|

||||||||

| FCA | VRBL | FCA | VRBL | FCA | VRBL | FCA | VRBL | ||||

| Citrobacter freundii | Fecal | 3 | C, M, S | 3 | |||||||

| Enterobacter aerogenes | Fecal | 1 | S | 1 | |||||||

| Enterobacter agglomerans | Clinical | 2 | V | 2 | |||||||

| Enterobacter amnigenus | Telluric/aquatic | 1 | C | 1 | |||||||

| Enterobacter cloacae | Fecal | 28 | C, M, S, V | 7 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 3 | |

| Enterobacter sakazakii | Clinical | 22 | C, M, S, V | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Escherichia coli | Fecal | 85 | C, M, S, V | 44 | 22 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Hafnia alvei | Non coliform | 56 | C, S | 7 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 24 | 3 | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Fecal | 1 | C | 1 | |||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Fecal | 2 | S | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Serratia liquefaciens | Telluric/aquatic | 1 | S | 1 | |||||||

| Serratia marcescens | Clinical | 1 | S | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 203 | 65 | 36 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 45 | 8 | ||

C, cheese; M, minced beef; S, sausage meat; V, vegetables.

Verification of 203 colonies picked from the FCA and VRBL media is shown in Tables 3 and 4. Verification of fecal coliforms characteristic of typical colonies for all samples showed an average of 76% accuracy on FCA and 56.6% on VRBL. For atypical colonies, verification gave 71.1% accuracy on FCA and 16.6% on VRBL. From the data in Table 4, the performance of media (7) was calculated as follows: sensitivity is the number of true-positive microorganisms divided by the number of confirmed fecal coliform bacteria, specificity is the number of true-negative microorganisms divided by the number of confirmed non-fecal-coliform bacteria, PPV is the number of typical colonies confirmed as fecal coliform bacteria divided by the number of typical colonies, and NPV is the number of atypical colonies confirmed as non-fecal-coliform bacteria divided by the number of typical colonies. The sensitivity of FCA was 65%, compared to 11.5% for VRBL. The specificity of FCA was 80%, compared to 66.6% for VRBL. The FCA PPV was 75%, and the NPV was 71%. The VRBL PPV was 56.6%, and the NPV was 16.6%. These results show that FCA has higher performance characteristics than VRBL for the enumeration of fecal coliforms. Nevertheless, these values were obtained from identification of picked colonies, and the number of these colonies for VRBL is not equivalent to the number for FCA; this could influence the results.

TABLE 4.

Efficacy of methods using FCA or VRBL to recover coliforms

| Picked colonies | Medium | No. of colonies confirmed as fecal coliforms | No. of colonies confirmed as non-fecal coliforms | Total no. of colonies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical | FCA | 60a | 20b | 80 |

| VRBL | 30a | 23b | 53 | |

| Atypical | FCA | 15c | 37d | 52 |

| VRBL | 15d | 3d | 18 | |

| Total | FCA | 75 | 57 | 132 |

| VRBL | 45 | 26 | 71 |

True positive.

False positive.

False negative.

True negative.

These data indicate that some colonies that were not yellow were also verified as fecal coliforms by biochemical tests for FCA. However, misidentification of typical colonies as fecal coliforms on VRBL seems to be a problem. These fecal coliforms, which are not characteristic colonies on either medium, might be injured or physiologically compromised organisms that probably could not have survived exposure to 44 ± 1°C but were able to repair themselves and grow at 37 ± 1°C, even though some of them produced insufficient acidity and gas to be detected by the lactose fermentation assay (24, 36). The typical colonies on VRBL and FCA, which do not produce gas from lactose, could also be stressed or late lactose-fermenting bacteria. Moreover, it was reported that other organisms, such as P. vulgaris, were capable of suppressing gas formation by E. coli in lactose-containing media (27, 44, 48).

Based on the work of Reasoner et al. (43) and Francis et al. (21), an optimum incubation temperature of 41.5°C was used for quantification of fecal coliforms after the resuscitation step, incorporating d-mannitol (which is used by most members of Enterobacteriaceae, including 96% of the genus Escherichia [15]) at 0.5% in the formulation of FCA medium. This incorporation allows the yellow color to become deeper. Total substitution of mannitol in place of lactose was not satisfactory; yellow colony color development seems to be best only when both lactose and mannitol are present. Incorporation of two fermentable substrates offers stressed organisms the option of two metabolic pathways, which facilitates more rapid repair and growth of the injured organisms. This coupling permits resuscitation of stressed fecal coliforms and enables production of sufficient acid from lactose and mannitol to shift the pH indicator color. No significant results in this regard were obtained in our study, due to the presence of false-positive results (data not shown).

Typical colonies on FCA were identified in these proportions: 57.5% as E. coli and 17.5% as E. cloacae (fecal coliforms) and 13.8% as H. alvei, 8.7% as E. sakazakii, and 2.5% as Enterobacter agglomerans (non-fecal coliforms). On VRBL, typical colonies were identified as follows: 49% as E. coli and 7.5% as E. cloacae (fecal coliforms) and 34% as H. alvei and 9.5% as E. sakazakii (non-fecal coliforms). With regard to recently resurgent serious taxonomic objections to the term fecal coliforms, it is recommended that this superfluous and misleading terminology be abolished. It seems to be more useful to enumerate E. coli as a privileged and specific fecal indicator. Leclerc and Mossel (34) showed that more than 99% of identified fecal coliforms are E. coli, and it is probable that at the test temperature of 44 to 44.5°C, E. coli in the presence of other fecal coliforms has a growth advantage. It is also probable that this temperature eliminated a percentage of fecal coliforms other than E. coli, resulting in false negatives. Our results support this idea, but in our study, approximately half of typical colonies in food samples on FCA and VRBL media were identified as E. coli, in contrast to 99% in Leclerc and Mossel's study of water samples (34).

Enumeration of fecal coliforms in foods on FCA was well correlated with the standardized method using the VRBL medium. However, enumeration of stressed fecal coliforms is higher on FCA. This medium is easy to use (no prior preparation, no autoclaving, and no pouring of overlaid medium) and is easy to read due to good color contrast, but it has the disadvantage of being difficult to prepare.

A high proportion of typical colonies of E. coli on these media again raises the question of utilization of E. coli rather than fecal coliforms as a fecal contamination indicator (40). This doubt is reinforced by the fact that a large proportion of H. alvei, a non-fecal coliform, was enumerated as for fecal coliforms.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Health Service and Quartermaster Corps for their financial support.

We thank H. Leclerc (Medicine Faculty of Lille, Lille, France), D. A. A. Mossel (Eijkman Foundation, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and E. Grenier (Agricultural Institute of Beauvais, Beauvais, France) for their help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, R. N., and R. T. Marshall. 1982. Moisture loss from agar plates during incubation. J. Food Prot. 45:162-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Public Health Association. 1984. Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods, 2nd ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Association Française de Normalisation. 1980. NF_V_08_017: microbiologie alimentaire—directives générales pour le dénombrement des coliformes fécaux et d'Escherichia coli. Association Française de Normalisation, Paris, France.

- 4.Association Française de Normalisation. 1996. NF_V_08_060: microbiologie des aliments—dénombrement des coliformes thermotolérants par comptage des colonies obtenues à 44 degrés Celsius—méthode de routine. Association Française de Normalisation, Paris, France.

- 5.Association Française de Normalisation. 1982. NF_V_59_103: gélatine alimentaire—recherche des coliformes fécaux—méthode par culture à 44.5 degrés Celsius sur milieu sélectif liquide. Association Française de Normalisation, Paris, France.

- 6.Association of Official Agricultural Chemists. 1984. Official method of analysis. 14th ed. Association of Official Agricultural Chemists, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Baylac, P., M. F. Cordat-Hagenbach, and J. P. Chevrier. 1990. Technique originale d'identification rapide d'Escherichia coli dans les aliments. Méd. Armées. 18:305-308. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner, D. N. 1984. Enterobacteriaceae, p. 408-420. In N. R. Krieg and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan, R. L., and L. A. Klawitter. 1992. The effect of incubation temperature, initial pH, and sodium chloride on the growth kinetics of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Food Microbiol. 9:185-196. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttiaux, R., and D. A. A. Mossel. 1961. The significance of various organisms of faecal origin in foods and drinking water. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Lille) 24:353. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cirigliano, M. C. 1982. A selective medium for the isolation and differentiation of Gluconobacter and Acetobacter. J. Food Sci. 47:1038-1039. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark, J. A., C. A. Burger, and L. E. Sabatinos. 1982. Characterization of indicator bacteria in municipal raw water, drinking water, and new main water samples. Can. J. Microbiol. 28:1002-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke, B. C., M. A. Jorgensen, and A. B. MacDonald. 1985. Effect of four presumptive coliform test media, incubation time and product inoculum size on recovery of coliforms from dairy products. J. Food Prot. 48:388-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corry, J. E. L. 1982. Quality assessment of culture media by the Miles-Misra method, p. 21-37. In J. E. L. Corry (ed.), Quality assurance and quality control of microbiological culture media. G.I.T.-Verlag, Darmstadt, Germany.

- 15.Edwards, P. R., and W. H. Ewing. 1972. Identification of Enterobacteriaceae, 3rd ed. Burgess Publishing Co., Minneapolis, Minn.

- 16.Eijkman, C. 1904. Die Gärunsprobe bei 46° als Hilfsmittel bei der Trinkwasseruntersuchung. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. 37:742-752. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans, T. M., R. J. Seidler, and M. W. Le Chevallier. 1981. Impact of verification and resuscitation on accuracy of the membrane filter total coliform enumeration technique. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:1141-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firstenberg-Eden, R., M. L. Van Sise, J. Zindulis, and P. Kahn. 1984. Impedimetric estimation of coliforms in dairy products. J. Food Sci. 49:1449-1452. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Food and Drug Administration. 1992. Bacteriological analytical manual, 7th ed. AOAC International, Arlington, Va.

- 20.Fowler, J. L., W. S. Clark, Jr., J. F. Foster, and A. Hopkins. 1978. Analyst variation in doing the standard plate count as described in Standard Methods for the Examination of Dairy Products. J. Food Prot. 1:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis, D., J. Peelerand, and R. Twedt. 1974. Rapid method for detection and enumeration of fecal coliforms in fresh chicken. Appl. Microbiol. 27:1127-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall, H. E. 1964. Methods of isolation and enumeration of coliform organisms, p. 52-60. In K. H. Lewis and R. Angelotti (ed.), Examination of foods for enteropathogenic and indicator bacteria; review of methodology and manual of selective procedures. Public Health Service publication 1142. Division of Environmental Engineering and Food Protection, U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Hartman, P. A. 1960. Further studies on the violet red bile agar. J. Milk Food Technol. 23:45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoadley, A. W., and C. M. Cheng. 1974. The recovery of indicator bacteria on selective media. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 37:45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsing-Chen, C., and S. D. Wu. 1992. Agar medium for enumeration of faecal coliforms. J. Food Sci. 57:1454-1457. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussong, D., J. M. Damare, R. M. Weiner, and R. R. Colwell. 1981. Bacteria associated with false-positive most-probable-number coliform test results for shellfish and estuaries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:35-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchinson, D., R. E. Weaver, and M. Scherago. 1943. The incidence and significance of microorganisms antagonistic to Escherichia coli in water. J. Bacteriol. 45:29. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods. 1978. Microorganisms in foods. I. Their significance and methods of enumeration, 2nd edition. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada.

- 29.International Dairy Federation. 1985. IDF 73A:1985: enumeration of coliforms—colony count technique and most probable number technique at 30°C. International Dairy Federation, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 30.International Organization for Standardization. 1991. ISO 4831: microbiology—general guidance for the enumeration of coliforms—most probable number technique. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 31.International Organization for Standardization. 1991. ISO 4832: microbiology—general guidance for the enumeration of coliforms—colony count technique. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 32.International Organization for Standardization. 1996. ISO 7218: microbiologie des aliments—règles générales pour les examens microbiologiques. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 33.Klein, H., and D. Y. C. Fung. 1976. Identification and quantification of faecal coliforms using violet red bile agar at elevated temperature. J. Milk Food Technol. 39:768-770. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leclerc, H., and D. A. A. Mossel. 1989. Microbiologie de l'eau, p. 361-366. In H. Leclerc (ed.), Microbiologie: le tube digestif, l'eau et les aliments. Doin, Paris, France.

- 35.Mara, D. 1973. A single medium for the detection of Escherichia coli at 44°C. J. Hyg. 71:783-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxcy, R. B. 1973. Condition of coliform organisms influencing recovery of subcultures on selective media. J. Milk Food Technol. 36:414-416. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehlman, I. J. 1984. Coliforms, faecal coliforms, Escherichia coli and enteropathogenic E. coli, p. 342-369. In M. L. Speck (ed.), Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods, 2nd ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 38.Mossel, D. A. A., I. Eelderink, M. Koopmans, and F. van Rossem. 1979. Influence of carbon source, bile salts and incubation temperature on the recovery of Enterobacteriaceae from foods using MacConkey type agars. J. Food Prot. 42:470-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mossel, D. A. A. 1982. Marker (index and indicator) organisms in food and drinking water. Semantics, ecology, taxonomy and enumeration. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 48:609-611.7168562 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mossel, D. A. A. 1997. Request for opinions on abolishing the term fecal coliforms. ASM News 63:175. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierson, C. J., B. S. Emswiler, and A. W. Kotula. 1978. Comparison of methods for estimation of coliforms, faecal coliforms and enterococci in retail ground beef. J. Food Prot. 41:263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rayman, M. K., G. A. Jarvis, C. M. Davidson, S. Long, J. M. Allen, T. Tong, and P. Dodsworth, S. McLaughlin, S. Greenberg, B. G. Shaw, H. J. Beckers, S. Qvist, P. M. Nottingham, and B. J. Stewart. 1979. ICMSF methods studies. XIII. An international comparative study of the MPN procedure and the Anderson-Baird-Parker direct plating method for enumeration of Escherichia coli biotype I in raw meats. Can. J. Microbiol. 25:1321-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reasoner, D. J., J. C. Blannon, and E. E. Geldreich. 1979. Rapid seven-hour fecal coliform test. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38:229-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson, B. J. 1984. Evaluation of a fluorogenic assay for detection of Escherichia coli in foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:285-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.SAS Institute Inc. 1987. Statistical analysis system. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.

- 46.Snedecor, G. W., and W. G. Cochran. 1980. Statistical methods, 7th ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 47.Solberg, M., D. Miskimin, B. Martin, G. Page, S. Goldner, and M. Libfeld. 1976. What do microbiological indicator tests tell us about the safety of foods? Food Product Dev. 10:72-80. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straight, J. V., D. Ramkrisha, S. J. Parulekar, and N. B. Jansen. 1989. Bacterial growth on lactose: an experimental investigation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 34:705-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss, K. F., H. Chopra, P. Stotland, G. W. Riedel, and S. Malcom. 1983. Recovery of faecal coliforms and of Escherichia coli at 44.5, 45.0 and 45.5°C. J. Food Prot. 46:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]