Abstract

Thermogenic adipose tissues, including brown and beige, exhibit remarkable cellular and metabolic adaptations to environmental and physiological cues, contributing to improved metabolic health. Among these adaptations, adipose progenitor cells (APCs), a heterogeneous cell population comprising distinct subsets, play a crucial role in generating thermogenic adipocytes and promoting healthy adipose tissue remodeling and metabolic homeostasis. Therefore, targeting APCs offers a potential therapeutic approach for regulating adipose plasticity and remodeling to address metabolic dysregulation. The precise identity of APCs and the roles of specific APC subtypes in metabolic regulation and diseases remain to be elucidated. Here, we summarize recent findings on the lineage of APCs that give rise to thermogenic adipocytes and how environmental conditions regulate their proliferation and differentiation. Finally, we discuss the potential of targeting APCs as an alternative therapeutic strategy to combat metabolic diseases.

Keywords: Adipocyte progenitor cells, thermogenesis, obesity, metabolism

Summary:

This article summarizes the role of adipose progenitor cells in thermogenic adipocyte development and metabolic regulation.

1. Introduction

Obesity and its metabolic abnormalities, including dyslipidemia, fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, affect over 650 million people worldwide (1). Therefore, it is essential to develop effective and safe therapeutic strategies for treating obesity and its complications. Notably, obesity occurs due to changes in adipose tissue composition and function; thus, understanding adipose adaptation in obesity is crucial for metabolic health (2).

In mammals, adipose tissues are pivotal to regulating whole-body metabolic homeostasis and are classified as white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). Functionally, they are divided into brown, white, and beige adipocytes (3). While WAT is mainly responsible for energy storage, BAT is primarily involved in non-shivering thermogenesis (4). Beige adipose tissue, which refers to brown-like adipocytes (or beige adipocytes) emerging in WAT, is originally from WAT but shares characteristics with BAT (3). During cold challenges, brown and beige adipocytes, collectively referred to as thermogenic adipocytes, dissipate energy to produce heat for cold-induced thermogenesis, thereby maintaining body core temperature and energy balance (5, 6). Recent studies have shown that BAT in humans is significantly correlated with lower incidences of type 2 diabetes and cardiometabolic disease (7). Its presence also regulates body fat distribution by reducing visceral WAT in humans, thereby supporting its role in protecting against obesity and eventually improving metabolic health (7, 8). Pharmacological or cold-induced activation of thermogenic adipocytes enhances metabolic phenotype in obese individuals (9-11). These studies indicate the vital roles of thermogenic adipocytes in promoting metabolic health.

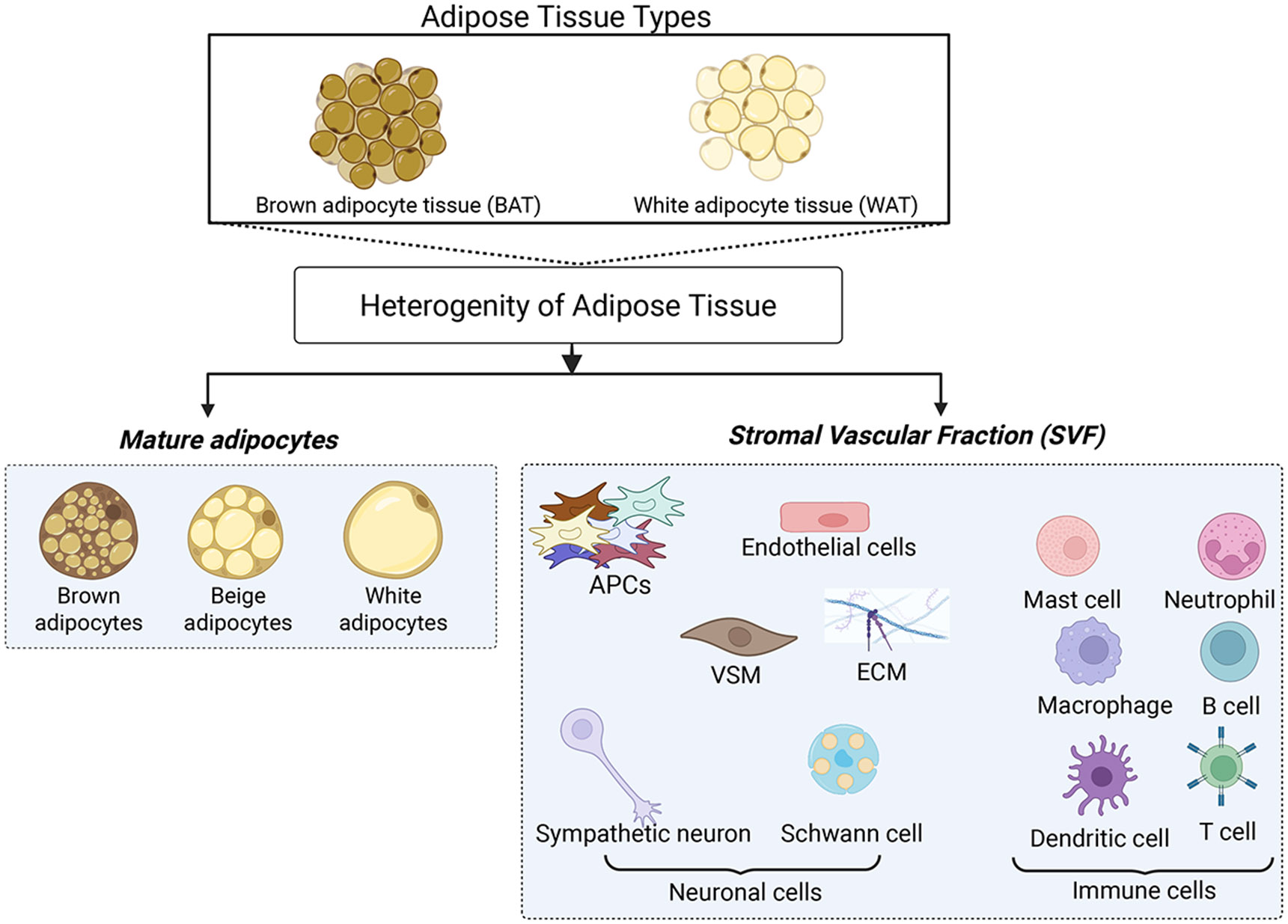

Adipose tissue is a metabolically active tissue composed of various cell types, including endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle, fibroblasts, immune cells, extracellular matrix, adipocyte progenitor cells, and adipocytes (2, 12, 13) (Figure 1). Each cell type possesses unique capabilities to regulate metabolism, energy storage, endocrine signaling, inflammation, and thermogenesis, thereby impacting whole-body physiology and metabolic regulation (2). In obesity, dysregulation of adipose tissue function is linked to the occurrence and development of these metabolic diseases (14). Adipose tissue also adapts to physiological and environmental changes, such as hormonal influences, nutritional factors, temperature fluctuations, and sympathetic signals (15). Since mature adipocytes cannot undergo cell division, new adipocytes are formed from adipocyte precursor cells, including adipose progenitor cells (APCs) and preadipocytes, within the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) (16). Recent studies have also shown that the diversity of APCs plays a crucial role in adipose tissue turnover, remodeling, and expansion, thereby contributing to the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis and thermoregulation (17).

Figure 1. Types of Adipose Tissue and Their Cellular Composition.

This figure depicts the main types of adipose tissue, including brown adipose tissue (BAT) and white adipose tissue (WAT). Adipose tissues consist of mature adipocytes (brown, beige, or white) and various non-adipocyte cell types in the stromal vascular fraction (SVF). The SVF includes adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs), endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle (VSM), extracellular matrix (ECM), neuronal cells, and immune cells. Together, these cell types play a crucial role in the remodeling, functionality, and metabolic regulation of adipose tissue. Created in BioRender. Tseng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z35q434.

Many APCs can give rise to various types of adipocytes, including brown, beige, and white adipocytes. In this review, we focus on APCs that can give rise to thermogenic adipocytes and explore their roles in the development and plasticity of thermogenic adipose tissue. We also examine the activation of APCs to form thermogenic adipocytes in response to external and physiological factors such as diet, temperature, exercise, sex, and aging. Finally, we highlight therapeutic advances targeting APCs through genetic, pharmacological, and cell-based approaches to combat obesity and improve metabolic health.

2. Adipocyte Progenitor Cells that Give Rise to Thermogenic Adipocytes

2.1. The Origin and Development of Thermogenic APCs

Mature adipocytes are post-mitotic and require specialized cell types to form new thermogenic adipocytes during adipose tissue development and remodeling (18). These specialized cells are distinct progenitors derived from the embryonic mesoderm and ectodermal neural crest (19-22). During adipose tissue development, APCs first undergo the commitment phase to become preadipocytes, followed by a differentiation phase that generates mature adipocytes. During this adipogenesis process, the cells exhibit distinct marker expressions (16, 22).

In rodents and humans, classical brown adipocytes originate from the mesoderm during embryonic development and share a common developmental origin with myocytes that form skeletal muscle cells (23-25). During mouse embryonic development at E9.5-E14.5, lineage-tracing studies reveal a population of mesenchymal stem cells that reside in the dermomyotome and express certain specific markers, including En1, Pax3, Pax7, Myf5, and Meox1, which can differentiate into brown adipocytes (23-28). Nearly all classical brown adipocytes in the interscapular BAT originate from the Myf5-expressing cell lineage, which are also precursors of the skeletal muscle lineage (24, 25, 29, 30). During adipogenesis, these cells undergo a transition marked by the loss of progenitor markers and have distinct markers characteristic of preadipocytes and mature brown adipocytes (16, 22). For instance, when brown APCs are differentiated into classical brown adipocytes, they express several brown-selective markers, such as Ucp1, Ppargc1a, Cidea, and Zic1 (31). BAT slowly continues to develop after infancy in mice, whereas the development of classical BAT halts in humans after birth (32). Postnatally, thermogenic adipocytes are maintained in BAT and WAT after the neonatal period in humans in response to environmental changes (33, 34). Importantly, adipocyte precursors are recruited to form new thermogenic adipocytes in both mice and humans (29), providing an exciting opportunity to enhance energy-dissipating potential and counteract obesity.

During development, beige adipocytes and white adipocytes arise from mesenchymal stem cells of mesoderm and a neural crest origin, leading to heterogeneity of lineages within different WAT depots (5). While the Meox1 gene is a dermomyotome marker, the Meox1-expressing mesenchymal stem cells also contribute to the formation of white adipocytes (26). In addition, Prx1-expressing, Wt1-expressing, and Myf5-negative progenitors contribute to the development of white adipocytes (25, 35, 36). In contrast, subpopulations of white adipocytes also originate from Myf5-expressing progenitors (25). Importantly, for the cellular origin of beige adipocytes, lineage-tracing studies indicate that they can develop through the de novo differentiation of APCs or the trans-differentiation of mature white adipocytes (37). Specifically, beige adipocytes are mainly derived from Myf5-negative, Meox1-expressing, and Prx1-expressing progenitors in mice (24-26, 28, 38). Similar to brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes also express common thermogenic markers such as Ucp1, Ppargc1a, and Cidea, as well as beige-selective markers, including Cd137, Tbx1, Tmem26, and Cited1 (31). Taken together, beige and white adipocytes originate from common progenitors under distinct developmental or environmental conditions, providing an important strategy to enhance thermogenic adipocytes in WAT.

2.2. Identification of Distinct APCs in Thermogenic Adipose Tissues

APCs have unique markers that distinguish them from each other and other stromal cells in adipose tissue. APCs are identified and isolated using their unique markers, and their roles are characterized by adipose tissue plasticity, remodeling, and metabolic regulation. APCs capable of developing into thermogenic adipocytes can be classified into two distinct lineages: mesenchymal stem cell-derived APCs and mural cell-derived APCs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distinct Lineage of Adipose Progenitor Origins of Thermogenic Adipocytes.

The schematic illustrates the distinct lineage of adipocyte cells that give rise to thermogenic adipocytes. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived APCs and mural cell-derived APCs contribute to the development of thermogenic adipocytes, including brown and beige adipocytes. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived APCs classically originate from mesenchymal stem cells, while mural cell-derived APCs originate from pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. Each APC lineage is accompanied by with defined lineage markers and cell surface and transcriptional markers displayed beneath their respective labels. Positive markers (+) are indicated by “+,” while negative markers are noted with “−.” αSMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; CD29, CD34 and CD81, the cluster of differentiation 29, 34 and 81; Pdgfrα/β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha/beta; Myh11, myosin heavy chain 11; Trpv1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1; Dpp4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; Pparγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; Cebpα, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha; Gata6, GATA-binding protein 6; Adipoq, adiponectin; Ucp1, uncoupling protein 1; Ppargc1a, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha. Created in BioRender. Tseng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/taa35zt.

2.2.1. APCs Originate from Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Non-hematopoietic and non-endothelial adult mesenchymal stem cells are an essential source of the APC pool in the adipose tissue niche (16, 21, 39). To understand the mechanism and cellular hierarchy of each progenitor in adipose tissue, APCs are selectively isolated based on surface marker expression. Using the cell surface markers (e.g., CD29, CD34), APCs isolated from BAT and WAT depots demonstrated adipogenic potential in vitro and in vivo, suggesting their potential to make newly formed thermogenic adipocytes (40-42). Lineage-tracing studies reveal that PDGFRα-expressing APCs are commonly found in WAT and BAT, and these cells give rise to white, beige, and brown adipocytes (43, 44). Another subset of APCs is SCA-1-expressing APCs, which have unique molecular expression signatures and distinct adipogenic capacities (41). Specifically, SCA-1-expressing APCs isolated from BAT are committed to forming brown adipocytes (41). SCA-1-expressing cells derived from skeletal muscle and WAT also possess an inducible potential to develop beige adipocytes in response to BMP7 treatment, highlighting their potential in thermogenic adipocyte development (41).

CD34 and PDGFRα-expressing progenitors are also present in humans’ deep and subcutaneous neck adipose tissues (45). In vitro, the CD29-expressing progenitors derived from human deep-neck adipose tissue can differentiate into brown adipocytes, whereas the subcutaneous neck progenitors usually turn into white adipocytes (42, 45). Additionally, human supraclavicular and perirenal tissues contain precursor cells that can differentiate into thermogenic adipocytes, indicating the existence of multiple potential sources of APCs for thermogenic adipocytes (34, 46). Another APC population identified in both mouse and human white adipose tissues is the DPP4-expressing progenitors (also known as CD26-expressing cells), which derive from the reticulum interstitium, a network of collagen and elastin fibers surrounding and partitioning WAT depots (47). These cells are proliferative and multipotent (47). Notably, the DPP4-expressing APCs in inguinal WAT are responsive to acute cold exposure and couple adrenergic signaling to induce IL-33 secretion, which enhances beige adipocyte formation (48). Jun et al. and Rao et al. recently identified GATA6-expressing APCs involved in developing brown adipocytes in both mouse and human models using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analyses (49, 50).

2.2.2. APCs Originate from Mural Cells

Mural cells refer to a group of cells that includes pericytes and vascular smooth muscle (VSM) covering the abluminal surface of blood vessels (51). Specifically, αSMA-expressing APCs, as adult progenitors, originate from perivascular smooth muscle actin and differentiate into thermogenic adipocytes in response to cold exposure (18, 52). PDGFRβ is a marker of APCs derived from pericytes located in a perivascular niche around blood vessels. PDGFRβ-expressing APCs contribute to adipose remodeling in obese or cold conditions (53, 54). Lineage-tracing studies demonstrated that PDGFRα-expressing APCs alone or with PDGFRβ-expressing progenitors produce thermogenic adipocytes during basal turnover and cold-induced adipogenesis in WAT. In contrast, PDGFRβ-expressing APCs alone cannot achieve it (55, 56). Sun et al. also report that PDGFRα-expressing APCs are the primary contributors to adipogenesis in both embryonic development and adulthood, whereas PDGFRβ-expressing APCs contribute to adipocytes during postnatal growth, but not in adult mice under normal conditions (57). Notably, mosaic deletion of PDGFRα or PDGFRβ in APCs promotes the differentiation of thermogenic adipocytes, while constitutive activation of PDGFRα inhibits white and beige adipocyte development (57, 58). These findings suggest their cell-autonomous inhibitory role in thermogenic adipocyte development.

MYH11-expressing APCs derived from a smooth muscle-like origin contribute to beige adipocytes but do not differentiate into classical brown adipocytes (59). In humans, in vitro studies show that APCs derived from capillary networks can proliferate and differentiate into beige adipocytes, indicating a role of capillary-associated APCs in forming thermogenic adipocytes (60). Recently, scRNA-seq analyses identified new cell populations that are CD81-expressing and TRPV1-expressing APCs derived from VSM (61, 62). CD81-expressing APCs are involved only in developing beige adipocytes, whereas TRPV1-expressing APCs form thermogenic adipocytes in both BAT and WAT (61, 62). These findings suggest that APCs are the primary source of new adipocytes. Therefore, it is vital to identify APCs and understand the mechanisms that promote differentiation into thermogenic adipocytes to improve metabolic benefits.

2.3. Transcriptional Regulation of Adipogenesis

Understanding the precise signaling cascades and molecular activators involved in differentiating APCs into thermogenic adipocytes is essential to understanding how thermogenesis and metabolic regulation are controlled throughout life. Adipocyte development includes two distinct stages: the initial lineage commitment of precursor cells and preadipocyte differentiation into fully mature adipocytes. This section provides an overview of the key molecular regulators that initiate the transcriptional program during adipogenesis.

Adipogenesis is regulated by several key transcription factors, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) (63-65). Hedgehog signaling also suppresses adipogenesis, while bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) enhances commitment to the adipogenic lineage, particularly for white adipocytes. Suppression of Wnt signaling is necessary for adipogenesis, as active Wnt signaling promotes osteogenesis and inhibits PPARγ activation (65). PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16) plays a pivotal role in driving the differentiation of brown adipocytes from APCs (41, 66, 67). Ewing sarcoma (EWS) and Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1) support BAT development by activating the expression of BMP7, which is a key inducer of embryonic BAT formation (68, 69). TATA-box binding protein associated factor 7 like (TAF7L) works with PPARγ and PRDM16 to promote brown adipogenesis (68, 70, 71). Loss of TAF7L in preadipocytes increases muscle gene expression in BAT and prevents the differentiation into new adipocytes (70). In addition, zinc finger protein 423 (ZFP423) is a marker of preadipocyte commitment cells originating from perivascular origins within mouse WAT, which promote white adipocyte differentiation and suppress thermogenic adipocyte development (72).

Early B cell factor 2 (EBF2), which is highly enriched in brown preadipocytes, regulates brown adipocyte differentiation by suppressing muscle-specific factors, myogenic differentiation (MYOD), and myogenin (71, 73). In addition, nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group F member 6 (NR2F6) is a transcription factor and regulates PPARγ expression (74). It is predominantly expressed in brown preadipocytes, with its levels increasing during the early stages of brown adipocyte differentiation and subsequently declining in mature adipocytes. A deficiency of NR2F6 in preadipocytes disrupts brown adipocyte differentiation, whereas this deletion does not alter white adipocyte differentiation (74). Recent studies report GATA6 as another key transcriptional factor that promotes brown adipocyte differentiation from the precursors in mice and humans (49, 50). Many other transcriptional factors and coregulators regulate brown adipocyte differentiation. These transcription factors include ZFP516, Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), placenta-specific 8 (PLAC8), interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4), zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 16 (ZBTB16), estrogen-related receptor α/γ (ERRα/γ), PPARα, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), early growth response 2 (Krox20/Egr2), sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a (STAT5a) (63, 71, 75, 76). The coactivators comprise PGC-1α and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs).

Epigenetic factors also play essential roles in regulating adipogenesis by targeting histone methylation/demethylation, histone acetylation/deacetylation, chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, and microRNAs (63, 75, 76). For example, deleting the histone methyltransferase EHMT1, a core component of the PRDM16 complex, impairs brown adipocyte differentiation and triggers ectopic expression of muscle genes (77). PRDM16 requires EHMT1 to silence myogenic programs and activate brown-adipocyte genes, although its loss in Myf5-expressing progenitors does not block embryonic BAT development, suggesting alternative factors like PRDM3 can compensate (71, 77). GCN5/PCAF, as histone acetyltransferases, also positively promote brown adipogenesis by regulating PPARγ and PRDM16 (78).

3. Impact of Environmental Factors and Physiological Cues on APC Activation

Adipose tissue exhibits remarkable plasticity and dynamically adjusts its size, cellular composition, and function in response to environmental factors and physiological cues (79). This dynamic adaptability is regulated by intricate molecular mechanisms that integrate physiological cues, genetic variations, and external factors to maintain thermogenesis and metabolism (79, 80). These ongoing changes contribute to inter-individual and intra-individual variations in adipose tissue, influencing plasticity and shaping systemic metabolism (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Drivers of Adipose Tissue Heterogeneity.

This schema illustrates how the interplay among environmental factors, physiological cues, and genetic variations contributes to adipose tissue plasticity and systemic metabolism through epigenetic, transcriptional, and translational alterations. Epigenetic alterations regulate inter-individual and intra-individual variations in adipose tissue, affecting cellular composition, function, and metabolic adaptability. Consequently, these drivers contribute to systemic metabolic homeostasis and influence individual responses to metabolic challenges. Created in BioRender. Tseng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/b82i108.

The contribution of APCs to adiposity and metabolic homeostasis can be manipulated by external and physiological factors such as diet, cold, exercise, sex, and aging. The environmental factors include high-fat diet (HFD), housing temperature, and exercise, while hormones, sex, and aging control the APC population and their activation. Figure 4 highlights positive and negative regulators that impact the proliferation and differentiation of APCs toward thermogenic adipocytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Positive and Negative Regulators in APC Proliferation and Differentiation into Thermogenic Adipocytes.

This figure illustrates the positive and negative regulators that influence APC proliferation and their differentiation into thermogenic adipocytes. Positive regulators, such as estrogen, thyroid hormones, insulin, cold exposure, and exercise, facilitate the proliferation and differentiation of APCs into thermogenic adipocytes, leading to hyperplasia (or an increase in the number of adipocyte cells). In contrast, negative regulators such as a high-fat diet (HFD), aging, thermoneutrality (TN), testosterone, and glucocorticoids (GCs) inhibit this process, favoring hypertrophy (or increasing adipocyte cell size), which is associated with metabolic dysregulation. Created in BioRender. Tseng, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/w79h735

3.1. External Cues

3.1.1. HFD

In BAT, HFD reduces APCs (Lin−:CD34+:CD29+: SCA-1+:CD24+) compared to a chow diet. Diet has differential impacts on APC populations in different WAT (81). Joe et al. also report that the APCs increase in subcutaneous WAT but remain unchanged in visceral WAT in response to an HFD (82). Recently, single-cell mass cytometry analysis also revealed that HFD promotes changes in APC populations for early response to dietary changes, indicating their function in regulating adipose tissue remodeling (83). For instance, HFD increases the CD9high and reduces the CD9low subsets of PDGFRα-expressing APCs in WAT. These changes in APC subsets result in reduced adipogenic and increased fibrogenic potential, leading to impaired adipogenesis and pathological remodeling, with similar findings observed in human obesity (83, 84). Without β3-adrenergic stimulation, PDGFRα-expressing APCs are involved in hyperplasia in WAT in response to HFD feeding, indicating their bipotential roles in metabolic regulation (44). Moreover, lineage tracing studies show that a subset of APCs differentiates into new white adipocytes in response to HFD in mice, resulting in WAT expansion and the development of obesity (85). Therefore, targeting APCs is crucial for reducing obesity and promoting adipocyte renewal to combat this disease. Collectively, these findings suggest a potential link between dietary influences and APC activation, and HFD differentially regulates distinct subtypes of APCs that give rise to white adipocytes, which may reduce the formation of thermogenic adipocytes.

3.1.2. Cold Challenge

Cold-induced thermogenesis in BAT depends on intact sympathetic nervous system activity, which leads to the release of norepinephrine at nerve terminals (86). Norepinephrine binds to β-adrenergic receptors in brown adipocytes and triggers intracellular signaling via the cAMP-PKA pathway to increase thermogenesis (86-88). In addition to classical β-adrenergic pathways, GPR3, as a constitutively active receptor in BAT, increases thermogenesis through ligand-independent Gs-coupling and cAMP production, with its expression induced by lipolysis and cold, a nonconical mechanism of brown adipocyte activation (89).

Upon cold-induction or pharmacological activation of β3-adrenergic receptors, PDGFRα-expressing APCs in WAT and BAT proliferate and differentiate into brown and beige adipocytes (44, 90-92). The surgical denervation markedly diminished the effect on BAT under these conditions (92). Conventionally, APCs are recognized to express β1-adrenergic receptor, not β3-adrenergic receptor, and their activation in these cells contributes to the development of cold-induced thermogenic adipocytes (93, 94). β3-adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling has minimal impact on the recruitment of the PDGFRβ-expressing APCs to differentiate into brown and beige adipocytes (92). In contrast to previous findings, Burl et al. recently demonstrated that β3-adrenergic signaling in mature brown adipocytes indirectly drives proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells into new brown adipocytes, rather than through direct β1-adrenergic signaling in APCs (95). Activation of β3-adrenergic signaling triggers the recruitment of specific immune cells, including lipid-handling macrophages and dendritic cells, which remodel the adipose niche and interact with progenitor cells to enhance their differentiation (95). These findings suggest a critical crosstalk among brown adipocytes, immune cells, and progenitors to increase thermogenic capacity during cold exposure.

In response to acute or short-term cold exposure, PDGFRα and SCA-1-expressing APCs rapidly contribute to the development of new thermogenic adipocytes (92). By contrast, prolonged cold exposure also recruits the proliferation and differentiation of VSM into thermogenic adipocytes in rodents (18, 59, 62). αSMA-, CD81-, and MHY11-expressing APCs from mural cells are another essential source for cold-induced thermogenesis (18, 59). For instance, seven days of cold exposure significantly increases the proliferation and differentiation of VSM-derived TRPV1-expressing APCs into highly thermogenic adipocytes in BAT (62). Interestingly, it is shown that PDGFRβ-expressing APCs are not contributors to beige adipocytes at the initial cold exposure; in contrast, they can be recruited and give rise to beige adipocytes for long-term cold exposure (54). In addition, the PDGFRβ signaling pathway is a negative regulator of thermogenic adipocyte differentiation, and its deletion or inhibition increases newly formed beige adipocytes in male mice under cold (96). These findings highlight different subtypes of APCs that exhibit varying responses to β-adrenergic stimulation, and cold exposure is a positive regulator of thermogenic adipocyte development by targeting these APCs. Sympathetic nerves in adipose tissues also secrete neuropeptide Y (NPY) in response to cold. This NPY metabolite enhances the proliferation and differentiation capacity of its Y1 receptor (NPY1R)-expressing mural cells, which give rise to thermogenic adipocytes in both WAT and BAT (97, 98). Overall, these studies highlight a neuro-adipose axis that is important to develop thermogenic adipocytes and offer valuable insights into how thermogenic adipocytes can be directly enhanced for the treatment of obesity and metabolic diseases.

3.1.3. Exercise

Exercise stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, thereby enhancing the proliferation and differentiation of brown preadipocytes in response to cold exposure (99). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis reveals that exercise enhances SCA-1-expressing APCs in BAT tissue compared to sedentary mice (100). Preadipocytes isolated from the BAT-SVFs in exercised mice also exhibit a more significant differentiation potential and increased expression of UCP1 after differentiation (100). Additionally, exercise reverses obesity-induced CD142-expressing APCs, a subset of DPP4-expressing progenitors, which inhibits adipocyte differentiation and contributes to fibrosis. Exercise also suppresses ECM remodeling in APCs, preventing excessive fibrosis and enhancing adipose tissue plasticity (101). Exercise is another key regulator of APC activation, promoting thermogenic adipocyte differentiation and inducing beneficial adaptations that foster a healthy adipose tissue environment.

3.1.4. Pollutants

Environmental pollutants impair thermogenic adipocyte function and development through multiple mechanisms. Functionally, the pollutants dysregulate glucose homeostasis and mitochondrial function in WAT and BAT, leading to the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes (102-104). In BAT, pollutants reduce the expression of thermogenic genes (e.g., Ucp1, Ppargc1a, and Prdm16) while increasing inflammation, resulting in reduced thermogenesis (103, 105). In mice, perinatal exposure to environmental pollutants also interrupts the development of sympathetic innervation to BAT, thereby leading to impaired thermogenic adipocyte development and function (106). In addition, pollutants negatively regulate APC proliferation and differentiation in humans, contributing to reduced adipogenesis (107). Specifically, certain pollutants disrupt transcriptional networks for adipogenesis and browning of white adipocytes (105). Importantly, APCs are more sensitive to contaminants than mature adipocytes (105), suggesting the detrimental impact of pollutants on APCs for thermogenic adipocyte formation. Furthermore, microplastics as environmental pollutants accumulate in adipose tissues, triggering early cellular senescence, increasing inflammation, and impairing brown and white adipocyte differentiation in vitro and in vivo (108). Collectively, these studies indicate the impact of environmental pollutants on thermogenic adipocyte development and function, with long-term pathological consequences for obesity and metabolic diseases.

3.2. Physiological Factors

3.2.1. Hormones

Several hormones trigger signaling pathways that control the transformation of preadipocytes into thermogenic adipocytes. The key players in this process are insulin, thyroid, and glucocorticoid hormones.

Insulin and insulin receptors (IR) are key components in regulating insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis in adipose tissue (109). Insulin is essential in controlling the development of mature adipocytes from APCs during embryonic and adult stages (110). Specific deletion of IR in Myf5-expressing lineage in mice disrupts interscapular BAT formation due to decreased adipogenesis in preadipocytes, while it does not impair muscle development (111). Interestingly, beige adipocytes in subcutaneous WAT compensate for the lack of BAT function for maintaining thermoregulation (111). In addition, adult APCs reside in the adipose vascular niche and resemble specialized mural cells, contributing to the regulation of adipose tissue homeostasis (52). Deletion of IR in αSMA-expressing APC derived from mural cells does not change the formation of white or cold-induced thermogenic adipocytes (112). In contrast, PPARγ-expressing preadipocytes require IR to form entirely white adipocytes, and deficiency of IR in preadipocytes leads to lipodystrophy (112).

Thyroid hormone is a thermogenic hormone that improves metabolic response in BAT either directly or via the sympathetic nervous system (113, 114). Prolonged treatment of triiodothyronine (the active form of thyroid hormone T3) enhances APC proliferation, resulting in increased thermogenic capacity and hyperplasia in BAT (115). Mechanistically, this effect is primarily mediated by thyroid receptor α (TRα) in APCs derived from the Myf5-expressing lineage (115). A deficiency of thyroid hormone markedly reduces the recruitment of beige adipocytes via ZFP423 transcription factor inactivation in visceral WAT but not in inguinal WAT and BAT (116). Lastly, hypothyroidism is associated with cold intolerance and weight gain in humans (117). Recent studies have shown that hypothyroidism reduces the number of APCs in BAT compared to euthyroid control mice, indicating the role of thyroid hormone in the development of thermogenic adipocytes (115).

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are steroid hormones that act as anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive by binding to the glucocorticoid receptors (118). GCs are essential regulators of metabolic health by targeting key pathways in adipose tissue, such as increased adipogenesis and de novo lipogenesis, enhanced lipid storage, and impaired glucose uptake (118-121). Studies have shown that excess GCs reduce energy expenditure in brown adipocytes and inhibit beiging in white adipocytes, with increased WAT mass, resulting in reduced thermogenic capacity (122-124). Interestingly, while excess GCs decrease BAT thermogenesis and UCP1 expression in mice, GCs can acutely increase UCP-1 expression and BAT activity in humans (125), highlighting the species-specific effects of glucocorticoids. This study can be explained by its regulatory role in APCs. In preadipocytes, activation of GR enhances the recruitment of APCs by upregulating the expression of adipogenic genes, such as C/EBPα and PPARγ, which increase newly formed adipocytes in vitro (120, 126).

3.2.2. Metabolites Derived from Mature Adipocytes

Mature adipocytes modulate adipocyte precursor cells through paracrine signaling to suppress fibrosis and enhance thermogenic adipocyte development. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated that PRDM16 drives fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in adipocytes, leading to the production of β-hydroxybutyrate that inhibits fibrosis in PDGFRα+ APCs and promotes their differentiation into beige adipocytes (127). Notably, aging reduces this metabolite signaling in APCs, resulting in impaired age-related beige adipocyte remodeling. However, dietary supplementation with β-hydroxybutyrate decreases adipose tissue fibrosis and restores beige adipocyte formation in aged mice (127). Another study also highlights linoleic acid, a metabolite derived from lipolysis, as an essential modulator of beige adipocyte development. In both mice and humans, cold exposure stimulates lipolysis in WAT, releasing linoleic acid, which promotes the proliferation and differentiation of CD81-, PDGFRα-, and SCA1-expressing APCs into beige adipocytes (128). Taken together, these studies reveal complementary metabolic and signaling pathways through metabolites that control APC activation and beige adipocyte development in response to diverse physiological and environmental stimuli.

3.2.3. Sex

In humans, there are pronounced differences in adipose tissue composition and distribution between males and females. For instance, an average male body contains 15% fat, while the female body contains ~25% fat (129). These differences in fat percentage emerge as early as late gestation (130). In vitro studies have also indicated that estrogen stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of human preadipocytes (131, 132), whereas androgen inhibits adipocyte differentiation in human preadipocytes in both sexes (133). Sex differently influences adipose tissue location in the body, which is associated with metabolic health in both men and women (134). scRNA-seq has recently shown that the proportions of APCs differ between males and females in mouse adipose tissue after HFD (12). These data suggest that sex hormones may regulate mesenchymal cell fate decisions towards APCs. In addition, APCs exhibit sexually dimorphic roles; in particular, male APCs have more significant adipogenic potential in perigonadal WAT compared to female APCs, which implies that males are more prone to visceral fat accumulation and may have a higher metabolic disease risk compared to females (135). These findings indicate the sex-associated difference in APC function within adipose tissue depots, which impacts their responses to metabolic changes such as diet.

3.2.4. Aging

In rodents and humans, the activity of thermogenic adipose tissue decreases with age, predisposing individuals to the development of metabolic diseases (90, 136-138). Inducing the senescence pathway in young APCs inhibits their potential to differentiate into cold-induced beige adipocytes. However, reversing cellular senescence by targeting the p38/MAPK-p16ln4a pathway in aged mice or human APCs enhances cold-induced beige adipogenesis and improves glucose sensitivity (137). In mice, scRNA-seq from the SVF of inguinal WAT revealed that the number of mesenchymal stem cells and APCs decreased with aging, leading to a decrease in newly formed adipocytes (139). Holman et al. show that aging also blocks the differentiation of PDGFRα-expressing APCs into beige adipocytes and activates the lipogenic gene program in adipocytes (90). In addition, PDGFRβ expression in APCs is increased with aging, which dysregulates APC function and impairs beige adipocyte development (96).

In contrast, beige adipocyte development is restored and improved with the deletion of PDGFRβ in WAT in aged male mice (96). Mechanistically, aging increases telomere attrition and senescence in APCs. In mice, adipocytes initially undergo browning when telomerase is inactivated in APCs. However, this inactivation in the long term leads to the loss of the APCs’ ability to proliferate and differentiate into new adipocytes, predisposing to the development of metabolic diseases (140). This indicates their potential as a pharmacological target to prevent aging-related metabolic diseases. Furthermore, adipocytes originating from Prx1-expressing APCs are present from birth and exhibit the capacity to differentiate into thermogenic adipocytes. Importantly, they persist with age and maintain their thermogenic profile (38).

4. Therapeutic Potential of Targeting APCs that Give Rise to Thermogenic Adipocytes in Metabolic Dysregulation

Given their essential role in metabolic regulation, targeting APCs presents novel therapeutic strategies to treat obesity and obesity-related complications. In adipogenesis, PDGFRβ signaling is the important negative regulator, and blocking PDGFRβ signaling increases newly formed beige adipocytes (96). Mechanistically, a recent study has demonstrated that Notch inhibition downregulates PDGFRβ signaling in PDGFRβ-expressing APCs, thereby promoting increased brown adipocyte differentiation (141). This inhibition of the Notch/PDGFRβ axis in PDGFRβ+ APCs protects mice from glucose and metabolic impairments induced by a high-fat, high-sucrose diet (141). Furthermore, inhibiting PDGFRα signaling promotes brown and beige adipogenesis, whereas its activation decreases adipocyte formation and increases fibrosis (58, 142). Du et al. report that suppression of PDGFRα signaling in APCs increases the number of brown adipocytes in mice, leading to an enlarged BAT mass (megaBAT) (142). This megaBAT enhances metabolic regulation and insulin sensitivity while protecting mice from HFD-induced obesity and diabetes (142). These studies indicate that pharmacological targeting of these signaling pathways can enhance APC proliferation and differentiation into thermogenic adipocytes. Daquinag et al. also developed a novel hunter-killer peptide, D-WAT, that decreases WAT growth, increases energy expenditure, and prevents obesity in mice (143). Mechanistically, D-WAT treatment selectively deletes white APCs in WATs but not in BAT, which increases the compensatory population of PDGFRα-expressing APCs that differentiate into thermogenic adipocytes (143).

Stem/progenitor cell-derived thermogenic adipocytes have the potential to serve as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of obesity and metabolic diseases. Human APCs originated from the capillary network and differentiated into beige adipocytes in vitro (60). When these adipocytes were implanted into chow-fed or HFD-fed mice, they improved systemic glucose tolerance (60). In addition, using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to overexpress UPC1 protein in human white preadipocytes, these cells exhibit human brown-like phenotypes (HUMBLE cells). Transplanting HUMBLE cells in mice increases energy expenditure and alleviates obesity-induced glucose intolerance (144). Wang et al. identified endothelin-3 as a key regulator of the browning of human white preadipocytes by activating the EDNRB-cAMP-ERK-dependent pathway (145). Injecting endothelin-3 into WAT in mice promotes the development of thermogenic adipocytes and improves whole-body glucose metabolism (145). Tsagkaraki also demonstrated that CRISPR-mediated deletion of the gene encoding corepressor Nrip1 in mouse and human progenitor cells increases thermogenic gene expression (146). Notably, implantation of this CRISPR-modified mouse or human adipocytes into HFD-fed mice reduced body weight and liver triglycerides and enhanced glucose tolerance (146). Additionally, deletion of Zfp423, a transcriptional repressor of thermogenesis, in embryonic or adult visceral white adipocyte precursors enhances thermogenic reprogramming and promotes the development of beige adipocytes in visceral WAT, thereby improving cold tolerance and reversing insulin resistance in obese mice (147). These studies suggest that targeting the positive or negative regulators in adipose precursors can influence the thermogenic potential of mature brown and beige adipocytes, which offers a potential approach to counteract metabolic diseases.

Dietary supplementation with β-hydroxybutyrate or linoleic acid also targets APCs to differentiate into beige adipocytes, which promise an alternative therapeutic strategy to increase thermogenic adipocytes (127, 128). Taken together, targeting APCs can serve as a potential therapeutic strategy to increase thermogenic adipocytes for treating obesity and obesity-induced metabolic disorders.

5. Challenges, Future Directions, and Conclusion

Despite the remarkable insights gained from the studies regarding APC subtypes and their potential to form thermogenic adipocytes in metabolic health, several limitations remain. The diverse APCs in thermogenic adipose tissues were primarily identified in rodents; however, their interpretation and translational relevance in humans remain to be elucidated. Defining APC subtypes through single-cell, spatial transcriptomic, and epigenomic analyses will also help identify the origin of thermogenic adipocytes from other adipose stem cells and provide insights into the fate determination and differentiation of APCs to thermogenic adipocytes in humans. These studies will enhance the understanding of the functional significance of APCs in human metabolic health and energy homeostasis.

Environmental factors and physiological cues (e.g., genetics, diet, housing temperature, and exercise) regulate the activation of APCs, which in turn influence the plasticity of thermogenic adipose tissue. However, the molecular mechanisms governing their differentiation into thermogenic adipocytes versus other lineages remain unclear. Future studies integrating metabolic and proteomic profiling with functions may reveal critical pathways that drive APC-derived thermogenic adipocytes.

Another limitation in studying APCs is the limited understanding of intercellular interactions within the adipose niche. It is unclear exactly how the intercellular interactions among APCs, mature adipocytes, immune cells, extracellular matrix components, and systemic metabolic cues regulate the development of thermogenic adipocytes. Advanced in vivo models, such as humanized adipose tissues in mice, may contribute to validating the physiological relevance of the recent findings of APC physiology. Furthermore, the variability in experimental models, including differences in genetic mouse models, animal housing conditions (e.g., diet, temperature, facility properties), and environmental factors, can affect the studies focusing on APC activation in different adipose tissue depots. Future studies should focus on identifying the key regulatory mechanisms that determine the metabolic phenotypes of thermogenic adipocytes versus white adipocytes in different adipose tissue depots.

Therapeutic interventions targeting APCs show promise for improving metabolic health (144-146); however, their long-term efficacy and safety will need to be validated in vivo and through clinical studies. In the future, optimizing stem/progenitor cell-based therapies (e.g., thermogenic adipocyte transplantation and gene-editing strategies in APCs) and pharmacological therapeutics may enable the selective activation of APC differentiation for thermogenesis in obesity and metabolic dysregulation. This selective target may also minimize their off-target effects for long-term use. Despite the impact of sex and aging on APC subtypes and activation, future studies will count these factors as personalized and effective interventions.

In conclusion, APCs are diverse and essential to forming new thermogenic adipocytes, which maintain adipose tissue plasticity and metabolic health. Thus, understanding APC biology in adipose tissue function and its potential in metabolic health is a promising therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of metabolic diseases.

Grants

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DK133528, R01DK132469, and R01DK102898 (to Y.-H. T.) and P30DK036836 (to Joslin Diabetes Center’s Diabetes Research Center). C.S. was supported by the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (https://doi.org/10.58275/AHA.25POST1378609.pc.gr.227421)

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that the manuscript was written without any commercial or financial relationships that could be seen as a potential conflict of interest. Y.-H.T. is an inventor on Joslin Diabetes Center patents for the use of BMP7 and 12,13-diHOME.

9. References

- 1.Singh R, Barrios A, Dirakvand G, Pervin S. Human Brown Adipose Tissue and Metabolic Health: Potential for Therapeutic Avenues. Cells. 2021;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn DE, Bergman BC. Keeping It Local in Metabolic Disease: Adipose Tissue Paracrine Signaling and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes. 2022;71(4):599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda K, Maretich P, Kajimura S. The Common and Distinct Features of Brown and Beige Adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(3):191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghesmati Z, Rashid M, Fayezi S, Gieseler F, Alizadeh E, Darabi M. An update on the secretory functions of brown, white, and beige adipose tissue: Towards therapeutic applications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2024;25(2):279–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamsi F, Wang CH, Tseng YH. The evolving view of thermogenic adipocytes - ontogeny, niche and function. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(12):726–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1252–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becher T, Palanisamy S, Kramer DJ, Eljalby M, Marx SJ, Wibmer AG, et al. Brown adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic health. Nat Med. 2021;27(1):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wibmer AG, Becher T, Eljalby M, Crane A, Andrieu PC, Jiang CS, et al. Brown adipose tissue is associated with healthier body fat distribution and metabolic benefits independent of regional adiposity. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(7):100332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Mara AE, Johnson JW, Linderman JD, Brychta RJ, McGehee S, Fletcher LA, et al. Chronic mirabegron treatment increases human brown fat, HDL cholesterol, and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2209–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herz CT, Kulterer OC, Prager M, Schmoltzer C, Langer FB, Prager G, et al. Active Brown Adipose Tissue is Associated With a Healthier Metabolic Phenotype in Obesity. Diabetes. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellers AJ, van Beek SMM, Hashim D, Baak R, Pallubinsky H, Moonen-Kornips E, et al. Cold acclimation with shivering improves metabolic health in adults with overweight or obesity. Nat Metab. 2024;6(12):2246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emont MP, Jacobs C, Essene AL, Pant D, Tenen D, Colleluori G, et al. A single-cell atlas of human and mouse white adipose tissue. Nature. 2022;603(7903):926–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijay J, Gauthier MF, Biswell RL, Louiselle DA, Johnston JJ, Cheung WA, et al. Single-cell analysis of human adipose tissue identifies depot and disease specific cell types. Nat Metab. 2020;2(1):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue S, Lee D, Berry DC. Thermogenic adipose tissue in energy regulation and metabolic health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1150059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecoutre S, Rebiere C, Maqdasy S, Lambert M, Dussaud S, Abatan JB, et al. Enhancing adipose tissue plasticity: progenitor cell roles in metabolic health. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry R, Jeffery E, Rodeheffer MS. Weighing in on adipocyte precursors. Cell Metab. 2014;19(1):8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun K, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2094–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry DC, Jiang Y, Graff JM. Emerging Roles of Adipose Progenitor Cells in Tissue Development, Homeostasis, Expansion and Thermogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(8):574–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billon N, Iannarelli P, Monteiro MC, Glavieux-Pardanaud C, Richardson WD, Kessaris N, et al. The generation of adipocytes by the neural crest. Development. 2007;134(12):2283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takashima Y, Era T, Nakao K, Kondo S, Kasuga M, Smith AG, et al. Neuroepithelial cells supply an initial transient wave of MSC differentiation. Cell. 2007;129(7):1377–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, Jiang M, Cao G, Yang Q, et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(7):1128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye J, Gao C, Liang Y, Hou Z, Shi Y, Wang Y. Correction: Characteristic and fate determination of adipose precursors during adipose tissue remodeling. Cell Regen. 2023;12(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Kissig M, Rajakumari S, Huang L, Lim HW, Won KJ, et al. Ebf2 is a selective marker of brown and beige adipogenic precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(40):14466–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454(7207):961–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Guertin DA. Adipocytes arise from multiple lineages that are heterogeneously and dynamically distributed. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebo ZL, Jeffery E, Holtrup B, Rodeheffer MS. A mesodermal fate map for adipose tissue. Development. 2018;145(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atit R, Sgaier SK, Mohamed OA, Taketo MM, Dufort D, Joyner AL, et al. Beta-catenin activation is necessary and sufficient to specify the dorsal dermal fate in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2006;296(1):164–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timmons JA, Wennmalm K, Larsson O, Walden TB, Lassmann T, Petrovic N, et al. Myogenic gene expression signature establishes that brown and white adipocytes originate from distinct cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4401–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz TJ, Tseng YH. Brown adipose tissue: development, metabolism and beyond. Biochem J. 2013;453(2):167–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz TJ, Huang P, Huang TL, Xue R, McDougall LE, Townsend KL, et al. Brown-fat paucity due to impaired BMP signalling induces compensatory browning of white fat. Nature. 2013;495(7441):379–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidossis L, Kajimura S. Brown and beige fat in humans: thermogenic adipocytes that control energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):478–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Gao M, Zhu F, Li X, Yang Y, Yan Q, et al. METTL3 is essential for postnatal development of brown adipose tissue and energy expenditure in mice. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jespersen NZ, Larsen TJ, Peijs L, Daugaard S, Homoe P, Loft A, et al. A classical brown adipose tissue mRNA signature partly overlaps with brite in the supraclavicular region of adult humans. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Hung CM, Guertin DA. Emerging Complexities in Adipocyte Origins and Identity. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(5):313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chau YY, Bandiera R, Serrels A, Martinez-Estrada OM, Qing W, Lee M, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous fat have different origins and evidence supports a mesothelial source. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(4):367–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shao M, Wang QA, Song A, Vishvanath L, Busbuso NC, Scherer PE, et al. Cellular Origins of Beige Fat Cells Revisited. Diabetes. 2019;68(10):1874–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Feldman BJ. Characterization and lineage tracing of a mouse adipose depot reveal properties conserved with human supraclavicular brown adipose tissue. Stem Cell Reports. 2025:102509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittenger MF, Discher DE, Peault BM, Phinney DG, Hare JM, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen Med. 2019;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K, Friedman JM. Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell. 2008;135(2):240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Tran TT, Zhang H, Townsend KL, Shadrach JL, et al. Identification of inducible brown adipocyte progenitors residing in skeletal muscle and white fat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(1):143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue R, Lynes MD, Dreyfuss JM, Shamsi F, Schulz TJ, Zhang H, et al. Clonal analyses and gene profiling identify genetic biomarkers of the thermogenic potential of human brown and white preadipocytes. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):760–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry R, Rodeheffer MS. Characterization of the adipocyte cellular lineage in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(3):302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee YH, Granneman JG. Seeking the source of adipocytes in adult white adipose tissues. Adipocyte. 2012;1(4):230–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tews D, Schwar V, Scheithauer M, Weber T, Fromme T, Klingenspor M, et al. Comparative gene array analysis of progenitor cells from human paired deep neck and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;395(1-2):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jespersen NZ, Feizi A, Andersen ES, Heywood S, Hattel HB, Daugaard S, et al. Heterogeneity in the perirenal region of humans suggests presence of dormant brown adipose tissue that contains brown fat precursor cells. Mol Metab. 2019;24:30–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merrick D, Sakers A, Irgebay Z, Okada C, Calvert C, Morley MP, et al. Identification of a mesenchymal progenitor cell hierarchy in adipose tissue. Science. 2019;364(6438). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shan B, Shao M, Zhang Q, An YA, Vishvanath L, Gupta RK. Cold-responsive adipocyte progenitors couple adrenergic signaling to immune cell activation to promote beige adipocyte accrual. Genes Dev. 2021;35(19-20):1333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jun S, Angueira AR, Fein EC, Tan JME, Weller AH, Cheng L, et al. Control of murine brown adipocyte development by GATA6. Dev Cell. 2023;58(21):2195–205 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao J, Djeffal Y, Chal J, Marchiano F, Wang CH, Al Tanoury Z, et al. Reconstructing human brown fat developmental trajectory in vitro. Dev Cell. 2023;58(21):2359–75 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orlich MM, Dieguez-Hurtado R, Muehlfriedel R, Sothilingam V, Wolburg H, Oender CE, et al. Mural Cell SRF Controls Pericyte Migration, Vessel Patterning and Blood Flow. Circ Res. 2022;131(4):308–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y, Berry DC, Tang W, Graff JM. Independent stem cell lineages regulate adipose organogenesis and adipose homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;9(3):1007–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang W, Zeve D, Suh JM, Bosnakovski D, Kyba M, Hammer RE, et al. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322(5901):583–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vishvanath L, MacPherson KA, Hepler C, Wang QA, Shao M, Spurgin SB, et al. Pdgfrbeta+ Mural Preadipocytes Contribute to Adipocyte Hyperplasia Induced by High-Fat-Diet Feeding and Prolonged Cold Exposure in Adult Mice. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):350–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han X, Zhang Z, He L, Zhu H, Li Y, Pu W, et al. A suite of new Dre recombinase drivers markedly expands the ability to perform intersectional genetic targeting. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(6):1160–76 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao Z, Daquinag AC, Su F, Snyder B, Kolonin MG. PDGFRalpha/PDGFRbeta signaling balance modulates progenitor cell differentiation into white and beige adipocytes. Development. 2018;145(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun C, Sakashita H, Kim J, Tang Z, Upchurch GM, Yao L, et al. Mosaic Mutant Analysis Identifies PDGFRalpha/PDGFRbeta as Negative Regulators of Adipogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(5):707–21 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun C, Berry WL, Olson LE. PDGFRalpha controls the balance of stromal and adipogenic cells during adipose tissue organogenesis. Development. 2017;144(1):83–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Tsai L, Zeng X, Roh HC, Kong X, et al. A smooth muscle-like origin for beige adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2014;19(5):810–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Min SY, Kady J, Nam M, Rojas-Rodriguez R, Berkenwald A, Kim JH, et al. Human 'brite/beige' adipocytes develop from capillary networks, and their implantation improves metabolic homeostasis in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):312–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oguri Y, Shinoda K, Kim H, Alba DL, Bolus WR, Wang Q, et al. CD81 Controls Beige Fat Progenitor Cell Growth and Energy Balance via FAK Signaling. Cell. 2020;182(3):563–77 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shamsi F, Piper M, Ho LL, Huang TL, Gupta A, Streets A, et al. Vascular smooth muscle-derived Trpv1(+) progenitors are a source of cold-induced thermogenic adipocytes. Nat Metab. 2021;3(4):485–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim HY, Jang HJ, Muthamil S, Shin UC, Lyu JH, Kim SW, et al. Novel insights into regulators and functional modulators of adipogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;177:117073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, et al. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):20–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harms MJ, Ishibashi J, Wang W, Lim HW, Goyama S, Sato T, et al. Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19(4):593–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zamani N, Brown CW. Emerging roles for the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily in regulating adiposity and energy expenditure. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(3):387–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park JH, Kang HJ, Kang SI, Lee JE, Hur J, Ge K, et al. A multifunctional protein, EWS, is essential for early brown fat lineage determination. Dev Cell. 2013;26(4):393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Winnay JN, Taniguchi CM, et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454(7207):1000–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou H, Wan B, Grubisic I, Kaplan T, Tjian R. TAF7L modulates brown adipose tissue formation. Elife. 2014;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inagaki T, Sakai J, Kajimura S. Transcriptional and epigenetic control of brown and beige adipose cell fate and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(8):480–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gupta RK, Mepani RJ, Kleiner S, Lo JC, Khandekar MJ, Cohen P, et al. Zfp423 expression identifies committed preadipocytes and localizes to adipose endothelial and perivascular cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15(2):230–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shinoda K, Luijten IH, Hasegawa Y, Hong H, Sonne SB, Kim M, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of clonally derived adult human brown adipocytes. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):389–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou WY, Liu P, Xia YF, Shi YJ, Xu HY, Ding M, et al. NR2F6 is essential for brown adipocyte differentiation and systemic metabolic homeostasis. Mol Metab. 2024;81:101891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shapira SN, Seale P. Transcriptional Control of Brown and Beige Fat Development and Function. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee JE, Schmidt H, Lai B, Ge K. Transcriptional and Epigenomic Regulation of Adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohno H, Shinoda K, Ohyama K, Sharp LZ, Kajimura S. EHMT1 controls brown adipose cell fate and thermogenesis through the PRDM16 complex. Nature. 2013;504(7478):163–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jin Q, Wang C, Kuang X, Feng X, Sartorelli V, Ying H, et al. Gcn5 and PCAF regulate PPARgamma and Prdm16 expression to facilitate brown adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(19):3746–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kajimura S. The epigenetic regulation of adipose tissue plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nettore IC, Franchini F, Palatucci G, Macchia PE, Ungaro P. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Obesity. Biomedicines. 2021;9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu X, Liu C, Xu Z, Tzan K, Wang A, Rajagopalan S, et al. Altered adipocyte progenitor population and adipose-related gene profile in adipose tissue by long-term high-fat diet in mice. Life Sci. 2012;90(25-26):1001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Joe AW, Yi L, Even Y, Vogl AW, Rossi FM. Depot-specific differences in adipogenic progenitor abundance and proliferative response to high-fat diet. Stem Cells. 2009;27(10):2563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee JH, Ealey KN, Patel Y, Verma N, Thakkar N, Park SY, et al. Characterization of adipose depot-specific stromal cell populations by single-cell mass cytometry. iScience. 2022;25(4):104166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marcelin G, Ferreira A, Liu Y, Atlan M, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Pelloux V, et al. A PDGFRalpha-Mediated Switch toward CD9(high) Adipocyte Progenitors Controls Obesity-Induced Adipose Tissue Fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2017;25(3):673–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jeffery E, Church CD, Holtrup B, Colman L, Rodeheffer MS. Rapid depot-specific activation of adipocyte precursor cells at the onset of obesity. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(4):376–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 is essential for adaptive adrenergic nonshivering thermogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(2):E350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lowell BB, Flier JS. Brown adipose tissue, beta 3-adrenergic receptors, and obesity. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jung SM, Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Guertin DA. Brown Adipose Tissue Development and Metabolism. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2019;251:3–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sveidahl Johansen O, Ma T, Hansen JB, Markussen LK, Schreiber R, Reverte-Salisa L, et al. Lipolysis drives expression of the constitutively active receptor GPR3 to induce adipose thermogenesis. Cell. 2021;184(13):3502–18 e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holman CD, Sakers AP, Calhoun RP, Cheng L, Fein EC, Jacobs C, et al. Aging impairs cold-induced beige adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolic reprogramming. Elife. 2024;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, Scherer PE. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1338–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee YH, Petkova AP, Konkar AA, Granneman JG. Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J. 2015;29(1):286–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bronnikov G, Houstek J, Nedergaard J. Beta-adrenergic, cAMP-mediated stimulation of proliferation of brown fat cells in primary culture. Mediation via beta 1 but not via beta 3 adrenoceptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(3):2006–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bronnikov G, Bengtsson T, Kramarova L, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. beta1 to beta3 switch in control of cyclic adenosine monophosphate during brown adipocyte development explains distinct beta-adrenoceptor subtype mediation of proliferation and differentiation. Endocrinology. 1999;140(9):4185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burl RB, Rondini EA, Wei H, Pique-Regi R, Granneman JG. Deconstructing cold-induced brown adipocyte neogenesis in mice. Elife. 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Benvie AM, Lee D, Steiner BM, Xue S, Jiang Y, Berry DC. Age-dependent Pdgfrbeta signaling drives adipocyte progenitor dysfunction to alter the beige adipogenic niche in male mice. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu Y, Yao L, Gallo-Ferraz AL, Bombassaro B, Simoes MR, Abe I, et al. Sympathetic neuropeptide Y protects from obesity by sustaining thermogenic fat. Nature. 2024;634(8032):243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Foster MT, Bartness TJ. Sympathetic but not sensory denervation stimulates white adipocyte proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291(6):R1630–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Severinsen MCK, Scheele C, Pedersen BK. Exercise and browning of white adipose tissue - a translational perspective. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;52:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu X, Ying Z, Cai M, Xu Z, Li Y, Jiang SY, et al. Exercise ameliorates high-fat diet-induced metabolic and vascular dysfunction, and increases adipocyte progenitor cell population in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(5):R1115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang J, Vamvini M, Nigro P, Ho LL, Galani K, Alvarez M, et al. Single-cell dissection of the obesity-exercise axis in adipose-muscle tissues implies a critical role for mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Metab. 2022;34(10):1578–93 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu X, Liu C, Xu Z, Tzan K, Zhong M, Wang A, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate pollution induces insulin resistance and mitochondrial alteration in adipose tissue. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124(1):88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu Z, Xu X, Zhong M, Hotchkiss IP, Lewandowski RP, Wagner JG, et al. Ambient particulate air pollution induces oxidative stress and alterations of mitochondria and gene expression in brown and white adipose tissues. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Della Guardia L, Shin AC. White and brown adipose tissue functionality is impaired by fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) exposure. J Mol Med (Berl). 2022;100(5):665–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim MJ, Pelloux V, Guyot E, Tordjman J, Bui LC, Chevallier A, et al. Inflammatory pathway genes belong to major targets of persistent organic pollutants in adipose cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(4):508–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.vonderEmbse AN, Elmore SE, Jackson KB, Habecker BA, Manz KE, Pennell KD, et al. Developmental exposure to DDT or DDE alters sympathetic innervation of brown adipose in adult female mice. Environ Health. 2021;20(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Behan-Bush RM, Liszewski JN, Schrodt MV, Vats B, Li X, Lehmler HJ, et al. Toxicity Impacts on Human Adipose Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Acutely Exposed to Aroclor and Non-Aroclor Mixtures of Polychlorinated Biphenyl. Environ Sci Technol. 2023;57(4):1731–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moon H, Jeong D, Choi JW, Jeong S, Kim H, Song BW, et al. Microplastic exposure linked to accelerated aging and impaired adipogenesis in fat cells. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bluher M, Michael MD, Peroni OD, Ueki K, Carter N, Kahn BB, et al. Adipose tissue selective insulin receptor knockout protects against obesity and obesity-related glucose intolerance. Dev Cell. 2002;3(1):25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cignarelli A, Genchi VA, Perrini S, Natalicchio A, Laviola L, Giorgino F. Insulin and Insulin Receptors in Adipose Tissue Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lynes MD, Schulz TJ, Pan AJ, Tseng YH. Disruption of insulin signaling in Myf5-expressing progenitors leads to marked paucity of brown fat but normal muscle development. Endocrinology. 2015;156(5):1637–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yuan Y, Shi Z, Xiong S, Hu R, Song Q, Song Z, et al. Differential roles of insulin receptor in adipocyte progenitor cells in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2023;573:111968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Silva JE. Thermogenic mechanisms and their hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(2):435–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bianco AC, McAninch EA. The role of thyroid hormone and brown adipose tissue in energy homoeostasis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(3):250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu S, Shen S, Yan Y, Sun C, Lu Z, Feng H, et al. Triiodothyronine (T3) promotes brown fat hyperplasia via thyroid hormone receptor alpha mediated adipocyte progenitor cell proliferation. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roth L, Hoffmann A, Hagemann T, Wagner L, Strehlau C, Sheikh B, et al. Thyroid hormones are required for thermogenesis of beige adipocytes induced by Zfp423 inactivation. Cell Rep. 2024;43(12):114987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McAninch EA, Bianco AC. Thyroid hormone signaling in energy homeostasis and energy metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee MJ, Pramyothin P, Karastergiou K, Fried SK. Deconstructing the roles of glucocorticoids in adipose tissue biology and the development of central obesity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(3):473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li JX, Cummins CL. Fresh insights into glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus and new therapeutic directions. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(9):540–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ayala-Sumuano JT, Velez-delValle C, Beltran-Langarica A, Marsch-Moreno M, Hernandez-Mosqueira C, Kuri-Harcuch W. Glucocorticoid paradoxically recruits adipose progenitors and impairs lipid homeostasis and glucose transport in mature adipocytes. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bujalska IJ, Kumar S, Hewison M, Stewart PM. Differentiation of adipose stromal cells: the roles of glucocorticoids and 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Endocrinology. 1999;140(7):3188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Moriscot A, Rabelo R, Bianco AC. Corticosterone inhibits uncoupling protein gene expression in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(1 Pt 1):E81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Poggioli R, Ueta CB, Drigo RA, Castillo M, Fonseca TL, Bianco AC. Dexamethasone reduces energy expenditure and increases susceptibility to diet-induced obesity in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(9):E415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martin FM, Alzamendi A, Harnichar AE, Castrogiovanni D, Zubiria MG, Spinedi E, et al. Role of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in white adipose tissue beiging. Life Sci. 2023;322:121681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ramage LE, Akyol M, Fletcher AM, Forsythe J, Nixon M, Carter RN, et al. Glucocorticoids Acutely Increase Brown Adipose Tissue Activity in Humans, Revealing Species-Specific Differences in UCP-1 Regulation. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):130–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lee RA, Harris CA, Wang JC. Glucocorticoid Receptor and Adipocyte Biology. Nucl Receptor Res. 2018;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang W, Ishibashi J, Trefely S, Shao M, Cowan AJ, Sakers A, et al. A PRDM16-Driven Metabolic Signal from Adipocytes Regulates Precursor Cell Fate. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):174–89 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Abe I, Oguri Y, Verkerke ARP, Monteiro LB, Knuth CM, Auger C, et al. Lipolysis-derived linoleic acid drives beige fat progenitor cell proliferation. Dev Cell. 2022;57(23):2623–37 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Boulet N, Briot A, Galitzky J, Bouloumie A. The Sexual Dimorphism of Human Adipose Depots. Biomedicines. 2022;10(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fields DA, Krishnan S, Wisniewski AB. Sex differences in body composition early in life. Gend Med. 2009;6(2):369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Hube F, Kristensen K, Hauner H, Richelsen B. Demonstration of estrogen receptor subtypes alpha and beta in human adipose tissue: influences of adipose cell differentiation and fat depot localization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;182(1):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Anderson LA, McTernan PG, Barnett AH, Kumar S. The effects of androgens and estrogens on preadipocyte proliferation in human adipose tissue: influence of gender and site. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(10):5045–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Blouin K, Nadeau M, Perreault M, Veilleux A, Drolet R, Marceau P, et al. Effects of androgens on adipocyte differentiation and adipose tissue explant metabolism in men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(2):176–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Karastergiou K, Smith SR, Greenberg AS, Fried SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues - the biology of pear shape. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Uhrbom M, Muhl L, Genove G, Liu J, Palmgren H, Alexandersson I, et al. Adipose stem cells are sexually dimorphic cells with dual roles as preadipocytes and resident fibroblasts. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kameya T, Kawai Y, et al. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(9):1755–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Berry DC, Jiang Y, Arpke RW, Close EL, Uchida A, Reading D, et al. Cellular Aging Contributes to Failure of Cold-Induced Beige Adipocyte Formation in Old Mice and Humans. Cell Metab. 2017;25(2):481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rogers NH, Landa A, Park S, Smith RG. Aging leads to a programmed loss of brown adipocytes in murine subcutaneous white adipose tissue. Aging Cell. 2012;11(6):1074–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nguyen HP, Lin F, Yi D, Xie Y, Dinh J, Xue P, et al. Aging-dependent regulatory cells emerge in subcutaneous fat to inhibit adipogenesis. Dev Cell. 2021;56(10):1437–51 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gao Z, Daquinag AC, Fussell C, Zhao Z, Dai Y, Rivera A, et al. Age-associated telomere attrition in adipocyte progenitors predisposes to metabolic disease. Nat Metab. 2020;2(12):1482–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]