Abstract

Coelenterazine is the most common substrate for light-emitting reactions identified in luminous marine organisms. Among bioluminescent proteins engaging coelenterazine as a luciferin, Ca2+-regulated photoproteins form stable enzyme-substrate complexes offering thereby a unique opportunity to study their bioluminescence reactions in detail. Here, we used stopped-flow kinetics to investigate the formation of the emitters of recombinant aequorin, obelin, and W92F obelin activated with coelenterazine, as well as aequorin activated with coelenterazine-e. Based on the presence of up to four different spectral components, a modified unanimous kinetic model describing the bioluminescence reaction of Ca2+-regulated photoproteins is presented. The neutral, amide anionic, and phenolate anionic excited states of coelenteramide are proposed to originate from different pathways of dioxetanone decomposition with competing rates of proton transfer, radiation, and population and consequently to act as independent emitters in photoprotein bioluminescence.

Keywords: Bioluminescence, Coelenterazine, Aequorin, Obelin, Photoprotein, Stopped-flow kinetics

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Biophysics

Introduction

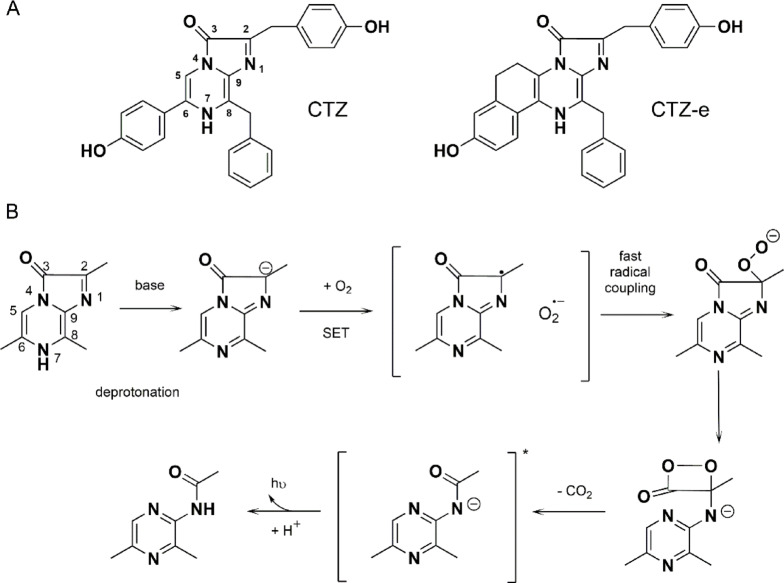

Bioluminescence is the emission of visible light by a living organism as a result of a specific enzymatic reaction. Although luminous species are present among terrestrial organisms, this phenomenon is most widespread in marine habitats1,2. Among the substrates of light-emitting reactions identified in luminous marine organisms, the imidazopyrazinone-type luciferins are most common (Fig. 1A). This type of substrates was found in such taxonomically distant luminous organisms as soft corals, decapods, copepods, medusas, ostracods, fishes etc1,3,4.

Fig. 1.

Coelenterazine and its chemiluminescence reaction. (A) Structure of coelenterazine and coelenterazine-e. (B) Coelenterazine reaction scheme based on the study of chemiluminescence of Cypridina luciferin analogs6.

Based on a model study of chemiluminescence of 6-phenyl-2-methyl-imidazopyrazinone in aprotic solvent carried out in 1960s, a mechanism of light emission reactions using imidazopyrazinone-type substrates was proposed5. According to this mechanism, the oxidative decarboxylation of coelenterazine occurs through several steps. The initial reaction with oxygen produces a primary oxygenation product, the 2-hydroperoxide, which is deprotonated and ring-closed to a dioxetanone. In DMSO and with a strong base such as potassium tert-butoxide, the chemiluminescence reaction has a spectral emission maximum at 455 nm and the fluorescent species in question was identified as the excited amide anion of coelenteramide. Without base added, the fluorescence maximum was observed at 380 nm and assigned to the neutral species.

Later this model was verified and extended with a study on chemiluminescence reactions of a number of analogs of Cypridina luciferin6. It was suggested that the first step would be deprotonation of the N7 of imidazopyrazinone with a base yielding the imidazopyrazinone anion (Fig. 1В). Then, single electron transfer (SET) from imidazopyrazinone anion to triplet oxygen affords the imidazopyrazinone radical and the superoxide anion of oxygen. The SET process requiring spin conversion is considered to be rate-limiting. The radical coupling of imidazopyrazinone radical and superoxide anion leads to the peroxide anion of imidazopyrazinone. In case of bioluminescent reactions catalyzed by coelenterazine-dependent luciferases, the cyclization of imidazopyrazinone peroxide anion will then take place. The cyclization gives dioxetanone which decomposes with the loss of CO2 generating the singlet excited state of a product.

Among bioluminescent proteins that use imidazopyrazinone-type substrates, a special place is occupied by Ca2+-regulated photoproteins isolated from various marine luminous hydromedusae1. All photoproteins consist of a single polypeptide chain of about 22 kDa to which the luciferin, a peroxy-substituted coelenterazine, is tightly bound. Hence, photoproteins can be viewed as luciferases containing a stabilized reaction intermediate7. Binding of calcium ions to photoproteins triggers the bioluminescence reaction by destabilizing the peroxy adduct of coelenterazine with consequent induction of its oxidative decarboxylation followed by generation of protein-bound coelenteramide in its excited state8,9. When excited coelenteramide relaxes to its ground state, blue light is produced with maxima in the range of 465–495 nm depending on the source organism10. Nowadays it is generally agreed that the formation of excited states in bioluminescence reactions catalyzed by imidazopyrazinone-dependent luciferases and photoproteins follows the mechanism shown in Fig. 1B.

Although Ca2+-regulated photoproteins represent a unique class of protein biochemistry the main reason to study these proteins is, in essence, their broad analytical potential. Photoproteins are highly sensitive to calcium and non-toxic for the living cells, therefore they have been widely employed as probes of intracellular Ca2+, both to assess the Ca2+ concentration under steady-state conditions and to study the role of calcium transients in the regulation of cellular functions11. With successful cloning of cDNAs encoding several hydromedusan apophotoproteins12–22 the scope of photoprotein applications has been broadened with intracellular expression of the recombinant apophotoprotein followed by external addition of coelenterazine which diffuses into the cell and forms the active photoprotein23,24. This technique allows obtaining of various cells with a “built-in” calcium indicator. The benefits of the approach are hard to overstate, since it is extremely handy and does not require laborious procedures like microinjection or liposome-mediated transfer. The success of these applications, however, depends on a number of factors among which are the rate and efficacy of the generation of an active photoprotein from apophotoprotein, coelenterazine, and oxygen, as well as any influence of the cellular environment on these processes.

During the past decades, significant progress has been attained in understanding the function of certain active site residues in decarboxylation of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine and emitter formation owing to comprehensive mutagenesis, biochemical, and structural studies. To date, tertiary structures of the four ligand-dependent conformational states of Ca2+-regulated photoproteins were determined out of the five identified by NMR25. These are photoprotein before light emission reaction, i.e., bound with 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine19,26–29; photoprotein after bioluminescence reaction, i.e., bound with coelenteramide and calcium ions30 or with coelenteramide only31; and apophotoprotein bound with calcium ions32.

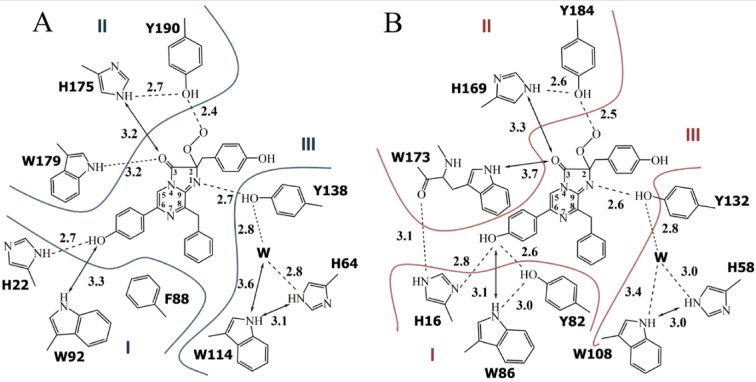

Determination of the three-dimensional structures of photoproteins has allowed localizing the amino acids forming the substrate-binding cavity. It turned out that this inner cavity is mostly formed by hydrophobic residues which are practically identical for the photoproteins isolated from different hydromedusae in spite of some distinctions in their sequences. Together with hydrophobic residues there are three histidines and three tyrosines found in aequorin and mitrocomin (or two tyrosines in obelin and clytin), which side chains are directed into the substrate-binding cavity. These His and Tyr as well as Trp residue located close to them are clustered into triads, which reside near the 2-hydroperoxy and carbonyl groups, and the N1 atom of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine as well as surround the hydroxyl group in its 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Two-dimensional drawing of the hydrogen bond network in active obelin (A) and aequorin (B). Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines; possible hydrogen bonds are shown as arrows. Distances are given in Å. I, II, and III – amino acid triads.

According to comprehensive mutagenesis studies these triads are very important for bioluminescence function of hydromedusan Ca2+-regulated photoproteins33. The triad consisting of His175, Tyr190, and Trp179 in obelin (His169, Tyr184, and Trp173 in aequorin) participates in stabilizing the peroxy group of the bound substrate and could be also involved in active photoprotein formation from apoprotein and coelenterazine34,35. His64, Tyr138, and Trp114 along with a water molecule form another triad situated near N1 of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine and are necessary for its effective decarboxylation36,37. The triad including His16, Trp82, and Tyr86 in aequorin (His22, Trp92, and Phe88 instead of Tyr in obelin) surrounds the hydroxyl group of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent of the substrate (Fig. 2).

The residues of this triad proved to affect the emitter formation through making hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl group of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent10. The light emission spectrum of aequorin has a maximum at 470 nm, whereas obelin displays a peak at 480 nm with a shoulder at 400 nm. Replacement of Phe88 in obelin by Tyr shifts its light emission maximum towards shorter wavelengths and removes the shoulder at 400 nm, whereas in aequorin the substitution of Tyr82 by Phe results in the appearance of light emission spectrum which is very similar to that of obelin38.

The indole nitrogen of Trp92 in obelin (Trp86 in aequorin) also forms a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent (Fig. 2), and thus Trp is another residue of this triad influencing photoprotein bioluminescence spectra. For instance, its replacement to Phe in both aequorin and obelin causes the appearance of bimodal light emission spectra with maxima at 400 and 470 nm39–42. The key role of hydrogen bonds formed by Tyr and Trp residues in the emitter formation in photoprotein bioluminescence reaction was confirmed by the spatial structures of certain active site variants with altered emission spectra40,41,43 and by QM/MM studies44. Noteworthy is that a similar bimodal emission spectrum is observed for aequorin activated with synthetic coelenterazine-e, in which the C5 atom of imidazopyrazinone is connected to the Cα atom of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent with an ethylene linker (CH2-CH2) (Fig. 1A)45.

Despite the fact that significant progress in understanding the emitters’ formation in photoprotein bioluminescence reaction was achieved, the exact mechanism of their generation is still unclear. To further investigate the formation of the emitters, we thoroughly studied stopped-flow kinetics of recombinant aequorin, obelin, and W92F obelin activated with coelenterazine, as well as aequorin activated with coelenterazine-e.

Results and discussion

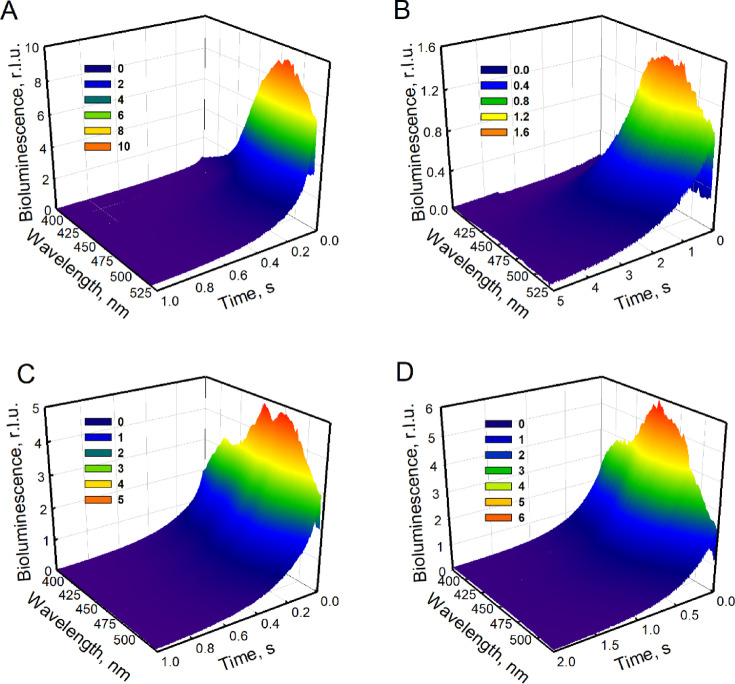

Fast bioluminescence kinetics of several Ca2+-regulated photoproteins with different spectral features were collected using the spectra-kinetics mode of the stopped-flow spectrometer. Obelin from Obelia longissima and its W92F variant were studied with native coelenterazine, aequorin from Aequorea victoria – with both native coelenterazine and coelenterazine-e analog (aequorin-e, Fig. 1A). Both W92F obelin and aequorin-e were chosen for the study due to the increased contribution of the short-wavelength emission to their bioluminescence spectra obtained by two different methods. W92F obelin with native coelenterazine demonstrates increased bioluminescence at 395 nm due to protein mutation, while aequorin-e displays the similar effect due to the reaction with chemically modified substrate. After rapid mixing with Ca2+ ions, all photoproteins displayed a prompt increase of the light signal with their spectra-kinetics profiles reaching maximal intensities within milliseconds (Fig. 3). This flash in bioluminescence intensity was followed by a slow decay of the light emission, that lasts seconds (up to 5 s in the case of aequorin), which is a typical kinetics curve for photoprotein bioluminescence reaction.

Fig. 3.

Stopped-flow spectra-kinetics profiles of photoproteins. Obelin from Obelia longissima (A), aequorin from Aequorea victoria (B), W92F obelin (C) and aequorin activated with coelenterazine-e (D); r.l.u. – relative light units.

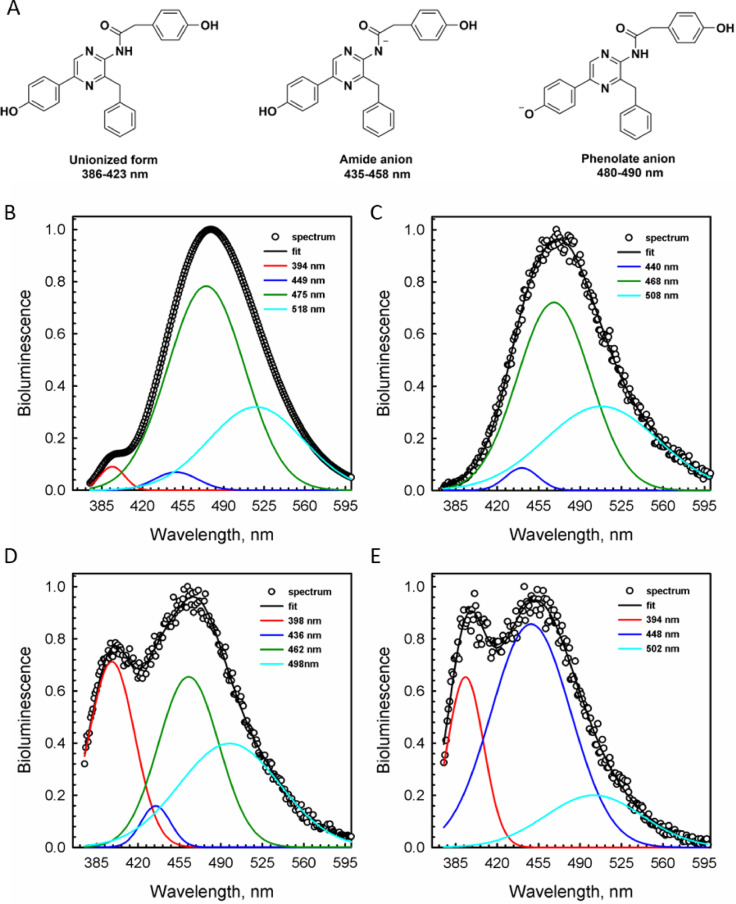

Figure 4 shows bioluminescence emission spectra of obelin and its W92F variant, and that of aequorin and aequorin-e. Bioluminescence spectral distribution of obelin has a maximum around 480 nm with a shoulder at 390 nm (Fig. 4B), whereas W92F obelin displays a complex bimodal spectrum with a maximum around 460 nm and a significant shoulder near 400 nm (Fig. 4D). Bioluminescence spectrum of aequorin has a maximum at 470 nm with no shoulder (Fig. 4C), and aequorin-e demonstrates a bimodal spectrum with a maximum at 450 nm and a substantial shoulder around 400 nm (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Ionic forms of coelenteramide (A) and emission spectra of obelin from Obelia longissima (B), aequorin from Aequorea victoria (C), W92F obelin (D) and aequorin activated with coelenterazine-e (E). Black dots – experimental spectrum, black line – spectrum fitted with Gaussian function, color lines – individual spectral components; inserted wavelength numbers correspond to the maximum of each colored curve.

On the assumption of a Gaussian energy distribution, the emission spectra of the photoproteins were resolved into several components (Fig. 4; Table 1). Thus, spectral distribution of wild-type obelin displays four components with maxima at 394 nm, 449 nm, 475 nm, and 518 nm with relative contribution of 2.3%, 3.2%, 63.3% and 31.2%, respectively (Fig. 4B). W92F obelin exhibits almost the same spectral components as wild-type obelin with maxima at 398 nm (26.0%), 436 nm (4.0%), 462 nm (35.0%), and 498 nm (35.0%) (Fig. 4D). As for aequorin, when activated with native coelenterazine its emission spectrum decomposes into three components with maxima at 440 nm (3.1%), 468 nm (57.9%), and 508 nm (39.0%) (Fig. 4C). However, aequorin-e spectral distribution differs from that of wild-type aequorin as there are three spectral components at 394 nm, 448 nm, and 502 nm with relative contributions of 19.6%, 62.5%, and 17.9% (Fig. 4E).

Table 1.

Spectral distribution of various possible emitters of photoprotein bioluminescence.

| Photoprotein | Neutral λmax, nm |

Amide anion λmax, nm |

Phenolate anion λmax, nm |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obelin |

394 nm (2.3%) |

449 nm (3.2%) |

475 nm (63.3%) |

518 nm (31.2%) |

| W92F obelin |

398 nm (26.0%) |

436 nm (4.0%) |

462 nm (35.0%) |

498 nm (35.0%) |

| Aequorin | – |

440 nm (3.1%) |

468 nm (57.9%) |

508 nm (39.0%) |

| Aequorin-e |

394 nm (19.6%) |

448 nm (62.5%) |

– |

502 nm (17.9%) |

According to the study conducted by Shimomura and Teranishi, coelenteramide can produce five different emitters due to its various ionic forms: a neutral species with a fluorescence emission maximum around 400 nm, the amide anion with a maximum around 450 nm, an ion-pair excited state with the maximum around 467 nm, the phenolate anion with a maximum around 480–490 nm, and the pyrazine-N(4) anion resonance form with a maximum ranging from 535 to 550 nm (Fig. 4A)46. Some of these coelenteramide ionic forms such as the ion-pair excited state of phenolate anion with His22 have been later excluded from the list of presumptive emitters by thorough computational studies47.

Consequently, all spectral components identified in the photoprotein bioluminescence spectra (Fig. 4) could be reasonably assigned to the known ionic forms of coelenteramide corresponding to the different emitters based on the similarities between their emission maxima (Table 1). According to the spectral decomposition analysis, obelin and W92F obelin bioluminescence displays the presence of the four different spectral components, while aequorin and aequorin-e – only three ones. Aequorin with native coelenterazine lacks the violet spectral band commonly assigned to the neutral excited coelenteramide while displaying two lower energy excited states. On the contrary, aequorin-e bioluminescence spectrum has clearly visible high energy band corresponding to the neutral excited coelenteramide and lacks one of the lower energy excited states typical for wild-type aequorin. The neutral excited species of coelenteramide is also clearly present in the spectra of both obelins albeit with different ratio.

The spectra of all four proteins also display a component with a maximum around 435–450 nm that can be assigned to the amide anion of the excited coelenteramide (Table 1). While being a minor component in the spectra of aequorin and both obelins, the amide anion contributes the most to the spectrum of aequorin-e.

Contribution of each individual spectral component was estimated as the percentage of its decomposed spectrum relative to the total spectrum fitted with Gaussian function (data from Fig. 4) (shown in parentheses).

Although it is tempting to assign different lowest energy emitters to the different ionic forms of coelenteramide such as phenolate and pyrazine anions, the calculations made for obelin fluorescence emitters show that the computed emission energies of all other low-energy coelenteramide forms (except phenolate anion) fail to match experimental data and therefore can be successfully ruled out48. At the same time, obelin bioluminescence spectrum was stated to be highly determined by the position of the proton between the oxygen atom of coelenteramide phenolic group in an excited state and the nitrogen atom of His2248. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that broadened bioluminescence spectra (460–508 nm) and consequently several components obtained through spectral decomposition for photoproteins in this study might be due to different positions of the said proton and can be matched to the phenolate anion species.

To further investigate the dynamics of the excited states of coelenteramide in photoprotein bioluminescence, we thoroughly studied fast kinetics of the selected photoproteins at the wavelengths corresponding to the emission maxima of the isolated spectral components (Table 1). Photoprotein bioluminescence kinetics can only be described with several rate constants, suggesting multiple reaction stages and intermediates. To analyze the kinetic traces obtained for the selected photoproteins at the specific wavelengths from stopped-flow spectra-kinetics profiles, we applied a modified unanimous kinetic model, which has satisfactorily described photoprotein bioluminescence signals from different organisms (Fig. 5A)49.

Fig. 5.

Fast kinetics of photoprotein bioluminescence. (A) Kinetic scheme of photoprotein bioluminescence allowing formation of the four emitters and corresponding system of differential equations (see the text for explanation on different intermediates). Stopped-flow kinetics of obelin from Obelia longissima (B), aequorin from Aequorea victoria (C), W92F obelin (D), and aequorin with coelenterazine-e (E). Kinetics is registered at the wavelengths corresponding to the emission maxima of various possible emitters of coelenterazine-dependent bioluminescence.

This model includes a positive cooperativity effect between the two Ca2+-binding sites of the C-terminal domain (S3 route), since frequently the paired EF-hand motifs are capable of binding calcium ions with positive cooperativity, that is calcium binding with one of the Ca2+-binding sites increases affinity of another Ca2+-binding site50. The model also takes into account the fact that an excited state could be formed as the result of binding of only one calcium ion to either of N-terminal (S1 route) or C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites (S2 route). Furthermore, since in our experimental setup all photoproteins were tested under saturating calcium concentration, the reverse rate constants for all calcium-binding steps have been neglected in the kinetic scheme. The kinetic model was also modified to ascertain the formation of three or four different emitters with the possibility to generate any emitter through three possible calcium binding routes (S1, S2, or S3).

By applying the modified photoprotein reaction model, a good fit to the experimental data is achieved for all four studied photoproteins at all selected wavelengths (Fig. 5). Rate constants obtained from the fits of experimental kinetic curves to the model presented in Fig. 5 are summarized in Table 2. The results indicate that the bioluminescence reactions of the four photoproteins reveal considerable differences in the rates of individual steps.

Table 2.

Kinetic properties of several photoprotein bioluminescence emitters.

| Protein | k1, M− 1s− 1 |

k2, M− 1s− 1 |

k3, M− 1s− 1 |

k4, s− 1 |

k5, s− 1 |

k6, s− 1 |

k7, s− 1 |

k8, s− 1 |

k9, s− 1 |

Average contribution of particular wavelength for S1/S2/S3 routes, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obelin | 29.9 | 176.8 | 48.6 | 157.7 | 13.1 | 4.8 | 110.0 | 33.2 | 53.2 |

4 (394 nm) 27 (449 nm) 40 (475 nm) 29 (518 nm) |

| W92F obelin | 18.1 | 231.3 | 59.9 | 73.1 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 89.6 | 595.0 | 82.6 |

29 (398 nm) 23 (436 nm) 30 (462 nm) 18 (498 nm) |

| Aequorin | 49.7 | 105.2 | 120.2 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 154.4 | 507.6 | 242.0 |

36 (440 nm) 45 (468 nm) 19 (508 nm) |

| Aequorin-e | 110.8 | 171.9 | 157.5 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 1.3 | 96.0 | 521.5 | 191.9 |

28 (394 nm) 46 (448 nm) 26 (502 nm) |

For example, according to the model, binding of calcium ion to the N-terminal Ca2+-binding site (S1 route) governed by k1 proceeds much faster in the case of aequorin-e (110.8 M− 1s− 1). As for the two C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites, binding of one calcium ion to either of them (S2 route) is governed by the rate constant k2, because we cannot distinguish these two sites in the model and therefore consider them as equivalent binding sites. Both obelins and aequorin-e display higher values of the second-order rate constant k2, while aequorin shows the lowest rate of calcium binding to the C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites (Table 2). A different tendency is observed for the formation of the photoprotein state with two calcium ions bound with cooperative effect (S3 route) governed by k3. The values of k3 are two-three times lower in the case of both obelins compared to the aequorins (Table 2).

In our model there are three intermediate states of photoproteins depending on the number and order of calcium ions bound—Z1 (one calcium ion in N-terminal binding site), Z2 (one calcium ion bound to one of the C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites), and Z3 (two calcium ions in both C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites) (Fig. 5A). Chemically all Z intermediates would comprise some stages prior to dioxetanone decomposition such as the formation of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine anion or dioxetanone anion. The formation of these intermediates is respectively governed by the rate constants k4, k5, and k6 and is generally faster in the case of both obelins. Regarding the excited state formation rates k7, k8, and k9, there are also considerable differences in the rate constants for all four photoproteins depending on the type of intermediate Z it is formed from (Table 2).

As is clearly seen from the spectra-kinetics data of all photoproteins described here (Fig. 5), every spectral component obtained through spectral decomposition originates in the earliest reaction stages of the photoprotein bioluminescence. Moreover, rapid mixing stopped-flow spectroscopy data presented show that the rate constants controlling different stages of photoprotein bioluminescence do not heavily depend on the detection wavelength in the case of all studied photoproteins (Fig. 5). This fact prompts us to revise the previous explanation of the nature of light emitters involved in the photoprotein bioluminescence with neutral species being the primary emitter and phenolate anion being the product of proton transfer from the neutral coelenteramide30,51,52.

Based on site-directed mutagenesis and structural studies of photoproteins together with chemical studies of coelenterazine model compounds it was suggested that photoprotein-bound coelenteramide populates at least two excited states, the neutral and phenolate anionic state. The total bioluminescence spectrum is a consequence of competition between the radiation rate from the primary neutral excited state and the rate of population of the excited phenolate anion51. The results of excited state dynamics of photoprotein-bound coelenteramide studied with fluorescence relaxation spectroscopy strongly suggested neutral coelenteramide to be the first excited state formed, which reverts to the phenolate anion on a picosecond time scale52. However, our current analysis of the dynamics of various possible emitters of the photoprotein bioluminescence reaction shows the consistent presence of amide anion in all studied obelins and aequorins (Table 1). Moreover, all isolated spectral components (three for aequorins and four for obelins) are generated very fast with similar kinetic constants and the ratio between different emitters strongly depends on the type of both photoprotein and coelenterazine used. This suggests the important effect of the amino acid environment on the emitter formation and distribution.

As is evident from the comparison of the crystal structures of wild-type obelin and its W92F variant, the Trp to Phe substitution leads to small changes in the hydrogen bond network around the hydroxyl moiety of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine, potentially removing the hydrogen bond and thus enhancing generation of the coelenteramide neutral species40. There is no aequorin-e spatial structure available yet, however the crystal structure of obelin-v containing a similar coelenterazine analog in the active site suggests that binding of a bulkier compound induces certain rearrangements of the hydrogen bond network both around the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent and hydroperoxyl group of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine53. Since photoprotein bioluminescence spectra are heavily influenced by the position of the proton between the oxygen atom of coelenteramide phenolic group in an excited state and the N1 atom of His2248, any substantial alteration of the hydrogen bond network around the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine and His22 could potentially result in a different distance the proton has to move from the oxygen of coelenteramide phenolic group to the His22 nitrogen leading to the prominent changes of emitter distribution.

Thermal decomposition studies of peroxidized coelenterazines have indicated that both homolytic and charge-transfer biradical mechanisms of dioxetanone decomposition are energetically feasible and that the balance between these pathways in the photoprotein active site depends on the protonation state of the peroxy substrate as modulated by the polarity and hydrogen bonding capacity of the protein environment54. This proposition was supported by the properties of aequorin and obelin variants39,40. For example, the enhanced bioluminescence emission at 400 nm observed due to the replacement of Trp92 in obelin with Phe can be explained by the bicyclic ring of tryptophan being important for pKa regulation55. Recent experimental and theoretical studies on the chemiluminescence of imidazopyrazinone-type substrates confirmed thermolysis of both anionic and neutral dioxetanones to proceed by a stepwise biradical mechanism56,57. Moreover, it was proposed that even if dioxetanone anion is indeed the primary decomposition product of the bioluminescence reaction, it could be easily converted into a neutral dioxetanone within the active site of the luciferase or photoprotein with the involvement of the cationic amino acids such as His or Lys.

However, based on the theoretical calculation studies there is still an ongoing discussion in the field about the exact mechanism of dioxetanone decomposition and the chemiexcitation efficiency of neutral and anionic dioxetanones. Thus, one hypothesis proposes anionic dioxetanone to decompose through an CIEEL (chemically induced electron-exchange luminescence) or CTIL (charge-transfer initiated luminescence) mechanism, while neutral dioxetanone decomposes through an entropic trapping mechanism. In coelenterazine-dependent bioluminescence the excited state is formed with high efficiency and thus its formation must be explained by the CIEEL/CTIL mechanism of anionic dioxetanone decomposition58. Contradicting hypothesis states that chemiexcitation of neutral dioxetanone is more efficient than that of other dioxetanone species observed in imidazopyrazinone-based systems59,60 and that there is no clear relationship between electron (ET)/charge (CT) transfer and efficient bioluminescence59. A neutral dioxetanone intermediate can be responsible for efficient chemiexcitation by attractive electrostatic interactions between the CO2 and coelenteramide moieties, which allow the reacting dioxetanone to spend time in a PES region of degeneracy between singlet ground and excited states.

With the results of thermal decomposition of peroxidized coelenterazines considered, it is reasonable to assume that different coelenteramide excited states, such as neutral, amide anion, and phenolate anion, probably generated from different pathways of dioxetanone decomposition, act as independent emitters in photoprotein bioluminescence. With the water molecule acting as a catalyst for the decarboxylation process37, the dioxetanone anion is to be protonated prior to its decomposition. As a result, neutral dioxetanone is formed, and its subsequent decomposition leads to the formation of a primary emitter, neutral coelenteramide, which emits light at λmax = 390–400 nm46. The excited state of coelenteramide emitting light at longer wavelengths, which is believed to be the excited phenolate anion, arises as a result of transient proton dissociation of the hydroxyl group of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent of coelenterazine in the direction to His22, which is located within hydrogen bond distance. Since its fluorescence life-time is 5–6 ns52, there is enough time for “proton displacement” to occur before light emission. It is interesting to note that the relative bioluminescence activity of aequorin-e compared to aequorin with native coelenterazine is about 35%, which indicates that the prominent shift to anionic dioxetanone decomposition route in the case of aequorin-e leads to the loss in chemiexcitation efficiency, thus supporting the idea on neutral dioxetanone to be the most efficient dioxetanone species observed in imidazopyrazinone-based systems60.

This idea is supported by the chemiluminescence properties of a coelenterazine model compound in protic solvent at -78 °C61. Using low-temperature NMR, the structure of the photo-oxygenation product was established to be two peroxidic species with dioxetanone anion being more stable as compared to the neutral dioxetanone intermediate. In addition, two independent pathways for decarboxylation were offered: one is dioxetanone decomposition to emit light through neutral form (with emission at 400 nm), the other is 2-hydroperoxide decomposition through anionic species (with emission at 470 nm). Thus, with neutral and amide anion of excited coelenteramide formed independently via different pathways of dioxetanone decomposition and phenolate anion formed rapidly via proton transfer from the neutral species before the light emission occurs, the final photoprotein bioluminescence spectra would be the product of competition between the radiation rate from the primary neutral excited state and the rate of population of the excited phenolate anion species.

Conclusion

In this paper for the first time the transient kinetics of calcium-regulated emitter formation in coelenterazine-dependent aequorin and obelin has been studied in spectra-kinetics mode. As a reference, W92F obelin, and aequorin activated with coelenterazine-e, both displaying pronounced bimodal bioluminescence spectra, were studied as well. The rapid mixing stopped-flow spectroscopy data showed the presence of three and four different components in the case of aequorins and obelins, respectively. In the course of the bioluminescence reaction, decomposition of the primarily formed dioxetanone anion leads to the formation of excited amide anion of coelenteramide with emission around 440 nm, but most of the dioxetanone anion is to be protonated prior to its decomposition. When the neutral dioxetanone decomposes, one possible emitter would be the neutral coelenteramide, which emits light with λmax at 390 nm. If transient proton dissociation of the hydroxyl group of the 6-(p-hydroxyphenyl) substituent of coelenteramide occurs in the direction of His22, the excited phenolate anion is to be formed. The excited phenolate anion of coelenteramide can emit light with different wavelengths (460–508 nm) due to the different positions of the proton between the oxygen of coelenteramide phenolic group and the His22 nitrogen.

Thus, the neutral, amide anionic, and phenolate anionic excited states of coelenteramide are proposed to originate from the different pathways of dioxetanone decomposition with competing rates of proton transfer, radiation and population, and consequently to act as independent emitters in photoprotein bioluminescence. Despite theoretical calculations suggested otherwise, the main pathway of dioxetanone decomposition in the case of both aequorin and obelin is shown to be the neutral dioxetanone route with the possibility to shift the balance in favor of dioxetanone anion route using aequorin with coelenterazine-e analog.

To adequately analyze the rapid mixing stopped-flow spectroscopy data, a modified unanimous kinetic model describing the bioluminescence reaction of Ca2+-regulated photoproteins was proposed. The suggested reaction scheme includes a “positive cooperativity” effect between Ca2+-binding sites of the C-terminal domain and takes into account the fact that an excited state could be formed as the result of binding of only one calcium ion to any of the Ca2+-binding sites, which allows for the formation of up to four different emitters. The kinetic model proposed in the present study provides a very good fit to the experimental rapid mixing curves for the different photoproteins and coelenterazine analogs used. Further spectroscopic studies combined with theoretical computation might lead to better understanding of the origin of light emitters involved in photoprotein bioluminescence.

Materials and methods

Materials

Coelenterazine and coelenterazine-e were obtained from NanoLight Technology, a division of Prolume Ltd. (Pinetop, AZ, USA). Other chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and of the purest grade available.

Preparation of the photoprotein samples

For apophotoprotein production, E. coli BL21-Gold (DE3) Codon Plus (RIPL) cells were transformed with the expression plasmids pET22-A732, pET19-OL862, and pET19-W92F40 carrying the cDNAs encoding apo-aequorin, apo-obelin, and W92F apo-obelin, respectively. Obelin and aequorin as well as W29F obelin were purified and activated with native coelenterazine or coelenterazine-e, as described elsewhere63. Coelenterazine concentration in the methanol stock solution was determined spectrophotometrically using the extinction coefficient ε435nm = 9800 M− 1cm− 1.1 The protein concentration was determined with the Dc Bio-Rad protein assay kit. The freshly purified photoproteins were immediately used in the experiments.

Stopped-flow measurements

Stopped-flow experiments were performed with EDTA-free solutions of photoproteins64. EDTA was removed from the purified proteins by gel filtration on a 1.5 × 6.5 cm D-Salt dextran desalting Pierce column (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). The column was equilibrated and the protein was eluted with 150 mM KCl, 5 mM piperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), pH 7.0 previously passed (twice) through freshly washed beds of Chelex 100 chelating resin (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, USA) to remove trace amounts of Ca2+. The fractions containing photoproteins were identified by bioluminescence assay. To avoid possible contamination with EDTA, only the first few protein fractions to come off the column were used for rapid mixing measurements.

The light response kinetics after sudden exposure to a saturating Ca2+ concentration was examined with an SX20 stopped-flow machine (cell volume 20 µl, dead-time 1.1 ms) (Applied Photophysics, UK) using following protocol64. The temperature was controlled with a circulating water bath and was set at 20 °C in all experiments. The Ca2+ syringe contained 40 mM Ca2+, 30 mM KCl, 5 mM PIPES buffer, pH 7.0. The photoprotein was dissolved in a Ca2+-free solution of the same ionic strength: 150 mM KCl, 5 mM PIPES, pH 7.0 (protein concentration − 2 µM). Both syringes were prewashed with the EDTA solution and then, thoroughly, with deionized water. The solutions were mixed in equal volumes. Thus, the final concentrations of Ca2+ and photoprotein in the reaction mixture were 20 mM and 1 µM, respectively.

Spectra-kinetics analysis

To determine the maxima of the spectral components the emission spectra were fitted with a sum of Gaussian functions. For kinetic analysis, simulations were performed with the application made in SciLab environment supplied with built-in function ode for integration of differential equation systems49. Nonlinear least squares fitting using Nelder–Mead optimization method built in the SciLab 5.4.1 was applied for finding the best solution. MSE (mean square error) and MAPE (mean absolute percentage errors) were used as a measure of the differences between values predicted by a model and the values observed in the experiments49.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Nicole Leferink for assistance with initial stopped-flow experiments.

Author contributions

E.V.E. prepared photoprotein samples, performed measurements, suggested reaction model, analyzed data; S.I.B developed computer model, performed calculations; N.P.M. prepared photoprotein sample, performed measurements; W.J.H. B. analyzed data, supervised project; E.S.V. analyzed data, supervised project; All authors prepared and edited the manuscript.

Funding

The studies were supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant number 24-44-00009).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are included within the article and are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shimomura, O. Bioluminescence: Chemical Principles and Methods (World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd, 2006).

- 2.Wilson, T. & Hastings, J. W. Bioluminescence: Living Lights, Lights for Living (Harvard University Press, 2013).

- 3.Haddock, S. H., Moline, M. A. & Case, J. F. Bioluminescence in the sea. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci.2, 443–493 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markova, S. V. & Vysotski, E. S. Coelenterazine-dependent luciferases. Biochem. (Moscow). 80, 714–732 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCapra, F. & Chang, Y. C. The chemiluminescence of a Cypridina luciferin analogue. Chem. Commun.19, 1011–1012 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo, H. et al. Substituent effects on the kinetics for the chemiluminescence reaction of 6-arylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-ones (Cypridina luciferin analogues): Support for the single electron transfer (SET)–oxygenation mechanism with triplet molecular oxygen. Tetrahedron Lett.46, 7701–7704 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hastings, J. W. & Gibson, Q. H. Intermediates in the bioluminescent oxidation of reduced flavin mononucleotide. J. Biol. Chem.238, 2537–2554 (1963). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimomura, O. & Johnson, F. H. Structure of the light-emitting moiety of aequorin. Biochemistry11, 1602–1608 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormier, M. J. et al. Evidence for similar biochemical requirements for bioluminescence among the coelenterate. J. Cell. Physiol.81, 291–297 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vysotski, E. S. & Lee, J. Ca2+-regulated photoproteins: structural insight into the bioluminescence mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res.37, 405–415 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blinks, J. R., Wier, W. G., Hess, P. & Prendergast, F. G. Measurement of Ca2+ concentrations in living cells. Prog Biophys. Mol. Biol.40, 1–114 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasher, D., McCann, R. O. & Cormier, M. J. Cloning and expression of the cDNA coding for aequorin, a bioluminescent calcium-binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.126, 1259–1268 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye, S. et al. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for the luminescent protein aequorin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 82, 3154–3158 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasher, D. C., McCann, R. O., Longiaru, M. & Cormier, M. J. Sequence comparisons of complementary DNAs encoding aequorin isotypes. Biochemistry26, 1326–1332 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye, S. & Tsuji, F. I. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for the Ca2+-activated photoprotein, Clytin. FEBS Lett.315, 343–346 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markova, S. V. et al. Green-fluorescent protein from the bioluminescent jellyfish Clytia gregaria: cDNA cloning, expression, and characterization of novel Recombinant protein. Photochem. Photobiol Sci.9, 757–765 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fourrage, C., Swann, K., Garcia, G., Campbell, A. K. & Houliston, E. An endogenous green fluorescent protein-photoprotein pair in Clytia hemisphaerica eggs shows co-targeting to mitochondria and efficient bioluminescence energy transfer. Open. Biol.4, 130206 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagan, T. F., Ohmiya, Y., Blinks, J. R., Inouye, S. & Tsuji, F. I. Cloning, expression and sequence analysis of cDNA for the Ca2+-binding photoprotein, mitrocomin. FEBS Lett.333, 301–305 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burakova, L. P. et al. Mitrocomin from the jellyfish Mitrocoma cellularia with deleted C-terminal tyrosine reveals a higher bioluminescence activity compared to wild type photoprotein. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 162, 286–297 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illarionov, B. A., Markova, S. V., Bondar, V. S., Vysotski, E. S. & Gitelson, J. I. Cloning and expression of cDNA for the Ca2+-activated photoprotein obelin from the hydroid polyp Obelia longissima. Dokl. Akad. Nauk.326, 911–913 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Illarionov, B. A., Bondar, V. S., Illarionova, V. A. & Vysotski, E. S. Sequence of the cDNA encoding the Ca2+-activated photoprotein obelin from the hydroid polyp Obelia longissima. Gene153, 273–274 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markova, S. V. et al. Obelin from the bioluminescent marine hydroid Obelia geniculata: Cloning, expression, and comparison of some properties with those of other Ca2+-regulated photoproteins. Biochemistry41, 2227–2236 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight, M. R., Campbell, A. K., Smith, S. M. & Trewavas, A. J. Transgenic plant aequorin reports the effects of touch and cold-shock and elicitors on cytoplasmic calcium. Nature352, 524–526 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzuto, R., Simpson, A. W. M., Brini, M. & Pozzan, T. Rapid changes of mitochondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature358, 325–327 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, J., Glushka, J. N., Markova, S. V. & Vysotski, E. S. Protein conformational changes in obelin shown by 15N-HSQC nuclear magnetic resonance. in Bioluminescence & Chemiluminescence (eds Case, J. F. et al.) 99–102. (World Scientific Publishing Company, 2001).

- 26.Head, J. F., Inouye, S., Teranishi, K. & Shimomura, O. The crystal structure of the photoprotein aequorin at 2.3 Å resolution. Nature405, 372–376 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, Z. J. et al. Structure of the Ca2+-regulated photoprotein obelin at 1.7 Å resolution determined directly from its sulfur substructure. Protein Sci.11, 2085–2093 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, Z. J. et al. Atomic resolution structure of obelin: Soaking with calcium enhances electron density of the second oxygen atom substituted at the C2-position of coelenterazine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.311, 433–439 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Titushin, M. S. et al. NMR-derived topology of a GFP-photoprotein energy transfer complex. J. Biol. Chem.285, 40891–40900 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, Z. J. et al. Crystal structure of obelin after Ca2+-triggered bioluminescence suggests neutral coelenteramide as the primary excited state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103, 2570–2575 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Deng, L. et al. Crystal structure of a Ca2+-discharged photoprotein: Implications for mechanisms of the calcium trigger and bioluminescence. J. Biol. Chem.279, 33647–33652 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng, L. et al. All three Ca2+-binding loops of photoproteins bind calcium ions: the crystal structures of calcium-loaded apo-aequorin and apo-obelin. Protein Sci.14, 663–675 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eremeeva, E. V. & Vysotski, E. S. Exploring bioluminescence function of the Ca2+-regulated photoproteins with site-directed mutagenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 95, 8–23 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eremeeva, E. V. et al. Bioluminescent and spectroscopic properties of His-Trp-Tyr triad mutants of obelin and aequorin. Photochem. Photobiol Sci.12, 1016–1024 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eremeeva, E. V. et al. Oxygen activation of apo-obelin-coelenterazine complex. Chembiochem14, 739–745 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natashin, P. V. et al. Structures of the Ca2+-regulated photoprotein obelin Y138F mutant before and after bioluminescence support the catalytic function of a water molecule in the reaction. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.70, 720–732 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natashin, P. V. et al. The role of Tyr-His-Trp triad and water molecule near the N1-atom of 2-hydroperoxycoelenterazine in bioluminescence of hydromedusan photoproteins: structural and mutagenesis study. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 6869 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stepanyuk, G. A. et al. Interchange of aequorin and obelin bioluminescence color is determined by substitution of one active site residue of each photoprotein. FEBS Lett.579, 1008–1014 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohmiya, Y., Ohashi, M. & Tsuji, F. I. Two excited states in aequorin bioluminescence induced by tryptophan modification. FEBS Lett.301, 197–201 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng, L. et al. Structural basis for the emission of violet bioluminescence from a W92F obelin mutant. FEBS Lett.506, 281–285 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vysotski, E. S. et al. Violet bioluminescence and fast kinetics from W92F obelin: Structure-based proposals for the bioluminescence triggering and the identification of the emitting species. Biochemistry42, 6013–6024 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malikova, N. P. et al. Spectral tuning of obelin bioluminescence by mutations of Trp92. FEBS Lett.554, 184–188 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Natashin, P. V., Markova, S. V., Lee, J., Vysotski, E. S. & Liu, Z. J. Crystal structures of the F88Y obelin mutant before and after bioluminescence provide molecular insight into spectral tuning among hydromedusan photoproteins. FEBS J.281, 1432–1445 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao, M., Ding, B. W. & Liu, Y. J. Tuning the fluorescence of calcium-discharged photoprotein obelin via mutating at the His22-Phe88-Trp92 triad—A QM/MM study. Photochem. Photobiol Sci.18, 1823–1832 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimomura, O. Cause of spectral variation in the luminescence of semisynthetic aequorins. Biochem. J.306, 537–543 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimomura, O. & Teranishi, K. Light-emitters involved in the luminescence of coelenterazine. Luminescence15, 51–58 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen, S., Navizet, I., Lindh, R., Liu, Y. & Ferré, N. Hybrid QM/MM simulations of the obelin bioluminescence and fluorescence reveal an unexpected light emitter. J. Phys. Chem. B118, 2896–2903 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomilin, F. N. & Antipina, L. Y. Fluorescence of calcium-discharged obelin: The structure and molecular mechanism of emitter formation. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys.422, 279–284 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eremeeva, E. V., Bartsev, S. I., van Berkel, W. J. & Vysotski, E. S. Unanimous model for describing the fast bioluminescence kinetics of Ca2+-regulated photoproteins of different organisms. Photochem. Photobiol. 93, 495–502 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chazin, W. J. Relating form and function of EF-hand calcium binding proteins. Acc. Chem. Res.44, 171–179 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vysotski, E. S. & Lee, J. Bioluminescent mechanism of Ca2+-regulated photoproteins from three-dimensional structures. in Luciferases and Fluorescent Proteins: Principles and Advances in Biotechnology and Bioimaging (eds Viviani, V. R. & Ohmiya, Y.) 19–41 (Transworld Research Network, 2007).

- 52.van Oort, B. et al. Picosecond fluorescence relaxation spectroscopy of the calcium-discharged photoproteins aequorin and obelin. Biochemistry48, 10486–10491 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larionova, M. D. et al. Crystal structure of semisynthetic obelin-v. Protein Sci.31, 454–469 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isobe, H., Yamanaka, S., Okumura, M. & Yamaguchi, K. Theoretical investigation of thermal decomposition of peroxidized coelenterazines with and without external perturbations. J. Phys. Chem. A113, 15171–15187 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dougherty, D. A. Cation-pi interactions in chemistry and biology: A new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Science271, 163–168 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pinto da Silva, L., Magalhães, C. M., Crista, D. M. A. & Esteves da Silva, J. C. G. Theoretical modulation of singlet/triplet chemiexcitation of chemiluminescent imidazopyrazinone dioxetanone via C8-substitution. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci.16, 897–907 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Min, C. G., Ferreira, P. J. O. & Pinto da Silva, L. Theoretically obtained insight into the mechanism and dioxetanone species responsible for the singlet chemiexcitation of coelenterazine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 174, 18–26 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding, B. W., Naumov, P. & Liu, Y. J. Mechanistic insight into marine bioluminescence: Photochemistry of the chemiexcited Cypridina (sea firefly) lumophore. J. Chem. Theory Comput.11, 591–599 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magalhães, C. M. Esteves da Silva, J. C. G. & Pinto da Silva, L. Study of coelenterazine luminescence: Electrostatic interactions as the controlling factor for efficient chemiexcitation. J. Lumin.199, 339–347 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie, J. M. et al. Theoretical study on the formation and decomposition mechanisms of coelenterazine dioxetanone. J. Phys. Chem. A127, 3804–3813 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Usami, K. & Isobe, M. Low-temperature photooxygenation of coelenterate luciferin analog synthesis and proof of 1,2-dioxetanone as luminescence intermediate. Tetrahedron52, 12061–12090 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Markova, S. V., Vysotski, E. S. & Lee, J. Obelin hyperexpression in E. coli, purification and characterization. in Bioluminescence & Chemiluminescence (eds Case, J. F. et al.) 115–118 (World Scientific Publishing Company, 2001).

- 63.Malikova, N. P. et al. Specific activities of hydromedusan Ca2+-regulated photoproteins. Photochem. Photobiol.98, 275–283 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malikova, N. P., Burakova, L. P., Markova, S. V. & Vysotski, E. S. Characterization of hydromedusan Ca2+-regulated photoproteins as a tool for measurement of Ca2+ concentration. Anal. Bioanal Chem.406, 5715–5726 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are included within the article and are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.