Abstract

Fluorescence microscopy is indispensable for visualizing biological structures and dynamics, yet its efficiency is limited—over half of emitted photons fall outside the objective’s numerical aperture and go undetected. Here, we introduce Paired-Objectives Photon Enhancement (POPE) microscopy, which increases photon collection efficiency by up to two-fold using a single excitation source, single detector, and dual objectives. By integrating a 4f optical system with a reflective mirror positioned opposite the objective in an inverted microscope, POPE redirects a substantial portion of otherwise lost photons into the detection pathway. Compatible with super-resolution, confocal, epifluorescence, and autofluorescence modalities, POPE improves spatial resolution, acquisition speed, and signal-to-noise ratio, particularly under photon-limited conditions. It has been validated across fluorophore solutions, subcellular structures, live cells, and thick tissues, consistently enhancing imaging performance. As a modular and cost-effective upgrade for standard inverted microscopes, POPE extends access to high-sensitivity fluorescence imaging and enables new applications in cell biology, biophysics, and biomedical research.

Subject terms: Nanoscale biophysics, Fluorescence spectroscopy, Super-resolution microscopy

Fluorescence microscopes lose over half the emitted light, limiting image clarity. Weidong Yang and colleagues here report the Paired-Objectives Photon Enhancement method to double photon capture, enhancing brightness and resolution in biological imaging.

Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy is essential for studying biological systems, yet its effectiveness is hampered by a fundamental limitation: over half of emitted photons escape detection due to the typical isotropic emission of fluorophores1,2. In conventional setups—whether inverted or upright—a single objective captures photons from only one side of the sample, restricting collection to a hemispherical wavefront3,4. The efficiency of this process is governed by the objective’s numerical aperture (NA = n × sin(α)), where n is the refractive index and α is the angular aperture. Even with high-NA objectives (α approaching 60°), the solid angle of collection approximates π steradians, capturing just one-quarter of emitted photons while three-quarters are lost5,6. This inefficiency persists across modalities, from epifluorescence and confocal microscopy to super-resolution techniques that surpass the diffraction limit.

Super-resolution light microscopy has revolutionized biological imaging by surpassing the diffraction limit of light, enabling visualization of structures at the nanoscale in live cells and tissues. Current methods include stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, which sharpens resolution to ~50 nm using a depletion beam7,8; structured illumination microscopy (SIM), achieving ~100 nm resolution with patterned light9; and single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), such as stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) and photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM), offering ~20–50 nm precision by localizing sparse fluorophores10–12. Despite their transformative capabilities, these techniques remain constrained by photon loss, with substantial fractions of emitted light evading capture. This reduced photon budget limits sensitivity, resolution, and imaging speed, underscoring the need for innovative solutions.

Here, we introduce paired-objectives photon enhancement (POPE) microscopy to address this pervasive issue13. Unlike dual-objective systems that require two excitation sources or separate detectors, POPE enhances photon collection through a simplified optical design—a 4f system combined with a reflective mirror positioned above the sample, opposite the objective in an inverted microscope. This configuration captures upward-emitted photons and redirects them to the objective’s focal plane, where they merge with downward-emitted photons. Simulations and experiments demonstrate that POPE can increase photon collection efficiency by up to twofold, enhancing the overall photon budget. This modular, adaptable system improves spatial resolution, sensitivity, and detection speed across techniques like super-resolution, confocal, epifluorescence, and autofluorescence microscopy. By integrating seamlessly with existing inverted platforms, POPE offers a versatile, transformative tool for fluorescence imaging.

Results

Optical setup of POPE microscopy

Unlike conventional inverted microscope setups that use a single objective below the sample, POPE employs a dual-objective architecture with two high-performance objectives symmetrically positioned above and below the fluorescent specimen. The lower (primary) objective delivers excitation and collects downward-emitted fluorescence, while the upper (secondary) objective captures upward-emitted photons that would otherwise be lost. By effectively doubling the solid angle of light collection, this configuration can boost fluorescence signal by up to twofold compared to single-objective systems (Fig. 1a). The secondary objective is matched to the primary in numerical aperture (NA) or exceeds it, ensuring efficient capture of divergent emission (Fig. 1a).

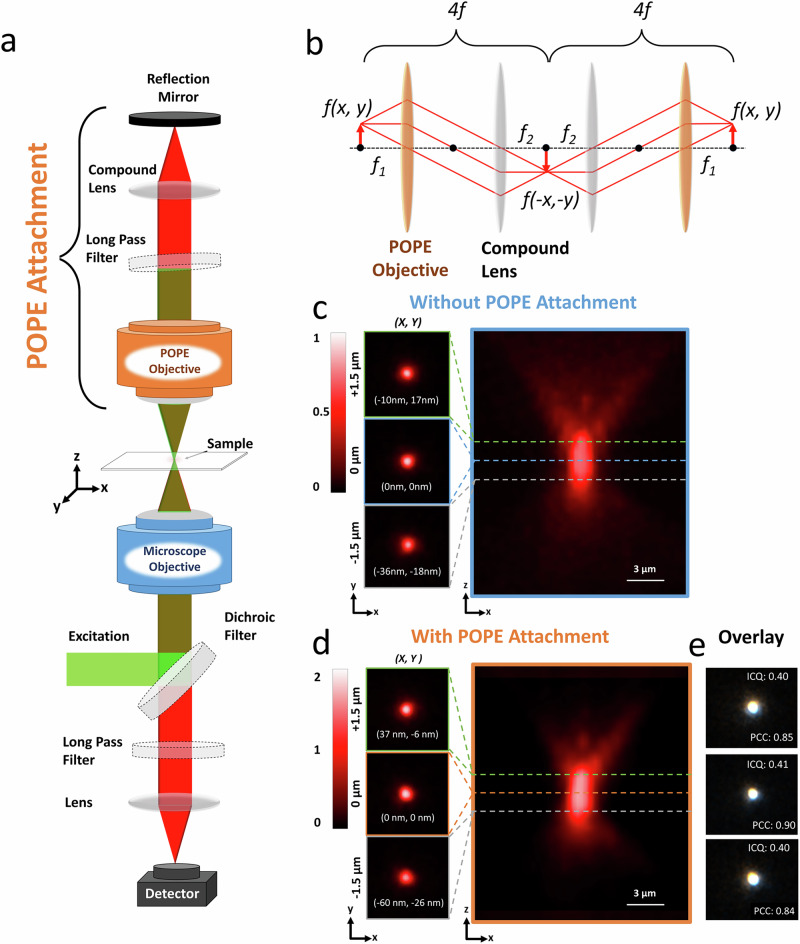

Fig. 1. Paired objective photon enhancement (POPE) microscopy overview.

a Simplified optical schematic of POPE microscopy, featuring the microscope objective (blue), POPE objective (orange), and key optical components. b Diagram of two sequential 4f configurations, with the POPE objective (focal length ) and a compound lens (focal length ), spaced apart. c Illumination point spread functions (iPSFs) for a ×60 objective (NA 1.0) without POPE attachment, showing lateral (x, y) slices at +1.5 µm, 0 µm, and −1.5 µm from the focal plane, extracted from the axial (x, z) iPSF along dotted lines. Coordinates (x, y) indicate offsets from the center (0, 0) at 0 µm. Color bar indicates normalized intensity from low (0) to high (1). d iPSF for the same ×60 objective (NA 1.0) with POPE attachment (including an identical ×60 objective, NA 1.0), normalized to the iPSF in (c). The color bar represents normalized intensity values from 0 (minimum) to 2 (maximum). Coordinates (x, y) mark offsets from the center (0, 0) at 0 µm. e iPSF alignment with and without POPE attachment, evaluated using intensity correlation quotient (ICQ ≈ 0.4) and Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC ≈ 0.8), with overlaid iPSF images in false color (white and black) for clarity.

The fluorescence captured by the secondary objective is relayed through a 4f optical system, consisting of the secondary objective (serving as the first lens, focal length) and a compound lens (focal length ), spaced apart (Fig. 1b). This 4f system performs a Fourier transform with the first lens, mapping the input field’s spatial frequencies to an intermediate Fourier plane, followed by an inverse Fourier transform with the second lens, reconstructing the field at the output plane14,15 (Fig. 1b). This telecentric arrangement ensures the wavefront’s spatial integrity, channeling the recaptured fluorescence to a flat dielectric mirror with > 99.99% reflectivity across the emission spectrum (Fig. 1a). Upon reflection, the light retraces its path through the 4f system, passes through the primary objective below, and merges with the downward-emitted fluorescence at the detector. This creates a cascaded dual-4f system: the initial 4f inverts the field from to and the second reinverts it to , preserving the field’s amplitude and phase profile up to a constant scaling and a global phase factor (Fig. 1b, “Methods”). Since imaging typically measures intensity , these global factors are inconsequential, ensuring full recovery of without information loss under ideal conditions—no aberrations, scattering, or filtering14–16 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S1). This closed-loop design delivers diffraction-limited images, uniform across focal planes and lateral positions, and even maintains sharpness for objects within the depth of field but slightly off-focus, enhancing POPE’s versatility (Supplementary Fig. S1).

A long-pass filter, angled strategically between the lenses (Fig. 1a), blocks excitation light to prevent unintended double excitation from reflected beams, isolating emission signals by rejecting shorter-wavelength photons and boosting the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). If this filter is removed, POPE could potentially be adapted into a 4Pi-like interferometric system, allowing coherent excitation from both objectives at the focal plane, which may enhance axial resolution17 (see Discussion). POPE also shares conceptual similarities with dual-objective multifocal plane microscopy (dMUM)18, as both use opposing objectives to improve photon collection. However, while 4Pi and dMUM systems use dual objectives for interference-based resolution enhancement or simultaneous multi-plane detection, respectively, POPE integrates dual objectives with a 4f system and a reflective mirror to redirect otherwise lost photons back into a single optical path. This approach enhances collection efficiency without requiring interferometric alignment, dual-channel detection, or complex image registration.

Calibration and alignment of the POPE microscope using fluorescent beads

The POPE microscope boosts fluorescence imaging by doubling photon collection efficiency, achieved through meticulous alignment of signals from opposing objectives—lower (original) and upper (POPE)—using a high-reflectivity dielectric mirror and a dual-4f optical system. This design aligns the upper objective’s image with the lower’s, verified by superimposing their point spread functions (PSFs): the original PSF from direct emission and the reflected PSF from the POPE path. Calibration employed 100-nm TetraSpeck™ Microspheres (0.1 nM), chosen for their sub-diffraction size, well below the system’s diffraction limit, ensuring precise PSF characterization.

Calibration started with the lower objective as the reference. A single bead was focused using the excitation laser, and a 3D fluorescence stack (x, y, z) was captured over a 20-µm axial range in 20-nm steps with a piezo stage, defining the reference PSF. The upper POPE objective, matching the lower’s NA and optical properties, was coarsely aligned using precision stages to approximate optical axis collinearity. Both objectives imaged the bead simultaneously, with lateral alignment achieved by adjusting the upper objective’s x-y position until the PSFs merged into a single spot in the focal plane, observed live. Axial alignment refined the upper objective’s z-position using dual-objective z-stacks, ensuring symmetric intensity profiles along the optical axis (Fig. 1c, d).

Fine alignment enhanced PSF quality and field consistency. A high-resolution 3D stack (35 µm × 35 µm × 20 µm) was recorded with both objectives active, and the combined PSF was analyzed for asymmetry or excessive sidelobes—indicators of misalignment. Iterative adjustments to the upper objective’s position (x, y, z) maximized symmetry and minimized PSF width, validated across multiple beads and field positions. Illumination PSFs (iPSFs) were measured for size, shape, and center offset, with results detailed (Fig. 1c–e).

To quantify PSF performance, we modeled it as a 3D Gaussian, , where is amplitude, is the center, and define spread19. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) was calculated as . No-POPE iPFS exhibited a lateral FWHM of ~296 nm and an axial FWHM of ~1160 nm (580-nm emission, NA 1.0). With PSF center offsets () <100 nm, the combined POPE iPSF showed a slight broadening to <320 nm laterally and <1200 nm axially due to incoherent intensity addition, yet retained up to twofold higher peak intensity from enhanced photon collection. Lateral and axial profiles confirmed matched shapes with amplified peaks for the combined PSF (Fig. 1c–e).

Alignment accuracy was confirmed using the intensity correlation quotient (ICQ ≥ 0.4) and Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC ≥ 0.8), indicating strong PSF overlap despite minor offsets20–22 (Fig. 1e, “Methods”). This systematic process—coarse alignment, precise fine-tuning, and quantitative validation—ensured accurate PSF superposition. Consequently, the POPE microscope maximized photon collection efficiency and maintained uniform field quality, establishing it as a highly precise fluorescence imaging tool.

Acquisition sensitivity and localization precision of super-resolution STORM improved by POPE microscopy

The efficacy of SMLM hinges on two interdependent parameters: localization precision and acquisition sensitivity11–13,23. Localization precision quantifies the accuracy with which the position of a single fluorophore is determined, directly influencing the spatial resolution of the reconstructed image. Acquisition sensitivity, conversely, reflects the imaging system’s ability to detect and record faint fluorescence signals from individual molecules, ensuring reliable data capture even at low photon yields. Both parameters critically depend on the photon budget—the total number of photons collected per fluorophore. A robust photon budget enhances localization precision by reducing positional uncertainty and boosts sensitivity by improving signal detection, whereas a constrained photon budget degrades both, compromising image quality.

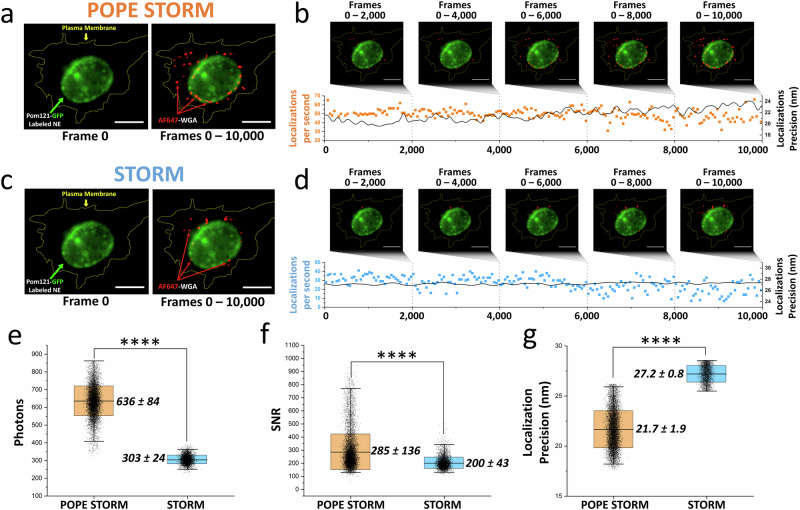

To assess POPE’s impact on SMLM, we integrated POPE microscopy with STORM, a widely used SMLM technique12,24 and performed a comparative analysis against conventional STORM (Fig. 2). Our experimental design employed Alexa Fluor 647-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-AF647) to tag glycoproteins on the plasma membrane of fixed cells, a versatile marker also suited for tissue staining and western blotting (Fig. 2a). As a structural reference, EGFP-POM121 labeled nuclear pore complexes (NPC), delineating the nuclear envelope with high specificity25 (Fig. 2a–d). Analyzing 5000–10,000 localizations across 50 labeled cells, POPE-STORM doubled the photon yield per localization—from ~300 photons in conventional STORM to ~600 photons—achieving an ~200% photon budget increase. This enhancement boosted the SNR by ~1.4-fold and localization precision by ~1.3-fold (Fig. 2e–g). The enhanced photon budget also heightened acquisition sensitivity, allowing detection and fitting of diffraction-limit fluorescent spots too dim for conventional STORM’s thresholds, nearly doubling the number of localizations (Fig. 2b, d). Thus, POPE microscopy amplifies STORM’s capabilities, offering a powerful tool for nanoscale biological imaging with superior precision and sensitivity.

Fig. 2. Enhanced STORM imaging with POPE microscopy.

a Widefield image showing GFP-labeled nuclear envelope (green) marked by NPC scaffold protein POM121 and the plasma membrane (dotted yellow line) at frame 0, alongside POPE-STORM reconstruction of Alexa Fluor 647-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-AF647) (red) localizations from 10,000 frames in a HeLa cell. b Graph of POPE-STORM localizations per second (orange points, left y-axis) and average localization precision (black line, right y-axis). c Widefield image and STORM reconstruction without POPE attachment, depicting WGA-AF647 localizations at frame 0 and across 0–10,000 frames in a HeLa cell. d Graph of STORM localizations per second (blue points, left y-axis) and average localization precision (black line, right y-axis). e Comparison of signal photon counts. f Comparison of signal-to-noise ratios. g Comparison of localization precision between POPE-STORM (orange) and conventional STORM (blue), with P values from two-sided Welch’s t test (****P = 1 × 10−4). Scale bar: 5 µm.

POPE microscopy enhances confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) performance

Having demonstrated POPE microscopy’s ability to advance super-resolution techniques, we explored its potential to improve conventional microscopy, starting with CLSM26 (Fig. 3a). CLSM is a cornerstone of fluorescence imaging, leveraging a pinhole to reject out-of-focus light for high contrast and optical sectioning26,27. However, its performance is often constrained by limited photon collection efficiency. The POPE module, designed to double photon capture through dual-objective signal alignment, offers a promising solution to enhance CLSM’s sensitivity and image quality. To evaluate this, we integrated POPE with CLSM (POPE-CLSM) and tested its performance using two model systems: TetraSpeck Microspheres in aqueous solution and HeLa cells labeled with EGFP-conjugated anti-β-actin antibodies (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Enhanced confocal microscopy with the POPE attachment.

a Simplified optical diagram of confocal microscopy, illustrating the excitation light (blue) and reflected POPE emission (orange). POPE emission is attenuated by an emission or pinhole aperture. b Comparison of TetraSpeck microspheres and HeLa cells labeled with β‐actin 48 antibody and EGFP, imaged with and without the POPE attachment, and normalized to the conventional confocal image. c Box‐whisker plot of normalized mean intensity from (b), with conventional confocal microscopy shown in blue and POPE confocal microscopy shown in orange. P values determined by two‐sided Welch’s t test (****P = 1 × 10−4). Scale bars: TetraSpeck microspheres, 2 µm; cell samples, 20 µm.

TetraSpeck™ Microspheres, uniform fluorescent beads with multiple excitation/emission bands, served as a standardized sample to quantify intensity gains in a controlled, isotropic environment28. HeLa cells, expressing EGFP-tagged β-actin, provided a biologically relevant testbed, reflecting the complexity of cytoskeletal structures in fixed cellular samples29. Imaging was performed under identical conditions (e.g., laser power, pinhole size, scan speed) with and without the POPE module, ensuring direct comparability (see “Acquisition order” in “Methods”). Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity, normalized to the conventional CLSM baseline, revealed substantial improvements with POPE-CLSM. For TetraSpeck™ Microspheres, intensity increased by ~1.8-fold across the bead volume, while in HeLa cells, it rose by ~1.9-fold throughout the actin network (Fig. 3c). These gains highlight POPE-CLSM’s ability to boost photon collection, markedly improving fluorescence sensitivity and image quality in photon-limited confocal applications.

POPE microscopy enhances detection in epifluorescence and autofluorescence microscopy

To extend the POPE module’s utility beyond super-resolution and confocal techniques, we investigated its ability to enhance epifluorescence and autofluorescence microscopy30,31, capitalizing on its design to boost photon collection efficiency (Fig. 4a, b). Epifluorescence microscopy, a prevalent widefield method, uses uniform illumination and emission filters to detect fluorescence but often suffers from limited photon capture, reducing sensitivity31. Autofluorescence microscopy, which relies on weak intrinsic fluorescence from endogenous molecules without external labels, faces even greater challenges due to low signal strength30. By integrating the POPE module into a standard inverted microscope, we aimed to quantify its enhancement of signal detection in both modalities, testing biologically relevant samples to measure gains in intensity and sensitivity.

Fig. 4. Enhanced epifluorescence and autofluorescence microscopy with the POPE attachment.

a Simplified optical diagram of the POPE microscopy experimental setup for epifluorescence and autofluorescence microscopy, depicting the excitation light (blue) and POPE emission (orange). b Illustration of the sample for epifluorescence and autofluorescence microscopy, with and without fluorescent labeling, respectively. c Epifluorescence image of the HeLa EGFP-POM121 cell and POPE epifluorescence image of Alexa Fluor 647-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA‐AF647), along with a merge of the two images. d Z‐projection of the WGA‐AF647 channel in the POPE epifluorescence image. e Epifluorescence image of the HeLa EGFP-POM121 cell and epifluorescence image of WGA‐AF647 without the POPE attachment, along with a merge of the two images. f Z‐projection of the WGA‐AF647 channel in the epifluorescence image without POPE. Images (e, f) are normalized to their backgrounds. g Normalized mean intensity from the WGA‐AF647 channel for POPE epifluorescence (orange) and conventional epifluorescence (blue). h POPE autofluorescence collected with the POPE attachment. i Autofluorescence without the POPE attachment, acquired from wild-type HeLa, wild-type MCF‐7, wild-type NIH/3T3, and wild-type DLD‐1 samples. j Normalized mean intensity for POPE autofluorescence (orange) and conventional autofluorescence (blue) microscopy from wild-type HeLa, wild-type MCF‐7, wild-type NIH/3T3, and wild-type DLD‐1 samples. P values determined by two‐sided Welch’s t test. ****P = 1 × 10−4). Scale bar: 5 µm.

For epifluorescence, we imaged HeLa cells expressing EGFP-POM121 (a nuclear pore complex marker) and labeled with WGA-AF647 to highlight plasma membrane glycoproteins32 (Fig. 4c, d). Imaging conditions—excitation wavelength, filter sets, and exposure time—were kept identical between conventional and POPE-enhanced setups for direct comparison (see “Acquisition order” in “Methods”). Normalizing fluorescence intensities to the conventional epifluorescence baseline, POPE increased signal by ~1.5-fold across both EGFP (green) and Alexa Fluor 647 (red) channels (Fig. 4d–g). This gain stems from POPE’s dual-objective system, which doubles the solid angle of light collection, recovering photons lost in a single-objective configuration. The uniform enhancement across distinct emission spectra (509 nm for EGFP, 665 nm for Alexa 647) highlights POPE’s versatility.

In autofluorescence microscopy, we examined four label-free wild-type cell lines—HeLa, MCF-7, DLD-1 (human-derived), and NIH-3T3 (mouse-derived)—cultured under standard conditions (Fig. 4h, i). Excitation at 488 nm elicited intrinsic fluorescence from endogenous fluorophores (e.g., flavins), with emission collected at 500–550 nm. After normalizing to the conventional autofluorescence baseline, POPE-enhanced imaging produced mean intensity increases of ~1.5-fold for HeLa and MCF-7 cells and ~1.3-fold for DLD-1 and NIH-3T3 cells. These differences likely reflect variations in autofluorescent molecule concentration and cell thickness, with HeLa and MCF-7 cells—known for elevated metabolic activity—emitting stronger basal signals that POPE amplifies more effectively. Background noise levels remained stable, suggesting that the intensity gains translate to improved SNR.

These results show that POPE microscopy markedly enhances detection sensitivity in both epifluorescence and autofluorescence modalities. By boosting the photon budget without altering the PSF or requiring extensive hardware changes beyond the module, POPE elevates the performance of conventional widefield systems. This enhancement is especially valuable for imaging faint signals, such as those in label-free or sparsely labeled samples, establishing POPE as a versatile, transformative tool across a wide range of fluorescence microscopy applications. In contrast to the substantial enhancements achieved with POPE-STORM and POPE-CLSM, the more modest gains in photon collection efficiency observed in epifluorescence and autofluorescence are more sensitive to sample-dependent factors—such as thickness, scattering, and absorption—as well as the specific excitation and emission wavelengths used (see “Discussion”).

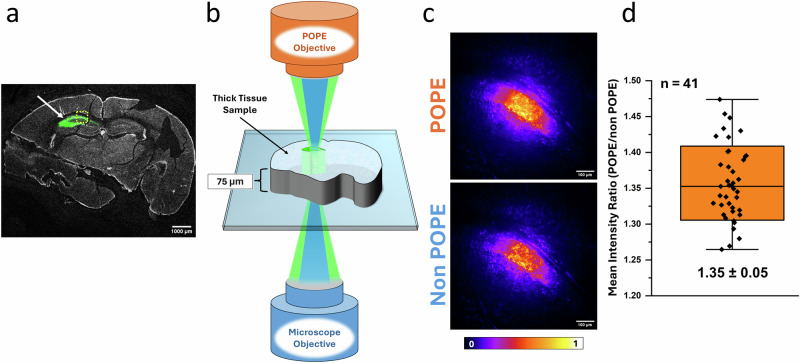

POPE microscopy enhances thick tissue imaging

Fluorescence microscopy of tissues thicker than 50 µm faces major optical hurdles—light scattering, absorption, and autofluorescence—that degrade image quality and limit penetration depth far more than in thinner samples like single cells33–35. Scattering disperses excitation and emission light, reducing signal collection, while absorption attenuates photons, particularly at greater depths. Autofluorescence from endogenous molecules further obscures specific fluorescence, lowering the SNR36. To assess the POPE module’s ability to address these challenges, we imaged 75-µm-thick mouse brain slices expressing EGFP in the hippocampal CA1 region, a model system with complex three-dimensional structure36–38 (Fig. 5a, b). Using 488-nm excitation and collecting emission at 500-550 nm, fluorescent images of the thick tissue sample were taken with and without the POPE module under identical acquisition parameters (Fig. 5c). Quantitative pairwise analysis of these images showed that POPE increased collected photons by ~1.35-fold (Fig. 5d), demonstrating enhanced photon capture from deeper tissue layers.

Fig. 5. POPE imaging of mouse brain slices.

a Confocal image of an example mouse brain slice used as the thick tissue model. The mouse was injected unilaterally with an AAV-5 hsyn-EGFP virus in the dorsal CA1 region of the hippocampus. The tissue was fixed for 24 h in 4% PFA, floated in sucrose, and sliced on a cryostat. White arrow indicates EGFP-containing hippocampal region. The yellow box indicates approximate region imaged in (c). Magnification is ×1.25. Scale bar: 1000 µm. b Simplified diagram showing the thick tissue sample (~75 μm thick) imaging with POPE microscopy. c Epifluorescent images taken with (top) and without (bottom) the POPE module. Intensity scale bar shows relative intensity per pixel. Magnification is ×10. Scale bar: 100 µm. d Comparing the POPE/no POPE mean intensity ratios of each of the 41 image pairs analyzed. POPE increased photon collection by around 35%. Images were taken across six identically prepared brain slices. The value is presented as median ± SD. Analysis ROI was determined using a 1% threshold of the POPE − no POPE difference image. The box range indicates standard deviation (SD), and the 99% confidence interval (CI) is shown with black error bars.

This enhancement is driven by POPE’s dual-objective design, which effectively doubles the solid angle of photon collection. In thick specimens, where emitted photons scatter widely and conventional single-objective systems capture only a small fraction (e.g., ~10–20% at 75 µm due to isotropic emission and optical aberrations)39,40, POPE’s secondary objective recovers a substantial amount of otherwise lost fluorescence. The resulting increase in the photon budget not only enhances overall signal intensity but also improves the SNR by selectively amplifying EGFP fluorescence over background autofluorescence—without requiring optical clearing or sample thinning. Together, these advantages establish POPE as a broadly applicable upgrade to fluorescence microscopy, enabling high-sensitivity imaging across sample types—from solutions and single-cell monolayers to complex three-dimensional biological structures.

Discussion

POPE microscopy enhances fluorescence imaging by integrating a 4f optical system and a reflective mirror opposite the objective in an inverted microscope. This configuration redirects a substantial portion of photons that are typically lost in single-objective setups, effectively increasing photon collection efficiency. Compatible with multiple imaging modalities—including STORM, CLSM, epifluorescence, and label-free autofluorescence—POPE improves sensitivity, spatial resolution, and acquisition speed under photon-limited conditions. As a modular add-on, it upgrades existing inverted microscopes without requiring major hardware modifications. Its performance has been validated across a wide range of biological samples, from fluorophore solutions and subcellular structures to live cells and thick tissues, supporting applications from single-molecule imaging to volumetric tissue analysis.

As demonstrated across a range of sample types, the photon collection efficiency of POPE microscopy is highly dependent on both sample-specific properties—such as thickness, scattering, and absorption—and optical parameters, including the excitation pattern and the excitation/emission wavelengths used during imaging. In optically transparent media, such as aqueous buffer or fixed cells, POPE achieves near-maximal photon recovery. For example, in super-resolution applications like POPE-STORM, photon collection efficiency approaches ~200%, as spatially or temporally isolated fluorophores emit photons that are symmetrically collected through both objectives with minimal scattering or attenuation.

In confocal implementations such as POPE-CLSM, the system attains up to ~190% efficiency when scanning near the diffraction limit using pinhole-filtered illumination. The confocal architecture inherently suppresses out-of-focus background, allowing POPE to maximize the collection of in-focus fluorescence while minimizing spurious signals from out-of-plane excitation. Given that STED microscopy builds upon the confocal framework by introducing a donut-shaped depletion beam for sub-diffraction imaging, POPE may also be compatible with STED systems. Its non-invasive optical path and lack of focal-plane interference suggest that, with appropriate spectral filtering—such as a high-performance notch filter to reject the excitation and depletion laser lines—POPE could similarly enhance fluorescence collection in STED imaging.

In wide-field modalities like POPE-epifluorescence, the photon collection efficiency in live cultured HeLa monolayers (~8–10 µm thick) reaches ~150%. Although uniform illumination combined with dual-objective detection markedly improves signal recovery, the overall efficiency is somewhat reduced by increased light scattering and absorption caused by heterogeneous subcellular structures of varying sizes and refractive indices. As sample thickness and structural complexity increase, collection efficiency declines further. For instance, in thick tissue sections such as fluorophore-labeled mouse brain slices (~75 µm thick), POPE achieves a collection efficiency of ~135%. This drop is primarily attributable to elevated scattering and absorption with depth—especially at shorter wavelengths—consistent with Rayleigh scattering, which scales inversely with the fourth power of wavelength (~1/λ4)41.

In label-free live-cell autofluorescence imaging, efficiency further decreases to ~125%. This reduction is due to the intrinsically weak signals from endogenous fluorophores (e.g., NADH, FAD), which emit in the blue-green spectral range (~440–540 nm) and are often accompanied by substantial background noise. Moreover, the use of short-wavelength or ultraviolet excitation—necessary to excite these fluorophores—results in poor tissue penetration and heightened scattering and absorption, particularly from intracellular chromophores such as flavins and cofactors in mitochondrial enzymes42,43.

To mitigate these constraints in thick samples, we propose adapting POPE for two-photon or multi-photon excitation, which restricts fluorophore activation to the focal plane, minimizing out-of-focus scattering and absorption44. Two-photon excitation, employing longer wavelengths (e.g., 800–950 nm vs. 488 nm single-photon EGFP excitation), reduces scattering and enhances penetration by evading high-absorption bands (e.g., hemoglobin peaks at <600 nm)45. Its quadratic intensity dependence also sharpens the excitation PSF, concentrating signal44. This adaptation would greatly extend POPE’s reach for deep-tissue imaging, making it well suited for intact organoids, whole-mount embryos, or brain slices where single-photon methods struggle. Nonetheless, fluorescence reflected toward the lower objective undergoes additional scattering, reducing collection efficiency. In such cases, incorporating a second detector above the sample could enhance photon capture and improve signal fidelity in highly scattering specimens18.

While POPE currently emphasizes photon collection over interference-based enhancements, its architecture supports future innovations. Analogous to 4Pi microscopy, removing the long-pass filter and optimizing the optical path could enable interference between excitation beams from opposing objectives, potentially reducing the axial PSF to ~100–150 nm through coherent superposition17. Adding a phase modulator could further refine PSFs, enhancing axial resolution, correcting aberrations, or enabling 3D super-resolution46–48. Although these modifications promise resolution gains, they require further alignment and are reserved for future development. Here, we prioritize POPE’s immediate advantage: amplifying the photon budget. This alone markedly elevates existing techniques—doubling STORM’s signal for sharper localization, boosting confocal SNR for clearer optical sections, and enhancing faint autofluorescence for label-free imaging—opening new research frontiers, from real-time molecular imaging in cultured cells to detailed mapping of thick-tissue architectures with minimal sample alteration.

Methods

POPE microscopy system overview

The POPE microscopy system is built on an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope, equipped with multiple solid-state lasers (Coherent OBIS, 50 mW) at 405 nm, 488 nm, 520 nm, 561 nm, and 631 nm for excitation. It features either a Cascade 128 + CCD camera (Photometrics) or an iXon Ultra 897 EMCCD camera (Andor, Oxford Instruments) for detection, with data acquisition managed by Slidebook (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) or Solis Software (Andor, Oxford Instruments). To integrate the POPE module, the microscope’s condenser arm is replaced with a custom POPE attachment assembly. This assembly comprises, from top to bottom: an end cap for the lens tube, a lens tube, a broadband dielectric mirror, a stress-free retaining ring, an achromatic doublet lens, a translational stage, a connector linking the stage to the lens tube, a long-pass filter (Semrock, Inc.), silicone gaskets for tilt adjustment (Bellco Glass, Inc.), another stress-free retaining ring, and a matched POPE objective (Olympus). Unless otherwise noted, components are sourced from Thorlabs, Inc. The system employs two objective configurations: a pair of Olympus ×60 water-dipping objectives (NA = 1.0) for STORM, epifluorescence, and autofluorescence imaging, and a pair of Olympus ×10 objectives (NA = 0.3) for confocal microscopy and thick-tissue imaging. Image analysis is conducted using Fiji (ImageJ), except for single-molecule localization, which adheres to protocols outlined in “The localization precision for fluorescent particles.”

STORM sample and imaging

STORM image analysis is conducted using the ThunderSTORM plugin in Fiji. For sample preparation, HeLa cells are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, Penicillin, and Streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator. Transfected cells are fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and cytoplasmic and nuclear membranes are identified using bright-field images and the ImageJ particle picker plugin.

POPE–confocal microscopy

For confocal applications, the POPE attachment replaces the condenser lens assembly on a Leica DMi8 laser scanning confocal microscope, equipped with a galvanometer stage and HyD detectors. Samples, including TetraSpeck™ Microspheres (0.1 μm) and mCherry-POM121-expressing cells stained with Alexa fluor 488 against actin, are scanned through the focal plane using a galvanometer-equipped sample stage. Images are captured with and without obstructing the POPE assembly, and the mean intensity increase across the focal plane is compared to assess performance.

Dual 4f system

In a dual 4f optical system, an object represented by its input field is fully recovered after passing through two consecutive setups, each comprising two lenses of focal length separated by . The first 4f system performs a Fourier transform followed by an inverse Fourier transform, yielding an intermediate image at its output plane. This inversion arises from the imaging geometry of the lens pair. Under ideal, paraxial conditions, the field may also acquire a global phase factor (e.g., eiϕ) due to lens-induced quadratic phase terms and propagation. Here, i denotes the imaginary unit (i2 = −1), and ϕ represents the phase angle in radians. However, this factor is spatially uniform and does not affect the image structure. This intermediate field then serves as input to the second 4f system, which applies the same transformations, inverting the coordinates again and introducing another identical phase factor. As a result, the final field is up to a constant complex phase , with no spatial distortion or loss of information. Since fluorescence imaging typically measures intensity , which is invariant to global phase shifts, the original object field is effectively and fully recovered, assuming ideal optics and no filtering at the Fourier planes.

Evaluation of PSF overlap using the ICQ

To assess the spatial overlap of the original and combined PSFs in the POPE microscope, we employed the ICQ as a robust metric for co-variation. Three-dimensional fluorescence stacks (35 µm × 35 µm × 20 µm, 20-nm z-steps) were acquired simultaneously from the lower (original) and upper (POPE) objectives imaging 100-nm Rhodamine-labeled beads, using a 580-nm emission filter and NA 1.0 objectives. For each pair of PSF images, pixel intensities (without POPE) and (with POPE) were extracted after background subtraction (rolling-ball algorithm, radius 50 pixels). The ICQ was calculated as , where is the total number of pixels, and are mean intensities of the perspective PSFs, and the sign function counts positive (co-varying) versus negative (anti-varying) deviations, normalized to [−0.5, 0.5]. Values were computed over a 5 µm × 5 µm × 5 µm region centered on the PSF peak, ensuring focus on the bead’s signal. An ICQ threshold of 0.4 was set to confirm robust overlap (Fig. 1e), with results averaged across 10 beads, indicating strong spatial alignment despite minor center offsets (<100 nm).

Evaluation of PSF overlap using the PCC

To quantify the linear similarity and shape agreement between the original and reflected PSFs, we utilized the PCC as a complementary metric. Fluorescence stacks were acquired as described above, with intensities and extracted from the lower and upper objectives, respectively, post-background subtraction. The PCC was computed as , where and are pixel intensities, and are means, and is the pixel count within a 5 µm × 5 µm × 5 µm region centered on the PSF. Prior to calculation, intensities were normalized to their maximum values to account for potential scaling differences due to POPE’s enhanced collection efficiency. A PCC ≥0.8 was targeted to verify near-perfect overlap, with results averaged over 10 beads, reflecting high shape fidelity and alignment precision. Deviations from unity were analyzed for asymmetry or sidelobe contributions, cross-checked with lateral and axial PSF profiles (Fig. 1e), confirming the system’s diffraction-limited performance.

The localization precision for fluorescent particles

For immobilized fluorophores, the fluorescent spots were fitted to a 2D elliptical Gaussian function, and the localization precision was determined by the s.d. of multiple measurements of the centroid position. However, for moving molecules, the diffusion of the particle during image acquisition must be accounted. The localization precision for moving substrates (σ) was determined by the algorithm , where F is equal to 2, N is the number of collected photons, a is the effective pixel size of the detector, and b is the s.d. of the background in photons per pixel, and , where s0 is the s.d. of the PSF in the focal plane, D is the diffusion coefficient of substrate, and Δt is the image acquisition time.

Preparation of thick tissue samples

The Institutional Animal Care Use Committee of Temple University approved all animal studies. Stereotaxic injections were performed on mice aged P28 ± 1. Under isoflurane anesthesia, the skull was exposed via scalp incision, and a hole was drilled to afford access to the brain. Mice were injected unilaterally with 0.2 μL of pAAV5.hSyn.eGFP.WPRE.bGH into the dorsal CA1 subregion of the hippocampus; coordinates from bregma: +/−1.4 ML, −1.95 AP, −1.15 DV. Meloxicam was administered subcutaneously post-surgery, and 2 days after. Mice were given 2 weeks post injection to allow for EGFP expression, at which time mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and brains removed. The brains were submerged in 4% PFA for 24 h, followed by 72 h submerged in 30% sucrose solution. Brains were mounted in cryogenic solution and frozen at −80 °C and sliced on a cryostat.

Acquisition order

To minimize the effects of photobleaching during sequential imaging, we alternated the acquisition order: the no-POPE condition was imaged first in half of the measurements, and the POPE condition was imaged first in the other half. Results were then averaged across all image pairs to reduce bleaching-related bias.

Simulation

Simulations were carried out using Python 3.9. The simulations involving the interpolation of curves made use of the SciPy32 and NumPy33 modules to perform operations such as convolution, addition, or multiplication of probability density functions. Convolution was executed using the fast Fourier transform function provided by SciPy. Simulation scripts can be accessed at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/YangLabemple/Master/tree/master/POPE%20Microscopy/Simulations.

Statistical analysis

STORM and POPE-STORM data were analyzed from 5000 to 10,000 localizations per condition across 50 cells. CLSM experiments (with and without POPE) included hundreds of beads and over 50 cells. For epifluorescence and autofluorescence, more than 200 cells were analyzed. In thick samples, POPE vs. non-POPE intensity ratios were calculated from over 40 image pairs. Two-sided Welch’s t tests were used to assess significance. Data are reported as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (GM122552 and CA279681 to W.Y).

Author contributions

W. Yang and A. Ruba conceived the study and designed the experiments. A. Ruba, S. L. Junod, M. Tingey, and C. Rush performed the experiments. S. L. Junod, M. Tingey, C. Rush, A. Ruba, and W. Yang analyzed the data and prepared the figures. J. Saredy and W. E. Brew contributed to facility assessment and sample preparation. W. Yang, M. Tingey, C. Rush, and S. L. Junod drafted the manuscript. W. Yang, M. Tingey, and C. Rush revised and finalized the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Nikola Krstajić, Luca Lanzanò, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Wenjie Wang and Rosamund Daw. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Python scripts for data analysis are available at https://www.github.com/YangLab-Temple.

Competing interests

POPE microscopy is protected under U.S. Patent No. 12,282,147 B2, titled “Method and System for Enhanced Photon Microscopy,” with Weidong Yang and Andrew Ruba listed as inventors. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Mark Tingey, Andrew Ruba, Samuel L. Junod.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s44172-025-00491-6.

References

- 1.Limpouchová, Z. & Procházka, K. in Fluorescence Studies of Polymer Containing Systems 91–149 (Springer, 2016).

- 2.Leathem, A. J. & Brooks, S. A. in Lectin Methods and Protocols 3–20 (Springer, 1998).

- 3.Murphy, D. B. & Davidson, M. W. Fundamentals of Light Microscopy and Electronic Imaging (Wiley, 2012).

- 4.Lacey, A. J. (ed.) Light Microscopy in Biology: A Practical Approach, Vol. 195 (OUP, 1999).

- 5.Eriksson, F. On the measure of solid angles. Math. Mag.63, 184–187 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bancroft, J. D. & Floyd, A. D. in Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques 37–68 (Elsevier, 2012).

- 7.Hein, B., Willig, K. I. & Hell, S. W. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) nanoscopy of a fluorescent protein-labeled organelle inside a living cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA105, 14271–14276 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett.19, 780–782 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerra, J. M. Super‐resolution through illumination by diffraction‐born evanescent waves. Appl. Phys. Lett.66, 3555–3557 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Diezmann, L., Shechtman, Y. & Moerner, W. E. Three-dimensional localization of single molecules for super-resolution imaging and single-particle tracking. Chem. Rev.117, 7244–7275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rust, M. J., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) provides sub-diffraction-limit image resolution. Nat. Methods3, 793 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science313, 1642–1645 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang, W. & Ruba, A. Methods and system for enhanced photon microscopy. US patent 17/780,044 (2022).

- 14.Mondal, P. P., Diaspro, A., Mondal, P. P. & Diaspro, A. in Fundamentals of Fluorescence Microscopy: Exploring Life with Light 3–31 (Springer, 2014).

- 15.Goodman, J. W. Introduction to Fourier Optics (Roberts and Company Publishers, 2005).

- 16.Mertz, J. Introduction to Optical Microscopy (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- 17.Hell, S. W., Stelzer, E. H., Lindek, S. & Cremer, C. Confocal microscopy with an increased detection aperture: type-B 4Pi confocal microscopy. Opt. Lett.19, 222–224 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ram, S., Prabhat, P., Ward, E. S. & Ober, R. J. Dual objective fluorescence microscopy for single molecule imaging applications. Proc. SPIEInt. Soc. Opt. Eng. 7184, 71840C (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Parent, A., Morin, M. & Lavigne, P. Propagation of super-Gaussian field distributions. Opt. Quantum Electron.24, S1071–S1079 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn, K. W., Kamocka, M. M. & McDonald, J. H. (2011). A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300, C723–C742 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Adler, J. & Parmryd, I. Quantifying colocalization by correlation: the Pearson correlation coefficient is superior to the Mander’s overlap coefficient. Cytom. A77, 733–742 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garren, S. T. Maximum likelihood estimation of the correlation coefficient in a bivariate normal model with missing data. Stat. Probab. Lett.38, 281–288 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lelek, M. et al. Single-molecule localization microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim.1, 39 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heilemann, M. et al. Subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging with conventional fluorescent probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 6172–6176 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Funakoshi, T., Clever, M., Watanabe, A. & Imamoto, N. Localization of Pom121 to the inner nuclear membrane is required for an early step of interphase nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell22, 1058–1069 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawley, J. (ed.) Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy, Vol. 236 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2006).

- 27.Nwaneshiudu, A. et al. Introduction to confocal microscopy. J. Invest. Dermatol.132, 1–5 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, Y. Z. & Carter, D. Multicolor fluorescent microspheres as calibration standards for confocal laser scanning microscopy. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol.7, 156–163 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald, D., Carrero, G., Andrin, C., de Vries, G. & Hendzel, M. J. Nucleoplasmic β-actin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between low-mobility polymeric species and rapidly diffusing populations. J. Cell Biol.172, 541–552 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monici, M. Cell and tissue autofluorescence research and diagnostic applications. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev.11, 227–256 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb, D. J. & Brown, C. M. in Cell Imaging Techniques: Methods and Protocols 29–59 (Springer, 2013).

- 32.Chazotte, B. Labeling membrane glycoproteins or glycolipids with fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc.2011, pdb-prot5623 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, T. H. & Schnitzer, M. J. Fluorescence imaging of large-scale neural ensemble dynamics. Cell185, 9–41 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilt, B. A. et al. Advances in light microscopy for neuroscience. Annu. Rev. Neurosci.32, 435–506 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Nachef, D., Martinson, A. M., Yang, X., Murry, C. E. & MacLellan, W. R. High-resolution 3D fluorescent imaging of intact tissues. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Dis.1, 1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer, M. A. Highly expressed genes within hippocampal sector CA1: implications for the physiology of memory. Neurol. Int.2014, 5388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seabrook, G. R., Easter, A., Dawson, G. R. & Bowery, B. J. Modulation of long-term potentiation in CA1 region of mouse hippocampal brain slices by GABAA receptor benzodiazepine site ligands. Neuropharmacology36, 823–830 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho, S., Wood, A. & Bowlby, M. R. Brain slices as models for neurodegenerative disease and screening platforms to identify novel therapeutics. Curr. Neuropharmacol.5, 19–33 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, Y., Christensen, R., Colón-Ramos, D. & Shroff, H. Advanced optical imaging techniques for neurodevelopment. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol.23, 1090–1097 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shan, Q. H. et al. A method for ultrafast tissue clearing that preserves fluorescence for multimodal and longitudinal brain imaging. BMC Biol.20, 77 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith, G. S. Human color vision and the unsaturated blue color of the daytime sky. Am. J. Phys.73, 590–597 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chacko, J. V. & Eliceiri, K. W. Autofluorescence lifetime imaging of cellular metabolism: sensitivity toward cell density, pH, intracellular, and intercellular heterogeneity. Cytom. A95, 56–69 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishidate, I., Maeda, T., Niizeki, K. & Aizu, Y. Estimation of melanin and hemoglobin using spectral reflectance images reconstructed from a digital RGB image by the Wiener estimation method. Sensors13, 7902–7915 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denk, W., Strickler, J. H. & Webb, W. W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science248, 73–76 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zolla, L. & D'Alessandro, A. An efficient apparatus for rapid deoxygenation of erythrocyte concentrates for alternative banking strategies. J. Blood Transfus.2013, 896537 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jouchet, P., Roy, A. R. & Moerner, W. E. Combining deep learning approaches and point spread function engineering for simultaneous 3D position and 3D orientation measurements of fluorescent single molecules. Opt. Commun.542, 129589 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quirin, S., Pavani, S. R. P. & Piestun, R. Optimal 3D single-molecule localization for superresolution microscopy with aberrations and engineered point spread functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA109, 675–679 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, W. et al. Generalized method to design phase masks for 3D super-resolution microscopy. Opt. Express27, 3799–3816 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Python scripts for data analysis are available at https://www.github.com/YangLab-Temple.