Abstract

The upper critical solution temperature (UCST) of binary polymer–solvent blends can create porous structures for many applications, including filtration. This study investigates how UCST can be tuned in a non-aqueous system of polystyrene and terpineol. The addition of small molecules, γ-valerolactone, oleic acid, and limonene, was tested to modify the terpineol-polystyrene phase separation temperature. The resulting porous structures were studied to determine the pore size, porosity, water flux, and rejection of test molecules to better understand the impact of the additives on both the processing temperature and porous materials' properties. The study found that the hydrogen bond propensity and miscibility of the additives significantly affected the UCST. A change of over 35 °C was observed when the additive concentration varied from 0 to 15 wt %, and the transition temperature increased or decreased depending on the additive solvent strength. The surface pore diameter was significantly altered, but the bulk pore diameter remained similar in all cases with the exception of oleic acid. The addition of small-molecule addives offers a way to control the UCST by tunning addities' solubilities and hydrogen bonding abilities in similar blends, toward lower energy use porous film synthesis.

Introduction

Porous materials are essential in many applications, such as cellular scaffolds, fibers, or technologies such as membranes for water or gas purification. − Numerous techniques, such as phase inversion methods, exist for synthesizing porous materials within a nanometer to micrometer pore diameter range. − Thermally induced phase separation (TIPS) is one of the techniques that can produce a porous structure which is generally symmetric across the whole material. , This phase separation can occur due to the crystallization of the polymer, solvent, a combination of both, or the critical temperature. ,

The upper critical solution temperature (UCST) phase behavior can be used to create porous structures. Below the boundary, polymers change from an extended coil shape to globules, leading to lower interactions with the solvent. Enthalpic interactions between polymer–polymer and solvent–solvent pairs primarily cause the UCST behavior. These interactions are often a result of ionic or hydrogen bonding between molecules but can also exist due to hydrophobic interactions. Examples include solvent blends such as 1,4-dioxane-water, which can be used to create polylactide foams, and systems such as cyclohexanol and polystyrene to form membranes. ,,

The UCST and its counterpart, the lower critical solution temperature (LCST), have been studied extensively in aqueous systems. Studies have found that tuning the aqueous phase by adding ions, cosolvents, pH, and concentration of those species can drastically affect the phase separation temperature. , Similar studies have also explored the use of process parameters and additives like ions, cosolvents, on the formation of porous structures from organic solvents in the TIPS process. − Song and Torkelson found that polystyrene with cyclohexanol exhibits a UCST and that changes to the resulting microstructure can be induced by tuning the cooling rate and polymer concentration, consistent with other studies. , Matsuyama et al. have explored the use of diluents in the crystallization-driven TIPS process and found that the pore size was impacted by diluents, particularly at slower cooling rates. Plisko et al. noted that the ternary system of poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(phenylsulfone)-N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone exhibited a UCST with a sensitivity to the molecular weight and concentration of poly(ethylene oxide). These studies, and a review by Akbarzadeh and Yousefi, provide a basis to further explore the use of additives on the UCST behavior of a polymer–solvent blend to provide more evidence on the mode of action involved in these processes particularly to allow for low temperature phase inversion.

Membrane science like other fields have started to show a greater emphasis on sustainability. , Sustainability in membrane synthesis can focus on different points of the process, such as solvent choice and in TIPS energy efficiency. Numerous studies have noted that green solvents such as gamma-valerolactone can generate membranes of similar properties to those with traditional more hazardous solvents such as N-methyl pyrrolidone. − In TIPS, energy efficiency can be a big problem often tied to polymer and solvent choices. To overcome this challenge in the past few years, there has also been an increasing number of publications on low-temperature thermally induced phase separation (L-TIPS). In one study a combination of nonsolvent and temperature based phase inversion led to PVDF membranes being fabricated 80 °C cooler than usual. , Other researcher instead have examined the addition of latent solvents which tuned the polymer’s solubility and noted the impact on crystallization temperature. , Further studies investigating methods to allow for lower temperature TIPS will be critical to enable a broader translation of the technique.

This study aims explore the impact of three different small molecules as additives on the UCST to develop a low temperature phase inversion membrane fabrication process which is only beginning to be explored in the literature. , In particular, we explored the synthesis of porous polystyrene membranes by describing the UCST between terpineol and polystyrene. , We hypothesized that the additives: γ-valerolactone, oleic acid, and limonene may impact the intermolecular forces required to trigger UCST behavior. The choice of these additives aligns with several green principles, such as using safer chemicals and enhancing sustainability in material design. The novelty of the work focuses on showcasing specific interactions between molecules and investigations of the resulting microstructure which were explored through a combination of experimental and computational efforts. The resulting thin films were tested as ultrafiltration membranes showing an impact on filtration as a result of surface pore distribution changes. This research provides valuable insights into the development of advanced porous materials that offer precise control over their structure. Scheme depicts the chemical structures of molecules used in the study.

1. Chemical Structures of Molecules Used in the Study.

Results and Discussion

Identification of the UCST and Shifts due to Additives

Achieving control over the upper critical solution temperature may be advantageous in extending the work to different processing conditions and temperatures. In this study, we have utilized three different additives to explore the impact on phase separation temperature and resulting microstructure. The phase transition was detected by monitoring the cloud point, which was used to determine the temperature at which phase separation occurred in additive-free and additive-containing solutions. The concentration dependence of the cloud point in a binary mixture of polystyrene with terpineol was investigated and is shown in Figure a. The obtained data, which aligned with prior findings, indicated a slight increase in the cloud point with increasing concentrations of polystyrene. , We hypothesize that the loss of sensitivity to concentration occurs due to the use of high molecular weight polystyrene in our study. At the higher concentrations tested, there are a significant number of styrene repeating units, which may saturate the interactions with terpineol to trigger the UCST behavior. When compared to the work by Song and Torkelson, we note that the terpineol system showed a UCST of approximately 20 °C lower than that of the cyclohexanol system. We hypothesize that the steric hindrance of the methyl/propyl groups in terpineol prevents the formation of strong hydrogen bonds, leading to a lower transition temperature.

1.

Phase diagram of polystyrene/terpineol mixtures. (a) Cloud point temperature of varying concentrations of polystyrene in terpineol (wt/wt). (b) Cloud point temperature of 20 (wt/wt)% polystyrene in terpineol without additive with different additives: 5, 10, and 15 (wt/wt)% limonene, γ-valerolactone, and oleic acid as the corresponding bars. All data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent samples. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test compared to the pure sample in part b, where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

The UCST was further explored by creating ternary blends of two solvents and polystyrene. The polystyrene concentration was kept at 20 wt % polystyrene to ensure the created films were mechanically robust for further analysis. The incorporation of additives into the system had significant and varying impacts on the UCST temperature (Figure b). We noted that there was no significant difference in temperature from the pure polystyrene-terpineol system during the addition of limonene. We hypothesized that up to the 15 wt/wt% tested in our study, the replacement of terpineol with limonene does not diminish the number of hydrogen bonds necessary to trigger the UCST. γ-Valerolactone, in turn, has decreased the cloud point temperature at all concentrations with the maximum drop to 28 ± 1 °C at the highest concentration of 15 w/w%. This is among the lowest transition temperature noted in L-TIPS. In comparison, oleic acid has increased the cloud point temperature to 94 ± 2 °C at the highest concentration of 15 w/w%. We hypothesize that this change occurs due to the hydrogen bond changes in the system, as both γ-valerolactone and oleic acid can participate in hydrogen bonding with terpineol, as shown in Figure S9.

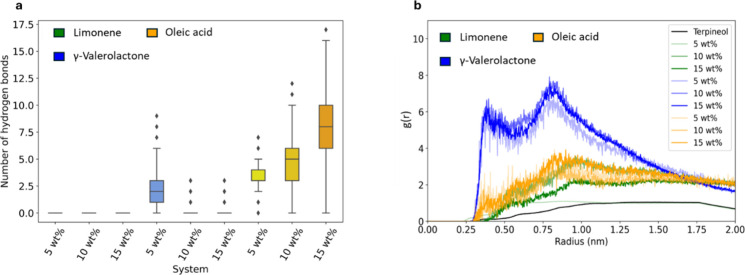

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to study the effect of additives on the polystyrene-terpineol solution, as shown in Figures and . Figure a illustrates the average number of hydrogen bonds between additives and terpineol at 303 K to understand the impact of different additives on the solution. After the addition of oleic acid, a significant number of hydrogen bonds are formed between oleic acid and terpineol. The hydrogen bonds were determined based on the criteria developed by Luzar and Chandler. A similar increase in hydrogen bonding can be seen even at low concentrations of γ-valerolactone. However, at higher concentrations of γ-valerolactone, we no longer see significant hydrogen bonding in the system. We hypothesize that the lack of hydrogen bonds is due to the simulation using a relatively low molecular weight polymer and a simulation temperature of 303 K. Both parameters could have made the simulation run above the UCST which would not allow for the formation of stable hydrogen bonds. This is unique to γ-valerolactone, as limonene did not alter the transition temperature and cannot form hydrogen bonds, while oleic acid increases the transition temperature and can form hydrogen bonds. As such, γ-valerolactone simulations at higher concentration may have occurred in a miscible state, while the rest modeled the immiscible state.

2.

Simulation results of polystyrene, terpineol, and different additives. (a) Number of hydrogen bonds between terpineol and the additive molecules. (b) Radial distribution function (RDF) between polystyrene and blend between terpineol and additives atoms.

3.

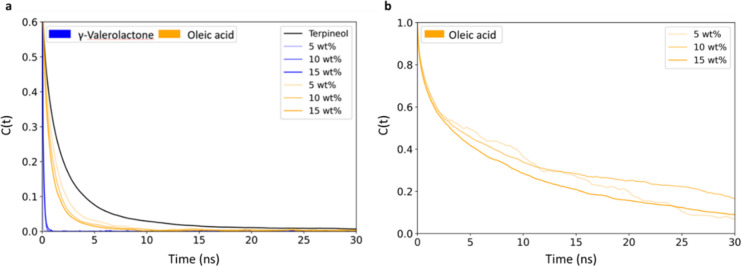

Hydrogen bond autocorrelation curve between (a) terpineol-terpineol (black) and terpineol-additive molecules and (b) oleic acid-oleic acid.

To better understand the interaction between additives in a solution, a radial distribution function (RDF) analysis of solvated polymers with different concentrations of additives was used. This analytical method proved to be highly valuable in revealing the organizational patterns of solvent molecules surrounding the solute. As shown in (Figure b), The RDF values for γ-valerolactone, oleic acid, and limonene additives are increased, demonstrating a substantial shift in the contact between solvent molecules around the polymer compared to pure polystyrene-terpineol systems. In particular, the RDF for the γ-valerolactone systems reveals prominent peaks around 0.3 and 0.8 nm. These peaks indicate that γ-valerolactone interrupts the intermolecular forces between terpineol and polystyrene molecules.

The autocorrelation function C(t) measures the persistence of hydrogen bonds over time by tracking their formation and dissociation dynamics, as shown in Figure . Steeper C(t) curves indicate more rapid bond formation and dissociation and flatter curves representing longer-lasting, more stable hydrogen bonds. The analysis shows that terpineol-terpineol hydrogen bonds exhibit the greatest stability, with a decay time of approximately 2 ns, as shown in Table S2.

Next, terpineol-oleic acid hydrogen bonds show moderate stability, with decay times ranging from 0.8 to 1.3 ns, indicating that oleic acid effectively integrates into the hydrogen bonding network without entirely disrupting terpineol-terpineol interactions. Lastly, γ-valerolactone forms the least stable hydrogen bond with terpineol, with a decay time of only 0.1 ns. This result indicates a highly dynamic interaction, consistent with its role in disrupting the intermolecular forces in the system and reducing the transition temperature. Oleic acid is capable of hydrogen bonding with itself, and these bonds are also stable, as shown by the flatter C(t) curve in Figure b.

The experimental results, combined with molecular dynamics simulations, provide a deeper understanding of the role of small-molecule additives in impacting the transition temperature. The experimental observations showed that γ-valerolactone and oleic acid significantly influenced the cloud point temperature, with γ-valerolactone lowering the transition temperature and oleic acid increasing it. The simulations corroborate these results by indicating the role of the small molecule additives in hydrogen bonding. Oleic acid forms a large number of hydrogen bonds with terpineol, as shown in Figure a, and itself as shown in Figure b strengthening the hydrogen bonding network and thereby increasing the transition temperature. On the other hand, γ-valerolactone disrupts the hydrogen bonding network, as reflected in its lower hydrogen bond stability (decay time of 0.1 ns in Table S2) and the prominent RDF peaks around 0.3 and 0.8 nm in Figure b, which indicates increased interactions with the polystyrene backbone. These interactions weaken the system’s intermolecular forces, resulting in a reduced UCST. The negligible effect of limonene on the UCST, observed experimentally, aligns with the absence of substantial hydrogen bonding or solubility differences in the simulations. Together, these findings focus on the role of additive interactions in tuning the phase separation temperature.

To test the hypothesis of the importance of hydrogen bonding and solubility on the UCST, we tested two additional molecule additives: one acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor (propylene carbonate) and the other as both a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor (isobutanol). Both molecules exhibited effects similar to those of γ-valerolactone and oleic acid, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. These results show the potential to tune the processing temperature for systems which exhibit an UCST through additive selection. Additionally, this research encourages others to take a second look at LCST/UCST systems, which may change their phase transition temperature when loaded with active ingredients, additives, etc. However, cloud point alone does not provide information about the structural changes occurring in the system. Therefore, membrane synthesis was required to assess the impact of additives on the structure.

Impact of the Additives on the Resulting Microstructure

To assess the impact of the additives on the resulting microstructure, we cast and evaluated the porous films using SEM. The top surface and cross sectional images shown in Figure , demonstrate porous structures with circular pores, similar to other studies. ,, Interestingly, using a backing support during membrane fabrication resulted in smaller pore sizes than those cast directly on a glass plate (Figures S2 and S3). This can be attributed to the faster cooling rate facilitated by the thinner backing material than glass which speeds up phase separation and, thus, creates smaller pores. The casting process was consistent across all additives, with solutions heated to 100 °C and cast at approximately 65 °C. These temperatures were carefully chosen to ensure smooth membrane fabrication and reproducible results. The layered structure of the membranes was evident in the cross-sectional images of the pure and limonene samples, with a dense top layer and a more porous sublayer as shown in support information in Figure S8. In contrast, the γ-valerolactone samples lacked a distinct dense top layer. The oleic acid membranes exhibited significantly larger pore sizes due to the casting temperature selected for the study. Oleic acid samples exhibited a phase transition temperature above the casting plates temperature which triggered a phase separation prior to entering a cooling bath. This in turn allowed more time for the formation and growth of larger pores deeper within the membrane, which is consistent with findings from Song and Torkelson.

4.

SEM images of a top surface and cross-section of 20 wt % polystyrene membranes with pure terpineol (no additives) and 5 wt % of additives: limonene, γ-valerolactone, and oleic acid.

The SEM images were further analyzed by using ImageJ and MATLAB to determine pore sizes (Figure a). The analysis revealed, while significant, small overall pore size changes during the addition of γ-valerolactone and limonene. Experimentally determined miscibility and Hansen solubility calculations (RED < 1) support that γ-valerolactone and limonene additives can exist in polystyrene and terpineol-rich phases. This finding supports that the pore size should not be significantly altered by the presence of the additives, as they can be present across both phases. This hypothesis is further supported by the porosity measurements, which do not show a significant increase for most samples containing γ-valerolactone and limonene (Figure b). Oleic acid, on the other hand, is incapable of dissolving polystyrene and had longer phase seperation, so we expected that it would mainly be found in the terpineol-rich phase, which is confirmed by the increased pore size which is also in part due to longer phase seperation than other samples (Figure a). However, secondary analysis using a pycnometer indicated no significant changes in porosity with the 5 wt % additive samples (Figure S9). The gas based porosity technique found a higher porosity, approximately 70% which is due to the helium gas being able to enter both closed and partially open pores more effectively than a liquid.

5.

Relative distribution of pores in the membrane cross section of 20 wt % polystyrene membranes. (a) Additive-free sample (mean pore size: 98.9 ± 63.1 nm, median: 80.2 nm); 5 wt % limonene (mean pore size: 10.7 ± 65.5 nm, median: 90.7 nm); 5 wt % γ-valerolactone (mean pore size: 186.4 ± 170.4 nm, median: 129.3 nm); and 5 wt % oleic acid (mean pore size: 253.6 ± 330.5 nm, median: 64.1 nm). The analysis was performed on two representative images (n = >230). (B) Porosity using weight measurement. All data are presented as mean ± s.d., n ≥ 3 independent samples. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test in both a and b in comparison to the pure sample, where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. The statistical significance is indicated vs the pure samples.

The top surface pore size and pore size distribution were also investigated to determine whether the additives impacted the surface pore formation (Figure ). The control group with no additives has the smallest average surface pore size with the highest frequency of pores below 10 nm. The addition of γ-valerolactone and limonene has shifted the distribution to the larger pore size and narrowed the distribution. Γ-valerolactone has a longer tail than pure or limonene containing samples. The shift in γ-valerolactone distribution could be due to the increased solubility of γ-valerolactone in water. Oleic acid in turn yielded a low porosity top surface with a large pore size distribution. This could be due to the top surface going through a longer ripening process as the phase inversion begins before the film is placed in the cooling bath due to the contact with room temperature air.

6.

Relative distribution of pores of the top surface of 20 wt % polystyrene membranes. (a) Additive-free sample (mean pore size: 14.4 ± 9.7 nm, median: 12.1 nm). (b) 5 wt % limonene (mean pore size: 19.2 ± 4.2 nm, median: 17.5 nm). (c) 5 wt % γ-valerolactone (mean pore size: 21.6 ± 9.8 nm, median: 18.8 nm). (d) 5 wt % Oleic acid (mean pore size: 71.5 ± 30.3 nm, median: 68.8 nm). The analysis was performed on two representative images (n = >230).

Performance as Ultrafiltration Membranes

Ultrafiltration is used to separate proteins from water, among other tools for water purification. − Generally, the membrane pore size needs to be below 100 nm to be an effective material in this application, and as such the oleic acid films are not applicable in this portion of the study. Due to the porosity and the cross-section pore size similarities across all additive concentrations, we decided to study the 20 wt % polystyrene system, free from additives, and containing either 5 wt % limonene or 5 wt % γ-valerolactone. Figure shows the permeability of pure water, the molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) curve of PEG, and the rejection of bovine serum albumin (BSA) for these membranes. The similarity in water flux and BSA rejection between the pure and 5 wt % limonene membranes suggests that adding limonene does not significantly alter the membrane’s structure, supporting the data shown in prior sections. On the other hand, the presence of γ-valerolactone led to a significant increase in the permeability of the membrane and a decrease in the rejection. We believe this difference is due to the increase in average surface pore size, which consequently allows more water and protein to pass through the membrane. This observation aligns with the MWCO curves shown in Figure c, which describe solute rejection versus PEG molecular weight (M w) for membranes. The MWCO curves of the control and limonene membranes rise steeply with increasing M w, exceeding 90% rejection at 10 kDa for the pure and 20 kDa for limonene. We previously hypothesized that the increase in the pore size of γ-valerolactone samples may be due to our cold bath containing water, which is miscible with γ-valerolactone. To confirm, we cast a membrane with propylene carbonate, which is not miscible with water as a direct replacement for γ-valerolactone. However, we still saw a similar performance contradicting this hypothesis (Figure S7). It is possible that water at the surface of the membrane participates in the phase change due to water’s ability to hydrogen bond and thus alters that surface pore size. This observation emphasizes the importance of considering additives’ impact on structural characteristics and separation performance when designing membranes.

7.

Effect of additives on water flux, bovine serum albumin (BSA) rejection, and the molecular weight cutoff curve of polyethylene glycol (PEG) of 20 wt % polystyrene membranes were evaluated. The samples were prepared at a concentration of 0 wt% additives (pure), 5 wt % γ-valerolactone, and 5 wt % limonene. (a) Water flux. (b) BSA rejection. (c) Molecular weight cutoff curve of PEG. The lines are drawn to showcase the trends. All data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent samples. Two-tailed Student’s t test analyzed statistical significance in both a and b compared to the pure sample, where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study utilized the upper critical solution temperature (UCST) behavior in synthesizing porous polystyrene films. We found that hydrogen bonding and solubility of additives impacted the UCST by shifting the transition by over 30 °C. The described method to decrease the UCST by additives allows for another way to develop a low temperature TIPS process. Structural analysis of the fabricated materials using SEM demonstrated the formation of porous structures with circular pores. Water flux and solute rejection tests provided insights into the impact of additives on the membrane performance. Membranes containing γ-valerolactone exhibited higher water flux and lower solute rejection than control and limonene-containing membranes, which is attributed to the larger surface pore size. Overall, these findings exhibit the broader applicability of leveraging UCST behavior to design porous polymer membranes. The relationship among additive properties, UCST behavior, and performance provides a transferable framework for developing advanced materials across various applications, including self-response materials, membrane fabrication, and biomedical devices. In addition, the environmentally friendly nature of the additives used aligns with the growing emphasis on sustainability in various industries.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Polystyrene with an average M w of 260,000 Da was purchased from ThermoFisher and Acros Chemicals. Independent analysis of the polystyrene using gel permeation chromatography revealed a PDI of 1.758 (M w/M n) and the number molecular weight of 124,000 g/mol. Terpineol mixed isomers, methanol ≥99.8% ACS, and bovine serum albumin (M w of 66463 Da), γ-valerolactone, limonene, oleic acid, methanol, propylene carbonate, and isobutanol were purchased from VWR Life Science, Millipore-Sigma, and Fisher Scientific, and Polyethylene glycol (1,4,8) kDa were purchased from Alfa Aesar, while (10,20) kDa were purchased from Thermo Scientific, and 35 kDa was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized (DI) water with a resistivity of 18.2 mΩ/cm at 25 °C was provided by Millipore Direct-Q 3 UV Water Purification System. The nonwoven polyester fabric (0.11 mm thickness) was procured from Selecta CA and used as a backing material.

Cloud Point Measurement

The cloud points of different concentrations of polystyrene with terpineol and additives were determined visually. First, solutions at the desired concentration were created by dissolving polystyrene in the solvent blend at 110 °C. After a homogeneous solution was achieved (typically 3 days), the vial was moved into a silicone oil to control the temperature of the solution. The sample was left in a hot bath for 10 min to have a uniform temperature with a silicone oil. The experiment was started by turning off the hot plate, which began to cool the sample; the average cooling rate was 2 °C/min. Cloud points of the solutions were determined visually by noting the temperature at which the turbidity was detected.

Simulation

The simulation systems were created by placing the polymer, polystyrene (repeating unit = 25), in the center of a cubic box that would be filled with the solvent molecules. Table S1 lists the ten systems. The polystyrene, terpineol, limonene, γ-valerolactone, and oleic acid in the systems are described using all-atom models. The OPLS – AA force field generated from LigParGen − (for small molecules) and PolyParGen (for the polymer molecules) web servers was used to describe bonded and nonbonded interactions in the systems. The bonded interactions are a sum of bonds, angles, and dihedral potentials. The nonbonded interaction is a sum of van der Waals and electrostatic contributions as described by equation below.

where E ij is the potential energy between atoms i and j due to nonbonded interactions. r ij is the distance between atoms i and j, ϵ ij is the energetic parameter, σ ij is the geometric parameter, and e i is the partial charge of atom i.

The simulation of each system involves three distinct steps. First, energy minimization is performed to eliminate any close contact between atoms. The second step is a 200 ns isobaric–isothermal (NPT, P = 1 atm T = 303 K) ensemble molecular dynamics (MD) simulation with an integral step of 2 fs, aiming to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium. Third, a 200 ns canonical (NVT, T = 303 K) was conducted during which the trajectory was recorded every 50 ps. The Berendsen method is employed for temperature and pressure control during the equilibration phase, while the velocity-rescaling method is used for temperature regulation during the MD production phase. Short-range van der Waals interactions use a 1.2 nm cutoff, while the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) sum is used for long-range electrostatic interactions. All energy minimization and MD simulations for the systems were executed using the GROMACS 2022.1.

Thin Film Fabrication

The solution was kept in a hot bath at 100 °C before casting. Backing material was placed on top of the metal casting plate and taped flat. The doctor blade was placed on top of the plate, and the plate was heated by a hot plate until it reached between 65 and 70 °C. The doctor blade was set the gap to 0 by using micrometric screws. A pore filler blend of 50 vol % γ-valerolactone and 50 vol % terpineol was poured and cast to fill the pores of backing materials. Next, the doctor blade set the gap to 200 μm, and the solution was poured on the top end of the backing material and was cast when the temperature was around 65 °C. The plate was quenched and placed in a 0 °C cold bath. The composite material was removed from the plate and immersed in methanol to extract the solvent and additives. The extraction occurred over 3 days, with three methanol volume changes. After extraction, the film was stored in water. Homogenous solutions were cast directly on the plate to create a film without backing material, and the doctor blade set the gap to 200 μm. The cast film was removed from the plate and immersed in methanol to extract the solvent and additives using the same protocol as described above.

SEM

The film morphology was analyzed by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The samples were frozen by submerging them in liquid nitrogen and fractured upon sufficient cooling. To increase the conductivity of the sample, the materials were sputter-coated with palladium at a thickness of 3 nm. An SEM (Quanta FEG-250 SEM) was used to observe the sample’s top surface and cross sections.

Pore Size

The size and distribution of pores were determined using MATLAB, and a pore size calculation code from a paper by Cosgriff-Hernandez Group. ImageJ was used to determine the scale bar distance in pixels/nm.

Porosity

Porosity was measured by the wet–dry method. The samples were weighed dry, and their volume was measured with a micrometer. Samples were immersed in isobutanol for 24 h at room temperature to fill the pores. After 24 h, the membranes were removed and weighed. This equation was used to calculate the porosity:

whereas ε, porosity; W 1, Dry weight; W 2, wet weight; ρ1, polystyrene density; and ρ2, Isobutanol.

Porosity was also evaluated by using a gas pycnometer (Anton Paar) by measuring the volume of the solid matrix via helium displacement. Circular membrane samples (∼1.23 cm2) were punched from each sheet and weighed on an analytical balance before analysis. The pycnometer using helium, chosen for its small molecular size and ability to penetrate fine pores, was used to determine the volume via the pycnometer, V pyc. The geometric volume, V geo, was calculated from the measured thickness and area of the discs. Porosity, ϕ was then calculated as

Each membrane type was measured in triplicate, and the mean porosity values were reported.

Water Flux, Molecular Weight Cutoff Curve, and BSA Rejection

This study conducted water permeation experiments using an Amicon dead-end filtration cell (Amicon Stirred Cell UFSC05001, Millipore Sigma Company, Burlington, MA, USA) at a constant pressure of 20 psi. The pure water flux was measured by using deionized water. Afterward, solutions containing 100 mg/L PEG or BSA were filtered through the membranes at the same pressure. The permeability was recorded during the filtration period, and the permeate samples were collected to analyze the concentrations of BSA. The protein concentration in the feed and permeate was determined using a microplate reader and a calibration curve. For the MWCO curve, 100 g/mol of PEG M w at a concentration of 100 ppm was filtered through the membranes for 10 g. Samples were collected and then analyzed for total organic carbon (TOC) (Teledyne Tekmar TOC fusion). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in part at the U.K. Electron Microscopy Center, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (NNCI-2025075). The authors acknowledge Nico Briot at the Electron Microscopy Center (University of Kentucky) for assistance with SEM/EDX instrumentation. Biorender was used for figure generation with permission. TOC was created in BioRender. Chwatko, G. (2025) https://BioRender.com/m84z065.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c05469.

†.

Mastercard, St Louis, Missouri 63368, United States

S.D.: Methodology; data curation; formal analysis; writingoriginal draft; writingreview and editing. I.A.I.: Methodology; data curation; formal analysis; software; writingoriginal draft; writingreview and editing. U.A.: Methodology; data curation; software. J.S.; Methodology; data curation; software. O.E.: Methodology; data curation; software. Q.S.: Conceptualization; methodology (co-lead); supervision (co-lead); writingreview and editing (equal). M.C.: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (equal); methodology (co-lead); project administration (lead); supervision (co-lead); writingoriginal draft (supporting); writingreview and editing (equal).

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (1849213).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ahmed D. S., El-Hiti G. A., Yousif E., Ali A. A., Hameed A. S.. Design and synthesis of porous polymeric materials and their applications in gas capture and storage: a review. J. Polym. Res. 2018;25(3):75. doi: 10.1007/s10965-018-1474-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara A., Prieto-Simon B., Voelcker N. H.. Porous polymeric membranes: fabrication techniques and biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9(9):2129–2154. doi: 10.1039/D0TB01727B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Xu F., Sun B., Fu R., He H., Matyjaszewski K.. Design and preparation of porous polymers. Chem. Rev. 2012;112(7):3959–4015. doi: 10.1021/cr200440z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbuoji E. A., Stephens L., Haycraft A., Wooldridge E., Escobar I. C.. Non-Solvent Induced Phase Separation (NIPS) for Fabricating High Filtration Efficiency (FE) Polymeric Membranes for Face Mask and Air Filtration Applications. Membranes. 2022;12(7):637. doi: 10.3390/membranes12070637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante J., Hardian R., Szekely G.. Antipathogenic upcycling of face mask waste into separation materials using green solvents. Sustainable Materials and Technologies. 2022;32:e00448. doi: 10.1016/j.susmat.2022.e00448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abed M. M., Kumbharkar S., Groth A. M., Li K.. Ultrafiltration PVDF hollow fibre membranes with interconnected bicontinuous structures produced via a single-step phase inversion technique. Journal of membrane science. 2012;407:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh S. P., Li K.. Effect of ethanol composition in water coagulation bath on morphology of PVDF hollow fibre membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 1998;150(1):75–85. doi: 10.1016/S0376-7388(98)00196-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D. R., Kinzer K. E., Tseng H. S.. Microporous membrane formation via thermally induced phase separation. I. Solid-liquid phase separation. J. Membr. Sci. 1990;52(3):239–261. doi: 10.1016/S0376-7388(00)85130-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russo F., Galiano F., Pedace F., Aricò F., Figoli A.. Dimethyl isosorbide as a green solvent for sustainable ultrafiltration and microfiltration membrane preparation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020;8(1):659–668. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trapasso G., Russo F., Galiano F., McElroy C. R., Sherwood J., Figoli A., Aricò F.. Dialkyl Carbonates as Green Solvents for Polyvinylidene Difluoride Membrane Preparation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023;11(8):3390–3404. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. T., Kim J. F., Wang H. H., Di Nicolo E., Drioli E., Lee Y. M.. Understanding the non-solvent induced phase separation (NIPS) effect during the fabrication of microporous PVDF membranes via thermally induced phase separation (TIPS) J. Membr. Sci. 2016;514:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.04.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Lin Y., Ma W., Wang X.. A review on microporous polyvinylidene fluoride membranes fabricated via thermally induced phase separation for MF/UF application. J. Membr. Sci. 2021;639:119759. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2021.119759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rezabeigi E., Wood-Adams P. M., Drew R. A.. Production of porous polylactic acid monoliths via nonsolvent induced phase separation. Polymer. 2014;55(26):6743–6753. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.10.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavia F. C., La Carrubba V., Piccarolo S., Brucato V.. Polymeric scaffolds prepared via thermally induced phase separation: tuning of structure and morphology. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2008;86(2):459–466. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piçarra S., Gomes P. T., Martinho J.. Fluorescence Study of the Coil– Globule Transition of a Poly (ε-caprolactone) Chain Labeled with Pyrenes at Both Ends. Macromolecules. 2000;33(10):3947–3950. doi: 10.1021/ma992106o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seuring J., Agarwal S.. Polymers with upper critical solution temperature in aqueous solution: Unexpected properties from known building blocks. ACS Macro Lett. 2013;2:597–600. doi: 10.1021/mz400227y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh R., Yousefi A. M.. Effects of processing parameters in thermally induced phase separation technique on porous architecture of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2014;102(6):1304–1315. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistor A., Vonka M., Rygl A., Voclova M., Minichova M., Kosek J.. Polystyrene Microstructured Foams Formed by Thermally Induced Phase Separation from Cyclohexanol Solution. Macromol. React. Eng. 2017;11(2):1600007. doi: 10.1002/mren.201600007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Wickramasinghe R., Qian X.. Effects of salt on the lower critical solution temperature of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114(49):16594–16604. doi: 10.1021/jp105652c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen J., Tenhu H.. How to manipulate the upper critical solution temperature (UCST)? Polym. Chem. 2017;8(1):220–232. doi: 10.1039/C6PY01612J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaljohann D.. Thermo- and pH-responsive polymers in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2006;58(15):1655–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Bae Y. C.. Thermodynamic framework for switching the lower critical solution temperature of thermo-sensitive particle gels in aqueous solvent. Polymer. 2020;195:122428. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhao C., Duan X., Zhou J., Liu M.. Finely tuning the lower critical solution temperature of ionogels by regulating the polarity of polymer networks and ionic liquids. CCS Chemistry. 2022;4(4):1386–1396. doi: 10.31635/ccschem.021.202100855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-H., He Y.-D., Wang X.-L.. Effect of adding a second diluent on the membrane formation of polymer/diluent system via thermally induced phase separation: Dissipative particle dynamics simulation and its experimental verification. J. Membr. Sci. 2012;409–410:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.03.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song S.-W., Torkelson J. M.. Coarsening effects on the formation of microporous membranes produced via thermally induced phase separation of polystyrene-cyclohexanol solutions. Journal of membrane science. 1995;98(3):209–222. doi: 10.1016/0376-7388(94)00189-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama H., Teramoto M., Kudari S., Kitamura Y.. Effect of diluents on membrane formation via thermally induced phase separation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001;82(1):169–177. doi: 10.1002/app.1836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plisko T. V., Bildyukevich A. V., Karslyan Y. A., Ovcharova A. A., Volkov V. V.. Development of high flux ultrafiltration polyphenylsulfone membranes applying the systems with upper and lower critical solution temperatures: Effect of polyethylene glycol molecular weight and coagulation bath temperature. J. Membr. Sci. 2018;565:266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely G.. The 12 principles of green membrane materials and processes for realizing the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. RSC Sustainability. 2024;2(4):871–880. doi: 10.1039/D4SU00027G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naeem A., Saeed B., AlMohamadi H., Lee M., Gilani M. A., Nawaz R., Khan A. L., Yasin M.. Sustainable and green membranes for chemical separations: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024;336:126271. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasool M. A., Vankelecom I. F. J.. gamma-Valerolactone as Bio-Based Solvent for Nanofiltration Membrane Preparation. Membranes (Basel) 2021;11(6):418. doi: 10.3390/membranes11060418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso A. P., Giacobbo A., Bernardes A. M., Ferreira C. A.. Green solvent γ-Valerolactone as a sustainable alternative for the production of polymeric membranes for pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) removal from water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024;12(6):114853. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2024.114853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett C., Hale D., Bair B., Manson-Endeboh G. s.-D., Hao X., Qian X., Ranil Wickramasinghe S., Thompson A.. Polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes fabricated from green solvents: Significance of coagulation bath composition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024;332:125752. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.125752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Lu X., Li J., Wu C.. Preparation and properties of poly (vinylidene fluoride) membranes via the low temperature thermally induced phase separation method. J. Polym. Res. 2014;21(10):568. doi: 10.1007/s10965-014-0568-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.-Q., Hao S., Xiao J., Jia Z.-Q.. Preparation of Poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) Membranes by Low-Temperature Thermally Induced Phase Separation. ACS Applied Polymer Materials. 2023;5(3):1998–2005. doi: 10.1021/acsapm.2c02064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Chen C., Li Y., Li J.. PVDF Membrane Formation via Thermally Induced Phase Separation. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A. 2007;44(1):99–104. doi: 10.1080/10601320601044575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis C. M., Müller-Buschbaum P., Laschewsky A.. Switch it inside-out:“schizophrenic” behavior of all thermoresponsive UCST–LCST diblock copolymers. Langmuir. 2019;35(30):9660–9676. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas G., Patterson D.. The molecular weight dependence of lower and upper critical solution temperatures. Journal of Polymer Science Part C: Polymer Symposia. 1970;30(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/polc.5070300103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luzar A., Chandler D.. Hydrogen-bond kinetics in liquid water. Nature. 1996;379(6560):55–57. doi: 10.1038/379055a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Rudder J., Berghmans H., Arnauts J.. Phase behaviour and structure formation in the system syndiotactic polystyrene/cyclohexanol. Polymer. 1999;40(21):5919–5928. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(98)00819-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. F., Laxminarayan A., Caneba G. T., Solc K.. Morphological studies of late-stage spinodal decomposition in polystyrene–cyclohexanol system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1995;55(5):753–759. doi: 10.1002/app.1995.070550512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werber J., Osuji C., Elimelech M.. Materials for Next-Generation Desalination and Water Purification Membranes. Nature Reviews Materials. 2016;1:16018. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez E., Campinas M., Acero J. L., Rosa M. J.. Investigating PPCP removal from wastewater by powdered activated carbon/ultrafiltration. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016;227:177. doi: 10.1007/s11270-016-2870-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bruggen B., Vandecasteele C., Van Gestel T., Doyen W., Leysen R.. A review of pressure-driven membrane processes in wastewater treatment and drinking water production. Environmental progress. 2003;22(1):46–56. doi: 10.1002/ep.670220116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Tirado-Rives J.. Potential energy functions for atomic-level simulations of water and organic and biomolecular systems. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(19):6665–6670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408037102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodda L. S., Vilseck J. Z., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W. L.. 1.14*CM1A-LBCC: Localized Bond-Charge Corrected CM1A Charges for Condensed-Phase Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121(15):3864–3870. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodda L. S., de Vaca I. C., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W. L.. LigParGen web server: an automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W331–W336. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe M., Mori K., Ueda K., Takeda M.. Development of PolyParGen Software to Facilitate the Determination of Molecular Dynamics Simulation Parameters for Polymers. J. Comput. Chem., Jpn. -Int. Ed. 2019;5:2018-0034. doi: 10.2477/jccjie.2018-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson M. J., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W. L.. Improved peptide and protein torsional energetics with the OPLS-AA force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11(7):3499–3509. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H. J., Postma J. v., Van Gunsteren W. F., DiNola A., Haak J. R.. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81(8):3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M.. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126(1):014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D., Pedersen L.. Particle mesh Ewald: An N· log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J. C., Hess B., Lindahl E.. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D., Salhadar K., Ashby G., Mishra A., Cheshire J., Beltran F., Grunlan M., Andrieux S., Stubenrauch C., Cosgriff-Hernandez E.. PoreScript: Semi-automated pore size algorithm for scaffold characterization. Bioact Mater. 2022;13:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.