Abstract

Orthopedic disorders affecting bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and other tissues are prevalent among outpatients, often caused by trauma, sports, or tumor removal. Surgical intervention is common but may yield unsatisfactory results due to limited regenerative capacity and poor blood supply. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), an autologous biocomponent, has been clinically applied in tissue regeneration and repair, yet it faces challenges such as unclear mechanisms, side effects, and uncontrollable release. This review provides evidence for further clinical research on PRP and its associated drug delivery strategies in orthopedics. We searched multiple databases, including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases Inclusion criteria focused on original studies containing the phrases (“orthopedic injuries,” “nanotechnology,” “microsphere,” or “drug delivery system”) and (“platelet-rich plasma”) over two decades to provide evidence to support further clinical research on PRP combined with nanotechnology in osteoarthritis, fractures, cartilage repair, and other orthopedic fields. Excluding criteria were referred to studies only describing “nanotechnology,” “microsphere,” or “drug delivery system”. In conclusion, PRP is a novel therapeutic tool for orthopedic diseases with advantages over traditional surgery. However, its clinical efficacy, action mechanisms, and preparation standards need further clarification. Future research should optimize PRP's therapeutic concentration, administration, and timing, and explore high-concentration PRP GFs as alternatives.

Keywords: Platelet-rich plasma, Growth factors, Cytokines, Nanotechnology, Orthopedic injuries

Graphical abstract

Illustration of nanoparticles-mediated platelet-rich plasma in treating orthopedic injuries. Platelet-rich plasma can be delivered with drug delivery systems (DDS).

1. Introduction

Orthopedic disorders impact bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and other tissues. Orthopedic injuries are prevalent among outpatients and are typically caused by trauma, sports-related activities, or tumor removal. Generally, surgical intervention is necessary to treat the injuries. However, surgical intervention modalities frequently lead to unsatisfactory results. The limited regenerative capacity and inadequate blood supply may make the defect area difficult to heal (Fang et al., 2020). Furthermore, orthopedic injuries may result in osteoarthritis (OA) formation due to pain and activity limitations (Di Martino et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2017). Therefore, an efficacious treatment strategy is imperative to preserve joint function and alleviate pain, thereby enhancing the quality of patients. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), an autologous bio-component prepared from a patient's blood, boasts a higher concentration of platelets. The cytokines and growth factors (GFs) in the platelets can repair the damaged tissues of tendons, ligaments, and cartilage by maintaining the stability of the intra-articular environment (Kawabata et al., 2023). In addition, PRP has been extensively utilized clinically for tissue regeneration and repair, particularly in orthopedics, due to the capability of modifying the microenvironments of lesion sites and stimulating tissue restoration and physiologic healing (Zhang et al., 2022a). Meanwhile, autologous PRP minimizes the risk of immune rejection (Manole et al., 2024). However, several challenges remain regarding the applications of autologous PRP. The mechanisms by which PRP works in the human body and the possible side effects still need to be clarified through extensive research. Issues such as uncontrollable release, instability, off-target delivery, and below-effect-acting concentration have also been noted and discussed.

In this context, drug delivery systems (DDSs) offer some promising choices for solving PRP therapy-facing issues. The shape and size of materials can be meticulously regulated by the microencapsulation process or nanotechnology so that these carriers have similar structures to biological molecules and vesicles and can be designed with various functions (Kim et al., 2010). Incorporating drugs into microscale or nanoscale particles (MPs or NPs) may enhance efficacy, prolong half-life, and improve specific binding properties (Pistone et al., 2017). These technologies have also been widely used in orthopedics, including diagnostic modalities, targeted drug delivery, vertebral disk regeneration, and implantable materials (Pleshko et al., 2012). Particles can encapsulate drugs steadily, control drug release, prolong retention time, and improve the drug's pharmacodynamics in vivo (Barani et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2018). Meanwhile, the rational design of particles, especially NPs, helps the drug diffuse and penetrate the extracellular matrix (ECM) and joint tissues to promote cartilage repair (Wen et al., 2023). Combining PRP with nanoscale DDSs aims to address the limitations of PRP therapy and enhance its safety and efficacy in disease treatment through precise delivery, long-term release, and improved stability of PRP. We reviewed PRP's application in orthopedics over the past two decades, focusing on studies that combine PRP with DDSs. The aim is to provide evidence for further clinical research on PRP and its associated DDSs in osteoarthritis, fractures, cartilage repair, and other orthopedic areas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The applications of nanoparticles mediated platelet-rich (PRP) plasma in the orthopedic field. PRP can be delivered with DDSs such as microspheres, extracellular vesicles, hydrogel particles, and polymeric nanoparticles, by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

2. Method

The research followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure a comprehensive and systematic review, enhancing credibility and accessibility for future researchers (Page et al., 2021). Specific criteria ensured high-quality, original research articles on “nanotechnology,” “microsphere,” or “drug delivery system” of PRP for orthopedic injuries were included, focusing on peer-reviewed English studies over two decades, while excluding studies only describing “nanotechnology,” “microsphere,” or “drug delivery system”. The patents were also excluded. The databases included PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar. All search results were exported to Mendeley for duplicate removal, followed by a two-stage filtering: title relevance screening and detailed abstract/complete text examination. Reviewers ensured articles met inclusion criteria before data extraction, which was organized into tables by factors like soft or complex type of nanocarriers, disease class, in vitro or in vivo outcomes of the combination of PRP and DDS.

3. Platelet-rich Plasma (PRP)

3.1. Concept of PRP

PRP is an autologous biological component obtained from a patient's blood via centrifugation (Chueh et al., 2022; Everts et al., 2020). PRP was first defined in hematology in the 1970s when hematologists referred to the supraphysiologic concentration of platelets in plasma as PRP. Evidence suggests that PRP was used primarily to treat patients with thrombocytopenia (Gupta et al., 2021; LaBelle and Marcus, 2020). In 1982, Childs CB et al. (Childs et al., 1982) discovered that plasma containing platelet-derived GFs can promote cell growth. Gibble JW et al. (Gibble and Ness, 1990) summarized platelets' hemostatic and adhesive properties and delved into platelet-related applications in the surgical field. Since then, PRP research has grown rapidly. Nowadays, it has been shown that PRP has anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, along with the capability to improve tissue regeneration, etc. Additionally, PRP plays an essential role in various clinical disciplines, including orthopedics, burns and plastic surgery, and neurosurgery (Liang et al., 2022). Although PRP has been extensively studied in recent decades, the lack of consensus terminology, classification, and characterization has led to confusion about the terms associated with PRP. Over the years, different classification systems have been proposed to define various categories of PRP, as shown in Table 1. In 2016, Magalon et al. (Magalon et al., 2016) introduced the DEPA classification according to Dose, Efficiency, Purity, and Activation of PRP. Therefore, the quantity of platelets in the PRP, the purity of the product, and platelet status before injection become the focus of attention (Alves and Grimalt, 2017). In addition, based on PRP fibrin structure and platelet content, PRP is categorized into four primary groups: leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) and pure platelet-rich fibrin (P-PRF), pure PRP (P-PRP) with lower content of leukocyte, and leucocyte- and platelet-rich plasma (L-PRP). Such a categorization takes into account the different biological characteristics and mechanisms of PRPs, which differ markedly in their clinical application. This categorization can be used further to investigate the impact of these products (Dohan Ehrenfest et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Classification systems of PRP.

| Classification systems | Criteria | Types of PRP | Features | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dohan Ehrenfest classification | Based on the leukocyte enumeration and fibrin framework | P-PRP | The first classification system for platelets | (Dohan Ehrenfest et al., 2009) |

| L-PRP | ||||

| P-PRF | ||||

| L-PRF | ||||

| Mishra's classification | Based on leukocyte concentrations, platelets and their activation status | L-PRP solution | A specialized classification of PRP has been proposed in sports medicine. | (Mishra et al., 2012) |

| L-PRP gel | ||||

| P-PRP solution | ||||

| P-PRP gel | ||||

| PAW classification | Based on the number of platelets, the method of platelet activation, and the existence of leukocytes | “P3-x-Aα” represents three parameters: Platelet levels (cell numbers/μL): (1) > 1,250,000; (2) > 750,000 -1,250,000; > baseline - 750,000; (4) ≤ baseline |

Limited as it encompasses solely the PRP family | (DeLong et al., 2012) |

| X-exogenous activation | ||||

| Existence of WBCs: above the baseline (a) or at/below the baseline (b) | ||||

| Existence of neutrophils; exceed the baseline (i) or remain at or below the baseline (ii) | ||||

| PLRA classification | Based on the concentration of platelet (cells/μL), the presence of leucocytes (<1% – negative or > 1 % - positive), the proportion of neutrophils, the level of RBCs (<1 % - negative or > 1 % - positive), and the state of activation (no - negative or yes - positive) | The first classification system that proposed the inclusion of RBC concentration as a variable | (Mautner et al., 2015) | |

| DEPA classification | Based on injected dose, efficiency, purity, and activation status | Efficiency gauged by the rate of platelet recovery: > 5 (a), 3–5 (b), 1–3 (c), <1 (d) |

New classification systems | (Magalon et al., 2016) |

| Purity assessed through the relative composition of platelets: > 90 % (a), 70–90 % (b), 30–70 % (c), <30 % (d) |

||||

| The activation status: >90 % (a), 70–90 % (b), 30–70 % (c), <30 % (d) | ||||

| MARSPILL classification | Based on the preparation technique, spin number, imaging guidance, and luminescent activation | M (Method), A (Activation-), R (Red blood cells-P), S (Spin 2), P (Platelets [4–6]), I (G+) (Image guidance), L (Leukocytes-R [2–3]), L (Light activation) |

This classification also includes PRP's preparation, composition, and application process. | (Lana et al., 2017) |

| Platelet Physiology Subcommittee classification | Based on the ratio of leukocyte to RBC activation process, platelet levels, and the preparation methods | PRP | The classification system encompassed all principal factors of PRP production; however, the expansive range of platelet concentration resulted in a lack of precision. | (Harrison, 2018) |

| Red cell-rich PRP | ||||

| L-PRP | ||||

| red cell and leukocyte-rich PRP |

3.2. Composition and preparation of PRP

PRP is the plasma of autologous blood from whole blood, enriched with a higher concentration of platelets, 4–8 times higher than normal platelets. Platelets have been divided into three primary types of secretory granules: lysosomes, α-granules, and dense γ-granules (Mumford et al., 2015). Moreover, it also contains chemokines and proteins (Thu, 2022). Studies have shown that the α-granules can release various GFs and cytokines. Cytokines and GFs are crucial in tissue healing, effectively promoting tissue repair (Table 2). They have the functions of cell proliferation stimulants, cell migration chemoattractants, and mitogens (Harrison et al., 2011). Table 2 summarizes the types and functions of GFs and cytokines in PRPs. Among them, the GFs mainly include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), transforming growth factor (TGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (Cecerska Heryć et al., 2022). Multiple studies have shown that the GFs derived from platelets in PRP can stimulate the growth of newly formed blood vessels and enhance metabolism at the injection site. Therefore, the PRP treatment can promote the regeneration and reconstruction of tissue (Fang et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Major cytokines and GFs in PRP.

| Names | Features | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFs | VEGF | 1. Promotes angiogenesis | (Gobbi and Vitale, 2012; Rodrigues et al., 2019; Street et al., 2002) |

| 2. Anti-apoptotic effect | |||

| Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 | 1. Regulates the proliferation and migration of a wide range of cells | (Gobbi and Vitale, 2012) | |

| 2. Accelerated tissue regeneration and repair | |||

| PDGF | 1. Accelerates cell proliferation and tissue repair | (Gobbi and Vitale, 2012; Hollinger et al., 2008) | |

| TGF-β | 1. Regulates cell functions, including suppression of cell proliferation and promotion of cell differentiation | (Gobbi and Vitale, 2012; Komaki et al., 2006) | |

| IGF | 1. Regulates cell proliferation, differentiation and metabolism | (Middleton et al., 2012; Sample et al., 2018) | |

| EGF | 1. Promotes skin tissue repair and soft tissue regeneration, thus accelerating routine healing | (Martínez et al., 2015; Mussano et al., 2016) | |

| Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α | 1. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) signaling pathway | (Bendinelli et al., 2010; Riboh et al., 2016) | |

| 2. Exerts a pro-inflammatory response and anti-apoptosis | |||

| Cytokines | IL-1b | 1. Regulation of NF-kB signaling pathway | (Hudgens et al., 2016) |

| 2. Modulation of inflammatory and immune responses | |||

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | 1. Degradation of ECM molecules and collagen | (Liu et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2015) | |

The preparation of PRP usually includes the double-centrifugation method and single-centrifugation method. The double-centrifugation method usually consists of soft spinning and hard spinning steps, whereas the single centrifugation method only needs one centrifugation separation process (Saqlain et al., 2023) (Fig. 2). The advantages of single-centrifugation include fast and efficient performance, simple operation, and cost-effective savings. Comparatively, the samples prepared by the double-centrifugation method have better platelet enrichment, greater compliance with sterility, and less probability of cell contamination. Until now, there have been no standardized procedures for the blood samples and preparation processes, and the quality and effects of PRP have varied. Studies have shown that factors such as the amount of whole blood, rotation rate, platelet agonist, and preparation temperature can affect the quality and effects of PRP. Sabarish et al. (Sabarish et al., 2015) investigated the impact of rotation rates (1000–3600 rpm) and centrifugation time (4 to 15 min) on PRP quality, respectively. The results demonstrated that lower rotation rates and less time can obtain higher platelet content and enrichment rates. Additionally, higher rotation rates may result in platelet aggregation or disintegration. Lansdown et al. (Lansdown and Fortier, 2017) emphasized that factors related to patients also influenced platelet concentration. Meanwhile, both the feeding and the time of the blooding sample affect the final quality of PRP.

Fig. 2.

Preparation of platelet-rich plasma by centrifugal methods. By Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

The standard protocol for preparing PRP is crucial for the quality control of the obtained PRP and is also a prerequisite for evaluating the results of clinical experiments (Lin et al., 2021). However, in the case of orthopedics, Chahla et al. found that only 11 of the studies provided preparation protocols for PRP, and only 17 studies provided qualitative indications of PRP compositions (Chahla et al., 2017). Therefore, the current studies must improve the transparency of the clinical and laboratory reports on PRP to promote standardization of PRP production and ensure the safety of use (BW et al., 2019).

3.3. Biological properties and action mechanisms of PRP

PRP includes numerous GFs, cytokines, and differentiated adhesion molecules, which trigger the activation and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), fibroblasts, neutrophils, and smooth muscle cells (Zahn et al., 2017). Cytokines and adhesion molecules in PRP can promote migration, adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation of cells. For instance, the activated stromal cell-derived factor (SDF) 1α mediates cell migration and homing to the repair site. Some GFs, such as PDGF, TGF, VEGF, etc., play an essential role in promoting collagen synthesis (T et al., 1999), osteoblast proliferation (Shimoaka et al., 2002), macrophage activation, angiogenesis (Murakami et al., 2008), chemotaxis of immune cells and fibroblast (Seghezzi et al., 1998), migration and mitosis of endothelial cells (Lee et al., 2010), cytokine secretion from epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Seckin et al., 2022), and differentiation of epithelial cells (Murakami et al., 2008). Each factor plays a different role in specific tissues. For instance, PDGF is a critical cytokine in the early stages of tissue healing, promoting cytokinesis and matrix production. TGF-β regulates collagen and proteoglycan synthesis and modulates the release of other GFs. VEGF is a signaling protein that promotes neointima formation and vascular system development, and its interactions with the surface receptors of endothelial cells stimulate the migration and mitosis of endothelial cells. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) synergizes with VEGF to promote vascularization; IGF plays a vital role in tissue repair, maturation, and remodeling; and EGF promotes cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation through its interactions with the EGF receptor (B et al., 2013; Manole et al., 2024). In addition, fibronectin is also an important component of PRP that produces a suitable three-dimensional (3D) structure that provides a good scaffold for cell repair, facilitates the secretion of GFs and tissue repair, shrinks the wound to promote coagulation and wound closure, and stimulates tissue regeneration (Wang et al., 2023).

PRP is a key factor in triggering tissue repair and regeneration. There are four primary platelet activation methods: autologous thrombin, a combination of thrombin and CaCl2, a mixture of 10 % type I collagen and CaCl2, and the freeze-thaw method. Different activation methods determine the amount and kinetics of GFs released from PRP (Fang et al., 2020). For example, studies showed that the GFs released from PRP were increased gradually at 15 min and up to the peaks at 24 h by the CaCl2-activated method (Cavallo et al., 2016). In contrast, the GFs released from PRP activated by autologous thrombin were less effective and induced less platelet aggregation. In addition, CaCl2-activated PRP was significantly better than the other methods in releasing PDGF (Textor and Tablin, 2012). Therefore, choosing the appropriate activator and standardizing the platelet activation process are critical steps to optimize the release of various GFs and cytokines during application.

3.4. Clinical applications of PRP in orthopedics

3.4.1. Regenerative medicine

In the emerging field of tissue engineering, PRP is widely applied as a novel therapeutic tool in cardiothoracic surgery, dentistry, wound healing, orthopedics, dermatology, plastic surgery, hair loss, etc. (Seckin et al., 2022). The following contents summarize the advances of PRP in the field of orthopedics. In animal experiments, Takahiro et al. explored the effects of intravertebral disc injection of PRP releaser (PRPr) in rabbits on condylase-induced degenerative intervertebral disc (IDV) regeneration. The data suggested that the group injected with PRP had statistically lower histologic scores than the other group (p < 0.01). It was demonstrated that PRPr promoted the regeneration of condylase-induced rabbit IVD (Hasegawa et al., 2023). The data suggested that PRPr injection therapy may be suitable for patients with herniated discs who have poorly recovered from disc degeneration induced by condolence. In an animal model of hindlimb ischemia, Stilhano et al. (Stilhano et al., 2021) investigated the mechanisms of L-PRP and pure P-PRP promoting the regeneration of ischemic skeletal muscle of mice. The results showed that 1 % of PRPs induced higher metabolism and increased survival in C2C12 and NIH3T3 cells. Ischemic limbs treated with PRP increase ischemic mice's skeletal muscle mass and strength. Autologous PRP dramatically minimizes the risk of allergic reactions or incompatibility. It has been shown that PRP holds broad promise in wound regeneration by enhancing collagen synthesis and remodeling (Manole et al., 2024). In a recent article by Sharun et al. (Sharun et al., 2024), the potential of PRP for treating tendon and ligament injuries, OAs, and fractures in experimental studies using goats and sheep was reported. Animal-derived PRP studies provide strong evidence for the application of PRP in biological repair and regenerative medicine.

3.4.2. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects

Tohidnezhad et al. (Tohidnezhad et al., 2017) demonstrated that PRP exerted anti-inflammatory effects through cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, that can reduce the inflammatory responses of human synoviocytes under inflammatory conditions. In treating chronic patellar tendinitis, PRP injections show better pain relief and functional recovery compared to conventional extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) (Smith and Sellon, 2014). A systematic evaluation showed that PRP injections were used to promote healing at the interface of tendon and bone. The injections of PRP for arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs may reduce postoperative pain and facilitate functional recovery (Samy et al., 2020). Bohren et al. reviewed the potential of PRP injection in neuropathic pains (Bohren et al., 2022). The anti-inflammatory mediators released from PRP can reduce inflammation and pain.

3.4.3. Fighting infections

Chronic infections are a clinical challenge to disease prevention, treatment, and management. Autologous PRP minimizes the risk of immune response and pathogen transmission (Jones et al., 2018). Also, after PRP is activated, many bioactive molecules, such as anti-microbial proteins, cytokines, and the released GFs, can inhibit bacteria and help wound healing. Badade et al. confirmed that PRP in vitro inhibited the adhesion and growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Porphyromonas actinomycetes to form Actinobacteria aggregates (periodontal pathogens), thus protecting the gingiva (Badade et al., 2016). Cervelli et al. investigated a new clinical choice to treat complex wounds with bone exposure after lower extremity surgery under PRP with HA adjuvant. The study involved 15 patients, all of whom suffered from bone-exposed wounds following lower extremity trauma. The data confirmed that the mean time of re-epithelialization of 73.3 % of patients who received the combination treatment of PRP and HA was 8.1 weeks. Comparatively, only 30 % of individuals who used only HA dressings realized the same responses (Cervelli et al., 2011). Rahimi et al. (Rahimi et al., 2023) assessed the therapy effects of allogeneic PRP, fibrin glue, and collagen matrix in treating severe limb-threatening open tibial fractures. The results showed that after treatment, the patient's wound closed completely, formed tissue granules, and successfully preserved his right leg. This suggests that combining these components can decrease the odds of infection, synergistically accelerate wound healing, and protect the limb. PRP is used to prevent postoperative infections and treat chronic wounds or bone infections. However, a significant and compelling clinical rationale is still needed to support this (Zhang et al., 2019b).

3.5. Limitations

PRP has been extensively selected for clinical application and has become the “superstar” of orthopedic treatments. However, the adequate time of PRP in the human body is short due to the short half-life of cytokines and GDs. Compared to antibiotics, PRP's antimicrobial effects are shorter and weaker (Mouanness et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019b). In addition, PRP treatment has lower specificity, weaker stability, and difficulty in controlling local concentrations. The standardized PRP preparation must provide reliable quality assurance for basic research and clinical applications. However, the current PRP preparation techniques lack a unified standard, compromising the quality of PRP products. Therefore, establishing expert consensus on the standardization of PRP preparation techniques and quality control is essential for ensuring the safety and efficacy of PRP in clinical use. Indeed, the quality and composition of autologous biocomponents may change with changes in the patient's condition, thus increasing the difficulty in standard setting. Hopefully, the black box of practical components must be fully elucidated to formulate artificial “PRP” based on effect ingredient formulations.

4. PRP-contained drug delivery systems

DDSs can achieve localized higher drug concentrations in the target tissue and reduced side effects in other tissues by controlling drug release. This is particularly crucial in tissues with limited vascularization, such as osseous tissue. In current clinical research, NPs have been becoming a novel means of delivery of PRP to improve the efficacy of active ingredients. Delivery of active ingredients in PRP using carriers such as exosomes, microvesicles, microspheres, polymeric NPs, etc., can bring a series of potential advantages. The following contents describe the progress of PRP combined with NPs in orthopedics (Table 3).

Table 3.

PRP-related DDSs.

| DDSs | Applications | Targets | Advantages | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRP-Exos | Rotator cuff tendon-bone healing; Femoral head osteonecrosis (FHON) |

Enhance tendon-bone healing; block apoptosis through Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 pathway | Accelerates tissue healing; reduces apoptosis effectively | (Han et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2017) |

| PRP-Exos-Gel | Subtalar osteoarthritis (STOA) | Prolong PRP release, inhibit chondrocyte apoptosis, and recruit stem cells | Increased local retention time, enhanced therapeutic efficacy | (Zhang et al., 2022a) |

| Chitosan-gelatin/nano-hydroxyapatite (CS-G/nHA) |

Osteogenic differentiation | Enhance osteoblast differentiation and mineralization | Improves scaffold integration, enhances osteogenic potential | (Sadeghinia et al., 2019) |

| Chitosan nanocomposite membrane | Burn wound healing | Regulate gene expression in wound healing | Enhanced therapeutic outcomes in burn management | (He et al., 2022; Tramś et al., 2022) |

| HA hydrogel | Cartilage defect repair | Facilitate cartilage regeneration | Injectable, supports significant cartilage regeneration | (Yan et al., 2020) |

| GelMA/Chitosan microcarriers (IGMs) |

Dermal papilla cell bioactivity enhancement | Sustain release of GFs; enhance bioactivity of dermal cells | Mimics ECM environment sustains cellular bioactivity | (Zhang et al., 2022b) |

| Hydroxyapatite-collagen scaffold | Osteochondral defect repair | Promote cartilage and bone regeneration | Enhanced bone regeneration, but interaction with PRP requires optimization. | (Kon et al., 2010) |

4.1. Extracellular vesicles

In recent years, increasing research has focused on extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from PRP. The EVs usually refer to nano-sized structures with a lipid bilayer that does not replicate (Antich Rosselló et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). In a study by Anitua et al. (Anitua et al., 2023), the signs of progress of PRP-EVs in regenerative medicine were comprehensively reviewed, demonstrating that PRP-EVs represent a promising treatment approach for tissue restoration and regeneration. Besides this, PRP-EVs can promote cellular proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis (Dai et al., 2023; Rui et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022a) but also reduce the inflammatory response, apoptosis and oxidative stress, etc. (Dai et al., 2023; Otahal et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021a; Zhang et al., 2022a). In addition, due to the lower immunogenicity of PRP, its ability to protect against degradation, and its capability to overcome biological barriers, PRP-EVs can function at the molecular level through various signaling pathways. These signaling pathways encompass Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 (Tao et al., 2017), Wnt/β-catenin (Dong et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019), YAP (Guo et al., 2017), TLR4 (Zhang et al., 2019a), PI3K/Akt (Zhang et al., 2020), PGC1α-TFAM (Dai et al., 2023), Keap1-Nrf2 (Xu et al., 2021a), and AKT/ERK (Rui et al., 2021). Table 4 summarizes these signaling pathways.

Table 4.

Mechanisms of action of PRP-derived vehicles related to the signaling pathway.

| Signaling pathways | PRP-derived vehicles | Diseases | Action mechanisms | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | PRP-derived exosomes | Osteoarthritis (OA), Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) | Exosomes derived from PRP stimulated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, enhancing chondrocyte growth and reducing cell death in osteoarthritis. In cases of osteonecrosis affecting the femoral head, they promoted the growth of osteoblasts and increased the expression of osteogenic markers, thus preventing bone degeneration caused by glucocorticoids. | (Dong et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2017) |

| AKT/ERK | PRP-derived exosomes | Tissue regeneration, Angiogenesis, Wound healing | Exosomes derived from PRP, particularly when activated with thrombin and calcium gluconate, greatly enhanced endothelial cells' proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis by triggering the AKT/ERK signaling pathway. The activated exosomes showed increased levels of angiogenic GFs like VEGF, PDGF-BB, bFGF, and TGF-β, which boosted their therapeutic effects for tissue regeneration and wound healing. | (Guo et al., 2017; Rui et al., 2021) |

| TLR4 | PRP-derived exosomes | Diabetic retinopathy | High glucose-induced PRP-derived exosomes activated the TLR4 signaling pathway in retinal endothelial cells, enhanced TLR4 and downstream protein expression, and markedly increased the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine CXCL10, mediating retinal endothelial damage. | (Zhang et al., 2019a) |

| PI3K/Akt | PRP-derived exosomes | Retinal fibrogenesis, Müller cell fibrosis | Diabetes mellitus-derived PRP-exosomes activated the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, significantly enhancing retinal Müller cell proliferation, migration, and the expression of fibrogenic markers, including connective tissue GFs (CTGF) and fibronectin, thereby promoting retinal fibrosis. | (Zhang et al., 2020) |

| SIRT1/PGC1α/TFAM | Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles | Intervertebral disc degeneration (IVD) | Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles (PEVs) restored compromised mitochondrial function, reduced oxidative stress, and reprogrammed cellular metabolism in nucleus pulposus cells through the modulation of the SIRT1/PGC1α/TFAM signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting apoptosis and senescence and delaying the progression of disc degeneration. | (Dai et al., 2023) |

| Keap1/Nrf2 | PRP-derived exosomes | IVD | Exosomes from PRP transported miR-141-3p into nucleus pulposus cells, targeting and breaking down Keap1 mRNA, which led to the liberation of Nrf2 from the Keap1-Nrf2 complex. Once activated, Nrf2 moved into the nucleus, boosting antioxidant defenses and lowering oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately reducing disc cell apoptosis and degeneration. | (Xu et al., 2021a) |

| YAP | PRP-derived exosomes | Wound healing | Exosomes from PRP stimulated the YAP signaling pathway in keratinocytes, leading to increased cell proliferation, migration, and re-epithelialization, which helped speed up the healing of chronic skin wounds in diabetic models. | (Guo et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021b) |

| Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 | PRP-derived exosomes | Steroid-caused osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) | Exosomes derived from PRP activated the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 signaling pathway, which helped prevent apoptosis induced by glucocorticoids and encouraged the proliferation of osteoblasts. These effects helped maintain bone structure and halted the advancement of steroid-induced osteonecrosis. | (Tao et al., 2017) |

The cells release two subtypes of EVs, including microvesicles (MVs) and exosomes (Exos). They can be obtained by differential centrifugation (DC) (Xu et al., 2016). The Exos are nanosized EVs that were excreted from the endosomes of eukaryotic cells and were first discovered in 1983. Their sizes range from 40 to 160 nm in diameter, and the average size is about ∼100 nm. The biological formation of Exos begins with the double invagination of the plasma membrane, and then the intracellular multivesicular bodies are fused with the cell membrane. Afterward, they are released outside the cells (He et al., 2018; Kalluri and LeBleu, 2020; Lai et al., 2022). Exos help realize the communication between healthy and pathological cells and may be the best carriers for clinical therapeutics. It has a bilayer membrane structure that protects the active agents, prolongs the circulating half-life of the payloads, and enhances their bioactivity. Exos can also improve the natural components in the lipids and proteins of the carrier's bioactivity and reduce their adverse effects.

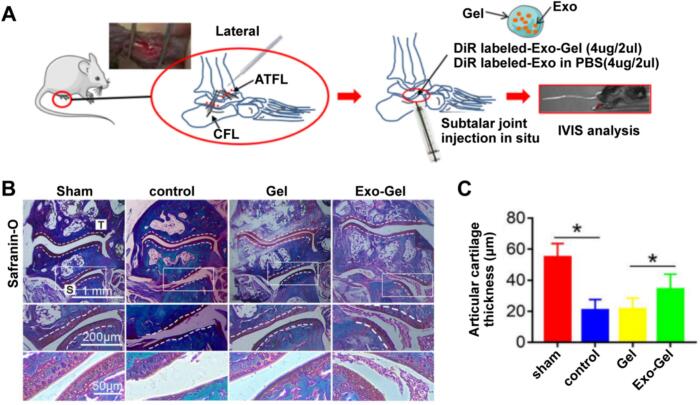

Meanwhile, Exos can carry many payloads, such as TGF β1, PDGF BB, VEGF, and so on, to avoid the degradation of these contents in vivo. Exos exhibit no species differences and do not induce immunogenicity. In addition, the signals carried by Exos can be transmitted across species (He et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a). Exos can influence the immune response through antigen presentation, thus crucial in stimulating or inhibiting the immune system. Biological or chemical modification of the vesicular lipid bilayer can enhance the targeting ability of Exos (He et al., 2018). Exos can be distinguished from other vesicles by specific protein structures, including CD9, CD63, and CD81. Exos derived from PRP have also been used in clinical applications. Han et al. (Han et al., 2024) explored the effects of PRP-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos) on the healing of rotator cuff tendon (RCT)-bone. New Zealand rabbits were used to construct an RCT animal model, and HE staining was performed to observe the repair of tendon bone tissue. The data exhibited that the proliferation and differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells (TDSCs) were promoted due to PRP-Exos. The in vivo data have demonstrated that PRP-Exos has the potential to facilitate the prompt healing process of injured tendons. After being treated with PRP-Exos, rabbits showed better tissue alignment at the tear site and more substantial tendon bone healing. Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2022a) investigated whether PRP-Exo doped with thermosensitive hydrogel (Gel) could prolong the time of release within the joint and achieve better therapeutic effects in subtalar osteoarthritis (STOA) (Fig. 3A). The in vivo studies have demonstrated that Exo-gel can increase the local retention time of vesicles, inhibit the hypertrophy and apoptosis of chondrocytes, promote their growth, and may recruit stem cells, thereby delaying the onset of STOA (Fig. 3B-C). Therefore, clinical therapy with PRP-Exos combined with thermosensitive gel paves a new avenue for STOA. Tao et al. (Tao et al., 2017) hypothesized that PRP-Exos could trigger the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 cascade reactions to block glucocorticoid (GC)-related endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced apoptosis due to the femoral head osteonecrosis (FHON) in rat. In their studies, the author created a dexamethasone-induced cellular model as well as a methylprednisolone (MPS)-induced rat model. The PRP-Exos was characterized, and the therapeutic responses of PRP-Exos on angiogenesis, proliferation, apoptosis, and osteogenesis in cells induced with GC were investigated (Fig. 4). In addition, they analyzed that the degree of GC-induced apoptosis was alleviated by PRP-Exos and identified the pathway of Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 to realize this alleviation. The data showed that PRP-Exos was able to block the apoptosis induced by GC in rats with the FHON due to the promotion of Bcl-2 expression through the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 pathway, which was stimulated by endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Fig. 3.

Exo-Gel elongates the vesicle retention time in the defects of the ankle. (A) Scheme illustrating experimental design. After transecting of calcaneal fibular ligament/anterior talofibular ligament, the gel containing DiR-labeled Exo was injected into the defects of the subtalar joint to lead to the instability of the subtalar-ankle joint complex. (B) Histological staining using safranin-O was performed on the subtalar joint section to assess cartilage degeneration. The enlarged images below show the regions in the inset box. The thickness of the lateral calcaneus cartilage was gauged at 15 points in each section of B (Zhang et al., 2022a). Copyright © 2022, The Yu Zhang (s).

Fig. 4.

Impacts of PRP-Exos on cellular behavior and repair of the GC-triggered defected femoral heads of rats. (A) Ki67 immunostaining confirmed the early impacts of PRP-Exos on cell proliferation within the GC-triggered FHON tissue in rats. (B) TUNEL assay was used to analyze the early impacts of PRP-Exos on cell apoptosis within the GC-triggered FHON tissue in rats. (C) MicroFil was used to examine the long-term effects of PRP-Exos on the blood supply of the FHON tissue in rats. (D) Micro-CT scanning was used to observe the sagittal (SAG), transverse (TRA), and reconstructed coronal (COR) changes of the FHON bone after long-term PRP-Exos treatment as compared with the healthy or methylprednisolone (MPS) (Tao et al., 2017). Copyright © 2016, The Shi Cong Tao (s).

MVs formation requires rearranging molecules within the plasma membrane, leading to the changed composition of lipids and proteins (Ayers et al., 2015). One of the lipids enriched in MVs is cholesterol (42.5 %). Meanwhile, MVs contain proteins that usually undergo high post-translational modifications, including CD40, integrins, glycoprotein Ib, and P-selectin (Lai et al., 2022). Pharmacological inhibition experiments have shown that, after various stimuli, the enzyme aSMase is translocated to the plasma membrane to promote the formation of microvesicular particles (MVP) (Rohan et al., 2022). In addition, cytoskeletal elements and their regulators are also necessary for MVs biosynthesis (van Niel et al., 2018). Preparation methods for MVs include direct hydration, film hydration, and pH conversion methods (Fonseca et al., 2024). MVs diameters range from 50 to 1000 nm (van Niel et al., 2018). MVs released from cell surfaces are the markers of the apoptotic or activation state of the cells from which they originate, thus providing information on the nature and quantity of MVs in circulation as an aid to clinical diagnosis and treatment of tissue or organ status (Ayers et al., 2015). Effective identification of cell states by MVs can help to improve drug stability and realize controlled or sustained release of drugs, which shows massive promise within the realm of targeted drug delivery. MVs in the transport of bioactive substances can counteract the systemic immunosuppression induced by UVB radiation. UVB irradiation to human skin explants and the keratinocyte-derived human cell line HaCaT leads to platelet-activating factor receptor (PAFR)-dependent excretion of MVs (Liu et al., 2021). For the study of PRP-derived MVs, Lovisolo et al. (Lovisolo et al., 2020) investigated the wound-healing effects of PRP and PRP-derived MVs in an in vitro human keratinocyte model. They added PRP, activated calcimycin, and PRP-derived MVs separated by high-speed centrifugation to scratched keratinocyte monolayers, comparing the healing closure at 0 and 24 h. The results showed that PRP-derived MVs could fully replicate the wound-healing effects of PRP. This preliminary study suggested that using highly purified PRP-derived MVs obtained through cell sorting or ultracentrifugation may facilitate the application of PRP-derived MVs in animal models or clinical settings to further explore their therapeutic potential.

A recent report by Hou et al. (Hou et al., 2023) provided a systematic analysis of the roles of PRP-EVs in tissue regeneration. This article systematically examines the biological properties, extraction methods, identification processes, activation techniques, and preservation strategies associated with PRP-EVs. Furthermore, it explores their applications in OA and wound healing. Finally, the article underscores the significance of PRP-EVs in contemporary medicine and posits their potential as promising natural nanocarriers.

4.2. Microspheres

Microspheres are micron-sized spheres composed of a continuous phase of one or more mixed and dissolved polymers (Karan et al., 2020). Their distinctive spherical morphology and uniform size enable microspheres to adsorb or encapsulate ions, extracellular molecules, and drugs during tissue regeneration, making them ideal for drug storage and bioactive molecular delivery (Zhu et al., 2022). Current microsphere preparation methods include emulsion-based techniques, microfluidics, spray drying, co-precipitation, supercritical fluid processing, and superhydrophobic surface-mediated approaches (Li et al., 2024). Choi et al. (Choi et al., 2020) developed biodegradable polyethylene glycol (PEG) microspheres loaded with PRP using microfluidic technology. Their studies not only characterized the PRP-loaded PEG microspheres but also further determined whether platelet aggregation and clotting would affect microsphere degradation in the presence of PRP. The results showed that platelet aggregation could prolong the release of PRP from the microspheres. The microspheres show promise for controlled PRP release to accelerate tissue restoration and wound healing or inhibit tissue degradation in OA and IVD. In recent years, with the rapid development of hydrogel materials in the biomedical field, hydrogel microspheres are increasingly regarded as promising therapeutic carriers.

Researchers are now exploring their potential as injectable biomaterials for localized cell and drug delivery. For example, Yuan et al. (Yuan et al., 2024) developed GelMA hydrogel microspheres to modify the delivery kinetics of PRP, successfully extending its sustained release time. Experimental results showed that the hydrogel microspheres with sustained release features could enhance the effectiveness of PRP in treating endometrial lesions and achieving pregnancy. This study undoubtedly provides a new approach to managing endometrial disorders. Similarly, Zhou et al. (Zhou et al., 2021) immobilized PRP platelets onto gelatin microspheres (GMs), creating a biomimetic bioreactor (PRP + GMs) and exploring its wound-healing potential. Compared to PRP alone, PRP + GMs elongated and enhanced cytokines release, showing the potential to accelerate wound healing. The authors believe this gel microsphere is an injectable particle that can improve the therapeutic benefits of PRP.

Additionally, the application of hydrogel microspheres in orthopedics has gained attention. Nagae et al. (Nagae et al., 2007) successfully loaded PRP into hydrogel microspheres to treat IVD. The results showed that PRP was continuously released as the hydrogel degrades, suggesting that synergistic application of PRP and hydrogel microspheres may provide a new therapeutic approach for IVD. Lin et al. (Lin et al., 2024) summarized the relevant research and application of hydrogel microspheres as vehicles for cellular and pharmaceutical delivery in cartilage, bone, and soft tissue regeneration.

4.3. Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are soft organic materials made of biocompatible lipids or polymers with particle sizes ranging from 1 to 1000 nm (Ong et al., 2021). Naturally synthesized PNPs are multifunctional nanocarriers with more features, including biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity. As DDSs, PNPs are capable of controlling the rate of drug release, enhancing drug stability and bioavailability, and enabling drug delivery to desired tissues. As a result, the PNPs are now widely utilized in healthcare for various applications, such as prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases (Swetledge et al., 2021). Loading an imaging substance or drug with solid or solution status into PNPs may improve diagnostic sensitivity or drug efficacy, elongate the half-life, and reduce side effects, enhancing patient safety and compliance (Patel et al., 2012). PNPs can deliver drugs via various routes, such as oral, intranasal, intravenous, or intraperitoneal administration (Zhang et al., 2021). Several techniques are available for preparing PNPs, including solvent evaporation, emulsification/solvent diffusion, emulsification/reversed salting out, and solvent substitution. The choice of method can be tailored based on the physicochemical characteristics of the drug encapsulated within the PNP and the specific requirements for the intended route of administration. Method I, the preparation process of solvent evaporation, is shown in Fig. 5A. The First step is to prepare an oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion, followed by the solidification process under vigorous stirring, and then harvest PNPs. Method II, the emulsification/solvent diffusion technique, is depicted in a schematic representation in Fig. 5B, allowing the formation of PNPs with sizes ranging from 80 to 900 nm due to the infiltration of organic solvent into the water phase. Method III, the emulsification/reversed salting out process, is idepicted in a schematic representation in Fig. 5C, which can be regarded as an improved emulsification/solvent diffusion process method. Adding salt into the water phase further decreases the solubility of drugs or particles, leading to a higher loading efficiency of active agents or recovery rate of PNPs. Method IV, the solvent substitution method, requires two miscible solvents (Fig. 5D) and the obtained NPs are typically characterized by well-defined sizes (Zielińska et al., 2020).

Fig. 5.

Different methods of preparing PNP (Zielińska et al., 2020) (A) Scheme of the solvent evaporation method. The first step is to emulsify the mixture to form an oil/water emulsion, then is a solidification step to remove the organ solvent under vigorous stirring, and the final step is to harvest PNPs. (B) Schematic representation of the emulsification/solvent diffusion method. In the emulsification/solvent diffusion process, PNPs with sizes ranging from 80 nm to 900 nm are prepared after solvent diffusion; (C) Schematic representation of the emulsification/reverse salting-out method. Adding salt further decreases the solubility of the particles or drug, thus increasing the recovery of PNPs or the loading efficiency of the drug; (D) Schematic illustration of the nanoprecipitation method. This method needs two miscible solvents and forms NPs typically of well-defined size. Copyright © 2020, The Aleksandra Zieli Ñska (s).

In addition, PNPs possess stimulus-responsive features that enable them to change their physicochemical properties under specific microenvironments in the body, such as temperature, electrolyte strength, pH value, etc. These features confirm that PNPs have an optimistic prospect for the clinical application of smart DDSs (Wang et al., 2024). In the future, PNPs will make more significant breakthroughs in the fields of precision medicine and drug delivery. Their potential mainly characterizes the application of PNPs in orthopedics as a biomaterial. It can be used as a scaffolding material to guide the regeneration and repair of bone tissue. For example, nanoscale hydroxyapatite gradient-coated materials have been shown to increase the shear strength of the implant-bone interface, thereby promoting early healing at the bone trauma interface (Hou et al., 2022). It can be hypothesized from clinical studies that the combination of PNPs and PRP will offer a more effective therapeutic option in orthopedic treatment. The GFs in PRP can promote the bioactivity of PNPs, while the physicochemical properties of PNPs can enhance the biocompatibility and functionality of PRP. PRP can be more precisely targeted to the damaged area delivered by PNPs, thereby accelerating bone repair (Kiaie et al., 2020). In addition, the PNPs consisting of PEG-PLGA nanoparticles (PLGA NPs) did not change the platelet reactivity, such as activation and aggregation of PRP, as well as internalized capabilities of resting or activated platelets (Bakhaidar et al., 2020). PLGA NPs solve the related safety problems caused by the effect of delivery carriers on platelet function.

4.4. Others

In addition, as a standard biomedical material (Wang et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2009), porous chitosan, hydrogel, membranes and nanocomposite scaffolds are also used as delivery systems to load PRP. Sadeghinia et al. (Sadeghinia et al., 2019) explored the impacts of activated PRP (a-PRP) and fibrin glue (FG) on the proliferation of human stem cells from dental pulp (h-DPSCs) and osteogenic differentiation of h-DPSCs. They then selected the scaffold made of chitosan-gelatin/nano-hydroxyapatite (CS-G/nHA) for its porous nature as the ideal base to seed h-DPSCs. The h-DPSCs were implanted on porous composite scaffolds of CS-G/nHA. Four scaffolds were prepared to culture h-DPSCs in the study: a-PRP/CS-G/nHA, a-PRP-FG/CS-G/nHA, FG/CS-G/nHA, and CS-G/nHA as a control. The results showed that the a-PRP-treated and FG-treated composite scaffolds preferentially displayed fibronectin networks on their surface, enhancing the mineralization of harvested cells and osteoblast differentiation.

Additionally, the a-PRP-FG/CS-G/nHA composite scaffolds enhanced the expression of bone marker genes from week 1 to week 3. He et al. (He et al., 2022; Tramś et al., 2022) investigated the combined effects of PRP plasma-containing gel with chitosan nanocomposite membrane laden with bone marrow stromal cells on the promotion of wound healing. They applied its impact to the repair of burns in specific locations, specialized burns, and burns of various ages. They found that the complex could modulate the expression of targeted genes and pathophysiological processes involved in wound healing. Yan et al. (Yan et al., 2020) tested the application potential of injectable HA hydrogel containing autologous PRP to repair the defected cartilage. The medial femoral condyle of porcine was impaired in forming focal cartilage defects of varying critical sizes (Fig. 6A). In a 6-month evaluation of a porcine model, it was discovered that HA hydrogel containing PRP has the potential to facilitate cartilage healing. This was evidenced in osteochondral defects that were 5 mm deep and 6.5 mm in diameter and full-thickness cartilage defects that measured 8.5 mm in diameter, showing significant signs of regeneration. Of course, studies surfaced that PRP may interfere with nanoparticle applications in orthopedics (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The influence of HA hydrogel containing PRP-treated for porcine cartilage regeneration (A) The surgical procedure of cartilage and osteochondral defects. Repaired tissue was stained with HE dyes to show the interface changes of osteochondral and cartilage and repaired area. (B) Typically, images of the appearance of the repaired tissue are used (Yan et al., 2020). Copyright © 2019, © The Yan, Wenqiang; Xu, Xingquan (s) 2019. Published by Oxford University Press. The injectable composite system of PRP/cell-loaded microcarrier/hydrogel. (C) Scheme of release test of the growth factor. Cumulative release of FGF and injecting PRP-laden DECHS into nude mice. (D) Expression of DP signatures of and morphological analysis of DPCs on IGMs: The images of DPCs marked with DAPI, Ki67, and Phalloidin (Zhang et al., 2022b). Copyright © 2022, The Yufan Zhang(s).

Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2022b) developed gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)/chitosan-microcarriers (IGMs) containing PRP and seeded them with dermal papilla cells (DPCs) to imitate ECM. The IGMs with properties of appropriate swelling could sustain the release of GFs. Moreover, DPC/PRP-loaded IGMs were efficiently combined with epidermal cell (EPC)-loaded GelMA to create a PRP-laden DPC/EPC co-existed hydrogel system (DECHS). Afterward, this system was delivered to the subcutis of nude mice (Fig. 6C). The results have shown that the DECHS and IGMs effectively simulate a macro- and micro-environment that promotes DPC bioactivity (Fig. 6D). Kon et al. (Kon et al., 2010) added PRP to a novel multilayered gradient nanocomposite scaffold with hydroxyapatite NPs nucleating collagen fibers to investigate its role in the repair process of osteochondral defects in a sheep model. Animals were randomly grouped into the scaffold group, the scaffold containing PRP group, and the empty defect group (control). It was found that cartilage surface reconstruction and bone regeneration were significantly better in the scaffold-alone treatment group. Conversely, irregular cartilage surface integration and incomplete bone regeneration were observed in the PRP group. Cartilage and bone defects failed to heal for the control animals and were instead filled with fibrous tissue. Thus, this experimental surface hydroxyapatite-collagen scaffold promoted the repair of osteochondral lesions, but the addition of PRP interfered with the regeneration process and negatively affected the results. Therefore, the interactions of PRP with the components in the hydroxyapatite-collagen scaffold should be further clarified.

DDS development offers new PRP delivery strategies, but PRP formulation lacks a standard operating procedure (SOP), leading to variable platelet, WBC, RBC, and GF levels, which may affect clinical efficacy (Shome et al., 2024). Challenges also include DDS material selection and PRP loading and release mechanisms (Khandan-Nasab et al., 2025). Therefore, maintaining PRP component consistency and drug loading is crucial for clinical translation of PRP-contained DDS. Although there is currently no SOP for the preparation of PRP, there are various commercial PRP separation systems on the market that can achieve higher reproducibility in the preparation of PRP suspensions and reduce batch differences (Kevy and Jacobson, 2004; Lozada et al., 2001; Waters and Roberts, 2004). To control the content differences of PRP components, selecting single cytokine delivery that targets specific cell populations is a better choice to improve the quality of production, and also minimize delivery to non-targeted cells and tissues (Chen and Mooney, 2003; Khandan-Nasab et al., 2025). In addition, the development and application of microfluidics technology provides a solution for the robust production of DDS, by generating highly uniform carriers through fixed geometric shear fields and continuous processing (Rawas-Qalaji et al., 2023), thereby minimizing component fluctuations. These comprehensive methods ensure the key quality attributes of PRP-contained DDS and demonstrate the possibility of industrial expansion to some extent.

5. Clinical applications of PRP base on DDSs in orthopedics

5.1. Joint diseases

5.1.1. Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) hinders body movement and is a degenerative joint disease. Due to unsatisfactory biomechanics, OA often reduces quality of life (El-Kadiry et al., 2022). The common OA include temporomandibular joint (TMJ) OA and knee joint (KJ) OA. TMJ OA, an inflammatory disease of the TMJ and its surrounding tissues, is a low-grade, more severe temporomandibular disorder (TMD) (Lee et al., 2020). As a long-term degenerative disease, the pathologic features of TMJ OA are characterized by chondrocyte destruction, degradation of ECM and subchondral osteophytes, microcystic formation, osteoid formation, and concomitant synovial inflammation of varying degrees (Cardoneanu et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2022). The common symptoms include pain, stiffness, and the clicking sound that characterizes TMJ OA. Traditional surgical treatment methods may result in scarring, which can affect the appearance, and the facial nerve and parotid gland may also be affected. Thus, intra-articular injection is gradually gaining traction as a practical new approach to treat TMJ OA (Wu et al., 2022). The knee joint is a complex hinge joint composed of the distal femur, proximal tibia, patella, meniscus, free cartilage, ligaments, patellar fat pad, and synovium (Jang et al., 2021). The knee joint is also an essential tissue that stabilizes and supports the body in different postures. It has a motor function that allows people to perform some daily activities. Due to its high-frequency motion nature, the knee joint is prone to painful conditions, even developing knee osteoarthritis (KOA) (Gupta et al., 2021).

Meanwhile, trauma, aging, females, overweight, low bone density, muscle weakness, and joint laxity are also risk factors of KOA (Behzad, 2011). At present, the treatment of KOA mainly depends on physical therapy, such as physical factor therapy (shock wave therapy, infrared rays, iontophoresis, etc.), manipulative therapy (acupuncture, tuna, massage, etc.), and muscle-strengthening training (Lorenzo et al., 2021). Some medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs) or surgical interventions that include partial or total knee replacement and knee osteotomy (high tibial osteotomy or femoral osteotomy) can also be used in clinical for treating KOA (Szwedowski et al., 2021). Besides, intra-articular injection is also used in the management of KOA. Although intra-articular injection has better efficacy and fewer adverse effects compared with other treatments, there are some differences in the clinical impact of different injection drugs to treat OA.

Numerous novel treatments have been developed for OA, such as PRP, vitamin D, oral collagen, methylsulfonylmethane, and curcumin (Fuggle et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2022). Among these, PRP has exhibited clinical benefits in OA patients. Research has shown that PRP primarily exerts anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects by releasing various GFs and cytokines. These GFs and cytokines mainly include PDGF, TGF, VEGF, EGF, FGF, CTGF, IGF, HGF, angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), platelet factor 4 (PF4), SDF, and TNF (Everts et al., 2020). Studies have identified the roles and mechanisms of high concentrations of GFs and cytokines in PRP within OA through both in vitro and in vivo animal experiments, suggesting that these GFs and cytokines can serve as commercial alternatives to PRP (Cai et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2021). However, not all cytokines released by PRP are beneficial to OA. For example, VEGF, TNF-α, Ang-1, and SDF-1α may have negative impacts on OA (Table 5). Since these GFs, which may have a negative effect on PRP treatment of OA, limit the use of PRP in OA treatment, some studies have begun to try different strategies to avoid this negative effect. For example, Lee et al. (Lee et al., 2022) attempted to reduce unwanted biological activity by using GF-binding microspheres. They sequestered VEGF in PRP by using VEGF-binding microspheres, thereby developing a VEGF-attenuated PRP. Further research showed that the attenuation of VEGF in PRP not only did not inhibit the effects of PRP on the differentiation of stem cells for cartilage formation in vitro, but also significantly improved the healing of rat OA cartilage. Regarding the impact of TNF-α on the development of OA, studies have shown that in obese adults, serum TNF-α levels are elevated (Park et al., 2005) and obesity is positively correlated with the incidence of musculoskeletal diseases (Gnacińska et al., 2009). This research demonstrated a close relationship between obesity and OA (Xie and Chen, 2019). Therefore, when using PRP to treat OA, monitoring the TNF-α levels in PRP may be necessary.

Table 5.

Summary of cytokines in the PRP that are beneficial, detrimental, or unknown in OA treatment.

| Effects | Cytokines | Features | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | TGF-β | Reducing endogenous TGF-β led to less osteophyte formation and cartilage breakdown, while TGF-β aided in chondrocyte growth and cartilage preservation. | (Zhu et al., 2021) |

| TGF-β downregulated MAPK6 expression, leading to the polarization of M2 macrophages in the synovium. | (Bakker et al., 2001) | ||

| Exosomal miR-135b from TGF-β1-modified MSCs reduced cartilage damage by encouraging M2 synovial macrophage polarization through MAPK6 targeting. | (Wang and Xu, 2021) | ||

| PDGF | PDGF-AA might have enhanced proteoglycan synthesis in chondrocytes and aid in cartilage healing. | (Wang and Xu, 2021) | |

| PDGF-BB might have prevented chondrocyte apoptosis based on the p38/Bax/caspase-3 pathway. | (Andia and Maffulli, 2018) | ||

| PDGF-BB might have boosted the proliferation of chondrocytes and the production of cartilage matrix. | (Belk et al., 2021) | ||

| EGF and TGF-α | The anabolic function of articular cartilage was enhanced by stimulating the EGFR signaling pathway. | (Singh and Harris, 2005) | |

| OA was more severe in EGFR-deficient mice than in wild-type mice. | (Rayego Mateos et al., 2018) | ||

| Lowering EGFR activity caused articular cartilage to be structurally, functionally, and mechanically weakened. | (Pest et al., 2014) | ||

| The levels of HBEGF and TGF-α increased during the development of cell clusters post-cartilage damage. | (Long et al., 2015) | ||

| IGF-1 | IGF might have increased the production of proteoglycan and collagen II while decreasing the production of MMP-13 within rat endplate chondrocytes. | (Shepard et al., 2013) | |

| IGF-1 reduced the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to antiapoptotic effects. | (Wei et al., 2021) | ||

| Detrimental | VEGF | Blocking the effects of VEGF and its receptor in animal OA models might have slowed the disease's progression. | (Haywood et al., 2003) |

| PRP with reduced VEGF levels enhanced OA healing. | (Giatromanolaki et al., 2001) | ||

| TNF-α | TNF-α might have boosted the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and suppressed the production of proteoglycan and collagen II in chondrocytes, resulting in cartilage degeneration. | (Wang and He, 2018) | |

| Activated the NF-κB pathway promoting cartilage degradation. | (Murakami et al., 2000; Séguin and Bernier, 2003) | ||

| TNF-α might have lowered SOX-9 transcription factor expression and impaired respiratory chain efficiency. | (Jiranek et al., 1993; Merkel et al., 1999) | ||

| Ang-1 | Ang-1 stabilizes newly formed blood vessels by enlisting adjacent mesenchymal cells during VEGF-induced vessel formation. | (Park et al., 2005) | |

| SDF-1α | The SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway might have caused a disruption in the equilibrium of aggrecan within the cartilage of rats suffering from osteoarthritis. | (Zheng et al., 2017) | |

| The level of SDF-1 in the subchondral bone rose in OA, causing subchondral osteosclerosis to form. | (Kanbe et al., 2002) | ||

| The SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway might have reduced irregular bone growth and blood vessel formation. | (Lu et al., 2019) | ||

| Unknown | CTGF | The expression of CTGF was upregulated in OA cartilage, promoting inflammation and cartilage damage through NF-κB. | (Blaney Davidson et al., 2006; Omoto et al., 2004) |

| It interacted with TGF-β and VEGF signaling pathways, suggesting a potential dual role in OA. | (Bazzazi et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2011) | ||

| FGF | FGFR1 signaling promoted matrix degradation; FGFR3 signaling promoted anabolic activity. | (Im et al., 2007; Weng et al., 2012) | |

| Contradictory roles occurred due to different receptor activation; the overall effect on OA remained unclear. | (Xie et al., 2020a; Xie et al., 2020b) | ||

| HGF | HGF, released by different cells, was increased in osteoarthritis and aided in tissue repair and remodeling. | (Mabey et al., 2014; Nagashima et al., 2001) | |

| Overexpression activated the c-Met pathway, inducing extracellular matrix degradation. | (Que et al., 2022) |

In exploring the potential effects of PRP on improving bone marrow mesenchymal-stromal-cells (BMSCs)’ regenerative capability, Ragni et al. (Ragni et al., 2022) identified 105 soluble factors and 184 EV-miRNAs in the secretome of PRP-treated BMSCs, respectively. Among them, several EV-miRNAs exhibited an immunomodulating capability at both the cell and the single-factor level and the ability to target enzymes that degrade the ECM characteristic of OA and pathways contributing to cartilage destruction. The data demonstrated that BMSCs incubation with PRP released therapeutic agents with strong anti-inflammatory capacity and provided a molecular basis for innovative therapies for OA treatment. Arafat and Kamel found that PRP combination therapy may have better outcomes than PRP alone (Zhang et al., 2022a). In a meta-analysis of clinical practice, the controlled clinical trial compared the efficacy of PRP with that of corticosteroids, HA, or placebo in treating knee OA (KOA) at 3, 6, and 12 months after administration, respectively. The data supported that PRP had the best overall results (Rodríguez-Merchán, 2022). Not coincidentally, a follow-up trial of 959 patients with KOA was mentioned in a literature review by Li et al. At 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after PRP injections, total knee scores of patients were recorded, respectively. The group treated with PRP improved significantly than the baseline (Li et al., 2022). This study further proves that PRP helps promote tissue repair and reduce inflammation.

Although PRP has shown considerable effectiveness in the clinical management of OA, the enduring efficacy and safety of PRP warrant further study; in addition, PRP and its derivatives may affect the catabolism and inflammatory process of KOA, and the acceptability of different concentrations of PRP to individuals and the side effects of PRP are still urgent issues. More and more studies have chosen the DDSs, especially the PRP-EVs, to deliver PRP for the treatment of OA, and some animal experiments have been conducted. For example, Guo et al. observed the skin healing process of chronic wounds subjected to therapy with PRP-Exosomes in a diabetic rat model. Importantly, this study pioneered the demonstration of the feasibility of using exosomes to perform the function of PRP (Guo et al., 2017; Tao et al., 2017). The therapeutic roles of PRP-Exos in OA are mainly reflected in the promotion of chondrocyte migration and proliferation, the reduction of chondrocyte apoptosis and hypertrophy, and the inhibition of the release of inflammatory factors (Zhang et al., 2022a). Moreover, cross-species communication based on EVs has been reported multiple times. For instance, EVs derived from the human liver stellate cell line LX2 have been used in rat models (Li et al., 2017), and EVs derived from human MSCs have been applied in mouse and rat models (Monsel et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). This species-specific PRP-Exos undoubtedly offers a promising research direction for the treatment of OA, especially considering the demonstrated potential of EVs in cross-species therapeutic applications. Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2019) established an IL-1β-provoked OA model and determined whether activated PRP (PRP—As) and PRP-Exos exhibited analogous biological effects in the management of OA. In in vitro experiments, they used primary rabbit chondrocytes to establish an OA model. They evaluated the therapeutic effects of PRP-As and PRP-Exos on OA through proliferation, migration and apoptosis assays. Results showed that PRP-Exos were statistically superior to PRP—As. Additionally, they aimed to confirm further that PRP-Exos alleviates OA through the Wnt/β-catenin cascade reactions. A KOA model was established to compare the therapeutic effects of PRP-Exos and PRP-As in vivo. The findings indicated that both PRP-Exos and PRP-As exhibited therapeutic effects on OA; however, the efficacy of PRP-Exos surpassed that of PRP—As, as evidenced by chondrocyte counts and the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scoring system. In summary, PRP-Exos acted as a carrier and contained PRP-derived GFs in this study, providing a new therapeutic approach to OA by triggering the Wnt/β-catenin cascade reactions. PRP-EVs not only attenuate OA by reducing the expression of TNF-α but also reverse the OA-induced down-regulation in type II collagen level and up-regulation of Wnt5a protein.

In fact, in addition to the study of mouse/rabbit OA models, dogs (Estes et al., 2021; Meeson et al., 2019), sheeps (Lovati et al., 2020), horses (Kupratis et al., 2022; van Loon and Macri, 2021) and other animals have also been used for the development of OA animal model. In contrast, the joint anatomy, cartilage morphology, and biomechanical function of these large animals are similar to those of human joints, providing more meaningful data for further clinical research. However, due to the complexity and heterogeneity of OA, the animal models currently used to replicate OA cannot fully reproduce the symptoms and pathological characteristics of human OA. This limitation has led to a lack of translational effects in most studies on OA treatment and the clinical outcomes of drugs in human subjects. Compared with in vivo models, in vitro engineered OA models are gaining increasing attention as a new frontier in OA research, including application such as tissue culture (Geurts et al., 2018), multicellular/tissue co-culture (Louer et al., 2012), 3D cell culture (Makarczyk et al., 2021), microtissue construction (Brandenberg et al., 2020), microphysiological systems, and organoids (Brandenberg et al., 2020; Hofer and Lutolf, 2021; Molinet et al., 2020; Schutgens and Clevers, 2020). For instance, Peng et al. (Peng et al., 2023) recently evaluated the therapeutic potential of human PRP and hyaluronic acid (hPRP/HA) in treating TMJ-OA from laboratory to human treatment. They investigated the effects and underlying mechanisms of hPRP/HA therapy for TMJ-OA in animal models, as well as conducted in vitro experiments (including 3D models) and clinical trials in patients with TMJ-OA. This study provides comprehensive evidence for the application of hPRP/HA in TMJ-OA treatment, spanning from the laboratory to the clinic and from animals to humans. Even though in vitro engineered OA models face many challenges and are expected to become a crucial model for clinical translation, they are merely prototypes that cannot replicate the entire structure of human bones and joints or create a physiological environment consistent with human OA (Dou et al., 2023). Recently, the integration of technologies such as genome editing, single-cell RNA sequencing, and lineage tracing has advanced the development and improvement of engineered OA models (Tong et al., 2022). It is anticipated that in the near future, a robust, physiologically relevant, and stable OA model will fundamentally transform drug development and testing. Such a model will provide more reliable and stable preclinical data for clinical trials of OA treatments.

To overcome the low retention rate and short therapeutic duration of PRP-Exos, Zhang et al. incorporated PRP-Exos into a thermosensitive hydrogel (Gel), aiming to increase the retention of PRP-Exos in joints. The results showed that this strategy enhanced cartilage protection after joint instability (Zhang et al., 2022a). Mata et al. (Mata et al., 2024) prepared gelatin/PRP microdroplets using an emulsion method to study the effects of platelet-derived GFs on the differentiation of MSCs into hyaline cartilage cells in a 3D environment. Subsequently, bone marrow MSCs were cultured in a microgel containing cartilage cells and combined with gelatin/PRP. In this study, gelatin microspheres effectively encapsulated PRP, significantly promoting the secretion and release of cartilage differentiation-promoting factors. Simultaneously, the microgel provided a 3D microenvironment, offering a surface for cell adhesion and the possibility of 3D cell-to-cell interactions. In summary, PRP delivery strategies for OA treatment offer advantages such as controlled drug release kinetics and tissue-specific targeting. It is foreseeable that drug delivery strategies will have more research and application in treating OA shortly.

5.1.2. Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a refractory autoimmune disease of synovial joints (Perera et al., 2024; van Delft and Huizinga, 2020). If left untreated, RA would lead to progressive corrosive joint damage, excessive comorbidities, and increased mortality (Myasoedova, 2021). RA is marked by infiltration of immune cells in the joints, which may cause inflammation, pain, edema, and joint degeneration. Up to now, some cascade signals in RA pathogenesis have been clarified, such as the T cell receptor (TCR) signal path and the CD40 signal path (Hasanov et al., 2018; Yanxia et al., 2017). Since the human leukocyte antigen DRB1 (Part of the primary histocompatibility complex class II receptor) is expressed in antigen-presenting cells (APCs), the interaction between APCs and CD4+ T cells via DRB1 could play a central role in RA pathogenesis (Viatte and Barton, 2017). The pathological changes of RA demonstrate the two sides of the autoantibody presence, which can either exacerbate the disease by promoting an inflammatory response and destroy tissue structure or help the diagnosis and treatment by acting as an indicator of disease severity or a potential therapeutic target, such as the expression of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and rheumatoid factor (Rantapää Dahlqvist et al., 2003).

Local clinical manifestations of RA include joint deformities (gooseneck deformity, knob deformity, etc.), rheumatoid nodules, and rheumatoid vasculitis. In contrast, systemic clinical manifestations include symmetric polyarticular swelling and pain, morning stiffness, and weight loss. Its treatment principles include early treatment, the combination of drugs, and individualized treatment. Commonly used clinical drugs include NSAIDs, anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticosteroids, and so on (Lin et al., 2020). Despite significant advances in the treatment of RA, approximately 40 % of RA patients do not respond to drugs, and up to 20 % do not respond to any of the available medications (Perera et al., 2024). Additionally, the conventional treatments still have other shortcomings. For example, although methotrexate (MTX) is an excellent drug in the management of RA, it does not accumulate well at the site of inflammation. Long-term exposure to high doses of MTX can lead to serious side effects, whereas their concentration at the site of inflammation can not be controlled (Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches to reduce inflammation and protect bone tissue by modulating and inhibiting inflammatory mediators should be further explored.

The data have supported the idea that PRP actively removes inflammatory factors and promotes cartilage matrix recovery. Although the effects of PRP on OA have been recognized, RA is still significantly different in terms of pathological mechanisms from OA. In existing studies, it has been continuously verified that PRP can be used to manage RA disease. Saif et al. (Dalia et al., 2021) compared the outcomes between patients with monthly intra-articular steroids and those with PRP injections 3 times per month by the controlled variable method. The results showed that PRP was superior to steroids and had a more substantial inhibitory effect on the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, which improved local joint inflammation, quality of life, and disease activity. Amanda et al. (Amanda Bezerra et al., 2021) evaluated the effects of photobiomodulation (PBM) and PRP on the inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters of acute arthritis in Wistar rats. It was concluded that PBM, in combination with PRP, had better anti-inflammatory and joint protective effects. Tong et al. (Tong et al., 2017b) investigated that PRP was used to treat type II collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in mice. The data exhibited that the signs of arthritis, concentrations of anti-collagen antibodies, were decreased, accelerating tissue repair. This study has demonstrated that PRP can alleviate arthritis and reduce humoral and cellular immune responses. In another study by his team, rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocyte MH7 A cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to mimic the RA condition. The results showed that PRP can inhibit synoviocyte fibroblasts and modulate PI3K/Akt signals (Tong et al., 2017a). From the experiments described above, PRP can adjunctively treat RA by down-regulating inflammatory cytokines and suppressing synovial fibroblasts (Dejnek et al., 2022).