Summary

Forest pests and diseases pose serious threats to the sustainable development of forestry. Plants have developed effective resistance mechanisms through long‐term evolution. Jasmonic acid and terpenoids play important roles in the defence response of plants against insects. Here, we discovered a transcription factor of the WRKY IIa subgroup, BpWRKY6, which is located in the nucleus, and the overexpression of BpWRKY6 in birch (Betula platyphylla) can increase resistance to gypsy moths (Lymantria dispar). The selective feeding results indicated that the gypsy moth tends to feed more on wild‐type (WT) and mutant birch. The overexpression of BpWRKY6 decreased feeding, delayed development, inhibited CarE activity, and increased the activities of GST and CYP450 in gypsy moth larvae, whereas gypsy moth larvae that fed on the mutant birch presented the opposite trend. Further analysis revealed that BpWRKY6 directly binds to the promoters of jasmonic acid (JA) synthesis genes, including BpLOX15, BpAOC4, and BpAOS1, and the terpenoid synthesis gene BpCYP82G1, promoting their expression and increasing the contents of JA, 4,8,12‐trimethyltrideca‐1,3,7,11‐tetraene (TMTT) and total terpenoids, thus affecting birch resistance to insects. In addition, BpWRKY6 was phosphorylated as a substrate for BpMAPK6, suggesting that BpWRKY6 functions through the MAPK signalling pathway. In conclusion, this study further improves the understanding of the insect defence response mechanism of plants to achieve green pest control and provide insect‐resistant germplasm resources.

Keywords: Betula platyphylla, biotic stress, Lymantria dispar, WRKY

Introduction

Owing to the fixed growth of plants, they are unable to avoid the harm of pests through ‘escape’. During the long process of biological evolution, plants have developed powerful defence mechanisms. The defence mechanisms of plants can be divided into constitutive and inducible mechanisms (Sun et al., 2023). Constitutive defence refers to the growth characteristics of plants that hinder pest feeding, such as the thorns or hairs of plants (Balakrishnan et al., 2024). Inducible defence reactions can be divided into two types: indirect and direct defences. Indirect defence refers to the synthesis and release of a volatile substance by plants to attract natural enemies of pests, thereby achieving the goal of ‘killing pests’. Direct defence refers to the production of defence proteins and secondary metabolites, which directly kill or interfere with the growth and development process of pests, thereby reducing their harm (Kessler, 2017).

Various metabolic substances synthesized by plants are reportedly associated with plant–insect defence responses. Guo et al. (2019) reported that Ostrinia furnacalis significantly induced the synthesis of benzooxazine metabolites in plants after the insects were fed corn, and when the leaves were fed to the corn borer again, the growth and development process of the corn borer was affected. Cao et al. (2022) reported that knockout of the SlJIG gene reduced the terpene content in tomato, and the expression of jasmonic acid (JA)‐reactive defence genes was reduced, attenuating tomato resistance to Helicoverpa armigera and the fungus Botrytis cinerea. Products of the lipoxygenase (LOX) and terpenoid pathways, including monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, diterpenoids, and homoterpenes, are important substances involved in indirect plant defence responses (Arimura et al., 2004). Kanda et al. (2023) reported that overexpression of the BSR1 gene in rice leads to the accumulation of diterpenoid plant antitoxins, increasing resistance to Mythimna loreyi larvae. Stack et al. (2023) reported that terpenoid cannabinoids mediate the defence responses of plants against many herbivorous insects, including Pieris brassicae, Tribolium confusum, Oryzaephilus surinamensis, and Plodia interpunctella. Guan et al. (2024) reported that CmMYC2 interacts with CmMYBML1 to mediate the formation of trichomes and the synthesis of terpenoids in Chrysanthemum, thereby increasing resistance to Spodoptera litura larvae.

JA is believed to play an important role in plant defence responses to insects (Schuman et al., 2018). Research has shown that the synthesis of JA begins with the octadecane pathway of linolenic acid and the hexadecane pathway of hexadecanoic acid. After the catalysis of LOXs, allene oxide synthase (AOS), and allene oxide cyclase (AOC), several beta‐oxidations subsequently form JA (Monte, 2023). Some transcription factors (TFs) are considered core regulatory factors of the JA pathway branch (Du et al., 2017). Among them, the WRKY family was found to be involved in the transcriptional regulation of the JA pathway. For example, MaWRKY26 directly binds to the promoters of the MaLOX2, MaAOS3, and MaOPR3 genes to activate their expression, mediating cold tolerance in bananas through the JA pathway (Ye et al., 2016). Heterologous transformation of TaWRKY42‐B into Arabidopsis promotes the accumulation of JA, and further research has revealed that TaWRKY42‐B interacts with AtLOX3 and its homologous genes, mediating the process of leaf ageing (Zhao et al., 2020).

The WRKY family constitutes one of the largest TF families in plants, and many reports indicate that the WRKY family plays an important role in plant responses to biotic stress (Wani et al., 2021). The WRKY family is divided into three subfamilies (I, II, and III), and both the II and III subfamilies contain two subgroups, namely, Group a and Group b (Wang et al., 2011). The members of group IIa are believed to be associated with the biotic stress responses of plants. For example, some members of the IIa subgroup, including WRKY18, WRKY40, WRKY60, WRKY61, and WRKY42, play important roles in the response of plants to pathogen infection (Abeysinghe et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022). Other members of the IIa subgroup, including WRKY36, WRRKY72, WRKY31, and WRKY6 play important roles in plant resistance to insects (Batool et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). However, these reports focused on herbs, and the mechanisms underlying their involvement in biotic stress responses still need to be further explored in woody plants.

Mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades constitute one of the key primary signalling pathways in plant–insect resistance defence. MAPKs are the terminals of the MAPK pathway and regulate the plant defence response by transmitting signals downward through substrates such as various kinases and TFs (Hettenhausen et al., 2015; Xu and Zhang, 2015). In cotton, GhMPK31 regulates the ROS pathway by interacting with GhRBOHB, which affects the resistance of Gossypium hirsutum to H. armigera and S. litura (Wang et al., 2024). In tomatoes, simultaneous silencing of MPK1/2 affects the expression of JA synthesis‐related genes, thereby reducing the level of JA and reducing resistance to Manduca sexta (Kandoth et al., 2007). Research suggests that many WRKY proteins may act as substrates for MAPK (Sheikh et al., 2016). However, little is known regarding the role of MAPK‐WRKY interactions in the insect resistance of woody plants.

The gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) is a highly destructive forest pest that eats plants or promotes defoliation, leading to reduced tree vigour and resistance and resulting in indirect or direct tree death and severe economic losses (Fajvan and Wood, 1996). The gypsy moth is an omnivorous moth that is widely distributed and threatens more than 600 plants (Srivastava et al., 2020). The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) proposed that it is one of the most destructive invasive organisms worldwide (Boukouvala et al., 2022). For example, Quercus robur L. is the most important tree species in Croatian forests and is the main host of the gypsy moth, which has been reported to have experienced major outbreaks over several decades, causing serious losses to local forestry production (Pernek et al., 2008).

Birch (Betula platyphylla) is widely distributed throughout East Asia and is an important pioneer tree for afforestation. Birch also suffers from gypsy moths during its natural growth (Matsuki et al., 2021). Compared with chemical, physical, and biological control, enhancing plant resistance to insect pests is a convenient and green pest control strategy (Erazo‐Garcia et al., 2021). Therefore, this study intends to use birch as the research object and explore the role of BpWRKY6 in the insect resistance defence response of birch using molecular biology methods, laying a theoretical foundation for the cultivation of new insect‐resistant germplasm resources.

Materials and methods

Experimental materials

Birch seedlings were grown in a greenhouse at an average temperature of 25 °C, a relative humidity of 70%, and a light–dark cycle of 16/8 h. Two‐month‐old seedlings were treated with 100 μM JA sprayed on their leaves for 6, 12, 24, or 48 h. An equal volume of solvent was sprayed as a control. The plant materials were collected at the same time for the next experiment. Each treatment included three seedlings, and three independent biological replicates were performed.

The egg mass of the gypsy moth was obtained from the Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment, and Protection, CAF, and was stored at 4 °C before hatching. The gypsy moths were maintained in the laboratory without exposure to pesticides. The egg masses of the gypsy moth were soaked in a 10% formaldehyde solution for 25 min, rinsed with water for 15 min, and then dried before being placed in a clean, sterile, disposable plastic container with a volume of 150 mL. The hatched larvae were reared with fresh artificial diets replaced daily in a room at 25 ± 1 °C with a photoperiod of 14 h/10 h and a relative humidity of 75%. The artificial diet was prepared according to the methods of Wang et al. (2019b), and included feed powder (20 g), distilled water (80 mL), and agar powder (1.6 g).

RNA extraction and quantitative real‐time PCR

The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method was used to extract total RNA from birch according to Zeng et al. (2007). 1 μ g of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a TransScript® One‐Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech) and then diluted tenfold for qRT–PCR. The α‐tubulin (FG067376) and ubiquitin (FG065618) genes were used as reference genes for qRT–PCR. The reaction procedure followed that outlined by Dong et al. (2023). The primers used can be found in Table S1.

Sequence analysis

The promoter sequence and full‐length coding sequence (CDS) of BpWRKY6 were obtained from the birch genome (Chen et al., 2021). The members of the WRKY IIa subgroup were searched in birch using BLAST on the basis of the classification of the WRKY family in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2011). Seventy‐two WRKY members from Arabidopsis were used to construct a phylogenetic tree with BpWRKY6 via MEGA‐X. PlantCARE (https://bioinformatics.psb.uge‐ nt.be/webtools/plantcare−/html/) was used to analyse the cis‐elements of the promoter. Twelve WRKY genes from Arabidopsis, rice, and tomato with high homology to BpWRKY6 were subjected to multisequence alignment by Bioedit to explore the sequence conservation between BpWRKY6 and WRKY genes from other species.

Subcellular localization

Plant‐mPLoc 2.0 (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant‐multi/) was used to predict the subcellular localization of BpWRKY6. The full‐length CDS of BpWRKY6 from cDNA was cloned and connected to the pBI121‐GFP vector, after which it was transferred to Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101). The primers used can be found in Table S1. With an empty vector as a control and DAPI as a nuclear localization signal, the control and recombinant vectors were transformed into tobacco. After 48 h, the fluorescence was observed by a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 800).

Transcription activation activity analysis

The full‐length CDS of BpWRKY6 was constructed in pGBKT7 to generate pGBKT7‐BpWRKY6. In accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, yeast experiments were conducted using the Yeast Transformation Kit (Coolaber) to convert pGBKT7‐BpWRKY6 into the yeast Y2H Gold strain. The strain was incubated at 30 °C on SD/−Trp media for 3 days, followed by screening on SD/−Trp/‐His/X‐α‐Gal media.

Obtaining transgenic BpWRKY6 birch

The full‐length CDS of BpWRKY6 was cloned from cDNA, and the pCAMBIA1300‐3 × Flag vector was linearized with XbaI and KpnI and linked by T4 ligase. Finally, the constructed pCAMBIA1300‐BpWRKY6 was transferred to Agrobacterium. Two sgRNAs of BpWRKY6 were screened and inserted into the pHSE‐401 gene editing system. And transgenic plants were obtained through the leaf disc method according to Jia et al. (2022). After the resistant seedlings were obtained, DNA and RNA were extracted and subjected to PCR and qRT–PCR detection. The primers used are listed in Table S1.

Feeding experiment and physiological measurements

The feeding behaviour of gypsy moth larvae was evaluated via the method of Sun et al. (2022). Briefly, the third fully unfolded leaf from 2‐month‐old cultivated birch seedlings was collected with similar growth and placed into Petri dishes containing wet filter paper and absorbent cotton at the seedling petiole. The 3rd instar larvae were randomly placed in Petri dishes containing control or transgenic plant leaves and were allowed to feed for 24 h. The leaf area was subsequently measured using ImageJ (V 1.53 t) to calculate the selective antifeedant rate. Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment, and 10 larvae were randomly selected from each treatment. For nonselective feeding analysis, 10 second instar larvae were randomly fed leaves of the control and transgenic lines in Petri dishes. After 24 h of feeding, the leaf area and nonselective antifeedant rate were determined.

The third fully unfolded leaf of similar growth conditions was selected to determine larval development, and the control and transgenic leaves were placed separately in Petri dishes. The 20 newly hatched larvae were placed in each treatment, and the leaves were renewed every 24 h. After 7 days, the larvae were photographed and recorded.

In accordance with the methods of Wang et al. (2019b), third instar larvae were starved for 24 h before feeding and then fed leaves from the transgenic and control plants under similar growth conditions. After 24 h, the larvae were collected to determine glutathione S‐transferase (GST), carboxylesterase (CarE), and cytochrome P450 (CYP450) activity. The activities of GST and CarE were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). The activity of CYP450 in larvae was determined via an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Shanghai Enzyme Linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Transcriptome analysis

RNA‐seq analysis was performed on overexpressed birch plants. The construction of a cDNA library and transcriptome sequencing were carried out via biomarkers (Beijing, China). The raw data were filtered by fastp (Chen et al., 2018) to remove low‐quality reads and connector sequences. Clean data were aligned to the genome using Samlon (Patro et al., 2017), differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified via DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), and |log2 FC| > 1 and P < 0.05 were used as screening criteria. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed via a cluster profile (Wu et al., 2021).

Determination of JA and total terpenoid contents

The third fully extended leaves of the overexpressing, mutant and control plants were collected to measure the JA and total terpenoid contents. The endogenous JA contents were determined by ultrahigh‐performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC‐MS/MS) following the methods of Shi et al. (2024). The contents of 4,8,12‐trimethyltrideca‐1,3,7,11‐tetraene (TMTT) were determined via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) according to the methods of Zhao et al. (2024).

The total terpenoid content was determined according to the methods of Łukowski et al. (2022). In short, linalool was used as a standard, and a standard curve was drawn. Fresh plant materials were weighed and ground. The mixture was extracted with 3.5 mL of 95% methanol for 48 h. Two hundred microlitres of the supernatant was mixed with 1.5 mL of chloroform. The mixture was allowed to stand for 3 min at room temperature, 100 μL of H2SO4 was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h (standard solution incubation for 5 min) to generate a reddish‐brown precipitate. The supernatant was discarded, and the reddish‐brown residue was dissolved in 1.5 mL of 95% methanol. The absorbance at 538 nm was measured, and the total terpenoid content was calculated on the basis of the standard curve.

Yeast one‐hybrid

The full‐length CDS of BpWRKY6 was inserted into pGADT7‐Rec2, and the promoter fragments containing the W‐box motif were inserted into the pHIS2 vector. Yeast experiments were conducted using the Yeast Transformation Kit (Coolaber) to convert pGADT7‐Rec2‐BpWRKY6 into the yeast Y187 Gold strain according to the manufacturer's instructions, which were cultivated on SD/−Trp/−Leu and SD/−Trp/−Leu/‐His+50 mM 3‐AT (3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole) media. The primer sequences are given in Table S1.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was conducted according to the methods of Xie et al. (2023b). First, 4–6 g of overexpressed plant material was cross‐linked. Second, the cell nucleus was extracted, and ultrasound was used to break up the chromatin. Then, antibodies were used to enrich specific fragments, and the enriched DNA fragments were extracted. The obtained ChIP product was directly used for ChIP–qPCR, with the α‐tubulin (FG067376) and ubiquitin (FG065618) genes used as internal references, and enrichment efficiency was calculated via the fold enrichment method (Tariq et al., 2003).

Dual‐luciferase assay

The promoter fragments of BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, BpAOS2, and BpCYP82G1 were inserted into the pGreenII‐0800‐LUC vector as effector vectors. pBI121‐BpWRKY6‐GFP was used as an effector vector, and the empty vector was co‐transformed into tobacco as the control. The determination of LUC enzyme activity was carried out according to the instructions of the dual‐luciferase reporter gene assay kit (Beyotime).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The full‐length BpWRKY6 gene was cloned and inserted into the pMAL‐c5x vector, which was subsequently transferred into the competent cell line ER2523 of the Escherichia coli expression strain for in vitro protein induction. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) probe biotin labeling kit was used to label promoter fragments containing W‐box motifs (Beyotime). A chemiluminescent EMSA kit was used to detect biotin‐labelled EMSA probes (Beyotime). The primer sequences are given in Table S1.

Yeast two‐hybrid

The full‐length sequence of BpMAPK6 was inserted into the pGADT7‐Rec vector. Yeast experiments were conducted using the Yeast Transformation Kit (Coolaber) to convert pGBKT7‐BpWRKY6 and pGADT7‐BpMAPK6 into the yeast Y2H Gold strain according to the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were then coated on QDO (SD/−Leu/−Trp/‐His/−Ade) and QDO/X/A (SD/−Leu/−Trp/‐His/−Ade/X‐α‐Gal) media and incubated upside down at 30 °C for 3–5 days.

Pull‐down

The full‐length sequence of BpMAPK6 was inserted into the pGEX‐4 T‐1 vector. Then, overnight induction of the MBP‐BpWRKY6 and GST‐BpMAPK6 recombinant proteins was performed using 0.1 mM IPTG at 28 °C. The recombinant proteins were purified and coincubated. The interaction between two proteins was detected through the use of MBP‐specific antibodies.

In vitro phosphorylation

For in vitro induction and purification of the MBP‐BpWRKY6, MBP‐BpWRKY6S253A, MBP‐BpWRKY6S288A, MBP‐BpWRKY6S253A/S288A, and GST‐BpMAPK6 recombinant proteins, MBP‐BpWRKY6s were incubated with the GST‐BpMAPK6 protein with 50 μM ATP for 30 min at 30 °C, after which phosphorylation of BpWRKY6 was detected using the Phos‐tag biotin BTL‐105.

Statistical analysis

Student's t‐test was used to distinguish the differences between the control and treatment groups via SPSS v22.0. * represents a P‐value < 0.05, ** represents a P‐value < 0.01.

Results

Expression analysis of BpWRKY6

Eleven WRKY genes (including BpWRKY6) were identified as belonging to the IIa subgroup. The expression patterns of these genes in the leaves of birch after feeding by the gypsy moth larvae were subsequently analysed. The results revealed that the expression of four genes did not significantly vary. In addition, the expression of seven BpWRKY genes was obviously altered, two genes were significantly suppressed, and five WRKY genes were induced. Among these genes, BpWRKY6 presented the highest expression level (Figure S1).

The expression patterns of BpWRKY6 in birch leaves were further analysed after the leaves had been consumed to different extents (I, II, and III) by gypsy moth larvae. The results revealed that the highest expression level occurred when the leaf area consumed by the gypsy moth accounted for less than a quarter of the total area (Figure 1a,b). The defence response induced by JA plays a crucial role in the plant response to herbivore attacks (Li et al., 2022). Therefore, additional analysis was conducted on the expression profile of BpWRKY6 under MeJA treatment. The results revealed that the expression level of BpWRKY6 continued to increase under MeJA treatment for 24 h (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Analysis of BpWRKY6 gene expression pattern. (a) Schematic diagram of the leaf area fed by the larvae of the gypsy moth. (b) BpWRKY6 expression pattern after feeding on leaves by the gypsy moth. (c) BpWRKY6 expression pattern after treatment with MeJA. * represents P‐value < 0.05, ** represents P‐value < 0.01.

Characterization of the BpWRKY6 sequence and protein characteristics

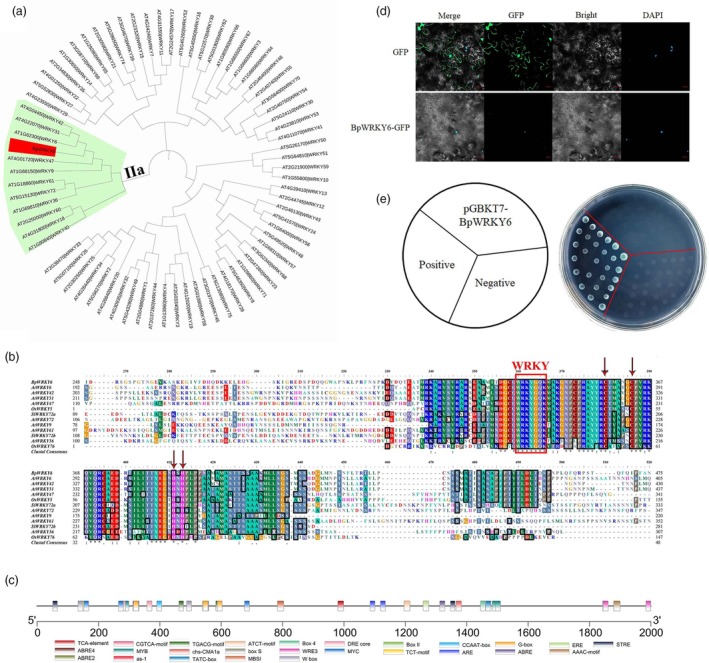

In Arabidopsis, there are 72 WRKY family members, and phylogenetic tree analysis of BpWRKY6 and 72 AtWRKY family members revealed that BpWRKY6 belongs to the IIa subgroup (Figure 2a). BpWRKY6 is closely related to AtWRKY6; in addition, AtWRKY31 and AtWRKY42 belong to the same branch. Furthermore, multiple sequence alignment was performed with BpWRKY6 and 12 genes with high homology from Arabidopsis, rice, and tomato, and the results revealed that they contain a complete WRKY domain and a typical C2H2 zinc finger structure, with the highest homology with AtWRKY6 (Figure 2b). Therefore, the WRKY gene in birch was named BpWRKY6. AtWRKY6 is involved in oxidative stress, low‐Pi stress, plant senescence, and pathogen defence (Jiang et al., 2017; Robatzek and Somssich, 2002).

Figure 2.

BpWRKY6 sequence characteristics analysis. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of BpWRKY6 and WRKYs in Arabidopsis. (b) Multiple sequence alignment analysis of WRKYs between BpWRKY6 and other species. (c) Cis‐elements in the promoter sequence of BpWRKY6. (d) Subcellular localization analysis of BpWRKY6. (e) Transcription activation activity analysis of BpWRKY6.

Analysis of the BpWRKY6 2000 bp promoter (DNA sequence upstream of the gene start codon) revealed that multiple cis‐elements, such as ABRE, G‐box, DRE core, CGTCA motif, and W‐box, are distributed in the region and are involved in stress and hormone responses (Figure 2c). ABRE and DRE cis‐elements play important roles in the response to abiotic stress (Kim et al., 2011). The CGTCA motif, also known as the JA responsive element, is regulated by JA (Wang et al., 2019a). These sequence characteristics and expression patterns indicated that BpWRKY6 may play a role in the response to JA, abiotic and biotic stresses in birch.

Plant‐mPLoc 2.0 predicts that BpWRKY6 is located in the nucleus. To further confirm the subcellular localization information, BpWRKY6 was fused with GFP and transiently transformed into tobacco; 35S:GFP was used as a control. The results revealed that the fluorescence produced by 35S:GFP was nonnuclear specific. The green fluorescence generated by the BpWRKY6‐GFP completely overlapped with that generated by DAPI (Figure 2d), indicating that BpWRKY6 is located in the nucleus.

To determine whether BpWRKY6 has transcriptional activation activity, the full‐length CDS of BpWRKY6 was inserted into the pGBKT7 vector and transformed into Y2H yeast cells for transcriptional activation activity analysis. The results revealed that the positive control grew normally and turned blue on SD/−Trp/−His/X‐α‐Gal media, whereas the negative control and pGBKT7‐BpWRKY6 strains did not grow (Figure 2e). These findings indicate that BpWRKY6 does not have transcriptional activation activity.

Overexpression of BpWRKY6 enhances insect resistance to birch

To further analyse the function of BpWRKY6, BpWRKY6‐overexpressing birch lines and mutants were generated. Three BpWRKY6‐overexpressing birch lines (OE1, OE2, and OE3) with the highest expression levels of BpWRKY6 were selected for further resistance assays in gypsy moth larvae (Figure S2). In the BpWRKY6 mutant, the first target site has a deletion of 6 bp, and the second target site has a deletion of 4 bp, which leads to premature translation termination and encodes only 162 amino acids (Figure S2d). The results of selective feeding revealed that compared with those of the control, the consumption of OE lines by the larvae significantly decreased (P < 0.05), and there was no significant difference between the mutant and the control (Figure 3a). The selective antifeedant rates were 22.79 ± 6.74%, 23.42 ± 6.45%, and 20.37 ± 6.43%, respectively. The selective antifeedant rate of the mutant was 1.78 ± 4.45% (Figure 3b). After 7 days of feeding, the gypsy moth larvae that consumed the overexpressing leaves became significantly smaller than those that consumed the control leaves, whereas the larvae grew normally after feeding on the mutant leaves (Figure 3c). The results of nonselective feeding revealed that the consumption of BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines by larvae was significantly lower than that of the control (P < 0.01), with 81.05 ± 4.40%, 77.69 ± 11.11%, and 77.09 ± 9.91% nonselective antifeedant rates, respectively. The nonselective antifeedant rate of the mutant was 3.82 ± 6.96% (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Monitor and comparison of the insect resistance of BpWRKY6 transgenic birch and control birch. (a) Selective‐feeding experiment between leaves of BpWRKY6 transgenic birch and control. (b) Selective antifeedant rate of gypsy moth larvae feeding on control and BpWRKY6 transgenic birch leaves. (c) Development of larvae feeding on control and transgenic leaves for 7 days. (d) No‐selective antifeedant rate of gypsy moth larvae feeding on control and BpWRKY6 transgenic birch leaves. (e) JA content analysis in BpWRKY6 transgenic birch and control. (f–h): Analysis of GST activity (f), CarE activity (g), and CYP450 activity (h) in gypsy moth larvae feeding BpWRKY6 transgenic birch and control leaves. * Represents P‐value < 0.05, ** represents P‐value < 0.01.

Previous studies have shown that members of the WRKY family regulate the JA pathway to mediate biological processes in plants, which play crucial roles in plant–insect defence responses (Li et al., 2022). Therefore, the JA contents of the overexpressing and mutant lines after feeding by the gypsy moth larvae were determined. The results revealed that the JA content of the BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines was 1.84‐, 2.66‐, and 3.30‐fold greater than that of the control, respectively, whereas the JA content of the mutant significantly decreased, reaching only 59.33% of that of the control (Figure 3e). These results indicate that BpWRKY6 can regulate the synthesis of JA and affect the insect defence response of birch.

GST, CarE, and CYP450 are important detoxifying enzymes in insects. The results of the physiological analysis revealed that the GST activity, which was, respectively, 1.64‐, 1.53‐, and 1.21‐fold greater than that of the control, significantly increased in gypsy moth larvae fed plant leaves. The GST activity of the gypsy moth larvae fed with the mutant birch showed the opposite trend, which was only 67.51% of that of the control (Figure 3f). The CarE activity was significantly reduced, with only 61.25%, 46.55%, and 52.40% of that of the control, respectively. However, compared with the control, there was no significant change in CarE activity in the gypsy moth fed the mutant birch (Figure 3g). In the OE1 and OE3 lines, the CYP450 activity significantly increased to 1.18‐ and 1.22‐fold greater than that of the control, respectively. However, there was no significant difference in CYP450 activity between larvae fed OE2 and the control larvae. The CYP450 activity decreased significantly in the gypsy moth larvae fed with the mutant birch, with only 81.05% of that in the control (Figure 3h). These results indicate that feeding BpWRKY6 transgenic birch leaves strongly affects the enzymatic system of the gypsy moth.

Transcriptome analysis of overexpressing BpWRKY6 birch

To analyse the anti‐insect defence pathway associated with BpWRKY6, the transcriptomes of the BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines and controls were sequenced and compared. The results revealed 1134 downregulated genes and 1137 upregulated genes in the BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines compared with the control (Figure 4a). TFs play important roles in plant defence responses; therefore, further analysis was conducted on the differentially expressed TFs (Xie et al., 2024). A Venn diagram of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and birch genomic TFs revealed that 30 and 22 TFs were downregulated and upregulated, respectively, in the BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines (Figure 4b). Therefore, we speculate that BpWRKY6 may play an important role in hierarchical regulation and regulate different biological processes through other regulatory factors.

Figure 4.

Transcriptome analysis of overexpression‐BpWRKY6 in birch. (a) Volcano plot of DEGs between overexpress line and control. (b) The Venn diagram between TFs and DEGs in birch. (c) GO enrichment analysis of DEGs in birch. (d) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in birch.

Owing to the positive regulatory effect of BpWRKY6 on gypsy moth resistance in birch, GO enrichment analysis was conducted on the upregulated genes. The results revealed that hormone‐related processes, such as JA and ethylene‐dependent systemic resistance, the auxin metabolic process, and hormone biosynthetic processes, were significantly enriched (Figure 4c). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the upregulated genes were significantly enriched in phenylalanine metabolism, diterpenoid biosynthesis, and benzoxazinoid biosynthesis (Figure 4d).

Dieterpenoids are important secondary metabolites in plants that play crucial roles in plant defence responses. Interestingly, the total terpene content did not significantly differ between the control and overexpressed plant leaves under normal conditions. However, after the gypsy moth was fed, the total terpenoid content of the birch‐overexpressing lines increased by 1.23‐, 1.29‐, and 1.20‐fold, which was significantly different from that of the control (Figure S3a). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that CYP82G1 is a trimethyltridecatetraene/dimethylnonatriene synthase that catalyses the synthesis of TMTT. Therefore, the TMTT content in the transgenic and control birch plants was determined via GC–MS, and the results revealed that the TMTT content in the transgenic birch lines after gypsy moth feeding was greater than that in the control and mutant plants (Figure S3b). The JA content also significantly changed after gypsy moth feeding (Figure 3e). The results revealed that the BpWRKY6 gene may be involved in gypsy moth resistance regulation through the JA and diterpenoid biosynthesis pathways.

Screening of target genes for BpWRKY6

The expression of JA and diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway‐related genes (BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, BpAOS2, and BpCYP82G1) was monitored via qRT–PCR. The results revealed that the expression levels of the BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, BpAOS2, and BpCYP82G1 genes increased in the overexpression lines (Figure 5a), suggesting that BpWRKY6 has indirect or direct regulatory effects on these genes.

Figure 5.

Analysis of target genes of BpWRKY6. (a) Expression level of target genes screened from overexpressing BpWRKY6 birch. (b) LUC activity detection of BpWRKY6 and target gene promoter co‐transgenic tobacco, and standardization was carried out uniformly through the control. (c) The distribution of W‐box in the promoter of the target gene. (d) ChIP‐qPCR analysis of binding between BpWRKY6 and target genes. (e, f) Y1H analysis (e) and EMSA experiment (f) proves the combination of BpWRKY6 and W‐box. * Represents P‐value < 0.05, ** represents P‐value < 0.01.

To further investigate whether BpWRKY6 directly targets 5 genes, promoter fragments were inserted into the pGreenII‐0800‐LUC reporter vector, and the relationships between BpWRKY6 and these genes were detected through a LUC assay. The results revealed that when BpWRKY6 was co‐transformed with the promoters of BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, and BpCYP82G1, the LUC enzyme activity significantly increased and was 6.08‐, 4.82‐, 17.70‐, and 2.33‐fold greater than that of the control, respectively. However, when BpWRKY6 was co‐transformed with the promoters of BpAOS2, LUC enzyme activity did not significantly change compared with that of the control (Figure 5b). The above evidence indicates that BpWRKY6 can directly drive the expression of BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, and BpCYP82G1.

Many reports have confirmed that WRKY TFs can specifically recognize W‐box (Dong et al., 2003). These gene promoter sequences were analysed, and all the promoters included 1–5 W‐boxes (Figure 5c). Furthermore, ChIP–qPCR was used to analyse whether BpWRKY6 binds to the promoters of these genes through the W‐box. Interestingly, the ChIP–qPCR results also revealed that BpWRKY6 can bind to the promoters of BpLOX15, BpAOC4‐p2, BpAOS1, and BpCYP82G1. However, for BpAOS2, which has five tandem W‐boxes in the promoter, the enrichment was very low (Figure 5d). To further verify the binding of BpWRKY6 to the W‐box in the promoter, the core sequence TTGAC of the W‐box within these promoter fragments was mutated to TTcgg. The specificity of BpWRKY6 binding to the W‐box was validated by Y1H and EMSA. The Y1H results revealed that BpWRKY6 co‐transformed with these promoter fragments was able to grow on SD/−Trp/−Leu and SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His+50 mM 3‐AT media. However, yeast only grew on SD/−Trp/−Leu media and could not grow on SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His+50 mM 3‐AT media after the W‐box in the promoter fragments was mutated. These results indicated that BpWRKY6 can specifically bind directly to the W‐box of these promoter fragments (Figure 5e). The EMSA results further confirmed the specific binding of BpWRKY6 to the W‐box of these promoter fragments (Figure 5f). The above evidence indicates that BpWRKY6 can directly target and regulate the BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, and BpCYP82G1 genes, thereby regulating JA and diterpenoid biosynthesis to affect gypsy moth resistance defence in birch.

BpMAPK6 enhances the activation of downstream genes by BpWRKY6

Owing to the lack of transcriptional activation ability of BpWRKY6, it may form complexes with other proteins to perform its functions. Yeast library screening revealed that BpMAPK6 interacts with BpWRKY6. The expression level of BpMAPK6 was detected via qRT–PCR, and the highest expression level was detected when the leaf area consumed by the gypsy moth larvae was less than one quarter (Figure S4). The co‐transformation of Y2H by BpMAPK6 and BpWRKY6 led to normal growth and the QDO/X/A media turning blue (Figure 6a). To validate the physical effects, the recombinant proteins GST‐BpMAPK6 and MBP‐BpWRKY6 were induced in vitro, and the interaction between BpMAK6 and BpWRKY6 was further determined through pull‐down. After the purified GST complex was incubated with the MBP antibody, specific bands were observed at 68 kDa, whereas no specific bands were observed in the absence of the MAPK6 product (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Analysis of the interaction between BpWRKY6 and BpMAPK6. (a) Y2H analysis of the interaction between BpWRKY6 and BpMAPK6. (b) Pull‐down analysis of interaction between BpWRKY6 and BpMAPK6 in vitro. (c) Phosphorylation in vitro. Phos‐tag represents phosphorylation specific antibody detection. CBB represents Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (d) BpWRKY6S253A/S288A cannot be phosphorylated by BpMAPK6 in vitro. (e) The impact of the interaction between BpMAPK6 and BpWRKY6 on their target genes, and the LUC/REN of BpMAPK6 cotransfected with BpWRKY6 and BpWRKY6 target genes were standardized using only BpWRKY6 and BpWRKY6 target genes as controls. * Represents P‐value < 0.05, ** represents P‐value < 0.01.

MAPKs can phosphorylate substrates and affect their function. Therefore, the relationship between BpWRKY6 and BpMAPK6 was explored by phosphorylation in vitro. The results revealed that when BpMAPK6 was incubated with BpWRKY6, there was a phosphorylation band at ~ 100 kDa, whereas BpWRKY6 alone had no phosphorylation band (Figure 6c). This evidence suggested that BpWRKY6 was phosphorylated as a substrate of BpMAPK6. The phosphorylation sites of the BpWRKY6 protein were identified by LC–MS/MS analysis at positions Ser253 and Ser288 (Figure S5). We conducted in vitro phosphorylation analysis by mutating its single or double sites. The results revealed that the phosphorylation bands could still be observed after the mutation of Ser253 or Ser288 to Ala, while when both sites were mutated simultaneously (BpWRKY6S253A/S288A), the phosphorylation bands disappeared (Figure 6d).

Furthermore, the LUC results revealed that the enzyme activity of BpWRKY6 and the promoters of BpLOX15, BpAOC4, BpAOS1, and BpCYP82G1 were increased when BpWRKY6 was co‐transfected with tobacco, which was 1.67‐, 1.74‐, 1.34‐, and 2.12‐fold greater than that of BpWRKY6 co‐transfected with its target genes, respectively (Figure 6e). These results indicate that BpMAPK6 interacts with BpWRKY6 and promotes the activation of its downstream target genes.

Discussion

Chemical control is currently one of the main ways to address pests in production activities, but it has a significant impact on the ecological environment and is not conducive to green and sustainable development. Effectively utilizing the plant's insect resistance defence mechanism and cultivating insect‐resistant varieties are important measures for achieving green and convenient pest control. Currently, insect‐resistant plants are obtained mainly by expressing foreign genes from different species, such as crys, CpTI, or GNA (Li et al., 2020). However, many pests have different sensitivities to these genes, and it is necessary to identify more insect resistance genes (Wang et al., 2018). The lack of resistance genes from plant sources limits the breeding range of insect‐resistant varieties. Here, we report that BpWRKY6, as a substrate of BpMAPK6, plays a positive regulatory role in the gypsy moth defence response of birch.

WRKY family TFs not only play important roles in plant life activities, but also have been reported to be involved in various abiotic and biotic stress responses (Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2024). Hao et al. (2024) reported that WRKY46‐MYC2 forms a complex in Arabidopsis that interacts with the RBOHD promoter and activates its expression, promoting the production of H2O2 while increasing the expression level of naringin synthesis genes (TT4 and CHIL), and inducing the accumulation of total flavonoids, thereby increasing plant resistance to insects. In rice, silent OsWRKY45 (as‐wrky) lines induce increased levels of H2O2 and ethylene induced by Nilaparvata lugens (BPH), reduce the feeding and oviposition preferences and survival rates of BPHs, and delay the development of BPH nymphs. Field experiments revealed that the density of the BPH population on the as‐wrky lines was lower than that on the WT plants (Huangfu et al., 2016). In this study, overexpression of the BpWRKY6 gene increased the contents of JA and terpenoid in birch, thereby altering the feeding behaviour of gypsy moth larvae. Overexpression of the BpWRKY6 gene significantly reduced the amount of birch leaves consumed by larvae, leading to delayed development of gypsy moth larvae and altered detoxification enzyme activity in the gypsy moth.

After feeding on plant leaves, insects rely on their detoxification system to decompose various secondary metabolites produced by plants. The main detoxifying enzymes in insects include acetylcholinesterase (AChE), CarE, CYP450, and GSTs (Yuan et al., 2020). Guo et al. (2010) reported that the activities of lipase, CarE, and AChE in Spodoptera exigua fed Bt‐cotton were significantly lower than those in Spodoptera fed normal plants, whereas the activities of trypsin and total superoxide dismutase were significantly greater. Yang et al. (2013) reported that the activities of AChE, CarE, and GST were significantly reduced in H. armigera, which was fed cotton leaves treated with MeJA. Qiu et al. (2024) reported that compared with Frankliniella occidentalis that fed on control plants, F. occidentalis that fed on plants treated with CaCl2 presented significantly increased activities of the detoxifying enzymes GST and CYP450. However, the activity of CarE was significantly reduced, and the pupation rate and pupal weight of F. occidentalis were significantly reduced. Similarly, the activities of the GST and CYP450 enzymes increased after the plants were fed leaves overexpressing BpWRKY6, whereas the activity of CarE significantly decreased.

Previous reports have shown that the JA pathway is closely related to plant insect defence responses (Li et al., 2022). Wu et al. (2024) reported that the resistance of the pub22 mutant tomato decreased, and the development of H. armigera fed pub22 mutant tomato leaves was significantly greater than that of larvae fed wild‐type leaves. In the mutant, the increase in JA and JA‐Ile contents was smaller than that in the wild‐type. Further research revealed that the PUB22 gene can promote the degradation of JAZ4 and is activated by MYC2, resulting in positive feedback regulation during the signal transduction process of JA. Barneto et al. (2024) reported that Nezara viridula attacks on soybeans induce the expression of LOX genes to counteract pest invasion through JA‐regulated digestive enzyme inhibitors. In this study, BpWRKY6 expression was induced by JA treatment, and the JA content of BpWRKY6‐overexpressing birch was also greater than that of the control. Furthermore, Y1H, EMSA, LUC, and ChIP–qPCR results verified that BpWRKY6 can bind to the promoters of JA synthesis genes, including BpLOX15, BpAOC4, and BpAOS1, to promote their expression. Interestingly, BpWRKY6 cannot bind to BpAOS2, which contains five tandem W‐boxes in the promoter. This may be due to different WRKY proteins having varying affinities for different W‐boxes (He et al., 2017). It is also possible that the multiple W‐boxes in tandem increase the competitive binding between genes and the specificity of protein binding to the W‐box (Ciolkowski et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013).

In plant insect defence responses, multiple substances work together, including benzoxazines, glucosinolates, alkaloids, diterpenoids and flavonoids (Heiling et al., 2021; Jing et al., 2024). Transcriptome analysis of BpWRKY6‐overexpressing birch revealed that the DEGs were related to the metabolic pathways of phenylalanine metabolism, diterpenoid biosynthesis, and benzoxazinoid biosynthesis. Benzoxazine compounds are a class of indole‐derived plant metabolites found in Poaceae plants, whose function is to defend against various pests and pathogens (Hu et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2018). However, other families, such as Scrophulariaceae, Acanthaceae, Lamiaceae, and Ranunculaceae, also contain benzoxazines (Bhattarai et al., 2022), and metabolomic analysis of Tamarix hispida detected benzoxazine under salt stress and Cd stress (Xie et al., 2023a). A significant increase in the expression levels of benzoxazine synthesis genes, including BpBX6a and BpBX6b, was observed in the BpWRKY6‐overexpressing lines (Figure S6). The benzoxazine content and related gene roles in the BpWRKY6 OE lines need to be analysed in the future.

CYP82G1 functions as a TMTT homologous terpenoid synthase in Arabidopsis (Lee et al., 2010). TMTT is the most widely present volatile terpenoid in angiosperms and is generally believed to have the potential to attract parasites and natural enemies of pests (Tholl et al., 2011). In this study, expression analysis revealed that BpCYP82G1 was upregulated in birch, and BpWRKY6 directly activated its expression by binding to the BpCYP82G1 promoter. After the gypsy moths were fed, the total terpenoid and TMTT contents of the birch‐overexpressing lines significantly increased (Figure S3). This may also be one of the reasons for the increased ability of the BPWRKY6 OE lines to resist gypsy moth.

The MAPK membrane potential, calcium ion, and ROS signalling pathways are important early signalling events in insect defence responses (Erb and Reymond, 2019). MAPKs have been widely proven to actively regulate plant defence responses, influencing the expression of different genes through protein activity and regulating plant tolerance to insects (Hu et al., 2024). In tomatoes, MPK1, MPK2, and MPK3 are involved in regulating the expression of JA biosynthesis genes (Kandoth et al., 2007). Moreover, MPK6/3 in Arabidopsis can alter resistance to Trichoplusia ni and S. exigua (Hann et al., 2024). In birch, BpMAPK6 can phosphorylate BpWRKY6. Moreover, BpMAPK6 enhances the ability of BpWRKY6 to activate downstream genes, and may play an important role in the BpWRKY6‐mediated gypsy moth defence response of birch.

The MAPK cascade is involved in a series of cellular signal transduction pathways. In Oryza sativa, the OsMKKK10‐OsMKK4‐OsMAPK6 signalling pathway positively regulates grain size and weight (Xu et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, the MAPKKK3/5‐MKK4/5‐MPK3/6 pathways confer resistance to bacterial and fungal pathogens (Bi et al., 2018). The YODA‐MKK4/MKK5‐MPK3/MPK6 cascade, which acts as a key downstream component of the ER receptor, plays a crucial role in regulating inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis (Meng et al., 2012). However, the mechanisms by which plant MAPK cascades contribute to birch resistance remain largely unexplored, and this topic will be the focus of our future research.

In conclusion, BpWRKY6 actively participates in the defence response to gypsy moths by birch. A hypothetical regulatory model involving BpWRKY6 has been proposed. First, the feeding signal of insects is transmitted through the MAPK signalling pathway, and BpMAPK6 phosphorylates BpWRKY6, promoting the activation of JA synthesis‐related genes (BpLOX15, BpAOC4, and BpAOS1) and terpenoid synthesis genes (BpCYP82G1) by BpWRKY6 and increasing the accumulation of JA and terpenoids, thereby improving the gypsy moth resistance of birch (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of BpWRKY6 regulating the gypsy moth resistance mechanism of birch. The green arrow and dashed line propose the hypothesis of the signal transduction process, while the black arrow indicates that it has been validated.

Conclusion

The outbreak of forest pests has posed challenges to the survival of trees. The efficient resistance mechanism of plants is an important way to achieve green prevention and control technology. This study revealed that BpWRKY6 is a protein with nuclear localization but no transcriptional activation activity and that its expression can be induced by gypsy moths feeding. Compared with the control birch, BpWRKY6‐overexpressing birch presented gypsy moth resistance. Analysis of its downstream regulatory mechanism revealed that BpWRKY6 activated the expression of JA synthesis‐related genes (BpLOX15, BpAOC4, and BpAOS1) and a terpenoid synthesis gene (BpCYP82G1) to promote its expression, which increased the JA and terpenoid contents in birch. Furthermore, BpWRKY6 can be phosphorylated as a substrate for BpMAPK6, increasing its ability to activate downstream genes. In conclusion, this study revealed that BpWRKY6, as a substrate for BpMAPK6, is activated by phosphorylation in birch and positively regulates JA and terpenoid synthesis, thus increasing the insect resistance of birch. These results lay a theoretical foundation for the further breeding of insect‐resistant varieties.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Author contributions

Chuanwang Cao conceived of and directed the research. Qingjun Xie and Wenfang Dong performed the overall data analysis. Qingjun Xie, Wenfang Dong, Mengyuan Wang, and Jiaojiao Wang constructed the overexpression vector and performed the experiments. Jiaojiao Wang, Lili Sun, and Zhongyuan Liu provided the reagents and performed the assays. Qingjun Xie, Chuanwang Cao, and Caiqiu Gao wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Analysis of expression levels of WRKY IIa subgroup members in birch under feeding by gypsy moth larvae. The data were normalized by log2 to display the differences among various groups.

Figure S2 The acquisition of transgenic birch with BpWRKY6 gene. (a) Schematic diagram of transgenic process for BpWRKY6 in birch. (b) PCR detection of resistant lines and controls, 1: Marker DL2000, 2: water, 3: WT, 4–14: resistant plants. (c) Analysis of expression levels of BpWRKY6 in transgenic lines. (d) Editing status of Bpwrky6 mutant. (e) Phenotypic analysis of overexpressed of BpWRK6 and mutant birch.

Figure S3 The terpene content of control and transgenic birch leaves under normal and feeding conditions. (a) The total terpene content of control and transgenic birch leaves under normal and feeding. (b) TMTT content determination of control and transgenic birch leaves after feeding by GC–MS.

Figure S4 The expression levels of BpMAPK6 in birch under feeding by gypsy moth larvae.

Figure S5 Sites analysis of BpWRKY6 phosphorylation by LC–MS/MS.

Figure S6 The expression levels of benzoxazine synthesis gene in overexpressing BpWRKY6 lines.

Table S1 Primers used for vector construction, qRT–PCR, and ChIP–PCR.

Table S2 List of DEGs identified from the RNA‐Seq analysis.

Table S3 List of GO enrichment of DEGs in overexpression of BpWRKY6 birch.

Table S4 List of KEGG enrichment of DEGs in overexpression of BpWRKY6 birch.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32071772), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572022AW06, 2572022DQ04).

References

- Abeysinghe, J.K. , Lam, M. and Ng, D.W.K. (2019) Differential regulation and interaction of homoeologous WRKY18 and WRKY40 in Arabidopsis allotetraploids and biotic stress responses. Plant J. 97, 352–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura, G. , Huber, D.P.W. and Bohlmann, J. (2004) Forest tent caterpillars (Malacosoma disstria) induce local and systemic diurnal emissions of terpenoid volatiles in hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa × deltoides): cDNA cloning, functional characterization, and patterns of gene expression of (−)‐germacrene D synthase, PtdTPS1. Plant J. 37, 603–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, D. , Bateman, N. and Kariyat, R.R. (2024) Rice physical defenses and their role against insect herbivores. Planta 259, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneto, J.A. , Sardoy, P.M. , Pagano, E.A. and Zavala, J.A. (2024) Lipoxygenases regulate digestive enzyme inhibitor activities in developing seeds of field‐grown soybean against the southern green stink bug (Nezara viridula). Funct. Plant Biol. 51, FP22192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batool, R. , Xuelian, G. , Hui, D. , Xiuzhen, L. , Umer, M.J. , Rwomushana, I. , Ali, A. et al. (2024) Endophytic fungi‐mediated defense signaling in maize: unraveling the role of in regulating immunity against Spodoptera frugiperda . Physiol. Plant. 176, e14243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, B. , Steffensen, S.K. , Staerk, D. , Laursen, B.B. and Fomsgaard, I.S. (2022) Data‐dependent acquisition‐mass spectrometry guided isolation of new benzoxazinoids from the roots of Acanthus mollis L. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 474, 116815. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G. , Zhou, Z. , Wang, W. , Li, L. , Rao, S. , Wu, Y. , Zhang, X. et al. (2018) Receptor‐like cytoplasmic kinases directly link diverse pattern recognition receptors to the activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascades in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30, 1543–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukouvala, M.C. , Kavallieratos, N.G. , Skourti, A. , Pons, X. , Alonso, C.L. , Eizaguirre, M. , Fernandez, E.B. et al. (2022) Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae): current status of biology, ecology, and management in Europe with notes from North America. Insects 13, 854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y. , Liu, L. , Ma, K. , Wang, W. , Lv, H. , Gao, M. , Wang, X. et al. (2022) The jasmonate‐induced bHLH gene SlJIG functions in terpene biosynthesis and resistance to insects and fungus. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 64, 1102–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , Zhou, Y. , Chen, Y. and Gu, J. (2018) fastp: an ultra‐fast all‐in‐one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , Wang, Y. , Yu, L. , Zheng, T. , Wang, S. , Yue, Z. , Jiang, J. et al. (2021) Genome sequence and evolution of Betula platyphylla . Hortic. Res. 8, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. , Liu, H. , Deng, Y. , Xiao, J. , Li, X. and Wang, S. (2015) The WRKY45‐2 WRKY13 WRKY42 transcriptional regulatory cascade is required for rice resistance to fungal pathogen. Plant Physiol. 167, 1087–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciolkowski, I. , Wanke, D. , Birkenbihl, R.P. and Somssich, I.E. (2008) Studies on DNA‐binding selectivity of WRKY transcription factors lend structural clues into WRKY‐domain function. Plant Mol.Biol. 68, 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. , Yan, Q. , Gan, S. , Xue, D. , Wang, H. , Xing, H. , Zhao, J. et al. (2019) GmWRKY40, a member of the WRKY transcription factor genes identified from Glycine max L., enhanced the resistance to Phytophthora sojae. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J. , Chen, C. and Chen, Z. (2003) Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W. , Xie, Q. , Liu, Z. , Han, Y. , Wang, X. , Xu, R. and Gao, C. (2023) Genome‐wide identification and expression profiling of the bZIP gene family in Betula platyphylla and the functional characterization of BpChr04G00610 under low‐temperature stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 198, 107676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, M. , Zhao, J. , Tzeng, D.T.W. , Liu, Y. , Deng, L. , Yang, T. , Zhai, Q. et al. (2017) MYC2 orchestrates a hierarchical transcriptional cascade that regulates jasmonate‐mediated plant immunity in Tomato. Plant Cell 29, 1883–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erazo‐Garcia, M.P. , Sotelo‐Proaño, A.R. , Ramirez‐Villacis, D.X. , Garcés‐Carrera, S. and Leon‐Reyes, A. (2021) Methyl jasmonate‐induced resistance to Delia platura (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) in Lupinus mutabilis . Pest Manag. Sci. 77, 5382–5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb, M. and Reymond, P. (2019) Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 527–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajvan, M.A. and Wood, J.M. (1996) Stand structure and development after gypsy moth defoliation in the Appalachian Plateau. For. Ecol. Manage. 89, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y. , Jiang, L. , Wang, Y. , Liu, G. , Wu, J. , Luo, H. , Chen, S. et al. (2024) CmMYC2–CmMYBML1 module orchestrates the resistance to herbivory by synchronously regulating the trichome development and constitutive terpene biosynthesis in Chrysanthemum. New Phytol. 244, 914–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. , Wu, G. and Wan, H. (2010) Activities of digestive and detoxification enzymes in multiple generations of beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Hübner), in response to transgenic Bt cotton. J. Pestic. Sci. 83, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. , Qi, J. , He, K. , Wu, J. , Bai, S. , Zhang, T. , Zhao, J. et al. (2019) The Asian corn borer Ostrinia furnacalis feeding increases the direct and indirect defence of mid‐whorl stage commercial maize in the field. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 88–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W. , Chen, W. , Guo, N. , Zang, J. , Liu, L. , Zhang, Z. and Dai, H. (2022) MdWRKY61 positively regulates resistance to Colletotrichum siamense in apple (Malus domestica). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 117, 101776. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, C.T. , Ramage, S.F. , Negi, H. , Bequette, C.J. , Vasquez, P.A. and Stratmann, J.W. (2024) Dephosphorylation of the MAP kinases MPK6 and MPK3 fine‐tunes responses to wounding and herbivory in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 339, 111962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X. , Wang, S. , Fu, Y. , Liu, Y. , Shen, H. , Jiang, L. , McLamore, E.S. et al. (2024) The WRKY46–MYC2 module plays a critical role in E‐2‐hexenal‐induced anti‐herbivore responses by promoting flavonoid accumulation. Plant Commun. 5, 100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, C. , Teixeira da Silva, J.A. , Tan, J. , Zhang, J. , Pan, X. , Li, M. , Luo, J. et al. (2017) A genome‐wide identification of the WRKY family genes and a survey of potential WRKY target genes in dendrobium officinale. Sci. Rep. 7, 9200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiling, S. , Llorca, L.C. , Li, J. , Gase, K. , Schmidt, A. , Schäfer, M. , Schneider, B. et al. (2021) Specific decorations of 17‐hydroxygeranyllinalool diterpene glycosides solve the autotoxicity problem of chemical defense in Nicotiana attenuata . Plant Cell 33, 1748–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettenhausen, C. , Schuman, M.C. and Wu, J. (2015) MAPK signaling: A key element in plant defense response to insects. Insect Sci. 22, 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , Wu, Y. , Wu, D. , Rao, W. , Guo, J. , Ma, Y. , Wang, Z. et al. (2017) The coiled‐coil and nucleotide binding domains of BROWN PLANTHOPPER RESISTANCE14 function in signaling and resistance against planthopper in rice. Plant Cell 29, 3157–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , Wu, Z. , Robert, C.A.M. , Ouyang, X. , Züst, T. , Mestrot, A. , Xu, J. et al. (2021) Soil chemistry determines whether defensive plant secondary metabolites promote or suppress herbivore growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2109602118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C. , Li, T. , Liu, X. , Hao, F. and Yang, Q. (2024) Molecular interaction network of plant‐herbivorous insects. Adv. Agrochem. 3, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu, J. , Li, J. , Li, R. , Ye, M. , Kuai, P. , Zhang, T. and Lou, Y. (2016) The Transcription factor OsWRKY45 negatively modulates the resistance of rice to the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. , Niu, Y. , Zhao, H. , Wang, Z. , Gao, C. , Wang, C. , Chen, S. et al. (2022) Hierarchical transcription factor and regulatory network for drought response in Betula platyphylla . Hortic. Res. 9, uhac040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. , Ma, S. , Ye, N. , Jiang, M. , Cao, J. and Zhang, J. (2017) WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59, 86–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing, T. , Du, W. , Qian, X. , Wang, K. , Luo, L. , Zhang, X. , Deng, Y. et al. (2024) UGT89AC1‐mediated quercetin glucosylation is induced upon herbivore damage and enhances Camellia sinensis resistance to insect feeding. Plant Cell Environ. 47, 682–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, Y. , Shinya, T. , Maeda, S. , Mujiono, K. , Hojo, Y. , Tomita, K. , Okada, K. et al. (2023) BSR1, a rice receptor‐like cytoplasmic kinase, positively regulates defense responses to herbivory. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 10395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth, P.K. , Ranf, S. , Pancholi, S.S. , Jayanty, S. , Walla, M.D. , Miller, W. , Howe, G.A. et al. (2007) Tomato MAPKs LeMPK1, LeMPK2, and LeMPK3 function in the systemin‐mediated defense response against herbivorous insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 12205–12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, A. (2017) Plant defences against herbivore attack. In John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Life Sciences pp. 1–11. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. , Mizoi, J. , Yoshida, T. , Fujita, Y. , Nakajima, J. , Ohori, T. , Todaka, D. et al. (2011) An ABRE promoter sequence is involved in osmotic stress‐responsive expression of the DREB2A gene, which encodes a transcription factor regulating drought‐inducible genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 2136–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Badieyan, S. , Bevan, D.R. , Herde, M. , Gatz, C. and Tholl, D. (2010) Herbivore‐induced and floral homoterpene volatiles are biosynthesized by a single P450 enzyme (CYP82G1) in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 21205–21210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. , Zhang, J. , Li, J. , Zhou, G. , Wang, Q. , Bian, W. , Erb, M. et al. (2015) Prioritizing plant defence over growth through WRKY regulation facilitates infestation by non‐target herbivores. Elife 4, e04805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Hallerman, E.M. , Wu, K. and Peng, Y. (2020) Insect‐resistant genetically engineered crops in China: development, application, and prospects for use. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65, 273–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. , Xu, M. , Cai, X. , Han, Z. , Si, J. and Chen, D. (2022) Jasmonate signaling pathway modulates plant defense, growth, and their trade‐offs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. , Wang, P. , Wang, Z. , Wang, C. and Wang, Y. (2024) Birch WRKY transcription factor, BpWRKY32, confers salt tolerance by mediating stomatal closing, proline accumulation, and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 210, 108599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, M.I. , Huber, W. and Anders, S. (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA‐seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łukowski, A. , Jagiełło, R. , Robakowski, P. , Adamczyk, D. and Karolewski, P. (2022) Adaptation of a simple method to determine the total terpenoid content in needles of coniferous trees. Plant Sci. 314, 111090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki, S. , Toki, R. , Watanabe, Y. and Masaka, K. (2021) Defoliation by Gypsy Moth (Lepidoptera, Erebidae) induces differential delayed induction of trichomes in two birch species. Environ. Entomol. 50, 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. , Wang, H. , He, Y. , Liu, Y. , Walker, J.C. , Torii, K.U. and Zhang, S. (2012) A MAPK Cascade downstream of erecta receptor‐like protein kinase regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture by promoting localized cell proliferation. Plant Cell 24, 4948–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte, I. (2023) Jasmonates and salicylic acid: Evolution of defense hormones in land plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 76, 102470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro, R. , Duggal, G. , Love, M.I. , Irizarry, R.A. and Kingsford, C. (2017) Salmon provides fast and bias‐aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernek, M. , Pilas, I. , Vrbek, B. , Benko, M. , Hrasovec, B. and Milkovic, J. (2008) Forecasting the impact of the Gypsy moth on lowland hardwood forests by analyzing the cyclical pattern of population and climate data series. For. Ecol. Manage. 255, 1740–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y. , Huang, Q. , Zeng, G. , Yue, B. , Zhang, Y. and Zhi, R. (2024) Enzymatic activity and development of Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in response to exogenous calcium treatments of kidney bean plants. J. Econ. Entomol. 117, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek, S. and Somssich, I.E. (2002) Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 16, 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman, M.C. , Meldau, S. , Gaquerel, E. , Diezel, C. , McGale, E. , Greenfield, S. and Baldwin, I.T. (2018) The active jasmonate JA‐Ile regulates a specific subset of plant jasmonate‐mediated resistance to herbivores in nature. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, A.H. , Eschen, L. , Pecher, P. , Hoehenwarter, W. , Sinha, A.K. , Scheel, D. and Lee, J. (2016) Regulation of WRKY46 transcription factor function by mitogen‐activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis thaliana . Front. Plant Sci. 7, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. , Wang, H. , Li, M. , Mi, L. , Gao, Y. , Qiang, S. , Zhang, Y. et al. (2024) Alternaria TeA toxin activates a chloroplast retrograde signaling pathway to facilitate JA‐dependent pathogenicity. Plant Commun. 5, 100775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Griess, V.C. and Keena, M.A. (2020) Assessing the potential distribution of Asian Gypsy Moth in Canada: a comparison of two methodological approaches. Sci. Rep. 10, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack, G.M. , Snyder, S.I. , Toth, J.A. , Quade, M.A. , Crawford, J.L. , McKay, J.K. , Jackowetz, J.N. et al. (2023) Cannabinoids function in defense against chewing herbivores in Cannabis sativa L. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. , Gao, Y. , Zhang, Q. , Lv, Y. and Cao, C. (2022) Resistance to Lymantria dispar larvae in transgenic poplar plants expressing double‐stranded RNA. Ann. Appl. Biol. 181, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. , Sun, Y. , Cao, X. , Zhai, X. , Callaway, R.M. , Wan, J. , Flory, S.L. et al. (2023) Trade‐offs in non‐native plant herbivore defences enhance performance. Ecol. Lett. 26, 1584–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M. , Saze, H. , Probst, A.V. , Lichota, J. , Habu, Y. and Paszkowski, J. (2003) Erasure of CpG methylation in Arabidopsis alters patterns of histone H3 methylation in heterochromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 8823–8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholl, D. , Sohrabi, R. , Huh, H. and Lee, S. (2011) The biochemistry of homoterpenes‐common constituents of floral and herbivore‐induced plant volatile bouquets. Phytochemistry 72, 1635–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Wang, M. , Zhang, X. , Hao, B. , Kaushik, S.K. and Pan, Y. (2011) WRKY gene family evolution in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica 139, 973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. , Dong, Y. , Liu, X. , Yao, G. , Yu, X. and Yang, M. (2018) The current status and development of insect‐resistant genetically engineered poplar in China. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Salasini, B.C. , Khan, M. , Devi, B. , Bush, M. , Subramaniam, R. and Hepworth, S.R. (2019a) Clade I TGACG‐motif binding basic leucine zipper transcription factors mediate BLADE‐ON‐PETIOLE‐dependent regulation of development. Plant Physiol. 180, 937–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Nur, F.A. , Ma, J. , Wang, J. and Cao, C. (2019b) Effects of poplar secondary metabolites on performance and detoxification enzyme activity of Lymantria dispar . Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 225, 108587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. , Liang, S. , Wang, G. , Wang, Q. , Xu, Z. , Li, B. , Fu, C. et al. (2024) Comprehensive analysis of MAPK gene family in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and functional characterization of GhMPK31 in regulating defense response to insect infestation. Plant Cell Rep. 43, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani, S.H. , Anand, S. , Singh, B. , Bohra, A. and Joshi, R. (2021) WRKY transcription factors and plant defense responses: latest discoveries and future prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 40, 1071–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. , Hu, E. , Xu, S. , Chen, M. , Guo, P. , Dai, Z. , Feng, T. et al. (2021) clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovations 2, 100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. , Hu, C. , Zhu, C. , Fan, Y. , Zhou, J. , Xia, X. , Shi, K. et al. (2024) The MYC2–PUB22–JAZ4 module plays a crucial role in jasmonate signaling in tomato. Mol. Plant 17, 598–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q. , Liu, B. , Dong, W. , Li, J. , Wang, D. , Liu, Z. and Gao, C. (2023a) Comparative transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses provide insights into the responses to NaCl and Cd stress in Tamarix hispida . Sci. Total Environ. 884, 163889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q. , Wang, Y. , Wang, D. , Li, J. , Liu, B. , Liu, Z. , Wang, P. et al. (2023b) The multilayered hierarchical gene regulatory network reveals interaction of transcription factors in response to cadmium in Tamarix hispida roots. Tree Physiol. 43, 630–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q. , Wang, D. , Ding, Y. , Gao, W. , Li, J. , Cao, C. , Sun, L. et al. (2024) The ethylene response factor gene, ThDRE1A, is involved in abscisic acid‐ and ethylene‐mediated cadmium accumulation in Tamarix hispida . Sci. Total Environ. 937, 173422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. and Zhang, S. (2015) Mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascades in signaling plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R. , Duan, P. , Yu, H. , Zhou, Z. , Zhang, B. , Wang, R. , Li, J. et al. (2018) Control of grain size and weight by the OsMKKK10‐OsMKK4‐OsMAPK6 signaling pathway in rice. Mol. Plant 11, 860–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. , Wu, H. , Xie, J. and Rantala, M.J. (2013) Depressed performance and detoxification enzyme activities of Helicoverpa armigera fed with conventional cotton foliage subjected to methyl jasmonate exposure. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 147, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J. , Xiao, Y. , Han, C. , Shan, W. , Fan, Q. , Xu, G. , Kuang, F. et al. (2016) Banana fruit VQ motif‐containing protein5 represses cold‐responsive transcription factor MaWRKY26 involved in the regulation of JA biosynthetic genes. Sci. Rep. 6, 23632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, M. , Song, N. , Chen, S. and Wu, J. (2021) NaKTI2, a Kunitz trypsin inhibitor transcriptionally regulated by NaWRKY3 and NaWRKY6, is required for herbivore resistance in Nicotiana attenuata . Plant Cell Rep. 40, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. , Pan, Y. , Dong, Y. , Lu, B. , Zhang, C. , Yang, M. and Zuo, L. (2021) Cloning and overexpression of PeWRKY31 from Populus × euramericana enhances salt and biological tolerance in transgenic Nicotiana. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. , Li, L. , Zhao, J. and Chen, M. (2020) Effect of tannic acid on nutrition and activities of detoxification enzymes and acetylcholinesterase of the Fall Webworm (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae). J. Insect Sci. 20, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F. , Nan, N.A.N. and YaGuang, Z. (2007) Extraction of total RNA from mature leaves rich in polysaccharides and secondary metabolites of Betula platyphylla Suk. Plant Physiol. Commun. 43, 913–916. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Feng, Y. , Cheng, J. , Tang, H. , Xu, F. , Zhu, F. , Zhao, Y. et al. (2013) The roles of two transcription factors, ABI4 and CBFA, in ABA and plastid signalling and stress responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 83, 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. , Zhang, W. , Liu, W. , Li, K. , Tan, Q. , Zhou, S. , Wang, G. et al. (2020) A WRKY transcription factor, TaWRKY42‐B, facilitates initiation of leaf senescence by promoting jasmonic acid biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. , Huang, S. , Zhang, Q. , Wei, Y. , Tao, Z. , Wang, C. , Zhao, Y. et al. (2024) The plant terpenes DMNT and TMTT function as signaling compounds that attract Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis) to maize plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66, 2528–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. , Richter, A. and Jander, G. (2018) Beyond defense: Multiple functions of benzoxazinoids in maize metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol. 59, 1528–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Analysis of expression levels of WRKY IIa subgroup members in birch under feeding by gypsy moth larvae. The data were normalized by log2 to display the differences among various groups.

Figure S2 The acquisition of transgenic birch with BpWRKY6 gene. (a) Schematic diagram of transgenic process for BpWRKY6 in birch. (b) PCR detection of resistant lines and controls, 1: Marker DL2000, 2: water, 3: WT, 4–14: resistant plants. (c) Analysis of expression levels of BpWRKY6 in transgenic lines. (d) Editing status of Bpwrky6 mutant. (e) Phenotypic analysis of overexpressed of BpWRK6 and mutant birch.

Figure S3 The terpene content of control and transgenic birch leaves under normal and feeding conditions. (a) The total terpene content of control and transgenic birch leaves under normal and feeding. (b) TMTT content determination of control and transgenic birch leaves after feeding by GC–MS.

Figure S4 The expression levels of BpMAPK6 in birch under feeding by gypsy moth larvae.

Figure S5 Sites analysis of BpWRKY6 phosphorylation by LC–MS/MS.

Figure S6 The expression levels of benzoxazine synthesis gene in overexpressing BpWRKY6 lines.

Table S1 Primers used for vector construction, qRT–PCR, and ChIP–PCR.

Table S2 List of DEGs identified from the RNA‐Seq analysis.

Table S3 List of GO enrichment of DEGs in overexpression of BpWRKY6 birch.

Table S4 List of KEGG enrichment of DEGs in overexpression of BpWRKY6 birch.