Abstract

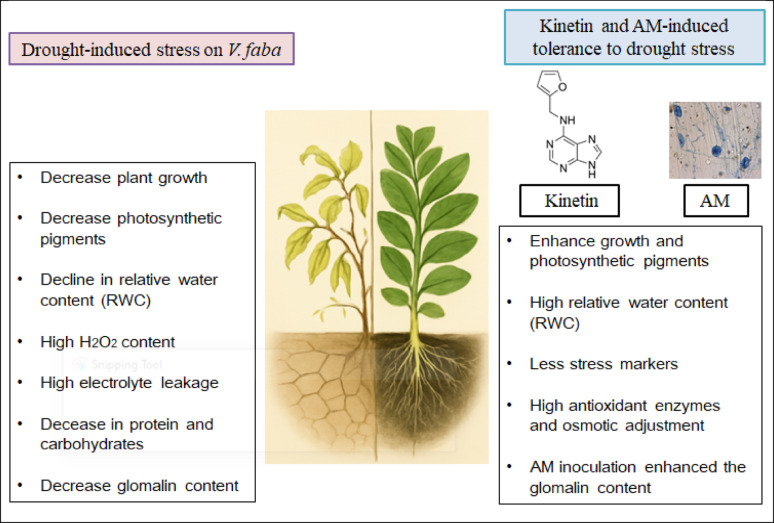

In light of the detrimental consequences of climate change and global warming, drought (water deficit) has emerged as a major abiotic stressor that adversely affects plant development, productivity, and sustainable agriculture globally. Vicia faba L. (faba bean), a highly nutritious leguminous crop, is especially vulnerable to water scarcity. As a possible solution, this study highlighted the recent advances in plant stress physiology regarding the role of kinetin (20 mg/L) and arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi in enhancing V. faba resilience to drought (30% water holding capacity) with emphasis on their growth, physiological and biochemical mechanisms. Under controlled conditions, drought markedly decreased plant growth, photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a + b and total pigments), and relative water content (RWC), while increasing stress markers (hydrogen peroxide and electrolyte leakage). Nevertheless, these negative effects were considerably lessened by AM fungi and kinetin application. Their application led to the improvement of V. faba growth parameters, maintaining cellular hydration (high RWC), higher activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase, ascorbate peroxidase, and polyphenol oxidase) and organic adjustments which include total soluble protein, proline and total soluble carbohydrate. The most surpassing effect is that AM fungal inoculation enhanced the soil-rich glomalin content, both easily and total extractable. Regarding the effect of drought stress on mycorrhizal colonization; microscopic observation showed a noticeable reduction in the formation of arbuscules and vesicles under drought. Although reduced colonization, AM fungi can nevertheless benefit host plants. These findings highlight the potential of integrating AM fungal inoculation or kinetin treatment as an eco-friendly strategy to enhance drought resilience in V. faba cultivation.

Keywords: Kinetin, Endophytes, Drought, Legume, Peroxidation, Osmolytes, Glomalin

Introduction

In natural environments, plants are constantly encountering fluctuations in environmental cues [1]. It is anticipated that future global climate change will accelerate due to the ongoing increase in air temperature and atmospheric CO2 levels, which eventually change the distribution and patterns of rainfall [2, 3]. The primary cause of drought or water deficit stress is typically inadequate rainfall-induced water intake, elevated temperatures, intense light, and dry winds can cause evaporation, which further exacerbates an already-existing drought stress event [4, 5]. On a worldwide scale, drought significantly limits agricultural development especially in arid and semi-arid regions as it has a multifaceted effect on plants, affecting plant phenotype, physiology, and biochemistry [6]. It adversely affects plant growth and development by reducing water availability, impairing nutrient uptake, and disturbing metabolic and physiological processes and leads to the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately reducing yield and plant survival [7, 8]. Egypt, as an arid country, is one of several nations with water shortage issues, which have recently gotten worse as a result of limited supplies, the country’s rapid population growth and fixed water allocation from the Nile River [9, 10].

Leguminous crops like Vicia faba L. are crucial for sustainable agriculture due to their high nutritional value and nitrogen-fixing facilities, although their sensitivity to water deficit during growth stages renders them vulnerable to yield losses under drought circumstances [8, 11]. So, their sensitivity to drought necessitates effective mitigation strategies. Traditional breeding methods have had limited success in developing drought-resistant varieties. Developing alternative and effective strategies to mitigate the detrimental effects of drought in V. faba is critical to ensuring food security and sustainable agriculture, especially in drought-prone regions. Among these effective strategies, the application of phytohormones such as kinetin and the utilization of endophytic fungi have emerged as promising approaches to enhance drought tolerance [12, 13].

Cytokinins, particularly kinetin, play a significant role in regulating various physiological and biochemical processes in plants, including cell division, chloroplast development, senescence delay, and stress tolerance [14, 15]. A study by Abeed et al. [16] stated that the application of kinetin triggered a clear shift from downregulation to upregulation of all drought tolerance traits in wheat cultivars by redirecting photoassimilates toward vegetative sinks which led to enhanced growth, increased accumulation of osmoregulatory compounds, improved tissue vigor and morphological adjustments. Additionally, under drought conditions, kinetin modulates the expression of stress-responsive genes and maintains cellular homeostasis, contributing to improved water status, photosynthetic efficiency, and overall plant resilience [17]. It sustains stomatal conductance, enhances osmotic adjustment, and boosts antioxidant enzyme activity, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POX), which play vital roles in detoxifying ROS generated during stress. The exogenous application of kinetin improved plant resistance to drought stress by enhancing growth and various physiological processes which are negatively affected by drought stress [18, 19].

Among other effective techniques, symbiotic connection with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi, a common type of soil microbe, can form adaptive mechanisms with their host plants and form symbiotic associations with the roots of more than 80% of plant species [20–23]. By expanding root surface area, promoting nutrient and water uptake, and modifying hormonal and antioxidant pathways, mycorrhiza enhances plant performance in water-limited environments [24–27].

A study by Singh and Singh [26] reported that AM fungi improved the nutritional status and leaf relative water content (RWC) in tomato plants, facilitating more efficient mineral translocation and mitigating the adverse effects of drought on plant growth. In legumes, mycorrhizal symbiosis has been linked to improved nitrogen fixation, enhanced root development, and greater drought tolerance [28]. Soliman et al. [13] and Kakouridis et al. [29] discovered that AM fungi can help plants respond less negatively to water stress by acting as extensions of the root system along the soil-plant-air water flow continuum. In Populus cathayana, Han et al. [30] revealed AM-induced genes that mostly enhanced the antioxidant enzyme system and osmotic control, hence contributing to drought stress resistance. According to Liu et al. [31], under stress, AM fungi changed a number of pathways linked to the metabolism of organic acids and amino acids in peanut roots while maintaining the architecture of mitochondria and chloroplast thylakoids.

Despite the documented benefits of kinetin and AM fungi in different crops, detailed studies evaluating its physiological and biochemical impacts on V. faba plants under drought stress remain limited. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the individual role of kinetin and mycorrhizal fungi in improving drought stress tolerance in V. faba plants. By assessing morphological, physiological, and biochemical responses, this research donates to a better understanding of how biostimulants can enhance crop resilience in water-lacking environments.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Seeds of Vicia faba L. (broad bean: Sakha 3) were supplied by Crop Institute, Agriculture Research Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Giza, Egypt. The seeds were surface-sterilized using 30% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, and sown in plastic black bags (17 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height) filled with a sterilized 4 kg soil: clay to sand mixture (2:1). This soil was previously autoclaved at 121 °C for 1 h on three consecutive days to eliminate native microorganisms, including mycorrhizal propagules [32]. This work was carried out in the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of science, Zagazig University during the winter season of 2024/2025. Plants were grown under conditions with a 14/10 h light/dark photoperiod, temperature of 24 ± 2 °C, and relative humidity of 60–70%.

For mycorrhizal inoculation, the AM fungal inoculum used in this study was Rhizophagus irregularis, Gigaspora margarita, Funneliformis mosseae and F. constrictum, Each pot received 50 g of inoculum containing spores, hyphal fragments, and infected root pieces at sowing time. The inoculum was applied directly below the seeds to ensure effective colonization. For control (non-mycorrhizal) treatments, a filtrate (25 μm mesh) of the inoculum was added to provide the same microbial wash (minus AM fungal propagules) to normalize microbial exposure [24].

Regular irrigation was maintained until drought stress was imposed. After 1 week of cultivation, uniform seedlings were selected 5 plants/pot and pots were laid out in a completely randomized design with the following factorial six treatments with five replicates per treatment (5 × 6) giving total of 30 pots:

Control (C): Well-watered: Plants were irrigated with 90% water holding capacity (WHC).

Drought stress (DS: 30% WHC): Plants were irrigated with 30% WHC.

Kinetin (KN): Plants were foliar-sprayed with kinetin.

AM: Plants were inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculum.

Drought + Kinetin (DS + KN): Plants were irrigated with 30% WHC + foliar-sprayed with kinetin.

Drought + AM (DS + AM): Plants were irrigated with 30% WHC + Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculum.

Implementation of drought and kinetin treatments: Drought stress was initiated three weeks after germination by adjusting the soil water capacity at (30% WHC) using gravimetric methods. The stress period continued for 3 weeks. For kinetin application, kinetin (6-furfurylaminopurine) was supplied from SIGMA and applied as a foliar spray at a concentration of 20 mg/L, prepared in distilled water and applied thrice: at the onset of drought and two times later. Each plant was sprayed with 25 mL of kinetin solution. After the drought period, sampling was done following a thorough cleaning of all plants from each treatment with distilled water and a gentle paper towel to evaluate the growth traits, and physiological and biochemical determinations.

Measured parameters

Mycorrhizal colonization

Following the method of Phillips and Hayman [32], root samples of V. faba were cleared in 10% KOH and stained with 0.05% trypan blue to notice AM fungal structures under a microscope, besides hyphal (HC), vesicular (VC) and arbuscular colonization (ARC) (%) were estimated.

Growth and biomass

Growth related parameters, such as plant height (cm), leaf number, and total fresh/dry biomass (g) were recorded at sampling. Dry biomass was obtained after oven-drying samples at 70 °C for 72 h.

Physiological measurements

Relative water content (RWC) was determined following the method of Barrs and Weatherley [33] and calculated based on the following formulae: RWC (%) = [(Fresh weight – Dry weight)/(Turgid weight – Dry weight)]*100. The leaf RWC was estimated by recording the fresh weight (g) of leaf samples, thereafter immediately dipped in Petri dishes containing distilled water for 4 h to record turgid weight (g), followed by drying in a hot air oven at 70 °C till constant dry weight (g) reached.

Chlorophyll content was measured spectrophotometrically in 80% acetone extracts by using double beam spectrophotometer (RIGOL, Model Ultra-3660). 100 mg of leaf sample was collected in a bottle containing 20 mL acetone and the absorbance of the supernatants was read at 645, 452.5 and 663 nm using 80% acetone as blank [34].

Electrolyte leakage (EL) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content

The Lutts et al. [35] approach was used to measure EL or the drought injury index. In short, 20 leaf discs from unstressed and drought-stressed plants were cleaned using distilled water. After that, the disc samples were left at room temperature in 20 mL of distilled water. After two hours, a conductivity meter was used to measure the solutions’ initial conductivity (ELi). The samples were heated to 120 °C for 20 min in a water bath and cooled to room temperature, and the final conductivity (ELf) of the resultant solutions was then measured. This formula was used to determine the EL: EL (%) = (ELi/ELf) × 100.

A spectrophotometer was used to measure the H2O2 level by Velikova et al. [36]’s procedure. 500 mg of fresh leaf tissues were homogenized using trichloroacetic acid. For 15 min, the homogenate was centrifuged at 8000 g. Then, 0.5 mL of the supernatant was combined with 2 mL of potassium iodide (1 M) and 0.5 mL of 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Each sample’s H2O2 content was calculated as mg/g Fw by comparing its absorbance at 390 nm to a standard calibration curve.

Determination of organic osmolytes (proline, protein and carbohydrates)

The Bates et al. [37] method and a standard graph with a range of proline concentrations were used to compute the proline content. After crushing 500 mg of fresh leaf samples in a 3% sulfosalicylic acid solution, the samples were allowed to settle for five minutes. The supernatant was mixed with glacial acetic acid solution and acid ninhydrin (1:1:1) after centrifugation at 10,000 g. The mixture was heated to 100 °C for 60 min and then chilled in an ice bath. To test the absorbance of the resultant solution at 520 nm, toluene was employed as a blank to collect the chromophore.

The phenol-sulfuric acid technique [38] was used to quantify the total soluble carbohydrates that were extracted from dry leaf tissue using HCl. In accordance with Lowry et al. [39], the total soluble protein was extracted in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and quantified by combining 1 mL of extract with 5 mL of sol C (50 mL sol A {2% Na2CO3 in 0.4% NaOH} +1mL sol B {0.5% CuSO4 in 1% sodium tartrate}), shaking thoroughly, and then letting it sit at room temperature for 10 min. After that, 0.5 mL of Folin reagent was added, thoroughly shaken, and left at room temperature for 30 min before the absorbance at 750 nm was measured. The protein content was measured in mg of Bovine Serum Albumin equivalent per gram of fresh weight.

Glomalin content

The methods for measuring glomalin content in soil, including easily extractable (EEG) and total glomalin (TG), comprise specific extraction and quantification techniques [40]. To measure EEG content, soil samples are first exposed to an extraction process using a mild buffer solution, typically 0.01 M citrate (pH 7.0). The soil is heated at approximately 60 °C for 30 min, after which the mixture is centrifuged to separate the glomalin from the soil particles and the extracted solution is then scrutinized for protein content [39]. Concerning TG content, on the other hand, includes both EEG and glomalin more tightly bound to soil particles. This is extracted through a more intense procedure, where the soil is heated under high pressure with 50 mM sodium hydroxide at 121 °C (autoclaving). The slurry is then centrifuged, and the TG is measured similarly to EEG.

Antioxidant enzymatic activity assays

Fresh leaf samples weighing 1 g from each treatment were homogenized in 10 mL of ice-cold extraction solution that contained 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7). At 4 °C, the homogenate was centrifuged for 20 min at 8000 g. The enzymatic tests were performed using the obtained supernatant. The reduction method of nitro blue tetrazolium was used to evaluate SOD activity [41]. In an aluminium foil-lined box with two fluorescent lamps at 25 °C, test tubes holding reaction solution comprising 3 mL of assay buffer, 60 µL of crude enzyme, and 30 µL of riboflavin were lit for seven minutes. Following the reaction, a spectrophotometer was used to measure the absorbance of the reaction solution and blank solution at 560 nm. The following formula was used to determine SOD activity:

|

Sample absorbance is denoted by A, and blank absorbance by B.

Briefly the activities of catalase (CAT: EC 1.11.1.6), peroxidase (POX: EC 1.11.1.7): polyphenol oxidase (PPO: EC 1.14.18.1) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX: EC 1.1.11.1) were measured in the supernatant and expressed as units/g fresh weight following the protocol of Aebi [42], Maehly and Chance [43], Zhan et al. [44] and Nakano andAsada [45], respectively.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± standard error (SE) of five biological replicates is used to express the results. Using SPSS software (version 20), data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan test to identify significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments.

Results and discussion

Mycorrhizal colonization and symbiotic efficiency(Plant-fungi interaction)

Mycorrhizal colonization of V. faba roots was successful under all AM-inoculated treatments (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Under well-watered conditions, mycorrhizal colonization was robust, with fungal hyphal colonization (HC%) of 91.33 ± 4.83% and arbuscules (ARC%) and vesicles (VC%) percentages were 30.11 ± 1.59% and 74.25 ± 3.92%. Although drought stress negatively affects mycorrhizal colonization in V. faba roots, colonization is not completely inhibited. Drought stress significantly reduced colonization rates, with HC% dropping to 75.06 ± 3.97% and ARC to 16.66 ± 0.88%, suggesting an overall decline in symbiotic efficiency. Despite this reduction, colonization was still evident, indicating that mycorrhizal fungi retain some colonization ability even under water-limited conditions. Also, AM fungi can still confer benefits to host plants, albeit at a reduced level which indicates that drought can inhibit mycorrhizal development, but some fungal species can adapt and maintain symbiosis to a certain extent.

Table 1.

Mycorrhization levels in Vicia faba L. plants under the effect of drought stress (DS: 30%WHC)

| Treatments/ parameters |

Hyphal colonization (HC) | Vesicular colonization (VC) | Arbuscular colonization (ARC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0c | 0c | 0c |

| DS | 0c | 0c | 0c |

| KN | 0c | 0c | 0c |

| KN + DS | 0c | 0c | 0c |

| AM | 91.33 ± 4.832a | 74.25 ± 3.928a | 30.11 ± 1.593a |

| AM + DS | 75.06 ± 3.971b | 66.66 ± 3.527b | 16.66 ± 0.881b |

Data are means ± standard errors, means followed for the same letters in the columns do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

Fig. 1.

Symbiotic efficiency between mycorrhizal fungi and V. faba roots showed different mycorrhizal structures (hyphae, arbuscules and vesicles) using light microscope (10×). Control non-inoculated V. faba roots (a). Structures representative of AM (b, c and d) using these abbreviations: NC-HC (Non-colonized Host cells), IRH (Intraradical hyphae), Ves (vesicle) and Arb (arbuscule)

In drought-stressed plants, a shift in colonization structures was observed as revealed in a recent study on soybeans [13]. Although hyphal penetration remained relatively stable, the formation of vesicles and arbuscules decreased significantly as arbuscules are vital for nutrient exchange and are particularly sensitive to carbon limitation and water deficit [46]. This may be due to impaired carbohydrate allocation to the fungi as drought limits photosynthesis, reducing the carbon supply to the fungal symbiont [47]. As well, Huang et al. [48] also stated that AM fungal spore germination decreased under drought stress which resulted in a notable reduction in the production of novel endogenous fungal structures. The level of colonization under drought stress also depends on the fungal species used.

In this study, drought-stressed plants showed reduced root branching and overall root surface area, limiting potential entry points for fungal colonization. Mycorrhizal fungi typically rely on healthy root development for effective colonization. Consequently, the stress-induced reduction in fine root structures may partially explain the decreased colonization frequency [49, 50]. Additionally, drought stress may increase the deposition of lignin and suberin in root cortical tissues [51, 52], acting as a physical barrier to fungal entry.

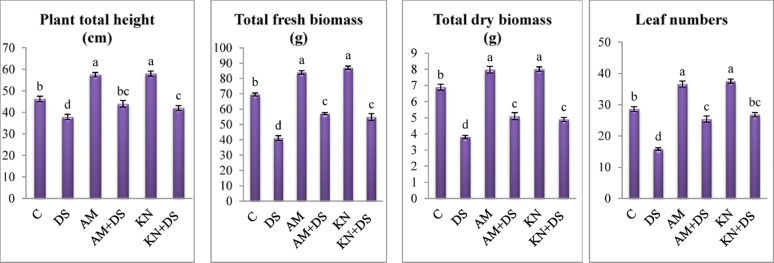

Plant growth and biomass

Results in Figs. 2 and 3 revealed that drought stress (30% WHC) significantly impaired the vegetative growth of V. faba, as evidenced by reductions in plant height, fresh and dry biomass, and leaf numbers. Compared to the control (90% WHC; p < 0.05), drought-stressed plants exhibited a 40.8 and 44.8% reduction in V. faba fresh and dry biomass. Plant height and leaf numbers were reduced by 18.2% and 44.7%, respectively. These results are consistent with previous studies on faba bean, malva and soybean plants under drought stress [8, 13, 53] as this stress severely restricts plant growth by disrupting water relations, reducing photosynthesis, and impairing nutrient uptake [7, 54]. Also, this stress severely restricts cell expansion and induces oxidative damage [8, 55] and increases the synthesis of senescence-associated genes that code for cysteine proteases which promote early senescence of leaves and flowers in plants [56].

Fig. 2.

The performance of V. faba L. plants exposed to normal irrigation (Control) and drought stress (DS: 30% WHC) under the effect of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM)

Fig. 3.

Comparison of statistical significance of differences in V. faba L. growth parameters across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC). Data are means ± standard errors, columns followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Duncan, p < 0.05

However, kinetin-treated plants (20 mg/L) showed improvement in plant fresh and dry biomass (33.39 and 28.68%, respectively as compared to drought-stressed plants without kinetin) and also enhanced leaf number (Fig. 3). The increases in plant height and fresh and dry biomass in V. faba align with Khurshid et al. [12] and Akter et al. [57] results. This improvement is due to the kinetin’s ability to delay leaf senescence, promote cell division, and enhance antioxidant defense mechanisms [58, 59]. A study by Rafiqul Islam et al. [17] revealed that the administration of exogenous kinetin increased endogenous kinetin levels, which in turn improved plants’ ability to overcome adverse growth impacts caused by water scarcity.

Similarly, AM-treated plants enhanced drought resilience where, under drought, it exhibited 38.76 and 34.2% greater fresh and dry biomass than non-AM, drought-stressed counterparts (p < 0.05). As well leaf number and plant height improved by 60.7 and 16.3%, respectively (Fig. 3). AM fungi are known to improve plant drought tolerance by improving root biomass and architecture, enhancing water uptake, cycling nutrients and improving soil structure [13, 24]. Through its hyphae, AM fungi improves nutrient uptake, especially N, P, and K, as well as water absorption [60, 61]. This is because the mycelium can spread and grow outside the rhizosphere and increase the root surface allowing the root area to absorb more nutrients that are immobile and rarely reach the plant’s roots [27, 62]. Also, this symbiotic association induces systemic changes in host plants, including improved antioxidant activity and osmolyte accumulation (shown later), which help maintain cellular homeostasis under drought conditions [63]. These physiological benefits likely contributed to the improved growth of mycorrhiza-treated V. faba plants under drought.

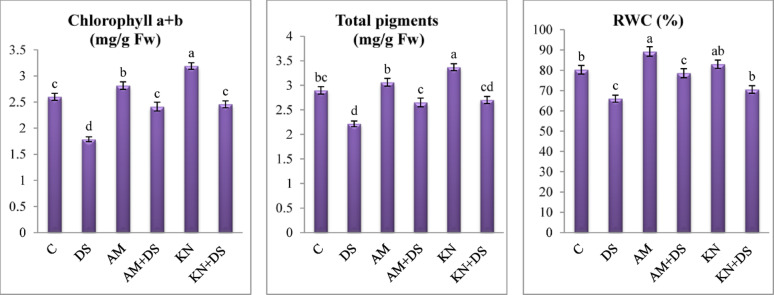

Photosynthetic pigments

Chlorophyll is the green pigment present in chloroplasts in which photosynthesis takes place, thus it is crucial to determine chlorophyll and other pigments under the different treatments (drought, kinetin and AM). Compared to the well-watered treatment (Fig. 4), the photosynthetic pigments showed steadily declining values throughout drought; it reduced total chlorophyll (a + b) and total pigments levels by 31.5 and 23.7% respectively. Similar outcomes under drought stress were noted in Avena nuda [64] and Malva parviflora [8] plants. The decline in chlorophyll under water-deficient conditions is attributed to pigment degradation, inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis, and increased oxidative damage. Also, by increasing the activity of chlorophyllase and decreasing the activity of other associated enzymes in the synthesis of chlorophyll, drought stress degrades pigments [65, 66]. According to Rafiqul Islam et al. [17] and Vitale et al. [67], stomatal closure and subsequently a decrease in photosynthetic capacity seemed to be the main causes of drought-stressed plants’ decreased photosynthesis. To enable a higher rate of photosynthesis, a higher CO2 fixation per unit of leaf area requires high stomatal conductance. The stomata stay closed for a long period during drought conditions, which lowers CO2 absorption and water loss to maintain plant water status [17].

Fig. 4.

One-way ANOVA for determining differences between means for chlorophyll a + b and total pigments and relative water content (RWC) in V. faba L. plants across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC). Data are means ± standard errors, columns followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

Furthermore, kinetin and AM treatment ameliorated this decline and maintained significantly higher chlorophyll levels compared to untreated counterparts. Both treatments significantly restored chlorophyll content, enhancing total chlorophyll (a + b) by 37.6 and 35.1% and total pigments by 22.2 and 19.9%. Kinetin counteracted drought effects by delaying senescence and maintaining photosynthetic machinery. This is attributed to kinetin’s ability to stabilize chloroplast membranes and promote chlorophyll biosynthesis [68] and enhance antioxidant enzyme activity, thereby reducing oxidative degradation of pigments [69, 70] that ultimately supports better photosynthetic efficiency under water-deficit conditions.

Likewise, during water stress, AM fungi increased the amount of chlorophyll and stomatal conductance compared to non-mycorrhizal ones under controlled and stressed conditions [71, 72]. Hashem et al. [50] stated that under drought-stressed and non-stressed conditions, AM-inoculated plants boosted pigment synthesis by decreasing chlorophyllase activity and upregulating the gene expression involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis.

Relative water content

The improved crop management in drought-prone areas depends on understanding the existing condition of water relations. RWC is a crucial feature among a number of water-related measures that are employed as an indicator for dehydration tolerance [73]. Drought-induced reductions in RWC led to turgor loss, which in turn reduced the amount of water available for plant cell division [17, 74]. We found that exposure of V. faba plants to drought stress (30% WHC) led to a significant decline in RWC which dropped significantly by 17.76% (Fig. 4), compared to well-watered controls (90% WHC) indicating water loss and reduced turgor. This reduction is a typical physiological response to water deficit and is indicative of the plant’s impaired ability to maintain turgor pressure and metabolic activity under stress [7, 75]. Due to the detrimental effects of drought on stomatal opening and closure processes, drought stress raises leaf temperature and decreases water availability, transpiration rate, and leaf water potential, all of which have an impact on plant water status [76].

It is worth noting that foliar-sprayed kinetin or mycorrhizal inoculation under drought stress significantly improved RWC in V. faba leaves by 7 and 19.1% compared to untreated stressed plants (Fig. 4), suggesting improved water retention and osmotic adjustment. Kinetin is known to delay senescence, and enhance osmolyte accumulation, all of which contribute to better hydration status under drought [58]. The observed increases in RWC in V. faba with kinetin application are consistent with Rafiqul Islam et al. [17] in maize plants suggesting that kinetin application assisted plants in maintaining their water status for improved growth. According to Malinowska et al. [77] reports, shoot-driven kinetin migrated basipetal towards the roots, causing the root system to grow so that it could forage for more water-absorbing space when there was a dearth of water. Therefore, plants can maintain better water status and flourish under water deficit by using kinetin-induced modulation of root structure and growth.

The alleviating of drought adverse effects on RWC by AM fungal inoculation in V. faba plants may be likely due to the improved root hydraulic conductivity and increased water uptake efficiency via the extended hyphal network [63, 78]. Our results are in line with those of Soliman et al. [13] and Oliveira et al. [79], who found that the water potential of soybean plants treated with AM fungi increased under water deficient circumstances. AM fungi also trigger physiological changes in host plants that improve osmotic adjustment and promote stomatal regulation, further contributing to improved hydration. The increase in RWC and biomass aligns with AM-induced upregulation of aquaporins and stress-responsive genes [63].

Stress markers (EL and H2O2)

Drought stress significantly increases EL and H2O2 in V. faba leaves, indicating compromised cell membrane integrity (Table 2). Under drought, EL of faba bean escalated from approximately 21.31% under well-watered conditions to over 51%. Quantitatively, H2O2 content provoked by 23.4% in drought-stressed plants relative to non-stressed controls (p < 0.05), showed the highest H2O2 content.

Table 2.

One-way ANOVA for determining differences between means of stress markers in V. faba L. plants across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC)

| Treatments/ parameters |

H2O2 (mg/g Fw) | El (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 9.74 ± 0.257bc | 26.028 ± 0.688c |

| DS | 12.02 ± 0.318a | 51.09 ± 1.352a |

| AM | 9.483 ± 0.25c | 21.308 ± 0.564d |

| KN | 9.189 ± 0.243c | 16.508 ± 0.437e |

| AM + DS | 10.51 ± 0.278b | 31.708 ± 0.838b |

| KN + DS | 10.44 ± 0.276b | 17.178 ± 0.45e |

Data are means ± standard errors, means followed for the same letters in the columns do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

The increase in EL correlated with elevated H2O2 levels (a marker of oxidative stress). The surge in H2O2 reflects impaired ROS scavenging mechanisms and heightened lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by elevated malondialdehyde in drought-stressed soybean plants [13]. These results corroborate findings in mung bean [80] and faba bean [81].

Foliar-sprayed kinetin (20 mg/L) reduced EL and H2O2 content by 66.37 and 13.14% relative to stressed plants (Table 3) (p < 0.05), surpassing the mitigation effect of AM fungi. Kinetin enhances enzymatic antioxidants and non-enzymatic scavengers like ascorbate-glutathione pools, as reported in Triticum aestivum [82]. Additionally, kinetin-treated plants retained higher chlorophyll content (Fig. 4), indicating preserved photosynthetic machinery as a critical factor in minimizing electron leakage and ROS generation in chloroplasts. This aligns with Merewitz et al. [83], who attributed cytokinin-induced drought resilience to delayed senescence and sustained photochemical efficiency. The decrease in H2O2 could thus be related to the protective effects of kinetin on plant photosynthetic machinery and cellular membranes, which damaged by oxidative stress. Our results are also consistent with Rafiqul Islam et al. [17], who reported that kinetin effectively reduced EL in maize grown under drought stress due to the antioxidant and protective properties of cytokinins. In wheat plants subjected to PEG-induced drought stress, kinetin-mediated recovery from membrane damage and an increase in cell viability were documented [84].

Table 3.

The percentages of the comparative effectiveness of kinetin (KN) vs. arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi in promoting V. faba L. plant growth under controlled and drought-stressed conditions based on measured morphological, physiological and biochemical parameters

| Parameters | Control conditions | Drought stressed conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetin (KN) |

Arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) | Kinetin (KN) |

Arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) | |

| Plant height (cm) | 25.59 | 24.29 | 11.05 | 16.34 |

| Total fresh biomass (g) | 25.10 | 20.69 | 33.39 | 38.74 |

| Total dry biomass (g) | 16.25 | 15.82 | 28.68 | 34.21 |

| Chlorophyll a + b (mg/g Fw) | 23.16 | 8.49 | 38.03 | 35.39 |

| Total pigments (mg/g Fw) | 16.29 | 5.88 | 22.17 | 19.90 |

| RWC (%) | 3.42 | 11.21 | 6.89 | 19.06 |

| El (%) | − 36.57 | − 18.13 | − 66.37 | − 65.33 |

| H2O2 (mg/g Fw) | − 5 0.74 | − 2.66 | − 13.14 | − 12.56 |

| Proline (µM/g Fw) | − 25.78 | 12.43 | 19.95 | 90.44 |

| Protein (mg/g Fw) | 44.98 | 95.47 | 38.99 | 53.19 |

| Carbohydrates (mg/g Dw) | 24.29 | 41.21 | 7.54 | 28.64 |

| Easily glomalin (mg/g Fw) | 8.26 | 34.10 | 12.70 | 58.50 |

| Total glomalin (mg/g Fw) | 2.79 | 27.29 | 6.71 | 55.41 |

| SOD (U/g Fw) | 53.06 | 49.61 | 26.52 | 25.60 |

| CAT (U/g Fw) | − 5.00 | −1.25 | 10.00 | 5.76 |

| POX (U/g Fw) | −1.96 | −1.44 | 18.56 | 7.95 |

*RWC: relative water content, El: electrolyte leakage, SOD: superoxide dismutase, CAT: catalase, and POX: peroxidase

Furthermore, AM inoculation significantly attenuated EL and H2O2 under drought as compared to untreated stressed plants (p < 0.05). These findings are mirror observations in Glycine max, where AM fungal colonization preserved membrane integrity under drought via ROS regulation [13, 85]. AM fungi enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, including CAT and POX, thereby improving ROS detoxification [63, 86]. Additionally, mycorrhizal plants exhibited improved root hydraulic conductivity and enhanced plant water and nutrient uptake, particularly phosphorus, which is essential for maintaining cellular membrane integrity [87]. AM fungi mitigated EL by enhancing osmotic adjustment via glomalin-related soil proteins and upregulating antioxidants. Lower H2O2 levels correlate with improved membrane stability and higher biomass in treated plants, suggesting preserved cellular function of kinetin application or AM fungal inoculation under stress.

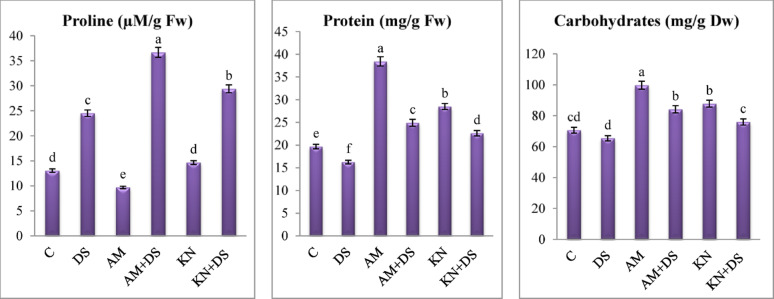

Osmotic and organic adjustment

Plants use a variety of physiological and biochemical responses such as osmoprotectant to defend against water-deficit stress. The most key osmoprotectants are proline, protein and soluble sugars [88]. In our investigation, proline, carbohydrates and soluble protein are affected by drought (30% WHC), kinetin (20 mg/L) and AM inoculation. The results demonstrated a significant increase in proline content in V. faba plants subjected to drought stress compared to well-watered controls (Fig. 5). Drought-stressed plants exhibited a two-fold increase in proline levels relative to non-stressed controls, reflecting an adaptive osmoprotective response and membrane protection [89].

Fig. 5.

One-way ANOVA for determining differences between means for osmotic substances in V. faba L. plants across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC). Data are means ± standard errors, columns followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

Application of kinetin or AM inoculation further enhanced proline accumulation under drought conditions. The drought + kinetin treatment resulted in a more than two-fold increase in proline compared to the non-stressed control, while drought + AM plants showed a three-fold increase. These findings suggest that both kinetin and mycorrhizal colonization enhance the osmotic adjustment capacity of V. faba under drought stress. Proline is well-established as a compatible solute that stabilizes proteins and membranes and maintains cellular turgor under dehydration [90]. As a molecular chaperone, proline’s antioxidant qualities have been found to be useful as a ROS scavenger. The pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase enzyme is highly expressed in stressed plants, which causes proline to build up [91].

Regarding carbohydrate, drought stress significantly affected its content in V. faba leaves as observed in Fig. 5. Compared to the well-watered control, stressed plants showed a 7.4% reduction in total soluble carbohydrates (p < 0.05), highlighting the adverse effects of water deficit on photosynthetic activity and carbon assimilation. Most obvious that kinetin and AM fungal inoculation under drought conditions led to a partial restoration of carbohydrate levels, registering 16.2 and 28.7% increase over the stressed untreated group. These findings underscore the capacity of both kinetin and AM fungi to alleviate drought-induced suppression of carbohydrate metabolism. The improvement in carbohydrate levels in AM-treated plants can be attributed to enhance water and mineral uptake, particularly phosphorus, which is critical for ATP production and photosynthetic efficiency [92]. Mycorrhizal colonization has also been shown to enhance stomatal regulation and photosynthetic pigment stability under water stress, leading to improved carbon fixation [13, 93]. In kinetin-treated plants, the improved carbohydrate status may reflect the hormone’s role in maintaining chloroplast integrity, thereby sustaining photosynthetic capacity during stress, delaying senescence-associated degradation processes and upregulating protein synthesis pathways through increased ribosomal activity and transcriptional stability [94].

The results presented in Fig. 5, indicate a significant decline in total protein content in stressed V. faba plants (16.3) compared to non-stressed controls (19.7 mg/g fresh weight). This decline is consistent with Farooq et al. [7] who indicated that drought impairs nitrogen metabolism and protein biosynthesis while promoting proteolysis. Under drought, kinetin application led to a moderate recovery in protein levels, increasing content by 38.9% relative to the drought-only (Table 3). Probably, the increase in protein level may be induced by elevated and potentially prolonged expression of target genes in response to the addition of the hormone [18].

AM-inoculated plants showed a greater increase (53.3%) over drought controls (Table 3).The protein enhancement under AM fungal inoculation can be attributed to improved nutrient acquisition, particularly nitrogen, and the modulation of nitrogen-assimilating enzymes such as nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase [60, 92]. AM fungal symbiosis also stabilizes cellular homeostasis, reducing proteolytic degradation and promoting biosynthetic pathways [93].

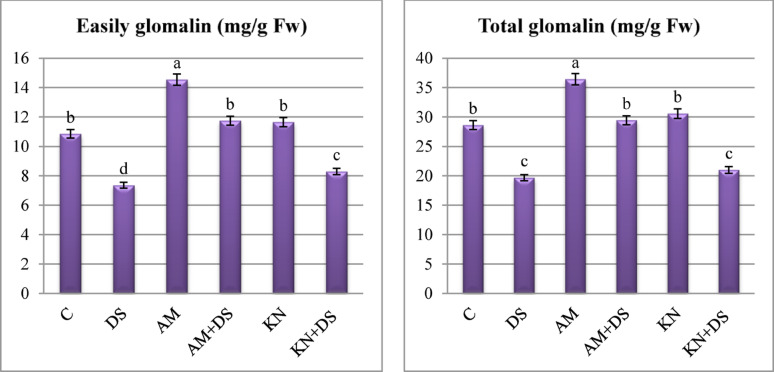

Easily and total glomalin production

Glomalin-related soil protein, a biomarker for AM fungal activity and soil aggregation, were markedly influenced by drought stress, mycorrhizal colonization (to greater extent) and kinetin (to lower extent). Non-inoculated V. faba plants under drought stress exhibited a significant decrease in its content compared to non-stressed controls (Fig. 6), indicating impaired fungal functionality under water deficit. Compared to the well-watered control, drought resulted in a 32.2 and 31.3% reduction in EEG and TG contents, indicating an adverse impact of water limitation on glomalin secretion and microbial activity. However, exogenous application of kinetin under drought increased EEG and TG by 12.70 and 6.71% relative to the drought treatment (Table 3). A more substantial improvement was observed in AM-inoculated plants, where EEG and TG increased by 34.1 and 27.3% compared to controls. Interestingly, AM-inoculated plants under drought stress demonstrated a substantial increase in glomalin production, with EEG and TG levels were approximately 1.5 times higher than non-inoculated stressed plants (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

One-way ANOVA for determining differences between means for glomalin content in V. faba L. plants across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC). Data are means ± standard errors, columns followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

Glomalin-related soil proteins are crucial role in soil health, water retention, and plant stress tolerance. Secreted by AM hyphae, glomalin acts as a hydrophobic glycoprotein that promotes soil aggregation and stabilizes soil structure by binding microaggregates into macroaggregates [95]. This structural improvement enhances soil porosity and water-holding capacity, which is vital under drought conditions. The observed decrease in EEG and TG under drought indicates that water limitation suppresses AM fungal metabolic activity and consequently glomalin production [96]. However, AM-inoculated plants exhibited significantly higher levels of EEG and TG under drought, suggesting that mycorrhizal symbiosis remains partially active even under stress. Our results are in line with Soliman et al. [13] and Cheng et al. [97], who found that the presence of AM fungi raised the levels of both EEG and TG while drought stress decreased their contents, suggesting that drought inhibits the glomalin synthesis. Higher glomalin levels are also linked to improved microbial habitat stability and nutrient cycling, thus supporting a healthier rhizosphere and promoting plant survival under stress [95, 96]. The enhancement of glomalin levels with kinetin application, although less pronounced than with AM fungi, is notable. Kinetin may support glomalin production indirectly by maintaining root vigor and its known role in stabilizing cellular membranes and improving water status in stressed plants could translate into better support for microbial partners in the rhizosphere. These findings reinforce the ecological importance of AM-derived glomalin in drought-stressed systems and reveal an auxiliary role for cytokinins like kinetin in sustaining microbial-plant interactions.

Antioxidant enzyme activity

Drought stress significantly influenced the activity of antioxidant enzymes in V. faba, with notable alterations in SOD, CAT, PPO, APX and POX levels (Fig. 7). Enzyme assays revealed that drought induced a pronounced increase in enzyme activities relative to well-watered controls, reflecting a robust oxidative stress response. SOD activity increased by 25.2%, CAT by 62.5%, PPO by 15.7%, APX by13.8% and POX by 26.8% under drought stress compared to well-watered controls. These results align with El-Sappah et al. [98] and Hasanuzzaman et al. [99, 100] who noted that drought induces ROS scavenging antioxidative defense systems. Under drought stress, the increase in SOD activity enhanced the dismutation of superoxide radicals into H2O2. Similarly, CAT and POX activity reflects an upregulation of H2O2-scavenging pathways.

Fig. 7.

One-way ANOVA for determining differences between means of antioxidant activity (superoxide dismutase: SOD, catalase: CAT, ascorbate peroxidase: APX, peroxidase: POX and poly phenol oxidase: PPO) in V. faba L. plants across the influence of kinetin (KN) and arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) under drought stress (DS: 30% WHC). Data are means ± standard errors, columns followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Duncan test, p < 0.05

Application of kinetin significantly moderated the stress-induced elevations in enzyme activity. In drought-stressed plants treated with kinetin, SOD, CAT and POX activities were elevated significantly by 26.52% for SOD, 10.00% for CAT and 18.56% for POX (Table 3), while a non-significant change was observed in the activities of APX and PPO relative to the drought stressed plants (Fig. 7). This result suggests that kinetin plays a regulatory role in modulating ROS levels by improving cellular water status and membrane stability, thereby reducing oxidative pressure [101]. Similarly, according to the findings of Chang et al. [102], exogenous kinetin may boost antioxidant enzyme activity and strengthen creeping bentgrass’s antioxidant defense against drought stress. Kinetin treatment in sesame plants under drought stress resulted an upsurge in POX, suggesting its role in suppressing the formation of harmful hydroxyl radicals [12, 103]. Additionally, treatment with zeatin riboside [104] or dihydrozeatin [105] was found to increase CAT and SOD activity. El-Badri et al. [106] demonstrated kinetin’s role in upregulating Cu/Zn-SOD and CAT2 genes in drought-stressed maize. Kinetin likely preserves enzyme functionality by maintaining cellular hydration and activating stress-signaling pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which trigger antioxidant biosynthesis.

Inoculation of V. faba with AM fungi also conferred significant mitigation of oxidative stress by exhibiting increases of 25.60% (SOD), 5.76% (CAT), and 7.95% (POX) (Table 3) in AM-treated drought-stressed plants over drought-stressed only (Fig. 7). These results indicate that AM fungi enhances antioxidant defense, possibly through enhanced water absorption and priming of systemic defense responses. Recent studies affirm that AM fungal symbiosis can modulate redox homeostasis and bolster drought resilience in legumes through antioxidant activation and improved physiological status [85, 107]. Collectively, an illustrative overview for the effect of drought on V. faba plants and the role of kinetin or AM in regulating the drought tolerance by preserving the morphological and physiological characteristics, antioxidant enzyme activity and osmolytes synthesis was represented in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Illustrative overview for the effect of drought on V. faba plants and the role of kinetin or AM fungi in regulating the drought tolerance

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that drought stress in V. faba significantly impairs physiological and biochemical functions. However, exogenous kinetin and inoculation with endophytic mycorrhizal fungi independently improved its tolerance. These improvements are mediated via better growth, water retention, enhanced antioxidant defenses, and maintenance of photosynthetic pigments. Integrating kinetin and endophytic mycorrhizal fungi offers a promising strategy for enhancing drought resilience under climate-induced water scarcity in V. faba and could serve as a sustainable strategy to improve crop productivity and may be practically implemented in arid and semi-arid agricultural systems to mitigate drought-induced yield losses. Future research should focus on identifying specific fungal strains and optimal application protocols for field conditions. Understanding the molecular interactions between kinetin signaling and fungal symbiosis will pave the way for sustainable agricultural practices.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the financial support from the Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, Egypt for funding open access publication.

Abbreviations

- ARC

Arbuscular colonization

- AM

Arbuscular mycorrrhizal

- APX

Ascorbate peroxidase

- CAT

Catalase

- EEG

Easily extractable glomalin

Hydrogen peroxide

- HC

Hyphal colonization

- POX

Peroxidase

- PPO

Polyphenol oxidase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RWC

Relative water content

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- TG

Total glomalin

- VC

Vesicular colonization

- WHC

Water holding capacity

Author contributions

All authors shared in Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Plant materials were attained after permission from the Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.”

Experimental research and field studies on plants

“All relevant institutional, national and international guidelines and legislation were compiled or adhered to in the production of this study”.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aliniaeifard S, Rezayian M, Mousavi SH. Drought stress: involvement of plant hormones in perception, signaling, and response. In: Ahammed GJ, Yu J, editors. Plant hormones and climate change. Singapore: Springer; 2023. 10.1007/978-981-19-4941-8_10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin J, Gentine P, Zhou S, Sullivan SC, Wang R, Zhang Y, Guo S. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–10. 10.1038/s41467-018-06765-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H, Huntingford C, Wiltshire A, Sitch S, Mercado L. Compensatory climate effects link trends in global runoff to rising atmospheric CO2 concentration. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14: 124075. 10.1088/1748-9326/ab5c6f. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen I, Zandalinas SI, Huck C, Fritschi FB, Mittler R. Meta-analysis of drought and heat stress combination impact on crop yield and yield components. Physiol Plant. 2021;171:66–76. 10.1111/ppl.13203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zia R, Nawaz MS, Siddique MJ, Hakim S, Imran A. Plant survival under drought stress: implications, adaptive responses, and integrated rhizosphere management strategy for stress mitigation. Microbiol Res. 2021;242: 126626. 10.1016/j.micres.2020.126626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JS, Kidokoro S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Regulatory networks in plant responses to drought and cold stress. Plant Physiol. 2024;195(1):170–89. 10.1093/plphys/kiae105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farooq M, Wahid A, Kobayashi N, Fujita D, Basra SMA. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Agron Sustain Dev. 2009;29(1):185–212. 10.1051/agro:2008021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelhameed RE, Soliman ERS, Gahin H, Metwally RA. Enhancing drought tolerance in Malva parviflora plants through metabolic and genetic modulation using Beauveria Bassiana inoculation. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:662. 10.1186/s12870-024-05340-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarl BA, Musumba M, Smith JB. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation strategies in Egypt’s agricultural sector. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 2015;20:1097–109. 10.1007/s11027-013-9520-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelfattah M. (2021). Climate change impact on water resources and food security in Egypt and possible adaptive measures. 10.1007/978-3-030-72987-5_10

- 11.Khalil SE, Hozayen WM, Abdel-Monem AM. Physiological and anatomical responses of Faba bean plants to drought and water-saving treatments. Agronomy. 2021;11(3):462. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khurshid R, Perveen S, Hafeez MB. Combined application of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and kinetin on maize growth, chlorophyll, osmoregulation, and oxidative metabolism under drought stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2025. 10.1007/s42729-025-02397-w. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soliman ERS, Abdelhameed RE, Metwally RA. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in drought-resilient soybeans (Glycine max L.): unraveling the morphological, physio-biochemical traits, and expression of polyamine biosynthesis genes. Bot Stud. 2025;66:9. 10.1186/s40529-025-00455-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieber JJ, Schaller GE. Cytokinins. Arabidopsis Book. 2014;12: e0168. 10.1199/tab.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hai NN, Chuong NN, Tu NHC, Kisiala A, Hoang XLT, Thao NP. Role and regulation of cytokinins in plant response to drought stress. Plants. 2020;9(4):422. 10.3390/plants9040422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abeed AH, Eissa MA, Abdel-Wahab DA. Effect of exogenously applied jasmonic acid and kinetin on drought tolerance of wheat cultivars based on morpho-physiological evaluation. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021;21(1):131–44. 10.1007/s42729-020-00348-1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rafiqul Islam M, Shahinur Islam M, Akter N, Mohi-Ud-Din M, Golam Mostofa M. Foliar application of cytokinin modulates gas exchange features, water relation and biochemical responses to improve growth performance of maize under drought stress. Phyton. 2022. 10.32604/phyton.2022.018074. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussein Y, Amin G, Azab A, Gahin H. Induction of drought stress resistance in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) plant by salicylic acid and kinetin. Journal of Plant Sciences. 2015;10(4):128. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeyaraj S, Beevy SS. Insights into the drought stress tolerance mechanisms of sesame: the queen of oilseeds. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024. 10.1007/s00344-024-11353-4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madouh TA, Quoreshi AM. The function of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with drought stress resistance in native plants of arid desert ecosystems: a review. Diversity. 2023;15(3):391. 10.3390/d15030391. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelhameed RE, Metwally RA. The potential utilization of mycorrhizal fungi and Glycine betaine to boost the Fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum L.) tolerance to chromium toxicity. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2024. 10.1007/s42729-024-02131-y. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metwally RA, Taha MA, El-Moaty NMA, Abdelhameed RE. Attenuation of zucchini mosaic virus disease in cucumber plants by mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;43:54. 10.1007/s00299-023-03138-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Zhou L, Chen G, Yao M, Liu Z, Li X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance drought resistance and alter microbial communities in maize rhizosphere soil. Environ Technol Innov. 2025. 10.1016/j.eti.2024.103947. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. 3rd ed. Academic; 2008.

- 25.Morsy A, Mehanna H. Improving growth, and productivity of faba bean cultivars grown under drought stress conditions by using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in sandy soil. SVU-International J Agricultural Sci. 2022;4(3):223–42. 10.21608/svuijas.2022.166627.1239. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh M, Singh P. Enhancing growth and drought tolerance in tomato through arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Rodriguésia. 2024;75(e00482024). 10.1590/2175-7860202475079.

- 27.Metwally RA, Abdelhameed RE, Azb MA, Soliman ERS. Modulation of morpho-physio and genotoxicity induced by Cr stress via application of glycine betaine and arbuscular mycorrhiza in fenugreek. Physiol Plant. 2025. 10.1111/ppl.70297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porcel R, Ruiz-Lozano JM. Arbuscular mycorrhizal influence on plant performance under stress conditions. J Plant Physiol. 2004;161(7):781–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kakouridis A, Hagen JA, Kan MP, Mambelli S, Feldman LJ, Herman DJ. Routes to roots: direct evidence of water transport by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to host plants. New Phytol. 2022;236(1):210–21. 10.1111/nph.18281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han Y, Lou X, Zhang W, Xu T, Tang M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhanced drought resistance of Populus Cathayana by regulating the 14-3-3 family protein genes microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10(3). 10.1128/spectrum.02456-21. Article e0245621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Liu Y, Lu J, Cui L, Tang Z, Ci D, Zou X, Zhang X, Yu X, Wang Y, Si T. The multifaceted roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in peanut responses to salt, drought, and cold stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023. 10.1186/s12870-023-04053-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips JM, Hayman DS. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1970;55(1):158–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrs HD, Weatherley PE. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust J Biol Sci. 1962;15(3):413–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Ann Bot. 1996;78:389–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velikova V, Yordanov I, Edreva A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain treated bean plants, protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000;151:59–66. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–6. 10.1021/ac60111a017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowry O, Rosebrough N, Farr A, Randall R. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright SF, Upadhyaya A. Extraction of glomalin, a glycoprotein produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, from soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1996;60(4):1295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beyer WF, Fridovich I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:559–66. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. In: Methods in enzymology. San Diego: Academic; 1984. p. 121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maehly AC, Chance B. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem Anal. 1954;1:357–424. 10.1002/9780470110171.CH14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhan L, Li Y, Hu J, Pang L, Fan H. Browning inhibition and quality preservation of fresh-cut Romaine lettuce exposed to high intensity light. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2012;14:70–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–80. 10.1093/OXFORDJOURNALS.PCP.A076232. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, Schroeder-Moreno M, Giri B, Hu S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their responses to nutrient enrichment. In: Giri B, Prasad R, Varma A, editors. Root biology. Soil biology. Volume 52. Cham: Springer; 2018. 10.1007/978-3-319-75910-4_17. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Augé RM. Water relations, drought and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mycorrhiza. 2001;11(1):3–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang Y-M, Zou Y-N, Wu Q-S. Alleviation of drought stress by mycorrhizas is related to increased root H2O2 efflux in trifoliate orange. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miransari M. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to plant growth under different types of soil stress. Plant Biol. 2010;12(4):563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hashem A, AbdAllah EF, Alqarawi AA, Egamberdieva D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant stress tolerance. Plant Microbiome. 2018;5514–04. 10.1007/978-981-10-.

- 51.Moura-Sobczak J, Souza U, Mazzafera P. Drought stress and changes in the lignin content and composition in Eucalyptus. BMC Proc. 2011;5(7). 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S7-P103.

- 52.Li D, Yang J, Pak S, Zeng M, Sun J, Yu S, He Y, Li C. PuC3H35 confers drought tolerance by enhancing lignin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the roots of Populus ussuriensis. New Phytol. 2022;233(1):390–408. 10.1111/nph.17799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muktadir MA, Adhikari KN, Merchant A, Belachew KY, Vandenberg A, Stoddard FL, Khazaei H. Physiological and biochemical basis of Faba bean breeding for drought adaptation—a review. Agronomy. 2020;10(9):1345. 10.3390/agronomy10091345. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buragohain K, Tamuly D, Sonowal S, et al. Impact of drought stress on plant growth and its management using plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Indian J Microbiol. 2024;64:287–303. 10.1007/s12088-024-01201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zlatev Z, Lidon F. An overview on drought induced changes in plant growth, water relations and photosynthesis. Emirates J Food Agric. 2012;24(1).

- 56.Botha AM, Kunert KJ, Cullis CA. Cysteine proteases and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought: A still greatly unexplored association plant. Cell Environ. 2017;40:1679–90. 10.1111/pce.12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akter N, Islam MR, Karim MA, Hossain T. Alleviation of drought stress in maize by exogenous application of gibberellic acid and cytokinin. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2014;17:41–8. 10.1007/s12892-013-0117-3. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pospíšilová J, Synková H, Rulcová J. Cytokinins and water stress. Biol Plant. 2000;43(3):321–8. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaya C, Tuna AL, Okant AM. Effect of foliar applied Kinetin and Indole acetic acid on maize plants grown under saline conditions Turkish. J Agric Forestry. 2010;34:529–38. 10.3906/tar-0906-173. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Metwally RA, Soliman SA, Abdel Latef AA, Abdelhameed RE. The individual and interactive role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma viride on growth, protein content, amino acids fractionation, and phosphatases enzyme activities of onion plants amended with fish waste. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;214: 112072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yilmaz H. Enhancements in morphology, biochemicals, nutrients, and L-Dopa in faba bean through plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Sci Rep. 2025;15:7390. 10.1038/s41598-025-92486-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheikh-Assadi M, Khandan-Mirkohi A, Taheri MR, Babalar M, Sheikhi H, Nicola S. Arbuscular mycorrhizae contribute to growth, nutrient uptake, and ornamental characteristics of statice (Limonium sinuatum [L.] Mill.) subject to appropriate inoculum and optimal phosphorus. Horticulturae. 2023;9(5):564. 10.3390/horticulturae9050564. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruiz-Lozano JM, Aroca R, Zamarreño ÁM, Molina S, Andreo-Jiménez B, Porcel R, García-Mina JM, Ruyter-Spira C, López-Ráez JA. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis induces Strigolactone biosynthesis under drought and improves drought tolerance in lettuce and tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39(2):441–52. 10.1111/pce.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang X, Liu W, Lv Y. Effects of drought stress during critical periods on the photosynthetic characteristics and production performance of naked oat (Avena nuda L). Sci Rep. 2022. 10.1038/s41598-022-15322-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anjum SA, Xie XY, Wang LC, Saleem MF, Man C, Lei W. Morphological, physiological and biochemical responses of plants to drought stress. Afr J Agric Res. 2011;6(9):2026–32. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdelhaleim MS, Rahimi M, Okasha SA. Assessment of drought tolerance indices in faba bean genotypes under different irrigation regimes. Open Life Sci. 2022;17(1):1462–72. 10.1515/biol-2022-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vitale L, di Tommasi P, Arena C, Riondino M, Forte A. Growth and gas exchange response to water shortage of a maize crop on different soil types. Acta Physiol Plant. 2009;31:331–41. 10.1007/s11738-008-0239-2. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glanz-Idan N, Lach M, Tarkowski P, Vrobel O, Wolf S. Delayed leaf senescence by upregulation of cytokinin biosynthesis specifically in tomato roots. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:922106. 10.3389/fpls.2022.922106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dobra J, Motyka V, Dobrev P, Malbeck J, Prášil IT, Haisel D, Gaudinová A, Havlová M, Gubis J, Vanková R. Comparison of hormonal responses to drought and cold in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48(3):209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ali B, Hayat S, Ahmad A. 24-epibrassinolide protects against the stress generated by salinity and nickel in vigna radiata L. by enhancing antioxidative systems. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49(3):333–42. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdel-Salam E, Alatar A, El-Sheikh MA. Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alleviates harmful effects of drought stress on Damask Rose. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25:1772–80. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jabborova D, Annapurna K, Azimov A, Tyagi S, Pengani KR, Sharma P, Vikram KV, Poczai P, Nasif O, Ansari MJ, Sayyed RZ. Co-inoculation of biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizae for growth promotion and nutrient fortification in soybean under drought conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:947547. 10.3389/fpls.2022.947547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arjenaki FG, Jabbari R, Morshedi A. Evaluation of drought stress on relative water content, chlorophyll content and mineral elements of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties. Int J Agric Crop Sci. 2012;4:726–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khan MSA, Karim MA, Mahmud AA, Parveen S, Bazzaz MM. Plant water relations and proline accumulations in soybean under salt and water stress environment. J Plant Sci. 2015;3:272–8. 10.11648/J.JPS.20150305.15. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chowdhury AK, Karim MA, Haque MM, Khaliq QA, Ahmed JU. Effect of water stress on plant water status of French bean (Phaseolus vulgais L). Indian J Plant Physiol. 2010;15:131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar K, Gill S, Fujita M. Drought stress responses in plants, oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. Clim Change Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. 2014. 10.1002/9783527675265.ch09. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malinowska KM, Myśków B, Czyczyło-Mysza I, Góralska M. Study on changes and relationships of physiological and morphological parameters of rye subjected to soil drought stress. Acta Agrophys. 2018;25:261–75. 10.31545/aagr/93584. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boutasknit A, Baslam M, Ait-El-Mokhtar M, Anli M, Ben-Laouane R, Douira A, El Modafar C, Mitsui T, Wahbi S, Meddich A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi mediate drought tolerance and recovery in two contrasting Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) ecotypes by regulating stomatal, water relations, and (in) organic adjustments. Plants. 2020;9(1): 80. 10.3390/plants9010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oliveira TC, Cabral JSR, Santana LR, Tavares GG, Santos LDS, Paim TP, Müller C, Silva FG, Costa AC, Souchie EL, Mendes GC. The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus Clarus improves physiological tolerance to drought stress in soybean plants. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ali Q, Javed MT, Noman A, et al. Assessment of drought tolerance in mung bean cultivars/lines as depicted by the activities of germination enzymes, seedling’s antioxidative potential and nutrient acquisition. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2018;64:84–102. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kenawy ER, Rashad M, Hosny A, Shendy S, Gad D, Saad-Allah KM. Enhancement of growth and physiological traits under drought stress in Faba bean (Vicia Faba L.) using nanocomposite. J Plant Interact. 2022;17(1):404–18. 10.1080/17429145. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gupta N, Thind SK, Bains NS. Kinetin alleviates drought stress and sustains grain wheat yield by enhancing antioxidant defence and osmotic adjustment. J Agron Crop Sci. 2020;206(3):358–69. 10.1111/jac.12391. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Merewitz EB, Gianfagna T, Huang B. Effects of SAG12-ipt and HSP18.2-ipt expression on cytokinin production, root growth, and leaf senescence in creeping bentgrass exposed to drought stress. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2016;141(5):1–12. 10.21273/JASHS03871-16. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaur A, Thind SK. Effects of cytokinins on membrane stability and cell viability of wheat crop under PEG-induced drought condition. J Environ Biol. 2018;39:1041–6. 10.22438/jeb/. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Begum N, Qin C, Ahanger MA, Raza S, Khan MIR, Ahmed N. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:630892. 10.3389/fpls.2021.630892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang F, Jia-Dong HE, Qiu-Dan NI. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve drought tolerance of Glycine max L. by regulating photosynthetic characteristics and antioxidant defense systems. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021;40(3):1274–87. 10.1007/s00344-020-10190-5. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aroca R, Ruiz-Lozano JM, Zamarreño AM, Paz JA, García-Mina JM, Pozo MJ, López-Ráez JA. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis influences strigolactone production under salinity and alleviates salt stress in lettuce plants. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sumera I, Asghari B. Effect of drought and abscisic acid application on the osmotic adjustment of four wheat cultivars. J Chem Soc Pak. 2010;32:13–9. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;59(2):206–16. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hayat S, Hayat Q, Alyemeni MN, Wani AS, Pichtel J, Ahmad A. Role of proline under changing environments: a review. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7(11):1456–66. 10.4161/psb.21949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ghosh UK, Islam MN, Siddiqui MN, Cao X, Khan MAR. Proline, a multifaceted signalling molecule in plant responses to abiotic stress: understanding the physiological mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2022;24:227–39. 10.1111/plb.13363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith SE, Jakobsen I, Grønlund M, Smith FA. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for Understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiol. 2019;156(3):1050–7. 10.1104/pp.111.174581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alqarawi AA, Abd_Allah EF, Hashem A, Alqurashi AM, Alshahrani TS. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in alleviating drought stress in Helianthus annuus by enhancing antioxidant defense systems and photosynthetic efficiency. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2014;21(6):501–7. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.09.005. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lamattina L, Anchoverri V, Conde RD, Lezica RP. Quantification of the kinetin effect on protein synthesis and degradation in senescing wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;83(3):497–9. 10.1104/pp.83.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rillig MC, Wright SF, Nichols KA, Schmidt WF, Torn MS. Large contributions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to soil carbon pools in tropical forest soils. Plant Soil. 2002;233(2):167–77. 10.1023/A:1010364221169. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu QS, Xia RX, Zou YN. (2014). Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and stress tolerance of citrus plants. In R. K. Varma & A. Prasad, editors, Mycorrhizas—Functional Processes and Ecological Impact (pp. 255–280). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-14364-3_11

- 97.Cheng S, Zou Y-N, Kuča K, Hashem A, Abd_Allah EF, Wu Q-S. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying enhanced drought tolerance in plants mediated by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:809473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.El-Sappah AH, Huang Q, Wu D, Zhang F, Yan M. Antioxidant defense system and gene expression in plants under drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants. 2021;10(8):1392. 10.3390/plants10081392.34371595 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hasanuzzaman M, Raihan MRH, Masud AAC, Rahman K, Nowroz F, Fujita M, Nahar K. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under drought stress. Plants. 2021;10(2):259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hasanuzzaman M, Bhuyan MHMB, Raza A, Hawrylak-Nowak B, Matraszek-Gawron R, Nahar K, Fujita M. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of ROS and redox signaling. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;191:36–59. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.01.005. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang J, Zuo Y, Huang X, Zhang Y. Cytokinin-induced antioxidant regulation improves drought tolerance in leguminous crops. Environ Exp Bot. 2022;194:104735. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104735. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chang Z, Liu Y, Dong H, Teng K, Han L, et al. Effects of cytokinin and nitrogen on drought tolerance of creeping bentgrass. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hussein Y, Amin G, Gahin H. Antioxidant activities during drought stress resistance of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) plant by Salicylic acid and Kinetin. Res J Bot. 2016;11:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gidrol X, Lin WS, Dégousée N, Yip SF, Kush A. Accumulation of reactive oxygen species and oxidation of cytokinin in germinating soybean seeds. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224(1):21–8. pmid:7521301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clarke SF, Guy PL, Burritt DJ, Jameson PE. Changes in the activities of antioxidant enzymes in response to virus infection and hormone treatment. Physiol Plant. 2002;114(2):157–64. pmid:11903962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.El-Badri AM, Batool M, Wang J, Mohamed IA, Khatab A, Sherif A, Kuai J. Kinetin-mediated modulation of antioxidant defense system enhances drought tolerance in maize by regulating proline metabolism and MAPK signaling pathways. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;185:274–83. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Berta G, Fusconi A, Trotta A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and plant drought tolerance: insights into physiological and molecular mechanisms. Mycorrhiza. 2023;33(2):123–38. 10.1007/s00572-023-01125-9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.