Abstract

Background

In recent years, improper agricultural management practices have led to the loss of biodiversity and poor fruit quality in orchards. Converting conventional farming to organic farming is an environmentally responsible approach to improving sustainable fruit production. However, questions remain regarding how the microbial community responds to different farming practices in citrus trees. Specifically, this study aims to investigate how organic and conventional farming affect the microbial community structure and functional diversity in the Gannan navel orange orchard using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and Biolog Eco-Plate analysis.

Results

The results showed that the soil bacterial diversity (α-diversity index) under organic farming was higher than that under conventional farming. Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were more abundant in root and fruit compartments under organic farming, indicating that organic farming promotes the enrichment of copiotrophic bacteria (r-strategists). Furthermore, organic farming resulted in a considerable increase in the relative abundance of Burkholderia and Streptomyces in root tissues. Interestingly, organic farming exhibited a more complex bacterial network. Biolog analysis further revealed higher functional diversity of the soil microbial community under organic farming when compared with that under conventional farming.

Conclusions

These findings provide evidence that organic farming improves the bacterial community structure and promotes microbial functional diversity in the citrus orchards, contributing to the overall health and production of the citrus crop. Synthetic microbial communities of the organic citrus orchards hold great promise for more efficient environment-friendly orchard management towards sustainable agriculture.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04271-2.

Keywords: Gannan navel orange, Conventional farming, Organic farming, Microbial community, Functional diversity, Carbon source utilization

Introduction

Conventional agricultural practices, mostly reliant on chemical inputs, have made significant progress in agricultural production to ensure global food security in recent decades [1–4]. Nevertheless, the heavy reliance on synthetic chemical fertilizers and pesticides has resulted in substantial negative externalities, such as biodiversity loss [5], soil erosion [6] or acidification [7], and air pollution [8, 9]. Additionally, there are detrimental effects on human health [10, 11]. Hence, it is necessary to explore alternative approaches to reducing dependency on agrochemicals, improving agricultural output, and achieving the equilibrium between productivity and sustainability [12]. Organic farming not only reduces chemical inputs but may also enhance soil health by improving microbial diversity and community structure [13].

Agricultural management practices need to change to meet agriculture and food system development goals [14]. Organic farming, although not a silver bullet, seems to be a potential strategy for maintaining biodiversity and sustaining crop production [15]. Organic farming also dramatically reduces environmental impacts, enhances ecosystem services, and contributes to human health and well-being [16–21]. Compared to conventional farming, organic farming applies organic fertilizers (e.g., manure, biochar, animal waste), biological control for pest management, and green manuring or grass mowing for weed control [22]. Moreover, organic farming incorporates various techniques, such as intercropping and stubble-mulch, to improve soil fertility and maintain food productivity by nurturing a beneficial soil microbiome [23–25].

Chemical pesticides or fertilizers are not allowed or minimized (i.e., copper-based fungicides) in organic farming; therefore, soil microorganisms perform a key role in nutrient mineralization, utilization, and cycling [26]. Hence, it is particular important to explore the potential of soil microbiomes in promoting agricultural sustainability. Organic farming management practices promote the abundance and diversity of most microorganisms [13, 27]. After conventional to organic farming conversion, soil microbial communities adapt to new conditions and function accordingly, such as improving soil microbial biomass [28], changing soil organic matter in labile fractions [29], enhancing plant associations with beneficial microorganisms [30], and providing positive regulations [31]. Organic farming increases functional diversity of belowground microorganisms (i.e., soil and root niches) [32, 33] as well as aboveground microbial communities (leaves and fruits) [12, 34] as compared to conventional farming. Low-input farming systems are featured by the higher complexity and biodiversity of microbial networks compared to conventional farming systems [35, 36]. Changes in soil microorganisms and keystone taxa driven by organic fertilization also enhance the resistance and resilience against environmental disturbances through the diversified bacterial communities and copiotrophic bacterial assemblages [37]. Soil and phyllosphere bacterial communities play critical roles in regulating nutrient cycling, soil fertility, and plant health [22, 24, 35]. In this regard, manipulating the microbial community structure and composition to enrich beneficial bacteria and reduce harmful bacteria might provide a basis for improving plant growth and agricultural sustainability [35]. Although impacts of agricultural management on soil [32, 37], rhizosphere [35, 38], or phyllosphere microbiomes [12, 39, 40] have been studied, the overall microbial structure and functionality along the soil-plant continuum in organic citrus orchards has been less well-studied.

Citrus, one of the top three fruit crops worldwide [41], serves as an ideal model plant for microbial taxonomic, genomic, and functional studies [42]. The Gannan navel orange is among the most prestigious fruits in China, with high internal quality in terms of sweetness, juice percentage, and high levels of vitamin C [43]. However, the quality of orchard soils has recently declined due to improper agricultural management and adverse environmental factors. Deterioration of the eco-environment and disease challenges also negatively affect global citrus production [44]. In particular, soil acidification, which is worsened by intensive application of chemical nitrogen fertilizers, has emerged as a significant problem for citrus production in China [45].

To date, most studies focus on harnessing citrus-microbiome interactions to address biotic and abiotic pressures [32, 44]. However, limited research has been conducted on microbial changes along the soil-plant continuum in citrus orchards under different agricultural management practices. In this study, we combined microbiological sequencing and Biolog-Eco microplate analysis to investigate (a) how different agricultural management practices affect the diversity and composition of microbial communities, (b) the characteristics of the core microbial community and its association with different farming practices, and (c) the effects of different management practices on the capacity of microbial communities to utilize carbon.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

Orange orchards selected for conventional (C) and organic farming (O, certificate valid since December 9, 2015) study were located in Tanshi Village (26°07’58.9” N, 115°34’42.6” E), Yudu County, Jiangxi Province, China. The citrus variety was New Holland navel orange planted in 2013. This region has a humid subtropical climate with 1507 mm of annual precipitation and 1622 h of sunshine. The average annual temperature is 19.7℃, with the lowest in January (8.2℃) and the highest in July (29.7℃). Nine plots (3 trees/plot) were selected from each farming system as experimental replicates. For each tree, the soil sample was collected at 0–15 cm depth from the 4 ordinate directions along the dripline and then pooled as a single sample. Before fertilization in January 2022, five pooled soil samples were taken from each farming system to measure their physicochemical characteristics (Table 1). Under conventional farming, compound fertilizers (2–3 kg per plant per year) and pesticides were applied, and the synthetic herbicide glufosinate-ammonium was used to control weeds. Organic fertilizers (compost of maize flour, rape cake, and brown sugar at a mass ratio of 25:75:1; 8–10 kg per plant per year) and plant extracts (azadirachtin, matrine, and d-limonene) and microbial biopesticides (spinosad) were applied for organic farming. Different from conventional farming, organic farming relied on cover crops and manual and mechanical weed management.

Table 1.

Comparison of soil properties between organic and conventional agricultural practices in citrus orchards (means ± standard error, n = 4). Soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), mineral nitrogen (Nmin), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK)

| Treatment | pH (H2O) | SOM (g kg−1) | TN (g kg−1) | Nmin (g kg−1) | AP (g kg−1) | AK (g kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farming | 3.90 ± 0.33 a | 14.10 ± 4.74 a | 0.29 ± 0.15 a | 83.98 ± 41.66 a | 96.01 ± 38.74 a | 149.03 ± 72.61 a |

| Organic farming | 5.04 ± 0.38 b | 42.25 ± 8.78 b | 0.77 ± 0.17 b | 54.65 ± 23.58 a | 123.88 ± 26.83 a | 72.21 ± 35.86 b |

Different lowercase letters associated with each set of numbers represent significant differences between organic and conventional agricultural practices by the LSD test (P < 0.05).

Soil, root, leaf, and fruit sampling

Citrus trees without symptoms of pests, diseases, and nutrient deficiencies were sampled at the fruit expansion stage in July 2022. We sampled nine orange trees as biological replications for each farming practice.

The rhizosphere soil and root samples were taken at the depth of 10–15 cm [46]. Briefly, the root was carefully shaken and gently brushed to remove loosely adherent soil. Roots were washed in the sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and gently agitated with sterile forceps to remove the soil from the root surface. The resulting soil was briefly centrifuged to collect and store as rhizosphere soil (RS) at 4 °C. Then, root samples were washed with sterilized water three times and wiped with paper towels. We sampled the non-rooted soil from the same plot as bulk soil (BS). The pooled soil or root samples from each tree were stored at −20 °C for further analysis. Nine root and five bulk soil samples were used as independent biological replicates.

Fruits of similar size (5–6 cm in diameter) and mature leaves (free of pests and diseases) closest to the fruit were selected from the external middle canopy in four directions (east, south, west, and north). Eight leaves and four fruits from each tree were harvested as a pooled leaf or fruit sample, with nine trees as independent biological replicates for each farming system. Samples were instantly placed in liquid nitrogen and then kept at − 80 °C.

Functional diversity of the soil microbial community

The Biolog Eco-Plate (Biolog Inc., CA, USA) was used to examine the functional diversity of rhizosphere and bulk soil microorganisms [47]. Each plate contained 96 wells with three replicates of water control and 31 different carbon sources which were classified into six major categories: polymers, carbohydrates, phenolic acids, carboxylic acids, amino acids, and amines [48]. Fresh rhizosphere (RS) or bulk (BS) soil (~ 10 g) was weighed in a 250 ml flask containing 90 ml of sterilized 0.85% NaCl solution, shaken at 200 rpm for 30 min, suspended, and diluted to 10−3 with 0.85% NaCl solution. Applied 150 µl of the diluted sample to the individual well of the 96-well microplate for 9-day incubation at 25 °C and recorded the absorbance value every 24 h at 590 nm. The average well color development (AWCD) was calculated to assess the utilization abilities of carbon sources by the soil microbial community [49, 50]. The 72-hour absorbance was used to analyze the Shannon-Weiner (H) [51, 52], Simpson (D) [50], Pielou evenness (J) [52], and Richness index (E) [53] using the following equations:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

where Pi is the ratio of the relative absorbance of well i to the total absorbance of all wells on a plate. S is the number of wells with color change. ei is a positive (1) or negative (0) test for the well i, calculated based on the optical density (OD) of absorbance units.

DNA extraction, sequencing and data analyses

The genomic DNA was isolated following the CTAB/SDS method [54]. DNA concentration and purity were monitored using 1% agarose gels, and then diluted to 1 µg µL−1 using aqua sterilisata. Bacterial 16 S rRNA genes were amplified using the following primer set: 799 F (5′-AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-3′) and 1193R (5′-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC-3′). DNA libraries were generated using the TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform to generate 250-bp paired-end reads.

Raw data were filtered by QIIME 2 (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2, version 2019.7) and its plug-ins [55]. The operational taxonomic unit (OTU) was subjected to the removal of low-quality reads and noises with DADA2 [56], and resulting amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were taxonomically classified by comparing with the Silva database using the q2-feature-classifier [57]. Resampling of 38,309 reads per sample was performed for Alpha diversity analysis. Specific packages in R version 3.6.3 were used for statistical analyses based on the feature table.

Statistical analysis

The AWCD values, microbial abundance, and α-diversity data were all subject to the analysis of variance (ANOVA). Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) was tested at the 5% level (SPSS version 26.0). Principal component analysis of the Biolog data (AWCD) was carried out using Origin 2019b. Effects of different farming practices on bacterial communities and carbon utilization were analyzed using the ComplexHeatmap package in R (version 4.3.1).

The α-diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, and Pielou index) were derived from the ASV data by using Vegan packages in R version 4.3.1, with the β-diversity generated using the Vegan package in R. Principal co-ordinate analysis was based on the Bray-Curtis distance [58].

Bacterial ASVs with an average relative abundance of less than 0.01% were removed from the ASV table. The computation of the pairwise similarity matrix was based on Spearman correlation with P-value adjusted using the BH method. The igraph package was used to calculate topological features of co-occurrence networks [59], including the number of edges and nodes, positive and negative edges, network density, average degree and path length, network diameter, clustering coefficients, betweenness centralization, and modularity, which were illustrated using the Gephi software (0.10.1).

Results

Bacterial richness, diversity, and community composition under different agricultural management practices in citrus orchards

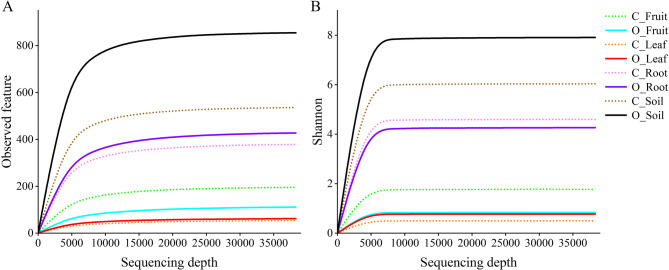

The rarefaction curve gradually leveled off and the number of ASVs reached its peak level with the increase of sequencing depth, together with the gradually stabilized Shannon index curve (Fig. 1), indicating reliable sampling, sufficient sequencing, and reasonable sample size to represent the bacterial communities for diversity analysis in this study. Aboveground (fruit and leaf) bacterial communities had lower levels of diversity compared to belowground (root and soil) communities (Fig. 1 A).

Fig. 1.

Rarefaction curves of observed species (i.e., ASVs) were derived from clustering at the 97% similarity level based on the 16 S rRNA gene sequences of all different ecological niche samples from organic farming and conventional farming. (A) Species Rarefaction curve. (B) Shannon curves. Conventional farming (C), Organic farming (O)

The Chao1 and Ace indices represent the richness of the bacterial community, Shannon and Simpson’s indices indicate the bacterial diversity, and the Pielou’s Evenness index measures bacterial community evenness [60, 61]. The α-diversity indices of bacterial communities significantly differed (P < 0.05) under conventional and organic farming. The soil bacterial community under organic farming (O_Soil) exhibited higher richness, diversity, and evenness compared to other microbial communities. Specifically, the Shannon index of C_Fruit, O_Fruit, C_Leaf, O_Leaf, C_Root, O_Root, and C_Soil was 77.55%, 89.42%, 93.61%, 90.33%, 41.79%, 45.99%, and 23.54% lower than O_Soil, respectively (Table 2). The Shannon and Pielou’s Evenness indices were significantly different between soil (or fruit) samples under conventional and organic farming, while not between root (or leaf) samples. Notably, there were significant changes in microbial diversity (except the Simpson’s index) across ecological niches under conventional farming, while not between leaf and fruit microbial diversity under organic farming. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) indicated that microbial communities were well separated by agricultural management practices or ecological niches when comparing all samples (Fig. 2). The microbial community in leaf samples was more similar to that in fruit samples, therefore most samples clustered together. Root microbiomes were also different depending on agricultural management practices.

Table 2.

Bacterial community richness and diversity indices under different agricultural management practices and ecological niches. Conventional farming (C), organic farming (O)

| Treatment | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson | Pielou |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C_Fruit | 197.67 ± 56.81 d | 1.23 ± 0.22 d | 0.39 ± 0.08 c | 0.16 ± 0.03 d |

| O_Fruit | 114.11 ± 31.71 de | 0.58 ± 0.27 e | 0.19 ± 0.11 d | 0.08 ± 0.03 e |

| C_Leaf | 55.33 ± 46.63 e | 0.35 ± 0.21 e | 0.12 ± 0.06 d | 0.06 ± 0.02 e |

| O_Leaf | 63.22 ± 40.01 e | 0.53 ± 0.28 e | 0.19 ± 0.10 d | 0.09 ± 0.04 e |

| C_Root | 381.33 ± 68.98 c | 3.19 ± 0.73 c | 0.82 ± 0.13 b | 0.37 ± 0.08 c |

| O_Root | 430.00 ± 99.56 c | 2.96 ± 0.61 c | 0.74 ± 0.05 b | 0.34 ± 0.06 c |

| C_Soil | 537.20 ± 152.65 b | 4.19 ± 0.73 b | 0.90 ± 0.05 ab | 0.46 ± 0.06 b |

| O_Soil | 856.80 ± 136.94 a | 5.48 ± 0.33 a | 0.98 ± 0.01 a | 0.56 ± 0.02 a |

Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between organic and conventional agricultural practices using the LSD test (P < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

The PCoA analysis of microbial species among the total samples (9 replicates for the fruit, leaf, and root samples and 5 replicates for the soil samples). Unconstrained PCoA (for principal coordinates PCoA1 and PCoA2) with Bray-Curtis distance showing separation of the microbiota of different ecological niches in the first axis. Each point in the figure represents a sample, and samples from the same group are represented by the same color and shape

Variations in the bacterial community structure under different agricultural management practices

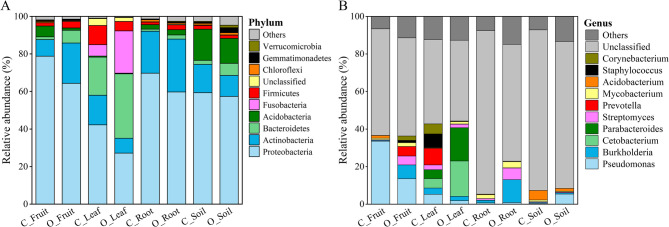

The bacterial community composition in ecological niches in citrus orchards was analyzed under different agricultural management practices (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). The dominant phylum included Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Fusobacteria. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly lower under organic farming compared to conventional farming, while Bacteroidetes were more abundant under organic farming. Organic farming led to abundant Proteobacteria (relative abundance = 27.17%) in the leaf, and Proteobacteria even showed higher levels of abundance in other ecological niches (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Relative abundance of bacterial communities under different agricultural management practices at the phylum (A) and genus (B) level. Conventional farming (C), Organic farming (O)

The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes (34.36%) and Fusobacteria (22.53%) was also significantly higher in the leaf under organic farming as compared to the other samples. In the soil under organic farming, there were significantly more abundant Acidobacteria (13.33%), Gemmatimonadetes (2.63%), and Verrucomicrobia (1.34%), as compared to the endosphere compartments. However, the relative abundance of Acidobacteria and Chloroflexi was significantly higher in soil and root samples under conventional farming compared to the other samples (Fig. 3 A).

At the genus level, the community composition of fruit, leaf, root, and soil microbiomes under organic farming was significantly different from that under conventional farming considering the top 10 bacteria (Fig. 3B). The relative abundance of Pseudomonas, Acidobacterium, and Mycobacterium was higher in the fruit under conventional farming. Parabacteroides, Burkholderia, and Prevotella had higher relative abundance in fruit tissues under organic farming. Prevotella, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium showed higher relative abundance in the leaf under conventional farming. Cetobacterium, Parabacteroides, and Burkholderia had higher relative abundance in leaf tissues under organic farming. Burkholderia, Streptomyces, and Mycobacterium had higher relative abundance in root tissues under both conventional and organic farming. In particular, relative abundance of Burkholderia under organic farming increased up to 12.22% compared to 1.42% under conventional farming. For soil samples, the major genera were Acidobacterium and Mycobacterium under conventional farming, with Pseudomonas as the staple genus under organic farming.

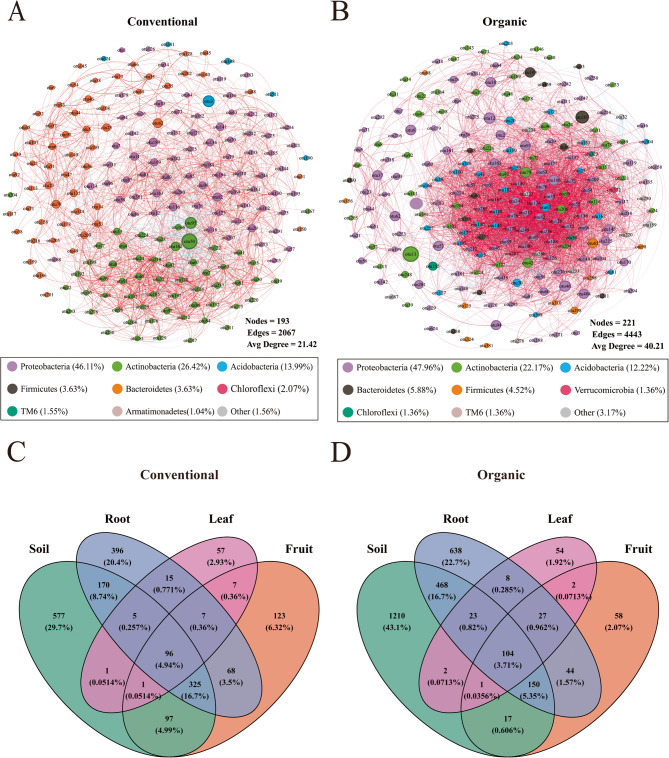

Core microbial community characteristics

The taxonomic characteristics of bacterial communities in the conventional and organic orchards were investigated using co-occurrence analysis (Fig. 4). Bacterial communities had significant associations with farming practices (Table 2); however, they showed very different phylum abundance and structural variations. High-abundance nodes in the co-occurrence network were mostly related to eight distinct phyla. Proteobacteria (46.11%), Actinobacteria (26.42%), Acidobacteria (13.99%), Firmicutes (3.63%), Bacteroidetes (3.63%), Chloroflexi (2.07%), TM6 (1.55%), and Armatimonadetes (1.04%) represented the most dominant bacterial community under conventional farming (Fig. 4 A). While, for organic farming, Proteobacteria (47.96%), Actinobacteria (22.17%), Acidobacteria (12.22%), Bacteroidetes (5.88%), Firmicutes (4.52%), Verrucomicrobia (1.36%), Chloroflexi (1.36%), and TM6 (1.36%) were the most dominant bacterial phyla (Fig. 4B). Meanwhile, topological characteristics were computed to quantify the between-node correlation (Supplementary Table 2), indicating higher complexity and connectivity under organic farming compared to conventional farming. The organic ASV association network consisted of 221 nodes and 4443 edges in comparison with 193 nodes and 2067 edges for conventional farming. The network of organic farming showed more connections per node (average degree = 40.21) as compared to that of conventional farming (21.42), indicating high levels of interconnectivity within the microbial community under organic farming (Supplementary Table 2). The positive edges of the conventional and organic farming networks accounted for 93.37% and 96.89%, respectively, suggesting that symbiotic relationships predominated among the indicator microbial networks under different farming practices. Overall, the bacterial network showed higher levels of complexity and interconnection under organic farming compared to that under conventional farming.

Fig. 4.

Co-occurrence network diagram (P < 0.05) of bacterial communities under conventional (A) and organic (B) farming. Positive and negative correlations are displayed in red and blue, respectively. The nodes are colored according to different types of phylum levels. The size of each node is proportional to the betweenness centrality. Venn diagram showing the ASVs of conventional (C) and organic (D) farming samples

As shown in the Venn diagram (Fig. 4C-D), for the common ASVs shared by all ecological niches, 104 were from organic farming and 96 from conventional farming. O_Soil, O_Root, and O_Leaf had 703, 380, and 32 more ASVs, respectively, compared to C_Soil, C_Root and C_Leaf although C_Fruit had 321 more ASVs than O_Fruit, suggesting generally more ASVs under organic farming.

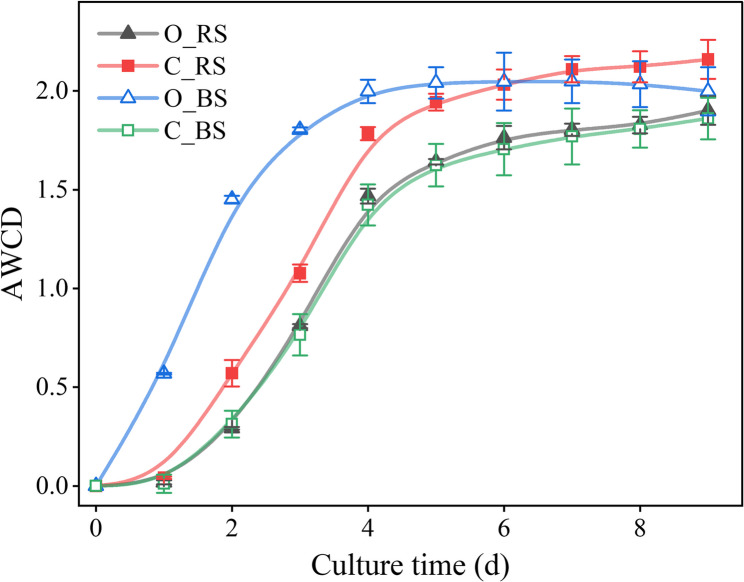

Characterization of the functional diversity of soil microbiomes

The carbon utilization abilities of soil microbiomes gradually increased in all treatments over the 9-day culture period, and the overall trend followed the S-curve of bacterial growth (Fig. 5). The capacity of soil microbiomes to utilize carbon sources was lower in C_BS compared to other treatments. The AWCD value of O_BS was significantly higher than all other treatments until the 6th day and appeared lower than C_RS from the 7th day (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Changes in average well color development (AWCD) over time of the bulk and rhizosphere soil under different agricultural management in a long-term experiment. Conventional farming (C), Organic farming (O), rhizosphere soil (RS), Bulk soil (BS). Mean value with standard error, n = 3

After 3-day culture, utilization of six types of carbon sources by the bulk or rhizosphere soil microbiomes from long-term conventional or organic citrus farming was quantified (Table 3). The highest utilization abilities were observed in the O_BS treatment and carboxylic acid was the mostly utilized carbon source in the bulk soil treatment under two different farming practices. The rhizosphere soil microbiome utilized the carbon source differently, with amino acid and amine being efficiently metabolized in the O_RS and C_RS treatment, respectively (Table 3). The AWCD data on day 3 during the log period were selected to analyze functional diversity of the soil microbiomes (Table 4). The functional diversity indices (Shannon-Weiner, Simpson, and Richness index) of the O_BS microbiome were significantly higher than the others, except for the Pielou Evenness index. The diversity indices of bulk or rhizosphere soil microbiomes from organic farming were higher than those from conventional farming, except for the Richness or Simpson index of the rhizosphere soil microbiome. For the same farming practice, significant differences were found between bulk and rhizosphere soil microbiomes in organic farming, except for the Pielou Evenness index. No significant differences were found between bulk and rhizosphere soil samples under conventional farming, except for the richness index.

Table 3.

The utilization of six types of carbon sources by microorganisms (based on the third day data from biolog data) under different long-term farming management. Conventional farming (C), organic farming (O), rhizosphere soil (RS), bulk soil (BS)

| Treatment | Polymer | Carbohydrates | Phenolic acids | Carboxylic acids | Amino acids | Amine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O_RS | 0.87 ± 0.13 b | 0.86 ± 0.02 c | 0.51 ± 0.10 c | 0.79 ± 0.15 c | 0.90 ± 0.20 b | 0.53 ± 0.22 b |

| C_RS | 0.92 ± 0.07 b | 1.23 ± 0.05 b | 0.99 ± 0.05 b | 1.05 ± 0.06 b | 0.88 ± 0.03 b | 1.36 ± 0.03 a |

| O_BS | 1.80 ± 0.13 a | 1.78 ± 0.14 a | 1.85 ± 0.14 a | 1.95 ± 0.18 a | 1.76 ± 0.11 a | 1.53 ± 0.20 a |

| C_BS | 0.80 ± 0.09 b | 0.65 ± 0.06 d | 0.62 ± 0.11 bc | 1.00 ± 0.07 bc | 0.75 ± 0.16 b | 0.66 ± 0.04 b |

Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between organic and conventional agricultural practices using the LSD test (P < 0.05)

Table 4.

Functional diversity indices of the microbial community (based on the third day data from biolog analysis) under different long-term farming management. Conventional farming (C), organic farming (O), rhizosphere soil (RS), bulk soil (BS)

| Treatment | Richness Index | Simpson Index | Shannon-Weiner Index | Pielou Evenness Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O_RS | 23 ± 1.15 d | 0.95 ± 0.01 b | 4.4 ± 0.09 b | 1.41 ± 0.01 a |

| C_RS | 26 ± 1.00 c | 0.95 ± 0.01 b | 4.43 ± 0.02 b | 1.36 ± 0.01 b |

| O_BS | 31 ± 0.58 a | 0.96 ± 0.01 a | 4.8 ± 0.04 a | 1.4 ± 0.00 a |

| C_BS | 28 ± 0.58 b | 0.95 ± 0.01 b | 4.54 ± 0.05 b | 1.37 ± 0.01 b |

Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between organic and conventional agricultural practices using the LSD test (P < 0.05)

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed obvious differences in the patterns of carbon source utilization by bulk or rhizosphere soil microbiomes under different farming practices (Fig. 6). PC1 and PC2 contributed to 69.44% and 21.23% of the total variation, respectively. Along the PC1 axis, treatments were categorized into two clusters according to microbial utilization of carbon sources, with O_BS as one cluster and O_RS, C_RS, and C_BS forming the other cluster (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of bulk and rhizosphere soil microbial communities under different long-term farming management in terms of carbon metabolism based on the third day Biolog data

Metabolic capacity of soil microbiomes in carbon source utilization

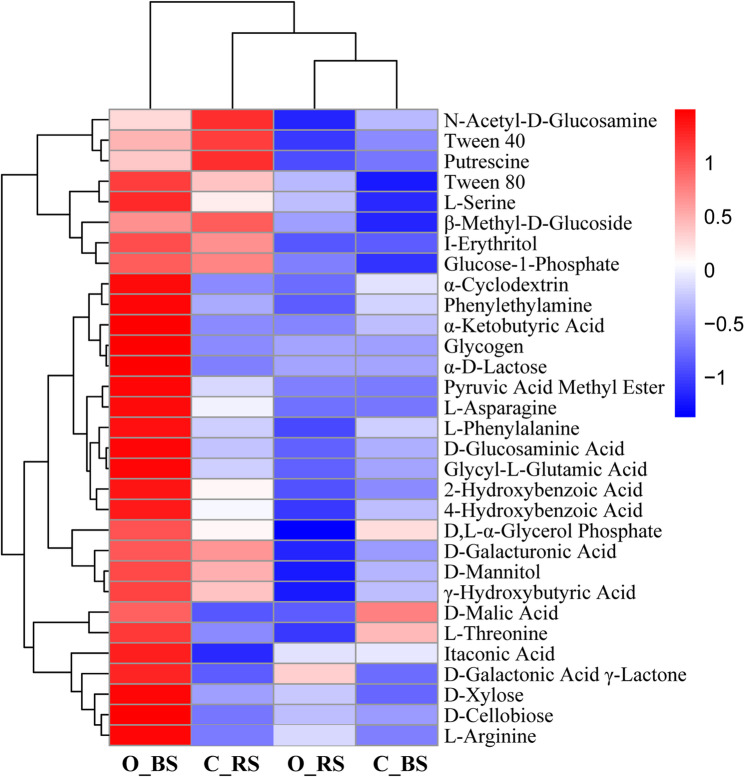

Based on the 3rd day AWCD values after incubation, hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to compare utilization capacities of 31 carbon sources by the bulk and rhizosphere soil microbiomes (Fig. 7) and showed obvious cross-treatment differences. For vertical clustering, the heatmap displayed two distinct clusters: cluster 1 with O_BS and cluster 2 with C_RS, O_RS, and C_BS. Cluster 2 could be further divided into subgroup 1 with C_RS and subgroup 2 with O_RS and C_BS. As to horizontal clustering, most carbon sources were more efficiently utilized in the O_BS treatment, while four carbon sources (N-Acetyl-D-Glucosamine, Tween 40, Putrescine, and β-Methyl-D-Glucoside) were efficiently utilized in the C_RS treatment. Both O_RS and C_BS had lower carbon utilization capacities compared to O_BS and C_RS, except for efficient utilization of D-Galactonic Acid γ-Lactone by O_RS and active metabolism of D-Malic Acid and L-Threonine by C_BS.

Fig. 7.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of the carbon metabolic intensity of bulk and rhizosphere soil microbial communities under different long-term farming management

Discussion

Effects of different agricultural management practices on the diversity and composition of microbial communities

Agricultural management practices play a pivotal role in conditioning microbiome assembly in different ecological niches [62]. Our study suggests that microbial assembly is largely influenced by both farming practices and ecological niches. Consistent with grape, citrus, and maize-wheat/barley rotation system studies [44, 63–65], our results showed higher microbial diversity in belowground (root and soil) samples than in aboveground (leaf and fruit) samples (Fig. 1; Table 2). This disparity can be attributed to the dynamic and heterogeneous aboveground environment, highly selective oligotrophic conditions, and high exposure to various biotic (e.g., pollinator and pathogen infection) and abiotic (e.g., sunshine, precipitation) stimuli, as well as anthropogenic pressures (e.g., farming management) imposed on aboveground parts of the plant [66]. The study on source tracing has shown that crop microbiomes mainly come from the soil and are progressively enriched and filtered in different plant ecological niches; the host selection effect may explain lower leaf and fruit bacterial diversity [65]. Diversity analyses revealed that farming management and ecological niches significantly affect the diversity and composition of the microbiota (Fig. 2; Table 2). Organic farming resulted in slightly higher diversity (α-diversity index) than conventional farming, especially in the soil (Table 2), consistent with previous reports [12, 67]. This can be attributed to increases in soil organic matter, enhanced soil health, greater soil biodiversity, and minimization of agrochemical inputs in organic farming [27, 68–71]. Moreover, conventional farming showed significant changes in microbial diversity across different ecological niches. In contrast, no significant differences between leaf and fruit microbial diversity were observed under organic farming (Table 2). In this regard, the higher diversity and lower dispersion in organic farming may suggest that the soil and leaf microbiota under organic farming are more resilient to environmental stresses, benefiting from the complementary interactions among different taxa [35]. Mineral fertilization enhances nutrient absorption by fruits, however, excessive nitrogen application can increase the disease severity, coupled with fungicide application in agricultural production [72]. High nutrient levels and disease pressures result in greater microbial diversity in fruit under conventional farming [34]. However, more studies are needed to solidify this argument. Furthermore, farming practices had more pronounced effects on bacterial diversity in the soil compared to other plant niches (Table 2). These results indicate that microbial communities in the soil are more sensitive to farming management, whereas microbiota in the leaf and fruit remain relatively stable, possibly due to the strong selection pressure from the host plant and the fact that the main drivers of the separation of endophytic microbial communities are niche factors [65]. Considerable variations in the root microbiome under conventional farming are probably related to high levels of agrochemical inputs [73].

In agreement with previous results [42], we found that Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Firmicutes were the most abundant bacterial phyla in the citrus orchard (Fig. 3). In the rhizosphere, root exudates serve as signaling molecules and nutrient sources, selectively recruiting microbes from bulk soil and strongly affecting the composition of surrounding soil microbiomes [74]. We observed the enrichment of the bacterial phyla Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria in the root compared to bulk soils, whereas Bacteroidetes and Acidobacteria were depleted (Fig. 3A). This contrasts with other findings [42, 75], probably due to crop developmental progression, seasonal variations, and agriculture management practices. Moreover, under organic farming, a substantial decrease in Acidobacteria and Chlorofexi abundance was observed in the leaf and fruit, whereas Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were enriched in fruit and root compartments. Bacteroidetes were also enriched in the citrus leaf under organic farming (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Table 1), consistent with previous studies [76–78]. Such compositional diversity most likely results from the decreasing abundance of slow-growing and oligotrophic bacteria (K-strategists), such as Acidobacteria and Chlorofexi, and the increasing dominance of fast-growing and copiotrophic bacteria (r-strategists), such as Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria [79]. Consistent with other studies [37, 47], our results suggest that organic farming leads to the depletion of K-strategists and the enrichment of fast-growing microorganisms.

Organic farming increases the abundance of beneficial microbes while suppressing pathogen growth [36, 40, 80], well supporting our findings in this study. For instance, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria (Fig. 3 A) are the most dominant phyla in the citrus microbiome [77, 78, 81, 82]. Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria are positively correlated with environmental factors, soil properties and crop quality [83]. Higher levels of soil carbon under organic farming favor Proteobacteria proliferation for fornitrogen fixation and phosphorus solubilization [84]. Abundant Actinobacteria help safeguard plant health and promote crop growth by producing antibiotics and cell wall-degrading enzymes or parasitizing pathogenic microbes for disease suppression [85]. The core genera from these phyla, including Burkholderia and Streptomyces, were more abundant in the root and fruit under organic farming (Fig. 3B), and some are potentially beneficial microbes [42, 47]. Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Sphingomonas, and Bacillus have been identified as agents capable of inhibiting plant diseases in different contexts [81, 86–88]. Pseudomonas enrichment in the organic soil relative to the conventional soil possibly make the organic orchard more disease resistant. Similarly, Pseudomonas was also enriched in the fruit microbiome under conventional farming (Fig. 3), implying an adaption strategy to cope with the disease stressed condition under conventional farming although further investigation is required.

Organic farming leads to higher microbial network stability

Microorganisms form intricate networks through multi-level associations; stable microbial networks tend to be pathogen-suppressive and show greater resistance to climate change and biodiversity loss [89], which favors plant health, improves soil fertility, and reduces application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, providing novel strategies for sustainable agricultural management [90–93]. Microbial co-occurrence networks of both farming practices exhibited distinct patterns of microbe-microbe connectivity and structure (Fig. 4A–B), indicating the significance of particular microbial nodes in organic and conventional farming systems [91]. Our study highlights the significant impact of agricultural management on microbiota network structures, with a significantly more complex network under organic farming compared to conventional farming. According to network topology analysis (Supplementary Table 2), organic networks had more edges, nodes, degrees, and connectivity, consistent with other studies based on different agricultural systems [12, 35, 36, 94]. Complex networks with higher stability are more resistant to environmental stresses or invasion by exogenous microorganisms than simple networks with relatively low connectivity [95, 96]. In these co-occurrence networks, certain highly related taxa are considered as plant-associated microorganisms, and they could indeed play an important role in the plant microbiota [91]. Contrary to conventional farming, higher complexity and connectivity in the organic network are associated with more hub taxa identified [12]. Similar to the study in wheat [36], the high complexity within the organic network (Fig. 4 A and B) suggests that the microbiome under organic farming may be more resilient to environmental perturbations due to complementary interactions among the different taxa. However, further investigation is necessary to better understand underlying mechanisms, and the long-term outcomes remain to be further explored.

The core microbiome, often defined as an essential set of microbes common in different microbial consortia from similar habitats, is crucial for understanding the composition, functions, and stability of complex microbial assemblages [97, 98]. The predominant taxa of the global rhizosphere microbiome in citrus orchards include Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Bacteroidetes [42]. Some of these core microorganisms are more abundant under organic farming (Figs. 3 and 4A-B) and function redundantly for nitrogen fixation; such functional redundancy is important for the recovery and stability of microbial communities [97].

Impacts of farming practices on carbon source utilization by microbial communities

The Biolog Eco-Plate method is an efficient way to assess the physiological properties of microbial communities, especially in bulk and rhizosphere soils [99, 100]. The AWCD value, which represents soil microbial ability to utilize different carbon sources, serves as a vital index of microbial functional diversity [101]. Our results revealed significant effects of farming practices on the carbon utilization patterns of the bulk and rhizosphere soil microbial communities (Figs. 6 and 7; Table 3). Moreover, soil microorganisms were able to proliferate with high biodiversity under organic farming (Table 4). The results were supported by our 16 s DNA sequencing showing that the organic farming system has more abundant and diverse soil microorganisms than the conventional farming counterpart. Similar trends have been observed in apple [61], banana [102], grape [103], and wheat [40] systems under diverse agricultural management practices.

Microbial communities utilized six types of carbon sources in a distinct manner within and between farming practices (Table 3), probably attributed to the presence of different functional groups [104]. Efficient utilization of carbohydrates, amino acids, and carboxylic acids in O_BS suggests that organic farming may have provided more simple sugars compared to conventional farming. According to previous studies [105], rapidly multiplied microorganisms are selected under uncrowded environmental conditions with easily accessible and rich nutrients (r-strategists). This might contribute to more diverse fast-growing heterotrophs in organic farming soils [102].

Notably, the distribution of microorganisms in bulk soils appears more homogeneous under organic farming [31]. Higher Simpson, Shannon-Weiner, and Pielou Evenness indices of organic bulk soil indicate greater richness and abundance of microbial species under organic farming [50, 106]. Such rich and abundant microorganisms show greater capabilities to utilize carbon substrates as suggested by the higher Richness index [53]. The rhizosphere soil under organic farming exhibits lower microbial richness and higher microbial evenness compared to that under conventional farming (Table 4), possibly due to competitive interactions between root and soil microbes under organic farming. Plants tend to release certain volatiles that may restrict proliferation of microbial populations under organic farming [107–109]. Biolog analysis showed separation of the O_RS microbiome from other communities (Fig. 7), suggesting greater influence of organic farming on microbial functionality than conventional farming. Changes in the diversity, composition, and functions of soil bacterial communities may be partially attributed to higher soil organic matter content and reasonable pH [60, 110–112].

Conclusion

The organic farming orchard accommodated a more diverse microbial community than the conventional orchard. The relative abundance of Acidobacteria and Chlorofexi decreased significantly in the soil and fruit samples of the organic farming. However, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were enriched in fruit and root compartments, indicating depletion of K-strategists and enrichment of r-strategists under organic farming. Meanwhile, relative abundance of Burkholderia and Streptomyces significantly increased under organic farming, indicating preferential colonization of potentially beneficial microbes. Moreover, the greater complexity and connectivity of the organic network imply that organic farming not only affects the abundance of specific taxa but also shapes interactions within the microbial community. Together, organic farming favorably alters microbial communities and the functional diversity in the citrus orchard. It is also particularly important to explore the long-term effects of organic farming on microbial communities. Synthetic microbial communities derived from organic orchards hold great promise for more efficient and sustainable orchard management.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- C

Conventional farming

- O

Organic farming

- RS

Rhizosphere soil

- BS

Bulk soil

- OTU

The operational taxonomic unit

- ASV

Amplicon sequence variants

- AWCD

The average well color development

Authors’ contributions

Li X.X., and Liu L.L. designed the study. Liu L.L., Zhong Y.T., and He B.Y. completed the experiment. Liu L.L., and Zhong Y.T. analyzed the data and prepared all figures. Liu L.L., and M. A.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Li X.X., and M. A.M. contributed to the interpretation of the results, the writing, and the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

(2021YFD1901100).

Data availability

The DNA sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [NCBI] repository, [BioProject PRJNA1155806].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pretty J. Agricultural sustainability: concepts, principles and evidence. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2007;363(1491):447–65. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui ZL, Zhang HY, Chen XP, Zhang CC, Ma WQ, Huang CD, et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature. 2018;555(7696):363–66. 10.1038/nature25785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renard D, Tilman D. National food production stabilized by crop diversity. Nature. 2019;571(7764):257–60. 10.1038/s41586-019-1316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang XZ, Dou ZX, Shi XJ, Zou CQ, Liu DY, Wang ZY, et al. Innovative management programme reduces environmental impacts in Chinese vegetable production. Nat Food. 2021;2(1):47–53. 10.1038/s43016-020-00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Lubchenco J, Melillo JM. Human domination of earth’s ecosystems. Science. 1997;277(5325):494–99. 10.1126/science.277.5325.494. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimentel D, Harvey C, Resosudarmo P, Sinclair K, Kurz D, Mcnair M, Crist S, Shpritz L, Fitton L, Saffouri R, Blair R. Environmental and economic costs of soil erosion and conservation benefits. Science. 1995;267(5201):1117–23. 10.1126/science.267.5201.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo JH, Liu XJ, Zhang Y, Shen JL, Han WX, Zhang WF, Christie P, Goulding KWT, Vitousek PM, Zhang FS. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science. 2010;327(5968):1008–10. 10.1126/science.1182570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu XJ, Zhang Y, Han WX, Tang AH, Shen JL, Cui ZL, Vitousek P, Erisman JW, Goulding K, Christie P, Fangmeier A, Zhang FS. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature. 2013;494(7438):459–62. 10.1038/nature11917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raza S, Miao N, Wang P, Ju X, Chen Z, Zhou J, Kuzyakov Y. Dramatic loss of inorganic carbon by nitrogen-induced soil acidification in Chinese croplands. Glob Chang Biol. 2020;26(6):3738–51. 10.1111/gcb.15101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pimentel D, Hepperly P, Hanson J, Seidel R, Douds D. Organic and conventional farming systems: environmental and economic issues. The Rodale Institute: Kutztown, PA, USA. 2005. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/2101

- 11.Rivera SXC, Bacenetti J, Fusi A, Niero M. The influence of fertiliser and pesticide emissions model on life cycle assessment of agricultural products: the case of Danish and Italian barley. Sci Total Environ. 2017;592:745–57. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoiri AN, Cheevadhanarak S, Jirakkakul J, Dulsawat S, Prommeenate P, Tachaleat A, Kusonmano K, Wattanachaisaereekul S, Sutheeworapong S. Comparative metagenomics reveals microbial signatures of sugarcane phyllosphere in organic management. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:623799. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.623799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lori M, Symnaczik S, Mäder P, Deyn GD, Gattinger A. Organic farming enhances soil microbial abundance and activity–a meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180442. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyhorn F, Muller A, Reganold JP, Frison E, Herren HR, Luttikholt L, Mueller A, Sanders J, Scialabba NE-H, Seufert V, Smith P. Sustainability in global agriculture driven by organic farming. Nat Sustain. 2019;2(4):253–55. 10.1038/s41893-019-0266-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonthier DJ, Ennis KK, Farinas S, Hsieh HY, Iverson AL, Batáry P, Rudolphi J, Tscharntke T, Cardinale BJ, Perfecto I. Biodiversity conservation in agriculture requires a multi-scale approach. Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281(1791): 20141358. 10.1098/rspb.2014.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dick RP. A review: long-term effects of agricultural systems on soil biochemical and microbial parameters. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1992;40(1–4):25–36. 10.1016/0167-8809(92)90081-L. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tscharntke T, Grass I, Wanger TC, Westphal C, Batáry P. Beyond organic farming–harnessing biodiversity-friendly landscapes. Trends Ecol Evol. 2021;36(10):919–30. 10.1016/j.tree.2021.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meemken EM, Qaim M. Organic, agriculture. Food security, and the environment. Annu Rev Resour Econ. 2018;10(1):39–63. 10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023252. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reganold JP, Wachter JM. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants. 2016;2(2): 15221. 10.1038/nplants.2015.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowder DW, Reganold JP. Financial competitiveness of organic agriculture on a global scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(24):7611–6. 10.1073/pnas.1423674112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause HM, Mder P, Fliessbach A, Jarosch KA, Oberson A, Jochen M. Organic cropping systems balance environmental impacts and agricultural production. Sci Rep. 2024;14:25537. 10.1038/s41598-024-76776-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castaneda LE, Miura T, Sanchez R, Barbosa O. Effects of agricultural management on phyllosphere fungal diversity in vineyards and the association with adjacent native forests. PeerJ. 2018;6: e5715. 10.7717/peerj.5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeder P, Fliessbach A, Dubois D, Gunst L, Fried P, Niggli U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science. 2002;296(5573):1694–97. 10.1126/science.1071148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pimentel D, Hepperly P, Hanson J, Douds D, Seidel R, Environmental. Energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. Bioscience. 2005;55(7):573–82. 10.1641/0006-3568(2005. )055[0573:Eeaeco]2.0.Co;2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiang YZ, Chang SX, Shen YY, Chen G, Liu Y, Yao B, Xue JM, Li Y. Grass cover increases soil microbial abundance and diversity and extracellular enzyme activities in orchards: a synthesis across China. Appl Soil Ecol. 2023;182: 104720. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104720. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedel JK, Gabel D, Stahr K. Nitrogen pools and turnover in arable soils under different durations of organic farming: II: Source-and-sink function of the soil microbial biomass or competition with growing plants? J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2001;164(4):421–9. 10.1002/1522-2624(200108)164:4%3C;421::Aid-jpln421%3E;3.0.Co;2-p. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Rijssel SQ, (Ciska) Veen GF, Koorneef GJ, (Tanja) Bakx-Schotman JMT, Ten Hoove FC, Geisen S. Soil microbial diversity and community composition during conversion from conventional to organic agriculture. Mol Ecol. 2022;31(15):4017–30. 10.1111/mec.16571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos VB, Araújo ASF, Leite LFC, Nunes LAPL, Melo WJ. Soil microbial biomass and organic matter fractions during transition from conventional to organic farming systems. Geoderma. 2012;170:227–31. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.11.007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fließbach A, Mäder P. Microbial biomass and size-density fractions differ between soils of organic and conventional agricultural systems. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32(6):757–68. 10.1016/s0038-0717(99)00197-2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosling P, Hodge A, Goodlass G, Bending GD. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and organic farming. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2006;113(1–4):17–35. 10.1016/j.agee.2005.09.009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bei Q, Reitz T, Schnabel B, Eisenhauer N, Schadler M, Buscot F, Heintz-Buschart A. Extreme summers impact cropland and grassland soil microbiomes. ISME J. 2023;17(10):1589–600. 10.1038/s41396-023-01470-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lupatini M, Korthals GW, de Hollander M, Janssens TK, Kuramae EE. Soil Microbiome is more heterogeneous in organic than in conventional farming system. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:2064. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartman K, Van der Heijden MGA, Wittwer RA, Banerjee S, Walser JC, Schlaeppi K. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome. 2018;6(1): 14. 10.1186/s40168-017-0389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leff JW, Fierer N. Bacterial communities associated with the surfaces of fresh fruits and vegetables. PLoS One. 2013;8(3): e59310. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartmann M, Frey B, Mayer J, Mader P, Widmer F. Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. ISME J. 2015;9(5):1177–94. 10.1038/ismej.2014.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee S, Walder F, Buchi L, Meyer M, Held AY, Gattinger A, Keller T, Charles R, Van der Heijden MGA. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. ISME J. 2019;13(7):1722–36. 10.1038/s41396-019-0383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo J, Banerjee S, Ma Q, Liao G, Hu B, Zhao H, Li T. Organic fertilization drives shifts in microbiome complexity and keystone taxa increase the resistance of microbial mediated functions to biodiversity loss. Biol Fertil Soils. 2023;59(4):441–58. 10.1007/s00374-023-01719-3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blundell R, Schmidt JE, Igwe A, Cheung AL, Vannette RL, Gaudin ACM, Casteel CL. Organic management promotes natural pest control through altered plant resistance to insects. Nat Plants. 2020;6(5):483–91. 10.1038/s41477-020-0656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ottesen AR, White JR, Skaltsas DN, Newell MJ, Walsh CS. Impact of organic and conventional management on the phyllosphere microbial ecology of an apple crop. J Food Prot. 2009;72(11):2321–5. 10.4315/0362-028x-72.11.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlsson I, Friberg H, Kolseth AK, Steinberg C, Persson P. Organic farming increases richness of fungal taxa in the wheat phyllosphere. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(13):3424–36. 10.1111/mec.14132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang N. The citrus Huanglongbing crisis and potential solutions. Mol Plant. 2019;12(5):607–9. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Zhang Y, Zhang P, Trivedi P, Riera N, Wang Y, et al. The structure and function of the global citrus rhizosphere microbiome. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4894. 10.1038/s41467-018-07343-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Sun X, Zhou J, Zhang H, Yang C. Linear and nonlinear multivariate regressions for determination sugar content of intact Gannan navel orange by Vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Math Comput Model. 2010;51(11–12):1438–43. 10.1016/j.mcm.2009.10.003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y, Tang Y, Hu C, Zhan T, Zhang S, Cai M, Zhao X. Soil applied Ca, Mg and B altered phyllosphere and rhizosphere bacterial microbiome and reduced Huanglongbing incidence in Gannan navel orange. Sci Total Environ. 2021;791: 148046. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo CX, Pan ZY, Peng S. Effect of Biochar on the growth of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) raf. Seedlings in Gannan acidic red soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2016;62(2):194–200. 10.1080/00380768.2016.1150789. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su JM, Wang YY, Bai M, Peng TH, Li HS, Xu HJ, et al. Soil conditions and the plant Microbiome boost the accumulation of monoterpenes in the fruit of Citrus reticulata ‘chachi’. Microbiome. 2023;11(1):61. 10.1186/s40168-023-01504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bei S, Zhang Y, Li T, Christie P, Li X, Zhang J. Response of the soil microbial community to different fertilizer inputs in a wheat-maize rotation on a calcareous soil. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2018;260:58–69. 10.1016/j.agee.2018.03.014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sala MM, Arrieta JM, Boras JA, Duarte CM, Vaqué D. The impact of ice melting on bacterioplankton in the Arctic Ocean. Polar Biol. 2010;33(12):1683–94. 10.1007/s00300-010-0808-x. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garland JL. Analytical approaches to the characterization of samples of microbial communities using patterns of potential C source utilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28(2):213–21. 10.1016/0038-0717(95)00112-3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C, Zhou T, Zhu L, Du Z, Li B, Wang J, Wang J, Sun Y. Using enzyme activities and soil microbial diversity to understand the effects of fluoxastrobin on microorganisms in fluvo-aquic soil. Sci Total Environ. 2019;666:89–93. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garland JL, Mills AL. Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community-level sole-carbon-source utilization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57(8):2351–9. 10.1128/aem.57.8.2351-2359.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu L, Xiang Z, Wang G, Rafique R, Liu W, Wang C. Changes in soil physicochemical and microbial properties along elevation gradients in two forest soils. Scand J Res. 2016;31(3):242–53. 10.1080/02827581.2015.1125522. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gryta A, Frąc M, Oszust K. The application of the biolog EcoPlate approach in ecotoxicological evaluation of dairy sewage sludge. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;174(4):1434–43. 10.1007/s12010-014-1131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard RW. Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(24):8014–8. 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–7. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–83. 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, Dillon M, Bolyen E, Knight R, Huttley GA, Caporaso JG. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6:90. 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamady M, Lozupone C, Knight R. Fast unifrac: facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and phylochip data. ISME J. 2010;4(1):17–27. 10.1038/ismej.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The Igraph software package for complex network research. Inter J Complex Syst. 2006;1695:1–9. https://igraph.org. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun R, Zhang XX, Guo X, Wang D, Chu H. Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;88:9–18. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu Z, Bai Y, Lv M, Tian G, Zhang X, Li L, Jiang Y, Ge S. Soil fertility, microbial biomass, and microbial functional diversity responses to four years fertilization in an Apple orchard in North China. Hortic Plant J. 2020;6(4):223–30. 10.1016/j.hpj.2020.06.003. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu YG, Xiong C, Wei Z, Chen QL, Ma B, Zhou SY, Tan J, Zhang LM, Cui HL, Duan GL. Impacts of global change on the phyllosphere microbiome. New Phytol. 2022;234(6):1977–86. 10.1111/nph.17928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y, Qu M, Pu X, Lin J, Shu B. Distinct microbial communities among different tissues of citrus tree citrus reticulata cv. chachiensis. Sci Rep. 2020;10: 6068. 10.1038/s41598-020-62991-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miliordos DE, Tsiknia M, Kontoudakis N, Dimopoulou M, Bouyioukos C, Kotseridis Y. Impact of application of abscisic acid, benzothiadiazole and Chitosan on berry quality characteristics and plant associated microbial communities of vitis vinifera L var. Mouhtaro Plants Sustain. 2021;13(11):5802. 10.3390/su13115802. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiong C, Zhu YG, Wang JT, Singh B, Han LL, Shen JP, Li PP, Wang GB, Wu CF, Ge AH, Zhang LM, He JZ. Host selection shapes crop microbiome assembly and network complexity. New Phytol. 2021;229(2):1091–104. 10.1111/nph.16890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu HW, Brettell LE, Singh B. Linking the phyllosphere microbiome to plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(9):841–4. 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Esperschutz J, Gattinger A, Mader P, Schloter M, Fliessbach A. Response of soil microbial biomass and community structures to conventional and organic farming systems under identical crop rotations. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;61(1):26–37. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reeve JR, Hoagland LA, Villalba JJ, Carr PM, Atucha A, Cambardella C, Davis DR, Delate K. Organic farming, soil health, and food quality: considering possible links. Adv Agron. 2016;137:319–67. 10.1016/bs.agron.2015.12.003. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gomiero T, Pimentel D, Paoletti MG. Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: conventional vs. organic agriculture. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2011;30(1–2):95–124. 10.1080/07352689.2011.554355. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bengtsson J, Ahnstrm J, Weibull AC. The effects of organic agriculture on biodiversity and abundance: A Meta-Analysis. J Appl Ecol. 2010;42(2):261–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01005.x. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krause HM, Mder P, Fliessbach A, Jarosch KA, Oberson A, Mayer J, Wei W. Organic cropping systems balance environmental impacts and agricultural production. Sci Reports. 2024;14:25537. 10.1038/s41598-024-76776-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wei W, Yang M, Liu Y, Huang H, Ye C, Zheng J, Guo C, Hao M, He X, Zhu S. Fertilizer N application rate impacts plant-soil feedback in a sanqi production system. Sci Total Environ. 2018;633:796–807. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beckers B, Beeck MOD, Weyens N, Boerjan W, Vangronsveld J. Structural variability and niche differentiation in the rhizosphere and endosphere bacterial microbiome of field-grown Poplar trees. Microbiome. 2017;5:25. 10.1186/s40168-017-0241-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhong Y, Xun W, Wang X, Tian S, Zhang Y, Li D, et al. Root-secreted bitter triterpene modulates the rhizosphere microbiota to improve plant fitness. Nat Plants. 2022;8(8):887–96. 10.1038/s41477-022-01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trivedi P, Leach JE, Tringe SG, Sa T, Singh BK. Plant-microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(11):607–21. 10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blaustein RA, Lorca GL, Meyer JL, Gonzalez CF, Teplitski M. Defining the core citrusleaf- and root-associated microbiota: factors associated with community structureand implications for managing Huanglongbing (citrus greening) disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(11):e00210–17. 10.1128/AEM.00210-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Passera A, Alizadeh H, Azadvar M, Quaglino F, Alizadeh A, Casati P, Bianco PA. Studies of microbiota dynamics reveals association of Candidatus liberibacterAsiaticus infection with citrus (Citrus sinensis) decline in South of lran. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1817. 10.3390/iims19061817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bai Y, Wang J, Jin L, Zhan Z, Guan L, Zheng G, Qiu D, Qiu X. Deciphering bacterial community variation during soil and leaf treatments with biologicals and biofertilizers to control Huanglongbing in citrus trees. J Phytopathol. 2019;167(11–12):686–94. 10.1111/iph.12860. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fierer N, Bradford MA, Jackson RB. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology. 2007;88(6):1354–64. 10.1890/05-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Granado J, Thurig B, Kieffer E, Petrini L, Fliessbach A, Tamm L, Weibel FP, Wyss GS. Culturable fungi of stored “golden delicious” Apple fruits: a one-seasoncomparison study of organic and integrated production systems in Switzerland. Microb Ecol. 2008;56(4):720–32. 10.1007/s00248-008-9391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trivedi P, He Z, Van Nostrand JD, Albrigo G, Zhou J, Wang N. Huanglongbing alters the structure and functional diversity of microbial communities associated with citrus rhizosphere. ISME J. 2012;6(2):363–83. 10.1038/ismej.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Y, Trivedi P, Xu J, Roper MC, Wang N. The citrus microbiome: from structure and function to Microbiome engineering and beyond. Phytobiomes J. 2021;5(3):249–62. 10.1094/pbiomes-11-20-0084-rvw. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chai X, Yang Y, Wang X, Hao P, Wang L, Wu T, Zhang X, Xu X, Han Z, Wang Y. Spatial variation of the soil bacterial community in major Apple producing regionsof China. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;130(4):1294–306. 10.1111/jam.14878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jin YB, Fang Z, Zhou XB. Variation of soil bacterial communities in achronosequence of citrus orchard. Ann Microbiol. 2022;72:21. 10.1186/s13213-022-01681-9. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palaniyandi SA, Yang SH, Zhang LX, Suh JW. Effects of actinobacteria on plantdisease suppression and growth promotion. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(22):9621–36. 10.1007/s00253-013-5206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Riera N, Handique U, Zhang Y, Dewdney MM, Wang N. Characterization of antimicrobial-producing beneficial bacteria isolated from Huanglongbing escape citrus trees. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2415. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang J, Ding Y, Nan J, Yang X, Sun L, Zhao X, Jiang L. Transcriptome sequencing and ITRAQ reveal the detoxification mechanism of Bacillus GJ1, a potential biocontrol agent for Huanglongbing. PLoS One. 2018;13(8): e0200427. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li PD, Zhu ZR, Zhang Y, Xu J, Wang H, Wang Z, Li H. The phyllosphere microbiome shifts toward combating melanose pathogen. Microbiome. 2022;10(1): 56. 10.1186/s40168-022-01234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lynch DH. Soil health and biodiversity is driven by intensity of organic farming in Canada. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2022;6:826486. 10.3389/fsufs.2022.826486. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Agler MT, Ruhe J, Kroll S, Morhenn C, Kim ST, Weigel D, Kemen EM. Microbial hub taxa link host and abiotic factors to plant microbiome variation. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(1):e1002352. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Van der Heijden MG, Hartmann M. Networking in the plant Microbiome. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(2):e1002378. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morrien E, Hannula SE, Snoek LB, Helmsing NR, Zweers H, de Hollander M, et al. Soil networks become more connected and take up more carbon as nature restoration progresses. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14349. 10.1038/ncomms14349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vries FT, Griffiths RI, Bailey M, Craig H, Girlanda M, Gweon HS, et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3033. 10.1038/s41467-018-05516-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zheng CYA, Kong KP, Zhang Y, Yang WH, Wu LQ, Munir MZ, Ji BM, Muneer MA. Differential response of bacterial diversity and community composition to different tree ages of pomelo under red and paddy soils. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:958788. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.958788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Montoya JM, Pimm SL, Sole RV. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature. 2006;442(7100):259–64. 10.1038/nature04927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Santolini M, Barabasi AL. Predicting perturbation patterns from the topology of biological networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(27):6375–83. 10.1073/pnas.1720589115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shade A, Handelsman J. Beyond the Venn diagram: the hunt for a core microbiome. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(1):4–12. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Busby PE, Soman C, Wagner MR, Friesen ML, Kremer J, Bennett A, Morsy M, Eisen JA, Leach JE, Dangl JL. Research priorities for harnessing plant microbiomes in sustainable agriculture. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(3):e2001793. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grayston SJ, Wang S, Campbell CD, Edwards AC. Selective influence of plant species on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30(3):369–78. 10.1016/s0038-0717(97)00124-7. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhao J, Ni T, Li J, Lu Q, Fang Z, Huang Q, Zhang R, Li R, Shen B, Shen Q. Effects of organic–in organic compound fertilizer with reduced chemical fertilizer application on crop yields, soil biological activity and bacterial community structure in rice–wheat cropping system. Appl Soil Ecol. 2016;99:1–12. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.11.006. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feigl V, Ujaczki E, Vaszita E, Molnar M. Influence of red mud on soil microbial communities: application and comprehensive evaluation of the biolog EcoPlate approach as a tool in soil microbiological studies. Sci Total Environ. 2017;595:903–11. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chou YM, Shen FT, Chiang SC, Chang CM. Functional diversity and dominant populations of bacteria in banana plantation soils as influenced by long-term organic and conventional farming. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;110:21–33. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Katayama N, Bouam I, Koshida C, Baba YG. Biodiversity and yield under different land-use types in orchard/vineyard landscapes: a meta-analysis. Biol Conserv. 2019;229:125–33. 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.020. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kumar U, Shahid M, Tripathi R, Mohanty S, Kumar A, Bhattacharyya P, Lal B, Gautam P, Raja R, Panda BB, Jambhulkar NN, Shukla AK, Nayak AK. Variation of functional diversity of soil microbial community in sub-humid tropical rice-rice cropping system under long-term organic and inorganic fertilization. Ecol Indic. 2017;73:536–43. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.10.014. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deleij FAAM, Whipps JM, Lynch JM. The use of colony development for the characterization of bacterial communities in soil and on roots. Microb Ecol. 1994;27(1):81–97. 10.1007/Bf00170116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Garland JL. Analysis and interpretation of community-level physiological profiles in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24(4):289–300. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1997.tb00446.x. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen H, Dong Y, Xu T, Wang Y, Wang H, Duan B. Root order-dependent seasonal dynamics in the carbon and nitrogen chemistry of Poplar fine roots. New for. 2017;48(5):587–607. 10.1007/s11056-017-9587-3. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Just C, Armbruster M, Barkusky D, Baumecker M, Diepolder M, Döring TF, et al. Soil organic carbon sequestration in agricultural long-term field experiments as derived from particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Geoderma. 2023;434:116472. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116472. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Semenov MV, Krasnov GS, Semenov VM, Van Bruggen A. Mineral and organic fertilizers distinctly affect fungal communities in the crop rhizosphere. J Fungi. 2022;8(3): 251. 10.3390/jof8030251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xun W, Zhao J, Xue C, Zhang G, Ran W, Wang B, Shen Q, Zhang R. Significant alteration of soil bacterial communities and organic carbon decomposition by different long-term fertilization management conditions of extremely low‐productivity arable soil in South China. Environ Microbiol. 2015;18(6):1907–17. 10.1111/1462-2920.13098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhou J, Jiang X, Zhou B, Zhao B, Ma M, Guan D, Li J, Chen S, Cao F, Shen D, Qin J. Thirty four years of nitrogen fertilization decreases fungal diversity and alters fungal community composition in black soil in Northeast China. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;95:135–43. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.12.012. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Muneer MA, Hou W, Li J, Huang X, Ur Rehman Kayani M, Cai Y, Yang W, Wu L, Ji B, Zheng C. Soil pH: a key edaphic factor regulating distribution and functions of bacterial community along vertical soil profiles in red soil of pomelo orchard. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22(1): 38. 10.1186/s12866-022-02452-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The DNA sequencing datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [NCBI] repository, [BioProject PRJNA1155806].