Abstract

Background

Understanding the genetic basis of long-distance migration in mammals provides important insights into the evolutionary mechanisms that enable species to adapt to changing environments. Despite its ecological significance, the molecular factors underlying this complex trait remain poorly understood.

Results

Our analyses reveal distinct evolutionary signatures associated with long-distance migration in mammals. Through comparative genomics analyses of representative mammalian genomes, we identified multiple genes under positive selection, exhibiting accelerated evolutionary rates, or showing significant correlation with long-distance migration. These genes are predominantly involved in functions related to memory, sensory perception, and locomotor abilities. Additionally, evidence of convergent evolution was detected in genes associated with key biological processes such as energy metabolism, genomic stability, and stress response.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal novel molecular signatures linked to long-distance migration in mammals, shedding light on the evolutionary adaptations that support this behavior. This study enhances understanding of how genetic changes contribute to complex migratory traits and offers a foundation for future research on mammalian adaptation to environmental challenges.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-12022-w.

Keywords: Migratory mammals, Comparative genomics, Memory, Sensory ability, Convergence

Background

Migration is a cyclical and seasonal biological phenomenon characterized by the movement of animals between multiple locations [1]. From an evolutionary perspective, animals migrate to seek favorable conditions that include better resources for feeding and breeding, while also avoiding adverse environmental factors like intense competition and predation. The study of animal migration is significant, as it contributes to biogeochemical cycles and represents a key strategy for adapting to environmental changes [2]. Exploring adaptive evolution mechanisms in migratory species enhances our understanding of how they cope with seasonal variations. By examining migratory routes and critical habitats, essential ecosystems and ecological corridors crucial for biodiversity conservation can be identified [3]. Additionally, research on animal migration has valuable implications for agriculture, disease prevention, and various economic sectors [4].

Animal migration is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental, biological, and genetic factors. The geomagnetic field is widely recognized as a key navigational cue, with the magnetoreceptor protein MagR identified as a biological compass underlying magnetoreception [5]. Similarly, sharks have been shown to rely on Earth’s magnetic field for long-distance navigation, which is critical for their migration routes and population structure [6]. Memory also plays a crucial role in migration, as exemplified by the gene ADCY8, which is associated with long-term memory and positively selected in long-distance migratory peregrine falcon populations, highlighting the importance of memory in avian migratory behavior [7]. Olfactory information further contributes to navigation, as birds possess highly developed olfactory receptors enabling scent-based homing [8]. Moreover, migration timing is closely linked to seasonal changes, with internal seasonal clocks detecting photoperiod variations to coordinate migratory and breeding activities. Genes such as CLOCK have been identified as potential circadian regulators aligning these processes [9]. In insects, brain clock genes similarly help monarch butterflies measure photoperiod, facilitating their seasonal migrations [10]. Social learning may additionally influence migratory routes and timing, as shown in various species [11]. Developmental stages also impact migration, with studies on partially migratory bird populations revealing that the transition from juvenile to breeding adult shapes migratory destination, route, and timing [12]. Genetic markers such as microsatellites in green sea turtles have provided insights into population structure and male migration patterns, emphasizing the role of genetic and behavioral factors in marine species migration [13]. Collectively, these findings illustrate that animal migration is governed by multiple, interconnected mechanisms spanning diverse taxa.

Extensive research have been conducted on animal migration, with a predominant focus on avian species, whereas studies on mammalian migration remain relatively limited. Current investigations into mammal migration largely center on ecological aspects and population genetics, with comparative genomics approaches still underexplored. This disparity may stem from previous limitations in the availability and quality of mammalian genome data. Recently, however, the availability of high-quality mammalian genomic datasets has substantially increased, facilitating comparative genomic analyses aimed at uncovering the evolutionary mechanisms underlying long-distance migration in mammals.

In this study, a comparative genomic analysis of representative mammalian species was conducted to investigate the evolutionary patterns of long-distance migratory mammals and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms driving migratory behavior. We identified a series of genes exhibiting significant evolutionary signatures, which are functionally associated with memory, olfaction, vision, locomotor ability, energy metabolism, as well as genomic stability and stress response. These findings may provide novel insights into the molecular evolution of long-distance migration and offer valuable perspectives for the conservation and management of migratory mammal populations.

Methods

Construction of the orthologous gene dataset

This study constructed a high-quality orthologous gene dataset using genome data from 52 representative mammalian species, including 21 well-known long-distance migratory mammals. Genomic data for species such as Black wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), Waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus), Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), Zebra (Equus quagga), and Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) were obtained from the NCBI database, while the remaining genomes were sourced from the Zoonomia project [14]. All genome assemblies had an N50 scaffold value greater than 1 Mb, indicating high quality.

Initially, we used the mouse genome as a reference to perform pairwise alignments of each species’ genome using the LAST (v.2.32.1) software [15]. Next, we combined the pairwise alignment results using the Multiz (v.11.2) software [16] to obtain a multiple alignment. Each coding sequence (CDS) was aligned with the MACSE (v.2.07) software [17], which also helped exclude frameshift mutations arising during alignment. Subsequently, we performed codon-level alignment using the PRANK (v.170427) software [18]. Finally, we filtered out codon sequences with excessive gaps using Gblocks [19] and manually removed any excessively short CDS files, resulting in a total of 11,308 orthologous gene sequences for subsequent analyses.

Selection pressure

To identify coding sequences (CDS) under positive selection in long-distance migratory mammals, we conducted a series of analyses. First, we constructed a species tree for all 52 species using the TimeTree website [20] to accurately reflect the phylogenetic relationships among them. Next, we employed the codeml module in PAML [21] to detect positively selected genes using the branch-site model. The null hypothesis was defined with specific parameters: ModelAnull: model = 2, NSsites = 2, fix_omega = 1, omega = 1, while the alternative hypothesis was defined as ModelA: model = 2, NSsites = 2, fix_omega = 0, omega = 1.5. Prior to running the branch-site model, we designated the 21 long-distance migratory mammals as the foreground branches.

After completing the calculations, we performed a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to evaluate the statistical significance of the alternative hypothesis by calculating its p value, which was then corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method. To enhance the robustness of our results, we applied a more stringent threshold by selecting genes with p values below 0.01 instead of the conventional 0.05 for filtering. A corrected p value less than 0.01 indicated a significant difference between the null and alternative hypotheses. Additionally, we utilized the Bayesian Empirical Bayes (BEB) method to assess the posterior probabilities of potential positively selected sites, retaining those with posterior probabilities greater than 80% as candidates for positive selection.

Accelerated evolution

To identify coding sequences (CDS) that have undergone accelerated evolution in long-distance migratory mammals, we conducted several analyses using the same phylogenetic tree as in the selection pressure analysis. We used the codeml module in PAML to assess accelerated evolution through the branch model. The null hypothesis was defined with the parameters: one ratio: model = 0, NSsites = 0. The alternative hypothesis was set as: two ratio: model = 2, NSsites = 0. We designated the 21 long-distance migratory mammals as the foreground branch.

After completing the analysis, we performed a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to calculate p values. We corrected these p values using the BH method. To enhance the robustness of our results, we applied a more stringent threshold by selecting genes with p values below 0.01 instead of the conventional 0.05 for filtering. A corrected p value less than 0.01 indicated a significant difference between the null and alternative hypotheses. For CDS that met this criterion, we conducted further validation to confirm accelerated evolution. If the analysis produced two ω values, and ω2 was greater than ω1 with a significant p-value, we considered the CDS to have undergone accelerated evolution.

Phenotype-genotype correlation

To explore the relationship between gene evolution rates and long-distance migration in mammals, we employed the Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) method [22]. We analyzed the root-to-tip ω values in relation to whether mammals engage in long-distance migration (assigned a value of 1) or not (assigned a value of 0). The root-to-tip ω value effectively reflects a gene’s evolutionary history while controlling for the effect of time, making it widely used in PGLS analyses.

First, we calculated the average ω value for each branch using the branch model in the codeml module of PAML. This involved determining the average ω value from the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of each target mammal to each extant target mammal, utilizing the free-ratio model. To mitigate the impact of extreme dN or dS values on the analysis, we filtered the ω values. Only those with non-zero N×dN and S×dS, with dS greater than 0.001, were included in the subsequent analysis.

Next, we log-transformed both the ω values and the binary migration status to meet the assumption of normality. We then conducted a regression analysis on the resulting data, calculating p values and applying BH correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Results with corrected p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Convergent evolution

To explore the mechanisms of convergent evolution in long-distance migratory mammals, we conducted analyses from multiple perspectives. We first employed convcal [23] to analyze convergent amino acid substitutions among the species under study. Additionally, we utilized FasParser [24] to identify specific sites in the coding sequences (CDS) of migratory mammals, ensuring that we captured shared mutations that may indicate adaptive evolution. To investigate whether the evolutionary directions of proteins from different lineages were similar, we utilized CSUBST [25] with its default parameters. This analysis allowed us to assess the convergence of protein evolution across various migratory taxa. We also collected relevant results using a custom Python script, which facilitated the extraction of data pertinent to our hypotheses. At the functional level, we performed pathway convergence analysis based on positively selected genes. By integrating these analyses, we aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the convergent evolutionary adaptations that characterize long-distance migration in mammals. Through this multifaceted approach, we hope to uncover key insights into the genetic and functional basis of migration-related traits.

Transcriptome data acquisition and analysis

We obtained transcriptome data for American bison (Bison bison) and domesticated cattle (Bos taurus) from the NCBI SRA database, focusing on four tissues: skeletal muscle, lung, kidney, and liver. Initially, we processed the downloaded SRA files using the fasterq-dump command to obtain raw read sequences. Subsequently, we downloaded the genome FASTA file and the annotation GTF file for American bison and built an index of the genome using the hisat2-build command. We then aligned the transcriptome data to the American bison genome using the hisat2 command [26]. Finally, we quantified the expression levels of each gene using the htseq-count command [27] and analyzed differential expression with edgeR package in R.

Functional enrichment

To understand the roles of the identified genes, we conducted functional and pathway enrichment analyses using Metascape (https://metascape.org/) [28]. We recognized that GO and KEGG results may heavily enrich basic cellular or biochemical processes. This could obscure the direct links between candidate genes and specific phenotypes. Therefore, we performed additional analyses on the target genes. First, we annotated the candidate genes using human disease data from the Genecards database (https://www.Genecards.org/) [29]. This helped us explore potential effects on organ function. Next, we searched for mouse models of the target genes in the MGI database (https://www.informatics.jax.org/) [30]. This analysis aimed to identify potential phenotypic abnormalities linked to gene deletion or knockout. These additional annotations enriched the traditional functional and pathway analyses and provided clearer insights into the biological relevance of the candidate genes.

Results

Genome-wide signatures of selection in long-distance migratory mammals

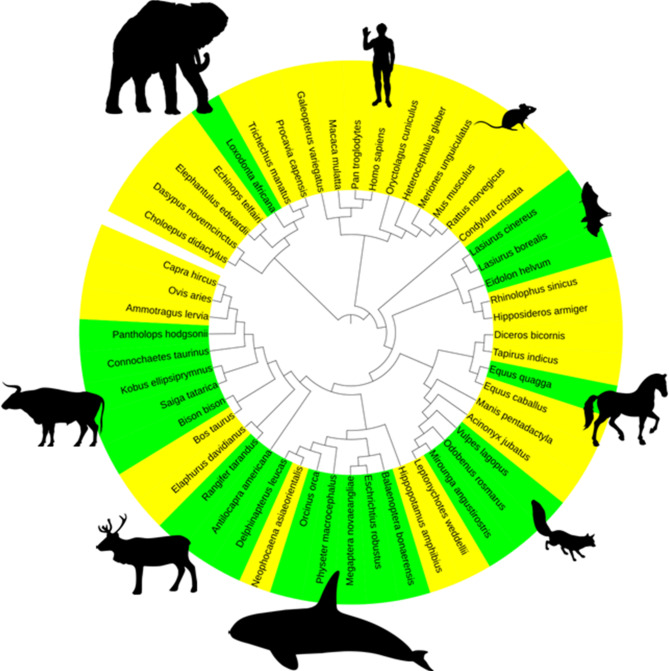

We investigated genome-wide signatures of adaptive evolution in 21 prominent long-distance migratory mammal species. The phylogenetic relationships among the 52 species, based on a dataset of 11,308 orthologous genes, are shown in Fig. 1 (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

A pie chart of the phylogenetic tree for all 52 species, constructed from 11,308 orthologous genes. Branches in green indicate the 21 prominent long-distance migratory mammal species analyzed in this study. The tree was generated using TimeTree

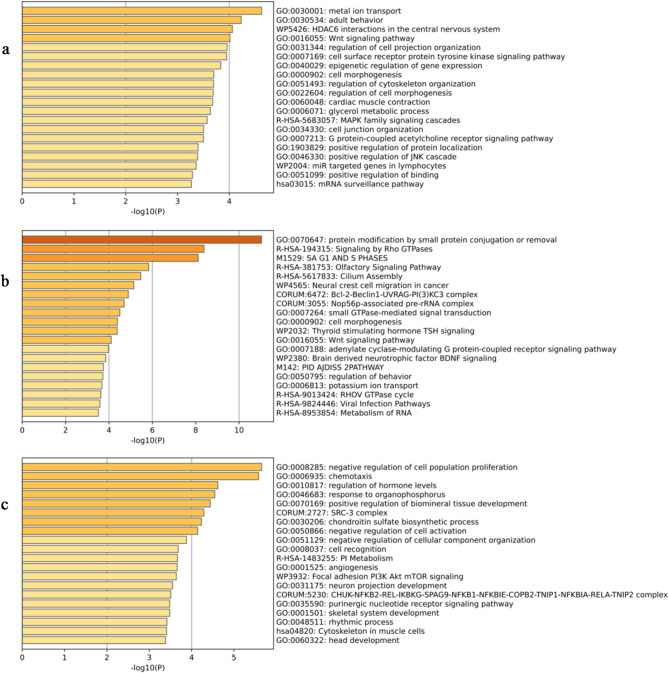

In the branches of 21 long-distance migratory mammals, 195 genes were identified as under significant positive selection (Fig. 2, Table S2). Functional enrichment analyses revealed a notable concentration of genes involved in the development and regulation of the nervous system, including processes such as neuron differentiation, adult behavioral responses, and brain morphogenesis (Figs. 3a, S1). Visual system components, particularly retina morphogenesis, were also enriched. Metabolic pathways related to energy balance showed significant representation, encompassing metal ion transport, glycerol and phosphatidylcholine metabolism, and glucose metabolism pathways (Figs. 3a, S1). Furthermore, genes involved in maintaining genomic stability and responding to cellular stress were notably abundant, including those related to chromosome segregation, DNA double-strand break repair, and oxidative stress response pathways (Figs. 3a, S1).

Fig. 2.

Violin and bar plots illustrating the distribution of p values. The violin plot depicts the distribution of adjusted p values for the selected genes. The three bar plots display the distributions of adjusted p values from the detection of positive selection signals, accelerated evolution signals, and the PGLS analysis, respectively

Fig. 3.

Three bar charts representing the results of functional and pathway enrichment, colored by the size of p values. The x-axis represents the transformed values of adjusted p values as − log10(P_adj). a Enrichment results for 195 PSGs. b Enrichment results for 335 REGs. c Enrichment results for 354 genes associated with long-distance migration

A total of 335 genes exhibiting accelerated evolutionary rates were identified in branches of long-distance migratory mammals (Fig. 2, Table S2), with enrichment analyses revealing significant involvement in multiple biological processes and pathways. Enriched signal transduction pathways included Rho GTPase signaling, olfactory signaling, and cytokine-mediated immune pathways (Figs. 3b, S2). Nervous system development and function were represented by terms related to behavior regulation, cognition, synaptic receptor trafficking and notably the BDNF signaling pathway (Figs. 3b, S2). Additionally, metabolic processes including potassium ion transport and carbohydrate derivative biosynthesis were enriched, indicating roles in energy metabolism. Processes related to cytoskeletal organization and cell migration, such as muscle cell development and actin filament organization, were also significant, linking to locomotor functions (Figs. 3b, S2). Furthermore, terms associated with protein ubiquitination and RNA processing suggested involvement in post-transcriptional regulation and maintenance of genomic stability (Figs. 3b, S2).

From the total of 11,308 gene sequences, 6973 were removed due to non-compliance with N×dN and S×dS value requirements, resulting in a final dataset of 4,335 sequences. PGLS analysis indicated that 354 genes may be associated with long-distance migration in mammals (Fig. 2, Table S2). Enrichment analyses emphasized involvement in signal transduction pathways, particularly those regulating phospholipid metabolism and Rap1 signaling (Figs. 3c, S3). Genes linked to pathways ensuring genomic stability and cellular stress responses were also enriched, including mechanisms responsive to organophosphorus compounds and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Figs. 3c, S3).

An overlap analysis was performed on the 195 genes under positive selection, the 335 genes exhibiting accelerated evolution, and the 354 genes potentially associated with long-distance migration, from which 15 genes were identified as exhibiting both positive selection and accelerated evolution signals. Additionally, 21 genes were found to demonstrate accelerated evolution signals alongside evolutionary rates correlated with migration, while 5 genes were revealed to possess both positive selection signals and migration-related evolutionary rates. We consider these 41 genes as significant candidates with strong evolutionary signals related to long-distance migration (Table 1).

Table 1.

A list for 41 genes that we identified as important candidates exhibiting strong evolutionary signals associated with long-distance migration

The first fifteen genes are both PSGs and REGs. The middle 21 genes are REGs, and their PGLS results indicate an association with long-distance migration. The final five genes are PSGs, and their PGLS results also indicate an association with long-distance migration. The last column of this table represents the systems in which gene-edited mice exhibit abnormal phenotypes, as reported in the MGI database (https://www.informatics.jax.org/) [30] for the corresponding genes

Differences in gene expression patterns in long-distance versus non-long-distance migratory mammals

By comparing the transcriptome data of the American bison, a migratory mammal, with that of domesticated cattle, which are non-migratory, we identified numerous genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated (Fig. 4, Table S3). Using the MGI database for further annotation, knockout studies of the 41 genes with strong evolutionary signals revealed that genes such as PARD3B, STX17, TAGLN, DISP1, ENAH, OPA3 and PIK3R4 are linked to abnormalities in skeletal muscle. Additionally, MALRD1, MMP21, PLAAT3, RALGDS, MTHFD2, OPA3 and UACA knockouts resulted in liver abnormalities. RALGDS and UACA knockouts were associated with kidney dysfunction, while MMP21, RALGDS, CNGA2, DISP1 and UACA knockouts led to respiratory system anomalies. We then overlapped these findings with the differential expression data. In skeletal muscle, American bison showed upregulation of STX17 and OPA3, while TAGLN and PIK3R4 were downregulated compared to domesticated cattle. In the liver, OPA3 was upregulated, while UACA was downregulated. These results highlighted the differential expression of key genes potentially linked to the adaptive traits associated with long-distance migration.

Fig. 4.

Four volcano plots representing the differential expression of genes in four tissues (muscle, lung, liver, and kidney) of American bison and domesticated cattle

Convergent evolution in long-distance migratory mammals

We identified nine genes with specific sites using FasParser. These genes are FRMPD1, CNNM4, ZFP397, DOCK8, SYBU, XPO4, SLC41A1, FAAH and PNN.

We also detected 343 genes with convergent amino acid substitutions in the lineages of long-distance migratory bats using convcal. The functional and pathway enrichment analyses of these 343 genes revealed important terms related to nervous system development and function (Figs. 5a, S4). Key terms included hsa05010 (Alzheimer’s disease), R-HSA−9,675,108 (nervous system development), GO:0022029 (telencephalon cell migration), GO:2,001,251 (negative regulation of chromosome organization), and GO:2,001,223 (negative regulation of neuron migration). Terms related to signal transduction were also present, including GO:0019216 (regulation of lipid metabolic process), GO:1,900,076 (regulation of cellular response to insulin stimulus), and R-HSA−1,638,074 (keratan sulfate/keratin metabolism). Additionally, we found terms related to genomic stability and stress response, including GO:0006979 (response to oxidative stress), GO:0014074 (response to purine-containing compounds), and GO:0045824 (negative regulation of innate immune response).

Fig. 5.

Charts representing convergent evolution. a A chart colored by cluster ID, resulting from the enrichment analysis of convcal. b Results of convergent evolution detection for the genes FAAP24 and ACACB using the CSUBST method. Colored blocks in orange represent cases where ωC ≥ 3, indicating detected signals of convergent evolution between the two lineages. c Four Venn diagrams, where colors indicate different lineages and numbers represent the quantity of pathways. These diagrams illustrate the pathway enrichment of REGs across different lineages and the overlapping enrichment results obtained from this analysis

Using CSUBST, we found that the gene FAAP24 showed similar evolutionary patterns in Beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas), Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), Killer whale (Orcinus orca), and Sperm whale (Fig. 5b). The gene ACACB exhibited similar evolutionary trajectories in American bison, Black wildebeest, Chiru (Pantholops hodgsonii), and Saiga (Saiga tatarica) (Fig. 5b). In bats, the genes INTS4, ZNF282, and RUBCN showed similar evolutionary trends in Straw-colored fruit bat (Eidolon helvum), Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis), and Hoary bat.

The pathway convergence analysis revealed several terms that appeared across multiple lineages (Fig. 5c). The term R-HSA−382,551 was present in four lineages, i.e. Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), Humpback whale, Saiga, and Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus). The term GO:0050808 was found in four lineages, i.e. Pronghorn, Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), Waterbuck, and Saiga. Additionally, the term GO:0000902 was identified in four lineages: Black wildebeest, Straw-colored fruit bat, Eastern red bat, and African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana). Lastly, the term GO:0040029 appeared in four lineages: Waterbuck, Humpback whale, Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), and Chiru.

Discussion

By employing whole-genome selection pressure analysis, accelerated evolution analysis, and PGLS analysis, the molecular adaptive mechanisms associated with long-distance migration have been elucidated. Compelling evidence of molecular convergence in certain species regarding their migratory capabilities provided by the convergence evolution analysis. This integrative approach enhances the understanding of how specific genetic adaptations contribute to the success of long-distance migration in mammals, paving the way for future studies in evolutionary biology and conservation.

Memory is a crucial component of animal migration, guiding migratory behavior and enhancing navigational abilities. Research on the peregrine falcon has identified the gene ADCY8, which is linked to memory and positively selected in long-distance populations, suggesting that long-term memory supports animal migration. A study on zebras developed memory and perception models using remote sensing data, revealing that memory-based models provided more accurate predictions of migratory paths than perception-based models [31]. Furthermore, a decade-long study of blue whales, which combined satellite tracking with oceanographic data, demonstrated that long-term memory and resource tracking are critical for the migration of these large marine animals [32]. In this study, functional enrichment analysis revealed that the BDNF signaling pathway was notably enriched among the 335 accelerated evolution genes. BDNF, or brain-derived neurotrophic factor, promotes neuronal survival and is essential for memory function. Several genes with evolutionary signals are involved in this pathway, including RHOG, BDNF, CFL1, EEF2, GRIA1, NSF, RAC1, KIDINS220, NTF4, CRKL, PLG, BEX3, ADORA2A, GTF2F1, ID2, HNRNPM, PAK1, POLR2J, SOCS6, and PIK3R4. Among the 41 genes exhibiting strong evolutionary signals, annotation using the GeneCards database identified genes such as BDNF, IFT70B, MALRD1, DISP1, PIK3R4, SPCS2, and TRMT12 as potentially influencing long-term memory. The genes RHOBTB2 and TCTN3 may impact spatial memory. Additionally, pathway convergence analysis indicated that the term GO:0050808 appeared in four lineages, associated with synapse formation and maintenance, which are critical for stabilizing neural networks. During long-distance migration, this pathway may enhance navigation, support spatial memory, improve synaptic plasticity, and maintain neural network stability. In summary, memory is essential for migration, providing a foundation that supports successful navigation in complex environments.

Sensory abilities are crucial in animal migration. Vision plays a key role, as it helps migratory animals utilize photoperiods [33] and influences their navigational capabilities [34]. For instance, the brain of Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) exhibited characteristics similar to those of other insects, mediating behaviors related to visual cues and spatial awareness, thus facilitating successful migration [35]. In addition to vision, olfactory cues are vital for navigation in many species, particularly birds, as it has been suggested that they can navigate using scents in the air. Three hypotheses have been proposed for olfactory navigation: the mosaic hypothesis, which relies on identifying scent direction relative to nesting sites [36]; the olfactory activation hypothesis, which posited that olfactory receptors activate navigation mechanisms [37]; and the gradient map hypothesis, which suggested that geographical variations in scent concentration help determine locations [38]. To further understand the role of sensory abilities, the 41 genes with strong evolutionary signals were annotated using the MGI database. It was found that genes such as BDNF, MALRD1, PARD3B, DISP1, HNMT, LAMC3, MTHFD2, MYRF, OPA3, SERPINB2, SLC22A7, and TCTN3 are associated with visual abnormalities when knocked out in mice. Additionally, the functional enrichment analysis of the 335 accelerated evolution genes showed significant enrichment in the R-HAS-381,753: Olfactory Signaling Pathway. This pathway involved several genes with evolutionary signals, including CNGA2, CNGA4, EBF1, OR8B8, OR52K2, OR10Z1, OR6B1, OR13C3, OR52I2, OR8B12, OR9Q2, OR2AT4, OR2W3, OR51D1, OR51I1, OR5W2, OR8A1, GNB1, GFY, CABP1, PAK1, and PKDREJ. Notably, genes BDNF and CNGA2 from the MGI analysis also resulted in olfactory abnormalities when knocked out in mice. In summary, both visual and olfactory sensory abilities are essential for navigation in migratory species, highlighting the importance of sensory adaptations in the context of migration.

In addition to the previously mentioned genes, other genes exhibiting evolutionary signals may reveal additional adaptive mechanisms that mammals utilize during long-distance migration. Exceptional locomotor capabilities are vital for animals undertaking such migrations [39]. Among the 41 genes with strong evolutionary signals, TAGLN shows differential expression in skeletal muscle between American bison and domesticated cattle. This gene played a crucial role in regulating the organization and function of actin, influencing muscle contraction, cell signaling, and repair processes, significantly impacting locomotor abilities. Furthermore, efficient energy use is critical during long-distance migrations [40]. The pathway convergence analysis identified the term GO:0000902 which appeared in four distinct lineages: Black wildebeest, Straw-colored fruit bat, Eastern red bat, and African savanna elephant. This pathway may regulate energy metabolism, providing the physiological and organizational adaptations necessary for migration. Furthermore, during the intense pressures of long-distance migration, animals must possess mechanisms for genomic stability and stress response [41]. In the CSUBST analysis, the evolutionary trajectory of the gene FAAP24 was found to be similar across the lineages of Beluga whale, Gray whale, Killer whale, and Sperm whale. FAAP24 plays a key role in DNA damage repair and prevention of mutation accumulation. During long-distance migration, it may help maintain genomic stability, ensuring survival and supporting migratory activities at the molecular level. In summary, various adaptive mechanisms, including enhanced locomotor abilities, efficient energy utilization, and genomic stability, are vital for mammals during long-distance migration.

Although we did not perform targeted knockout experiments for the candidate genes using model species, extensive research employing gene-edited mouse models already demonstrated clear links between these genes and their associated phenotypes. For instance, a study reported that increased hippocampal BDNF expression in mice significantly enhances spatial memory [42], while inhibition of BDNF signaling attenuates improvements in learning and memory. Similarly, another study showed that loss-of-function mutations in CNGA2 result in complete anosmia in mice [43]. These established functional validations could provide strong support for the involvement of our candidate genes in relevant biological processes, thereby demonstrating their potential roles in mammalian migratory behaviors. Of course, it is still necessary to conduct more functional experiments for more genes in the future for in-depth uncovering the driving mechanisms underlying this complex trait of mammals.

Despite the significant progress made in this study, certain details still require further investigation. For instance, although we detected signals of adaptive evolution related to olfaction in long-distance migratory mammals, this should not be simply interpreted as an enhanced sense of smell. For example, long-distance migratory whales are typical olfactory-degenerated animals, which may imply that they have undergone certain unique adaptive changes in their olfactory system to accommodate their migratory lifestyle. Therefore, future research focusing on independent and in-depth analyses of each long-distance migratory mammal lineage will likely be an important direction. Besides, simplifying long-distance migration as a binary trait (yes/no) is a necessary but limited approach. Future studies should consider migration distance, patterns, and frequency as continuous traits if possible.

Conclusion

Our comparative genomic analysis has unveiled the adaptive evolutionary mechanisms associated with long-distance migration in mammals, which are primarily linked to various aspects, including memory, sensory abilities, locomotor capabilities, energy metabolism, and genomic stability. Our findings suggested that specific genes have undergone significant positive selection and accelerated evolution in long-distance migratory species, particularly those related to migratory behavior and supportive mechanisms such as BDNF and CNGA2, which may play crucial roles in memory and navigational capabilities. Furthermore, convergent evolution analysis highlighted critical roles of sensory abilities, locomotor ability, energy metabolism, as well as genomic stability and stress response in successful migration. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the ecological adaptations underlying long-distance migration but also provide new perspectives for further investigation into the functions of migration-related genes. Future research should focus on the study of regulatory elements and the experimental validation of key gene functions to elucidate their specific roles in the adaptive processes of migration.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CDS

Coding sequence

- LRT

Likelihood ratio test

- BH

Benjamini-Hochberg (multiple testing correction method)

- PGLS

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- SRA

Sequence read archive

- MGI

Mouse genome informatics

- GO

Gene pntology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- BEB

Bayesian empirical bayes

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- ω(omega)

Ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS), indicative of selection pressure

Author contributions

GY designed this project. HY, DX and GX collected the data. HY performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript with contribution from GY. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32030011, U24A20362), National Key Programme of Research and Development, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. SQ2022YFF1300033), PI Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) (GML2021 GD0805), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and its additional files, including 4 tables and 9 figures. Genomes used are available in Table S1, transcriptome data used are in Table S3. All analyses in this study followed the software and pipeline manuals and tutorials. Default or author-recommended parameters were used unless otherwise stated. The scripts and pipelines used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu J, Zhang ZW, Coulson T, et al. Seasonal density-dependence can select for partial migrants in migratory species. Ecol Monogr. 2025. 10.1002/ecm.70009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, et al. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008. 10.1073/pnas.0800375105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labastida-Estrada E, Machkour-M’Rabet S. Unraveling migratory corridors of loggerhead and green turtles from the Yucatán Peninsula and its overlap with bycatch zones of the Northwest Atlantic. PLoS One. 2024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0313685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altizer S, Bartel R, Han BA. Animal migration and infectious disease risk. Science. 2011. 10.1126/science.1194694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin S, Yin H, Yang C, et al. A magnetic protein biocompass. Nat Mater. 2016. 10.1038/nmat4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller BA, Putman NF, Grubbs RD, et al. Map-like use of earth’s magnetic field in sharks. Curr Biol. 2021. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu Z, Pan S, Lin Z, et al. Climate-driven flyway changes and memory-based long-distance migration. Nature. 2021. 10.1038/s41586-021-03265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krause ET, Krüger O, Kohlmeier P, et al. Olfactory kin recognition in a songbird. Biol Lett. 2012. 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gwinner E. Circannual rhythms in birds. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003. 10.1016/j.conb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reppert SM, Guerra PA, Merlin C, et al. Neurobiology of monarch butterfly migration. Annu Rev Entomol. 2016. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller T, O’Hara RB, Converse SJ, et al. Social learning of migratory performance. Science. 2013. 10.1126/science.1237139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan YC, Kormann UG, Witczak S, et al. Ontogeny of migration destination, route and timing in a partially migratory bird. J Anim Ecol. 2024. 10.1111/1365-2656.14150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanabe LK, Cochran JEM, Berumen ML, et al. Inter-nesting, migration, and foraging behaviors of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the central-southern red sea. Sci Rep. 2023. 10.1038/s41598-023-37942-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christmas MJ, Kaplow IM, Genereux DP, et al. Evolutionary constraint and innovation across hundreds of placental mammals. Science. 2023. 10.1126/science.abn3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kietbasa SM, Wan R, Sato K, et al. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 2011. 10.1101/gr.113985.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchette M, Kent WJ, Riemer C, et al. Aligning multiple genomic sequences with the threaded blockset aligner. Genome Res. 2004. 10.1101/gr.1933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranwez V, Douzery EJP, Cambon C, et al. MACSE v2: toolkit for the alignment of coding sequences accounting for frameshifts and stop codons. Mol Biol Evol. 2018. 10.1093/molbev/msy159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löytynoja A. Phylogeny-aware alignment with PRANK. Methods Mol Biol. 2014. 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007. 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Suleski M, Craig JM, et al. TimeTree 5: an expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol Biol Evol. 2022. 10.1093/molbev/msac174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007. 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Z, Seim L, Yin M, et al. Comparative analyses of aging-related genes in long-lived mammals provide insights into natural longevity. Innov. 2021. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou Z, Zhang J. Are convergent and parallel amino acid substitutions in protein evolution more prevalent than neutral expectations? Mol Biol Evol. 2015. 10.1093/molbev/msv091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun YB. FasParser2: a graphical platform for batch manipulation of tremendous amount of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2018. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukushima K, Pollock DD. Detecting macroevolutionary genotype-phenotype associations using error-corrected rates of protein convergence. Nat Ecol Evol. 2023. 10.1038/s41559-022-01932-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, et al. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019. 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq—a python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019. 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, et al. The genecards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2016. 10.1002/cpbi.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldarelli RM, Smith CL, Ringwald M, et al. Mouse genome informatics: an integrated knowledgebase system for the laboratory mouse. Genetics. 2024. 10.1093/genetics/iyae031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bracis C, Mueller T. Memory, not just perception, plays an important role in terrestrial mammalian migration. Proc R Soc B. 2017. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrahms B, Hazen EL, Aikens EO, et al. Memory and resource tracking drive blue Whale migrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019. 10.1073/pnas.1819031116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.el Jundi B, Pfeiffer K, Heinze S, et al. Integration of polarization and chromatic cues in the insect Sky compass. J Comp Physiol Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2014. 10.1007/s00359-014-0890-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyers D, Manns M, Luksch H, et al. A visual pathway links brain structures active during magnetic compass orientation in migratory birds. PLoS One. 2007. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerra PA, Merlin C, Gegear RJ, et al. Discordant timing between antennae disrupts sun compass orientation in migratory monarch butterflies. Nat Commun. 2012. 10.1038/ncomms1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kishkinev D. Sensory mechanisms of long-distance navigation in birds: a recent advance in the context of previous studies. J Ornithol. 2015. 10.1007/s10336-015-1215-4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorge PE. Odors in the context of animal navigation. In: Logan E. Weiss, Jason M. Atwood, editors. The biology of odors. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2011. p. 207–226.

- 38.Gagliardo A, Bried J, Lambardi P, et al. Oceanic navigation in cory’s shearwaters: evidence for a crucial role of olfactory cues for homing after displacement. J Exp Biol. 2013. 10.1242/jeb.085738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tigano A, Russello MA. The genomic basis of reproductive and migratory behaviour in a polymorphic salmonid. Mol Ecol. 2022. 10.1111/mec.16724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somveille M, Rodrigues ASL, Manica A. Energy efficiency drives the global seasonal distribution of birds. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018. 10.1038/s41559-018-0556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García-Berro A, Talla V, Vila R, et al. Migratory behaviour is positively associated with genetic diversity in butterflies. Mol Ecol. 2023. 10.1111/mec.16770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El Hayek L, Khalifeh M, Zibara V, et al. Lactate mediates the effects of exercise on learning and memory through SIRT1-dependent activation of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). J Neurosci. 2019. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karstensen HG, Mang Y, Fark T, et al. The first mutation in CNGA2 in two brothers with anosmia. Clin Genet. 2015. 10.1111/cge.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and its additional files, including 4 tables and 9 figures. Genomes used are available in Table S1, transcriptome data used are in Table S3. All analyses in this study followed the software and pipeline manuals and tutorials. Default or author-recommended parameters were used unless otherwise stated. The scripts and pipelines used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.