Abstract

The Tabula Sapiens is a reference human cell atlas containing single cell transcriptomic data from more than two dozen organs and tissues. Here we report Tabula Sapiens 2.0 which includes data from nine new donors, doubles the number of cells in Tabula Sapiens, and adds four new tissues. This new data includes four donors with multiple organs contributed, thus providing a unique data set in which genetic background, age, and epigenetic effects are controlled for. We analyzed the combined Tabula Sapiens data for expression of transcription factors, thereby providing putative cell type specificity for nearly every human transcription factor and as well as new insights into their regulatory roles. We analyzed the molecular phenotypes of senescent cells across the entire data set, providing new insight into both the universal attributes of senescence as well as those aspects of human senescence that are specific to particular organs and cell-types. Similarly, we analyzed sex-specific gene expression across all of the identified cell types and discovered which cell types and genes have the most distinct sex based gene expression profiles. Finally, to enable accessible analysis of the voluminous medical records of Tabula Sapiens donors, we created a web application powered by a large language model that allows users to ask general questions about the health history of the donors.

Introduction

Single cell transcriptomic atlases are providing substantial new insights into human biology, including the molecular definitions of cell types, the cell type specific expression of disease-related genes, and the relationships of shared cell types across tissues, particularly those of the immune system1–6. These atlases are powerful reference tools whose applications in biology are just beginning to be explored. Many questions which could previously only be addressed at the bulk tissue level can now be answered with cell type specificity, thus yielding crucial new insights6–8.

Our previous efforts focused on creating a reference human cell atlas, called the Tabula Sapiens 1.0, which consisted of data from 24 different organs and tissues from a diverse set of donors1. In Tabula Sapiens 2.0, we have now doubled both the number of cells and the number of donors with multi-organ contributions, thus increasing the number of tissues and donors for which genetic background, age and epigenetic effects are controlled for. Specifically, we report data from nine new donors comprising one donor with 20 tissues, one donor with 18 tissues, one donor with 15 tissues, one donor with 2 tissues, and five donors with 1 tissue each. The updated combined Tabula Sapiens dataset contains more than 1.1 million cells from bladder, blood, bone marrow, eye, ear, fat, heart, kidney, large intestine, liver, lung, lymph node, mammary, muscle, ovary, pancreas, prostate, salivary gland, skin, small intestine, spleen, stomach, testis, thymus, tongue, trachea, uterus, vasculature. Single cell transcriptomes were obtained from live cells using both droplet microfluidic emulsions (1,093,048 cells) as well as FACS into well plates (43,287 cells).

To illustrate the utility of this reference dataset, we conducted several genome-wide expression studies. Our investigation mapped which transcription factors are active in specific cell populations, revealing cell-type associations for over a thousand regulatory proteins and uncovering previously unknown aspects of their functional contributions. Additionally, we examined aging-related cellular characteristics throughout our complete collection, which revealed which common gene expression modules used by all senescent cells alongside organ- and cell-specific aging patterns. We further explored how gene activity differs between males and females across every cell population in our study. This analysis revealed that biological sex influences gene expression primarily through cell-level regulatory mechanisms rather than through tissue-level differences. The data set is publicly available and we have also created an AI based tool to explore the clinical histories of the donors.

Results

Overview of Tabula Sapiens 2.0

The Tabula Sapiens 2.0 is an integrated map of 28 tissues collected across 24 donors. Nine new donors and four new tissues were collected and analyzed together with the original Tabula Sapiens 1.0 dataset (Fig. 1, Supp. Fig. 1 –Supp. Fig. 6). All tissues and organs, with the exception of the respective reproductive organs, were profiled from both male (n=11) and female (n=13) donors. The donor’s age ranges from 22 to 74 years old, offering one of the most comprehensive molecular profiles of human tissues across the adult lifespan (7 donors under the age of 40, 11 donors between 40 and 60, and 6 donors over 60 years of age). A detailed table with metadata can be found in Supp. Table 1.

Figure 1. Overview of tissue donor demographics and tissue composition in Tabula Sapiens 2.0.

The central anatomical illustration highlights the location of various tissues sampled from male and female donors, organized into distinct anatomical systems. Surrounding the anatomical figures are circular arrangements of charts showing the donor demographics of samples across various tissues. The inner stacked bar chart color-coded by donor sex for samples across every tissue (blue: male, pink: female). The diamond plot shows the donor age for samples across every tissue (green diamond: under 40, yellow diamond: 40–59, purple diamond: over 59). The bar plot shows the number of cells per donor for samples across every tissue with tissue color coded by donor ID. The outer stacked bar plot shows the donor composition for samples across every tissue. Tissues are labeled around the circular chart, providing an accessible visual summary of the tissue distribution and donor demographics.

For each organ and tissue, a group of experts used a defined cell ontology terminology to annotate cell types consistently across the different tissues, leading to a total of 701 distinct cell populations representing cell type combined with tissue of origin designation. The full dataset can be explored online using CELLxGENE9,10.

Transcription factor analysis across cell types

A fundamental aspect of cell state and cell identity is the regulation of gene expression by transcription factors. Several large-scale consortia have systematically mapped human transcription factor (TF) activity at the tissue level. The ENCODE Project11 established standardized pipelines for genome-wide TF binding site identification using ChIP-seq and DNase-seq footprinting, generating high-resolution maps of regulatory DNA occupancy. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium12 expanded this work by creating reference epigenomic maps for 127 cell lines and tissues, integrating histone modifications, DNA methylation, and chromatin accessibility to contextualize TF function. The GTEx Consortium13 developed statistical approaches to infer individual-specific TF activities from RNA-seq data across 49 tissues, identifying genetic variants (QTLs) that modulate TF regulatory effects. Complementing these efforts, the FANTOM Consortium used deepCAGE technology to profile transcription initiation events and reconstruct TF interaction networks governing cellular differentiation. While these foundational studies focused on bulk tissue methods, more recent work has used TF overexpression in single cells to reveal insights into TF-driven human developmental trajectories14.

Of the 1639 putative transcription factors (TF) in The Human Transcription Factors database15 (HTF) we investigated the 1637 TFs which appear in GRCh38 gene annotations. We computed the mean of the log-normalized expression of each transcription factor across the 175 cell types detected in our droplet microfluidic dataset. All but two TF’s are expressed in at least one cell type in this data set. SHOX and ZBED1, both from the pseudoautosomal region 1 of the X and Y chromosomes, have zero raw droplet counts in every donor. The Human Protein Atlas16–18 (HPA) reports RNA and protein detection of SHOX in a broad range of tissues with enrichment in basophils, as well as expression in fibroblast cell lines. ZBED1 is found in a small number of cells across all cell types in our plate data and the HPA also reports ubiquitous cell type expression. We therefore have been able to establish the cell type specificity of all known human transcription factors.

In order to test whether gene expression of these transcription factors was also accompanied by activity, we used the SCENIC software package to infer TF activity in single cells of each cell type separately. SCENIC identifies TF’s target genes through co-expression-based GRN inference algorithms and presence of binding motifs in proximity to target genes. Activity of these TF regulons is then scored by enrichment of the identified target gene set in each cell. Of 1390 TFs that met SCENIC’s entry criteria we found 839 regulons in at least one cell type. The remaining 551 did not survive SCENIC’s filters at various stages; this does not mean they didn’t have significant co-expression with others genes but that their co-expression was below an internal threshold. Across the 38 broad cell classes, SCENIC identified varying numbers of active TF regulons (mean=80.3, sd=59.6). Individual regulons were found in up to 31 cell types with most regulons, however, showing high cell type specificity, being found on average in 3.6 cell types (sd=4.0) (Supp. Fig. 7). Overall this provides evidence of activity by downstream gene expression for roughly half of the human TF’s and does not rule out activity for the remainder.

To establish transcription factor cell type and tissue specificity, we computed the specificity statistic τ 19,20 across all donors (Methods, Supp. Table 2). When computed on 5 individual samples we found r = 0.76 to 0.81 sample-to-sample correlation (Supp. Fig. 8). This statistic was developed for microarray and bulk tissue RNA-seq studies, and has recently been used to determine cell-type specificity in single-cell mRNA-seq data studies such as the Drosophila cell atlas21 and a mouse brain atlas22. As seen in bulk mRNA-Seq studies13, we found the τ distribution dips at τ ≅ 0.85. This same 0.85 dip occurs in the Tabula Muris Senis and Drosophila single cell atlas datasets; and also when τ is computed on a tissue basis or on a broad cell type basis in our data. Thus we defined the 890 TF’s above this as cell type specific (Fig. 2A). We defined the 745 TF’s with τ < 0.85 as non-specific and used the 100 lowest τ TF’s to explore the space of ubiquitous TF’s. To visualize TF expression we placed the TFs in τ order and grouped expression values by 38 broad cell class categories to create an expression heatmap (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Transcription factor expression common across cell types.

A) Histogram of the distribution of τ values for 1635 transcription factor genes computed across 175 distinct cell types in 28 Tabula Sapiens 2.0 tissues, marked with specificity threshold at τ > 0.85. B) Heatmap of the mean of log normalized expression in each cell type of 1635 TF’s in the 175 cell types. The mean expression values range from 0.0 to 4.9 but for better visualization in the heatmap they have been clipped to the 99.0 percentile resulting in the heatmap scale from 0 to about 1.0. Cell types are in alphabetical order by broad cell type. Transcription factors are arranged in τ value order from from 0.4 to 1.0 τ. The vertical bars on the heatmap mark the lowest 100 τ ubiquitous TF’s, 745 τ < 0.85 non-specific TF’s and the 890 τ > 0.85 cell type specific TF’s. C) Distribution of the 72 ubiquitous sc-mRNA expressed TF’s detected as expressed proteins by immuno-staining in 20 common tissues in the Human Protein Atlas. D) Distribution of nuclear expression of 69 ubiquitous TF’s across 20 tissues. E) Summary of the Enricher GO analysis of the 745 non-cell type specific transcription factors outlined in black in A. Enrichr returned 70 GO terms that were organized by broad cell function categories shown in the circles with the number of GO terms and genes in each category. Sub-categories are shown in the rectangles with the number of GO terms and genes in each.

Among the 100 TF’s labeled as ubiquitous, we found many well studied factors known to be central to universal cell function such as stress response, proliferation and metabolism. Examples of these include NFAT5, NCOA1, FOXJ3, FOXK2, ATF4, JUN, FOS and STAT1. To validate the existence and roles of the ubiquitous TF’s, we searched the HPA for evidence of protein expression. Of the 100 ubiquitous TF’s, 72 were tested in the HPA; every single one of these was detected in at least one tissue and the majority (71%) were detected in 19 or 20 of the 20 tissues tested. (Fig 2C, Supp Fig. 9A). In the 32 cell types, all 72 low τ TF’s tested were detected in many cell types. The fraction detected in more than 80% of cell types was 0.69, vs 0.40 for all 699 TF’s. (Supp Fig. 9C–D). To further confirm the likelihood these TF’s are active, we queried the HPA for the subcellular location of expression of the 72 ubiquitous TF’s; the HPA detected expression in the nucleus for 69 of these across a broad set of tissues Altogether there is evidence of protein expression for 100% of the ubiquitous TFs found in the HPA and evidence of activity based on nuclear localization for 96% of them (Fig 2D).

We explored the biological function of the full set of 745 non-specific TF’s (τ < 0.85) by performing Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (Fig. 2E, Methods, Supp. Table 3) and grouping the GO terms into four broad cellular function categories: Gene Expression and Regulation, Tissue Maintenance, Cell Response to Stimulus, and Cell Metabolism. Within the Gene Expression and Regulation category, we found 25 Gene Ontology (GO) terms and sub-grouped these into gene transcription, gene regulation, gene expression of miRNA and chromatin remodeling as needed for the cell to synthesize mRNA and miRNA. Gene regulation comprises 11 GO terms and dominates the number genes driving these terms, 672, by an order of magnitude.

Transcription factors for maintenance of tissues are enriched in our data in 18 GO terms. We grouped these into cell cycle regulation, cell differentiation, cell proliferation and anatomical structure maintenance. Cell cycle regulation enriched for 33 genes in three GO terms. These genes include TFDP1 and TFDP2 which form complexes with E2F transcription factors to control cell cycle23,24 and E2F6 which specifically blocks cell cycle entry25. The cell differentiation group includes the two broad terms negative regulation of cell differentiation (GO:0045596) and positive regulation of cell differentiation (GO:0045597), as well as terms identified as specific for a variety of cell types. There are 61 transcription factors enriched in the cell differentiation category. Of these, ARNT, ARNTL, CEBPB, CREB1, CREBL2, ETS1, FOXO1, FOXO3, HIF1A, PPARD, SMAD3, STAT1, STAT3 ,STAT5B, XBP1, ZBTB16, ZFPM1 and ZNF16 are enriched in three or more terms. Cell proliferation has four GO term a): regulation of transforming growth factor beta2 production (GO:0032909), b) hemopoiesis (GO:0030097), c) regulation of cell population proliferation (GO:0042127), and d) positive regulation of myoblast proliferation (GO:2000288). These terms have enriched genes, including the 3 ATP-1 binding factors JUN, JUNB, and JUND; 6 STAT family transcription factors (which respond to growth factor receptors) and KLF4, KLF10, KLF11 (which can negatively regulate cell growth). The anatomical structure maintenance group contains two GO terms with 17 enriched transcription factors. These include all 3 PBX TF’s of the TALE family that interact with the HOX domain26; and 3 of the 4 TEAD factors known in humans to regulate tissue size and function by coupling external signals to control cell growth and specification27.

Response to a cell’s environmental stimuli is found in five groups of GO terms: chemical signaling, cell signaling, immune signaling, hormone response, and general stress response. Cell response to stress encompasses responses to fluid stress, laminar flow stress, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and chemical stress. Note, some transcription factors may be induced beyond natural levels due to processing tissue into live single-cells for analysis. Among 16 stress response genes, ATF3, ATF4, ATF6, CEBPB, DDIT3, HIF1A, KLF2, KLF4, NFE2L2, RBPJ, and TP53 are enriched in association with two or more GO terms. KLF2 and KLF4 are suggested to be part of the Golgi stress response28. Also enriched is SREBF2, which regulates cholesterol synthesis in response to a broad set of stresses including inflammation, heat shock and hypoxia29. Oxidative stress response is thought to be regulated by enriched NFE2L2 (NRF2)30 through the KEAP1-NRF2-ARE pathways31, as well as by HIF1A32. GO terms for cell signaling fall into three groups, cell signaling, IL6 and IL9 immune signaling, and peptide hormone signaling. They share the common STAT signaling pathway whereas cell signaling selectively utilizes NFAT TF’s and hormone signaling utilizes NCOA TF’s33.

Within the 10 GO terms enriched for cell metabolism four involve regulation of macromolecule synthesis, five terms regulate lipid synthesis, and one maintains glucose homeostasis. The four macromolecule synthesis terms include 217 TF’s, more TF’s than any set of terms other than gene regulation.

Within the non-specific TFs we observed many widely expressed zinc finger DNA binding family TF’s. Of these, the Human Transcription Factor Database shows many are only computationally predicted, or have no defined motif, and lack experimental validation. Often the literature only mentions differential expression in the context of disease, with no known function. It is striking that so many broadly expressed transcription factors exist and are not well characterized, including many that are ubiquitous across cell types.

We then examined transcription factor expression levels for the 890 cell type specific TF’s (τ>0.85). We discovered both previously known as well as novel relationships between specific TF’s and the cell types in which they are expressed (Fig. 3A). Each TF was grouped with the cell type of its highest mean expression and plotted in broad cell class alphabetical order. Vertical lines show the ubiquitous TF’s are redistributed throughout cell types, while the horizontal bars reveal highly expressed TFs in each cell type or in a broad cell class. This provides putative cell type association for the specific TF’s, many of which previously have only been identified within the context of bulk tissue expression.

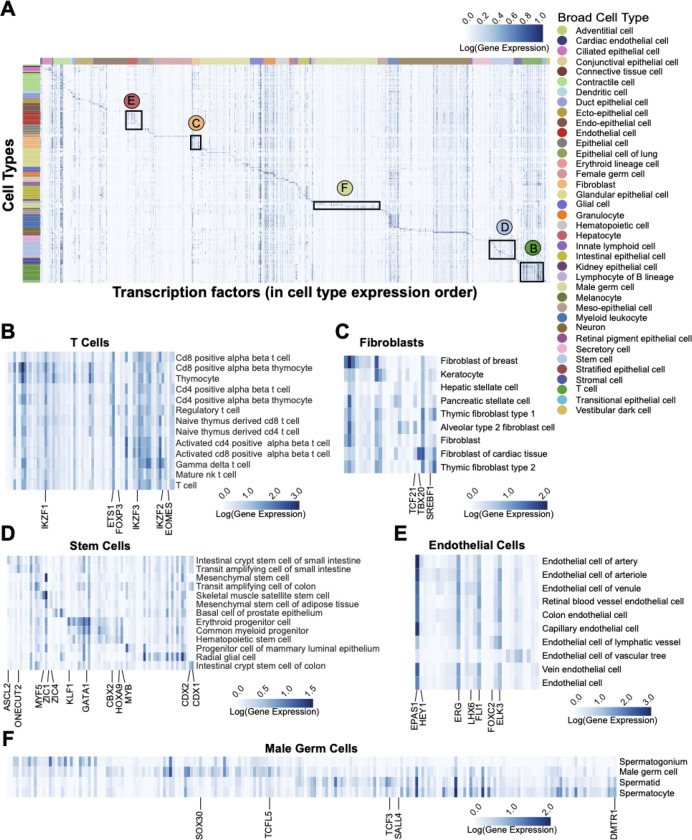

Figure 3: Transcription Factors Specific to Cell Types.

A) Expression heatmap showing the mean of the log normalized expression values of 1635 human transcription factors in 175 cell types using all 28 Tabula Sapiens 2.0 tissues. For better visualization in the full heatmap (A) the max values are clipped at the 99.5 percentile. The cell type rows are organized alphabetically by broad cell type and denoted by color on the annotation bar. The TF columns are arranged according to the cell type for which they show the highest expression. Black outlines highlight examples of common broad cell types and refer to sub-figures B-F, which are not clipped at the 99.5 percentile in order to show the full range of expression. B) T-Cells. C) Fibroblasts. D) Stem Cells. E) Endothelial Cells. F) Male Germ Cells.

Within the T-cell broad cell class we identify five TF’s with τ > 0.85 FOXP3, EOMES, and three Ikaros TF’s (IKZF1, IKZF2, and IKZF3), suggesting they are specific to T-cells (Fig. 3B). FOXP3 expression is the defining factor for FOXP3 Treg cells34. In these cells it coordinates with ETS1, which we see expressed across all T-cell types35. EOMES highest expression is in Mature NK T cells and CD8 positive alpha beta T cells36. The three Ikaros family TF’s are well known to regulate all types of lymphocyte cell development37,38. We find them expressed throughout T-cell types.

Gene expression profiles in fibroblast cells are heterogeneous and often more organ or environment specific than cell type specific39–42. Thus, over 80% of cells in this broad category have been typed only generally as ‘fibroblast cell’ (Fig. 3C). We do find three fibroblast/organ specific TF’s where we have specific fibroblast cell types. In the lung, TCF21 has highest expression in alveolar type-2 fibroblast cells where it regulates lipofibroblast differentiation and serves as a marker for these cells43, TBX20 plays a key role in development and maintenance of healthy cardiac tissue44 and SREBF1 expression in thymic fibroblasts is known to be required for activated T-cell expansion45.

Our data show nine stem cell type specific TF’s involved in the generation of fat, bone, blood, and gut cells (Fig. 3D). ZIC1 and ZIC4 have their highest expression in mesenchymal stem cells of adipose tissue, where ZIC1 is known to direct stem cell fate between osteogenesis and adipogenesis46. We also see ZIC1 and MYF5 expressed in skeletal muscle satellite stem cells where they regulate myogenesis47. ZIC1 is suggested to be involved in brown fat precursor differentiation or in white-to-brown transdifferentiation48. Gut stem cells are known to be maintained by CDX2 and CDX149, and these two regulatory TF’s have τ > 0.85 in our data, with their highest expression found in transit amplifying cells and intestinal crypt stem cells in both the small intestine and colon. Specific to small intestine crypt stem cells we find expression of ASCL2, a master controller of intestinal crypt stem cell fate50. ONECUT2, a downstream target of ASCL2, has its highest expression in transit amplifying cells and crypt stem cells. However, ONECUT2 expression is not restricted to the broad stem cell type in our data as it has similar expression levels in all the small intestine enterocyte cell types. ONECUT2 is also suggested to regulate differentiation of M cells of Peyer’s patches51. Three TF’s with τ > 0.85 have their highest expression in hematopoietic stem cell types. Consistent with the literature, MYB is found in decreasing amounts in hematopoietic stem cells, then myeloid progenitors and then erythroid progenitors. It also shows some expression in the intestines52. It is worth noting that genes most famous for their roles in early development, such as the Homeobox family and the Yamanaka factors, are also known to be expressed in adult cell types and are present in our data. For example HOXA9 and CBX2, necessary for embryonic development and hematopoiesis53–55, show the decreasing expression from hematopoietic stem cell type to progenitor cell types. We also see TF’s KLF1 and GATA1 increasing expression in sequence towards development of erythroid progenitor cells56,57.

The broad endothelial cell class heatmap (Fig. 3E) reveals 18 TF’s with > 0.85 τ. Of these, HEY1, shows higher expression in the arterial vascular cell types where it may mediate arterial fate decisions58. Similarly, LHX6 has been extensively studied in neuron development59, but in our data is expressed in vein and venules endothelial cells suggesting a regulatory role in venous fate. FOXC2 is expressed highest in lymphatic cells where it is known to regulate formation of the lymphatic system60. Together these TF’s appear to regulate the fate of all the three types of vascular structures, arterial, venous and lymphatic. Finally, we see ERG expression known to stabilize vascular growth through regulation of VE-caderhin61 and known to maintain vascular structure by repressing proinflammatory genes62. We see several less cell type specific TF’s with high expression which are also known to regulate stability of the vascular tree. FLI1 and ERG prevent endothelial to mesenchymal transition63. ELK3 suppresses further angiogenesis64. EPAS1 (HIF2A) regulates physiological response to oxygen levels. Interestingly, some EPAS1 alleles contribute to high altitude athletic performance65,66.

Finally, we highlight male germ cells which have 204 TF’s with their highest expression in the four cell types in this broad cell class (Fig. 3F). In addition, 50% of these are > 0.85 τ testis specific, consistent with findings in Drosophila21. Over 50% of these specific TF’s begin with the letter ‘Z’ indicating a zinc finger motif. This appears to be a rich area for further study as most of these TF’s are computationally derived and/or understudied, especially in humans, as most work has been done in mice. Spermatogenesis is driven by specific TF’s through four stages, going from male germ cell to spermatogonia via mitosis, then to spermatocyte and spermatid through meiosis, to become sperm67. As is known, our data shows specific expression of SALL4 in male germ cells where it maintains this pool of cells68,69. DMRT1 is known to specifically coordinate male germ cell differentiation and our data shows its expression growing from male germ cells to the spermatogonia phase70,71. Spermatogonia proliferation is then driven by expression of TCF372. SOHLH1 is regulated by DMRT1 and known to be active in the later stages of spermatogonia mitotic division71. Although in our data, SOHLH1 has its highest expression in oocytes, we see it decreasing as male germ cells progress to spermatogonia (Supp. Table 4). Spermatogonia then execute major transcriptional changes to become primary spermatocytes where they progress through two rounds of meiotic division to become spermatids. This requires a complex set of transcriptional changes, which are known in mice to be coordinated by TCFL5 and MYBL173. In our data TCFL5 has its highest expression in spermatocytes. MYBL1 has a reasonably high τ value of 0.95 but it has higher mean expression in several immune cell types. Outside of immune cells, its highest expression is in spermatocytes (Supp. Table 4). Finally, transition from spermatocyte to early spermatid is known to be initiated by expression of specific TF SOX3073,74. In our data SOX30 expression is highest in spermatocytes and also high in spermatids.

Molecular profiles of senescent cells across human tissues

Cellular senescence is a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest, which can be triggered by various cellular and environmental stresses75,76. At a molecular level, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, particularly p16-INK4a (encoded by the gene CDKN2A), play a crucial role in controlling the initiation and maintenance of cellular senescence77,78. At a cellular level, senescence has been characterized by its unique features such as enlarged cell morphology, increased senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity (SA-β-Gal), formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), and production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases, known as senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)79,80. Nonetheless, the phenotype of cellular senescence is highly variable and heterogeneous, with mechanisms not universally conserved across all senescence programs81–87. The accumulation of senescent cells has been shown to affect various aspects of aging88 and their clearance has been shown to delay various age-related degenerative pathologies89,90.

One of the key challenges in studying senescence is its heterogeneity. Studies using senescent cell culture models have demonstrated this variability, showing that cells can exhibit diverse phenotypes depending on the cell type and the specific inducer of senescence84,85. For instance, SASP has been shown to vary based on cellular context86,87. This in vitro heterogeneity points to the possibility that senescent cells in living organisms are similarly diverse, with distinct cell phenotypes. Compounding the issue, many classical markers of senescence, which were established using cell culture models, have limited utility in vivo. To tackle this issue, researchers have developed guidelines such as the Minimum Information for Cellular Senescence Experimentation in Vivo (MICSE) and the SenNet guidelines for identifying senescent cells in human tissues. These provide recommendations for evaluating senescence markers directly within tissues and in live animal models91.

Given the heterogeneity of senescence markers and the methodological challenges in detecting them, we defined senescent cells based on the expression of CDKN2A and the absence of MKI67 (a cell proliferation marker). To deploy a multi-pronged approach for identification of senescent cells as suggested in SenNet guidelines, we performed a differential expression analysis for genes representing canonical hallmarks of senescence in senescent cells as compared to non-senescent cells across all broad cell types in Tabula Sapiens 2.0. Although our operational definition of senescence drew exclusively on the cell-cycle-arrest hallmark (CDKN2A+ and MKI67−), the resulting differential-expression profile revealed that at least one hallmark-specific gene exhibited the expected direction of change for at least two additional hallmarks in most cell types (Supp. Fig. 10A). Thus, the CDKN2A+ MKI67− population not only satisfies the cell-cycle arrest criterion but also displays molecular signatures consistent with multiple complementary hallmarks, aligning with the framework proposed by SenNet.

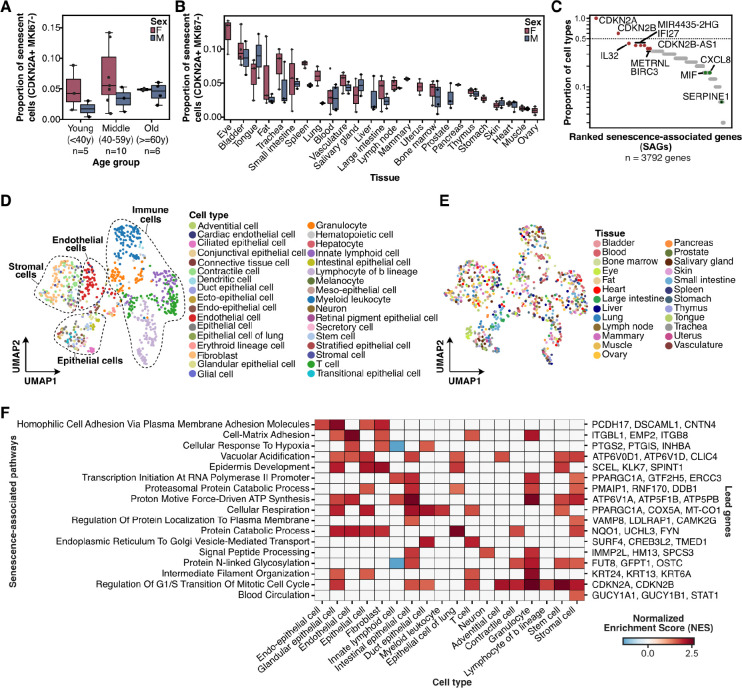

To systematically characterize the phenotype of senescence cells of different cell types across various human tissues, CDKN2A+ MKI67− cells were identified across 25 tissues from 21 donors in the Tabula Sapiens 2.0 dataset (Methods). We detected 48,114 senescent cells (~4.4% of all cells) spanning 145 cell types grouped into 34 broad cell type categories92 (Supp. Fig. 11A & 11B). This represents the largest and most comprehensive study of senescent cells in human tissues to date, providing an unprecedented view of their distribution and diversity across multiple tissue types and cellular contexts. We detected a small increase in senescent cells from medium (40–60y) and old donors (>=60y) as compared to young donors (<40y) (Fig. 4A). As expected, we observed a heterogeneity in the burden of senescent cells across different tissues, with eye, bladder, and tongue containing the highest, and the heart, muscle, and ovary containing the lowest proportion of senescent cells (Fig. 4B). The low burden of senescent cells in the heart, quadriceps muscle, and gastrocnemius has been observed previously93. Comparing the proportion of senescent cells in non-reproductive organs between male and female donors, we observed a slightly higher senescence cell burden in the spleen and lungs from female donors as compared to male donors (Fig. 4B). Next, we looked at canonical markers associated with the cellular senescence phenotype in our dataset. In addition to CDKN2A, previously known senescence-associated DNA damage marker H2AX, SASP regulators such as TGFB1 and NFKB1, and SASP markers such as HMGB1 and TIMP2 were also enriched in senescent cells as compared to non-senescent cells (Supp. Fig. 11C).

Figure 4: Molecular profiles of senescent cells across human tissues.

A) Box plot showing the proportion of senescent cells, defined as CDKN2A+ MKI67− cells, across donors from three age groups. The donors within each age group were split by sex. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. B) Box plot showing the proportion of senescent cells, defined as CDKN2A+ MKI67− cells, across 25 tissues from 21 donors. The donors within each age group were split by sex. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. C) Dot plot showing the cell type prevalence for 3792 senescence-associated genes (SAGs). Cell type prevalence represents the number of cell types where a gene was upregulated in senescence cells as compared to non-senescent cells of that cell type from any tissue. A gene is considered to be upregulated in a cell type if the mean log2 fold-change is greater than 0.5. The top 15 most universal SAGs are highlighted in red, while known senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) genes are highlighted in green. D-E) A Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot showing pseudo-bulked transcriptomes of senescent cells, averaged for donors, tissues, and cell type combinations, and clustered based on the expression of senescence-associated genes alone. D) The pseudo-bulk transcriptomes are colored according to the cell type they represent. E) The pseudo-bulk transcriptomes are colored according to the tissue of origin. F) Heat map showing normalized enrichment scores (NES) for senescence-associated pathways across broad cell types. Enrichment scores were derived from gene set enrichment analysis using ranked enrichment between senescent and non-senescent cells for each broad cell type. Senescent associated pathways were filtered for FDR < 0.05 to retain pathways significantly enriched in at least one broad cell type.

To understand the universality of senescence phenotype, we first identified genes that were upregulated in senescent cells across individual tissues and cell types, and used these genes to quantify the cell type and tissue prevalence of senescence-associated genes (SAGs) (Methods, Supp. Fig. 11B). To find SAGs for individual cell types, we selected genes significantly upregulated in senescence cells of that cell type from any tissue in at least 50% of the donors (log2 fold change > 0.5, adjusted p-value < 0.001, Supp. Table 5). We ranked the 3792 SAGs, which were upregulated across 30 broad cell types in 25 tissues based on their cell type prevalence (Methods, Supp. Fig. 10B). Interestingly, after CDKN2A, CDKN2B was the most universal SAG, which was upregulated in ~60% of the cell types (i.e. 18 out of 30) (Fig. 4C). Surprisingly, SASP markers such as IL6 and IL1B, as well as regulators such as NFKB and TGFBI, did not meet our selection criteria and were therefore not included as SAGs. Among the known SASP factors, the neutrophil-attracting chemokine CXCL8, as well as the pro-inflammatory cytokine MIF, were enriched in senescent cells for ~16% of the cell types (i.e., 5 out of 30), and SERPINE1 was enriched in senescent cells of only two cell types (Fig. 4C). Gene set enrichment analysis of SAGs revealed an enrichment in ontology terms associated with cellular respiration, mitochondrial translation, protein transport, and regulation of apoptotic processes (Supp. Fig. 11D).

The most universal SAGs detected in this study include the gene IL32, encoding for the proinflammatory cytokine Interleukin-32. IL32 h was found to be enriched in senescent cells across 43% of the cell types is present in higher mammals but not in rodents, and has recently been shown to trigger cellular senescence in cancer cells94. This suggests that Interleukin-32 could be an important mediator of paracrine-induced senescence across multiple human tissues (Fig. 4C). Interferon stimulated gene IFI27 was also enriched in senescent cells across 40% of the cell types (Fig. 4C). IFI27 also known as ISG12a is known to possess potent anti-proliferative and tumor suppressive properties and has been reported to be enriched in senescent cells in models of down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease95. Additionally, IFI27 has also been shown to show a strong and sustained expression during TNFα-induced senescence96. Other genes that were enriched across multiple tissues include BIRC3 gene, which not only regulates apoptosis, but also modulates inflammatory signaling, mitogenic kinase signaling, and cell proliferation (Fig. 4C). BIRC3 gene expression has previously been described as a potential survival factor for senescent glioma cells (GBM), where targeting the product of BIRC3 gene was shown to act as a senolytic strategy that triggered apoptosis of GBM cells97.

Collectively, these results point towards the absence of a fully universal senescence program, which has been suggested recently by others81,83. Nonetheless, we sought other broadly expressed markers that might reflect more common senescence features. To gain a more comprehensive view of senescence phenotypes across various cell types and tissues, we clustered the transcriptomes of senescent cells from various donors, tissues, and cell types using only the 3792 SAGs. We observed that this set of SAGs resulted in the senescent transcriptomes clustering together largely by related cell types, and independently of the tissue of origin or the donor (Fig. 4, D and E). This indicates that while there is no universal senescence phenotype, there are shared effects which are broadly shared across certain cell types. To systematically characterize the heterogeneity of senescence phenotypes across all cell types, we identified senescence-associated gene modules co-expressed within the same cell types, tissues, and donors, and summarized enrichment scores for these phenotypes for all cell types (Methods, Supp. Fig. 11B). Seventeen gene expression modules, each representing distinct biological processes, were variably enriched across different cell types (FDR q-value < 0.05, Fig. 4F), and it appears that the various different forms of human cellular senescence can be explained by combinations of these programs, along with some degree of cell-type specific changes.

Gene set enrichment analysis of senescence-associated pathways revealed that senescence programs are notably modulated by cell types and their lineage context. We found that physical cohesion pathways, such as strong homophilic cell-adhesion driven by protocadherin genes such as PCDH17 and DSCAML1, were enriched in senescent barrier and structural cells such as epithelial cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 4F). Similarly, genes associated with epidermal development such as SCEL, KLK7, and SPINT1 were enriched in senescent epithelial cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 4F). Cell-matrix adhesion-related genes, such as ITGB1 and ITGB8, which encode β-integrins, were significantly enriched in senescent epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. (Fig. 4F). Changes in production of cell adhesion molecules including β-integrins have been described in senescent cells before98,99. Interestingly, genes related to transcription initiation at RNA polymerase II promoter pathway, such as PPARGC1A, GTF2H5, and ERCC3, were found to be upregulated in senescent innate lymphoid cells and granulocytes, likely representing a compensatory response to meet the enhanced transcriptional demands of energy-intensive SASP production, metabolic reprogramming, and the maintenance of cellular viability despite growth arrest100 (Fig. 4F). Secretory-pathway pressure was further underscored by the selective enrichment of ER-to-Golgi vesicle transport genes, such as TRAPPC3 and VCP, in senescent intestinal epithelial cells and signal-peptide processing genes, such as IMMP2L and HM13, in senescent neurons and granulocytes. Together with the strong proteasomal and general protein-catabolism scores seen in granulocytes, lung epithelium, and stromal cells, these data reaffirm the centrality of proteostatic stress in senescence101,102.

We found that metabolic rewiring pathways were variably enriched in senescent cells across a wide variety of cell types. Genes associated with proton motive force-driven ATP synthesis as well as broader cellular respiration, such as ATP6V1A, ATP5F1B, MT-CO2, and COX7A2 were enriched in senescent cells of intestinal epithelium, myeloid leukocytes, and stem cells, echoing mitochondrial dysfunction that couples bioenergetic decline to SASP induction103,104 (Fig. 4F). These results align with the growing appreciation that senescent cells can up-regulate oxidative phosphorylation to sustain the energy-intensive senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)105,106. Mitochondrial maintenance thus appears not to be a bystander but an active participant across immune, epithelial, and progenitor compartments. Genes involved in hypoxia responses such as PTGS2, PTGIS, and INHBA were predictably enriched in endothelial and fibroblast populations that dwell in oxygen-gradient niches.107 (Fig. 4F). Vacuolar acidification associated genes such as ATP6V0D1 and ATP6V1D were enriched concurrently in endothelial, epithelial, stromal and stem cells, reinforcing that enlarged, hyper-acidic lysosomes are a hallmark of senescence, and their prominence across both differentiated and progenitor cell types further cements the universality of lysosomal remodeling in senescence108. Lymphoid cells showed an enrichment for the G1/S cell cycle arrest, with increased CDKN2A and CDKN2B enrichment paralleling the accumulation of p16⁺ immune cells that evade clearance during ageing. In contrast, myeloid cells showed high MiDAS and proteasome activity related genes, implying a hyper-metabolic, SASP-potent phenotype distinct from the quiescent lymphoid state (Fig. 4F).

Collectively, we discovered distinct and cell type-specific fates for these cells that undergo cell cycle arrest. This constellation of pathways underscores that cellular senescence is a multifaceted state combining cell-cycle arrest with strategic rewiring of adhesion, metabolism, proteostasis, and organelle function, tailored to each cell types’s role in tissue homeostasis and age-related pathology. Our results show that while there is not a single type of senescence, there are broad programs shared by several classes of cell types across tissues.

The impact of sex on gene expression across tissues and cell types

With the comparative sex information from male and female donors in the Tabula Sapiens 2.0 dataset, we systematically investigated differences in gene expression across a wide range of cell types. Sexual dimorphism in gene expression has been well-documented at the tissue and species level109–113, with implications for differential disease susceptibility, drug responses and biological processes between males and females114–118. These differences are influenced by variations in sex chromosomes, hormonal signaling, transcription factor activity, and environmental influences119. One classic example of sex-dependent gene expression is the XIST gene120, which plays a key role in X chromosome inactivation in females, ensuring dosage compensation between sexes. Other X-linked genes, such as DAX1121, KDM6A122 exhibit sex-specific expression patterns that impact processes like histone modification, gene regulation, and reproductive tissue function. Y-linked genes such as SRY121 and TSPY123, are crucial for male sex determination and spermatogenesis respectively. These genes are exclusively expressed in males. Recent studies also underscore tissue-specific gene expression contributing to sex differences. For example, genes like CYP3A4 and STAT3 are more highly expressed in females in the liver, affecting drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics124. Additionally, LEP, with higher expression in females, regulates energy balance, appetite, and fat distribution125, while differences in PPARG expression between sexes influence immune responses, including the regulation of inflammation and T cell differentiation, in addition to its roles in adipogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism126,127.

Despite progress in understanding sex effects on gene expression across tissues, gaps in understanding remain at the cellular level, particularly regarding variability within cell types. We examined the prevalence of sex-biased gene transcripts across 23 donors, 12 tissues and 20 broad cell type groups from Tabula Sapiens 2.0 datasets (Methods, Supp. Fig. 12). Out of a total of 61,852 gene transcripts evaluated, we identified a diverse set of sex-biased genes varying across different cell types and tissues. Sex-biased genes that are specific to tissue-cell type resolution partially overlap with those identified at the tissue resolution and are almost equal in number in male and female (Fig. 5A). These sex-biased genes showed a skewed pattern of tissue-cell type sharing (Fig. 5B), which chromosome X and Y-related genes such as UTY, RPS4Y1, XIST, LINC00278, EIF1AY and DDX3Y were among the most shared across tissue-cell type pairs, consistent with the pattern found in Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project at tissue resolution117.

Figure 5: Sex-biased gene expression across tissue-cell types.

A) Bar graphs displaying the number of sex-biased genes identified in the Tabula Sapiens 2.0, at both the tissue resolution and tissue-cell type resolution. Top: the total number of sex-biased genes across tissue-cell types in Tabula Sapiens 2.0, and overlap with sex-biased genes found at the tissue resolution. Bottom: The proportion of male- and female-enriched genes identified at the tissue-cell type level, and displayed for each tissue. B) Top: A bar plot showing the log-transformed number of sex-biased protein-coding genes and the extent to which they are shared across tissue-cell types. The number represents the tissue-cell types sharing that gene, with values greater than the indicated threshold. Middle: Heatmaps showing the distribution of gene types (e.g., autosomal-coding, X/Y-linked) alongside the number of tissue-cell types sharing them. Bottom left: The distribution of log-transformed fold changes (logFC) for male- and female-enriched genes, grouped by tissue-cell type sharing. Bottom right: A detailed gene list for the numbered regions from the heatmap. C) Clustering heatmap of Kendall correlations for sex-biased gene expression across major cell types. The inner bar denotes the specific cell type, while the outer bar represents the tissue of origin. The clustering highlights patterns of similarity in sex-biased gene expression between cell types, revealing which tissues and cells share similar sex-specific expression profiles. D) Distribution of concordance scores for differentially expressed genes, categorized by autosomal-coding, X/Y chromosome-linked, and mitochondrial genes. E) Scatter plot showing the mean logFC for female- and male-enriched genes across cell types. The size of the dots represents the number of sex-biased genes identified in each tissue-cell type. F) Bubble plot of representative ontology terms for major cell types. The bubble size corresponds to the adjusted p-value of the enriched terms. The color coding for cell types and tissues is consistent throughout the figure.

Studies on sex differences using bulk tissue GTEx data have revealed small but statistically significant effects of sex on gene expression, driven by sex chromosomes and hormones across various tissues, and suggest that sex correlates with tissue cellular composition117. Analysis of sex differences within Tabula Sapiens also reaches similar conclusions at both the pseudobulk tissue and cell type level (Supp. Fig. 13). Notably, we observe marked differences in the cell-type specificity of these mechanistic categories. Y-linked genes (e.g. DDX3Y, UTY) exhibit robust and consistent male-biased expression across many cell types, reflecting their strict male specificity and the lack of dosage compensation on the Y chromosome (Supp. Fig. 13A). Interestingly, TBL1Y, which has an X-linked homolog (TBL1X), shows variable male-biased expression across cell types. This likely indicated cell-type-specific regulation and partial redundancy with TBL1X, which escapes X-inactivation in some contexts128. This identification highlights the complexity of Y-linked gene expression beyond binary sex specificity. Some additional Y-linked genes such as OFD1P12Y, XGY1, and GYG2P1 are annotated as pseudogenes, and showed inconsistent male-biased expression across cell types, probably due to their non-coding nature. X-inactivation escapees (e.g. XIST) show consistent female-biased expression patterns across a wide range of cell types. However, consistent with previous reports128, we also observe variability in escape status across cell types, indicating the dynamic nature of XCI escape, and its contribution to both consistent and cell-type-specific sex-biased expression (Supp. Fig. 13B–C). Hormone-responsive genes exhibit more cell-type specific sex-biased expression. In particular, we observed that androgen-responsive gene sets are enriched for male-biased expression in specific cell types, including bladder transitional epithelial cells, bone marrow hematopoietic cells, and bladder myeloid leukocytes. In contrast, estrogen-responsive gene sets were enriched for female-biased expression in cell types such as heart fibroblasts, muscle myeloid leukocytes, and others. This suggests that hormone signaling drives localized sex differences, in contrast to the broader, more consistent effects of Y-linked genes and X-inactivation escapees (Supp. Fig. 13D–E). We also identified the tissue and cell type specificity of expression of sex-biased transcription factors (Supp. Fig. 13F).

To further investigate X chromosome inactivation (XCI), we collected sex-differentially expressed genes at an FDR 1<% across tissues and cell types. We then curated a list of XCI-related genes from past study128, which classified X-linked genes into three categories: escape, variable, and inactive with respect to XCI status. By intersecting our significant sex-differential genes with these annotated XCI categories, we observed that genes known to escape XCI are significantly enriched among female-biased genes (Supp. Fig. 14). This trend was consistent at both the tissue and cell-type levels. These results support the role of XCI escapees in shaping female-biased expression and align well with previous findings from bulk RNA-seq datasets117,128.

The bulk nature of GTEx data poses challenges to identify cell type-specific effects. A significant limitation is that bulk gene expression averages out cell type-specific differences, masking the heterogeneity within tissue samples and resulting in small effect sizes that may obscure important cell type-specific variations129. Therefore, we compared the sex-biased genes identified from Tabula Sapiens with those from the GTEx project to identify both congruences and disparities. Tabula Sapiens has a greater number of gene transcripts (61,852 transcripts) compared to GTEx (35,431 transcripts). Our comparison revealed that 38.2% of differentially expressed (DE) genes identified in GTEx were also detected in the Tabula Sapiens dataset across 8 tissues common to both projects, although the overlap varied by tissue (Supp. Fig. 15A–C). Notably, 72.3% of chromosome X-linked DE genes identified in GTEx were also found in Tabula Sapiens, along with an additional 254 chromosome X-linked genes (Supp. Fig. 15D). Interestingly, effect sizes for X chromosome genes identified in Tabula Sapiens were generally significantly larger than those reported by GTEx, with the notable exception of XIST (Supp. Fig. 15D). Additionally, our single cell analysis revealed more ubiquitous sex dependent effects than seen in GTEx; for example, TSIX was identified in the bulk GTEx data as sex-dependent in only a few tissues, but was sex dependent in nearly all Tabula Sapiens tissues (Supp. Fig. 15D). Interestingly, sex dependent gene expression differences are clearly shared across related cell types independent of the tissue of origin. This can be seen by measuring the correlation of differential gene expression across cell types, highlighting the role of cell type in driving gene expression patterns (Fig. 5C). In comparing this single cell analysis with the bulk GTEx data, there is agreement in the correlation heatmap of sex-biased gene expression when focusing on tissue-specific differentially expressed (DE) genes, but the tissue-cell-type-specific analysis from Tabula Sapiens revealed a greater overlap of DE genes across tissues. This overlap further indicates that cell type-specific DE genes are shared across tissues, suggesting that sex bias is primarily driven by cell type specificity rather than tissue-level differences (Supp. Fig. 15E).

In addition to the recognition of sex-biased genes residing on the X and Y chromosome shared across more than 80 tissue-cell types, we also identified sex-biased protein-coding genes on autosomes. Notably, several genes, including NABP1, HSPA1B and HSPA1A, emerged as the most prevalent sex-biased genes across tissues such as vasculature, bladder, fat, bone marrow, as well as in immune cells such as myeloid leukocyte and T cells, and stromal cells such as contractile cells and fibroblast (Supp. Fig. 16A). Though the effect size for these genes were relatively small (Fig. 5B), they play ubiquitous roles in cellular signaling, hormonal regulation, immune response, and cellular stress responses. For example, HSPA1A is one of the heat shock proteins (HSPs), identifying as a lower concentration in female vasculature and potentially indicating higher risk in atherosclerotic disease130. CTBP1-AS, a corepressor of androgen receptor, is generally upregulated in prostate cancer in males131, while BCL6 in male has been associated with maintaining sex-dependent hepatic chromatin acetylation, with a trend of overt fatty liver and glucose intolerance in males132. In contrast, genes such as CIRBP, ABCA5 and HLA-DPB1 were the most prevalent genes enriched in females. Other genes with large effect sizes, such as LCN2, PTGDS, RNASE1 were also enriched in females (Fig. 5B). HLA genes play a crucial role in immune responses, and recent studies suggest they contribute disproportionately to sex biased vulnerability in immune-mediated diseases, such as autoimmune disorders133–135. Additionally, sex differences have been linked to the extent to which HLA molecules influence the selection and expansion of T cells, as characterized by their T cell receptor variable beta chain136. Adipose LCN2 is frequently enriched in females, where it acts in an autocrine and paracrine manner to promote metabolic disturbances, inflammation, and fibrosis in female adipose tissue137. Conversely, several genes, including SELENOH, USP53, and ZNF618, were upregulated in males but not females, showing high effect sizes and abundance. This distinct expression pattern between sexes suggests that males and females may employ different molecular pathways to regulate key biological processes. The identification of these shared and significantly affected genes underscores their potential impact on sex-specific traits and disease susceptibilities. Furthermore, a density plot of concordance score across different gene types showed that chrY and chrX genes exhibit the most consistent sex effects, while mitochondrial genes demonstrated the least concordance (Fig. 5D, Supp. Fig. 16B).

Given the cell type specificity of sex differential expression, we further investigated which cell types exhibited the greatest variability in sex-based gene expression. Cell types with the largest number of sex-biased genes include myeloid leukocyte, innate lymphoid cell, epithelial cells, and granulocytes in tissues such as bone marrow, vasculature, and blood (Supp. Fig. 16C–D). Scatter plots of effect sizes in female and male donors indicated the highest mean effect size in fat, bone marrow tissues, particularly in stem cells, fibroblast and immune cells, such as lymphocytes and myeloid leukocyte (Fig. 5E). These findings align with previous studies that emphasize the importance of cell-type-specific analyses in uncovering sex differences in gene expression. For example, fibroblasts, which show the highest mean effect size, are known for their crucial roles in tissue homeostasis, processes that can be differentially regulated by sex hormones138,139. Immune cells such as lymphocytes, especially in the fat and bone marrow, reflect known sex differences in immune responses140. To link bulk and single-cell findings, we examined autosomal genes from GTEx that were most strongly co-expressed with X-linked genes and compared them to top-ranking tissue-cell types identified in Tabula Sapiens. These GTEx-derived autosomal gene modules were highly correlated with the TS-inferred sex-biased cell types (Supp. Fig. 17).

We summarized the representative functional enrichment for each cell type between male and female donors (Fig. 5F). In general, pathways are shared by both sexes but can be upregulated in a sex-dependent fashion in a highly cell type specific manner. In females, pathways related to cellular respiration and fatty acid metabolism are enriched in female fibroblast, while immune activity is enriched in granulocyte and T cells. In males, pathways associated with inflammatory response were predominantly enriched in endothelial cells and myeloid leukocytes, while androgen responses were predominantly enriched in epithelial, myeloid leukocyte and hematopoietic cells. These findings suggest that males and females leverage different molecular pathways to regulate key biological processes, which may contribute to sex-specific disease susceptibilities and physiological functions.

Searchable Extended Metadata

The Tabula Sapiens 2.0 also includes de-identified medical records for all donors. These medical records are voluminous (an average of 13 pages per donor, 291 total pages) and the overhead associated with their interpretation is often prohibitive. Therefore, we developed ChatTS (https://singlecellgpt.com/chatTSP?password=chatTS; source code available at https://github.com/Harper-Hua/ChatTS)—a web application powered by a large language model—to facilitate use of Tabula Sapiens for the broader research community.

On the front end, a user asks a question about donors’ medical records. Then, on the back end, an external LLM is prompted to answer this question on a per-donor basis, using free-form text that was manually extracted from each donor’s medical record (including physical, imaging, and laboratory studies, as well as social and medical histories). Results are concatenated and returned as a table which can be downloaded and manually verified (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, we observed that the underlying LLM can interpret charts and offer conclusions that are not explicitly stated in the records (Fig. 6B). For example, when asked which donors have heart disease, the response did not require the explicit words “heart disease” in the medical records, but rather inferred it from symptoms and treatments.

Figure 6. ChatTS web application overview.

A) Schematic representation of the ChatTS web application architecture. B) Screenshot of the application, demonstrating inference based on information in charts.

We benchmarked ChatTS with a GPT-4o backend against 330 manually curated question-answer pairs regarding donor metadata. ChatTS showed satisfactory performance (83.2% agreement with manually curated data), and in many cases, the ChatTS-generated answers were more informative than the manually curated data, Supp. Table 7. Differences between manual and ChatTS answers tended to be related to ambiguities in the questions, their definitions, and information present in the medical records, and not to hallucination.

Limitations of the Study

RNA abundance, while informative, does not fully capture protein levels or post-translational modifications, limiting to some extent inference on functional protein states and short time scale behavior of the cells. Cell type abundances measured by dissociation do not necessarily represent true biological abundance due to differential dissociation effects and because enrichment was performed by compartment (immune, epithelial, endothelial and stromal) to maximize the number of cell types captured. Conversely, very rare cell populations may be missing or due to the requirements of live single-cell RNA-seq, as samples were required to be processed quickly and with consistent methods overnight for each donor. As might be expected of any adult who has lived a full life, none of our donors were perfectly healthy. All donors are missing some tissues due to organ transplantation, which always had a higher priority than our study.

Conclusions

The Tabula Sapiens 2.0, featuring over 1.1 million cells across 28 tissues from healthy donors aged 22 to 74 years, offers a comprehensive multiorgan dataset enabling systematic analysis of rare cell populations, while accounting for technical artifacts and donor-specific variations. Global analysis of transcription factor expression enabled a comprehensive analysis to identify which transcription factors are cell type specific and which are ubiquitously expressed. Collectively, we observe heterogeneous and cell type-specific senescence phenotypes and identify several novel and sometimes contradictory fates for cells that undergo cell cycle arrest. Understanding the diverse senescence phenotypes across different cell types offers promising avenues for developing targeted senolytics, tailored to address age-related diseases affecting specific tissues and cell types. Finally, sex-dependent gene expression analyses provide the beginnings of an understanding which genes and cell types are most strongly sexually dimorphic and the consequent implications for cellular and tissue functions. By comparing male and female gene expression profiles, we identified significant patterns and quantified the impact of sex on gene regulation, contributing to our understanding of biological differences and their consequences for health and disease.

Tabula Sapiens 2.0 is the most comprehensive human cell atlas reference to date, as measured by the breadth of tissues and cell types. The vignettes included in this publication illustrate the kind of exploratory analysis and hypothesis building that such a dataset enables. Following on the previous Tabula projects1,21,141,142, all data is available for the community to continue learning and improving as a reference atlas until we have a deeper understanding of the molecular representation of cell types and cell states. The community found many uses of Tabula Sapiens 1.0, ranging from being a tool to predict potential on target toxicity of drug candidates to being a reference standard used to evaluate bioinformatic tools and train AI models, and we expect that the expanded version described here will only increase such applications. For example, the discovery of cell type specific transcription factor usage will point the way for future biochemical studies to characterize the function of these transcription factors, as will the identification of previously undetected ubiquitous transcription factors which are found in all cell types. We have also already seen the use of Tabula Sapiens 2.0 as a hold out data set to test the zero shot capability of AI models which are trained on Tabula Sapiens 1.0.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests about reagents and other resources used in this work should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Stephen R Quake (steve@quake-lab.org).

Data and code availability

The entire dataset can be explored interactively at the Tabula Sapiens Data Portal143 (https://tabula-sapiens-portal.ds.czbiohub.org/).

The code used for the analysis is available on the github repository for Tabula Sapiens (https://github.com/czbiohub-sf/tabula-sapiens/).

Gene counts and metadata are publicly available from figshare144 and cellxgene143.

The raw data files are available from a public AWS S3 bucket (https://registry.opendata.aws/tabula-sapiens/), and instructions on how to access the data have been provided in the project GitHub.

To preserve the donors’ genetic privacy, we require a data transfer agreement to receive the raw sequence reads. The data transfer agreement is available in the data portal.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

STAR methods

Key resources table

[will be moved here once manuscript is ready, for now please check the file STARmethods_KeyResourcesTable_TabulaSapiensv2.docx]

Organ and tissue procurement

To maintain consistency in the overall Tabula Sapiens dataset, organ and tissue procurement followed the same procedure used in the first phase of the project. Donated organs and tissues were procured at various hospital locations in the Northern California Region through collaboration with a not-for-profit organization, Donor Network West (DNW, SanRamon, CA, USA). DNW is a federally mandated organ procurement organization (OPO) for Northern California. Recovery of non-transplantable organ and tissue was considered for research studies only after obtaining records of first-person authorization (i.e., donor’s consent during his/her DMV registrations) and/or consent from the family members of the donor. However, the pancreas from donor TSP9 was provided by Stanford University Hospital under appropriate regulatory procedures. The research protocol was approved by the DNW’s internal ethics committee (Research project STAN-19–104) and the medical advisory board, as well as by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University which determined that this project does not meet the definition of human subject research as defined in federal regulations 45 CFR46.102 or 21 CFR 50.3.

Tissues were processed consistently across all donors. Each tissue was collected, and transported on ice, as quickly as possible to preserve cell viability. A private courier service was used to keep the time between organ procurement and initial tissue preparation to less than one hour. Single cell suspensions from each organ were prepared in tissue expert laboratories at Stanford and UCSF. For some tissues the dissociated cells were purified into compartment-level batches (immune, stromal, epithelial and endothelial) and then recombined into balanced cell suspensions in order to enhance sensitivity for rare cell types as described further below.

Tissue preparation protocols and cell suspension preparation protocols

The methods for tissue dissociation and staining of cell suspensions for bladder, blood, bone marrow, eye, fat, heart, intestine, kidney, liver, lung, lymph node, mammary gland, pancreas, prostate, salivary gland, skeletal muscle, skin, spleen, tongue, trachea, thymus, uterus, and vasculature are described in the methods section of the Tabula Sapiens1.

Inner Ear - Initial tissue preparation protocol

Whole organ utricles were collected from organ donors. Bilateral utricles were harvested from organ donors as previously described145–147. Briefly, a post-auricular incision was made followed by a modified transcanal approach to expose the middle ear. The tympanic membrane, malleus and incus were removed while keeping the stapes in situ. To expose the vestibular organs, the bony covering of the vestibule was thinned using a diamond burr on low speed, the stapes footplate removed, and the oval window widened. The utricle was harvested from the elliptical recess and placed in PBS on ice for single-cell RNA sequencing analysis.

Inner Ear – 10x Genomics sample preparation

Utricles from organ donors were placed in DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific/Gibco, 11–039-021) with 5% FBS during transport to the laboratory. Tissues were then washed twice in DMEM/F12 and any debris and bone microdissected away. The whole utricle was then incubated with thermolysin (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma Aldrich, T7902) for 45 min at 37°C. Next, the whole utricles were digested using Accutase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 00–4555-56) for 50 min at 37°C and single cell suspension was obtained by trituration using a 1 mL pipette. Single cell suspension was achieved using a 40 μm filter. DMEM/F12 media with 5% FBS was used for this step. Cells were then centrifuged at 300g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended in media. Number of cells per microliter was quantified using a hemocytometer

Large and Small Intestines – Initial Tissue Preparation Protocol

Segments of the small intestine (duodenum and ileum) and large intestine (ascending and sigmoid colon) were transported on ice to Stanford University. Upon arrival, the tissues were sectioned into approximately 5 cm segments and rinsed multiple times with 35 mL of ice-cold PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific 10010023) to remove residual lumen contents. The tissues were then opened with the mucosal side facing up, and 10 mL of ice-cold PBS was injected using a 21G needle. Mucosal blebs were then dissected, minced into approximately 2 mm pieces, and digested in 10 mL of digestion medium (DMEM/F12: Thermo Fisher Scientific 12634010, 1x Penicillin-Streptomycin-Neomycin: Sigma P4083, 1x Normocin: Invivogen ant-nr-2, 1x HEPES buffer: Corning 25–060-CI, 1x Glutamax: Thermo Fisher Scientific 35050061, and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632: MedChem Express HY-10583) containing Collagenase III (300 U/mL: Worthington Biochemical Corporation LS004182) and DNase I (200 U/mL: Worthington Biochemical Corporation LS002139) at 37°C for 90 minutes. During digestion, the mixture was pipetted every 15 minutes with a 10 mL pipette to facilitate tissue breakdown. After digestion, 30 mL of intestinal wash buffer (HBSS: Corning 21–022-CV, 2% FBS, 1x Penicillin-Streptomycin-Neomycin , 1x Normocin, and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632) was added to the suspension, which was then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of ACK lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific A1049201) to lyse red blood cells and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. The suspension was centrifuged again, and the pellet was resuspended in intestinal wash buffer with DNase I, then filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer (Miltenyi Biotec 130–098-463). The final cell suspension was counted using trypan blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific 15250061) and adjusted to a concentration of 106 cells/mL for direct single-cell analysis using the 10x Genomics platform or flow sorting.

Ovary - Initial tissue preparation protocol

Ovaries were finely dissected to remove surrounding tissues. Ovaries were gently chopped using a razor blade and then transferred to a 50 mL Falcon™ conical tube with a final volume of 30 mL 2 mg/mL collagenase type IV in DMEM/F12. Tubes were incubated at 37 °C shaking at 250 rpm for 20 min then centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was aspirated and 30 mL 0.25 % trypsin-EDTA was added. Tubes were incubated at 37 °C shaking at 250 rpm for 20 min then centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and the tissue was quenched with 30 mL 10 % FBS in DMEM/F12. Using a P1000, tissue was gently triturated to generate a single cell suspension. The cell suspension was filtered using a reversible 37 um sieve. The sieve was rinsed with 1 mL quench buffer (<37 um filtered flow through) and then flipped and placed in a new tube for rinsing with 1 mL quench buffer (>37 um unfiltered mature oocyte pool).

Single oocytes and/or follicles were handpicked from the cell suspension under magnification (2 to 6X) on a dissection microscope using an EZ-Grip pipette with a 125 um EZ-Tip and washed in 0.04% BSA-PBS. Single oocytes and/or follicles were then transferred in 0.6uL of 0.04% BSA-PBS to individual wells in a 96-well plate containing a lysis buffer master mix. Lysed oocytes and/or follicles were stored at −80 °C to enhance lysis prior to cDNA and sequencing library construction. Nine follicles, which were not dissociated into single-cell suspensions, represent the bulk transcriptomes of entire ovarian follicles.

Ovary - FACS/SS2 sample preparation

Filtered cell suspensions were centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min, aspirated, and washed in FACS Buffer (2 % FBS-PBS). The following antibodies were used at a 1:200 dilution in FACS Buffer: EPCAM-PE (Biolegend, 324206); CD45-FITC (Biolegend, 304038); CD31-APC (Biolegend, 303116). The cell suspensions were incubated 1 hr on ice for staining, then washed 3 times. Prior to sorting, Sytox Blue was added at a 1:1000 dilution (ThermoFisher, S34857) and live, single cells were sorted for EPCAM+ (oocytes), CD45+ (endothelial), CD45+ (immune), EPCAM−/CD45−/CD31− (stromal/granulosa) populations into 384-well lysis buffer plates following color compensation. Plates were stored at −80 °C until processing for sequencing.

Stomach – Initial Tissue Preparation Protocol

Ligated whole stomachs were transported on ice to Stanford University. Upon arrival, a 6×3cm longitudinal strip was cut from the anterior aspect of the stomach antrum, 6 cm proximal to the pylorus. Stomach tissue was first rinsed in 1X PBS to remove clots and debris, and blotted dry to remove excess mucus. The tissue was then dissected, separating the mucosa/submucosa layer from the muscularis/serosa layer, and the layers were then weighed. Each layer was digested separately to maximize viability. The mucosa was first incubated with 5mM EDTA in HBSS buffer without Ca2+ for 10 minutes on a shaker at 37 °C (x3), with washes and collection of epithelial cells. After this, both mucosa and muscularis layers were minced with fine sharp scissors in digestion media with 0.8 mg/ml collagenase Type IV Worthington (Sigma) and 0.05 mg/mL DNase I (Roche) (10mL per 2.5 gram of tissue). Two serial mucosa digestion were done in an orbital shaker (300 rpm) at 37 °C, 20 min each, and for muscularis 40 min each (vortexing halfway). Digestions were stopped with cold R10-EDTA, and cells were filtered from undigested tissue, washed and then stained with CD45-PE (Biolegend, #304007) for cell counting and sorting. The Mucosa digestion and EDTA epithelial fraction were combined and DAPI stained (Thermofisher Cat# D1306). Live DAPI−, CD45+ and CD45− cells were then FAC-sorted on a BD Aria. Sorted cells from mucosa and muscularis were mixed back together at a 70:30 CD45+ to CD45− ratio, and used for 10X single-cell RNA sequencing.

Testis- Initial Tissue preparation protocol

Testis tissues were dissected out from the tunica and lightly dissociated and minced using sanitized surgical forceps and razor blade. Two to three pieces of 0.5g testis tissue was placed in a 50mL Falcon tube with 10mL prewarmed collagenase solution at 32 °C (1 mg/mL collagenase I (Worthington Biochemicals #LS004196), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5ul/mL DNaseI (50mg/mL stock, Worthington Biochemicals #LS002139) in PBS). Testis tissue was first dissociated by vigorous pipetting and then incubated at 32 °C for 8 minutes with 2–3 times pipetting during the incubation to resuspend cells. After incubation, cells were dissociated again at room temperature by vigorous pipetting for 2–4 minutes. Cells were spinned down at 250×g for 5min at room temperature and then the supernatant was removed. The dissociation steps were repeated one more time before 5mL of TripLE (Thermo Fisher Scientific #12604013) plus 1uL/mL DNaseI (50mg/mL stock) was added to the dissociated cells and incubated at 32 °C for 15 min with pipetting every 5 min. Cells were then washed with 30mL PBS and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer and then a 40 μm cell strainer. Cell number was recorded before cells were spin down at 250×g for 10min. Then the supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended at 1000 cells/uL for cell capture in microfluidic droplets with the 10x Genomics platform.

Testis – FACS/SS2 sample preparation

After cells were spun down at 250×g for 10min and after passing the cell strainer, cells were washed once in 3mL FACS buffer (2%FBS (Thermofisher #A5670701), 1mM EDTA (Invitrogen #AM9260G) in PBS(Gibco #10010023)), spin down at 25xg for 5min, and resuspended in 400uL of FACS buffer. Antibodies cocktail (2 μL of EPCAM-PE (Biolegend, 324206), 2uL of CD45-FITC (Biolegend, 304038), 2uL of CD31-APC (Biolegend, 303116)) was added to the cell suspension, and cells were incubated on ice for 30min, with mix by tapping every 10min. After incubation, cells were washed twice with 2mL FACS buffer and spin down at 250×g for 5min, and resuspended in 1mL FACS buffer. Sytox blue was added before sorting.

Thymus– Initial Tissue Preparation Protocol

The tissue dissociation and staining of cell suspensions for thymus is described in the methods section of the Tabula Sapiens1. Our analysis revealed the presence of cells originating from fat and intra-thymic lymph nodes among those attributed to the thymus, likely due to difficulties in tissue collection caused by the natural involution of the thymus with age. Consequently, we excluded the thymus from our analysis of sex-biased gene expression.

10x Genomics protocol

10x Genomics kits used were Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ Kit v3.1 or Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5ʹ Kit v2. The protocols provided by the manufacturer were followed. In general, two 10X Chromium channels were loaded per tissue with 7000 cells, with the goal of obtaining data for 10,000 viable cells per tissue.

Organ and cell coverage

Our goals were to characterize the gene expression profile of 10,000 cells from each organ and detect as many cell types as possible. As explained in detail for each organ, about ⅔ of the organs employed a MACS based enrichment strategy, either to balance cell types between four compartments; epithelial, endothelial, immune, and stromal. This ensured abundant cell types in one compartment did not mask rare cell types in another. Two 10x reactions per organ were loaded with 7,000 cells each with the goal to yield 10,000 QC-passed cells. Four 384-well Smartseq2 plates were run per organ. In most organs, one plate was used for each compartment (epithelial, endothelial, immune, and stromal), however, to capture rare cells, some organ experts allocated cells across the four plates differently. The use of two 10x reactions enabled some flexibility to distinguish in the data the anatomical position of the sample or allowed enrichments other than epithelial, endothelial, immune, and stromal. It also served as insurance against losing an entire organ due to a clog of the 10X chip.

Flow Sorting

Details of the sorting can be found in Tabula Sapiens1. Briefly, after dissociation, the single cells from each organ and tissue that were destined for plates were isolated into 384 plates via FACS. On some cell suspensions destined for 10x tissue compartments were enriched by FACS to balance the cell types as described in the tissue specific methods. Most sorting was done with SH800S (Sony) sorters. The last column of each 384 well plate was intentionally unsorted so that ERCC’s controls could be used as a plate processing control. Immediately after sorting, plates were sealed with a pre-labelled aluminum seal, centrifuged, and flash frozen on dry ice to ensure full cell lysis. Typical sort times were 4 to 9 minutes per 384-well plate.

Smart-seq2 Protocol

Plate-based sequencing of tissues used the 384 plate modification of Smart-seq2148 as described in Tabula Sapiens1 and Tabula Muris Senis142.

Smart-seq2.5 Protocol