Abstract

Background/objective

Plate failure, including bending, is a critical issue in orthopedic fracture fixation, with clinical failure rates of 3.5%–19%, burdening patients and healthcare systems. Preclinical ovine models have observed similar plate bending due to overloading. Finite element (FE) models could be capable of predicting failures but lack in vivo loading data for validation. The AO Fracture Monitor is an implantable sensor that can continuously track implant deformation, offering a proxy for implant loading and the potential to bridge this gap. This study aimed to preclinically validate an FE simulation methodology for predicting overloading bending of locking plates in an ovine tibia osteotomy model using AO Fracture Monitor data, emphasizing its potential for clinical translation.

Methods

Tibiae of eleven sheep with osteotomy gaps (0.6 – 30 mm) were instrumented with stainless steel or titanium locking plates equipped with AO Fracture Monitors in a prior study. Residual plate bending angles were measured using co-registered CT scans at 0 and 4 weeks post-operation, with bending defined as ≥ 1°. Animal-specific FE models, incorporating virtual AO Fracture Monitors and non-linear implant material properties, were developed to determine sensor signals at the construct's yield point. In vivo sensor signals were compared to the virtual plasticity threshold to predict CT-based residual bending outcomes.

Results

Within 4 weeks, plate bending angles ranged from 0.4° to 10.4°, with overloading bending observed in 6 animals. The FE methodology correctly predicted bending/no-bending outcomes in 9 of 11 animals, achieving 100% sensitivity and 60% specificity.

Conclusions

This sensor-validated FE methodology robustly predicted in vivo plate bending, offering a promising tool for reducing implant failure. These findings highlight the methodology's ability to detect clinically relevant bending outcomes. By integrating real-time loading data, it supports the development of personalized rehabilitation strategies, enhancing clinical outcomes in fracture fixation.

The Translational Potential of this Article

This validated FE methodology, leveraging AO Fracture Monitor data, can be adapted for human use to tailor rehabilitation protocols immediately post-surgery and provide real-time feedback to patients and clinicians if loading exceeds safe thresholds. This approach could minimize implant failure, reduce revision surgeries, and enhance patient recovery.

Keywords: Fracture fixation, Plate bending, Sensor, Validation

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Fracture fixation through internal plating has revolutionized orthopedic surgery, yet the persistent challenge of plate failures—including bending and breakage—continues to impose a substantial burden on patients and healthcare systems worldwide. Clinical studies reported failure rates ranging from 3.5% for mechanically induced failures [1] to as high as 19% for implant-related issues like implant failure [2], with complication rates reaching 53% in complex cases, including 4.3% attributed to hardware malfunction [3]. These failures often occur in weight-bearing bones like the tibia and femur. They can lead to loss of fracture reduction, mal- or non-union, or the loss of stability, necessitating revision surgeries. This increases patient morbidity and healthcare costs significantly. Underlining that, a case study specifically discussed plate bending of lower extremities due to overloading of obese patients [4]. The mechanics of a fixation are pivotal, as insufficient implant stability or excessive loads can cause bending, while prolonged cyclic loading may lead to fatigue-induced breaking—both of which undermine treatment success. Preclinical investigations, such as a study on ovine tibial fracture fixation, a model chosen for its biomechanical similarity to human bone, mirrored the clinical observations, reporting plate bending due to overloading [5]. Similar observations in small animals were described by Morris et al. [6]. These findings underscore the need for predictive tools that can detect the limit of load bearing capacity of fixation constructs, addressing the root causes of implant failure.

Finite element (FE) models have long been utilized to simulate case-specific implant failures, offering valuable insights into potential failure locations based on retrospective clinical data [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. However, their accuracy was limited by the lack of in vivo loading data. Most FE models rely on assumed loading conditions that fail to capture the patient-specific forces, making validation against actual failure events challenging, if not impossible [13]. This gap has constrained the translation of FE predictions from theoretical exercises or forensic analyses, including numerous assumptions to actionable clinical tools, particularly in the context of acute overloading scenarios where bending predominates.

Novel in vivo sensor technologies could help to overcome this barrier. The AO Fracture Monitor was developed as an implantable sensor designed to track healing progression by continuously measuring implant deformation, which diminishes as the callus stability increases and load-sharing shifts to the healing bone [14]. Beyond its primary purpose, it indirectly assesses implant loading, providing real-time biomechanical insights into the fixation construct and the underlying fracture. Unlike traditional diagnostic methods such as X-rays, which offer static, subjective snapshots of healing and expose patients to ionizing radiation, the AO Fracture Monitor delivers continuous, quantitative, dynamic data without invasive follow-ups. Preclinical studies have confirmed its safety and efficacy in monitoring healing, as demonstrated by Windolf et al. [5], while also noting a case where the sensor signal served as a proxy for loading conditions inducing residual plate bending. A recent in vitro investigation has demonstrated that FE models can accurately predict the sensor signals measured by the AO Fracture Monitor, establishing a validated link between virtual simulations and experimental deformation measurements [15]. This synergy suggests that combining continuous sensor data with FE models could enable unprecedented validation of in vivo plate bending, overcoming previous limitations of load estimation.

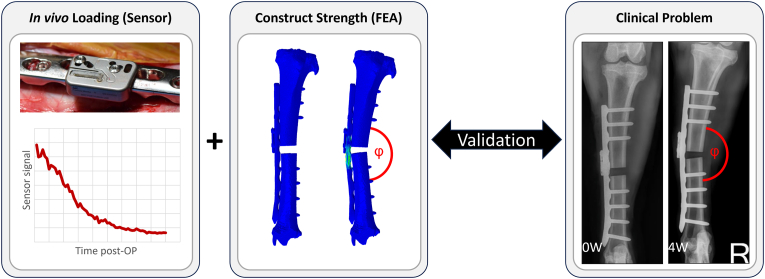

Building on these advancements, the present study integrated this combined approach to investigate residual plate bending resulting from overloading in a controlled preclinical context. Our aim was to preclinically validate an FE methodology for predicting residual plate bending in an ovine tibia osteotomy model, using AO Fracture Monitor data for validation (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that FE models, validated through sensor-derived in vivo loading data, could accurately predict residual plate bending in vivo in this ovine model. This validation aimed to establish a predictive framework for implant mechanics under preclinical conditions. It provides a foundation for clinical translation, enabling sensor-independent, subject-specific predictions to reduce implant failures and optimize outcomes in orthopedic practice.

Fig. 1.

In vivo measured sensor signal (left, [5]) was combined with the animal-specific structural capacity (middle) to predict in vivo plate bending (right, [5]).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Eleven adult female Swiss alpine sheep obtained transverse tibial osteotomies with gap sizes ranging from 0.6 mm to 30 mm and were instrumented with either veterinary stainless steel (5.5 mm, broad, 10 holes, Johnson & Johnson MedTech, Zuchwil, Switzerland) or titanium (4.5/5.0 mm, broad, 10 holes, Johnson & Johnson MedTech, Zuchwil, Switzerland) locking compression plates (LCP), assigned based on the surgical protocol in a previously completed preclinical study [5]. The data used in this study were sourced from a previous pre-clinical study approved by the local authorities (approval number GR 2019_11). No animal experiments were performed to collect data specific for the present study; all analyses were conducted using existing datasets from the prior investigation. The plate working length was kept constant at three empty holes above the fracture gap for all animals. Computer tomography (CT) scans (Revolution EVO, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, United States) of the tibiae were acquired immediately, at 4 weeks and at 39 weeks post-operative with settings of 120 kV voltage, 200 mA current, and 0.625 mm slice thickness, and calibrated to volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) using a density phantom (QRM-BDC/6, QRM GmbH, Moehrendorf, Germany).

2.2. Residual plate bending quantification of pre-clinical dataset

In vivo plate bending angles were calculated as follows. The bone fragments of the operated tibiae were segmented from the CT scans using a global thresholding approach using Amira (v2023, Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). The segmented images were meshed to triangulated surface models. Specific landmarks were selected on the tibia's surface at the anatomical center of the knee and ankle joints, on the tibial tuberosity, and at the near cortex (closest to the plate) and far cortex (opposite side across the fracture gap) directly adjacent to the fracture below the plate, as illustrated in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Material 1. The axis of each fracture fragment was defined by the line connecting the joint landmark to the midpoint between the near and far cortex landmarks. Bending angles were quantified by projecting these axes onto a plane fitted through the four cortex landmarks using least-squares regression, representing the bending plane. The plastic bending angle, defined as residual deformation after elastic recovery, was determined by subtracting the CT-based bending angle at 4 weeks (β) from the immediate post-operative angle (α). Residual bending angles ≥ 1° were classified as in vivo implant plastic deformation. The same was repeated for the 39 weeks follow-up to evaluate whether later plate bending occurred.

Fig. 2.

Determination of bending angles based on two CT follow-up time points, immediate postoperative (left) and 4 weeks follow-up (right) CT scans, respectively. From the respective image stacks (a), the bone fragments were segmented (b), and the angle between the two bone fragments was calculated (c).

2.3. FE modelling

Finite element (FE) models were developed to replicate the in vivo situation for each animal's specific construct configuration using immediate post-operative CT scans (Fig. 3A and B). The two bone fragments were constructed from the segmented contralateral tibia that was mirrored and spatially co-registered to the ipsilateral tibia parts to avoid metal artifacts distorting the density mapping. A virtual osteotomy was created by subtracting a voxel-based rectangular prism, with width matching the gap measured in the CT image, using Amira software. Intraoperative plate pre-bending required for anatomical fit at the distal end of the tibia was replicated on the plate's computer-aided design (CAD) file using Solidworks software (v2022, Dassault Systems, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). Threadless screw CAD surfaces were used to simplify the model without affecting accuracy and positioned based on the CT scans with corresponding lengths [16]. The construct was meshed with Simpleware ScanIP (Synopsys, Mountain View, CA, USA) using on average 656′521 (±141′050) elements, with the element lengths determined based on a mesh convergence study (Fig. 3C, median element edge length 0.96 mm ± 0.12 mm, Supplementary Material 2). Bone material properties were mapped elementwise via an established conversion law [17] from the co-registered BMD-calibrated CT scans of the contralateral tibia to eliminate implant interference. Implant material properties, including elastic and plastic parameters for stainless steel and titanium, were taken from a previous validation study [18]. The AO Fracture Monitor, measuring implant deformation via strain gauges with a millivolt signal, was integrated using the CAD model describing geometry and CT data for positioning within the construct, with properties set as titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V Grade 5, Young's modulus 113.8 GPa, Poisson's ratio 0.342) [19]. Tied interfaces were used between screw inserts of the sensor and plate locking holes, between locking screw heads and the plate holes, between the screw shafts and bone, and between the sensor screws and inserts, respectively. Surface-to-surface contact was defined between fragments and between bone and plate. The construct was aligned in an anatomical coordinate system using the landmarks at the knee and ankle joint centers and tibial tuberosity, with the z-axis being along the tibia's long axis and x-axis perpendicular through the tuberosity [20]. The previously defined four landmarks at the fracture gap cortices were included in the model to be able to measure plate bending analogously with the CT-based analysis described in section 2.2. A coupling constraint linked proximal and distal landmarks to epiphyseal bone surface nodes located within a 2.5 mm radius sphere. The distal reference point was constrained as a Cardan joint, allowing anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) rotation to mimic kinematics, while the proximal point was fixed in all directions except proximal-distal (PD) translation. A 15 mm displacement along the shaft axis, causing fracture gap closure in all but the 30 mm gap case and exceeding physiological compression, ensured the induction of plasticity onset (Fig. 3D). The FE simulations were solved using the implicit solver of Abaqus (v2019, Simulia, Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). Plasticity onset was defined as 0.6% of elements within the plate region between the innermost screws deformed, validated by prior in vitro ovine tibia experiments [15], yielding an animal-specific sensor signal for in vivo residual implant bending prediction.

Fig. 3.

FE modelling pipeline: Exemplary slice of an immediate postoperative CT scan (A), segmented bone with implants and the AO Fracture Monitor (B), finite element mesh, boundary conditions, and fracture gap landmarks (C), and consequent FE result after a complete loading cycle until fracture gap closure (D).

2.4. Validation based on continuous implant load sensor data

The FE-predicted sensor strain was converted to the raw AO Fracture Monitor signal based on a constant factor established in a previous in vitro validation study through four-point bending testing [15]. The AO Fracture Monitor data, originally collected in a prior preclinical study, were used in this study solely to validate FE-predicted plate deformations against in vivo measurements, with the validated models intended for translation towards clinical use without requiring sensor data. The FE-based sensor signals corrected with this factor were used to set a threshold for implant overloading bending. The AO Fracture Monitor continuously recorded implant deformation via strain gauges to capture loading event amplitudes—defined as the difference between local minima and maxima in the signal—processed algorithmically onboard the sensor [5]. Daily maximum loading amplitudes were plotted as histograms, overlaid with an animal-specific plasticity threshold derived from each FE model, reflecting its unique construct. In vivo measured amplitudes exceeding this FE-based threshold indicated predicted in vivo implant overloading bending, which was compared to the actual residual bending status (per the residual bending angle criterion described in 2.2) to evaluate predictive accuracy (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Flowchart to validate the FE predictions against in vivo outcomes to determine sensitivity and specificity.

3. Results

3.1. CT-based bending angles

Bending angles measured between the 4-week follow-up and the immediate post-operative CT scans ranged from 0.4° to 10.4° across all animals. Using the threshold of 1° to define implant overloading bending, the plates of six animals were determined as plastically bent, with angles exceeding this value, ranging from 2.1° to 10.4°. The remaining five animals showed plate bending angles below 1° and were classified as non-bent outcomes. The bending outcomes at the 39-week follow-up were the same as the 4-week results for each animal with the mean ± standard deviation of the differences being 0.02° ± 0.2°. All animals expect the one with the 30 mm gap achieved bony union, confirmed by mechanical testing, while the 30 mm gap exhibited non-union, contributing to sustained high implant loading and consequent bending [5].

3.2. Residual bending prediction based on combined FE analysis and continuous in vivo sensor data

The comparison of the in vivo AO Fracture Monitor sensor amplitudes, representing maximal daily load event magnitudes with the animal-specific FE-based yield threshold criteria indicated that eight animals exhibited sensor amplitudes exceeding their respective yield thresholds. No residual bending was predicted for the other three animals. An exemplary histogram depicting the daily maximum amplitudes for one animal is shown in Fig. 5. The complete set of histograms, detailing the amplitude for all eleven animals, is provided in the Supplementary Material 3–13.

Fig. 5.

Histogram of the maximum daily in vivo sensor signal amplitudes of a representative animal (blue). The animal-specific FE-based yield threshold is indicated with a dashed line (red). Amplitudes above the threshold indicate residual implant bending. The animal information, including CT-based bending angle, is listed in the figure legend.

3.3. Validation of FE and sensor predictions against CT-based implant overloading bending

The comparison of the CT-based in vivo residual implant bending with the bent/not bent status predictions from the combined FE and continuous sensor data showed correct bending outcome for 6 animals and correct no-bending outcome for another 3 animals (Table 1). For the remaining two cases, a false positive outcome was predicted. These results yielded a specificity of 60% and a sensitivity of 100% (Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Summary of all investigated animals including implant material, osteotomy width, CT-based in vivo measured residual bending angle, resulting bending/no-bending status, and the predicted bending/no-bending status, determined as the presence of a maximum daily signal amplitude above the plasticity threshold from the animal-specific FE models.

| Animal | Material | Gap size [mm] | Angle (4 weeks) [°] | CT-based bending | In vivo sensor signal above FE yield threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 519030 | Stainless steel | 0.6 | 0.7 | No | No |

| 519031 | Stainless steel | 2.0 | 0.4 | No | Yes |

| 519032 | Stainless steel | 10.0 | 10.4 | Yes | Yes |

| 519042 | Titanium | 0.6 | 0.9 | No | No |

| 519043 | Titanium | 2.0 | 0.6 | No | No |

| 519044 | Stainless steel | 10.0 | 3.0 | Yes | Yes |

| 519049 | Titanium | 4.0 | 2.1 | Yes | Yes |

| 519050 | Stainless steel | 6.0 | 0.3 | No | Yes |

| 519051 | Stainless steel | 4.0 | 2.2 | Yes | Yes |

| 519052 | Titanium | 6.0 | 2.0 | Yes | Yes |

| 520001 | Stainless steel | 30.0 | 5.0 | Yes | Yes |

Fig. 6.

Confusion matrix of the actual CT-based in vivo plate bending status (columns) and the predicted bending status based on the animal-specific FE-based sensor thresholds and in vivo sensor signals (rows) for eleven animals. The predictions achieved a sensitivity of 100% (6/6) and a specificity of 60% (3/5).

4. Discussion

The present study successfully demonstrated the predictive capability of a subject-specific FE methodology validated with continuous implant load sensor data from the AO Fracture Monitor to identify in vivo implant overloading bending in an ovine tibial fracture model. Residual plate bending, defined as an angle ≥ 1°, was accurately predicted in 9 out of 11 animals, yielding a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 60%. This high sensitivity ensured reliable detection of all bending instances. The lower specificity reflects a conservative prediction, leading to overestimation of overloading bending risk in two cases. In clinical terms, this balance is advantageous: accurately identifying all actual bending cases is paramount, and false positives, while less desirable, are tolerable as they err on the side of caution. Measured bending angles ranged from 0.4° to 10.4°, with residual deformations consistently occurring within the first 4 weeks post-operation, as confirmed by the absence of further failures observed in CT data collected at 39 weeks. This temporal pattern strongly suggests that overloading, not fatigue failure, drove plate deformation. Insufficient time elapsed for cyclic fatigue in this early healing phase. In clinics, plate bending occurs less frequently than screw loosening or fatigue failure (i.e., plate breaking), with the two latter being more common modes of implant failure due to prolonged cyclic loading [21]. Nevertheless, the FE models effectively predicted in vivo construct behavior in this study by validating the approach against a preclinically observed plastic bending due to overload. With validated models established, future validation steps could incorporate the fatigue life of implants. This would expand their predictive scope to cover dominant clinical failure mechanisms of implants.

The AO Fracture Monitor proved essential to this validation, providing continuous, real-time loading data that enabled in vivo validation of the FE models. Unlike traditional static assessments, this sensor offered invaluable insights into dynamic implant deformation, capturing loading event amplitudes that could be directly compared to animal-specific plasticity thresholds. While critical for validating the models in this preclinical study, the AO Fracture Monitor would not be necessary in applying this prediction methodology in clinical practice. Instead, the validated FE models could assess construct strength immediately post-surgery, guiding subject-specific rehabilitation protocols based on evidence, rather than the eminence-based approaches prevalent in the current clinical setting, without requiring continuous monitoring devices. However, it is well known that patients often do not adhere to prescribed weight-bearing protocols, so having data to indicate whether a patient is loading below or above a critical threshold could still be critical for ensuring safe rehabilitation while avoiding implant failures.

The systematic ground-up validation approach—from material property testing and isolated sensor signal calibration to in vitro construct validation—was critical to achieving this predictive accuracy. Material properties of the implants and bone, derived a previous study [8] and mapped on the bone via an established conversion law [7], ensured realistic simulation of the construct's mechanical behavior. The conversion law between experimental and virtual sensor signals, validated in vitro with a concordance correlation coefficient of 0.89 [15], allowed the combination of the FE model results with continuous in vivo sensor data into residual bending predictions. This multi-step validation underscores the robustness of the methodology, culminating in its ability to align FE-predicted plasticity onset (plastic deformation in 0.6% of the plate volume between the two innermost screws) with CT-measured residual implant bending (≥ 1°).

The implications of these findings extend beyond the preclinical ovine model. The validated FE methodology could be adapted in future to clinical cases, offering a framework to predict subject-specific construct loading limits in human patients. By integrating patient-specific CT data and implant configurations, enabling preemptive identification of at-risk constructs immediately post-surgery, tailoring rehabilitation to prevent mechanical failure and potentially reducing revision surgeries. The diversity of the constructs—varying in fracture gap size, implant position, and material— required subject-specific models that incorporated all aspects of a fracture fixation. The good prediction outcomes for these various fixations underlies the robustness of the presented methodology.

Despite these strengths, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the moderate specificity (60%) indicates a tendency to overestimate the occurrence of residual implant bending, which may stem from registration inaccuracies in the co-registration of CT data used to evaluate plate bending, with an estimated error margin of up to 0.5°, or from unassessed damage at the screw–bone interface in the two animals with false positives, which was not analyzed in this study. Additionally, the AO Fracture Monitor's hardware configuration limited recordings to relative signal amplitudes of the daily peaks without load duration or frequency. Moreover, potential torsional loads were not considered. These factors could lead to false positives, which, in clinical settings, might prompt unnecessary interventions such as additional imaging (e.g., X-ray or CT), closer monitoring, or revision surgery, increasing patient burden and healthcare costs. To mitigate this, future studies could refine the FE model's specificity by incorporating screw–bone interface analysis and exploring advance signal processing to account for load duration, pending improvements in sensor technology. The 1° bending angle was set as the threshold for residual bending status, as it was the minimum value reliably measurable through CT image registration and landmarking. Second, the 15 mm displacement applied in the FE models, while effective for inducing plasticity onset, exceeds physiological compression, limiting direct extrapolation to in vivo loading conditions. This non-physiological displacement was a methodological choice to maximize the potential of bending failure in all specimens and provide data for the validation of the FE models but highlights the need for future validation under physiological loads, such as gait cycle simulations. Third, the determination of the plate bending angle is prone to landmarking errors; to minimize this, CT scans from the two timepoints were co-registered and the according transformations applied to the fracture fragment landmarks, reducing intra-specimen error. Fourth, the study relied on a relatively small sample size (n = 11), which, while sufficient for proof-of-concept, may not fully capture the diversity of failure mechanisms across larger populations. The used animal model and the small cohort also excluded pathological conditions such as osteoporosis, limiting the generalizability to a broader population, though ongoing analyses of clinical data aim to address this. Fifth, the focus on early plastic bending within 4 weeks post-operation may not fully address clinically relevant long-term failure modes, such as cyclic fatigue or screw loosening, which are more common in human patients, particularly the elderly. However, as fatigue failure is driven by implant stress, the same FE models could potentially be used to predict the fatigue life of a construct, provided they are validated for cyclic loading scenarios. Sixth, while the preclinical validation used a range of fracture gaps (0.6 – 30.0 mm), the study did not explore complex fracture patterns or diverse fracture sites (e.g., femur, radius), which are critical for clinical translation and are being investigated in ongoing clinical studies. Seventh, the reliance on AO Fracture Monitor data for preclinical validation, sourced from a prior animal study, reflects the study's developmental stage, but the validated FE models are designed to predict failure without the need of sensors in future clinical applications.

Looking forward, this methodology offers a promising outlook for orthopedic research and has the potential to be translated towards clinical practice. Extending validation to larger cohorts, including cyclic loading scenarios beyond 4 weeks at different anatomical locations, would strengthen generalizability and align with clinically more relevant fatigue failure patterns. To facilitate clinical integration, a framework for generating patient-specific FE models using clinically available medial imaging data such as intraoperative or postoperative X-rays and preoperative CT scans, aiming to automate subject-specific FE model creation within routine clinical workflows. Such a framework would enable a translational pathway for immediate post-operative strength assessments clinically, guiding rehabilitation with or without continuous monitoring devices. This workflow, illustrated in a schematic in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Material 14), aims to shift clinical practice from eminence-based to evidence-based rehabilitation management, reducing implant failure rates and optimizing patient outcomes. Additionally, applying machine learning to sensor data could enhance the algorithm's ability to differentiate load levels beyond the plastic limit of the implant, improving predictive precision.

In conclusion, this study establishes a robust FE methodology for predicting in vivo residual implant bending in an ovine model, and validated it, achieving a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 60%. The continuous in vivo sensor data was pivotal for validation but would not be needed for future application of the FE prediction approach. While limitations in specificity, sample size, and measurement precision remain, the potential to extend this framework to predict fatigue failure and guide personalized orthopedic care offers a transformative tool, reducing the burden of implant failure through proactive, patient-specific rehabilitation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dominic Mischler: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Manuela Ernst: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Peter Varga: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the advice of Prof. Philippe Zysset. The authors thank the Preclinical Services of the AO Research Institute Davos team for providing the in vivo ovine data and Alessia Valenti for analyzing the CT data. This study was performed with the assistance of the AO Foundation via the AOTRAUMA Network (Grant No.: AR2021_03).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grok 3 in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2025.08.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Koso R.E., Terhoeve C., Steen R.G., Zura R. Healing, nonunion, and re-operation after internal fixation of diaphyseal and distal femoral fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2018;42(11):2675–2683. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korner J., Lill H., Muller L.P., Hessmann M., Kopf K., Goldhahn J., et al. Distal humerus fractures in elderly patients: results after open reduction and internal fixation. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(Suppl 2):S73–S79. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yetter T.R., Weatherby P.J., Somerson J.S. Complications of articular distal humeral fracture fixation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2021;30(8):1957–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szczesny G., Kopec M., Szolc T., Kowalewski Z.L., Maldyk P. Deformation of the titanium plate stabilizing the lateral ankle fracture due to its overloading in case of the young, Obese patient: case report including the biomechanical analysis. Diagnostics. 2022;12(6) doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12061479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windolf M., Varjas V., Gehweiler D., Schwyn R., Arens D., Constant C., et al. Continuous implant load monitoring to assess bone healing status-evidence from animal testing. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58(7) doi: 10.3390/medicina58070858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris A.P., Anderson A.A., Barnes D.M., Bright S.R., Knudsen C.S., Lewis D.D., et al. Plate failure by bending following tibial fracture stabilisation in 10 cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2016;57(9):472–478. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoniac I.V., Stoia D.I., Ghiban B., Tecu C., Miculescu F., Vigaru C., et al. Failure analysis of a humeral shaft locking compression plate-surface investigation and simulation by finite element method. Materials. 2019;12(7) doi: 10.3390/ma12071128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G., Schmutz B., Wullschleger M., Pearcy M.J., Schuetz M.A. Computational investigations of mechanical failures of internal plate fixation. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2010;224(1):119–126. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jitprapaikulsarn S., Chantarapanich N., Gromprasit A., Mahaisavariya C., Sukha K., Chiawchan S. Dual plating for fixation failure of the distal femur: finite element analysis and a clinical series. Med Eng Phys. 2023;111 doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2022.103926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shim V., Gather A., Hoch A., Schreiber D., Grunert R., Peldschus S., et al. Development of a patient-specific finite element model for predicting implant failure in pelvic ring fracture fixation. Comput Math Methods Med. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/9403821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang N.Z., Liu B.L., Luan Y.C., Zhang M., Cheng C.K. Failure analysis of a locking compression plate with asymmetric holes and polyaxial screws. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;138 doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huo J., Dérand P., Rännar L.-E., Hirsch J.-M., Gamstedt E.K. Failure location prediction by finite element analysis for an additive manufactured mandible implant. Med Eng Phys. 2015;37(9):862–869. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis G.S., Mischler D., Wee H., Reid J.S., Varga P. Finite element analysis of fracture fixation. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021;19(4):403–416. doi: 10.1007/s11914-021-00690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst M., Richards R.G., Windolf M. Smart implants in fracture care - only buzzword or real opportunity? Injury. 2021;52(Suppl 2):S101–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mischler D., Ernst M., Varga P. Predicting overloading plate failure using specimen-specific finite element models combined with implantable sensors. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2025 doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2025.107003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inzana J.A., Varga P., Windolf M. Implicit modeling of screw threads for efficient finite element analysis of complex bone-implant systems. J Biomech. 2016;49(9):1836–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragomir-Daescu D., Op Den Buijs J., McEligot S., Dai Y., Entwistle R.C., Salas C., et al. Robust QCT/FEA models of proximal femur stiffness and fracture load during a sideways fall on the hip. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39(2):742–755. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mischler D., Gueorguiev B., Windolf M., Varga P. On the importance of accurate elasto-plastic material properties in simulating plate osteosynthesis failure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1268787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titanium Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5), Annealed . ASM Aerosapce Specification Metals Inc.; 2024. https://asm.matweb.com/search/SpecificMaterial.asp?bassnum=mtp641 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor W.R., Ehrig R.M., Heller M.O., Schell H., Seebeck P., Duda G.N. Tibio-femoral joint contact forces in sheep. J Biomech. 2006;39(5):791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foo T.-L., Gan A.W., Soh T., Chew W.Y. Mechanical failure of the distal radius volar locking plate. J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(3):332–336. doi: 10.1177/230949901302100314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.