Highlights

-

•

A combination of pseudoviruses and virus-like particles was used as a model for this study.

-

•

Mutations in proline (P) and cysteine (C) severely impede S protein synthesis, cleavage, and viral assembly, consequently impacting virus infectivity.

-

•

The D614 mutation did not hinder the interaction between the S protein and the ACE2 receptor.

-

•

Our research may identify new targets and pathways for the development of antiviral therapy.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Spike protein, D614 mutation, Viral assembly

Abstract

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 has posed a substantial global public - health threat and has led to the emergence of diverse variant strains. A prevalent mutation, D614G, is commonly detected in the spike glycoprotein (S) of successive SARS- CoV-2 variants, which enhances viral infectivity. Here, the objective was to examine the influence of mutations on the synthesis and processing of the S protein, virus assembly, and infectivity. This was achieved by artificially substituting the aspartic acid at position 614 of the S protein with 19 distinct amino acids, including glycine, via codon modification. Pseudoviruses and virus-like particles were employed as models for this investigation. The results demonstrated that the expression characteristics of the modified S proteins diverged from those of the original D614 variant. Moreover, pseudoviruses with various mutations displayed different efficiencies in entering cells expressing ACE2. Significantly, the D614P and D614C mutations disrupted the production and processing of the S protein, exerting a notable impact on virus assembly. However, co-immunoprecipitation analysis indicated that D614 mutations did not hinder the interaction between the S protein and the ACE2 receptor. These findings emphasize the significance of D614 or G614 in S protein expression and virus assembly, providing novel targets and perspectives for the progress of research on spike-based vaccines and antiviral therapeutics.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents a significant threat to both human health and the global economy (Muralidar et al., 2020). According to World Health Organization (WHO) data, as of January 2023, there were over 760 million confirmed cases and 6 million deaths worldwide due to COVID-19, indicating a continuing serious international epidemic situation. The causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is classified as a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus within the Betacoronaviridae genus of the Coronaviridae family (Li et al., 2020; Naqvi et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is notably one of the largest RNA viruses known, with a genome size of approximately 29.8 kb (Zhu et al., 2020). The initial two-thirds of the genetic material consists of nonstructural genes that predominantly code for enzymes involved in viral replication, whereas the remaining one-third encodes four structural proteins, namely, the spike glycoprotein (S), small envelope glycoprotein (E), membrane glycoprotein (M), and nucleocapsid protein (N) (Chen et al., 2020). Within coronaviruses, the N protein is associated with the organization of the virus genome, whereas the M and E proteins primarily play roles in virus assembly (Huang and Wang, 2021). The S protein, on the other hand, is primarily responsible for identifying the host cell receptor, which serves as the entry point for the virus into the cell (Mittal et al., 2020).

The S protein is a trimeric glycoprotein found on the viral envelope, with each monomer weighing approximately 180 kDa (Walls et al., 2020; Wrapp et al., 2020). It is cleaved by a furin-like enzyme to generate two subunits, S1 and S2 (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Mistry et al., 2021). In the early phase of viral infection, the spike glycoprotein of coronaviruses plays a crucial role in receptor binding and membrane fusion (Li, 2016). The heavily glycosylated S trimer interacts with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to facilitate the entry of virions into host cells (Yu et al., 2021; Shang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The S protein has extensive conformational adaptability, enabling it to control the exposure of receptor binding sites and facilitating the significant structural changes necessary for viral and cellular membrane fusion (Dai and Gao, 2021). Moreover, the S protein, which serves as the primary antigen, elicits immune responses crucial for the development of vaccines and drug targets (Cai et al., 2020). Consequently, vigilant surveillance and consideration of the antigenic evolution of circulating viral strains are imperative (Li et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2024).

The D614G mutation, identified in January 2020, involves a substitution at position 614 of the amino acid sequence of the S protein from aspartic acid (D) to glycine (G) (Bhattacharya et al., 2021). Subsequently, variants of SARS-CoV-2 containing this mutation rapidly spread worldwide, supplanting the original virus and emerging as the predominant strain (Daniloski et al., 2021). Research has indicated that this variant exhibits increased transmissibility and a heightened viral load; however, it does not lead to more severe illness or impact the efficacy of current diagnostic tools, therapies, vaccines, or public health interventions. (Zhang et al., 2022). The D614G variant has been prevalent globally for a brief duration, with all variants designated as variants of interest (VOIs) or variants of concern (VOCs) by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States exhibiting the D614G mutation (Fernández, 2020). Compared with other mutations, the D614G mutation has the greatest prevalence, a finding that aligns with the outcomes of our examination and evaluation, as presented in Table 1 (Perez-Gomez, 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Tortorici et al., 2024; Kaku et al., 2024; Gillot et al., 2025). The D614 mutation results in numerous alterations in the properties of the S protein, increasing viral adaptability (Fernández, 2020; Shi and Xie, 2021). The potential replacement of amino acids at the D614 site, other than glycine, and the impact of such substitutions on the virus's biological properties remain uncertain.

Table 1.

Summary of Major Mutants[24–28].

| WHO Name | Lineage (Pango) | First Documented | Status WHO (*CDC) | Mutation: amino acid modification compared with S gene sequence (SARS-CoV-2 /Wuhan-Hu-1, NC_045512.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | B.1.1.7 | UK | VOC | ∆69–70, ∆144–145, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H, T716I, S982A, D1118H |

| Beta | B.1.351 | South Africa | VOC | L18F, D80A, D215G, ∆241–243, R246I, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, A701V |

| Gamma | P.1 | Brazil | VOC | L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G, H655Y, T1027I, V1176F |

| Delta | B.1.617.2 | India | VOC | T19R, G142D, ∆156–157, (∆157–223), R223G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N |

| Omicron | B.1.1.529 | South Africa | VOC | A67V, ∆69–70, T95I, G142D-∆143–145, ∆211-L212I, ins214EPE, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F |

| Epsilon | B.1.427 /B.1.429 |

USA | VOI | S13I, W152C, L452R, D614G |

| Zeta | P.2 | Brazil | VOI | L18F, T20N, P26S, F157L, E484K, D614G, S929I, V1176F |

| Eta | B.1.525 | Nigeria and UK | VOI | Q52R, A67V, ∆69–70, ∆144–145, E484K, D614G, Q677H, F888L |

| Theta | P.3 | Philipines | VOI | 484 K, N501Y, D614G, P681H, E1092K, H1101Y, 1176F |

| Iota | B.1.526 | New York | VOI | L5F, T95I, D253G, E484K, D614G, A701V |

| Kappa | B.1.617.1 | India | VOI | E154K, L452R, E484Q, D614G, P681R, Q1071H |

| Lambda | C.37 | Peru | VOI | S12F, ∆69–70, W152R, R346S, L452R, D614G, Q677H, A899S |

| MU | B.1.621 | Colombia | VOI | T95I, Y144S, Y145N, R346K, E484K, N501Y, D614G, P681H, D950N |

| Omicron | XBB.1.5 | USA | VOI | F486P, S486S, R493Q, Y453F, V83A, G142D, ∆144, T478K, N460K |

| JN.1 | BA.2.86 | Luxembourg | VOI | L455S, F456L, T3255I |

| Omicron | KP.2/KP.3 | India | VOI | Q493E, F456L, R346T |

In this study, D614 of the S protein was first substituted with 19 different amino acids, such as glycine (G), through deliberate alteration of the codon sequence. Notably, beyond the canonical D614 and G614 variants, certain mutations (e.g., A/E/H/Y/V/N614) have sporadically emerged in nature but failed to become stably inherited or epidemiologically sustained (Fig.S1). However, the underlying mechanisms for this selective propagation remain unclear. Therefore, we subsequently investigated the impact of these mutations on the production and maturation of the S protein, viral assembly, and infectivity via the use of pseudoviruses and virus-like particles as experimental models. These investigations provide fundamental insights into the underlying mechanisms governing the expression and maturation of the S protein, and the process of virion assembly.

2. Results

2.1. Impact of the D614 mutation on spike protein expression and proteolytic cleavage

To investigate the influence of the D614 mutation on the expression of the spike protein, the amino acid aspartic acid (D) at position 614 of the S protein was substituted with 19 other amino acids (Fig. 1), including glycine (G), on the basis of the spike sequence of the original Wuhan strain (SARS-CoV-2/Wuhan-Hu-1, NC_045512.2). Spike-expressing pEGFP-N3 vectors containing the 20 mutations at position 614 were generated and used for protein expression localization (Fig. S1A and S2). These spike-expressing vectors were initially introduced into HEK293T cells to confirm the expression and cleavage of the spike protein through Western blot analysis with a GFP antibody and an RBD antibody (Fig. 2A). The expression profiles and quantities of S proteins exhibited variability across different mutations. Notably, the D614P and D614C mutations led to the presence of S proteins in an uncleaved state, which contrasts with the cleaved forms observed in other S protein mutants. These mutants were subsequently inserted into the pCMV-3 × Flag expression vector to be expressed with a C-terminal Flag tag (Fig. S1B). The expression pattern of S-Flag fusion protein is similar to that of S-GFP fusion protein, but the former has a higher expression efficiency (Fig. 2A and B). Meanwhile, we found that different amino acids at position 614 affect the expression and cleavage of S protein (Fig. 2B). Especially when the 614 site is cysteine (C), phenylalanine (F), or proline (P), only the S precursor protein is detected, accompanied by a very small amount of S1 and S2 fragments. These results indicate that a single amino acid change at position 614 significantly affects the expression of S protein, or leads to misfolding of S protein that affects cleavage, or even degradation.

Fig. 1.

Structural modeling of the S protein domain with amino acid variation at site 614. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to substitute aspartic acid (D) at position 614, adjacent to the cleavage site of the wild-type S protein, with each of the other 19 amino acids through codon modification, * denotes naturally occurring mutations.

Fig. 2.

Expression profiling of wild-type and mutant S proteins in 293T cells. (A and B) The expression of the wild-type and mutant S proteins at position 614 were detected by western blot, using some primary antibodies including anti-RBD (probing S1 subunit), anti-EGFP or Flag (probing S2 subunit), in 293T cells transfected with EGFP- or Flag-fusion expression plasmids. β-actin was used as a loading control. Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ and normalized to β-actin loading control (mean ± SEM, n = 3 biological replicates. The original image is supplemental Figure 3 in the supplementary material.

2.2. Role of the D614 mutation in spike protein-mediated viral entry

On the basis of prior validation of the expression data, a series of S-enveloped pseudoviruses were generated via a modified HIV-1-based lentiviral vector, pNL4.3.Luc.R-E-, and the expression plasmids of S protein or its mutants (Fig. 3A). And the infectivity of these pseudoviruses was measured by the quantitative analysis of firefly luciferase activity in 293T-hACE2 cells expressing human-derived ACE2 (Du et al., 2022). The results showed that the single amino acid changes in position 614 of S protein affected its mediated viral infection (Fig. 3B). Evidently, the infectivity of the pseudotype viruses assembled by the individual S mutants with other amino acid at position 614 are enhanced compared to that with the wild-type D614-S protein, such as the natural variant G614 and artificial mutants N614, S614 and R614. On the contrary, more artificial mutations weakened the S-mediated viral infection, especially 614C, 614P and 614T, almost causing S to lose its ability to mediate viral infections in ACE2-expressing cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of amino acid variation at position 614 on S-driven viral entry. (A) Simplified diagram of pseudovirus generation expressing the SARS-CoV-2 S or its mutant proteins. (B) Infective activity of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus particles on 293T-hACE2 cells and the luciferase activity was quantified at 48 hpi. The dashed line indicates the RLU value of wild-type D614, which serves as a benchmark for comparing the infectivity of other mutants. Data shown are means ± SD from 3 replicates. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. (C) Classification and analysis of infectivity changes in pseudotyped viruses packaged with wild-type or mutant spike (S) proteins were performed based on the polarity (polar and nonpolar) of amino acids specifically introduced at position 614, aiming to elucidate potential correlations between amino acid properties and S protein functionality (-, no amino acid).

Subsequently, we comprehensively examined the correlation between the amino acid at position 614 and the S-mediated infectivity, based on the polarity of these amino acids (Fig. 3C). We found that for polar amino acids, substitutions at position 614 with N (Asp), Q (Glu), and R (Arg) resulted in enhanced infectivity of the pseudotyped virus, whereas substitutions with P (Pro) or C (Cys) led to nearly undetectable infectivity. Among nonpolar amino acids, only when position 614 was substituted with G (Gly) did the S-assembled pseudotyped virus exhibit significantly higher infectious activity.

2.3. Amino acid mutations at position 614 alter spike protein localization

Previous studies have demonstrated that specific genetic variations can influence the biosynthesis and post-translational processing of the S protein, potentially altering its subcellular localization. To investigate the intracellular distribution of the D614 mutant, HeLa cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding the S protein or its mutant variants, each tagged with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) at the C-terminus, and Lck-expressing plasmid. The plasmid carrying the tyrosine kinase Lck gene, fused with mCherry at its C-terminal, was employed as a plasma membrane marker. A high degree of colocalization, indicated by overlapping green and red fluorescence signals, suggests direct interaction between the proteins. As shown in Fig. 4, all mutant S proteins, except for D614P and D614C, were successfully translocated to the cell membrane. The localization of the S protein is critical for the pseudotyped virus packaging process. When the S protein is expressed on the cell surface, it promotes the efficient production of pseudotyped viruses. In contrast, mutations introducing proline (P) or cysteine (C) disrupt vesicle membrane localization, likely impairing virus packaging and resulting in reduced infectivity.

Fig. 4.

Effect of amino acid mutation at site 614 of S protein on its localization. Analysis of the subcellular localization of C-terminally EGFP-tagged S or its mutants in HeLa cells via laser scanning confocal microscopy (63 ×, oil). The tyrosine-protein kinase Lck was used as a subcellular localization marker.

2.4. Role of position 614 mutations in the S protein on viral-like particle packaging

Based on the experimental outcomes of amino acid mutations at site 614 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein and their effects on synthesis and processing, we evaluated the impact of these mutations on the production of pseudotyped viruses and virus-like particles (VLPs). To generate pseudotyped viruses, 293T cells were cotransfected with a backbone plasmid and ten selected plasmids expressing the SARS-CoV-2 S protein respectively. The presence of the S protein in both pseudotyped virus-producing cells and viral supernatants was confirmed by Western blot analysis, using p24 and GAPDH as internal controls (Fig. 5A and B). The results demonstrated that mutations introducing P (proline) and C (cysteine) disrupted S protein synthesis and processing, significantly impairing virus assembly, which aligned with prior infection assays (Fig. 3B). In contrast, mutations to S (Ser), V (Val), Y (Tyr), and W (Try) did not markedly alter S protein expression or affect virus assembly and production. Mutations to G (Gly) and N (Asp) slightly enhanced S protein expression or cleavage, particularly increasing the infectious activity of the resulting pseudotyped virus particles.

Fig. 5.

Effect of amino acid mutation at position 614 of S protein on viral packaging. (A and B) Western blot analysis of the protein expression of pseudovirus S protein and p24 in packaging cells and virus supernatant. (C) Schematic outline of the SARS-CoV-2 VLP production process. Plasmids encoding the SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins E, M, and N were cotransfected into HEK293T cells with plasmids encoding WT S or its mutants to obtain VLPs. (D and E) Western blot analysis of the expression of the major structural proteins S and NP on the VLPs. The original image is Supplemental Figure 4 in the supplementary material.

To generate virus-like particles (VLPs), plasmids expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein or its mutant variants were cotransfected with plasmids encoding the structural proteins M, E, and N into 293T cells, as illustrated in Fig. 5C. The expression of the major structural proteins in both VLP-producing cells and culture supernatants was assessed by Western blot analysis, using β-actin as the loading control. The results demonstrated that P (Pro) and C (Cys) mutations at 614 sites significantly reduced S protein expression, indicating a substantial disruption in S protein synthesis, which consequently impaired the VLP assembly process (Fig. 5D and 5E).

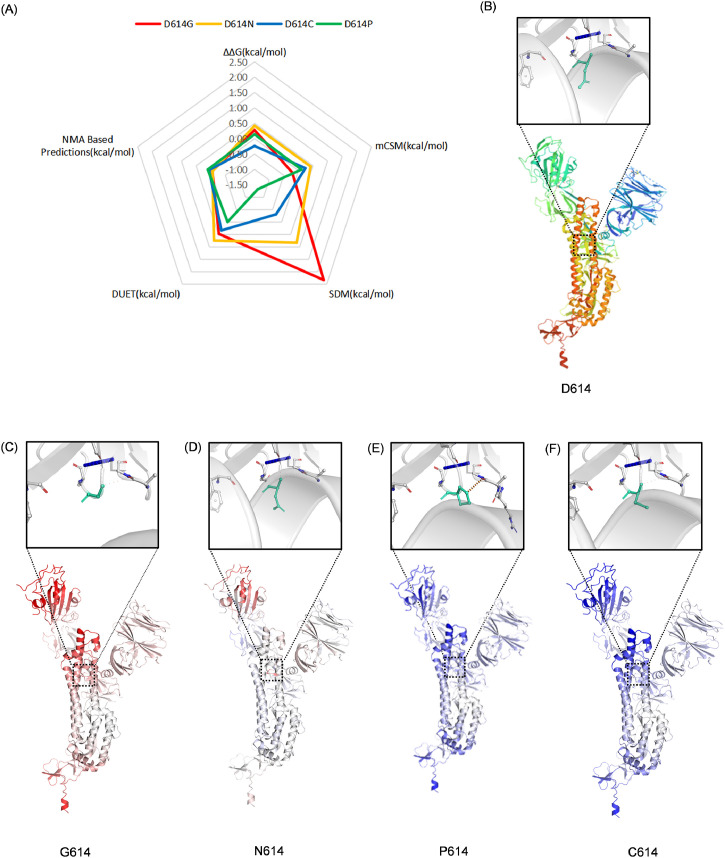

2.5. Subtle effects of amino acid substitutions at spike protein site 614 on structural stability

The critical role of the S protein in mediating viral infectivity and transmission has established it as the primary structural and bioinformatic focal point for investigating the study of the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 (Guzzi et al., 2023). To evaluate the effects of amino acid mutations at position 614 of the spike (S) protein on protein stability, receptor-binding capacity, and viral infectivity, we assessed the structural stability of the G614, N614, P614, and C614 variants using five computational approaches: MCSM, DUET, SDM, free energy prediction, and normal mode analysis (NMA). The results demonstrated significant differences in stability among the variants. Specifically, the SDM method, supported by DUET and free energy predictions, indicated that the D614G and D614N variants exhibited higher stability compared to D614P and D614C. In contrast, the NMA and MCSM methods did not provide consistent or reliable predictions (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Impact of amino acid substitution at position 614 in the S protein on its structural conformation. (A) Structural stability predictions of the four mutants were performed using an integrated computational approach incorporating mCSM, DUET, SDM, free energy calculations, and normal mode analysis (NMA). (B-F) Comprehensive structural analysis including molecular flexibility assessment through DynaMut and ΔVibrational Entropy Energy calculations, complemented by molecular docking and simulation studies of the mutant variants.

Molecular docking and simulation techniques were employed to analyze the mutant sites, with the molecular flexibility of the protein structure predicted using the ΔVibrational Entropy Energy method. A color-coded scheme was applied, where blue regions indicated structural rigidity, and red regions denoted increased flexibility. The wild-type simulation structure is illustrated in Fig. 6B Analysis revealed that the D614G and D614N mutations enhanced the flexibility of S protein, promoting unhindered binding of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) to its receptor and facilitating viral entry (Fig. 6C and D). In contrast, the D614P and D614C mutations significantly restricted S protein flexibility, thereby limiting the angular range of RBD-receptor binding (Fig. 6E and F). These findings are consistent with our previous experimental results. Specifically, D614G and D614N mutations create adaptable binding regions, while the pentagonal ring structure of D614P forms stable hydrogen bonds that constrain protein flexibility, potentially impairing subsequent protein functions. Additionally, D614C is prone to disulfide bond formation, making it unsuitable for molecular docking and the generation of a comprehensive structural model.

In conclusion, the bioinformatics-based predictions of mutant protein stability are consistent with empirical data from previous experiments, enabling the identification and evaluation of mutants with favorable functional properties. This computational approach provides critical insights and robust supporting evidence for guiding subsequent experimental studies and can be extended to the analysis of other mutant variants.

2.6. Position 614 mutations in the spike protein do not influence ACE2 interactions

Finally, we investigated the potential impact of amino acid alterations at position 614 of S protein on its interaction with ACE2 using coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays, with ACE2 (C-Myc-tagged) as the capture protein. Cell lysates and immunoprecipitates from 293T cells cotransfected with plasmids encoding the S protein or its mutants, along with either the ACE2-expressing plasmid or an empty vector, were analyzed by Western blot using anti-RBD and anti-c-Myc antibodies. Protein expression analysis confirmed the intracellular expression of both the S protein (or its mutants) and ACE2 (Fig. 7). Interestingly, in the cotransfection systems of ACE2 with the S protein or its mutants, the S protein and its S1 subunit appeared to undergo partial degradation. Whether this phenotype is associated with the proteolytic activity of ACE2 remains to be further explored. As expected, ACE2-Myc immunoprecipitates analysis revealed positive signals for the S and S1 subunits in samples cotransfected with ACE2 and the S protein or its mutants, indicating that ACE2 binds to both wild-type and mutant S proteins. These findings demonstrate that amino acid changes at position 614 do not affect the interaction between the S protein and ACE2.

Fig. 7.

Interaction between the S protein of the D614 mutant and the ACE2 protein via western blot analysis. Input section: The expression of wild-type S or its mutants and ACE2 Protein. The lysates were extracted from cells co-transfected with pCMV-S/614x-3 × Flag and pCMV-Myc-ACE2 or the control vector, followed by detection using antibodies anti-Myc and anti-RBD. Co-IP section: Detection of wild-type S or its mutants and ACE2 protein in the precipitates captured by ACE2-myc using Myc-tagged magnetic beads. The original image is Supplemental Figure 5 in the supplementary material.

3. Discussion

The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection has resulted in a swift escalation in the incidence of new cases of COVID-19, presenting a significant global health hazard. Understanding the mutational variations and swift evolution of viruses, along with the implications for novel vaccine creation, diagnostic testing, antiviral drug mechanisms, drug resistance, and immune responses, is imperative (Chellapandi and Saranya, 2020; Sanjuán and Domingo-Calap, 2016).The genetic progression of the S protein in emerging coronaviruses is a significant area of focus owing to its crucial role in determining host and tissue specificity, as well as its importance as a primary target for vaccines, neutralizing antibodies, and antiviral agents that inhibit viral entry. Given its essential function, the S protein represents a key target for the development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and ongoing therapeutic investigations (Matsuyama et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2020; Ke et al., 2020). Changes in the S protein are expected to modify the composition, characteristics, and stability of the spike protein, consequently impacting the transmissibility and virulence of the virus (Wang et al., 2021). By analyzing 9002 S gene sequences in the EpiCoV database from GISAID, scientists have pinpointed the D614G mutation as a significant variant, constituting approximately 90 % of the total mutations identified (5583/6253), with a mutation frequency specific to the site exceeding 62 % (5583/9002) (Jiang et al., 2020). According to epidemiological data, the WHO categorizes mutations into two groups: variants of interest (VOIs) and variants of concern (VOCs), with VOIs and VOCs being categorized on the basis of factors such as viral transmissibility, severity of disease, and effectiveness of vaccines (Fernandes et al., 2022; Flores-Vega et al., 2022; Chakraborty et al., 2022 Mar). SARS-CoV-2 variants originating from various nations exhibit sequence homology in the S protein, with the prevalent presence of the D614G mutation across emerging VOCs and VOIs. Notably, the D614G mutation is observed at a higher frequency than other mutations in these variants. This mutation is believed to enhance the viral adaptability and fitness of the variants mentioned above in which it is present (Bhattacharya et al., 2021). Owing to the D614G mutation, the SARS-CoV-2 mutant strain has acquired viral adaptations to increase viral replication and increase transmission. Therefore, in this study, we replaced aspartic acid at position 614 of the S protein with 19 other amino acids (including glycine) by artificially changing the codon and then used pseudoviruses and virus-like particles as models to explore the effects of mutations on S protein synthesis and processing, viral assembly and infectivity.

In fact, besides the D614G variant, other naturally occurring mutations (e.g., D614Y/V/N) do exist, albeit at extremely low frequencies (<0.1 %, Fig.S1). This observation raises a critical scientific question: Why have these alternative mutants failed to achieve stable transmission? To address this, our study employed a comprehensive full-amino-acid scanning mutagenesis approach to systematically investigate how residues at position 614 influence the biological properties and functions of S protein. By utilizing infectious cDNA clones of the predominant SARS-CoV-2 strain, investigators have conducted a comparative analysis of the 614 variants of the S protein in both animal models and human cell cultures. These findings indicate an increased replication rate of the D614G variant in the upper respiratory tract and an increased transmission potential of the D614G variant in an animal model of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Hou et al., 2020; Plante et al., 2020). Examination of the spread and prevalence of the D614G variant of SARS-CoV-2 in the United Kingdom indicates that this variant has a competitive edge and is linked to increased viral concentrations in younger individuals. However, there is no correlation between this variant and increased clinical severity or fatality rates in patients with COVID-19 (Volz et al., 2021). One primary area of interest in contemporary genetic research on SARS-CoV-2 pertains to investigating whether mutations have a substantial impact on key attributes of the virus, including its transmission method, transmission rate, and pathogenicity.

The stability of the D614G variant in SARS-CoV-2 has been established, but the impact of mutation of this site to different amino acids on the biological properties of the virus remains uncertain. Our findings indicate that mutations such as D614P and D614C influence the cleavage and expression of S proteins. Subsequent investigations revealed that the Pro (P) and Cys (C) mutations did not localize within the capsid and that these amino acid alterations influenced the positioning of the S protein, consequently impacting the viral packaging process and, by extension, the infectivity of the virus. Notably, the D614P and D614C mutations disrupted the formation of pseudoviruses and virus-like particles. The extensive presence of the glycosylated S protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 facilitates its interaction with the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), thereby facilitating viral entry into the host cell (Letko et al., 2020). Further experiments demonstrated that the mutation occurring at position 614 did not impede the binding of the S protein to the ACE2 receptor. Instead, it disrupts the virus assembly process by interfering with the synthesis and processing of the S protein, resulting in variations in infectivity. Specifically, mutations in proline (P) and cysteine (C) severely impede S protein synthesis, cleavage, and viral assembly, consequently impacting virus infectivity. These findings support that certain mutations may be lethal due to their disruptive effects on S protein structure or function.

While this study elucidates the functional significance of amino acid residues at position 614 in the S protein, it represents merely a paradigmatic case in SARS-CoV-2 viral evolution. The precise molecular mechanisms underlying numerous neutral mutations and their evolutionary conservation remain largely unresolved. We will therefore extend our investigations to the evolutionary pressure analysis through dN/dS ratio calculations, the structural impact prediction via ∆∆G free energy computations, and comprehensive mutational profiling of key structural proteins (including S and E proteins). Overall, our study offers foundational insights into the mechanisms underlying SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis, potentially identifying novel targets and avenues for the development of antiviral therapeutics.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Plasmid construction

The amino acid sequence of the surface spike glycoprotein (S protein) of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was obtained from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/QHD43416.1), with accession NC_045512.2, 1273 aa, which was synthesized and then inserted into the eukaryotic expression vector pEGFP-N3. The S mutants were created through genetic engineering techniques via the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs [NEB], USA), with the original sequence derived from the S gene of the Wuhan-Hu-1 strain. To increase packaging efficiency, 20 mutant constructs were individually inserted into the Kpn Ⅰ/Bam HI site of the pCMV-3 × Flag expression vector. The lentiviral backbone vector pNL4.3.Luc.R-E- is maintained within the laboratory setting.

4.2. Reagents and antibodies

GoldBand Plus 3-color Regular Range Protein Marker(8–180 kDa) (YEASEN, #20350ES72); SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) Spike RBD Antibody, Rabbit PAb, Antigen Affinity Purified (Sinobiological, # 40,592-T62); SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) Spike S2 Antibody, Rabbit PAb, Antigen Affinity Purified (Sinobiological, #40,590-T62); GFP (4B10) Mouse mAb (CST, #2955); Flag (DYKDDDDK) tag Polyclonal Antibody (Proteintech, #20,543–1-AP); Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag-p24 Antibody, Rabbit PAb, Antigen Affinity Purified (Sinobiological, #11,695-RP02); Myc-Tag (9B11) Mouse mAb (CST, #2276); GAPDH Mouse Monoclonal Antibody (Origene, #OTI2D9); β-actin Polyclonal Antibody (Proteintech, #20,536–1-AP).

4.3. Cells and sTable 293T-hACE2 cell lines

The HEK293T and HeLa cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; HyClone, USA) supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin and kindly provided by Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The HEK293T cell lines, denoted as 293T-hACE2, with stable expression of human ACE2 was generated in our laboratory via the homologous recombination mediated by lentivirus and multiple rounds of puromycin pressure screening.

4.4. Pseudotyped virus packaging and virus entry experiments

A total of 1 × 106 HEK293T cells in a 6-well plate were cotransfected with 3 μg of pCMV-S/614X −3 × Flag and 3 μg of pNL4–3.Luc. R-E- using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo, USA) to prepare 20 SARS-CoV-2 S-pseudotyped lentiviral luciferase reporter viruses. After 6 h, the transfection mixture was discarded, and the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2 % FBS. At 48 h, the supernatants were collected and purified by filtration with a 0.45 μm filter. 293T-hACE2 cells were infected with pseudoviruses for 48 h. Then, the fluorescence value was detected via the One-Lumi™ firefly luciferase reporter gene reagent to analyze the infectivity after mutation.

4.5. Subcellular localization analysis

The subcellular distribution of the C-terminally EGFP-tagged S protein and its variants in HeLa cells was examined through laser scanning confocal microscopy (63 ×, oil). The tyrosine-protein kinase Lck served as a reference marker for subcellular localization. HeLa cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing the S protein and its mutants, along with the Lck marker, for 48 h. The cells were subsequently fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, and stained with DAPI for 10 min in a light-protected environment. Following staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS. Imaging was performed via a fluorescence microscope or a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope.

4.6. Analysis of the incorporation of spikes into pseudotyped virus particles

The viral supernatant was obtained and combined with Lenti-X™ Concentrator lentivirus concentration reagent at a 3:1 vol ratio for the purpose of concentrating the virus. The mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C, after which the supernatant was carefully removed, and the resulting pellet was utilized for sample preparation. The packaging cells were harvested for protein extraction and quantification via the BCA method. Protein expression in both the packaging cells and the viral supernatant was assessed through Western blot analysis employing antibodies specific to the RBD, S2, or HIV p24.

4.7. Assembly and component characterization of SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles

A total of 1 × 106 HEK293T cells were cotransfected in a 6-well plate with 2 μg each of pCMV-S/614x-3 × Flag, pCAGGS-ME, and pcDNA3.1-NP. After 48 h, the culture supernatant was harvested for the preparation of concentrated samples, while the transfected cells were collected for protein extraction and subsequent quantification. The expression of the four structural proteins in both the cell culture supernatants and the cotransfected cells was assessed through Western blot analysis via antibodies specific for the RBD, S2, N, and Flag tags.

4.8. Mutant structure prediction

A wild-type structural model of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein was developed utilizing the PDB ID 6vxx, while a library of SARS-CoV-2 D614 mutations was created through a combined approach involving the DynaMut website and PyMOL software. Five distinct data parameters, namely, mCSM, DUET, SDM, binding free energy prediction, and NMA, were compiled to establish a stability prediction dataset via Microsoft Excel. Subsequent molecular docking and simulations were conducted on the mutant sites, with the ΔVibrational Entropy Energy method employed to forecast the molecular flexibility of the protein structure and assess the impact of mutations on protein stability.

4.9. Co-Immunoprecipitation analysis

The pCMV-S/614x-3 × Flag plasmid and pCMV-Myc-ACE2 plasmid were cotransfected into 293T cells via pEIpro transfection reagent, with a vector control included for comparison. Following a 48-hour incubation period, the cells were harvested and subjected to lysis via the addition of 500 μl of IP lysis buffer on ice for 30 min. The resulting lysate was then centrifuged, and the supernatant was transferred to a new EP tube. A portion of the lysate (100 μL) was reserved for the input group. Subsequently, 30 µL of equilibrated PierceTM anti-C-Myc agarose agar pellets were added to the remaining lysate and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the agarose pellets were resuspended in 500 μL of precooled TBS-T for subsequent SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

4.10. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD from 3 or 6 replicates. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses of the data were performed by using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.1. Statistical comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test. ns, no significant differences; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (GZNL2023A01004); Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220530152402006); Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences Young Scientific Talent Recruitment Program (R2024YJ-QG001); Young Scientific Talent Development Program, Institute of Animal Health, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (PY2024004).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental materials.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaoshuang Shi: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Jiamin Wang: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Chang Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Shouwen Du: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2025.199624.

Contributor Information

Chang Li, Email: lichang78@163.com.

Shouwen Du, Email: du-guhong@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Bhattacharya M., Chatterjee S., Sharma A.R., Agoramoorthy G., Chakraborty C. D614G mutation and SARS-CoV-2: impact on S-protein structure, function, infectivity, and immunity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021;105:9035–9045. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11676-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Zhang J., Xiao T., Peng H., Sterling S.M., Walsh R.M., Jr., et al. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sci. 2020;369:1586–1592. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty C., Bhattacharya M., Sharma A.R. Present variants of concern and variants of interest of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: their significant mutations in S-glycoprotein, infectivity, re-infectivity, immune escape and vaccines activity. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022 Mar;32(2):e2270. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2270. Epub 2021 Jun 27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chellapandi P., Saranya S. Genomics insights of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) into target-based drug discovery. Med. Chem. Res.: Int. J. Rapid Commun. Des. Mech. Action Biol. Act. Agents. 2020;29:1777–1791. doi: 10.1007/s00044-020-02610-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y.S., Lam C.Y., Tan P.H., Tsang H.F., Wong S.C. Comprehensive review of COVID-19: epidemiology, pathogenesis, advancement in diagnostic and Detection techniques, and post-pandemic treatment strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024:25. doi: 10.3390/ijms25158155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L., Gao G.F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:73–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniloski Z., Jordan T.X., Ilmain J.K., Guo X., Bhabha G., tenOever B.R., et al. The Spike D614G mutation increases SARS-CoV-2 infection of multiple human cell types. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S., Xu W., Wang Y., Li L., Hao P., Tian M., et al. The "LLQY" motif on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein affects S incorporation into virus particles. J. Virol. 2022;96 doi: 10.1128/jvi.01897-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A. Structural impact of mutation D614G in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: enhanced infectivity and therapeutic opportunity. ACS. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:1667–1670. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Q., Inchakalody V.P., Merhi M., Mestiri S., Taib N., Moustafa Abo, El-Ella D., et al. Emerging COVID-19 variants and their impact on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, therapeutics and vaccines. Ann. Med. 2022;54:524–540. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2031274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Vega V.R., Monroy-Molina J.V., Jiménez-Hernández L.E., Torres A.G., Santos-Preciado J.I., Rosales-Reyes R. SARS-CoV-2: evolution and emergence of new viral variants. Viruses. 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/v14040653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillot C., David C., Dogné J.M., Cabo J., Douxfils J., Favresse J. Neutralizing antibodies against KP.2 and KP.3: why the current vaccine needs an update. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025;63:e82–ee5. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2024-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzi P.H., di Paola L., Puccio B., Lomoio U., Giuliani A., Veltri P. Computational analysis of the sequence-structure relation in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein using protein contact networks. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:2837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30052-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Multibasic Pöhlmann S.A. Cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of Human lung cells. Mol. Cell. 2020;78:779. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022. -84.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y.J., Chiba S., Halfmann P., Ehre C., Kuroda M., Dinnon K.H., 3rd, et al. SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits enhanced replication ex vivo and earlier transmission in vivo. BioRxiv: Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abe8499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.W., Wang S.F. SARS-CoV-2 entry related viral and host genetic variations: implications on COVID-19 severity. Immune Escape Infect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021:22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Zhang Z., Wang C., Ren H., Gao L., Peng H., et al. Bimodular effects of D614G mutation on the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 enhance protein processing, membrane fusion, and viral infectivity. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:268. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00392-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku Y., Okumura K., Padilla-Blanco M., Kosugi Y., Uriu K., Hinay A.A., Jr., et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 variant. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024;24:e82. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Z., Oton J., Qu K., Cortese M., Zila V., McKeane L., et al. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature. 2020;588:498–502. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Yang Y., Ren L. Genetic evolution analysis of 2019 novel coronavirus and coronavirus from other species. Infect. Genet. Evol.: J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2020;82 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Wu J., Nie J., Zhang L., Hao H., Liu S., et al. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. 2020;182:1284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.012. -94.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu Rev. Virol. 2016;3:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S., Nao N., Shirato K., Kawase M., Saito S., Takayama I., et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117:7001–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002589117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry P., Barmania F., Mellet J., Peta K., Strydom A., Viljoen I.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, vaccines, and host immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.809244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal A., Manjunath K., Ranjan R.K., Kaushik S., Kumar S., Verma V. COVID-19 pandemic: insights into structure, function, and hACE2 receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. PLoS. Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidar S., Ambi S.V., Sekaran S., Krishnan U.M. The emergence of COVID-19 as a global pandemic: understanding the epidemiology, immune response and potential therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie. 2020;179:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi A.A.T., Fatima K., Mohammad T., Fatima U., Singh I.K., Singh A., et al. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: structural genomics approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis. Dis. 2020;1866 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gomez R. The development of SARS-CoV-2 variants: the gene makes the disease. J. Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/jdb9040058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante J.A., Liu Y., Liu J., Xia H., Johnson B.A., Lokugamage K.G., et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness and neutralization susceptibility. Biorxiv: Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuán R., Domingo-Calap P. Mechanisms of viral mutation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.: CMLS. 2016;73:4433–4448. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A.C., Xie X. Making sense of spike D614G in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021;64:1062–1067. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1893-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici M.A., Addetia A., Seo A.J., Brown J., Sprouse K., Logue J., et al. Persistent immune imprinting occurs after vaccination with the COVID-19 XBB.1.5 mRNA booster in humans. Immunity. 2024;57:904. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.02.016. -11.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Price A., Jorgensen D., Á O'Toole, et al. Evaluating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutation D614G on transmissibility and pathogenicity. Cell. 2021;184:64–75.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. -92.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using Human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zheng Y., Niu Z., Jiang X., Sun Q. The virological impacts of SARS-CoV-2 D614G mutation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;13:712–720. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjab045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Sci. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S., Liu M., Wang C., Xu W., Lan Q., Feng S., et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020;30:343–355. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Li Z., He X., Gebre M.S., Bondzie E.A., Wan H., et al. Deletion of the SARS-CoV-2 spike cytoplasmic tail increases infectivity in pseudovirus neutralization assays. J. Virol. 2021;95 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00044-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang H., Zhang W. SARS-CoV-2 variants, immune escape, and countermeasures. Front. Med. 2022;16:196–207. doi: 10.1007/s11684-021-0906-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li Q., Liang Z., Li T., Liu S., Cui Q., et al. The significant immune escape of pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 variant Omicron. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2022;11:1–5. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.2017757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental materials.