Abstract

Background

For patients diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), residual disease (RD) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is associated with increased rates of recurrence and poor prognosis. Adjuvant therapy with capecitabine is considered standard management for TNBC-RD based on the CREATE-X study, although real-world data are limited. Real-world utilization of adjuvant capecitabine for patients with TNBC-RD and the association of capecitabine with survival outcomes remains largely unknown.

Patients and methods

We evaluated survival outcomes in patients with stage I-III TNBC (including estrogen and progesterone receptor <10%) who received NAC and underwent breast surgery between January 2016 and June 2019 at three comprehensive cancer centers. Treatment in the adjuvant setting was categorized as capecitabine, other systemic therapy, or no adjuvant therapy. Propensity score methods were used to control potential confounding effects from baseline covariates. Survival outcomes were estimated using Kaplan–Meier and propensity weighted Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

In the total population, 661/977 (67.7%) had RD after NAC; the NAC regimens were primarily anthracycline–taxane (n = 611; 62.5%), anthracycline–taxane–platinum (n = 180; 18.4%), or taxane–platinum (n = 39; 4.0%). Among patients with TNBC-RD, 45.1% (298/661) did not receive any adjuvant therapy. Among those who received adjuvant therapy, 202/363 (55.6%) received capecitabine, 115/363 (31.7%) other chemotherapy, and 46/363 (12.7%) endocrine or targeted therapy. At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, receipt of capecitabine was associated with significantly improved recurrence-free survival [RFS; propensity-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54-0.91, P = 0.008], distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS; HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54-0.93, P = 0.01), and overall survival (OS; HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49-0.90, P = 0.009).

Conclusion

In this large cohort of patients with TNBC-RD after NAC, omission of adjuvant therapy was common, with less than one-third of patients receiving adjuvant capecitabine. Receipt of adjuvant capecitabine was associated with significantly improved RFS, DRFS, and OS.

Key words: early stage, TNBC, pCR, residual disease, capecitabine, survival, breast cancer

Highlights

-

•

Real-world utilization of adjuvant capecitabine and outcomes data for patients with TNBC and RD are limited.

-

•

Among patients with TNBC with RD, 45.1% (298/661) did not receive any adjuvant therapy.

-

•

Among patients who received adjuvant therapy, 55.6% (202/363) received capecitabine.

-

•

Receipt of adjuvant capecitabine was associated with significantly improved survival.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) status is defined by the absence of estrogen expression, progesterone expression, and HER2 receptor overexpression/amplification. Most patients diagnosed with early TNBC are considered candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC).1,2 The utilization of NAC can contribute to downstaging of the primary tumor and inform prognosis, with pathologic complete response (pCR) associated with a significantly lower rate of recurrence versus residual disease (RD). In the era before widespread adoption of the KEYNOTE-522 regimen with NAC plus immune checkpoint inhibition,3, 4, 5 rates of recurrence in patients with RD post-NAC approached 50%, resulting in efforts to potentially escalate therapy in the adjuvant setting for patients with high-risk disease, defined by RD after NAC.6

There is great interest and growing data regarding adjuvant therapies that could reduce risk of recurrence after TNBC-RD.7,8 The CREATE-X trial evaluated adjuvant capecitabine versus observation among patients with HER2-negative breast cancer who had RD after receiving NAC containing an anthracycline, a taxane, or both. Overall, the results demonstrated improved disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with TNBC treated with capecitabine (versus not), establishing capecitabine as an adjuvant systemic therapy option for patients with TNBC-RD after NAC [National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Category 2A recommendation].7,9 Although it has been widely adopted, this large study has not yet been validated and, further, adjuvant capecitabine after prior anthracycline and/or taxane chemotherapy in patients with TNBC unselected by type of chemotherapy (neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant) and pathologic response (GEICAM 2003-11/CIBOMA 2004-01) did not show benefit. Adjuvant olaparib is also a consideration for patients with TNBC-RD who harbor a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 (gBRCA) mutation (NCCN Category 1 recommendation), based on the OlympiA trial.8,9

Real-world utilization of adjuvant capecitabine for patients with TNBC-RD and the association of capecitabine with survival outcomes remains largely unknown. To address this gap, this study investigated the utilization of capecitabine and other adjuvant therapies, and the association with survival outcomes in a large cohort of patients with TNBC receiving NAC before routine use of immunotherapy. Within the multi-institutional cohort of patients, the primary objective of this study was to compare the survival outcomes among patients with TNBC-RD who received adjuvant capecitabine with those who did not receive adjuvant therapy.

Methods

Population

Patients diagnosed with stage I-III TNBC who received NAC and underwent breast and/or axillary surgery from 1 January 2016 to 30 June 2019 were identified in three prospectively maintained institutional databases at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), and The Ohio State University (OSU). Specifically, the databases were searched to identify patients who were at least 18 years old at diagnosis with nonmetastatic TNBC (including hormone receptor-negative or hormone receptor-low/HER2-negative breast cancer) as defined by American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines10,11 {estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor <10% according to immunohistochemistry (IHC) and HER2-negative [i.e. IHC 0, IHC 1+, or IHC 2+ with in situ hybridization (ISH) results negative for HER2 amplification]}. Detailed demographic, clinical, and pathological data on the patients were collected (Table 1), including patient age, race, gBRCA status, initial tumor stage, clinical nodal status, and (neo) adjuvant treatments. Cancer-related outcomes including response to NAC (pCR versus the presence of RD), and the disease and vital status at last follow-up were assessed. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of each institution.

Table 1.

Clinical, pathologic, and treatment characteristics of patients with triple-negative breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant hemotherapy

| Residual disease (n = 661) | Pathologic complete response (n = 316) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.968 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 50.5 (12.4) | 50.4 (13.1) | |

| Median (min, max) | 50.3 (21.0, 83.3) | 50.3 (24.5, 83.4) | |

| Sex assigned at birth, % | 1 | ||

| Female | 659 (99.7) | 316 (100) | |

| Male | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Race, % | 0.758 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 30 (4.5) | 18 (5.7) | |

| Black or African American | 88 (13.3) | 44 (13.9) | |

| Caucasian | 506 (76.6) | 240 (75.9) | |

| Other | 27 (4.1) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 10 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Germline status, % | 0.001 | ||

| Known BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation | 79 (12.0) | 63 (19.9) | |

| No mutation | 422 (63.8) | 175 (55.4) | |

| Not tested | 92 (13.9) | 32 (10.1) | |

| Other mutation | 24 (3.6) | 17 (5.4) | |

| Missing | 44 (6.7) | 29 (9.2) | |

| Clinical T-stage at diagnosis, % | <0.001 | ||

| T0 | 6 (0.9) | 9 (2.8) | |

| T1 | 93 (14.1) | 95 (30.1) | |

| T2 | 367 (55.5) | 155 (49.1) | |

| T3 | 113 (17.1) | 24 (7.6) | |

| T4 | 80 (12.1) | 32 (10.1) | |

| TX | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Clinical N-stage at diagnosis, % | 0.031 | ||

| N0 | 309 (46.7) | 180 (57.0) | |

| N1 | 243 (36.8) | 89 (28.2) | |

| N2 | 46 (7.0) | 19 (6.0) | |

| N3 | 62 (9.4) | 28 (8.9) | |

| NX | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| AJCC clinical stage at diagnosis, % | <0.001 | ||

| Stage IA | 50 (7.6) | 56 (17.7) | |

| Stage IB | 4 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Stage IIA | 242 (36.6) | 115 (36.4) | |

| Stage IIB | 154 (23.3) | 64 (20.3) | |

| Stage IIIA | 81 (12.3) | 19 (6.0) | |

| Stage IIIB | 64 (9.7) | 29 (9.2) | |

| Stage IIIC | 66 (10.0) | 28 (8.9) | |

| Histologic type, % | 0.095 | ||

| Invasive ductal | 610 (92.3) | 299 (94.6) | |

| Invasive lobular | 3 (0.5) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Mixed ductal and lobular | 12 (1.8) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Other | 35 (5.3) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Hormone receptor status at diagnosis, % | 0.968 | ||

| Negative | 544 (82.3) | 259 (82.0) | |

| Low | 117 (17.7) | 57 (18.0) | |

| HER2 status at diagnosis, % | 0.890 | ||

| IHC score 0 | 397 (60.1) | 192 (60.8) | |

| Low | 264 (39.9) | 124 (39.2) | |

| RCB class, % | - | ||

| RCB 0 | 0 (0) | 316 (100) | |

| RCB-I | 94 (14.2) | - | |

| RCB-II | 304 (46.0) | - | |

| RCB-III | 146 (22.1) | - | |

| Cannot be calculated/unknown/not documented | 117 (17.7) | - | |

| Neoadjuvant anthracycline + taxane ± platinum, % | 0.182 | ||

| Yes | 527 (79.7) | 264 (83.5) | |

| No | 134 (20.3) | 52 (16.5) | |

| Breast surgery, % | 0.055 | ||

| Breast conserving therapy | 241 (36.5) | 130 (41.1) | |

| Mastectomy | 417 (63.1) | 181 (57.3) | |

| Axillary surgery only | 3 (0.5) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Axillary surgery, % | <0.001 | ||

| Only SLNB | 269 (40.7) | 168 (53.2) | |

| Only ALND | 244 (36.9) | 73 (23.1) | |

| Both (SLNB followed by ALND) | 60 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| No axillary surgery | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Unknown | 84 (12.7) | 73 (23.1) | |

| Radiation therapy receipt, % | 0.034 | ||

| No | 154 (23.3) | 94 (29.7) | |

| Yes | 505 (76.4) | 222 (70.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

Bold P value indicates nominal P < 0.05.

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RCB, residual cancer burden; SD, standard deviation; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Clinicopathological parameters

Standardized endpoint definitions were followed.12 pCR was defined as the absence of invasive RD within both the breast and axilla. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the duration from primary surgery to development of breast cancer recurrence at a local or distant site or death owing to any cause, whichever occurred first. Distant RFS (DRFS) was defined as the duration from primary surgery to development of breast cancer metastasis at a distant site or death owing to any cause, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the duration from primary surgery to death owing to any cause. Patients who were still alive at the time of their last follow-up visit were censored in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the survival outcomes of patients with TNBC-RD who received adjuvant capecitabine (alone or with other chemotherapy) versus no adjuvant therapy. Propensity score methods were used to control potential confounding effects from baseline covariates [site, age at diagnosis, race, clinical stage, histology type, germline status, residual cancer burden (RCB) class, hormone receptor status at diagnosis (negative versus low), HER2 at diagnosis (IHC score 0 versus low, defined as 1+ or 2+/ISH non-amplified), hormone receptor status at surgery (negative versus low), HER2 at surgery (IHC score 0 versus low, defined as 1+ or 2+/ISH non-amplified), nodal disease at surgery, neoadjuvant anthracycline/taxane receipt]. Missing data were assessed across variables, and missing values <5% were excluded from P value calculations. For propensity score analyses, missingness was either combined with other categories or treated as a separate group when exceeding 5%. RFS, DRFS, and OS durations were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs). For each treatment group comparison, we fit a propensity score model to predict likelihood of being in each treatment group and then used inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)13 to create a pseudo-population with balanced baseline covariates (which ensured the standardized differences on key baseline variables were <0.1 between treatment groups). We considered multiple options for weights and selected matching weights, which achieved the best balance and reduced the influence of individuals with extreme propensity scores. These weights were used in the Cox proportional hazards models to obtain a propensity-adjusted estimate of the HR. The threshold for significance based on the P value was set at <0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

A total of 977 consecutive TNBC patients were identified across the databases from the three participating institutions and included in the analysis. In the total population, 316 (32.3%) experienced pCR while 661 (67.7%) had RD. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patient population are presented in Table 1. Patients with RD were significantly less likely to be gBRCA mutation carriers (P = 0.001) and had higher clinical stage (T-stage, N-stage, overall American Joint Committee on Cancer stage). Otherwise, patients with RD had similar demographic characteristics to those experiencing pCR, including age at diagnosis, race, histologic type, hormone receptor status (negative versus low), and HER2 status (IHC score 0 versus low). In terms of clinical management, as anticipated, patients with RD were less likely to undergo only sentinel node biopsy as axillary surgery and more likely to receive radiation. In terms of type of NAC, among the overall cohort (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568), the distribution of regimens was anthracycline–taxane (n = 611; 62.5%), anthracycline–taxane–platinum (180; 18.4%), and taxane–platinum (39; 4.0%), whereas 122 (12.5%) patients received single-agent therapy or an alternate regimen; of note, only five patients received adjuvant olaparib (four at DFCI, one at MDACC, zero at OSU). The proportion of patients who received an anthracycline- and taxane-based (± platinum) NAC regimen did not significantly differ by pathologic response (83.5% pCR versus 79.7% RD, P = 0.182).

Survival outcomes by response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

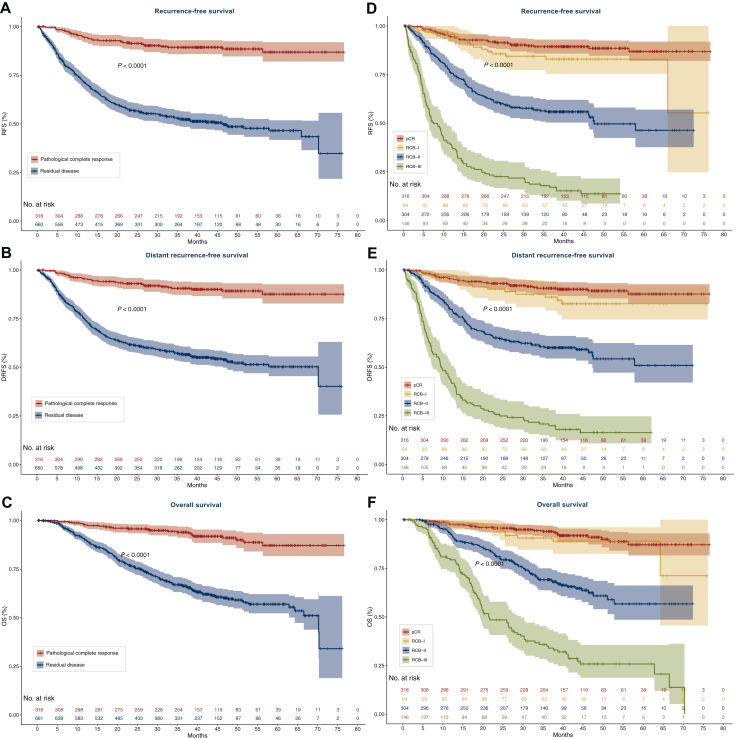

The survival outcomes in this cohort reflect the established association between pathologic response and long-term outcomes, demonstrating shorter RFS, DRFS and OS in patients with RD after NAC (Figure 1A-C, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568). With a median follow-up of 3.5 years, patients with RD had shorter RFS [HR 5.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.16-8.54, log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 1A], DRFS (HR 5.82, 95% CI 3.99-8.48, log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 1B), and OS (HR 5.43, 95% CI 3.59-8.20, log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 1C) relative to patients experiencing pCR. Landmark survival analyses at 1, 2, and 3 years confirmed the differences seen in continuous survival assessments (Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568), with shorter survival times among those with RD. Among all patients with RD, the 3-year landmark analysis demonstrated that nearly half of patients experienced a recurrence event (3-year RFS 52.3%; 3-year DRFS 56.7%), with OS rate of 66.9% at 3 years, reinforcing the critical need to improve outcomes for these patients. Compared with patients with RD, survival rates among patients who experienced pCR were higher at each landmark, with 89.3% of patients being recurrence-free at 3 years.

Figure 1.

Survival outcomes of the total cohort by response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Kaplan–Meier plots of recurrence-free survival (RFS; A/D), distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS; B/E), and overall survival (OS; C/F) stratified by pathologic complete response (pCR) versus residual disease (A-C), or residual cancer burden class (RCB; D-F). P value indicates log-rank test. Number at risk are indicated.

RCB quantifies the amount of residual cancer after NAC and is categorized into classes, from RCB-0 (pCR) to RCB-III (substantial RD). As previously described, an inverse relationship between survival rates and the degree of RD assessed by RCB class was observed (Figure 1D-F). Relative to patients with pCR, RFS, DRFS, and OS were significantly shorter in those with RCB-II (HR range 5.27, 5.09, 4.78, respectively, all Bonferroni P < 0.001); or RCB-III disease (HR range 17.6, 17.4, 14.5, respectively, all Bonferroni P < 0.001), see Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568. However, there was no significant difference in RFS, DRFS, or OS for patients with RCB-I disease compared with those who experienced pCR (all Bonferroni P > 0.25; Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568). Of note, 117 patients did not have RCB status available.

Adjuvant therapy use among patients with TNBC and RD after NAC

Among the 661 patients with RD after NAC, 298 (45.1%) did not receive adjuvant therapy, 202 (30.6%) received capecitabine alone or with other chemotherapy (189 patients received adjuvant capecitabine alone), 115 (17.4%) received other chemotherapy, and 46 (7.0%) received endocrine (for hormone receptor-low breast cancer) or other targeted therapy (Table 2). A total of 13 patients received both adjuvant capecitabine and another chemotherapy, with 12/13 given sequentially. Use of adjuvant therapy varied by institution and only a small proportion of patients with pCR received adjuvant capecitabine (5/316; 1.6%) or other chemotherapy (24/316; 7.6%) (Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568). The number of patients who initiated adjuvant capecitabine increased over the study period, from 15/223 (6.7%) total patients in 2016 to 67/156 (43.0%) total patients in 2019 (Table 3). Similarly, among the total number of patients who received capecitabine, an increase was observed over time: from 15/202 (7.4%) capecitabine initiations in 2017 to 67/202 (33.1%) capecitabine initiations in 2019 (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568).

Table 2.

Adjuvant therapy among patients with residual disease

| Residual disease by site | No adjuvant therapy, n (%) | Capecitabine alone or with other chemotherapy, n (%) | Other chemotherapy, n (%) | Endocrine/targeted therapy only, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFCI (RD 191/267, 71.5%) | 76 (39.8) | 52 (27.2) | 56 (29.3) | 7 (3.7) |

| MDACC (RD 386/553, 69.8%) | 173 (44.8) | 127 (32.9) | 50 (13.0) | 36 (9.3) |

| OSU (n = 84/157, 53.5%) | 49 (58.3) | 23 (27.4) | 9 (10.7) | 3 (3.6) |

| Total (N = 661) | 298 (45.1) | 202 (30.6) | 115 (17.4) | 46 (7.0) |

DFCI, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; MDACC, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; OSU, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center; RD, residual disease.

Table 3.

Adjuvant capecitabine use by year among patients who underwent surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Site, n patients who received capecitabine/total n patients who had surgery, (%) | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFCI (n = 52/267) | 4/75 (5.3) | 7/63 (11.1) | 18/84 (21.4) | 19/45 (42.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 |

| MDACC (n = 127/553) | 9/110 (8.2) | 20/146 (13.7) | 37/170 (21.8) | 41/90 (45.5) | 20/37 (54.1) | 0 |

| OSU (n = 23/157) | 2/38 (5.3) | 9/44 (20.5) | 5/54 (9.3) | 7/21 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 |

| Total (n = 202/977) | 15/223 (6.7) | 36/253 (14.2) | 60/308 (19.5) | 67/156 (43.0) | 20/37 (54.1) | 4 |

Survival outcomes by adjuvant therapy use among patients with TNBC and RD

For all treatment effect analyses, propensity score inverse-weighting included 13 clinical factors (see Methods). Using an IPTW treatment effect analysis, receipt of capecitabine (alone or with other chemotherapy; n = 202) was associated with significantly improved RFS (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.54-0.91, P = 0.008), DRFS (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54-0.93, P = 0.01), and OS (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49-0.90, P = 0.009) relative to patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy (n = 298) (Table 4, Supplementary Table S8, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568). In our population, the 3-year weighted RFS was 52.2% for patients who received capecitabine (alone or with other chemotherapy) versus 42.2% for patients who received no adjuvant therapy, and 3-year weighted OS was 70.0% and 54.8%, respectively.

Table 4.

Propensity adjusted treatment effect analyses for survival outcomes among patients with triple-negative breast cancer residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Adjuvant capecitabine (± other chemotherapy; n = 202) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (robust) | |

| RFS | 0.70 | 0.54-0.91 | 0.008 |

| DRFS | 0.71 | 0.54-0.93 | 0.01 |

| OS | 0.66 | 0.49-0.90 | 0.009 |

| Adjuvant capecitabine alone (n = 189) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (robust) | |

| RFS | 0.67 | 0.52-0.88 | 0.004 |

| DRFS | 0.68 | 0.51-0.90 | 0.007 |

| OS | 0.63 | 0.46-0.87 | 0.004 |

| Adjuvant capecitabine alone (n = 189) versus other adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 109) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (robust) | |

| RFS | 0.79 | 0.47-1.31 | 0.4 |

| DRFS | 0.75 | 0.44-1.29 | 0.3 |

| OS | 0.92 | 0.49-1.75 | 0.8 |

| Any adjuvant therapy (n = 363) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (robust) | |

| RFS | 0.79 | 0.62-1.00 | 0.06 |

| DRFS | 0.78 | 0.61-1.004 | 0.06 |

| OS | 0.71 | 0.54-0.93 | 0.01 |

| Adjuvant (non-capecitabine) chemotherapy (n = 109) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (robust) | |

| RFS | 0.90 | 0.57-1.42 | 0.7 |

| DRFS | 0.84 | 0.52-1.34 | 0.5 |

| OS | 0.63 | 0.37-1.08 | 0.08 |

P values that reached statistical significance (P < 0.05) are in bold.

CI, confidence interval; DRFS, distant recurrence-free survival; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Sensitivity analyses were carried out via IPTW treatment effect analysis (Table 4, Supplementary Tables S9-S12, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105568). Analysis of adjuvant capecitabine alone (n = 189) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) demonstrated similar significant association with RFS, DRFS, and OS (Table 4). Receipt of other adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 109; of which 67/109 received single-agent anthracycline, taxane, or platinum) versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) was not significantly associated with RFS (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.57-1.42, P = 0.7), DRFS (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.52-1.34, P = 0.5), or OS (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.37-1.08, P = 0.08). When comparing different adjuvant chemotherapy approaches, survival outcomes did not significantly differ between patients who received adjuvant capecitabine alone (n = 189) versus other chemotherapy (n = 109) for RFS (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.47-1.31, P = 0.4), DRFS (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.44-1.29, P = 0.3), or OS (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.49-1.75, P = 0.8). Overall, receipt of any adjuvant therapy versus no adjuvant therapy (n = 298) showed a trend toward improved outcomes for RFS (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.62-1.0, P = 0.06) and DRFS (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.61-1.004, P = 0.06), and statistically significant improvement in OS (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54-0.93, P = 0.01).

Discussion

The presence of RD after NAC remains the strongest predictor of relapse for patients with TNBC, reinforcing the critical need to identify and deliver effective therapies that are proven to reduce recurrence risk. In this study, we present results from a real-world, large population of patients diagnosed with TNBC who had RD after NAC (the majority of whom received an anthracycline- and taxane-based regimen with or without platinum). Our data confirm that the presence of RD is associated with a significantly higher risk of recurrence and mortality; for example, patients with RCB-III had a >17-fold risk of recurrence than those with pCR. Furthermore, we demonstrate that receipt of adjuvant capecitabine is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of recurrence, distant recurrence, and mortality.

This study evaluated the impact of adjuvant capecitabine on long-term outcomes in patients with TNBC-RD in a real-world setting, with some differences relative to the original CREATE-X trial population. A greater proportion of patients in CREATE-X received anthracycline- and taxane-containing NAC (95%) relative to the current study (81%). Both the current study and CREATE-X evaluated patients with HER2-negative breast cancer who had RD after receiving NAC; however, response to NAC was assessed with different grading systems. In the current study, RD was quantified using the RCB index, whereas pathologic effect grade of the Japanese Breast Cancer Society was utilized in the CREATE-X trial; thus, the distribution of RD is not readily comparable. In terms of outcomes, among patients with TNBC in CREATE-X, the 5-year DFS rate was significantly higher in patients treated with capecitabine than in the control group (69.8% versus 56.1%, HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39-0.87) and a similar trend was observed for 5-year OS (78.8% versus 70.3%, HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30-0.90).6 In our population, the 3-year weighted RFS was 52.2% for patients who received capecitabine (alone or with other chemotherapy) versus 42.2% for patients who received no adjuvant therapy, and 3-year weighted OS was 70.0% and 54.8%, respectively. Several smaller studies have not recapitulated the benefit of capecitabine observed in CREATE-X,14 reinforcing the importance of this large IPTW analysis to address the question of the impact of adjuvant capecitabine in a real-world setting.

Several large prospective trials have evaluated the efficacy of capecitabine as adjuvant therapy for TNBC. In GEICAM 2003-11/CIBOMA 2004-01,15 in patients with operable TNBC who had received prior anthracycline- and/or taxane-based chemotherapy (only 18.7% in the neoadjuvant setting), extended adjuvant therapy with capecitabine did not significantly improve DFS compared with observation in the overall study population. In a prespecified correlative analysis,16 patients with nonbasal TNBC by PAM50 seemed to derive benefit from the addition of capecitabine in terms of DRFS (HR 0.42 nonbasal versus 1.23 basal, adjusted interaction P = 0.01) but not OS (HR 0.28 nonbasal versus 0.94 basal, adjusted interaction P = 0.94). In SYSUCC-001, a randomized clinical trial of 434 women with early-stage TNBC who received standard adjuvant treatment, low-dose capecitabine maintenance therapy for 1 year, compared with observation, resulted in significantly higher 5-year DFS.17 The randomized phase III ECOG-ACRIN 1131 compared adjuvant capecitabine versus platinum in patients with TNBC-RD after NAC, with the hypothesis that patients with basal subtype TNBC (determined by PAM50) would derive greater benefit from platinum than capecitabine.18 The study was terminated early after an interim analysis revealed that additional accrual was unlikely to demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority of the platinum arm. At a median follow-up of 20 months, the 3-year invasive DFS among patients with basal subtype TNBC was 42% with platinum versus 49% with capecitabine (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.62-1.81). Of note, our study did not evaluate molecular subtypes and, while we did not see a significant difference between adjuvant capecitabine versus any other chemotherapy, this analysis was relatively underpowered. Altogether, these studies suggest that molecular subtyping (specifically nonbasal) may identify patients who are more likely to derive benefit from extended adjuvant therapy with capecitabine.

The OlympiA trial analyzed the use of olaparib in the adjuvant setting in patients with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and high-risk HER2-negative early breast cancer, who received (neo)adjuvant therapy with an anthracycline and/or a taxane.8 Patients were assigned to 1 year of adjuvant olaparib or placebo; the 3-year invasive DFS was significantly longer in patients treated with olaparib than the control group (85.9% versus 77.1%, HR 0.58, 99.5% CI 0.41-0.82).7 In the subgroup of patients with TNBC-RD post-NAC, the 3-year invasive DFS rates were 81.4% versus 67.7% (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.41-0.79). Both capecitabine (for gBRCA wild-type) and olaparib (for gBRCA mutation carriers) are considered standard adjuvant treatment for patients with TNBC-RD per current NCCN guidelines.9 The potential additive effect of utilizing olaparib and capecitabine in sequence among patients with TNBC-RD who carry a gBRCA mutation remains unclear as only five patients in this cohort received adjuvant olaparib.

In the present study, only ∼30% of potentially eligible patients received adjuvant capecitabine during the study period. This is, in part, likely due to the timing of the study, with the study period (1 January 2016–30 June 2019) starting after the CREATE-X trial was first presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in December 2015 but with ultimate publication not until June 2017. As seen in our study, a larger assessment of capecitabine utilization suggested an increase over time1; none the less only 43% of eligible patients received capecitabine in 2019 in this study. Thus, it is clear that not all potentially eligible patients receive capecitabine in routine practice, and the factors influencing this have not been well-described. A larger study investigating prescribing patterns after the publication of CREATE-X and subsequent incorporation into national guidelines is warranted to follow-up these important findings.

Despite the reported benefit of adjuvant capecitabine in CREATE-X, it is known that only a subset of eligible patients receives this therapy in the real-world setting particularly after patients have often already gone through a long course of neoadjuvant therapy. With common side-effects of hand–foot syndrome, fatigue, and mucositis, adjuvant capecitabine does not appear as well tolerated in real-world practice19 than in CREATE-X but has been suggested to be cost-effective.20 In CREATE-X, hand–foot syndrome was the most frequent adverse event (73.4%), including 49 patients (11.1%) with grade 3 events (per CTCAE v3.0), while other significant side-effects included grade 3-4 neutropenia in 6.3%, grade 3-4 diarrhea in 2.9%, and grade 3-4 leukopenia in 1.6% of patients.7,9 Of note, the specific capecitabine doses received, including dose reduction information, were not available. More recently, increased use of diclofenac gel for hand–foot prophylaxis21 and more frequent or universal testing for dihydropyrimidine deficiency before capecitabine initiation (as recently highlighted by the FDA22) may also impact patient side-effect and safety concerns.

With advances in the treatment of TNBC, modern immunotherapy drugs have been incorporated into the treatment of high-risk early TNBC. The KEYNOTE-522 trial demonstrated that the addition of the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab to NAC (with carboplatin/paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide) followed by continuation of pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting (to complete a total duration of 1 year of therapy) led to significantly higher rates of pCR (64.8% for pembrolizumab-chemotherapy versus 51.2% in the placebo-chemotherapy arm) and significantly improved 5-year event-free survival (81.2% versus 72.2%) and OS (86.6% versus 81.7%).3, 4, 5 Those patients with RCB-II appeared to derive the most benefit from the addition of pembrolizumab,23 and although most patients in our study who received adjuvant capecitabine had RCB-II or III (only ∼10% RCB-I), when considering combinatorial strategies in the adjuvant setting for RD, it is important to weigh the potential benefits and toxicities of these therapies.

To allow adequate long-term follow-up for survival, the present study was conducted before the United States Food and Drug Administration approval of pembrolizumab (July 2021) and implementation of the KEYNOTE-522 regimen for high-risk TNBC in routine practice. The clinical utility of adjuvant capecitabine in the setting of TNBC-RD after NAC plus PD-1 inhibition, and the role of a combinatorial approach with pembrolizumab, remains an important and outstanding question. Ideally, potential benefit could be refined through incorporation of biomarkers to guide adjuvant therapy selection, for example circulating tumor DNA (as seen in a post hoc analysis of the OXEL trial24 and reviewed by Parsons and Burstein25) or peripheral immune profiling. Novel agents, including antibody drug conjugates that target the human trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP-2) such as sacituzumab govitecan, datopotamab deruxtecan, or sacituzumab tirumotecan, are now being studied in combination with PD-1/programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitors in patients with TNBC-RD after NAC (± pembrolizumab) in randomized clinical trials compared with investigator’s choice of therapy of pembrolizumab ± capecitabine, and may provide further insight into the activity of capecitabine in this setting (ASCENT-05/OptimICE-RD/AFT-65, NCT05633654; SASCIA, NCT04595565; TROPION-Breast03, NCT05629585; TroFuse-012, NCT06393374).

Strengths of our study include the large sample size across the collaborating academic cancer centers and the diversity of the patient population, which included 13.5% of African Americans, broadening the generalizability of our findings. Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and relatively short follow-up of 3.5 years, although data suggest that the risk of TNBC recurrence peaks at ∼3 years after diagnosis.26 Propensity score methods adjust only for measured confounders and there could be other factors driving treatment differences that have not been accounted for, including comorbidities and socioeconomic factors. The absence of pembrolizumab and limited platinum chemotherapy use as part of the neoadjuvant regimens that patients received in this cohort impacts the ability to extrapolate the results to the modern era of treatment with chemoimmunotherapy for most patients diagnosed with early TNBC. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the most extensive dataset on real-word utilization of adjuvant capecitabine for early TNBC.

Conclusions

In this large cohort of patients with TNBC-RD after NAC, omission of adjuvant therapy was common, with less than one-third of patients receiving adjuvant capecitabine. Receipt of adjuvant capecitabine was associated with significantly improved RFS, DRFS, and OS. These results highlight the importance of adjuvant capecitabine for TNBC-RD and support continued investigation of adjuvant capecitabine benefit in the context of modern immunotherapy-containing neoadjuvant regimens.

Funding

This work was supported in part by MDACC [grant number P30CA016672]; the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Breast SPORE [grant number 1P50CA168504]; Susan G. Komen Career Catalyst Research Grant [grant number CCR19608265] to ACGC and [grant number CCR21663667] to DGS; Breast Cancer Alliance to ACGC (no grant number); the Stefanie Spielman Fund to DGS (no grant number), and the Benderson Family Fund (no grant number) at DFCI. The funders did not have any role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Kaitlyn Bifolck of DFCI for editorial and submission assistance (she is a full-time employee of DFCI).

Disclosure

PT reports research funding (to institution) from Astra Zeneca, consulting or advisory role for Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Menarini/Stemline, BioNTech, speaker honoraria from Roche, AstraZeneca and Daiichi-Sankyo. EAM reports compensated service on scientific advisory boards for Astra Zeneca, BioNTech, Merck, and Moderna; uncompensated service on steering committees for Bristol Myers Squibb and Roche/Genentech; speaker honoraria and travel support from Merck Sharp & Dohme; and institutional research support from Roche/Genentech (via SU2C grant) and Gilead; research funding from Susan Komen for the Cure for which she serves as a scientific adviser, and uncompensated participation as a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. TAK reports speaker honoraria from Exact Sciences, compensated service on the FES Steering Committee, GE Healthcare, and compensated service as faculty for PrecisCa cancer information service. VV reports research support paid to institution (Menarini, Jazz Pharmaceutical) and honoraria for consulting (Roche, Astra Zeneca). DT reports research support paid to institution (Novartis, Ambrx, Tvardi Therapueutics) and honoraria for consulting (Gilead, Menarini, Personalis, Pfizer, Roche, Sermonix, BeiGene, Novartis, Puma Biotechnology, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Ambrx). SMT reports research funding from Genentech/Roche, Merck, Exelixis, Pfizer, Lilly, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Gilead, NanoString Technologies, Seattle Genetics, OncoPep, Daiichi-Sankyo, Menarini/Stemline, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; consulting or advisory role for Novartis, Pfizer/SeaGen, Merck, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Genentech/Roche, Eisai, Bristol Myers Squibb/Systimmune, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead, Blueprint Medicines, Reveal Genomics, Sumitovant Biopharma, Artios Pharma, Menarini/Stemline, Aadi Bio, Bayer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Natera, Tango Therapeutics, eFFECTOR, Hengrui USA, Cullinan Oncology, Circle Pharma, Arvinas, BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson/Ambrx, Launch Therapeutics, Zuellig Pharma, Bicycle Therapeutics, BeiGene Therapeutics, Mersana, Summitt Therapeutics, Avenzo Therapeutics, Aktis Oncology, Celcuity, Boehringer Ingelheim, Samsung Bioepis, and Olema; and travel support from Eli Lilly, Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Arvinas, and Roche. NUL reports institutional research support from Genentech, Pfizer, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Zion Pharmaceuticals, Olema Pharmaceuticals, Astra Zeneca; consulting honoraria from Seattle Genetics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Astra Zeneca, Olema Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Blueprint Medicines, Stemline/Menarini, Artera Inc., Eisai, Shorla Oncology; royalties from UpToDate; and travel support from Olema Pharmaceuticals, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo. DS reports participation in advisory boards for Novartis, Guardant, Natera; and research funding (to institution) from Foundation Medicine and NeoGenomics, all outside of the submitted work. ACG-C reports research funding (to institution) from Gilead Sciences, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Merck & Co., Zenith Epigenetics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Biovica, Foundation Medicine, 4D Path, Precede Biosciences, and Bicycle Therapeutics; compensated service for consulting and service on scientific advisory boards for Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, and TD Cowen; speaker honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead Sciences, Roche/Genentech, and Bicycle Therapeutics; travel/other financial support from Roche/Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Merck & Co., Pfizer, and Novartis. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing

The data supporting the findings of this study are available by request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary data

DFCI, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; MDACC, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; OSU, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Rogers C., Cobb A.N., Lloren J.I.C., et al. National trends in neoadjuvant chemotherapy utilization in patients with early-stage node-negative triple-negative breast cancer: the impact of the CREATE-X trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024;203(2):317–328. doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-07114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filho O.M., Stover D.G., Asad S., et al. Association of immunophenotype with pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the BrighTNess phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):603–608. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid P., Cortes J., Pusztai L., et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):810–821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid P., Cortes J., Dent R., et al. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid P., Cortes J., Dent R., et al. Overall survival with pembrolizumab in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(21):1981–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2409932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortazar P., Zhang L., Untch M., et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masuda N., Lee S.-J., Ohtani S., et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147–2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tutt A.N.J., Garber J.E., Kaufman B., et al. Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutated breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gradishar W.J., Moran M.S., Abraham J., et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22(5):331–357. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2024.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allison K.H., Hammond M.E.H., Dowsett M., et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(12):1346–1366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff A.C., Somerfield M.R., Dowsett M., et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: ASCO–College of American Pathologists Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(22):3867–3872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolaney S.M., Garrett-Mayer E., White J., et al. Updated standardized definitions for efficacy end points (STEEP) in adjuvant breast cancer clinical trials: STEEP version 2.0. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(24):2720–2731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li L., Greene T. A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis. Int J Biostat. 2013;9(2):215–234. doi: 10.1515/ijb-2012-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taşçı E., Kutlu Y., Ölmez Ö.F., et al. Efficacy of adjuvant capecitabine in residual triple negative breast cancer: a multicenter observational Turkish Oncology Group (TOG) study. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2024;25(4):477–484. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2024.2337261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lluch A., Barrios C.H., Torrecillas L., et al. Phase III trial of adjuvant capecitabine after standard neo-/adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early triple-negative breast cancer (GEICAM/2003-11_CIBOMA/2004-01) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(3):203–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asleh K., Lluch A., Goytain A., et al. Triple-negative PAM50 non-basal breast cancer subtype predicts benefit from extended adjuvant capecitabine. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(2):389–400. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Wang S.-S., Huang H., et al. Effect of capecitabine maintenance therapy using lower dosage and higher frequency vs observation on disease-free survival among patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer who had received standard treatment: the SYSUCC-001 randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2021;325(1):50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer I.A., Zhao F., Arteaga C.L., et al. Randomized phase III postoperative trial of platinum-based chemotherapy versus capecitabine in patients with residual triple-negative breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy: ECOG-ACRIN EA1131. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(23):2539–2551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin K., Michaels E., Polley E., et al. Retrospective evaluation of adjuvant capecitabine dosing patterns in triple negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16) doi: 10.1177/10781552241289581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J.-B., Lin Z.-C., Wong M.C.S., Wang H.H.X., Li M., Li S. A cost-effectiveness analysis of capecitabine maintenance therapy versus routine follow-up for early-stage triple-negative breast cancer patients after standard treatment from a perspective of Chinese society. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02516-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santhosh A., Sharma A., Bakhshi S., et al. Topical diclofenac for prevention of capecitabine-associated Hand–Foot syndrome: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(15):1821–1829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.01730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.FDA. Safety announcement FDA highlights importance of DPD deficiency discussions with patients prior to capecitabine or 5FU treatment. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/safety-announcement-fda-highlights-importance-dpd-deficiency-discussions-patients-prior-capecitabine Available at.

- 23.Pusztai L., Denkert C., O’Shaughnessy J., et al. Event-free survival by residual cancer burden with pembrolizumab in early-stage TNBC: exploratory analysis from KEYNOTE-522. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(5):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynce F., Mainor C., Donahue R.N., et al. Adjuvant nivolumab, capecitabine or the combination in patients with residual triple-negative breast cancer: the OXEL randomized phase II study. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2691. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons H.A., Burstein H.J. Adjuvant capecitabine in triple-negative breast cancer: new strategies for tailoring treatment recommendations. J Am Med Assoc. 2021;325(1):36–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dent R., Trudeau M., Pritchard K.I., et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.