Abstract

Older patients age ≥55 account for almost half of the total MS population. While focal inflammatory demyelinating processes and progressive processes such as compartmentalized CNS inflammation, neurodegeneration, and failure of compensatory mechanisms co-occur from disease onset, there is a shift in the predominant disease processes with notable clinical progression occurring in the fifth decade of life. Clinically, this manifests in reduction in clinical relapses and MRI activity as persons with MS age, with an increase in slow disability progression independent of relapses. As disease modifying therapies have demonstrated efficacy on relapse reduction, but not centrally mediated progressive processes, the benefit of DMT wanes with age due to change in underlying biological disease processes. Contrastingly, risks of DMTs increase due to biological changes related with age, setting up a scenario where considerations on switching or stopping DMT become more clinically important based on risk-benefit ratios. This review will cover evidence regarding DMT use in older patients with MS and discuss age considerations in the management of patients with MS.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Aging, Treatment

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune mediated disease of the central nervous system, characterized by a vast array of pathophysiologic inflammatory processes that contribute to demyelination and neurodegeneration [1]. With a shift away from diagnostic bifurcation into relapsing remitting disease and progressive disease as separate subtypes and towards increased understanding that relapses and progressive disease processes co-occur [2], it has become apparent that disability accumulation occurs even earlier in the disease course. This results in phenotypic manifestation of a more clinically progressive course that becomes apparent around the fifth decade of life [3].

This progressive course is largely driven by age related changes in immune responses, neurodegeneration, and loss of compensatory mechanisms that translate into disability accumulation [2]. Immunosenescence of the adaptive immune system is characterized by reductions in B-cell populations and alterations in B-cell antibody specificity, while thymus involution results in reduction in populations of naïve T-cells and receptor diversity. Various components of the innate immune system also may manifest changes related to aging, in particular, “inflammaging” is thought to be due to alterations in macrophage function to a more pro-inflammatory state [4]. Pathologically, this is characterized by gray matter atrophy and compartmentalized CNS inflammation with slow expanding and chronic smoldering lesions [3]. While relapse frequency deceases with age [5], older individuals are at higher risk of incomplete resolution of deficits following relapses [6]. Additionally, with advancing age, inherent changes in the immune system can tilt the risk-benefit scale, to lower efficacy of anti-inflammatory immunomodulation on disability outcomes and possibly higher risks of adverse events.

As the landscape of disease modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS continues to rapidly evolve, coupled with people with MS over age 55 now making up approximately half of the total MS population [7], it is important to understand how age impacts therapeutic decision making management of MS.

Older populations and MS clinical trials

Currently approved DMTs alter the clinical course in MS by primarily reducing active inflammatory disease activity underlying clinical relapses through immunomodulation of the peripheral immune system. However, the benefit of DMTs on reducing clinical progression is limited as central progressive processes have not been targeted. Additionally, traditional outcome measures for clinical trials have focused on clinical relapses, MRI inflammatory activity, and disability reduction based on changes in disability as measured by the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) which do not adequately measure progressive processes [8]. Lastly, pivotal clinical trials have excluded older patients [9], which is a missed opportunity to target progression and disability in MS as age is a primary factor in disability accumulation in MS [10].

A few meta-analysis studies have attempted to extract efficacy data for older patients from existing clinical trials. Signori et al. [11] reviewed subgroup analyses from pivotal clinical trials, and showed there was higher reduction of disease activity in patients less than 40 years of age, compared to older patients. Weidman et al. [12] demonstrated a measurable decrease in efficacy of DMTs on MS related progression with advancing age, specifically that there did not appear to be any benefit after age 53. While Zhang et al. [13] showed that DMTs are effective on inflammatory disease activity outcomes independent of age in relapsing MS. However, the authors noted that in order to participate in relapsing trials, patients must demonstrate recent baseline disease activity, which hinders applicability to real-world patients where disease activity declines with increasing chronologic age. In the absence of clinical trial evidence, management of multiple sclerosis in older patients and decisions regarding DMT efficacy are largely based on small retrospective observational studies and clinical experience.

Another consequence of excluding older patients from clinical trials is that safety outcomes are not monitored which contribute to limited applicability to this growing population of older adults with MS. The inherent risks with immunosuppressants such as lymphopenia, infections, malignancy and overall associated comorbidities is compounded by independent age influences on these same risk factors [14,15]. Thus, there is an unmet need for MS clinical trials in populations over age 55 moving forward.

DMT discontinuation considerations

Despite lack of clinical trial efficacy data in older populations, in a 2022 study [16] of approximately 12,900 adults, 60 years or older, around 19 % received prescriptions for DMTs (10 % injectables, 6 % orals and 2.4 % infusions). Overall, the study concluded nearly 1 in 5 older adults with multiple sclerosis were prescribed DMTs with the majority receiving injectables. As changes in underlying biological processes with age are associated with reduction in peripherally mediated inflammatory disease activity, there is an associated reduction in DMT efficacy on disability progression that is independent of relapse activity. Contrastingly, there is concern for increasing risks associated with inherent compromise of the immune system with biologic aging and immunosenescence [10]. On this background, the appropriateness of continuing DMT in older patients should be re-evaluated balancing safety against the paucity of expected benefit [9].

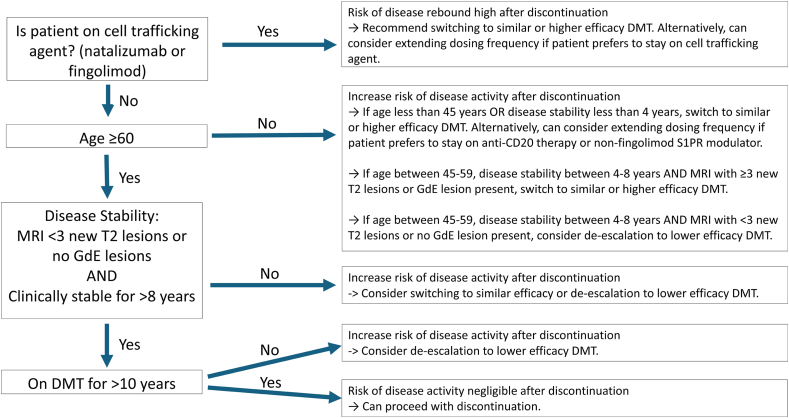

Several real-world studies on DMT discontinuation studies have been published with varying conclusions depending on the patient population studied [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. From these studies certain prognostic factors can help predict risk of relapse and disability progression in patients who discontinue DMT [20,21], specifically age, duration of disease stability, MRI activity, and duration of treatment exposure (Fig. 1). From Bsteh et al. [21], patients who were 55 and older, had less than 3 new or enlarging T2 lesions and no gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and had 8 or more years of disease stability had zero probability of disease reactivation after discontinuing interferons or glatiramer acetate therapy. Prosperini et al. [20] performed a meta-analysis of 22 real-world discontinuation studies, and demonstrated that risk of disease reactivation was negligible after the age of 60, after 10 years of treatment exposure, or after 8 years of disease stability, with 80 % of patients discontinuing from interferons or glatiramer acetate. It is important to note that these predictors may not be applicable when discontinuing from newer high efficacy therapies, as demonstrated by Jouvenot et al. [22], where risk of relapse increased in patients who discontinued cell trafficking agents of natalizumab and fingolimod, while there was no significant increase in risk of relapse after stopping anti-CD20 therapy.

Fig. 1.

Switching vs Stopping DMT In Older Patients with MS. Proposed algorithm for switching or stopping DMT in Older Patients with MS, when changing for reasons other than breakthrough disease [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. Individual patient preferences and patient specific factors are critical for shared decision making.

Two prospective clinical trials on discontinuation have also been completed. The DISCO-MS trial [23], a landmark non-inferiority trial, evaluated risks associated with DMT discontinuation in older adults with MS compared to those who remained on DMT. Individuals with MS of any clinical phenotype, 55 years or older without radiologic or clinical evidence of relapse in the prior 3 years and 5 years respectively while continuously taking approved DMT were enrolled. However, the study was unable to demonstrate non-inferiority on the primary outcome of combined disease activity. Over 90 % of participants across both groups remained clinically and radiologically stable, with only a total of 6 events in the continuation group and 16 events in the discontinuation group. Other measures such as disability progression, quality of life measures, and cognitive testing did not demonstrate clinically significant differences between continuers and discontinuers. Notably, the disease activity events were driven by MRI activity with mostly 1–2 new lesions (10.7 % in discontinuers vs 3.9 % in continuers) rather than clinical relapses (2.3 % in discontinuers vs 0.8 % in continuers). The clinical significance of new T2 lesions is difficult to determine in older patients due to the possibility of new T2 lesions being attributable to comorbid vascular processes rather than inflammatory demyelinating processes [24].

The DOT-MS [25] study was another prospective randomized clinical trial evaluating DMT discontinuation in individuals 18 years and older with at least 5 years of stable disease, while on treatment with a platform therapy (dimethyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide and interferons). The study was prematurely discontinued due to higher relapse activity in discontinuers (8/45) than in continuers (0/44) over a median follow-up of 12 months. As DOT-MS included younger patients (median age 54 years compared to median age 63 for DISCO-MS), this suggests that age remains one of the best predictors of successful DMT discontinuation. Results from the STOP-I-SEP (NCT03653273) trial, designed to evaluate DMT discontinuation in secondary progressive MS patients older than 50 years of age is pending completion in 2028.

While data suggests that discontinuation in older adults can be a successful strategy to minimize DMT risks, patients remain hesitant to stop. Individuals with MS often harbor a fear of clinical relapses and recurrent neurologic disability. Additionally, there may be a measure of psychological comfort that stems from remaining on treatment. A survey of the North American Research Committee on MS Registry (NARCOMS), with a mean age of respondents approximately 56 years, noted around 36 % of patients were unlikely or highly unlikely to discontinue DMT [26]. For those who are not ready to stop treatment for personal reasons or have a higher risk for disease activity from predictors of discontinuation (Fig. 1), but need to change therapy due to safety risks, de-escalation, in which patients are transitioned from high immunosuppression to less potent immunomodulatory DMT may be a more appropriate regimen [[27], [28], [29]]. Another method to de-escalate may be reducing the dose of DMTs by extending dose intervals of DMTs [[30], [31], [32]]. These approaches allow for individualized treatment based on multiple factors, including patient preferences and feasibility, disease activity and individual risk profiles. Yet again, there is limited data to facilitate appropriate timing of these strategies with regards to age.

Age-related safety considerations of specific disease modifying therapies (Table 1)

Table 1.

Age-related clinical considerations of disease modifying therapies.

| Disease modifying therapy | Clinical and safety considerations |

|---|---|

| Cladribine |

|

| Fumarates |

|

| Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators |

|

| Teriflunomide |

|

| Anti-cd20 therapies (ocrelizumab, rituximab, ofatumumab) |

|

| Natalizumab |

|

| Alemtuzumab |

|

Abbreviations: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), John Cunningham (JC) virus.

Cladribine

Cladribine is a highly effective lymphotoxic oral treatment agent for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. A retrospective observational study evaluated safety and effectiveness of cladribine in MS patients over 50 years of age revealed that while post-treatment lymphopenia was comparable between both older and younger cohorts, there were numerically more frequent adverse effects and infections during treatment in individuals aged more than 50 years [33]. In a post-hoc analysis of cladribine clinical trials, a risk of malignancies was observed [34], however a follow-up meta-analysis of phase 3 trials of approved DMTs and phase 3 trial of cladribine concluded that the rate of cancer development in the treatment group with cladribine was not increased compared to groups receiving other DMTs [35]. However, in a meta-analysis evaluating specific DMT risks with age [36], in depleting agents such as cladribine, the risk of malignancy is concerning after age 45. While efficacy and safety of cladribine is well-established [34,37] in clinical trial cohorts, there remains a need to evaluate this therapy in older patients, to enhance real-world applicability to a growing aging MS population.

Fumarates

Lymphopenia remains a primary safety concern with use of fumarates, as it relates to risk of serious and opportunistic infections. Particularly, lymphopenia may predispose to developing PML [38,39]. CD8+ T cells play a central role in immune surveillance and fumarate-induced suppression may interfere with protection against JC virus infection [40]. Older age >55 years, has been demonstrated as a risk factor for development of grade 3 (absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) < 500) and combined grade 2 (ALC 500–799) and grade 3 lymphopenia [41] which may relate to an age-related decline in lymphopoiesis with thymic involution [42]. A wide spectrum of other opportunistic infections with dimethyl fumarate use has also been described however association with degree of lymphopenia remains uncertain [43]. Nevertheless, monitoring of lymphocyte count every 6–12 months is recommended, and changing therapies should be considered for persistent (>6 months) ALC <500 (grade 3 or higher) [44].

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators

S1PR modulators target lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes, thereby inducing a reduction in measurable ALC [45]. Most common reasons for S1PR modulator discontinuation include significant lymphopenia, hepatic dysfunction and infections [30]. Severity of lymphopenia however, may not necessarily correlate with risk of infection [46,47]. Regardless, as ALC<200 prompted discontinuation in clinical trials, this threshold should also prompt DMT change in real world situations [47,48] due to uncertain risks with ALC<200. Extending dose interval [30] with alternate day dosing may be considered in attempt to reduce lymphopenia severity while continuing S1PR modulator therapy, but the evidence regarding clinically relevant risk of clinical or radiologic relapse with this regimen, remains conflicting [49]. With respect to age, higher risk of macular edema due to fingolimod has been found to be associated with age >41 years, and co-morbidities such as diabetes which also increases with advancing age [50]. Sustained increase in blood pressure and risk of cardiac events, may also be observed as a side effect of S1PR modulation [51].

Abrupt fingolimod discontinuation has been associated with rebound disease, which may exceed a patient's pre-DMT baseline relapse activity. This is hypothesized to occur due to rapid reentry of lymphocytes into the CNS upon drug discontinuation, although that may not fully explain this phenomenon [52]. While definitive risk factors for rebound disease have not been established, baseline high annualized relapse rate has been shown to correlate. Severe relapses may occur within 2–4 months of stopping fingolimod [53]. Multiple strategies may be undertaken to minimize this risk when planning for discontinuing fingolimod, such as withdrawal by slow titration [54] or bridging therapy with IV steroids [52]. Although the true efficacy of these measures, along with interim risk of relapse, remains unknown. Notably, rebound disease with other S1PR modulators have not been observed. Switching from fingolimod to higher efficacy therapy such as natalizumab [55], rituximab [56], and alemtuzumab [57] have been explored, however there is no large-scale data to guide sequencing algorithms. Minimizing length of washout is recommended, and there is direct association of risk of relapse increasing with washout duration when switching from fingolimod to other DMT, thus a washout period of <26 days has been suggested as a safe window to reduce risk of rebound disease [58,59].

Terflunomide

Teriflunomide is an oral immunomodulator which impacts disease control by reducing proliferation of activated lymphocytes [60]. Most common reported adverse events include transaminitis, particularly increase in ALT, gastrointestinal disorders (diarrhea, nausea), alopecia, and infections [60]. Pooled data from phase 2 and phase 3 placebo-controlled studies [61] revealed that serious infections were reported infrequently, regardless of teriflunomide dose, while serious opportunistic infections including hepatitis with cytomegalovirus, gastrointestinal tuberculosis occurred, the incidence was low and did not differ from placebo. Treatment discontinuation is recommended in patients with ALT >3x ULN [62] or suspected liver injury reflected by clinical signs and symptoms such as nausea, jaundice, abdominal pain [63]. Blood pressure elevations may be noted which requires closer monitoring and blood pressure control, particularly as hypertension risks increase with age. Serious infections may warrant treatment suspension or accelerated elimination with cholestyramine. Pulmonary symptoms such as persistent cough and dyspnea may warrant treatment discontinuation and further evaluation for infections. Severe hematologic reactions such as pancytopenia and/or bone marrow suppression may be noted which warrants discontinuing teriflunomide [64].

Anti-CD20 therapies

Anti-CD20 IgG1 monoclonal antibodies lead the therapeutic landscape among high efficacy therapies for MS. While B-cell depletion correlates with treatment effect [65], associated hypogammaglobulinemia and concordant risk of infections remain a primary safety concern [66,67]. Rituximab has been associated with increased risk of infections requiring antibiotic treatment [68]. Increased incidence of respiratory tract and herpes virus infections in MS patients treated with ocrelizumab has been reported [69]. With the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increasing need to readdress the regimens of immunomodulatory treatments as anti-CD20 therapies harbor risk of increased frequency and severity of COVID-19 infection [70]. Notably and unsurprisingly older age increases predisposition to such infections [67]. This risk may also be compounded by presence of other comorbidities such as obesity and cardiovascular risk factors [71,72], longer duration of treatment and higher EDSS scores [67]. Treatment induced lymphopenia and reduction in circulating IgM may predispose to risk of zoster in particular [73,74].

B-cell repopulation after last dose of anti-CD20 infusions typically take longer than dosing protocol of 24 weeks [75]. This paves the way for consideration for exploring extending dosing regimens based on biologically plausible markers as surrogates for treatment effect. Few studies have explored extended or personalized dosing in MS patients. Retrospective evaluations of personalized dosing of ocrelizumab during the pandemic demonstrated maintained efficacy in controlling disease activity [31,76]. CD19 cell levels have been used as surrogate markers for guiding therapy. Studies using this strategy for rituximab by re-dosing when CD19 levels rose to 1 % of total lymphocyte count did not significantly alter treatment efficacy between fixed and personalized treatment groups [77,78]. Similarly, redosing based on repopulation of CD19 B-cell count to 1 % of total lymphocyte count did not demonstrate radiologic relapse during personalized treatment of ocrelizumab [79]. De-escalation of rituximab dose can also be considered by reducing dosing from 1000 to 500 mg every 6 months, and one study demonstrated that relapse risk did not significantly change over a follow-up of 12 months [28]. A retrospective cohort study exploring delayed ocrelizumab infusion due to COVID-19 with a median interval of 7.7 months did not report increased risk of relapse during interval extension [76]. Malignancy, in particular breast cancer, may be a specific risk to ocrelizumab [80,81], and as mentioned earlier, risk of malignancy may be more of a risk after age 45 with depleting agents [36]. In post-marketing ocrelizumab experience to date, the incidence rate of malignancy and breast cancer is not increased compared to the general population (Roche communication, https://www.ocrelizumabinfo.global/en/homepage.html). While more data is needed regarding impact on efficacy balanced against enhanced safety, with personalized dosing regimens, in older patients, these strategies may be employed to minimize drug exposure and overall possibly reduce safety concerns. As discussed above, drug discontinuation is a reasonable consideration if clinical and radiologic disease stability is exhibited, and/or if infectious events requiring treatment become frequent.

Natalizumab

Safety concerns for natalizumab particularly relate to the risk of acquiring progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), as stratified by the John Cunningham (JC) virus antibody index [82]. Age has been demonstrated to be an independent factor contributing to this risk [83]. While the efficacy of natalizumab in reducing the annualized relapse rate is well-established, for older adults on this therapy who are less likely to have clinical relapses, the benefit of continuation may not be as robust. Seroconversion to positive anti-JC virus antibody status should spark a discussion with the patient, regarding risks of continuing standard interval dosing of natalizumab. There is evidence that extending infusion interval from standard dosing every 4 weeks to every 6 weeks can be safely undertaken to reduce risk of PML while maintaining efficacy in reducing relapse risk [84]. Abrupt discontinuation of natalizumab is associated with an increased risk of rebound disease, which is closely linked to baseline disease activity [85]. Alternatively, a short washout followed by transition to another DMT, may be undertaken on the road to discontinuation while minimizing risk of disabling rebound disease. Switching natalizumab to a high efficacy DMT such as an anti-CD20 therapy, may be a reasonable alternative to minimize recurrent disease activity and disability accumulation [86].

Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab impacts immunosuppression by inducing depletion of circulating B and T lymphocytes, and is a highly effective treatment for multiple sclerosis. Safety concerns beyond infusion reactions however, require a careful deliberation of risk-benefit balance when deciding on treatment course [87]. Results from the extension study of phase III trials for alemtuzumab (CARE-MS I and II) [88], reported 2 % of patients developed immune thrombocytopenia, with other most common reported side effects including infections (upper respiratory tract and urinary tract), and thyroid disorders. Risks of alemtuzumab use may be potentiated with advanced age. Post-hoc analysis from the CARE MS studies, over 8 years of alemtuzumab use, evaluated efficacy and safety in around 800 patients stratified by age. There was an age-related increase in serious infections, malignancies (malignancies including thyroid cancer, melanoma and lymphoproliferative disorders) and death, particularly in individuals over 45 years of age. Occurrence of immune thrombocytopenia did not demonstrate age-related significance. While baseline treatment protocol indicates baseline and annual skin checks, along with malignancy screening, the risk profile weighs heavily balanced against true anti-inflammatory benefit in age-concordant progressive disease [89]. Vascular events such as ischemic stroke and arterial dissection have also been reported with use of alemtuzumab [90]. It may be prudent to consider treatment discontinuation, or switch to another lower efficacy agent, if concern remains for ongoing active disease.

Socioeconomic implications of disease modifying treatment use in older patients

Beyond risks related to immunosuppression and immunomodulation, there remains a host of other clinical and socioeconomic considerations associated with the use of DMTs in older patients. Polypharmacy leading to drug-drug interactions may potentiate risk of falls [91]. Financial implications of treatment itself with cost of drug, and required surveillance while on DMT, including frequent healthcare visits for monitoring may become a prominent concern for patients. Ongoing need for transportation to and from infusion centers may be limited by local accessibility. Ensuring patients benefit from every healthcare interaction should become a mainstay focus of care, with a multidisciplinary and comprehensive approach to management beyond DMTs.

Age considerations for symptom management

Aging itself lends to an increasing burden of chronic illnesses and comorbid conditions, especially with vascular comorbidities and malignancy with MS and can further shape the functional impact of disease burden [92]. Comorbid disorders may confound evaluation, making it difficult to parse out symptoms related to progressive inflammatory CNS processes versus symptoms related to aging or other aging conditions. For example, in a real world MS cohort, multiple comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia, were noted to impact clinical outcomes such as time 25 feet walk [93]. Additionally, obesity and other vascular comorbidities are associated with accrual of disability [94]. A complete review of systems should include evaluation for commonly encountered symptoms associated with aging and MS progression, such as visual impairment, cognitive dysfunction [95], muscle spasticity, bowel, bladder and sexual dysfunction and gait impairment.

Physical and occupational therapy play a pivotal role in ensuring safe mobilization to allow for independence and thus, self-confidence in managing activities of daily living [96]. Maintained cardiorespiratory fitness, can promote stimulation of growth factors such as brain derived neurotrophic factor and limit white matter degeneration associated with biologic aging [97]. Exercise has been demonstrated to be profoundly effective in modulation of the immune system towards an anti-inflammatory physiology, overall curtailing clinical manifestations of autoimmunity and inflammation [98]. In animal models, exercise was noted to reduce inflammatory processes in the CNS and promote remyelination [99]. Both physical and cognitive symptoms related to MS may respond to goal directed neuro-rehabilitative exercise training [100]. Reducing risk of falls can improve quality of life for aging patients with MS [3]. A large majority of patients with MS experience ambulatory difficulty [101] and this is a prominent concern personally identified by persons with MS [102]. Mobility may be impacted by multiple phenomena including coordination, fatigue and gate disturbance, impacted by compromised muscle strength and muscle spasms [103]. Dalfampridine has demonstrated efficacy in improving walking speed in patients with MS independent of age [104]. Continuation should be dependent upon treatment response as clinical trials demonstrate improvement in walking speed in only about one third of the study cohort [105].

A comprehensive clinic visit should include emphasis on healthy lifestyle habits, importance of vascular risk factor management including smoking cessation and routine screening for depression and related mood disorders. Barriers to care should be identified including transportation for routine clinic monitoring, offering alternatives such as virtual visits and ensuring patients are aware of how and when to connect with their healthcare teams.

Summary

Older individuals with MS who have several years of radiologic and clinical stability, or patients with clinical progression independent of relapses despite adequate treatment, may consider DMT de-escalation or discontinuation depending on individual patient factors. As a primary stakeholder, the patient's comfort with this decision is exceedingly important. Highlighting that discontinuation of DMT does not mean that the patient is “cured of MS” or will no longer receive care, should be central to all discussions. It is important to emphasize that DMT is different from symptomatic treatment, the latter defining a mainstay of management beyond DMTs. A detailed risk and benefit discussion should be undertaken, highlighting that close clinical and radiologic surveillance will follow any decision to change DMT, with possible reinitiation with evidence of active disease. It is important to highlight the evidence-based role of exercise and goal-directed physical therapy in progressive disease, and patients should be encouraged to engage in a comprehensive treatment approach. Clinicians can consider MRI surveillance on a periodic basis, 6–12 months after DMT discontinuation or de-escalation depending and expected duration of DMT effect, and less frequently if not on DMT to monitor for new demyelinating disease activity, while remaining cognizant that increased T2 hyperintensities may be due to vascular disease and thus ensuring vascular risks are appropriately managed. Ultimately, the ongoing evolution of biomarkers of disease activity and progression will hopefully modulate and ultimately facilitate this decision-making process. Prospective randomized clinical trials in older patients are an unmet need that would improve guidance regarding DMT efficacy, safety and treatment sequencing/discontinuation as well as helping guide comprehensive care management of multiple sclerosis in a rapidly growing aging population.

Author contributions

AS: conceptualization, writing- original draft, reviewing and editing.

LHH: conceptualization, writing- original draft, reviewing and editing.

Financial disclosures

AS has no commercial or financial disclosures to report.

LHH serves/ed as a consultant to Genentech, Novartis, EMD Serono, TG Therapeutics, Horizon, and Alexion; on scientific advisory boards for Genentech, EMD Serono and Novartis; and has received non-promotional speaker honoraria for TG Therapeutics. She has received research funding paid directly to her institution from Genentech.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Le H. Hua reports a relationship with Genentech that includes: consulting or advisory and funding grants. Le H. Hua reports a relationship with Novartis that includes: consulting or advisory. Le H. Hua reports a relationship with EMD Serono Inc that includes: consulting or advisory. Le H. Hua reports a relationship with TG Therapeutics Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. Le H. Hua reports a relationship with Horizon Therapeutics USA Inc that includes: consulting or advisory. Le H. Hua reports a relationship with Alexion that includes: consulting or advisory. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

No funding associated with this work.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue on Multiple Sclerosis published in Neurotherapeutics

Special Issue: Therapeutic Advances in Multiple Sclerosis.

References

- 1.Wu G.F., Alvarez E. The immunopathophysiology of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2011 May;29(2):257–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhlmann T., Moccia M., Coetzee T., Cohen J.A., Correale J., Graves J., et al. Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023 Jan;22(1):78–88. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves J.S., Krysko K.M., Hua L.H., Absinta M., Franklin R.J.M., Segal B.M. Ageing and multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2023 Jan;22(1):66–77. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakolwiboon S., Mills E.A., Yang J., Doty J., Belkin M.I., Cho T., et al. Immunosenescence and multiple sclerosis: inflammaging for prognosis and therapeutic consideration. Front Aging. 2023 Oct 13;4 doi: 10.3389/fragi.2023.1234572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremlett H., Zhao Y., Joseph J., Devonshire V., UBCMS Clinic Neurologists Relapses in multiple sclerosis are age- and time-dependent. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008 Dec;79(12):1368–1374. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.145805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway B.L., Zeydan B., Uygunoğlu U., Novotna M., Siva A., Pittock S.J., et al. Age is a critical determinant in recovery from multiple sclerosis relapses. Mult Scler. 2019 Nov;25(13):1754–1763. doi: 10.1177/1352458518800815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallin M.T., Culpepper W.J., Campbell J.D., Nelson L.M., Langer-Gould A., Marrie R.A., et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology [Internet] 2019 Mar 5;92(10) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035. https://www.neurology.org/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035 [cited 2024 Nov 23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardini M., Cutter G., Sormani M.P. Clinical trial design for progressive MS trials. Mult Scler. 2017 Oct 1;23(12):1642–1648. doi: 10.1177/1352458517729461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schweitzer F., Laurent S., Fink G.R., Barnett M.H., Reddel S., Hartung H.P., et al. Age and the risks of high-efficacy disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019 Jun;32(3):305–312. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeydan B., Kantarci O.H. Impact of age on multiple sclerosis disease activity and progression. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020 Jul;20(7):24. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-01046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Signori A., Schiavetti I., Gallo F., Sormani M.P. Subgroups of multiple sclerosis patients with larger treatment benefits: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Neurol. 2015 Jun;22(6):960–966. doi: 10.1111/ene.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weideman A.M., Tapia-Maltos M.A., Johnson K., Greenwood M., Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y., Gonzalez Caldito N., Shirani A., Salter A., Cutter G., Culpepper W., et al. Aging and efficacy of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020 Jan;13 doi: 10.1177/1756286420969016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaughn C.B., Jakimovski D., Kavak K.S., Ramanathan M., Benedict R.H.B., Zivadinov R., et al. Epidemiology and treatment of multiple sclerosis in elderly populations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019 Jun;15(6):329–342. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grebenciucova E., Berger J.R. Immunosenescence: the role of aging in the predisposition to neuro-infectious complications arising from the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017 Aug;17(8):61. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talwar A., Earla J.R., Hutton G.J., Aparasu R.R. Prescribing of disease modifying agents in older adults with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022 Jan;57 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua L.H., Fan T.H., Conway D., Thompson N., Kinzy T.G. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler. 2019 Apr;25(5):699–708. doi: 10.1177/1352458518765656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kister I., Spelman T., Patti F., Duquette P., Trojano M., Izquierdo G., et al. Predictors of relapse and disability progression in MS patients who discontinue disease-modifying therapy. J Neurol Sci. 2018 Aug;391:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano H., Gonzalez C., Healy B.C., Glanz B.I., Weiner H.L., Chitnis T. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: effect on clinical and MRI outcomes. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019 Oct 1;35:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prosperini L., Haggiag S., Ruggieri S., Tortorella C., Gasperini C. Stopping disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world studies. CNS Drugs. 2023 Oct;37(10):915–927. doi: 10.1007/s40263-023-01038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bsteh G., Hegen H., Riedl K., Altmann P., Auer M., Berek K., et al. Quantifying the risk of disease reactivation after interferon and glatiramer acetate discontinuation in multiple sclerosis: the VIAADISC score. Eur J Neurol. 2021 May;28(5):1609–1616. doi: 10.1111/ene.14705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jouvenot G., Courbon G., Lefort M., Rollot F., Casey R., Le Page E., et al. High-efficacy therapy discontinuation vs continuation in patients 50 Years and older with nonactive MS. JAMA Neurol [Internet]. 2024 Mar 25;81(5):490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.0395. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2816799 [cited 2024 Mar 27]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corboy J.R., Fox R.J., Kister I., Cutter G.R., Morgan C.J., Seale R., et al. Risk of new disease activity in patients with multiple sclerosis who continue or discontinue disease-modifying therapies (DISCOMS): a multicentre, randomised, single-blind, phase 4, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023 Jul;22(7):568–577. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua L.H., Solomon A.J., Tenembaum S., Scalfari A., Rovira À., Rostasy K., et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected multiple sclerosis in pediatric and late-onset populations: a review. JAMA Neurol [Internet] 2024 Sep 16 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.3062. [cited 2024 Sep 16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coerver E.M.E., Fung W.H., de Beukelaar J., Bouvy W.H., Canta L.R., Gerlach O.H.H., et al. Discontinuation of first-line disease-modifying therapy in patients with stable multiple sclerosis: the DOT-MS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol [Internet] 2024 Dec 9 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.4164. [cited 2024 Dec 15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macaron G., Larochelle C., Arbour N., Galmard M., Girard J.M., Prat A., et al. Impact of aging on treatment considerations for multiple sclerosis patients. Front Neurol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1197212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vollmer B.L., Wolf A.B., Sillau S., Corboy J.R., Alvarez E. Evolution of disease modifying therapy benefits and risks: an argument for de-escalation as a treatment paradigm for patients with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2022 Jan 25;12 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.799138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Disanto G., Ripellino P., Riccitelli G.C., Sacco R., Scotti B., Fucili A., et al. De-escalating rituximab dose results in stability of clinical, radiological, and serum neurofilament levels in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021 Jul;27(8):1230–1239. doi: 10.1177/1352458520952036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacco R., Disanto G., Pravatà E., Mallucci G., Maceski A.M., Kuhle J., et al. De-escalation from anti-CD20 to cladribine tablets in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Mult Scler Relat Disord [Internet] 2024 Dec 1;92 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2024.106145. https://www.msard-journal.com/article/S2211-0348(24)00721-1/fulltext?dgcid=raven_jbs_etoc_email [cited 2024 Dec 15];. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longbrake E.E., Kantor D., Pawate S., Bradshaw M.J., von Geldern G., Chahin S., et al. Effectiveness of alternative dose fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin Pract. 2018 Apr;8(2):102–107. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Lierop Z.Y., Toorop A.A., Van Ballegoij W.J., Olde Dubbelink T.B., Strijbis E.M., De Jong B.A., et al. Personalized B-cell tailored dosing of ocrelizumab in patients with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mult Scler. 2022 Jun;28(7):1121–1125. doi: 10.1177/13524585211028833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolfes L., Pawlitzki M., Pfeuffer S., Nelke C., Lux A., Pul R., et al. Ocrelizumab extended interval dosing in multiple sclerosis in times of COVID-19. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021 Sep;8(5) doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Disanto G., Moccia M., Sacco R., Spiezia A.L., Carotenuto A., Brescia Morra V., et al. Monitoring of safety and effectiveness of cladribine in multiple sclerosis patients over 50 years. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022 Feb;58 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leist T., Cook S., Comi G., Montalban X., Giovannoni G., Nolting A., et al. Long-term safety data from the cladribine tablets clinical development program in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020 Nov;46 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebrun C., Rocher F. Cancer risk in patients with multiple sclerosis: potential impact of disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs. 2018 Oct;32(10):939–949. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prosperini L., Haggiag S., Tortorella C., Galgani S., Gasperini C. Age-related adverse events of disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis: a meta-regression. Mult Scler. 2021 Aug;27(9):1391–1402. doi: 10.1177/1352458520964778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook S., Leist T., Comi G., Montalban X., Giovannoni G., Nolting A., et al. Safety of cladribine tablets in the treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019 Apr;29:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenkranz T., Novas M., Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 9;372(15):1476–1478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1415408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Oosten B.W., Killestein J., Barkhof F., Polman C.H., Wattjes M.P. PML in a patient treated with dimethyl fumarate from a compounding pharmacy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Apr 25;368(17):1658–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1215357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin-Blondel G., Bauer J., Cuvinciuc V., Uro-Coste E., Debard A., Massip P., et al. In situ evidence of JC virus control by CD8+ T cells in PML-IRIS during HIV infection. Neurology. 2013 Sep 10;81(11):964–970. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43e6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longbrake E.E., Naismith R.T., Parks B.J., Wu G.F., Cross A.H. Dimethyl fumarate-associated lymphopenia: risk factors and clinical significance. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2015;1 doi: 10.1177/2055217315596994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakim F.T., Gress R.E. Immunosenescence: deficits in adaptive immunity in the elderly. Tissue Antigens. 2007 Sep;70(3):179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim T., Croteau D., Brinker A., Jones D.E., Lee P.R., Kortepeter C.M. Expanding spectrum of opportunistic infections associated with dimethyl fumarate. Mult Scler. 2021 Jul;27(8):1301–1305. doi: 10.1177/1352458520977132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan A., Rose J., Alvarez E., Bar-Or A., Butzkueven H., Fox R.J., et al. Lymphocyte reconstitution after DMF discontinuation in clinical trial and real-world patients with MS. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020 Dec;10(6):510–519. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brinkmann V., Billich A., Baumruker T., Heining P., Schmouder R., Francis G., et al. Fingolimod (FTY720): discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010 Nov;9(11):883–897. doi: 10.1038/nrd3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francis G., Kappos L., O'Connor P., Collins W., Tang D., Mercier F., et al. Temporal profile of lymphocyte counts and relationship with infections with fingolimod therapy. Mult Scler. 2014 Apr;20(4):471–480. doi: 10.1177/1352458513500551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox E.J., Lublin F.D., Wolinsky J.S., Cohen J.A., Williams I.M., Meng X., et al. Lymphocyte counts and infection rates: long-term fingolimod treatment in primary progressive MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019 Nov;6(6) doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtani R., Mori M., Uchida T., Uzawa A., Masuda H., Liu J., et al. Risk factors for fingolimod-induced lymphopenia in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2018;4(1) doi: 10.1177/2055217318759692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zecca C., Merlini A., Disanto G., Rodegher M., Panicari L., Romeo M.A.L., et al. Half-dose fingolimod for treating relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: observational study. Mult Scler J. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1352458517694089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zarbin M.A., Jampol L.M., Jager R.D., Reder A.T., Francis G., Collins W., et al. Ophthalmic evaluations in clinical studies of fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2013 Jul;120(7):1432–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Constantinescu V., Haase R., Akgün K., Ziemssen T. S1P receptor modulators and the cardiovascular autonomic nervous system in multiple sclerosis: a narrative review. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022 Jan;15 doi: 10.1177/17562864221133163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berger B., Baumgartner A., Rauer S., Mader I., Luetzen N., Farenkopf U., et al. Severe disease reactivation in four patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis after fingolimod cessation. J Neuroimmunol. 2015 May;282:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uygunoglu U., Tutuncu M., Altintas A., Saip S., Siva A. Factors predictive of severe multiple sclerosis disease reactivation after fingolimod cessation. Neurol. 2018 Jan;23(1):12–16. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fragoso Y.D., Adoni T., Gomes S., Goncalves M.V.M., Parolin L.F., Rosa G., et al. Severe exacerbation of multiple sclerosis following withdrawal of fingolimod. Clin Drug Invest. 2019 Sep;39(9):909–913. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Członkowska A., Smoliński Ł., Litwin T. Severe disease exacerbations in patients with multiple sclerosis after discontinuing fingolimod. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2017 Mar;51(2):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pjnns.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holmøy T., Torkildsen Ø., Zarnovicky S. Extensive multiple sclerosis reactivation after switching from fingolimod to rituximab. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/5190794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alcalá C., Gascón F., Pérez-Miralles F., Domínguez J.A., Gil-Perotín S., Casanova B. Treatment with alemtuzumab or rituximab after fingolimod withdrawal in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is effective and safe. J Neurol. 2019 Mar;266(3):726–734. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferraro D., Iaffaldano P., Guerra T., Inglese M., Capobianco M., Brescia Morra V., et al. Risk of multiple sclerosis relapses when switching from fingolimod to cell-depleting agents: the role of washout duration. J Neurol. 2022 Mar;269(3):1463–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10708-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Graille-Avy L., Boutiere C., Rigollet C., Perriguey M., Rico A., Demortiere S., et al. Effect of prior treatment with fingolimod on early and late response to rituximab/ocrelizumab in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024 May;11(3) doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chitnis T., Banwell B., Kappos L., Arnold D.L., Gücüyener K., Deiva K., et al. Safety and efficacy of teriflunomide in paediatric multiple sclerosis (TERIKIDS): a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singer B., Comi G., Miller A., Freedman M., Benamor M., Truffinet P. Teriflunomide treatment is not associated with increased risk of infections: pooled data from the teriflunomide development program (P2.194) Neurology. 2014 Apr 8;82(10_supplement):P2–P194. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vermersch P., Czlonkowska A., Grimaldi L.M., Confavreux C., Comi G., Kappos L., et al. Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler. 2014 May;20(6):705–716. doi: 10.1177/1352458513507821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan A., de Seze J., Comabella M. Teriflunomide in patients with relapsing-remitting forms of multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2016 Jan;30(1):41–51. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0299-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aubagio(R) [package insert] [Internet] Genzyme Corporation; Cambridge, MA: 2012. http://products.sanofi.us/aubagio/aubagio.pdf [cited 2017 Jul 30]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bar-Or A., Grove R.A., Austin D.J., Tolson J.M., VanMeter S.A., Lewis E.W., et al. Subcutaneous ofatumumab in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: the MIRROR study. Neurology [Internet] 2018 May 15;90(20) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005516. https://www.neurology.org/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005516 [cited 2024 Dec 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bar-Or A., Calkwood J.C., Chognot C., Evershed J., Fox E.J., Herman A., et al. Effect of ocrelizumab on vaccine responses in patients with multiple sclerosis: the VELOCE study. Neurology [Internet] 2020 Oct 6;95(14) doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010380. https://www.neurology.org/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010380 [cited 2024 Dec 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oksbjerg N.R., Nielsen S.D., Blinkenberg M., Magyari M., Sellebjerg F. Anti-CD20 antibody therapy and risk of infection in patients with demyelinating diseases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021 Jul;52 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luna G., Alping P., Burman J., Fink K., Fogdell-Hahn A., Gunnarsson M., et al. Infection risks among patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod, natalizumab, rituximab, and injectable therapies. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Feb 1;77(2):184. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ng H.S., Rosenbult C.L., Tremlett H. Safety profile of ocrelizumab for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Expet Opin Drug Saf. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):1069–1094. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1807002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Simpson-Yap S., De Brouwer E., Kalincik T., Rijke N., Hillert J.A., Walton C., et al. Associations of disease-modifying therapies with COVID-19 severity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021 Nov 9;97(19):e1870–e1885. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Louapre C., Collongues N., Stankoff B., Giannesini C., Papeix C., Bensa C., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Sep 1;77(9):1079. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salter A., Fox R.J., Newsome S.D., Halper J., Li D.K.B., Kanellis P., et al. Outcomes and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a North American Registry of patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Jun 1;78(6):699. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zoehner G., Miclea A., Salmen A., Kamber N., Diem L., Friedli C., et al. Reduced serum immunoglobulin G concentrations in multiple sclerosis: prevalence and association with disease-modifying therapy and disease course. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019 Jan;12 doi: 10.1177/1756286419878340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barmettler S., Ong M.S., Farmer J.R., Choi H., Walter J. Association of immunoglobulin levels, infectious risk, and mortality with rituximab and hypogammaglobulinemia. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gibiansky E., Petry C., Mercier F., Günther A., Herman A., Kappos L., et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing and primary progressive multiple sclerosis: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses of OPERA I, OPERA II and ORATORIO. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jun;87(6):2511–2520. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barun B., Gabelić T., Adamec I., Babić A., Lalić H., Batinić D., et al. Influence of delaying ocrelizumab dosing in multiple sclerosis due to COVID-19 pandemics on clinical and laboratory effectiveness. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021 Feb;48 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zecca C., Bovis F., Novi G., Capobianco M., Lanzillo R., Frau J., et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with rituximab: a multicentric Italian–Swiss experience. Mult Scler. 2020 Oct;26(12):1519–1531. doi: 10.1177/1352458519872889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boremalm M., Sundström P., Salzer J. Discontinuation and dose reduction of rituximab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2021 Jun;268(6):2161–2168. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tazza F., Lapucci C., Cellerino M., Boffa G., Novi G., Poire I., et al. Personalizing ocrelizumab treatment in Multiple Sclerosis: what can we learn from Sars-Cov2 pandemic? J Neurol Sci. 2021 Aug;427 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Montalban X., Hauser S.L., Kappos L., Arnold D.L., Bar-Or A., Comi G., et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376(3):209–220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hauser S.L., Bar-Or A., Comi G., Giovannoni G., Hartung H.P., Hemmer B., et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376(3):221–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prosperini L., De Rossi N., Scarpazza C., Moiola L., Cosottini M., Gerevini S., et al. Natalizumab-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: findings from an Italian independent Registry. Aktas O., editor. PLoS One. 2016 Dec 20;11(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mills E.A., Mao-Draayer Y. Aging and lymphocyte changes by immunomodulatory therapies impact PML risk in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2018 Jul;24(8):1014–1022. doi: 10.1177/1352458518775550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Foley J.F., Defer G., Ryerson L.Z., Cohen J.A., Arnold D.L., Butzkueven H., et al. Comparison of switching to 6-week dosing of natalizumab versus continuing with 4-week dosing in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (NOVA): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Jul;21(7):608–619. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prosperini L., Kinkel R.P., Miravalle A.A., Iaffaldano P., Fantaccini S. Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12 doi: 10.1177/1756286419837809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hersh C.M., Harris H., Conway D., Hua L.H. Effect of switching from natalizumab to moderate- vs high-efficacy DMT in clinical practice. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020 Dec;10(6):e53–e65. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hersh C.M., Cohen J.A. Alemtuzumab for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Immunotherapy. 2014;6(3):249–259. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coles A.J., Arnold D.L., Bass A.D., Boster A.L., Compston D.A.S., Fernández Ó., et al. Efficacy and safety of alemtuzumab over 6 years: final results of the 4-year CARE-MS extension trial. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14 doi: 10.1177/1756286420982134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bass A.D., Arroyo R., Boster A.L., Boyko A.N., Eichau S., Ionete C., et al. Alemtuzumab outcomes by age: post hoc analysis from the randomized CARE-MS studies over 8 years. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021 Apr;49 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lemtrada(R) [package insert] [Internet] Genzyme Corporation: A Sanofi Company; Cambridge, MA: 2001. https://products.sanofi.us/lemtrada/lemtrada.pdf [cited 2024 Dec 7]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cameron M.H., Karstens L., Hoang P., Bourdette D., Lord S. Medications are associated with falls in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015 Sep 1;17(5):207–214. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2014-076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marrie R.A. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: implications for patient care. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017 Jun;13(6):375–382. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conway D.S., Thompson N.R., Cohen J.A. Influence of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and obstructive lung disease on multiple sclerosis disease course. Mult Scler. 2017 Feb;23(2):277–285. doi: 10.1177/1352458516650512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Geraldes R., Esiri M.M., Perera R., Yee S.A., Jenkins D., Palace J., et al. Vascular disease and multiple sclerosis: a post-mortem study exploring their relationships. Brain. 2020 Oct 1;143(10):2998–3012. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tremblay A., Charest K., Brando E., Roger E., Duquette P., Rouleau I. The effects of aging and disease duration on cognition in multiple sclerosis. Brain Cogn. 2020 Dec;146 doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2020.105650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Siddiqui A., Yang J.H., Hua L.H., Graves J.S. Clinical and treatment considerations for the pediatric and aging patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2024 Feb;42(1):255–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2023.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shobeiri P., Karimi A., Momtazmanesh S., Teixeira A.L., Teunissen C.E., van Wegen E.E.H., et al. Exercise-induced increase in blood-based brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention trials. PLoS One. 2022;17(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duggal N.A., Niemiro G., Harridge S.D.R., Simpson R.J., Lord J.M. Can physical activity ameliorate immunosenescence and thereby reduce age-related multi-morbidity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2019 Sep;19(9):563–572. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lozinski B.M., De Almeida L.G.N., Silva C., Dong Y., Brown D., Chopra S., et al. Exercise rapidly alters proteomes in mice following spinal cord demyelination. Sci Rep. 2021 Mar 31;11(1):7239. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86593-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dalgas U., Stenager E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012 Mar;5(2):81–95. doi: 10.1177/1756285611430719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hemmett L., Holmes J., Barnes M., Russell N. What drives quality of life in multiple sclerosis? QJM: Int J Med. 2004 Oct;97(10):671–676. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bloom L.F., Lapierre N.M., Wilson K.G., Curran D., DeForge D.A., Blackmer J. Concordance in goal setting between patients with multiple sclerosis and their rehabilitation team. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Oct;85(10):807–813. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000237871.91829.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Simon R.P., Greenberg D.A., Aminoff M.J., editors. Clinical neurology. seventh ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2009. p. 348. Neurologic investigations. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goodman A.D., Brown T.R., Schapiro R.T., Klingler M., Cohen R., Blight A.R. A pooled analysis of two phase 3 clinical trials of dalfampridine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(3):153–160. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2013-023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pikoulas T.E., Fuller M.A. Dalfampridine: a medication to improve walking in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jul;46(7–8):1010–1015. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]