Abstract

Understanding the metabolism of endogenous and exogenous substances in the human body is essential for elucidating disease mechanisms and evaluating the safety and efficacy of drug candidates during the drug development process. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques, have introduced innovative approaches to metabolism research, enabling more accurate predictions and insights. This paper emphasizes computational and AI-driven methodologies, highlighting how ML enhances predictive modeling for human metabolism at the molecular level and facilitates integration into genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) at the omics level. Challenges still remain, including data heterogeneity and model interpretability. This work aims to provide valuable insights and references for researchers in drug discovery and development, ultimately contributing to the advancement of precision medicine.

Keywords: Metabolism prediction, Artificial intelligence, Human genome-scale metabolic models, Disease mechanisms, Drug development, Cheminformatics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Metabolic prediction's complexity is a barrier to reliable clinical and research application.

-

•

Deep learning advances predictions of xenobiotic metabolism and rule-based methods remain vital.

-

•

AI integration into GEMs advances their use in precision medicine.

1. Introduction

Human metabolism encompasses a complex network of biochemical transformations that regulate both endogenous processes, such as glucose homeostasis and amino acid synthesis [1], and the processing of exogenous substances, including drug detoxification and xenobiotic metabolism [2]. The relationship between these two metabolic pathways is crucial, as endogenous metabolic functions can be significantly influenced by external factors, including dietary components and environmental exposures. This intricate interplay highlights the complexity of metabolic processes and their integration, which is essential for understanding individual variations in metabolic responses and their implications for health and disease [3]. Endogenous and exogenous metabolic pathways exhibit similarities in their enzymatic machinery and network architecture. Both systems rely on phase I (oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis) and phase II (conjugation) reactions. Most importantly, cytochrome P450s family enzymes (CYPs) 1–3, playing a critical role in the biotransformation of 70%–80% of phase I metabolism for clinically used drugs, also involved in the metabolism of numerous xenobiotic and endogenous compounds [4]. For instance, CYP3A4, a key enzyme in drug metabolism, also participates in cholesterol synthesis and bile acid regulation [5].

Current methodologies in metabolic analysis have evolved significantly across experimental and computational domains. In vitro metabolic studies typically employ liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for metabolite detection [6]. Then, multivariate statistical analysis, such as principal component analysis (PCA) is applied to decipher metabolic patterns from complex datasets derived from preclinical models [7]. The advent of advanced analytical platforms has further expanded metabolic investigation capabilities. Single-cell metabolomics enables resolution of cellular heterogeneity in metabolic responses [8]. Metabolic flux analysis quantifies pathway dynamics in real time [9]. Spatial metabolomics maps metabolite distributions within tissue microenvironments [10]. These technological advancements synergistically enhance our capacity to interrogate metabolism's multifaceted roles in disease research and pharmaceutical development [11,12]. First, in biomarker discovery and mechanistic elucidation, systematic analysis of metabolic dysregulation enables identification of disease-specific biomarkers and reveals pathogenic mechanisms through metabolic network reconstruction [13]. Second, in therapeutic optimization, strategic manipulation of metabolic pathways facilitates rational drug design. For example, prodrugs can translate from inactive compounds into active drugs for therapeutic effect, while soft drugs are designed to undergo rapid metabolic inactivation to minimize systemic toxicity [14]. Third, in translational pharmacology, comprehensive metabolic characterization is imperative for evaluating drug safety and efficacy profiles, requiring integration of in vitro-in vivo extrapolation and interspecies metabolic comparisons [15]. Looking ahead, whether predicting endogenous metabolism or xenobiotic/drug metabolism, the reconstruction of knowledge systems and the development of predictive models from various perspectives can accelerate research progress.

For drug metabolism, recent advances in computational and artificial intelligence (AI) methods, including molecular docking, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling [16], machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) [17], are improving metabolism predictions in humans and enhancing drug development processes [14]. There are already a large number of mature methods to predict the metabolism fate of compounds in the human body, and the tasks include substrate and inhibitor prediction, sites of metabolism (SOMs) prediction, and metabolites prediction [18].

For endogenous metabolism, with the development of multi-omics technology, the development of metabolomics gives us more chances to simulate human metabolism. Metabolites (metabolites in omics refer to the reactants and products of metabolic reactions) [19] can produce signals that are received at other omics levels [20], while metabolic feedback can compensate or modify genetic and environmental signals through complex, non-intuitive pathways [21]. Unfortunately, metabolite detection at the omics scale is still immature and has significant limitations. The primary challenges lie in the high biochemical heterogeneity [22] and the concentration variations that can occur on short timescales [23], which result in significant changes in metabolic profiles. Also, traditional metabolite analysis can be subject to sampling or technology-specific systemic errors, such as batch effects [24], which can affect overall data quality. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]] simulate metabolic processes and systematically map interactions within the metabolic network by integrating gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations, thereby enabling a mechanistic exploration of metabolic crosstalk. GEMs also can calculate metabolic flux under steady-state conditions, providing insights into the metabolic capabilities of organisms. These analyses include transcriptional data from patient and healthy tissues, studies of the genetic characteristics of cells, and accurate simulations of cell growth and metabolite exchange rates [25]. Computational methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA) have been used to estimate metabolic flux from bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data [32]. FBA could be used as an exploratory tool for specific disease treatment such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and cancer [33,34]. It also provides the possibility for the localization of drug targets such as metabolic enzymes [35,36]. However, FBA has limitations, particularly in predicting energy flow, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, and challenges remain in accurately describing cellular metabolic states in an operable and interpretable manner. Static measurements of dynamic biochemical reaction networks require more precise definitions of reaction rates and regulatory factors.

We aim to provide a detailed overview of metabolism in the human body, identify the challenges in metabolism prediction, summarize the comprehensive database in the field of human metabolism, and explore the computational and AI models that enhance our understanding and prediction of metabolic processes. While analyzing the metabolic prediction methods at the molecular level, we also analyze and prospect the role of GEMs in drug development.

2. Metabolism in the human body

The metabolic process in the human body takes place mainly in the liver in two phases, catalyzed by a series of enzymes [37], as shown in Fig. 1A. The phase I metabolism includes oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis, and hydration reactions, as well as some rare reactions such as isomerization, dimerization, and decarboxylation. The most important metabolizing enzymes in phase I are the CYPs, and most of the metabolic reactions are mediated by CYP to obtain metabolites, some of which may have the potential to be toxic [38]. CYPs are a class of heme-containing enzymes responsible for catalyzing the oxidation of both endogenous substances and exogenous compounds, such as drugs. Among these enzymes, CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2 play a particularly significant role, collectively accounting for approximately 95% of drug oxidation within the body [39]. Non-CYPs such as aldehyde oxidases (AOXs), alcohol dehydrogenase, and monoamine oxidase can also catalyze drug oxidation. The enzymes involved in phase II metabolism are mainly uridine diphosphate glucuronyltransferase (UGT), sulfate transferase (SULT), and glutathione-S-transferase (GST). Some drugs may cause toxic side effects in phase I due to intermediate metabolites. The metabolic process produces activated intermediates that covalently bind to biological macromolecules in the body, damaging the structure of proteins, DNA, etc., and ultimately leading to drug toxicity and side effects [40]. Phase II reaction can function as a drug detoxification process [38]. In phase II, glutathione acts as an endogenous detoxifying agent, which is covalently bound to the electrophilic moiety of toxic metabolites through sulfhydryl bonds, thereby rendering them biologically inactive and facilitating their excretion from the body [41].

Fig. 1.

General schematic diagram of metabolism in humans and an overview of tasks for exploring the process of metabolism. (A) Overview of the metabolic process in humans, highlighting the important organs involved and the significant types of metabolic reactions. (B) Challenges in metabolism prediction. (C, D) The main tasks of metabolism prediction at the molecular level (C) and omics level (D), along with the techniques used for model construction.(E) Diagram illustrating the aims of exploring gene-scale metabolism and the objectives of metabolism prediction methods. R: compound molecule; O: oxygen atom; G: glutathione; SH: sulfydryl; NH2: amido; OH: hydroxyl; GI: glucose; Ac: acyl; SO3H: sulpho; SOMs: sites of metabolism; ML: machine learning; MD: molecular dynamics. We thank Home for Researchers (www.home-for-researchers.com) and Servier Medical Art (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) for providing the materials used in the schematic drawings.

In addition to the metabolism in the liver, the human body has tens of thousands of microorganisms in various parts of the body, including the skin, saliva, and oral mucosa, most of which are present in the gastrointestinal tract and perform metabolic functions [42]. Studies have shown that the metabolic capacity of the intestinal flora far exceeds that of human cells [43]. The intestinal flora can interfere with both the absorption of energy and the extraction of essential nutrients from food in the body, as well as regulate the metabolic mechanisms of the host by metabolizing drugs. At least 40 therapeutic drugs have been documented in the microbiome database as being metabolized by intestinal microorganisms [44]. Active metabolites produced by the intestinal flora can both promote and impair health, directly or indirectly affecting the host physiology [45]. Human gut microbes produce bioactive compounds such as bile acids, short-chain fatty acids, ammonia, phenols, and endotoxins through the fermentation of dietary fiber [46]. In addition, gut microflora play a role in the catabolism of amino acids by deamination or decarboxylation to produce carboxylic acids, ammonia or amines, and carbon dioxide [47]. Intestinal microorganisms also possess lipases that degrade triglycerides and phospholipids into polar head groups and free lipids during lipolytic metabolism [48].

In the process of drug development for oral administration, first-pass metabolism is an important research content (Fig. 1A). After being absorbed from the gastrointestinal lumen, drug molecules that are taken up by the capillary beds in the small and large intestine need to undergo hepatic portal vein transit through the liver before reaching the rest of the body [49]. CYP3A, esterase, amidase, glucuronyltransferase, and sulfotransferase play crucial roles in the first-pass metabolism within the gastrointestinal tract [49,50]. For example, the primary metabolic pathway of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitor saquinavir in the human liver is mediated by CYP3A [51], and intestinal esterase plays a significant role in metabolizing aspirin to salicylic acid during its initial passage [49,50].

In addition to studying at the molecular level, metabolism can also be explored at the omics level. Metabolic processes in the body are regulated by genetic factors, which influence metabolic pathways and contribute to phenotypic variation [10]. Metabolic abnormalities are significant contributors to tissue dysfunction in various diseases, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer [10]. With the development of metabolic analysis techniques and the application of new techniques in metabolic studies, it is possible to delineate the metabolic changes associated with disease in detail, such as the measurement of metabolic changes in vivo using stable isotope tracer technology [52]. These advances have improved our understanding of metabolic disease mechanisms and led to new treatments for a variety of diseases. A typical example is the mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1) or IDH2 in gliomas and other malignancies, and metabolomic analysis has shown that the mutants IDH1 and IDH2 convert α-ketoglutaric acid to d-2-hydroxy-glutaric acid (D-2HG), resulting in a large accumulation of this normally scarce metabolite [53,54]. Today's technology makes it possible to measure d-2HG levels clinically to track disease progression, and drugs that inhibit the mutated enzyme are used to treat leukemia [55]. Recently, researchers have concluded that the metabolism of intrinsic tumor cells, interactions between cancer cells and non-cancerous cells in the tumor microenvironment, and whole-systemic metabolic homeostasis regulate cancer progression and may lead to cancer-associated cachexia, and detection of these metabolic changes is beneficial for disease detection and monitoring [56].

This section highlights the complexity of human metabolism, primarily occurring in the liver through phase I and phase II reactions, with CYPs playing a crucial role in drug metabolism. Additionally, the gut microbiome significantly contributes to metabolic processes, influencing drug absorption and health outcomes. Advances in metabolic analysis techniques, including omics approaches, have enhanced our understanding of metabolic abnormalities associated with diseases, leading to potential therapeutic strategies. Overall, these insights into metabolic mechanisms can guide the development of new treatments and improve disease management.

3. Challenges in metabolism prediction

Metabolism is a complex process influenced by various factors that can significantly affect both xenobiotic processing such as drug metabolism and endogenous metabolism (Fig. 1B). Understanding these challenges is crucial for accurate predictions of metabolic responses.

Biological sex can lead to variations in metabolic rates and pathways, influencing how drugs and endogenous substances are processed [57,58]. Hormonal differences, particularly in estrogen and testosterone levels, can affect enzyme activity and metabolic capacity [59]. Aging is associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. As individuals age, they may experience metabolic dysregulation due to mitochondrial dysfunction, altered nutrient sensing, and insulin resistance [60,61]. The liver, as a central metabolic organ, shows progressive metabolic changes, including triglyceride accumulation and impaired fatty acid oxidation [62]. Age-related changes in circadian rhythms disrupt clock gene rhythms. For example, aging complicates metabolic processes by impairing lipid metabolism and, along with liver disease, compromising the metabolic capacity for drugs and endogenous compounds [63]. Circadian variations significantly impact metabolic processes, particularly the activity of CYPs involved in drug metabolism [64]. These enzymes exhibit rhythmic expression patterns that can influence the timing and efficacy of drug metabolism throughout the day [65]. During pregnancy, metabolic adaptations are crucial for supporting the developing embryo. Significant changes occur in metabolic gene expression across maternal organs and the placenta, affecting both drug metabolism and the regulation of nutrients [66].

In summary, the interplay of biological sex differences, age, biological rhythms, pregnancy, and comorbidities presents significant obstacles in predicting metabolic outcomes. These factors must be carefully considered to ensure accurate assessments in both clinical and research settings. Current calculation methods do not specifically take these factors into account, which complicates the metabolic predictions and may lead to inaccuracies.

4. Computational and AI models for metabolism prediction

Although drug metabolism and endogenous metabolism are very different, they are based on a similar database basis. Below, we highlight key categories and applications of databases, with a comparative summary provided in Table 1 [37,[67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77]]. There are different methods and applications to simulate metabolic processes (at both molecular and omics levels). In recent years, the field of metabolism prediction has witnessed an increasing application of computational and AI technology [78,79]. In terms of metabolism prediction at the molecular level, computational techniques such as QSAR modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are employed. Meanwhile, AI has found applications in metabolism prediction through ML and DL models. Especially, strategies like multitask learning are utilized, and graph-based models have proven to be helpful. We divide the molecular level methods into three tasks as in the previous study [18,80]: the prediction of substrates or inhibitors, the prediction of SOMs, and the prediction of metabolites (Fig. 1C). These tasks are summarized in three separate tables: Table 2 [[81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88]] presents computational approaches for metabolism prediction at the molecular level, Table 3 [[89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]] shows the tools for predicting SOM, and Table 4 [[74], [96], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111]] includes computational methods for predicting drug metabolites. However, in the article, we present them in two categories: ligand-based and binding site-based approaches. Alternatively, metabolic modeling is a widely used approach for predicting metabolism at the omics level, as it is grounded in the understanding of the relationships between connections and network topologies among molecular mechanisms across various levels (Fig. 1D). There are also some computational techniques, such as FBA [32], still requiring a more precise definition of reaction rates and regulatory factors. Fig. 1E outlines the critical role of metabolism studies in understanding disease mechanisms, identifying potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and guiding the development of targeted drug therapies, ultimately contributing to personalized medicine. The methods applied at the molecular level and omics level are both described in detail in the following section.

Table 1.

Databases related to human metabolism.

| Category | Database | Key data scope | Access | URLs | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous metabolism | HMDB | 5,180 metabolites; enzyme-literature links | Public | https://hmdb.ca/ | [67] |

| MetaCyc | 2,722 pathways; 17,000 reactions | Public | https://metacyc.org/ | [68] | |

| VMH | Genome-reaction mappings; clinical data | Public | https://vmh.life/ | [69] | |

| KEGG | Metabolic pathways for all metabolites of various compounds | https://www.genome.jp/kegg/ligand.html | [70] | ||

| Drug metabolism | DrugBank | 14,000 drug entries and 77,084 drug metabolism data | Public/Partial | https://go.drugbank.com/pharmaco/metabolomics | [71] |

| SuperCYP | 1,170 drugs with more than 3,800 interactions | Public | http://bioinformatics.charite.de/supercyp | [72] | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism | Metrabase | 3,437 compounds, 20 transporters, and 13 CYPs | Public | https://www-metrabase.ch.cam.ac.uk/ | [73] |

| MetXBioDB | 2,134 biotransformation data | Public, released by BioTransformer [74] | https://bitbucket.org/djoumbou/biotransformerjar/src/master/ | [74] | |

| XMetDB | Substrate-product pairs; reaction mechanisms | Public | http://github.com/xmetdb/xmetdb-server | [37] | |

| Cancer metabolism | CAMP | 988 tumor/normal tissues; 11 cancer types | Public | Benedetti et al. [75] | [75] |

| Commercial platforms | Integrity | 490,000 bioactive compounds; >2,000,000 bioassays | Commercial | https://integrity.clarivate.com/ | [76] |

| MDDR distributed by Dassault Systemes | 233,000 drug candidates; exogenous reactions | Commercial | http://www.akosgmbh.de/accelrys/databases/metabolite.htm | [77] |

HMDB: Human Metabolome Database; VMH: Virtual Metabolic Human; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; CYP: cytochrome P450s family enzymes; CAMP: Cancer Atlas of Metabolic Profiles; MDDR: MDL Drug Data Report.

Table 2.

Summary of computational approaches for metabolism prediction at the molecular level, including methodologies and target enzyme specificity.

| Method | Core components | Coverage | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADMETlab | MGA framework | Variety of CYPs | A classical web tool including some ADMET properties. The evaluation metric AUC is from 0.737 to 0.928 for classification of CYP inhibitor/substrate. | [81] |

| SuperCYPsPred | MACCS or Morgan fingerprints with ensemble learning algorithms | CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4 | A website dedicated to predicting CYP specificity, which also includes DDI predictions. | [82] |

| admetSAR | CLMGraph | Variety of CYPs | A classical web tool including some ADMET properties. To automatically optimize the ADMET properties of the query molecule through transformation rules or scaffold jumps. | [83] |

| pkCSM | Graph-based signatures | Variety of CYPs | A website dedicated to predicting ADMET properties; computes and combines two descriptors for general molecular properties and distance-based graph signatures. | [84] |

| Martiny et al. [85] | Combined ligand and binding-site based model | CYP2D6 | Modeling was performed using SVM, RF, and NaiveBayesian based on the 2D molecular fingerprints of known CYP2D6 inhibitors and the predicted binding energy of conformational binding obtained by docking X-ray and MD simulations. | [85] |

| Rakers et al. [86]. | 3D pharmacophores and basic descriptors | SULT1E1 | MD simulation and conformation clustering were used to find a suitable conformation for interlocking. Pharmacophore scores and molecular descriptors were used as feature inputs. SVM was selected for the model. | [86] |

| Dudas et al. [87] | Features include molecule descriptors and score of IE computed by docking-scoring for each compound in each protein conformation | UGT 1A1 | ML and structure-based modeling for the prediction of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition. | [87] |

| Martiny et al. [88] | Features include protein-ligand interaction energy by using docking | SULT1A1, SULT1A3, and SULT1E1 | Input features are fingerprint descriptors (ECFPs) and binding energies and ML models SVM, RF, and NB. | [88] |

MGA: multi-task graph attention; CYP: cytochrome P450s family enzymes; ADMET: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity; AUC: area under the curve; MACCS: Molecular ACCess System; DDI: drug-drug interaction; CLMGraph: a contrastive learning based multi-task graph neural network (GNN) framework; SVM: support vector machine; RF: random forest; 2D: two-dimensional; MD: molecular dynamics; SULT1E1: sulfate transferase 1E1; IE: interaction energies; UGT1A1: uridine diphosphate glucuronyltransferase 1A1; ML: machine learning; UDP: uridine diphosphate; ECFPs: Extended-connectivity fingerprints; NB: naive Bayes.

Table 3.

Comparative overview of tools for predicting site of metabolism (SOM), including core features, enzyme coverage, and methodological descriptions.

| Method | Core components | Coverage | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metasite | Molecular interaction fields and reactivity estimator | Variety of CYPs | Provides a tool for predicting SOM and understanding compound metabolism by integrating protein structure-derived MIFs and molecular orbital calculations. | [89] |

| CypScore | Surface electrostatics and semi-empirical method | Individual CYP reactions | A set of six MLR models has been compiled to encompass the primary reaction types catalyzed by CYPs. | [90] |

| Metaprint2D | Atom mapping and statistical model | Phases I + II | By mining extensive biotransformation databases, determined the likelihood of metabolic transformations for atoms with specific atomic environments. | [91] |

| RD-Metabolizer | 2D fingerprint similarity calculation with model reaction SMARTS patterns | Phases I + II | RS-Predictor focuses on CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6, combining topological atomic fingerprinting of SMARTS patterns, and quantum chemical descriptors with support vector machines to rank oxidative metabolic sites. | [92] |

| SMARTCyp | DFT-derived reaction energies | CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 |

Utilizes a combined framework to assess the likelihood of chemical reactions, incorporating precomputed activation energies and topological accessibility descriptor. | [93] |

| RS-WebPredictor | MIRank (SVM) | CYP1A2, CYP2A6,CYP2B6, CYP2C8, YP2C9, CYP2C19,CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 | A range of pre-trained SVM models, incorporating topological descriptors and SMARTCyp reactivities, are utilized to predict SOMs. | [94] |

| IDSite | Glide docking and physical-based score | CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP 3A4 | Samples the conformational space and evaluates the potential of atoms to react with the catalytic iron center. Also show 3D structures of the protein ligand complex. | [95] |

| CypReact | LMB algorithm | CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 | Accurately predicts the likelihood of a reaction occurring between the query molecule and one specified enzyme of nine different CYP kinds. | [96] |

| XenoSite | Neural networks | CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 | As an improvement to prior methods RS-Predictor of predicting CYP-mediated SOM by using new descriptors and ML based on neural networks. XenoSite uses neural networks to predict SOMs for nine CYPs based on a database of 680 substrates and metabolites. It integrates various descriptors and outperforms RS-Predictor in training speed and accuracy. | [97] |

| SOMP | Bayesian | CYP1A, CYP12C9, CYP2C19, CYP1D6, CYP3A4, and UGT | By employing LMNA descriptors, the method captures the structure of more than 1000 metabolized xenobiotics. The PASS algorithm to analyze structure-SOM relationships for enzymes such as CYP1A2 and UGT. The Bayesian classifier uses both positive and negative data from literature and databases. | [98] |

| FAME3 | RF | Phases I + II | FAME uses 79,238 reaction data and random forest algorithms to predict phase I and II metabolic reactions. It originally used seven atomic descriptors but has expanded in FAME3 to 15 descriptors and introduced FAMEscore for accuracy evaluation. FAME3 employs an ensemble of extra trees classifiers to predict metabolic sites in various small molecules, including drugs and natural products. | [99] |

| Xu et al. [100] | Decision tree model | AOX | Multiple SOMs within a single compound can be identified and metabolic regional selectivity explained. | [100] |

CYP: cytochrome P450s family enzymes; MIFs: molecular interaction fields; MLR: multiple linear regression; RD: reaction database; 2D: two-dimensional; SMARTS: simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) arbitrary target specification; RS-Predictor: RegioSelectivity-Predictor; DFT: density functional theory; RS: regioselectivity; SVM: support vector machine; LMB: learning based model; ML: machine learning; SOMP: site of metabolism predictor; UGT: uridine diphosphate glucuronyltransferase; LMNA: labeled multilevel neighborhoods of atoms; PASS: prediction of activity spectra for substances; FAME3: FAst Metabolizer 3; RF: random forest; AOX: aldehyde oxidase.

Table 4.

Detailed overview of computational methods for predicting drug metabolites, including core components, enzyme coverage, and method descriptions.

| Method | Core components | Coverage | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMES | Knowledge-based system | Phases I + II | Utilizes a biotransformation library and a heuristic algorithm to generate metabolic maps. | [101] |

| SyGMa | Knowledge-based system | Phases I + II | SyGMa is an early rule-based method for predicting metabolites, utilizing 6,187 metabolic reactions from the MDL database. It generates reaction rules through manual optimization, encoding them in the Daylight SMIRKS language. The method applies these rules to reactants and scores them to evaluate reaction likelihood, optimizing less probable rules to yield 144 final reaction rules. | [102] |

| UM-PSS | Knowledge-based system | Microbial catabolism of organic compounds | Predicts possible metabolite structures using reasoning models based on argumentation logic and using biotransformation rules. | [103] |

| MetaTox | Knowledge-based system with algorithm of PASS software (Bayesian-like approach) |

CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and UDP | Utilizes the structural formula of chemicals to predict xenobiotic metabolism and calculate the toxicity of their metabolites. | [104] |

| BioTransformer | Knowledge-based system with random forest | Phases I + II, human gut microbial metabolism, promiscuous enzymatic metabolism, and promiscuous enzymatic metabolism | Provides predictions of small molecule metabolism in mammals and environmental microorganisms, while also assisting in metabolite identification through the analysis of experimental MS data. Biotransformer offers a broad predictive spectrum across various metabolic processes. It consists of BMPT, which combines expert rules from MetXBioDB and SMARTS/SMIRKS encoded rules with the CYPreact ML model, and BMIT, which identifies metabolites from MS data. This tool can predict phases I and II metabolism, as well as microbial and environmental metabolism. | [74] |

| GLORY | Knowledge-based system with RF | Phase I | An aggregated collection of literature-derived CYP-mediated reaction rules and prediction for SOMs. | [105] |

| GLORYx | Knowledge-based system with RF | Phases I + II | Improves a GSH conjugation rule that enhances phase II metabolic reactions, thus enabling very comprehensive predictions of metabolism. GLORYx enhances CYP-mediated phase I and phase II metabolite prediction by integrating ML with reaction rule sets. Using FAME3 for metabolic site prediction and SMIRKS-based rules (from GLORY, SyGMa, and GSH conjugation), it provides a comprehensive prediction of metabolite reactions and scores them to prioritize outcomes. | [106] |

| Metabolic Forest | Knowledge-based system with an algorithm codenamed metabolic forest | Phase I | Developed a metabolite structure predictor that efficiently generates and enumerates trees of metabolic pathways. | [107] |

| CyProduct | ML algorithm of CypReact [96] | CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 | Redefined a concept to describe where chemical reactions take place: BoM and build a dataset for prediction based on BoM. CyProduct uses expert rules and ML to predict CYP-mediated metabolites. It introduces the BoM concept to define reaction sites. Using the CypReact63 model, CypBoM classifier, and MetaboGen rules, it effectively predicts metabolite structures with high accuracy. | [108] |

| MetaTrans | Deep transfer learning | Phases I + II | MetaTrans employs a neural machine translation model for predicting drug metabolite structures. Pre-trained on chemical reactions and fine-tuned with human metabolic data, it uses an ensemble model and beam search algorithm to predict enzyme-mediated metabolites. Despite its broad predictive capability, it struggles with identifying negative metabolites and some reaction types due to dataset limitations. | [109] |

| Wang et al. [110] | DL | Phases I + II | Match metabolic data with an established database of metabolic reaction templates to generate potential metabolites, and use DL models to classify compounds and predict metabolites. Wang et al. [110] developed a DL method for drug metabolite prediction. It involves matching compounds to a library of reaction templates, filtering for practical structures, and using neural networks to generate and validate potential metabolites. This approach reduces false positives and broadens the range of predicted reactions. | [110] |

| MetNC | Knowledge-based system with a ranking algorithm | NCs | Using reaction simulation and candidate sorting to predict in vivo metabolites, offering an extra advantage in microbiota-mediated metabolism. | [111] |

TIMES: tissue metabolism simulator; MDL: Drug Data Report; SMIRKS: simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) reaction specification; UM-PSS: University of Minnesota Pathway Prediction System; PASS: prediction of activity spectra for substances; CYP: cytochrome P450s family enzymes; UDP: uridine diphosphate; MS: mass spectrometry; BMPT: BioTransformer’s metabolism prediction tool; SMARTS: SMILES arbitrary target specification; BMIT: BioTransformer’s Metabolite Identification Tool; GLORY: Generator of the Structures of Likely Cytochrome P450 Metabolites Based on Predicted Sites of Metabolism; RF: random forest; SOMs: sites of metabolism; GSH: glutathione; ML: machine learning; FAME3: FAst MEtabolizer 3; BoM: bond of metabolism; DL: deep learning; NCs: natural compounds.

4.1. Databases related to human metabolism

The selection of appropriate databases is critical for accurate metabolism prediction, as these resources provide foundational data on substrates, enzymes, metabolites, and pathways. Whether at the molecular or omics level, predictive models are rarely built using standardized databases. Most model builders curate their own unique datasets. These datasets may be derived from open-access databases, extended with proprietary data, or rely entirely on commercial databases. Current metabolism-related databases vary in scope, ranging from molecular-level drug metabolism to multi-omics integration.

Databases such as DrugBank [71] and SuperCYP [72] prioritize drug-enzyme interactions, offering substrate-product pairs, reaction types, and enzyme specificity. These resources are indispensable for predicting phase I/II metabolism and drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Commercial platforms like MDL Drug Data Report (MDDR) [77] and Integrity [76] further enhance drug discovery pipelines by integrating chemical structures, bioactivity data, and patent information. Open-source tools (e.g., XMetDB [37] and MetXBioDB [74]) democratize access to xenobiotic metabolism data, enabling community-driven model development. To contextualize metabolism within broader biological systems, databases like Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) [67] and MetaCyc [68] catalog endogenous metabolites, pathways, and enzyme-gene associations. MetaCyc uniquely bridges human metabolism with microbial and disease-associated pathways, while Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) [69] enables GEM construction by mapping biochemical reactions to genomic data. Cancer-specific resources such as Cancer Atlas of Metabolic Profiles (CAMP) [75] reveal metabolic dysregulation through paired gene-metabolite covariation analysis, offering insights into oncogenic rewiring. Despite advances, critical gaps persist. Proprietary databases (e.g., MDDR [77]) limit service restrictions, while public resources often lack standardized annotations or tissue-specific classification.

This section emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate metabolism-related databases for accurate predictions in different models, highlighting their diverse applications. And obviously, the challenge of data standardization and integration remains a key issue in this field.

4.2. Ligand based models for predicting metabolism at the molecular level

The summaries of the ligand-based descriptors are in Fig. 2A. Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of chemical structures (e.g., atomic composition and bond connectivity), which are either quantitative (e.g., molecular graph theory and spectral data) or qualitative (e.g., fingerprints). Descriptors can be in various formats, such as Boolean, integer, or vector, and differ in dimensionality (one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), or three-dimensional (3D). Selecting appropriate descriptors for ML methods is crucial and challenging in QSAR modeling. Quantization and reactivity-based descriptors are commonly used in drug metabolism at the molecular level. For instance, quantum chemistry descriptors are utilized in RegioSelectivity-Predictor (RS-Predictor) [94], while SMARTCyp [93] employs specific rules to build a density functional theory (DFT) activation energy database for ligand fragments. SMARTCyp, developed by Rydberg et al. [93] in 2010, predicts SOMs using QSAR and DFT activation energy data. Molecular fingerprints are used by Metaprint2D [91] and Reaction Database (RD)-Metabolizer [92] for defining and calculating reaction center similarities. Extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) [112] are widely applied in ML and DL approaches for feature representation [113].

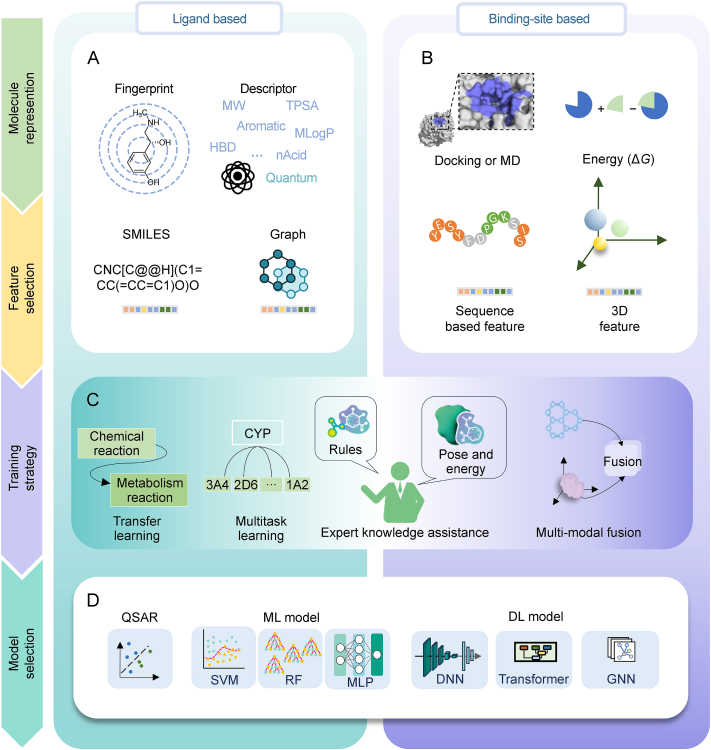

Fig. 2.

The key points of artificial intelligence (AI)-based metabolism predicting models at the molecular level, including both the ligand based and binding-site based methods. (A) The ligand based features. (B) The binding-site based features. (C) The training strategies. (D) The models used for prediction. MW: molecular weight; TPSA: topological polar surface area; HBD: hydrogen bond donor; MLogP: molecular logarithm of partition coefficient; nAcid: number of acidic groups; SMILES: simplified molecular input line entry system; MD: molecular dynamics; 3D: three-dimensional; CYP: cytochrome P450s family enzymes; QSAR: quantitative structure-activity relationship; ML: machine learning; SVM: support vector machine; RF: random forest; MLP: multilayer perceptron; DL: deep learning; DNN: deep neural network; GNN: graph neural network.

DL techniques, known for their ability to automatically extract features and model complex non-linear relationships [114], can enhance predictive accuracy in metabolic modeling. These methods utilize various molecular inputs, including graphs and simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES), to learn directly from molecular structures. SMILES, introduced by Weininger in 1986 and further developed by Daylight Chemical Information Systems Inc., is a string-based linear notation widely used for representing compound structures in a concise format [115]. The representative method is MetaTrans [109]. Researchers of MetaTrans considered the metabolite prediction problem as a sequence translation problem, not a rule-screening problem. This method is based on the molecular SMILES representation, and the model undergoes transfer learning using a pre-trained Transformer.

Graph neural networks (GNNs) [18] have emerged as a powerful framework for modeling molecular structures, leveraging the inherent graph-based representation of molecules. In this context, atoms are represented as nodes, while chemical bonds are depicted as edges, forming a molecular graph. This representation naturally captures the topological and structural information of molecules, making GNNs particularly effective in feature extraction for molecular property prediction and drug discovery tasks. GNNs operate by iteratively aggregating information from neighboring nodes and edges, enabling the model to capture both local and global structural patterns. For instance, in a graph convolutional network (GCN), the feature representation of a node is updated by aggregating features from its immediate neighbors, followed by a non-linear transformation. Porokhin et al. [116] used convolution operators of three different graph networks to predict SOM, which demonstrated its advantage over traditional algorithms. We can observe the effectiveness of the integration ability of GNN in the global information of molecules for understanding chemical reactivity. In addition, the attention mechanism is particularly effective in capturing the relationships between atoms within a molecule. Ai et al. [117] utilized attention-based graph networks combined with molecular fingerprints to predict CYP substrates, yielding improved results. Additionally, GCNs that incorporate attention mechanisms have also been employed to predict CYP substrates [118].

In data-limited scenarios, traditional ML models often outperform complex models [119]. Huang et al. [120] found that a fingerprint-based ML model outperformed GCN and transformer models for predicting SOM of AOXs, highlighting the effectiveness of simpler models with limited data.

Multitask learning represents a valuable strategy for classifying CYP inhibitors and substrates. This approach has demonstrated efficacy across diverse input features, including molecular descriptors [121] and hybrid representations combining molecular fingerprints with graph networks [117]. Furthermore, graph-based multitask pretraining has been integrated into widely established web tools for classification tasks of CYP inhibitors or substrates, such as ADMETlab [81] and admetSAR [83].

Currently, combining expert systems with ML is the dominant approach for predicting metabolites. Expert systems use rule-based knowledge, derived from empirical data and literature, to predict metabolite formation. The rules are compiled using SMILES arbitrary target specification SMARTS) [122] or SMILES reaktion specification (SMIRKS) [123]. SMARTS, an extension of SMILES, incorporates wildcards for atoms and bonds, facilitating computerized searches in compound databases. SMIRKS, a reaction transformation language, describes reaction mechanisms with varying specificity. SyGMa's [102] initial rules, using SMIRKS and SMARTS, have been expanded by GLORY [105] and GLORYx [106]. Wang et al.'s [110] approach broadens reaction types through template extraction. BioTransformer [74] now offers the most comprehensive set of metabolic rules, integrating constraint conditions and enzyme links. These systems iteratively apply reaction rules to a drug molecule until a predefined condition, such as the generation of a phase II metabolite, is met. The goals of expert systems include generating plausible phase I and II metabolites, modeling metabolic profiles, identifying reactive sites, and assessing metabolite formation under various conditions. ML models predict substrate specificity or SOMs, which are then refined by expert systems to generate accurate metabolite structures. This integration helps reduce false positives and enhances prediction accuracy while maintaining interpretability [74,106].

In conclusion, we outline the application of traditional ML and DL in modeling ligand-based metabolism prediction at the molecular level, emphasizing their roles in feature representation, and modeling of complex reaction processes. Furthermore, we highlight the synergistic integration of expert systems with ML techniques, which enhances metabolite prediction accuracy while maintaining interpretability, ultimately advancing the field of computational drug discovery and metabolism.

4.3. Binding site-based models for predicting metabolism at the molecular level

The summaries of the binding site-based descriptors are presented in Fig. 2B. Previous studies have employed enzyme docking with small molecular substrates and MD simulations to identify SOMs. The flexibility of residues at binding sites, as well as the regional and stereoselectivity of compounds often necessitates structure-based simulation. MD simulations may provide more accurate representations due to the common occurrence of ligand-induced conformational changes in enzymes [85]. This topic has been discussed extensively in previous reviews [18,[124], [125], [126]]. Furthermore, the binding affinity between reactants and enzymes can be predicted through drug-target interactions (DTI) [127], allowing for the extraction of descriptors related to the binding process. Additionally, several methods exist to integrate molecular simulation results with ML techniques [[86], [87], [88]]. For instance, Martiny et al. [85] utilized ECFP and the predicted binding energies derived from both X-ray crystal structures and MD trajectories to predict the inhibitors of CYP2D6.

When computing resources are limited, molecular docking and kinetic simulation, which are resource-intensive and time-consuming methods for predicting metabolic enzyme substrates, are often set aside. However, with advancements in computing power and hardware, an increasing number of methods are focusing on the learning of protein structure [128,129]. For instance, Qiu et al. [118] projected the pseudo-sequences of the reflection sites into the feature space using convolutional techniques and subsequently combined these with ligand features for substrate prediction.

In conclusion, we summarize the application of binding site-based descriptors, focusing on the integration of MD simulations and enzyme docking to identify SOMs and predict binding affinities via DTI. Additionally, we highlight the transition towards ML methods for analyzing protein structures, which reflects the evolution of predictive modeling in drug metabolism and underscores the potential for improved accuracy and efficiency in substrate prediction through advanced computational techniques.

Despite the distinct molecular representations utilized by ligand-based and binding-site-based methods, different training strategies can be employed based on the specific task. Ligand-based approaches often incorporate transfer learning and multitask learning methodologies. In contrast, binding-site-based methods must focus on effectively fusing the disparate representations of both the receptor and ligand. Additionally, the incorporation of expert knowledge is crucial in model development, which includes establishing reaction rules, simulating binding poses, and conducting energy calculations (Fig. 2C). When constructing models, a variety of foundational models can be utilized, ranging from QSAR to traditional ML models, and extending to DL architectures, with applications in both categories (Fig. 2D).

4.4. GEM and metabolic flux predicting models

In the study of endogenous metabolism, the focus is primarily on energy homeostasis and anabolic processes, while xenobiotic metabolism emphasizes detoxification and excretion [130,131]. This divergence is reflected in the kinetic parameters of metabolic pathways: endogenous pathways typically operate near steady-state flux, as seen in glycolysis, whereas xenobiotic reactions exhibit variable kinetics [130]. The integration of both endogenous and xenobiotic metabolism has been significantly advanced through GEMs, which include foundational datasets that encompass both types of metabolism (Table 5) [25,[28], [29], [30], [31],[132], [133], [134]]. Recon 1 [28] laid the foundation, while Recon 2 expanded it through community-driven efforts [30], integrating additional reactions and metabolites. Recon 2.2 [31] refined this by ensuring mass and charge balance, improving ATP production predictions. Recon 3D [29] introduced 3D structural information, enhancing its utility in structural biology and mechanistic insights into drug response, and bridged endogenous and xenobiotic metabolism by incorporating tissue-specific enzyme expression data. It provides support for guiding the discovery of novel biomarkers and drug targets. Edinburgh Human Metabolic Network (EHMN) [132] focused on subcellular localization, particularly in lipid metabolism. HepatoNet1 [133] represents a liver-specific model, capturing hepatocyte functions like ammonia detoxification. HMR 2.0 [134] integrated multi-omics data to generate tissue-specific networks. Human1 [25] provided a precise framework for systems biology and disease research. These models, varying in scope and specificity, collectively advance our understanding of human metabolism through multi-omics integration, enabling insights into normal and disease states.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of human metabolic network reconstruction models: statistical insights into genes, reactions, and metabolites.

| Model | Description | Statistics |

Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | Metabolic reactions | Metabolites | |||

| Recon 1 | The first global human metabolic network reconstruction based on genomic and literature data. | 1,496 | 3,744 | 2,766 | [28] |

| Recon 2 | An expanded version of Recon 1, a community-driven consensus reconstruction with more reactions and metabolites. | 1,789 | 7,440 | 5,063 | [30] |

| Recon 2.2 | A further updated version of Recon 2 which improves the accuracy and integrity of the model, especially in terms of energy metabolism and reaction balance. | 1,675 | 7,785 | 5,324 | [31] |

| Recon 3D | An extended version of Recon 2, integrating 3D structures of proteins and metabolites. | 1,654 | 13,543 | 4,140 | [29] |

| EHMN | A global human metabolic reconstruction model. | / | 4,804 | / | [132] |

| HepatoNet1 | A comprehensive metabolic reconstruction model of human hepatocytes. | / | 2,539 | 777 | [133] |

| HMR 2.0 | Including more reactions and metabolites. | / | 2,250 | 74,286 | [134] |

| Human1 | A human metabolic atlas containing metabolic models of multiple tissues and cell types. | 3,625 | 13,417 | 10,138 | [25] |

3D: three-dimensional; EHMN: Edinburgh Human Metabolic Network; HMR: Human Metabolic Reconstruction.

One of the most commonly used analytical methods in GEMs is FBA, a well-established constraint optimization method for estimating the flow of metabolites in complex biological systems [32]. It maximizes or minimizes the flux of a particular reaction or linear combination of reactions under the steady-state assumption and flux boundary constraints. In order to apply FBA to gene expression data, researchers must systematically interpret gene expression levels within the context of metabolic networks. A way to incorporate gene expression data into FBA is to use gene expression levels to distinguish between high-expression and low-expression responses, such as Integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool (iMAT) [135]. Another way is to use expression levels to define flux boundaries in FBA, such as a method which is combined of flux and expression (E-Flux) [136]. Huang et al. [13] proposed a computational framework, Metabolic Flux Balance Analysis (METAFlux), to infer metabolic flux from large or single-cell transcriptome data. Gene Expression-based Metabolite Centrality Analysis Tool (GEMCAT) [137] is a novel approach that integrates PageRank algorithms with transcriptomic and proteomic data to predict metabolic changes in human GEMs, offering insights into the molecular mechanisms of diseases and informing the development of new drugs.

The development of GEMs represents a significant advancement in metabolic modeling technology, enabling comprehensive metabolic flux and concentration analyses, enhancing our understanding of metabolic networks, and opening up new possibilities for biomedical research and clinical applications, particularly in identifying drug targets and biomarkers, as well as guiding drug development [25,29,130].

5. Future perspective

While computational and AI methods have advanced metabolic prediction, significant challenges remain in addressing the multifactorial complexity of human metabolism. First, data heterogeneity poses a major hurdle, as integrating diverse datasets (e.g., multi-omics, clinical variables, and demographic factors) requires robust normalization strategies to mitigate batch effects and biological variability. ML models often struggle with imbalanced or sparse data, particularly in underrepresented populations (e.g., pregnant individuals or elderly cohorts) [60,61,66]. Second, making data in public databases available in an open format is a crucial step for the development of more effective models and facilitates comparisons across various approaches [37].

For prediction at the molecular level, challenges include evaluating enzyme catalysis on unnatural substrates and defining reactive components of molecules. Despite improvements in computational power that enhance simulation accuracy, AI algorithms still rely on large, high-quality datasets to improve predictive accuracy and minimize false positives. Transparency in ML models remains a significant concern, impacting the trustworthiness and generalizability of results. Future predictive models should prioritize clarity and integration, with a stronger emphasis on enzyme selectivity. One potential strategy to improve model robustness and accuracy is to extract features from the 3D structures of enzymes, particularly information pertaining to reaction sites. This approach is expected to yield more reliable predictions of enzyme-substrate interactions. With the ongoing development of 3D structural feature extraction algorithms, incorporating 3D structural features into metabolic predictive models is expected to yield considerable advantages. Additionally, considering the flexibility of enzyme binding pockets is essential, as binding sites can vary in shape and dynamics. MD simulations offer a valuable tool for assessing enzyme binding to small molecules over time. However, the computational expense of MD simulations has limited their widespread application. Recent advancements in DL have made it possible to predict protein structures and enzyme-ligand interactions more efficiently. For instance, AI2BMD [138] is an AI-based ab initio biomolecular dynamics system that enables efficient full-atom protein simulations, significantly reducing computation time compared to DFT. A neural network model based on the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF-net) [139] predicts the local structural flexibility of proteins by combining cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) density characteristics. Although these methods may not be proved to be completely convincing, they open up new opportunities for predicting substrates or inhibitors for specific enzymes. Finally, model interpretability remains a critical limitation [140]. AI models trained on biased datasets may perpetuate disparities in metabolic risk prediction across genders or ethnic groups, while clinical adoption is hindered by the "black-box" nature of many algorithms [141].

Despite advances in omics-based prediction, significant challenges persist. Traditional GEMs, such as Recon3D, face limitations in capturing dynamic physiological states (e.g., circadian rhythms and pregnancy-induced metabolic shifts) due to their reliance on steady-state assumptions [142]. Furthermore, imbalanced and sparse datasets, particularly from underrepresented populations, pose substantial modeling challenges [63,64,69]. Recent developments have focused on multi-modal approaches that integrate GEMs with clinical data. These integrated frameworks enhance AI's capacity to analyze disease-specific metabolism, supporting clinical diagnosis and drug evaluation [143]. Notably, both molecular-level predictive models and GEMs share core metabolic reaction datasets. This common foundation suggests that incorporating drug response data into multi-modal models could enable a more accurate assessment of exogenous substance effects on disease-specific metabolism. Such integration represents a promising direction for advancing personalized medicine. Addressing these challenges requires collaborative efforts to develop adaptive, explainable frameworks that effectively integrate multi-scale data while reflecting metabolic diversity.

6. Conclusion

In general, despite advancements in computational and AI-driven methods, metabolic prediction still faces challenges such as data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and the complexities of dynamic physiological states. Progress depends on developing integrated, explainable frameworks that effectively address biological diversity while overcoming computational constraints.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Manzhan Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Yuxin Wan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Jing Wang: Data Curation. Shiliang Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Honglin Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.: 82425104 and 82173690), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos: 2022YFC3400501 and 2022YFC3400504), and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program, China (Grant No: 23QA1402800).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Contributor Information

Shiliang Li, Email: slli@hsc.ecnu.edu.cn.

Honglin Li, Email: hlli@hsc.ecnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Liu H., Wang S., Wang J., et al. Energy metabolism in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025;10:69. doi: 10.1038/s41392-025-02141-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rekka E.A., Kourounakis P.N., Pantelidou M. Xenobiotic metabolising enzymes: impact on pathologic conditions, drug interactions and drug design. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019;19:276–291. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190129122727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson J.K., Wilson I.D. Understanding ‘global’ systems biology: metabonomics and the continuum of metabolism. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:668–676. doi: 10.1038/nrd1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingelman-Sundberg M. Polymorphism of cytochrome P450 and xenobiotic toxicity. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:447–452. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J., Zhao K., Chen C. The role of CYP3A4 in the biotransformation of bile acids and therapeutic implication for cholestasis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014;2:7. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2013.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baj J., Flieger W., Przygodzka D., et al. Application of HPLC-QQQ-MS/MS and new RP-HPLC-DAD system utilizing the chaotropic effect for determination of nicotine and its major metabolites cotinine, and trans-3’-hydroxycotinine in human plasma samples. Molecules. 2022;27:682. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu L., Tian Y., Ling J., et al. Effects of storage temperature on indica-Japonica hybrid rice metabolites, analyzed using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:7421. doi: 10.3390/ijms23137421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zenobi R. Single-cell metabolomics: Analytical and biological perspectives. Science. 2013;342 doi: 10.1126/science.1243259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang C., Chen L., Rabinowitz J.D. Metabolomics and isotope tracing. Cell. 2018;173:822–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBerardinis R.J., Keshari K.R. Metabolic analysis as a driver for discovery, diagnosis, and therapy. Cell. 2022;185:2678–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang H., Hu Z. Metabolomics in drug research and development: The recent advances in technologies and applications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2023;13:3238–3251. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuhknecht L., Ortmayr K., Jänes J., et al. A human metabolic map of pharmacological perturbations reveals drug modes of action. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025 doi: 10.1038/s41587-024-02524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y., Mohanty V., Dede M., et al. Characterizing cancer metabolism from bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data using METAFlux. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:4883. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40457-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchmair J., Göller A.H., Lang D., et al. Predicting drug metabolism: Experiment and/or computation? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:387–404. doi: 10.1038/nrd4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav J., El Hassani M., Sodhi J., et al. Recent developments in in vitro and in vivo models for improved translation of preclinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics data. Drug Metab. Rev. 2021;53:207–233. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2021.1922435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Free S.M., Wilson J.W. A mathematical contribution to structure-activity studies. J. Med. Chem. 1964;7:395–399. doi: 10.1021/jm00334a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller D.D., Brown E.W. Artificial intelligence in medical practice: The question to the answer? Am. J. Med. 2018;131:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudas B., Miteva M.A. Computational and artificial intelligence-based approaches for drug metabolism and transport prediction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024;45:39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2023.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson C.H., Ivanisevic J., Siuzdak G. Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:451–459. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zampieri M., Sauer U. Metabolomics-driven understanding of genotype-phenotype relations in model organisms. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2017;6:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yugi K., Kuroda S. Metabolism as a signal generator across trans-omic networks at distinct time scales. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2018;8:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christofk H., Metallo C., Liu G., et al. Metabolic heterogeneity in humans. Cell. 2024;187:3821–3823. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zampieri G., Vijayakumar S., Yaneske E., et al. Machine and deep learning meet genome-scale metabolic modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goh W.W.B., Wang W., Wong L. Why batch effects matter in omics data, and how to avoid them. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson J.L., Kocabaş P., Wang H., et al. An atlas of human metabolism. Sci. Signal. 2020;13 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaz1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien E.J., Monk J.M., Palsson B.O. Using genome-scale models to predict biological capabilities. Cell. 2015;161:971–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pornputtapong N., Nookaew I., Nielsen J. Human metabolic atlas: An online resource for human metabolism. Database (Oxford) 2015;2015 doi: 10.1093/database/bav068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duarte N.C., Becker S.A., Jamshidi N., et al. Global reconstruction of the human metabolic network based on genomic and bibliomic data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1777–1782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunk E., Sahoo S., Zielinski D.C., et al. Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:272–281. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiele I., Swainston N., Fleming R.M.T., et al. A community-driven global reconstruction of human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:419–425. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swainston N., Smallbone K., Hefzi H., et al. Recon 2.2: From reconstruction to model of human metabolism. Metabolomics. 2016;12:109. doi: 10.1007/s11306-016-1051-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orth J.D., Thiele I., Palsson B.Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeBerardinis R.J., Thompson C.B. Cellular metabolism and disease: What do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell. 2012;148:1132–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghesquière B., Wong B.W., Kuchnio A., et al. Metabolism of stromal and immune cells in health and disease. Nature. 2014;511:167–176. doi: 10.1038/nature13312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanton C., Bernard E., Abbosh C., et al. Embracing cancer complexity: Hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell. 2024;187:1589–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arner E.N., Rathmell J.C. Metabolic programming and immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spjuth O., Rydberg P., Willighagen E.L., et al. XMetDB: An open access database for xenobiotic metabolism. J. Cheminf. 2016;8:47. doi: 10.1186/s13321-016-0161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Testa B., Pedretti A., Vistoli G. Reactions and enzymes in the metabolism of drugs and other xenobiotics. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isin E.M., Guengerich F.P. Substrate binding to cytochromes P450. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:1019–1030. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebler D.C., Guengerich F.P. Elucidating mechanisms of drug-induced toxicity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:410–420. doi: 10.1038/nrd1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vašková J., Kočan L., Vaško L., et al. Glutathione-related enzymes and proteins: A review. Molecules. 2023;28:1447. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krautkramer K.A., Fan J., Bäckhed F. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:77–94. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sonnenburg J.L., Bäckhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nature18846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma A.K., Jaiswal S.K., Chaudhary N., et al. A novel approach for the prediction of species-specific biotransformation of xenobiotic/drug molecules by the human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9751. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guthrie L., Wolfson S., Kelly L. The human gut chemical landscape predicts microbe-mediated biotransformation of foods and drugs. eLife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.42866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J., Wang K., Wang X., et al. The role of the gut microbiome and its metabolites in metabolic diseases. Protein Cell. 2021;12:360–373. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao C.K., Muir J.G., Gibson P.R. Review article: Insights into colonic protein fermentation, its modulation and potential health implications. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;43:181–196. doi: 10.1111/apt.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliphant K., Allen-Vercoe E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: Major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome. 2019;7:91. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0704-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen D.D., Kunze K.L., Thummel K.E. Enzyme-catalyzed processes of first-pass hepatic and intestinal drug extraction. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997;27:99–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leinweber F.J. Possible physiological roles of carboxylic ester hydrolases. Drug Metab. Rev. 1987;18:379–439. doi: 10.3109/03602538708994129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sattler M., Guengerich F.P., Yun C.H., et al. Cytochrome P-450 3A enzymes are responsible for biotransformation of FK506 and rapamycin in man and rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1992;20:753–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antoniewicz M.R. A guide to metabolic flux analysis in metabolic engineering: Methods, tools and applications. Metab. Eng. 2021;63:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dang L., White D.W., Gross S., et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C., Liu Y., Lu C., et al. Cancer-associated IDH2 mutants drive an acute myeloid leukemia that is susceptible to Brd4 inhibition. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1974–1985. doi: 10.1101/gad.226613.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su R., Dong L., Li Y., et al. Targeting FTO suppresses cancer stem cell maintenance and immune evasion. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:79–96.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elia I., Haigis M.C. Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: From cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2021;3:21–32. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00317-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu G., Zhou X. Gender difference in the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of VX-548 in rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2024;45:107–114. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biol. Sex Differ. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in energy metabolism: Natural selection, mechanisms and consequences. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024;20:56–69. doi: 10.1038/s41581-023-00781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cartee G.D., Hepple R.T., Bamman M.M., et al. Exercise promotes healthy aging of skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1034–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zamboni N., Saghatelian A., Patti G.J. Defining the metabolome: Size, flux, and regulation. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sato S., Solanas G., Peixoto F.O., et al. Circadian reprogramming in the liver identifies metabolic pathways of aging. Cell. 2017;170:664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.042. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu J., Bu D., Wang H., et al. The rhythmic coupling of Egr-1 and Cidea regulates age-related metabolic dysfunction in the liver of male mice. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:1634. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36775-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Froy O. Cytochrome P450 and the biological clock in mammals. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009;10:104–115. doi: 10.2174/138920009787522179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Asher G., Schibler U. Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell Metab. 2011;13:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu D.N., Wan H.F., Tong C., et al. A multi-tissue metabolome atlas of primate pregnancy. Cell. 2024;187:764–781.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wishart D.S., Guo A., Oler E., et al. HMDB 5.0: The Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D622–D631. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caspi R., Billington R., Fulcher C.A., et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D633–D639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noronha A., Modamio J., Jarosz Y., et al. The Virtual Metabolic Human database: integrating human and gut microbiome metabolism with nutrition and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D614–D624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Sato Y., et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D587–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C., et al. DrugBank 5.0: A major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Preissner S., Kroll K., Dunkel M., et al. SuperCYP: A comprehensive database on Cytochrome P450 enzymes including a tool for analysis of CYP-drug interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D237–D243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mak L., Marcus D., Howlett A., et al. Metrabase: A cheminformatics and bioinformatics database for small molecule transporter data analysis and (Q)SAR modeling. J. Cheminf. 2015;7:31. doi: 10.1186/s13321-015-0083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Djoumbou-Feunang Y., Fiamoncini J., Gil-de-la-Fuente A., et al. BioTransformer: A comprehensive computational tool for small molecule metabolism prediction and metabolite identification. J. Cheminf. 2019;11:2. doi: 10.1186/s13321-018-0324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Benedetti E., Liu E.M., Tang C., et al. A multimodal atlas of tumour metabolism reveals the architecture of gene-metabolite covariation. Nat. Metab. 2023;5:1029–1044. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cortellis, Drug Discovery Intelligence. https://integrity.clarivate.com/. (Accessed 14 May 2025).

- 77.Zhang M., Sheng C.Q., Xu H., et al. Constructing virtual combinatorial fragment libraries based upon MDL Drug Data Report database. Sci. China, Ser. B Chem. 2007;50:364–371. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan H.C.S., Shan H., Dahoun T., et al. Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019;40:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schneider P., Walters W.P., Plowright A.T., et al. Rethinking drug design in the artificial intelligence era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:353–364. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tran T.T.V., Tayara H., Chong K.T. Artificial intelligence in drug metabolism and excretion prediction: Recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:1260. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiong G., Wu Z., Yi J., et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W5–W14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Banerjee P., Dunkel M., Kemmler E., et al. SuperCYPsPred − a web server for the prediction of cytochrome activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W580–W585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gu Y., Yu Z., Wang Y., et al. admetSAR3.0: A comprehensive platform for exploration, prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52:W432–W438. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pires D.E.V., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martiny V.Y., Carbonell P., Chevillard F., et al. Integrated structure- and ligand-based in silico approach to predict inhibition of cytochrome P450 2D6. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3930–3937. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rakers C., Schumacher F., Meinl W., et al. In silico prediction of human sulfotransferase 1E1 activity guided by pharmacophores from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:58–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.685610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dudas B., Bagdad Y., Picard M., et al. Machine learning and structure-based modeling for the prediction of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition. iScience. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martiny V.Y., Carbonell P., Lagorce D., et al. In silico mechanistic profiling to probe small molecule binding to sulfotransferases. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cruciani G., Carosati E., De Boeck B., et al. MetaSite: Understanding metabolism in human cytochromes from the perspective of the chemist. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6970–6979. doi: 10.1021/jm050529c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]