SUMMARY

Copper-mediated radiolabelling has transformed how (hetero)aromatic imaging agents are prepared for positron emission tomography (PET). However, current methods maintain critical stability, reactivity, and toxicity concerns paramount for safely and reproducibly generating radiomedicines. To overcome these limitations, a copper-mediated 11C-cyanation reaction is presented that leverages heptamethyltrisiloxanes as (hetero)aryl nucleophiles. Rapid ipso-radiocyanation occurs in conversions surpassing related precursors, while offering stability and safety advantages. Multiple bioactive scaffolds relevant to (pre)clinical PET were labelled to showcase the broader significance of this protocol. Most notably, an automated radiosynthesis of a κ-opioid receptor antagonist currently used in clinical PET studies is reported using this method. Overall, adopting aryl silane precursors will improve radiochemical space and support the production of PET nuclear medicines.

Keywords: Radiocyanation, Radiochemistry, Carbon-11, Copper-Mediated Radiolabelling, Positron Emission Tomography, Nuclear Medicine, Organosilane

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans provide clinicians and imaging scientists with dynamic patient images that depict the biochemical uptake, distribution, metabolism, and clearance of chemical entities radiolabelled with β+-emitting radioisotopes.1,2 In a healthcare setting, providers routinely employ PET to study, stage, and support disease diagnosis, facilitating precision medicine-guided patient treatments.3 In drug discovery, PET is used to evaluate therapeutic targets in human clinical trials, enabling the delineation and stratification of patient populations by assessing the eligibility of individual participants. Many developments in these spaces have led to a surge in demand for new radiolabelling protocols that efficiently deliver (pre)clinical PET agents.4 Of the many radiolabelled chemical entities available for PET, carbon-11-containing small organic molecules are routinely employed owing to (a) the chemical ubiquity of carbon (b) widespread availability of small medical cyclotrons capable of inducing the 14N(p,α)11C nuclear reaction (c) low effective patient radiation exposures due to a relatively short half-life (t1/2 = 20.4 min) and low positron energy (0.96 MeV).5

Key requirements for carbon-11 radiolabelling reactions include high radioisotope incorporation, short reaction time (<10 min), reproducible automation on a commercial synthesis module, and high molar activity (Am) using limiting radioisotope. Existing methods that meet these criteria primarily rely on established addition and substitution strategies that engage [11C]CO2, [11C]CH3I, or [11C]CH3OTf, amongst other labelled derivatives.6–9 Though functional and efficient, these protocols cannot be used to label many sites of interest in organic molecules, which impedes the design of PET imaging agents with optimal pharmacokinetic parameters. Pd-mediated radiocyanation is a well-established alternative, although metal toxicity complicates routine clinical translation.10–12 Over the past decade, copper-mediated radiolabelling has emerged as a versatile platform for constructing robust aromatic C–11C linkages. Cu-mediated reactions have proven particularly effective for accessing radiolabelled electron-rich arenes13–15 and have been widely adopted, owing to operational simplicity, efficiency, and the low toxicity of Cu.11

Our team and Liang/Vasdev have reported Cu-mediated nucleophilic radiocyanation reactions that proceed via transmetallation of organoboron and organotin compounds under a polar CuII/III mechanistic manifold (Fig. 1A). These methodologies furnish structurally diverse carbon-11 benzonitriles, which can be utilised directly or derivatised into labelled benzylic amines, benzamides, benzoates, azoles, phenones, imines, amidines, guanidines, and other compounds.16 However, several classes of organoborons are unsuitable for radiolabelling. In particular, (hetero)aromatic boron precursors containing proximal heteroatoms afford poor yields due to competitive protodeborylation side reactions.17,18 While trialkylarylstannane precursors have somewhat improved stabilities, these compounds are often neurotoxic, complicating quality assurance analyses and introducing patient exposure risk.

Figure 1. Aromatic Copper-Mediated (Radio)Cyanation Reactions.

(A) Radiocyanation of Organometallic, Halide, and Cationic Substrates

(B) Non-Radioactive Oxidative Cyanation of C–B and C–H Bonds via Aryl Iodides

(C) Non-Radioactive Oxidative Cyanation of Trialkoxysilanes via Aryl Iodides

(D) Radiocyanation of Aryl Heptamethyltrisiloxanes (This Work)

Toward solving these challenges, our team and others have described radiocyanation protocols using different precursors and mechanistic manifolds.19 For example, aryl halide precursors undergo radiocyanation via an CuI/III oxidative addition pathway, in analogy to the Rosenmund-von Braun reaction.20,21 However, efficient and reproducible conversions hinge on using an air-sensitive CuI catalyst and reaction temperatures up to 130 °C, restricting routine clinical adoption.22 Radiocyanation reactions of aryl diazoniums, thianthreniums, and iodides can be achieved at room temperature with improved air/moisture tolerance via single-electron transfer processes. Still, precursor stability and accessibility, as well as engineering challenges, complicate the clinical adoption of these methods.23,24 Consequently, (pre)clinical arene radiocyanation typically employs the polar CuII/CuIII radiolabelling system with transmetallation-active precursors.

We hypothesised that aryl silanes could address the limitations of existing radiocyanation protocols. These precursors offer the advantages of high bench-top stability (particularly compared to the corresponding boronates), low toxicity (particularly compared to the corresponding stannanes), and facile transmetallation to metals like copper.25,26 Reflecting these advantages, some metal-mediated silane radiolabelling reactions have been reported with electrophilic carbon-11 reagents such as [11C]CO2 and [11C]CO.27 However, nucleophilic radiolabelling of aryl silanes is unknown, reflecting the difficulty of this transformation. Although copper-mediated non-radioactive cyanation reactions of aromatic C–B, C–H, (Fig. 1B) and C–Si bonds (Fig. 1C) have been described by Chang and co-workers, these reactions generate excess cyanide in situ and require high temperatures over prolonged reaction times, obviating radiochemical translation.28,29

This report describes a no-carrier-added, nucleophilic radiocyanation of bench-stable, readily accessible heptamethyltrisiloxanes via rapid fluoride-activated transmetallation to CuII. The reactions proceed with comparable or elevated efficiency compared to analogous reactions with (hetero)aryl boron and stannane precursors. Furthermore, a wide array of electronically diverse substrates are amenable to this transformation, including azole and 2-azaaryl heterocycles, which are notoriously poor substrates for radiolabelling under the CuII/CuIII polar manifold. Several bioactive scaffolds of high relevance in PET imaging have been prepared. Furthermore, an automated radiocyanation has been demonstrated for an κ−opioid receptor antagonist currently used for clinical imaging research across multiple institutions.30 The optimised radiolabelling system readily accesses carbon-11 benzonitriles for PET imaging.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Evaluation of Silicon Motifs

Initial conditions were adapted from copper-mediated radiocyanations of organoboron and organostannane precursors using limiting potassium radiocyanide (ca. nmol) with 100 μmol of silane precursor, 500 μmol Cu(OTf)2, and 1000 μmol NMe4F•4H2O as an activator in 500 μL N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) at 120 °C for 10 min.31–33 Early hits were obtained using widely available trialkoxyaryl silane precursors, such as 1-(OEt)3 and 2-(OMe)3, albeit in low conversions and moderate purities (Scheme 1). We hypothesised that variation of spectator Si substituents could accelerate transmetallation, furnishing [11C]benzonitriles in elevated conversions. A screen of various aryl silane precursors was conducted, and the results of these experiments, including inactive and active silicon motifs, are presented in Scheme 1. Despite preactivation, silanolate, silicate, and silatrane precursors, such as 1-ONaMe2, 1-ST, 1-Pin2, and 1-Cat2, did not afford the desired products. Similarly, acidic precursors that can readily ionise to more nucleophilic analogues, such as 1-BnOHMe2, 1-Ph(OH)2, and 2-OHMe2, did not undergo radiolabelling. Substantially decreasing the electron density at silicon via perfluorination was unsuccessful, likely due to the hydrolytic instability of 1-F3. Compounds containing fewer heteroatomic substituents at silicon, such as 1-Me4OSiPh, 1-OMeMe2, and 3-Me3, also did not afford detectable quantities of labelled products.

Scheme 1. Evaluation of Silicon Motifs for Copper-Mediated Radiocyanation.

(A) Inactive Silicon Motifs with Trace or No Radiochemical Incorporation

(B) Active Silicon Motifs, Including 1-Si(OTMS)2Me Selected for Further Study

RCC = Radiochemical Conversion, Measured via radio-Thin-Layer Chromatography (rTLC). Values Represent the Percentage of Organic Products (Rf>0) vs. Radiocyanide (Rf=0). RCP = Radiochemical Purity. Values Represent the Percentage of Labelled Product vs. Other Organic Labelled Side Products, Measured via radio-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (rHPLC).

Based on these results, silicon motifs with distinct electronic properties were next investigated. Anionic precursors 1-ONaPh2 and 1-F2Ph2, containing multiple aromatic transmetallation-active substituents, underwent radiolabelling in improved radiochemical conversions/purities. 1-(OTMS)3 was also an active precursor, although the low availability and poor synthetic utility of these substrate classes precluded further optimisations. Most promisingly, 1-(OEt)2Me and 1-(OTMS)2Me underwent radiolabelling in moderate to excellent conversions and moderate purities. 1,1,1,3,5,5,5-Heptamethyl-3-aryltrisiloxanes like 1-(OTMS)2Me are bench-stable compounds amenable to standard silica gel chromatography that can be prepared via Pt,34 Ni,35 Rh,36 Ir,37–40 and Ru41–43 C–H functionalisation, Pd and Pt silylation of aryl halides,44 and transetherification45 using inexpensive silicon reagents. Late-stage silylation is possible but not essential since multiple commonly employed transformations tolerate this functional group, including (but not limited to) metallation with hard organometallic reagents, reductive amination, and oxidation.46,47 In contrast, other transmetallation-active radiolabelling precursors (e.g., (hetero)aryl boron and tin analogues) require late-stage installation due to challenges with stability and purification.

Reaction Optimization

Multiple reaction parameters were investigated to optimise the radiochemical conversion (RCC) and radiochemical purity (RCP) of 1-11CN (Table 1, Entry 1). Analysis of the radiolabelling reaction mixture using 1-(OTMS)2Me via rHPLC indicated the formation of a major side-product of comparable polarity to 1-11CN, suggesting a competing radiolabelling pathway. A similar trend was observed for other aryl heptamethyltrisiloxane substrates. Multiple non-radioactive products corresponding to derivatisations of 1-(OTMS)2Me and 1-11CN were analysed via HPLC and excluded, including isocyanobenzenes, benzoyl derivatives, and compounds containing C=N bonds. We hypothesise that a Si–11CN species can form and act as an unproductive reservoir for radiocyanide, preventing the further generation of 1-11CN. This issue was mitigated by adding an extra equivalent of NMe4F•4H2O to decompose these putative compounds, which drastically improved the RCP (Entry 2). Conversions were further enhanced by decreasing the reaction scale to 50 μmol (Entry 3) and 25 μmol (Entry 4), with the additional benefit that lower precursor and reagent loadings ameliorate engineering concerns in clinical radiochemistry. Decreasing the temperature from 120 °C to 80 °C, the reaction time from 10 min to 5 min, and the [Cu]/[F] equivalents to 1/2 had minimal effect on RCC or RCP (Entry 5). However, changing the solvent from DMA to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI), MeCN, or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) inhibited the formation of 1-11CN (Entries 6, 7, 8). Including fluoride and copper in a 2:1 ratio was essential, with other ratios reducing RCCs and RCPs (Entries 13, 14, 15). Cu(OTf)2 outperformed other Cu salts, including CuF2, suggesting that the latter is not formed appreciably under the reaction conditions (Entries 16). Activators used in other aryl silane cross-coupling reactions, such as KOTMS, were inadequate substitutes for NMe4F•4H2O (Entry 17). Finally, by increasing the temperature to 100 °C, efficient conversions were obtained using 10 μmol 1-(OTMS)2Me, and the addition of Et3SiF provided a modest boost to conversion while improving solution homogeneity for improved automation compatibility in DMA or DMF (Entries 18, 19). We speculate that NMe4Et3SiF2 may initially form with improved solubility.

Table 1:

Optimizations in the Copper-Mediated Radiocyanation of 1-(OTMS)2Me

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Entry | 1-[Si] /μmol | [Cu] /μmol | [F] /μmol | Solvent | T /°C | t /min | RCC/% | RCP/% |

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 100 | 500 | 500 | DMA | 120 | 10 | 93 | 48 |

| 2 | 100 | 500 | 1000 | DMA | 120 | 10 | 73 | 85 |

| 3 | 50 | 250 | 500 | DMA | 120 | 10 | 87 | 90 |

| 4 | 25 | 125 | 250 | DMA | 120 | 10 | 79 | 90 |

| 5 | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 75 | 89 |

| 6 | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMI | 80 | 5 | 70 | <5 |

| 7 | 25 | 25 | 50 | MeCN | 80 | 5 | 66 | <5 |

| 8 | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMSO | 80 | 5 | 0 | <5 |

| 9a | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 55 | - |

| 10b | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 88 | <5 |

| 11c | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 72 | <5 |

| 12d | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 80 | 35 |

| 13 | 25 | 25 | 0 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 10 | 0 |

| 14 | 25 | 25 | 75 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 30 | - |

| 15 | 25 | 25 | 250 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 8 | - |

| 16e | 25 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 8 | - |

| 17f | 25 | 25 | 0 | DMA | 80 | 5 | 2 | - |

| 18g | 10 | 25 | 50 | DMA | 100 | 5 | 88 | 84 |

| 19g | 10 | 25 | 50 | DMF | 100 | 5 | 92 | 75 |

See SI for complete details of radiocyanation screening. Radiochemical conversions (RCCs) represent the conversion of radiocyanide (Rf = 0) to organic products measured via radio-thin-layer chromatography. Radiochemical purities (RCPs) verify product identity and represent purities of organic radiolabelled products measured via radio-high-performance liquid chromatography. DMA = N,N-Dimethylacetamide, DMI = 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone, DMSO = Dimethylsulphoxide, DMF = N,N-Dimethylformamide, KOTMS = Potassium trimethylsilanolate.

7.5 equiv. of pyridine added.

7.5 equiv. of imidazo-[1,2-b]pyridazine added.

10 mol% N,N-dimethylpyridin-4-amine was added.

50 μL nBuOH added.

CuF2 was used instead of Cu(OTf)2.

50 μmol KOTMS as an additive.

2 equiv. Et3SiF added.

Reaction Scope

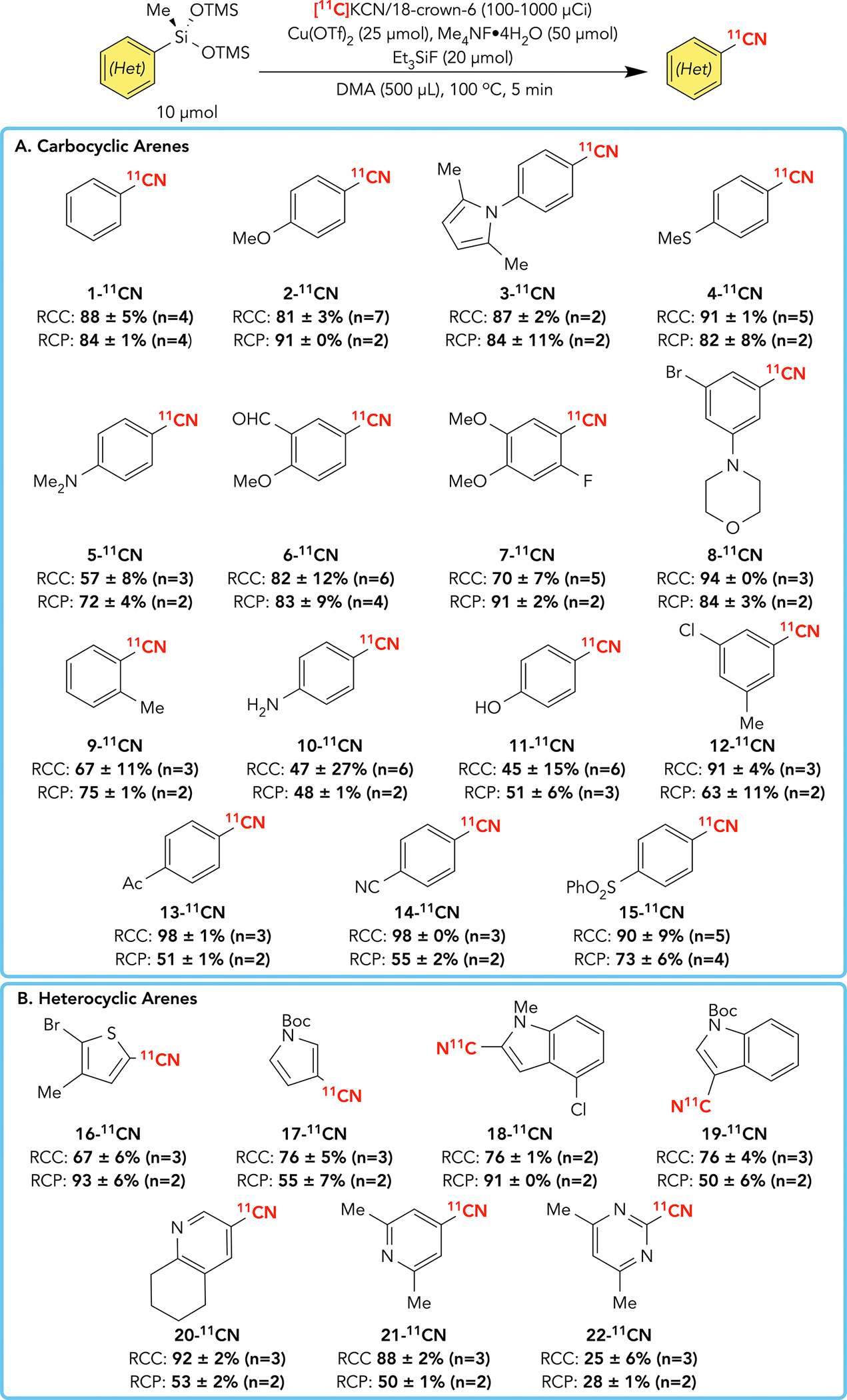

The substrate scope of carbocyclic (Scheme 1A) and heterocyclic (1B) aryl silanes was next investigated using the optimised radiocyanation conditions. Radiobenzonitriles 2-11CN-5-11CN featuring O, N, and S electron-donating substituents, otherwise among the most challenging substrates for aromatic radiolabelling, were formed in good to excellent RCC and RCP. We did not observe aldehyde reduction in 6-11CN, protodemetallation induced by the ortho-fluoro substituent in 7-11CN, or dehalogenation of the bromide in 8-11CN.48 Furthermore, compounds containing chemical moieties that limit radiochemical incorporation in other labelling reactions, such as sterically hindered tolunitrile 9-11CN, unprotected aniline 10-11CN, and unprotected phenol 11-11CN, were obtained in conversions and purities amenable to (pre)clinical development. Although modestly less efficient, radiobenzonitriles containing electron-withdrawing substituents 12-11CN-15-11CN were also obtained in excellent RCCs and good RCPs.

Many heterocyclic scaffolds that are particularly difficult to label were also amenable to radiocyanation using this approach. For example, five-membered heteroarenes, which are notoriously poor radiolabelling substrates, could be functionalised at the α- and β-positions, including 16-11CN-19-11CN. Furthermore, multiple azines 20-11CN-22-11CN were radiolabelled at the α-, β-, and γ-positions, including 2-pyridyl 23-11CN, which was achieved from the corresponding, bench-stable silane precursor 23-(OTMS)2Me isolated via SiO2 gel chromatography (Scheme 3A). Notably, this would be challenging using the related pinacol boronate ester 23-BPin owing to precursor instability. Notably, even attempts to conduct a telescoped borylation/radiocyanation without isolating 23-BPin were unsuccessful (Scheme 3B), highlighting the complementarity and utility of the current approach.49 Finally, bioactive PET imaging scaffolds were efficiently radiolabelled using this method (Scheme 4). Densely functionalised therapeutics featuring native nitriles, including protected pruvanserin 24-11CN and dapivirine 25-11CN, were formed in excellent radiochemical yields and purities. A nitrile precursor analogue 26-11CN to the benzamide PARP inhibitor niraparib was also prepared, noting that analogous molecules are commonly used for oncology PET imaging.50 Next, an automated radiosynthesis of 27-11CONH2, a widely used kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) imaging agent, was performed with manual reformulation on a commercial radiosynthesis module.30,51 The manual radiosynthesis of nitrile precursor 27-11CN was first achieved reproducibly in 80% radiochemical yield (RCY) and >99% RCP from silane precursor 27-(OTMS)2Me, which was stable for >1 year at room temperature, neat and as a DMA solution. In contrast, boronate precursor 27-Bpin (structure not shown) has stability, storability, and preparatory issues that have initiated in-depth studies into alternative preparations of 27-11CONH2.52 Although some reactions concomitantly produced radiolabelled side-products, these compounds were consistently and reliably resolved using standard HPLC purification.

Scheme 3. Radiolabelling of 2-Pyridyl Derivatives.

(A) Successful Radiolabelling of 2-Silylpyridine 23-(OTMS)2Me

(B) Attempted Radiolabelling of 2-Borylpyridine 23-BPin

Reactions conducted under the optimised radiolabelling conditions shown in Scheme 2. Radiochemical conversions (RCCs) represent the conversion of radiocyanide (Rf = 0) to organic products measured via radio-thin-layer chromatography. Radiochemical purities (RCPs) verify product identity and represent purities of organic radiolabelled products measured via radio-high-performance liquid chromatography.

Scheme 4. Bioactive PET Imaging Scaffold Scope of Copper-Mediated Aryl Silane Radiocyanation.

All carbon-11 labelled nitrile compounds depicted were radiolabelled under manual conditions depicted in Scheme 2. See SI for complete details, including the automated one-pot radiosynthesis of 27-CONH2 from 27-(OTMS)2Me with manual reformulation. Radiochemical conversions (RCCs) represent the conversion of radiocyanide (Rf = 0) to organic products measured via radio-thin-layer chromatography. Radiochemical purities (RCPs) verify product identity and represent purities of organic radiolabelled products measured via radio-high-performance liquid chromatography. [1] Isolated decay corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) and radiochemical purity (RCP) with EtOH/saline reformulation. [2] Isolated decay corrected RCY and RCP without reformulation.

Fully automated doses of 27-11CONH2 reformulated with 5% EtOH in saline for patient injection were obtained in 17% isolated, decay-corrected RCY across two steps starting from 27-(OTMS)2Me, including optimised radiolabelling and unoptimized hydrolysis with NaOH and H2O2. The clinically ideal molar activity value of approximately > 37 GBq μmol−1 was comfortably surpassed at 124 GBq μmol−1 (non- decay corrected), demonstrating that this methodology delivers PET imaging agents that minimise contamination from non-radioactive adulterants. This template automated protocol can be conveniently adopted for clinical translation and streamlined PET imaging studies upon qualification with quality assurance and current good manufacturing practice criteria. Finally, the radiolabelling efficiency of heptamethylmethylaryltrisiloxanes was contrasted to boron and tin arenes to assist radiochemists with precursor selection. Notably, phenyl organoboron and organotin precursors such as PhBpin, PhB(OH)2, PhBF3K, and PhSnBu3 undergo radiolabelling under conditions previously developed in our laboratories. Still, they are less efficient than 1-(OTMS)2Me under the conditions developed here (see SI for complete details of comparative studies).16

Probing Key Intermediates

Preliminary studies were conducted to elucidate why 1-(OTMS)2Me outperforms other silicon motifs in copper-mediated radiocyanation. First, selected aryl silanes from Scheme 1 were subjected to the optimised reaction conditions, confirming that 1-(OTMS)2Me most efficiently undergoes radiolabelling (see SI for complete details). Next, fluorination experiments with 1-(OTMS)2Me and NMe4F•4H2O were followed by 1H, 19F, and 29Si NMR to understand the fate of the internal [Si(I)] and terminal [Si(T)] silicon atoms. The reaction of 1-(OTMS)2Me with NMe4F•4H2O in DMF-d7 in a sealed tube at 80 °C for 1 h led to quantitative protodesilylation, forming benzene (Scheme 5A). Neither FSiMe3 nor F2SiMe3, corresponding to deprotection of the trimethylsilyl groups, was detected by 1H or 19F NMR spectroscopy. Treatment of 1-(OTMS)2Me with NMe4F•4H2O in DMF-d7 at room temperature led to a disappearance of the 1-(OTMS)2Me internal Si(I) atom as determined by 29Si NMR spectroscopy. Concurrently, a new upfield signal was observed, consistent with expelling trimethylsilanolate (Scheme 5B). This experiment demonstrates a drastic change in the chemical environment of the internal Si atom in 1-(OTMS)2Me upon reaction with NMe4F•4H2O.

Scheme 5. Experiments to Probe Aryl Silane Intermediates.

(A) Reaction of 1-(OTMS)2Me with fluoride at 80 °C , followed via NMR.

(B) Reaction of 1-(OTMS)2Me with fluoride at room temperature, followed via NMR.

(C) Prior report of difluoro(methyl)(aryl)silane preparation.

(D) Comparison of radiolabelling efficiency with different substituents at PhSiR2Me

See SI for complete details of mechanistic experiments. NMR shifts are in ppm.

On this basis, we hypothesised that 1-(OTMS)2Me undergoes substitutive fluorination at the Si(I) atom, forming a transmetallation-active intermediate. Specifically, we considered the generation of 1-F2Me and/or higher transmetallation intermediates. Consistent with this hypothesis, 1-(OTMS)2Me exhibits enhanced reactivity compared to structural analogues, such as 1-(OEt)2Me, which contains ethoxy substituents that are expected to be poorer leaving groups (pKa(EtOH) = 16) vs. silanolate (pKa(R3SiOH) ≈ 11). We noted that difluoro(methyl)(aryl)silanes have been used as cross-coupling partners in other systems under modified reaction conditions and are readily synthesised from dialkoxy(methyl)(aryl)silanes and HF in EtOH (Scheme 5C).53,54 Therefore, the speciation of HF under the reaction conditions was investigated. Although NMe4F•4H2O was analytically pure by 1H and 19F NMR in D2O, samples dissolved in DMF-d7 displayed signals corresponding to NMe4HF2. Therefore, NMe4F•4H2O is likely a HF surrogate under the labelling conditions, which is a more soluble and reactive fluoride source than others tested (see SI).55 Despite these findings, 1-F2Me was undetected in the independent reaction of 1-(OTMS)2Me and NMe4F•4H2O in DMF-d7 by 1H, 19F, or 29Si NMR spectroscopy. Although 1-F2Me is stable in solvents like CDCl3, the dissolution of independently obtained samples in anhydrous DMF-d7 at room temperature initiates decomposition to defluorinated side products, observable by NMR. Furthermore, 1-F2Me rapidly decomposes to intractable compounds in DMF-d7 at room temperature following the addition of NMe4F•4H2O (see SI). Therefore, we considered whether 1-F2Me may still be an active intermediate in the labelling reaction but only transiently generated, thus making it challenging to detect spectroscopically.

1-F2Me was synthesized independently and subjected to the optimized labelling conditions to test this hypothesis. The radiochemical conversion and purity were comparable to those attained with 1-(OTMS)2Me (Scheme 5D; see SI for experiments with 1-F2Me). On this basis, a mechanism is proposed in Scheme 6. Dissolution of NMe4F•4H2O produces bifluoride that reacts with 1-(OTMS)2Me to generate 1-F2Me (and possibly higher fluorosilicates), which undergoes transmetallation to copper. The [11C]benzonitrile product is subsequently furnished following disproportionation and reductive elimination. An opened “catalytic” cycle is depicted, reflecting that this stoichiometric process could, in principle, be conducted with sub-stoichiometric quantities of copper using O2 as a recycling oxidant. Further investigations of the exact intermediates that undergo transmetallation will be the subject of future studies.

Scheme 6. Putative Mechanism of Aryl Silane Cu-Mediated Radiocyanation.

Summary

Inexpensive, stable, and non-toxic (hetero)aryl silicon reagents have been leveraged for nucleophilic copper-mediated radiolabelling. Electronically diverse (hetero)aryl heptamethyltrisiloxanes undergo radiocyanation in good to excellent radiochemical conversions and purities. Comparative studies demonstrate that a model precursor undergoes more efficient radiolabelling than analogous and widely used metalloid nucleophiles. The clinical relevance of this methodology has been thoroughly showcased, including an automated preparation of a κ−opioid receptor antagonist on a commercial radiosynthesis module. Preliminary mechanistic experiments implicate initial fluorination at the internal silicon atom of (hetero)aryl heptamethyltrisiloxanes to form transmetallation-active intermediates. Overall, radiochemists and imaging scientists can conveniently leverage aryl silanes to efficiently prepare [11C]benzonitrile derivatives for clinical PET studies while circumventing critical stability and toxicity challenges in related radiocyanation systems.

METHODS

General Procedure for the Radiocyanation of Aryl Heptamethyltrisiloxanes

In air, a 1 dram vial containing NMe4F•4H2O (8.3 mg, 50 μmol) was successively charged with a DMA solution of [11C]KCN (100 μL, ca. 100–1000 μCi, obtained via trapping [11C]HCN with 6 μmol KOTMS in 5 mL DMA), a DMA solution of 18-crown-6 (0.8 mg, 3 μmol, 100 μL), and Et3SiF (3.2 μL, 20 μmol). Separate solutions of Cu(OTf)2 (9 mg, 25 μmol) and the aryl trisiloxane substrate (10 μmol) in DMA (100 μL per solution, total reaction volume = 500 μL) were added simultaneously, and the vial was sealed with a screw cap fitted with a PTFE septum. The reaction was heated to 100 °C for 5 min and directly analysed via rTLC following the reaction (1:1 Hexanes: EtOAc or 4:1 DCM: MeOH). Radiochemical conversions (RCC) indicate the conversion of inorganic radiocyanide (Rf = 0) to organic products, as measured by rTLC. Following reaction completion and conversion analysis, MeCN (500 μL) was added, and the reaction was passed through a Millex®−0.2μm/25mm PTFE membrane syringe filter. Radiochemical identity and approximate radiochemical purities (RCP) were obtained via analytical rHPLC analysis. Further details regarding the methods can be found in the Supplemental Information.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Peter J. H. Scott (pjhscott@umich.edu).

Materials availability

The supplemental information includes (radio)synthetic methods, optimisation studies, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 19F NMR, 29Si NMR spectra, HRMS data, and HPLC data.

Data and code availability

All the data related to this study are available in the supplemental information. No code was generated.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2. Scope of Copper-Mediated Aryl Silane Radiocyanation.

(A) Carbocyclic Aryl Heptamethyltrisiloxane Radiocyanation Scope

(B) Heterocyclic Aryl Heptamethyltrisiloxane Radiocyanation Scope

See SI for complete details of aryl silane manual radiocyanation. Radiochemical conversions (RCCs) represent the conversion of radiocyanide (Rf = 0) to organic products measured via radio-thin-layer chromatography. Radiochemical purities (RCPs) verify product identity and represent purities of organic radiolabelled products measured via radio-high-performance liquid chromatography.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by the NIH [Award Numbers R01EB021155 (P.J.H.S., M.S.S.), K99EB031564 and R00EB031564 (J.S.W.)]. Abdias Noel and Taylor Spiller are thanked for their assistance with the manuscript review.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deng X, Rong J, Wang L, Vasdev N, Zhang L, Josephson L, and Liang SH (2019). Chemistry for Positron Emission Tomography: Recent Advances in 11C-, 18F-, 13N-, and 15O-Labeling Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2580–2605. 10.1002/anie.201805501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serdons K, Verbruggen A, and Bormans GM (2009). Developing new molecular imaging probes for PET. Methods 48, 104–111. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aboagye EO, Barwick TD, and Haberkorn U (2023). Radiotheranostics in oncology: Making precision medicine possible. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 73, 255–274. 10.3322/caac.21768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark A. Mintun, Albert C. Lo, Cynthia Duggan Evans, Alette M. Wessels, Paul A. Ardayfio, Scott W. Andersen, Sergey Shcherbinin, JonDavid Sparks, John R. Sims, Miroslaw Brys, et al. (2021). Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1691–1704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Lammertsma AA, and Innis RB (2021). 11C Dosimetry Scans Should Be Abandoned. J. Nucl. Med. 62, 158–159. 10.2967/jnumed.120.257402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooker JM, Reibel AT, Hill SM, Schueller MJ, and Fowler JS (2009). One-Pot, Direct Incorporation of [11C]CO2 into Carbamates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3482–3485. 10.1002/anie.200900112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson AA, Garcia A, Jin L, and Houle S (2000). Radiotracer synthesis from [11C]-iodomethane: a remarkably simple captive solvent method. Nucl. Med. Biol. 27, 529–532. 10.1016/S0969-8051(00)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Chen W, Holmberg-Douglas N, Bida GT, Tu X, Ma X, Wu Z, Nicewicz DA, and Li Z (2023). 11C-, 12C-, and 13C-cyanation of electron-rich arenes via organic photoredox catalysis. Chem 9, 343–362. 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qu W, Hu B, Babich JW, Waterhouse N, Dooley M, Ponnala S, and Urgiles J (2020). A general 11C-labeling approach enabled by fluoride-mediated desilylation of organosilanes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1736. 10.1038/s41467-020-15556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson Y, and Långström B (1994). Transition Metal-mediated Reactions using [11C]Cyanide in Synthesis of 11C-labelled Aromatic Compounds. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HG, Milner PJ, Placzek MS, Buchwald SL, and Hooker JM (2015). Virtually Instantaneous, Room-Temperature [11C]-Cyanation Using Biaryl Phosphine Pd(0) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 648–651. 10.1021/ja512115s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Niwa T, Watanabe Y, and Hosoya T (2018). Palladium(II)-mediated rapid 11C-cyanation of (hetero)arylborons. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 7711–7716. 10.1039/C8OB02049C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright JS, Kaur T, Preshlock S, Tanzey SS, Winton WP, Sharninghausen LS, Wiesner N, Brooks AF, Sanford MS, and Scott PJH (2020). Copper-mediated late-stage radiofluorination: five years of impact on preclinical and clinical PET imaging. Clin. Transl. Imaging 8, 167–206. 10.1007/s40336-020-00368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, and Qu W (2021). [11C]HCN Radiochemistry: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 4653–4682. 10.1002/ejoc.202100651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bongarzone S, Raucci N, Fontana IC, Luzi F, and Gee AD (2020). Carbon-11 carboxylation of trialkoxysilane and trimethylsilane derivatives using [11C]CO2. Chem. Commun. 56, 4668–4671. 10.1039/D0CC00449A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makaravage KJ, Shao X, Brooks AF, Yang L, Sanford MS, and Scott PJH (2018). Copper(II)-Mediated [11C]Cyanation of Arylboronic Acids and Arylstannanes. Org. Lett. 20, 1530–1533. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox PA, Leach AG, Campbell AD, and Lloyd-Jones GC (2016). Protodeboronation of Heteroaromatic, Vinyl, and Cyclopropyl Boronic Acids: pH–Rate Profiles, Autocatalysis, and Disproportionation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9145–9157. 10.1021/jacs.6b03283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook XAF, de Gombert A, McKnight J, Pantaine LRE, and Willis MC (2021). The 2-Pyridyl Problem: Challenging Nucleophiles in Cross-Coupling Arylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11068–11091. 10.1002/anie.202010631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, Placzek MS, Hooker JM, Vasdev N, and Liang SH (2017). [11C]Cyanation of arylboronic acids in aqueous solutions. Chem. Commun. 53, 6597–6600. 10.1039/C7CC02886E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenmund KW, and Struck E (1919). Das am Ringkohlenstoff gebundene Halogen und sein Ersatz durch andere Substituenten. I. Mitteilung: Ersatz des Halogens durch die Carboxylgruppe. Berichte Dtsch. Chem. Ges. B Ser. 52, 1749–1756. 10.1002/cber.19190520840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.v. Braun J, and Manz G (1931). Fluoranthen und seine Derivate. III. Mitteilung. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 488, 111–126. 10.1002/jlac.19314880107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clayden J, Greeves N, and Warren S (2012). Radical reactions. In Organic Chemistry. 2nd Ed. (Oxford University Press; ), p. 970. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb EW, Cheng K, Wright JS, Cha J, Shao X, Sanford MS, and Scott PJH (2023). Room-Temperature Copper-Mediated Radiocyanation of Aryldiazonium Salts and Aryl Iodides via Aryl Radical Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6921–6926. 10.1021/jacs.3c00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng K, Webb EW, Bowden GD, Wright JS, Shao X, Sanford MS, and Scott PJH (2024). Photo- and Cu-Mediated 11C Cyanation of (Hetero)Aryl Thianthrenium Salts. Org. Lett. 26, 3419–3423. 10.1021/acs.orglett.4c00929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FOOD AND DRUGS CHAPTER I–FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES (2018). (FDA).

- 26.Herron JR, and Ball ZT (2008). Synthesis and Reactivity of Functionalized Arylcopper Compounds by Transmetallation of Organosilanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16486–16487. 10.1021/ja8070804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luzi F, Gee AD, and Bongarzone S (2021). Silicon compounds in carbon-11 radiochemistry: present use and future perspectives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 6916–6925. 10.1039/D1OB01202A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, Choi J, Shin K, and Chang S (2012). Copper-Mediated Sequential Cyanation of Aryl C–B and Arene C–H Bonds Using Ammonium Iodide and DMF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2528–2531. 10.1021/ja211389g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, and Chang S (2013). Copper-Mediated Transformation of Organosilanes to Nitriles with DMF and Ammonium Iodide. Org. Lett. 15, 1990–1993. 10.1021/ol400659p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Brooks AF, Makaravage KJ, Zhang H, Sanford MS, Scott PJH, and Shao X (2018). Radiosynthesis of [11C]LY2795050 for Preclinical and Clinical PET Imaging Using Cu(II)-Mediated Cyanation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 1274–1279. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurung SK, Thapa S, Vangala AS, and Giri R (2013). Copper-Catalyzed Hiyama Coupling of (Hetero)aryltriethoxysilanes with (Hetero)aryl Iodides. Org. Lett. 15, 5378–5381. 10.1021/ol402701x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komiyama T, Minami Y, and Hiyama T (2016). Aryl(triethyl)silanes for Biaryl and Teraryl Synthesis by Copper(II)-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15787–15791. 10.1002/anie.201608667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang S-K, Kim T-H, and Pyun S-J (1997). Copper(I)-catalysed homocoupling of organosilicon compounds: synthesis of biaryls, dienes and diynes. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin 1 0, 797–798. 10.1039/A608384F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata M, Fukuyama N, Wada J, Watanabe S, and Masuda Y (2007). Platinum-catalyzed Aromatic C–H Silylation of Arenes with 1,1,1,3,5,5,5-Heptamethyltrisiloxane. Chem. Lett. 36, 910–911. 10.1246/cl.2007.910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rand AW, and Montgomery J (2019). Catalytic reduction of aryl trialkylammonium salts to aryl silanes and arenes. Chem. Sci. 10, 5338–5344. 10.1039/C9SC01083A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D, Zhao Y, Yuan C, Wen J, Zhao Y, and Shi Z (2019). Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Silylation of Biaryl-Type Monophosphines with Hydrosilanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 12529–12533. 10.1002/anie.201906975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng C, and Hartwig JF (2015). Iridium-Catalyzed Silylation of Aryl C–H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 592–595. 10.1021/ja511352u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karmel C, Rubel CZ, Kharitonova EV, and Hartwig JF (2020). Iridium-Catalyzed Silylation of Five-Membered Heteroarenes: High Sterically Derived Selectivity from a Pyridyl-Imidazoline Ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6074–6081. 10.1002/anie.201916015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karmel C, Chen Z, and Hartwig JF (2019). Iridium-Catalyzed Silylation of C–H Bonds in Unactivated Arenes: A Sterically Encumbered Phenanthroline Ligand Accelerates Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7063–7072. 10.1021/jacs.9b01972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esteruelas MA, Martínez A, Oliván M, and Oñate E (2020). Kinetic Analysis and Sequencing of Si–H and C–H Bond Activation Reactions: Direct Silylation of Arenes Catalyzed by an Iridium-Polyhydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19119–19131. 10.1021/jacs.0c07578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takada K, Hanataka T, Namikoshi T, Watanabe S, and Murata M (2015). Ruthenium-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Aromatic C–H Silylation of Benzamides with Hydrosilanes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 357, 2229–2232. 10.1002/adsc.201401078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakurai T, Matsuoka Y, Hanataka T, Fukuyama N, Namikoshi T, Watanabe S, and Murata M (2012). Ruthenium-catalyzed Ortho-selective Aromatic C–H Silylation: Acceptorless Dehydrogenative Coupling of Hydrosilanes. Chem. Lett. 41, 374–376. 10.1246/cl.2012.374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitano T, Komuro T, Ono R, and Tobita H (2017). Tandem Hydrosilylation/o-C–H Silylation of Arylalkynes Catalyzed by Ruthenium Bis(silyl) Aminophosphine Complexes. Organometallics 36, 2710–2713. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murata M, Ota K, Yamasaki H, Watanabe S, and Masuda Y (2007). Silylation of Aryl Iodides with 1,1,1,3,5,5,5-Heptamethyltrisiloxane Catalyzed by Transition-Metal Complexes. Synlett 9, 1387–1390. 10.1055/s-2007-980343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milenin SA, Ardabevskaia SN, Novikov RA, Solyev PN, Tkachev YV, Volodin AD, Korlyukov AA, and Muzafarov AM (2020). Construction of siloxane structures with P-Tolyl substituents at the silicon atom. J. Organomet. Chem. 926, 121497. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2020.121497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang B, Gao J, Tan X, Ge Y, and He C (2023). Chiral PSiSi-Ligand Enabled Iridium-Catalyzed Atroposelective Intermolecular C−H Silylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307812. 10.1002/anie.202307812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng C, and Hartwig JF (2014). Rhodium-Catalyzed Intermolecular C–H Silylation of Arenes with High Steric Regiocontrol. Science 343, 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox PA, Reid M, Leach AG, Campbell AD, King EJ, and Lloyd-Jones GC (2017). Base-Catalyzed Aryl-B(OH)2 Protodeboronation Revisited: From Concerted Proton Transfer to Liberation of a Transient Aryl Anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13156–13165. 10.1021/jacs.7b07444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadler SA, Tajuddin H, Mkhalid IAI, Batsanov AS, Albesa-Jove D, Cheung MS, Maxwell AC, Shukla L, Roberts B, Blakemore DC, et al. (2014). Iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation of pyridines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 7318. 10.1039/C4OB01565G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puentes LN, Makvandi M, and Mach RH (2021). Molecular Imaging: PARP-1 and Beyond. J. Nucl. Med. 62, 765–770. 10.2967/jnumed.120.243287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng M-Q, Nabulsi N, Kim SJ, Tomasi G, Lin S, Mitch C, Quimby S, Barth V, Rash K, Masters J, et al. (2013). Synthesis and Evaluation of 11C-LY2795050 as a κ-Opioid Receptor Antagonist Radiotracer for PET Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 54, 455–463. 10.2967/jnumed.112.109512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaur T, Shao X, Horikawa M, Sharninghausen LS, Preshlock S, Brooks AF, Henderson BD, Koeppe RA, DaSilva AF, Sanford MS, et al. (2023). Strategies for the Production of [11C]LY2795050 for Clinical Use. Org. Process Res. Dev. 27, 373–381. 10.1021/acs.oprd.2c00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hatanaka Y, Goda K, Okahara Y, and Hiyama T (1994). Highly selective cross-coupling reactions of aryl(halo)silanes with aryl halides: A general and practical route to functionalized biaryls. Tetrahedron 50, 8301–8316. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85554-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bott RW, Eaborn C, and Hashimoto T (1965). Organosilicon compounds XXXII. The cleavage of aryl-silicon bonds by sulphur trioxide. J. Organomet. Chem. 3, 442–447. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83573-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams DJ, Clark JH, and Nightingale DJ (1999). The effect of basicity on fluorodenitration reactions using tetramethylammonium salts. Tetrahedron 55, 7725–7738. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data related to this study are available in the supplemental information. No code was generated.