Abstract

Objective

To analyze treatment patterns, dosing variations, and reapplication rates of botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) and hyaluronic acid injections, with a focus on sex- and age-related differences in outcomes.

Methods

A prospective analysis was conducted on 164 patients treated with BoNT-A and/or hyaluronic acid injections. Patients were categorized by sex and age (<50 years or ≥50 years). Data on dosage, treatment regions, and reapplications were collected and analyzed for statistical significance.

Results

The study highlighted distinct differences in the application of BoNT-A and hyaluronic acid based on sex and age. For botulinum toxin, the average dose per patient was 55.3 ± 12.7 units. Men received higher doses in the procerus (7.7 ± 2.6 vs.5.7 ± 2.2 units, p = 0.02) and nasal muscles (6.5 ± 2.7 vs.5.3 ± 1.7 units, p = 0.02). Significant age-related differences were observed in the orbicularis oculi (11.0 ± 4.1 vs.14.3 ± 5.4 units, p = 0.02) and corrugator muscles (10.7 ± 3.0 vs.10.5 ± 2.2 units, p = 0.02), with patients ≥50 years requiring higher reapplication doses (p = 0.0001). For hyaluronic acid, men required greater volumes in the mandible (p = 0.0001), reflecting differences in anatomical preferences, whereas women received larger volumes in the lips (p = 0.01), chin (p = 0.02), pre-jowls (p = 0.02), and under-eye regions (p = 0.003), which align with more delicate and aesthetic enhancements.

Conclusion

Significant sex- and age-based differences were observed in the application of BoNT-A and hyaluronic acid. Men required higher doses for structural enhancement, while women showed a preference for treatments in aesthetic regions. Patients ≥50 years required higher doses and reapplications, reflecting age-related anatomical changes. These findings highlight the importance of individualized treatment strategies for optimizing outcomes in aesthetic procedures.

Keywords: Botulinum toxin, Hyaluronic acid, Aesthetic medicine, Age differences, Sex differences, Facial rejuvenation, Personalized treatment

1. Introduction

Minimally invasive aesthetic treatments, such as botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) and hyaluronic acid injections, have transformed the landscape of facial rejuvenation and enhancement. These procedures are widely recognized for their efficacy, safety, and ability to produce natural-looking results with minimal recovery time.1,2 BoNT-A is primarily used to reduce dynamic wrinkles by temporarily paralyzing overactive muscles, while hyaluronic acid, a naturally occurring substance, is used for facial contouring, volume restoration, and hydration.3,4

Despite their popularity, achieving optimal outcomes requires an individualized approach that considers patient-specific factors such as age, sex, and anatomical variations. Research has consistently shown that treatment responses can differ based on these variables, influencing the choice of dosage, injection techniques, and areas of focus.5,6 For example, men and women often exhibit distinct aesthetic goals and anatomical structures, necessitating sex-specific adjustments in BoNT-A doses and hyaluronic acid volumes. Similarly, younger patients may seek treatments to enhance features, while older individuals often prioritize correcting age-related volume loss and structural changes.7

Therefore, this study aims to explore these nuances by analyzing a cohort of 164 patients treated with BoNT-A (Dysport®) and/or hyaluronic acid injections. The investigation focuses on sex-based and age-based differences in dosing, reapplication rates, and treatment patterns. Specific attention is given to how these variables impact outcomes in different facial regions, including dynamic wrinkles, volume restoration, and contouring.

2. Methods

This study had a cross-sectional observational design, examining 164 patients who underwent aesthetic procedures: 43 received hyaluronic acid fillers only, 63 receiving BoNT-A treatment only, and 58 received both (Supplementary Table 1). The study aimed to assess the quantity of products used and the need for reapplication based on sex and age. Data collection was conducted over a six-month period (July to December 2024) to allow for recruitment of all participants. Patients were screened and treated at the Orofacial Institute of the Americas (IOA), in Piracicaba, São Paulo - Brazil, by qualified professionals specialized in these procedures, with validation by JMDF and RAM. Participants included individuals aged from 18 to 78 years, who requested specific aesthetic procedures (BoNT-A and/or hyaluronic acid fillers) in the face and neck regions. Exclusion criteria included patients with contraindications to the procedures, as well as those who exhibited unrealistic expectations during follow-up consultations; these individuals were excluded from the final analysis to preserve the reliability of the outcome assessments. All participants provided informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

The interventions consisted of BoNT-A applications and hyaluronic acid fillers administered by experienced professionals. Procedures followed standardized protocols and considered the individual anatomical characteristics and aesthetic goals of each participant, determined through detailed anamnesis and patient consultation.

Data collection involved standardized pre- and post-procedure photographs and clinical records. Personal data (age and sex), product details (brand, batch number, expiration date, reconstitution date, and application date), and validated instruments were used to evaluate the average product volume applied and the necessity for reapplications according to the material used and the treated region of the face or neck. Data collection timepoints included the pre-procedure planning phase, immediately after hyaluronic acid filler applications, and between 15- and 30-days post-BoNT-A application, in cases where reapplication was required. Follow-up visits allowed for the evaluation of BoNT-A effects as assessed by professionals. Additionally, standardized photographic records visually documented the outcomes.

BoNT-A was applied to the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face and neck for aesthetic purposes, with dosages tailored to each muscle based on the participant's age and sex. Hyaluronic acid fillers were injected as needed to improve or enhance volume in specific regions, aiming for individualized facial rejuvenation.

After data collection, a database was constructed. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). The analysis of the quantity of procedures involving hyaluronic acid focused on describing the absolute and relative frequencies of these procedures in relation to the independent variables (sex and age). For the sex-based analysis, patients were divided into two groups: male and female. For the age-based analysis, a cutoff of 50 years was used, as this is the age when the most significant changes in dermal and muscular structure occur.8,9 Chi-square tests were conducted to assess associations between these variables. For comparisons of the average botulinum toxin quantities applied by sex and age, Student's t-test was used. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study adhered to ethical guidelines and was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 78147324.1.0000.5220). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment. Additionally, the study followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/) guidelines, ensuring methodological rigor, transparency, and comprehensive reporting across all relevant aspects of the observational study design.

3. Results

3.1. Botulinum toxin

The study included 121 patients who received BoNT-A (Dysport®) injections, with an average age of 45.1 years (±12.2). Among these patients, 19 were male, with an average age of 37.9 years (±10.1), and 102 were female, with an average age of 46.5 years (±12.0). Reapplications were necessary in 10 cases, comprising 2 males and 8 females. The BoNT-A was reconstituted using 500 sU in 2 mL of saline solution. The average units of BoNT-A applied per muscle and the reapplication requirements are detailed in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of average units of botulinum toxin applied per muscle by sex in the study.

| Muscles | Total (n = 121) | Female (n = 102) | Male (n = 19) | Total Reapplication (n = 10) | Female Reapplication (n = 8) | Male Reapplication (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrugator muscles | 10.6 (±2.7) | 10.3 (±2.6) | 12.6 (±3.0) | 4 (±0.0) | 4 (±0.0) | – |

| Depressor anguli oris muscle | 4 (±1.1) | 4 (±1.1) | – | 1 (±0.0) | 1 (±0.0) | – |

| Depressor labii inferioris muscle | 3 (±1.2) | 3 (±1.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Levator labii superioris | 1.83 (±1.2) | 1.83 (±1.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi | 2.3 (±1.5) | 2.3 (±1.5) | – | – | – | – |

| Masseter | 60 (±0.0) | 60 (±0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Mentalis muscle | 4.2 (±0.8) | 4.2 (±0.8) | 4 (±0.0) | – | – | – |

| Nasal | 5.4 (±1.9) | 5.3 (±1.7) | 6.5 (±2.7)∗ | – | – | – |

| Occipitofrontalis muscle | 18.5 (±5.1) | 18.5 (±5.2) | 19.6 (±4.7) | 2.8 (±1.2) | 2.8 (±1.3) | 3 (±0.0) |

| Orbicularis oculi muscle | 12.3 (±4.9) | 12.6 (±5.0) | 10.9 (±4.1) | 6 (±4.0) | 8 (±4.0) | 3 (±1.4) |

| Orbicularis oris muscle | 5.3 (±2.3) | 5.3 (±2.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Platysma | 33 (±20.7) | 33 (±20.7) | – | – | – | – |

| Procerus muscle | 5.9 (±2.0) | 5.7 (±2.2) | 7.7 (±2.6)∗ | – | – | – |

| Temporal | 20 (±0.0) | 20 (±0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Average applied per patient | 55.3 (±12.7) | 55.6 (±13.7)∗∗∗ | 53.5 (±5.2) | 0.45 (±2.1) | 0.45 (±2.2) | 0.47 (±1.6) |

∗0.02; ∗∗∗0.0001.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of BoNT-A units per muscle by sex. Bars represent mean units applied for females (red) and males (blue). Significant differences (Student's t-test) are indicated by asterisks (∗P = 0.02; ∗∗∗P = 0.0001). The final column shows mean total units per patient.

3.1.1. Sex-based analysis

In the analysis by sex, two muscle regions demonstrated statistically significant difference. In the procerus muscle, the overall average dose was 5.9 (±2.0) units, with males receiving significantly more units (7.7 ± 2.6) compared to females (5.7 ± 2.2) (p = 0.02). No reapplications were required in this region. In the nasal region, the overall average dose was 5.4 (±1.9) units, with males receiving 6.5 (±2.7) units and females 5.3 (±1.7) units, again showing a statistically significant difference between sexes (p = 0.02). No reapplications were necessary for this region. The overall average dose of BoNT-A applied per patient was 55.3 (±12.7) units, with males receiving an average of 53.5 (±5.2) units and females receiving 55.6 (±13.7) units. The average reapplication dose per patient was 0.45 (±2.1) units, with males requiring 0.47 (±1.6) units and females requiring 0.45 (±2.2) units. A statistically significant difference between sexes was observed in the overall dosage applied (p = 0.0001) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

3.1.2. Age-based analysis

The study evaluated 121 patients, distributed into two age groups: those under 50 years (n = 77) and those aged 50 years or older (n = 44). Reapplications were required in 10 cases, with 6 occurring in patients under 50 and 4 in patients aged 50 and above. The average units of BoNT-A applied per muscle and the reapplication requirements are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of average units of botulinum toxin applied per muscle by age in the study.

| Muscles | Total (n = 121) | <50 years (n = 77) | ≥50 years (n = 44) | Total Reapplication (n = 10) | <50 years Reapplication (n = 6) |

≥50 years Reapplication (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrugator muscles | 10.6 (±2.7) | 10.7 (±3.0)∗ | 10.5 (±2.2) | 4 (±0.0) | – | 4 (±0.0) |

| Depressor anguli oris muscle | 4 (±1.1) | 3.7 (±1.0) | 4.2 (±1.1) | 1 (±0.0) | 1 (±0.0) | – |

| Depressor labii inferioris muscle | 3 (±1.2) | 2.7 (±1.2) | 4 (±0.0) | – | – | – |

| Levator labii superioris | 1.8 (±1.2) | 1.8 (±1.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi | 2.3 (±1.5) | 2.3 (±1.5) | 2.3 (±1.5) | – | – | – |

| Masseter | 60 (±0.0) | 60 (±0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Mentalis muscle | 4.2 (±0.8) | 4.1 (±0.8) | 4.3 (±0.8) | – | – | – |

| Nasal | 5.4 (±1.9) | 5.5 (±1.9) | 5.2 (±1.7) | – | – | – |

| Occipitofrontalis muscle | 18.5 (±5.1) | 18.2 (±5.4) | 19.1 (±4.6) | 2.8 (±1.2) | 2.8 (±1.5) | 3 (±1.0) |

| Orbicularis oculi muscle | 12.3 (±4.9) | 11.0 (±4.1) | 14.3 (±5.4)∗ | 6 (±4.0) | 2 (±0.0) | 7 (±3.9) |

| Orbicularis oris muscle | 5.3 (±2.3) | – | 5.3 (±2.3) | – | – | – |

| Platysma | 33 (±20.7) | 46 (±24.0) | 20 (±5.7) | – | – | – |

| Procerus muscle | 5.9 (±2.0) | 5.9 (±2.0) | 5.8 (±2.1) | – | – | – |

| Temporal | 20 (±0.0) | 20 (±0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Average applied per patient | 55.3 (±12.7) | 53.9 (±14.1) | 53.9 (±14.1) | 0.45 (±2.1) | 57.8 (±9.6)∗∗∗ | 0.93 (±3.3)∗∗∗ |

∗0.02; ∗∗∗0.0001.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of BoNT-A units per muscle by age group. Bars show mean units for patients <50 years (gray) and ≥50 years (black). Significant differences (Student's t-test, P = 0.02) are marked with asterisks. The final column shows mean total units per patient.

For the corrugator muscles, the overall average was 10.6 (±2.7) units, with the younger group receiving slightly more [10.7 (±3.0) units] compared to the older group [10.5 (±2.2) units]. Reapplications were only necessary in the older group, with an average of 4 (±0.0) units. Statistically significant difference between ages (p = 0.02). The orbicularis oculi muscle showed an average dose of 12.3 (±4.9) units overall, with patients under 50 years receiving 11.0 (±4.1) units and those aged 50 years or older receiving 14.3 (±5.4) units, a statistically significant difference (p = 0.02). Reapplications in this region averaged 6 (±4.0) units overall, with 2 (±0.0) units in the younger group and 7 (±3.9) units in the older group. The overall average BoNT-A dose per patient was 55.3 (±12.7) units. Patients under 50 years received an average of 53.9 (±14.1) units, while those aged 50 or older received 57.8 (±9.6) units, with a statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.0001). Reapplications averaged 0.45 (±2.1) units overall, with lower doses in the younger group [0.18 (±0.7)] compared to the older group [0.93 (±3.3)], another statistically significant finding (p = 0.0001).

3.2. Hyaluronic acid

The study included 101 patients who received hyaluronic acid injections, with an average age of 41.3 years (±13.4). Among these patients, 16 were male, with an average age of 35.3 years (±12.0), and 85 were female, with an average age of 42.4 years (±13.5). The average volume of hyaluronic acid applied per facial region is detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

3.2.1. Sex-based analysis

Upon analyzing the results, significant differences were observed in the amount of hyaluronic acid applied across different facial regions based on sex. Males generally required higher volumes in the mandible, reflecting differences in anatomical and facial structure preferences. In this region, a statistically significant difference was observed in the applications of hyaluronic acid between males and females, with a p-value of 0.0001. In contrast, females demonstrated a greater tendency to receive larger volumes in areas like the lips, chin and under-eye regions, which are associated with more delicate and aesthetically focused treatments. Regions like the lips, chin pre-jowls and under-eye showed p-values of 0.01, 0.02, 0.02 and 0.003, respectively, indicating statistically significant differences in treatment volumes (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of hyaluronic acid applications by sex in the study.

| Applied Area | Total (n = 101) | Male (n = 16) | Female (n = 85) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chin | 46 (12.6 %) | 2 (3.1 %) | 44 (14.6 %) | 0.02 |

| Labiomental groove | 4 (1.1 %) | – | 4 (1.3 %) | 0.35 |

| Lip | 67 (18.4 %) | 4 (6.3 %) | 63 (20.9 %) | 0.01 |

| Malar | 74 (20.3 %) | 12 (18.8 %) | 62 (20.6 %) | 0.78 |

| Mandible | 36 (9.9 %) | 20 (31.3 %) | 16 (5.3 %) | 0.0001 |

| Nasolabial Fold | 18 (4.9 %) | 3 (4.7 %) | 15 (5.0 %) | 0.92 |

| Nose | 19 (5.2 %) | 4 (6.3 %) | 15 (5.0 %) | 0.69 |

| Perioral | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (0.7 %) | 0.51 |

| Periorbital | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (0.7 %) | 0.51 |

| Philtrum | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (0.7 %) | 0.51 |

| Piriform fossa | 33 (9.0 %) | 7 (10.9 %) | 26 (8.6 %) | 0.59 |

| Pre-Jowls | 34 (9.3 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | 33 (11.0 %) | 0.02 |

| Temple | 1 (0.3 %) | – | 1 (0.3 %) | 0.64 |

| Under-eye | 27 (7.4 %) | 11 (17.2 %) | 16 (5.3 %) | 0.003 |

| Total | 365 | 64 | 301 | – |

Fig. 3.

Comparison of hyaluronic acid application sites by sex. Bars show the number of applications per region for females (red) and males (blue). Significant differences (Chi-square test; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.0001) are marked with asterisks. The final column shows total applications by sex.

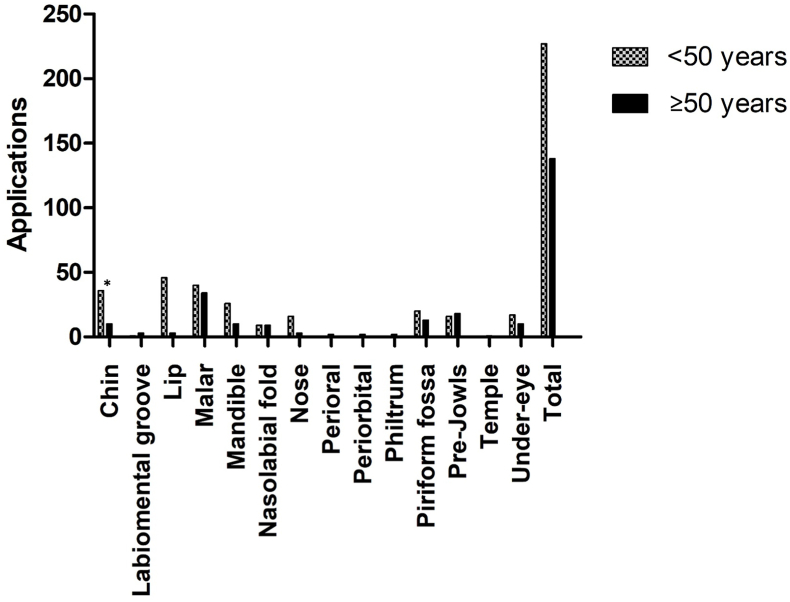

3.2.2. Age-based analysis

The age-based analysis of this study provides valuable insights into the distribution and outcomes of hyaluronic acid applications, revealing distinct treatment patterns across two age groups—those under 50 years (n = 16) and those aged 50 years or older (n = 85). Younger patients (under 50 years) exhibited a slightly higher number of applications in regions such as the lips, chin, malar area, mandible, nose, piriform fossa, and under-eye regions. This trend aligns with a focus on enhancing volume and contouring, addressing facial areas that benefit from more pronounced definition. In contrast, older patients (50 years and above) required more targeted treatments in areas like the labiomental groove, perioral and periorbital regions, philtrum, and pre-jowls. These findings underscore a greater emphasis on counteracting age-related changes, restoring facial symmetry, and addressing signs of aging. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between age groups, particularly in the chin area (p = 0.03), further highlighting the importance of tailoring treatments based on specific anatomical and aesthetic changes related to age (Table 4 and Fig. 4). These results emphasize the need for individualized treatment strategies, accounting for both age and unique facial features, to optimize the outcomes of hyaluronic acid applications.

Table 4.

Distribution of hyaluronic acid applications by age in the study.

| Applied Area | Total (n = 101) | <50 years (n = 16) | ≥50yeras (n = 85) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chin | 46 (12.6 %) | 36 (15.9 %) | 10 (7.2 %) | 0.03 |

| Labiomental groove | 4 (1.1 %) | 1 (0.4 %) | 3 (2.2 %) | 0.12 |

| Lip | 67 (18.4 %) | 46 (20.3 %) | 21 (15.2 %) | 0.31 |

| Malar | 74 (20.3 %) | 40 (17.6 %) | 34 (24.6 %) | 0.19 |

| Mandible | 36 (9.9 %) | 26 (11.5 %) | 10 (7.2 %) | 0.23 |

| Nasolabial Fold | 18 (4.9 %) | 9 (4.0 %) | 9 (6.5 %) | 0.29 |

| Nose | 19 (5.2 %) | 16 (7.0 %) | 3 (2.2 %) | 0.05 |

| Perioral | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (1.4 %) | 0.07 |

| Periorbital | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (1.4 %) | 0.07 |

| Philtrum | 2 (0.5 %) | – | 2 (1.4 %) | 0.07 |

| Piriform fossa | 33 (9.0 %) | 20 (8.8 %) | 13 (9.4 %) | 0.85 |

| Pre-Jowls | 34 (9.3 %) | 16 (7.0 %) | 18 (13.0 %) | 0.08 |

| Temple | 1 (0.3 %) | – | 1 (0.7 %) | 0.20 |

| Under-eye | 27 (7.4 %) | 17 (7.5 %) | 10 (7.2 %) | 0.93 |

| Total | 365 | 227 | 138 | – |

Fig. 4.

Comparison of hyaluronic acid application sites by age group. Bars show the number of applications per region in patients <50 years (gray) and ≥50 years (black). Significant differences (Chi-square test, P = 0.03) are marked with asterisks. The final column shows total applications by age group.

Additionally, four patients required under-eye overcorrection, which was managed with hyaluronidase (Biometil®) diluted to 1000 UTRs per 1 mL and administered at a dose of 1 unit per 1 cm2, effectively addressing the overcorrection in this delicate region.10

4. Discussion

Minimally invasive aesthetic treatments have demonstrated remarkable potential to enhance and rejuvenate facial characteristics across diverse age groups. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of facial aging and patients' evolving aesthetic preferences is pivotal for optimal treatment planning and long-term maintenance. Variations in BoNT-A applications and reapplications observed in this study underscore the influence of anatomical and physiological differences based on sex and age, a finding consistent with previous research.6,11 Men and women exhibit distinct facial characteristics, including differences in forehead size, brow position, and mandibular contour, which shape their aging patterns and necessitate tailored treatment protocols. This aligns with data from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery,12 reporting a 9 % increase in male patients seeking neuromodulator treatments from 2012 to 2017, highlighting a growing demand for sex-specific aesthetic solutions.

The study revealed that male patients required significantly higher doses of BoNT-A in muscles like the procerus and nasal regions. This observation corroborates with findings from clinical trials showing that men generally need elevated dosages in the glabellar complex due to their robust and larger muscle mass, particularly in the procerus and corrugator supercilii.11,13 Despite these anatomical differences, male patients predominantly seek subtle, natural-looking results, emphasizing the critical role of individualized treatment strategies that consider these nuanced sex-based variations.14

Age significantly influences the efficacy of BoNT-A applications. Patients aged 50 years and older generally require higher doses, especially in muscles such as the orbicularis oculi, which is indicative of age-related changes in dermal and muscular structures. These findings are consistent with literature emphasizing the need for age-specific treatment protocols to address the reductions in skin elasticity and muscle tone associated with aging.15 The study by Iozzo et al.16 investigated the impact of BoNT-A on facial aesthetics, noting that younger individuals experienced complete wrinkle removal, whereas older individuals only showed partial improvement. This disparity may be attributed to the higher or sometimes unrealistic expectations in older patients. In our study, patient satisfaction was assessed qualitatively through follow-up clinical interviews conducted between 15 and 30 days post-procedure. Patients exhibiting unrealistic expectations during these consultations were excluded from the final analysis to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the outcome evaluation. In addition to psychological factors, age-related physiological changes, such as decreased skin elasticity and increased facial soft tissue sagging with age, likely contribute to diminished aesthetic results from BoNT-A injections in older adults.6

According to Gangigatti et al.,17 the studies included in their review reported that BoNT-A was effective in treating moderate to severe facial wrinkles across all age groups. However, several factors affect the effectiveness of BoNT-A therapy. One such factor is the viscoelasticity of human skin, which varies depending on anatomical region and age.8,9 Carruthers et al.1 observed that the improvement in wrinkles with BoNT-A was consistently lower in patients over the age of 51 compared to those under 50. This may be due to the gradual degeneration of elastin and collagen networks, which cause the dermis to thin with age.8,9 Additionally, muscle content declines with age, potentially making the action of BoNT-A less effective.15 Moreover, the skin's ability to recover from stress diminishes with age,8,9 which may result in more pronounced wrinkles once the effect of BoNT-A dissipates.

Hyaluronic acid fillers exhibited notable variability in application, influenced by both sex and age. Women typically received larger volumes in areas such as the lips, chin, pre-jowls, and under-eye regions, reflecting a preference for softer, more nuanced aesthetic enhancements. These treatments were aimed at restoring volume and achieving a rejuvenated, youthful appearance, aligning with the general trend of women seeking to counteract age-related volume loss and soften facial contours.6 In contrast, men generally required greater volumes in the mandible, reflecting a desire for treatments that emphasize structural enhancement and facial strength. This preference aligns with the notion that men tend to favor more angular, defined facial features, which contribute to a stronger and more masculine appearance.18,19 The need for different treatment approaches based on sex-specific aesthetic goals has been well-documented in the literature, further emphasizing the importance of tailoring interventions to meet the distinct anatomical and aesthetic preferences of men and women.20 These findings highlight how the application of hyaluronic acid fillers should be adapted to account for the varying anatomical features and aesthetic aspirations between the sexes, ensuring both natural results and satisfaction with the outcome.

Age-based analysis revealed distinct differences in treatment preferences between younger and older patients. Younger individuals typically focused on volume augmentation in regions such as the lips, cheeks, and malar areas, reflecting their desire for pronounced contouring and enhancement. This trend aligns with research highlighting that younger patients often seek aesthetic procedures to improve facial symmetry and achieve more defined features.19,20 Volume loss and tissue laxity are not yet significant concerns in this demographic, making their aesthetic goals more centered around enhancement rather than correction.

Conversely, older patients demonstrated a greater demand for treatments targeting aging-related concerns, particularly the labiomental groove, pre-jowl region, and periorbital areas. These patients seek to restore facial symmetry and reduce the signs of tissue laxity and wrinkles, which are common manifestations of aging.21,22 The labiomental groove, for instance, is often associated with the loss of collagen and elastin, leading to increased skin sagging and the formation of deep lines.8,9 Similarly, the pre-jowl area, affected by both fat redistribution and skin laxity, is a prominent focus of treatment for older patients seeking rejuvenation.18 Furthermore, periorbital aging, characterized by skin thinning and the formation of fine lines and wrinkles, is commonly addressed with botulinum toxin and dermal fillers to restore a more youthful appearance.23 These findings emphasize the necessity of tailoring treatment strategies to address the specific anatomical and aesthetic needs of different age groups. The differences in treatment priorities underscore how facial aging impacts various regions and how effective treatment protocols must be age-adapted to address these unique concerns.

This study presents several notable strengths that contribute to its relevance and originality in the field of aesthetic medicine. First, it offers a comprehensive, real-world analysis of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures by examining the influence of sex and age on the application and efficacy of BoNT-A and hyaluronic acid fillers. By incorporating a diverse patient population and collecting data across multiple anatomical regions, the study provides valuable insights into how individualized characteristics affect treatment planning. The inclusion of both qualitative clinical interviews and dosage/application data enhances the depth of outcome assessment, while the exclusion of patients with unrealistic expectations strengthens the reliability of patient satisfaction evaluation. Furthermore, the study aligns with and expands upon current literature by highlighting specific sex- and age-based anatomical and physiological variations that impact both aesthetic demands and therapeutic responses. The active participation of experienced professionals in all treatment phases ensured standardized protocols and clinical accuracy. Altogether, the study reinforces the importance of tailored, evidence-based approaches in non-surgical facial rejuvenation and supports the continued evolution of personalized treatment protocols in aesthetic practice.

Despite these significant findings, this study has several limitations. The limited sample size, particularly the underrepresentation of male participants and the use of broad age categories with dichotomized age recording, constrains the extent to which these findings can be generalized to the broader population. Additionally, subjective assessment criteria for aesthetic outcomes introduce potential variability in evaluations. The cross-sectional design also limits insights into the durability and long-term effects of treatments. Variations in individual anatomy, lifestyle factors, and prior aesthetic procedures were not fully accounted for, potentially influencing outcomes. Future research should aim to address these limitations by employing larger, more diverse sample sizes and longitudinal designs to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

This study reinforces the importance of personalized treatment approaches in non-surgical aesthetic medicine. A nuanced understanding of sex- and age-related differences in facial anatomy, muscle dynamics, and aesthetic preferences enables clinicians to optimize treatment outcomes while meeting individual patient goals. By tailoring dosages and application techniques to these factors, practitioners can enhance both patient satisfaction and procedural efficacy.

Future investigations should focus on evaluating the long-term impacts of customized treatments through longitudinal studies. Moreover, integrating advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, imaging systems, and precision injection techniques could further refine treatment approaches, paving the way for more effective and individualized care in aesthetic medicine.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of considering sex- and age-related differences in minimally invasive aesthetic treatments, such as BoNT-A and hyaluronic acid applications. Men generally required higher doses and volumes in structurally significant areas like the procerus muscle and mandible, while women showed a preference for treatments in aesthetically delicate regions such as the lips and under-eye area. Age also played a critical role, with younger patients favoring volume enhancement in features like the lips and cheeks, while older patients required targeted interventions to address age-related changes, such as deep wrinkles and loss of facial volume. These findings emphasize the need for personalized treatment plans that account for anatomical, functional, and aesthetic differences to achieve optimal results. Tailoring interventions based on these variables can enhance patient satisfaction and improve outcomes, reinforcing the value of individualized approaches in aesthetic medicine.

Ethics approval

The study was submitted to and approved by the Research Ethics Committee on May 20, 2024. The proposing institution for this research is Centro Universitário Ingá – UNINGÁ (CAAE: 78147324.1.0000.5220).

Funding

The authors report no financial support or funding. This research and its publication were conducted independently.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors sincerely thank the Instituto Orofacial das Américas (IOA, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil) for providing access to the patients. Above all, we extend our deepest gratitude to the patients who generously participated in this study. Their trust and invaluable contributions were essential to its success.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2025.08.029.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Carruthers J.D., Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin in facial rejuvenation: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(11):709–722. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundaram H., Signorini M., Liew S., Almeida A.R.T., Wu Y., Braz A.V. Global aesthetics consensus: hyaluronic acid fillers and botulinum toxin type A—recommendations for combined treatment and optimizing outcomes in diverse patient populations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(3):1410–1423. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt F., Cazzaniga A., Maas C. Optimizing the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(8):1235–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedén P., Hexsel D., Cartier H., et al. Effective and safe repeated full-face treatments with AbobotulinumtoxinA, hyaluronic acid filler, and skin boosting hyaluronic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(7):682–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagien S., Cassuto D., Fitzgerald R. Anatomic considerations for injectables in aesthetic medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(4):587e–598e. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen J.L., Goodman G.J., de Almeida A.T., et al. Decades of beauty: achieving aesthetic goals throughout the lifespan. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(11):2889–2901. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupo M.P., Cole A.L. Cosmeceutical peptides. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20(5):343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kedlian V.R., Wang Y., Liu T., et al. Human skeletal muscle aging atlas. Nat Aging. 2024;4:727–744. doi: 10.1038/s43587-024-00613-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borzabadi-Farahani A., Mosahebi A., Zargaran D. A scoping review of hyaluronidase use in managing the complications of aesthetic interventions. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024;48(6):1193–1209. doi: 10.1007/s00266-022-03207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minokadeh A., Matarasso S.L., Jones D.H. Neuromodulators in men. Dermatol Surg. 2024;50(9S):S70–S72. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000004336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society of Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) Survey on dermatologic procedures. 2017. https://www.asds.net/medical-professionals/practice-resources/consumer-survey-on-cosmetic-dermatologic-procedures Available from:

- 13.Jones D.H., Kerscher M., Geister T., Hast M.A., Weissenberger P. Efficacy of incobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of glabellar frown lines in male subjects: post-hoc analyses from randomized, double-blind pivotal studies. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:S235–S241. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandhari R., Imran A., Sethi N., Rahman E., Mosahebi A. Onabotulinumtoxin type A dosage for upper face expression lines in males: a systematic review of current recommendations. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(12):1439–1453. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farashi F., Ghoncheh M., Moghaddam M.R.G., Soroosh Z. Evaluation of people's satisfaction with botulinum toxin injection for facial rejuvenation based on age. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2024;23(7):2380–2385. doi: 10.1111/jocd.16289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iozzo I., Tengattini V., Antonucci V.A. Multipoint and multilevel injection technique of botulinum toxin A in facial aesthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13(2):135–142. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangigatti R., Bennani V., Aarts J., Choi J., Brunton P. Efficacy and safety of Botulinum toxin A for improving esthetics in facial complex: a systematic review. Braz Dent J. 2021;32(4):31–44. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440202104127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagien S. Treatment of the pre-jowl area with hyaluronic acid filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28(3):309–313. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman M.P., Stanley R.L., Scalza P., Amore R.S. Facial rejuvenation with injectables: a review of the anatomy, physiology, and techniques of botulinum toxin and dermal fillers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(8):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe N.J., Farr S., Mars M., et al. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar frown lines. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(6):758–765. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rzany B., Koehler A., Kanz P., Kayi S., Tomford W. Application of injectable dermal fillers for the treatment of nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22(3):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carruthers J.D., Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin in the management of facial aging. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(3):209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narins R.S., Lee M., Zakine B., Keiffer R.S. The use of botulinum toxin for periorbital rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:164–168. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.