Summary

Genetic variation among populations reflects both past demographic events and current population connectivity. We investigate the primary drivers of genetic differentiation in American brown bears (Ursus arctos) using 108 nuclear genomes. Our analyses reveal that genome-wide distances conform to neither an isolation-by-distance model nor a bifurcating tree structure. Building on previous ancient-DNA and fossil studies, we propose a demographic scenario in which continent-wide admixture during the Late Holocene has obscured, but did not erase, the genetic legacy of earlier colonization waves and subsequent gene flow events. The most persistent signals of these past events are striking genetic similarities between populations now separated by water barriers, including Kamchatka and Southwest Alaska bears. Our findings underscore that convergence to migration-drift equilibrium takes time, making genetic distance an imperfect proxy for present-day population connectivity.

Subject areas: Animals, Phylogenetics, Biological classification, Evolutionary history

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Genetic distances among North American brown bears fit neither a tree nor an IBD-model

-

•

The distances partly reflect past events, partly current population connectivity

-

•

The western range limit of the grizzly bear is an admixture zone in central Alaska

-

•

Kodiak bears and Alaska Peninsula bears share recent ancestry with Kamchatka bears

Animals; Phylogenetics; Biological classification; Evolutionary history

Introduction

Evolutionary biologists often think of islands as evolutionary laboratories in which new varieties arise.1,2 The underlying driver is isolation, which permits populations to diverge unimpeded by gene flow.3 However, the very same condition promoting evolutionary change can also facilitate the opposite outcome: evolutionary stasis. Shielded from genetic exchanges on the mainland, insular populations can preserve their genetic ancestry. They are therefore of special interest for phylogenetic inference and have proven invaluable in genetic and linguistic studies alike.4,5,6 This evolutionary principle of preservation through isolation applies to all secluded populations, regardless of the nature of the barrier, whether geographical, ecological, or cultural. In this study, we show that one such “genetic refuge”, which existed in Southwest Alaska during most of the Holocene, now defines the major feature of the current population structure of North American brown bears (Ursus arctos).

Having been extirpated from most of its southern and eastern range, North American brown bears are still widespread throughout Alaska, western Canada, and the northwest of the lower 48 states (Figure 1A).7,8,9,10 Local variations in morphology once inspired early-20th-century naturalists to identify no fewer than 86 species of brown bears within North America alone.11 Virtually none of these supposed varieties survived scientific scrutiny, not even after their demotion to subspecies level.12 At present, most authorities recognize only two North American subspecies of brown bear: the insular Kodiak bear (U. a. middendorffi) and the ubiquitous grizzly bear (U. a. horribilis).8,13 All mainland populations, as well as those from the Alexander Archipelago in Southeast Alaska, are lumped in the latter subspecies, despite evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear genetic data for population stratification.14,15,16

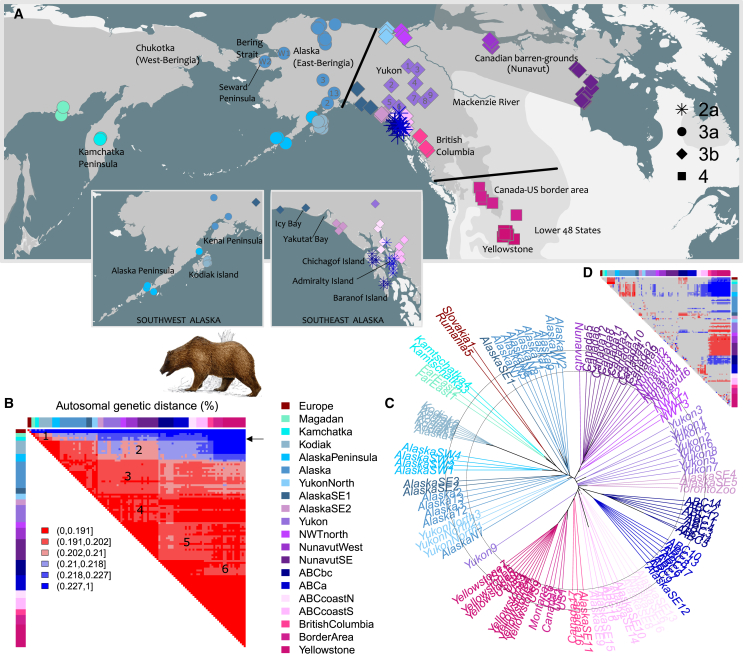

Figure 1.

North American brown bear population structure does not fit a bifurcating model

(A) Sample distribution. Dark and light gray: present-day and historic geographical range of brown bears (https://www.iucn.redlist.org). Symbol types indicate mtDNA haplotypes. Black lines indicate mtDNA discontinuities.

(B) Distance matrix. Annotated heatmap depicting autosomal sequence dissimilarity, E(p), between pairs of individuals. The transition from blue to red colors highlight that Kodiak bears and Alaska Peninsula bears (combinedly “Southwest Alaska”) cluster separately from other North American brown bears, with remaining Alaskan bears clustering intermediate. The arrow denotes the cross-section shown in Figure 3B. Numbers indicate major violations from a bifurcating tree model, and indicate excess allele sharing between populations of (1) Southwest Alaska and Far East Russia, (2) Southwest Alaska and Nunavut, (3) central Alaska and Nunavut as well as Yukon and Southeast Alaska, and a shortage of allele sharing between populations in (4) Yukon and Nunavut, (5) Southeast Alaska and Nunavut, and (6) lower 48 states and Baranof/Chichagof Islands.

(C) Autosomal dendrogram. Unrooted multi-locus bioNJ dendrogram (“tree of individuals”), constructed from the distance matrix in (B). The concentric circles have been added to aid visual interpretation, and highlight the distinctness of Southwest Alaskan bears, and to a lesser extent of central Alaska bears. Note also the slightly elongated branches leading to bears of Baranof and Chichagof Islands (“ABCbc”), which indicate slightly elevated genetic distances to other brown bears, resulting from gene flow from polar bears and their isolation from the mainland. The long internal branch of Kodiak bears signals a population bottleneck, which resulted in a loss of genetic variation.

(D) Residual error matrix, depicting the difference between tip-to-tip path lengths of the dendrogram and the corresponding entries in the distance matrix. Note, for instance, that the dendrogram underestimates the distance between bears in the lower 48 states and those in Kamchatka and southwest Alaska, while overestimating the distance between the former and the barren-ground grizzlies of Nunavut, as well as the distance between Kodiak bears and Far Eastern Russian bears, particularly Kamchatka bears. These discrepancies are indicative of non-bifurcating population splitting.

The taxonomic uncertainty surrounding North American brown bears shows from the different interpretations of the term “grizzly bear”. While this term is now officially reserved for all members of U. a. horribilis, thus all North American brown bears except Kodiak bears, the traditionally held distinction between coastal “brown bears” and smaller inland “grizzlies”17 still lingers. Here, we will assume the official definition, and use the term “grizzly” to refer to the subspecies U. a. horribilis as a whole. Furthermore, we will use the term “Southwest Alaska” to refer exclusively to Kodiak Island and Alaska Peninsula. This interpretation differs from the official meaning of the term, according to which Southwest Alaska encompasses a much larger region.

With sequencing costs still rapidly declining, such that it has become affordable to sequence the nuclear genomes from hundreds of individuals per species, we can revisit the phylogeography of the North American brown bear. Being composed of thousands of independently evolving loci, nuclear genomes cancel out the single-locus stochastics which may confound mtDNA-inferences and which hence should not be guiding subspecies designation decisions.18,19,20,21,22 In addition, the sex chromosomes may store information about sex-biased gene flow events.16 This allows the mapping of the contemporary geographical variation of a species with unprecedented detail, and even to infer the past demographic processes which generated this present-day population structure.

We compiled and analyzed the largest and most comprehensive resequencing dataset of North American brown bears to date, consisting of 108 genomes across the continent (Figure 1A and Table S1). Of these, 40 were newly generated for this study, selected to fill in critical regions not covered by previous studies.16,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 We interpreted our findings in the light of previously published subfossil and ancient-mtDNA inferences, which revealed that North America was colonized by brown bears from Eurasia during multiple migration waves.30,31 These studies also ruled out the presence of brown bears in Southeast Alaska, including the ABC Islands, throughout the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)32 as well as the absence of brown bears in central Alaska during the greater part of the Holocene.31 By integrating this existing knowledge with novel insights obtained from the genomic data, we further unravel the evolutionary history of brown bears in North America.

Results and discussion

A partial fit with a bifurcating tree model

Consistent with the hypothesis of multiple colonization waves, our analyses reveal a complex population structure shaped by fission and fusion of lineages. This becomes immediately evident when collapsing the genomic data to a distance matrix containing point estimates of autosomal sequence dissimilarity, E(p), between all pairs of individuals.33 This matrix is characterized by numerous violations of the tree-like pattern of variance and covariance blocks (Figure 1B).34,35 These deviations from “treeness” mean that the distances between individuals are not additive and hence cannot be accurately represented by a bifurcating dendrogram, irrespective of the tree reconstruction method (Figures 1C, 1D, S1, and S2).

Whereas the absolute proportional difference between tip-to-tip pathlengths and actual distance is for most sample pairs small (<1.5%), for certain population pairs the residual error is consistently higher (Figures 1D and S2), suggesting these populations were affected by gene flow the most. For instance, Southwest Alaska bears and Yellowstone bears share alleles with bears in intermediate regions, but not with each other, and hence a contrived binary splitting tree model underrepresents their actual genetic distance (Figures 1C and S2).

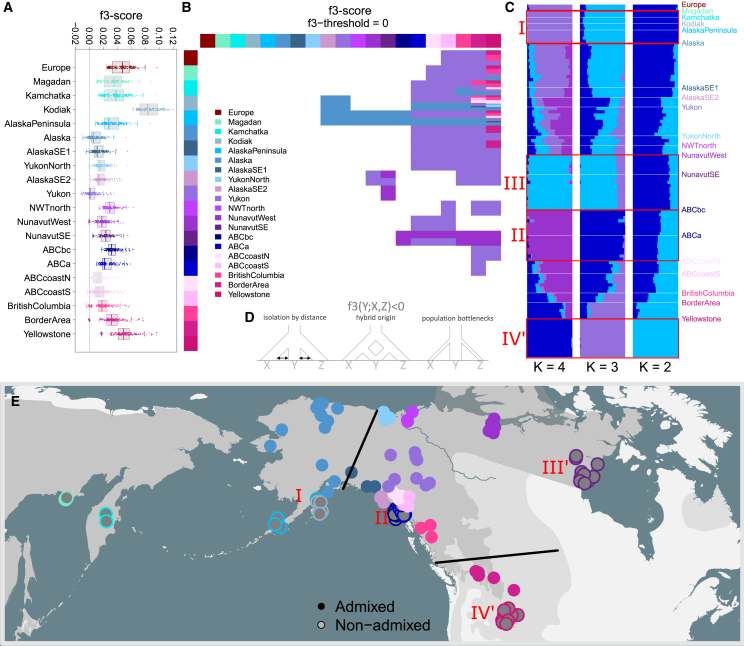

A partial fit with IBD model predictions

Instead of a bifurcating model, certain aspects of population structure of North American brown bears are better explained by an isolation-by-distance (IBD) model, according to which genetic distances between populations solely depend on present-day population connectivity. For instance, ancestry and f3-analyses indicate that all but the most peripheral populations are admixed due to recent or ongoing gene flow (Figures 2, S3, and S4). The primary source populations for admixed populations consistently belong to the geographically nearest genetic cluster. That is, brown bears in Southwest Alaska bears, southeastern Nunavut, ABC Islands, and Yellowstone are the primary donors of brown bears in central Alaska, western Nunavut, Southeast Alaska (south of Icy Bay), and southern British Columbia, respectively (Figure 2). These source populations either contributed directly, or, as in the case of Kodiak bears and ABC bears, are closely related to the true source populations on the nearby mainland.

Figure 2.

Continent-wide admixture is obscuring the genetic legacy of past demographic events

(A) f3-scores for all population triplets. Boxplots are overlayed with stripcharts, depicting f3-scores for all population triplets, and grouped by putative recipient population. See (B) for more explanation.

(B) f3-heatmap. Heatmap highlighting population triplets (Y; X,Z) with negative autosomal f3-scores. A negative f3-score, calculated as (y-x)·(y-z), indicates that allele frequencies y in population Y are intermediate between the allele frequencies x and z in populations X and Z. The colors in the row and column bars represent populations X and Z, while field colors denote population Y. For instance, population “Alaska” has allele frequencies intermediate between Southwest Alaska bears (Kamchatka, Alaska Peninsula) and all remaining North American populations. The population ‘Alaska' was represented only by the genetic cluster consisting of the samples ‘Alaska2', ‘Alaska3', ‘Alaska12' and ‘Alaska13'. The population ‘Yukon' was represented only by the samples ‘Yukon2', ‘Yukon5', ‘Yukon6', ‘Yukon7', and ‘Yukon8'.

(C) Ancestry analyses. Admixture plots, generated with the R package LEA, depicting ancestry coefficients assuming two to four ancestral populations. The inbred Kodiak bears are represented by two randomly chosen individuals.

(D) Admixture scenarios. Schematic diagrams of the demographic scenarios that can result in an admixture signal. The f3-test aims to detect admixture (left and center diagram), but a negative f3-score may also indicate a scenario in which a large source populations buds of two smaller sister populations (right diagram), as allele frequencies may randomly drift in opposite directions.

(E) Spatial overview. Geographical locations of admixed individuals (closed circles) and non-admixed individuals (open circles), which are all peripheral.

Yukon grizzlies, at the very center of the species’ range, share ancestry with bears from all directions, but particularly so with the populations of ABC Islands and Southwest Alaska, and least with those of the lower 48 states and the Canadian barren-grounds (Figure 2C). Ancestry proportions vary considerably across individuals within the Yukon population. As a result, Yukon grizzlies do not cluster as a single unit in the autosomal dendrogram but instead form a collection of separate branches (Figure 1C). Such indistinct clustering also characterizes, albeit to a lesser extent, central and Southeast Alaska bears (Figure 1C). This partly reflects the geographic spread of these samples, but it also indicates that the genetic distances of these individuals to other populations vary extensively, and that admixed alleles are not yet distributed homogeneously within these populations. This is a hallmark of recent admixture,36 especially when observed in combination with raised levels of genetic diversity (Figure S5).

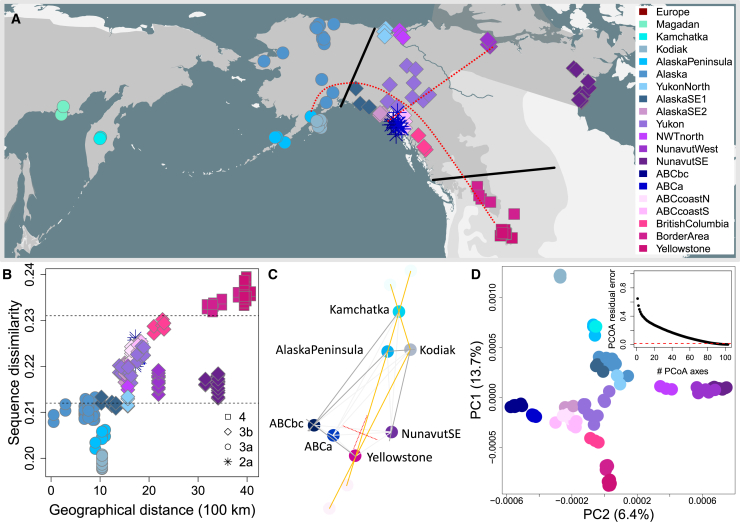

Another prediction of the IBD-model is that the genetic variation among a set of populations is explained by longitude and latitude, not by past population splits. Consistent with this expectation, when applying principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to the distance matrix of whole-genome E(p)-estimates, the two primary axes roughly correspond to a north-south axis and a west-east axis (Figures 3D and S6–S8).

Figure 3.

North American brown bear population structure does not fit an IBD-model

(A) Sample distribution. Dark and light gray: present-day and historic geographical range of brown bears. The red lines roughly indicate the PCoA-axes (see D).

(B) Apparent isolation-by-distance trend. Scatterplot depicting multi-locus sequence dissimilarity (in %) to Kamchatka bears (y axis) against great-circle distance to the Seward Peninsula, east of the Bering Strait (x axis). The dashed lines separate mtDNA clades, which presumably correspond to three consecutive colonization waves into North America. The parapatric distribution of these three admixing lineages give the false impression of a simple isolation-by-distance trend.

(C) Dxy-network. Graphical summary of genetic distances between population, with edge lengths being proportional to Dxy – 0.0017. Highlighted in dark grey and orange are edges which do not fit the corresponding node-to-node distances. These discrepancies indicate that a 2D IBD-model is insufficient to explain genetic distances, even for this subset of populations. The perpendicular pair of red lines roughly indicates the orientation of the PCoA-axes (see D).

(D) PCoA. Scatterplot depicting the first two PCoA-axes summarizing autosomal genetic distances between individuals. The first axis, shown on the y axis, roughly corresponds to an axis running from northwest to southeast, and highlights the differences between Southwest Alaska bears and Yellowstone grizzlies. The second axis corresponds to a perpendicular west-east axis and highlights the differences between ABC Islands bears and Candian barren-ground grizzlies. Note, however, that the Euclidean distances between samples, suggested by this 2D-PCoA-plot, differ on average over 50% from the true genetic distances (see inset). The red line depicts the residual error of the bioNJ tree in Figure 1.

However, other predictions of the IBD-model do not hold true. For instance, the superficial correlation between geographic and genetic distance is misleading, as it primarily reflects the parapatric distribution of the various mtDNA-lineages left behind by the successive migration waves identified by ancient-mtDNA studies31 (Figure 3B). Whereas an IBD-model predicts a gradient of genetic distances,37,38,39 the empirical data reveals abrupt transitions, roughly coinciding with the contact zones between mtDNA-lineages (Figures 3B–3D). Within each mtDNA-lineage, the correlation between genetic and geographical distance is weak or absent (Figure 3B).

Another prediction of the IBD-model, which can be derived by simulating allele frequencies using a 2D stepping stone model40 (Figure S9), is that islands populations are outgroups relative to all mainland populations.41,42 Instead, the empirical data indicate that bears of Kodiak Island and Baranof/Chichagof Islands are genetically similar to nearby populations on the opposite side of the marine barrier (Figure 3C), despite being separated since the Early Holocene. The extreme clustering of Kodiak bears on the first PCoA-axis, away from Alaska Peninsula bears (Figure 3D), is partly caused by the sensitivity of PCoA to genetic diversity within populations (which is low in Kodiak bears), and exaggerate the absolute distance between Kodiak bears and Alaska Peninsula bears.

These violations of the IBD-model predictions indicate that genetic distance cannot be attributed solely to present-day population connectivity. Instead, past events also need to be taken into consideration. The picture which therefore emerges is one of a system in transition, with a former population structure gradually being obscured by present-day population connectivity,8,43,44 but with the new migration-drift equilibrium still far from having been reached.

The most striking lingering signals of past population structure are instances of negative correlations between geographic and genetic distance. For example, Southwest Alaska bears appear genetically slightly more similar to barren-ground grizzlies in southeastern Nunavut than to barren-ground grizzlies in western Nunavut, despite the latter being geographically closer (Figures 3B, S10, and S11). In addition, these barren-ground grizzlies are genetically more similar to Yellowstone bears than to neighboring populations in Yukon Territories (Figure S6A). The differences in E(p)-estimates between these population pairs may appear negligible, but they are statistically significant, outweighing the variation in the data caused by sequencing artifacts and/or genotype calling errors (Figures S10 and S12).

Low population differentiation

Overall, the Dxy-estimates for any population pair in North America vary between 0.185% and 0.225% (Figures 1B and S11). This relatively narrow range reflects the low magnitude of mutation rates45 and the relatively short time intervals between successive population splits within species. For populations that split in the Late Pleistocene, let alone the Holocene, these intervals typically do not exceed a few thousands of generations, implying that most observed variation is ancestral, with only a small proportion stemming from novel mutations.

Because genetic distances between young sister populations often barely exceed within-population distances, with Hudson FST-estimates being generally below 0.2 (Figure S13), shared ancestries can easily be obscured by gene flow, complicating phylogenetic inference. Fortunately, there are several work-around solutions to this problem. One such solution is a “space-for-time” substitution, based on the assumption that populations on land bridge islands are relict populations which can reveal ancestral relationships as they were before Holocene population mixing. X chromosomes may also be useful to infer past signals, as these chromosomes are less affected by male-mediated gene flow.16 With the additional advantage of insights obtained from time-series data in previous brown bear studies,31 we can lift the cover of recent admixture events, and attempt to unveil what lays underneath: the signals of phylogeographic events further back in time.

Southeast Alaska bears are a distinct outgroup

The genomic data do not support the current subspecies designation between grizzly bears (U. a. horribilis) and Kodiak bears (U. a. middendorffi), and certainly not the traditionally held distinction between coastal “brown bears” and inland “grizzlies”.8 Instead, both distance-based and multispecies coalescent based analyses indicate a primary dichotomy that separates bears in the most southwestern part of Alaska from all other populations, except for central Alaska bears, which cluster intermediate, suggesting an admixture zone (Figures 1B, 1C, 2B, 2C, S14, and S15).

The distinct southwestern Alaska bears are found on Kodiak Island (U. a. middendorffi) as well as on the nearby Alaska Peninsula, including Katmai National Park (previously U. a. gyas, now U. a. horribilis). They are genetically so different from other North American bears that they are, in fact, more similar to the large coastal bears of Far East Russia, in particular Kamchatka bears (Figures 1B and 1C, and S11).16 The Dxy-estimate for Kodiak bears versus Yellowstone bears and ABC Islands bears is 0.227% and 0.207%, compared to 0.192% for Kodiak bears versus Kamchatka bears (Figures 1B and S11).

This similarity between brown bears on opposite sides of the Bering Strait, previously inferred from morphological data,17 cannot be explained by contemporary population connectivity. The Aleutian Islands span from Kamchatka to the southern tip of the Alaska Peninsula, but their wide spacing and the harsh Arctic regime rules out island-hopping. The only available route was a detour via the former Bering Landbridge, which submerged approximately 10 kya due to rising sea levels.46,47,48 Since then, snow-covered ice seasonally spans the Bering Strait, facilitating occasional crossings.49 However, Far East Russian bears that crossed the land bridge or ice bridge, would have had the opportunity to interbreed first with bears in western Alaska, rather than Southwest Alaska alone, and so this does not clarify the observed genetic structure.

The remaining explanation is that the remote Kamchatka and Alaska Peninsulas have each acted as secluded refuges, where sister lineages of brown bears have existed relatively undisturbed for millennia, out of reach of the genetic influxes from unrelated lineages. According to this hypothesis, Kamchatka bears and Southwest Alaska bears both derive from a shared ancestral population that endured through the LGM and subsequent Late Glacial stadials in Beringia, a region that corresponds to Alaska (USA) and present-day Chukotka (Russia). This ancestral lineage was bisected by the incipient Bering Strait around 10 kya. Since then, the orientation and narrowness of the isthmus that connects the Kamchatka Peninsula, has excluded resident bears from a widespread admixture event that after the LGM ensued in Yakutia between Beringian bears and a lineage of bears that expanded from a glacial refuge in southeast Asia.16

The isolation of Southwest Alaska bears, across the Bering Strait, was likely caused by ecological factors rather than geographical features. Until human-induced range fragmentation during the past two centuries, all brown bear populations on the North American mainland were supposedly interconnected.44 However, this unrestricted population connectivity did not exist for long. A conspicuous gap in the fossil record suggests that brown bears were absent from most of Alaska, and possibly adjacent regions, for most of the Holocene,31,50 concomitant with the extinction of other megafaunal species across the continent.51,52 Their extirpation likely coincided with the flooding of the Bering Strait, leaving a limited time for renewed migration of Eurasian bears into Alaska. The genetic similarity between Kamchatkan bears and Southwest Alaska bears appears to indicate that some bears of lineage mtDNA 3a managed to navigate the flooding causeway from west to east before it submerged entirely. If so, this event would have entailed the last pulse in a series of migration waves.31

It is noteworthy that at present Kamchatka bears and Kodiak bears are roughly equidistant to Yellowstone bears (Dxy = 0.229% and 0.227%, respectively), but not equidistant to bears of Baranof and Chichagof Islands (Dxy = 0.218% and 0.209%), nor to bears of eastern Nunavut (Dxy = 0.209% and 0.200%). Kodiak bears and those of Baranof and Chichagof Islands have been effectively separated from the mainland throughout the Holocene, and hence this difference cannot be attributed to recent gene flow. This suggests that the founder population, which crossed the flooding Beringian land bridge, admixed with residents shortly after its arrival.

Whatever their exact ancestry, the Early Holocene extirpation event in central Alaska left a peripheral population of Beringian bears, carrying haplotypes of mtDNA-clade 3a, sequestered on the remote Alaska Peninsula. Elsewhere on the continent, their Beringian relatives of mtDNA-clade 3b interbred with a distant lineage of Midcontinental bears of mtDNA-clade 4, which had entered North America during one of the first migration waves, and which had subsequently survived the LGM south of the conjugated Cordilleran and Laurentide Ice sheets.31,53,54 Isolated from this genetic exchange, Alaska Peninsula bears could preserve the genetic ancestry of their Beringian Ice Age ancestors. The Late Holocene recolonization of central Alaska ended the isolation of Alaska Peninsula bears, except for the insular population stranded on Kodiak Island. This explains why today Kamchatkan bears are even more similar to Kodiak bears (Dxy = 0.192%) than they are to Alaska Peninsula bears (Dxy = 0.197%) (Figures 1B,C, and S11).

At the same time, the genetic similarity between the mainland and island populations in Southwest Alaska, on opposite sides of the Shelikof Strait, indicates that the recent admixture did not yet obscure the common ancestry of Kodiak bears and Alaska Peninsula bears. This may also be inferred from shared phenotypical characteristics among the two populations, which includes exceptionally large body and skull sizes, not observed elsewhere on the continent, not even in other coastal regions with similar resource availability.12,17,55,56 For instance, Hall12 found that skull sizes differ more dramatically between north Alaska bears and Alaska Peninsula bears, than between the former and Kenai Peninsula bears, across Cook Inlet.

Because Southwest Alaska bears only recently joined the continent-wide genetic exchange between the Beringian and Midcontinental lineages, the largest population-pairwise differences among North American brown bears are those between Southwest Alaska bears and lower 48 states bears. This division constitutes the first split in the dendrograms relative to the outgroup of Eurasian bears (Figures 1C and S1), and is also emphasized by the first axis of the PCoA-plot (Figure 3D).

Four X chromosome genetic clusters

Because X-chromosomal Ne is 3/4th of autosomal Ne, genetic differentiation through lineage sorting in fragmented populations proceeds faster at X chromosomes than at autosomes.57 Furthermore, given that male immigrants pass on their X chromosomes only to female offspring, X chromosomes are less affected by gene flow when primarily male mediated,6,16 as in the case of brown bears.44,58,59,60

X chromosome FST-values of recently reconnected populations are therefore expected to be above autosomal FST-values (Figure S13). Consistent with this expectation, the X chromosome distance matrix and dendrogram accentuate the similarity of Southwest Alaska bears to Far East Russian bears (particularly Kamchatka bears), as well as their dissimilarity relative to lower 48 states bears (Figures 4, and S17). In contrast, owing to the smaller X chromosome Ne and lower X chromosome mutation rates, absolute genetic distances are expected to be smaller than their autosomal counterparts.6,57 Consistent with this expectation, X chromosome Dxy-estimates are roughly half as high as autosomal Dxy-estimates, ranging between 0.05% and 0.12% (Figures 4B and S16). When using an arbitrary threshold value of 0.07%, four clusters of closely related individuals emerge (Figure 4B). Apart from Southwest Alaska (discussed previously), these clusters are located along the coastline of Southeast Alaska, on the Canadian barren-grounds east of the Mackenzie River, and, lastly, across a vast expense covering British Columbia and the lower 48 states.

Figure 4.

X chromosome data reveals four genetic clusters, of which at least two originated before the Holocene

(A) Sample distribution. Dark and light gray: present-day and historic geographical range of brown bears. Symbol types indicate mtDNA haplotypes. Black lines indicate mtDNA discontinuities. Roman letters indicate the locations of the four genetic clusters (see B, D, and E).

(B) Distance matrix. Heatmap depicting X chromosome sequence dissimilarity. The solid lines delineate four clusters with genetic distances below 0.069%. Note that cluster I and cluster II consist of populations separated by Holocene water barriers, suggesting a Late Glacial origin.

(C) Dxy-network. Graphical summary of absolute genetic distances between populations, with edge lengths being proportional to Dxy – 0.00062. Edges which do not fit the corresponding node-to-node distances are in dark grey or orange. The perpendicular pair of red lines roughly indicates the orientation of the PCoA-axes (see D).

(D) PCoA. Scatterplot depicting the first two PCoA-axes summarizing X chromosome genetic distances between individuals. The first axis, shown on the y axis, highlights the differences between Southwest Alaska bears and Yellowstone grizzlies. The second axis highlights the differences between ABC Islands bears and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies.

(E) X chromosome dendrogram. Unrooted multi-locus bioNJ dendrogram, constructed from X chromosome genetic distances. The Roman numbers highlight the four genetic clusters. Note that populations that are not part of the four genetic clusters assemble as a collection of independent branches, especially Yukon grizzlies.

(F) Residual error matrix, depicting for each population pair the mean difference between tip-to-tip path lengths of the dendrogram and the corresponding entries in the distance matrix.

The smallest geographic cluster is the one in Southeast Alaska. This cluster does however extend across water barriers, and includes not only Admiralty Island (“ABCa”) and the nearby Baranof and Chichagof Islands (“ABCbc”) but also a small stronghold on the mainland, west of the Coast Mountains. Some bears in this coastal region are in terms of X chromosome distances closer to Admiralty bears (Figure 4) than to other mainland bears. This finding cannot reflect recent gene flow from the Admiralty Island to the mainland, because it does not show up in autosomal data, even though only males have been reported to make the crossing.8

Conveniently, the presence of insular populations allows to roughly infer the minimum age of this genetic cluster (cluster II). The Chatham Strait has kept the population on Admiralty Island (“ABCa”) separate from the meta-population on Baranof and Chichagof Islands (“ABCbc”) throughout the Holocene.8 Their common ancestry must therefore date back to the Late Pleistocene. Because no evidence exists for continued survival of brown bears in Southeast Alaska during the LGM,32 the origin of cluster II can be further narrowed down to the Late Glacial, 19.0–11.7 kya.

A similar reasoning applies to the genetic cluster encompassing Kodiak bears and Alaska Peninsula bears (cluster I), since these two populations have also been separated by an insurmountable Holocene water barrier, namely the Shelikov Strait,7 and since mtDNA-clade 3a did not enter eastern Beringia before the start of the Holocene, 11.5 kya.31

Reconstructing postglacial recolonization

Because peripheral populations, especially insular populations, have been least affected by recent admixture events, their genetic distances to each other allow investigating demographic events further back in time, when the four X chromosome genetic clusters were first established, presumably during the Late Glacial.

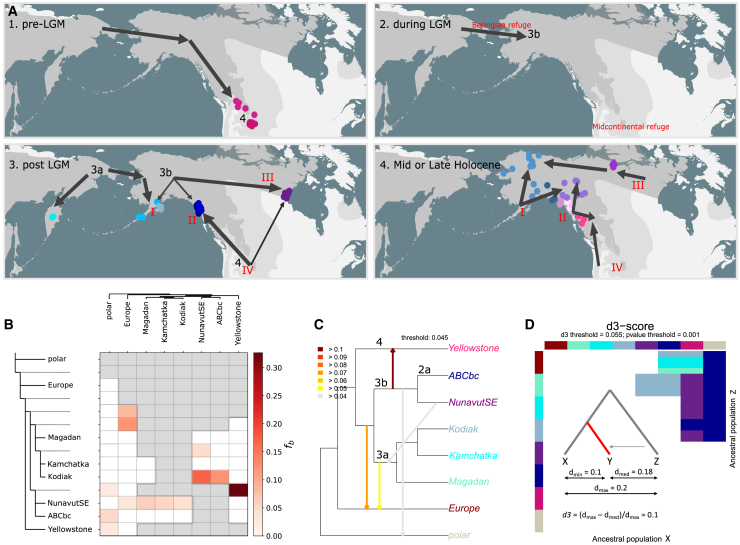

X chromosome data indicate that Canadian barren-ground grizzlies and ABC Islands bears are roughly equidistant to Yellowstone grizzlies and Kodiak bears, with their in-between genetic distances (0.079% ≤ Dxy ≤ 0.088%) being well below the distance between Yellowstone grizzlies and Kodiak bears (Dxy = 0.113%) (Figures 4B and 4C). This causes a violation of the triangle inequality condition (i.e., DAC ⩽̸ max(DAB, DBC)), a criterium for distances to be ultrametric. The violation of this criterium implies that the ancestors of ABC Island bears and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies were admixed between the Beringian and Midcontinental lineage. Given that this observation upholds for bears of the isolated Baranof and Chichagof Islands, this admixture must have occurred shortly after the LGM, prior to the flooding of the straits intersecting the ABC islands.

Since the genetic distances between the peripheral populations violate the triangle inequality condition, it is impossible to fit a binary tree model. Put differently, no bifurcating tree exists that provides a complete and accurate picture of the relationships between the four genetic clusters. When grouping ABC islands bears and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies with Kodiak bears, the binary model greatly overestimates the genetic distance of the former two relative to Yellowstone grizzlies, resulting in a strong gene flow signal (Figure 5). If, instead, grouping ABC islands and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies with Yellowstone grizzlies, D-statistics indicate the opposite, namely gene flow to or from Southwest Alaska bears. The same is observed when grouping Far Eastern Russian brown bears, particularly Kamchatka bears, with either European bears or Southwest Alaska bears.

Figure 5.

Gene flow analyses reveal that ABC Islands bears and Canadian barren-grounds grizzlies have a hybrid origin

(A) Hypothetical demographic scenario. Working hypothesis of the phylogeographical history of North American brown bears. Arrows are meant to represent rough phylogenetic relationships (not precise reconstructions of migration routes), with arrow thickness roughly representing admixture proportions. Roman letters indicate the four genetic clusters identified based on X chromosome data. The labels ‘3a', ‘3b' and ‘4' indicate mtDNA-haplogroups.

(B) ABBA-BABA analyses. D-statistics analyses performed with the software Dsuite. The reference topology is inferred from the X chromosome data using the UPGMA-algorithm, applicable to ultrametric data.

(C) Conflict in data. Dendrogram depicting conflict in data. The labels indicate mtDNA haplogroups. The arrows do not indicate gene flow events, but instead discrepancy in the data, where an outgroup lineage (arrow head) is genetically more similar to either of two ingroup sister lineages (arrow tail). Scores are calculated as: |d1– d2|/(½(d1+ d2)), in which d1 and d2 represent the absolute genetic distances between the outgroup and the sister lineages 1 and 2, respectively.

(D) d3-heatmap. Heatmap highlighting population triplets for which d3 > 0.055 (an arbitrary threshold). The d3-score is calculated as (dmax – dmed)/dmax, as depicted in the inset. The colors in the row and column bars represent populations X and Z, while field colors denote population Y. For instance, and as depicted in the third panel of Figure 5A, Canadian barren-ground grizzlies and ABC Islands bears are admixed between Yellowstone grizzlies of mtDNA-lineage 4 and Southwest Alaska bears of mtDNA lineage 3a. The p-values have been calculated using t-tests and indicate whether or not sequence dissimilaties of individual-level comparisons between populations X and Z differ significantly from those for populations Y and Z.

Whereas admixture proportions remain stable through time, the f3-score does not. Instead, the f3-score increases each generation, with the slope depending on effective population sizes, such that the signal of admixture gradually becomes lost over time.16 The population bottlenecks of ABC islands bears and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies thus obscured their f3-scores, but still did not entirely conceal the admixed origin of these bears. Among all triplets in which ABC Islands bears or barren-ground grizzlies are the hypothetical admixed populations, the lowest f3-scores are observed when the hypothetical donors are from Kodiak Island and Yellowstone, the populations representing the Beringian and Midcontinental lineage most faithfully (Tables S2 and S3). Likewise, if assuming two ancestral populations (K = 2), LEA ancestry analyses also indicate that the genomes of ABC Islands bears and Canadian barren-ground grizzlies contain genetic variation from both lineages (Figure 2C).

These admixture signals are consistent with various hypotheses. One of them is that North American brown bears survived the LGM in two glacial refugia, a Beringian and Midcontinental, resulting in a boreal and temperate lineage that interbred afterward, as inferred for various other species.61,62,63,64,65 We can only speculate about when, where, and how often the Beringian and Midcontinental lineages exactly met after the LGM, or about the contributions to this process by the now extinct lineage of grizzly bears, which used to occupy eastern North America.66,67,68 The recolonization of the deglaciated landscape of North America was a multi-phase process, characterized by range oscillations associated with climatic transitions between stadials and interstadials.69,70 These range shifts created ample opportunity for admixture between the Beringian and Midcontinental lineages at various time intervals throughout the Late Glacial.

Inferring admixture proportions is challenging because genetic distances between brown bear populations are affected by hybridization with polar bears. Consistent with previous studies,25,71 both the autosomal and X chromosome data confirm that all brown bears in Southeast Alaska contain high proportions of polar bear DNA, with the highest proportions found on the most likely location of the introgression event, the ABC Islands (Figure S18 and Table S2). The hybrid nature of ABC Islands bears is highlighted by their endemic mtDNA-haplogroup 2a, which is a sister clade of haplogroup 2b found within polar bears.14,72 The introgressed polar-bear genes in ABC Islands bears inflate their genetic distances to other brown bears, although perhaps to a lesser extent to Midcontinental bears in the lower 48 states, in case the latter captured polar-bear DNA in a separate hybridization event.25,73,74

Despite these uncertainties, a few key inferences can still be made. The distinctness of the four X chromosome clusters suggests continent-wide range fragmentation after the initial recolonization of the deglaciated landscape. This could imply that the local extinction event in Alaska in the Early Holocene, inferred from a conspicuous gap in the fossil record,31 was in fact part of a larger event that affected grizzly bear populations across the continent, possibly somehow related to the Late Pleistocene Mass extinction event. This postglacial range fragmentation allowed the newly created, admixed lineages II and III, to freely differentiate by means of genetic drift, unimpeded by gene flow.

The X chromosome dataset also suggests that during the subsequent and final recolonization event, which possibly occurred not earlier than the Mid- or even Late Holocene, bears of Southeast Alaska (cluster II) found a way to disperse out of the coastal region. Bears that dispersed in the southeast direction encountered bears that migrated out of the stronghold of southern cluster IV, while bears dispersing in the northeast direction encountered bears migrating out of the strongholds of clusters I and III. Further to the north, Alaska was predominantly recolonized from the refuge in Southwest Alaska (cluster I), whereas the Canadian barren-grounds were either permanently occupied or recently recolonized from an unknown location by bears of cluster III (Figure 5A).

Whereas a previous microsatellite study indicated an isolation-by-distance trend along the northern edge of the species range,43 the genomic data revealed a subtle genomic discontinuity which coincides with the Mackenzie River delta (separating “YukonNorth” and “NWTnorth”) (Figures 4 and S10), suggesting that the western range limit of pure Canadian barren-ground grizzlies of cluster III is roughly delineated by this coastal wetland.

Congruence between Y chromosome and mtDNA phylogeography

The existence of four distinct X chromosome genetic clusters of North American brown bears is largely consistent with ancient-mtDNA analyses, which previously revealed that brown bears colonized the North American continent through multiple migration waves coming from Far East Russia.31 The descendants of an early migration wave, carrying mtDNA-clade 4, are now found in the lower 48 states (cluster IV), while the descendants of the most recent migration wave, carrying mtDNA-haplotype 3a, currently reside in Alaska (cluster I) (Figure S19).

As detailed previously, our genomic analyses suggest that the descendants of the penultimate migration wave, which commenced during the LGM and introduced mtDNA-haplogroup 3b to the continent, split after the LGM in two lineages: a coastal lineage (cluster II) and a barren-ground lineage (cluster III) (Figure S10). The shared ancestry of cluster II and III is not evident from mtDNA, because the coastal lineage introgressed with polar bears.71,72 In contrast, the shared ancestry can still be read from the geographical distribution of Y chromosome haplotypes (Figure 6). Brown bears throughout Canada and Southeast Alaska, including the ABC islands, all belong to the same Y chromosome haplogroup, which we labeled “Canada”.

Figure 6.

Close correspondence between geographic ranges of Y chromosome and mtDNA haplogroups

(A) Rooted Y chromosome (i.e., single-locus) maximum-likelihood phylogeny, generated with the software IQtree. The phylogeny has been linearized using the mean path length method, and branch lengths have been converted in rough TMRCA-estimates, which however are very sensitive to mutation rate, which here was assumed to be 0.8 × 10−9 per site per year. Light blue bars indicate confidence intervals of the node ages. The color bar on the righthand side highlights clades with an origin before the LGM, and have been named here after their present-day geographical center of gravities. The tip color coding (sample names) corresponds to population assignment as in Figure 1. The gray rectangle labeled LGM indicates the Last Glacial Maximum, during which the ice-free corridor between the Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets is thought to be closed. Not included are the samples of NWTnorth and YukonNorth.

(B) Geographical distribution of Y chromosome haplotypes. Geographical map showing the distribution of Y chromosome clades (as defined in A). Solid black lines indicate mtDNA discontinuities. The color coding represents Y chromosome haplogroups, as in A. Note that the ranges between Y chromosome haplogroups correspond to those of mtDNA-haplogroups, although the borders are less abrupt, as expected in the case of male-mediated gene flow. Note also that genetic clusters II and III cannot be discerned from mtDNA and Y chromosome data, likely because these two clusters split too recently (i.e., due to incomplete lineage sorting and insufficient informative sites from novel mutations).

Apart from this gene flow derived incongruence, the geographic spread of Y chromosome haplotypes is strikingly similar to mtDNA phylogeographic patterns (Figures 6, S19, and S20), with the main discontinuities being located in Yukon Territories and southern British Columbia.15,30 Out of the 46 male brown bears in our dataset which are part of Y-haplogroup “Canada”, 41 carry either mtDNA-haplotype 2 or 3b. In contrast, of the 24 male brown bears of other Y chromosome haplogroups, only six carry mtDNA-haplotype 2 or 3b. A Fisher’s exact test on this contingency table returns a highly significant p value of 10−7, confirming a non-random overlap in geographical distributions of Y chromosome haplogroup “Canada” and that of mtDNA-haplotypes 2 and 3b. This correspondence has been facilitated by the low effective population sizes of mtDNA and Y chromosome haplotypes (1/4th of autosomal Ne), which allowed the stage of reciprocal monophyly to be approached relatively quickly for both markers.18

As expected in case of male-mediated gene flow, the geographical boundaries between Y chromosome haplogroups are less abrupt than those of mtDNA-haplogroups (Figure 6). The location of the mtDNA discontinuity in Yukon suggests that most of central Alaska has been recolonized from the genetic refuge in the Alaska Peninsula (cluster I), presumably during the Mid or Late Holocene. This is in agreement with the genetic similarity between central Alaska and Alaska Peninsula individuals inferred from autosomal and X chromosome data (Figures 1C and 1D). The co-occurrence of Y chromosome clades in interior Alaska (Figure 5) suggests incoming gene flow from the Canadian barren-ground grizzlies, explaining the admixture signals and the elevated levels of genetic diversity in this region (Figure 3, Figure 4, 4A, and 4B).75

The Y chromosomes of Admiralty Island bears cluster paraphyletically with mainland bears (Figure 6), which could reflect incomplete lineage sorting, but may also confirm earlier reports of male-mediated gene flow.8,76 In contrast, the monophyletic clustering of Y chromosome haplotypes from Baranof and Chichagof Islands (Figure 6) confirms that these insular bears have been isolated from the mainland as well as Admiralty Island.8 The coalescence time estimate of Y-haplotypes between Baranof and Chichagof Islands and mainland bears is more recent than the onset of the LGM (Figure 6). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the coast of Southeast Alaska, including the Alexander Archipelago, was recolonized in the Late Glacial, rather than sustaining a glacial refuge population throughout the LGM.31,32,63

The hypothesis that brown bears in the lower 48 states (mtDNA-haplogroup 4) descended from an early, pre-LGM migration wave, is supported by the presence of two endemic Y-haplogroups, clades “US1” and “US2” (Figure 5). These haplogroups coalesce with their sister clades further back in time than the closure of the Ice-Free corridor approximately 25 kya (Figure 5).77,78 One potential difficulty here is that, even when assuming a conservative mutation rate of 0.8 × 10−9 per site per year, one endemic clade (“US2”, predominate in Yellowstone), coalesces with haplotypes in Alaska approximately 30 kya (Figure 5), when eastern Beringia is thought to have been devoid of brown bears.31

Subspecies designations

In the evolutionary context of repeated fission and fusion of lineages, defining subspecies boundaries is inherently problematic, perhaps even futile. The debate around the subspecies delimitation of the grizzly bear11,12,13 is a logical consequence of the transient nature of genetic clusters within a species. Still, if taking the contemporary genetic structure as leading, the genetic data indicates that bears in Southwest Alaska, more specifically on Kodiak Island and the nearby Alaska Peninsula, are at present distinct from other North American brown bears, and are in fact genetically more similar to Kamchatka bears, on the Eurasian continent. These findings, which corroborate previous morphology-based inferences,12,13,17 indicate that the correct western range limit of the grizzly bear (U. a. horribilis) does not follow the coastline (i.e., Bering Strait and Shelikof Strait), as currently assumed, but instead is better described as a gradual, and eroding, transition zone which runs diagonally through Alaska.

Remarkably, major features of the population structure of North American brown bears, here inferred from terabytes of sequencing data, have been suggested as early as the 19th century, based on a handful of morphological traits. Comparing skull measurements of a few hundred individuals, Merriam17 realized that Kodiak bears, Alaska Peninsula bears and Kamchatka are closely related, and even roughly classified the remaining North American brown bears in the genetic clusters identified here.12 This correspondence between genetic and morphological data indicates that the genome-wide differences between genetic clusters, which are slowly eroding due to recent and ongoing gene flow, partly occur in functional regions and have a measurable effect on the phenotype.

Limitations of the study

The sequencing and genotype calling pipeline used in this study has an estimated combined error rate of ∼0.008% (1 per 12,500 sites),6 allowing sequence dissimilarity to be measured with a precision of ∼0.0001–0.0002 (Figure 3B). The genotype calling errors introduce noise, as seen in the blurred boundaries of distance matrices (Figure 1, Figure 4A and 4B) and the variation in distance estimates among pairs from the same populations (Figure 3B). This noise limits our ability to resolve recent population splits, especially in large populations where divergence is driven almost exclusively by novel mutations rather than by genetic drift. For example, with a mutation rate (μ) of 10−8 and an ancestral diversity (πanc) of 0.002, two populations diverging for 1,000 generations (≈10,000 years for brown bears) would differ by only 0.00002 (Dxy = πanc + 2μT = 0.00202). Assuming population size constancy, the difference between π and Dxy is too small to detect reliably using our genotype calling pipeline, and as a result individuals from the two populations would appear a single, panmictic cluster.

Similarly, for the Y chromosome, our genotype calling pipeline returned for the reference-genome sample (which clearly should not have any alternative genotype calls), 32 alternative calls out of 1035501 retained sites in total, suggestion an error rate of 32/(1035469 + 32) = 0.00003. Given the low mutation rate, the differences between Y chromosome haplotypes that split after the LGM are expected to be largely caused by genotyping errors rather than true mutations. For instance, assuming a mutation rate of 0.8·10−9, a TMRCA of 20.000 years, and a length of 1Mb (after filtering out low-quality sites), the expected number of differences is (106·20000·0.8·10−9) 16, half the expected number of genotype errors.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests should be directed to the lead contact, Menno de Jong (menno.de-jong@senckenberg.de).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Short-read sequencing data have been deposited to NCBI’s SRA repository and are publicly available as of the date of publication under NCBI bioproject-ID: PRJNA1139383. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources tables as well as Table S1. Scripts used for read mapping and genotype calling, for heterozygosity and distance calculations, and subsequent population-genetic analyses using SambaR, are available from github: https://github.com/mennodejong1986/WGS_data_analyses.

The script for stepping stone model simulations is also available from github: https://github.com/mennodejong1986/SteppingStoneModels.

Scripts for multi-species coalescence (MSC) based analyses on haploblocks can be found at: https://github.com/mennodejong1986/PopMSC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Clayton Apps, Steve Baryluk, Jeremy Caron, Matthew Cronin, Faye d’Eon-Eggertson, Kerry Gunther, Mark Haroldson, Frank van Manen, David Paetkau, Matthew Pollard, Jodie Pongracz, and Abbey Wilson for the acquisition and provision of samples. We also acknowledge all associated organizations (see Table S1), namely Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G), the Government of the Northwest Territories, the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST), the Nunavut Department of Environment (GN-ENV), Wildlife Genetics International, and the Yukon Department of Environment. We thank David Paetkau for comments on a previous draft of the ms. We acknowledge the invaluable support of Nunavut communities in helping collect the bear samples from Nunavut. This sampling work was supported by the Government of Nunavut, Hunters and trappers association of Arviat and Kugluktuk, the Canada Research Chair to NL, and Université de Moncton. This work was supported by the Leibniz Association and Hesse’s funding program LOEWE. We also thank Jon Balder Hlíðberg (www.fauna.is) for the artwork (brown bear drawing).

Author contributions

M.J.d.J. and A.J. conceived the study. M.J.d.J. performed data analyses and simulations and wrote the manuscript. M.A., N.L., E.E.P., and A.P.C. provided samples. All authors discussed the analysis outcomes and revised the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| AlaskaSE1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772220 |

| AlaskaSE10 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772228 |

| AlaskaSE11 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772229 |

| AlaskaSE12 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772230 |

| AlaskaSE13 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772231 |

| AlaskaSE14 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772232 |

| AlaskaSE2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772221 |

| AlaskaSE3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772222 |

| AlaskaSE4 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772223 |

| AlaskaSE5 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772224 |

| AlaskaSE6 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772225 |

| AlaskaSE8 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772226 |

| AlaskaSE9 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772227 |

| Canada16 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772233 |

| Canada17 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772234 |

| Nunavut1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772248 |

| Nunavut2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772249 |

| Nunavut3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772250 |

| Nunavut4 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772251 |

| Nunavut5 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772252 |

| Nunavut6 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772253 |

| Yellowstone1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772244 |

| Yellowstone2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772245 |

| Yellowstone3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772246 |

| Yellowstone4 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772247 |

| Yukon1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772235 |

| Yukon2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772236 |

| Yukon3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772237 |

| Yukon4 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772238 |

| Yukon5 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772239 |

| Yukon6 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772240 |

| Yukon7 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772241 |

| Yukon8 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772242 |

| Yukon9 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN42772243 |

| YukonNorth1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324017 |

| YukonNorth2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324018 |

| YukonNorth3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324019 |

| NWT1 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324014 |

| NWT2 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324015 |

| NWT3 | NCBI SRA | SRA: SAMN48324016 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Scripts for read mapping, genotype calling, and distance calculations | This study | https://github.com/mennodejong1986/WGS_data_analyses |

| Scripts for genetic simulations (stepping stone models) | This study | https://github.com/mennodejong1986/SteppingStoneModels |

| Scripts for multi-species coalescent based analyses | This study | https://github.com/mennodejong1986/PopMSC |

| Fastp | Chen et al.79 | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp |

| BWA mem | Li and Durbin80 | https://github.com/lh3/bwa |

| Samtools 1-20 | Li et al.81 | https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| Picard | De Pristo et al.82 | https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| Bcftools 1-20 | Li83 | https://github.com/samtools/bcftools |

| Vcftools | Danecek84 | https://vcftools.github.io/index.html |

| Plink 1.9 | Purcell et al.85, Chang et al.86 | https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/ |

| SambaR 1.10 | De Jong et al.87 | https://github.com/mennodejong1986/SambaR |

| Admixtools | Patterson et al.88 | https://github.com/DReichLab/AdmixTools |

| Dsuite | Malinsky et al.89 | https://github.com/millanek/Dsuite |

| Darwindow | De Jong et al.16 | https://github.com/mennodejong1986/Darwindow |

| LDblock | Dong et al.90 | https://github.com/BGI-shenzhen/LDBlockShow |

| Beagle | Browning et al.91 | https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/beagle.html |

| Astral | Mirarab et al.92 | https://github.com/smirarab/ASTRAL |

| IQtree | Nguyen et al.93 | https://iqtree.github.io/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

Sample collection

A total of 40 dried tissue samples or hair bundles (approximately 30 hairs per sample), including hair follicles, were obtained from 40 individuals of North American brown bear (Ursus arctos horribilis). Sample-specific information, including sex and geographical location, are detailed in Table S1. The samples were collected from deceased individuals or using hair traps. No animals have been killed for the purpose of this study. All samples from the United States were at the onset of the project in possession of Wildlife Genetics International (WGI) in Nelson, Canada, and sequenced, along with the Canadian samples, at Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre in Vancouver, Canada.

We selected primarily male individuals, in order to include information about the Y chromosome and therewith male migration behaviour. Because males carry only one copy of the X chromosome whereas females carry two, the mean X-chromosomal sequencing depth for males was half that of females, leading to a slight effect of sex on the accuracy of genotype calling for this particular chromosome (Figure S21).

Method details

Sequencing

The study includes data for 108 North American brown bear individuals (Table S1). Of those, the data of 40 individuals have been newly generated for this study. DNA was isolated using standard extraction protocols (i.e., Qiagen DNA tissue kit), either from tissue or from hair samples. We sequenced all samples at a mean depth of 10x using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Library preparation (PCR-free, 350 bp fragments) was performed at the sequencing facility.

Read mapping and genotype calling

Read quality check was performed using the software FastQC and MultiQC.94 Reads were filtered using the software fastp,80 with the following options: ‘cut_tail, cut_tail_window_size 4, cut_tail_mean_quality 20, qualified_quality_phred 15, unqualified_percent_limit 40, n_base_limit 5, length_required 36, low_complexity_filter, correction, overrepresentation analysis’.

Reads were mapped, using the software BWA mem,80 against a male grizzly bear reference genome with chromosome-level resolution (ASM358476v1_HiC),95,96 as well as to a full brown bear mitochondrial sequence (NC_003427.1). Samtools81 was used to remove reads with a mapping quality below 20 and/or alignment scores below 100, as well as reads that mapped discordantly or to multiple locations in the genome. Read duplicates were removed using the software picard.82

Genotype likelihoods and calls were generated using the bcftools mpileup and call pipeline.83 When calling genotypes from genotype likelihoods (bcftools calls), the ploidy-level was set according to genome type (i.e., mtDNA, autosomal and sex chromosome) and sample sex. For samples with missing sex information, the sex was inferred from Y-chromosomal mapping rates. Indels were normalized and realigned using ‘bcftools norm’.

When calling genotypes from genotype likelihoods (bcftools call), we used the ‘group-samples’ option to assign each individual to its unique group (i.e., we disabled the option of influencing genotype calls based on information from other samples). Admittedly, this approach has a higher genotype call error rate in the case of single, panmictic populations.97 However, we established experimentally, through the comparison of heterozygosity scores, that this approach yields the most unbiased results for datasets which contain an uneven number of samples from highly divergent populations.16 In addition, because our approach does not make a priori assumptions about population assignment, the results are reproducible regardless of the sample set.

The bcftools filter pipeline was used to mask sites with a read depth below five, after establishing experimentally this provided a balance between disposal of useful data and incorrect heterozygosity estimation.16 For the autosomal dataset, we retained sites with a total read depth between 550 and 2100 for all individuals combined. Pseudo-autosomal regions were identified based on deviations of sequencing depth relative to chromosome-wide means, and subsequently excluded from the X-chromosomal and Y-chromosomal datasets.

Population structure analyses were run on a dataset from which sites with a site quality below 15 were removed, using the command ‘bcftools view -i ‘QUAL>=15’, to correct the genetic distances involving a few low-quality samples (‘NWTnorth’ and ‘YukonNorth’) (Figures S22 and S23). However, because a site quality filter causes an undesired correlation between genetic distance and proportion of missing data (Figures S22 and S23), Dxy, He and π values were estimated from an unfiltered dataset (i.e., ‘bcftools view -i ‘QUAL>=0’).

Genome-wide statistics (DXY, π, FST, He, FROH)

The total number of retained homozygous and heterozygous sites per sample were counted on a sliding-window basis, using non-overlapping windows with a fixed size of 20 kb. The counting was performed using the ‘Darwindow’ pipeline,16 which depends on the software Tabix98 for the extraction of genomic regions, and which subsequently converts the count data into estimates of observed heterozygosity (He) and run-of-homozygosity content (FROH) using R functions.16 Based on visual examination of the sensitivity of ROH-analyses to various settings, ROHs were defined as continuous regions of at least 200 kb (i.e., ≥10 adjacent windows of 20kb) with an average He value below 0.05%.

Expected sequence dissimilarity estimates, E(p),33 for each pair of individuals were also estimated using custom-built Unix and R scripts. For sites of haploid datasets (mtDNA and Y chromosome), E(p) = 0 for A:A and E(p) = 1 for A:T. For sites of diploid datasets, E(p) = 0 for AA:AA; E(p) = 0.5 for AT:TT and AT:AT; E(p) = 0.75 for AT:CT; and E(p) = 1 for AA:TT and AT:CG.99 For sites of haplodiploid comparisons (e.g., X-chromosome of a male versus female individual), p = 0 for A:AA; p = 0.5 for A:AT; p = 1 for A:TT.

In theory, these calculations directly produce comparable outcomes regardless of ploidy (Figure S21). Differences in sequencing depth between sexes (e.g., males have less coverage for their X chromosome than females) only introduce a negligible bias (Figure S21). For practical reasons, autosomal and X-chromosomal E(p) estimates were calculated over randomly thinned datasets rather than the full dataset. Sites with missing data for one or both individuals involved in the pairwise comparison were excluded.

The resulting matrices of uncorrected genetic distances between individuals were used as input for both non-hierarchical analyses (i.e., principal coordinate analyses, or PCoA) and hierarchical cluster analyses (i.e., biological neighbor-joining, bioNJ, and ordinary least squares, OLS), by running the functions ‘pcoa’, ‘bionj’ and ‘fastme.OLS’ of the R package ape-5.3.100 Because of the generally low variation in genetic distances across pairs of individuals, we opted to depict these multi-locus distance-based phylogenies in the unrooted format, as this format accentuates basal splits. Roots were added manually, assuming either American black bears or alternatively European brown bears to be the most distant outgroup.

Following Cavalli-Sforza and Piazza,34 we compared the path lengths between all sample pairs in the X-chromosomal and autosomal bioNJ-phylogenies with the actual genetic distances in the distance matrix. We reasoned that a difference between genetic distance and path length might indicate a violation of the assumption of a strictly bifurcating tree. Admixture events, which cause a node to have more than one parental node, will result in two lineages having lower or higher genetic distances than suggested by the path length in the tree.

For each population, nucleotide diversity (π) values were derived from the E(p)-estimates, namely as the mean of all possible sample comparisons within a population. Similarly, population pairwise DXY values were also derived as the mean of all possible sample pairwise comparisons between two populations. Relative distances between populations were estimated using the formula: FST = (DXY–π)/DXY.101

Multispecies coalescent analyses

Following De Jong et al.16 multispecies coalescent based analyses were performed on a dataset of 1086 highly variable haploblocks. These haploblocks were detected using Plink (–blocks option), with the options ‘block-max-kb’ and ‘blocks-min-maf’ set to 1500 and 0.2, respectively. Linkage disequilibrium estimates within and between haploblocks were visually inspected using the software LDBlockShow.90 The rationale behind dividing the genome into haploblocks is to meet the assumption underlying MSC-based analyses: no recombination within loci, and no linkage between loci. The rationale behind selecting haploblocks with a certain minimum length and/or number of variable sites is to obtain sufficient phylogenetic signal per locus.

Haploblocks were extracted from the vcf-file using bcftools view, and subsequently phased with the software Beagle version 5.4,91 using default settings, resulting in a dataset of (113∗2=) 226 haplotypes. For all 1086 haploblocks, matrices of uncorrected genetic distances between all (113∗112)/2 = 6328 haplotype pairs were generated using custom-built Unix and R scripts, from which bioNJ trees were inferred using the function ‘bionj’ of the R-package ape. From these 1086 unrooted haploblock trees, a supertree was computed using the software Astral 5.7.8,92 with each haplotype mapped to its respective population.

Y chromosome and mitogenome phylogeny

Dendrograms of Y chromosome and mitogenome haplotypes were generated with the software IQtree,93 using default settings and using all available sites (monomorphic and polymorphic) and linearized using the function ‘chronoMPL’ of the R package ‘ape’, which implements the mean path length method.102 Y-chromosomal genetic distance estimates were converted into split time estimates (which may serve as upper limits of population splits) assuming a mutation rate of 0.8·10-9 per site per year.103

Admixture analyses

To leverage all available information, we strived to perform analyses on the full genome-wide dataset, comprising both monomorphic and polymorphic sites. An exception was made for admixture analyses, for which we used available software that required an input dataset containing variable sites only, and/or were constrained by data size limitations. For such analyses, we extracted a subset of biallelic sites by filtering on levels of missing data (max 5% allowed), and by subsequently thinning the dataset using vcftools.84 We thinned the autosomal data by selecting one SNP for every 10 kb, and the X-chromosomal data by selecting one SNP every 2 kb, retaining for each dataset ∼45K biallelic SNPs. To facilitate downstream data analyses, the X-chromosomal haplodiploid dataset was converted into a diploid dataset.

Plink version 1.90b.2085,86 was used to convert the SNP data from VCF format into PED/RAW and MAP/BIM (using the flags make-bed, recode A, chr-set 95, and allow-extra-chr). SNP data management and analyses were performed in R-4.2.0, using wrapper functions of the R package SambaR.87 The data were imported into R and stored in a genlight object using the function ‘read.PLINK' of the R package adegenet-2.1.1.104 The autosomal data set was filtered using the function ‘filterdata’ of the R package SambaR, with indmiss=0.25, snpmiss=0.2, min_mac=2, and dohefilter=TRUE.

We used four methods to detect gene flow. First, ancestry coefficients were calculated from the autosomal SNP dataset using the R package LEA-2.8.0,105 more particularly the functions ‘snmf’ and ‘Q’, with alpha set to 10, tolerance to 0.00001, and a number of iterations to 200. The optimal number of clusters (K) was determined with the elbow method on cross-entropy scores generated for K=2 to K=12 (with 50 independent runs each), with the assumption that the optimal K coincides with the starting point of a plateau.

Second, f3-statistics were generated with the software Admixtools.88 An advantage of the f3-statistic is that admixture signals can be reliably inferred without an established phylogeny. The f3-statistic is defined as (a-b)·(a-c), in which a, b and c represent vectors with the allele frequencies in the putatively admixed population A and the two putative donor populations B and C respectively. If, and only if, a is intermediate between b and c, will the product ‘(a-b)(a-c)’ be negative. While the f3-score has been designed to detect admixture, in theory a negative f3-score may also indicate a scenario in which a large source population buds of two smaller sister populations, in which genetic drift causes allele frequencies to randomly drift in opposite directions. Another downside of the f3-statistic is that the signal decays over time, with the f3-statistic increasing each generation by 1/(4Nemean), in which Nemean refers to the average effective population size of the three populations.16 Therefore, for populations with low genetic diversity we considered which triplets returned the lowest f3-score (even if highly positive).

Third, we used the software Dsuite89 to calculate D-statistics on input data of autosomal SNPs. The reference phylogeny was obtained by applying the UPGMA-method to a distance matrix of DXY-values obtained from X-chromosomal data. Assuming male-mediated gene flow, X-chromosomal data longer retains signals of a former population structure, and hence is better suited to derive the original phylogeny compared to autosomal data. Given that the underlying matrix was nearly ultrametric (as expected for multi-locus genetic distances), the UPGMA-algorithm allowed us to infer a rooted phylogeny without compromising accuracy (as also suggested by comparison to a bioNJ phylogeny). For the D-statistics calculations, we only included populations that based on f3-analyses were relatively unaffected by recent gene flow events.

Fourth, we calculated for each population triplet a measure which we denote as the d3-score, and which we calculate as (dmax – dmed)/dmax. In here, dmax is the largest of the three pairwise Dxy-estimates, and dmed the second largest. In the absence of gene flow, and in the absence of mutation rate heterogeneity across lineage, d3 is expected to equal zero. The method is conceptually similar to the Three Sample Test for introgression known as the D3-test.106

Stepping stone model simulations

The expected population structure given a migration-drift equilibrium in case of isolation-by-distance (IBD) was simulated using a stepping-stone model in R, after Slatkin (1991).40 The stepping-stone models were either one-dimensional (linear or circular) or two-dimensional (square, rectangular or torus), with uniform migration rates between direct neighbour demes, and with various deme numbers.

All simulations were run assuming 1000 generations following initial panmixia, with for each deme an effective population size (Ne) of 500 diploid individuals, a migration rate (m) of 0.025, and 10000 biallelic loci with an initial minor allele frequency of 0.5. The migration rate denotes here the proportion of breeders within a deme that immigrated during the last generation from a neighbouring deme, and hence the migration rates per neighbour equals m/2 and m/4 for 1-dimensional and 2-dimensional stepping stone models, respectively. For island populations, the migration rate was set to zero. PCoA-plots were generated based on Euclidean distances between individuals, with three individuals per deme.

Quantification and statistical analysis

We used t-tests to evaluated whether differences between populations outweigh uncertainty introduced by sequencing and genotyping errors. More particularly, we tested whether Dxy-values of a certain population pair significantly differs from the Dxy-value other population pairs (Figure S6B). The test requires multiple individuals per population, and each individual should be a fully independent replicate of its respective population. To that end, we removed related individuals, and performed genotype calling per individual, thus without considering data of other individuals, by assigning each individual to a unique group using the –group-samples flag of bcftools call. The t-tests were performed using the R base function t.test.

We also tested, for each population pair for correlations between proportion of missing data and sequence dissimilarity, treating each pair of individual is an independent data point (Figure S11). These tests were performed using the R base function cor.test(method=‘Pearson’).

Published: July 2, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112870.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Millien V. Morphological Evolution Is Accelerated among Island Mammals. PLoS Biol. 2006;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw K.L., Gillespie R.G. Comparative phylogeography of oceanic archipelagos: Hotspots for inferences of evolutionary process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7986–7993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601078113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Ramos G., Kirkpatrick M. Genetic Models of Adaptation and Gene Flow in Peripheral Populations. Evolution. 1997;51:21–28. doi: 10.2307/2410956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster P., Toth A. Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9079–9084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331158100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gojobori J., Arakawa N., Xiaokaiti X., Matsumoto Y., Matsumura S., Hongo H., Ishiguro N., Terai Y. Japanese wolves are most closely related to dogs and share DNA with East Eurasian dogs. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:1680. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jong M.J., Anaya G., Niamir A., Pérez-González J., Broggini C., del Pozo A.M., Nebenfuehr M., de la Peña E., Ruiz-Olmo J., Seoane J.M., et al. Red Deer Resequencing Reveals the Importance of Sex Chromosomes for Reconstructing Late Quaternary Events. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2025;42 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaf031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paetkau D., Waits L.P., Clarkson P.L., Craighead L., Vyse E., Ward R., Strobeck C. Variation in Genetic Diversity across the Range of North American Brown Bears. Conserv. Biol. 1998;12:418–429. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paetkau D., Shields G.F., Strobeck C. Gene flow between insular, coastal and interior populations of brown bears in Alaska. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:1283–1292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller C.R., Waits L.P., Joyce P. Phylogeography and mitochondrial diversity of extirpated brown bear (Ursus arctos) populations in the contiguous United States and Mexico. Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:4477–4485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLennan, B.N., Proctor, M.F., Huber, D., and Michel, S. (2017). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- 11.Merriam C.H. Review of the grizzly and big brown bears of North America (genus Ursus) with description of a new genus. Vetularctos. North Amer. Fauna. 1918;41:1–136. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall E.R. Vol. 13. University of Kansas Publications. Museum of Natural History; 1984. Geographic Variation Among Brown and Grizzly Bears (Ursus arctos) in North America; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rausch R.L. Geographic variation in size in north american brown bears, ursus arctos l., as indicated by condylobasal length. Can. J. Zool. 1963;41:33–45. doi: 10.1139/z63-005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin M.A., Amstrup S.C., Garner G.W., Vyse E.R. Interspecific and intraspecific mitochondrial DNA variation in North American Bears (Ursus) Can. J. Zool. 1991;69:2985–2992. doi: 10.1139/z91-421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waits L.P., Talbot S.L., Ward R.H., Shields G.F. Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeography of the North American Brown Bear and Implications for Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1998;12:408–417. doi: 10.1111/J.1523-1739.1998.96351.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jong M.J., Niamir A., Wolf M., Kitchener A.C., Lecomte N., Seryodkin I.V., Fain S.R., Hagen S.B., Saarma U., Janke A. Range-wide whole-genome resequencing of the brown bear reveals drivers of intraspecies divergence. Commun. Biol. 2023;6:153. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04514-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merriam C.H. Preliminary synopsis of the American bears. Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington. 1896;10:65–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avise J.C. Mitochondrial DNA and the evolutionary genetics of higher animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1986;312:325–342. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pamilo P., Nei M. Relationships between gene trees and species trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1988;5:568–583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronin M.A. My Experience: Mitochondrial DNA in Wildlife Taxonomy and Conservation Biology: Cautionary Notes. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1993;21:339–348. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mountain J.L., Cavalli-Sforza L.L. Multilocus genotypes, a tree of individuals, and human evolutionary history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:705–718. doi: 10.1086/515510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]