Abstract

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) remains a major clinical challenge due to its high mortality and propensity for immune escape, which critically limits the efficacy of immunotherapy. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) is a key factor restricting the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in GC. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activating protein (NKAP), a conserved regulator of the NF-κB pathway, has been shown to drive immune evasion in other cancer types by modulating cytokine networks and immune cell functions. However, the specific role and mechanisms of NKAP in shaping the immunosuppressive TME of GC and contributing to resistance against programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade therapy remain largely unexplored. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the role of NKAP in the GC TME and elucidate its mechanisms in driving immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-L1 therapy.

Methods

We analyzed datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) datasets and clinical specimens from patients with GC who received neoadjuvant therapy with PD-L1 inhibitors to evaluate NKAP expression and its association with clinicopathological features. In vitro models of mature dendritic cells (mDCs) and murine xenografts were used to investigate the mechanism underlying NKAP’s involvement. NF-κB pathway activation, interleukin-10 (IL-10) secretion, and regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation were assessed via luciferase assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and flow cytometry. Changes in the TME and the therapeutic efficacy of PD-L1 blockade were evaluated in xenograft models.

Results

Elevated NKAP expression correlated with advanced tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor tumor differentiation in patients with GC. High NKAP levels predicted higher residual tumor burden post-PD-L1 therapy. Mechanistically, NKAP overexpression activated the NF-κB pathway in mDCs, driving IL-10 secretion and promoting naïve T-cell differentiation into immunosuppressive Tregs. This process fostered an immunosuppressive TME, which diminished the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in murine models.

Conclusions

NKAP is a critical regulator of GC immune escape, linking NF-κB–driven IL-10 production in mDCs to Treg-mediated immunosuppression during anti–PD-L1 therapy. Targeting NKAP may reverse resistance to ICIs, offering a promising strategy for improving clinical outcomes in patients with GC.

Keywords: Nuclear factor kappa B activating protein (NKAP), gastric cancer (GC), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), interleukin-10 (IL-10), immune escape

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activating protein (NKAP) correlates with aggressive tumor behavior and poor response to programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors in gastric cancer (GC). The NKAP-NF-κB-interleukin (IL)-10 axis drives regulatory T-cell (Treg) expansion and immunosuppression.

What is known and what is new?

• GC has an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that limits immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) efficacy. NKAP drives immune evasion in other cancers via NF-κB-mediated cytokine/immune cell regulation. Programmed death receptor-1/PD-L1 inhibitors reactivate T cells but show variable efficacy in GC.

• This study was the first to identify NKAP as a key driver of ICI resistance in GC and offers actionable strategies to improve immunotherapy outcomes. NKAP inhibition could be combined with other immunotherapies to enhance efficacy.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Targeting NKAP may reverse immunosuppression and exert a synergistic effect when combined with ICIs. The mature dendritic cell-IL-10-Treg axis may be a druggable pathway for overcoming GC immunotherapy resistance. The NKAP should be validated in studies on patients with GC to guide ICI selection, the combination of NKAP inhibitors (e.g., small interfering RNA/small molecules) with ICIs should be examined, and clinical trials on the targeting of NKAP-NF-κB-IL-10 axis in ICI-resistant GC should be conducted.

Introduction

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is the complex biological milieu surrounding tumor cells and substantially influences their growth and progression. It includes multiple cellular and extracellular components, including blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts, bone marrow-derived inflammatory cells, an array of signaling molecules, and the extracellular matrix (ECM) (1). The TME plays a pivotal role in tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic response. The interaction between tumor cells and the TME is analogous to the “seed-and-soil” hypothesis, wherein tumor cells release signaling molecules that remodel the surrounding microenvironment, facilitating angiogenesis and promoting immune tolerance (2). Moreover, immune cells within the TME can significantly impact the growth, survival, and invasive capacity of cancer cells (3). In recent years, as research on the mechanisms related to the TME’s role in tumor progression has deepened, the focus has expanded beyond tumor cells themselves to include the TME and tumor stroma as potential therapeutic targets. This shift has driven the discovery and application of TME-targeting biomarkers, positioning the TME as a cutting-edge area in modern cancer research.

Tumor immunotherapy activates the body’s immune system to elicit tumor-specific immune responses, inhibiting and eliminating tumor cells. This approach offers high specificity and low toxicity, making it a pivotal strategy in cancer treatment. Among these therapies, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) restore T-cell immune function by blocking inhibitory signals such as programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) and its ligand, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) (4,5). They have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in various malignancies, including renal cell carcinoma (6), melanoma (7), and non-small cell lung cancer (8). Aberrant activation of the PD-1-PD-L1 axis in the TME can suppress antigen presentation, weaken T-cell function, and promote immune evasion, suggesting it as a pivotal therapeutic target (9). ICIs targeting PD-1/PD-L1 have received clinical approval and are widely used in treating multiple malignancies, advancing the field of cancer immunotherapy (10).

NF-κB activating protein (NKAP) is a highly conserved protein involved in various biological processes, including transcriptional repression, immune cell development and maturation, T-cell functional acquisition, and maintenance of hematopoiesis (11-13). NKAP is considered a positive regulator of the NF-κB signaling pathway and promotes the initiation and progression of various cancers (11). A study has shown that NKAP is significantly upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues, with its high expression associated with poor prognosis and reduced survival rates in patients with HCC (14). Additionally, in glioma cell models, silencing NKAP markedly inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, whereas its overexpression enhances invasive capabilities (15). NKAP can also modulate the secretion of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), influencing the polarization and infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), thereby shaping the tumor immune microenvironment and potentially affecting the tumor’s response to immunotherapy. Other research indicates that the oncogenic effects of NKAP are partially dependent on the Notch1 signaling pathway (13), offering a new perspective for exploring potential therapeutic targets in malignancies.

Although the role of NKAP in various tumors has been gradually elucidated, its function and molecular mechanisms in gastric cancer (GC) remain unclear, with limited research available. Given the immunosuppressive characteristics of the GC microenvironment and the clinical prospects of immunotherapy, the role of NKAP in the immunoregulation of GC warrants in-depth investigation. NKAP may influence immune cell infiltration, the expression of immune checkpoint molecules, and activation of immune signaling pathways, thereby modulating the sensitivity of GC to immunotherapy. Therefore, further elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of NKAP’s effect in the GC immune microenvironment can help clarify its value as a immunotherapeutic target and provide novel theoretical foundations for immunotherapeutic strategies in GC. We present this article in accordance with the ARRIVE and MDAR reporting checklists (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2025-491/rc).

Methods

Patients and clinical data

A total of 30 patients with GC were initially screened for this study. In one of these patients, the treatment regimen had to be adjusted due to complications during neoadjuvant therapy, and another patient did not undergo surgery due to a lack of pathological non-response (pNR). Ultimately, 28 patients who completed the planned treatment and underwent radical surgery were included in the study. All patients received immuno-neoadjuvant therapy at the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University between July 2023 and September 2024. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University (approval No. HDFYLL-KY-2023-093) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Patients received a neoadjuvant therapy regimen based on the PD-L1 inhibitor pembrolizumab combined with cisplatin. Specifically, pembrolizumab was administered intravenously at a dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks, and cisplatin was administered at 75 mg/m2 intravenously every 3 weeks. Both drugs were administered on the first day of each treatment cycle. Approximately 4 to 6 weeks after completing the final neoadjuvant treatment, patients underwent radical surgery.

Postoperative pathologic evaluation indicated that 8 (27.59%) patients achieved immune major pathologic response (iMPR), 21 (72.41%) of whom achieved immune pathologic partial response (iPR), while 1 (3.45%) patient had immune pathologic non-response (iNR).

Identification of the tumor bed

The primary objective of radiological tumor bed identification is to assess the response of GC lesions to immuno-neoadjuvant therapy. Based on previous research (16), this study compared the maximum lesion diameter measured by posttreatment computed tomography (CT) scans with the corresponding tumor mass maximum diameter measured during the gross examination of surgical specimens, the purpose of which was to evaluate the efficacy of radiological assessments in determining the therapeutic effects of immuno-neoadjuvant therapy.

Clinical and pathological response evaluation

Immune-related residual viable tumor (irRVT) was used to assess the proportion of viable tumor within the total tumor bed, which consists of the sum of regressed tumor bed, residual tumor, and necrotic tissue (17). Based on irRVT, pathological response grades were classified as follows: immune pathological complete response (iCR; 0% irRVT), immune major pathological response (iMPR; ≤10% irRVT), immune pathological partial response (iPR; >10% and <90% irRVT), and iNR (≥90% irRVT).

Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data

RNA-sequencing data (level 3) and corresponding clinical information were obtained from TCGA dataset (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), encompassing 415 GC cases and 34 normal tissues. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired t-tests were employed for statistical analyses. Chi-squared tests or Fisher exact tests were applied to assess the association between NKAP expression and clinical characteristics.

Cell culture

The human GC cell lines AGS, SNU-16, NCI-N87, SGC-7901, and MGC-803 used in this study were all purchased from the National Infrastructure of Cell line Resources (Beijing, China). Cell cultures were maintained in RPMI-1640 complete medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% antibiotics (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cells were incubated at 37 ℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere to maintain their growth and physiological state.

Immunofluorescence and biomarker evaluation

Immunofluorescence staining was performed with a SignalStain Boost IHC detection kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval with Dako target retrieval solution (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 10% goat serum, followed by overnight incubation at 4 ℃ with an anti-NKAP antibody (PA5-51484; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The next day, after washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (ab150077; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to facilitate cellular localization. Finally, the samples were mounted with an antifade mounting medium and visualized under a laser confocal microscope to capture fluorescence signals. All experiments were conducted under identical conditions to ensure data reliability and comparability.

To evaluate PD-L1 expression levels, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was performed on tumor tissue samples obtained from pretreatment endoscopic biopsies. PD-L1 staining was carried out via PD-L1 IHC SP263 assay (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s standardized protocol. The staining procedure was conducted on the Dako ASL48 platform (Agilent) for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues (18). PD-L1 expression was quantified according to the combined positive score (CPS), which was as the total number of PD-L1-stained tumor and immune cells divided by the total number of viable tumor cells, multiplied by 100. To ensure scoring accuracy and consistency, all samples were independently evaluated by two pathologists in a blinded manner.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from clinically obtained GC tissues or cell cultures with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. The proteins were separated via 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween20 (TBST) for 10 minutes and then blocked at room temperature for 1 hour with TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Overnight incubation with primary antibodies was performed, including with anti-NKAP, anti-IL10 (ab133575, Abcam, Shanghai, China), anti-NF-κB (ab207297, Abcam, Shanghai, China), anti-P65 (ab239882, Abcam, Shanghai, China), and anti-β-actin (ab179467, Abcam, Shanghai, China). The membrane was then incubated for 1 hour in 5% skim milk containing horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:50,000; ab150077, Abcam, Shanghai, China). Protein signals were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) and quantified via densitometric analysis with ImageJ software [National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA]. The relative protein expression levels were normalized to β-actin and expressed as a percentage of protein/β-actin. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and reliability.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted and subsequently reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with GoScript Reverse Transcription Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time qPCR was performed with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The reaction system and cycling conditions were set according to the reagent kit instructions, and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1. qPCR data were analyzed with the 2−ΔΔCt method, with β-actin serving as the internal control. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure data reliability.

Table 1. Sequences of primers.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| NKAP | ATCACTCAGAGCATAATGTAAT | AATAATCACTTGTTCCTACCTT |

| IL-10 | GTGGAGCAGGTGAAGAAT | TCTATGTAGTTGATGAAGATGTC |

| FOXP3 | GCTCGCACAGATTACTTCAG | GTTGAGTGAGGGACAGGAT |

| CD25 | CAGGAACAGAAGGATGAATGA | CCAATTAGTAACGCACAGGTA |

| β-actin | GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT | CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT |

Lentivirus packaging and cell line construction

Cell transfection was performed following the method described by Shu et al. (19). Lentivirus packaging was conducted with the Lenti-PacHIV lentivirus packaging kit (LT001; GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA) to establish stable cell lines expressing either sh-NKAP or overexpressing NKAP. The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences targeting NKAP (sh NKAP-1: GGAAGAAGATCAAAGATAA; sh NKAP-2: GCTTATTGATATAACTTTA) were cloned into the pLVX-shRNA vector, while NKAP cDNA was inserted into the pLVX-Puro vector. Subsequently, the constructed vectors were cotransfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-mixed packaging plasmids into 293T cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, lentiviral particles were collected from the culture supernatant, and their titers were determined before being used to infect target cells. In the sh-NKAP-knockdown and NKAP-overexpression groups, sh-NC and the pLVX empty vector were used as negative controls, respectively. Successfully infected cells were selected with puromycin and subsequently harvested for further experiments.

Transwell assay

To evaluate the impact of NKAP on the invasive capacity of gastric adenocarcinoma cells, a Transwell invasion assay was conducted. STAD cells in the logarithmic growth phase were serum-starved for 24 hours, washed with PBS, and digested with trypsin. The cells were then collected and resuspended in serum-free medium at a density of 2×105 cells/mL. Matrigel was precoated onto the upper chamber of the Transwell insert, while the lower chamber was filled with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS. A 200-µL cell suspension was seeded into the upper chamber and incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Post-incubation, the chambers were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The number of cells that had migrated through the membrane was counted in five randomly selected fields under an inverted microscope. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure data reliability.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

To assess the viability of GC cells, CCK-8 (CA1210; Solarbio, Beijing, China) was applied. Logarithmically growing cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4×103 to 104 cells per well, with each well containing 100 µL of medium. The plates were incubated at 37 ℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 hours. Subsequently, 10 µL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well, with care taken to avoid bubble formation and thus ensure measurement accuracy. After an additional 3–4 hours of incubation, absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure data reliability.

EdU incorporation assay

To assess the proliferation capacity of STAD cells, an EdU incorporation assay was performed with the Cell-Light5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) Apollo Imaging Kit (C10310, Ribobio, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Logarithmically growing STAD cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells per well. After 24 hours of incubation at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2, 50 µM of EdU working solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. Apollo fluorescent labeling was then performed as per the kit’s protocol, followed by nuclear counterstaining with Hoechst 33342 for 10 minutes in the dark. After PBS washes, EdU-positive cells were observed with a fluorescence or confocal laser scanning microscope. Five random fields were selected for counting of EdU-positive cells and their proportion. All experiments were repeated three times to ensure data reliability.

Flow cytometry

To assess marker expression in cell and tissue samples, flow cytometry was employed. Cells were seeded into six-well plates and cultured until reaching 60–70% confluence, which was followed by two PBS washes. For tissue samples, single-cell suspensions were prepared with mechanical dissociation combined with enzymatic digestion, and cell clumps were removed via filtration through a 70-µm mesh. The cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated antibodies at appropriate concentrations in staining buffer and kept in the dark. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were processed with FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure data reliability.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The IL-10 levels in the cell supernatants were quantified using human IL-10 ELISA Kit (Cat# PI528, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, add the standard and cell supernatant equally in proportion into the microplate wells, keeping the blank wells empty. After adding the conjugate labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), incubate at 37 ℃ for 1 hour. Following washing, add Substrate A and Substrate B, and incubate at 37 ℃ for 15 minutes. Add the stop solution to terminate the reaction, and measure the absorbance at 450 nm within 15 minutes.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-NCG xenograft mouse model

This study established a humanized GC xenograft mouse model using 6-week-old female human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-NCG (HuPBMC-NCG) mice (Jiangsu Jicui Yaokang, Nanjing, China). After 1 week of adaptive feeding in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment, the mice were subcutaneously injected with a 100-µL suspension containing 1×106 GC cells. Seven days later, the human immune microenvironment was reconstructed via the intravenous injection of 5×106 HuPBMCs.

Subsequently, the experimental group received intravenous injections of anti-PD-L1 (200 µg per dose) and anti-IL-10 antibodies (200 µg per dose), while the control group received an equal dose of IgG. Treatments were administered once per week. Tumor length and width were measured every 3 days, and tumor volume was calculated with following the formula: tumor volume = length × width2 ×1/2. Body weight changes were also recorded. On day 21 after PBMC implantation, when tumor volume was below 2,000 mm3, the mice were killed. Tumor tissues were collected for flow cytometric analysis of immune cell infiltration. Randomized grouping was used to minimize bias, but blinding was not implemented. Experiments were performed under a project license (No. IACUC-2024XS109) granted by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, in compliance with the animal use regulations of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the care and use of animals. A protocol was prepared before the study without registration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9 (Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA). Differences between two groups were assessed with the t-test, while comparisons between multiple groups were conducted via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The association between NKAP expression and clinical characteristics was evaluated with the χ2 test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

NKAP expression in GC was associated with immuno-neoadjuvant sensitivity

An analysis of 415 GC cases and 34 normal tissue samples from the TCGA database revealed a significant upregulation of NKAP in GC tissues (Figure 1A). We performed the Spearman correlation analysis, which is used to show the correlation between the pathway score and the expression of NKAP gene. In this plot (Figure 1B), the x-axis represents the distribution of the expression of gene NKAP, and the y-axis represents the distribution of the pathway score. It indicated that NKAP expression was positively associated with tumor proliferation pathway and negatively correlated with immune response pathway.

Figure 1.

Analysis of NKAP expression and its clinical correlation in gastric cancer. (A) Analysis of TCGA gastric cancer dataset indicated that NKAP is significantly upregulated in gastric cancer tissues as compared to normal tissues. (B) Correlation analysis based on TCGA gastric cancer dataset indicated that NKAP expression is positively correlated with tumor proliferation and negatively correlated with immune response. In this plot, the x-axis represents the distribution of the expression of gene NKAP, and the y-axis represents the distribution of the pathway score. The values at the top represent the results of the Spearman correlation analysis, including the P value and correlation coefficient. (C) qPCR analysis of patient samples undergoing immune neoadjuvant therapy revealed differential NKAP mRNA expression levels, according to which NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups were formed, data are shown as ΔCt. (D) Immunofluorescence staining was used to analyze NKAP protein expression in patient samples after neoadjuvant immunotherapy (NKAPHigh vs. NKAPLow). Cell nuclei are stained blue, and NKAP is stained red; magnification 10×. (E) The irRVT in the NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups was evaluated according to the proportion of viable tumor area within the total tumor bed. *, P<0.05. CI, confidence interval; irRVT, immune-related residual viable tumor; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TPM, transcripts per kilobase million.

To further validate these findings, qPCR was performed on gastric tissue samples from 29 patients with GC who received neoadjuvant therapy with the PD-L1 inhibitor pembrolizumab. Based on the median NKAP mRNA expression level, patients were categorized into NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups. NKAP expression significantly differed among patients (Figure 1C), and NKAP protein levels in IHC aligned with the qPCR results (Figure 1D).

The comparison of clinical characteristics between patients in the NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups is presented in Table 2. The results indicate that high NKAP expression was significantly associated with TNM stage (P=0.049), lymph node metastasis (P=0.02), histological differentiation (P=0.01), and sex (P=0.045). However, no significant associations were observed with age (P=0.88), smoking history (P=0.19), PD-L1 CPS score (P=0.13), or R0 resection status (P>0.99). It is worth noting that despite the statistically significant difference in sex distribution, this finding may be influenced by the relatively small sample size.

Table 2. The relationship between the expression of NKAP and clinicopathological characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (n=29) | NKAPLow (n=14) | NKAPHigh (n=15) | P value | Reciprocal of RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.88 | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | |||

| ≤60 | 11 | 5 | 6 | ||

| >60 | 18 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Sex | 0.045 | 0.42 (0.18–0.98) | |||

| Female | 13 | 9 | 4 | ||

| Male | 16 | 5 | 11 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.19 | 1.31 (0.87–1.97) | |||

| Never | 9 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Ever | 20 | 11 | 9 | ||

| Differentiation | 0.01 | 0.38 (0.17–0.83) | |||

| Well/moderate | 16 | 6 | 10 | ||

| Poor | 13 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.02 | 0.58 (0.36–0.94) | |||

| Negative | 15 | 6 | 9 | ||

| Positive | 14 | 8 | 6 | ||

| TNM stage | 0.049 | 1.73 (1.02–2.94) | |||

| IIB | 6 | 5 | 1 | ||

| IIIA | 13 | 6 | 7 | ||

| IIIB | 10 | 3 | 7 | ||

| PD-L1 CPS | 0.13 | 1.45 (0.89–2.35) | |||

| 1–10 | 12 | 8 | 4 | ||

| ≥10 | 17 | 6 | 11 | ||

| R0 (no residual tumor) | >0.99 | 0.5 (0.01–32.82) | |||

| Yes | 28 | 14 | 14 | ||

| No | 1 | 0 | 1 |

CI, confidence interval; CPS, combined positive score; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; RR, relative risk; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

We additionally assessed the relationship between clinical responses to neoadjuvant immunotherapy and NKAP expression levels in 29 patients (NKAPLow group: n=14; NKAPHigh group: n=15) to determine the potential impact of NKAP expression on therapeutic response. The results (Table 3) demonstrated a significant advantage for the NKAPLow group in terms of immune major pathologic response (iMPR) and overall treatment benefit. Specifically, the iMPR rate in the NKAPLow group was 42.9% (6/14), significantly higher than the 13.3% (2/15) observed in the NKAPHigh group (Fisher exact test, P=0.04), suggesting that lower NKAP expression may enhance immunotherapy-induced major pathological response. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the pathological partial response (iPR) rates between the two groups (NKAPLow: 57.1%; NKAPHigh: 80.0%; P=0.27), the Mantel-Haenszel trend test revealed a significantly better overall response (ranging from complete response to no response) in the NKAPLow group than in the NKAPHigh group (P=0.02) (Figure 1E). This further supports the association between low NKAP expression and treatment sensitivity. Additionally, the only case of iNR was observed in the NKAPHigh group.

Table 3. Clinical response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in the NKAPLow and NKAPHigh groups.

| Response | Total (n=29) | NKAPLow (n=14) | NKAPHigh (n=15) | P value | RR–1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCR | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| iMPR | 8 | 6 (42.9%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.04 | 0.31 (0.07–1.21) |

| iPR | 21 | 8 (57.1%) | 12 (80.0%) | 0.27 | 0.71 (0.40–1.29) |

| iNR | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0.49 | – |

| Trend P value | – | – | – | 0.01 | – |

CI, confidence interval; iCR, immune pathological complete response; iMPR, immune major pathological response; iNR, immune pathologic non-response; iPR, immune pathological partial response; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; RR, relative risk.

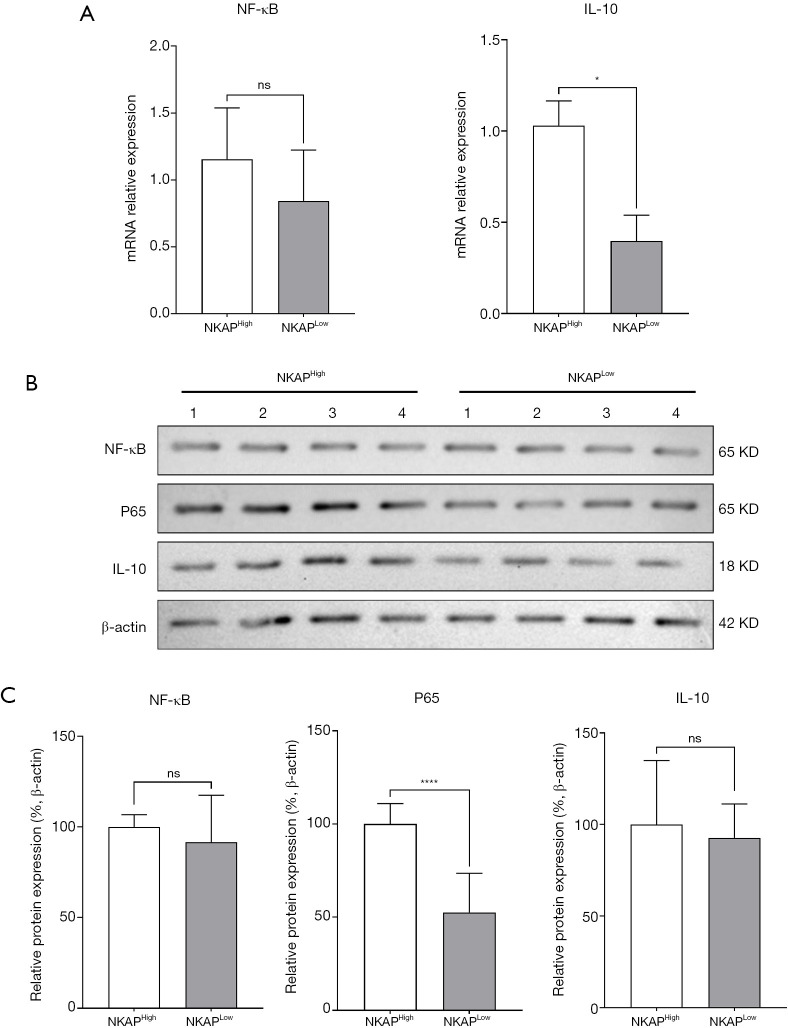

High NKAP expression in GC tissues promoted NF-κB activation and mature dendritic differentiation

To investigate the effect of NKAP expression on NF-κB activation and mature dendritic cell (mDC) differentiation, qPCR was performed to measure NF-κB and IL-10 mRNA and protein levels in the NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups. The results showed that while NF-κB expression did not differ significantly between the two groups, IL-10 levels were significantly upregulated in the NKAPHigh group (Figure 2A). Furthermore, Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the expression levels of these proteins and of phosphorylated NF-κB (P65) (Figure 2B,2C). The results demonstrated that total NF-κB expression was similar between the NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups, but the expression level of P65 was significantly elevated in the NKAPHigh group. These findings suggest that high NKAP expression in GC tissues promotes NF-κB activation and upregulates IL-10 expression.

Figure 2.

NKAP expression regulated NF-κB transcription and protein levels. (A) qPCR analysis comparing NF-κB transcription levels between NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, with statistical significance determined with the Student t-test (ns, no significant difference; *, P<0.05). (B) WB analysis of NF-κB, P65 and IL-10 protein expression levels in NKAPHigh and NKAPLow samples. β-actin served as a loading control. (C) Densitometric analysis was performed, and relative protein expression levels were quantified. Statistical significance was assessed with the Student t-test (ns, no significant difference; ****, P<0.0001). IL-10, interleukin-10; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; ns, no significant difference; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation; WB, Western blot.

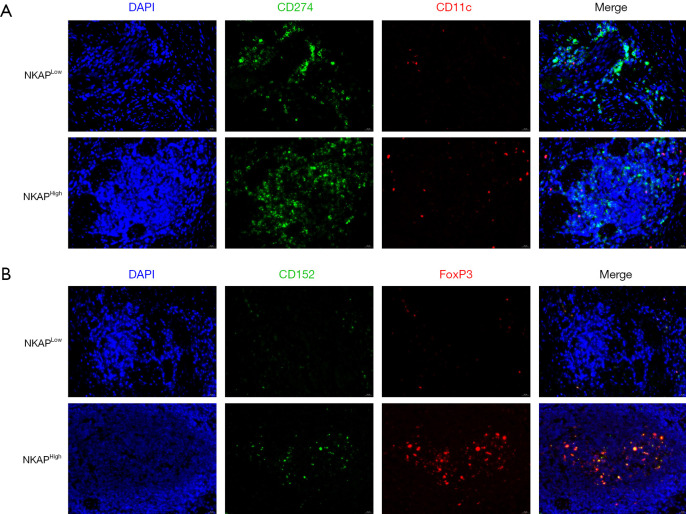

Immunofluorescence co-staining analysis revealed that the spatial reorganization of immune checkpoint molecules in GC tissues was dependent on NKAP expression levels (Figure 3). In NKAPLow tumors, as shown in Figure 3, PD-L1 (green) exhibited polarized membrane accumulation on tumor cells and partially colocalized with CD11c+ dendritic cells (red) at the tumor-stroma interface (merged signal, yellow). In contrast, NKAPHigh tumors exhibited increased CD11c+ cell infiltration but with a more diffuse distribution and significantly reduced PD-L1 colocalization. These findings suggest that NKAP may regulate dendritic cell recruitment and influence immune checkpoint accessibility.

Figure 3.

NKAP regulated the spatial distribution of immune cells in gastric cancer. (A) Distribution of mDCs in NKAPLow and NKAPHigh gastric tumors detected by immunofluorescence co-staining. In NKAPLow tumors, CD11c+ dendritic cells (red) localized at the tumor-stroma interface and colocalized with PD-L1 (CD274, green) on tumor cells (merge, yellow). In NKAPHigh tumors, CD11c+ cell infiltration increased but was diffusely distributed, with reduced PD-L1 colocalization; magnification, 50×. (B) Treg distribution in NKAPLow and NKAPHigh gastric tumors detected by immunofluorescence co-staining. In NKAPLow tumors, CTLA-4 (CD152, green) was concentrated at invasive margins and colocalized with FoxP3+ Tregs (red), with a higher Treg density in NKAPLow tumors than in NKAPHigh tumors; magnification, 50×. mDCs, mature dendritic cells; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Notably, regulatory T cell (Treg)-mediated immunosuppression was more pronounced in NKAPLow tumors (Figure 3B). As shown in Figure 3, CTLA-4 (also known as CD152, green) formed high-density clusters at the invasive margin and colocalized with FoxP3+ Tregs (red). Additionally, Treg density was significantly higher in the NKAPLow group than in the NKAPHigh group, further highlighting the immunosuppressive microenvironment associated with low NKAP expression.

Elevated NKAP expression enhanced the biological functions of GC cells

To assess NKAP expression levels in GC cell lines, we performed qPCR analysis and Western blotting on five STAD cell lines: AGS, BGC, HGC-27, SGC-7901, and MGC-803. As shown in Figure 4A,4B, NKAP expression was lowest in AGS cells and highest in HGC-27 cells. Based on these findings, AGS cells were selected for the construction of an NKAP-overexpression (OE) cell line, while HGC-27 cells were chosen for the construction of an NKAP-knockdown (KD) cell line.

Figure 4.

Molecular mechanism by which NKAP regulated IL-10 expression via the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A,B) Baseline expression levels of NKAP mRNA (A) and protein (B) in five gastric cancer cell lines (AGS, BGC, HGC-27, SGC-7901, and MGC-803) normalized to β-actin. Statistical significance was determined via one-way ANOVA (vs. AGS group). (C) NKAP-OE significantly suppressed NF-κB P65 phosphorylation and IL-10 expression, whereas NKAP knockdown (sh NKAP) exerted the opposite effect (vs. Ctrl group). (D,E) Quantitative analysis confirmed a negative correlation of NKAP expression with P65 (D) and IL-10 (E) levels. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). ns, no significant difference; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; IL-10, interleukin-10; NC, negative control; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; NKAP-OE, overexpression of NKAP; SEM, standard error of mean.

Subsequently, qPCR and Western blot analyses were conducted to validate the expression levels of NKAP, NF-κB, and P65 in both NKAP OE and NKAP KD cell lines. As shown in Figure 4C-4E, NKAP expression was significantly upregulated in the NKAP OE cell line, confirming the successful establishment of the overexpression model. Conversely, NKAP expression was markedly downregulated in the NKAP KD cell line, indicating successful knockdown. Furthermore, P65 expression was significantly higher in the NKAP OE cell line compared to the control, whereas it was markedly lower in the NKAP KD cell line relative to the control. These findings suggest that NKAP may regulate P65 expression, potentially influencing key signaling pathways in GC progression.

To evaluate the proliferative capacity of the aforementioned cell lines, we performed an EdU incorporation assay. As shown in Figure 5A,5B, the number of newly synthesized cells in the NKAP OE cell line was significantly higher than in the control group. In contrast, the number of newly synthesized cells in the NKAP KD cell line was significantly lower than in the control group. Next, a CCK-8 assay was conducted to assess cell viability. As shown in Figure 5C, the NKAP OE cell line exhibited significantly higher cell viability compared to the control group, whereas the NKAP KD cell line displayed markedly reduced viability.

Figure 5.

Effects of NKAP on the biological functions of gastric cancer cells. (A) EdU assay showed that NKAP overexpression promoted the proliferation of AGS gastric cancer cells; magnification, 10×. (B) EdU assay demonstrated that NKAP knockdown inhibited the proliferation of HGC-27 gastric cancer cells; magnification, 10×. (C) CCK-8 assay indicated that NKAP overexpression enhanced cell viability in AGS cells, whereas NKAP knockdown reduced cell viability in HGC-27 cells. (D) Transwell invasion assay showed that NKAP overexpression increased the invasive ability of AGS cells, whereas NKAP knockdown suppressed the invasive ability of HGC-27 cells; stained with crystal violet; magnification, 10×. Statistical significance was determined with the Student t-test or one-way ANOVA (ns, no significant difference; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; EdU, Cell-Light5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine; NC, negative control; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; OE, overexpression; SEM, standard error of mean.

Furthermore, a Transwell invasion assay was used to evaluate the invasive potential of these cell lines. As depicted in Figure 5D, the number of transmembrane cells in the NKAP OE cell line was significantly higher than that in the control group, whereas it was markedly lower in the NKAP KD cell line. These results indicate that elevated NKAP expression in GC cells promotes cell proliferation, viability, and invasiveness, whereas NKAP knockdown attenuates these cellular functions.

NKAP overexpression promotes IL-10 production in mDCs and enhances Treg differentiation from naïve T cells

This study examined the mechanism by which NKAP overexpression in GC cells promotes IL-10 secretion by mDCs induce the differentiation of CD4+ naïve T cells into Tregs. PBMCs were isolated from healthy donors and differentiated into immature dendritic cells (imDCs) in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. These mDCs were then cocultured with NKAP-OE or control GC cells for 48 hours in a Transwell system. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results showed a significant increase in IL-10 levels in the supernatants of the NKAP-OE group (Figure 6A), indicating that NKAP enhances IL-10 secretion by mDCs. To confirm the cellular origin of IL-10, we performed an additional ELISA assay (Figure S1), showing that NKAP-overexpressing GC cells alone produced negligible IL-10. In support of dendritic cell maturation, we observed significantly increased protein expression of CD80 and CD83 in mDCs co-cultured with NKAP-overexpressing GC cells (Figure 6B), indicating a phenotypic shift toward maturation. These findings, while distinct from spatial observations in Figure 3, suggest functional maturation of DCs in vitro.

Figure 6.

NKAP overexpression promotes IL-10 production in mDCs and enhances Treg differentiation from naïve T cells. (A) The IL-10 levels in cell supernatants after coculture of mDC with NKAP-overexpressing (NKAP OE) gastric cancer cells or control gastric cancer cells (OE NC) were detected via ELISA, and IL-10 levels in cell supernatants of the NKAP OE group were significantly increased; the co-culture system was performed in a Transwell format. ELISA-detected IL-10 primarily originated from mDCs, as validated by additional control experiments (Figure S1). (B) The expression levels of CD80 and CD83 in the cells were detected by Western blot, Elevated expression of CD80 and CD83 in NKAP-OE co-cultured mDCs is indicative of a mature or tolerogenic dendritic phenotype. (C) After coculture with NKAP OE or OE NC, mDC and naive T cells were cocultured, and the mRNA levels of FOXP3 and CD25 in T cells were detected by qPCR. (D) The level of Treg cells after coculture was detected by flow cytometry (red, NKAP OE; yellow, NKAP OE + anti-IL-10). (E) The levels of TGF-β and IL-35 in the supernatant of cocultured cells were detected by ELISA. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL-10, interleukin-10; mDC, mature dendritic cell; NC, negative control; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; OE, overexpression; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta.

Next, the mDCs were cocultured with naïve T cells for 96 hours to assess the impact of IL-10 on T-cell differentiation. qPCR analysis (Figure 6C) indicated a significant increase in FOXP3 and CD25 mRNA levels in T cells from the NKAP-OE group, indicating differentiation toward Tregs. Flow cytometry (Figure 6D) further confirmed an increased proportion of Tregs in the NKAP-OE group, suggesting that IL-10 promoted Treg differentiation. The addition of an IL-10 neutralizing antibody to the coculture system significantly inhibited the ability of mDCs to drive Treg differentiation. Additionally, ELISA (Figure 6E) revealed significantly higher levels of TGF-β and IL-35 in the NKAP-OE culture supernatant as compared to the control, further supporting the role of IL-10 in Treg differentiation. These results demonstrate that NKAP overexpression in GC cells promotes IL-10 secretion by mDCs, which in turn drives the differentiation of CD4+ naïve T cells into Tregs, with IL-10 playing a critical role in this process.

High NKAP expression promoted tumor growth and altered the immune microenvironment in a murine GC model

Tumor photos from a mouse xenograft model are shown in Figure 7A. Subcutaneous inoculation of GC cells overexpressing NKAP significantly enhanced tumor formation (Figure 7B). Interventions targeting PD-L1, IL-10, and IgG demonstrated that anti-PD-L1 treatment inhibited NKAP overexpression-induced tumor growth and that anti-IL-10 treatment attenuated its tumor-promoting effects (Figure 7C-7F).

Figure 7.

Effect of NKAP overexpression on tumor growth in the gastric cancer mouse model. (A) Tumor size of mice in each group. (B) Comparison of tumor weight and volume between mice in the NKAP OE group and Ctrl group. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points. The x-axis represents the actual measurement days, not necessarily equal intervals. (C) Comparison of tumor weight and volume of mice inoculated with NKAP OE gastric cancer cells after anti-PD-L1, anti-IL-10, and anti-IgG intervention. (D) Comparison of tumor weight and volume of mice inoculated with Ctrl gastric cancer cells after anti-PD-L1, anti-IL-10, and anti-IgG intervention. (E) Comparison of tumor weight and volume in mice inoculated with Ctrl gastric cancer cells and mice inoculated with NKAP OE gastric cancer cells intervened upon with anti-PD-L1. (F) Comparison of tumor weight and volume in mice inoculated with Ctrl gastric cancer cells and mice inoculated with NKAP OE gastric cancer cells after anti-IL-10 intervention. ns, no significant difference; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. Ctrl, control; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-10, interleukin-10; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NKAP, NF-κB activating protein; OE, overexpression; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Discussion

GC is the fifth most commonly diagnosed malignancy worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality (1). For patients with stage II/III disease, radical gastrectomy is considered the primary treatment modality, and fluoropyrimidine-based adjuvant chemotherapy has been recommended as the standard postoperative regimen (2). However, due to the variability in chemosensitivity and the subsequent development of chemoresistance, the recurrence rates among patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy remains high (3). Therefore, further elucidation of the mechanisms underlying tumor progression and therapeutic responsiveness in GC is warranted.

In this study, samples were collected from patients with GC undergoing neoadjuvant therapy with ICIs, and analyses including immunohistochemistry were performed. It was observed that, relative to the pre-treatment condition, NKAP expression was significantly reduced following PD-L1 inhibitor therapy. Based on the median expression levels, patients were stratified into NKAPHigh and NKAPLow groups. Western blot analysis revealed that the NKAPHigh group exhibited significant upregulation of phosphorylated NF-κB (P65) and PD-L1. Histological assessment of postoperative tissues further demonstrated that the number of viable tumor cells was significantly higher in the NKAPHigh group than in the NKAPLow group. Elevated NKAP expression in GC tissues was found to enhance NF-κB activation and PD-L1 expression, and high NKAP levels were positively correlated with the persistence of tumor cells following PD-L1 inhibitor therapy.

NKAP was originally identified in the context of inflammation and immune responses. A recent study has indicated that in addition to its involvement in the NF-κB signaling pathway, NKAP plays a more critical role in the immune system by inhibiting Notch-mediated transcription (15). In a study on glioma, overexpression of NKAP was found to promote tumor growth by facilitating a Notch1-dependent immunosuppressive TME, whereas downregulation of NKAP abolished tumor growth and invasion both in vitro and in vivo (15). Moreover, suppression of NKAP expression reduced the secretion of M-CSF, thereby impeding the polarization and recruitment of TAMs. Our findings indicate that high NKAP expression enhances the activation of NF-κB in GC tissues, which in turn promotes the proliferation, viability, and other biological functions of GC cells.

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in suppressing immune responses and maintaining immune homeostasis. Research has shown that mDCs express the IL-10 receptor and, under specific environmental stimuli—such as bacterial or viral infections or under immune regulatory conditions—mDCs can secrete IL-10. The production of IL-10 contributes to the attenuation of inflammatory responses and the inhibition of immune cell activation, thereby modulating the overall immune response and reducing tissue damage and inflammation. However, IL-10 secretion by mDCs is not ubiquitous but occurs under particular conditions. Furthermore, IL-10 may have a dual role in the TME as it can both suppress inflammation and antitumor immunity and, paradoxically, promote tumor immune evasion. In our study, immunofluorescence and coculture experiments revealed that high NKAP expression in GC cells leads to an upregulation of IL-10 expression in mDCs, suggesting an immunosuppressive role for NKAP in GC.

mDCs are critical antigen-presenting cells in the immune system, responsible for capturing and processing exogenous antigens and presenting them to T cells to initiate immune responses (20). In the process of tumor immune evasion, tumor cells and their microenvironment employ various mechanisms to inhibit mDC function, thereby diminishing effective immune responses (21). For example, inhibitory cytokines secreted by tumor cells and tumor-associated cells can suppress mDC maturation and antigen-presenting capacity, reducing the activation and proliferation of T cells.

Tregs primarily function to suppress immune responses, maintain immune tolerance, and prevent excessive immune reactions (22). In tumor immune evasion, an increase in the number and enhanced functionality of Tregs can inhibit the activity of immune cells—including effector T cells—thus impairing the immune-mediated killing of tumor cells (23).

In this study, coculture experiments involving T cells, NKAP-OE GC cells, and mDCs revealed that high NKAP expression modulates IL-10 secretion by mDCs, promoting the differentiation of naive T cells into Tregs and establishing an immunosuppressive TME. Although IL-10 is classically known to inhibit dendritic cell maturation, a recent study suggest that under specific immunosuppressive conditions, IL-10 can promote a tolerogenic DC phenotype characterized by partial maturation marker expression (e.g., CD80, CD83) but skewing T-cell responses toward Treg differentiation (23). Our results are consistent with this tolerogenic maturation model. These results further confirm that NKAP facilitates the interaction between mDCs and Tregs, in addition to contributing to the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

This study revealed that high NKAP expression in GC cells promotes cellular proliferation and viability. Moreover, elevated NKAP expression may enhance IL-10 secretion by mDCs within the TME, thereby influencing the differentiation of naive T cells into Tregs and facilitating tumor immune evasion. This process may ultimately affect the therapeutic efficacy of ICIs.

Conclusions

NKAP is a critical regulator of GC immune escape, linking NF-κB-driven IL-10 production in mDCs to Treg-mediated immunosuppression during anti-PD-L1 therapy. Targeting NKAP may reverse resistance to ICIs, offering a promising strategy for improving clinical outcomes in patients with GC.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University (approval No. HDFYLL-KY-2023-093) and informed consent was taken from all the patients. Animal experiments were performed under a project license (No. IACUC-2024XS109) granted by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, in compliance with the animal use regulations of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the care and use of animals.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE and MDAR reporting checklists. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2025-491/rc

Funding: This research was supported by the 2022 Hebei Provincial Government Funded Medical Talents Project (No. Hebei Financial Pre-Fu [2022] 180) and the Medical Science Foundation of Hebei University (No. 2022A03).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2025-491/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: J. Gray)

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2025-491/dss

References

- 1.Zhong H, Zhou S, Yin S, et al. Tumor microenvironment as niche constructed by cancer stem cells: Breaking the ecosystem to combat cancer. J Adv Res 2025;71:279-96. 10.1016/j.jare.2024.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu X, Tian Y, Lv C. Decoding the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of tumor-associated macrophages. Mol Cancer 2024;23:150. 10.1186/s12943-024-02064-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ning J, Ye Y, Shen H, et al. Macrophage-coated tumor cluster aggravates hepatoma invasion and immunotherapy resistance via generating local immune deprivation. Cell Rep Med 2024;5:101505. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Disis ML. Mechanism of action of immunotherapy. Semin Oncol 2014;41 Suppl 5:S3-13. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong X, Madeti Y, Cai J, et al. Recent developments in immunotherapy for gastrointestinal tract cancers. J Hematol Oncol 2024;17:65. 10.1186/s13045-024-01578-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gul A, Stewart TF, Mantia CM, et al. Salvage Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma After Prior Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3088-94. 10.1200/JCO.19.03315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willsmore ZN, Coumbe BGT, Crescioli S, et al. Combined anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade: Treatment of melanoma and immune mechanisms of action. Eur J Immunol 2021;51:544-56. 10.1002/eji.202048747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suresh K, Naidoo J, Lin CT, et al. Immune Checkpoint Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Benefits and Pulmonary Toxicities. Chest 2018;154:1416-23. 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai J, Gao Z, Li X, et al. Regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Oncotarget 2017;8:110693-707. 10.18632/oncotarget.22690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassel JC, Heinzerling L, Aberle J, et al. Combined immune checkpoint blockade (anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4): Evaluation and management of adverse drug reactions. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;57:36-49. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen D, Li Z, Yang Q, et al. Identification of a nuclear protein that promotes NF-kappaB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;310:720-4. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thapa P, Chen MW, McWilliams DC, et al. NKAP Regulates Invariant NKT Cell Proliferation and Differentiation into ROR-γt-Expressing NKT17 Cells. J Immunol 2016;196:4987-98. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pajerowski AG, Nguyen C, Aghajanian H, et al. NKAP is a transcriptional repressor of notch signaling and is required for T cell development. Immunity 2009;30:696-707. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo X, Yang F, Liu T, et al. Loss of LRP1 Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via UFL1-Mediated Activation of NF-κB Signaling. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024;11:e2401672. 10.1002/advs.202401672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu G, Gao T, Zhang L, et al. NKAP alters tumor immune microenvironment and promotes glioma growth via Notch1 signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019;38:291. 10.1186/s13046-019-1281-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1976-86. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cottrell TR, Thompson ED, Forde PM, et al. Pathologic features of response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 in resected non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a proposal for quantitative immune-related pathologic response criteria (irPRC). Ann Oncol 2018;29:1853-60. 10.1093/annonc/mdy218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Kim B, Jung HA, et al. Nivolumab for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and the predictive role of PD-L1 or CD8 expression in its therapeutic effect. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2021;70:1203-11. 10.1007/s00262-020-02766-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shu W, Liu G, Dai Y, et al. The oncogenic role of NKAP in the growth and invasion of colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2019;42:2130-8. 10.3892/or.2019.7322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sittig SP, de Vries IJM, Schreibelt G. Primary Human Blood Dendritic Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy-Tailoring the Immune Response by Dendritic Cell Maturation. Biomedicines 2015;3:282-303. 10.3390/biomedicines3040282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali S, Toews K, Schwiebert S, et al. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Impair CD171-Specific CD4(+) CAR T Cell Efficacy. Front Immunol 2020;11:531. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang JH, Zappasodi R. Modulating Treg stability to improve cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2023;9:911-27. 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouyang Y, Gu Y, Zhang X, et al. AMPKα2 promotes tumor immune escape by inducing CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and CD4+ Treg cell formation in liver hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2024;24:276. 10.1186/s12885-024-12025-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]