Abstract

Objective

Intravascular leiomyoma (IVL) is a rare benign tumor extending from the uterus into the surrounding venous structures and may extend into the heart, leading to occlusion of the tricuspid or pulmonary valve resulting in sudden cardiac death.

Key Steps

We present a 56-year-old woman with an IVL extending into the right atrium and ventricle. We excised in a staged procedure, first removing the intracardiac and suprahepatic tumor component, followed by laparotomy, excision of the pelvic mass, bilateral oophorectomy, and caval thrombectomy 6 weeks later.

Potential Pitfalls

IVL may extend into the heart necessitating total cardiopulmonary bypass for excision either in a single or multistage procedure. We recommend a multistage approach because the tumor is slowly growing and encapsulated.

Take-Home Message

Management requires careful planning with multiple surgical disciplines, cardiology, and radiology to determine the extent and plan for surgical excision.

Key Words: cardiac tumor, intracardiac leiomyomatosis, intravascular leiomyoma

Graphical Abstract

Intravascular leiomyoma (IVL) is a very rare tumor which may extend from the myometrium into the surrounding venous structures, inferior vena cava (IVC), and rarely the heart.1 Approximately 10% to 30% of leiomyomas extend into the IVC and cardiac chambers, known as intracardiac leiomyomatosis.2 Invasion into the heart can lead to obstruction of the tricuspid valve, syncope, and sudden cardiac death.3 Management of IVL may be performed with a single or multistaged procedure with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with or without deep hypothermic circulatory arrest.4 Because of the rare nature of this disease, data regarding the optimal surgical strategy are limited. In this report, we present a case of IVL extending into the heart managed with a multistage procedure without deep hypothermic circulatory arrest.

Take-Home Messages

-

•

Intravascular leiomyomas are a rare benign tumor with an indolent course and vague symptoms, and may extend into the heart.

-

•

This case describes a multistage approach to addressing IVL first by excision of the intracardiac component to prevent sudden cardiac death from right ventricular outflow obstruction, and subsequently an abdominal surgery to address remaining disease in the inferior vena cava and pelvic structures.

Case Summary

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and uterine fibroids and hysterectomy in the past year presented to an outside facility with nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, and hypotension. She had experienced several weeks of nonspecific muscular pain, joint pain, new bilateral leg pain, and abdominal pressure. In the intensive care unit she also developed increased work of breathing. She had a past medical history of hypertension, chronic gastritis, uterine fibroids, and anxiety. Past surgical history included a hysterectomy performed within the past year.

A computed tomography pulmonary embolism protocol performed at the outside facility demonstrated a large IVC mass. Subsequent computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis showed a pelvic mass measuring 8.8 cm with extensive intravenous tumor extension originating from the left gonadal vein and extending into the left renal vein, bilateral iliac veins, IVC, and the right atrium/ventricle (Figure 1A). The mass within the atrium measured 7.5 cm, and cardiac magnetic resonance demonstrated a longitudinal mass filling the entire length of the visualized IVC with a large, rounded tip (Figure 1B) which was mobile and transited across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle during diastole and fell back into the right atrium during systole. The mass was vascular and consistent with tumor rather than thrombus. Echocardiogram findings confirmed the findings previously described. Tissue sampling performed by interventional radiology was consistent with IVL.

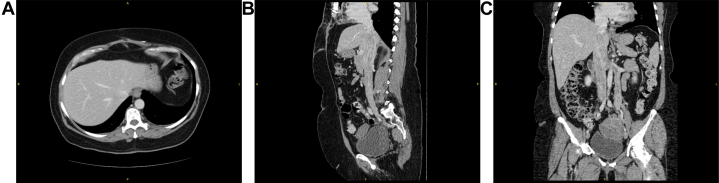

Figure 1.

Preoperative Imaging of the Intracardiac Portion of the Intravascular Leiomyoma

(A) Computed tomography showing extension into the right atrium. (B) Cardiac-gated magnetic resonance of the mass. (C) Transesophageal echocardiogram of the mass within the right atrium abutting the tricuspid valve.

Procedural Steps

The patient was jointly managed by cardiac, vascular, and gynecologic surgery, and cardiology. We planned a 2-stage excision, first addressing the intracardiac and proximal IVC tumor to reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death, then to perform laparotomy with excision of the remaining IVL and pelvic masses. In the first stage, we performed a sternotomy, atriotomy, and total CPB. The mass occupied most of the IVC at the level of the diaphragm, and the left iliac veins; therefore, CPB cannulation was achieved via super vena cava and right iliac venous cannulation and suction drainage. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated the mass was freely mobile within the atrium and proximal IVC (Figure 1C). The heart was arrested to reduce blood flow through the coronary sinus and enhance visualization within the right atrium, and the IVL was pulled into the atrium and transected as low as possible to allow for clamping or occlusion of the suprahepatic or infrahepatic IVC in the subsequent abdominal procedure (Figure 2). She was started on anticoagulation postoperatively and discharged home on postoperative day 6.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative Photographs From the Cardiac Excision of the Tumor

(A) Tumor in situ in the right atrium. (B) Excised portion of the tumor.

Six weeks after this, she returned for tumor infradiaphragmatic thrombectomy via midline laparotomy. Anticoagulation was stopped 2 days preoperatively. Computed tomography venogram demonstrated clearance of the tumor to the level of the intrahepatic IVC (Figure 3). Venovenous bypass was initiated via the internal jugular vein and bilateral iliac veins, and fluoroscopically guided balloon occlusion of the infrahepatic IVC was performed to protect from thromboembolic events during tumor manipulation. Using the left gonadal vein orifice, left renal vein tumor thrombectomy was performed; however, the tumor was densely adherent at the junction of the renal vein and IVC (Figure 4), resulting in laceration requiring primary reconstruction of the renal vein. An additional longitudinal venotomy was made on the juxtarenal IVC, and suprarenal thrombectomy was performed. The tumor was partially adherent and although it was able to be removed at this level, significant blood loss was encountered. Gynecology also performed excision of the pelvic mass and bilateral oophorectomy.

Figure 3.

Computed Tomography Venogram After Atrial Mass Excision

(A) Axial, (B) sagittal, and (C) coronal sections demonstrating pelvic mass with extension into left gonadal, left renal, and inferior vena cava (IVC) and tumor burden cleared to the level of the intrahepatic IVC.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative Photograph

Intraoperative photographs from the abdominal excision of the tumor showing the IVC and massively dilated left renal (∗) and gonadal veins (∗∗). IVC = inferior vena cava.

Given the significant blood loss, it was decided to perform a third-stage procedure for the residual tumor burden in the distal IVC and iliac veins. She was taken to the intensive care unit and resuscitated before completion thrombectomy 4 days later. The remaining tumor was excised from the IVC and left iliac vein, but it was adherent 4 cm from the origin of the left internal iliac vein and the tumor itself was transected at this level. Intraoperative ultrasound demonstrated the tumor extended deep into numerous pelvic tributaries; therefore, the internal iliac vein was ligated because it was not possible to safely or fully excise the tumor. Completion venogram demonstrated widely patent venous structures with no filling defects (Figure 5). Her course was complicated by prolonged ileus requiring total parenteral nutrition, and she was discharged home on postoperative day 18. No further resection was performed for the residual disease, and she was followed as an outpatient by gynecology with no recurrence of symptoms at 1 year postoperatively.

Figure 5.

Intraoperative Venogram

(A) Initial venogram with occluded infrahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) distally. (B) After juxtarenal IVC tumor thrombectomy with patency to level of renal veins at completion of second operation. (C to F) After completion thrombectomy of distal IVC and left iliac vein now widely patent.

Potential Pitfalls

The optimal surgical management of an IVL is unclear and requires coordination between multiple surgical disciplines, cardiology, and radiology. In this case, we opted for a multistage procedure to first address the potentially life-threatening intracardiac component before addressing the remaining tumor burden in the abdomen. We do not feel there are enough data to advocate for single or multistage procedures; however, we feel this case does demonstrate the safety and feasibility of performing a multistage procedure and avoiding deep hypothermic circulatory arrest.

It avoids a single long procedure with more risks and more blood loss. The inflammatory response and platelet dysfunction that comes with CPB used for cardiac surgery when added with large volume blood loss in a fully anticoagulated patient undergoing both cardiac and abdominal vascular surgeries at a single session may carry more risk of morbidity and mortality when compared with a multistage approach. Giving few weeks for the sternotomy incision to heal before attempting the abdominal stage is optimal to avoid sternal wound infections that may occur if there is any bowel injury or contamination of the field if performed as a single stage cardiac and abdominal procedure.

Although the tumor does not typically invade the vessel wall, it may be tightly adhered, and caution is advised when removing the tumor if resistance is encountered. As in this case, significant bleeding may be encountered. Blood products should be immediately available in the operating room and consideration given to allowing for resuscitation in the intensive care unit before completion of the IVL removal. Hypothermic circulatory arrest may allow for less blood loss if injury to the venous structures occurs but also causes increased coagulopathy and overall blood loss has not been shown to be less with a single or staged approach.5 Careful surgical decision-making is required, and large blood loss should be anticipated.

Discussion

The presentation of IVL is often vague and patients may be asymptomatic if the tumor is confined to the vessels within the uterus. Leg swelling, weakness, fatigue, or dyspnea may develop as the tumor progresses. Intracardiac extension may present with heart failure, syncope, or sudden cardiac death if there is occlusion of the right-sided heart valves.1,6 Cross-sectional imaging and ultrasound is crucial to delineate the full extent of the tumor burden for operative planning. The diagnosis of IVL should be strongly considered in a woman with a large intravascular tumor and a history of uterine leiomyoma or previous hysterectomy.

Tumor pathology is benign and the course often indolent, which contributes to the vague and progressive symptoms. Tumors typically originate from the ovarian or internal iliac veins and may extend to the pulmonary artery.7 A review by Lim et al7 demonstrated average blood loss of 3307 mL during resection, and multiple reports of retroperitoneal hemorrhage and vascular injury, as we noted during removal of the tumor from the renal vein and IVC in our case. In our case, the intracardiac component was larger than the vena cava, necessitating atriotomy to remove the tumor. If smaller than the IVC, it is often not adhered to the intracardiac structures and may be pulled down into the vena cava.5 Multiple classification systems exist to help describe both the size and extent of the tumor burden which is critical for successful surgical planning.2,5,8

Conclusions

The nature of the IVL and preoperative assessment of its characteristics including diameter, invasion extent, and adhesion to vessel wall are critical for a successful surgical strategy.2 Regardless of the approach selected for these patients, a well-coordinated plan between vascular/cardiac/gynecologic surgery, cardiology, and radiology is crucial to define the extent of involvement and provide optimal care for patients with this rare and potentially fatal tumor.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Garcés Garcés J., Terán Camacho F., Dávalos Dávalos G., et al. Intravascular leiomyomatosis with cardiac extension, a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;18:256. doi: 10.1186/s13019-023-02344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma G., Miao Q., Liu X., et al. Different surgical strategies of patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Y., Gao X., Yang C., Liu J., Jin B., Shang D. Intravascular leiomyomatosis extending to right atrium: a rare caused syncope. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:287.e7–287.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Y., Dong S., Song B. Surgical strategy for intravenous cardiac leiomyomatosis. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H., Xu J., Lin Q., et al. Surgical treatment strategies for extra-pelvic intravenous leiomyomatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:153. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu N., Long Y., Liu Y. Intravenous leiomyomatosis: case series and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48 doi: 10.1177/0300060519896887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim W.H., Lamaro V.P., Sivagnanam V. Manifestation and management of intravenous leiomyomatosis: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2022;45 doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Liang M., Ma G., et al. Surgical treatment for intravenous-cardiac leiomyomatosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54:483–490. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]