Abstract

This study aimed to elucidate the potential relationship between central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) and both endogenous hypercortisolism and the administration of exogenous corticosteroids. Case 1 involved a 39-year-old female patient who presented with blurred vision and metamorphopsia. Ophthalmologic examinations confirmed bilateral CSC. Biochemical and clinical evidence suggested hypercortisolism, and abdominal computed tomography revealed an adrenal adenoma, leading to a diagnosis of adrenocorticotropin-independent Cushing syndrome (CS). Postoperatively, a regression of serous retinal detachments was observed within 6 weeks. Case 2 referred to a 60-year-old male patient with hyperthyroidism and Graves orbitopathy who experienced vision loss after intravenous administration of 4.5 g of methylprednisolone over 10 weeks. Vision deteriorated after glucocorticoid therapy but improved 6 months later on discontinuation. Subsequently, the patient received peribulbar injections of triamcinolone acetonide, resulting in acute vision loss, with ophthalmologic examinations confirming CSC. After the cessation of exogenous corticosteroids, CSC resolved, and retinal pigment epithelium detachment also resolved at 3 months. Although causality cannot be definitively established with only 2 cases, the spontaneous resolution of subretinal fluid following corticosteroid withdrawal is highly indicative. The use of both endogenous hypercortisolism and exogenous corticosteroids is implicated as a risk factor for CSC, warranting increased vigilance from endocrinologists.

Keywords: central serous chorioretinopathy, Cushing syndrome, corticosteroids, cases

Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) is a retinal condition characterized by the seepage of fluid from the choroidal vasculature through a compromised retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), leading to the formation of a localized serous detachment of the neurosensory retina [1]. Patients commonly report symptoms such as blurred vision, metamorphopsia, micropsia, macropsia, and central scotoma. A population-based retrospective cohort study conducted in Asian populations estimated a mean age-adjusted incidence of 27 per 100 000 in men and 15 per 100 000 in women [2]. A cohort study reported that CSC affects 5.4 per 10 000 person-years for men and 1.6 per 10 000 person-years for women among corticosteroid users and nonusers, respectively, indicating that corticosteroid use may be a risk factor for CSC [3].

This report presents 2 CSC cases associated with endogenous hypercortisolism or exogenous corticosteroid exposure to contribute to the body of evidence implicating corticosteroids in the etiology of CSC.

Case Presentation

Case 1

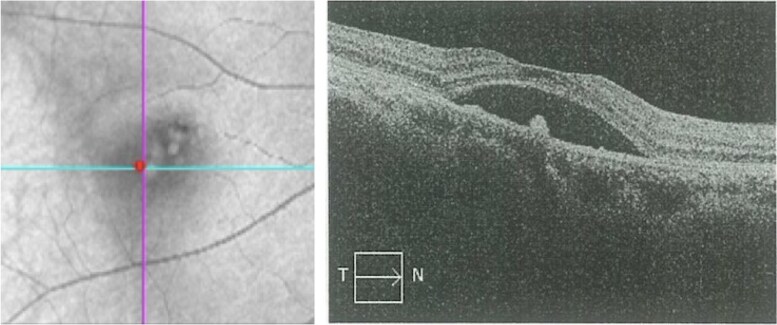

A 39-year-old female patient presented with a 7-month history of visual impairment in the right eye (RE) and 2 months’ progressive blurred vision and metamorphopsia. She exhibited progressive weight gain, round face, and hypokalemia. Computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands revealed an adenoma. Visual acuity at the time of presentation was 0.5 in the left eye (LE) and 0.6 in the RE, with a diagnosis of serous retinal detachment in the RE. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the RE demonstrated serous detachment of the neurosensory retina associated with RPE detachment (Fig. 1), consistent with CSC. The initial clinical signs suggested hypercortisolism, prompting referral to the endocrinology department for further examination.

Figure 1.

Optical coherence tomography of the right eye at presentation demonstrating macular edema and serous detachment of the neurosensory retina associated with retinal pigment epithelium detachment, with a subretinal fluid height of 436 μm, consistent with the diagnosis of central serous chorioretinopathy.

Case 2

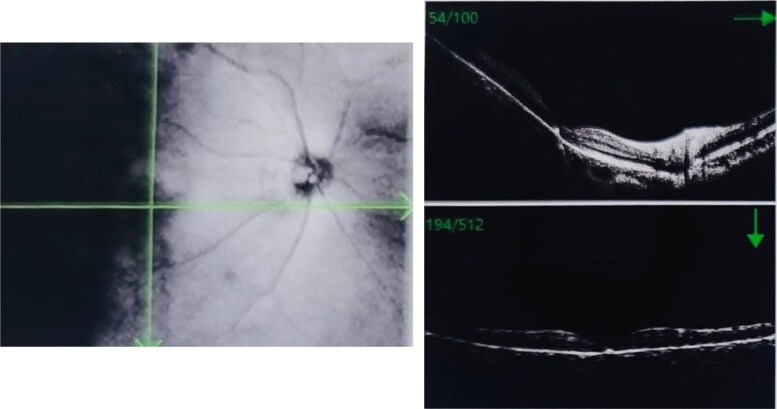

A 60-year-old male patient with a history of hyperthyroidism and Graves orbitopathy (GO) presented with vision loss in the LE over the past 2 weeks. The patient was diagnosed with GO 1 year prior. At that time, OCT revealed a small accumulation of fluid beneath the neurosensory retina, leading to serous detachment (Fig. 2). He was admitted to the 900 Hospital of the Joint Service Support Force of the People's Liberation Army of China for intravenous glucocorticoid (GC) therapy, with a cumulative dose of 4.5 g of methylprednisolone, administered in 10 weekly infusions (3 consecutive days of infusions of 0.5 g during the first week, 3 weekly infusions of 0.5 g, followed by 6 weekly infusions of 0.25 g). Thyroid dysfunction was managed with 10 mg thiamazole given orally twice a day. The patient experienced blurred vision after intravenous GC therapy, which resolved after 6 months. Three months prior, the patient received 5 peribulbar injections of triamcinolone acetonide (TA) 40 mg every 2 weeks, leading to acute vision loss and metamorphopsia in the LE. The patient was referred to the endocrinology department for optimal treatment of GO.

Figure 2.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of the left eye of case 2. At the diagnosis of Graves orbitopathy, before triamcinolone acetonide injections. OCT images at presentation demonstrating a small amount of fluid accumulation beneath the neurosensory retina, with a subretinal fluid height of 186 μm.

Diagnostic Assessment

Case 1

The physical examination revealed hypertension (143/94 mm Hg), a weight gain of 5 kg over the past year (current weight, 55.6 kg), a moon-shaped face, increased vellus hair, subcutaneous ecchymosis, and thin skin on the limbs. First-line screening tests revealed a failure of morning cortisol suppression during a low-dose (1 mg) dexamethasone suppression test, with a cortisol level of 21.76 µg/dL (600.03 nmol/L) (normal reference range, < 1.81 µg/dL; < 50 nmol/L) and increased urinary free cortisol of 994.43 µg/24 hours (2744.62 nmol/24 hours) (normal reference range, 19.28-317.5 µg/24 hours; 53.2-876.3 nmol/24 hours). Details on the circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion and the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test are provided in Table 1. The patient was diagnosed with adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH)-independent CS. Plasma levels of aldosterone (11.6 ng/dL; 321.32 pmol/L; normal reference range in the lying position, 3.0-23.6 ng/dL; 83.1-653.72 pmol/L), renin (8.6 µIU/mL; 8.6 mU/L; normal reference range, 2.8-39.9 µIU/mL; 2.8-39.9 mU/L), and metanephrines (210.02 pg/mL; 106.5 pmol/L; normal reference range, ≤ 82.82 pg/mL; ≤420 pmol/L) and methoxyepinephrine (1.21 ng/mL; 380.6 pmol/L; normal reference range, ≤ 2.26 ng/mL; ≤710 pmol/L) were normal. Abdominal CT revealed a right adrenal oval-shaped adenoma measuring 29 × 21 mm with irregular enhancement (Fig. 3). Biochemical examination revealed hypokalemia (3.34 mEq/L; 3.34 mmol/L; normal reference range, 3.5-5.5 mEq/L; 3.5-5.5 mmol/L). The oral glucose tolerance test indicated increased postprandial blood glucose and insulin resistance (Table 2). Based on 24-hour blood pressure (BP) monitoring, the patient was diagnosed with grade 1 hypertension (average BP, 148/102 mm Hg), without prior antihypertensive drug use. The patient denied a history of hormone drug abuse and had not taken exogenous steroids.

Table 1.

Circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion

| ACTH | F | UFC | Normal reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Am | <100.12 pg/mL (<2.2 pmol/L) | 20.36 µg/dL (562.66 nmol/L) | ACTH (0.04 –0.31 pg/mL; 1.6-13.9 pmol/L) | |

| 8 Am | <100.12 pg/mL (<2.2 pmol/L) | 23.37 µg/dL (646.04 nmol/L) | 998.04 µg/24 h (2744.62 nmol/24 h) | F (4.81-19.43 µg/dL; 133-537 nmol/L) |

| 4 Pm | 147.45 pg/mL (3.24 pmol/L) | 22.58 µg/dL (624.14 nmol/L) | UFC (19.3-318.7 µg/24 h/53.2-876.3 nmol/24 h) | |

| LDDST | 109.22 pg/mL (2.4 pmol/L) | 22.15 µg/dL (612.35 nmol/L) | 700.03 µg/24 h (1925.08 nmol/24 h) |

Abbreviations: ACTH: adrenocorticotropin hormone; F: cortisol; LDDST: low-dose dexamethasone suppression test; UFC: urinary free cortisol.

Figure 3.

Abdominal computed tomography scan revealing a right adrenal oval-shaped adenoma measuring 29 × 21 mm with irregular enhancement.

Table 2.

Oral glucose tolerance test, 75 g

| Blood glucose | Insulin | C-peptide (nmol/L) | Normal reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 75.06 mg/dL (4.17 mmol/L) | 2.9 mU/L (17.40 pmol/L) | 1.35 ng/mL (0.45 nmol/L) | Blood glucose (61.2-109.8 mg/dL; 3.4-6.1 mmol/L) |

| 60 min | 230.94 mg/dL (12.83 mmol/L) | 141.8 mU/L (850.8 pmol/L) | 13.77 ng/mL (4.59 nmol/L) | Insulin (2.6-24.9 mU/L; 15.6-149.4 pmol/L) |

| 120 min | 147.78 mg/dL (8.21 mmol/L) | 111.4 mU/L (668.4 pmol/L) | 15.99 ng/mL (5.33 nmol/L) | C-peptide (1.1-4.4 ng/mL; 0.37-1.47 nmol/L) |

Case 2

Visual acuities were 0.25 in the LE and 0.6 in the RE, with best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) values of 0.3 in the LE and 1.0 in the RE. The intraocular pressure was 16.9 mm Hg in the LE and 18.0 in the RE. Physical examination revealed exophthalmos in both eyes, eyelid edema, conjunctival congestion, and diplopia in the right, upper-right, lower-right, and left gaze. OCT showed serous detachment of the neurosensory retina, accompanied by a small RPE detachment (Fig. 4). Thyroid function tests revealed a free triiodothyronine (FT3) level of 4.10 pg/mL (6.23 pmol/L; normal reference range, 1.82-4.14 pg/mL; 2.76-6.3 pmol/L), free thyroxine (FT4) of 11.98 pg/mL (15.57 pmol/L; normal reference range, 8.02-18.71 pg/mL; 10.42-24.32 pmol/L), and thyrotropin (TSH) of 0.01 µIU/mL (0.01 mIU/L; normal reference range, 0.35-5.5 µIU/mL; 0.35-5.5 mIU/L), with thyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb) level of 13.05 U/L (normal reference range, ≤ 1.75 U/L). Orbital magnetic resonance imaging showed severe inflammation and hypertrophy in the superior, inferior, and internal rectus muscles, and thyroid ultrasonography suggested diffuse goiter and thyroid inflammation.

Figure 4.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of the left eye of case 2. After triamcinolone acetonide injections. OCT images showing serous detachment of the neurosensory retina accompanied by a small retinal pigment epithelium detachment, consistent with the diagnosis of central serous chorioretinopathy, with a subretinal fluid height of 583 μm.

Treatment

Case 1

After evaluation and obtaining informed consent, the patient underwent right laparoscopic resection of the adrenal adenoma in the department of urinary surgery. Histological examination confirmed an adrenocortical adenoma.

Case 2

The patient was advised to quit smoking and avoid light exposure. The methimazole dosage was adjusted to 10 mg once a day, and a selenium yeast tablet 100 mg once a day was added. Following evaluation, GC infusion was considered to have exacerbated CSC and RPE detachment; thus, we refrained from using this therapy. After providing informed consent, the patient was transferred to the department of ophthalmology for orbital decompression aimed at thyroid eye disease.

Outcome and Follow-up

Case 1

Postoperatively, the patient received steroid replacement therapy. At 2 months postoperatively, the patient lost 3 kg, with regression of the moon-shaped face and subcutaneous ecchymosis. Laboratory data were as follows: cortisol, 0.06 µg/dL (1.66 nmol/L; normal reference range, 4.27-24.89 µg/dL; 118.02-687.96 nmol); ACTH, 0.91 pg/mL (0.02 pmol/L; normal reference range, 7.28-63.26 pg/mL; 0.16-1.39 pmol/L); fasting blood glucose, 89.82 mg/dL (4.99 mmol/L; normal reference range, 70.2-109.8 mg/dL; 3.9-6.1 mmol/L); K, 3.62 mEq/L (3.62 mmol/L; normal reference range, 3.5-5.5 mEq/L; 3.5-5.5 mmol/L). Visual acuities at the time of presentation were 0.8 in the LE and 0.7 in the RE. OCT showed regression of serous retinal detachments in the RE (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The retinal neuroepithelial layer has returned to normal, with a retinal thickness of 262 μm at the fovea of the macula.

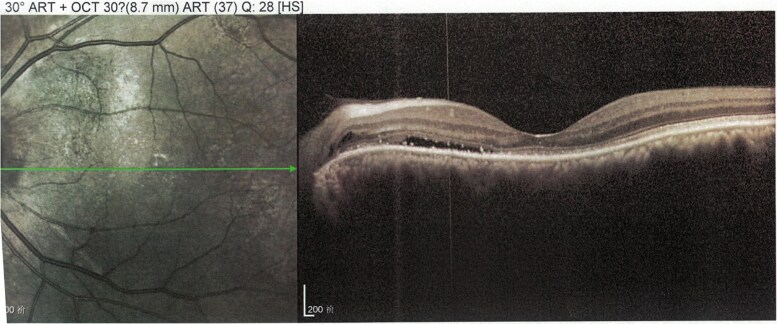

Case 2

Three months after surgery, blurred vision symptoms improved. OCT revealed significant improvement in SRF compared with the preoperative status (Fig. 6). BCVA improved to 0.4 in the LE and 0.7 in the RE. In this case, drugs targeting CSC were not used; however, exogenous corticosteroids were discontinued. The patient monitored his thyroid function after discharge. Laboratory data revealed the following: FT3, 2.79 pg/mL (4.30 pmol/L; normal reference range, 2.27-2.69 pg/mL; 3.5-6.5 pmol/L); FT4, 7.97 pg/mL (10.36 pmol/L; normal reference range, 8.85-17.46 pg/mL; 11.5-22.7 pmol/L); and TSH, 2.558 µIU/mL (2.558 mIU/L) (normal reference range, 0.55-4.78 µIU/mL; 0.55-4.78 mIU/L), with TRAb, 11.81 U/L (normal reference range, ≤ 1.75 U/L), and methimazole dosage was reduced to 5 mg once a day.

Figure 6.

Discontinuing exogenous corticosteroid for 4 months, optical coherence tomography images at presentation showing improvement in subretinal fluid.

Discussion

CSC has been considered an initial presenting symptom of CS [4, 5]. To date, only 16 cases of CS combined with CSC have been reported [6-18]. In these cases (Table 3), the onset age ranged from 28 to 65 years, with a female predominance (12/16). Among them, 9 cases were caused by pituitary adenomas [7-10, 13, 16, 17], 4 by adrenal cortical adenomas [6, 11, 12, 14], and 1 each by adrenal nodular hyperplasia [7], adrenal cortical adenocarcinoma [15], and adrenal myeloid lipoma [18]. In terms of treatment, except for one case of death due to adrenal cortical adenocarcinoma, CSC symptoms and fundus features resolved after eliminating the causes (pituitary microadenoma resection or adrenal adenoma resection). A case of CSC associated with adrenal cortical adenomas, similar to case 1, has been described, with CSC as a presenting symptom of CS [11]. Bouzas et al [19] reported CSC development in 60 patients with CS, with 5% having 1 or more CSC episodes identified by ophthalmologic examination. CSC occurred during active CS with high plasma cortisol levels. Abalem et al [20] enrolled 11 patients with active CS and 12 healthy controls and found increased choroidal thickness in patients with active CS compared with controls (372.96 ± 73.14 vs 255.63 ± 50.70 µm), and 18.18% of patients experienced macular changes, possibly secondary to choroidal thickening. These results are generally consistent with those reported by Brinks and colleagues [21]. Therefore, ophthalmologists should consider CSC when patients with CS complain of blurred vision, and hormone levels must be evaluated to exclude an underlying endocrine disease.

Table 3.

Literature review of Cushing syndrome associated with central serous chorioretinopathy

| Author and reference | Age, y | Sex | Location of retinal lesions | Cortisol level | Location diagnosis | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soares et al [6] | 50 | Female | Right eye | Serum cortisol-, ACTH↓ and abnormal dexamethasone suppression test | Adrenal cortical adenomas | After undergoing minimally invasive adrenalectomy, SRF disappeared |

| van Dijk et al [7] | 56 | Male | Both eyes | Hypercortisolism | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal of pituitary microadenoma, no recurrence of serous SRF occurred |

| van Dijk et al [7] | 49 | Female | Both eyes | CS | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal adenectomy, visual symptoms and SRF did not recur |

| van Dijk et al [7] | 37 | Female | Left eye | ACTH-dependent CS | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal adenectomy, serous SRF was absent |

| van Dijk et al [7] | 49 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH-independent CS | Adrenal nodular hyperplasia | After undergoing bilateral adrenalectomy, no serous SRF was present |

| Buelens and Dewachter [8] | 65 | Female | Left eye | Serum ACTH-, 24-h urinary free cortisol↑, morning serum cortisol↑, failure to suppress morning cortisol secretion after overnight low dose of dexamethasone | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal tumor resection, visual acuity recovered and CSC regressed |

| Giovansili et al [9] | 53 | Female | Both eyes | Serum ACTH-, 24-h urinary free cortisol↑, morning cortisol was nonsuppressed with low-dose dexamethasone (1-mg DST) | Pituitary adenomas | Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery was performed, visual acuity was recovered, and no retinal serous detachments existed |

| Wang and Saha [10] | 49 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH↑, nonsuppressed morning cortisol with 1-mg dexamethasone, 24-h urinary free cortisol↑ | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal adenectomy, visual acuity recovered and CSC regressed |

| Iannetti et al [11] | 45 | Male | Left eye | ACTH↓, 24-h urinary free cortisol↑, morning cortisol was nonsuppressed with low-dose dexamethasone (1-mg DST) and high-dose dexamethasone (8-mg DST) | Adrenal cortical adenomas | After undergoing right laparoscopic adrenalectomy, SRF disappeared and visual acuity improved |

| Pastor-Idoate et al [12] | 28 | Male | Both eyes | ACTH↓, 24-h urinary free cortisol↑, morning cortisol was nonsuppressed with low-dose dexamethasone (1-mg DST) and high-dose dexamethasone (8-mg DST) | Adrenal cortical adenomas | After undergoing left laparoscopic adrenalectomy, visual acuity improved and RPE resolved |

| Clarke et al [13] | 64 | Male | Left eye | Morning serum cortisol↑ | Pituitary adenomas | Patient received postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery to residual tumor, vision recovered, intraretinal edema and SRF resolved |

| Takkar et al [14] | 42 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH↓, no change in serum cortisol levels following low-dose dexamethasone suppression test | Adrenal cortical adenomas | After undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy, CSC resolved |

| Thoelen et al [15] | 54 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH↓, serum cortisol↑, urinary free cortisol↑, 17-hydroxysteroids and 17-ketosteroids ↑ | Adrenal cortical adenocarcinoma | Despite total adrenalectomy, patient died of sepsis |

| Appa [16] | 42 | Female | Both eyes | 24-h urinary free cortisol↑, low-dose and high-dose dexamethasone suppression test both failed to suppress serum cortisol level | Pituitary adenomas | Transsphenoidal endoscopic excision of pituitary microadenoma, recovery of vision, and CSC has not been explained |

| Liu Y et al [17] | 58 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH↑, plasma cortisol level↑ | Pituitary adenomas | After undergoing transsphenoidal adenectomy, visual acuity recovered |

| Liu L et al [18] | 44 | Female | Both eyes | ACTH↓, plasma cortisol level↑, urinary 17-hydroxycorticosteroids failed to be suppressed by 8-mg dexamethasone | Adrenal myeloid lipoma | Left adrenalectomy was performed and visual acuity improved |

Abbreviations: -, normal range; ACTH, adrenocorticotropin hormone; CS, Cushing syndrome; CSC, central serous chorioretinopathy; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SRF, subretinal fluid.

The use of exogenous corticosteroids is similarly the most recognized risk factor for CSC. Through a meta-analysis, Ge et al [22] found that administration of several forms of exogenous corticosteroids appeared to be associated with an increased risk (odds ratio [OR] 4.050; 95% CI, 2.270-7.220). In case 2, CSC initially developed after intravenous GC therapy, which improved after discontinuing corticosteroids. However, CSC was aggravated after receiving peribulbar injections of TA. Imasawa and colleagues [23] reported a similar case of presumed intravitreal TA-associated CSC in a 59-year-old female patient who had been treated with TA particles during vitrectomy to reduce macular edema. The use of corticosteroids was temporally associated with acute CSC, with patients experiencing complete resolution of CSC during a follow-up period of 2 months. The case published by Kocabora et al [24] involved a 42-year-old male patient who had been treated with intravitreal TA injection. Before exacerbating CSC, he had used TA 4 mg/0.1 mL for 3 weeks, and he experienced CSC resolution during a follow-up period of 6 months. A thick choroid is considered a risk factor for CSC development. Araki et al [25] reported that the choroidal thickness in patients with steroid-induced CSC was thicker than that in patients with idiopathic CSC; steroids can cause CSC through an effect on choroidal vessels and an impairment of RPE. The variant of complement factor H rs800292 A allele was associated with subfoveal choroidal thickness in normal participants [26]. Yoneyama et al [27] found a higher female predominance among steroid users than among nonsteroid users. Schellevis et al [28] observed high levels of androsterone, estrone, etiocholanolone, and androstenedione in patients with CSC compared with controls.

The etiological and pathophysiological link between corticosteroids and CSC has not been clear enough; however, possible mechanisms have been proposed. CSC development is found to be related to the abnormalities in choroidal circulation and alterations in the permeability of choroidal blood vessels. Corticosteroids have been hypothesized to inhibit collagen synthesis and increase choriocapillaris fragility and permeability, resulting in the decompensation of the choroidal circulation and accumulation of SRF. Corticosteroids are also thought to cause local ischemia by reducing choroidal fibrinolysis and leading to active pigment epithelial leakages or pigment epithelial detachment, resulting in SRF accumulation [22].

Although we cannot prove causality between CSC development and the use of endogenous hypercortisolism or exogenous corticosteroids, the spontaneous resolution of SRF following the discontinuation of corticosteroid therapy is very suggestive. Physicians should be cautioned that patients with CS or those who received high-dose steroid therapy are at risk of CSC.

Learning Points

CSC can be the main manifestation of unrecognized CS.

Ophthalmologists should maintain a high level of suspicion for clinical signs of CS in patients with CSC.

Exogenous corticosteroid usage is the most recognized risk factor for CSC.

The spontaneous resolution of SRF accumulation following corticosteroid withdrawal is highly indicative.

Patients with CS or those who received high-dose steroid therapy are at risk of CSC.

Contributors

All authors made individual contributions to authorship. K.C. and Qi Ni were involved in the diagnosis and management of the patient and manuscript submission and manuscript conceptualization. B.P. and Qing Ni were involved in preparation of the case report and literature review and manuscript writing and submission. Y.J.W. was involved in reviewing the patient chart, collecting data, and preparation of histology images. J.M.B. was involved in manuscript reviewing, revision, and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropin hormone

- BCVA

best-corrected visual acuity

- BP

blood pressure

- CS

Cushing syndrome

- CSC

central serous chorioretinopathy

- CT

computed tomography

- DST

dexamethasone suppression test

- FT3

free triiodothyronine

- FT4

free thyroxine

- GC

glucocorticoid

- GO

Graves orbitopathy

- LE

left eye

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- RE

right eye

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- SRF

subretinal fluid

- TA

triamcinolone acetonide

- TRAb

thyrotropin receptor antibody

- TSH

thyrotropin

Contributor Information

Bing Pang, Department of Endocrinology, The First Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China; Department of Endocrinology, Guang’anmen Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing 100054, China.

Qing Ni, Department of Endocrinology, Guang’anmen Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing 100054, China.

Ya-jing Wang, Department of Endocrinology, The First Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Jian-ming Ba, Department of Endocrinology, The First Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Qi Ni, Department of Endocrinology, The First Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Kang Chen, Department of Endocrinology, The First Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Youth Science Fund Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82104832) and the Special program for excellent scientific personnel training of the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (ZZ13-YQ-032) and The Escort Project of Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Science-Backbone Talent Cultivation Project (93230068).

Disclosures

None declared.

Informed Patient Consent for Publication

Signed informed consent could not be obtained from the patients or proxies but has been approved by the treating institution.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Daruich A, Matet A, Dirani A, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: recent findings and new physiopathology hypothesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;48:82‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsai DC, Chen SJ, Huang CC, et al. Epidemiology of idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy in Taiwan, 2001-2006: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rim TH, Kim HS, Kwak J, Lee JS, Kim DW, Kim SS. Association of corticosteroid use with incidence of central serous chorioretinopathy in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(10):1164‐1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fung AT, Yang Y, Kam AW. Central serous chorioretinopathy: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;51(3):243‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Haalen FM, van Dijk EHC, Dekkers OM, et al. Cushing syndrome and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soares RR, Samuelson A, Chiang A. Association of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy with subclinical cushing syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2022;26:101455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Dijk EH, Dijkman G, Biermasz NR, van Haalen FM., Pereira AM, Boon CJF. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy as a presenting symptom of cushing syndrome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016;26(5):442‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buelens T, Dewachter A. Bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy associated with endogenous cushing syndrome. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38(4):e73‐e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giovansili I, Belange G, Affortit A. Cushing disease revealed by bilateral atypical central serous chorioretinopathy: case report. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(5):e129‐e133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang BZ, Saha N. Bilateral multifocal central serous chorioretinopathy in endogenous hypercortisolism. Clin Exp Optom. 2011;94(6):598‐599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iannetti L, Spinucci G, Pesci FR, Vicinanza R, Stigliano A, Pivetti-Pezzi P. Central serous chorioretinopathy as a presenting symptom of endogenous cushing syndrome: a case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(5):661‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pastor-Idoate S, Peña D, Herreras JM. Adrenocortical adenoma and central serous chorioretinopathy: a rare association? Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2(3):327‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke C, Smith SV, Lee AG. A rare association: cushing disease and central serous chorioretinopathy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(2):e77‐e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takkar B, Temkar S, Gaur N, Venkatesh P. Central serous retinopathy as presentation of an adrenal adenoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11(1):e227315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thoelen AM, Bernasconi PP, Schmid C, Messmer EP. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with a carcinoma of the adrenal cortex. Retina. 2000;20(1):98‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Appa SN. Subclinical hypercortisolism in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2014;8(4):310‐313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Y, Liu X, Liu YM. A case of cushing syndrome with central serous chorioretinopathy as the first diagnosis in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology in China. 2022;31(5):399‐400. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu L, Yang F, Zhang RL, Zhang SN, Chen GH. One case report of combined central serous chorioretinopathy and cushing syndrome associated with adrenal myelolipoma. Fudan Univ J Med Sci. 2011;38(4):372‐374. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bouzas EA, Scott MH, Mastorakos G, Chrousos GP, Kaiser-Kupfer MI. Central serous chorioretinopathy in endogenous hypercortisolism. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(9):1229‐1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abalem MF, Machado MC, Santos HN, et al. Choroidal and retinal abnormalities by optical coherence tomography in endogenous cushing syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brinks J, van Haalen FM, van Rijssen TJ, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in active endogenous cushing syndrome. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge G, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Zhang M. Corticosteroids usage and central serous chorioretinopathy: a meta-analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(1):71‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Imasawa M, Ohshiro T, Gotoh T, Imai M, Iijima H. Central serous chorioretinopathy following vitrectomy with intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for diabetic macular oedema. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83(1):132‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kocabora MS, Durmaz S, Kandemir N. Exacerbation of central serous chorioretinopathy following intravitreal triamcinolone injection. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(12):1783‐1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Araki T, Ishikawa H, Iwahashi C, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy with and without steroids: a multicenter survey. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0213110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hosoda Y, Yoshikawa M, Miyake M, et al. CFH and VIPR2 as susceptibility loci in choroidal thickness and pachychoroid disease central serous chorioretinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(24):6261‐6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoneyama S, Fukui A, Sakurada Y, et al. Genetic and clinical characteristics of central serous chorioretinopathy with steroid use. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schellevis RL, Altay L, Kalisingh A, et al. Elevated steroid hormone levels in active chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(10):3407‐3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.