Abstract

Though thioamides are considered weaker hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides, recent calculations suggest they can enhance hydrogen bonds within the backbone of individual β-strands. We confirm this prediction through spectroscopic analysis of minimal amino-acid models. Further, incorporation of thioamides into the backbone of β-hairpin models highlights opportunities to control β-strand stability.

Graphical Abstract

Successful peptide/protein therapeutics and biotechnologies require precise control of three-dimensional conformation; strategies for doing so remain the subject of intense research.1, 2 An important unrealized goal is the control of secondary structure without sacrificing side-chain functionality. For example, whereas crosslink “staples” can enforce common secondary structures,3–7 they require covalent reaction of amino-acid side chains that might otherwise be repurposed for target engagement or derivatization. Manipulation of the protein backbone is therefore an attractive target for optimizing peptidomimetics. Given that the protein backbone is organized largely by hydrogen bonds between amides,8 a general strategy for controlling protein conformation would be to modify these groups to alter their hydrogen-bonding propensities.

Among amide-bond isosteres that can perturb hydrogen bonding,9 the thioamide has emerged as a particularly useful substitution10–22 because it retains the amidic resonance, planarity, and number of hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors natively present in backbone amides. Despite those commonalities, thioamides are stronger hydrogen-bond donors due to their lower pKa relative to oxoamides.23 This has been exploited in a limited number of cases to impart thermostability to structured peptides.14, 17, 24, 25 Conversely, most studies involving peptides indicate that thioamides are weaker hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides due to less negative charge on the chalcogen.9, 26 Indeed, incorporation of thioamides into peptides is often destabilizing when the thioamide serves as a hydrogen-bond acceptor.14, 27

For example, incorporating a thioamide into a polyalanine-based α-helix25 or at the N terminus of an α-helix in calmodulin14 both dramatically destabilized the protein, which both groups attributed to disruption of backbone hydrogen bonds by the reduced hydrogen-bonding capacity of the thiocarbonyl hydrogen-bond acceptor. Similar results have been observed in β-sheets.11, 14, 27 For example, incorporation of thioamides in central positions within the TrpZip β-hairpin,27 a cyclic β-sheet model,11 or the β-sheet of GB1,14 similarly reduced thermal stability, which was attributed in part to the thioamide’s reduced capacity to accept hydrogen bonds. Incorporating a thioamide as a hydrogen-bond acceptor was also extremely destabilizing to the folding of collagen-mimetic peptides,14 in part due to disruption of key inter-strand hydrogen bonds. Incorporation of thioamides as hydrogen-bond acceptors into peptides with a wide variety of structures therefore consistently reduces thermal stability, consistent with the reduced capacity of the thiocarbonyl to accept hydrogen bonds.9, 26

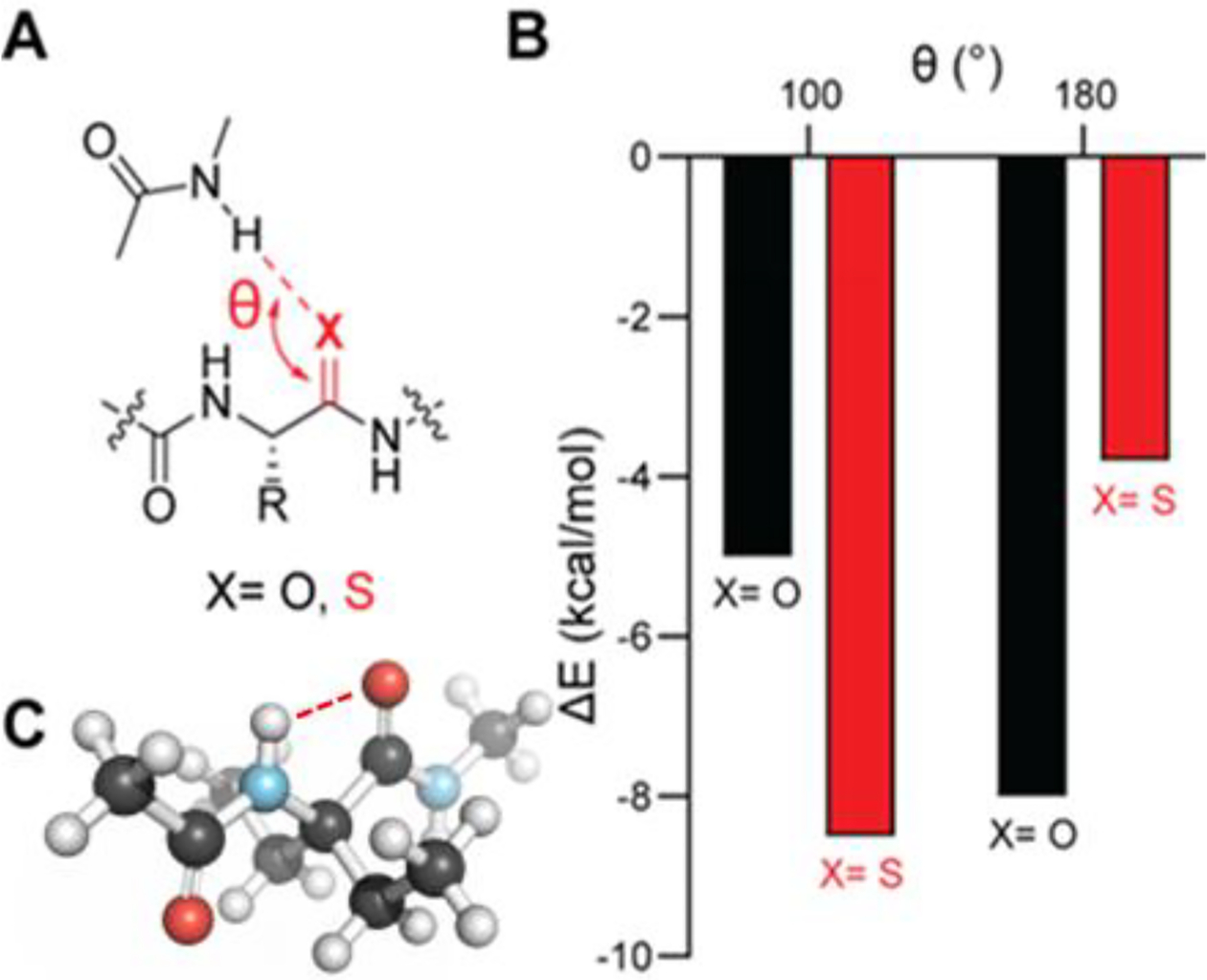

In contrast, Lampkin and VanVeller recently predicted computationally that thioamides might actually be stronger hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides in cases where the hydrogen-bond donor approaches at 90–100° relative to the carbonyl bond axis (Figure 1A/B).28 A prominent example of this hydrogen-bonding geometry is the C5 conformation of the peptide backbone (Figure 1C), which has been observed repeatedly in synthetic molecules,29, 30 but was only recently implicated in the structures of native proteins.31–33 This conformation is stabilized in part by hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen and amide proton of the same residue (Figure 1C). Despite the distorted angle between the donor bond axis and the acceptor, close contact between these atoms allows for stabilizing delocalization of the p-type carbonyl lone pair into the σ* orbital of N–H bond.31 C5 hydrogen bonds likely bias individual amino-acid residues toward the β-strand conformation, so enhancement of these interactions could aid in the development of β-strand mimetics.31 Such molecules might find application in targeting proteases, PDZ domains, bacterial membrane proteins, and even misfolded proteins, wherein a variety of amino-acid sequences form self-associating β-strands.34 Unfortunately, there are no methods currently available to selectively enhance C5 hydrogen bonds as a means to stabilize β-strands.

Figure 1.

(A) Hydrogen-bond geometry in peptide models. (B) Previously computed hydrogen bond energies28 for oxoamide and thioamide acceptors as a function of the angle of approach of the donor relative to the carbonyl bond axis (θ). (C) Molecular model of the solution conformation of diethylglycine derivatives established previously by NMR spectroscopy.31

We therefore sought to test experimentally if the distinct electronic distribution in thioamides can enhance C5 hydrogen bonds. To do so, we first synthesized thioamide-substituted derivatives of diethylglycine (Deg). Previous crystallographic and spectroscopic investigations demonstrate that diethylglycine derivatives robustly adopt the C5 geometry due to the steric repulsion between the gem-diethyl groups.35, 36 Diethylglycine derivatives are therefore excellent unique minimal models for studying interactions within individual β-strands, wherein the peptide backbone adopts an extended conformation. We also synthesized thioamide-substituted glycine (Gly) derivatives, which lack the preorganization of diethylglycine and therefore do not significantly populate the C5 geometry, allowing us to control for through-bond effects of thioamide incorporation independent of hydrogen bonding.

To compare the strengths of the hydrogen bonds in these molecules, we first recorded the chemical shift of the donor proton in solvents of differing polarity (i.e., DMSO-d6 and CDCl3). Hydrogen bonds insulate the donor proton from chemical shift changes due to solvent, so if thioamides are stronger C5 hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides, there should be a smaller chemical shift perturbation of the donor in the presence of a thioamide than in the presence of the corresponding oxoamide. To prevent confounding effects from intermolecular association, we performed these experiments at a concentration of 10 mM, where previous research has shown invariance of chemical shift with concentration, indicating a predominantly monomeric population.31, 36 Indeed, upon switching from DMSO-d6 to CDCl3, the C5 hydrogen-bond donor shifted only 0.23 ppm in the presence of the thioamide acceptor, whereas the corresponding proton shifted nearly twice as much (0.45 ppm) in the presence of an oxoamide (Figure 2A). In contrast, solvent-induced chemical shift changes of hydrogen-bond donors in the corresponding glycine derivatives were nearly indistinguishable (1.83 ppm for AcGlyNH2 vs 1.75 ppm for AcGlySNH2; Figure 2B). Thioamides therefore protect hydrogen-bond donors from solvent more effectively than oxoamides, but only in the C5 geometry, consistent with our hypothesis that thioamides are stronger C5 hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides.

Figure 2.

Change in chemical shift of amide protons of (A) AcDegNH2, AcDegSNH2, and AcDegOMe or (B) AcGlyNH2 and AcGlySNH2 between CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 solutions.

We considered the possibility that the increased protection of the donor proton imparted by thioamide results from desolvation of the molecule, since thioamides are less water soluble than oxoamides; however, substitution of the hydrogen-bond acceptor with an ester, which is also less well-solvated than an amide, instead causes a decrease in protection of the donor proton (Figure 2A).31, 37 Our results therefore cannot be explained solely by changes in solvation but rather require consideration of the hydrogen-bonding capacity of the participating functional groups.

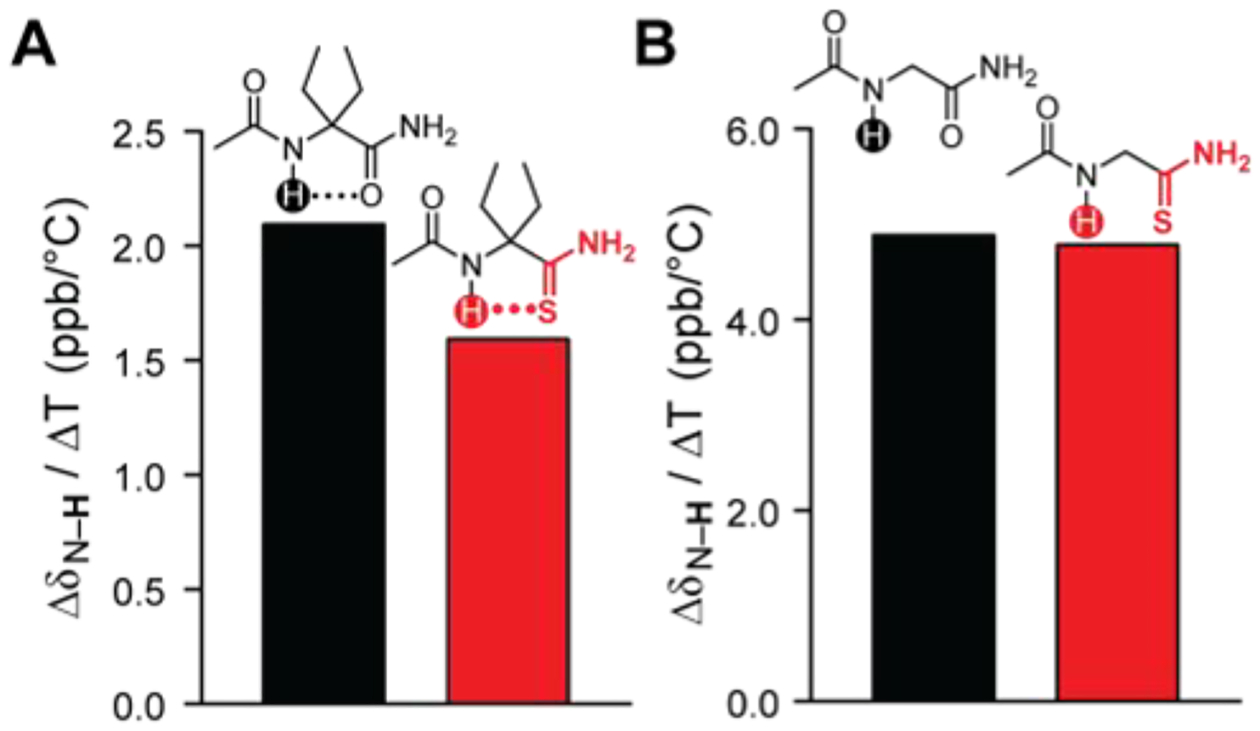

To further compare the capacity of amides and thioamides to accept C5 hydrogen bonds, we measured the sensitivity of hydrogen-bond donor chemical shifts to temperature. Hydrogen bonds insulate proton donors from chemical shift changes due to temperature,38, 39 so if thioamides are stronger C5 hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides, there should be a smaller chemical shift perturbation of the donor in the presence of a thioamide than in the presence of the corresponding oxoamide. Consistent with our studies of solvent effects (Figure 2), we observed that a thioamide was more effective as insulating the hydrogen-bond donor from chemical shift changes due to temperature than was the corresponding oxoamide (1.6 ppb/°C for AcDegSNH2 vs 2.1 ppb/°C for AcDegNH2; Figure 3A). Again, the stronger insulation provided by the thioamide required the C5 geometry, as the temperature-induced changes in donor chemical shift were indistinguishable in the corresponding glycine derivatives (4.9 ppb/°C for AcGlyNH2 vs 4.8 ppb/°C for AcGlySNH2; Figure 3B). Contrary to conventional belief that thioamides are weaker hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides, our data confirm the prediction of Lampkin and VanVeller that thioamides can be stronger hydrogen-bond acceptors when the donor approaches at an acute angle relative to the carbonyl bond axis,28 as is the case in prevalent C5 hydrogen bonds.31

Figure 3.

Change in chemical shift of amide protons of (A) AcDegNH2 and AcDegSNH2, or (B) AcGlyNH2 and AcGlySNH2 in DMSO-d6 upon increase in temperature from 30°C to 75°C.

These results suggest that thioamide incorporation might be a useful strategy for specifically enhancing hydrogen bonds within single β-strands by biasing individual residues toward the requisite dihedral angles. As a first test application for this strategy, we sought to stabilize minimal β-sheet models featuring isolated β-strand residues. Specifically, we synthetized backbone-modified variants of the tryptophan zipper (TrpZip2) β-hairpin (Figures 4 and 5A).40 With individual donors/acceptors exposed, we can isolate effects of thioamide substitution on intra-strand hydrogen bonds from confounding effects on canonical, cross-strand interactions.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional model (PDB: 1le1)40 and sequences of TrpZip2 peptides used in this study. Residues substituted with thioamides are highlighted in red.

Figure 5.

(A) Abbreviated chemical structures of TrpZip2 peptides. (B) Thermal denaturation of TrpZip2 peptides based on measurements of molar ellipticity at 228 nm.

We first evaluated the effects of incorporating a thioamide as a C5 hydrogen-bond acceptor. To do, we designed a pair of peptides with exposed hydrogen-bond acceptors (Figures 4 and 5A, TrpZip2-A and TrpZip2-B); thioamide incorporation into these molecules does not directly perturb any canonical, cross-strand interactions due to the lack of a cross-strand donor. In the absence of the cross-strand donor, we hypothesized two possible limiting outcomes. On the one hand, enhancing the C5 hydrogen bond could directly bias the terminal residue toward the β-strand conformation, thereby imparting additional thermal stability by increasing the total stabilizing enthalpy of the folded state relative to the unfolded state, which is likely to involve geometries that do not benefit from C5 interactions. Indeed, in previous studies, changes in the hydrogen-bonding capacity of a terminal residue without cross-strand interactions were sufficient to impart predictable changes in the overall thermal stability of the peptide. For example, increasing the acidity of a C5 hydrogen-bond donor was sufficient to increase the overall thermal stability of a β-hairpin, as evidenced by a change in its melting temperature.31 In contrast, enhancing the C5 hydrogen bond could create competition for the donor proton, which is simultaneously engaged in a canonical, cross-strand hydrogen bond that is critical for β-sheet stability.37 Put another way, donation of electron density from the thioamide hydrogen-bond acceptor could reduce the electrophilicity of the C5 hydrogen-bond donor, making it less effective at participating in cross-strand interactions.

Upon thermal denaturation of these molecules, we observed that incorporating a thioamide as the C5 hydrogen-bond acceptor was insufficient to stabilize secondary structure; if anything, the thioamide acceptor slightly lowered the thermostability of the peptide (Figure 5B; Tm = 66°C for TrpZip2-B vs Tm = 69°C for TrpZip2-A). To ensure that thioamide incorporation did not cause changes in the overall structure of the peptide, 1H–1H TOCSY and ROESY spectra of TrpZip2-A and TrpZip2-B were indistinguishable (Figure S1 and S2), indicating that thioamide incorporation did not change the overall fold of the peptide. Given that, we conclude that any direct stabilization of β-strand structure upon incorporating a thioamide as a C5 hydrogen-bond acceptor is likely offset by indirect effects on the strength of coincident cross-strand hydrogen bonds.

We next asked if thioamides could enhance C5 interactions when serving as the hydrogen-bond donor. Previous studies have consistently shown that thioamides are stronger hydrogen-bond donors than oxoamides in canonical hydrogen-bond geometries, so we expected the same trend in the C5 geometry. We therefore compared the thermostability of hairpins featuring an exposed C5 hydrogen-bond donor (Figures 4 and 5A, TrpZip2-C and TrpZip2-D). In this case, we observed that thioamide incorporation increased the thermostability of the hairpin (Figure 5B; Tm = 46°C for TrpZip2-D vs Tm = 41°C for TrpZip2-C), consistent with the lower pKa of the thioamide. We speculate that the effect of the thioamide as a hydrogen-bond donor was more predictable than its effects as a hydrogen-bond acceptor because sulfur incorporation has a larger effect on the capacity to act as a donor than as an acceptor. For example, previous studies show that a hydrogen bond donated by a thioamide is approx. 2 kcal/mol stronger than one donated by an oxoamide; in contrast, hydrogen bonds accepted by thioamides are weaker than those involving oxoamides by approx. 1.6 kcal/mol.26, 42, 43

In summary, we have demonstrated that, contrary to conventional wisdom, thioamides can be stronger hydrogen-bond acceptors than oxoamides, specifically in the case of highly local interactions like C5 hydrogen bonds. This stabilization occurs despite less partial negative charge on sulfur of a thioamide relative to the same charge on the oxygen of an oxoamide,10 suggesting greater charge-transfer character in the case of the thioamide, which is a stronger electron-pair donor.44 However, using thioamides to stabilize β-strand secondary structure through enhanced intra-strand hydrogen bonding appears to be complicated by potentially confounding interactions in the local microenvironment, such as through competition with canonical, cross-strand hydrogen bonds. Nevertheless, thioamides can enhance intra-strand hydrogen bonds when incorporated as the hydrogen-bond donor, suggesting strategies for conformational control of peptides and proteins.

Supplementary Material

NMR spectra, CD spectra, LC–MS traces

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the Welch Foundation (F2116) and the NIH (R00-NS116679, R35-GM160477).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang L; Wang N; Zhang W; Cheng X; Yan Z; Shao G; Wang X; Wang R; Fu C Therapeutic peptides: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newberry RW; Raines RT Secondary forces in protein folding. ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14, 1677–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoang HN; Driver RW; Beyer RL; Hill TA; D. de Araujo A; Plisson F; Harrison RS; Goedecke L; Shepherd NE; Fairlie DP Helix nucleation by the smallest known α-helix in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 8275–8279. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwell HE; Grubbs RH Highly efficient synthesis of covalently cross-linked peptide helices by ring-closing metathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1998, 37, 3281–3284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spokoyny AM; Zou Y; Ling JJ; Yu H; Lin Y-S; Pentelute BL A perfluoroaryl-cysteine SNAr chemistry approach to unprotected peptide stapling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5946–5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khakshoor O; Nowick JS Use of disulfide “staples” to stabilize β-sheet quaternary structure. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 3000–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams ZC; Silvestri AP; Chiorean S; Flood DT; Balo BP; Shi Y; Holcomb M; Walsh SI; Maillie CA; Pierens GK; Forli S; Rosengren KJ; Dawson PE Stretching peptides to generate small molecule β-strand mimics. ACS Cent. Sci 2023, 9, 648–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dill KA Dominant forces in protein folding. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 7133–7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhary A; Raines RT An evaluation of peptide-bond isosteres. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 1801–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh P; Raj N; Verma H; Patel M; Chakraborti S; Khatri B; Doreswamy CM; Anandakumar SR; Seekallu S; Dinesh MB; Jadhav G; Yadav PN; Chatterjee J An amide to thioamide substitution improves the permeability and bioavailability of macrocyclic peptides. Nat. Commun 2023, 14, 6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore KE; Patist MJ; Giannakoulias S; Huang C-H; Verma H; Khatri B; Cheng RP; Chatterjee J; Petersson EJ Structural impact of thioamide incorporation into a β-hairpin. RSC Chem. Biol 2022, 3, 582–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore KE; Phan HA; Robkis DM; Walters CR; Petersson EJ Incorporating thioamides into proteins by native chemical ligation. Methods Enzymol 2021, 656, 295–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahanta N; Szantai-Kis DM; Petersson EJ; Mitchell DA Biosynthesis and chemical applications of thioamides. ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14, 142–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walters CR; Szantai-Kis DM; Zhang Y; Reinert ZE; Horne WS; Chenoweth DM; Petersson EJ The effects of thioamide backbone substitution on protein stability: A study in α-helical, β-sheet, and polyproline II helical contexts. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 2868–2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersson EJ; Goldberg JM; Wissner RF On the use of thioamides as fluorescence quenching probes for tracking protein folding and stability. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2014, 16, 6827–6837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma H; Khatri B; Chakraborti S; Chatterjee J Increasing the bioactive space of peptide macrocycles by thioamide substitution. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 2443–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatri B; Raghunathan S; Chakraborti S; Rahisuddin R; Kumaran S; Tadala R; Wagh P; Priyakumar UD; Chatterjee J Desolvation of peptide bond by O to S substitution impacts protein stability. Angewandte Chemie 2021, 133, 25074–25078. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatri B; Bhat P; Chatterjee J Convenient synthesis of thioamidated peptides and proteins. J. Pept. Sci 2020, 26, e3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newberry RW; VanVeller B; Raines RT Thioamides in the collagen triple helix. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 9624–9627. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byerly-Duke J; VanVeller B Thioimidate solutions to thioamide problems during thionopeptide deprotection. Org. Lett 2024, 26, 1452–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J; Wang C; Xu S; Zhao J Ynamide-mediated thiopeptide synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 1382–1386. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C; Han C; Yang J; Zhang Z; Zhao Y; Zhao J Ynamide-mediated thioamide and primary thioamide syntheses. J. Org. Chem 2022, 87, 5617–5629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordwell FG Equilibrium acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution. Acc. Chem. Res 1988, 21, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miwa JH; Pallivathucal L; Gowda S; Lee KE Conformational stability of helical peptides containing a thioamide linkage. Org. Lett 2002, 4, 4655–4657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiner A; Wildemann D; Fischer G; Kiefhaber T Effect of thioxopeptide bonds on α-helix structure and stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 8079–8084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min BK; Lee H-J; Choi YS; Park J; Yoon C-J; Yu J-A A comparative study on the hydrogen bonding ability of amide and thioamide using near IR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct 1998, 471, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culik RM; Jo H; DeGrado WF; Gai F Using thioamides to site-specifically interrogate the dynamics of hydrogen bond formation in β-sheet folding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8026–8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampkin BJ; VanVeller B Hydrogen bond and geometry effects of thioamide backbone modifications. J. Org. Chem 2021, 86, 18287–18291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonora GM; Mapelli C; Toniolo C; Wilkening RR; Stevens ES Conformational analysis of linear peptides: 5. spectroscopic characterization of β-turns in AIB-containing oligopeptides in chloroform. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 1984, 6, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gellman SH; Adams BR Intramolecular hydrogen bonding in simple diamides. Tetrahedron Lett 1989, 30, 3381–3384. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newberry RW; Raines RT A prevalent intraresidue hydrogen bond stabilizes proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 1084–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher-Jones M; Glynn C; Boyer DR; Martynowycz MW; Hernandez E; Miao J; Zee C-T; Novikova IV; Goldschmidt L; McFarlane HT; Helguera GF; Evans JE; Sawaya MR; Cascio D; Eisenberg DS; Gonen T; Rodriguez JA Sub-ångström cryo-EM structure of a prion protofibril reveals a polar clasp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2018, 25, 131–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray KA; Evans D; Hughes MP; Sawaya MR; Hu CJ; Houk KN; Eisenberg D Extended β-strands contribute to reversible amyloid formation. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 2154–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson R; Sawaya MR; Balbirnie M; Madsen A; Riekel C; Grothe R; Eisenberg D Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 2005, 435, 773–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benedetti E; Barone V; Bavoso A; Di Blasio B; Lelj F; Pavone V; Pedone C; Bonora GM; Toniolo C; Leplawy MT; Kaczmarek K; Redlinski A Structural versatility of peptides from Cα,α-dialkylated glycines. i. A conformational energy computation and X-Ray Diffraction Study of homo-peptides from Cα,α-diethylglycine. Biopolymers 1988, 27, 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toniolo C; Bonora GM; Bavoso A; Benedetti E; Di Blasio B; Pavone V; Pedone C; Barone V; Lelj F; Leplawy MT; Kaczmarek K; Redlinski A Structural versatility of peptides from Cα,α-dialkylated glycines. II. an IR absorption and 1H-NMR study of homo-oligopeptides from Cα,α-diethylglycine. Biopolymers 1988, 27, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deechongkit S; Dawson PE; Kelly JW Toward assessing the position-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to beta-sheet folding thermodynamics employing amide-to-ester perturbations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 16762–16771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baxter NJ; Williamson MP Temperature dependence of 1H chemical shifts in proteins. J Biomol NMR 1997, 9, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dado PD; Gellman SH Structural and thermodynamic characterization of temperature-dependent changes in the folding pattern of a synthetic triamide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 4228–4245. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cochran AG; Skelton NJ; Starovasnik MA Tryptophan zippers: Stable, monomeric β-hairpins. PNAS 2001, 98, 5578–5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casanovas J; Revilla-López G; Crisma M; Toniolo C; Alemán C Factors governing the conformational tendencies of Cα-ethylated α-amino acids: Chirality and side-chain size effects. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 13297–13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alemán C On the ability of modified peptide links to form Hydrogen Bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 6717–6723. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee H-J; Choi Y-S; Lee K-B; Park J; Yoon C-J Hydrogen bonding abilities of thioamide. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 7010–7017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newberry RW; VanVeller B; Guzei IA; Raines RT n→π* interactions of amides and thioamides: Implications for protein stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 7843–7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.