Abstract

Selective androgen receptor modulators are currently not approved but are widely used in gyms. In the present study, the effects of ligandrol and its combination with endurance training on functional and clinically important parameters were studied in male healthy rats. Fourteen-week-old male rats were divided into four groups: two training (40 min, 5 times/week) and two non-training (5 min, 3 times/week). The velocity was 25 m/min at a track elevation of 5° for all groups. Ligandrol (0.4 mg/kg body weight, 5 times/week) was administered to one training and one non-training group and vehicle to the other groups (n = 10 per group) for 8 weeks. We conducted functional tests and examined morphometric, functional, hematological, hormonal, and clinical chemistry indicators in rats and histological and gene expression analyses in gastrocnemius muscle. Endurance training had a positive effect on all functional tests and increased vascular endothelial growth factor a (Vegf-a) gene expression. Ligandrol treatment reduced submaximal endurance, maximal oxygen consumption, concentrations of glucose, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone. It increased grip strength, triglycerides, and total cholesterol concentrations and had no effect on maximal sprinting speed, maximal time to exhaustion, hematological and morphometric parameters, and gene expression of myostatin and insulin-like growth factor 1. The negative effects of ligandrol treatment outweighed its benefits in this study. Endurance training alone had favorable effects, and its combination with ligandrol did not seem to have an advantage. In the training group, ligandrol decreased Vegf-a gene expression and the size of muscle fibers type I and IIa.

Keywords: Ligandrol, SARMs, Endurance, Testosterone, Submaximal training

Introduction

Non-steroidal selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) are molecules that exhibit weaker androgenic effects and pronounced anabolic effects known from the steroid group (Narayanan et al. 2008). Non-steroidal SARMs could improve the therapeutic process in primary and secondary hypogonadism, osteoporosis, various forms of cachexia, sarcopenia, or be used for male contraception or as hormone replacement therapy (Gao and Dalton 2007). Recent studies have reported antitumor properties of the non-steroidal SARM andarine (S-4) in the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 and in glioblastoma multiforme U87 and LN229 cell lines (Demircan et al. 2023; Yavuz and Demircan 2024). The group of non-steroidal SARMs does not yet have an approved therapeutic use (Mohideen et al. 2023), but they are available for purchase by anyone on the internet (Van Wagoner et al. 2017). Due to their pronounced anabolic effects on muscles, they are included in the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list of banned substances (Thevis and Schänzer 2018). The rising rate of positive doping tests due to the use of SARMs suggests that their illegal use among amateur and even professional athletes is increasing (World Anti-Doping Agency 2020). There are a number of known adverse effects of SARMs that can endanger the health of their users. For example, Kintz et al. (2021) described a case of rhabdomyolysis following the use of SARMs, and another case reported a bilateral Achilles tendon rupture in a male who used ostarine (Gould et al. 2021).

Although SARMs are often used by amateur bodybuilders, there is still insufficient data on their effects when used alone or in combination with training. In a recent study, the SARM ostarine reduced submaximal endurance and diminished the beneficial effects of exercise (Vasilev et al. 2024b). Another SARM, ligandrol (VK5211 or LGD-4033), has been evaluated in a few clinical trials with one of phase II, where it was well tolerated and improved lean body mass and muscle strength (Vignali et al. 2023). However, the effect of ligandrol applied with training in the healthy organism is not yet known. In the present study, we investigated ligandrol effect applied either alone or in combination with training on relevant morphometric, functional, clinical, hematological, and hormonal indicators and myogenic gene expression in healthy male rats.

Methods

Experimental animals

Fourteen-week-old male Wistar rats (n = 50) were used in the experiment. The rats were obtained from the vivarium of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Slivnitsa, Bulgaria. Body weight ranged from 160 to 200 g. Animals were accommodated in separate metabolic cages under 12/12-h light/dark cycle, 22–24 °C temperature, controlled humidity, and access to compound feed for rodents (AMIKO A Ltd., Belozem, Bulgaria) and water ad libitum. Weekly monitoring of body weight and food consumption was performed. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental protocol was authorized by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency (BFSA) (license #294) and the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Plovdiv Medical University.

Maintenance training regime

As treadmill training is a skill the experimental animals must learn, all rats ran on an EXER-3R treadmill for small laboratory animals (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) for 5 min per day, 3 days per week, for 2 weeks prior to the experiment at a belt speed of 25 m/min and a 5° slope. Those rats who did not acquire running skills were excluded from the experiment. Four experimental groups (n = 10 per group) of spontaneously running rats were formed: (1) sedentary vehicle-treated group (S + V), (2) sedentary ligandrol-treated group (S + Lg), (3) vehicle-treated training group (T + V), and (4) ligandrol-treated training group (T + Lg). The results of group S + V have already been partially published (Vasilev et al. 2024a, b).

The training rats were subjected to a maintenance training regime (Kazeminasab et al. 2013) on a treadmill for a period of 8 weeks. Five days a week, they ran at a treadmill speed of 25 m/min, 5° incline. On the first training day, the training session was 20 min and increased by 5 min every day to 40 min on day 5. As this is a maintenance training regime, the duration and speed of the exercise remained at this level until the end of the experiment (Kazeminasab et al. 2013). Rats from the sedentary groups were also exposed to training sessions but for 5 min 3 days a week to maintain running ability for participation in the functional tests. Two rats from the T + Lg group were withdrawn from the study because of illness.

Application of non-steroidal SARM

During the 8-week experimental period, rats in the S + Lg and T + Lg groups received subcutaneous (sc) injections of ligandrol (Hölzel Diagnostika Handels GmbH, Cologne, Germany) at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (Chimtex Ltd., Bulgaria) and polyethylene glycol 300 (PEG300) (Merck, Germany), five times a week. The other two groups received only a solution of PEG 300 and DMSO in equal volume and frequency (sc). The ligandrol dosage was based on the 5 mg dose found in products sold online (Van Wagoner et al. 2017) and was calculated using the dose conversion method between humans and animals (Nair and Jacob 2016).

Morphometric indicators

After 8-week treatments, just prior to decapitation, the length and abdominal circumference of the animals were measured. Length was measured as nose to anus distance of each rat. Calculations of body mass index (BMI) and Lee index were performed. We used the following formula to calculate BMI in rats: BMI = body mass (g)/(naso-anal distance (cm))2 (Wu-Peng et al. 1997). For the calculation of Lee index in rats, the formula was as follows: Lee index = body mass0.33 (g)/(naso-anal distance (cm))2 (Peralta et al. 2002). The heart, liver, right soleus muscle, and extensor digitorum longus muscle were weighed (n = 6 for each group) within 3 min after decapitation.

Submaximal endurance (SME)

Animals from all groups underwent the submaximal endurance test at the baseline and end of the experiment. SME was determined by running on a treadmill at a belt speed of 25 m/min and a 5° incline (which is approximately 70–75% of VO2max). Time to exhaustion and inability to sustain the position of the animal on the treadmill were registered (Georgieva et al. 2017).

Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max)

The Bedford VO2max test was conducted on all groups at the onset and end of the trial, after a 2-day recovery period (Bedford et al. 1979). The Oxymax small animal respiratory gas exchange system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) was used to determine oxygen consumption (VO2) during each exercise stage. The air delivery rate was 4.5 l/min. Prior to the examination, the O2 sensor was calibrated with a reference gas mixture, and the CO2 sensor was calibrated with pure nitrogen and a reference gas mixture. The protocol we applied involved a gradually increasing treadmill speed and elevation and was as follows: Stage I: 15 m/min, 5°; Stage II: 19 m/min, 10°; Stage III: 27 m/min, 10°; Stage IV: 27 m/min, 15°; Stage V: 30 m/min, 15°; Stage VI: 35 m/min, 15°; Stage VII: 40 m/min, 15° (Georgieva and Boyadjiev 2004). The duration of each step was 3 min. Before the start of the real exercise, each animal was positioned in the isolated chamber on the treadmill for a 10-min period. VO2 was recorded at each stage, and the maximum value measured was regarded as VO2max. VO2max was evaluated according to the Bedford criteria (Bedford et al. 1979). Rats were withdrawn from the trial when they had either reached a plateau or were fully fatigued and no longer could sustain their position on the treadmill.

Maximal time to exhaustion (MTE)

The MTE test was carried out in all groups at the onset and at the conclusion of the experiment. We used the same testing scheme as reported for the assessment of VO2max. The test was concluded when the rats were not capable of maintaining their position on the treadmill. The time required to reach this state was considered the maximal time to exhaustion (Georgieva and Boyadjiev 2004).

Grip strength

At the end of our study, to assess the grip strength of the rats, we used a grip strength meter (Ugo-Basile, Italy) to which a force transducer (dynamometer) was attached. Each rat was lifted so that its forelimbs could reach the test grid attached to the dynamometer. The rats were then gently dragged backwards on their tails until they were released from the grid. The maximum force generated by the rat before releasing was registered by the device and defined as grip strength. Three consecutive attempts were performed on each animal, consistent with other investigations. Grip strength was quantified as the highest value expressed relative to the body weight (gf/100 g BW) (Tchekalarova et al. 2022).

Maximal sprinting speed (MSS)

At the onset and at the conclusion of the study, all rats underwent the MSS test. The examination was conducted by running on a treadmill with an initial treadmill velocity of 25 m/min and a 5° incline for 3 min. The treadmill velocity was then raised to 45 m/min for 30 s, and then, the increase was gradually by 10 m/min every next 30 s. The test ended when it was no longer possible for the rats to sustain their position on the treadmill band. The highest velocity maintained by the rat over 15-s period was regarded as the maximal sprinting speed (Lambert 1990).

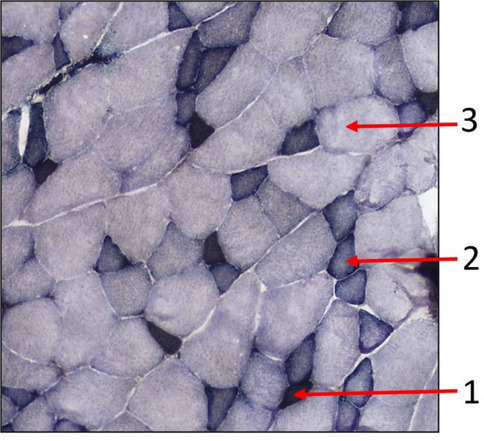

Histological analyses

Serial cross sections of 12-µm thickness were cut from the midpart of the gastrocnemius muscle at − 20 °C using a cryotome (CM 1900; Leica Microsystems, Wetzler, Germany) and stored at − 20 °C until staining. All chemicals were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany) unless otherwise stated. Muscle sections were fixed in a solution of 1% paraformaldehyde solution (pH 6.6), 1% CaCl2, and 6% sucrose and then stained by incubation in reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide diaphorase solution (pH 7.4), followed by acidic incubation (pH 4.2) and incubation in adenosine 5′-triphosphate solution (pH 9.4) (Horák 1983). Analysis was performed using a microscope at × 10 magnification (Eclipse E 600 microscope; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), a digital camera (DS-Fi2 Digital Camera; Nikon Instruments Europe, Amsterdam, Netherlands), and digital analysis software (NIS-Elements AR 4.0 imaging software; ikon Instruments Europe). Three randomly selected fields of 1 mm2 in the ATPase-stained sections were used for fiber evaluation. In these fields, 90 slow-twitch oxidative (type I), fast-twitch oxidative (type IIa), and 90 fast-twitch glycolytic (type IIb) fibers were circumscribed (Peter et al. 1972). The gastrocnemius muscle showed a relatively heterogeneous distribution of fiber types (Armstrong and Phelps 1984) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Section of gastrocnemius muscle from T + Lg group stained with ATPase staining. (1) Slow-twitch oxidative (type I) fibers, (2) fast-twitch oxidative (type IIa), and (3) fast-twitch glycolytic (type IIb)

Hematological and clinical chemistry indicators

After a 24-h fasting period, rats were decapitated and mixed blood was collected. An ADVIA 2120i hematology analyzer (Siemens, Germany) was used to determine the counts of erythrocytes (RBC), leukocytes (WBC), platelets (PLT), hemoglobin concentration (HGB), hematocrit level (Hct), and mean erythrocyte volume (MCV).

With the help of a clinical chemistry analyzer Konelab 60i (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland), serum concentrations of blood glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL (low-density lipoprotein), HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, and creatine kinase were measured accordingly manufacturer’s instructions.

Hormonal indicators

A Sirio Microplate Reader analyzer (SEAC, Italy) was used to determine the levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in serum. We employed sandwich enzyme immunoassay using two antibodies. The hormones from the samples were complexed with a polyclonal AT* (detection antibody) labeled with biotin and a solid phase-fixed antibody specific for rat hormones. HRP-streptavidin (SABC) was used to bind the AT-AG-AT* complex after washing to remove unbound proteins. Tetramethylbenzidine was used as a substrate to visualize the enzyme response following incubation and washing to remove unbound HRP-streptavidin. There were duplicate samples run. MyBioSource (San Diego, CA, USA) provided the kits.

Analysis of myogenic gene expression

The samples from gastrocnemius muscle (100 mg, n = 8 for each group) were homogenized in 750 µl TRIzol (Thermo Fischer Scientific, WA, USA) and 4-mm tungsten carbide beads (Cat. No. 69997 Qiagen, Germany) using the TissueLyser LT system (Qiagen, Germany). Samples were then incubated at room temperature for 5 min, followed by RNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Trizol, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Finally, the RNA pellet was dissolved in 20 µl H2O, quantified by a DeNovix DS-11 FX + system (DeNovix, NC, USA), and stored at − 80 °C. Reverse transcription was performed with 1000 ng total RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Biorad, CA, USA). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using SYBR Green (Biorad, CA, USA) and the CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Biorad, CA, USA). Gene expression of glycerinaldehyd-3-phosphat-dehydrogenase (Gapdh), myostatin (Mstn), insulin-like growth factor 1 (Igf-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor a (Vegf-a) was measured in triplicate, and the effects were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Ready-to-use primers for Gapdh, Igf-1, and Mstn were ordered from Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assays, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For Vegf-a, the following primers were used: forward CTTGTTCAGAGCGGAGAAAGC and reverse ACATCTGCAAGTACGTTCGTT (Gordon et al. 2010).

Statistical analysis

An ANOVA was performed to assess the main effects of ligandrol treatment (Lg) and submaximal endurance training (T) and their interactions. If the interaction between the two factors was significant, the Tukey or Games-Howell post-hoc test was used to assess differences between groups, depending on the homogeneity of variances (determined by Levene’s test). MTE, VO2max, MSS, and SME parameters were measured at the beginning and at the end of the experiment (two time points), and the factor time was included in the analysis of variance. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis of results was performed using SPSS v.19.0.

Results

Morphometric indicators

There was no effect of endurance training or of ligandrol on length, abdominal circumference, heart, liver, and extensor digitorum longus muscle weights, BMI, and Lee index (p > 0.05; ANOVA). The weight of the soleus muscle was higher in the trained animals than in non-trained rats (p < 0.05; ANOVA). The effect of ligandrol and the interaction between the factors were not significant for all morphometric indicators (p > 0.05; ANOVA) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphometric, clinical chemistry, and hematological indicators at the end of the experiment (mean ± SEM)

| Variable | Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (n = 19) | S (n = 19) | V (n = 19) | Lg (n = 19) | T vs. S | V vs. Lg | T × Lg | |

| Heart weight (g) | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.05 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | p = 0.771 | p = 0.624 | p = 0.519 |

| Liver weight (g) | 12.38 ± 0.49 | 12.67 ± 0.49 | 12.57 ± 0.49 | 12.48 ± 0.49 | p = 0.676 | p = 0.893 | p = 0.202 |

| Soleus muscle weight (g) | 0.169 ± 0.07 | 0.140 ± 0.07 | 0.163 ± 0.07 | 0.147 ± 0.07 | p = 0.006 | p = 0.110 | p = 0.931 |

| EDL muscle weight (g) | 0.182 ± 0.07 | 0.183 ± 0.07 | 0.181 ± 0.07 | 0.184 ± 0.07 | p = 0.862 | p = 0.728 | p = 0.488 |

| Body length (cm) | 21.2 ± 0.31 | 21.3 ± 0.31 | 21.3 ± 0.31 | 21.1 ± 0.31 | p = 0.749 | p = 0.749 | p = 0.212 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 17.1 ± 0.17 | 17 ± 0.17 | 17.2 ± 0.17 | 17 ± 0.17 | p = 0.497 | p = 0.434 | p = 0.793 |

| Lee index (g/cm2) | 0.33 ± 0.003 | 0.32 ± 0.003 | 0.32 ± 0.003 | 0.33 ± 0.003 | p = 0.128 | p = 0.128 | p = 0.191 |

| BMI (g/cm2) | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | p = 0.071 | p = 0.063 | p = 0.457 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.75 ± 0.07 | 1.72 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.07 | 1.95 ± 0.07 | p = 0.763 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.414 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | p = 0.098 | p = 0.608 | p = 0.114 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | p = 0.164 | p = 0.182 | p = 0.174 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | p = 0.299 | p = 0.011 | p = 0.464 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 6.13 ± 0.5 | 6.52 ± 0.5 | 7.04 ± 0.5 | 5.60 ± 0.5 | p = 0.621 | p = 0.074 | p = 0.868 |

| CK (U/l) | 8864 ± 1452 | 6907 ± 1452 | 7736 ± 1452 | 8034 ± 1452 | p = 0.338 | p = 0.884 | p = 0.306 |

| RBC (1012/l) | 8.5 ± 0.22 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.22 | 8.6 ± 0.22 | p = 0.533 | p = 0.179 | p = 0.386 |

| HGB (g/l) | 158.8 ± 4.6 | 158.6 ± 4.6 | 155.2 ± 4.6 | 162.2 ± 4.6 | p = 0.973 | p = 0.302 | p = 0.323 |

| Hct (l/l) | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | p = 0.531 | p = 0.939 | p = 0.791 |

| MCV (fl) | 53.4 ± 0.6 | 54.2 ± 0.6 | 54 ± 0.6 | 53.5 ± 0.6 | p = 0.374 | p = 0.592 | p = 0.705 |

| WBC (109/l) | 10.5 ± 0.86 | 10 ± 0.86 | 9.3 ± 0.86 | 11.2 ± 0.86 | p = 0.697 | p = 0.133 | p = 0.344 |

| PLT (109/l) | 735 ± 42.3 | 735 ± 42.3 | 676 ± 42.3 | 793 ± 42.3 | p = 0.999 | p = 0.055 | p = 0.577 |

T, training (groups T + V and T + Lg); S, sedentary (groups S + V and S + Lg); V, vehicle (groups S + V and T + V); Lg, ligandrol (groups S + Lg and T + Lg); T vs. S, main effect of training; V vs. Lg, main effect of ligandrol; T × Lg, interaction between the factors; (two-way ANOVA). The results of S were recently published in part (Vasilev et al. 2024a; Vasilev et al. 2024b)

Functional indicators

Maximal sprinting speed (MSS)

Time had a significant effect on MSS (p = 0.001; ANOVA). There was a significant interaction between time and training (p < 0.05; ANOVA) with the training animals having higher sprinting speed at the end compared to the beginning of the experiment (65 ± 1.5 m/min vs. 57 ± 1.5 m/min, p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc test). In sedentary rats, MSS did not change with the time (59.5 ± 1.4 m/min vs. 58 ± 1.4 m/min, p = 0.446; Tukey post-hoc test).

At the end of our study, endurance training had a significant impact with the training groups having higher MSS compared to the non-training groups (p < 0.01; ANOVA). The effect of ligandrol on MSS, as well as its interaction with training, was not significant (p > 0.05; ANOVA) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Functional, hormonal indicators, myogenic gene expression, and size of muscle fibers in gastrocnemius muscle at the end of the experiment (mean ± SEM)

| Variable | Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (n = 19) | S (n = 19) | V (n = 19) | Lg (n = 19) | T vs. S | V vs. Lg | T × Lg | |

| SME (min) | 53 ± 2.5 | 26 ± 2.5 | 46 ± 2.5 | 32 ± 2.5 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.003 |

| MTE (s) | 822 ± 17 | 627 ± 17 | 720 ± 17 | 729 ± 17 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.744 | p = 0.001 |

| VO2max (ml O2/kg/min) | 61.8 ± 1.1 | 58 ± 1.1 | 61.4 ± 1.1 | 58.4 ± 1.1 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.013 | p = 0.011 |

| MSS (m/min) | 65.2 ± 1.9 | 59.5 ± 1.9 | 64 ± 1.9 | 60.7 ± 1.9 | p = 0.006 | p = 0.109 | p = 0.263 |

| Grip strength (gf/100 g BW) | 119 ± 4.3 | 110 ± 4.3 | 109 ± 4.3 | 119 ± 4.3 | p = 0.041 | p = 0.030 | p = 0.003 |

| LH (mlU/ml) | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | p = 0.415 | p = 0.243 | p = 0.480 |

| FSH (ng/ml) | 21.9 ± 3.4 | 31.9 ± 3.4 | 30.6 ± 3.4 | 23.2 ± 3.4 | p = 0.007 | p = 0.039 | p = 0.282 |

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 10.4 ± 0.9 | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 7.6 ± 0.9 | p = 0.030 | p = 0.066 | p = 0.985 |

| Mstn myogenic expression | 1.25 ± 0.12 | 1.12 ± 0.12 | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 1.28 ± 0.12 | p = 0.432 | p = 0.251 | p = 0.217 |

| Vegf-a myogenic expression | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.15 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | p = 0.924 | p = 0.036 | p = 0.015 |

| Igf-1 myogenic expression | 1.15 ± 0.08 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 1.02 ± 0.08 | 1.17 ± 0.08 | p = 0.323 | p = 0.208 | p = 0.078 |

| Area of muscle fibers type I (µm2) | 1321 ± 83 | 1333 ± 83 | 1416 ± 83 | 1238 ± 83 | p = 0.882 | p = 0.039 | p = 0.469 |

| Diameter of muscle fibers type I (µm) | 40.3 ± 1.2 | 40.6 ± 1.2 | 41.9 ± 1.2 | 39 ± 1.2 | p = 0.820 | p = 0.028 | p = 0.450 |

| Area of muscle fibers type IIa (µm2) | 2493 ± 83 | 2552 ± 126 | 2683 ± 126 | 2363 ± 126 | p = 0.645 | p = 0.014 | p = 0.052 |

| Diameter of muscle fibers type IIa (µm) | 55.7 ± 1.3 | 56.3 ± 1.3 | 57.8 ± 1.3 | 54.2 ± 1.3 | p = 0.648 | p = 0.010 | p = 0.061 |

| Area of muscle fibers type IIb (µm2) | 5841 ± 268 | 5954 ± 268 | 6107 ± 268 | 5688 ± 268 | p = 0.675 | p = 0.123 | p = 0.442 |

| Diameter of muscle fibers type IIb (µm) | 85.6 ± 1.9 | 86.1 ± 1.9 | 87.6 ± 1.9 | 84.2 ± 1.9 | p = 0.812 | p = 0.089 | p = 0.402 |

T, training (groups T + V and T + Lg); S, sedentary (groups S + V and S + Lg); V, vehicle (groups S + V and T + V); Lg, ligandrol (groups S + Lg and T + Lg); T vs. S, main effect of training; V vs. Lg, main effect of ligandrol; T × Lg, interaction between the factors; (two-way ANOVA). The results of S were recently published in part (Vasilev et al. 2024a; Vasilev et al. 2024b)

Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max)

VO2max was significantly influenced by time (p < 0.01, ANOVA). There was a significant interaction between time and training (p = 0.01; ANOVA), with the trained rats having a greater maximal oxygen consumption at the end of the experiment compared to the beginning (61.8 ± 0.8 ml O2/kg/min vs. 57.7 ± 0.8 ml O2/kg/min, p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc test). Sedentary rats did not change their maximal oxygen consumption with the time (58.5 ± 0.7 ml O2/kg/min vs. 57.8 ± 0.7 ml O2/kg/min, p = 0.889; Tukey post-hoc test).

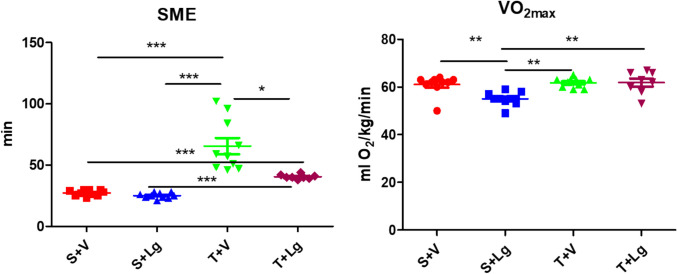

At the end of the experiment, the effect of endurance training on VO2max was significant. The training groups had a higher VO2max than the non-training groups (p < 0.01; ANOVA) (Table 2). Ligandrol administration affected VO2max significantly; the groups treated with SARM had lower VO2max than the vehicle-treated groups (p < 0.05; ANOVA) (Table 2). There was also a significant between-factor interaction (p < 0.05; ANOVA) (Table 2). Group S + Lg had a significantly lower VO2max than all other groups (Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SME and VO2max of the groups at the end of the experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Tukey post-hoc and Games-Howell tests). The result of group S + V was already published (Vasilev et al. 2024a, b)

Submaximal endurance (SME)

The SME was significantly influenced by the time (p < 0.001; ANOVA). Time and training interacted significantly (p < 0.001; ANOVA), with trained animals having a higher endurance at the end of the experiment than at the beginning (53 ± 1.9 min vs. 25 ± 1.9 min, p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc test). In non-training animals, there was no such improvement in SME with time (26 ± 1.9 min vs. 24.8 ± 1.9 min, p = 0.600; Tukey post-hoc test).

At the end of the study, ligandrol effect was significant, with the treated groups having lower SME than the vehicle groups (p = 0.001; ANOVA) (Table 2). Endurance training also had a significant effect, with the training groups having a higher SME than the non-training groups (p < 0.001; ANOVA) (Table 2). There was a significant interaction between the factors (p < 0.01; ANOVA) (Table 2). Group T + V had a significantly higher SME than all other groups. Group T + Lg had higher SME than S + Lg and S + V (Games-Howell post-hoc test) (Fig. 2).

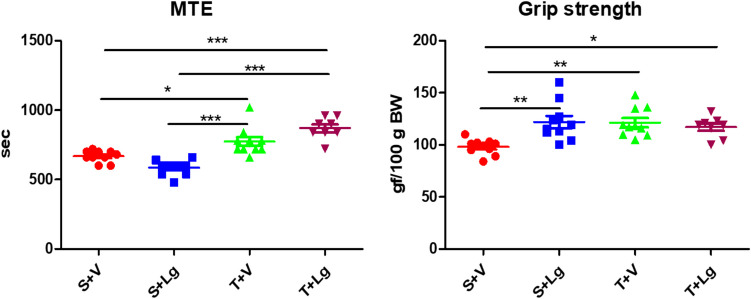

Maximal time to exhaustion (MTE)

MTE was significantly influenced by time (p < 0.001; ANOVA). Time and training interacted significantly (p < 0.001; ANOVA) with the trained rats having grater time to exhaustion at the end than the start of the experiment (822 ± 17 s vs. 591 ± 17 s, p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc test). Sedentary rats did not change their maximal time to exhaustion with the time (627 ± 16 s vs. 585 ± 16 s, p = 0.064; Tukey post-hoc test).

At the end of the study, ligandrol had no effect on MTE (p > 0.05; ANOVA) (Table 2). A significant effect of training was found, with training groups having higher MTE compared to non-training groups (p < 0.001; ANOVA) (Table 2). There was a significant interaction between the factors (p = 0.001; ANOVA) (Table 2). The T + V and T + Lg groups had a higher MTE than the S + Lg and S + V groups (Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Maximal time to exhaustion and grip strength of the groups at the end of the experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Tukey post-hoc and Games-Howell tests). The result of group S + V was already published (Vasilev et al. 2024a, b)

Grip strength

Ligandrol had a significant effect on grip strength, as the groups treated with it had increased grip strength (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). Endurance training also had a significant effect, with the training groups having greater grip strength than the non-training groups (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). There was also a significant inter-factor interaction (p = 0.003; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2): groups S + Lg, T + V, and T + Lg had higher grip strength than group S + V (Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 3).

Hormonal indicators

In ligandrol-treated rats, there was a lower FSH concentration compared to vehicle-treated animals (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). An effect of endurance training was also found, with the trained groups having lower FSH concentrations compared to the non-trained groups (p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). There was no significant interaction between the factors (p > 0.05: two-way ANOVA) (Table 2).

Testosterone level was affected by the endurance training, with the training groups having a lower concentration compared to the non-training groups (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). Ligandrol-treated groups showed a trend towards lower testosterone level compared to the vehicle-treated groups (p = 0.066; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). There was no significant interaction between the factors (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2).

Neither training nor ligandrol administration affected LH concentration, and the interaction between these two factors was not significant (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2).

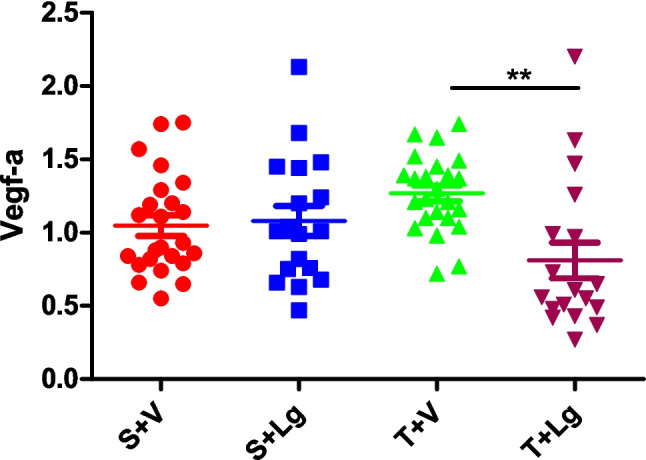

Myogenic gene expression in gastrocnemius muscle

Vegf-a expression was affected by ligandrol, with groups receiving the substance having lower expression than those receiving vehicle (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). There was no significant effect of training (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2), whereas the interaction between the factors was significant (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). Group T + V showed higher gene expression of Vegf-a compared to group T + Lg (Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Vegf-a myogenic gene expression of the groups at the end of the experiment. **p < 0.01 different to group T + Lg (Tukey post-hoc test). The result of group S + V was already published (Vasilev et al. 2024b)

Effects of ligandrol and training as well as their interaction were not significant regarding the expression of the Igf-1 and Mstn genes in gastrocnemius muscle (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2).

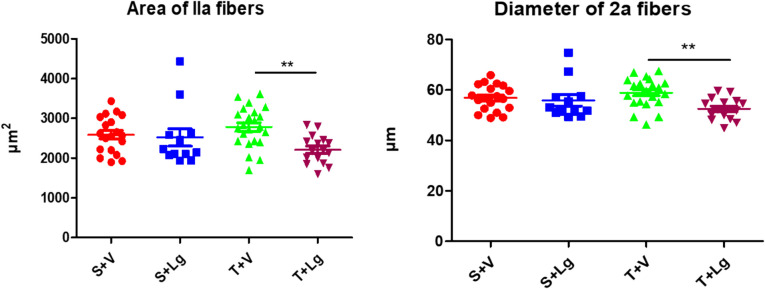

Muscle fiber analyses

Ligandrol treatment had a significant effect and lowered the area and diameter of gastrocnemius muscle fiber types I and IIa (p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2). There was a tendency for inter-factor interaction in IIa muscle fibers for both area and diameter (p = 0.052 and p = 0.061; two-way ANOVA). Group T + Lg had a significantly lower area and diameter compared to group (T + V) (Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 5). Ligandrol did not have any effects on muscle fibers type IIb (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA). Endurance training did not affect either the area or the diameter of any of the muscle fiber types in the gastrocnemius muscle (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Area and diameter of muscle fibers type IIa of the groups at the end of the experiment. **p < 0.01 T + V different to group T + Lg (Tukey post-hoc test)

Hematological indicators

The effects of ligandrol and training as well as their interaction were not significant for blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, and MCV values (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 1).

Clinical chemistry indicators

Ligandrol had a significant effect on the concentrations of cholesterol (p < 0.001) and triglycerides (p < 0.05) (two-way ANOVA), with the treated groups having higher concentrations compared to those receiving vehicle (Table 1). Glucose concentration had a trend towards lower values in ligandrol-treated rats compared to animals receiving vehicle (p = 0.074; two-way ANOVA) (Table 1). No significant effects of ligandrol (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) on the concentrations of HDL, LDL cholesterol, and creatine kinase were found. There was no significant effect of training and no significant inter-factor interaction for any of the clinical chemistry parameters examined (p > 0.05; two-way ANOVA) (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of ligandrol on maximal oxygen consumption and endurance. Ligandrol reduced VO2max, with this effect occurring only in non-training rats, whereas in training animals, submaximal exercise neutralized its effect. These data contrast with the lack of effect of another SARM, ostarine, on VO2max found in a previous study (Vasilev et al. 2024a). In another study, the SARM molecule, GTx-026, restored resting oxygen consumption to the level of sham-operated mice, which had been reduced after castration (Ponnusamy et al. 2017). However, after adjusting lean body mass, the differences between the groups were not significant, and the authors suggested that, apart from changes in lean body mass, there was no effect on energy expenditure (Ponnusamy et al. 2017). In our study, ligandrol did not significantly alter body weight in rats, similar to previous studies with ligandrol and ostarine (Roch et al. 2020; Vasilev et al. 2024b); thus, energy expenditure was independent of these parameters.

Higher levels of testosterone in male professional athletes are known to be associated with improved sprint performance (Bezuglov et al. 2023). In contrast to testosterone, ligandrol did not improve sprint performance in treated rats, which has been previously observed with the other SARM ostarine (Vasilev et al. 2024a). However, ligandrol increased grip strength in the sedentary group to a similar extent as training, whereas the combination treatment of ligandrol with training showed no synergistic effect over the single treatments. Similarly, other SARMs (GTx-026 and MK-4541) have also been reported to increase grip strength in mice (Chisamore et al. 2016; Ponnusamy et al. 2017).

Ligandrol reduced SME by delaying adaptive changes, but this effect occurred only under exercise conditions and was probably not due to the decreased VO2max, as the latter was observed only in untrained rats. It is known that SME is not only determined by VO2max but also by other factors (McArdle et al. 2010). The combined effect of endurance training and ligandrol was not stronger than the effect of training alone. Regarding MTE, ligandrol had no effect on either trained or untrained rats. The lack of effect of ligandrol on MTE and its pronounced effect on SME can be explained by the fact that the two parameters are determined by different factors (Davies et al. 1981; Lambert and Noakes 1989). Ostarine showed similar effects on SME and MTE indicators (Vasilev et al. 2024b).

Another observed effect of ligandrol was reduced Vegf-a gene expression in muscle which was only detected under training. This effect of ligandrol corresponds to the reported effect of the anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) nandrolone decanoate, which reduces myogenic gene expression and serum Vegf concentration in training rats (Paschoal et al. 2009). The trend we observed for higher Vegf-a expression in training rats is likely related to the known effect of exercise on increasing capillary density in skeletal muscles (Waters et al. 2004).

It is well known that type I fibers are the most important for muscle endurance (Wilson et al. 2012), and ligandrol treatment caused a decrease in the size of these fibers in our study. In the previous study, estrogen-deficient rats treated with ligandrol orally for a period of 5 weeks demonstrated no significant changes in fiber size (Roch et al. 2020). However, the potential factors that may impact the results differed from those considered in the present study. These include hormonal status, sex, the route of administration of ligandrol, and the duration of administration. The observed decrease in area and diameter of fiber types I and IIa under ligandrol treatment along with Vegf-a downregulation, which could lead to a reduction in capillary density, may provide insight into one of the mechanisms that could explain the decrease in SME by ligandrol in our study.

There are not enough studies available on the effect of SARMs on myogenic Igf-1 gene expression. The lack of the ligandrol effect in our experiment on healthy male rats is similar to another study, but in orchiectomized rats, where ostarine also had no effect on the Igf-1 gene expression in gastrocnemius muscle (Roch et al. 2022). Another non-steroidal SARM, S-23, increased Igf-1 expression, but in the levator ani muscle of 6-week-old orchiectomized rats (Jones et al. 2010). Thus, it appears that the effect of SARMs on Igf-1 expression may vary depending on the class of the SARMs, age of the animals, sex, and muscle site.

The myostatin gene is one of the most sensitive to the influence of androgens (Dubois et al. 2014). However, ligandrol did not alter its myogenic expression. In two other studies, ostarine was reported to attenuate castration-induced increased myostatin gene expression in rats (Hoffmann et al. 2022; Ponnusamy et al. 2016). There are controversial claims in the literature regarding the effect of exercise on myostatin. According to some authors, training decreases the serum concentration (Bagheri et al. 2020) and myogenic expression (Hittel et al. 2010) of myostatin. Other authors claim that several months of resistance training induce an increase in muscle expression of myostatin (Hulmi et al. 2007).

Serum analyses revealed the tendency of ligandrol to reduce serum glucose concentration which confirms the results of previous studies on ostarine (Dalton et al. 2011; Vasilev et al. 2024a). In our experiment, training did not significantly alter fasting serum glucose concentration. A study of healthy young men who engaged in 2 weeks of high-intensity exercise also reported no effect on glucose fasting concentration (Norton et al. 2012).

An increase in the serum concentration of total cholesterol was reported as an adverse effect of ostarine in a previous study (Vasilev et al. 2024a). This was also manifested with ligandrol in the present study, which additionally caused an increased concentration of triglycerides. Elevated levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol were also found in a male athlete who used ligandrol (Cardaci et al. 2022). Training in our experiment (70% of VO2max) did not affect the lipid profile of rats. Another study using an exercise intensity of 65% of VO2max also reported no effect on lipid profile indicators (Nybo et al. 2010). O’Donovan et al. compared two groups exercising at 60% and 80% of VO2max for 24 weeks. Significant improvements in lipid profile parameters were reported only in the higher training intensity group (O’Donovan et al. 2005). Thus, the lack of effect is expected given the short duration and lower intensity of training in our experiment.

The observed decrease in FSH and the tendency to decrease testosterone, without any effect on LH, confirm the results of two other studies also using ligandrol (Basaria et al. 2013; Cardaci et al. 2022). The decrease in total testosterone after ligandrol treatment did not correspond to the unchanged LH level. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of the ligandrol effect on testosterone concentration. The significant decrease in testosterone and the lack of effect on LH following the training applied in our experiment are in agreement with the results of other studies in rats (Dohm and Louis 1978) and in humans (Hackney 2008). The exercise-induced decrease in FSH described by us confirms the results obtained in women after 30 min of exercise (Bonen et al. 1979).

Ligandrol had no significant effect on any of the hematological parameters studied. A similar lack of effect on platelet count was reported in clinical cases of hepatotoxicity due to abuse of non-steroidal SARMs such as ligandrol, ostarine, and testolone (Bedi et al. 2021; Flores et al. 2020). In a study of patients treated with OPK-88004, authors reported an increase in hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit value, but no change in erythrocyte and leukocyte counts (Pencina et al. 2021). The lack of effect of ligandrol on soleus muscle weight is consistent with the results of a previous study in rats (Roch et al. 2020). In another study, S-4 also did not change the weight of soleus muscle (Gao et al. 2005). Similarly, the representative GSK-212A also had no effect on soleus muscle and extensor digitorum longus muscle weights after 4 weeks of treatment (Shankaran et al. 2016). Our study showed no effect of both ligandrol and training on the weight of the extensor digitorum longus muscle, body, heart, and liver, as well as on other morphometric indicators. In a previous experiment, ostarine caused a tendency to increase the weight of the heart and increase the synthesis of collagen around the arterial vessels of the myocardium, in non-exercising rats (Gerginska et al. 2022). A recent study reported that high doses of ostarine, in male fibroblastic myocardial cells, increased the concentration of two markers of fibrosis—α smooth muscle actin and fibronectin (Leciejewska et al. 2023).

A limitation of our study is that we did not measure plasma concentrations of liver enzymes (AST and ALT) or weigh male reproductive organs, despite the fact that these parameters can be affected by SARMs (Leciejewska et al. 2024). Another limitation of the present study is the lack of baseline measurement of some parameters such as grip strength and hematological, hormonal, and clinical chemistry indicators. Only one non-steroidal androgen receptor modulator (ligandrol) at a single dose was used for 8 weeks in this study. Longer studies with different representatives and doses of SARMs could provide additional information about the effects of these molecules. Future studies can examine the dose-dependent effects of SARMs when combined with training on a wider range of clinically important parameters.

Summarizing, ligandrol decreased submaximal endurance in training rats, lowered maximal oxygen consumption, and increased grip strength in sedentary rats. In muscle, ligandrol blunted the myogenic Vegf-a gene expression in training rats, decreased the area and diameter of type I and IIa muscle fibers, and lowered serum glucose concentration. It had negative effects on the lipid profile of rats by increasing the concentration of total cholesterol and triglycerides. Further, it reduced the concentrations of FSH and testosterone without showing effects on LH, hematological, and morphometric parameters. These potential effects should be taken into account when ligandrol is used. Endurance training neutralized the negative effect of ligandrol on VO2max and favorably enhanced myogenic Vegf-a gene expression. Combination of ligandrol with endurance training did not seem to have an advantage over the single application of these two treatments. Further studies are needed to clarify the effects of SARMs on other indicators of physical working capacity and their side effects with prolonged use.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to their colleagues, R. Castro-Machguth and K. Hannke (University Medical Center Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany), for their technical support.

Author contribution

K. G., N. B. and V. V. performed the experiment and the functional tests, D.A. carried out the hormonal and clinical chemistry studies, F. G. and S. D. carried out the morphometric studies, M. K., K. O. B. and A.F.S. performed the analysis of myogenic gene expression, K. G., V. V. and M.K. carried out statistical analyses, all authors helped draft the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare that all data were generated in-house and that no paper mill was used.

Funding

This work was supported by project HO – 06/2021 from Medical University of Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental protocol was authorized by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency (BFSA) (license #294) and the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Plovdiv Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Armstrong RB, Phelps RO (1984) Muscle fiber type composition of the rat hindlimb. Am J Anat 171(3):259–272. 10.1002/aja.1001710303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri R, Moghadam BH, Church DD, Tinsley GM, Eskandari M, Moghadam BH, Motevalli MS, Baker JS, Robergs RA, Wong A (2020) The effects of concurrent training order on body composition and serum concentrations of follistatin, myostatin and GDF11 in sarcopenic elderly men. Exp Gerontol 133:110869. 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basaria S, Collins L, Dillon EL, Orwoll K, Storer TW, Miciek R, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Eder R, Zientek H, Gordon G, Kazmi S, Sheffield-Moore M, Bhasin S (2013) The safety, pharmacokinetics, and effects of LGD-4033, a novel nonsteroidal oral, selective androgen receptor modulator, in healthy young men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68(1):87–95. 10.1093/gerona/gls078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford TG, Tipton CM, Wilson NC, Oppliger RA, Gisolfi CV (1979) Maximum oxygen consumption of rats and its changes with various experimental procedures. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 47(6):1278–1283. 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.6.1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi H, Hammond C, Sanders D, Yang HM, Yoshida EM (2021) Drug-induced liver injury from enobosarm (ostarine), a selective androgen receptor modulator. ACG Case Rep J 8(1):e00518. 10.14309/crj.0000000000000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezuglov E, Ahmetov II, Lazarev A, Mskhalaya G, Talibov O, Ustinov V, Shoshorina M, Bogachko E, Azimi V, Morgans R, Hackney AC (2023) The relationship of testosterone levels with sprint performance in young professional track and field athletes. Physiol Behav 271:114344. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonen A, Ling WY, MacIntyre KP, Neil R, McGrail JC, Belcastro AN (1979) Effects of exercise on the serum concentrations of FSH, LH, progesterone, and estradiol. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 42(1):15–23. 10.1007/BF00421100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardaci TD, Machek SB, Wilburn DT, Heileson JL, Harris DR, Cintineo HP, Willoughby DS (2022) LGD-4033 and MK-677 use impacts body composition, circulating biomarkers, and skeletal muscle androgenic hormone and receptor content: a case report. Exp Physiol 107(12):1467–1476. 10.1113/EP090741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisamore MJ, Gentile MA, Dillon GM, Baran M, Gambone C, Riley S, Schmidt A, Flores O, Wilkinson H, Alves SE (2016) A novel selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) MK-4541 exerts anti-androgenic activity in the prostate cancer xenograft R-3327G and anabolic activity on skeletal muscle mass & function in castrated mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 163:88–97. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, Hancock ML, Rodriguez D, Dodson ST, Morton RA, Steiner MS (2011) The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2(3):153–161. 10.1007/s13539-011-0034-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KJ, Packer L, Brooks GA (1981) Biochemical adaptation of mitochondria, muscle, and whole-animal respiration to endurance training. Arch Biochem Biophys 209(2):539–554. 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90312-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demircan T, Yavuz M, Bölük A (2023) Andarine plays a robust in-vitro anti-carcinogenic role on A549 cells through inhibition of proliferation and migration, and activation of cell-cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis. Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2776621/v1

- Dohm GL, Louis TM (1978) Changes in androstenedione, testosterone and protein metabolism as a result of exercise. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 158(4):622–625. 10.3181/00379727-158-40260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois V, Laurent MR, Sinnesael M, Cielen N, Helsen C, Clinckemalie L, Spans L, Gayan-Ramirez G, Deldicque L, Hespel P, Carmeliet G, Vanderschueren D, Claessens F (2014) A satellite cell-specific knockout of the androgen receptor reveals myostatin as a direct androgen target in skeletal muscle. FASEB J 28(7):2979–2994. 10.1096/fj.14-249748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores JE, Chitturi S, Walker S (2020) Drug-induced liver injury by selective androgenic receptor modulators. Hepatol Commun 4(3):450–452. 10.1002/hep4.1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Dalton JT (2007) Expanding the therapeutic use of androgens via selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs). Drug Discov Today 12(5–6):241–248. 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Reiser PJ, Coss CC, Phelps MA, Kearbey JD, Miller DD, Dalton JT (2005) Selective androgen receptor modulator treatment improves muscle strength and body composition and prevents bone loss in orchidectomized rats. Endocrinology 146(11):4887–4897. 10.1210/en.2005-0572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva KN, Boyadjiev NP (2004) Effects of nandrolone decanoate on VO2max, running economy, and endurance in rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36(8):1336–1341. 10.1249/01.mss.0000135781.42515.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva KN, Angelova PA, Gerginska FD, Terzieva DD, Shishmanova-Doseva MS, Delchev SD, Vasilev VV (2017) The effect of flutamide on the physical working capacity and activity of some of the key enzymes for the energy supply in adult rats. Asian J Androl 19(4):444–448. 10.4103/1008-682X.177842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerginska F, Delchev S, Vasilev V, Georgieva K, Boyadjiev N (2022) The selective androgen receptor modulator ostarine increases the extracellular matrix in the myocardium without altering it in the EDL muscle. Acta Morphologica Et Anthropologica 29(3–4):45–48 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon FE, Nutt CL, Cheunsuchon P, Nakayama Y, Provencher KA, Rice KA, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A (2010) Increased expression of angiogenic genes in the brains of mouse meg3-null embryos. Endocrinology 151(6):2443–2452. 10.1210/en.2009-1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould HP, Hawken JB, Duvall GT, Hammond JW (2021) Asynchronous bilateral Achilles tendon rupture with selective androgen receptor modulators: a case report. JBJS Case Connect 11(2). 10.2106/JBJS.CC.20.00635 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hackney AC (2008) Effects of endurance exercise on the reproductive system of men: the “exercise-hypogonadal male condition.” J Endocrinol Invest 31(10):932–938. 10.1007/BF03346444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittel DS, Axelson M, Sarna N, Shearer J, Huffman KM, Kraus WE (2010) Myostatin decreases with aerobic exercise and associates with insulin resistance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(11):2023–2029. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0b9a8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann DB, Saul D, Schilling AF, Sehmisch S, Komrakova M (2022) Combination of selective androgen and estrogen receptor modulators in orchiectomized rats. J Endocrinol Invest 45(8):1555–1568. 10.1007/s40618-022-01794-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horák V (1983) A successive histochemical staining for succinate dehydrogenase and “reversed”-ATPase in a single section for the skeletal muscle fibre typing. Histochemistry 78(4):545–553. 10.1007/BF00496207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulmi JJ, Ahtiainen JP, Kaasalainen T, Pöllänen E, Häkkinen K, Alen M, Selänne H, Kovanen V, Mero AA (2007) Postexercise myostatin and activin IIb mRNA levels: effects of strength training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39(2):289–297. 10.1249/01.mss.0000241650.15006.6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Hwang DJ, Narayanan R, Miller DD, Dalton JT (2010) Effects of a novel selective androgen receptor modulator on dexamethasone-induced and hypogonadism-induced muscle atrophy. Endocrinology 151(8):3706–3719. 10.1210/en.2010-0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazeminasab F, Marandi M, Ghaedi K et al (2013) Endurance training enhances LXRα gene expression in Wistar male rats. Eur J Appl Physiol 113:2285–2290. 10.1007/s00421-013-2658-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintz P, Gheddar L, Paradis C, Chinellato M, Ameline A, Raul JS, Oliva-Labadie M (2021) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonist (PPAR-δ) and selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) abuse: clinical, analytical and biological data in a case involving a poisonous combination of GW1516 (cardarine) and MK2866 (ostarine). Toxics 9(10):251. 10.3390/toxics9100251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MI, Noakes TD (1989) Dissociation of changes in VO2 max, muscle QO2, and performance with training in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 66(4):1620–5. 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MI (1990) The effects of training overload on treadmill trained rats. Dissertation. University of Cape Town Medical School

- Leciejewska N, Pruszyńska-Oszmałek E, Nogowski L, Sassek M, Strowski MZ, Kołodziejski PA (2023) Sex-specific cytotoxicity of ostarine in cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 577:112037. 10.1016/j.mce.2023.112037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leciejewska N, Jędrejko K, Gómez-Renaud VM et al (2024) Selective androgen receptor modulator use and related adverse events including drug-induced liver injury: analysis of suspected cases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 80:185–202. 10.1007/s00228-023-03592-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25(4):402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL (2010) Exercise physiology: nutrition, energy, and human performance, 7th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- Mohideen H, Hussain H, Dahiya DS, Wehbe H (2023) Selective androgen receptor modulators: an emerging liver toxin. J Clin Transl Hepatol 11(1):188–196. 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair AB, Jacob S (2016) A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm 7(2):27–31. 10.4103/0976-0105.177703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan R, Mohler ML, Bohl CE, Miller DD, Dalton JT (2008) Selective androgen receptor modulators in preclinical and clinical development. Nucl Recept Signal 6:e010. 10.1621/nrs.06010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton L, Norton K, Lewis N (2012) Exercise training improves fasting glucose control. Open Access J Sports Med 3:209–214. 10.2147/OAJSM.S37065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybo L, Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Mohr M, Hornstrup T, Simonsen L, Bülow J, Randers MB, Nielsen JJ, Aagaard P, Krustrup P (2010) High-intensity training versus traditional exercise interventions for promoting health. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(10):1951–1958. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181d99203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan G, Owen A, Bird SR, Kearney EM, Nevill AM, Jones DW, Woolf-May K (2005) Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary heart disease risk factors following 24 wk of moderate- or high-intensity exercise of equal energy cost. J Appl Physiol 98(5):1619–1625. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01310.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschoal M, de Cássia MR, Perez S, Selistre-de-Araujo HS (2009) Nandrolone inhibits VEGF mRNA in rat muscle. Int J Sports Med 30(11):775–778. 10.1055/s-0029-1234058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencina KM, Burnett AL, Storer TW, Guo W, Li Z, Kibel AS, Huang G, Blouin M, Berry DL, Basaria S, Bhasin S (2021) A selective androgen receptor modulator (OPK-88004) in prostate cancer survivors: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106(8):2171–2186. 10.1210/clinem/dgab361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta S, Carrascosa JM, Gallardo N, Ros M, Arribas C (2002) Ageing increases SOCS-3 expression in rat hypothalamus: effects of food restriction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296(2):425–428. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00906-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter JB, Barnard RJ, Edgerton VR, Gillespie CA, Stempel KE (1972) Metabolic profiles of three fiber types of skeletal muscle in guinea pigs and rabbits. Biochemistry 11(14):2627–2633. 10.1021/bi00764a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy S, Sullivan R, Zafar N, Narayanan R (2016) Tissue-selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Neuromuscul Disord 26:S130. 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.06.163 [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy S, Sullivan RD, You D, Zafar N, He Yang C, Thiyagarajan T, Johnson DL, Barrett ML, Koehler NJ, Star M, Stephenson EJ, Bridges D, Cormier SA, Pfeffer LM, Narayanan R (2017) Androgen receptor agonists increase lean mass, improve cardiopulmonary functions and extend survival in preclinical models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 26(13):2526–2540. 10.1093/hmg/ddx150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roch PJ, Henkies D, Carstens JC, Krischek C, Lehmann W, Komrakova M, Sehmisch S (2020) Ostarine and ligandrol improve muscle tissue in an ovariectomized rat model. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:556581. 10.3389/fendo.2020.556581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roch PJ, Wolgast V, Gebhardt MM, Böker KO, Hoffmann DB, Saul D, Schilling AF, Sehmisch S, Komrakova M (2022) Combination of selective androgen and estrogen receptor modulators in orchiectomized rats. J Endocrinol Invest 45(8):1555–1568. 10.1007/s40618-022-01794-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran M, Shearer TW, Stimpson SA, Turner SM, King C, Wong PY, Shen Y, Turnbull PS, Kramer F, Clifton L, Russell A, Hellerstein MK, Evans WJ (2016) Proteome-wide muscle protein fractional synthesis rates predict muscle mass gain in response to a selective androgen receptor modulator in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310(6):E405–E417. 10.1152/ajpendo.00257.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchekalarova J, Hrischev P, Ivanova P, Boyadjiev N, Georgieva K (2022) Metabolic footprint in young, middle-aged and elderly rats with melatonin deficit. Physiol Behav 250:113786. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevis M, Schänzer W (2018) Detection of SARMs in doping control analysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 464:34–45. 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner RM, Eichner A, Bhasin S, Deuster PA, Eichner D (2017) Chemical composition and labeling of substances marketed as selective androgen receptor modulators and sold via the internet. JAMA 318(20):2004–2010. 10.1001/jama.2017.17069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev V, Boaydjiev N, Deneva T, Arabadzhiyska D, Komrakova M, Georgieva K (2024a) Effects of ostarine and endurance training on some functional, hematological, and biochemical parameters in male rats. Asian J Sports Med 15(1):e138116. 10.5812/asjsm-138116 [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev V, Boyadjiev N, Hrischev P, Gerginska F, Delchev S, Arabadzhiyska D, Komrakova M, Boeker KO, Schilling AF, Georgieva K (2024b) Ostarine blunts the effect of endurance training on submaximal endurance in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 397(9):6523–6532. 10.1007/s00210-024-03030-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali JD, Pak KC, Beverley HR, DeLuca JP, Downs JW, Kress AT, Sadowski BW, Selig DJ (2023) Systematic review of safety of selective androgen receptor modulators in healthy adults: implications for recreational users. J Xenobiot 13(2):218–236. 10.3390/jox13020017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters RE, Rotevatn S, Li P, Annex BH, Yan Z (2004) Voluntary running induces fiber type-specific angiogenesis in mouse skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287(5):C1342–C1348. 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Loenneke JP, Jo E, Wilson GJ, Zourdos MC, Kim JS (2012) The effects of endurance, strength, and power training on muscle fiber type shifting. J Strength Cond Res 26(6):1724–1729. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318234eb6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Anti-Doping Agency (2020) Anti-doping testing figures 2020. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/2020_anti-doping_testing_figures_en.pdf

- Wu-Peng XS, Chua SC Jr, Okada N, Liu SM, Nicolson M, Leibel RL (1997) Phenotype of the obese Koletsky (f) rat due to Tyr763Stop mutation in the extracellular domain of the leptin receptor (Lepr): evidence for deficient plasma-to-CSF transport of leptin in both the Zucker and Koletsky obese rat. Diabetes 46(3):513–518. 10.2337/diab.46.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz M, Demircan T (2024) Exploring the potentials of S4, a selective androgen receptor modulator, in glioblastoma multiforme therapy. Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3869746/v1 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.