Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are standard treatment for advanced melanoma. Pembrolizumab (programmed cell death-1 inhibitor) monotherapy is recommended as first-line treatment. However, real-world evidence on its efficacy and safety in Australia, a region with the highest melanoma incidence, remains limited.

Objective

This study aimed to assess real-world outcomes of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma in Australia.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using national Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and National Death Index data via the Australian Bureau of Statistics DataLab. Patients who initiated pembrolizumab monotherapy for stage III/IV unresectable melanoma (1 January, 2017–30 June, 2022) were included. Kaplan–Meier analyses and multivariate Cox regressions were performed to assess overall survival and time to treatment discontinuation. Immune-related adverse events were inferred from corticosteroid and levothyroxine prescriptions. Subgroup analyses were performed by age (18–64, 65–84, ≥ 85 years) and sex.

Results

Among 4127 patients, the median overall survival was 816 days. Mortality was higher in patients aged 65–84 years (adjusted hazards ratio 1.39, 95% confidence interval 1.24–1.56) and ≥85 years (adjusted hazards ratio 1.93, 95% confidence interval 1.69–2.21) versus 18–64 years. Median time to treatment discontinuation was 377 days, with a higher discontinuation rate in female individuals (adjusted hazards ratio 1.19, 95% confidence interval 1.09–1.29). Incident corticosteroid and levothyroxine prescriptions were observed in 19.3 and 7.6% of patients, respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings align with clinical trials, demonstrating similar survival outcomes. Younger patients benefited more from pembrolizumab, while female individuals had shorter treatment durations. Further research is required to explore immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy, safety, and treatment disparities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11523-025-01164-2.

Key Points

| This study represents the first Australian population-based analysis that leveraged national-level healthcare claims and mortality data to examine real-world outcomes of pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma. |

| Real-world Australian data indicate pembrolizumab monotherapy for advanced melanoma achieves survival outcomes consistent with clinical trials, though effectiveness may decrease with older age. |

| Potential sex-based differences in treatment discontinuation warrants further exploration in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. |

Background

Melanoma accounts for 1.7% of all global cancer diagnoses [1], with Australia and New Zealand having some of the highest incidence rates (age-standardized rate of 35.8 per 100,000 persons) [2]. Prognosis for cutaneous melanoma heavily depends on disease stage: localized melanoma has a 5-year relative survival rate of over 99%, while metastatic melanoma has a survival rate of only 35% [3].

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become the cornerstone of treatment for unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), and lymphocyte activation gene 3 have transformed the treatment landscape for advanced melanoma and other cancers [4]. These agents have demonstrated substantial survival benefits in clinical trials, establishing their role as the standard of care in unresectable advanced melanoma [5]. Both international and Australian guidelines recommend ICIs, including pembrolizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) monotherapy, as first-line therapy for advanced melanoma [6–10]. Pembrolizumab was first approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration and subsidized by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia in 2015 for advanced melanoma [11, 12], with subsequent approvals for other cancer types, including non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer. By 2020, pembrolizumab had become the most widely used antineoplastic agent in Australia, with government expenditure reaching approximately AUD$560 million annually [13].

The approval of pembrolizumab by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for advanced melanoma was based on the pivotal KEYNOTE-006 trial [11, 14], which demonstrated improved survival compared with ipilimumab monotherapy, a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibitor [15]. However, clinical trials like KEYNOTE-006 often do not reflect the diversity and complexity of real-world patient populations because of strict exclusion criteria [16]. For instance, the KEYNOTE-006 trial excluded patients with brain metastases or active autoimmune diseases [15], and the median age of participants was lower than that of typical patients with advanced melanoma in clinical practice [16]. While real-world studies from the USA [17–19], Europe [20–22], and New Zealand [23] have examined the effectiveness of pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma, their findings may not be directly applicable to the Australian context because of differences in demographics, healthcare systems, and treatment practices (e.g., access to healthcare and supportive treatments). Additionally, these studies had small sample sizes (range 138–664 patients) [17–23], further limiting their generalizability. This creates a critical gap in understanding how pembrolizumab performs in broader unselected patient populations, particularly in countries with a high melanoma burden like Australia. Therefore, a national population-based study is needed to assess real-world outcomes of pembrolizumab and determine if clinical outcomes vary across patient groups within Australian healthcare settings.

Given the high prevalence of advanced melanoma in Australia and the greater use of pembrolizumab compared with other ICIs (e.g., nivolumab, nivolumab/ipilimumab) [13], we conducted a population-based study using national-level healthcare claims data. The primary objectives were to assess real-world survival, treatment persistence, and safety outcomes for patients initiating pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma, and to explore potential variations by age and sex.

Methods

Study Setting, Study Design, and Data Source

In Australia, all citizens and permanent residents are eligible for subsidized prescription medications through the PBS, part of Medicare, the country’s publicly funded universal healthcare system [24]. Data are collected each time a PBS medicine is dispensed at approved pharmacies [25]. This retrospective cohort study used linked national data from the PBS and the National Death Index, accessed through the Person Level Integrated Data Asset at the Australian Bureau of Statistics DataLab [26]. The study was classified as negligible risk and exempted from ethical approval by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement guidelines [27].

Definition of the Study Cohort

Individuals initiating pembrolizumab for stage III or IV unresectable (advanced) melanoma between 1 January, 2017 and 30 June, 2022 were identified using PBS data. This dataset included demographic information (patient age, sex, and postcode) and PBS item codes [25]. These codes specify the medication, including its generic name, strength, dosage form, and route of administration [25]. For pembrolizumab, the PBS item codes are also indication specific, detailing the approved cancer type and dosing schedule (e.g., 3 weekly or 6 weekly). For this study, only PBS item codes specific to unresectable stage III or IV melanoma were included (Table S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). These codes require prior authority approval, with prescribers certifying patients’ clinical eligibility in accordance with PBS restrictions. Specifically, authority to prescribe pembrolizumab must be obtained based on defined clinical criteria. Although PBS claims data do not contain diagnostic codes, the use of indication-specific item codes and authority approval ensures reliable identification of individuals receiving treatment specifically for unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. New users were defined as individuals with no ICI dispensing for any indications from 1 August, 2013 (when ipilimumab was first listed on the PBS [28]) until the first recorded pembrolizumab prescription for advanced melanoma (index date). Only the first treatment episode per patient was included in the analyses.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Age at treatment initiation, sex, patient residential postcode, and treatment regimen (3- or 6-weekly dosing) were extracted from the index pembrolizumab prescription. Patients’ ages were grouped into 18–64, 65–84, and 85+ years. Socioeconomic status, based on the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage [29] and remoteness of usual residence, based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard were derived using patients’ postcodes [30]. Comorbidity burden was assessed using the Rx-Risk Comorbidity Index (Rx-Risk) score, a validated medication-based tool that identifies 46 chronic conditions (e.g., corticosteroid-responsive diseases, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease) based on Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical codes from PBS dispensing data in the 12 months preceding treatment initiation [31]. The score is weighted based on the association of specific conditions—identified through medication dispensing patterns—with mortality risk, such that higher scores reflect a greater burden of comorbidity. For this analysis, cancer-related medications were excluded from the Rx-Risk score calculation to avoid confounding with the study outcome. The score is weighted according to the association between specific conditions (inferred from medications) and the mortality risk, with higher scores indicating a greater burden of comorbidity. Notably, the weighted Rx-Risk score may be ≤ 0, as the index incorporates certain medications associated with a reduced mortality risk [31]. To assess prior targeted therapy use, we examined whether patients had received BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors in the 12 months before pembrolizumab initiation (Table S2 of the ESM), as these are first-line treatments for advanced melanoma with a BRAF V600 mutation [6–10]. To further account for potential confounding in the analyses, concurrent use of other cancer drugs was defined as at least one dispensing of an antineoplastic agent (Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical code starting with “L01”) [31] during the pembrolizumab treatment episode. As pembrolizumab is approved and PBS subsidized as monotherapy for advanced melanoma, concurrent dispensing of other cancer medicines likely reflects treatment for a separate primary malignancy or an unrelated cancer diagnosis, rather than combination therapy for melanoma.

Outcomes

The outcomes assessed were overall survival (OS), time to treatment discontinuation (TTD), and immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Overall survival was defined as the time from the index pembrolizumab prescription to death from any cause, with patients censored at the end of the observation period (30 June, 2023). Overall survival was selected as the primary outcome to align with clinical trial endpoints and to facilitate comparability across real-world studies. Cause of death was obtained from the National Death Index, which provides mortality information coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [32]. While melanoma-related deaths were reported descriptively, melanoma-specific survival was not used in time-to-event analyses, as such analyses would require competing risk models to appropriately account for non-melanoma-related deaths, particularly relevant in older populations with higher competing mortality risks. Given our focus on comparability with trial data and the challenges of implementing competing risk methods within our dataset, all-cause mortality was retained as the primary outcome.

In accordance with the previous literature, TTD was defined as the period between the index prescription and the last prescription, with an additional 21 days for 3-weekly treatment or 42 days for 6-weekly treatment [33]. Treatment discontinuation (i.e., the last prescription) was identified by a dispensing gap of more than 120 days or by the absence of any subsequent dispensing. The 120-day cutoff was based on a prior study of real-world ICI treatment discontinuation in melanoma [17]. Patients were censored at death or the end of the observation period (30 June, 2023), whichever came first.

Immune-related adverse events were identified based on incident dispensing records for levothyroxine or systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone) based on the previous literature and national clinical guidelines [33, 34]. Levothyroxine use was considered a proxy for immune-mediated thyroiditis [35], while corticosteroid use indicated treatment for other irAEs (e.g., pneumonitis, hepatitis, hypophysitis) [36]. Incident use was defined as the absence of any dispensing records for these medications in the 12 months preceding the index treatment (Table S3 of the ESM).

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to estimate the median OS and TTD, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for all patients initiating pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma. These estimates were compared across three age groups (18–64, 65–84, and 85+ years) and by sex using the log-rank test. Kaplan–Meier estimates also determined OS and treatment retention rates at 12 and 24 months. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) for overall mortality and treatment discontinuation by age group and sex, adjusting for covariates. Covariates in the models included age group, sex, year of treatment initiation, socioeconomic status (based on the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage), remoteness of usual residence, concurrent cancer medications, prior BRAF/MEK inhibitor use, and baseline comorbidities (Rx-Risk score). The incidence of irAEs was compared between groups by the chi-squared test. For female individuals receiving an incident levothyroxine prescription, the median age was calculated to assess whether these prescriptions were more likely because of irAEs or hypothyroidism from perimenopause (defined as women aged 40–55 years) [37]. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.1).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 4127 individuals initiating pembrolizumab between 1 January, 2017 and 30 June, 2022 were identified. Table 1 presents their characteristics. The median age at treatment initiation was 76.0 years (inter-quartile range [IQR] 68.0–83.0 years), with 62.2% of participants aged 65–84 years. Male individuals made up a higher proportion than female individuals (67.3 vs 32.7%). The median weighted Rx-Risk score was 4.0 (IQR 2.0–6.5). Most patients (96.0%) received the standard 3-weekly treatment regimen. A total of 513 individuals (12.4%) had received BRAF/MEK inhibitors in the 12 months prior to their index pembrolizumab prescription. Only 6.7% had used other cancer drugs concurrently with pembrolizumab, with carboplatin being the most common (2.2%). This is consistent with PBS restrictions, which stipulate that pembrolizumab is typically used as monotherapy for advanced melanoma, and suggests that the use of additional cancer therapies likely reflects treatment for non-melanoma indications. The median follow-up period was 627 days.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals starting pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma between 1 January, 2017 and 30 June, 2022

| “ICI-naïve” users (N = 4127) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 76.0 (68.0–83.0) |

| Age group, years, n (%) | |

|

18–64 65–84 85 or above |

794 (19.3) 2569 (62.2) 764 (18.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

|

Male Female |

2779 (67.3) 1348 (32.7) |

| Initiation yeara, n (%) | |

|

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 |

1070 (25.9) 1030 (25.0) 745 (18.1) 508 (12.3) 521 (12.6) 253 (6.1) |

| Regimen of index prescription, n (%) | |

| Standard interval (maximum 200 mg every 3 weeks) | 3960 (96.0) |

| Extended interval (maximum 400 mg every 6 weeks) | 167 (4.0) |

| Co-payment type of index prescription, n (%) | |

|

General Concessional Concessional (safety net) |

1332 (32.3) 2576 (62.4) 219 (5.3) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | |

|

Q1 (most advantaged) Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 (most disadvantaged) Unknown |

939 (22.8) 750 (18.2) 835 (20.2) 783 (19.0) 786 (19.0) 34 (0.8) |

| Remoteness of residence, n (%) | |

|

Major cities of Australia Inner regional Australia Outer regional Australia Remote Australia Very remote Australia Unknown |

2534 (61.4) 1107 (26.8) 401 (9.7) 38 (1.0) 13 (0.3) 34 (0.8) |

| Weighted Rx-Risk comorbidity score, median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–6.5) |

| Weighted Rx-Risk score, n (%) | |

|

≤ 0 1 2 3+ |

686 (16.6) 295 (7.1) 484 (11.7) 2662 (64.6) |

| Previous use of BRAF/MEK inhibitorsb, n (%) | 513 (12.4) |

| Concurrent use of other cancer drugsc, n (%) | 276 (6.7) |

|

Methotrexate Pemetrexed Fluorouracil Gemcitabine Paclitaxel Ibrutinib Carboplatin |

45 (1.1) 57 (1.4) 12 (0.3) 12 (0.3) 27 (0.7) 10 (0.2) 90 (2.2) |

ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, IQR inter-quartile range

aThe decline in pembrolizumab initiation between 2019 and 2021 may reflect changes in clinical practice patterns, including the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the use of alternative immunotherapy regimens, such as the nivolumab/ipilimumab combination. The lower number of initiations observed in 2022 is attributable to partial data capture only, as the study period ended on 30 June, 2022

bAt least one recorded dispensing of a BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib, encorafenib, vemurafenib) or MEK inhibitor (binimetinib, cobimetinib, selumetinib, trametinib) within the past 12 months prior to pembrolizumab initiation

cAt least one dispensing record with an Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical code beginning with “L01”, which corresponds to antineoplastic agents for malignancies during the pembrolizumab treatment episode

Overall Survival

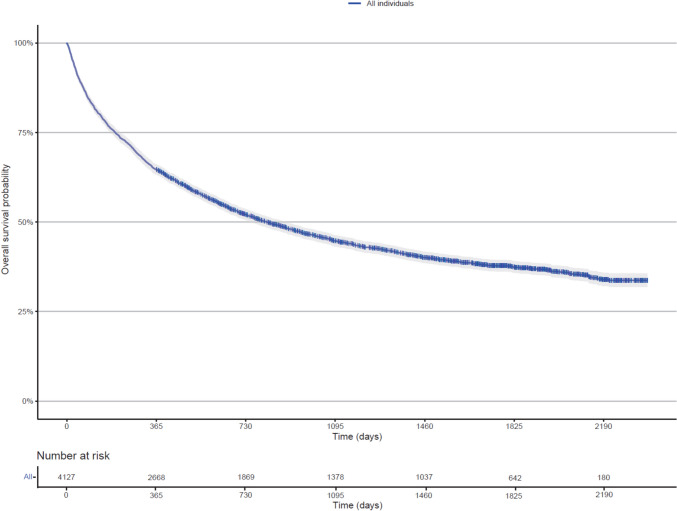

Among deaths in the cohort, 72.6% were melanoma related, with similar rates observed across age groups: 83.2% for 18–64 years, 70.7% for 65–84 years, and 70.0% for 85+ years. This high proportion of melanoma-related deaths is reassuring and supports the relevance of OS as a meaningful endpoint in this population. Below, we report results for all-cause mortality. Figures 1 and 2 present the Kaplan–Meier curves for OS in the entire cohort, by age group, and by sex. The median OS for the cohort was 816 (95% CI 755–896) days, with 1- and 2-year OS rates of 64.6% (95% CI 63.2–66.1) and 52.0% (95% CI 50.5–53.6), respectively. Median OS was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in the 18–64 years of age group (1590 days) compared to the 65–84 years of age (831 days) group and 85+ years of age (550 days) group. The aHRs for overall mortality were significantly higher in the 65–84 years of age (aHR 1.39, 95% CI 1.24–1.56) and 85+ years of age (aHR1.93, 95% CI 1.69–2.21) compared with the 18–64 years of age group. There was no significant difference in median OS between female and male individuals (p = 0.64), and the aHR for overall mortality in female individuals was 0.97 (95% CI 0.89–1.06). Sensitivity analyses further confirmed the absence of significant sex-based differences in OS within any age subgroup. A summary of OS findings is presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival in all individuals initiating pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival stratified by a age groups and b sex

Table 2.

Summary of Kaplan–Meier estimates and multivariate Cox regression analyses for OS and TTD

| OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median OS, days (95% CI) | OS rate at 1 year (95% CI) | OS rate at 2 years (95% CI) | aHRa for overall mortality (95% CI) | |

| All patients (N = 4127) | 816 (755–896) | 64.6% (63.2–66.1) | 52.0% (50.5–53.6) | n/a |

| Age subgroups, years | ||||

| 18–64 (N = 794) | 1590 (1,207–NR) | 67.8% (64.6–71.1) | 59.7% (56.4–63.2) | Reference |

| 65–84 (N = 2569) | 831 (755–925) | 65.2% (63.4–67.1) | 52.3% (50.4–54.3) | 1.39 (1.24–1.56) |

| 85 or above (N = 764) | 550 (485–649) | 59.6% (56.2–63.1) | 42.8% (39.3–46.5) | 1.93 (1.69–2.21) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (N = 2779) | 833 (760–938) | 64.6% (62.8–66.4) | 52.4% (50.5–54.3) | Reference |

| Female (N = 1348) | 784 (685–898) | 64.8% (62.3–67.4) | 51.3% (48.7–54.1) | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) |

| TTD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median TTD, days (95% CI) | Treatment retention rate at one-year (95% CI) | Treatment retention rate at two-year (95% CI) | aHRa for treatment discontinuation (95% CI) | |

| All patients (N = 4127) | 377 (363–385) | 51.1% (49.3–52.9) | 25.6% (24.0–27.4) | n/a |

| Age subgroups, years | ||||

| 18–64 (N = 794) | 377 (349–392) | 51.1% (47.2–55.2) | 26.7% (23.3–30.7) | Reference |

| 65–84 (N = 2569) | 384 (369–399) | 52.6% (50.4–54.9) | 26.4% (24.4–28.7) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) |

| 85 or above (N = 764) | 335 (292–377) | 45.6% (41.5–50.2) | 20.5% (16.8–25.2) | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (N = 2779) | 391 (378–411) | 53.7% (51.5–55.9) | 27.0% (25.0–29.2) | Reference |

| Female (N = 1348) | 336 (298–360) | 45.8% (42.8–49.1) | 22.7% (20.1–25.7) | 1.19 (1.09–1.29) |

Bold values indicate p < 0.05

aHR adjusted hazards ratio, CI confidence interval, n/a not applicable, NR not reached, OS overall survival, TTD time to treatment discontinuation

aAdjusted for age group, sex, year of pembrolizumab initiation, socioeconomic status, remoteness of usual residence, concurrent use of other cancer medications, previous use of BRAF/MEK inhibitors and baseline comorbidities (Rx-Risk score) in the multivariate Cox regression model

Time to Treatment Discontinuation

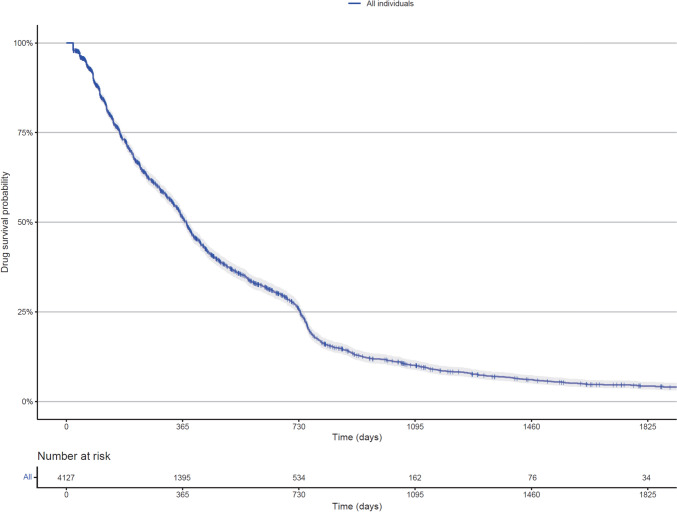

Figures 3 and 4 present the Kaplan–Meier curves for TTD in the entire cohort, by age group, and by sex. The median TTD for the cohort was 377 (95% CI 363–385) days, with 1- and 2-year treatment retention rates of 51.1% (95% CI 49.3–52.9) and 25.6% (95% CI 24.0–27.4), respectively. No significant difference in median TTD (p = 0.062) or aHRs for treatment discontinuation was observed across age groups. However, female individuals had a shorter median TTD than male individuals (336 days vs 391 days, p < 0.0001), with a higher risk of treatment discontinuation (aHR 1.19, 95% CI 1.09–1.29). Table 2 summarizes the TTD findings.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to treatment discontinuation in all individuals initiating pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to treatment discontinuation stratified by a age groups and b sex

Immune-Related Adverse Events

A total of 797 (19.3%) patients received incident prescriptions for corticosteroids, and 314 (7.6%) received incident prescriptions for levothyroxine (Table S4 of the ESM). Incident levothyroxine prescriptions were more common in individuals aged 18–64 years (10.3%) compared with the older age groups (p = 0.04). Additionally, a higher proportion of female individuals received incident levothyroxine prescriptions than male individuals (9.6 vs 6.7%, p = 0.001). Among the female individuals (n = 129), the median age was 71.0 years, with fewer than 10% aged between 40 and 55 years.

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study, we present real-world outcomes for individuals receiving pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma in Australia. This is the first study to leverage national healthcare claims data to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in this context, providing important insights into the characteristics of typical patients with advanced melanoma in Australian clinical settings. Compared with the pivotal KEYNOTE-006 trial [15], patients in our real-world cohort were significantly older, with a median age of 76 years versus 62 years in the trial. Our cohort also included patients with a broader spectrum of comorbidities, assessed via the Rx-Risk score—a validated prescription-based comorbidity index. The median Rx-Risk score was 4.0, indicating a moderately weighted comorbidity burden at baseline. In contrast to the KEYNOTE-006 trial, which excluded patients with autoimmune diseases requiring corticosteroid treatment [15], approximately 30% of patients in our study had evidence of corticosteroid-responsive diseases, as inferred from corticosteroid dispensing in the 12 months prior to the index pembrolizumab prescription. Regarding survival outcomes, the median OS in our cohort was 27.2 months (816 days), slightly lower than the 32.7 months reported in the post-hoc 5- and 10-year landmark results of the KEYNOTE-006 trial [38, 39]. The 1- and 2-year OS rates in our study were 64.6 and 52.0%, respectively, which align with the 68.4 and 55.0% rates for patients receiving pembrolizumab every 3 weeks in the KEYNOTE-006 trial [15, 40]. These results suggest that pembrolizumab achieves survival outcomes in the real-world Australian cohort that are generally consistent with those reported in pivotal trials. However, our study also highlights the broader, more representative patient population typically treated in clinical practice, including older individuals and those with additional comorbidities, providing a more comprehensive understanding of its effectiveness in routine care.

A previous study by Safi et al., using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, found that age-related disparities significantly affect OS in advanced melanoma, with younger patients experiencing better survival outcomes [41]. However, this study did not account for comorbidities or prior exposures to ICIs [41]. Our comprehensive analysis, which focused on ICI-naïve individuals and incorporated a comorbidity assessment, corroborates the finding that younger patients may derive greater survival benefits from ICI treatment. To mitigate potential biases from older patients dying of non-melanoma-related causes, we confirmed that melanoma-related death rates were consistent across age groups (83.2% for 18–64 years, 70.7% for 65–84 years, and 70.0% for 85+ years). Given the substantial costs associated with ICI treatment and public subsidies, future studies should examine the economic impact of these subsidies across age groups to ensure the cost effectiveness of pembrolizumab and similar therapies in real-world settings.

Female patients may exhibit different immunologic responses to ICIs because of factors such as sex hormones and a higher predisposition to autoimmune diseases compared with male individuals [42, 43]. A US-based study by Jang et al. examined sex differences in ICI outcomes for advanced melanoma [18], finding no significant OS difference between women and men receiving anti-PD-1 monotherapy (pembrolizumab or nivolumab). Our study similarly found no significant sex differences in OS among patients receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy. However, Jang et al. reported that female individuals receiving nivolumab/ipilimumab combination therapy had twice the mortality risk compared with male individuals, though this was limited to patients with prior ipilimumab exposure—not ICI-naïve patients [18]. Current clinical guidelines suggest both single-agent and combination ICI therapies as first-line treatments for advanced melanoma [6, 7, 9, 10]. While clinical trials (CheckMate-067 and RELATIVITY-047) show superior survival with nivolumab/ipilimumab or nivolumab/relatlimab combinations compared with anti-PD-1 monotherapy [44, 45], real-world evidence comparing these options is limited. These findings underscore the need for further studies exploring sex differences in outcomes between monotherapy and combination therapy, particularly in ICI-naïve patients, to improve the generalizability of results.

Our study found that the median TTD, a real-world proxy correlated with both OS and progression-free survival [46], was 12.6 months, consistent with similar observational studies [17, 21]. While no significant sex-based differences in OS were observed, male patients had better treatment retention and were less likely to discontinue pembrolizumab. This difference may be related to a higher incidence of irAEs among female patients. Notably, female individuals more frequently received incident prescriptions for levothyroxine, serving as a proxy for immune-related thyroiditis. Although thyroiditis is generally manageable, it may co-occur with other irAEs that contribute to treatment interruption or discontinuation. It is important to note that PBS medication claims are indirect indicators of irAEs, and the reasons for treatment discontinuation, such as toxicity, disease progression, or other factors, could not be definitively determined. Most available real-world safety data on ICIs in melanoma are derived from US-based studies [47–51], where differences in clinical practice and healthcare policies may limit the generalizability to the Australian context. In our cohort, up to 20% of patients received corticosteroids following pembrolizumab initiation, suggesting a substantial burden of irAEs. However, the absence of inpatient medication data likely led to an underestimation, particularly for drugs such as infliximab, which are often used in hospital settings for irAEs [52, 53]. Infliximab and other immunosuppressive agents are not routinely subsidized through the PBS for irAE treatment and are generally listed for chronic inflammatory conditions, such as Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis. Consequently, their off-label inpatient use for irAEs is not captured in PBS claims and was therefore not included in our analysis. Future studies should expand to Australian hospital and cancer databases to better assess the prevalence and severity of irAEs, including hospitalizations, and explore the association between irAE incidence and sex.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study leveraged national-level healthcare claims and mortality data from Australia’s universal healthcare system. The detailed claims data allowed precise identification of individuals who initiated pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma within the publicly funded system during the study period. With data covering 5.5 years of new users, our study duration exceeded the typical 1–3 years seen in previous studies [17–20, 22, 23]. The longitudinal structure of our data provided a nationwide sample, allowing for robust subgroup analyses [54]. Additionally, the claims data proved highly accurate in tracking medication initiation and discontinuation, minimizing potential biases in medication exposure assessment [55]. Furthermore, these data offered reliable insight into patients’ comorbidities by evaluating prescribed medications, which serve as proxies for pre-existing conditions (i.e., Rx-Risk score) [55]. The Rx-Risk has been shown to be comparable to other comorbidity indices, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index, confirming its validity in the Australian healthcare context [56].

Several limitations arise from the use of claims data. The diagnosis of advanced melanoma may not always be reliably determined using medication-dispensing data alone, particularly in the absence of linkage with other health datasets [57]. However, for most cancer drugs, including pembrolizumab, a PBS subsidy requires prior authority approval, and PBS coding is indication specific. These features enhance the accuracy of identifying patients receiving pembrolizumab specifically for advanced melanoma within the PBS dataset. Nonetheless, PBS data do not capture key clinical baseline variables that could affect diagnosis, treatment decisions, or outcomes. These include markers of disease burden (e.g., radiotherapy, palliative surgery, inpatient hospitalizations) [58], disease biomarkers (e.g., metastatic sites, tumor size, brain metastases) [59], and genetic profiles (e.g., BRAF mutation status) [60]. Such information is typically available through electronic medical records or cancer registries [54, 55]. For instance, the KEYNOTE-006 trial included individuals with a documented BRAF mutation status, with approximately 36% having a BRAF V600 mutation [15]. While PBS subsidizes pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma regardless of BRAF mutation status, approximately 12% of patients in our cohort had previously received BRAF/MEK inhibitors, suggesting known mutation-positive disease in that subset. The lack of detailed genetic and clinical data limits the generalizability of our findings, as we were unable to adjust for molecular characteristics in our regression models. Therefore, the observed age- and sex-based differences in outcomes should be interpreted with caution. Future studies incorporating linked clinical data are needed to validate these findings and to better elucidate the underlying drivers of treatment response and survival in real-world populations.

Conclusions

In this population-based cohort study conducted in Australia, a region with a high melanoma incidence, we provide the first national-level evaluation of pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma using healthcare claims data. Our findings demonstrate real-world survival outcomes that align with those observed in pivotal clinical trials, with younger patients showing greater benefit from pembrolizumab than older patients. We also identified differences in treatment retention, with female patients experiencing shorter treatment durations, potentially because of irAEs. These novel insights warrant further research to explore survival differences between ICI monotherapy and combination therapies, particularly with respect to sex- and treatment-related factors. Additionally, future studies are warranted to comprehensively evaluate the safety profiles of ICIs in real-world clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

Open access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors received no specific funding for this work. Alexander M. Menzies is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant unrelated to this work.

Conflict of interest

Alexander M. Menzies has served on advisory boards for BMS, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Pierre-Fabre, and QBiotics. Chin Hang Yiu and Christine Y. Lu have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was classified as negligible risk and was exempted from ethics approval by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

Consent to participate

Not applicable. No consent to participate was required as this study used only de-identified administrative healthcare data. No interventions were performed with human subjects/patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Research data are not shared, as data within the Australian Bureau of Statistics DataLab can only be accessed by approved project members.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

CHY, AMM, and CYL contributed to the study conception and design. CHY performed the data analyses and wrote the initial manuscript. CHY, AMM, and CYL contributed significantly to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of melanoma. Med Sci. 2021;9:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang J, Chan SC, Ko S, Lok V, Zhang L, Lin X, et al. Global incidence, mortality, risk factors and trends of melanoma: a systematic analysis of registries. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:965–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Survival rates for melanoma skin cancer. 2025. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/melanoma-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates-for-melanoma-skin-cancer-by-stage.html. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 4.Carlino MS, Larkin J, Long GV. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. Lancet. 2021;398:1002–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Liang X, Li H, Chen X. Comparative efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors for unresectable advanced melanoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;115: 109657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth R, Messersmith H, Kaur V, Kirkwood JM, Kudchadkar R, McQuade JL, et al. Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3947–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seth R, Agarwala SS, Messersmith H, Alluri KC, Ascierto PA, Atkins MB, et al. Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:4794–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma. 2021. Available from: https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/skin-cancer/melanoma. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 9.Michielin O, Van Akkooi ACJ, Ascierto PA, Dummer R, Keilholz U, Committee EG. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1884–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, Hauschild A, Arenberger P, Basset-Seguin N, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: treatment-update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022;170:256–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian public assessment report for Keytruda. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023.

- 12.Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Public summary document: March 2015 PBAC Meeting. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2015.

- 13.Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBS expenditure and prescriptions. Available from: https://m.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/expenditure-prescriptions/pbs-expenditure-and-prescriptions.html. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 14.Tuffaha HW, Scuffham PA. The Australian managed entry scheme: are we getting it right? Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donia M, Kimper-Karl ML, Høyer KL, Bastholt L, Schmidt H, Svane IM. The majority of patients with metastatic melanoma are not represented in pivotal phase III immunotherapy trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machado MADÁ, de Moura CS, Chan K, Curtis JR, Hudson M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Real-world analyses of therapy discontinuation of checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic melanoma patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang SR, Nikita N, Banks J, Keith SW, Johnson JM, Wilson M, et al. Association between sex and immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes for patients with melanoma. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2136823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowey CL, Scherrer E, Boyd M, Aguilar KM, Beeks A, Krepler C. Pembrolizumab utilization and clinical outcomes among patients with advanced melanoma in the US community oncology setting: an updated analysis. J Immunother. 2021;44:224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casarotto E, Chandwani S, Mortier L, Dereure O, Dutriaux C, Dalac S, et al. Real-world effectiveness of pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma: analysis of a French national clinicobiological database. Immunotherapy. 2021;13:905–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohr P, Scherrer E, Assaf C, Bender M, Berking C, Chandwani S, et al. Real-world therapy with pembrolizumab: outcomes and surrogate endpoints for predicting survival in advanced melanoma patients in Germany. Cancers. 2022;14:1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hribernik N, Boc M, Ocvirk J, Knez-Arbeiter J, Mesti T, Ignjatovic M, et al. Retrospective analysis of treatment-naive Slovenian patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab: real-world experience. Radiol Oncol. 2020;54:119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ab Rahman AS, Strother RM, Paddison J. New Zealand national retrospective cohort study of survival outcomes of patients with metastatic melanoma receiving immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2023;19:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angeles MR, Crosland P, Hensher M. Challenges for Medicare and universal health care in Australia since 2000. Med J Aust. 2023;218:322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellish L, Karanges EA, Litchfield MJ, Schaffer AL, Blanch B, Daniels BJ, et al. The Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data collection: a practical guide for researchers. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Microdata: Person Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA) [DataLab].

- 27.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H, Comey S, Hausler K, Cook G. A real world example of coverage with evidence development in Australia: ipilimumab for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-economic indexes for areas. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 30.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness areas. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure/remoteness-areas. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 31.Pratt NL, Kerr M, Barratt JD, Kemp-Casey A, Ellett LMK, Ramsay E, et al. The validity of the Rx-Risk comorbidity index using medicines mapped to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. BMJ Open. 2018;8: e021122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cancer Institute NSW. List of notifiable ICD–10 12th ed. topography codes. Available from: https://www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/research-and-data/cancer-data-and-statistics/information-for-patients-clinicians-and-notifiers/submit-cancer-cases-to-the-nsw-cancer-registry/list-of-notifiable-icd-10-am-12th-edition-topograp. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 33.Strohbehn GW, Holleman R, Burns J, Klamerus ML, Kelley MJ, Kerr EA, et al. Adoption of extended-interval dosing of single-agent pembrolizumab and comparative effectiveness vs standard dosing in time-to-treatment discontinuation. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1663–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancer Institute NSW. eVIQ: management of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Available from: https://www.eviq.org.au/clinical-resources/side-effect-and-toxicity-management/immunological/1993-management-of-immune-related-adverse-events. Accessed 01 Mar 2025.

- 35.Iyer PC, Cabanillas ME, Waguespack SG, Hu MI, Thosani S, Lavis VR, et al. Immune-related thyroiditis with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thyroid. 2018;28:1243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin K-T, Wang S-B, Ying X-J, Lan H-R, Lv J-Q, Zhang L-H, et al. Immune-mediated adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors and their management in cancer. Immunol Lett. 2020;221:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goyal G, Goyal LD, Singla H, Arora K, Kaur H. Subclinical hypothyroidism and associated cardiovascular risk factor in perimenopausal females. J Midlife Health. 2020;11:6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, Arance A, Grob J-J, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long GV, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Ribas A, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Schachter J, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: 10-year follow-up of the phase III KEYNOTE-006 study. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:1191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, Arance A, Grob J-J, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet. 2017;390:1853–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Safi M, Al-Azab M, Jin C, Trapani D, Baldi S, Adlat S, et al. Age-based disparities in metastatic melanoma patients treated in the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) versus non-ICI era: s population-based study. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 609728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irelli A, Sirufo MM, D’Ugo C, Ginaldi L, De Martinis M. Sex and gender influences on cancer immunotherapy response. Biomedicines. 2020;8:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gleicher N, Barad DH. Gender as risk factor for autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2007;28:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Rutkowski P, Cowey CL, Schadendorf D, Wagstaff J, et al. Final, 10-year outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tawbi HA, Hodi FS, Lipson EJ, Schadendorf D, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, et al. Three-year overall survival with nivolumab plus relatlimab in advanced melanoma from RELATIVITY-047. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(13):1546–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blumenthal GM, Gong Y, Kehl K, Mishra-Kalyani P, Goldberg KB, Khozin S, et al. Analysis of time-to-treatment discontinuation of targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy in clinical trials of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:830–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang F, Yang S, Palmer N, Fox K, Kohane IS, Liao KP, et al. Real-world data analyses unveiled the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors across cancer types. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tully KH, Cone EB, Cole AP, Sun M, Chen X, Marchese M, et al. Risk of immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients with preexisting autoimmune disease treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a population-based study using SEER-Medicare data. Am J Clin Oncol. 2021;44:413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown VT, Antol DD, Racsa PN, Ward MA, Naidoo J. Real-world incidence and management of immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors: retrospective claims-based analysis. Cancer Invest. 2021;39:789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalinich M, Murphy W, Wongvibulsin S, Pahalyants V, Yu K-H, Lu C, et al. Prediction of severe immune-related adverse events requiring hospital admission in patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors: study of a population level insurance claims database from the USA. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9: e001935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schonfeld SJ, Tucker MA, Engels EA, Dores GM, Sampson JN, Shiels MS, et al. Immune-related adverse events after immune checkpoint inhibitors for melanoma among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e223461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander JL, Ibraheim H, Sheth B, Little J, Khan MS, Richards C, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with corticosteroid refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis treated with infliximab. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9: e002742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai KA, Sheshadri A, Adrianza AM, Etchegaray M, Balachandran DD, Bashoura L, et al. Role of infliximab in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced pneumonitis. J Immunother Precis Oncol. 2020;3:172–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ho Y-F, Hu F-C, Lee P-I. The advantages and challenges of using real-world data for patient care. Clin Transl Sci. 2019;13:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franklin JM, Schneeweiss S. When and how can real world data analyses substitute for randomized controlled trials? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:924–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu CY, Barratt J, Vitry A, Roughead E. Charlson and Rx-Risk comorbidity indices were predictive of mortality in the Australian health care setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniels B, Tervonen HE, Pearson S-A. Identifying incident cancer cases in dispensing claims: a validation study using Australia’s Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) data. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2019;5:1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pavri SN, Clune J, Ariyan S, Narayan D. Malignant melanoma: beyond the basics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:330e-e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buder-Bakhaya K, Hassel JC. Biomarkers for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment: a review from the melanoma perspective and beyond. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim SY, Kim SN, Hahn HJ, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Metaanalysis of BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics in primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1036–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.