Abstract

Purpose

Although Korea's medical care uses advanced technology, there are not enough doctors working in rural areas, and fewer doctors are working in challenging fields such as surgery. Medical care in Türkiye is very cost-effective for patients, but doctors have too many patients and too much work. This study compared the healthcare systems of the 2 countries and the gaps felt by surgeons.

Methods

A comparative analysis was conducted using a comprehensive literature review and a questionnaire involving medical professionals from various working positions in both countries.

Results

Doctors in both countries felt that there was a large medical gap between regions and reported that the number of doctors was small. Turkish doctors experience excessive patient overload, contributing to high stress and feelings of overwork. They also showed lower job satisfaction than in Korea. The common reasons for the low preference for general surgery residencies include intense training, excessive workload, and high risk in both countries.

Conclusion

This study identified the key challenges in medical and surgical training in Korea and Türkiye. In Korea, shortages can be addressed by reforms in general surgery residency, the development of a balanced residency selection system, and the provision of work opportunities for non-Korean professionals. In Türkiye, improving remuneration and alleviating unsafe work environments is urgent. Both countries should incentivize rural services to ensure balanced doctor distribution. Collaborative initiatives informed by these findings can enhance medical education and healthcare delivery in both countries.

Keywords: Internship and residency, Healthcare disparities, Job satisfaction, Workload, Workplace violence

INTRODUCTION

The healthcare systems of South Korea and Türkiye showcase distinct approaches to medical education and practice, shaped by sociocultural, economic, and institutional factors. South Korea excels in innovative healthcare, while Türkiye is known for cost-effective, high-quality care and is famous for medical tourism from many Western countries [1]. Despite these differences, both countries face challenges in healthcare resource distribution and retaining professionals, particularly in general surgery.

Türkiye’s system seeks to balance regional professional distribution through a residency examination and obligatory service in rural areas between doctors’ promotion [2]. Nevertheless, workforce shortages, patient overload, and brain drain occur because of a demanding work environment, high risk, and low salaries in Türkiye [3,4]. In contrast, South Korea allows doctors to choose their specialty and workplace freely, though many doctors avoid specific departments with longer working hours and higher stress, particularly in general surgery [5]. As this situation continues, the imbalance in doctors between regions continues. Nowadays, South Korea faces challenges in maintaining certain departments and ensuring an equitable healthcare distribution [5,6].

As of late 2023, South Korea had 114,918 physicians for 51,784,059 people, resulting in approximately 450.6 patients per physician and 2.22 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants [7]. Türkiye, with 194,688 physicians serving 85,372,377 people, had approximately 438.5 patients per physician and 2.28 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants [8]. Both countries fall below the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) average, highlighting a critical shortage of medical professionals [9]. Despite these global challenges in the medical system, comparative studies analyzing these issues across countries are lacking. Most research has focused on individual systems, leaving gaps in understanding how cultural and systemic differences affect issues such as physician shortages, overwork, and workplace violence. This study addresses that gap by comparing the experiences of healthcare professionals in South Korea and Türkiye, offering insights for more effective global healthcare reforms.

METHODS

Study design

This mixed-methods study examined the current and future challenges in the medical systems of South Korea and Türkiye. The rationale for selecting South Korea and Türkiye was based on both academic and practical considerations. The first author, a Turkish medical doctor currently pursuing a master’s degree in South Korea, had direct access to medical professionals in both countries, enabling unique cross-national insights. A questionnaire was developed after reviewing the existing literature, news articles, and insights from doctors’ associations. A tailored questionnaire targeted medical professionals at various experience levels and from various departments, addressing key concerns. Table 1 presents a list of questions.

Table 1. Questions in the questionnaire and accepted answer types.

a)For the resident and specialist doctors only. b)For the general practitioners, resident and specialist doctors only.

The content of this questionnaire was reviewed by faculty members at the respective authors’ affiliated medical schools. Ethical considerations included obtaining informed consent from all participants through an introductory survey text explaining the purpose of the study. The participants were assured that the data would be used solely for research, collected anonymously, and handled with strict confidentiality.

Data collection was conducted online through Google Forms [10] for over 4 weeks, with the survey available in Turkish and Korean languages to ensure accessibility. Measures to ensure data quality included validation checks and monitoring for duplicates or incomplete responses.

The Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital approved the ethics of this study (No. 2024-09-002).

Participants

This study included medical professionals from various levels and healthcare institutions in South Korea and Türkiye. Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling method to facilitate the recruitment process across a relatively homogenous group—medical doctors—who share similar professional backgrounds and training requirements. While convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling method that may limit representativeness, it was deemed appropriate in this study as it allows easier access to participants in a small population where members (i.e., practicing doctors) exhibit substantial homogeneity. Recruitment was conducted through professional networks, online platforms, and alumni networks, with support from the education and training center of Inha University College of Medicine. The majority of participants were graduates of Yuksek Ihtisas College of Medicine in Türkiye and Inha University College of Medicine in Korea. Yuksek Ihtisas College of Medicine was chosen due to the first author’s affiliation as an alumnus, facilitating access to its alumni network.

The sample consisted of intern doctors, general practitioners, resident doctors, and specialist doctors. Inclusion criteria required participants to be actively practicing in healthcare and familiar with the medical education system of their country. No specific exclusion criteria were applied.

Measurement of variables

Various key aspects of the healthcare systems in South Korea and Türkiye were evaluated using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10. The participants rated several factors related to their professional experiences, workload, and perceptions of their work environment.

Residency training satisfaction was assessed by asking the participants to rate their overall satisfaction with the quality of their training, where 1 represented dissatisfaction, and 10 signified complete satisfaction. The perceived adequacy of the number of doctors was measured on a scale where 1 indicated insufficient numbers, and 10 represented an excessive number of doctors. The balance in the distribution of doctors across regions was evaluated using a scale from 1 (unbalanced) to 10 (well-balanced).

Workload and stress-related measures were also assessed. The frequency of feeling overworked was rated on a scale from 1 (hardly ever) to 10 (always), while the daily stress levels were similarly measured, with 1 representing the minimum stress and 10 representing the maximum stress. This study assessed whether the participants felt they had sufficient time for patient examinations, with 1 indicating insufficient time and 10 representing adequate time.

The perceptions of safety, communication, and societal respect were further examined. The perceived safety of working as a doctor was rated from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest). The participants were also asked to evaluate the ease of communication with colleagues, where 1 indicated difficult communication and 10 signified ease of communication. The perceived societal respect for doctors was rated on a scale from 1 (no respect) to 10 (highly respected).

Lastly, professional satisfaction and the likelihood of recommending a career in medicine were assessed. Professional satisfaction was measured using a scale where 1 represented dissatisfaction, and 10 indicated high satisfaction. The participants were also asked to rate their likelihood of recommending medical school to others, with 1 indicating no recommendation and 10 representing a strong recommendation.

Statistical analysis and ethical considerations

Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.0 (2023-04-21 release; The R Foundation). Any missing data was omitted to maintain dataset integrity. The continuous variables were summarized as the means ± standard deviations. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Welch 2-sample t-test, one-way analysis of variance, Fisher exact test, Pearson chi-square test, Z test, and permutation test were used according to the data type and sample size. The significance level was set to α = 0.05.

RESULTS

General overview

The medical education and training pathways in South Korea and Türkiye differ notably, reflecting the approach of each country to healthcare and professional development, as shown in Fig. 1. In South Korea, the six-year program includes premedicine, basic sciences, clinical sciences, a licensure exam, and a 1-year internship. Doctors can freely choose their residency specialization, with options for further fellowship training.

Fig. 1. Medical education system and pathways of Türkiye and Korea. a)Two years of obligatory service refers to mandatory work in government-assigned healthcare facilities.

In Türkiye, the 6-year program consists of basic sciences, clinical sciences, and an internship before graduation. Graduates must complete 2 years of mandatory service as general practitioners in government-designated areas to address regional healthcare imbalances. Afterward, they take a residency examination and select their specialty based on the exam results and quotas, with additional mandatory service required after residency and fellowship training, totaling 3 periods of service.

Thirty-one participants from South Korea and 43 from Türkiye responded to the survey. The South Korean participants consisted of 6 intern doctors (19.4%), 17 resident doctors (54.8%), and 8 specialist doctors (25.8%), with no general practitioners. In contrast, the Turkish participants included 16 intern doctors (37.2%), 6 general practitioners (13.9%), 19 resident doctors (44.2%), and 2 specialist doctors (4.7%). Tables 2, 3, 4 provide a detailed summary of the principal findings of this study.

Table 2. Workforce and training conditions.

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

NA, not available.

The minimum and maximum labels of each scale are as follows: a)1, dissatisfaction to 10, signified satisfaction; b)1, insufficient to 10, excessive; and c)1, unbalanced to 10, well-balanced.

*P < 0.05, statistically significant.

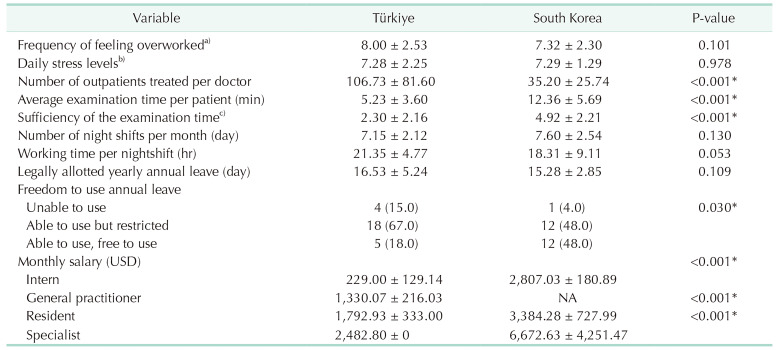

Table 3. Workload, patient interaction, and compensation.

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

USD, US dollars; NA, not available.

The minimum and maximum labels of each scale are as follows: a)1, hardly ever to 10, always; b)1, minimum to 10, maximum; and c)1, insufficient to 10, sufficient.

*P < 0.05, statistically significant.

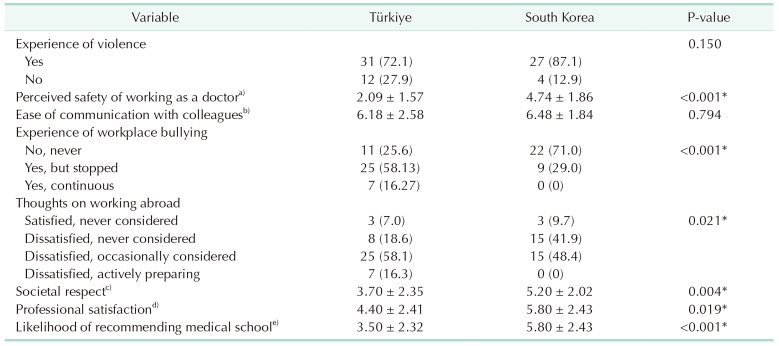

Table 4. Work environment and career outlook.

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The minimum and maximum labels of each scale are as follows: a)1, lowest to 10, highest; b)1, difficult to 10, easy; c)1, no respect to 10, well-respected; d)1, dissatisfied to 10, satisfied; e)1, no recommendation to 10, highly recommend.

*P < 0.05, statistically significant.

In evaluating the adequacy of residency education, Turkish and Korean participants reported a mean score of 7.05 ± 2.11 and 6.04 ± 2.41, respectively (P = 0.137).

Significant salary differences were observed between the 2 countries. Turkish intern doctors earned a mean salary of 229.00 ± 129.14 US dollars (USD) per month, whereas Korean interns earned 2,807.03 ± 180.89 USD (P < 0.001) per month. General practitioners and residents in Türkiye earned 1,330.07 ± 216.03 and 1,792.93 ± 333.00 USD per month, respectively, while Korean residents earned 3,384.28 ± 727.99 USD (P < 0.001). Turkish and Korean specialists earned 2,482.80 USD and 6,672.63 ± 4,251.47 USD per month, respectively (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Workforce distribution

Resident and specialist participants assessed the adequacy of resident doctor numbers. Among the Korean participants, 15 (60.0%) viewed the numbers as inadequate, while 10 (40.0%) found them sufficient, with none considering them more than needed (Fig. 2A). In contrast, 11 of the Turkish participants (52.4%) found the numbers to be inadequate; 8 (38.1%) deemed them sufficient, and 2 (9.5%) considered them more than needed (P = 0.423) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Resident doctor numbers, overall doctor sufficiency, and healthcare distribution. (A, B) Frequency of answers on the sufficiency of resident doctor numbers of Korean and Turkish respondents. (C) Comparison of the answers on the sufficiency of the total number of doctors on a 1–10 scale, with 1 indicating that the number of doctors is insufficient to meet the country’s needs and 10 indicating the number of doctors is excessive and surpassing the country’s needs. (D) Comparison of the distribution of the answers on the balance of the doctor and healthcare distribution, with 1 indicating an imbalanced distribution with a high concentration in rural areas and 10 indicating a good balance with even distribution across the country.

Regarding the sufficiency of the total number of working doctors, the Turkish participants reported a mean score of 3.58 ± 2.00, while the Korean participants gave a significantly higher mean score of 6.06 ± 2.60 on the scale (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). The participants also evaluated the regional distribution of doctors and healthcare. The Turkish participants reported a mean score of 3.00 ± 1.89, while Korean participants reported a slightly higher mean score of 4.00 ± 2.40 (P = 0.058) (Fig. 2D).

Work hours and intensity

Turkish medical professionals reported an average of 60.50 ± 18.73 working hours per week, while Korean professionals worked significantly longer at 78.55 ± 23.48 hours per week (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Specifically, intern doctors in Türkiye worked 47.9 ± 14.00 hours per week. By contrast, Korean intern doctors averaged 89.70 ± 12.27 hours per week (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Among residents, Turkish participants worked 73.21 ± 17.20 hours per week, while Korean residents worked 80.64 ± 23.34 hours per week (P = 0.339). Specialists in Türkiye worked 53.00 ± 4.24 hours per week, compared to 65.75 ± 26.58 hours in Korea (P = 0.239).

When asked about the frequency of feeling overworked, the Turkish respondents reported an average score of 8.00 ± 2.53, while the Korean participants scored 7.32 ± 2.30 (P = 0.101) (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The daily stress levels were similar, with Turkish doctors scoring 7.28 ± 2.25 and Korean doctors scoring 7.29 ± 1.29 (P = 0.978) (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

Outpatient numbers per doctor per day showed significant differences. Turkish doctors reported 106.73 ± 81.60 outpatient visits per day, while Korean doctors averaged 35.20 ± 25.74 visits per day (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). Among the participants, 8 of Turkish doctors (30.7%) reported seeing 100 or more patients per day, compared to only 1 of Korean doctors (6.6%).

Fig. 3. Average outpatient numbers and examination time. (A) Comparison of the answers on the average number of outpatients per doctor per day. (B) Comparison of the patient examination time (minutes) in the outpatient clinic per patient.

The patient examination time also differed, with Turkish doctors averaging 5.23 ± 3.60 minutes per patient, while Korean doctors averaged 12.36 ± 5.69 minutes per patient (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). Turkish doctors rated the sufficiency of this time to be lower, with a mean score of 2.30 ± 2.16, compared to 4.92 ± 2.21 from Korean doctors (P < 0.001).

Night shifts per month were similar in both countries, with Turkish and Korean doctors averaging 7.15 ± 2.12 and 7.60 ± 2.54 times a month, respectively (P = 0.130). On the other hand, the working time per night shift was slightly longer in Türkiye at 21.35 ± 4.77 hours, compared to 18.31 ± 9.11 hours in Korea (P = 0.053).

Annual leave showed minor differences, with Turkish doctors averaging 16.53 ± 5.24 days and Korean doctors 15.28 ± 2.85 days (P = 0.109) (Supplementary Fig. 4A). On the other hand, significant differences emerged in the ability to use annual leave freely: 4 of Turkish doctors (15.0%) could not use any leave; 18 (67.0%) faced restrictions, and 5 (18.0%) could use it freely. In contrast, 1 of Korean doctors (4.0%) could not use any leave; 12 (48.0%) faced some restrictions, and 12 (48.0%) could use it without limitations (P = 0.030) (Supplementary Fig. 4B).

Work environment

A significant proportion of doctors reported experiencing verbal, physical, or mental violence from patients or their relatives. In Türkiye, 31 of doctors (72.1%) encountered such incidents, while 12 (27.9%) did not. In Korea, 27 (87.1%) reported experiencing violence, with 4 (12.9%) reporting no such experiences (P = 0.150). Doctors assessed their perceived safety, with Turkish doctors reporting a mean safety score of 2.09 ± 1.57, while Korean doctors reported a higher mean score of 4.74 ± 1.86 (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The participants rated communication and team harmony, with Turkish doctors reporting a mean score of 6.18 ± 2.58, while Korean doctors gave a similar score of 6.48 ± 1.84 (P = 0.794). Regarding workplace bullying, 11 of Turkish doctors (25.6%) reported never experiencing it; 25 (58.1%) experienced it, but it had ceased, and 7 (16.3%) reported continuous bullying. In contrast, 22 of Korean doctors (71.0%) had never experienced workplace bullying, while 9 (29.0%) reported experiencing it in the past but not currently (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Doctors also evaluated their societal respect, with Turkish doctors reporting a mean score of 3.7 ± 2.35, while Korean doctors reported a higher mean score of 5.2 ± 2.02 (P < 0.004) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Personal opinions on work

Doctors expressed varying levels of satisfaction with their work environments and thoughts about working abroad. In Türkiye, 3 (7.0%) were satisfied with their current environment and never considered working abroad; 8 (18.6%) were dissatisfied but did not consider it; 25 (58.1%) occasionally thought about working abroad because of work-related issues, and 7 (16.3%) were actively preparing to work abroad. In Korea, 3 (9.7%) were satisfied and did not consider working abroad, 13 (41.9%) were dissatisfied but did not consider it, and 15 (48.4%) occasionally thought about it, with none actively preparing to do so (P = 0.021).

The doctors rated their professional satisfaction, with Turkish doctors reporting a mean score of 4.40 ± 2.41, while Korean doctors reported a higher mean score of 5.80 ± 2.43 (P = 0.019) (Supplementary Fig. 8A). When asked about their likelihood of recommending studying medicine and becoming a doctor to others, Turkish and Korean doctors gave a mean score of 3.50 ± 2.32 and 5.80 ± 2.43, respectively (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 8B).

In Türkiye, the most frequently reported healthcare issues included violence against doctors (n = 43, 100%), extreme workload and patient density (n = 41, 95.3%), and manipulation of free healthcare services, such as unnecessary emergency room visits (n = 37, 86.0%). Other concerns included mobbing, low salaries, and lack of societal respect. In Korea, the key issues were shortages of staff in specific fields (n = 21, 67.7%), excessive workload (n = 20, 64.5%), and regional healthcare disparities (n = 13, 41.9%), along with mobbing and problems with the medical insurance system.

Turkish and Korean doctors cited the intensity of training, excessive workload, high risks, and limited personal time as reasons for the low preference for general surgery residency. In addition, Korean doctors noted insufficient staff and a lack of government support, while Turkish doctors highlighted the higher risk of violence and mobbing by senior colleagues.

In Türkiye, doctors recommended improving working conditions by adjusting their hours, increasing salaries, and ensuring a violence-free workplace. They also called for a better referral system and stronger security measures with strict penalties for violence. In Korea, the participants emphasized better conditions in high-risk departments, adjusting hours, fees, and insurance costs, recruiting more staff, and expanding public hospitals. They also suggested allowing foreign doctor training and enhancing rural healthcare facilities.

DISCUSSION

This study observed a significant number of participants from resident doctors in South Korea and Türkiye, with variations in the representation of general practitioners, intern doctors, and specialist doctors across the 2 countries. Although the adequacy of residency education was highly rated, more than half of the participants felt the number of resident doctors was insufficient. Turkish doctors were moderately dissatisfied with the number of working doctors, while Korean doctors were more satisfied, possibly due to specific departmental shortages. Both countries reported that doctors were mainly concentrated in urban areas, leading to inadequate healthcare access in rural regions. Turkish doctors felt more overworked than Korean doctors, partly because of the higher outpatient visits, shorter examination times, and stricter annual leave.

While Turkish and Korean doctors reported experiencing violence in their workplaces, Turkish doctors expressed significantly lower feelings of safety. This could be attributed to the higher prevalence of physical violence in Türkiye. A study analyzing incidents of violence against healthcare professionals in Türkiye reported that doctors frequently face physical assaults from patients and their relatives, with reports of physical violence against physicians occurring in 67 out of 81 provinces across the country [11]. According to a survey by the Turkish Medical Association, 87% of healthcare workers in Türkiye have been subjected to violence, with physical violence being a notable concern [12]. This prevalence of physical attacks likely contributes to Turkish doctors’ heightened concerns about workplace safety. In contrast, although Korean doctors also reported exposure to violence, there is a lack of research documenting the specific types and frequency of violence in Korea, particularly physical assaults. This gap underscores the need for more research to understand the problem in Korea. Addressing these disparities is critical for designing interventions aimed at preventing violence in Turkish healthcare settings and further exploring workplace violence in Korea.

Communication and team harmony were reported to be moderate in both countries, though Turkish doctors experienced more workplace bullying, while Korean doctors felt more respected within their work environments. Furthermore, a higher percentage of Turkish doctors are considering or actively preparing to work abroad, contrasting with their Korean counterparts. Korean doctors also reported higher professional satisfaction and were more likely to recommend studying medicine to others. Recent reports indicate that an increasing number of Korean doctors are exploring opportunities abroad due to the ongoing disputes between medical associations and the government—such as a 2023 article discussing the rising number of doctors seeking overseas positions amid ongoing healthcare reforms [13], and a survey noting the influence of such conflicts on doctors’ career decisions [14]—the survey for this study was conducted before these developments becoming prominent. This timing may help explain why Korean doctors in this study showed less inclination to work abroad, as well as the higher satisfaction and recommendation rates compared to their Turkish counterparts.

In Türkiye, the key challenges included workplace violence, heavy patient loads, and the misuse of free healthcare services, while Korean doctors highlighted staff shortages, excessive workloads, and regional healthcare disparities.

The challenges faced by Turkish and South Korean doctors, such as overwork, stress, workplace violence, and brain drain, reflect broader global issues. Similar problems are reported worldwide, with many physicians migrating from Romania to France for better conditions or from Ireland to Australia because of the long hours and high stress [15,16]. Emergency doctors in Serbia face mobbing and violence at work, reducing job satisfaction [17], while poor conditions lead to high turnover in Iraq [18]. Workplace violence is a global issue, affecting physicians’ mental health and job satisfaction [19], as reported in studies from the United States, where managed care systems contribute to burnout because of high patient loads and time pressures [20].

The issue of insufficient doctor numbers is not unique to South Korea and Türkiye but is a critical global challenge. Many healthcare systems struggle to maintain adequate numbers of professionals, affecting care quality and burdening existing staff [21]. This shortage is worsened by doctors migrating abroad for better opportunities, further straining healthcare systems. In the United States, shortages are pronounced in rural areas, leading to higher patient-to-doctor ratios and increased workloads. The projections suggest the United States will face significant physician shortfalls by 2034, with coronavirus disease 2019 worsening these disparities [22,23].

Targeted interventions are required in both countries. In Türkiye, improving the working environment by adjusting patient flow, increasing salaries, and ensuring safety is crucial. Revising the fee structure would also help. In Korea, improving conditions in high-risk departments, adjusting hours and insurance costs, and better distribution of doctors to rural areas are essential. Increasing government support and allowing foreign doctors in less preferred areas could further strengthen the system. These actions could produce safer, more supportive environments and improve healthcare outcomes in both countries.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample was primarily drawn from 2 institutions, Inha University College of Medicine in Korea and Yuksek Ihtisas College of Medicine in Türkiye, selected for feasibility and accessibility. As a result, the findings may not fully represent the experiences of medical professionals nationwide in either country. Future studies should aim to include a broader range of participants from multiple institutions and regions to improve generalizability. Second, although the study offers valuable preliminary insights, the relatively small sample size (31 participants from Korea and 43 from Türkiye) may limit the statistical power of the comparisons. Despite our efforts to expand participation, the ongoing doctors’ strike in Korea during the study period constrained recruitment and data collection. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results, and larger-scale studies are needed to confirm and expand upon our findings.

Footnotes

This work was presented in the International Affairs Committee session at the Annual Congress of the Korean Surgical Society (ACKSS) 2023 (November 2023, Seoul, Korea).

Fund/Grant Support: This work was supported by Inha University Research Grant.

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: JWY, HH.

- Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization: HH.

- Funding acquisition: JWY.

- Investigation: SYP, HH.

- Project administration: HH, SML.

- Supervision: JWY, YMC, SKC.

- Writing – original draft: HH.

- Writing – review & editing: All authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Figs. 1–8 can be found via https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2025.109.3.151.

Average monthly salary, categorized according to the positions. USD, US dollars.

Comparison of doctors' weekly working hours: (A) overall, regardless of position; (B) by specific professional roles.

Frequency of feeling overworked and stressed. (A) Comparison of the distribution of the answers on the frequency of feeling overworked or overloaded with tasks, with 1 indicating hardly ever and 10 indicating always. (B) Comparison of the distribution of the answers on the daily stress levels, with 1 indicating the minimum and 10 indicating the maximum level of stress.

Annual leave. (A) Comparison of the frequency of answers about the average of the legally allotted number of annual leave days. (B) Comparison of the answers on the freedom to use the legally allotted annual leave.

Workplace safety.

Mobbing experience. Comparison of the frequency of the answers about whether the respondent ever had an experience of workplace bullying/mobbing.

Societal respect.

Professional satisfaction and recommendation of medical school. (A) Comparison of the distribution of the answers about the professional satisfaction levels of the respondents. 1 represents dissatisfaction, and 10 represents high levels of satisfaction on the scale. (B) Comparison of the distribution of the answers about the respondents' likelihood of recommending studying in medical school in their countries to others, with 1 signifying “would never recommend” and 10 signifying “highly recommend.”

References

- 1.Ildaş G. The tourism sector in country branding: an assessment on health tourism in Turkey. Kent Akademisi Dergisi. 2022;15:155–176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; World Health Organization (WHO) Health systems in action: Türkiye. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yılmaz S, Koyuncu Aydın S. Why is Turkey losing its doctors?: a cross-sectional study on the primary complaints of Turkish doctors. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19882. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erdoğan Kaya A, Erdoğan Aktürk B, Aslan E. Factors predicting the motivation to study abroad in Turkish medical students: a causal investigation into the problem of brain drain. J Health Sci Med. 2023;6:526–531. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song J. Why a critical shortage of doctors in South Korea has sparked a national debate [Internet] Korea Pro; 2023. Oct 26, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://koreapro.org/2023/10/why-a-critical-shortage-of-doctors-in-south-korea-has-sparked-a-national-debate. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H. Korea ranks 2nd‑lowest in number of doctors among OECD nations [Internet] The Korea Times; 2023. Jul 25, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/health/20230725/korea-ranks-2nd-lowest-in-number-of-doctors-among-oecd-nations?utm_source=chatgpt.com. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) Status of healthcare personnel by type of medical institution (doctors, pharmacists, etc.) [Internet] KOSIS; 2023. [cited 2023 Sep 10]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=354&tblId=DT_HIRA44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Sağlık Bakanlığı. Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2022 Haber Bülteni [Internet] Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health; 2022. [cited 2023 Sep 10]. Available from: https://dosyamerkez.saglik.gov.tr/Eklenti/46511/0/haber-bulteni-2022-v7pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) Health at a glance 2021: OECD Indicators [Internet] Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2021_ae3016b9-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Google LLC. Google Forms [Web tool] Google; Available from: https://www.google.com/forms. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyazadam D, Kaya F, Taşdemir İM, Alimoğlu O. Analysis of physical violence incidents against physicians in Turkey between 2008 and 2018. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;28:641–647. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2021.66745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duvar English. Turkish Medical Association survey finds 87 pct of health workers exposed to violence [Internet] Duvar English; 2023. Dec 29, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.duvarenglish.com/turkish-medicalassociation-survey-finds-87-pct-of-healthworkers-exposed-to-violence-news-63572. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HI. Doctors say “I’m going abroad”... Irresistible offers from Japan and Vietnam [Internet] Weekly Chosun; 2023. Oct 21, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://weekly.chosun.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=37741. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon SY. Interest in US medical licensing exam among Korean medical students rises from 2% to 45% [Internet] Dailymedi; 2024. Oct 23, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.dailymedi.com/news/news_view.php?wr_id=917662. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Séchet R, Vasilcu D. Physicians’ migration from Romania to France: a brain drain into Europe? Cybergeo. 2015:743 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphries N, Connell J, Negin J, Buchan J. Tracking the leavers: towards a better understanding of doctor migration from Ireland to Australia 2008-2018. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolić D, Višnjić A. Mobbing and violence at work as hidden stressors and work ability among emergency medical doctors in Serbia. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:31. doi: 10.3390/medicina56010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali Jadoo SA, Aljunid SM, Dastan I, Tawfeeq RS, Mustafa MA, Ganasegeran K, et al. Job satisfaction and turnover intention among Iraqi doctors: a descriptive cross-sectional multicentre study. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:21. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowrouzi-Kia B, Chai E, Usuba K, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Casole J. Prevalence of type II and type III workplace violence against physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10:99–110. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2019.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, McMurray JE, Pathman DE, Williams ES, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:441–450. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorkowski J, Jugowicz A. Shortage of physicians: a critical review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1324:57–62. doi: 10.1007/5584_2020_601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) New AAMC report shows continuing projected physician shortage [Internet] AAMC; 2024. Mar 21, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-report-shows-continuing-projected-physician-shortage?utm_source=chatgpt.com. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K. The hidden health crisis: America’s physician shortage is slowly worsening [Internet] Columbia Political Review; 2024. Feb 12, [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.cpreview.org/articles/2024/2/the-hidden-health-crisis-americas-physician-shortage-is-slowly-worsening. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Average monthly salary, categorized according to the positions. USD, US dollars.

Comparison of doctors' weekly working hours: (A) overall, regardless of position; (B) by specific professional roles.

Frequency of feeling overworked and stressed. (A) Comparison of the distribution of the answers on the frequency of feeling overworked or overloaded with tasks, with 1 indicating hardly ever and 10 indicating always. (B) Comparison of the distribution of the answers on the daily stress levels, with 1 indicating the minimum and 10 indicating the maximum level of stress.

Annual leave. (A) Comparison of the frequency of answers about the average of the legally allotted number of annual leave days. (B) Comparison of the answers on the freedom to use the legally allotted annual leave.

Workplace safety.

Mobbing experience. Comparison of the frequency of the answers about whether the respondent ever had an experience of workplace bullying/mobbing.

Societal respect.

Professional satisfaction and recommendation of medical school. (A) Comparison of the distribution of the answers about the professional satisfaction levels of the respondents. 1 represents dissatisfaction, and 10 represents high levels of satisfaction on the scale. (B) Comparison of the distribution of the answers about the respondents' likelihood of recommending studying in medical school in their countries to others, with 1 signifying “would never recommend” and 10 signifying “highly recommend.”