Abstract

Background

The prevalence of depression symptoms, the third most disabling disease worldwide, is as high as 11.5%-21.1% in China’s middle-aged and elderly population and increases significantly with age. It is crucial to identify high-risk groups efficiently and implement appropriate early interventions to improve the performance of depression risk prediction models.

Methods

We used data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS, 2011–2020) to track depression the onset characteristics of depression symptoms in adults aged over 45 without depressive symptoms at baseline. This tracking was conducted over 9 years, involving four follow-ups. Eight machine-learning models, with pre-sampling and three types of resampled data, were employed. Their hyperparameters were optimized through a grid search strategy and tenfold cross-validation. Model performance was evaluated, including the area under the ROC curve (AUC), precision, recall, and F1 score. Additionally, Shapley Additive Properties (SHAP) plots for interpretability.

Results

The cumulative incidence of depression symptoms at different follow-up time points was 19.043%, 22.554%, 27.416%, and 29.416%, respectively, with higher incidence rates in females, rural areas, those with low education, and the western regions. The RandomUnder-Sampler-extreme gradient boosting(XGB) model performed optimally in predicting the 9-year risk of depression symptoms (recall = 70.36%, F1 = 0.5605, AUC = 0.750). SHAP analysis showed that education level, cognitive ability, and satisfaction with life were the core factors affecting the prediction of depression symptoms.

Conclusions

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in China’s middle-aged and elderly population is high, and the influencing factors are complex. When predicting depressive symptoms, the model should be selected based on the prediction needs, and random undersampling with XGB is suitable for long-term risk prediction in large-scale populations. For high-risk groups, accurate prediction strategies can be used to reduce the risk of depressive symptoms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-24103-2.

Keywords: Depression, Middle-aged and elderly, Morbidity characteristics, Machine learning, Predictive modeling, SHAP analysis, CHARLS

Background

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), defines depression as a persistent state of depressed mood accompanied by a variety of psychological and physical symptoms that severely impair an individual’s daily functioning. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the leading cause of nonfatal health loss, and its prevalence peaks in the older age group (55–74 years), with prevalence rates of more than 7.5% for women and 5.5% for men [1]. Depression not only directly contributes to a decline in quality of life and a surge in health care resource consumption but is also closely associated with cardiovascular disease, suicide risk, and other adverse outcomes [2, 3]. Depressive symptoms constitute a cluster of indicators associated with depressive disorders that do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria but are likely to evolve into clinical depression if not promptly addressed [4]. Research indicates that the relative risk of an individual with depressive symptoms progressing to clinical depression ranges from 1.15 to 9.73, with a median of 4.43 [5]. Compared to the intricate diagnostic criteria for clinical depression, the identification of depressive symptoms can be efficiently conducted using standardized self-assessment scales (e.g., PHQ-9, CESD-10), thereby simplifying the process and facilitating implementation. Consequently, developing an accurate predictive model of depressive symptoms for the middle-aged and elderly population, with a focus on early detection, is essential for effective prevention and management of depressive symptoms.

Studies have shown that the development of depressive symptoms is influenced by the interaction of multidimensional biopsychosocial factors, and demographic characteristics (gender, age, education level), lifestyle (smoking, alcohol abuse, physical activity), health status (Number of chronic diseases, cognitive functioning, disability), and psychosocial factors (loneliness, adverse life events, and family support) are the key risk factors [4–6]. However, traditional statistical methods struggle to effectively address the nonlinear associations and interactions among multidimensional health indicators; thus, improving the performance of depressive symptoms risk prediction models is crucial for more efficiently identifying at-risk populations and implementing appropriate early interventions [7].

Machine learning (ML) has significant advantages in disease prediction through algorithms that mimic human learning mechanisms [8, 9]. Compared with traditional statistical methods, ML can more accurately capture the complex associations between inputs and outputs when addressing multivariate relationships and thus improve the predictive performance of the model [10]. Specifically, ML can filter key influencing factors from multidimensional data, such as demographic characteristics, living habits, and health indicators, through feature selection techniques [11]. Its nonlinear fitting ability is also significantly better than that of traditional models, which can effectively portray the nonlinear associations of multiple factors in the onset of depressive symptoms [12]. Machine learning (ML) has significant advantages in disease prediction through algorithms that mimic human learning mechanisms.

Currently, ML studies on depressive symptoms primarily rely on cross-sectional research designs [10, 13], and generally lack the integration and analysis of multimodal data concerning demographic traits, health conditions, and lifestyle factors. Consequently, this research examined the characteristics of depressive symptom emergence within the middle-aged and elderly demographic utilizing nationally representative cohort data derived from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Additionally, eight machine learning models, using pre-sampling and three types of resampled data, were developed to emphasize both predictive effectiveness and interpretability. The purpose of these models is to address existing gaps in long-term dynamic prediction research and the integration of multidimensional data, thereby providing a scientific foundation for early detection of depressive symptoms and targeted intervention.

Objects and methods

Objects of study

The CHARLS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey program led by the China National Development Research Institute (NDRI) for people aged 45 and over and their spouses. The survey assesses the social, economic, and health status of people in the community. Detailed information on the study population has been reported in other publications [13]. The national baseline survey (wave 1) was completed in 2011–2012 and covered 10,257 households and 17,708 participants from 28 provinces in China. Thereafter, participants’ follow-up was conducted every two to three years. This study used baseline data from 2011 and four subsequent follow-ups: the first follow-up in 2013 (wave 2), the second follow-up in 2015 (wave 3), the third follow-up in 2018 (wave 4), and the fourth follow-up in 2020 (wave 5). The Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-11015) approved the baseline and follow-up data of CHARLS. The study was conducted in compliance with China’s “Regulations on Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (Trial Version, 2007)” and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2008 version), with all respondents providing written informed consent as required by the review committee at the time of data collection.

Selection of research subjects

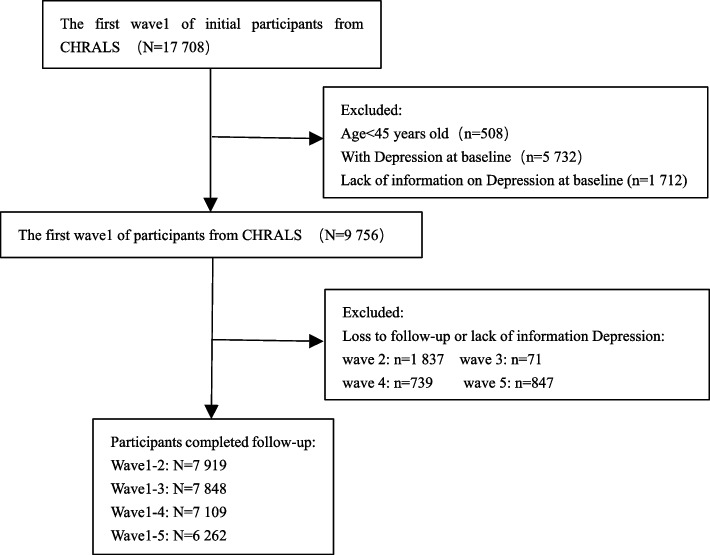

A total of 17,708 participants were enrolled in wave 1 and screened to exclude subjects who (1) were younger than 45 years of age, (2) had preexisting depressive symptoms at the time of the baseline survey (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – 10 (CESD-10) score ≥ 10 points), and (3) had missing information on CDSD-10 scores from the baseline survey. After screening, 9,756 eligible subjects were enrolled in the baseline study. At each subsequent wave of follow-up, those who were lost to follow-up or those with missing CESD-10 score information were excluded. Specifically, 7,919, 7,848, 7,109, and 6,262 study subjects were enrolled in the follow-ups for waves 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. These data were used to examine the onset of depressive symptoms at different follow-up time points. Moreover, data from 6,262 study subjects, from baseline follow-up to wave 5, were used to conduct a 9-year risk prediction analysis for depressive symptoms.

The selection of subjects for this study is displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of research subjects

Measurement of outcome variables

The outcome variable in this study was depressive symptoms, which were assessed in the middle-aged and elderly population by the CHARLS using the CESD-10. The CHARLS uses the CESD-10 scale to assess depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly individuals. The CESD-10 was streamlined by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and is based on the classic CESD-20 scale, which is designed to provide rapid screening of depressive symptoms through 10 items [14]. The scale consists of four major dimensions. The emotional dimension: entry 1 (emotional distress), entry 5 (hope for the future), and entry 8 (pleasure); the cognitive dimension: entry 2 (difficulty concentrating) and entry 3 (denial of self-worth); the physiological dimension: entry 4 (sleep disturbances), entry 6 (changes in appetite), and entry 7 (energy levels); the behavioral dimension: entry 9 (slowed movement) and entry 10 (decreased interest). Each entry was scored on a 4-point scale, with zero representing never, one representing rarely (1–2 days), two representing sometimes (3–4 days), and three representing often (5–7 days). Ten questions were scored from 0 to 30 points, and the scores were summed across all items by applying a reverse scale to entries 5 (“hopeful about the future”) and 8 (“feeling happy”), with higher scores indicating depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms, with a score of 10 serving as the threshold for depression screening (≥ 10 indicates possible depressive symptoms). The CESD-10 scale has been used to assess depressive symptoms in several countries. Several studies have demonstrated that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the CESD-10 scale exceeds 0.7, indicating high internal consistency [15, 16]. According to the CHARLS data, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the CESD-10 scale in the middle-aged and elderly population aged 45 years or older in China is 0.815, indicating good consistency among the items [17].

Candidate variables for risk prediction studies

Using relevant literature and information from the CHARLS dataset, this study identified a series of key candidate variables. These variables fall into two main categories: demographic background, health status and functioning. The demographic background includes age, gender, ethnicity, education, rural, marriage, region, and retirement status data. Health status and functioning includes health status, lifestyle and health behaviours, functional limitations and helpers, and cognition. Among these, health status and functioning included self-rated health, disease history (e.g., hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes or hyperglycemia, cancer, chronic disease, diabetes or hyperlipidemia cancer, chronic lung disease, etc.), vision, hear, tooth, disability and body pain (e.g., headache, shoulder pain, arm pain, wrist pain, finger pain, chest pain, etc.). Lifestyle and Health Behaviors included sleep time at night, social activities in the last month (including 11 social behaviors), smoking, and drinking. Functional limitations and helpers were assessed using the Activity of Daily Living Scale (ADLs) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADLs). Cognition included episodic memory, mental status, cognitive ability, and satisfaction with life. Additionally, body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and the number of Number of chronic diseases was recorded. Body mass index (BMI) is defined as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters). The inclusion of vision (distance/near vision), hearing, toothless, disability, and ADLs/IADLs functioning indicators in this study is based on the logic that sensory dysfunction (vision/hearing loss) and physical disability increase the risk of depressive symptoms through a triple mechanism. Firstly, directly contributing to physical discomfort and social isolation, secondly, exacerbating psychological burden by affecting ADLs/IADLs independence, thirdly, and chronic disease Co-morbidities create a vicious cycle [18, 19].

For disease history data, this study defined diagnostic criteria for two diseases: Hypertension was defined as meeting any of the following conditions: self-reported hypertension, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg detected by physical examination. Diabetes was defined as self-reported diagnosis by a doctor or fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5% detected by blood tests. Other disease history data were derived from participants’ self-reports.

Sixty-six variables were included in the study. Details of the definitions and measurements of the relevant variables can be found in the China Health and Aging Report [20]. For data assignments for each variable and specific definitions of ADLs, IADLs, cognitive ability, episodic memory, and mental status, see Table S1.

Preprocessing of data for risk prediction studies

To ensure that the proportion of each category of depressive symptoms outcomes in the training and test sets was similar to that in the original dataset and to improve the model generalization ability, this study first stratified the data according to the depressive symptoms outcomes and then randomly divided the data into training and test sets at a ratio of 7:3. The training set was used for model parameter calculation and training, and the test set was used to evaluate the predictive performance of the model. Before modelling, we preprocessed the data, which mainly included missing value processing, feature selection, and data resampling.

We employed the random forest imputation method for handling missing values. The random forest imputation method constructs a random forest model to predict missing values using other complete features in the dataset, which is suitable for processing data containing multiple variable types (numerical, categorical) and complex associations, especially in scenarios where there are nonlinear relationships. It can effectively improve data completeness [21]. In this study, the Python Pandas library was used to calculate the missing proportion of each feature, and the proportion of missing data for each feature is shown in Table S2. Scikit-learn’s IterativeImputer, combined with Random Forest Regressor, was used to construct the interpolation process. To avoid data leakage, the training dataset and test dataset were estimated separately.

Feature selection is a crucial component of the optimization model. The core objective is to select the subset of features with the highest predictive value from the original feature set; achieving this objective reduces the data dimensionality, improves the model performance, and saves computational resources [22]. To select key features, this study adopts the cross-validation-based least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (Lasso CV) method on the training set, achieving feature selection by regularizing the shrinkage coefficients through the L1 regularization coefficients. Specifically, this method performed unbiased screening on all 66 features after preprocessing, automatically optimized the regularization parameter α via Lasso CV (searching for the optimal solution in tenfold cross-validation), and finally retained features with non-zero coefficients (with a precision threshold of 1e-6). The choice of Lasso over recursive feature elimination (RFE) or decision tree-based feature importance analysis was based on three considerations[23]: Firstly, Lasso generates sparse solutions directly through L1 regularization, demonstrating significantly higher computational efficiency than the recursive iteration process of RFE. Secondly, as a linear model, Lasso complements subsequent ensemble models, such as random forest (RF) and extreme gradient boosting (XGB). The sparse feature subset selected by Lasso effectively reduces the overfitting risk associated with high-dimensional data. Thirdly, the absolute values of Lasso coefficients can quantify the linear correlation strength between features and depressive symptom outcomes, providing a more intuitive interpretation of feature importance.

Given the significant class imbalance in the dataset (the ratio of positive to negative samples in the training set was 1:2.35), the model is prone to bias toward the majority class (non-depressive symptoms), leading to underdiagnosis. This study attempted to address the data imbalance through various re-sampling strategies, including Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), Random Under-Sampler, and Class Weight Adjustment Strategy, to improve the model’s performance. SMOTE effectively enhances the classifier’s ability to recognize minority classes by generating synthetic samples through nearest-neighbor interpolation and balancing the ratio of positive and negative samples to 1:1 [24]. The Random Under-Sampler randomly removes the majority class samples to balance the ratio, avoiding the noise introduced by synthetic samples and preserving the authenticity of the original data [25]. The Class Weight Adjustment strategy dynamically modifies class weights during training, guiding the model to focus on identifying depressive symptoms cases by increasing the weights of the minority class loss function without changing the original sample distribution [26].

Machine learning model construction and evaluation

After the data preprocessing is completed, we input the pre-sampling (baseline) and the three post-sampling training sets into the eight classification algorithms, including RF, XGB, logistic regression (LR), light gradient boosting machine (LGB), k-nearest neighbours (KNN), decision tree (DT), naive Bayes (NB), and adaptive boosting (AdaB) algorithms. KNN is an instance-based learning method that performs classification or regression prediction by calculating the distance between the samples to be predicted and the k nearest neighbour samples in the training set [24]. LR is a statistical learning method used in classification problems that predicts the probability of an event occurring by building a logistic function that models the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable [25]. RF is an integrated learning algorithm based on decision trees that enhances the accuracy and stability of the model by constructing multiple decision trees and combining their predictions, making it suitable for addressing complex, multidimensional health data [26, 27]. XGB is a fast and efficient gradient boosting framework that prevents overfitting by optimizing the objective function and employing multiple strategies to excel in various data mining tasks [28, 29]. LGB is a highly efficient gradient-based boosting machine learning algorithm, particularly suitable for large-scale datasets and high-dimensional problems [30]. The ADT model is a tree-structured classification and regression model that classifies or predicts the values of instances by applying conditional judgments to the features, characterized by a readable model and a fast classification speed [31]. Plain Bayes is a classification algorithm based on the Bayes theorem, which assumes that the features are independent of one another and calculates the posterior probability of samples belonging to each category to perform classification [32]. AdaB is an iterative algorithm that trains multiple weak classifiers and combines them into a single strong classifier by continuously adjusting the sample weights to enhance the model’s classification performance [33]. The hyperparameters of each model were tuned by tenfold cross-validation and grid search strategies to ensure the robustness and reliability of the model performance. The optimal hyperparameter settings for each model, along with the performance metrics for cross-validation (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score), are detailed in Tables S3 and S4.

To quantify the model’s generalization ability, multidimensional categorical metrics such as the area under the curve (AUC-ROC) of the working characteristics of the subjects, precision, recall, and F1 scores in the test set are used to carry out a systematic performance evaluation. To address the need for interpretability of the model decision logic, the Shapley additive properties (SHAP) framework is adopted for feature contribution visualization. SHAP values, based on cooperative game theory, quantify the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions. For a single sample, the SHAP value of a feature indicates the amount of change in the predicted value when the feature is added to the model. The cumulative sum of the SHAP values of all features and the baseline value equals the expected value of the model. The sign of the SHAP value reflects the direction of the feature’s influence on the prediction: a positive SHAP value indicates that the feature enhances the prediction probability, while a negative SHAP value suggests that it inhibits the prediction probability; the size of the absolute value reflects the strength of the influence. The average SHAP value bar chart (average absolute SHAP value ranking) reveals the global influence weight of each variable on the prediction results. In contrast, the SHAP summary plot (Eigenvalues—Effect Values 2D Distribution) is used to demonstrate the local pattern of feature effects in the dataset [34]. The former quantifies the overall contribution of features in absolute terms, whereas the latter presents the trend of feature values about the predicted direction through the colour gradient and density distributions. The processes of data preprocessing and machine learning model construction are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The processes of data preprocessing and machine learning model construction

All the algorithms were developed and validated in Python 3.11.4. The feature selection was realized by Python’s “scikit-learn” machine learning library (version 1.1.3). During the model construction process, we utilized “XGBoost” (version 2.0.1), “lightgbm” (version 3.2.1), “scikit-learn” (version 1.1.3), and other Python libraries. Scikit-learn, as the leading open-source machine learning framework (v1.1 +) in the Python ecosystem, provides a standardized statistical learning toolchain, which broadly serves the core tasks of classification, regression, and clustering.

Statistical analysis

For normally distributed measures, we use the mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s) for representation, whereas nonnormally distributed measures are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Count data are expressed as frequencies and percentages (%). Comparisons of count data between groups were performed by the χ2 test, whereas comparisons between groups of measured data were performed using the t test or Mann‒Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of the data. Raw data cleaning was performed via Stata 17.0 software, whereas statistical analysis was performed via SPSS 17.0.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 9,756 participants, 5,155 males and 4,601 females, were included in the baseline data of this study. The mean age of the participants was 58.76 years (standard deviation 9.53 years). Of the groups included, 7,169 were Han Chinese and 529 were of other ethnicities. The urban population consisted of 4,373 people, while the rural population consisted of 5,383 people. The participants came from all regions of China, including 4,628 from the eastern region, 1,506 from the central region, 2,842 from the western region, and 780 from the northeastern region. In terms of educational attainment, 3,833 had less than an elementary school education, 2,074 had attended elementary school, 2,281 had attended secondary school, and 1,557 had attended high school and above. In terms of marital status, 8,369 participants were married, and 1,387 participants had other marital statuses.

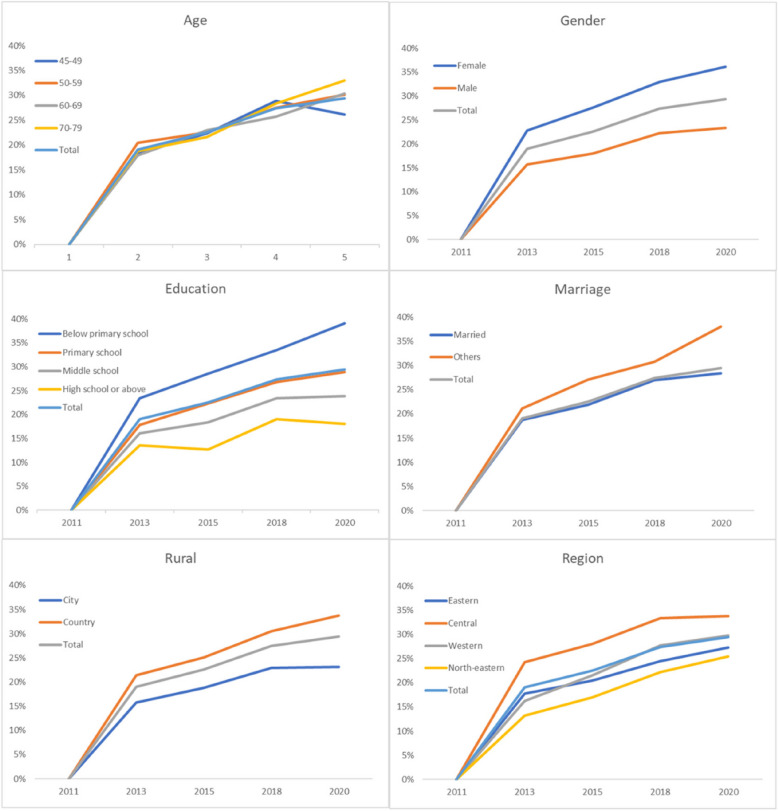

Characterization of the onset of depressive symptoms

A total of 7,919, 7,848, 7,109 and 6,262 study participants were followed up during wave 2, wave 3, wave 4 and wave 5, respectively, and the cumulative incidence (CI) of depressive symptoms was 19.043%, 22.554%, 27.416% and 29.416% at 2, 4, 7 and 9 years, respectively. Details of the annual incidence of depressive symptoms according to gender, age, ethnicity, residence, region, education, and marriage are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3. Demographic characterization revealed that the incidence of depressive symptoms was greater in females than in males at 2, 4, 7, and 9 years. The incidence was greater in rural areas than in urban areas and varied between regions, with the highest incidence in western regions. The higher the level of education, the lower the incidence of depressive symptoms, and the incidence of depressive symptoms at 4, 7, and 9 years was lower in married individuals than in those with other marital statuses. The 9-year data revealed that the 70–79 year age group had the highest incidence of depressive symptoms among the different age groups, and all the above differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Incidence characteristics of depressive symptoms

| Variables | Wave 1-2 | Wave 1-3 | Wave 1-4 | Wave 1-5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | DS | CI (%) | n | DS | CI (%) | n | DS | CI (%) | n | DS | CI (%) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 3 738 | 852 | 22.793 | 3 711 | 1024 | 27.594 | 3 416 | 1 125 | 32.933 | 2 990 | 1 079 | 36.087 | |||

| Male | 4 181 | 656 | 15.690 | 4 137 | 746 | 18.032 | 3 693 | 824 | 22.312 | 3 272 | 763 | 23.319 | |||

| P | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Age(year) | |||||||||||||||

| 45 ≤ age < 49 | 1 665 | 305 | 18.318 | 1 699 | 380 | 22.366 | 1 632 | 472 | 28.922 | 1 551 | 406 | 26.177 | |||

| 50 ≤ age < 59 | 2 971 | 608 | 20.464 | 2 994 | 675 | 22.545 | 2 875 | 792 | 27.548 | 2 637 | 796 | 30.186 | |||

| 60 ≤ age < 69 | 2 199 | 393 | 17.872 | 2 174 | 500 | 22.999 | 1 936 | 497 | 25.671 | 1 632 | 496 | 30.392 | |||

| 70 ≤ age < 79 | 944 | 177 | 18.750 | 867 | 187 | 21.569 | 618 | 175 | 28.317 | 422 | 139 | 32.938 | |||

| ≥ 80 | 140 | 25 | 17.857 | 114 | 28 | 24.561 | 48 | 13 | 27.083 | 20 | 5 | 25.000 | |||

| P | 0.159 | 0.906 | 0.277 | 0.017 | |||||||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Han | 6 295 | 1 201 | 19.079 | 481 | 112 | 23.285 | 495 | 139 | 28.081 | 392 | 104 | 26.531 | |||

| Others | 448 | 85 | 18.973 | 6 541 | 1451 | 22.183 | 6 614 | 1 810 | 27.366 | 5 515 | 1654 | 29.991 | |||

| P | 1 | 0.614 | 0.771 | 0.164 | |||||||||||

| Rural | |||||||||||||||

| City | 3 308 | 520 | 15.719 | 3 185 | 600 | 18.838 | 2 881 | 661 | 22.943 | 2 575 | 597 | 23.184 | |||

| Country | 4611 | 988 | 21.427 | 4 663 | 1170 | 25.091 | 4 228 | 1 288 | 30.464 | 3 687 | 1 245 | 33.767 | |||

| P | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| North-eastern | 606 | 80 | 13.201 | 593 | 101 | 17.032 | 524 | 116 | 22.137 | 453 | 115 | 25.386 | |||

| Eastern | 3 729 | 660 | 17.699 | 3 739 | 764 | 20.433 | 3 342 | 817 | 24.446 | 2 971 | 810 | 27.264 | |||

| Western | 2 311 | 561 | 24.275 | 2 284 | 640 | 28.021 | 2 103 | 700 | 33.286 | 1 795 | 606 | 33.760 | |||

| Central | 1 273 | 207 | 16.261 | 1 232 | 265 | 21.510 | 1 140 | 316 | 27.719 | 1 043 | 311 | 29.818 | |||

| P | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||

| Below the primary school | 3 143 | 738 | 23.481 | 3 115 | 892 | 28.636 | 2 704 | 907 | 33.543 | 2 203 | 862 | 39.128 | |||

| Primary school | 1 742 | 311 | 17.853 | 1 737 | 388 | 22.337 | 1 585 | 425 | 26.814 | 1 396 | 403 | 28.868 | |||

| Middle school | 1 869 | 301 | 16.105 | 1 883 | 347 | 18.428 | 1 739 | 408 | 23.462 | 1 640 | 391 | 23.841 | |||

| High school or above | 1 158 | 157 | 13.558 | 1 104 | 140 | 12.681 | 1 074 | 205 | 19.088 | 1016 | 183 | 18.012 | |||

| P | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Marriage | |||||||||||||||

| Married | 2 311 | 561 | 24.275 | 6 829 | 1494 | 21.877 | 6 253 | 1 686 | 26.963 | 5 568 | 1 578 | 28.341 | |||

| Others | 6 896 | 1 292 | 18.735 | 1 019 | 276 | 27.085 | 856 | 263 | 30.724 | 694 | 264 | 38.040 | |||

| P | 0.077 | < 0.001 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Total | 7 919 | 1 508 | 19.043 | 7 848 | 1770 | 22.554 | 7 109 | 1 949 | 27.416 | 6 262 | 1842 | 29.416 | |||

DS depressive symptoms, CI Cumulative incidence

Fig. 3.

Cumulative incidence and characteristics of depressive symptoms from 2011 to 2020

Analysis of studies on predicting the risk of developing depressive symptoms

Feature selection

In the training dataset, Lasso CV identified 30 features with non-zero coefficients: Rural, ADLs, Number of Number of chronic diseases, Leg pain, Waist pain, Knee pain, Arthritis or Rheumatism, Hypertension, Vision distance, Disability, Marriage, Ethnicity, Headache, Region, Age, BMI, Current smoking, Dyslipidemia, Episodic memory, Vision near, Sleep time at night, Cognitive ability, Mental status, Chronic lung diseases, Self-rated health, Self-assessed memory, Past smoking, Gender, Education, Satisfaction with life, optimizing the regularization parameter λ to 0.0021. The feature coefficients are shown in Table S5.

Machine learning model construction and evaluation

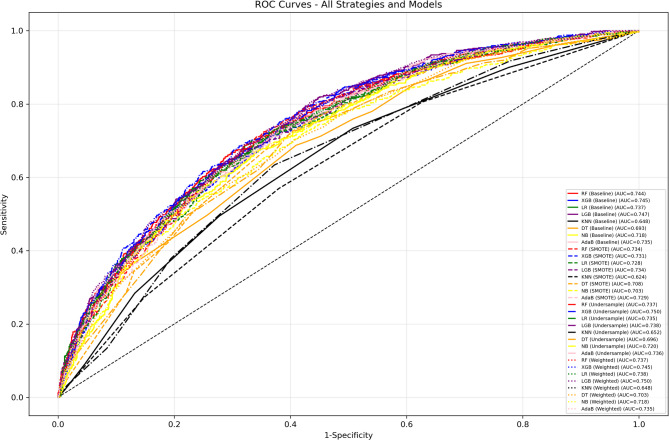

To predict the occurrence of depressive symptoms in 2020 based on the baseline features in 2011, eight machine learning models were constructed by incorporating 30 features screened by Lasso CV using baseline and three resampling (SMOTE, Random Under-Sampler, and Class Weight Adjustment) strategies for the training set. The show that LGB (0.747), XGB (0.745), LR (0.745), and RF (0.744) have similar AUC in Baseline, and have strong discriminatory ability for the risk of symptom onset after 9 years, while KNN (0.648) and DT (0.693) have significantly lower AUCs, and the Random Under-Sampler and Class Weighting strategies perform well. The Random Under-Sampler and Class Weight Adjustment strategies were outstanding, with the AUC of XGB and LGB exceeding 0.737 under both strategies, and the Random Under-Sampler strategy of XGB (0.750) and the Class Weight Adjustment strategy of LGB (0.750) were the best. KNN has the lowest AUC among all strategies (≤ 0.652) and is less robust. In terms of classification performance, the Baseline model is superior in accuracy (LGB 73.91%, LR 73.70%, etc.) and precision (LGB 64.00%, AdaB 64.65%), but the recall is only 24.82%−28.57%, which misses more than 70% of high-risk individuals. The RandomUnder-Sampler strategy significantly improves the recall of RF (70.71%), XGB (70.36%), and LGB (70.00%) by almost a factor of one, but the accuracy (e.g., LGB 66.77%) and precision (e.g., XGB 46.57%) decrease. The SMOTE strategy enhances the recall of NB (73.93%) and DT (72.14%), but leads to a decrease in the recall of models such as DT (63.63%), LGB (53.10%), and other models with decreased accuracy and precision. The Class Weight Adjustment strategy optimizes the recall of LR (66.07%) and LGB (66.07%), which is suitable for retaining the original data scenarios, but is ineffective for XGB and AdaB. The F1 scores show that Baseline is higher only for NB (0.5403). The F1 scores of models such as XGB (0.5605) under the Random Under-Sampler strategy are more than 0.55, which balances precision and recall and is suitable for long-term screening. The specific data are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4.

Table 2.

The predictive performance metrics for eight ML models using baseline and three resampling strategies in the testing set

| Resampling strategy | Model | Accuracy(%) | Precision(%) | Recall(%) | F1 Scores | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | RF | 73.54 | 61.54 | 30.00 | 0.4034 | 0.744 |

| XGB | 73.32 | 58.26 | 37.14 | 0.4537 | 0.745 | |

| LR | 73.7 | 59.32 | 37.5 | 0.4595 | 0.745 | |

| LGB | 73.91 | 64.00 | 28.57 | 0.3951 | 0.747 | |

| KNN | 69.38 | 47.75 | 28.39 | 0.3561 | 0.648 | |

| DT | 73.43 | 63.20 | 26.07 | 0.3692 | 0.693 | |

| NB | 66.29 | 45.53 | 66.43 | 0.5403 | 0.718 | |

| AdaB | 73.54 | 64.65 | 24.82 | 0.3587 | 0.735 | |

| SMOTE | RF | 70.39 | 50.37 | 49.11 | 0.4973 | 0.734 |

| XGB | 71.19 | 51.74 | 50.54 | 0.5113 | 0.731 | |

| LR | 69.38 | 48.87 | 57.86 | 0.5298 | 0.728 | |

| LGB | 71.78 | 53.10 | 45.89 | 0.4923 | 0.734 | |

| KNN | 60.49 | 38.90 | 56.96 | 0.4623 | 0.624 | |

| DT | 63.47 | 43.25 | 72.14 | 0.5408 | 0.708 | |

| NB | 60.92 | 41.32 | 73.93 | 0.5301 | 0.703 | |

| AdaB | 69.65 | 49.24 | 57.86 | 0.532 | 0.729 | |

| Under-sample | RF | 66.24 | 45.73 | 70.71 | 0.5554 | 0.737 |

| XGB | 67.09 | 46.57 | 70.36 | 0.5605 | 0.750 | |

| LR | 67.63 | 46.95 | 65.89 | 0.5483 | 0.735 | |

| LGB | 66.77 | 46.23 | 70 | 0.5568 | 0.738 | |

| KNN | 62.94 | 41.96 | 63.39 | 0.505 | 0.652 | |

| DT | 63.63 | 43.39 | 72.14 | 0.5419 | 0.695 | |

| NB | 70.50 | 50.50 | 53.93 | 0.5216 | 0.720 | |

| AdaB | 66.88 | 46.25 | 68.21 | 0.5512 | 0.736 | |

| Weighted | RF | 70.13 | 49.92 | 53.93 | 0.5185 | 0.737 |

| XGB | 73.32 | 58.26 | 37.14 | 0.4537 | 0.745 | |

| LR | 67.36 | 46.66 | 66.07 | 0.5469 | 0.738 | |

| LGB | 68.37 | 47.8 | 66.07 | 0.5547 | 0.750 | |

| KNN | 69.38 | 47.75 | 28.39 | 0.3561 | 0.648 | |

| DT | 62.62 | 42.33 | 70.00 | 0.5276 | 0.693 | |

| NB | 66.29 | 45.53 | 66.43 | 0.5403 | 0.718 | |

| AdaB | 73.54 | 64.65 | 24.82 | 0.3587 | 0.735 |

Fig. 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) for eight ML models using baseline and three resampling strategies on the testing set

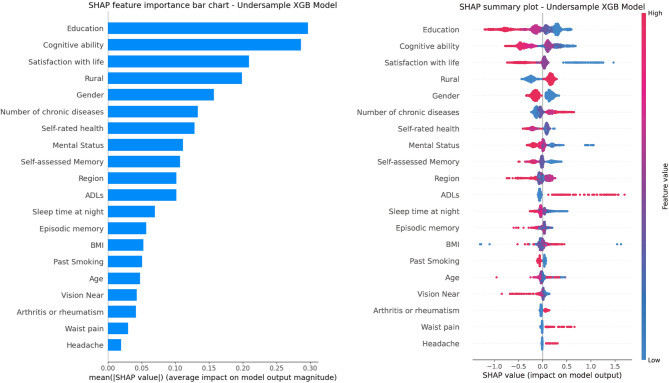

Model explanation

The average SHAP value bar (Fig. 5A) and SHAP summary plot (Fig. 5B), based on the XGB model with Random Under-Sampler, show that characteristics like “Education”, “Cognitive ability”, and “Satisfaction with life” (all > 0.2) have higher influence than others. “Rural”, “Gender”, “Number of chronic diseases”, “Self-rated health”, and “Mental status” also significantly influence the model. Conversely, “Sleep time at night”, “Episodic memory”, and BMI (< 0.10) have weaker effects. The summary plot reveals that low “Education” eigenvalues (red points) correlate with positive SHAP values, indicating an increased depressive risk, while high eigenvalues (blue points) are mostly negative, suggesting protection. Similar patterns occur with “Cognitive ability” and “Satisfaction with life”. Higher “Number of chronic diseases” (red dots) increase risk. For “Rural” (countryside = 1, city = 0) and “Gender” (male = 1, female = 0), the countryside (red dots) and female (blue points) tend to elevate depressive symptoms risk. Some features like “ADLs” and “Headache” show scattered SHAP values, indicating no clear pattern.

Fig. 5.

The mean SHAP value bar chart (A) and the SHAP summary plot (B) based on LGB algorithmic models

Discussion

In this study, the incidence characteristics of depressive symptoms in China’s middle-aged and elderly population were thoroughly analyzed using data from the CHARLS. The results of the present study revealed that the cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms increased between 2011 and 2020, with specific incidence rates of 19.043%, 22.554%, 27.416%, and 29.416% at the 2-, 4-, 7-, and 9-year observation points, respectively, which is by the results of previous studies [35–38]. Compared with the findings of Liili Abuladze’s study [39], the 2-year cumulative incidence was lower; compared with the study by Anouk F. J. Geraets et al. [40], the present study revealed a higher 7-year cumulative incidence. This difference may stem from differences in population characteristics and research methods. For gender, the cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms was consistently greater in females than in males, and this difference gradually increased over time, which is consistent with the findings of existing studies [36, 41]. In addition, the present study identified educational attainment as an important factor in the onset of depressive symptoms, with a significant decrease in the prevalence rate as educational attainment increased. This is consistent with the findings of Dong, Y et al. [42]. Concerning the effect of geographic area of residence, the incidence rate was consistently higher in rural areas than in urban areas, which is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in China [43], However, in developed countries, the findings contrast with those of the present study [44]. The regional differences were also significant, with the incidence rate being significantly higher in the western region than in the other regions for the entire follow-up period [45]. The present study also confirmed that the incidence rate of depressive symptoms significantly decreased with increasing education level. This may be because the western region has lagged behind other regions in terms of development due to economic, natural, and human demographic influences, leading to a greater prevalence of depressive symptoms in the western region. The present study also revealed that the incidence of depressive symptoms in individuals with other marital statuses was significantly greater than that of married individuals during the 4-year and later follow-up periods, which is in accordance with the findings of Jesús Cebrino et al. [46]. Gender, education, place of residence, region, and marriage are key factors for predicting the onset of depressive symptoms.

In this study, eight ML models were also constructed to predict the 9-year risk of depressive symptoms in the middle-aged and elderly populations using pre-sampling and three types of resampled data, respectively. It’s the first systematic comparison of these strategies in predicting the onset of depressive symptoms, which reveals the value and applicability scenarios of each strategy in long-term risk prediction compared with the existing studies of a single resampling strategy or a generalized dataset [47, 48], and provides the basis for optimizing the prediction algorithm of depressive symptom onset. The RandomUnder-Sampler notably enhances model performance; XGB, LGB, and RF achieved AUCs of 0.750, 0.738, and 0.737, with recall over 70%, nearly doubling the baseline, reducing missed diagnoses from 62.86% to 29.64%. Despite some accuracy and precision loss, it fits the public health goal of “early detection and early intervention”, and the misjudgment can be corrected by secondary assessment in clinical practice, which is suitable for long-term risk prediction of large-scale populations [49]. The SMOTE strategy improves the prediction sensitivity of NB and DT by synthesizing the samples (recall 73.93% and 72.14%), but the precision rate is only 41%−43%, which is suitable for emergency screening scenarios where high-risk individuals need to be targeted quickly. The Class Weight Adjustment strategy optimizes the performance of LR and LGB models without changing the sample distribution, with similar performance to RandomUnder-Sampler, but less effective for XGB and AdaB. Therefore, model selection needs to be closely centered on prediction needs: the RandomUnder-Sampler-XGB stood out with 70.36% recall, 0.5605 F1 score, and 0.750 AUC is the preferred choice for long-term risk prediction in large-scale populations. For quick, short-term, high-risk targeting, SMOTE-NB (73.93% recall) is ideal; for data-sensitive tasks, Class Weight Adjustment-LGB offers reliable prediction with authentic data.

We conducted SHAP analysis using the RandomUnderSampler-XGB algorithm to understand the influence of each feature on the model’s predictions. Key features included “Education”, “Cognitive ability”, and “Satisfaction with life”, all negatively linked to depressive symptoms—lower education, poorer cognition, and less satisfaction increase risk. We conducted SHAP analysis using the Random UnderSampler-XGB algorithm to understand the influence of each feature on the model’s predictions. Key features included “Education”, “Cognitive ability”, and “Satisfaction with life”, all negatively linked to depressive symptoms—lower education, poorer cognition, and less satisfaction increase risk. Education’s protective role may stem from stress-coping skills and health knowledge in highly educated individuals, or be confounded by economic and social factors, warranting further longitudinal study [50, 51]. Satisfaction with life directly reflects the predictive value of “subjective psychological experience” on depressive symptoms, which is in line with the “emotion-neuroimmune” association theory [52]. “Cognitive ability” reflects the bidirectional causality between cognitive decline and depressive symptoms [53]. Conversely, more chronic diseases correlate with higher depressive symptoms risk, as physical health issues heighten psychological stress [54]. Rural residence and female gender also increase risk due to resource scarcity and social pressures. The distribution of SHAP values for “ADLs”, “Headache,” and other traits was scattered, with no apparent polarization trend, suggesting that a single characteristic weakly influences these traits and that their association with depressive symptoms may be affected by confounders. Analyzing the importance of these traits helps target the stratification, prevention, and control of depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly people. First, high-risk groups, including those with low education, poor cognition, females, rural residents, and patients with chronic illnesses, are assessed through community exams, family doctor services, the CESD-10, and cognitive screening, with graded management based on risk scores. Education and mental support for low-education and poor cognition groups, social support networks and personalized home visits and counseling for those with low life satisfaction; outpatient clinics and integrated physical-mental care for chronic illness patients; and specific measures for women and rural areas, such as menopausal health management and family caregiver support provided for women, and the accessibility of mental health services in rural regions enhanced through the use of mobile psychosocial service vans and the training rural doctors. These precise prevention strategies aim to reduce depressive symptoms among high-risk groups and support China’s “Healthy China 2030” mental health goals.

One notable limitation is the absence of external validation on independent datasets, which may affect the generalizability of our model findings. Future studies should prioritize cross—dataset validation to further confirm the model’s robustness across diverse populations and settings.

Limitations

This study offers valuable insights into the prediction and screening of depressive symptoms in the middle-aged and elderly populations in China; however, it also has limitations. First, the absence of external validation on independent datasets, which may affect the generalizability of our model findings. Second, although longitudinal data are used, it remains an observational study, which makes it challenging to clarify cause and effect, and confounding factors may also have an impact. Third, multimodal data, such as brain images and genetic information, are not included, and objective tests, such as polysomnography, are missing, which limits the risk of modeling the complexity of the risk. Fourth, the assessment of depressive status utilizing CESD-10 may lead to omission or misdiagnosis. In the future, we need to integrate multimodal data, strengthen causal validation, and carry out cross-regional validation and intervention studies to enhance the clinical and public health value of the model, and to promote the prevention and control of depressive symptoms from “risk prediction” to “precision intervention”.

Conclusion

This study analyzed depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly individuals in China using the CHARLS data, yielding the following key findings. The cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms showed an increasing trend, with significant differences in gender, place of residence, and education level, and the risk was higher among females and people in the western region. The RandomUnder-Sampler-XGB model performed optimally in predicting the 9-year risk of depressive symptoms (recall = 70.36%, F1 = 0.5605, AUC = 0.750), which can serve as a long-term risk prediction tool for large-scale populations. SHAP analysis showed that education level, cognitive ability, and satisfaction with life were the core factors affecting the prediction of depressive symptoms, and residence, gender, and the number of chronic diseases were also important features, suggesting that multidimensional factors influenced the occurrence of depressive symptoms.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study team for providing data and training in using the datasets. We thank the students who participated in the survey for their cooperation. We thank all volunteers and staff involved in this research.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World health organization

- ML

Machine learning

- CHARLS

China health and retirement longitudinal study

- CDED-10

Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale-10

- BMI

Body mass index

- RFE

Recursive feature elimination

- RF

Random forest

- XGB

Extreme gradient boosting

- LR

Logistic regression

- LGB

Light gradient boosting machine

- KNN

K-nearest neighbor

- DT

Decision tree

- NB

Naive bayes

- AdaB

Adaptive boosting

- SHAP

Shapley additive properties

- CI

Cumulative incidence

- ADLs

Activities of daily living scale

- IADLs

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale

- HBP

High blood pressure

- Satlife

Satisfaction with life

- DSM-5

The Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition

- GBD

Global burden of disease

- NDRI

China national development research institute

- NIMH

National institute of mental health

- RFI

Random forest imputation

- SMOTE

Synthetic minority oversampling technique

- AUC-ROC

The area under the curve

- IQR

Interquartile range

- CFPS

China family panel studies

- SHARE

Survey of health, aging and retirement in Europe

Authors’ contributions

QH: conceptualization, writing—review, editing, supervision, and funding acquisition; ZJ: formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, and visualization. MH: machine learning modelling and analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Key Project of the Anhui Provincial Education Department (no. 2023AH051915) and Natural Science Key Project of Bengbu Medical University (no. 2023byzd031; no. 2021byzd035).

Data availability

Data were publicly available at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The baseline and follow-up surveys of CHARLS were obtained from the Peking University Ethics Review Board (IRB00001052-11015) approval, and all respondents signed an informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qing Huang and Zihao Jiang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Depression and other common mental disorders:global health estimates (No. WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2). 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell AJ, Subramaniam H. Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong S, Lu B, Wang S, Jiang Y. Comparison of logistic regression and machine learning methods for predicting depression risks among disabled elderly individuals: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25(1):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, Ustün TB, Wang PS. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni X, Su H, Lv Y, Li R, Chen C, Zhang D, Chen Q, Zhang S, Yang Z, Sun L, et al. The major risk factor for depression in the Chinese middle-aged and elderly population: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:986389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maier A, Riedel-Heller SG, Pabst A, Luppa M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5): e0251326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds CF 3rd, Cuijpers P, Patel V, Cohen A, Dias A, Chowdhary N, Okereke OI, Dew MA, Anderson SJ, Mazumdar S, et al. Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang JC, Ko KM, Shu MH, Hsu BM. Application and comparison of several machine learning algorithms and their integration models in regression problems. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(10):5461–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ai F, Li E, Ji Q, Zhang H. Construction of a machine learning-based risk prediction model for depression in middle-aged and elderly hypertensive people in China: a longitudinal study. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1398596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li R, Wang X, Luo L, Yuan Y. Identifying the most crucial factors associated with depression based on interpretable machine learning: a case study from CHARLS. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1392240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu JM, Gao M, Zhang R, Wong NML, Wu J, Chan CCH, Lee TMC. A machine-learning approach to model risk and protective factors of vulnerability to depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;175:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenland S. Invited commentary: variable selection versus shrinkage in the control of multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(5):523–9 (discussion 530-521). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams MW, Li CY, Hay CC. Validation of the 10-item center for epidemiologic studies depression scale post stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(12): 105334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu CS, Lian ZW, Cui YM. Association between depression and number of chronic diseases among middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Beijing da xue xue bao Yi xue ban = Journal of Peking University Health sciences. 2023;55(4):606–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong NM, Deal JA, Betz J, Kritchevsky S, Pratt S, Harris T, Barry LC, Simonsick EM, Lin FR. Associations of hearing loss and depressive symptoms with incident disability in older adults: health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(3):531–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hairi NN, Bulgiba A, Cumming RG, Naganathan V, Mudla I. Depressive symptoms, visual impairment, and its influence on physical disability and functional limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):557–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Yaohui WY, Chen XX. Zhong guo jian kang yu yang lao bao gao. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyon I, Elisseeff A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J Mach Learn Res. 2003;3:1157–82. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2012;28(1):112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fatih C. Lasso Regression Model [Technical Report], vol. ResearchGate. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allah EMA, El-Matary DE, Eid EM, DienASTEJJoC, Communications. Performance Comparison of Various Machine Learning Approaches to Identify the Best One in Predicting Heart Disease. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian W, Zhang Y, Han X, Li Y, Liu J, Wang H, Zhang Q, Ma Y, Yan G. Development and validation of a predictive model for depression risk in the U.S. adult population: evidence from the 2007–2014 NHANES. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1): 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liaw A, Wiener MC. Classification and Regression by randomForest. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen T, GuestrinCJPotnASICoKD, Mining D. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oikonomou EK, Khera R. Machine learning in precision diabetes care and cardiovascular risk prediction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T, Wang T, Chen W, Ma W, Ye Q, Liu T-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In: Neural Information Processing Systems: 2017. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischbach MA. Problem choice and decision trees in science and engineering. Cell. 2024;187(8):1828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viaene S, Derrig RA, Dedene G. A case study of applying boosting naive Bayes to claim fraud diagnosis. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2004;16(5):612–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatwell J, Gaber MM, Atif Azad RM. Ada-WHIPS: explaining AdaBoost classification with applications in the health sciences. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundberg SM, Lee S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Long Beach: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 4768–77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.He D, Wang Z, Li J, Yu K, He Y, He X, Liu Y, Li Y, Fu R, Zhou D, et al. Changes in frailty and incident cardiovascular disease in three prospective cohorts. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(12):1058–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daly M. Prevalence of depression among adolescents in the U.S. from 2009 to 2019: analysis of trends by sex, race/ethnicity, and income. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):496–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu BP, Huxley RR, Schikowski T, Hu KJ, Zhao Q, Jia CX. Exposure to residential green and blue space and the natural environment is associated with a lower incidence of psychiatric disorders in middle-aged and older adults: findings from the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dibato J, Montvida O, Ling J, Koye D, Polonsky WH, Paul SK. Temporal trends in the prevalence and incidence of depression and the interplay of comorbidities in patients with young- and usual-onset type 2 diabetes from the USA and the UK. Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):2066–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abuladze L, Opikova G, Lang K. Factors associated with incidence of depressiveness among the middle-aged and older Estonian population. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8: 2050312120974167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geraets AFJ, Köhler S, Vergoossen LW, Backes WH, Stehouwer CDA, Verhey FR, Jansen JF, van Sloten TT, Schram MT. The association of white matter connectivity with prevalence, incidence and course of depressive symptoms: the Maastricht study. Psychol Med. 2023;53(12):5558–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu X, Guo C. Temporal trends and cohort variations of gender-specific major depressive disorders incidence in China: analysis based on the age-period-cohort-interaction model. Gen Psychiatr. 2024;37(4): e101479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong Y, Yang FM. Insomnia symptoms predict both future hypertension and depression. Prev Med. 2019;123:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y, Su B, Chen C, Zhao Y, Zhong P, Zheng X. Urban-rural disparities in the prevalence and trends of depressive symptoms among Chinese elderly and their associated factors. J Affect Disord. 2023;340:258–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purtle J, Nelson KL, Yang Y, Langellier B, Stankov I, Diez Roux AV. Urban-rural differences in older adult depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):603–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tao HW, Zhang X, Wang Z. Depressive status and influencing factors among rural elderly in eastern, central, and western regions of China. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2018;22(7):696–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cebrino J, Portero de la Cruz S. Diet Quality and Sociodemographic, Lifestyle, and Health-Related Determinants among People with Depression in Spain: New Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study (2011-2017). Nutrients. 2020;13(1):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nam SM, Peterson TA, Seo KY, Han HW, Kang JI. Discovery of depression-associated factors from a nationwide population-based survey: epidemiological study using machine learning and network analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6): e27344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia F, Li Q, Luo X, Wu J. Machine learning model for depression based on heavy metals among aging people: a study with National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2018. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 939758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in medicine. 2008;27(2):157–72. discussion 207-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cintron DW, Calmasini C, Barnes LL, Mungas DM, Whitmer RA, Eng CW, Gilsanz P, George KM, Peterson RL, Glymour MM. Evaluating interpersonal discrimination and depressive symptoms as partial mediators of the effects of education on cognition: evidence from the study of healthy aging in African Americans (STAR). Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(7):3138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L, Sun W, Luo J, Huang H. Associations between education levels and prevalence of depressive symptoms: NHANES (2005–2018). J Affect Disord. 2022;301:360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Y, Xu H, Sui X, Zeng T, Leng X, Li Y, Li F. Effects of group reminiscence interventions on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in older adults with intact cognition and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;114: 105103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Y, Chen A, Chen R, Zheng W. Association between depressive symptoms and cognitive function in the older population, and the mediating role of neurofilament light chain: evidence from NHANES 2013–2014. J Affect Disord. 2024;360:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Read JR, Sharpe L, Modini M, Dear BF. Multimorbidity and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data were publicly available at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en.