Abstract

The development of artificial catalysts with efficiency that can rival those of Nature’s enzymes represents one of the foremost yet challenging goals in homogeneous metal catalysis. Inspired by the exceptional performance of metalloenzymes, the design and development of highly efficient bi/multinuclear catalysts via judicious ligand design, by taking advantage of the cooperative action of the proximal catalytic sites, has attracted great attention. Herein, we report the self-assembly of a chiral hexadentate BINOL-dipyox ligand with zinc acetate into a well-defined trinuclear zinc complex, which demonstrated ultrahigh catalytic productivity in the enantioselective hydroboration of ketones with an unprecedented turnover number (TON) of 19,400 at an extremely low catalyst loading (0.005 mol %). Mechanistic investigations reveal that a cooperative Lewis acid activation mode is operating in the catalytic process, hence, underscoring the unique advantages of the trinuclear architecture.

I. Introduction

The development of catalysts with extremely high efficiency is of paramount importance in catalytic synthetic chemistry, and numerous paradigms for efficient catalysts can be found in enzymes, − with spatially organized multifunctional active sites for exceptional selectivity and efficiency in biological transformations. In this context, there are increasing studies on the development of bi/multinuclear metallic catalysts that mimics the metalloenzymes’ activation siteswhere cooperative interactions between adjacent metal centers, leading to catalysts with significantly improved efficiency and selectivity as compared to their mononuclear analogues. − For instance, zinc was known to play critical roles in biological processes involving metalloenzymes such as phosphotriesterase − and P1 nuclease, − containing two or three zinc ions at their active sites (Figure a), respectively. These have inspired the development of some of the most successful bi/multinuclear zinc catalysts to date, − such as Trost’s dinuclear zinc-ProPhenol catalysts − and Shibasaki’s zinc/Linked-BINOL catalysts. − Despite these significant advancements, however, the development of highly active chiral zinc catalysts that are capable of simultaneously achieving robust catalytic efficiency and precise enantioselective control remains a critical challenge, especially for chiral tri-Zn catalysts. A key to addressing this challenge is the strategic design of multidentate ligands, which can keep the transition metal ions spatially well-organized within catalytic frameworks.

1.

Zinc-containing metalloenzymes and artificial chiral trinuclear Zn catalysts. (a) Multi-Zn-containing metalloenzymes. (b) Design of the BINOL-dipyox ligand. (c) Tri-Zn catalyst. (d) Exceptionally high efficiency in catalytic hydroboration of ketones.

Among the numerous chiral ligands developed so far, BINOL stands out for asymmetric catalysis due to its cost-effectiveness, structural tunability, and stereochemical rigidity. Particularly, the ligand is modifiable at the 3,3′-positions with donor or steric groups, rendering it a highly attractive feature for diversification. − It is also worthy to note that chiral pyridine-oxazolines (pyox) have proven to be a class of highly effective ligands for transition metal catalyzed asymmetric reactions. , We envisioned that by integrating BINOL with the pyox modules into a single hybrid ligand framework, the resulting chiral N, N, O, O, N, N-hexadentate ligands may be capable of forming di/multinuclear catalytic systems to address synthetic challenges in high efficiency (Figure b).

Transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of ketones is a pivotal strategy for constructing chiral alcohols. − Nevertheless, studies on the Zn-catalyzed enantioselective variants of this reaction remain rare, − despite zinc catalysts’ unique advantages of low cost, natural abundance, and reduced toxicity. − Herein, we report the rational design and synthesis of a novel chiral BINOL-dipyox ligand, which assembles with the zinc salt to form a well-defined trinuclear zinc complex (Figure c). This tri-Zn system demonstrated an unprecedented efficiency (as low as 0.005 mol %) in the asymmetric hydroboration of ketones, providing access to various chiral alcohols with high enantioselectivities (Figure d). Mechanistic studies suggested that the extraordinary activityfar exceeding conventional mononuclear Zn systemsmight originate from synergistic interactions of two reactants within the trinuclear core. This work not only establishes a new benchmark for low-loading zinc catalysis but also provides a blueprint for engineering multinuclear architectures to amplify cooperative effects in asymmetric transformations.

II. Results and Discussion

1. Ligand Synthesis and Self-Assembly of the Tri-Zn Complexes

As illustrated in Figure a, the chiral BINOL-dipyox ligand L1 was synthesized concisely through a four-step sequence. The preparation commenced with commercially available (S)-2,2′-bis(methoxymethoxy)-1,1′-binaphthalene (S 1 ), which was converted into diboronate derivative S 2 in 87% isolated yield by treatment with n BuLi and i PrO-BPin. Concurrently, 6-bromo-2-pyridinecarboxylic acid S 3 was condensed with chiral aminoalcohol S 4 under amide coupling conditions to furnish 6-bromo-2-pyridinecarboxamide S 5 in 76% yield. Subsequently, a palladium-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling between S 2 and S 5 delivered the bis-pyridyl intermediate S 6 bearing the key BINOL-dipy framework in 93% yield. Selective removal of the methoxymethyl (MOM) groups on S 6 followed by treatment of the deprotected intermediate with DAST (diethylaminosulfur trifluoride) effectively promoted the oxazoline ring formation, ultimately affording the target BINOL-dipyox ligand L1 in 60% overall yield for the two steps. A series of BINOL-dipyox ligands L2-L7 were also successfully synthesized by following a similar procedure.

2.

Synthesis of the ligand and self-assembly of the tri-Zn complex. (a) Synthesis of L1. (b) 1H NMR analysis. (c) Synthesis of Zn3 L1.

With these multidentate ligands in hand, their coordination propensity was evaluated by treating L1 with varying amounts of zinc acetate (1 to 3 equiv) under ambient conditions to probe into the preferential formation of mono-, bi-, or trinuclear complexes. 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixtures revealed signals with a pronounced downfield shift for the oxazoline protons (Figure b), which could be attributed to zinc coordination. Intriguingly, irrespective of the molar ratios of Zn-to-ligand (1:1, 2:1, or 3:1) in the system, the dominant ligated species formed in the mixtures exhibited identical spectral signatures at 4.12, 4.53, and 4.68 ppm, suggesting that the ligand is prone to adopt such a specific coordination architecture with the Zn(II) ions. The 1H NMR spectrum for the 3:1 Zn-to-ligand mixture revealed a set of signals with chemical shifts distinct from those of L1, suggesting an exclusive formation of Zn3 L1-type species in this system. In contrast, the 1H NMR spectra for both the 2:1 and 1:1 Zn-to-ligand mixtures showed the same signals as the 3:1 mixture, along with the signals that are characteristic of the free ligand. These observations indicated that hexadentate L1 has a strong propensity to undergo selective self-assembly with Zn(II) ions, leading to the preferential formation of a trinuclear complex (Zn3 L1). The metal-to-ligand stoichiometry appears to have little effect under these conditions, as no alternative complexes (e.g., Zn1 L1 or Zn2 L1) were detected. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of the trinuclear complex (Figure c) unambiguously established its Zn3 L1 moiety in the structure. The complex features three Zn(II) centers coordinated with distinct donor atoms in L1 and bridged by two acetate ions. While the outer two Zn ions are bound by two pyridine-oxazoline moieties, respectively, the central Zn is coordinated by the two BINOL-derived oxygen atoms. Notably, the axial chirality of the BINOL scaffold induces a pronounced helical distortion (torsion angle = −100.7°), creating a sterically accommodating cavity that stabilizes the trimetallic core. Two acetate ligands adopt μ2-bridging modes, completing the tetrahedral geometry at each Zn(II) center.

2. Reaction Development and Unprecedented Efficiency

4-Acetylbiphenyl was initially selected as the standard substrate for Zn-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration using pinacolborane (HBpin) as the hydroboration reagent (Table ). The reaction proceeded smoothly in THF at room temperature using (S, S, S)-L1 (2.0 mol %)/Zn(OAc)2 (6.0 mol %) as the chiral catalyst, giving the desired alcohol 2a in 99% yield with 90% enantiomeric excess (ee), thus demonstrating the feasibility of using trinuclear Zn for the catalytic asymmetric hydroboration of ketones (Entry 1). Notably, when using (R, S, S)-L1 in the reaction, wherein the chirality of the oxazoline moiety was maintained while inverting the chirality of the BINOL scaffold, the enantiomer of 2a was obtained with a slightly decreased ee value of 80% (Entry 2), suggesting that the chirality of BINOL backbone might play a key role in dictating the facial attack of the hydride species on the ligated carbonyl group. Using (R, R, R)-L1 also afforded the enantiomer isomer in 99% yield with 90% ee (Entry 3). When the t Bu group on the oxazoline moiety was replaced by Bn ((S, S, S)-L2), the catalyst exhibited slightly lower activity, and the reaction gave the desired product in 92% yield with 89% ee (Entry 4). Altering the chirality of the oxazoline moiety to R (using (S, R, R)-L2) led to a further minor decrease in both the product yield and ee value (Entry 5), though the absolute configuration of the product remained unchanged, further attesting that the chiral induction of the catalysis is likely to be dominated by the absolute configuration of the BINOL moiety. These results (entries 1–5) indicate that the chirality of the BINOL unit in the ligand is critical as it determines the configuration of the product, while the chirality of the oxazoline moiety plays a secondary role in modulating the ee value. These results also indicate that the ligand with a S-configured BINOL skeleton and a S-configured oxazoline moiety is chirally matched for the current reaction. Therefore, (S, S, S)-ligands (L3-L6) with different substituents on the oxazoline moiety were further investigated, and the ligands with naphthalenemethyl, ethyl, and isopropyl afforded the same results as that of t Bu (entries 1, 6–8). The reaction using (S, S, S)-L6 with a phenyl group on the oxazoline led to a slightly lower yield (88%) and ee (88%) (Entry 9). Reducing the reaction temperature to 10 °C increased the ee to 92% using L1 (Entry 10). To elucidate the catalytic role of the chiral hexadentate ligand, systematic ligand modification studies were conducted. Primary modification involved methyl-protection of the phenolic hydroxyl group in the BINOL-dipyox ligand. This protection resulted in almost complete loss of stereochemical control, yielding the racemic product with significantly declined efficiency (entry 11, 34% yield). Furthermore, the reaction using monofunctionalized BINOL-pyox L8 demonstrated poor catalytic performance, achieving only 16% yield with 16% ee (Entry 12). These results prompted us to hypothesize that the zinc ion coordinated to the phenolic hydroxyl group might play a crucial role in activating ketone carbonyl for the stereodiscriminated attack by the boronate hydride. Notably, control experiments employing BINOL, pyridine-oxazoline, or their ligand mixtures (entries 13–15) only demonstrated poor catalytic performance (<6% ee), which are in starking contrast with the superior efficiency of the BINOL-dipyox (90% ee). Such a dramatic difference further consolidates the advantages of the rationally designed chiral polydentate ligands in achieving enantioselective hydroboration reactions of ketones. Interestingly, using the pre-prepared tri-Zn complex Zn3 L1 directly as the catalyst (2.0 mol %) achieved full conversion and gave the desired product 2a with a slightly lower ee (84%). However, when KOAc (1.0 or 10 mol %) was added to the tri-Zn complex catalyzed reaction, the ee was improved to match that of the in situ-formed tri-Zn system (90%), suggesting that the OAc– anion generated during the self-assembly of Zn(OAc)2 and L1 may play a role in chiral control.

1. Screening of the Ligands .

| Entry | L* | Conv. of 1a (%) | Yield of 2a (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (S, S, S)-L1 | >99 | 99 | 90 (S) |

| 2 | (R, S, S)-L1 | >99 | 99 | –80 (R) |

| 3 | (R, R, R)-L1 | >99 | 99 | –90 (R) |

| 4 | (S, S, S)-L2 | 93 | 92 | 89 (S) |

| 5 | (S, R, R)-L2 | 90 | 89 | 88 (S) |

| 6 | (S, S, S)-L3 | >99 | 99 | 90 (S) |

| 7 | (S, S, S)-L4 | >99 | 99 | 90 (S) |

| 8 | (S, S, S)-L5 | >99 | 99 | 90 (S) |

| 9 | (S, S, S)-L6 | 89 | 88 | 88 (S) |

| 10 | (S, S, S)-L1 | 99 | 99 | 92 (S) |

| 11 | (S, S, S)-L7 | 45 | 34 | rac. |

| 12 | L8 | 24 | 16 | 16 (S) |

| 13 | L9 | 93 | 90 | rac. |

| 14 | L10 | 17 | 15 | 6 (S) |

| 15 | L9 + L10 | 22 | 17 | 4 (S) |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), HBpin (2.0 equiv), L* (2 mol %), Zn(OAc)2 (6 mol %), THF, r.t., 4 h.

The conversion of 1a was determined by GC using n-decane as the internal standard.

Isolated yield.

The ee values of 2a were determined by chiral HPLC

10 °C, 24 h.

L* (6 mol %)

During the optimization of the reaction conditions, it was found that the catalyst was highly active, and the reactant 1a could be fully consumed in a short time (4 h). Therefore, the reactions of 1a and HBpin were carried out under gradually reduced catalyst loadings (Table ). A survey of L1 with loadings ranging from 2 to 0.005 mol % revealed that the reaction still proceeds smoothly at an extremely low catalyst loading (0.005 mol % Zn3/L1), affording the product in 97% yield with 90% ee (Entry 6). Further reducing the catalyst loading to 0.002 mol %, the reaction product was still obtained in excellent yield (93%), albeit with a slightly lower ee (80%, Entry 7). However, without a chiral ligand, 0.015 mol % Zn(OAc)2 exhibited some catalytic activity in the reaction, albeit with low efficiency, indicating a ligand-accelerated catalysis in this system (entry 9). These results demonstrated the robust catalytic performance of the BINOL-dipyox-Zn3 catalyst in the reaction, particularly at very low catalyst loadings. Notably, kinetic studies showed that the reaction rate decreased concomitantly with a reduction in the Zn(OAc)2 (0.1x mol %) to L1 (0.1 mol %) ratio (x = 3, 2, 1), suggesting that a 3:1 ratio of Zn(OAc)2-to-L1 is crucial for achieving an efficient and highly enantioselective asymmetric hydroboration of ketones (for details, see the ).

2. Optimizing the Reaction Conditions .

| Entry | L1 (mol %) | Time (h) | Conv. (%) | ee (%) | TON |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | >99 | 90 | - |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | >99 | 90 | - |

| 3 | 0.1 | 6 | >99 | 90 | - |

| 4 | 0.1 | 24 | 99 (98) | 92 | - |

| 5 | 0.01 | 12 | >99 | 90 | - |

| 6 | 0.005 | 24 | 99 (97) | 90 | 19,400 |

| 7 | 0.002 | 48 | 99 (93) | 80 | 46,500 |

| 8 | 0.001 | 48 | 50 | 79 | - |

| 9 | - | 24 | 22 | rac. |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1–200 mmol), (S, S, S)-L1 (0.002 mmol), Zn(OAc)2 (0.006 mmol), THF (1–270 mL), r.t.

The conversion of 1a was determined by GC using n-decane as the internal standard.

The ee values of 2a were determined by chiral HPLC.

0 °C.

Isolated yield in parentheses.

Zn(OAc)2 (0.015 mol %), without a chiral ligand.

To further extend the generality of the BINOL-dipyox-Zn3 catalyst in asymmetric hydroboration, we investigated the scope of ketones using 0.1 mol % Zn3/L1 as the catalyst (Figure ). Remarkably, this catalytic system demonstrates exceptional generality across a diverse range of ketones. Both electron-donating (-Ph, -Me, -OMe, -OEt) and electron-withdrawing substituents (-F, -Cl, -Br, -CF3, -NO2) on the ketones were tolerated, delivering the corresponding chiral alcohol products 2a-2s with high efficiency (80–99% yields) and good to excellent stereocontrol (80–97% ee). The (hetero)aromatic ketones also worked well in the protocol, and the reactions of naphthyl derivatives (2t, 2u: 96–99% yields, 85% ee and 80% ee), thiophene-containing substrates (2v, 2w: 92–93% yields, 84–92% ee), and 1,3-benzodioxole analogues (2x; 99% yield, 91% ee) proceeded smoothly. It is noteworthy that the reactions of sterically demanding fused aromatic rings afforded their corresponding products [i.e., with five- (2y-2z), six- (2aa-2ad), and seven-membered (2ae) systems] in excellent yields (90–99%) with high enantioselectivities (86–97% ee). Furthermore, diverse heterocyclic substrates such as 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinolin-8-one, thiochroman-4-one, and 4-chromanone proved to be amenable to the procedure, affording the corresponding chiral alcohols 2af-2ah with remarkable efficiency (83–97% yields) and good stereochemical control (82–96% ee). In addition, 4-chlorobutyrophenones performed quite well in the reaction, providing the corresponding chlorohydrin products 2ai and 2aj in excellent yields (both 96%) and ee values (96% and 88%), respectively.

3.

Substrate scope. Reaction conditions: 1 (2 mmol), (S, S, S)-L1 (0.1 mol %), Zn(OAc)2 (0.3 mol %), rt, 12 h. a 0 °C, 24 h. b 1 (0.1 mmol), (S, S, S)-L1 (2 mol %), Zn(OAc)2 (6 mol %), r.t., 4 h. c (R, R, R)-L1 (0.1 mol %) was used. Isolated yield.

Notably, the chiral alcohols 2ak-2am represent key synthetic intermediates for several clinically important agents, including the NK1 receptor antagonist aprepitant, σ1 receptor antagonist WLB-87848 and the antidepressants fluoxetine, respectively, were also obtained in high yields with good to excellent enantioselectivities using the protocol (93–99% yields, 82–92% ee). Furthermore, chiral alcohol 2an can be synthesized in 97% yield with 84% ee. This intermediate underwent cyclization to generate chiral tetrahydrofuran 3an smoothly, which serves as a strategic precursor for accessing AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activators.

3. Mechanistic Studies

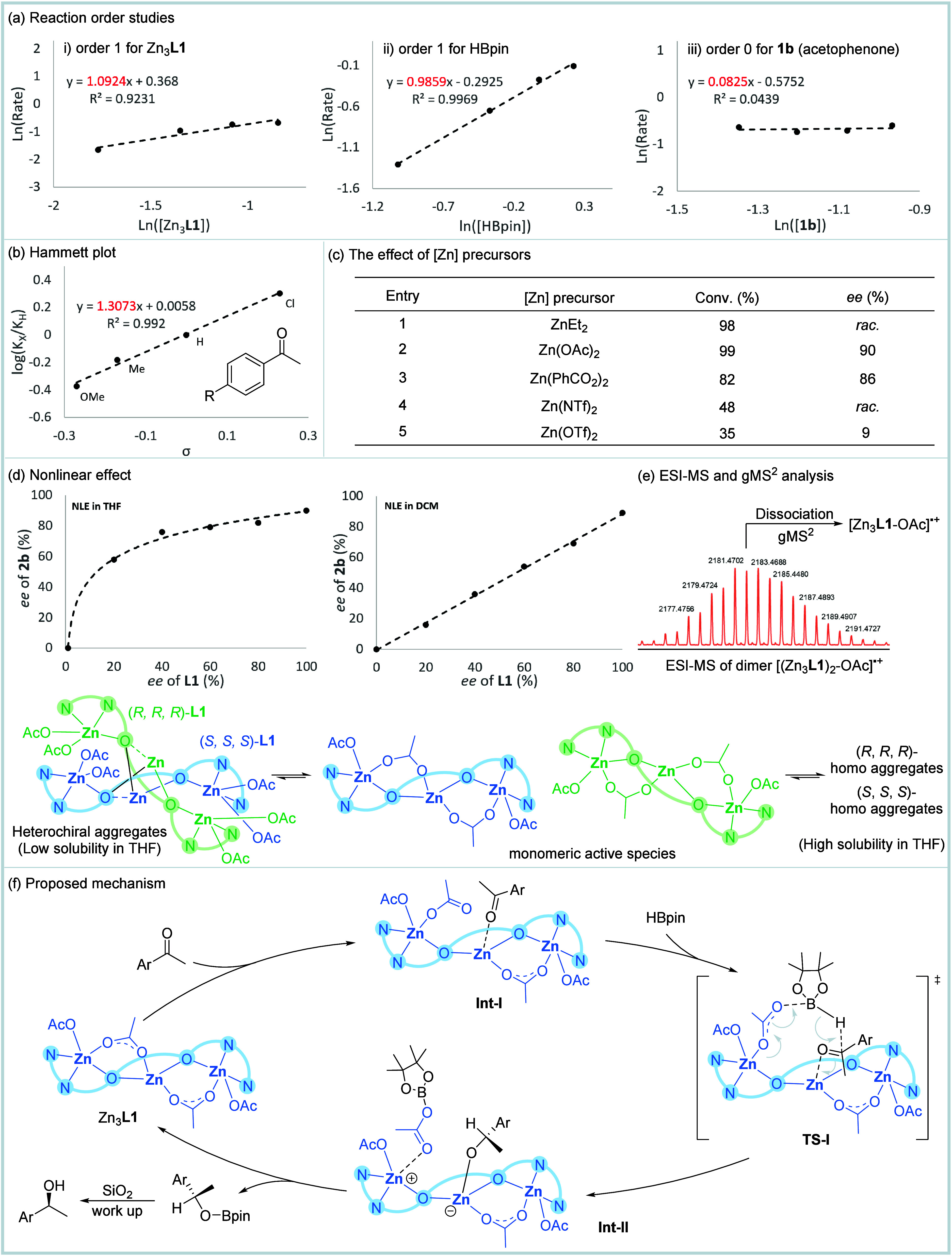

Two distinct mechanistic pathways have been proposed for zinc-catalyzed hydroboration of ketones, i.e., (i) Lewis acid activation of the ketone by carbonyl coordination to the Zn center, ,, and (ii) in situ formation of zinc-hydride species as the catalytically active intermediates. − To elucidate the operating mechanism of the current catalytic system, we conducted a series of mechanistic investigations, including reaction kinetic order studies using acetophenone (1b), Hammett analysis and the nonlinear effects (Figure ). The initial rate of the reaction exhibited a linear dependence on the catalyst concentration, suggesting that the trinuclear Zn core is most likely to be involved in the rate-limiting step and to remain largely intact over the entire course of catalysis (Figure a). Furthermore, a linear correlation between the reaction rate and HBpin concentration was also observed, indicating that a molecule of boronate hydride should also be involved in the turnover-limiting step. In contrast, variation in acetophenone 1b concentration exhibited a negligible impact on initial rate, indicating that the ketone is unlikely to be involved in the rate-determining step. Next, Hammett analysis was carried out on para-substituted acetophenone 1, to probe the electronic effect of the ketone on the rate of the reaction. This analysis discloses a positive ρ value (1.31) of the slope, showing that the reaction is more favorable in the presence of an electron-withdrawing group on the ketones (Figure b). Integration of the Hammett study and the observed zero-order kinetics of acetophenone suggests that acetophenone may coordinate with the catalyst, forming a pre-equilibrium before the rate-determining step. These findings may provide mechanistic evidence for HBpin mediated nucleophilic addition to a zinc-polarized carbonyl intermediate, wherein the Lewis acidic Zn center activates the ketone substrate, rendering the electrophilic carbon susceptible to borane attack. This is also consistent with first order for Zn3 L1 and HBpin, but zero order for ketone 1b in the reaction since 1b has been coordinated with Zn3 L1.

4.

Mechanistic studies. (a) Reaction order studies. (b) Hammett plot. (c) The effect of [Zn] precursors. (d) Nonlinear effect. (e) ESI-MS and gMS2 analysis. (f) Proposed mechanism.

To elucidate the potential involvement of Zn–H intermediates in the current catalytic system, the Zn3 L1 complex (1.0 equiv) was mixed with HBpin (3.0 equiv) in CDCl3. Notably, 1H NMR analysis revealed characteristic Zn–H vibrational signals (δ 4.6 ppm, consistent with literature reports ,, ). Given that Et2Zn serves as a conventional Zn precursor for generating Zn–H species in hydroboration reactions, − Zn(OAc)2 was replaced with Et2Zn under the standard conditions. However, this modification yielded only racemic product in 98% yield (Figure c), suggesting that while trace Zn–H species might form, they likely do not contribute to the catalytic cycle. Further investigations into anionic effects using alternative Zn precursors revealed carboxylate anions (e.g., –OAc, PhCO2 –) to be critical for achieving high activity and ee. In contrast, Zn(NTf)2, Zn(OTf)2, and ZnBr2 resulted in markedly reduced conversion and ee values. Collectively, these results using different Zn precursors highlight the essential role of acetate anions in both catalytic efficiency and chiral induction and also indicate that Zn–H species is less likely to be active in the current reaction.

The nonlinear effect (NLE) for the Zn3 L1 catalyzed hydroboration of ketones was also investigated with (S, S, S)-L1 in different enantiomeric purities in THF. The relationship between the ee values of product 2b and ligand L1 showed that an obvious positive nonlinear effect existed (Figure d). This observation suggested that oligomeric aggregates may exist in the reaction system. − Notably, we observed a distinct solubility difference between these diastereomeric complexes, and the heterochiral aggregate shows poor solubility in the reaction solvent (THF) compared with its homochiral counterparts. Particularly, combinations of Zn(OAc)2 with (S, S, S)-L1 at varying enantiopurities are completely soluble in CH2Cl2. Corresponding NLE experiments conducted in CH2Cl2 revealed a linear correlation, indicating that the observed positive nonlinear effect in THF most likely originates from the poor solubility of heterochiral aggregates in that reaction solvent. The reaction mixture (1:1) of (S, S, S)-Zn3 L1 and (R, R, R)-Zn3 L1 complexes was analyzed by ESI-MS (Figure e). The MS peak of dimer species at m/z 2183.4688 (m/z calcd for [(Zn3 L1)2–OAc]+ 2183.2686) was observed, which was subsequently analyzed by gMS2, and the MS peak of monomer at m/z 1061.2119 (m/z calcd for [Zn3 L1–OAc]+ 1061.1323) was further observed. Combined with the reaction order studies (first order on tri-Zn), the above results suggested that monomeric complex Zn3 L1 most likely functions as the active and effective catalytic intermediate, and limited dimerization or oligomerization may also occur between tri-Zn species to form out-cycle species.

Based on the above results, a possible mechanism for the process is proposed in Figure f. The catalytic cycle commences with the coordination of the carbonyl substrate to Zn3 L1, forming intermediate Int-I. Subsequent bimolecular interaction with HBpin proceeds through a concerted transition state (TS-I) to form Int-II that exhibits a first-order kinetic dependence on both Zn3 L1 and HBpin concentrations. This step involves a process where zinc-mediated polarization of the carbonyl group, significantly enhancing its electrophilicity, and simultaneous B–H bond activation in HBpin through its interaction to the acetate of Zn3 L1. The third Zn (II) might maintain the structural stability of the chiral catalyst. The reaction order studies and Hammett plot indicated that this step, the addition of hydride from HBPin to ketone, is most likely the rate-determining step. Then, dissociation of Int-II regenerates the active catalyst Zn3 L1 while releasing the [O-Bpin] species. After the reaction, silicate workup converts the [O-Bpin] species into the corresponding chiral alcohol product. While experimental mechanistic investigations suggest the proposed mechanism as the dominant pathway, the intricate nature of the trinuclear catalytic system permits the existence of alternative routes that cannot be ruled out. It is proposed that the intrinsic origin of the unprecedented activity in the asymmetric hydroboration of ketones lies in the synergistic activation of dual substrates by the trinuclear zinc centers and the confined reaction microenvironment within the self-assembled architecture.

III. Summary and Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a class of self-assembled trinuclear chiral zinc complexes using earth-abundant Zn(II) ions and rationally designed chiral BINOL-dipyox ligands. The chiral tri-Zn system demonstrated unparalleled catalytic efficiency in the asymmetric hydroboration of ketones, achieving a turnover number (TON) of 19,400 with a catalyst loading of 0.005 mol %, which is unprecedented by using conventional mononuclear Zn systems. This work not only establishes tri-Zn as a benchmark for sustainable, high-performance asymmetric catalysis but also underscores the transformative potential of multinuclear metal assemblies. Further detailed mechanistic investigations and applications of this tri-Zn system are underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1503200), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB0610000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92256303, 22171278), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (23ZR1482400), the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (2023J034) and Open Research Fund of School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan Normal University, the Research Funds of Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study, UCAS (2024HIAS-p003).

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.5c01067.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Breslow R.. Biomimetic Chemistry and Artificial Enzymes: Catalysis by Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995;28(3):146–153. doi: 10.1021/ar00051a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R., Dong S. D.. Biomimetic Reactions Catalyzed by Cyclodextrins and Their Derivatives. Chem. Rev. 1998;98(5):1997–2012. doi: 10.1021/cr970011j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S.. Asymmetric Organic Synthesis with Enzymes. Synthesis. 2009;2009:2650. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1216915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti L., Levine M.. Biomimetic Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2011;1(9):1090–1118. doi: 10.1021/cs200171u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Arnold F. H.. Engineering New Catalytic Activities in Enzymes. Nat. Catal. 2020;3(3):203–213. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0385-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Hessin C., Ren Y., Desage-El Murr M.. Biological Concepts for Catalysis and Reactivity: Empowering Bioinspiration. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49(23):8840–8867. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00914H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Snajdrova R., Moore J. C., Baldenius K., Bornscheuer U. T.. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic Synthesis for Industrial Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60(1):88–119. doi: 10.1002/anie.202006648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Xu K., Gao Z.-H., Zhu Z.-H., Ye C., Zhao B., Luo S., Ye S., Zhou Y.-G., Xu S., Zhu S.-F., Bao H., Sun W., Wang X., Ding K.. Biomimetic Asymmetric Catalysis. Sci. China Chem. 2023;66(6):1553–1633. doi: 10.1007/s11426-023-1578-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sträter N., Lipscomb W. N., Klabunde T., Krebs B.. Two-Metal Ion Catalysis in Enzymatic Acyl- and Phosphoryl-Transfer Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1996;35(18):2024–2055. doi: 10.1002/anie.199620241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands G. J.. Ambifunctional Cooperative Catalysts. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(10):1865–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00057-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki M., Yoshikawa N.. Lanthanide Complexes in Multifunctional Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2002;102(6):2187–2210. doi: 10.1021/cr010297z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.-A., Cahard D.. Towards Perfect Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis: Dual Activation of the Electrophile and the Nucleophile. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43(35):4566–4583. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Hong S.. Cooperative Bimetallic Catalysis in Asymmetric Transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41(21):6931–6943. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga S., Shibasaki M.. Recent Advances in Cooperative Bimetallic Asymmetric Catalysis: Dinuclear Schiff Base Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2014;50(9):1044–1057. doi: 10.1039/C3CC47587E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Beuken E. K., Feringa B. L.. Bimetallic Catalysis by Late Transition Metal Complexes. Tetrahedron. 1998;54(43):12985–13011. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00319-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bratko I., Gómez M.. Polymetallic Complexes Linked to a Single-Frame Ligand: Cooperative Effects in Catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2013;42(30):10664–10681. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50963j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankad N. P.. Selectivity Effects in Bimetallic Catalysis. Chem.Eur. J. 2016;22(17):5822–5829. doi: 10.1002/chem.201505002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley C. M., Uyeda C.. Organic Reactions Enabled by Catalytically Active Metal–Metal Bonds. Trends in Chem. 2019;1(5):497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda C., Farley C. M.. Dinickel Active Sites Supported by Redox-Active Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021;54:3710–3719. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos J.. Bimetallic Cooperation Across the Periodic Table. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020;4:696–702. doi: 10.1038/s41570-020-00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke C., Sperger T., Mendel M., Schoenebeck F.. Catalysis with Palladium(I) Dimers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60:3355–3366. doi: 10.1002/anie.202011825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E., Kikuta E.. Why Zinc in Zinc Enzymes? From Biological Roles to DNA Base-Selective Recognition. JBIC. 2000;5(2):139–155. doi: 10.1007/s007750050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning M. M., Kuo J. M., Raushel F. M., Holden H. M.. Three-Dimensional Structure of Phosphotriesterase: An Enzyme Capable of Detoxifying Organophosphate Nerve Agents. Biochem. 1994;33(50):15001–15007. doi: 10.1021/bi00254a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan T. S., Reid R. C.. Evolution in Action. Chem. Bio., 1995;2(2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning M. M., Shim H., Raushel F. M., Holden H. M.. High Resolution X-Ray Structures of Different Metal-Substituted Forms of Phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas Diminuta. Biochem. 2001;40(9):2712–2722. doi: 10.1021/bi002661e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M., Kuninaka A., Yoshino H.. Secondary Structure of Nuclease P1. Agric. Bio. Chem. 1975;39(11):2145–2148. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.39.2145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volbeda A., Lahm A., Sakiyama F., Suck D.. Crystal Structure of Penicillium Citrinum P1 Nuclease at 2.8 A Resolution. EMBO Journal. 1991;10(7):1607–1618. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romier C., Dominguez R., Lahm A., Dahl O., Suck D.. Recognition of single-stranded DNA by nuclease P1: high resolution crystal structures of complexes with substrate analogs. Proteins. 1998;32(4):414–424. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(19980901)32:4<414::AID-PROT2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R., Singh S.. Phosphate Ester Cleavage Catalyzed by Bifunctional Zinc Complexes: Comments on the “p-Nitrophenyl Ester Syndrome.”. Bioorg. Chem. 1988;16(4):408–417. doi: 10.1016/0045-2068(88)90026-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro M., Ishikubo A., Komiyama M.. Preparation and Study of Dinuclear Zinc(II) Complex for the Efficient Hydrolysis of the Phosphodiester Linkage in a Diribonucleotide. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995:1793–1794. doi: 10.1039/c39950001793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gultneh Y., Allwar, Ahvazi B., Blaise D., Butcher R. J., Jasinski J., Jasinski J.. Synthesis, Reactions and Structure of a Hydroxo-Bridged Dinuclear Zn(II) Complex: Modeling the Hydrolytic Zinc Enzymes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1996;241(2):31–38. doi: 10.1016/0020-1693(95)04791-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Matsunaga S., Shibasaki M.. Enantioselective 1,4-Addition of Unmodified Ketone Catalyzed by a Bimetallic Zn–Zn-Linked–BINOL Complex. Org. Lett. 2001;3(26):4251–4254. doi: 10.1021/ol016981h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano K., Nozaki K., Hiyama T.. Asymmetric Alternating Copolymerization of Cyclohexene Oxide and CO2 with Dimeric Zinc Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(18):5501–5510. doi: 10.1021/ja028666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer-Siebenlist B., Dechert S., Meyer F.. Biomimetic Hydrolysis of Penicillin G Catalyzed by Dinuclear Zinc(II) Complexes: Structure–Activity Correlations in β-Lactamase Model Systems. Chem.Eur. J. 2005;11(18):5343–5352. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. Y., Kwon H. Y., Lee S. Y., Na S. J., Han S., Yun H., Lee H., Park Y.-W.. Bimetallic Anilido-Aldimine Zinc Complexes for Epoxide/CO2 Copolymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(9):3031–3037. doi: 10.1021/ja0435135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarenmark M., Kappen S., Haukka M., Nordlander E.. Symmetrical and Unsymmetrical Dizinc Complexes as Models for the Active Sites of Hydrolytic Enzymes. Dalton Trans. 2008;8:993–996. doi: 10.1039/B713664A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli F., Bruno F., Mazzeo M., Lamberti M.. Zinc Complexes Bearing Dinucleating Bis(Imino- Pyridine)Binaphthol Ligands: Highly Active and Robust Catalysts for the Lactide Polymerization. ChemCatChem. 2023;15(13):e202300498. doi: 10.1002/cctc.202300498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molenveld P., Stikvoort W. M. G., Kooijman H., Spek A. L., Engbersen J. F. J., Reinhoudt D. N.. Dinuclear and Trinuclear Zn(II) Calix[4]Arene Complexes as Models for Hydrolytic Metallo-Enzymes. Synthesis and Catalytic Activity in Phosphate Diester Transesterification. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64(11):3896–3906. doi: 10.1021/jo982201f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Matsunaga S., Kinoshita T., Harada S., Okada S., Sakamoto S., Yamaguchi K., Shibasaki M.. Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Aldol Reaction of Hydroxyketones: Asymmetric Zn Catalysis with a Et2Zn/Linked-BINOL Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(8):2169–2178. doi: 10.1021/ja028926p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rit A., Zanardi A., Spaniol T. P., Maron L., Okuda J.. A Cationic Zinc Hydride Cluster Stabilized by an N-Heterocyclic Carbene: Synthesis, Reactivity, and Hydrosilylation Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53(48):13273–13277. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T., Sugiyama N., Masu H., Kado S., Yabe S., Yamanaka M.. A Trinuclear Zn3(OAc)4-3,3′-Bis(Aminoimino)Binaphthoxide Complex for Highly Efficient Catalytic Asymmetric Iodolactonization. Chem. Commun. 2014;50(61):8287–8290. doi: 10.1039/C4CC02415J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermert D. M., Ghiviriga I., Catalano V. J., Shearer J., Murray L. J.. An Air- and Water-Tolerant Zinc Hydride Cluster That Reacts Selectively With CO2 . Angew.Chem. Int.Ed. 2015;54:7047–7050. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaishi K., Nath B. D., Yamada Y., Kosugi H., Ema T.. Unexpected Macrocyclic Multinuclear Zinc and Nickel Complexes That Function as Multitasking Catalysts for CO2 Fixations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58(29):9984–9988. doi: 10.1002/anie.201904224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T., Horigane K., Suzuki T. K., Itoh R., Yamanaka M.. Catalytic Asymmetric Iodoesterification of Simple Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59(31):12680–12683. doi: 10.1002/anie.202003886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Suehisa G., Tadaoka H., Shiga K., Nozaki K.. Linear, Planar, Orbicular, and Macrocyclic Multinuclear Zinc (Meth)Acrylate Complexes. Chem.Eur. J. 2024;30(33):e202400586. doi: 10.1002/chem.202400586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Suehisa G., Mandai R., Nozaki K.. Sequence-Controlled Copolymerization of Structurally Well-Defined Multinuclear Zinc Acrylate Complexes and Styrene. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025;46(3):2400742. doi: 10.1002/marc.202400742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M., Ito H.. A Direct Catalytic Enantioselective Aldol Reaction via a Novel Catalyst Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122(48):12003–12004. doi: 10.1021/ja003033n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Wang Z., Ding K.. Copolymerization of Cyclohexene Oxide with CO2 by Using Intramolecular Dinuclear Zinc Catalysts. Chem.Eur. J. 2005;11:3668–3678. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M., Bartlett M. J.. ProPhenol-Catalyzed Asymmetric Additions by Spontaneously Assembled Dinuclear Main Group Metal Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48(3):688–701. doi: 10.1021/ar500374r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M., Hung C.-I., Mata G.. Dinuclear Metal-ProPhenol Catalysts: Development and Synthetic Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59(11):4240–4261. doi: 10.1002/anie.201909692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Huang Z.. Catalytic Reductive Desymmetrization of Malonic Esters. Nat. Chem. 2021;13(7):634–642. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki M., Matsunaga S.. Design and Application of Linked-BINOL Chiral Ligands in Bifunctional Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35(3):269–279. doi: 10.1039/b506346a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki M., Matsunaga S.. Metal/Linked-BINOL Complexes: Applications in Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Mannich-Type Reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691(10):2089–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga S., Shibasaki M.. Multimetallic Bifunctional Asymmetric Catalysis Based on Proximity Effect Control. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2008;81(1):60–75. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.81.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Matsunaga S., Shibasaki M.. Enantioselective 1,4-Addition of Unmodified Ketone Catalyzed by a Bimetallic Zn–Zn-Linked–BINOL Complex. Org. Lett. 2001;3(26):4251–4254. doi: 10.1021/ol016981h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Matsunaga S., Kinoshita T., Harada S., Okada S., Sakamoto S., Yamaguchi K., Shibasaki M.. Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Aldol Reaction of Hydroxyketones: Asymmetric Zn Catalysis with a Et2Zn/Linked-BINOL Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(8):2169–2178. doi: 10.1021/ja028926p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Yekta S., Yudin A. K.. Modified BINOL Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2003;103(8):3155–3212. doi: 10.1021/cr020025b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunel J. M.. BINOL: A Versatile Chiral Reagent. Chem. Rev. 2005;105(3):857–898. doi: 10.1021/cr040079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Liu Q., Gong L., Cui X., Mi A., Jiang Y.. Novel Achiral Biphenol-Derived Diastereomeric Oxovanadium(IV) Complexes for Highly Enantioselective Oxidative Coupling of 2-Naphthols. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:4532–4535. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4532::AID-ANIE4532>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q.-S., Lu Y.-N., Liu B., Xiao J., Li J.-S.. A Facile Synthesis of 3 or 3,3′-Substituted Binaphthols and Their Applications in the Asymmetric Addition of Diethylzinc to Aldehydes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691(6):1282–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Jin R.-Z., Lü G.-H., Bian Z., Ding M.-X., Gao L.-X.. Synthesis and Applications of 3-[6-(Hydroxymethyl)Pyridin-2-Yl]-1,1′-Bi-2-Naphthols or 3,3′-Bis[6-(Hydroxymethyl)Pyridin-2-Yl]-1,1′-Bi-2-Naphthols. Synthesis. 2007;2007(16):2461–2470. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-983787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn R. R., Hussain S. M. S., Prien O., Ahmed Z., Snieckus V.. 3,3‘-Dipyridyl BINOL Ligands. Synthesis and Application in Enantioselective Addition of Et2Zn to Aldehydes. Org. Lett. 2007;9(22):4403–4406. doi: 10.1021/ol071276f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X.-W., Zheng L.-F., Wu L.-L., Zong L.-L., Cheng Y.-X.. Bifunctional Enantioselective Ligands of Chiral BINOL Derivatives for Asymmetric Addition of Alkynylzinc to Aldehydes. Chin. J. Chem. 2008;26(2):373–378. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.200890072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abell J. P., Yamamoto H.. Dual-Activation Asymmetric Strecker Reaction of Aldimines and Ketimines Catalyzed by a Tethered Bis(8-Quinolinolato) Aluminum Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131(42):15118–15119. doi: 10.1021/ja907268g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akine S., Shimada T., Nagumo H., Nabeshima T.. Highly cooperative double metalation of a bis(N2O2) ligand based on bipyridine-phenol framework driven by intramolecular pi-stacking of square planar nickel(II) complex moieties. Dalton Trans. 2011;40(34):8507–8509. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10124b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Jin R., Bian Z., Kang C., Chen Y., Xu J., Gao L.. Donor-Induced Helical Inversion of 1,1′-Binaphthyl Connecting with Two Molybdenum Complexes. Chem.Eur. J. 2012;18(41):13168–13172. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akine S., Nagumo H., Nabeshima T.. Hierarchical Helix of Helix in the Crystal: Formation of Variable-Pitch Helical π-Stacked Array of Single-Helical Dinuclear Metal Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51(10):5506–5508. doi: 10.1021/ic3004273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K., Ogawa M., Shibata T.. Multinuclear Catalyst for Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Conjugate Addition of Organozinc Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:2410–2413. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra S., Akakura M., Yamamoto H.. Design of a New Bimetallic Catalyst for Asymmetric Epoxidation and Sulfoxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(50):15612–15615. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T., Sato K., Nakamura A., Makino H., Masu H.. Dinuclear PhosphoiminoBINOL-Pd Container for Malononitrile: Catalytic Asymmetric Double Mannich Reaction for Chiral 1,3-Diamine Synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y.-Q., Zhang D., Ronson T. K., Tarzia A., Lu Z., Jelfs K. E., Nitschke J. R.. Sterics and Hydrogen Bonding Control Stereochemistry and Self-Sorting in BINOL-Based Assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(24):9009–9015. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c05172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino E., Nakamura A., Kuwano S., Arai T.. Chiral C2-Symmetric Aminomethylbinaphthol as Synergistic Catalyst for Asymmetric Epoxidation of Alkylidenemalononitriles: Easy Access to Chiral Spirooxindoles. Org. Lett. 2021;23(6):1980–1985. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus H. A., Guiry P. J.. Recent Developments in the Application of Oxazoline-Containing Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2004;104(9):4151–4202. doi: 10.1021/cr040642v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Zhang W.. Renaissance of Pyridine-Oxazolines as Chiral Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47(5):1783–1810. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00615B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong C. C., Kinjo R.. Catalytic Hydroboration of Carbonyl Derivatives, Imines, and Carbon Dioxide. ACS Catal. 2015;5(6):3238–3259. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b00428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J.-H., Bao D.-H., Zhou Q.-L.. Recent Advances in the Development of Chiral Metal Catalysts for the Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Ketones. Synthesis. 2015;47(04):460–471. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shegavi M. L., Bose S. K.. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Hydroboration of Carbonyl Compounds. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019;9(13):3307–3336. doi: 10.1039/C9CY00807A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Park S.. Recent Advances in Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydroboration of Ketones. ChemCatChem. 2021;13(8):1898–1919. doi: 10.1002/cctc.202001947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geier S. J., Vogels C. M., Melanson J. A., Westcott S. A.. The Transition Metal-Catalysed Hydroboration Reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51(21):8877–8922. doi: 10.1039/D2CS00344A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenbo, L. ; Zhan, L. . 7.16 - Reduction: Hydroboration of CO and CN. In Comprehensive Chirality, 2nd ed.; Cossy, J. , Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2024; pp 484–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini M., Cozzi P. G., de Angelis M., Umani-Ronchi A.. Zinc Triflate–Bis-Oxazoline Complexes as Chiral Catalysts: Enantioselective Reduction of α-Alkoxy-Ketones with Catecholborane. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41(10):1601–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)02339-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roh S.-G., Park Y.-C., Park D.-K., Kim T.-J., Jeong J. H.. Synthesis and Characterization of a Zn(II) Complex of a Pyrazole-Based Ligand Bearing a Chiral l-Alaninemethylester. Polyhedron. 2001;20(15):1961–1965. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(01)00788-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roh S. G., Yoon J. U., Jeong J. H.. Synthesis and Characterization of a Chiral Zn(II) Complex Based on a Trans-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane Derivative and Catalytic Reduction of Acetophenone. Polyhedron. 2004;23(12):2063–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2004.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli M., Cozzi P. G.. Effective Modular Iminooxazoline (IMOX) Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis: [Zn(IMOX)]-Promoted Enantioselective Reduction of Ketones by Catecholborane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42(40):4928–4930. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.-F., Neumann H.. Zinc-Catalyzed Organic Synthesis: C-C, C-N, C-O Bond Formation Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354(17):3141–3160. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201200547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enthaler S.. Rise of the Zinc Age in Homogeneous Catalysis? ACS Catal. 2013;3(2):150–158. doi: 10.1021/cs300685q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łowicki D., Baś S., Mlynarski J.. Chiral Zinc Catalysts for Asymmetric Synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2015;71(9):1339–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2014.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pellissier H.. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Zinc-Catalyzed Transformations. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2021;439:213926. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghouse S., Sreenivasulu C., Kishore D. R., Satyanarayana G.. Recent Developments by Zinc Based Reagents/Catalysts Promoted Organic Transformations. Tetrahedron. 2022;105:132580. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2021.132580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brands K. M. J., Payack J. F., Rosen J. D., Nelson T. D., Candelario A., Huffman M. A., Zhao M. M., Li J., Craig B., Song Z. J., Tschaen D. M., Hansen K., Devine P. N., Pye P. J., Rossen K., Dormer P. G., Reamer R. A., Welch C. J., Mathre D. J., Tsou N. N., McNamara J. M., Reider P. J.. Efficient Synthesis of NK1 Receptor Antagonist Aprepitant Using a Crystallization-Induced Diastereoselective Transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(8):2129–2135. doi: 10.1021/ja027458g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christmann U., Garriga L., Llorente A. V., Díaz J. L., Pascual R., Bordas M., Dordal A., Porras M., Yeste S., Reinoso R. F., Vela J. M., Almansa C.. WLB-87848, a Selective ∑1 Receptor Agonist, with an Unusually Positioned NH Group as Positive Ionizable Moiety and Showing Neuroprotective Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2024;67(11):9150–9164. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J., Reichard G. A.. Enantioselective and Practical Syntheses of R- and S-Fluoxetines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30(39):5207–5210. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)93743-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K. ; Edmonds, D. J. ; Kalgutkar, A. ; Ebner, D. ; Thuma, B. ; Filipski, K. J. ; Kumar, R. . Indole and indazole compounds that activate AMPK. Intl. Patent WO2016092413, 2016.

- Kumar G. S., Harinath A., Narvariya R., Panda T. K.. Homoleptic Zinc-Catalyzed Hydroboration of Aldehydes and Ketones in the Presence of HBpin. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020;2020(5):467–474. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201901276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Rawal P., Banerjee I., Pada Nayek H., Gupta P., Panda T. K.. Catalytic Hydroboration and Reductive Amination of Carbonyl Compounds by HBpin Using a Zinc Promoter. Chem.Asian J. 2022;17(5):e202200013. doi: 10.1002/asia.202200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo R. K., Mahato M., Jana A., Nembenna S.. Zinc Hydride-Catalyzed Hydrofuntionalization of Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85(17):11200–11210. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataie S., Hogeterp S., Ovens J. S., Baker R. T.. SNS Ligand-Assisted Catalyst Activation in Zn-Catalysed Carbonyl Hydroboration. Chem. Commun. 2022;58(23):3795–3798. doi: 10.1039/D1CC06981K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlian D. G., Amemiya E., Parkin G.. Synthesis of Bis(2-Pyridylthio)Methyl Zinc Hydride and Catalytic Hydrosilylation and Hydroboration of CO2 . Chem. Commun. 2022;58(26):4188–4191. doi: 10.1039/D1CC06963B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., Singh T., Baguli S., Ghosh S., Mukherjee D.. A N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Supported Zinc Catalyst for the 1,2-Regioselective Hydroboration of N-Heteroarenes. Chem.Eur. J. 2023;29(38):e202300508. doi: 10.1002/chem.202300508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Krämer T., Barnes L. G., Hawker R. R., Singh K., Kilpatrick A. F. R.. Organozinc β-Thioketiminate Complexes and Their Application in Ketone Hydroboration Catalysis. Organometallics. 2025;44(6):749–759. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.4c00513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand A.-K., Rit A., Okuda J.. Molecular Zinc Hydrides. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2016;314:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rombach M., Brombacher H., Vahrenkamp H.. The Insertion of Heterocumulenes into Zn–H and Zn–OH Bonds of Pyrazolylborate–Zinc Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002;2002(1):153–159. doi: 10.1002/1099-0682(20021)2002:1<153::AID-EJIC153>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang Y., Yuan D., Yao Y.. Regioselective Hydroboration and Hydrosilylation of N-Heteroarenes Catalyzed by a Zinc Alkyl Complex. Org. Lett. 2020;22(14):5695–5700. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C., Yu H., Liu L., Yan B., Zhang B., Ma X., Zhang X., Yang Z.. An Efficient Catalytic Method for the Borohydride Reaction of Esters Using Diethylzinc as Precatalyst. New J. Chem. 2022;46(30):14635–14641. doi: 10.1039/D2NJ03136A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B., Qin Z., Miao H., Wang C., Huang M., Liu C., Bai C., Chen Z.. Alkyl Zinc Complexes Derived from Formylfluorenimide Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Catalysis for Hydroboration of Aldehydes and Ketones. Dalton Trans. 2025;54(8):3427–3436. doi: 10.1039/D4DT03395G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana T., Abraham S., Kagan H. B.. Nonlinear Effects in Asymmetric Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48(3):456–494. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan H. B.. Practical Consequences of Non-Linear Effects in Asymmetric Synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2001;343(3):227–233. doi: 10.1002/1615-4169(20010330)343:3<227::AID-ADSC227>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Li Y., Bao H.. Mechanistic Applications of Nonlinear Effects in First-Row Transition-Metal Catalytic Systems. Chin. J. Chem. 2023;41(22):3097–3114. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.202300056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y.-Z., Han X.-W., Yang X.-C., Song X., Wang M.-C., Chang J.-B.. Enantioselective Friedel–Crafts Alkylation of Pyrrole with Chalcones Catalyzed by a Dinuclear Zinc Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79(23):11690–11699. doi: 10.1021/jo5023712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi Y., Yoshikai N.. Enantioselective Conjugate Addition of Catalytically Generated Zinc Homoenolate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(12):4775–4781. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c00869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.