Abstract

Dolutegravir is a preferred antiretroviral drug given its high resistance barrier and efficacy; however, reports from sub-Saharan Africa indicate increased hyperglycemia rates among individuals living with HIV on dolutegravir. Potential mechanisms include mitochondrial dysfunction from previous exposure to NRTIs like stavudine and zidovudine, which causes mitochondrial toxicity and predisposes patients to hyperglycemia upon switching to dolutegravir; magnesium chelation, which is borrowed from dolutegravir’s mode of action (dolutegravir inhibits the action of integrase by chelation of magnesium required as a cofactor by the HIV enzyme); and chronic inflammation, with elevated pro-inflammatory markers like IL-6, CRP, and TNF-α contributing to insulin resistance. The narrative review highlights variability in hyperglycemia among patients, influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and prior antiretroviral therapy. The exact nature of dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia, whether due to insulin resistance or reduced insulin release, remains unclear, although insulin resistance is significant.

Keywords: Dolutegravir, Hyperglycemia, Type-2 diabetes, Africa, HIV

Introduction

Dolutegravir (DTG) is a potent drug from the integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) class of antiretroviral agents. It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2013 [1]. The drug is known for its high potency and effectiveness. It also has a higher genetic barrier to HIV resistance compared to other antiretrovirals [2]. DTG is a better substitute for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs). This is especially important because NNRTIs have long faced high levels of viral resistance. Because of these advantages, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended dolutegravir for first-line HIV treatment in 2016 [3].

This recommendation led to the national roll-out of dolutegravir in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [4]. It is commonly used in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and lamivudine, forming the TLD regimen [1]. In Uganda, resistance to NNRTIs had exceeded the WHO threshold of 10% [2]. As a result, many patients who had been on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for over a decade were switched to TLD [5].

Surprisingly, signs of DTG-associated hyperglycemia began to emerge from urban HIV treatment centres. These were the sites that led the national rollout of DTG-based regimens. In Uganda, Lamorde and colleagues reported a significantly higher rate of new-onset symptomatic hyperglycemia among people on DTG compared to those on efavirenz. The incidence was 0.47% for DTG and 0.03% for efavirenz (p = 0.0004) [6].

Namara et al. (2022) in Uganda also reported a higher risk of hyperglycemia in people taking DTG. Compared to those on non-DTG regimens, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 7.01 (95% CI 1.96–25.09). In this study, hyperglycemia was defined as fasting blood glucose (FBS) ≥ 100 mg/dL or a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥ 140 mg/dL [7].

A longitudinal study from Ghana followed ART-naïve and ART-experienced individuals on DTG for at least 72 weeks [8]. All participants had normal blood glucose levels at baseline. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was defined as FBS ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL). The study found a T2DM incidence proportion of 11.8% (95% CI 10.2–13.7). The incidence rate was 98.1 cases per 1000 person-years (PY). The median time to diabetes diagnosis was 24 weeks after starting DTG. ART-experienced individuals had a higher incidence (12.6%) and rate (101.4 per 1000 PY) than ART-naïve participants (6.5% and 68 per 1000 PY). This suggests that previous ART exposure may increase the risk.

In Uganda, Ankunda et al. (2024) [9] conducted a similar prospective study. They used random blood glucose (RBS) to define hyperglycemia (RBS ≥ 7 mmol/L). Participants with high RBS underwent confirmatory HbA1c testing. Diabetes was diagnosed at HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. Over six months, the incidence rate of hyperglycemia was 245 cases (95% CI: 19.3–31.1) per 1000 PY. The incidence of diabetes was 58 cases (95% CI: 3.6–9.3) per 1000 PY. These rates were higher than those reported in the Ghanaian study. The difference may be due to the diagnostic approach. RBS can detect temporary rises in glucose more easily than FBS. It may also reflect different population-level metabolic risks.

The mechanisms behind dolutegravir-related hyperglycemia remain unclear. In this narrative review, we examine potential pathophysiologic explanations linking dolutegravir to hyperglycemia. One possible mechanism is prior mitochondrial dysfunction, as most reported cases occur in ART-experienced individuals. Prior exposure to NRTIs is known to cause mitochondrial toxicity in virally suppressed patients living with HIV. Dolutegravir may also contribute to dose-dependent magnesium chelation. Additionally, pre-existing low-grade chronic inflammation may play a role.

Methods

Our initial search for possible mechanisms of dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia revealed limited existing literature, justifying a narrative review instead of a systematic review. We searched for literature in PubMed and Google Scholar using the following search strings:

(“Dolutegravir” OR “DTG”) AND (“Hyperglycemia” OR “Insulin resistance” OR “Glucose intolerance”) AND (“Mechanism” OR “Pathophysiology”).

(“Dolutegravir” OR “INSTI”) AND (“Hyperglycemia” OR “Diabetes”) AND (“Mitochondrial dysfunction” OR “Oxidative stress”).

(“Dolutegravir” OR “HIV integrase inhibitor”) AND (“Insulin resistance” OR “Beta-cell dysfunction”) AND (“Pancreatic function” OR “Glucose metabolism”).

(“Dolutegravir“[MeSH] OR “Integrase Inhibitors“[MeSH]) AND (“Hyperglycemia“[MeSH] OR “Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2“[MeSH]) AND (“Mitochondria“[MeSH] OR “Insulin Resistance“[MeSH])

Based on the results of our initial search, we conducted further literature searches to obtain more detailed explanations of the possible mechanisms.

The mode of action of dolutegravir

Dolutegravir (DTG) is an INSTI widely used in the management of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection [10]. It functions by blocking the viral integrase enzyme, thereby preventing the integration of HIV DNA into the host genome, a critical step in the viral replication cycle. This inhibition effectively disrupts HIV propagation, leading to viral load suppression and immune system recovery in individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Dolutegravir exerts its antiviral activity by selectively binding to the active site of HIV-1 integrase, specifically interacting with essential divalent metal ions (Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺) required for enzymatic activity [10]. This interaction prevents the formation of a stable pre-integration complex, thereby blocking the strand transfer step of DNA integration. By halting this process, dolutegravir prevents the covalent attachment of viral DNA to the host genome, effectively inhibiting viral replication.

Insulin release and action

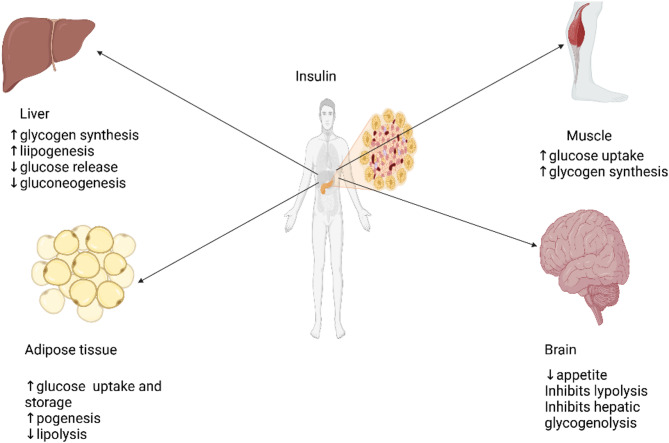

Insulin, one of the key hormones regulating glucose metabolism, is secreted by the beta cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Target organs for insulin

At a molecular level, glucose enters pancreatic beta cells via GLUT2 transporters (Fig. 2). Intracellular glucose is metabolized through glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, leading to an increase in ATP production [11, 12]. Insulin is released upon the influx of calcium through the calcium channels, which is triggered by the closure of the ATP-dependent potassium channels [13, 14, 15]. ATP binds with magnesium ions (Mg2+) to create its biologically active form, and a significant portion of intracellular ATP and Mg2+ is thought to exist as Mg-ATP complexes. Since both ATP and Mg2+ are tightly regulated and buffered within the cytosol, Mg2+ plays a crucial role in energy metabolism [16]. Additionally, magnesium is required as a cofactor for many enzymes involved in glycolysis and the Krebs cycle [17]. Therefore, the chelation of magnesium by dolutegravir may reduce the cell’s ability to efficiently produce ATP, which is crucial for insulin release. Additionally, the majority of ATP is generated in the mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction, which can result from exposure to drugs that are toxic to mitochondria, impairs ATP production and, consequently, insulin release [18].

Fig. 2.

Insulin release. Insulin release depends on ATP produced through glycolysis and the Krebs cycle. Dolutegravir chelates the magnesium that is required for ATP stabilization and also serve as a cofactor for numerous metabolic enzymes. The presence of mitochondrial dysfunction due to prior exposure to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) in some individuals may exacerbate the metabolic effects of dolutegravir. GLUT2 glucose transporter 2, ADP adenosine diphosphate, ATP adenosine triphosphate, DTG dolutegravir, Mg2+ magnesium ions, K+ potassium ions, Ca2+ calcium ions, ROS reactive oxygen species

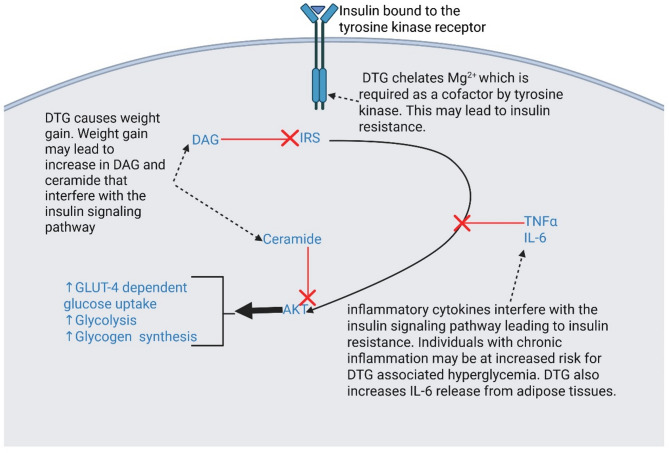

Insulin binds to the extracellular alpha subunits of the insulin receptor (IR), a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor (Fig. 3). This binding induces a series of reactions within the cell [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The final product, protein kinase B (AKT), triggers increased GLUT-4-dependent glucose uptake, glycolysis, and glycogen synthesis. Several inhibitors of the insulin signalling pathway have been identified, including ceramide, diacylglycerol (DAG), and inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). Ceramide and DAG are by-products of inefficient fat metabolism, commonly seen in obese individuals or those experiencing weight gain, as well as in individuals with mitochondrial dysfunction. DAG inhibits the insulin receptor substrate (IRS), which initiates the signalling pathway, while ceramide blocks the final step of the pathway. Evidence suggests that dolutegravir is linked to weight gain, which may, in turn, lead to increased levels of DAG and ceramide. Additionally, dolutegravir has been associated with mitochondrial toxicity in preclinical studies [25]. Inflammatory cytokines TNF-α [26] and IL-6 [27, 28] are also known to disrupt insulin signalling, which contributes to insulin resistance. Many cases of dolutegravir-induced hyperglycemia are observed in patients with metabolic syndrome [6], a condition closely tied to inflammation [29]. Metabolic syndrome refers to a group of interconnected conditions, such as elevated blood pressure, high blood sugar levels, excessive abdominal fat, elevated triglycerides, and reduced HDL cholesterol, which collectively raise the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes [29, 30]. Therefore, it is plausible that individuals with chronic inflammation may have an increased risk of developing hyperglycemia when treated with dolutegravir. Furthermore, dolutegravir may inhibit the tyrosine kinase by chelation of magnesium, which it requires as a cofactor.

Fig. 3.

Insulin action. Insulin binds to tyrosine kinase receptors on target tissues, initiating a series of reactions downstream termed as insulin signalling. The signalling results in glucose uptake, among other effects. Interfering with this pathway causes insulin resistance. Abbreviations: GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; DAG, diacylglycerol; DTG, dolutegravir; Mg2+, magnesium ions; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor ; IL-6, interleukin 6; AKT, protein kinase B

Dolutegravir-induced mitochondrial dysfunction relates to beta-cell dysfunction

Dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia is more frequent among ART-experienced individuals [6, 31, 32, 33]. Prolonged exposure to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, particularly stavudine and zidovudine, may result in mitochondrial toxicity [34]. Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to beta-cell dysfunction [18] and insulin resistance [35].

In mice, dolutegravir causes mitochondrial damage by decreasing the mitochondrial complex IV component and reducing mitochondrial respiratory capacity, although clinical relevance in humans remains uncertain [25]. Reduced mitochondrial respiratory capacity leads to reactive oxygen species that may destroy the mitochondrial genome and cause inflammation. Dolutegravir was observed to cause a significant reduction in mitochondrial maximal and spare respiratory capacities in macrophages [36]. In a study by Gorwood et al., dolutegravir treatment led to increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in adipose stem cells and adipocytes and was found to induce insulin resistance in adipocytes [37]. According to Mohan et al. (2023), the combined use of antiretrovirals, including TLD, was linked to mitochondrial stress and dysfunction. Notably, the study observed that oxidative damage and reduced ATP production persisted despite the activation of antioxidant responses and mitochondrial maintenance systems with TLD treatment [38]. There was a significant suppression in mitochondrial stress responses with a decrease in Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) and uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) protein expression, contributing to the observed effects [38]. SIRT3, a primary deacetylase in mitochondria, is responsible for regulating nearly all aspects of mitochondrial health and function. It manages critical processes like energy homeostasis, redox balance, mitochondrial quality, biogenesis, dynamics, and mitophagy [39]. On the other hand, UCP2 plays a role in the immune response, managing oxidative stress, and maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential, along with supporting energy production [40].

Dolutegravir inhibits glucokinase via magnesium ion chelation

Dolutegravir inhibits HIV integrase by chelating magnesium at the enzyme’s catalytic core site [41]. It is hypothesized that using the same mechanism, dolutegravir chelates magnesium required as a cofactor by glucokinase, an enzyme involved in glucose metabolism. No study has compared either plasma or intracellular magnesium levels between individuals on dolutegravir with or without hyperglycemia. However, a study has demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in dolutegravir plasma exposure when dolutegravir is co-administered with divalent ion-containing drugs [42].

Dolutegravir modulates chronic low-grade inflammation in specific tissues

Pro-inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and TNF-α are associated with metabolic syndrome. In a study of Lamorde and colleagues [6], 50% of individuals with dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia had hypertension, one of the components of metabolic syndrome. This is consistent with the case reports [31, 32, 33] that have cited that most individuals with dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, which is possibly caused by low-grade chronic inflammation [43]. These markers cause insulin resistance by interfering with insulin signalling. In preclinical models, dolutegravir has been proven to increase the expression and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines while reducing the secretion of counter-inflammatory hormones from adipocytes [44]. Specifically, dolutegravir stimulates the release of IL-6 but inhibits the expression and release of adiponectin and leptin from the adipose tissues [37, 44]. Dolutegravir increased the gene expression of IL-6, a marker of inflammation, and elevated IL-6 in the culture medium. According to Theron et al. (2022) dolutegravir may enhance the release of elastase, an enzyme involved in inflammation, in a dose-dependent manner in neutrophils [45].

An opposite effect of dolutegravir was observed in human coronary endothelial cells [46], suggesting that the pro-inflammatory effect of dolutegravir could be tissue-specific. In the human coronary endothelial cells, dolutegravir decreased inflammation by reducing NF-κB activation and secretion of pro-inflammatory markers like IL-6, IL-8, sICAM-1, and sVCAM-1. Moreover, dolutegravir improved insulin sensitivity and reduced cellular senescence. These favourable effects of dolutegravir on inflammation and senescence were partially mediated by the involvement of ubiquitin-specific peptidase-18. However, the drug’s positive influence on insulin sensitivity occurred independently of USP18, indicating that dolutegravir engages multiple pathways to exert its effects on coronary endothelial cells [46].

Indeed, some in vivo human studies have reported dolutegravir to have overall anti-inflammatory effects [47]. So far, no study has investigated the inflammatory effects of dolutegravir on the liver and skeletal muscle tissues, whose insulin resistance may lead to type 2 diabetes.

Clinical heterogeneity in dolutegravir effect on hyperglycaemia

Mitochondrial deletions increase with age; however, age does not increase risk for hyperglycemia, suggesting that there are multiple potential mechanisms at play. One plausible explanation is the extent of exposure to dolutegravir. There is currently no human study that has reported the relationship between dolutegravir dose and hyperglycemia. Preclinical evidence from limited studies has demonstrated that dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia is dose-dependent. Jung et al. (202) demonstrated that varying doses of dolutegravir modulated lipid accumulation and suppressed thermogenesis-related proteins such as uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1 in adipocytes [25]. UCP1 is primarily found in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and plays a key role in thermogenesis by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation from ATP production. This process generates heat instead of ATP, which helps in maintaining body temperature and energy expenditure.

Increased activation of UCP1 in brown adipose tissue is associated with increased energy expenditure and can potentially affect glucose metabolism [48, 49]. It was observed that higher doses of dolutegravir led to a more significant reduction in the expression of UCP1, indicating a dose-dependent relationship. The study also noted dose-dependent effects on the attenuation of lipolysis, as shown by reductions in glycerol release and perilipin 1 levels [25]. Perilipin is a protein that coats lipid droplets in adipocytes and plays a role in lipid metabolism and storage. It regulates lipolysis, the breakdown of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, which are released into the blood stream. Dysregulation of perilipin can affect lipid metabolism and potentially influence insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism [50, 51]. Patients with a range of dolutegravir concentrations are needed to gather data on dolutegravir’s impact on adipocyte metabolism and proteins that regulate thermogenesis. In another relatively similar study on human fat cells, the expression of genes associated with fat cell function, inflammation, mitochondrial function, and adipokines was modulated by dolutegravir in a concentration-dependent manner [44].

Taken together, these in vitro and preclinical studies suggest that higher concentrations of dolutegravir may affect the cellular processes involved in fat cell function and inflammation in a dose-dependent manner.

Griesel et al. (2022) found that while the estimated area under the concentration-time curve for dolutegravir was not associated with a change in overall weight, it was negatively associated with changes in visceral adipose tissue mass. This suggests that dolutegravir concentrations may not be directly related to overall weight gain but might be linked to changes in the distribution of adipose tissue, specifically a decrease in visceral fat [52].

Dolutegravir exposure may also vary according to the genetic background of the individual. Dolutegravir is primarily metabolized by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 and cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and is a substrate for both ABCB1 and ABCG2, expressed in the intestine and known as efflux transporters of drugs. Additionally, it is a substrate for the nuclear receptor subfamily 1 gene (NR1I2). Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group I, member 2 (NR1I2), also known as the pregnane X receptor (PXR), is a ligand-activated transcription factor belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily. NR1I2 plays a crucial role in regulating the expression of genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism [53, 54] and is involved in regulating lipid and cholesterol metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and inflammation [55].

UGT1A1*6 and/or UGT1A1*28 were demonstrated to be factors associated with high dolutegravir trough concentrations [56]. In a study by Elliot et al. (2020), different genetic variations were found to be associated with significant increases in drug exposure. For instance, the combination of certain UGT1 and NR1I2 variants was linked to a 79% increase in drug exposure, while combined ABCG2 and NR1I2 variants were associated with a 43% increase in maximum drug concentration and a 39% increase in overall drug exposure. Additionally, specific UGT1A1 variants were individually linked to increased drug exposure, with UGT1A1*28 poor metabolizer status associated with a 27% increase in drug exposure, and the combination of UGT1A1*28 poor metabolizer and UGT1A1*6 intermediate metabolizer statuses correlated with a 43% increase in drug exposure. In another study, the mean peak plasma concentration of dolutegravir was significantly higher in the genotypes of ABCG2 421 AA compared with the genotypes of ABCG2 421 CC [57].

The role of mitochondrial genome variations in the progression of dolutegravir-associated severe hyperglycemia: associations with mutations, heteroplasmy, and genetic predisposition

Prior deletions in the mitochondrial genome may also explain individual progression to diabetes. Research into the relationship between mitochondrial genome variations and type 2 diabetes (T2D) has uncovered several significant associations. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in genes such as MT-ND4, MT-ND5, and MT-CO1, which encode essential subunits of the electron transport chain, are known to impair mitochondrial function and contribute to insulin resistance [58, 59]. Heteroplasmy, the presence of both mutated and wild-type mtDNA within cells, further complicates this relationship. High levels of heteroplasmy, particularly involving genes like MT-ND4 and MT-TL1, have been associated with more severe mitochondrial dysfunction and a worsened progression of T2D [60]. Additionally, certain mitochondrial haplogroups, such as JT, have been linked to an increased risk of T2D in diverse populations, suggesting a genetic predisposition [61, 62].

The nature of dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia: insights into insulin resistance, C-peptide, and Ketosis-Prone diabetes

It is unclear whether dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia is due to reduced insulin release or resistance. One case report recorded normal C-peptide, implying that dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia could be due to insulin resistance [63]. During post-translational processing, proinsulin is cleaved into insulin and C-peptide. Insulin is then released into the bloodstream to regulate glucose levels, while C-peptide is also secreted in equimolar amounts. C-peptide levels are often used clinically as an indicator of endogenous insulin secretion. Elevated C-peptide levels may indicate increased insulin production and secretion in response to elevated blood glucose levels. In the context of dolutegravir use and potential effects on glucose metabolism, monitoring C-peptide levels alongside glucose levels can provide insights into insulin secretion and pancreatic function [64].

Dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia appears to have some similarities with ketosis-prone diabetes (KPD). KPD is a unique form of diabetes that presents with characteristics of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [65, 66]. It primarily affects individuals of African origin and is marked by an acute onset of severe hyperglycemia and ketosis or ketoacidosis, resembling type 1 diabetes at first but showing insulin independence over time, more akin to type 2 diabetes. Similar to dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia, most individuals (74%) experience weight loss at diagnosis [67].

Conclusions

Dolutegravir may cause hyperglycemia in a dose-dependent manner, with the effect potentially more pronounced in individuals with supra-therapeutic plasma levels. In addition to possible magnesium chelation, individuals with underlying mitochondrial dysfunction or deletions might experience reduced metabolic efficiency. This could lead to the accumulation of metabolic by-products that interfere with insulin signalling and contribute to insulin resistance. Studies on humans and more preclinical data are needed to determine whether dolutegravir is due to failure of insulin release or insulin resistance.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

BA and YM-conceptualization, JS-literature search, all the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW009771. B.A, B.C, and D.O. are partly supported by Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (Award #D43TW009771 “HIV and co-infections in Uganda”). Supported in part (SJR) by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dow DE, Bartlett JA. Dolutegravir, the second-generation of integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) for the treatment of HIV. Infect Dis Therapy. 2014;3:83–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watera C, et al. HIV drug resistance among adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(9):2407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH. Transition to new antiretroviral drugs in HIV programmes: clinical and programmatic considerations, in Transition to new antiretroviral drugs in HIV programmes: clinical and programmatic considerations. 2017.

- 4.Adoption WHP. Implementation status in countries. World Health Organization; 2019.

- 5.Nakkazi E. Changes to dolutegravir policy in several African countries. Lancet. 2018;392(10143):199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamorde M, et al. Dolutegravir-associated hyperglycaemia in patients with HIV. The lancet. HIV. 2020;7(7):e461–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namara D, et al. The risk of hyperglycemia associated with use of dolutegravir among adults living with HIV in kampala, uganda: A case-control study. Int J STD AIDS. 2022;33(14):1158–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lartey M, et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in persons living with HIV initiated on dolutegravir-based antiretroviral regimen in ghana: an observational longitudinal study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43(1):199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ankunda C, et al. Evaluating the glycemic effects of dolutegravir and its predictors among people with human immunodeficiency virus in uganda: A prospective cohort study. Open forum infectious diseases. Oxford University (Vol. 11, No. 10, p. ofae596); Press US; 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Ribera E, Podzamczer D. Mechanisms of action, Pharmacology and interactions of dolutegravir]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015;33(Suppl 1):2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rorsman P, Braun M, Zhang Q. Regulation of calcium in pancreatic α-and β-cells in health and disease. Cell Calcium. 2012;51(3–4):300–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henquin J-C. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia. 2009;52(5):739–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. KATP channels and islet hormone secretion: new insights and controversies. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2013;9(11):660–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilar-Bryan L, et al. Cloning of the β cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268(5209):423–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rorsman P, Renström E. Insulin granule dynamics in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1029–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamanaka R, et al. Mitochondrial Mg2 + homeostasis decides cellular energy metabolism and vulnerability to stress. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):30027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(Suppl 1):i3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maechler P et al. Role of mitochondria in β-cell function and dysfunction. Islets Langerhans, 2010 15:pp. 193–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Pessin JE, Saltiel AR. Signalling pathways in insulin action: molecular targets of insulin resistance. J Clin Investig. 2000;106(2):165–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White MF. Insulin signalling in health and disease. Science. 2003;302(5651):1710–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers MG Jr, White MF. The new elements of insulin signalling: insulin receptor substrate-1 and proteins with SH2 domains. Diabetes. 1993;42(5):643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White MF. IRS proteins and the common path to diabetes. Am J Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 2002;283(3):E413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanhaesebroeck B, Alessi DR. The PI3K–PDK1 connection: more than just a road to PKB. Biochem J. 2000;346(3):561–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manning BD, Toker A. AKT/PKB signalling: navigating the network. Cell. 2017;169(3):381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung I, et al. Dolutegravir suppresses thermogenesis via disrupting uncoupling protein 1 expression and mitochondrial function in brown/beige adipocytes in preclinical models. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(9):1626–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krogh-Madsen R, et al. Influence of TNF-alpha and IL-6 infusions on insulin sensitivity and expression of IL-18 in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(1):E108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(46):45777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagathu C, et al. Chronic interleukin-6 (IL-6) treatment increased IL-6 secretion and induced insulin resistance in adipocyte: prevention by Rosiglitazone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311(2):372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutherland JP, McKinley B, Eckel RH. The metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2004;2(2):82–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esposito K, Giugliano D. The metabolic syndrome and inflammation: association or causation? Elsevier; 2004. pp. 228–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hailu W, Tesfaye T, Tadesse A. Hyperglycemia after dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy. Int Med Case Rep J, 2021: pp. 503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Hirigo AT, et al. Experience of dolutegravir-based antiretroviral treatment and risks of diabetes mellitus. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221079444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaughlin M, Walsh S, Galvin S. Dolutegravir-induced hyperglycaemia in a patient living with HIV. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(1):258–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerschenson M, et al. Chronic stavudine exposure induces hepatic mitochondrial toxicity in adult erythrocebus Patas monkeys. J Hum Virol. 2001;4(6):335–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J-a, Wei Y, Sowers JR. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circul Res. 2008;102(4):401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vakili S, et al. Altered adipose tissue macrophage populations in people with HIV on integrase inhibitor-containing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2022;36(11):1493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorwood J, et al. The integrase inhibitors dolutegravir and raltegravir exert proadipogenic and profibrotic effects and induce insulin resistance in human/simian adipose tissue and human adipocytes. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):e549–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohan J, et al. Antiretrovirals promote metabolic syndrome through mitochondrial stress and dysfunction: an in vitro study. Biology. 2023;12(4):580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra Y, Kaundal RK. Role of SIRT3 in mitochondrial biology and its therapeutic implications in neurodegenerative disorders. Drug Discovery Today. 2023;28(6):103583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nedergaard J, et al. UCP1: the original uncoupling protein—and perhaps the only one? New perspectives on UCP1, UCP2, and UCP3 in the light of the bioenergetics of the UCP1-ablated mice. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:475–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hightower KE, et al. Dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572) exhibits significantly slower dissociation than raltegravir and elvitegravir from wild-type and integrase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 integrase-DNA complexes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song I, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir when administered with mineral supplements in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(5):490–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esser N, et al. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105(2):141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domingo P, et al. Differential effects of dolutegravir, bictegravir and raltegravir in adipokines and inflammation markers on human adipocytes. Life Sci. 2022;308:120948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Theron AJ, et al. Pro-inflammatory interactions of dolutegravir with human neutrophils in an in vitro study. Molecules. 2022;27(24):9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auclair M, et al. HIV antiretroviral drugs, dolutegravir, Maraviroc and ritonavir-boosted Atazanavir use different pathways to affect inflammation, senescence and insulin sensitivity in human coronary endothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0226924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calza L, et al. Changes in serum inflammatory markers in antiretroviral therapy–naive HIV-infected patients starting dolutegravir/lamivudine or dolutegravir/lamivudine/abacavir. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;89(3):e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiological reviews; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The Browning of white adipose tissue: some burning issues. Cell Metabol. 2014;20(3):396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brasaemle DL. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(12):2547–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenberg AS, et al. The role of lipid droplets in metabolic disease in rodents and humans. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(6):2102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griesel R, et al. Concentration–response relationships of dolutegravir and Efavirenz with weight change after starting antiretroviral therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(3):883–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(5):687–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staudinger JL, et al. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(6):3369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou C, et al. Mutual repression between steroid and xenobiotic receptor and NF-kappaB signalling pathways links xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yagura H, et al. Impact of UGT1A1 gene polymorphisms on plasma dolutegravir trough concentrations and neuropsychiatric adverse events in Japanese individuals infected with HIV-1. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuchiya K, et al. High plasma concentrations of dolutegravir in patients with ABCG2 genetic variants. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27(11):416–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dabravolski SA et al. The role of mitochondrial mutations and chronic inflammation in diabetes. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Guo LJ, et al. Mitochondrial genome polymorphisms associated with type-2 diabetes or obesity. Mitochondrion. 2005;5(1):15–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nissanka N, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in disease and targeted nuclease-based therapeutic approaches. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(3):e49612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crispim D, et al. The European-specific mitochondrial cluster J/T could confer an increased risk of insulin-resistance and type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the m.4216T > C and m.4917A > G variants. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70(Pt 4):488–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diaz-Morales N et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup JT is related to impaired glycaemic control and renal function in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Med, 2018. 7(8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kamal P, Sharma S. SUN-187 dolutegravir causing diabetes. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(Supplement1):SUN–187. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Banu S, et al. C-peptide and its correlation to parameters of insulin resistance in the metabolic syndrome. CNS Neurol Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Curr Drug Targets-CNS Neurol Disorders). 2011;10(8):921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mauvais-Jarvis F et al. Ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes in patients of sub-Saharan African origin: clinical pathophysiology and natural history of β-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2004. 53(3): pp. 645–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Mauvais-Jarvis F, et al. Ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes in patients of sub-Saharan African origin: clinical pathophysiology and natural history of β-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2004;53(3):645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lontchi-Yimagou E, et al. Ketosis‐prone atypical diabetes in Cameroonian people with hyperglycaemic crisis: frequency, clinical and metabolic phenotypes. Diabet Med. 2017;34(3):426–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.