Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening form of acute lung injury (ALI), which is a common cause of respiratory failure and high mortality in critically ill patients. Long-term mortality and cognitive impairment have been documented in ARDS patients after hospital discharge. Inflammation plays a key role in ALI/ARDS pathogenesis. Neural cholinergic signaling regulates cytokine responses and inflammation. Here, we studied the effects of galantamine, an approved cholinergic drug (for Alzheimer’s disease) on ALI/ARDS severity and inflammation in mice, using a clinically relevant mouse model induced by intratracheal administration of hydrochloric acid and lipopolysaccharide. Mice were treated 30 min prior to each insult with vehicle or galantamine (4 mg/kg, i.p.). Galantamine treatment significantly decreased bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and serum TNF, IL-1b, and IL-6 levels, as well as BAL total protein and myeloperoxidase (MPO) and lung histopathology in ALI/ARDS mice. In addition, galantamine improved the functional state of mice with ALI/ARDS during a 10-day monitoring and attenuated lung injury and indices of brain inflammation at 10 days. These findings support further studies utilizing this approved cholinergic drug in therapeutic strategies for ALI/ARDS and its subacute sequelae.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-18542-5.

Keywords: Galantamine, Cholinergic signaling, Acute lung injury, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Inflammation, Brain

Subject terms: Immunology, Neuroscience, Physiology, Diseases

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening form of acute lung injury (ALI) and respiratory failure. Globally, ARDS affects approximately 3 million patients annually, accounting for more than 10% of intensive care unit admissions1,2. Mortality of patients with ARDS is estimated at 35–46%2. Before 2020, ARDS affected more than 200,000 patients resulting in nearly 75,000 deaths annually in the United States alone1,3. There are also long-term complications in ARDS survivors including respiratory symptoms, as well as physical and mental deterioration for months to years post-initial hospitalization and increased mortality4–10. Brain neurological complications and considerable cognitive impairment including deficiencies in executive function, verbal reasoning, memory, and attention have been reported in survivors of ARDS10,11. The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection added a novel type of insult leading to ALI/ARDS and long-term functional deterioration, including lung complications, physical and neurological manifestations, and cognitive impairment10,12–15. Despite many years of active research, pharmacological treatments for ARDS are limited and its management is largely based on supportive care, including lung-protective mechanical ventilation1.

ALI/ARDS occurs in the context of various pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, toxic inhalation, lung contusion, aspiration, injurious ventilation, and non-pulmonary insults such as sepsis, pancreatitis, trauma, and burns. These insults lead to acute hypoxemia and non-hydrostatic pulmonary edema mediated through epithelium, alveolar macrophages, vascular endothelium alterations, and inflammatory lung injury with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines1,10,16. The exacerbated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) from mononuclear cells during ALI/ARDS and their increased circulating levels mediate systemic inflammation which plays a major role in morbidity and mortality of patients with ARDS16–22.

It has been acknowledged that in addition to initial phases, providing insights into ALI/ARDS at subacute stages using appropriate animal models may inform further developments in the pursuit of new treatments23,24. However, investigations in rodent models continue to focus on ALI/ARDS pathobiology within the first 1–4 days after onset and few studies have examined the acute and subacute ALI/ARDS phases24–26.

Brain and vagus nerve cholinergic mechanisms play a critical role in controlling pro-inflammatory cytokine responses and inflammation27–34. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway is the efferent arm of a major vagus nerve based immunoregulatory mechanism termed the inflammatory reflex that regulates inflammation28,30,35. The efferent vagus nerve interacts with the splenic nerve in the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion complex33,36,37. Further signaling through the splenic nerve mediates the release of acetylcholine from a subset of splenic T cells38. Binding of acetylcholine to the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (a7nAChR) on macrophages and other immune cells triggers intracellular mechanisms mediating suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine release29,38–40. Several studies have reported the anti-inflammatory efficacy of small molecules a7nAChR agonists in many animal models of inflammatory conditions41–45including murine ALI/ARDS46–49.

Cholinergic activation can be achieved using galantamine, an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor approved for treating Alzheimer’s disease50. We and others have shown that galantamine activates cholinergic anti-inflammatory signaling acting through a central mechanism and efferent vagus nerve activity leading to suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammation32,51–54. The beneficial anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects of galantamine have been shown in murine models of endotoxemia, colitis, obesity, and other inflammatory conditions39,50–52,55,56. These studies provided a rationale for successful clinical exploration demonstrating the anti-inflammatory and beneficial cardiometabolic effects of galantamine in people with the metabolic syndrome57,58.

In this study, we used a clinically relevant mouse model of ALI/ARDS26 to examine the effects of treatment with galantamine on the severity of ALI/ARDS and inflammation in acute (30 h) and subacute (10 days) settings. Our results demonstrate that galantamine alleviates lung tissue injury and local and systemic inflammation at 30 h, as well as lung injury and neuroinflammation at 10 days. These findings show that this approved drug should be further examined as a potential treatment for ARDS.

Results

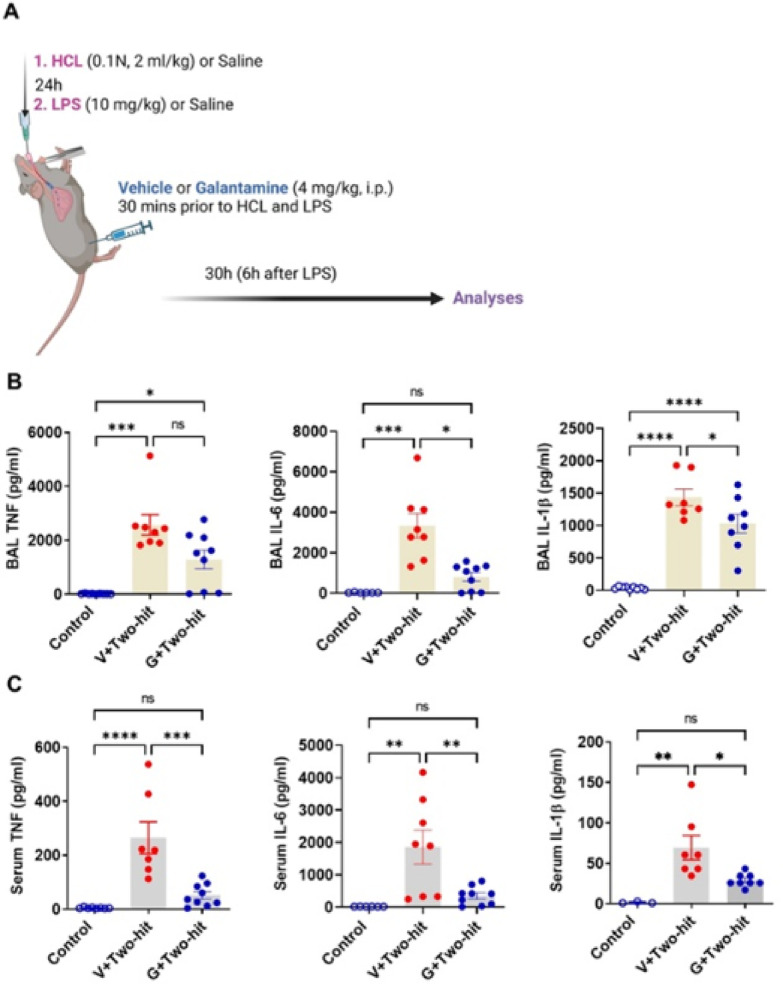

Galantamine suppresses BAL and circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in mice with ALI/ARDS

Increased lung and circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines mediating local and systemic inflammation are a hallmark in patients with ALI/ARDS and cause broader pathogenesis and organ dysfunction16–22. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) intratracheal (i.t.) instillation, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) i.t. instillation are validated and widely used approaches to directly induce ALI/ARDS that mimic toxic inhalation and aspiration-induced human ALI/ARDS, and the effects of a biological insult (bacterial endotoxin), respectively2,23,59–66. We used a model of ALI/ARDS generated by HCl (0.1 N, 2 ml/kg, i.t.) and LPS (10 mg/kg, i.t.) 24 h later, as depicted in Fig. 1A. As previously highlighted, this two-hit model provides a clinically relevant scenario of lung and systemic inflammation, pronounced lung injury, and brain neurological complications at subacute stages compared to the single hits alone26. We first examined the effects of galantamine (4 mg/kg, i.p.) injected 30 min prior to HCl and endotoxin (Fig. 1A) on bronchoalveolar (BAL) and serum cytokine levels in mice with ALI/ARDS at 30 h and the effects of galantamine on these levels. As shown in Fig. 1B, BAL TNF, IL-6, and IL-1b levels were significantly elevated in ALI/ARDS mice compared with control mice. Galantamine treatment significantly decreased BAL IL-6 levels in ALI/ARDS mice to levels no different than those in controls and significantly suppressed BAL IL-1b levels. As the levels of these cytokines were still higher than controls, it remains an open question whether using a higher drug dose would have an additional suppressive effect. Serum TNF, IL-6, and IL-1b levels were also significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS compared with controls (Fig. 1C). Of note, galantamine treatment significantly decreased all these cytokines in mice with ALI/ARDS to levels, that were not statistically different from controls. Collectively these results indicate significant anti-inflammatory effects of cholinergic activation by galantamine in murine ALI/ARDS.

Fig. 1.

Galantamine treatment suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in mice with ALI/ARDS. (A) Schematic depiction of the experimental design. Anesthetized mice were administered with HCL and LPS (i.t.) 24 h apart and treated 30 min prior to each insult with galantamine (4 mg/kg) or vehicle administered i.p. Another (control) group of anesthetized mice was subjected to the same experimental procedure but administered vehicle (saline). Mice were euthanized at 30 h and blood, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), lung and brain (at 10 days) were collected and processed for analysis. (B) BAL TNF levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (V) (***P = 0.0002; Kruskal Wallis test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test) and in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with galantamine (G) (*P = 0.0486) compared with control mice. BAL IL-6 levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle compared with control mice (***P = 0.0002; Kruskal Wallis test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test) and galantamine significantly decreases these levels (*P = 0.0226). BAL IL-1b levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with galantamine (****P < 0.0001) compared with control mice. Galantamine significantly decreases IL-1b levels in mice with ALI/ARDS compared with mice treated with vehicle (*P = 0.0422). (C) Serum TNF levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle than control mice (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and galantamine significantly decreases these values (***P = 0.0003). Serum IL-6 levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle than control mice (**P = 0.0031; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and galantamine significantly decreased these values (**P = 0.0065). Serum IL-1b levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle than control mice (**P = 0.017; Kruskal Wallis test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test) and galantamine significantly decreases these values (*P = 0.0430). Data are represented as individual mouse data points with mean ± SEM. See Materials and Methods for details.

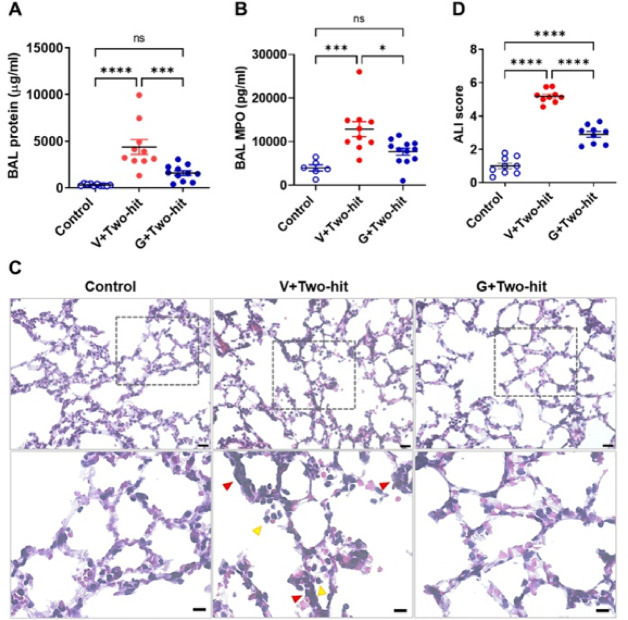

Galantamine treatment alleviates acute lung injury in mice

We also studied the effects of galantamine on BAL markers of lung injury and lung tissue damage evaluated histologically at 30 h after onset. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, at 30 h the levels of total protein and MPO in the BAL were significantly elevated in mice subjected to the two-hit ALI/ARDS and injected with vehicle compared with control mice, processed similarly, but administered i.t. with saline. Galantamine significantly decreased BAL total protein and BAL MPO at 30 h to levels that were not statistically different compared with control mice (Fig. 2A, B). Histological examination of the lung in the three groups of mice revealed a greater presence of neutrophils in the alveolar space and cell walls, as well as instances of hyaline membranes, and alveolar wall thickening in ALI/ARDS mice treated with vehicle compared with controls and ARDS mice treated with galantamine (Fig. 2C). Whole lung sections are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Quantitative evaluation implementing a scoring system as per the guidelines and suggestions of The American Thoracic Society66 demonstrated higher lung injury scores in ALI/ARDS mice compared with controls and significantly decreased scores in ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine (Fig. 2D). These results show that galantamine ameliorates acute lung injury in mice.

Fig. 2.

Galantamine treatment ameliorates markers of acute lung damage in mice with ALI/ARDS. (A) At 30 h BAL total protein levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (Veh) (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) compared with control mice and galantamine treatment significantly decreases BAL total protein in ALI/ARDS mice (**P = 0.0007) to levels no different than controls. (B) BAL MPO levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle than control mice (***P < 0.0005; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and galantamine significantly decreases these values (***P = 0.00125) to levels no different than controls. ((C) Representative H&E images of mouse lung tissue sections show the degree of ALI injury in the two-hit model, including neutrophil infiltration in alveolar space (yellow arrowheads) and interstitial space (red arrowheads). Top row images, scale bar = 20 μm; bottom row images, scale bar = 10 μm. (D) The acute lung injury score in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and those treated with galantamine (****P < 0.0001) is significantly higher compared with controls. Galantamine treatment of mice with ALI/ARDS significantly decreases the score compared with vehicle treatment (****P < 0.0001). Each individual point represents an average of 5 sections that were scored. Data are represented as individual mouse data points with mean ± SEM. See Materials and Methods for details.

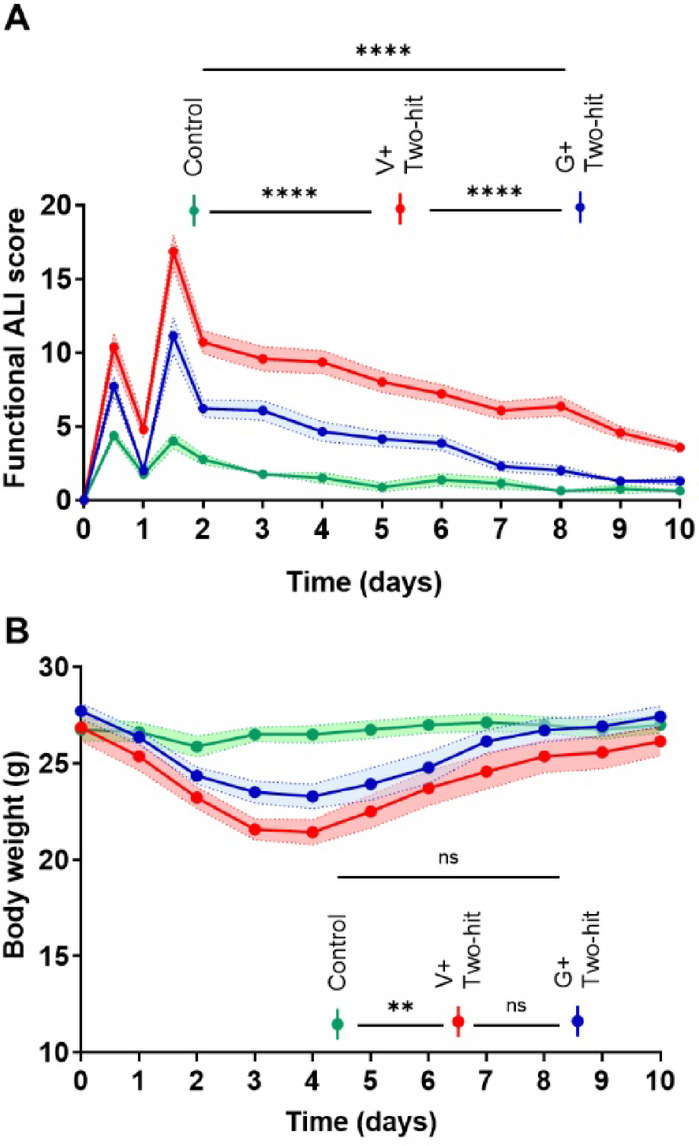

Galantamine improves general functional activity in mice with ALI/ARDS

We next studied functional alterations in the three groups of mice implementing a 10-day monitoring protocol and utilizing a previously established non-invasive scoring system67. This system, originally developed for assessing mice with sepsis is based on seven clinical variables, including appearance, level of consciousness, activity, response to stimulus, eye opening, respiratory rate, and quality of respirations67. Because alterations in all these variables are present in mice with ALI/ARDS, we reasoned that the use of this scoring system would be appropriate. As shown in Fig. 3A, the functional/illness score of mice subjected to the two-hit (i.t.) ALI/ARDS and treated with vehicle was significantly worsened compared with control mice. The illness severity was significantly ameliorated in ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine. We also monitored body weight of the three groups of mice for 10 days. As shown in Fig. 3B a significant overall body weight loss was observed in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle compared with control mice. However, no statistically significant difference was found between control mice and mice subjected to ALI/ARDS and treated with galantamine. These results indicate that the beneficial effects of galantamine on acute lung injury and inflammation are associated with alleviated illness severity and improved overall functional activity, with lack of significant body weight loss.

Fig. 3.

Galantamine treatment improves the functional activity of mice with ALI/ARDS with no effect on body weight. (A) Mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (n = 14) or galantamine (n = 14) have impaired functional activity indicated by high illness scores compared with controls (n = 8) (***P < 0.0001; repeated measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) during 10-day monitoring. Galantamine treatment improves the functional activity of mice with AIL/ARDS reflecting a significantly lower illness score compared with vehicle treatment (***P < 0.0001). (B) The overall body weight of mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (n = 14) is significantly lower compared with controls (n = 8) (**P = 0.0058; repeated measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and not significantly different than ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine during 10-day monitoring. Shading represents SEM. See Materials and Methods for details.

Galantamine alleviates subacute lung injury in mice with ALI/ARDS

We next examined lung injury indices in the three groups of mice after 10 days. BAL total protein levels were significantly increased in mice with ALI/ARDS compared with control mice (Fig. 4A). Similarly, BAL MPO in ALI/ARDS mice was significantly elevated compared with controls (Fig. 4B). However, there were no statistically significant differences in BAL total protein and MPO between control mice and mice with ALI/ARDS treated with galantamine (Fig. 4A, B). There also were overall trends to lower BAL total protein and BAL MPO in ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine compared with ALI/ARDS mice treated with vehicle. In addition to these markers of local tissue injury, we measured BAL and circulating TNF levels in mice in the three groups at 10 days after onset. BAL TNF levels in mice with ALI/ARDS were very low (as compared to those determined at 30 h, Fig. 2A) and no different than TNF levels in control mice or in ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Similarly, we determined very low serum TNF levels in ALI/ARDS mice and no significant differences comparing the three groups of mice (Supplementary Fig. 2B). We also measured BAL levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1068 with a recognised role in decreasing lung inflammation69. Low BAL IL-10 levels were detected with no significant difference between the three groups of mice (Supplementary Fig. 2C). As shown on representative images (Fig. 4C), histological evaluation of the lung across the three groups of mice at 10 days revealed persistent lung damage, including prominent infiltration of neutrophils in the alveolar and interstitial spaces, alveolar wall thickening, and sparse proteinaceous in mice subjected to ALI/ARDS compared with controls and ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine. Whole lung sections are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Accordingly, the lung injury score was significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle compared with controls and galantamine treatment of ALI/ARDS mice significantly lowered the score to levels close to the control group levels (P = 0.06, One-way ANOVA, Kruskal Wallis) (Fig. 4D). Together these results show that galantamine attenuates features of persistent subacute (at 10 days) lung injury in mice with ALI/ARDS with no significant effect on low pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels at this stage (where the inflammatory state has subsided).

Fig. 4.

Galantamine treatment attenuates indices of subacute ALI/ARDS in mice. (A) BAL total protein levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle (Veh) (****P = 0.0014; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) compared with control mice and not significantly different than ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine. (B) BAL MPO levels are significantly higher in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle than control mice (***P = 0.0199; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) and not significantly different than ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine. (C) Representative H&E images of mouse lung tissue sections show the degree of ALI injury in the two-hit model after 10 days, including neutrophil infiltration in interstitial space (red arrowheads) and thickening of hyaline membranes (green arrowheads). Top row images, scale bar = 20 μm; bottom row images, scale bar = 10 μm. (D) The lung injury score in mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle is significantly higher compared with controls (****P < 0.0001; Kruskal Wallis test, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). Galantamine treatment of mice with ALI/ARDS significantly decreases the score compared with vehicle treatment (**P < 0.0099). Each individual point represents an average of 5 sections that were scored. Data are represented as individual mouse data points with mean ± SEM. See Materials and Methods for details.

Galantamine reduces microglial accumulation in the hippocampus of mice with ALI/ARDS

In addition to lung and systemic pathobiological sequalae, persistent cognitive impairment has been documented in ARDS survivors after hospital discharge6. Behavioral alterations and impaired spatial learning and memory have been previously associated with hippocampal alterations at subacute stages in a two-hit ALI/ARDS murine model26. Both clinical and animal studies have demonstrated an association between brain inflammation (neuroinflammation) and microglial alterations, cognitive impairment, and hippocampal neuronal dysfunction70. Accordingly, we next studied whether there were microglial alterations in the hippocampus in the three groups of mice. Using IBA1 immunolabeling, we observed significantly higher numbers of microglia in mice with ALI/ARDS compared with controls. The number of microglia in the hippocampus of ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine was significantly lower compared with the ALI/ARDS mice treated with vehicle and not statistically different than control mice (Fig. 5A and B). Additional analysis of hippocampal microglial ramification implementing a previously utilized methodology71,72 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 demonstrated significantly increased values in mice with ALI/ARDS compared with controls (Fig. 5C). Galantamine treatment of mice with ALI/ARDS significantly reduced these values to levels which were not statistically different than controls (Fig. 5C). These results indicate increased inflammation in the hippocampus in mice with ALI/ARDS at a subacute (10 day) stage and the counteracting anti-inflammatory effect of galantamine treatment.

Fig. 5.

Galantamine treatment decreases microglial accumulation in the hippocampus of mice with subacute ALI/ARDS. (A) Representative images of IBA1 staining of brain (hippocampus) shown in wide tiles (Scale bar = 200 μm) and with 20x magnification (Scale bar = 50 μm in the three groups of mice. (B) The number of microglia in the hippocampus of mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle is significantly higher compared with controls (***P = 0.0008; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Galantamine treatment of mice with ALI/ARDS significantly decreases microglial accumulation in the hippocampus compared with vehicle treatment (*P = 0.0181). (C) The ramification index of microglia in the hippocampus of mice with ALI/ARDS treated with vehicle is significantly higher compared with controls (**P = 0.001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Galantamine treatment of mice with ALI/ARDS significantly decreases the microglial ramification index in the hippocampus compared with vehicle treatment (*P = 0.029). Data are represented as individual mouse data points with mean ± SEM. See Materials and Methods for details.

Discussion

ALI/ARDS is a common life-threatening disease with high in-hospital mortality. ARDS mortality extends beyond the acute phase in parallel with considerable physical, mental, and cognitive deterioration for years after hospital discharge. This dictates the need for finding better treatments with good safety profiles. Local lung and systemic inflammation with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines play a major role in ALI/ARDS pathogenesis. Here we show that galantamine, an AChE inhibitor and a cholinergic compound with previously established anti-inflammatory activity, alleviates murine ALI/ARDS and attenuates local (BAL) and systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. In addition, galantamine treatment improves the functional activity of mice with ALI/ARDS monitored for 10 days, ameliorates lung injury, and decreases hippocampal neuroinflammation at subacute stages of the condition.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, IL-6, and IL-1b are validated markers of ongoing cellular injury and their increased BAL levels have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with ALI/ARDS19,73. These increases reflect simultaneous elevation in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels driving further pathogenesis73. In our study, at 30 h galantamine inhibited BAL and systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β - in many instances to levels not significantly different than those in control mice. BAL total protein is a recognized marker of vascular/capillary leakage and BAL myeloperoxidase (MPO), released by activated neutrophils, is a validated indicator of accumulation of activated neutrophils within the lung airspaces66. At 30 h, the significantly lower levels of BAL total protein and MPO in ALI/ARDS mice treated with galantamine are consistent with a beneficial effect of this cholinergic drug on these processes, which play a key role in ALI pathogenesis. In line with these observations, histological assessment of the lung revealed that galantamine also significantly alleviated ALI.

Long-term mortality and morbidity in patients surviving ARDS remains a significant medical problem. While abundant insights into the initial inflammatory injury have been provided, the subacute consequences of ALI/ARDS in murine models have not been adequately evaluated. We found that the effects of galantamine on ALI were associated with significantly reduced illness score in mice with ALI/ARDS compared to vehicle-treated mice during the 10-day monitoring. This is indicative for multifactorial beneficial effects of galantamine, which cannot be attributed or related to counteracting the weight loss because of the lack of significant drug effect. Histological analysis revealed the presence of significant lung injury and notably an increased alveolar wall thickness in ALI/ARDS mice at 10 days following the initial insult. This finding is consistent with the persistent lung injury documented in patients surviving ARDS13,74. Importantly, galantamine treatment considerably and significantly prevented/attenuated these alterations.

Histological findings in mice with ALI/ARDS were in line with significantly increased BAL total protein and MPO levels, albeit not to levels observed in acute settings (at 30 h). Of note, these increases in galantamine treated animals compared with control mice were not significant. We also found that while lung injury persisted at subacute stages and galantamine had beneficial effects there was no significant alterations in BAL and serum pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. This may suggest the possibility of additional galantamine regulation of repair mechanisms such as fibrosis at later stages through non-cytokine-dependent mechanisms and effects on oxidative stress, which can be studied in the future. In the brain, we found a significantly higher density of hippocampal microglia with increased ramifications in mice with ALI/ARDS, with galantamine decreasing these to control levels. Previous studies have indicated the impact of increased peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as inflammatory and metabolic derangements on the brain associated with microglial alterations indicative of neuroinflammation75–77. In addition to being a key component of brain immunity, microglia interact with neurons to maintain neuronal integrity and function78,79. Microglial activation and higher numbers drive brain inflammation with a deleterious effect on the neurons29,80,81. The hippocampus is a brain area in which microglial alterations have been documented during aberrant systemic inflammation and increased circulatory levels of IL-6 and other cytokines80,81. Hence, while no difference in pro-inflammatory cytokines was detected at 10 days, it is reasonable to suggest that circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines increased at earlier stages may enter the brain and trigger neuroinflammatory responses, including brain microglial activation. Such a suggestion is in agreement with the increase in blood brain barrier permeability previously shown in this model of ALI/ARDS26. Furthermore, this neuroinflammation in the hippocampus may contribute to the previously shown cognitive impairment shown at late stages of ALI/ARDS in this murine model using behavioral testing, i.e., the Morris water maze test26. This test is a valuable tool for studying hippocampal function which plays a crucial role in spatial learning and memory26,82. Our results indicating that galantamine alleviates inflammation in the hippocampus are consistent with previous findings that galantamine decreases neuroinflammation in other mouse models of inflammatory conditions50. Studying the effects of galantamine on behavior of mice with ALI/ARDS would be in interesting component of future studies.

Of note, we used only male mice (and not female mice) and did not perform any analyses after the 10 days, which can be considered as limitations of the current study. Future studies may highlight additional insights, including the role of vagus nerve signaling and the a7nAChR and other components of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in mediating the beneficial galantamine effects in mice with ALI/ARDS.

Galantamine is a competitive and reversible AChE inhibitor that crosses the blood brain barrier, significantly increases brain cholinergic network activity83,84 and activates vagus nerve outflow53. Galantamine (4 mg/kg) has been shown to inhibit mouse brain AChE activity by 43%85. Brain cholinergic signaling plays an important role in cognition86,87. Galantamine is approved for the symptomatic treatment of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease87,88 with a sustained (36 months) effect89. Galantamine doses, including the dose used in our study significantly inhibit rodent brain AChE activity in levels that can be achieved in patients90,91.

Previous studies have revealed the robust anti-inflammatory efficacy of galantamine50,57,58 and its beneficial metabolic and cardioprotective effects50,57,92–95. Dose dependent anti-inflammatory effects of galantamine within the range 1–6 mg/kg, i.p. have been previously demonstrated in mouse models of inflammatory conditions51,52,96. In our study we used a galantamine dose of 4 mg/kg, with previously shown anti-inflammatory and beneficial metabolic effects in mice with endotoxemia51colitis52obesity and metabolic syndrome55pancreatitis96 and other conditions50,97. This dose provides an approximate human equivalent dose calculated allometrically98 to be 0.33 mg/kg body weight respectively, which is within the dosing range of humans receiving treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (0.13 to 0.40 mg/kg body weight). Therefore, our findings generated in mice by using a dose of galantamine, which is within the range of clinically approved doses (for Alzheimer’s disease) are of substantial interest for direct translational studies in patients with ARDS. Such investigations can be significantly facilitated by the abundant available information indicating a favorable safety drug profile; in addition to Alzheimer’s disease galantamine has been clinically utilized in many other populations, including children with autism with no notable adverse events50,99,100. Understandably, the use of galantamine in ARDS patients will need to be carefully reevaluated from the perspective of differences in pharmacokinetics among critically ill patients, specific pathological features, and interactions with mechanical ventilation and other drugs. Galantamine has also been successfully used in the treatment of muscle weakness50. Persistent muscle weakness has been documented as a key component of physical deterioration in ARDS survivors for years after acute hospital care, severely worsening their mobility and quality of life15,101. Therefore, it would be of interest to consider galantamine treatment in this context as well.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that galantamine administered in mice with ALI/ARDS significantly alleviates local (BAL) and circulating cytokine responses and attenuates acute lung damage at early stages (30 h). We also show that galantamine improves the overall functional state, attenuates lung injury, and ameliorates neuroinflammatory alterations at subacute stages (10 days) of murine ALI/ARDS. While it is recognized that the long-term ARDS sequelae can be prevented or treated at earliest stages of hospital care15 no efficient targeted pharmacological treatments are available. These findings provide a rationale for studying galantamine, an approved cholinergic drug, in the management of acute and subacute (long-term) ALI/ARDS.

Materials and methods

Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the Institutional Biosafety Committee of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY approved all procedures described. All procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines. The study was performed and reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). In experiments with anesthetized mice a surgical plane of anesthesia was maintained throughout the entire procedure. Any animal discomfort, distress, pain, or injury was limited to that which is unavoidable in the conduct of scientifically and medically sound research. The individuals performing the procedures provided care in the immediate post-operative period. They observed the animals continuously until recovery from anesthesia was complete and the mice become mobile. All blood and tissue collections occurred post-mortem.

Male, C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All mice were given access to food and water ad libitum and maintained on a 12 h light and dark schedule at 25o C and fed a standard Purina rodent chow diet (Rodents - Feed and nutrition products | Purina (multipurina.ca)). Mice were allowed to acclimate to the environment for two weeks before being used in experiments. Experiments were conducted on male mice aged 10–12 weeks old.

Two-hit acute lung injury and treatment with galantamine

To induce lung injury, we followed a previously described procedure26. Mice were anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine (75–100 mg/kg/5-10 mg/kg, i.p.) and mounted on an intubation platform (KentScientific). Mice were hung from their front incisors, exposing, and lengthening the trachea. An optical fibre, with an attached safety cap of a catheter needle, was used to locate the trachea and the safety cap was placed into the trachea. Location was verified by attaching a saline filled syringe to the safety cap and observing an apparent rhythmic gas transfer. A catheter was then inserted into the trachea via the safety cap and hydrochloric acid HCl (0.2 N, 2 ml/kg) was slowly instilled. Animals were allowed to recover in a heated cage. 24 h later LPS (10 mg/kg) intratracheal (i.t.) instillation was performed as described above. Another group of control mice was similarly anesthetised and subjected to i.t. saline (instead of HCL and LPS administration). Animals were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with vehicle (saline) or galantamine (4 mg/kg. i.p.) 30 min prior to HCL and LPS i.t. administration. The animals were allowed to recover and 6 h after LPS administration (30 h after onset - HCL administration) they were euthanised. Other cohorts of mice were euthanised at 10 days after onset. Animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Blood was collected through cardiac puncture. The left lung lobe was excised for histology and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected from the right lung. Brains (in the 10-day experiments) were collected) and passively perfused for 72 h in 4% PFA prior to transfer to 30% sucrose and allowed to equilibrate prior to processing for tissue sectioning.

BAL fluid collection and analyses

Following blood collection via cardiac puncture, the ribcage was fully removed, and the lungs were exposed and the skin/muscle layer covering the trachea was additionally removed. The trachea was pierced with a catheter needle and a guiding syringe was left in the trachea and sutured in place. Three distinct rounds of 0.1 ml + 0.5 ml cold PBS were flushed into and back out of the right lung to collect BAL fluid, samples were frozen and stored until use.

Lung histochemistry evaluation

Lungs were processed for H&E staining following a previously published method102. In brief, the lungs and trachea were removed, a syringe containing 4% paraformaldehyde was placed into the trachea and the lungs were re-inflated until they returned to their physiological size. Subsequently, the lungs were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for passive tissue fixing and then 48 h in 30% sucrose. The left lung was covered with OCT, frozen and then stored at -80 degrees Celsius prior to sectioning on a cryostat at 10 microns. Sections of the left lung (10 microns) were stained with H&E following a standard procedure102. Lung sections were histologically evaluated using a scoring system established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS), which yields an acute lung injury (ALI) score66. The scoring system consists of five variables that are scored from 0 to 2 depending on the lung injury severity: neutrophils in the alveolar space; neutrophils in the interstitial space; hyaline membranes; proteinaceous debris filling the airspaces and alveolar septal thickening. The summative score for each scoring criteria across the lung section was recorded, with a higher ALI score reflecting greater severity of acute lung injury.

Analyte measurement

BAL total protein was determined using a Bradford analysis kit. MPO activity was determined using (R&D Systems DY3667). Blood was withdrawn and centrifuged for serum analysis. BAL fluid and serum were analyzed for cytokine levels using standard ELISA kits: TNF (88-7324: Invitrogen); IL-6 (R&D Systems DY406); IL-1b (R&D Systems DY401) and IL-10 (R&D Systems DY417). BAL and serum cytokines were expressed as picogram per milliliter of BAL or serum collected. All BAL analyte values were additionally standardized to the volume of BAL fluid collected.

Functional assessment

Groups of mice were weighted and evaluated using a scoring system involving variables, such as fur quality, consciousness, ambulation, response to stimuli, openness of the eyes, respiration rate and quality, and providing scores from low (0) – high severity (4)67. The scoring was independently performed by two investigators, one of which was blinded to the experimental groups. The pathophysiological changes evaluated using this system initially designed for assessing the severity of a sepsis mouse model are broadly applicable to other mouse models of inflammatory disorders and measuring disease progression. Mice were initially monitored and scored prior to treatment and approximately 6 h later. On the next day mice were again weighted and scored prior to treatment and about 6 h post treatment. Then, scoring and body weigh were performed every morning until the end of the 10-day monitoring.

Brain processing, IBA1 immunohistochemistry, and quantification

Brains were excised and passively perfused in 4% PFA solution at 4℃ for 72 h and then transferred to 30% sucrose solution. Following embedding in OCT, sagittal brain Sect. (10 μm) were prepared on a Leica CM1850 cryostat. Following fixation, frozen sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS solution and incubated in blocking solution consisting of 10% Normal donkey serum (Southern Biotech, 0030 − 01) and 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS for one hour at room temperature. Next, tissues were incubated with rabbit Anti-IBA1 (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, 019-19741) diluted in 0.1% Triton-100 and 10% NDS with 1X PBS overnight at 4℃. Next, sections were rinsed three times with 1x PBS-Triton X-100 (0.1 M PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated with donkey Anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (ThermoFisher, A32795) diluted in 0.1% Triton-100 and 10% NDS with 1X PBS overnight at 4℃. Lastly, tissues were rinsed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS and counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Scientific, 62248). Slides were cover slipped with Fluoromount Mounting Medium (SouthernBiotech, 0100-01). Fluorescent images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 900 confocal microscope. Images were processed and analyzed using ZEISS ZEN blue software (Blue Edition, version 3.5, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, White Plains, NY), https://www.micro-shop.zeiss.com/en/us/softwarefinder/software-categories/zen-blue/. Microglia density was analyzed by a wide count of IBA1 + cells across the hippocampal region. IBA1 + cells were selected for evident expression of DAPI + nuclear staining with cytoplasmic staining of IBA1 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Following the count, microglia cells were selected within the CA1 region of the hippocampus to assess the degree of ramification. Utilizing a previously established ramification index, individual IBA1 + cells were first marked for their cell body area, which encompasses the branching and extension of microglial processes (include citation number here). The perimeter of these microglial processes was then marked to assess the area covered by the total length of these processes. The ramification index was calculated by dividing the area by the perimeter, with a lower ratio of cell body area to the perimeter reflecting a more ramified microglia morphology.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses of experimental data were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). After evaluating the data for normality using a Shapiro-Wilk test, differences between groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal Wallis test with appropriate post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Typically, data was pooled from experiments with multiple small cohorts of animals with a total number of animals per group consistent with previous studies on galantamine anti-inflammatory effects in murine models of inflammatory conditions. Functional assessment curves and body weight were analyzed using repeated measures two-way ANOVA. All individual points in the graphs of Figs. 1, 2, 4, and 5 refer to one animal and represent the number of animals per group. The number of animals per group in the results from experiments depicted in Fig. 3 is mentioned in the figure legend. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All specific statistical tests are listed in the figure legends.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants: RO1GM128008 and RO1GM121102 (to VAP), and R35GM118182 (to KJT).

Author contributions

A.F. and V.A.P. conceived the project. A.F., V.A.P., A.T., C.N.M., and E.H.C. designed experiments. A.F., S.C., and S.P.P. performed experiments. A.F., S.C., E.H.C., and V.A.P. analyzed data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. V.A.P. wrote the first draft and A.F., M.B., E.H.C., S.S.C., F.C.C., A.T., C.N.M., F.C.C., and K.J.T. provided comments. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided additional comments. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

VAP and KJT have co-authored patents broadly related to the content of this paper. They have assigned their rights to the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. AF, SPP, SC, AT, FMC, CNM, MB, EHC, and SSC declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan, E., Brodie, D. & Slutsky, A. S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Jama319, 698–710. 10.1001/jama.2017.21907 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellani, G. et al. Patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. Jama315, 788–800. 10.1001/jama.2016.0291 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfeld, G. D. et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med.353, 1685–1693. 10.1056/NEJMoa050333 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herridge, M. S. et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med.348, 683–693. 10.1056/NEJMoa022450 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herridge, M. S. et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med.42, 725–738. 10.1007/s00134-016-4321-8 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasannejad, C., Ely, E. W. & Lahiri, S. Long-term cognitive impairment after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a review of clinical impact and pathophysiological mechanisms. Crit. Care. (London, England). 23, 352. 10.1186/s13054-019-2626-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins, R. O. et al. Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med.171, 340–347. 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikkelsen, M. E. et al. Cognitive, mood and quality of life impairments in a select population of ARDS survivors. Respirol. (Carlton Vic). 14, 76–82. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01419.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bienvenu, O. J. et al. Psychiatric symptoms after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med.44, 38–47. 10.1007/s00134-017-5009-4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman, E. A., O’Kane, C. M. & McAuley, D. F. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: diagnosis, outcomes, long-term sequelae, and management. Lancet400, 1157–1170. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01439-8 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, S. M. et al. Understanding patient outcomes after acute respiratory distress syndrome: identifying subtypes of physical, cognitive and mental health outcomes. Thorax72, 1094–1103 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aranda, J. et al. Long-term impact of COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Infect.83, 581–588. 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.018 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturgill, J. L. et al. Post-intensive care syndrome and pulmonary fibrosis in patients surviving ARDS-pneumonia of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 etiologies. Sci. Rep.13, 6554. 10.1038/s41598-023-32699-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslan, A., Aslan, C., Zolbanin, N. M. & Jafari, R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19: possible mechanisms and therapeutic management. Pneumonia13, 14. 10.1186/s41479-021-00092-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latronico, N., Eikermann, M., Ely, E. W. & Needham, D. M. Improving management of ARDS: uniting acute management and long-term recovery. Crit. Care. 28, 58. 10.1186/s13054-024-04810-9 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han, S. & Mallampalli, R. K. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: from mechanism to translation. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, Md.)194, 855–860, (1950). 10.4049/jimmunol.1402513 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Meduri, G. U., Annane, D., Chrousos, G. P., Marik, P. E. & Sinclair, S. E. Activation and regulation of systemic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest136, 1631–1643. 10.1378/chest.08-2408 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buttenschoen, K. et al. Endotoxemia and endotoxin tolerance in patients with ARDS. Langenbeck’s Archives Surg.393, 473–478. 10.1007/s00423-008-0317-3 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meduri, G. U. et al. Persistent elevation of inflammatory cytokines predicts a poor outcome in ARDS: plasma IL-1β and IL-6 levels are consistent and efficient predictors of outcome over time. Chest107, 1062–1073. 10.1378/chest.107.4.1062 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baughman, R. P., Gunther, K. L., Rashkin, M. C., Keeton, D. A. & Pattishall, E. N. Changes in the inflammatory response of the lung during acute respiratory distress syndrome: prognostic indicators. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med.154, 76–81 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons, P. E. et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med.33, 1–6 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meduri, G. U., Tolley, E. A., Chrousos, G. P. & Stentz, F. Prolonged Methylprednisolone treatment suppresses systemic inflammation in patients with unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: evidence for inadequate endogenous glucocorticoid secretion and inflammation-induced immune cell resistance to glucocorticoids. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med.165, 983–991 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Alessio, F. R. Mouse Models of Acute Lung Injury and ARDS. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1809, 341–350, (2018). 10.1007/978-1-4939-8570-8_22 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.D’Alessio, F. R. et al. CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + Tregs resolve experimental lung injury in mice and are present in humans with acute lung injury. J. Clin. Investig.119, 2898–2913. 10.1172/jci36498 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer, B. D. et al. Regulatory T cell DNA methyltransferase Inhibition accelerates resolution of lung inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.52, 641–652. 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0327OC (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahu, B., Sandhir, R. & Naura, A. S. Two hit induced acute lung injury impairs cognitive function in mice: A potential model to study cross talk between lung and brain. Brain. Behav. Immun.73, 633–642. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.013 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex–linking immunity and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.8, 743–754. 10.1038/nrendo.2012.189 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. Neural regulation of immunity: molecular mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat. Neurosci.20, 156–166. 10.1038/nn.4477 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlov, V. A., Chavan, S. S. & Tracey, K. J. Molecular and functional neuroscience in immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol.36, 783–812. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053158 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. Bioelectronic medicine: preclinical insights and clinical advances. Neuron110, 3627–3644. 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.09.003 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falvey, A., Metz, C. N., Tracey, K. J. & Pavlov, V. A. Peripheral nerve stimulation and immunity: the expanding opportunities for providing mechanistic insight and therapeutic intervention. Int. Immunol.10.1093/intimm/dxab068 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehner, K. R. et al. Forebrain cholinergic signaling regulates innate immune responses and inflammation. Front. Immunol.1010.3389/fimmu.2019.00585 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kressel, A. M. et al. Identification of a brainstem locus that inhibits tumor necrosis factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.117, 29803–29810. 10.1073/pnas.2008213117 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falvey, A. et al. Electrical stimulation of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in male mice can regulate inflammation without affecting the heart rate. Brain. Behav. Immun.10.1016/j.bbi.2024.04.027 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tracey, K. J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature420, 853–859. 10.1038/nature01321 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berthoud, H. R. & Powley, T. L. Characterization of vagal innervation to the rat celiac, suprarenal and mesenteric ganglia. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst.42, 153–169. 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90046-w (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berthoud, H. R. & Powley, T. L. Interaction between parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves in prevertebral ganglia: morphological evidence for vagal efferent innervation of ganglion cells in the rat. Microsc. Res. Tech.35, 80–86. (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosas-Ballina, M. et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Sci. (New York N Y). 334, 98–101. 10.1126/science.1209985 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. Neural circuitry and immunity. Immunol. Res.63, 38–57. 10.1007/s12026-015-8718-1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, H. et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature421, 384–388. 10.1038/nature01339 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parrish, W. R. et al. Modulation of TNF release by choline requires alpha7 subunit nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated signaling. Mol. Med.14, 567–574. 10.2119/2008-00079.Parrish (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavlov, V. A. et al. Selective alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med.35, 1139–1144. 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000259381.56526.96 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keever, K. R. et al. Cholinergic signaling via the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor regulates the migration of monocyte-derived macrophages during acute inflammation. J. Neuroinflamm.2110.1186/s12974-023-03001-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Bencherif, M., Lippiello, P. M., Lucas, R. & Marrero, M. B. Alpha7 nicotinic receptors as novel therapeutic targets for inflammation-based diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.68, 931–949. 10.1007/s00018-010-0525-1 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Jonge, W. & Ulloa, L. The alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor as a Pharmacological target for inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol.151, 915–929 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sitapara, R. A. et al. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, GTS-21, attenuates hyperoxia-induced acute inflammatory lung injury by alleviating the accumulation of HMGB1 in the airways and the circulation. Mol. Med.26, 63. 10.1186/s10020-020-00177-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinheiro, N. M. et al. Acute lung injury is reduced by the α7nAChR agonist PNU-282987 through changes in the macrophage profile. FASEB J.: Official Publication Federation Am. Soc. Exp. Biol.. 31, 320–332. 10.1096/fj.201600431R (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su, X. et al. Activation of the alpha7 nAChR reduces acid-induced acute lung injury in mice and rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.37, 186–192. 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0240OC (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gauthier, A. G. et al. The positive allosteric modulation of alpha7-Nicotinic cholinergic receptors by GAT107 increases bacterial lung clearance in hyperoxic mice by decreasing oxidative stress in macrophages. Antioxidants10, 135 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metz, C. N. & Pavlov, V. A. Treating disorders across the lifespan by modulating cholinergic signaling with galantamine. J. Neurochem.158, 1359–1380. 10.1111/jnc.15243 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pavlov, V. A. et al. Brain acetylcholinesterase activity controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain. Behav. Immun.23, 41–45. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.011 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ji, H. et al. Central cholinergic activation of a vagus nerve-to-spleen circuit alleviates experimental colitis. Mucosal Immunol.7, 335–347. 10.1038/mi.2013.52 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldburger, J. M. et al. Spinal p38 MAP kinase regulates peripheral cholinergic outflow. Arthritis Rheum.58, 2919–2921. 10.1002/art.23807 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pham, G. S., Wang, L. A. & Mathis, K. W. Pharmacological potentiation of the efferent vagus nerve attenuates blood pressure and renal injury in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.10.1152/ajpregu.00362.2017 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Satapathy, S. K. et al. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and other obesity-associated complications in high-fat diet-fed mice. Mol. Med.17, 599–606. 10.2119/molmed.2011.00083 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pavlov, V. A. The evolving obesity challenge: targeting the vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex in the response. Pharmacol. Ther.222, 107794. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107794 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Consolim-Colombo, F. M. et al. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome in a randomized trial. JCI Insight. 210.1172/jci.insight.93340 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Sangaleti, C. T. et al. The cholinergic drug galantamine alleviates oxidative stress alongside Anti-inflammatory and Cardio-Metabolic effects in subjects with the metabolic syndrome in a randomized trial. Front. Immunol.1210.3389/fimmu.2021.613979 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Chimenti, L. et al. Comparison of direct and indirect models of early induced acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. Experimental. 8, 62. 10.1186/s40635-020-00350-y (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matute-Bello, G., Frevert, C. W. & Martin, T. R. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol.295, L379–399. 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiss, L. K., Uhlig, U. & Uhlig, S. Models and mechanisms of acute lung injury caused by direct insults. Eur. J. Cell Biol.91, 590–601. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.11.004 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Plataki, M. et al. Fatty acid synthase downregulation contributes to acute lung injury in murine diet-induced obesity. JCI Insight. 510.1172/jci.insight.127823 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Bastarache, J. A. & Blackwell, T. S. Development of animal models for the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Dis. Models Mech.2, 218–223. 10.1242/dmm.001677 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zarbock, A., Singbartl, K. & Ley, K. Complete reversal of acid-induced acute lung injury by blocking of platelet-neutrophil aggregation. J. Clin. Investig.116, 3211–3219. 10.1172/jci29499 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhandari, V. et al. Hyperoxia causes angiopoietin 2–mediated acute lung injury and necrotic cell death. Nat. Med.12, 1286–1293. 10.1038/nm1494 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matute-Bello, G. et al. An official American thoracic society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.44, 725–738. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shrum, B. et al. A robust scoring system to evaluate sepsis severity in an animal model. BMC Res. Notes. 7, 233. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-233 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moore, K. W., de Waal Malefyt, R. & Coffman, R. L. O’Garra, A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol.19, 683–765 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shanley, T. P. & Vasi, N. Denenberg, A regulation of chemokine expression by IL-10 in lung inflammation. Cytokine12, 1054–1064. 10.1006/cyto.1999.0655 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao, J. et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci. Rep.9, 5790. 10.1038/s41598-019-42286-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Becker, B. et al. Effect of intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesions on extrastriatal brain structures in the mouse. Mol. Neurobiol.55, 4240–4252. 10.1007/s12035-017-0637-9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Madry, C. et al. Microglial ramification, surveillance, and Interleukin-1β release are regulated by the Two-Pore domain K(+) channel THIK-1. Neuron97, 299–312e296. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.002 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mowery, N. T., Terzian, W. T. H. & Nelson, A. C. Acute lung injury. Curr. Probl. Surg.57, 100777. 10.1016/j.cpsurg.2020.100777 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGroder, C. F. et al. Pulmonary fibrosis 4 months after COVID-19 is associated with severity of illness and blood leucocyte telomere length. Thorax76, 1242–1245. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217031 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoogland, I. C., Houbolt, C., van Westerloo, D. J., van Gool, W. A. & van de Beek, D. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: systematic review of animal experiments. J. Neuroinflamm.12, 114. 10.1186/s12974-015-0332-6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palandira, S. P. et al. A dual tracer [(11)C]PBR28 and [(18)F]FDG micropet evaluation of neuroinflammation and brain energy metabolism in murine endotoxemia. Bioelectron. Med.8, 18. 10.1186/s42234-022-00101-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silverman, H. A. et al. Brain region-specific alterations in the gene expression of cytokines, immune cell markers and cholinergic system components during peripheral endotoxin-induced inflammation. Mol. Med.20, 601–611. 10.2119/molmed.2014.00147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Borst, K., Schwabenland, M. & Prinz, M. Microglia metabolism in health and disease. Neurochem. Int.10.1016/j.neuint.2018.11.006 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Borst, K., Dumas, A. A., Prinz, M. & Microglia Immune and non-immune functions. Immunity54, 2194–2208. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.09.014 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riazi, K. et al. Microglia-Dependent alteration of glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in the hippocampus during peripheral inflammation. J. Neurosci.35, 4942–4952. 10.1523/jneurosci.4485-14.2015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ho, Y. H. et al. Peripheral inflammation increases seizure susceptibility via the induction of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the hippocampus. J. Biomed. Sci.22, 46. 10.1186/s12929-015-0157-8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Othman, M. Z., Hassan, Z. & Has, A. T. C. Morris water maze: a versatile and pertinent tool for assessing Spatial learning and memory. Exp. Anim.71, 264–280 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reichman, W. E. Current Pharmacologic options for patients with alzheimer’s disease. Annals Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2, 1 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ellis, J. M. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia. J. Osteopath. Med.105, 145–158 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bickel, U., Thomsen, T., Fischer, J., Weber, W. & Kewitz, H. Galanthamine: pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and cholinesterase Inhibition in brain of mice. Neuropharmacology30, 447–454 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ballinger, E. C., Ananth, M., Talmage, D. A. & Role, L. W. Basal forebrain cholinergic circuits and signaling in cognition and cognitive decline. Neuron91, 1199–1218. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.006 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hampel, H. et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of alzheimer’s disease. Brain: J. Neurol.141, 1917–1933. 10.1093/brain/awy132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prvulovic, D., Hampel, H. & Pantel, J. Galantamine for alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol.6, 345–354. 10.1517/17425251003592137 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raskind, M. A., Peskind, E. R., Truyen, L., Kershaw, P. & Damaraju, C. V. The cognitive benefits of galantamine are sustained for at least 36 months: a long-term extension trial. Arch. Neurol.61, 252–256. 10.1001/archneur.61.2.252 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barnes, C. et al. Chronic treatment of old rats with donepezil or galantamine: effects on memory, hippocampal plasticity and nicotinic receptors. Neuroscience99, 17–23 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Geerts, H. Indicators of neuroprotection with galantamine. Brain Res. Bull.64, 519–524. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.11.002 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nordstrom, P., Religa, D., Wimo, A., Winblad, B. & Eriksdotter, M. The use of cholinesterase inhibitors and the risk of myocardial infarction and death: a nationwide cohort study in subjects with alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Heart J.34, 2585–2591. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht182 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin, Y. T., Wu, P. H., Chen, C. S., Yang, Y. H. & Yang, Y. H. Association between acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and risk of stroke in patients with dementia. Sci. Rep.6, 29266. 10.1038/srep29266 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tan, E. C. K. et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and risk of stroke and death in people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc.14, 944–951. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.011 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Secnik, J. et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with diabetes mellitus and dementia: an open-cohort study of ~ 23 000 patients from the Swedish dementia registry. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 8, e000833. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000833 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thompson, D. A. et al. Galantamine ameliorates experimental pancreatitis. Mol. Med.29, 149. 10.1186/s10020-023-00746-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mughrabi, I. T. et al. Galantamine attenuates autoinflammation in a mouse model of Familial mediterranean fever. Mol. Med.28, 148. 10.1186/s10020-022-00571-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nair, A. B. & Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic. Clin. Pharm.7, 27–31. 10.4103/0976-0105.177703 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rossignol, D. A. & Frye, R. E. The use of medications approved for alzheimer’s disease in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Front. Pead.2, 87. 10.3389/fped.2014.00087 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ghaleiha, A. et al. Galantamine efficacy and tolerability as an augmentative therapy in autistic children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford, England). 28, 677–685. 10.1177/0269881113508830 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fan, E. et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit. Care Med.42, 849–859 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morton, J. & Snider, T. A. Guidelines for collection and processing of lungs from aged mice for histological studies. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat. Dis.7, 1313676. 10.1080/20010001.2017.1313676 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.