Abstract

Building on our previous research on edaravone-derived bioactive small molecules, the precursors 2–5 were synthesized by condensation reactions between 4-{[(4-acetylphenyl)amino]methylidene}-5-methyl-2-phenylpyrazol-3-one (1) and a variety of organic hydrazines. Next, diversity-oriented S, N-heterocyclization of 2 was employed to access N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids bearing an azo phenyl fragment (6a,b) and N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone hybrids linked to an acrylate unit (7a,b). S, N-heterocyclization to access 6a,b was started by Williamson thioether synthesis between 2 and arene hydrazonoyl halides, while in 7a,b it was commenced via 1,4-thia-Michael addition between 2 and activated alkynes. The molecular structures of these uncommon hybrids were confirmed by instrumental analyses. Their cytotoxicity activity against osteosarcoma (Hos), non-small lung (A549), and colon carcinoma (HCT-116) cancer cell lines was tested via MTT bioassay using doxorubicin as a medical reference. The precursor 4 that bears a sulfonamide fragment is the sole molecule that is cytotoxic against all the tested cell lines, with an IC50 order of HCT-116 (7.3 ± 0.47) > A549 (20.4 ± 0.55) > Hos (39.9 ± 0.07 µM). The ELISA kit showed that 4 impacted the pRIPK3 kinase concentration in the A549 (2.97 ± 0.010 pg/mL), but less than DMSO-treated cells (2.93 ± 0.010 pg/mL). The best docking mode of 4with RIPK3 (7MX3) displayed two H-bonds and some hydrophobic interactions with a fitness energy of -116.704 kcal/mol, which is higher than the lead compound (-123.382 kcal/mol) that was documented in our earlier study8, validating the experimental results and suggesting 4 as a suitable candidate for structure modification and further biological investigations owing to the presence of the sulfonamide unit.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82656-5.

Keywords: Edaravone, N-phenylpyrazolone, N-benzylthiazole, N-benzyl-4-thiazolone, MTT, RIPK3

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Chemistry

Introduction

Diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) is a paradigm for generating structurally diverse natural product-like and/or drug-like small molecules as probes to examine their biological activities. The investigation of bioactivities may be useful in lead candidate identification for drug discovery and development or can facilitate the identification of novel molecules with the desired physiochemical features and drug-like nature1–4. Multi-step organic synthesis is an approach for synthesizing a molecular structure viamultiple chemical reactions to transform one set of starting materials into the desired final product5,6.

Pyrazolone nucleus is classically constructed by Knorr condensation reaction of β-ketoesters with hydrazines; the promoter base is usually organic like piperidine or inorganic like sodium hydride in refluxing alcoholic solvent (methanol or ethanol)7. As important synthons, traditional and advanced chemical modifications of pyrazolones produce a variety of highly functionalized derivatives with different features and applications, such as pharmaceuticals, dyes, and ligands8–11. Biologically speaking, researchers have reported several bioactive-based pyrazolones with a wide range of pharmacological properties viaDOS strategy, including anticancer, antiviral, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-tubercular, antihyperglycemic, antioxidant, lipid-lowering, central nervous system (CNS) agents, and enzyme inhibitors12.

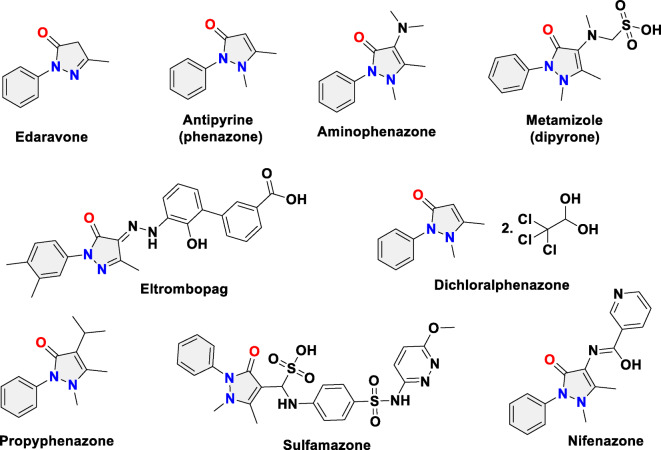

Importantly, the N-phenylpyrazolone nucleus has been found in several marketed drugs (Fig. 1), like edaravone, which is used as a free radical scavenger and neuroprotective agent with antioxidant activity to treat stroke and delay the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)13. Antipyrine and aminophenazone are employed as antipyretic and anti-inflammatory drugs14,15. Metamizole is medically used as a robust pain and fever reliever agent16. Eltrombopag is highly recommended for the treatment of severe aplastic anemia and chronic thrombocytopenia17,18. Dichloralphenazone is employed for the treatment of migraine and tension headaches as well as short-term insomnia12. Numerous investigational pyrazolone-derived small molecules have been considered as drug candidates, for instance, propyphenazone (analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory agent)19, sulfamazone (antibiotic, antipyretic sulfonamide)12, and nifenazone (analgesic)20. The aforementioned promising biological profile of pyrazolones makes them attractive targets for organic and medicinal chemists.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of marketed drugs and investigational drug candidates containing the N-phenylpyrazolone moiety.

Bioactive N-phenylpyrazole-thiazole hybrids are common in the literature21–24, while their N-phenylpyrazolone-thiazole counterparts are rare. In 2022, Sraa Abu-Melha successfully reported the synthesis of new antipyrine-thiazole hybrids with a phenoxyacetamide linkage. In comparison with chloramphenicol [MIC = 143 (S. aureus), 152 (B. subtilis) µg/mL], these hybrids showed impressive antibacterial activity against Gram-positive strains including S. aureus (MIC = 28–35 µg/mL) and B. subtilis(MIC = 44–51 µg/mL)25. In our recently published paper (2024)8, seven N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids were synthesized as receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) inhibitors. As a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-I signaling protein complex, phosphorylation of RIPK3 makes it active and able to trigger necroptosis and apoptosis viainteraction with RIPK1 and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL), forming a necrosome26,27. Hence, RIPK3 has a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis; therefore, it is an attractive targeted therapy and a dominant strategy for the treatment of cancer.

Continuing our research on bioactive small molecules based on N-phenylpyrazolones, a multi-step diversity-oriented S, N-heterocyclization strategy28,29 was implemented. This strategy involved varying the constructed heterocyclic ring (fragment diversity) and extending the structure to synthesize new N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids bearing an azo phenyl fragment and N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone hybrids linked to an acrylate unit. These hybrids, which are uncommon in the literature, were explored for their bioactivity as potential anticancer agents with RIPK3 inhibitory activity.

Results and discussion

Design strategy

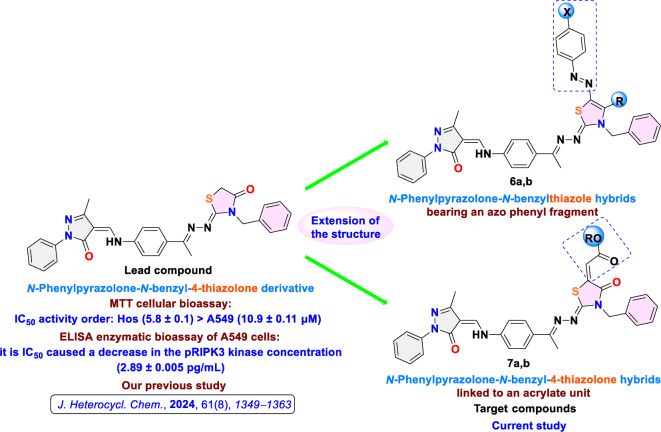

Motivated by the MTT-cytotoxicity [IC50 activity order: Hos (5.8 ± 0.1) > A549 (10.9 ± 0.11 µM)] and the ELISA-inhibitory activity against pRIPK3 kinase [A549 (2.89 ± 0.005 pg/mL)] of our previously published N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone derivative (lead compound)8, new N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids and N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone hybrids were designed according to the chemicals available in our feedstock, employing extension of the structure strategy (Fig. 2). Hence, the precursor chemicals 1–5 and the target compounds 6a–7b (as numbered in the chemical synthesis section) were sketched and in silico estimated to predict their molecular properties and druglike nature (Table 1) viathe free upgrade of the ADMETlab 3.0 online platform30,31. According to the Drug-Like Soft rule30, most of the designed molecules have shown the optimal range of the physicochemical descriptors. The size parameter is specified by the molecular weight (MW), which ranges from 319 to 686 g/mol (optimal: 100 ~ 600), therefore 6a, 6b, and quietly 7b violate the optimal MW.

Fig. 2.

Design strategy of target compounds.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties, lipophilicity, and drug-likeness nature of the target compounds 1–7b and lead molecule.

a nRot = number of Rotatable bonds; b nRing = number of Rings; c nHA = Hydrogen Bond Acceptor; d nHD = Hydrogen Bond Donor; e TPSA = Topological polar surface area; f logP = The partition coefficient between n-octanol and water, optimal 0–3; g logD = logP at physiological pH 7.4, optimal 1–3; h SAscore = Synthetic Accessibility score, high SAscore: ≥ 6, difficult to synthesize; low SAscore: < 6, easy to synthesize; i Lipinski (RO5) criteria range are: lipophilicity (logP) ≤ 5, MW ≤ 500, H-bond donors ≤ 5 and H-bond acceptors ≤ 10, Empirical decision: < 2 violations: excellent (green), ≥ 2 violations: poor (red); jPfizer criteria range are: logP > 3, TPSA < 75, compounds with a high log P (> 3) and low TPSA (< 75) are likely to be toxic, Empirical decision: two conditions satisfied: poor (red); otherwise: excellent (green);  = accepted,

= accepted,  = rejected30.

= rejected30.

The flexibility is defined by the number of rotatable bonds (nRot) that ranges from 4 to 10 (optimal: 0 ~ 11 ≠), thus all the compounds could be flexible, considering the number of rings that are between 3 and 7 (6aonly) (optimal: 0 ~ 6 ≠). The polarities of compounds are affected by the topological polar surface area (TPSA), which ranges from 61.77 to 117.72 Ų (optimal: 0 ~ 140 Ų). Consequently, the predictive molecules may have oral bioavailability according to Veber’s rule32 because they meet the criteria of nRot and TPSA. Lipophilicity serves as a significant indicator of permeability across the cell wall and is defined by the partition coefficients logP (optimal: 0–3) and logD (apparent partition coefficient at physiological pH = 7.4, optimal: 1–3) between water and n-octanol33. Compounds 1, 3, and 5 are correlated well with the ideal logP and logD range, while the remaining molecules are not. Worthy of note, all the predicted compounds are accepted by Lipinski and Pfizer metrics, except 6a and 6b, which violate the Lipinski filter in the molecular weight and logP parameters. Also, all the compounds have easy synthetic accessibility (SA) score. Subsequently, these theoretical findings encouraged us to complete our study by synthesizing the target molecules and testing them as potential anticancer agents.

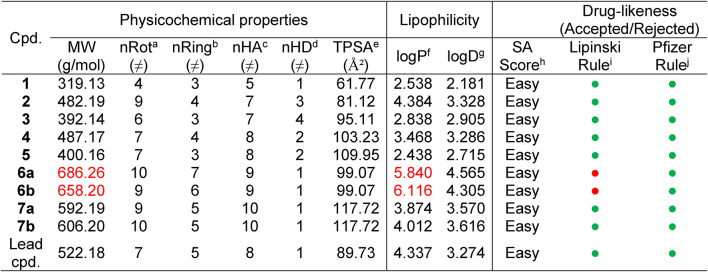

Organic synthesis

The multi-step diversity-oriented S, N-heterocyclization routes that are required to synthesize the chemical precursors 1–5 and the target compounds 6a–7b are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. The chemical structures of new compounds were confirmed by instrumental analyses, including FT-IR, NMR, and EI-MS. To do so, compounds 4-[[(4-acetylphenyl)amino]methylidene]−5-methyl-2-phenylpyrazol-3-one (1) and N-benzyl-2-(1-(4-(3-methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)-amino)phenyl)ethylid-ene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (2) are prepared according to our published protocol8. Like 2, the other precursors 3–5 were obtained in good to excellent yields by the same pathway through the straightforward acid-catalyzed condensation reaction between 1 and the corresponding organic hydrazine derivatives (thiosemicarbazide, p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide, and 2-cyanoacetohydrazide, respectively) (Fig. 3). In the 1H NMR spectrum of 3 (Fig. S9), a new NH is resonated at δH = 10.18 ppm, and the secondary amine NH is shielded from δH = 11.61 to 11.34 ppm due to the electron-donating nature of the thiosemicarbazide fragment. For the same reason, acetyl-CH3 and pyrazole-CH3 are shielded from δH = 2.60 and 2.36 ppm to 2.33 and 2.25 ppm, respectively, proving the preparation of thiosemicarbazone precursor 3. Also, the formation of 3was confirmed by the disappearance of the 13C resonance at δC = 196.37 ppm (C═O) and the generation of a new one at δC = 179.16 ppm, which exactly belongs to the C═S group (Fig. S10). In addition, the EI-MS stick diagram of 3 validated the structural formula by showing the molecular ion peak [M + 1]+ at m/z = 393.2 (50%) (Fig. S11). The mid-IR spectrum of 3 (Fig. S12) shows the primary thioamide NH2 as stretching two peaks at 3111 and 3281 cm−1.

Fig. 3.

Chemical synthesis of 1–5. Reagents and conditions: (a) ethyl acetoacetate (EAA, 10.0 g, 77 mmol), phenyl hydrazine (8.31 g, 77 mmol), EtOH (25 mL), reflux at 80 °C, 3 h, 83% yield; (b) edaravone (1.74 g, 10 mmol), 4-aminoacetophenone (1.35 g, 10 mmol), triethyl orthoformate (TEOF, 7.5 mL), acetic anhydride (Ac2O, 2.5 mL), reflux at 140 °C, 4 h, 85% yield; (c–d) 1 (0.64 g, 2 mmol), [(c) 4-benzyl-3-thiosemicarbazide (0.36 g, 2 mmol), (d), thiosemicarbazide (0.18 g, 2 mmol), (e) p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide (0.37 g, 2 mmol), and (f) 2-cyanoacetohydrazide (0.05 g, 2 mmol)] EtOH (20 mL), acetic acid (a few drops), reflux at 80 °C, 6 h, 85–92% yield.

Fig. 4.

Chemical synthesis of 1–5. Reagents and conditions: (a,b) 2 (0.96 g, 2 mmol), [(a) 2-bromo-1-phenyl-2-(phenyldiazenyl)ethan-1-one (0.60 g, 2 mmol), (b) 1-chloro-1-((4-chlorophenyl)diazenyl)propan-2-one (0.39 g, 2 mmol)], Et3N (5 drops), dioxane (20 mL), reflux at 105 °C, 4 h, 83 and 88% yield, respectively; (c,d) 2 (0.96 g, 2 mmol), [(c) DMAD/(d) DEAD (0.24/0.34 mL, 2 mmol)], MeOH/EtOH (50 mL), stirring at room temperature, 5 h, 81% yield/reflux at 80 °C, 3 h, 86% yield.

The key NMR signals of 4 prove the presence of a new CH3 group in the high-field region at δH= 2.13 ppm (Fig. S13) and the corresponding 13C chemical shift at δC= 21.72 ppm (Fig. S14), which precisely belongs to the methyl group of the tosyl fragment. Moreover, the 1H NMR spectrum of 4 displays a new NH group at δH = 10.49 ppm, confirming the success of the condensation reaction between 1 and p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide. In the downfield region, the NMR data of cyanoacetic hydrazone derivative 5 (Figs. S17, S18) show a new NH proton at δH = 11.00 ppm with more deshielding effect than the prior analogues 2–4 owing to the electron-withdrawing nature of the cyanoaceto unit. Moving to the upfield region, a new CH2 singlet signal is resonated at δH = 4.04 and δc = 25.44 ppm. The appearance of a new C═O at δC = 166.25 ppm and the retention of pyrazolone-C═O at δC= 165.33 ppm are also shown in the 13C NMR spectrum of 5, while the C=N stretching band is weakly vibrated at 2358 cm−1 in its IR spectrum (Fig. S20). Furthermore, the skeletal structure of 5 was validated by the MS spectrum that displays the molecular ion peak [M]+ at m/z = 400.52 (38%) (Fig. S19).

Afterwards, we focused on the preparation of the target compounds 6a–7b in this study. Triethylamine (Et3N)-promoted classical Williamson type thioether formation (C─S bond construction) of 2 by SN2 reaction with easily accessible arene hydrazonoyl halides as activated alkanes34, followed by N-heterocyclization via nucleophilic addition between NH and acetyl group, then elimination of H2O to obtain the corresponding N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids bearing the azo phenyl unit 6a, b in good yields (Fig. 4). At first glance, the 1H NMR data of 6a, b (Figs. S21, S25) show the disappearance of thiosemicarbazone NH groups and crowding of the aromatic region, confirming the successful generation of N-benzylthiazole derivatives 6a, b. Due to the electron-withdrawing nature of the azo phenyl fragment, the secondary NH group in the low-field region and the two methyl groups in the high-field region are slightly deshielded. For the same reason, the CH2 signal of the benzyl group in 6a, b is also deshielded, shifting from δH = 4.87 (2) to δH = 5.25 and δH = 5.38 ppm, respectively. Notably, it is more deshielded in 6b than 6a due to the presence of a Cl substituent on the phenyl ring. The FTIR spectra of 6a, b (Figs. S24, S28) display the newly formed N═N as medium stretching vibration bands at 1494 and 1499 cm–1, respectively35. Moreover, in the EI-MS spectra of 6a, b (Figs. S23, S27), the line created by the heaviest ion flowing via the instrument at m/z = 685.7 [M]+ (30%) and 659.8 [M]+ (50%), respectively, correlates with the molecular ion.

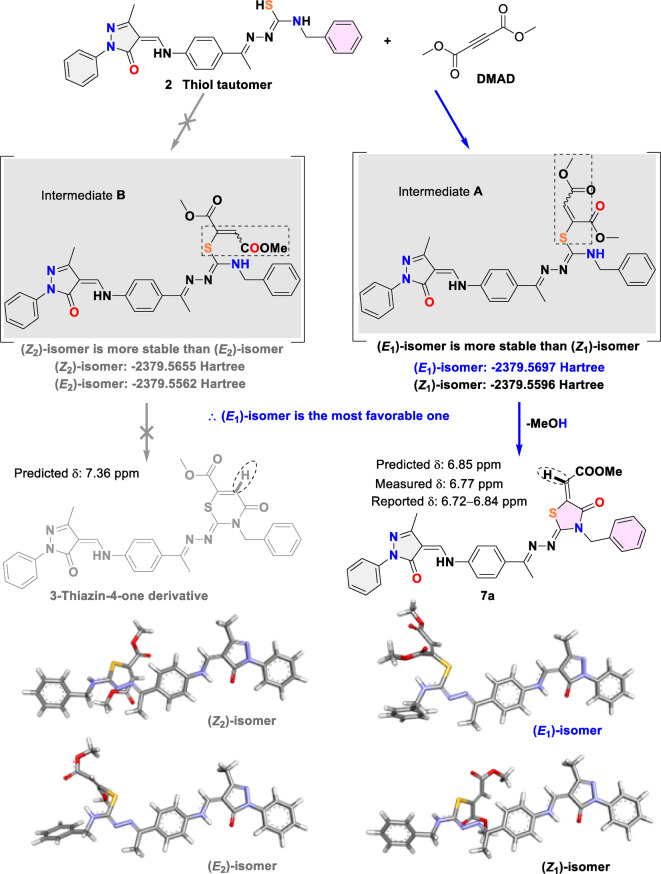

Among thioether synthesis protocols, 1,4-conjugate thia-Michael addition is an extremely useful technique and an atom-efficient chemical process to access thioethers36. As a synthetic application, regioselective 1,4-Michael addition between the neutral thiol 2 (Michael donor) and the activated alkyne [dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD) or diethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DEAD)] as a Michael acceptor, followed by N-heterocyclization afforded the N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone derivatives 7a, b in high yields (Fig. 4). The 1H NMR spectra of 7a, b (Figs. S29, S33) display the olefinic acrylate protons at δH = 6.77 and δH= 6.79 ppm, respectively37–40. The methoxy protons of 7a are resonated at δH = 3.76 ppm, while the ethoxy group of 7b appears as two signals at δH = 4.26 (q, CH2) and 1.25 (t, CH3) ppm. The acrylate C═O stretching bands in the mid-IR spectra of 7a, b (Figs. S32, S36) are absorbed around 1709 and 1721 cm−1, respectively. Additionally, the EI-MS data validated the chemical formulas of 7a, b (Figs. S31, S35) by showing the molecular ion [M]+ peaks at m/z = 593 (60%) and 606.6 (96%), respectively.

Mechanistically, the neutral nucleophilic thiol tautomer of 2 acts as a Michael donor and attacks the triple bond of the electrophilic acetylenic diester (DMAD/DEAD) as a Michael acceptor. This creates a Michael adduct (intermediate A) instead of B, which has a higher energy barrier based on the DFT calculation [(E1)-isomer: −2379.5697 Hartree, (Z2)-isomer: −2379.5655 Hartree, ∆E = 0.11 eV]. Next, intermediate A undergoes N-heterocyclization via a nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction between NH and the ester group to afford the corresponding five-membered 4-thiazolone derivatives 7a/7b instead of six-membered 3-thiazin-4-one derivatives (Fig. 5). Compounds 7a and 7bwere experimentally confirmed by 1H NMR, showing the presence of olefinic acrylate protons as aforementioned. Of note, the measured chemical shift of the prior protons (δH = 6.77–6.79 ppm) is matched very well with the reported data (δH= 6.72–6.84 ppm)37–40 and the predicted one by Mnova (δH = 6.85 ppm), while the CH resonance of the 3-thiazin-4-one system is predicted at δH = 7.36 ppm, proving the formation of 7a. The geometry optimization of intermediates A and Bwas carried out by Gaussian 09 software employing the DFT-B3LYP method at a 6-31G(d) basis set39.

Fig. 5.

The proposed mechanism for formation of 7a and the optimized geometries of intermediates A and B using the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) method.

Anticancer activity

In vitro cytotoxicity activity via cellular bioassay

The MTT cellular bioassay41 was used to screen the in vitro cytotoxicity activity of the prepared molecules 1–7 against three human cancer cell lines: osteosarcoma (Hos), non-small lung (A549), and colon carcinoma (HCT-116), using doxorubicin as a medical reference (Table 2). All the most potent compounds (4, 6a, and 7b) showed cytotoxicity activity against the Hos cell line, with IC50 values ranging from 39.9 to 60.1 µM. Fortunately, the chemical precursor 4 that bears a sulfonamide fragment is the sole molecule that is cytotoxic against all the tested cell lines, with an IC50 activity order of HCT-116 (7.3 ± 0.47) > A549 (20.4 ± 0.55) > Hos (39.9 ± 0.07 µM). Also, 4 (distance) is more effective than the lead compound8 against HCT-116 and vice versa against Hos and A549. Unfortunately, the remaining molecules, including the targets, are inactive towards the aforementioned cell lines.

Table 2.

In vitro cytotoxicity activity of the target compounds 1–7 against three human cancer cell lines (hos, A549, and HCT-116).

| Compounds | IC50 (µM)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hos | A549 | HCT-116 | |

| 1 | > 50 | > 50 | > 100 |

| 2 | > 100 | > 100 | > 50 |

| 3 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 4 | 39.9 ± 0.07 | 20.4 ± 0.55 | 7.3 ± 0.47 |

| 5 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 6a | 60.1 ± 0.06 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 6b | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 7a | > 50 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 7b | 47.6 ± 0.15 | > 100 | > 100 |

| Lead cpdb. | 5.8 ± 0.10 | 10.9 ± 0.11 | > 100 |

| Doxorubicinc | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.087 ± 0.09 | 2.2 ± 3.10 |

| DMSOd | – | – | – |

a IC50 (50% proliferation inhibitory concentration) values are the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments; bsee reference8; c positive control; d negative control.

In vitro pRIPK3 kinase concentration determination via ELISA technique

After that, following the procedure mentioned in the user manual of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit, the pRIPK3 kinase concentration in the A549 non-small lung cancer cell line8,42was determined. pRIPK3 is an important kinase of the MLKL (mixed lineage kinase domain-like) complex activation that prompts necroptotic cell death43. In comparison with other compounds, the promising cytotoxic results of 4 motivated us to study the cellular mechanism by measuring the concentration of pRIPK3 in the A549 underlying cell death induced by 4. Using DMSO as a negative control, after 24 h of exposure of A549 cells to the IC50 value of compound 4 (Table 2), variable effects on the level of pRIPK3 were observed. As tabulated in Table 3, compound 4(2.97 ± 0.010 pg/mL) had less of an effect on the amount of pRIPK3 than cells that had been treated with DMSO (2.93 ± 0.010 pg/mL) and was less effective than the lead compound8 (see Fig. 2). As a result, it will be tested as antibacterial due to the presence of a sulfonamide moiety39, and another rational design strategy based on molecular docking will be conducted in our lab, aiming to obtain a more effective inhibitor of pRIPK3.

Table 3.

Effect of the active molecule 4 on pRIPK3 kinase concentration in A549 cells.

| Compounds | Concentration (pg/mL)a |

|---|---|

| pRIPK3 in A549 | |

| 4 | 2.97 ± 0.010 |

| Lead cpdb. | 2.89 ± 0.005 |

| DMSOc | 2.93 ± 0.010 |

a pRIPK3 concentration (pg/mL) are the mean ± SD of two independent determinations after 24-hour; bsee reference8; c negative control.

Molecular docking

The iGEMDOCK software version 2.144,45 was used to simulate the binding mode of 4 within the active domain of the RIPK3 kinase (PDB ID: 7MX3). According to the best docking mode (Fig. 6a–c), N-phenylpyrazolone-sulfonamide hybrid 4 is interlocked with the binding pocket of 7MX3 by a fitness energy of −116.704 kcal/mol through a variety of intermolecular forces, including van der Waals, two conventional H-bonds, hydrophobic π-sigma, and hydrophobic π-alkyl interactions. Importantly, one H-bond is generated between the secondary sulfonamide as a hydrogen acceptor and the NH2 of aspartic acid (Asp160, 3.22 Å) as a hydrogen donor. The remaining H-bond is formed between the enamine-NH and the carboxyl group of the methionine amino acid (Met97, 2.90 Å). Also, the phenyl rings of 4 are stabilized within the active site by hydrophobic interactions including π-σ (Leu149) and π-alkyl (Ala48 and Arg309). In comparison with the lead compound (see Fig. 2), it is both practically and theoretically more effective than 4towards RIPK38, suggesting 4 as a suitable candidate for structure modification and further biological investigations owing to the presence of the sulfonamide unit (a new lead structure).

Fig. 6.

(a) Fitting into the active center, (b) 2D interaction, and (c) 3D interaction of 4 within the active site of RIPK3 kinase (PDB code: 7MX3). Compound 4 is displayed as cyan sticks. H-bonds are indicated by dashed lines in green. All images were produced with Discovery Studio Visualizer Client 2020 and are simple for clarity of presentation.

Materials and methods

Materials and instrumental techniques

See the supporting information file.

Chemical synthesis

Synthesis of compounds1 and 2.

See our previous study8.

General procedure for the synthesis of the chemical precursors 3–5

As a miniscale synthesis, a powder funnel was used to add 1 (0.64 g, 2 mmol) and organic hydrazine derivatives [thiosemicarbazide (0.18 g, 2 mmol), p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide (0.37 g, 2 mmol), and 2-cyanoacetohydrazide (0.05 g, 2 mmol)] into an oven-dry 100 mL round-bottomed flask charged with a magnetic stir bar. Ethanol (20 mL) containing a catalytic amount of acetic acid was subsequently added by the measuring cylinder. The flask was fitted with a water-jacketed condenser, and the reaction mixture was refluxed around 80 °C through a pre-heated oil bath for 6 h. During reflux, the desired products 3–5 were precipitated, filtrated off, washed with hot EtOH (3 × 10 mL), dried, and employed in the next steps without further purification.

2-(1-(4-((3-Methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)amino)phenyl)ethylidene)-hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (3)

Yellow amorphous solid; 85% yield; mp 260–262 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm−1) 3649 (N–H stretching), 3281, 3111 (NH2stretching), 1661 (C═O stretching), 1628 (C═N stretching) 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.34 (s, 1 H), 10.18 (s, 1 H), 8.59 (s, 1 H), 8.00–7.98 (m, 2 H), 7.96–7.94 (m, 2 H), 7.84–7.77 (m, 2 H), 7.55–7.53 (m, 1 H), 7.46–7.43 (m, 1 H), 7.41–7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.10 (ddt, J= 8.6, 7.3, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.33 (s, 3 H), 2.25 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 179.28, 165.29, 149.71, 147.66, 145.87, 139.87, 139.45, 134.95, 131.10, 130.57, 129.59, 129.35, 128.54, 127.04, 124.40, 121.23, 118.15, 117.93, 113.00, 109.34, 102.77, 27.16, 14.24, 13.25; EI-MS for C20H20N6OS m/z (%):393.2 [M + 1] + (50).

4-Methyl-N’-(1-(4-(((3-methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)amino)phenyl)-ethylidene)benzenesulfonohydrazide (4)

Yellow amorphous solid; 89% yield; mp 226–228 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm−1) 3221 (N–H stretching), 3061 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2925 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 1662 (C═O stretching), 1623 (C═N stretching), 1341, 1156 (O═S═O stretching ); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.30 (s, 1 H), 10.49 (s, 1 H), 8.55 (s, 1 H), 7.98–7.90 (m, 2 H), 7.82–7.74 (m, 2 H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 2 H), 7.37 (dd, J= 7.8, 3.4 Hz, 3 H), 7.38–7.30 (m, 1 H), 7.14–7.06 (m, 1 H), 2.33 (s, 3 H), 2.25 (s, 3 H), 2.13 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 165.27, 152.95, 149.63, 145.67, 143.94, 140.05, 139.47, 136.72, 134.62, 130.00, 129.52, 129.32, 128.86, 128.16, 127.79, 124.35, 118.14, 118.02, 102.88, 21.55, 14.65, 13.17; EI-MS for C26H25N5O3S m/z (%):487.2 [M] + (30).

2-Cyano-N’-(1-(4-(((3-methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)amino)phenyl)-ethylidene)acetohydrazide (5)

Yellow amorphous solid; 89% yield; mp 222–225 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm−1) 3427 (N–H stretching), 3064 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2910 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 2358 (C=N stretching), 1615 (C═O stretching); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.33 (s, 1 H), 11.00 (s, 1 H), 8.55 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.81 (dd, J = 14.3, 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.45 (p, J = 8.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.10 (t, J= 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.04 (s, 2 H), 2.27–2.24 (m, 6 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 166.25, 165.33, 153.91, 149.55, 148.94, 145.60, 140.02, 139.52, 135.04, 129.53, 129.29, 128.45, 128.14, 127.04, 124.33, 121.26, 118.17, 117.97, 116.75, 113.84, 109.41, 102.93, 100.00, 25.44, 14.27, 13.18; EI-MS for C22H20N6O2m/z (%):400.52 [M] + (38).

General procedure for the synthesis of N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids bearing an azo phenyl fragment (6a,b)

Setting up miniscale refluxing conditions, the chemical precursor 2 (0.96 g, 2 mmol) was transferred into an oven-dry 100 mL round-bottomed flask charged with a magnetic stir bar. Dioxane (20 mL) solution of the same equivalent (2 mmol) from arene hydrazonoyl halides: 2-bromo-1-phenyl-2-(phenyldiazenyl)ethan-1-one (0.60 g), 1-chloro-1-((4-chlorophenyl)diazenyl)propan-2-one (0.39 g) was added individually. The reaction mixture was subsequently mediated by a catalytic amount of Et3N (5 drops) and refluxed at 105 °C through a pre-heated oil bath for 4 h. During reflux, the desired products (6a,b) were formed, and the work-up procedures were implemented for each case.

4-(((4-(1-((3-Benzyl-4-phenyl-5-(phenyldiazenyl)thiazol-2(3 H)-ylidene)hydrazineylidene)ethyl)phenyl)-amino)methylene)−5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3 H-pyrazol-3-one (6a)

Deep red amorphous solid; 83% yield; mp 177–180 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm-1) 3410 (N–H stretching), 3066 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2921 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 1667 (C═O stretching), 1604 (C═N stretching), 1494 (N═N stretching); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.39 (s, 1 H), 8.35 (s, 1 H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.98 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.94 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.89–7.78 (m, 3 H), 7.63 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.59–7.53 (m, 2 H), 7.49 (dd, J = 16.0, 9.2 Hz, 3 H), 7.41 (dt, J = 16.1, 7.7 Hz, 3 H), 7.36–7.31 (m, 1 H), 7.25 (dt, J = 27.3, 7.6 Hz, 3 H), 7.12 (t, J= 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 5.25 (s, 2 H), 2.33 (s, 3 H), 2.28 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 153.89, 137.92, 130.83, 130.60, 129.53, 129.34, 129.16, 129.10, 128.92, 128.84, 127.10, 122.66, 117.91, 37.90, 13.04; EI-MS for C41H34N8OS m/z (%): 685.7 [M]+ (30).

4-(((4-(1-((3-Benzyl-5-((4-chlorophenyl)diazenyl)−4-methylthiazol-2(3 H)-ylidene)hydrazineylidene)ethyl)-phenyl)amino)methylene)−5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3 H-pyrazol-3-one (6b)

Deep brown amorphous solid; 88% yield; mp 209–212 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm-1) 3221 (N–H stretching), 3066 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2921 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 1658 (C═O stretching), 1628 (C═N stretching), 1499 (N═N stretching) ;1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.36 (s, 1 H), 8.57 (s, 1 H), 8.03–7.93 (m, 3 H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.72–7.66 (m, 1 H), 7.58 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.52–7.46 (m, 1 H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 3 H), 7.39–7.34 (m, 3 H), 7.36–7.26 (m, 3 H), 7.11 (td, J = 7.4, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.38 (s, 2 H), 2.66 (s, 3 H), 2.32 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 3 H), 2.27 (d, J= 4.4 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 165.34, 164.28, 158.73, 151.41, 149.52, 148.55, 145.61, 145.38, 139.96, 139.52, 136.57, 135.10, 133.74, 133.51, 129.84, 129.37, 129.29, 128.70, 128.54, 128.14, 127.74, 127.56, 127.25, 124.35, 123.71, 118.20, 117.94, 102.96, 48.45, 14.97, 13.19, 12.70; EI-MS for C36H31ClN8OS m/z (%): 659.8 [M] + (50).

General procedure for the synthesis of N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone hybrids linked to an acrylate unit (7a,b)

To an oven-dry 100 mL round-bottomed flask charged with a magnetic stir bar, 0.96 g of N-benzylthiosemicarbazone 2 (2 mmol) was added, followed by MeOH/EtOH (50 mL), then 2 mmol of DMAD/DEAD (0.24/0.34 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h in the case of DMAD or refluxed at 80 °C for three hours in the case of DEAD, then the formed solid products were collected, washed with hot MeOH/EtOH, and dried to afford 7a, b in their pure state (TLC).

Methyl 2-(3-benzyl-2-((1-(4-(((3-methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)amino)-phenyl)ethylidene)hydrazineylidene)−4-oxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)acetate (7a)

Yellow amorphous solid; 81% yield; mp 222–225 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm-1) 3432 (N–H stretching), 3070 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2905 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 1709, 1671, and 1632 (3 C═O stretching), 1590 (C═N stretching); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.34 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1 H), 8.57 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.96 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.90 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.81 (s, 1 H), 7.63 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.51–7.43 (m, 2 H), 7.41–7.32 (m, 5 H), 7.29 (s, 2 H), 7.11 (s, 1 H), 6.77 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.08–5.01 (m, 2 H), 3.76 (d, J= 3.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.41 (s, 3 H), 2.27 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 165.27, 161.33, 149.64, 147.77, 145.48, 141.89, 141.07, 139.49, 136.16, 134.18, 129.59, 129.32, 129.13, 128.59, 127.11, 124.36, 121.30, 118.15, 109.40, 103.20, 53.07, 46.92, 15.29, 13.21; EI-MS for C32H28N6O4S m/z (%): 593 [M]+ (60).

Ethyl 2-(3-benzyl-2-((1-(4-(((3-methyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-1,5-dihydro-4 H-pyrazol-4-ylidene)methyl)amino)-phenyl)ethylidene)hydrazineylidene)−4-oxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)acetate (7b)

Yellow amorphous solid; 86% yield; mp 164–167 °C; mid FT-IR (KBr, ν/cm-1) 3397 (N–H stretching), 3058 (aromatic C–H stretching), 2968 (aliphatic C–H stretching), 1721, 1698, and 1671 (3 C═O stretching), 1604 (C═N stretching); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.40 (s, 1 H), 8.62 (s, 1 H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4 H), 7.39 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.6, 5.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.14 (t, J= 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 6.80 (s, 1 H), 5.08 (s, 2 H), 4.26 (q, 2 H), 2.45 (s, 3 H), 2.29 (s, 3 H), 1.25 (t, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 164.99, 161.50, 158.84, 156.45, 145.66, 142.25, 129.12, 128.89, 128.40, 128.29, 117.95, 108.38, 106.85, 59.36, 52.05, 15.09, 14.15; EI-MS for C33H30N6O4S m/z (%): 606.6 [M]+ (96).

Anticancer activity

In vitro 2D model (monolayer) cytotoxicity activity via cellular MTT bioassay.

In vitro pRIPK3 kinase concentration determination via ELISA technique.

In silico molecular docking

DFT calculations

See the supporting information file.

Conclusions

In summary, two thiosemicarbazones (2 and 3) and another two chemical precursors (4 and 5) were successfully prepared by acid-catalyzed condensation reactions between 1 and the corresponding organic hydrazine derivatives. After that, thiazolation via the diversity-oriented S, N-heterocyclization strategy of benzylthiosemicarbazone 2 was conducted to access new structurally extended compounds, including N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzylthiazole hybrids bearing an azo phenyl fragment (6a,b) and N-phenylpyrazolone-N-benzyl-4-thiazolone hybrids linked to an acrylate unit (7a,b). S, N-heterocyclization to access 6a,b was done via Williamson thioether formation between 2 and arene hydrazonoyl halides, then nucleophilic addition between NH and acetyl group, while 7a,b were created by 1,4-thia-Michael addition between 2 and activated alkynes, followed by nucleophilic acyl substitution between NH and ester groups. The formation of 7a and 7b was supported by DFT. Their cytotoxicity activity exhibited that precursor 4 that bears a sulfonamide fragment is the sole molecule that is cytotoxic against all the tested cell lines, with an IC50 order of HCT-116 (7.3 ± 0.47) > A549 (20.4 ± 0.55) > Hos (39.9 ± 0.07 µM). It is worth noting that 4 is more potent than the lead compound (IC50 > 100 µM) towards the colon cancer cell line (HCT-116). Also, ELISA kit showed that 4 impacted the pRIPK3 kinase concentration in the A549 (2.97 ± 0.010 pg/mL), but less than DMSO-treated cells (2.93 ± 0.010 pg/mL). The best docking mode of 4with RIPK3 (7MX3) displayed two H-bonds and some hydrophobic interactions with a fitness energy of −116.704 kcal/mol, which is higher than the lead compound (−123.382kcal/mol) that was documented in our earlier study8, validating the biological experimental findings and suggesting 4 as a suitable candidate for further screening against colon cancer cell lines or for antimicrobial investigation owing to the sulfonamide unit. Subsequently, a rational design based on molecular docking predictions will be implemented in our group to synthesize new N-phenylpyrazolone-thiazole hybrids that could be multi-target therapeutics.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express deep thanks to the Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Egypt, for the equipment and chemical materials.

Author contributions

“Essam Eliwa wrote the main manuscript; Abdullah A. Ahmed and Mahmoud M. Abd El-All did the organic synthesis work; Salwa M. El-Hallouty and Zeinab A. Elshahid did the biological evaluation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Data availability

Spectroscopic NMR and IR, as well as spectrometry mass data that support the findings of our study, are provided in the supplementary information file.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error, where two schemes and their in-text citations were omitted. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/25/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-30018-0

References

- 1.Hudson, L. et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis encoded by deoxyoligonucleotides. Nat. Commun.14, 4930 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spandl, R. J., Díaz-Gavilán, M., O’Connell, K. M. G., Thomas, G. L. & Spring, D. R. Diversity-oriented synthesis. Chem. Rec. 8, 129–142 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galloway, W. R. J. D., Isidro-Llobet, A. & Spring, D. R. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules. Nat. Commun.1, 80 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenci, E., Innocenti, R., Menchi, G. & Trabocchi, A. Diversity-oriented synthesis and chemoinformatic analysis of the Molecular Diversity of sp3-Rich Morpholine Peptidomimetics. Front. Chem.6, 522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phiri, C. M. & Saxena, A. Multi-step organic synthesis: A review of some synthetic routes and applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2535, 040007 (2023).

- 6.Mechelke, M. F. Advanced Organic Chemistry Laboratory: a Multistep synthesis toward the Preparation of a small Library of Antituberculosis compounds. J. Chem. Educ.99, 3265–3271 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamama, S., El-Gohary, W. G., Kuhnert, H., Zoorob, H. & N. & Chemistry of Pyrazolinones and their applications. Curr. Org. Chem.16, 373–399 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed, A. A., El-All, M. M. A., El‐Hallouty, S. M., Elshahid, Z. A. & Eliwa, E. M. New edaravone analogs incorporated with N ‐benzylthiazole moiety: multistep chemical synthesis, in vitro cytotoxicity with pRIPK3 inhibitory activities, and molecular docking. J. Heterocycl. Chem.61, 1349–1363 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu, Y., Shen, M., Zhang, X. & Fan, X. Selective synthesis of Pyrazolo[1,2- a ]pyrazolones and 2-Acylindoles via Rh(III)-Catalyzed tunable redox-neutral coupling of 1-Phenylpyrazolidinones with Alkynyl Cyclobutanols. Org. Lett.22, 4697–4702 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie, X., Xiang, L., Peng, C. & Han, B. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of Spiropyrazolones and their application in Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Rec. 19, 2209–2235 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casas, J., Garcia-Tasende, M., Sanchez, A., Sordo, J. & Touceda, A. Coordination modes of 5-pyrazolones: a solid-state overview. Coord. Chem. Rev.251, 1561–1589 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao, Z. et al. Pyrazolone structural motif in medicinal chemistry: retrospect and prospect. Eur. J. Med. Chem.186, 111893 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapchak, P. A. A critical assessment of edaravone acute ischemic stroke efficacy trials: is edaravone an effective neuroprotective therapy? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 11, 1753–1763 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Küçükgüzel, Ş. G. & Şenkardeş, S. Recent advances in bioactive pyrazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem.97, 786–815 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meiattini, F., Prencipe, L., Bardelli, F., Giannini, G. & Tarli, P. The 4-hydroxybenzoate/4-aminophenazone chromogenic system used in the enzymic determination of serum cholesterol. Clin. Chem.24, 2161–2165 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kötter, T. et al. Metamizole-Associated adverse events: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLoS One. 10, e0122918 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desmond, R., Townsley, D. M., Dunbar, C. & Young, N. S. Eltrombopag in Aplastic Anemia. Semin Hematol.52, 31–37 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Townsley, D. M. et al. Eltrombopag added to Standard Immunosuppression for aplastic Anemia. N Engl. J. Med.376, 1540–1550 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akyel, A., Alsancak, Y., Yayla, Ç., Şahinarslan, A. & Özdemir, M. Acute inferior myocardial infarction with low atrial rhythm due to propyphenazone: Kounis syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol.148, 352–353 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart, F. D. & Boardman, P. L. Trial of Nifenazone (‘Thylin’). BMJ1, 1553–1554 (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashour, G. R. S. et al. Synthesis, modeling, and biological studies of new thiazole-pyrazole analogues as anticancer agents. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.27, 101669 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salem, M. E., Mahrous, E. M., Ragab, E. A., Nafie, M. S. & Dawood, K. M. Synthesis of novel mono- and bis-pyrazolylthiazole derivatives as anti-liver cancer agents through EGFR/HER2 target inhibition. BMC Chem.17, 51 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandurkar, Y., Shinde, A., Bhoye, M. R., Jagadale, S. & Mhaske, P. C. Synthesis and Biological Screening of New 2-(5-Aryl-1-phenyl-1 H -pyrazol-3-yl)-4-aryl thiazole derivatives as potential Antimicrobial agents. ACS Omega. 8, 8743–8754 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metwally, N. H. & El-Desoky, E. A. Novel Thiopyrano[2,3- d ]thiazole-pyrazole hybrids as potential Nonsulfonamide Human Carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitors: design, synthesis, and biochemical studies. ACS Omega. 8, 5571–5592 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abu-Melha, S. Molecular modeling and docking studies of new antimicrobial antipyrine-thiazole hybrids. Arab. J. Chem.15, 103898 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martens, S., Hofmans, S., Declercq, W., Augustyns, K. & Vandenabeele, P. Inhibitors targeting RIPK1/RIPK3: old and new drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.41, 209–224 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriwaki, K. & Chan, F. K. M. Regulation of RIPK3- and RHIM-dependent necroptosis by the Proteasome. J. Biol. Chem.291, 5948–5959 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivas, M. & Gevorgyan, V. Advances in selected heterocyclization methods. Synlett34, 1554–1562 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkateswarlu, V. et al. Direct N-heterocyclization of hydrazines to access styrylated pyrazoles: synthesis of 1,3,5-trisubstituted pyrazoles and dihydropyrazoles. RSC Adv.8, 26523–26527 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong, J. et al. ADMETlab: a platform for systematic ADMET evaluation based on a comprehensively collected ADMET database. J. Cheminform. 10, 29 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eliwa, E. M. et al. Cu(II)-Promoted the Chemical synthesis of New azines-based Naphthalene Scaffold as in vitro potent mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors and evaluation of their antiproliferative activity. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.43, 6018–6045 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem.45, 2615–2623 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, R. R. et al. Integrating the impact of Lipophilicity on potency and pharmacokinetic parameters enables the Use of Diverse Chemical Space during small Molecule Drug optimization. J. Med. Chem.63, 12156–12170 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arafeh, M. M., Moghadam, E. S., Adham, S. A. I., Stoll, R. & Abdel-Jalil, R. J. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity study of Novel 2-(Aryldiazenyl)-3-methyl-1H-benzo[g]indole derivatives. Molecules26, 4240 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartošová, A., Blinová, L., Sirotiak, M. & Michalíková, A. Usage of FTIR-ATR as non-destructive analysis of selected toxic dyes. Res. Pap Fac. Mater. Sci. Technol. Slovak Univ. Technol.25, 103–111 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wadhwa, P., Kharbanda, A. & Sharma, A. Thia-Michael Addition: an emerging strategy in Organic synthesis. Asian J. Org. Chem.7, 634–661 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yakaiah, S., Sagar Vijay Kumar, P., Baby Rani, P., Durga Prasad, K. & Aparna, P. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel pyrazolo-oxothiazolidine derivatives as antiproliferative agents against human lung cancer cell line A549. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.28, 630–636 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asghari, S., Pourshab, M. & Mohseni, M. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of novel indole-hydrazono thiazolidinones. Monatshefte für Chemie - Chem. Mon. 149, 2327–2336 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdou, M. M. et al. Tailoring of novel morpholine-sulphonamide linked thiazole moieties as dual targeting DHFR/DNA gyrase inhibitors: synthesis, antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities, and DFT with molecular modelling studies. New. J. Chem.48, 9149–9162 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elgammal, W. E. et al. Thiazolation of phenylthiosemicarbazone to access new thiazoles: anticancer activity and molecular docking. Future Med. Chem.16, 1219–1237 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boulis, A. G. et al. Diverse bioactive metabolites from Penicillium sp. MMA derived from the red sea: structure identification and biological activity studies. Arch. Microbiol.202, 1985–1996 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hornbeck, V. P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Curr. Protoc. Immunol.110, 211–2123 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moriwaki, K., Chan, F. & K.-M RIP3: a molecular switch for necrosis and inflammation. Genes Dev.27, 1640–1649 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu, K. C., Chen, Y. F., Lin, S. R. & Yang, J. M. iGEMDOCK: a graphical environment of enhancing GEMDOCK using pharmacological interactions and post-screening analysis. BMC Bioinform.12, S33 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eliwa, E. M. et al. Metal-free domino amination-knoevenagel condensation approach to access new coumarins as potent nanomolar inhibitors of VEGFR-2 and EGFR. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev.14, 578–599 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Spectroscopic NMR and IR, as well as spectrometry mass data that support the findings of our study, are provided in the supplementary information file.