Abstract

Background

Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm with variable epithelial differentiation, with a propensity to occur in young adults. The pathognomonic t(X;18) chromosomal translocation and subsequent development of the SS18:SSX fusion oncogenes are the driver of the distinct genomic features.

Aim

To study the Clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular features of SS occurring in all the organ systems.

Method

A retrospective observational study was conducted over a period of 4 years at a tertiary cancer centre.

Result

One hundred eight patients were included in the study based on exclusion and inclusion criteria. The median age of patients was 30.5 years and mean tumor diameter was 10.5 cm. Most common site was lower limb followed by lung, and arm. 50 patients underwent surgery and 49 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. 87 patients (81%) presented with monophasic subtype and 21 (19%) with biphasic subtype.

The most helpful immunohistochemical markers for diagnosis and exclusion of close differentials were TLE1, EMA, Pancytokeratin, S-100, BCL2, and CD99. Molecular diagnostic confirmation was attained in 10 out of 15 patients. On median follow-up of 7.58 months, mean 4-year overall survival of the patients was 91.39%.

Conclusion

Meticulous pathologic evaluation and awareness of the typical and atypical histology of SS along with the apt application of immunohistochemical marker such as TLE1 and/or cytogenetics (SYT translocation) assist in precise recognition of this not so common entity. The main therapeutic modality is surgical excision with negative margins, with the addition of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy based on patient and tumour characteristics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-14862-x.

Keywords: Synovial sarcoma, SS18:SSX translocation, Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, Outcome

Introduction

Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a soft tissue sarcoma that primarily affects teenagers and young adults, making about 5–10% of all soft tissue sarcomas and is ranked as the fourth among soft tissue sarcomas after undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, liposarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. SS is thought to be caused by a chromosomal aberration called t (x; 18) (p11.2; q11.2), which leads to the production of SS18-SSX fusion oncogenes. Over 90% of SS cases have this chromosomal abnormality, which is thought to be the root cause of this entity [1–3].

The vast majority (70%) of SSs develop in the deep soft tissues of the lower and upper extremities, frequently in juxta-articular sites. Approximately 15% occur in the trunk, and 7% in the head and neck region. Unusual locations of involvement include male and female external and internal reproductive organs, kidney, adrenal gland, retroperitoneum, stomach, small bowel, lung, heart, mediastinum, bone, Central nervous system (CNS), and peripheral nerve [1].

Histologically, this tumor has two major subtypes: the monophasic and the biphasic type [1].

However, morphological variations are noted commonly in this group of tumors. Immunohistochemistry and molecular studies are helpful in case of diagnostic dilemma.

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) methods are used to test the chromosome anomaly which causes SS. Practical issues, such as cost, specialised equipment, and availability, limit the application of these strategies.

Classic treatment of SS is wide local excision with negative margins, chemotherapy or combinations [2].

There is currently very limited literature on clinical and pathological data as well as survival outcomes, for individuals with SS in India. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis of clinicopathological features, immunohistochemical expressions and survival outcomes of these group of patients at our institute, which is a tertiary care cancer centre in northern India.

Materials and methods

This a retrospective observational study of 108 synovial sarcoma cases diagnosed during the period of January 2019 to January 2023. The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC, MPMMCC & HBCH, Project no. 11000639). The inclusion criteria were (1) All the patients histopathologically diagnosed as synovial sarcoma, irrespective of age and gender. (2) All cases whose biopsy/excision tissue in the form of paraffin blocks, hematoxylin & eosin stained slides and immunohistochemistry slides were available for review.

Cases in which biopsy was inadequate or not representative of the lesion and cases for which the paraffin blocks or slides were not available for review were excluded from the study.

Slides of all the cases meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved from the pathology department archives. Details regarding the clinic-demographic parameters, radiological investigations, treatment received, relapse/recurrence and survival data were collected from the patient’s electronic medical records.

Histomorphological details and immunohistochemical features, such as the type of tumor, positivity, and negativity of IHC markers were studied. Molecular data, if available were collected for analysis.

Progression-free Survival (PFS) and Overall survival (OS) were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier estimate.

Results

The study includes 108 cases of synovial sarcoma with age ranging from 6 years to 70 years and median age being 30.5 years. 61 (56.5%) cases were male while females were 47 (43.5%). Mean tumor size was 10.5 cm and median tumor size was 12 cm. Various age and size ranges are listed in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic details

| Age group (years) | N (%) | Median age: 30.5 years (6-70 years) | |

| 0-9 | 4 (3.7%) | ||

| 10-19 | 22 (20.3%) | ||

| 20-29 | 26 (24%) | ||

| 30-39 | 19 (17.6%) | ||

| 40-49 | 18 (16.6%) | ||

| 50-59 | 12 (11.1%) | ||

| 60-69 | 6 (5.5%) | ||

| 70-79 | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Size range (cm) | N (%) |

Median size: 12 cm Mean size: 10.5 cm |

|

| <5 | 17 (15.7%) | ||

| 5-10 | 33 (30.5%) | ||

| >10 | 58 (53.7%) | ||

| Tumor site | N (%) | Tumor site | N (%) |

| Lower extremity | 44 (40%) | Pelvis | 11 (10.1%) |

| 21 | Gluteal | 2 | |

| Thigh | 6 | Groin | 2 |

| Popliteal fossa | 6 | Hip | 2 |

| Foot | 6 | Inguinal region | 3 |

| Leg | 5 | Iliac fossa | 1 |

| Knee | Pelvis, NOS | 1 | |

| Upper extremity | 23 (21%) | Head and neck | 6 (5.5%) |

| Arm | 8 | Preauricular | 1 |

| Forearm | 7 | Supraglottis | 1 |

| Axilla | 3 | Epiglottis | 1 |

| Elbow | 3 | Orbit | 1 |

| Hand | 1 | Occipital region | 1 |

| Shoulder | 1 | Submandibular | 1 |

| Thorax | 17 (16%) | Abdominal wall | 3 (2.7%) |

| Lung | 10 | Retroperitoneum | 1 (0.9%) |

| Chest/chest wall | 3 | ||

| 1 | Back | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Hemithorax | 1 | ||

| Ribs | 1 | Brain | 1 (0.9%) |

| Mediastinum | 1 | ||

| Pleura | Paratesticular soft tissue | 1 (0.9%) | |

Most common site affected was lower extremity (44 cases) followed by upper extremity, thorax, pelvis, head and neck, abdomen, trunk/back, brain and paratesticular soft tissue. In head and neck, some rare sites affected were Larynx (2 cases), orbit (1 case), occipital region 1 (case), Submandibular region (1 case) (Table 1).

Out of 108 cases, 78 cases were of monophasic type, 21 cases biphasic type and 9 cases were poorly differentiated type. The monophasic spindle cell variant was identified in 68 cases, whereas the epithelioid subtype was observed in 10 cases. TLE1 was the most common positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) marker and showed positivity in 78 out of 81 cases (96.2%). Other common positive IHC markers were CD56 (47/49 cases, 95.9%), CD99 (58/66 cases, 87%), BCL2 (29/35 cases, 82.8%), EMA (34/60 cases 56.6%), and PanCK (28/55 cases 51%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Histological, Immunohistochemistry and Molecular features

| Histologic type | N (%) |

| Monophasic | 78 (73%) |

| Biphasic | 21 (19%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 09 (8%) |

| IHC marker | N (%) |

| TLE1 | 78/81 (96.2%) |

| CD56 | 47/49 (95.9%) |

| CD99 | 58/66 (87%) |

| BCL2 | 29/35 (82.8%) |

| EMA | 34/60 (56.6%) |

| CK | 28/55 (51%) |

| S-100 | 5/75 (6.6%) |

| SSX: SS18 | 5/5 (100%) |

| CD34 | 2/41 (0.048%) |

| SS18:SSX fusion | N (%) |

| Detected | 10/15 (67%) |

| Not detected | 3/15 (20%) |

| Uninterpretable | 2/15 (13%) |

CD34 was applied in 41 cases and showed focally positivity in 2 cases (0.048%).

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis was established using a combination of immunohistochemical markers, including TLE1, CD56, CD99, BCL2, and EMA. TLE1, CD56, CD99, EMA, CK, and BCL2 were co-expressed in one case. A combination of TLE1, CD99, EMA, and BCL2 was positive in seven cases, while TLE1, CD56, and EMA were detected together in ten cases. Concurrent expression of TLE1 and CD56 was observed in thirty-five cases. The marker set TLE1, CD56, and CD99 was positive in fifteen cases, and the combination of TLE1, CD56, CD99, and BCL2 was identified in three cases.

Retrospectively, SS18: SSX immunohistochemistry marker was done in 5 cases and all of them were positive (100%). Antibody clone used was RBT-SS18-SSX. The SS18-SSX antibody is a rabbit monoclonal antibody obtained from cell culture supernatant, which is subsequently concentrated, dialyzed, and filter-sterilized. It is formulated in a buffer at pH 7.5 containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) and sodium azide as a preservative. The antibody demonstrates nuclear expression, with a known case of synovial sarcoma harboring the SS18-SSX fusion used as the positive control.

Some of the negative markers include SMA, Desmin, h-Caldesmon, NKX2.2, STAT6, FLI1, C-KIT, DOG1, Beta-catenin, SATB2.

Out of 108 cases, molecular testing was done in 15 cases. SS18:SSX fusion was detected in 10 out of 15 cases. 5 cases were tested positive by RT-PCR while other 5 cases were tested positive by FISH. In two cases, test was uninterpretable while in three cases, it was negative (Table 2).

Two cases exhibiting poorly differentiated morphology tested positive for the SS18:SSX fusion by FISH.

Out of 108 cases, 21 cases (19.4%) presented back to us with local recurrence and 41 cases (38%) reported with metastasis (on presentation or during follow-up). Most common site of metastasis was lung (34/41 cases) followed by bone (4/41 cases), lymph node (6/41 cases) and Liver (single case) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment and follow-up

| Local recurrence | N (%) |

| Yes | 21 (19.4%) |

| No | 87 (80.5%) |

| Metastasis | N (%) |

| Yes | 41 (38%) |

| No | 67 (62%) |

| Site of metastasis | N (%) |

| Lung | 34 (31.4%) |

| Lymph node | 6 (5.55%) |

| Bone | 4 (37%) |

| Liver | 1 (0.92%) |

| Treatment | N (%) |

| Surgery + CT | 23 (21.2%) |

| Surgery+CT+RT | 18 (16.6%) |

| CT | 18 (16.6%) |

| CT+RT | 8 (7.4%) |

| Surgery+RT | 6 (5.5%) |

| RT | 3 (2.7%) |

| Defaulted | 32 (29.6%) |

Surgery along with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was the common treatment modality. 23 cases had surgery with chemotherapy, and 6 cases had surgery with radiotherapy. 18 cases received only chemotherapy, 8 cases received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy and 3 cases received only radiotherapy in the form of External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (12GYy/2#). Most common chemotherapy regimen used included Ifosfamide and Adriamycin. In some case Pazopanib 400 mg was also given (Table 3).

Survival analysis

The median follow-up (in months) of the patients was approximately 7.58 months, with the minimum and maximum duration of follow-up being approximately 0 months and 49.74 months, respectively.

Out of 108 patients, there were 61 patients where either local recurrence or metstasis had occurred. The mean 4-year disease-free survival of the patients was 67.04 ± 4.3%. The median 2-year progression-free survival of the patients was 70.11 ± 4.5%. Out of 108 patients, 7 patients died of the disease. The mean 4-year overall survival of the patients is 93.58 ± 4.2%. The median 2-year overall survival of the patients is 94.9 ± 2.6% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meier curve depicting PFS and OS

PFS and OS were correlated with age, gender, tumor size, histological subtypes, local recurrence, and metastasis.

On follow up, 20 out of 47 female patients and 41 out of 61 male patients presented with local recurrence or metastasis. On performing log-rank test, the p-value obtained was 0.031 (< 0.05) which implies that significant differences were found in the progression-free survival rate between the two genders.

Out of all 7 deaths, 4 patients were female and 3 were male. On performing log-rank test, the p-value is obtained as 0.36 (> 0.05) which implies that no significant differences were found in the overall survival rate between the two genders.

Out of 17 patients with tumor size < 5 cm, 10 presented with disease progression (local recurrence or metastasis). Out of 33 patients with tumor size ranging 5–10 cm, 19 had disease progression. Out of 58 patients with tumor size > 10 cm, 33 had disease progression. However, on performing log-rank test, the p-value is obtained as 0.41 (> 0.05) which implies that no significant differences were found in the progression-free survival rate between the three tumor size ranges. Similarly, 1 out of 17 patients with tumor size < 5 cm, 3 out of 33 patients with tumor size 5–10 cm, and 3 out of 58 patients with tumorm size > 10 cm died of disease. On performing log-rank test, the p-value is obtained as 0.88 (> 0.05) which implies that no significant differences were found in the overall survival rate between the three tumor size ranges.

In the same way, no significant correlation was found between various histologic subtypes, age, local recurrence and metastasis with the survival rates.

Discussion

World health organization (WHO) has categorized synovial sarcoma under tumors of uncertain differentiation and has defined synovial sarcoma as a monomorphic blue spindle cell sarcoma showing variable epithelial differentiation and characterized by a specific SS18-SSX1/2/4 fusion gene [1].

In this retrospective cohort study, clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular outcome of total 108 cases were recorded.

The study included participants aged 6 to 70 years, with a median age of 30.5 years. The findings were comparable with a similar study by Gv et al., with median age being 30 years and a study by Cheng et al. with median age being 35 years [4, 5].

SS can develop at any age and is equally distributed across the sexes. More than half of the patients are teenagers or young adults, with 77% occurring before the age of 50. The relative prevalence of SS compared with other soft tissue sarcomas is age-dependent, ranging from 15% in patients aged 10–18 years to 1.6% in individuals over 50 years [1].

Similar to Okcuet et al., Segel et al., Yaser et al. and GV1 et al., this study found a male preponderance [5–8].

Lower extremity was the most common site affected in the present study followed by upper extremity, head and neck, thorax, abdomen, pelvic region, and trunk/back. Involvement of lower limb as the most common site was comparable in some of the recent studies [4, 5, 8, 9].

Few rare sites reported were paratesticular soft tissue (one case) and frontal lobe of brain (one case).Primary intracranial synovial sarcoma are rare and has been reported as metastasis from SS of other sites [10]. In present study too, patient diagnosed as frontal lobe SS had undocumented history of nephrectomy. Primary SS of the paratestis are rare tumors, with total 18 cases reported in the literature till date with 4 case reports and a single case series of 14 patients [3, 11, 12]. Primary paratesticular SS are predominantly of monophasic subtype as reported in the literature [3, 11]. However, present case of primary paratesticular SS was of poorly differentiated subtype, which is similar to another case report published in 2019 [12]. Primary SS of head and neck region are uncommon. In the present study there were six cases of primary head and neck SS, amongst which two cases were of larynx, 1 from orbit, 1 from occipital region, 1 from submandibular and 1 from the parotid region.

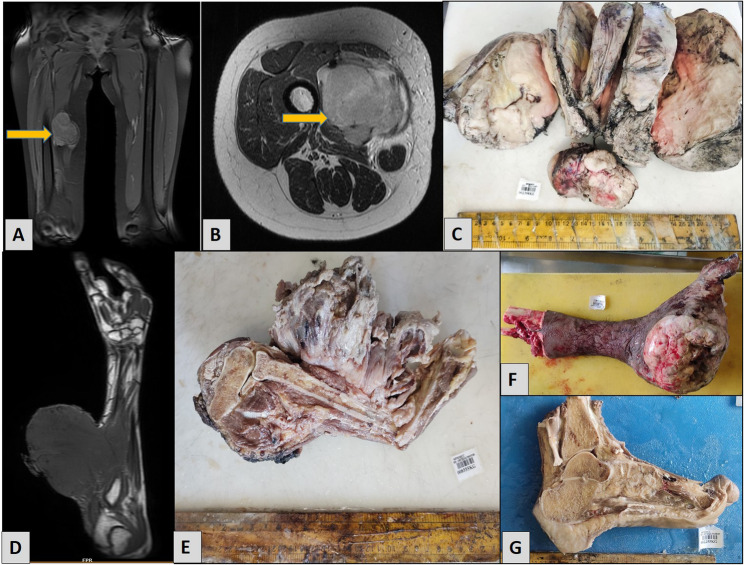

Radiologically, most cases present as a round to oval, lobulated mass, with underlying bone involvement being rare. Grossly SS typically appears tan or grey and can be multinodular or multicystic. In most of our cases, gross appearance was lobulated grey white soft mass with some of the cases showing myxoid and necrotic areas (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Radiology and Gross specimens A MRI shows a well-defined soft tissue mass involving the right thigh without any underlying bone erosion B Cross sectional image of the same mass, which was hypointense on T1, and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2 C Gross photograph of the thigh mass shows a solid, lobulated, grey-white tumor with areas of hemorrhage. D MRI of right forearm shows a large well-defined soft tissue mass involving the dorsal aspect of the forearm, measures approximately 10.4 × 10.3 × 12 cm. E Gross picture of the forearm mass shows a large tumor with extensive areas of necrosis. F Below-knee amputation specimen of left lower leg shows a huge lobulated tumor involving the medial aspect of foot with overlying skin ulceration. G Gross photograph of a left foot with a solid tumor involving the heel

Histologically, SSs are characterised as monophasic (most common) or biphasic (around one-quarter to one-third of cases). Biphasic SS consists of epithelial and spindle cell components in variable amounts. The spindle cells in biphasic SS are similar to those in monophasic SS and are generally uniform with scant cytoplasm and ovoid, hyperchromatic nuclei that have regular granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. The nuclei may appear to overlap due to the high N: C ratio. Typically, spindle cells in both monophasic and biphasic SSs are grouped in thick cellular sheets or vague fascicles, with occasional tigroid nuclear palisading or a herringbone architectural pattern. The amount of collagen in SS is variable and usually sparse, but it may contain ropy or wiry collagen strands, hyalinised collagen bands, or intense fibrosis foci (particularly after irradiation) [1]. Some cases can show myxoid change with alternating hypocellular and more-cellular areas, as well as retiform cords or microcysts [13]. Many SSs have a staghorn-shaped vascular pattern that resembles a solitary fibrous tumour or haemangiopericytoma (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histomorphological features A Low power view shows the Herring Bone pattern of arrangement of the tumor cells, H&E, 20X. B Higher magnification shows the cells have spindled, elongated nuclei and scanty cytoplasm, H&E, 40X. C Round cell morphology of the tumor cells along with brisk mitosis is seen, H&E, 40X. D Hemangiopercytomatous pattern of blood vessels are seen., H&E, 20X. E Thick collagen bundles were noted amidst the tumor cells, H&E, 20X. F Microsection shows thin ropey collagen in few of the cases, H&E, 40X. G Sclerotic stroma in noted in focal areas in some of the cases. H Areas of calcification are noted. I Epithelioid morphology of the tumor cells is seen in one of the cases, H&E, 40X. I Cytoplasmic clearing is seen in the tumor cells. J Bcl 2 is positive, H&E, 40X. K Diffuse nuclear positivity of SS18 is seen, H&E, 20X

Mast cells are present in varying numbers. Areas of calcification and/or ossification are observed in up to one-third cases of SS [1].

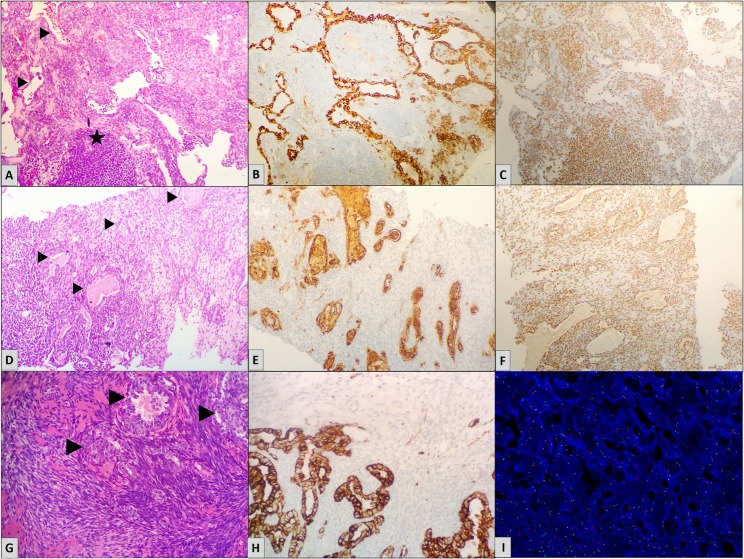

Biphasic synovial sarcoma is characterized by epithelial cells forming solid nests, cords, or glandular structures with tubular, alveolar, or papillary architecture. The epithelial cells are cuboidal to columnar with vesicular nuclei and palely eosinophilic cytoplasm, contrasting with the basophilic spindle cell component. Mucin may be present within glandular lumina. Predominance of the epithelial component can mimic adenocarcinoma; however, a spindle cell component is almost always identifiable [1]. Immunohistochemically, epithelial elements express pan-cytokeratin and EMA, while spindle cells are positive for TLE1 and SS18-SSX, aiding in distinction from carcinoma (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Biphasic synovial sarcoma cases with highlighted epithelial glandular component (arrow heads). A A biphasic tumor with the epithelial component arranged in glandular pattern. Stromal nodule is highlighted by star, H&E, 40X. B Pan-CK highlights the epithelial glandular components of the same case, with the adjacent spindle cell component being negative, H&E, 40X. C Tumor cells show diffuse nuclear positivity for TLE-1, H&E, 20X. D Biphasic tumor showing eosinophilic secretions inside the glandular components, H&E, 40X. E EMA is positive in the epithelial components of the same case, H&E, 40X. F Diffuse nuclear positivity of SS18:SSX is seen. G Biphasic tumor showing periglandular arrangement of the spindle cell component, H&E, 40X. H Pan-CK highlights the epithelial glandular components I Fluorescent in situ Hybridization depicting SS18:SSX translocation

Some cases can have poorly differentiated areas with increased cellularity, significant nuclear atypia, and increased mitotic activity (> 6 mitoses/mm2 or > 10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields of 0.17 mm2) [14].

Fascicular spindle cells (similar to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours), small round hyperchromatic tumour cells (similar to Ewing sarcomas), or epithelioid cells may be found in poorly differentiated cases [15] (Fig. 3).

Unlike normal biphasic or monophasic SS, poorly differentiated SS are more likely to contain necrosis, a branching vascular pattern, and thin fibrovascular septa between nests of cancer cells [16].

In the present study, monophasic synovial sarcoma was the most common histological pattern (73%). Biphasic type comprised of total 19% cases and poorly differentiated were 8% (9 cases).

So, the present study found that monophasic SS were the most common histological type, which is consistent with previous studies [5].

Among the nine poorly differentiated cases, two exhibited round cell morphology; one of these also showed rosette formation. In this case, Ewing sarcoma was considered in the differential diagnosis; however, NKX2.2 was negative. FISH for SYT translocation was subsequently performed and yielded a positive result. Another poorly differentiated case demonstrated alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas, both showing plexiform vasculature within a myxoid stroma. One additional case revealed focal anaplasia with increased mitotic activity.

Foo et al. and Gv et al. described 22 cases and 4 cases of poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma respectively [5, 17]. IHC plays a vital role in the diagnosis of SS, specifically in poorly differentiated subtypes. It also helps in ruling out other differentials having morphological similiarity with SS. Our case of primary paratesticular synovial sarcoma had a poorly differentiated morphology with extensive areas of necrosis and lymphovascular invasion. Grossly the tumor had a lobulated appearance, on cut section areas of haemorrhage, necrosis and calcification were noted (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Paratesticular synovial sarcoma case A Gross photograph of the paratesticular mass showing areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. B Scanner power view shows the normal testicular structures at the lower end and infiltrating tumor nests at the right upper corner (arrows), H&E, 4X. C Higher power view of the tumor nest along with the normal epididymal tubules, H&E, 20X. D Extensive lymphovascular invasion was noted (arrow heads), H&E, 20X. E Numerous dilated and congested vascular channels are noted throughout the tumor, H&E, 20X. F Extensive areas of necrosis (star) and calcification (arrow heads) were noted amidst the tumor cells, H&E, 20X. G Microsection shows the round cell morphology of the tumor cells having clear cytoplasm and brisk mitosis, resembling Ewing sarcoma, H&E, 40X. H On immunohistochemistry, tumor cells are diffusely positive for TLE-1. I CD56 is diffusely and strongly expressed by the tumor cells, the adjacent testicular tubules being negative (arrow heads)

In the present study, TLE1 was the most common positive IHC marker (96.2%%)followed by CD56 (95.9%), CD99 (87%), BCL2 (82.8%), EMA (56.6%), Cytokeratin (51%) and SSX-SS18 (100%). Negative expression of CD34 helped to rule out other possibilities, such as a solitary fibrous tumour (SFT), Dermatofibrosarcoma or hemangioperictyoma. Other negative markers used to rule out close differentials were SMA for Leiomyosarcoma, STAT6 for solitary fibrous tumor, S-100 for neural tumors, and desmin for spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma. NKX2.2 was used in cases showing round cell morphology to differentiate from ewing’s sarcoma (Fig. 5).

TLE1, a gene involved in the WnT pathway, has been discovered to be overexpressed in synovial sarcoma in multiple studies [18, 19].

The transcriptional corepressor TLE1 shows moderate to high nuclear staining in the vast majority of biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated SS. However, TLE1 staining is not specific for SS because it can also appear in histological mimics of SS, in particular malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour and solitary fibrous tumour [1].

Terry et al. found TLE1 positivity in 5% of MPNSTs, 8% of Ewing sarcomas/PNETs, none of the epithelioid sarcomas, and 30% of solitary fibrous tumours [20]. Kosemehmetoglu et al. found TLE1 positivity in 30% of MPNSTs, 33% of epithelioid sarcomas, 20% of solitary fibrous tumours, and none of the Ewing sarcomas [21].

Jagdis et al. found 100% sensitivity, 96% specificity, 92% high positive predictive value, and 100% negative predictive value for TLE1 in synovial sarcoma [22].

TLE1 is a useful marker for dual confirmation due to its high sensitivity and limited specificity in comparison to molecular analysis, which has 96% specificity and sensitivity ranging from 75 to 100% in various studies. This is especially useful when FISH techniques are costly [23].

EMA positivity is noted in 56.6% of the cases in the present study while it showed 80–100% positivity in Okcu et al. [6], 71% in Cheng et al. [4], 76.4% in Rekhi et al. study [23] and 92.8% in GV et al. [5]. Studies have shown that EMA is more broadly expressed in SS than cytokeratins, particularly in monophasic and poorly differentiated subgroups [24]. In biphasic SSs, epithelial cells consistently express EMA and cytokeratins and can comprise practically every cytokeratin subtype [25].

S-100 was mostly negative in our cases, and it came positive only in 6.6% of cases [24]. S-100 was mostly negative in our cases, and it came positive only in 6.6% of cases which was comparable to study by Cheng et al. with 11% positivity for S-100 [4] while other studies by Gv et al. shows 25% positivity for S-100 [5].

Another consistent IHC marker positive in synovial sarcoma is BCL2 which was positive in 82.8% of our cases. This was similar to study by Cheng et al. and Gv et al. with 96% and 100% positivity for BCL2 respectively [4, 5]. It has been found that both pro and antiapoptotic members of BCL2 family are relatively upregulated in SS [26].

CD99 was positive in 87% of the cases in our study similar to Cheng et al. with 93% positivity and Gv et al. with 84% positivity [4, 5].

Thus a panel of markers comprising of TLE1, BCL2, CD56, CD99, Cytokeratin and EMA is recommended for the diagnosis.

More than 95% of synovial sarcoma cases have the pathognomonic translocation t(X:18). This translocation activates the expression of several SS18:SSX oncogenic fusion proteins, leading to sarcomagenesis. Subtypes include SS18:SSX1, SS18:SSX2, and the less prevalent SS18:SSX4. Both FISH and RT-PCR have been used for diagnosing this translocation [27].

In the present study molecular testing was done in total 15 cases and SS18:SSX fusion was detected in total 10 case (5 cases by FISH and 5 cases by RT-PCR). In rest of the 5 cases, 3 cases were negative and in 2 cases the test was uninterpretable.

Recently SS18-SSX fusion specific antibody have been discovered which has both high specificity and high sensitivity for SS.

Zaborowski et al. (2020) investigated the efficacy of SS18-SSX and SSX- CT antibodies in the diagnosis of SS. Surprisingly, the sensitivity and specificity of SS18-SSX antibodies were 87.2% and 100%, respectively, but those of SSX-CT antibodies were 92.3% and 96.1% [28].

In the present study, SS18:SSX IHC was performed in 5 cases with positivity in all of them.

According to reports, people with SS had approximate 5- and 10-year survival rates of 60% and 50%, respectively [15].

In present study, median follow-up of the patients was approximately 7.58 months with mean 4-year disease-free survival (DFS) of the patients is 67.04 ± 4.3%. The median 2-year progression-free survival of the patients is 70.11 ± 4.5%.

The mean 4-year overall survival of the patients is 93.58 ± 4.2%. The median 2-year overall survival of the patients is 94.9 ± 2.6%. Hence, in present study 4 years OS of SS is better as compared to other similar studies in the literature such as Aytekin et al. (5 years OS: 87.3%), Cheng et al. (3 years OS: 85.7%), and Yaser et al. (5 years OS: 73%) [2, 4, 8].

Approximately 50% of SS patients develops metastases according to some studies [4].

31.6% developed either a distant metastasis or a local recurrence, in a study by Cheng et al.

Age is a known prognostic factor for the outcomes in patients with SS [4].

Some studies have shown that the younger patients have better survival as compared to older patients. Aytekin et al. in their study found that patients ≥ 35 years had a worse prognosis than those < 35 years [2].

However, some of the studies show no difference in survival rates between various age groups [8]. Present study too did not show any significant correlation between OS and DFS and various age groups.

Previous studies has shown that male sex is linked to a worse prognosis for SS patients [2] while in a study by Cheng et al., no correlation was found between sex and progression free survival of patient [4]. In present study, Out of total 61 male patients, 41 had local recurrence or metastasis and out and the p-value is < 0.05 which implies that male sex had low progression free survival when compared with female sex indicating poor prognosis in male patients.

The tumour site was also linked to prognosis in the literature. Primary tumours in the lower extremities have a better prognosis, while those in the thorax and abdomen have a poor outcome. The results could be attributed to the reason that thoracic tumours are more difficult to remove surgically than primary tumours in other body areas due to their unique location and limited space. Thoracic tumours near vital structures can lead to respiratory failure and a poor prognosis [4]. However, there was no significant correlation between site and survival rates in present study.

Histologically, biphasic SS had a significantly higher OS if compared to monophasic ones, suggesting different biologic behavior by different histotypes [14]. Although, no significant correlation was found between different histologic type and survival rates in present study.

Synovial sarcoma is characterized by relatively high rate of local recurrence and distant metastasis. In present study local recurrenece occurred in 19.4% cases which was comparable to other studies by Bianchi et al. with local recurrence being 17% and 24% in Yaser et al. [8, 9]

In present study, on followup 38% patients had distant metastasis which was comparable to other similar studies by Bianchi et al. and Yaser et al. with 25% and 41.1% distant metastasis rate [8, 9].

Studies have indicated that lung is the most common site of distant metastases followed by lymph nodes and bone [4, 8, 9]. In the present study too, lung was the most common site of metastasis followed by lymph nodes and bone.

Also local and regional metastatic spread of SS is associated with poor prognosis [2]. However in present study no significant correlation was found between survival status and local recurrence and metastasis.

In present study, molecular confirmation for SSX: SS18 gene rearrangements was performed in 15 cases out of which results were positive in 10 cases. (Fig. 4) In rest 5 cases, test was uniterpretable in 2 cases and negative in 3 cases. Pre-analytical handling of specimens, such as delay in fixation, incorrect fixation time, solution, and paraffin embedding difficulties, can impact FISH results [4].

Treatment for SS includes surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. The common treatment received in present study too was surgery in combination with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or both.

Negative surgical margins and adjuvant radiation are key determinants in determining local recurrence-free survival [8].

Long-term follow-up is recommended due to the tumor’s late recurrence and metastatic risk [4].

Synovial sarcoma is more chemosensitive than other types of STS, although which patients benefit from systemic therapy remains unclear [27].

Adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy is commonly used in children and adolescents with intermediate or high-risk tumours (i.e., > 5 cm, nodal involvement, positive margins), with ifosfamide and doxorubicin being the most prevalent drugs [27].

Clinical trials have explored novel drugs such as receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, epigenetic modifiers, and immunotherapies. Currently, only pazopanib, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is approved for clinical use [27].

Amongst the 3 FISH negative cases, 2 cases lost to follow up and 1 case of upper back SS with lung and bone metastasis is currently doing well after receiving chemotherapy (Ifosfomide & Adriamycin) and is receiving pazopanib.

Limitation of the study

The current study includes only 108 cases of SS which may be a small number and since the study duration is only 4 years, a longer followup with a large cohort is necessary to predict the prognosis and survival outcomes of this entity. The new IHC surrogate marker for SSX: SS18 translocation such as SSX: SS18 and SSX-CT IHC was not performed in most of the cases due to non-availabilty of the marker in our department during the study. Also the FISH and RT-PCR testing was not performed in all the tests and diagnosis was given mostly on the basis of histomorphology and immunohistochemistry findings.

Conclusion

Though SS is most frequently known to occur in the extremities of young individuals, it can also occur in some unusual locations such as larynx, orbit, brain, and paratesticular soft tissue. Meticulous histomorphologic evaluation and awareness of the typical and atypical histology of SS, specially at unusual locations is necessary for diagnosis of this entity.

Apt application of immunohistochemical markers such as SSX-SS18, TLE1, CD56, BCL2, EMA and CD99 along with cytogenetics (SSX: SS18 translocation) assist in diagnostic confirmation. The main therapeutic modality is surgical excision with negative margins, with the addition of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy based on patient and tumour characteristics. Periodic followup is necessary to avoid local recurrence and metastasis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical staff of our department for processing the samples and doing immnohistochemical tests.

Authors’ contributions

ID- concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical review of the manuscript, supervision. HR- analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript. ZC, SP, AK, AG, SN, SH, PP, AM, RBS, SNS, DP- critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content, supervision. All authors have reviewed the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy. No funding has been received for the study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC, MPMMCC & HBCH, Project no. 11000639). This research has been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Human Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations is not applicable (as it was a retrospective observational study where no active intervention has been done).

Consent for publication

The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC, MPMMCC & HBCH, Project no. 11000639) and the consent for publication has been granted.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.BlueBooksOnline. Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chaptercontent/33/121. Cited 2024 Jul 28.

- 2.Aytekin MN, Öztürk R, Amer K, Yapar A. Epidemiology, incidence, and survival of synovial sarcoma subtypes: SEER database analysis. J Orthop Surg. 2020;28(2):2309499020936009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobo A, Mishra SK, Acosta AM, Kaushal S, Akgul M, Williamson SR et al. SS18-SSX expression and clinicopathologic profiles in a contemporary cohort of primary paratesticular synovial sarcoma: A series of fourteen patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2025;49(1):11-19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cheng H, Yihebali C, Zhang H, Guo L, Shi S. Clinical characteristics, pathology and outcome of 237 patients with synovial sarcoma: single center experience. Int J Surg Pathol. 2022;30(4):360–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gv S, Chougani S, Kharidehal D, Vissa VRS. Spectrum of synovial Sarcoma-clinicopathological and immunohistochemical correlation. Ann Pathol Lab Med. 2020;7(8):A422–433. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okcu MF, Munsell M, Treuner J, Mattke A, Pappo A, Cain A, et al. Synovial sarcoma of childhood and adolescence: a multicenter, multivariate analysis of outcome. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;21(8):1602–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal NH, Pavlidis P, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Noble WS, DeSantis D, et al. Classification and subtype prediction of adult soft tissue sarcoma by functional genomics. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(2):691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaser S, Salah S, Al-Shatti M, Abu-Sheikha A, Shehadeh A, Sultan I, et al. Prognostic factors that govern localized synovial sarcoma: a single institution retrospective study on 51 patients. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl. 2014;31(6):958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi G, Sambri A, Righi A, Dei Tos AP, Picci P, Donati D. Histology and grading are important prognostic factors in synovial sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(9):1733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel M, Li L, Nguyen HS, Doan N, Sinson G, Mueller W. Primary intracranial synovial sarcoma. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016;2016:5608315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nesrine M, Sellami R, Doghri R, Rifi H, Raies H, Mezlini A. Testicular synovial sarcoma: A case report. Cancer Biol Med. 2012;9(4):274–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yojenetha S, Ngan KW, Pathmanathan R, Ruwaida AR. Paratesticular and retroperitoneal poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma: a case report. Pathol (Phila). 2019;51:S94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krane JF, Bertoni F, Fletcher CD. Myxoid synovial sarcoma: an underappreciated morphologic subset. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 1999;12(5):456–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillou L, Benhattar J, Bonichon F, Gallagher G, Terrier P, Stauffer E, et al. Histologic grade, but not SYT-SSX fusion type, is an important prognostic factor in patients with synovial sarcoma: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergh P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Gherlinzoni F, Berlin O, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, et al. Synovial sarcoma: identification of low and high risk groups. Cancer. 1999;85(12):2596–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Silva MVC, McMahon AD, Paterson L, Reid R. Identification of poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma: a comparison of clinicopathological and cytogenetic features with those of typical synovial sarcoma. Histopathology. 2003;43(3):220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foo WC, Cruise MW, Wick MR, Hornick JL. Immunohistochemical staining for TLE1 distinguishes synovial sarcoma from histologic mimics. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(6):839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allander SV, Illei PB, Chen Y, Antonescu CR, Bittner M, Ladanyi M, et al. Expression profiling of synovial sarcoma by cDNA microarrays: association of ERBB2, IGFBP2, and ELF3 with epithelial differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(5):1587–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen TO, West RB, Linn SC, Alter O, Knowling MA, O’Connell JX, et al. Molecular characterisation of soft tissue tumours: a gene expression study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2002;359(9314):1301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terry J, Saito T, Subramanian S, Ruttan C, Antonescu CR, Goldblum JR, et al. TLE1 as a diagnostic immunohistochemical marker for synovial sarcoma emerging from gene expression profiling studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(2):240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosemehmetoglu K, Vrana JA, Folpe AL. TLE1 expression is not specific for synovial sarcoma: a whole section study of 163 soft tissue and bone neoplasms. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2009;22(7):872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagdis A, Rubin BP, Tubbs RR, Pacheco M, Nielsen TO. Prospective evaluation of TLE1 as a diagnostic immunohistochemical marker in synovial sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(12):1743–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rekhi B, Basak R, Desai SB, Jambhekar NA. Immunohistochemical validation of TLE1, a novel marker, for synovial sarcomas. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(5):766–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelmus M, Guillou L, Hostein I, Sierankowski G, Lussan C, Coindre JM. Monophasic fibrous and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma: immunohistochemical reassessment of 60 t(X;18)(SYT-SSX)-positive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(11):1434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miettinen M, Limon J, Niezabitowski A, Lasota J. Patterns of keratin polypeptides in 110 biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas. Virchows Arch Int J Pathol. 2000;437(3):275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrott JJ, Zhu JF, Smith-Fry K, Susko AM, Nollner D, Burrell LD, et al. The influential role of BCL2 family members in synovial sarcomagenesis. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2017;15(12):1733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gazendam AM, Popovic S, Munir S, Parasu N, Wilson D, Ghert M. Synovial sarcoma: A clinical review. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(3):1909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaborowski M, Vargas AC, Pulvers J, Clarkson A, de Guzman D, Sioson L, et al. When used together SS18–SSX fusion-specific and SSX C-terminus immunohistochemistry are highly specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma and can replace FISH or molecular testing in most cases. Histopathology. 2020;77(4):588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.