Abstract

The gas-solid fluidized bed with liquid spray has been used in the industrial processing. Investigating the flow behaviors is crucial for optimizing the fluidized bed reactor. This research experimentally investigated the effects of gas velocities, temperature, height-to-diameter ratios, and solid-liquid ratios on flow characteristic in a spray-fluidized bed. The findings revealed that as the gas velocities increased, the standard deviation of pressure pulsation exhibited an upward trend, while the fluidization index initially decreases before subsequently increasing, achieving optimal fluidization quality at a velocity of 0.25 m/s. As the temperature rises, the trends of the pressure pulsation show contrasting trends before and after adding liquid, with the lowest fluidization index observed at 510 °C. An increased height-to-diameter ratio contributes to a rise in the pressure pulsation, and the fluidization index first decreases and then tends to be stable. Additionally, as the solid-liquid ratios increase, the pressure pulsation also rises after adding liquid, and the entrainment rate was negatively correlated with the average particle size of the remaining particles in the bed. The findings elucidate liquid-phase effects on gas-solid dynamics, directly informing strategies to optimize chlorination efficiency of the carbonized slag and improve reactor stability.

Keywords: Carbonized slag, Flow characteristic, Pressure drop, Fluidized bed

Subject terms: Chemical engineering, Fluid dynamics, Particle physics

Introduction

Gas-solid fluidized bed reactors are extensively employed due to the superior mixing capability and heat and mass transfer rate, which also incorporate liquids and have been utilized in various chemical processes1–5. In the process of high-temperature carbonization and selective chlorination of titanium-bearing blast furnace slag (TBBFS)6,7, TBBFS is carbonized at high temperatures (typically 1100–1300 °C), converting titanium oxides into titanium carbide (TiC) and iron oxides into metallic iron8. Subsequently, chlorine gas is introduced to selectively react with TiC, resulting in the production of TiCl4. However, this exothermic reaction generates significant heat. To manage the furnace temperature, TiCl4 mud is added from the top of chlorination furnace9,10. This mud acts as a heat sink to moderate the bed temperature, and its evaporation enhances gas-liquid interactions, promoting uniform chlorine distribution. Additionally, the liquid mud evaporates immediately upon contact with the hot bed, creating a gas-solid-liquid multiphase system11. The presence of a liquid phase exerts a profound influence on the heat transfer, mass transfer, and flow dynamics within the fluidized bed12,13.

Many scholars have explored the hydrodynamic behavior of spray-fluidized beds which are created by introducing a liquid phase into gas-solid fluidized beds14–17. Mclaughlin et al.18 investigated the fluidization behavior of class B particles upon the addition of liquid. The research revealed that the fluidization behavior of class B particles transformed into that of class A or even class C particles after the liquid addition. Zhou et al.19 carried out investigations into the fluidization mechanism of a wet particle fluidized bed, examining various liquid addition rates under high-temperature conditions. They found that evaporation of the liquid increased the apparent gas velocity within the bed and enhanced fluidization when liquid was added at a low rate. Xu et al.20 explored the impact of liquid contents on the fluidization behaviors of Geldart-D particles, focusing on the fluidizing state, minimum fluidizing velocity, and bed pressure. Silitonga et al.15 monitored the vaporization rates of liquids injected into fluidized beds. The liquid content that accumulates in the bed layer was determined under steady-state conditions. As the liquid temperature falls below the boiling point, gas mixing influences the vaporization process. Geng et al.21 discovered a negative correlation between the numbers and sizes of agglomerating particle in a spray-fluidized bed. As the amount of liquid increased, the intensity of particle agglomeration also rose. Song et al.22 constructed a circulating fluidized bed that incorporated a feature of central pulsating flow. Through the utilization of a conductivity probe and waveform analysis, they demonstrated that the introduction of pulsating flow enhances turbulence within the experimental range.

The gas-solid-liquid multiphase flow behaviors in a fluidized bed with liquid spray requires further investigation. This research explores the impact of liquid addition on the flow characteristics of carbonized slag by establishing a hot fluidized bed with liquid spray. The influences of gas velocities, bed temperatures, the height-to-diameter ratios and solid-liquid ratio on pressure drop, the standard deviation of pressure and the fluidization index are examined. The entrainment rate of particles and the size distribution of residual particles within the bed are analyzed. The findings hold significant implications for enhancing the chlorination process of carbonized slag and ensuring the steady operation of the spray-fluidized bed reactor.

Materials and methods

Raw materials

The carbonization slag is selected as the particle phase. The relevant physical property parameters are listed in Table 1. Figure 1 graphically represents the particles size distribution, with the average particle size, denoted as Dv(50), measuring 61.4 μm. Geldart classifies particles into four categories: A, B, C, and D based on their fluidization characteristics and average particle size23. In this experiment, a nitrogen-carbonized slag gas-solid system falls within Group A.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of carbonized slag.

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk density | 1350 | kg/m3 |

| Actual density | 3090 | kg/m3 |

| Compaction density | 1695 | kg/m3 |

| Sphericity | 0.78 | - |

| Packed bed voidage | 0.56 | - |

| Voidage at minimum fluidization | 0.61 | - |

Fig. 1.

Particle size distribution of carbonized slag.

Experimental apparatus

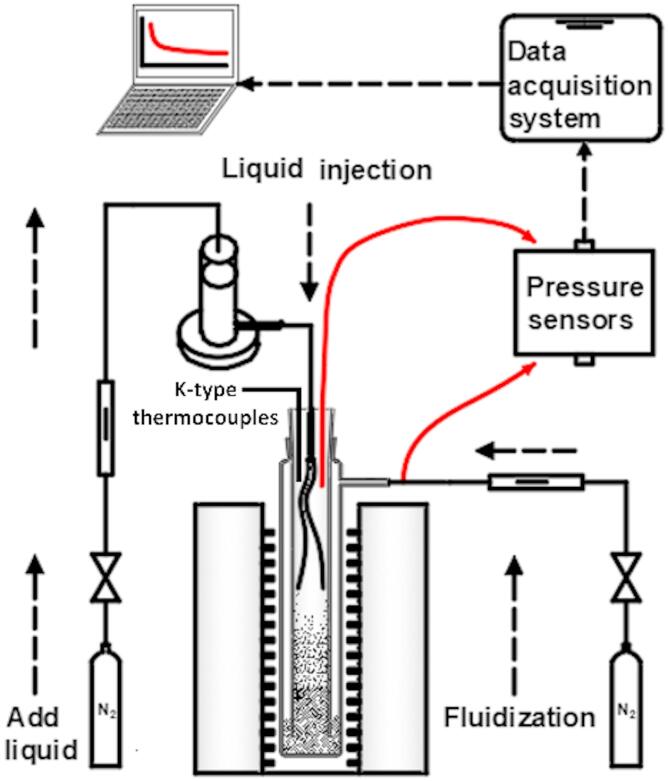

Figure 2 depicts the experimental apparatus utilized in this research, which comprises several essential components: liquid storage devices, liquid feeding devices, data acquisition devices, heating devices, and fluidization devices. The liquid storage system includes a storage tank and a flexible silicone tube (1.5 mm inner diameter). The storage tank has a maximum capacity of 100 ml. A metal pipe with an inner diameter of 3 mm serves as the infusion pipe, and it is connected to the liquid storage tank via silicone tube. In the experiment, the upper section of the liquid storage device is ventilated and pressurized, allowing the liquid phase to flow into the bellows and subsequently enter into the fluidized bed. Nitrogen gas serves as the fluidizing gas and is delivered via a quartz tube with a 6 mm inner diameter. Gas velocity is measured in a room temperature via a mass flow controller and corrected for experimental bed temperature using the ideal gas law. An external data collector is linked to a computer, enabling real-time recording of experimental data through a data acquisition program. The pressure measurements are taken at the top of the reactor and the air inlet port, the total system pressure drop (ΔPsystem) is captured including: Pressure drop across the fluidized particle bed (ΔPbed, constant for fluidized particles), pressure losses in supply lines, distributors, and measurement tubing. The pressure sensor has a range of 0 to 100 kPa. The heating furnace is capable of attaining temperatures as high as 1200 °C, boasting a temperature control accuracy of ± 1 °C. Bed temperature is measured via a K-type thermocouple inserted into the fluidized bed. The reactor is made of quartz glass, which provides high-temperature resistance and allows for visualization of the fluidization state. The fluidized bed reactor has a diameter of 37 mm and a height of 210 mm. The fluidization gas distributor consists of a quartz plate with 1.0-mm-diameter holes. The residual particles collected after fluidization are analyzed for particle size using the QICPIC/L02-OM particle size analyzer.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of experimental apparatus (The pressure difference is measured between the bed and atmosphere, as indicated by the red arrows).

Experimental procedure

The carbonized slag is placed in a fluidized bed within the heating furnace. A specific amount of liquid phase is added to the liquid storage device. The furnace temperature is set within 480–570 °C, and fluidization is achieved using N₂ at velocities of 0.19–0.38 m/s (measured by a rotameter). Gas velocity is maintained constant throughout temperature variations using a mass flow controller. The stable pressure fluctuation data is collected over a predetermined period. Meanwhile, liquid (20–100 mL, corresponding to solid-liquid ratios 0.15–0.30 g/mL) is added over 5–8 s via a nitrogen-driven syringe pump. This generated instantaneous steam flows of 0.17–0.63 m3/s upon evaporation. Once the liquids flow into the fluidized bed, the N2 valve is closed. The particle surface moisture evaporated (< 1–2 s post-injection), confirming no persistent wetting, and bed temperature dropped transiently by 8–12 °C during injection but recovered within 15 s to setpoint (± 3°C), consistent with the short duration of steam generation. After the pressure data and bed temperature stabilize following the addition of the liquid, the fluidization N2 valve is turned off to cease fluidization. Pressure pulsation is measured with a precision of ± 0.3 Pa, and temperature control fluctuated within ± 2 °C. Particle size distribution is analyzed via laser diffraction, with a relative error of ~ 5%. Experiments are conducted under systematically varied conditions to isolate parameter effects, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters.

| Parameters | Tested range | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Gas velocity | 0.19, 0.25, 0.28, 0.32, 0.38 | m/s |

| Bed temperature | 480, 510, 540, 570 | ℃ |

| Height-to-diameter ratio | 0.8, 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.4 | - |

| Solid-liquid ratio | 0.15, 0.18, 0.20, 0.25, 0.30 | g/ml |

| 1 |

Where d is the particle diameter, ρg andρs are the gas and solid densities, and η is the gas viscosity.

The minimum fluidization velocity is recalculated for each temperature (480–570 °C) by incorporating temperature-dependent gas properties. Maintaining ug constant isolates temperature effects on hydrodynamics. The ug/umf ratios confirm operation in the turbulent fluidization regime, as detailed in Table 3, while ug/umf variations are quantified to ensure regime consistency (all above bubbling transition).

Table 3.

Temperature-dependent umf and ug/ umf ratios.

| Bed temperature (°C) | umf (m/s) | ug/ umf |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.028 | - |

| 480 | 0.012 | 15.8–31.7 |

| 510 | 0.011 | 17.3–34.5 |

| 570 | 0.010 | 19.0–38.0 |

The standard deviation of pressure fluctuations primarily serves as a metric to quantify the magnitude of the fluctuations25:

|

2 |

|

3 |

Where  quantifies the dispersion of pressure pulsation values around the mean pressure, Pa; N denotes the total number of pressure fluctuation data points;

quantifies the dispersion of pressure pulsation values around the mean pressure, Pa; N denotes the total number of pressure fluctuation data points;  represents the mean pressure, Pa; and pn signifies the time series of pressure, Pa.

represents the mean pressure, Pa; and pn signifies the time series of pressure, Pa.

The fluidization index, symbolized as FI, is ascertained based on the pressure difference between the fluidized bed and atmospheric pressure, serving as a quantitative measure of fluidization quality. Lower FI values indicate better fluidization quality through two key factors: reduced average pressure drop across the bed, which signifies uniform gas distribution and stable fluidization regime; and increased fluctuation frequency resulting from enhanced particle mixing and optimized bubble dynamics26,27. The fluidization index is computed using the following Eq. (4):

| 4 |

Where  denotes the mean value of pressure drops between the measuring point and atmospheric pressure, Pa; and f is the frequency of pressure fluctuations, Hz. A scaling factor of 10⁴ is applied for normalization of the dimensionless fluidization index by compensating for the order-of-magnitude difference between pressure and frequency parameters based on experimental calibration data.

denotes the mean value of pressure drops between the measuring point and atmospheric pressure, Pa; and f is the frequency of pressure fluctuations, Hz. A scaling factor of 10⁴ is applied for normalization of the dimensionless fluidization index by compensating for the order-of-magnitude difference between pressure and frequency parameters based on experimental calibration data.

The solid-liquid ratio (expressed as g/ml) is defined as the mass of solid per milliliter of liquid introduced into the fluidized bed. The entrainment rate is determined by measuring the mass loss of solid particles collected in the reactor. Specifically, the entrainment rate of particles (Er) was calculated as:

| 5 |

Where m0 and mt are the initial and final masses of particles in the bed, g.

To investigate the impact of liquid injection on entrainment in a hot fluidized bed, the steam-to-gas volume flow ratio (S/G) is quantified,

| 6 |

Where Qsteam is calculated based on the injected liquid volume and injection time, m3/s. Qgas is the pre-injection volumetric flow rate of the fluidization gas, m3/s.

Results and discussion

Effect of gas velocity

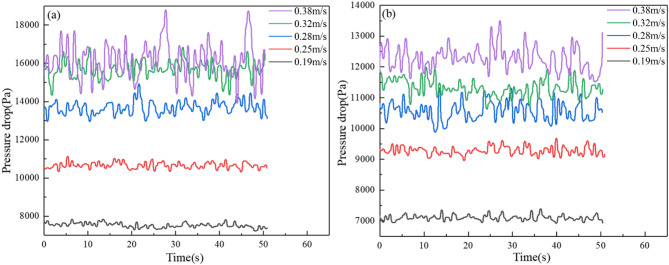

Figure 3a illustrates the variation in pressure drop with increasing gas velocities. As gas velocity rises, the average pressure tends to increase. This is attributed to the gas-solid interaction resulting from a larger volume of gas entering the bed. As shown in Fig. 3b, at a constant gas velocity, the average pressure following the introduction of liquid is lower compared to that prior to the liquid addition. When the liquid phase enters the bed at high temperatures, it rapidly vaporizes, generating an amount of vapor. The vapor interacts with the particle phase, causing some particles to be carried out of the fluidized bed by the gas.

Fig. 3.

Variations of pressure drop under different gas velocities: (a) before liquid addition; (b) after liquid addition.

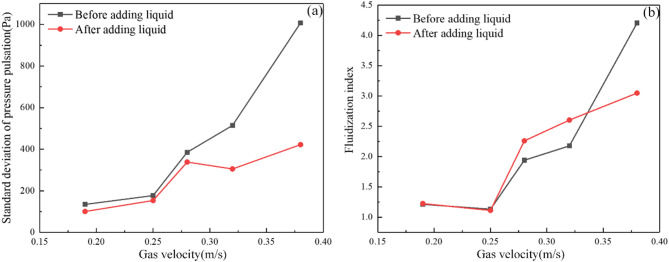

Figure 4a illustrates the trend of standard deviation varied with gas velocities. As gas velocity increases, enhanced gas-solid interactions amplify collision frequency and intensity, elevating pressure fluctuations, elevating pressure fluctuations. At higher gas velocities before liquid addition, the bed exhibits slugging behavior. The slugging dynamics can lead to significant pressure oscillation, explaining the elevated pressure fluctuations. Figure 4b presents the trend of the fluidization index with gas velocity. The fluidization index initially decreases and then increases when the gas velocity exceeds 0.25 m/s. The difference in the fluidization index before and after liquid addition shows a positive correlation with gas velocity, indicating that as gas velocity rises, the influence of the liquid on gas-solid fluidization gradually becomes more significant.

Fig. 4.

Standard deviation of pressure pulsation (a) and fluidization index (b) under different gas velocities.

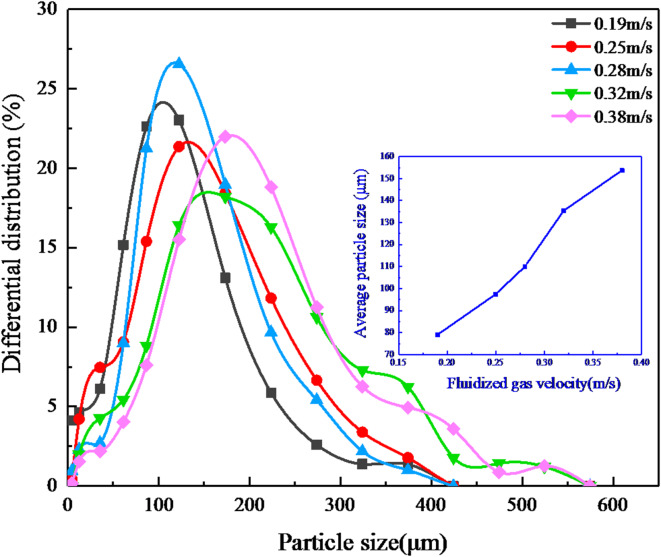

Figure 5 shows the residual particle size changed with the gas velocity. At a lower fluidizing gas velocity (0.19 m/s), a narrow and high particle size distribution curve is observed. In contrast, when the fluidizing gas velocity increases to 0.38 m/s, the proportion of particles > 150 μm rises, leading to a broader and lower particle size distribution curve. The inset in Fig. 5 depicts the correlation between the mean particles size and the gas velocity. Notably, an elevation in gas velocity corresponds with a larger size of the residual particles within the bed. The broadening of the size distribution with increasing gas velocity directly reflects the selective entrainment of fine particles: at higher velocities, finer particles are preferentially entrained, leaving coarser particles behind. The enrichment of coarse particles is further confirmed by the monotonic increase in mean residual particle size (inset), which increases from 78 μm to 153 μm with the rising gas velocity.

Fig. 5.

Variations of particle size distribution under different gas velocities.

Effect of bed temperatures

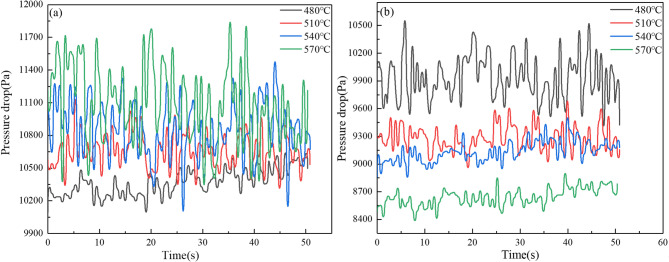

Figure 6 illustrates the pressure variation over time under different bed temperatures, revealing that the mean pressure exhibits contrasting trends before and after the introduction of liquid. Before liquid is added, the mean pressure increases with temperature due to the expansion of the gas phase. Conversely, after the addition of liquid, a higher temperature results in a greater evaporation rate, thereby producing a more instantaneous gas phase.

Fig. 6.

Variations of pressure drops under different bed temperatures: (a) before liquid addition; (b) after liquid addition.

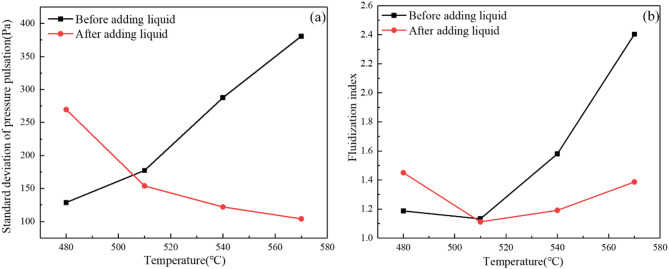

The trend of pressure pulsation standard deviation is illustrated in Fig. 7a. In the absence of liquid, the standard deviation increases as the temperature rises due to the gas phase dilation intensifying bubble aggregation and rupture. Following introduction of liquid, the standard deviation exhibits a downward tendency. Figure 7b shows the trend of the fluidization index. the fluidization index initially decreases and then increases as the temperature rises. Once the temperature surpasses 510 °C, the fluidization index experiences a rapid increase, indicating a deterioration in fluidization quality. This phenomenon is primarily caused by the excessively high temperature, which leads to gas phase expansion, intensifies gas-solid interactions, and disrupts the uniform distribution of solid particles within the fluidized bed.

Fig. 7.

Standard deviation of pressure pulsation (a) and fluidization index (b) under different bed temperatures.

Figure 8 illustrates the size distribution of residual particles within the bed at different temperatures. At 480 ℃, the entrainment rates are relatively small, leading to a high proportion of small particles and consequently a narrow size distribution curve. As temperature increases to 570 ℃, the distribution shifts to a broader curve peaking at 142 μm, reflecting the preferential loss of fine particles from the bed. The inset in Fig. 8 demonstrates the mean size increasing from 88 μm to 137 μm. This trend arises from the selective entrainment of fine particles at higher temperature, the entrainment rate of particles increases from 31.41 to 45.85%.

Fig. 8.

Variations of particle size distribution under different bed temperatures.

Effect of height-to-diameter ratio

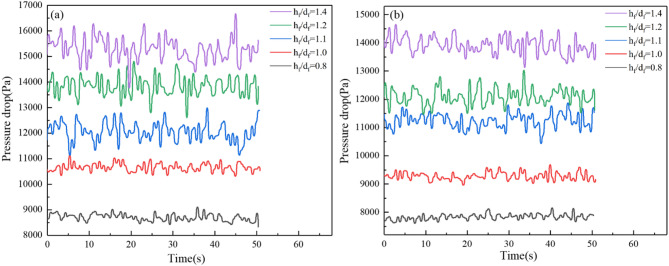

Figure 9 illustrates the pressure pulsation at varying height-to-diameter ratios. The mass of particles within the bed increases with the escalated height-diameter ratio. The escalation in the quantity of the solid phase leads to a more significant resistance that the gas encounters as it flows through the bed layer. As a result, the pressure drop within the bed layer progressively intensifies, indicating an upward trend in average pressure.

Fig. 9.

Variations of pressure drop under different height-to-diameter ratios (hf/df): (a) before liquid addition; (b) after liquid addition.

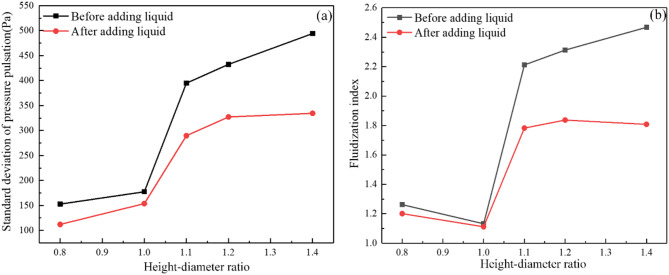

Figure 10a depicts the relationship between the standard deviation and the height-to-diameter ratios. At a constant ratio, the standard deviation pre-liquid addition is greater compared to after. When the pressure stabilizes following the addition of liquid, the diameter of the bubble decreases, and the duration of bubble movement shortens.

Fig. 10.

Standard deviation of pressure pulsation (a) and fluidization index (b) under different height-diameter ratios.

Figure 10b illustrates the fluidization index changed with the height-to-diameter ratios. The fluidization index before and after liquid addition both show a trend of initially decreasing and subsequently increasing. With increasing bed height-to-diameter ratio, the bed becomes more susceptible to bubble coalescence and slugging behavior, where large bubbles grow to nearly the size of the bed diameter. This leads to periodic pressure fluctuations and reduced gas-solid interaction efficiency, the observed increase in fluidization index at high aspect ratios is consistent with the onset of slugging dynamics.

Figure 11 examines the impact of height-to-diameter ratio on particle size distribution. At hf/df=0.8, the particle size distribution exhibits a narrow and sharply peaked shape, with the entrainment rates of 29.47%, indicating a predominance of fine particles in the residual bed. At hf/df=1.2, the curve broadens and shifts to a peak at 151 μm, and the entrainment rate increases to 42.12%, reflecting progressive loss of fine particles. The inset in Fig. 11 shows the mean size initially rises and subsequently declines with the increasing ratio.

Fig. 11.

Variations of particle size distribution under different height-to-diameter ratios (hf/df).

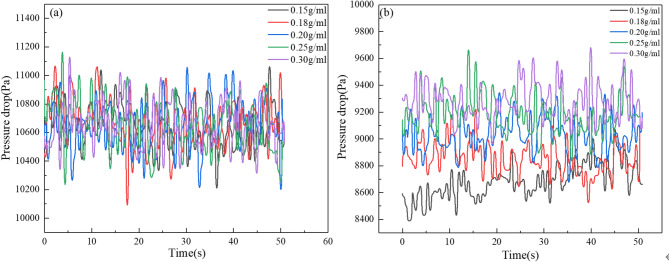

Effect of solid-liquid ratio

Figure 12 shows the pressure fluctuation curves before and after liquid addition under different solid-liquid ratios. Before liquid addition, the pressure within the bed remains relatively uniform. After the liquid is introduced, the solid-liquid ratio becomes a critical factor influencing pressure dynamics. The S/G ratio increases with higher solid-liquid ratios (0.15–0.30 g/mL) and faster injection rates (2.5–12.5 mL/s), leading to a transient increase in total gas volume. This results in an upward shift in average bed pressure.

Fig. 12.

Variations of pressure drop under different solid-liquid ratios: (a) before adding liquid; (b) after adding liquid.

Figure 13a illustrates the standard deviation of pressure pulsation varying with different solid-liquid ratios. As the ratio increases, the residual particle mass in the fluidized bed gradually increases. This augmentation in particle mass leads to a longer duration for the gas phase to traverse the bed, and the process of bubble generation, rise, coalescence, and fragmentation is prolonged. Consequently, the standard deviation remains stable before the introduction of liquid, while it shows an ascending tendency once the liquid is introduced. Figure 13b illustrates the trend of the fluidization index varied with solid-liquid ratios. The fluidization index remains stable before adding liquid, as the solid-liquid ratio increases, the fluidization index gradually decreases after adding liquid, reaching its lowest value at 0.30 g/ml. The thin bed layer leads to localized regions where the particle phase is easily entrained by the gas flow, resulting in channel flow phenomenon, which degrades the fluidization quality.

Fig. 13.

Standard deviation of pressure pulsation (a) and fluidization index (b) under different solid-liquid ratios.

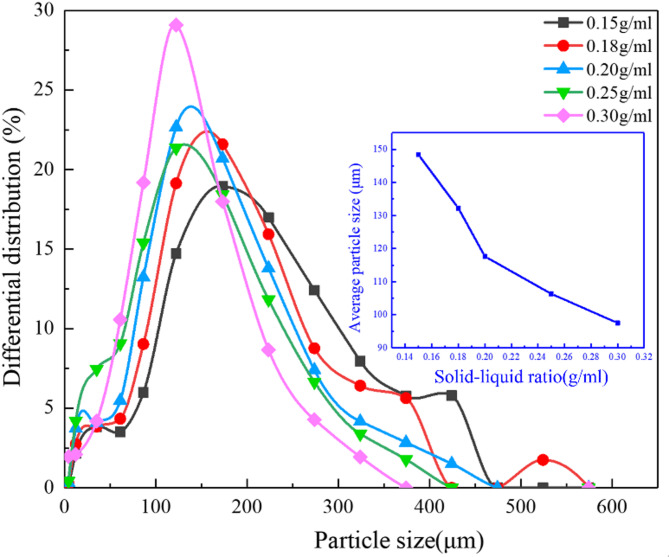

Figure 14 presents the particle size distribution of residual particle under various solid-liquid ratios. At a solid-liquid ratio of 0.15 g/ml, the distribution curve is tall and wide, with the entrainment rate of 51.65%. As the solid-liquid ratio increases to 0.30 g/ml, the size distribution curve becomes narrow and shifts toward smaller particles, with the entrainment rate of 37.38%. The inset in Fig. 14 demonstrates a clear inverse relationship between solid-liquid ratio and mean particle size: the mean size decreases from 148 μm at 0.15 g/ml to 97 μm at 0.30 g/ml. At higher ratios, the entrainment of fine particles is suppressed (lower entrainment rate), allowing more fine particles to remain in the bed (small mean size, narrow distribution).

Fig. 14.

Variations of particle size distribution under different solid-liquid ratios.

Conclusions

This research explores the impact of various operational parameters on the flow characteristic of carbonized slag. The conclusions have been drawn through systematic experiments and analysis:

The standard deviation of pressure pulsation prior to the introduction of liquid is greater than that following the addition of liquid. The fluidization index initially decreases and then increases, reaching its minimum value at 0.25 m/s within the tested range from 0.19 to 0.38 m/s.

Before liquid is introduced, the elevation in temperature induces gas expansion, resulting in an increase in average pressure and the standard deviation of pressure pulsation. Conversely, following liquid addition, liquid evaporation dominates, leading to a reduction in both average pressure and the standard deviation. The fluidization index exhibits a trend of initially decreasing and subsequently increasing with respect to temperature, taking 510 °C as the turning point with the temperature range of 480 to 570 °C.

Both the average pressure and the standard deviation of pressure fluctuations raise with an increase in the height-to-diameter ratio. The fluidization index reaches its lowest value at 1.0 within the tested range of 0.8–1.4. The solid-liquid ratio has little effect on the standard deviation prior to the introduction of liquid ranging from 0.15 to 0.30 g/ml. At higher ratios (0.30 g/ml), the entrainment of fine particles is suppressed, the size distribution curve becomes narrow.

These findings highlight the critical role of hydrodynamic control in fluidized bed systems, which enhances chlorination efficiency through optimized gas-particle interactions and stable operation. Future work will integrate hydrodynamic parameters with chlorination kinetics to advance reactor design and operational strategies. The bed-integrated pressure taps will be adopted to refine the measurement of pressure fluctuations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Talent Introduction and Scientific Research Project of Sichuan University of Science & Engineering (Grant No. 2024RC051).

Author contributions

Yan Zhao: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Bo Liu: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Zhongbin Liu: Supervision, Writing–review & editing, Project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author, Dr. Yan Zhao (yanzhao@suse.edu.cn).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amin, A. M., Croiset, E. & Epling, W. Review of methane catalytic cracking for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 36, 2904–2935 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce, M. C. Gas-solid fluidization with liquid bridging: A review from a modeling perspective. Powder Technol.336, 12–29 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu, F. et al. Particle agglomeration behavior in fluidized bed during direct reduction of iron oxide by CO/H2 mixtures. J. Iron Steel Res. Int.30, 626–634 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, H., Liu, D. Y., Ma, J. L. & Chen, X. P. Influence of cycle time distribution on coating uniformity of particles in a spray fluidized bed by using CFD-DEM simulations. Particuology76, 151–164 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukas, B., Andres, C. & Hochenauer, C. Multi-scale modelling of fluidized bed biomass gasification using a 1D particle model coupled to CFD. Fuel324, 124677 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao, Y. et al. Experimental and numerical study on dynamic characteristics of droplet impacting on a hot tailings surface. Processes10, 1766 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang, F. et al. Study on reaction behaviors and mechanisms of rutile TiO2 with different carbon addition in fluidized chlorination. J. Mater. Res. Technol.18, 1205–1217 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, F. et al. Prediction of structural and electronic properties of Cl2 adsorbed on TiO2 (100) surface with C or CO in fluidized chlorination process: a first-principles study. J. Cent. South. Univ.28, 29–38 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, L. et al. Behavior of magnesium impurity during carbochlorination of magnesium-bearing titanium slag in chloride media. J. Mater. Res. Technol. J Mater. Res. Technol. 13, 204–215 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du, G. C. et al. Chlorination behaviors for green and efficient vanadium recovery from tailing of refining crude titanium tetrachloride. J. Hazard. Mater.420, 126501 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu, F. X. et al. Preparation of TiCl4 from Panzhihua Ilmenite concentrate by boiling chlorination. J. Mater. Res. Technol.23, 2703–2718 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan, S. Y., Ma, J. L., Liu, D. Y., Chen, X. P. & Liang, C. Theoretical and experimental insight into the homogeneous expansion of wet particles in a fluidized bed. Powder Technol.397, 117016 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim, E. W. C. Mixing behaviors of dry and wet particles in a pulsating fluidized bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.62, 21483–21497 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo, H., Ma, Y. L., Liu, M. Y., Li, S. J. & Duan, J. W. Multibubble behavior and solid circulation rate in a gas-liquid-solid Circulating micro-fluidized bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.62, 18105–18121 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silitonga, H. M., Briens, C., Berruti, F., Careaga, F. S. & McMillan, J. Experimental study of liquid vaporization in a fluidized bed. Can. J. Chem. Eng.101, 172–183 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zafiryadis, F. et al. Injection of gas-liquid jets into gas-solid fluidized beds: A review. Particuology76, 63–85 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun, J. Y. et al. Experimental and modeling investigation of liquid-Induced agglomeration in a Gas-Solid fluidized bed with liquid spray. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.59, 11810–11822 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin, L. J. & Rhodes, M. J. Prediction of fluidized bed behaviour in the presence of liquid bridges. Powder Technol.114, 213–223 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou, Y., Shi, Q., Huang, Z., Wang, J. & Yang, Y. Effects of liquid action mechanisms on hydrodynamics in liquid-Containing Gas-Solid fluidized bed reactor. Chem. Eng. J.285, 121–127 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu, H., Zhong, W., Yuan, Z. & Yu, A. B. CFD-DEM study on cohesive particles in a spouted bed. Powder Technol.314, 377–386 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geng, P. F. et al. Experimental investigation of temperature distribution and hydrodynamics characterization in a high-temperature gas–solid fluidized bed with sidewall liquid injection. Fuel327, 125087 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song, Y. F. et al. Experimental study on flow characteristics of liquid-solid Circulating fluidized bed with central pulsating liquid flow. Powder Technol.411, 117925 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geldart, D. Types of gas fluidization. Powder Technol.7, 285–292 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, C. L. et al. The effect of particle size distribution on minimum fluidization velocity at high temperature. Powder Technol.126, 297–301 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bi, H. T. A critical review of the complex pressure fluctuation phenomenon in gas-solids fluidized beds. Chem. Eng. Sci.62, 3473–3493 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao, Y. et al. Effect of liquid addition on gas-solid fluidization. Chem. Eng. Technol.44, 1596–1603 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aghbashlo, M. et al. Measurement techniques to monitor and control fluidization quality in fluidized bed dryers: A review. Dry. Technol.32, 1005–1051 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author, Dr. Yan Zhao (yanzhao@suse.edu.cn).