Abstract

Background

Access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services is recognized as a fundamental human right and a core priority within global health agendas, particularly under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Despite significant legal advances such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities women with motor disabilities continue to face persistent marginalization, especially in low- and middle-income African countries. This systematic review aims to identify the barriers and facilitating factors influencing their access to SRH services.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024555816), this review adopted a Population, Concept, Context (PCC) search strategy. Studies published between 2001 and 2024 in English and French were retrieved from major electronic databases and grey literature sources. Data extraction and methodological assessment were conducted independently by multiple reviewers. A narrative synthesis was used for qualitative findings and a descriptive approach for quantitative data.

Results

Twenty-eight studies covering eleven African countries were included. The main barriers identified were grouped into five categories: physical and logistical constraints, social and attitudinal barriers, institutional limitations, economic hardships, and informational and communication barriers. Key facilitating factors included healthcare provider training, infrastructure adaptation, community mobilization, and the development of inclusive public health policies.

Conclusion

This review highlights the urgent need to embed disability inclusion within national SRH policies and to promote multisectoral strategies that address the systemic inequalities limiting access for women with motor disabilities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12978-025-02117-8.

Résumé

Background

L’accès à la santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) est reconnu comme un droit fondamental et un objectif clé des stratégies de santé publique, particulièrement dans le cadre des Objectifs de Développement Durable (ODD). Malgré des avancées juridiques, notamment via la Convention relative aux droits des personnes en situation de handicap, les femmes vivant avec un handicap moteur demeurent marginalisées, en particulier dans les pays africains à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Cette revue systématique explore les obstacles et les leviers influençant leur accès aux services SSR.

Méthodes

Conduite selon les recommandations PRISMA et enregistrée sur PROSPERO (CRD42024555816), cette revue a mobilisé une stratégie de recherche basée sur le modèle PCC. Les études publiées entre 2001 et 2024 en français et en anglais ont été sélectionnées à partir de bases de données électroniques et de la littérature grise. L'extraction des données et l’évaluation méthodologique ont été réalisées indépendamment par plusieurs évaluateurs. L'analyse a combiné une approche narrative pour les résultats qualitatifs et une synthèse descriptive pour les données quantitatives.

Résultats

Vingt-huit études ont été incluses, couvrant onze pays africains. Les principaux obstacles identifiés relèvent de contraintes physiques, sociales, institutionnelles, économiques et informationnelles. Des stratégies telles que la formation des prestataires, l'adaptation des infrastructures et le renforcement des politiques inclusives apparaissent comme essentielles.

Conclusion

Cette revue souligne la nécessité d'intégrer la question du handicap dans les politiques nationales de SSR et d’adopter des interventions multisectorielles pour réduire les inégalités d’accès.

Background

The World Report on Disability [1], published by the World Health Organization, estimates that around 1.3 billion individuals—approximately 16% of the global population—are living with a disability. This significant proportion highlights the urgent need to ensure their full integration into health systems. Such integration is not only a matter of ethics and social justice but also a critical strategy for advancing global public health objectives.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 3, emphasize the need to guarantee equitable and universal access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. Access to these services forms a cornerstone of universal health coverage and the promotion of population well-being. Ensuring that persons with disabilities are included in SRH policies and services is both a moral responsibility and a sound economic investment. Research indicates that each USD allocated to accessible preventive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, including cancer screening, family planning, and antenatal care; can yield up to nine USD in returns through future healthcare savings and enhanced economic productivity. This highlights not only the ethical imperative but also the economic rationale for integrating women with disabilities into national SRH systems [2, 3].

Following the 2006 adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [4], significant global efforts have focused on significant global efforts have been directed toward securing the right of individuals with disabilities to receive appropriate healthcare, including SRH services, within frameworks that are inclusive, flexible, and free from discrimination. This commitment was further strengthened by the Nairobi Statement on ICPD 25 [5], which reaffirmed the essential role of human rights and inclusion in ensuring access to SRH services for marginalized populations, among them persons with disabilities.

Despite these advances, women with disabilities, especially those with motor impairments, remain systematically marginalized in many parts of the world. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) across Africa [6–8], these women often encounter overlapping barriers that limit their access to essential SRH services. These barriers include, but are not limited to, physical inaccessibility of health infrastructure, inadequate provider training, limited transportation, lack of accessible information, and pervasive societal stigma regarding disability and sexuality. Motor disabilities present specific and tangible challenges in navigating health systems, primarily due to mobility restrictions and the need for adapted infrastructure. These barriers include the lack of ramps, inaccessible examination tables, inadequate transportation, and untrained health professionals. The focus on motor disabilities in this review stems from their infrastructure-dependent impact on service access, which differs in nature and intensity from other forms of disability such as sensory or intellectual impairments.

Although a growing number of studies have addressed SRH access among persons with disabilities, existing reviews tend to group diverse disability types together or focus on global data without regional specificity. To our knowledge, no systematic review to date has focused exclusively on the intersection of motor disability, SRH access, and the African LMIC context. This constitutes a critical gap, as motor impairments have distinct implications for navigating physical environments and interacting with health systems. Addressing this gap is essential for tailoring policies and interventions that are context-sensitive and responsive to the lived experiences of affected women.

This systematic review therefore seeks to synthesize empirical evidence on the barriers and facilitators influencing access to SRH services among women with motor disabilities in low- and middle-income African countries. By consolidating scattered and heterogeneous findings, this review aims to inform more inclusive health policy design, guide disability-sensitive program implementation, and highlight priorities for future research, and promote equitable access to care for one of the most underserved populations in global health.

Methods

This systematic review followed a structured methodology aligned with established best practices in evidence synthesis [9, 10]. Specifically, the review adhered to the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [11], ensuring transparency and completeness in reporting. Furthermore, the methodological process was informed by the five-step systematic review framework described by Khan et al. (2003) [10], which includes:

framing of the research question;

Identifying relevant studies;

Assessing the quality of the studies;

Summarizing the evidence;

Interpreting the findings.

The review protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO international database under registration number CRD42024555816 [12]. This registration supports the reproducibility and rigor of the review process.

Formulation of the research question

The review focused on the following central question:

What are the barriers and facilitators affecting access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for women with motor disabilities in low- and middle-income African countries?

Identification of relevant studies

Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to select the studies:

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

Focused on access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services;Included women or adolescent girls with motor disabilities (defined as physical impairments affecting movement or mobility);

Conducted in LMICs in Africa, as per the World Bank classification (2023) [12];

Published between January 2001 and March 2024; The year 2001 was selected as a starting point because it follows the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, which catalyzed increased attention to disability inclusion, health equity, and rights-based approaches in global health and development.

Reported empirical findings (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods);

Published in peer-reviewed journals, in English or French.

Although grey literature was consulted during the preliminary stages to inform the development of search terms and thematic scope, only peer-reviewed articles were retained for inclusion in the final synthesis to ensure methodological rigor and comparability.

Exclusion criteria

Studies addressing populations outside the defined scope (e.g., individuals with sensory or intellectual disabilities);

Research conducted outside the African context;

Editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor, and policy statements.

Development of the search strategy

The search strategy was based on the PCC framework (Population, Concept, Context) [13]:

Population: Women aged 15–49 living with motor disabilities in low- or middle-income African countries;

Concept: Barriers and facilitators to access;

Context: SRH services.

For the purpose of this review, motor disabilities are defined as impairments that affect mobility and physical functioning, including limitations in walking, standing, reaching, or using limbs. This definition is informed by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [14], which categorizes motor disabilities under impairments of the neuromusculoskeletal and movement related functions.

The review focused specifically on motor or physical disabilities to explore accessibility issues related to the physical environment, transportation, and infrastructural adaptations, dimensions that are particularly relevant in the context of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) service access.

We selected this population due to the physical and structural barriers they typically encounter in accessing SRH services, such as inaccessible buildings, examination equipment, and lack of transportation, which are specifically linked to mobility limitations. These factors are particularly salient in resource-constrained health systems, where physical accessibility is often overlooked.

Furthermore, in line with the World Health Organization’s multidimensional framework, we defined accessibility as comprising [15]:

Physical accessibility: architectural design, adapted transport, and equipment;

Informational accessibility: availability of clear, adapted, and understandable health information;

Economic accessibility: affordability of care, transport, and opportunity costs;

Sociocultural accessibility: influence of social stigma, gender norms, and provider attitudes on SRH service use.

In this review, we defined context as encompassing both macro-level geographic characteristics and meso- to micro-level institutional and service delivery settings. At the geographic level, the review focused exclusively on (LMICs) in Africa, as classified by the World Bank which categorizes economies according to their gross national income (GNI) per capita. At the institutional level, context included the type of health facility, service structure, provider training, and organizational norms, all of which can significantly influence accessibility for women with motor disabilities seeking SRH services.

Studies that incorporated the perspectives of healthcare providers involved in the delivery of SRH services were also considered. The scope of services included reproductive health care, family planning, comprehensive sexuality education, safe abortion services, prenatal and postnatal care, and childbirth assistance.

Electronic searches were conducted in databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Web of Science, covering publications from January 2001 to March 2024. A detailed search strategy was initially designed for Medline, utilizing a combination of keywords, synonyms, and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms), and then adapted to each database using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT).

Complementary manual searches were performed by reviewing the reference lists of selected articles and consulting relevant gray literature sources, including reports from international organizations, doctoral theses, and governmental documents. All references were managed using Zotero software, which facilitated the removal of duplicates.

Study selection process

The selection process, in accordance with PRISMA standards, involved several steps. After duplicate removal via Zotero, two authors (FZ and SH) independently screened titles and abstracts based on the predefined inclusion criteria (see “Eligibility Criteria” section). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Full-text screening was then performed by two other reviewers (HB and RA), with arbitration by a third reviewer if necessary. At this stage, only studies that met all inclusion criteria were retained for the final synthesis. The inclusion criteria considered scope (SRH access), population (women with motor disabilities), geographical setting (African LMICs), study type (empirical), publication date (2001–2024), and language (English/French).

The reasons for exclusion at the full-text screening stage were systematically recorded and categorized. As shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), the most frequent reasons for exclusion were: wrong population (e.g., studies on people with sensory or cognitive disabilities only), irrelevant outcomes (e.g., general health but not SRH-related), ineligible publication type, or incorrect setting (outside Africa or not LMIC).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram selection process adapted to PRISMA

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was developed based on the PRISMA and PCC frameworks. Two authors independently extracted data, resolving discrepancies by discussion and involving a third reviewer if required.

In this review, we adopted Levesque et al.’s conceptual framework [16] of access to healthcare to guide our understanding and organization of findings. Access was defined as a dynamic process comprising five dimensions: approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness, influenced by both system- and user-side factors.

Based on this framework, we systematically identified and classified barriers (i.e., factors that hinder access) and facilitators (i.e., factors that enhance access) across these five dimensions.

Facilitators were defined as empirically grounded enablers, meaning factors that were either reported by participants or interpreted by the original study authors as having supported access to SRH services.

Prescriptive or hypothetical recommendations (e.g., proposed interventions or aspirational suggestions) were not coded as facilitators unless supported by empirical findings. Such recommendations were retained and discussed separately in the Discussion to inform policy implications.

This conceptual orientation allowed for a structured narrative synthesis and meaningful comparison of findings across diverse settings and study designs.We employed a narrative synthesis approach, guided by the framework proposed by Popay et al. [17]. The synthesis process involved:

Preliminary synthesis of findings through structured tabulation and textual summaries;

Exploration of relationships within and between studies by grouping themes across contexts and study types; and.

Development of overarching categories (barriers and facilitators) using an iterative coding process.

This approach enabled the integration of heterogeneous evidence and supported the identification of cross-cutting patterns.

The extraction tool was piloted on five randomly selected studies to ensure clarity and consistency. The following data were collected:

Characteristics of the study population (age, socioeconomic status, type of disability, country);

Study design and methodology;

Key findings related to barriers and facilitators.

The extracted data were organized into an Excel spreadsheet for systematic analysis.

Critical Appraisal of Included Studies.

Quality appraisal

To ensure methodological rigor and assess the internal validity of the included studies, we conducted a structured quality appraisal using tools tailored to each study design. Given the heterogeneity of methods among the included studies, qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, a design-specific approach was adopted rather than relying on a single generic tool.

For qualitative studies, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [17] checklist, which evaluates aspects such as credibility of findings, appropriateness of design and methodology, clarity of research aims, data collection and analysis, and reflexivity.

For quantitative observational studies, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [18], which assesses the quality based on three domains: selection of participants, comparability of groups, and outcome assessment.

For mixed-methods studies, we applied the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [19], version 2018, which allows for simultaneous appraisal of both qualitative and quantitative components as well as their integration.

Each study was assessed independently by two reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. In case of divergence, a third reviewer was consulted. The quality appraisal findings were not used as exclusion criteria but were considered in the interpretation of results and synthesis of evidence.

A detailed scoring per criterion is provided in Supplementary File 1.

Risk of bias assessment and mitigation strategies

Recognizing the potential for methodological bias in systematic reviews, we implemented several strategies to identify and mitigate bias throughout the review process.

To reduce selection bias, all titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers, with a third reviewer consulted in case of disagreement.

To minimize reporting and publication bias, we included both peer-reviewed and grey literature, and searched multiple databases without language restrictions (except for English and French).To limit reviewer bias, a transparent data extraction form was used, and synthesis was conducted by cross-verifying findings.

The potential influence of methodological heterogeneity was addressed through quality appraisal using design-specific tools (CASP, NOS, MMAT), and sensitivity to quality was reflected in the interpretation of results.

Data synthesis and analysis

A combination of qualitative and descriptive quantitative synthesis was conducted in accordance with PRISMA recommendations.

Findings were structured to identify patterns in barriers and facilitators affecting SRH access for women with motor disabilities in African LMICs.

Qualitative results were synthesized thematically using the PCC framework. This approach enabled:

Identification of commonalities and differences across various socio-geographic contexts;

Thematic organization around dimensions such as physical accessibility, social attitudes, and availability of services;

Detection of recurrent themes and subthemes related to obstacles and facilitators.

Thematic coding was performed using NVivo software. Two authors conducted the coding independently, with consensus procedures for resolving discrepancies.

Quantitative data were synthesized descriptively, reporting:

Proportions and prevalence of SRH service access;

Comparative statistics between women with and without motor disabilities.

Although a meta-analysis was initially considered, the heterogeneity of variables and contexts across the studies precluded its implementation. However, quantitative findings were integrated into the qualitative synthesis to strengthen the analysis through triangulation.

Ultimately, the results were structured around two major themes — barriers and facilitators — leading to the development of a conceptual model illustrating the complex interactions influencing access to SRH services for women with motor disabilities.

Results

This review included twenty-eight studies published between 2001 and 2024, covering a variety of geographical and sociocultural contexts. The selected works explore settings such as Morocco [19–21], Ghana [22–24], Ethiopia [25–27], Zimbabwe [28], Kenya [29–31], Senegal [32, 33], South Africa [34, 35], Uganda [36], Zambia [37], Cameroon [38],, and Nepal [39–42],along with a few comparative analyses [43–45].

The majority of these studies used qualitative methodologies (n = 16), followed by literature reviews (n = 5), mixed-method designs (n = 4), quantitative studies (n = 2), and one institutional report (n = 1). Table 1 summarizes the main features of the included studies.

Table 1.

Main features of the included studies

| Author/Year | Country | Study Type | Methodology | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyalmi (2014). Les besoins en sante sexuelle et reproductive des personnes en situation de handicap au maroc | Morocco | Qualitative Descriptive | Document Analysis + Focus Groups with people with disabilities (PWD) + Interviews with professionals | Cultural taboos, stigmatization, lack of adapted sexual education, institutional invisibility | Sexual education, institutional integration, advocacy from associations |

| Dupras (2011).la santé sexuelle et reproductive des personnes en situation de handicap. Analyse de la situation et recommandation, rapport soumis à l’unfpa maroc et ses partenaires, | Morocco | Situational Analysis (Institutional Report) | Document Review, Institutional Interviews, Association Fieldwork | Absence of targeted policies, lack of statistical visibility, social prejudices, physical and informational inaccessibility | Strategic recommendations: training, multisectoral coordination, universal accessibility |

| CNMH & UNFPA (2019) perception de la santé sexuelle et reproductive chez les personnes en situation de handicap(s) physique(s) et/ou sensoriel(s) rabat sale kenitra, marrakech safi, fes meknes et l’oriental | Morocco (4 regions) | Mixed (Quantitative & Qualitative) | Field Survey, Interviews, Focus Groups in 4 Moroccan regions | Lack of knowledge about sexual and reproductive rights (SRH), communication difficulties, cultural and physical barriers, stigmatization | Awareness campaigns, service adaptation, sexual education, institutional advocacy |

| Soule, o., & sonko, d. (2022). Examining access to sexual and reproductive health services and information for young women with disabilities in senegal: a qualitative study | Senegal (Dakar Region) | Mixed (Quantitative & Qualitative) | Semi-Structured Interviews, Thematic Analysis | Structural inaccessibility of healthcare facilities, financial limitations, transportation issues, long wait times, provider discrimination | - Better information on contraceptives, easier access to information, specific improvements for people with disabilities in the health system |

| Devkota, h. R., murray, e., kett, m., & groce, n. (2017). Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural nepal | Nepal (Rupandehi District) | Mixed (Quantitative & Qualitative) | Provider Survey, Interviews with Women with Disabilities | Negative attitudes of providers, lack of specialized training, gender and caste-based discrimination, infrastructure inaccessibility | Positive attitudes among younger and urban providers, effective training programs for healthcare providers |

| Kassa, t. A., luck, t., bekele, a., & riedel-heller, s. G. (2016). Sexual and reproductive health of young people with disability in ethiopia: a study on knowledge, attitude and practice: a cross-sectional study | - Ethiopia (Addis Ababa) | Quantitative (Cross-Sectional) | Cross-Sectional Survey | Lack of knowledge on SRH, low perception of HIV risk, absence of family discussions | Media (radio, TV) as main sources of information |

| Rugoho, t., & maphosa, f. (2017). Challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing sexual and reproductive health in zimbabwe: the case of chitungwiza town | Zimbabwe (Chitungwiza Town) | Qualitative | Semi-Structured Interviews with 20 Women with Disabilities | Physical inaccessibility of healthcare facilities, negative provider attitudes, lack of adapted SRH information, social stigmatization, lack of inclusive policies | - Community awareness, healthcare provider training, implementation of inclusive policies |

| Burke, e., kébé, f., flink, i., van reeuwijk, m., & le may, a. (2017). A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in senegal | Senegal (Dakar Region) | Qualitative | 17 Focus Groups, 50 Interviews with Young Disabled People | Low SRH service knowledge, dependency, sexual violence, stigmatization, financial and accessibility barriers | Participatory research, recommendations for adapted and inclusive services |

| Smith, e., murray, s. F., yousafzai, a. K., & kasonka, l. (2004). Barriers to accessing safe motherhood and reproductive health services: the situation of women with disabilities in lusaka, zambia | Zambia (Lusaka) | Qualitative | 24 In-depth Interviews with Women with Disabilities + 25 Interviews with Maternity and Reproductive Healthcare Providers | Social, attitudinal, and physical obstacles, stigmatization, over-referral to distant facilities | Improved societal understanding, better communication between healthcare providers and women with disabilities |

| Mavuso, s. S., & maharaj, p. (2015). Access to sexual and reproductive health services: experiences and perspectives of persons with disabilities in durban, south africa | South Africa (Durban) | Qualitative | In-depth Interviews and Qualitative Data Analysis | Marginalization in SRH programs, negative attitudes from providers, physical and financial access difficulties | Healthcare provider training, adaptation of services to specific needs of people with disabilities |

| Bremer et al. (2009). Reproductive health experiences among women with physical disabilities in the northwest region of cameroon | Cameroon (Northwest Region) | Quantitative | Cross-Sectional Study with Structured Questionnaires | Physical inaccessibility, social stigmatization, lack of healthcare staff awareness | Infrastructure improvements, healthcare provider training, community awareness initiatives |

| Ahumuza, s. E., matovu, j. K. B., ddamulira, j. B., & muhanguzi, f. K. (2014). Challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services by people with physical disabilities in kampala, uganda | Uganda (Kampala) | Qualitative | In-depth Interviews with 40 PWDs and 10 Key Informants | Negative attitudes from providers, inaccessible infrastructure, high costs, perceptions of asexuality | Provider awareness, service adaptation, inclusion of PWDs in service planning |

| Ganle, j. K., otupiri, e., obeng, b., edusie, a. K., ankomah, a., & adanu, r. (2016). Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal healthcare services in ghana: a qualitative study | Ghana (Bosomtwe and Central Gonja Districts) | Qualitative | 72 Semi-Structured Interviews | Inaccessible infrastructure, stigmatization, high costs, social misconceptions regarding disabled women’s maternity | Service adaptation, healthcare provider training, community awareness |

| Bhattarai, s., kc saugat, p., kakchapati, s., poudel, s., baral, s. C., & marston, c. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health rights for persons with disability in nepal: a scoping review | Nepal | Scoping review | Review of 21 Documents from PubMed and Google Scholar | Insufficient inclusion in policies, lack of knowledge, negative attitudes, lack of social support | Recommendations for multifaceted measures based on further studies |

| Neupane, p., adhikari, s., khanal, s., devkota, s., sharma, m., shrestha, a., & timilsina, a. (2024). Understanding challenges and enhancing the competency of healthcare providers for disability inclusive sexual and reproductive health services in rural nepal | Nepal | Qualitative | Group Discussions and Interviews with Healthcare Providers and Disabled People | Knowledge gaps, biased perceptions, insufficient communication skills, lack of training | Inclusion of disability in medical training programs, enhancing provider competencies |

| Alemu, s. T., sendo, e. G., & negeri, h. A. (2024). A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators for women with a disability seeking sexual and reproductive health services in addis ababa, ethiopia | Ethiopia (Addis Ababa) | Qualitative | 10 In-depth Interviews + 2 Focus Groups | Negative community attitudes, organizational barriers, financial limitations, transport issues, lack of SRH program knowledge | Social support and networking, education access, positive attitudes of providers, self-confidence and assertiveness of women |

| Mekonnen, a. G., & melaku, y. A. (2022). Factors associated with access to sexual and reproductive health services among women with disabilities in sub-saharan africa: a systematic review | Sub-Saharan Africa, | Systematic Review | Review of 15 studies published between 2010 and 2021 | Key factors include socio-economic status, risky behaviors, limited access to SRH services, and associated factors such as education level, economic status, accessibility of healthcare facilities, and healthcare providers'attitudes | Recommendations include strengthening education, improving healthcare facility accessibility, and raising provider awareness |

| Shiwakoti, r., gurung, y. B., poudel, r. C., neupane, s., thapa, r. K., deuja, s., & pathak, r. S. (2021). Factors affecting utilization of sexual and reproductive health services among women with disabilities: a mixed-method cross-sectional study from ilam district, nepal | Nepal | Mixed (quantitative and qualitative) | Survey of 384 women with disabilities, multivariate statistical analysis, and qualitative interviews with women, health workers, and community leaders | Socio-economic, structural, and attitudinal barriers were identified | raising awareness among women and their families, training healthcare providers, and providing inclusive SRH services |

| Atieno f. R. (2011). Reproductive health challenges for women with physical disabilities in mombasa county | Kenya (Mombasa) | Qualitative (Exploratory Cross-Sectional) | Focus Groups, Life Stories, Key Informant Interviews | Inaccessible physical environments, negative attitudes from healthcare staff, mobility issues, lack of contraceptive and sexual education, poor communication | Community support groups, NGO involvement, provider training, accessibility improvements |

| Mukasa, grace s w m (2008)access to reproductive health services: the case of women with physical disabilities in nairobi | Kenya Nairobi | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews with women with physical disabilities | Barriers include stigma, inadequate infrastructure, high costs, and limited information | Recommendations include provider training and inclusion in policies |

| Sarah n. Muraya(2011).challenges faced by women with physical disabilities in accessing reproductive health services in nairobi county |

Kenya Nairobi |

Qualitative | In-depth interviews with 34 women with physical disabilities, thematic analysis | Barriers include inaccessible infrastructure, stigma from providers, and lack of adapted information | Recommendations include raising provider awareness, improving infrastructure, and targeted SRH education |

| Seidu et al. (2023). God is my only health insurance”: a mixed-methods study on the experiences of persons with disability in accessing sexual and reproductive health services in ghana | Ghana/ashanti | Mixed (quantitative and qualitative) | Survey of 400 individuals and 20 in-depth interviews | Barriers include inaccessible infrastructure, stigma, high costs, inadequate information, and religious faith as a substitute for social protection | Recommendations include provider training, improving physical accessibility, inclusive policies, and awareness campaigns |

| Kassa et al. (2014). Sexuality and sexual reproductive health of disabled young people in ethiopia | Ethiopia | Systematic review | Synthesis of literature on SRH and disability | Barriers include negative attitudes, limited access to contraception, and lack of dedicated policies | Recommendations include raising provider awareness and mobilizing civil society organizations |

| Mathabela, madiba & modjadji (2024).exploring barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services among adolescents and young people with physical disabilities in south africa | South Africa | Qualitative | Focus groups and thematic analysis based on the socio-ecological model | Barriers include physical obstacles, lack of SRH education, stigma, low socio-economic status, lack of family support, and negative attitudes | Recommendations include adapted education, development of youth-specific services, provider training, improving accessibility, and community awareness to reduce stigma, alongside the implementation of inclusive health policies |

| Kumi-kyereme et al. (2020).factors contributing to challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among young people with disabilities in ghana | Ghana | Quantitative | Cross-sectional survey of 2,127 young people with disabilities in 16 specialized schools | Barriers include high healthcare costs, physical obstacles, and communication problems | Recommendations include training health personnel in sign language and Braille, and fostering collaboration between health and education ministries |

| Kazembe et al.(2022). Experiences of women with physical disabilities accessing prenatal care in low- and middle-income countries | Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), | Integrative Review | Analysis of 11 studies on prenatal care for women with physical disabilities | Barriers include limited resources, lack of healthcare provider training, low awareness, and public stigma | Recommendations include provider training, infrastructure improvement, community awareness, and inclusive policies |

| Nguyen et al. (2019).maternal healthcare experiences of and challenges for women with physical disabilities in low and middle-income countries: a review of qualitative evidence | Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), | Global Review | Qualitative review of 15 studies | Barriers include provider attitudes, structural barriers, and exclusion from policies | Recommendations include strengthening empathy, and integrating inclusive norms in prenatal care |

| Tanabe et al.(2015) Intersecting Sexual and Reproductive Health and Disability in Humanitarian Settings: Risks, Needs, and Capacities of Refugees with Disabilities in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda | Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda | Participatory qualitative research | Focus groups and interviews with disabled refugees | Barriers include discrimination from providers, disrespect, exposure to sexual violence, and low understanding of SRH rights | Recommendations include provider training, empowering disabled refugees, and recognizing SRH rights |

Although the contexts differ, including rural and urban environments, as well as English- and French-speaking countries, the findings consistently point to the complex, intertwined barriers that hinder access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for women with motor disabilities.

These barriers were organized into five broad categories: physical, social, institutional, economic, and informational, helping to highlight the shared patterns across the various regions.

Identified barriers

Physical and logistical challenges

Studies conducted in Cameroon [8, 38], Uganda [36, 46], Kenya [30], and Zimbabwe [28, 47] reveal that healthcare infrastructures often lack accessible features, such as ramps or adapted examination equipment (e.g., adjustable beds, transfer devices), severely limiting the movement of patients with motor disabilities within facilities [27, 31]. Transportation difficulties to reach health services were also reported [26, 36].

Social and attitudinal barriers

Several researchers, including Ganle et al. in Ghana [48–50], Devkota et al. in Nepal [39], and Smith et al. in Zambia [37, 51, 52], documented discriminatory attitudes from healthcare providers. Patronizing or exclusionary behaviors [41, 53]were found to reinforce the sense of exclusion experienced by these women. Stigmatizing perceptions, viewing women with disabilities as asexual or unfit for motherhood and family life, also emerged as major barriers to service access [52, 54, 55]. Furthermore, an increased risk of sexual violence was noted in vulnerable contexts [43, 56].

Systemic and provider-level

Research from Morocco [19, 20, 57, 58], Senegal [32, 59], and Ghana [23, 60]emphasized the lack of inclusive national policies addressing disability within SRH programs. Furthermore, there was a significant shortfall in specialized training for healthcare providers to respond adequately to the needs of women with disabilities [39, 41, 53].

Economic constraints

Financial barriers were a recurrent theme, including costs related to consultations, medical tests, and transportation, as well as limited access to health insurance schemes [61]. Studies by Seidu et al. [23]and Soule & Sonko [32]particularly noted the heightened financial dependency of women with disabilities on their families or partners.

Informational and communication gaps

The unavailability of accessible information, such as materials in braille or the provision of sign language interpreters, was highlighted as a significant impediment in studies conducted in Ethiopia [26] and South Africa [35].

Facilitators identified

Several measures were suggested to improve access.

Healthcare provider training

Devkota et al. [39]and Neupane et al. [41]emphasized the importance of including disability-specific content in both pre-service education and ongoing professional development for healthcare staff.

Adaptation of SRH Services

Redesigning healthcare services to better meet the needs of women with disabilities was another key recommendation, as proposed by Alemu et al. [25–27], who suggested measures such as dedicated service hours, mobile clinics, and home-based care units.

Community mobilization

Grassroots initiatives led by peer networks and associations, particularly in Morocco, Senegal, and South Africa, demonstrated the benefits of community advocacy and support groups in promoting SRH rights for women with disabilities [19, 33, 62, 63].

Inclusive public policies

Finally, Ganle and Kazembe [45, 62] advocated for the explicit integration of disability issues into national reproductive health strategies, supported by dedicated budgets and monitoring frameworks.

Discussion

Our synthesis underscores that in low- and middle-income African countries, women with motor disabilities face systemic and interconnected exclusion from sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. The barriers identified are not isolated or sector-specific; rather, they are interwoven across structural, institutional, interpersonal, and individual levels, reflecting deeply entrenched patterns of marginalization.

At the structural and institutional levels, the absence of national disability-inclusive policies and the lack of adapted infrastructures create environments where accessibility is physically and procedurally limited. For example, studies from Ethiopia, Uganda, and rural Kenya report the near-total absence of accessible facilities and trained personnel, whereas more urbanized or higher-resource settings, such as South Africa and Ghana, reveal attitudinal and institutional disconnections despite the availability of services.

These institutional gaps contribute to provider unpreparedness and discriminatory attitudes, which in turn reinforce societal stigmas around the sexuality, autonomy, and reproductive rights of women with disabilities. For instance, in Ghana, disability-related stigma fuels economic dependency, which significantly limits women’s ability to seek SRH services. This cyclical dynamic where institutional neglect breeds provider-level bias and social exclusion was a recurring pattern across the reviewed studies.

At the interpersonal and individual levels, economic constraints such as transportation costs, unemployment, or loss of family income intersect with physical barriers, including inaccessible clinics or lack of adapted equipment. One study from South Africa reported that women forwent antenatal care entirely due to a combined effect of financial hardship and lack of wheelchair ramps [34]. Similarly, in Morocco and Senegal, inadequate health communication and inaccessible information formats emerged as hidden but powerful barriers.

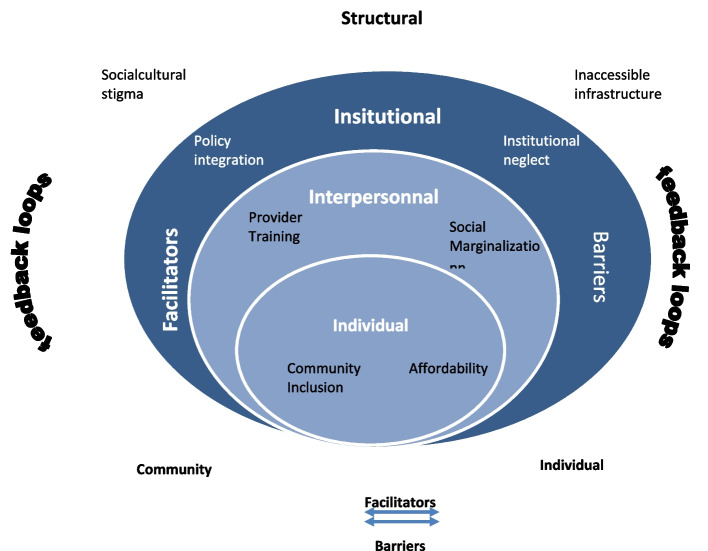

These findings demonstrate a systems-level feedback loop, where constraints at one level exacerbate vulnerabilities at another. For example, institutional inaction perpetuates interpersonal stigma, which discourages service-seeking, ultimately reproducing structural exclusion. These interdependencies are explicitly represented in our conceptual framework (Fig. 2), which shows how structural, institutional, interpersonal, and individual-level barriers interlock. It also illustrates how targeted facilitators such as community mobilization, inclusive policy design, and local partnerships can disrupt these exclusionary cycles.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual Framework of dynamic intercations of barriers and facilitors

Despite this entrenched marginalization, some promising local initiatives signal the potential for positive change. For instance, studies in Mombasa [29]and the Ashanti region [64] highlight successful community engagement, integration of disability into local health strategies, and partnerships with NGOs to improve outreach and inclusion. These examples point to entry points for multisectoral intervention, particularly when strategies are co-designed with the affected communities.

Comparisons with broader reviews by Nguyen et al. [44, 65, 66] and Mekonnen & Melaku [67] further reinforce the universality of these findings. These authors report similar systemic exclusions in other low- and middle-income settings, confirming that the challenges identified in our synthesis are part of a broader global pattern of neglect.

Based on this synthesis, we developed the conceptual framework (Fig. 2) to model the dynamic interactions of barriers and facilitators. The framework illustrates that access to SRH services is shaped by multi-layered and mutually reinforcing factors, where progress at one level (e.g., policy integration) can positively influence outcomes at others (e.g., provider attitudes or community inclusion). It also reveals feedback loops, for example, how institutional reforms can improve provider training, which in turn fosters more respectful and inclusive care.

By embedding this interpretative lens, our discussion moves beyond description to highlight the systemic nature of exclusion and to identify actionable entry points for inclusive and integrated SRH programming. The findings call for comprehensive, multisectoral approaches that simultaneously address infrastructure, workforce capacity, affordability, sociocultural norms, and legal protection. Strengthening institutional frameworks in particular may have ripple effects across all levels of the system, facilitating more equitable access for women with motor disabilities.

Limitations.

This review presents several methodological limitations. First, the included studies vary widely in design (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and reviews), which limited our ability to perform comparative statistical analyses or draw generalizable conclusions. Second, there is a notable urban bias, as the majority of studies were conducted in capital cities or major urban centers. This limits the applicability of findings to rural or remote settings where barriers may differ significantly. Third, there is a limited representation of adolescents and young women, despite their distinct SRH needs. Finally, although grey literature was consulted, the synthesis was restricted to peer-reviewed publications, which may have excluded valuable non-indexed reports or locally published studies. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings and developing policy or programmatic recommendations.

Conclusion

By synthesizing studies conducted across eleven African countries and a few comparable contexts, this review reveals the systemic exclusion of women with motor disabilities from sexual and reproductive health services. The physical, social, institutional, economic, and informational barriers combine to restrict their access to essential care. However, local experiences demonstrate that participatory approaches, targeted training for providers, and infrastructure adaptations can lead to tangible improvements. To ensure equitable care, it is crucial to embed disability inclusivity into national reproductive health policies, strengthen financial and legislative coverage, and actively involve the women affected in the design and evaluation of services. By tackling these factors concurrently, low- and middle-income countries can advance toward equitable access and uphold the sexual and reproductive rights of all individuals.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

Firdaous Zekaoui (FZ) designed the systematic review, developed the research question according to the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) model and wrote the protocol registered in PROSPERO. She directed the literature search, coordinated the selection of studies, carried out the extraction and thematic analysis of the data, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. RA contributed to the literature search strategy, participated in the selection of studies and the methodological quality assessment of the included articles. HB participated in data extraction and cross-validation, and provided substantial critical revision of the manuscript to improve its scientific quality. SH supervised the analysis of the results, validated the thematic organisation of the synthesis, and contributed to the interpretation of the results and the final proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

All the authors state that they have not received any funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.M E María del Carmen Malbrán, del Carmen Malbrán MEM. World Report on Disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2011;8:290–290. 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00320.x.

- 2.prue. The Guttmacher–Lancet Commission on sexual and reproductive health and rights: how does Australia measure up? Family Planning NSW 2019. https://www.fpnsw.org.au/guttmacher%E2%80%93lancet-commission-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights-how-does-australia-measure (accessed September 7, 2023).

- 3.Rapport mondial sur l’équité en santé pour les personnes handicapées : Résumé d’orientation n.d.

- 4.Member States, Member States. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol 2012.

- 5.Accelerating Progress in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Eastern Europe and Central Asia – Reflecting on ICPD 25 Nairobi Summit - ScienceDirect n.d. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301211519306086 (accessed April 25, 2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Arne Henning Eide, Eide AH, Hasheem Mannan, Mannan H, Mustafa Khogali, Khogali M, Mustafa Khogali, Gert Van Rooy, Van Rooy G, Leslie Swartz, Swartz L, Alister Munthali, Munthali A, Munthali A, Karl-Gerhard Hem, Hem K-G, Karl Gerhard Hem, Malcolm MacLachlan, MacLachlan M, Karin Dyrstad, Dyrstad K. Perceived Barriers for Accessing Health Services among Individuals with Disability in Four African Countries. PLOS ONE 2015;10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mark T. Carew, Carew MT, Stine Hellum Braathen, Braathen SH, Xanthe Hunt, Hunt X, Leslie Swartz, Swartz L, Poul Rohleder, Rohleder P. Predictors of negative beliefs toward the sexual rights and perceived sexual healthcare needs of people with physical disabilities in South Africa. Disability and Rehabilitation 2020;42:3664–72. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1608323. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.DeBeaudrap P, Mouté C, Pasquier E, Mac-Seing M, Mukangwije PU, Beninguisse G. Disability and Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Cameroon: A Mediation Analysis of the Role of Socioeconomic Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019;16:null. 10.3390/ijerph16030417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.How to Write a Systematic Review - Joshua D. Harris, Carmen E. Quatman, M.M. Manring, Robert A. Siston, David C. Flanigan, 2014 n.d. 10.1177/0363546513497567 (accessed January 16, 2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review. 10.1177/014107680309600304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sohrabi C, Franchi T, Mathew G, Kerwan A, Nicola M, Griffin M, Agha M, Agha R. PRISMA 2020 statement: What’s new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int J Surg. 2021;88: 105918. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PROSPERO: An International Register of Systematic Review Protocols: Medical Reference Services Quarterly: Vol 38 , No 2 - Get Access n.d. 10.1080/02763869.2019.1588072 (accessed January 19, 2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Amoh GKA, Addo AK, Odiase O, Tahir P, Getahun M, Aborigo RA, Essuman A, Yawson AE, Essuman VA, Afulani PA. Person-centred care (PCC) research in Ghana: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2024;14: e079227. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) n.d. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed June 28, 2025).

- 15.A Multidimensional Framework for Measuring Access | Request PDF. ResearchGate 2015.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337303546_A_Multidimensional_Framework_for_Measuring_Access (accessed June 28, 2025).

- 16.Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2013;12:18. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences. 2020. 10.1177/2632084320947559. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdessamad Dialmy. Les Besoins En Sante Sexuelle Et Reproductive Des Personnes En Situation De Handicap AU Maroc. 2014.

- 20.André Dupras. La santé sexuelle et reproductive des personnes en situation de handicap. Analyse de la situation et recommandation, Rapport soumis à l’UNFPA Maroc et ses partenaires, 2011. 2011.

- 21.Perception de la santé sexuelle et reproductive chez les personnes en situation de handicap(s) physique(s) et/ou sensoriel(s) rabat sale kenitra, marrakech safi, fes meknes et l’oriental. cnmh et FNUAP; 2019.

- 22.Ganle JK, Baatiema L, Quansah R, Danso-Appiah A. Barriers facing persons with disability in accessing sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0238585. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdul‐Aziz Seidu, Bunmi S. Malau‐Aduli, Kristin McBain-Rigg, A.E.O. Malau‐Aduli, Theophilus I. Emeto. “God is my only health insurance”: a mixed-methods study on the experiences of persons with disability in accessing sexual and reproductive health services in Ghana. Frontiers in Public Health 2023;11. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1232046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kumi-Kyereme A, Seidu A, Darteh EKM. Factors Contributing to Challenges in Accessing Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Among Young People with Disabilities in Ghana. Global Social Welfare. 2020;8:1–10. 10.1007/s40609-020-00169-1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tigist Alemu Kassa, Kassa TA, Tigist Alemu Kassa, Tobias Luck, Luck T, Samuel Kinde Birru, Birru SK, Steffi G. Riedel‐Heller, Riedel-Heller SG. Sexuality and sexual reproductive health of disabled young people in Ethiopia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2014;41:583–8. 10.1097/olq.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sewnet Alemu, E. Sendo, H. A. Negeri. A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators for women with a disability seeking sexual and reproductive health services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reproductive Health 2024. 10.1186/s12978-024-01880-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Tigist Alemu Kassa, Kassa TA, Tigist Alemu Kassa, Tobias Luck, Luck T, Assegedech Bekele, Bekele A, Steffi G. Riedel‐Heller, Riedel-Heller SG. Sexual and reproductive health of young people with disability in Ethiopia: a study on knowledge, attitude and practice: a cross-sectional study. Globalization and Health 2016;12:5–5. 10.1186/s12992-016-0142-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Rugoho T, Maphosa F. Challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing sexual and reproductive health in Zimbabwe: The case of Chitungwiza town. African Journal of Disability 2017;6:null. 10.4102/ajod.v6i0.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Atieno FR. Reproductive health challenges for women with physical disabilities in Mombasa County, 2011.

- 30.Sarah N Muraya, Muraya SN. Challenges faced by women with physical disabilites in accessing reproductive health services in Nairobi County 2011.

- 31.Grace S W M Mukasa, Mukasa GSWM. Access to reproductive health services: the case of women with physical disabilities in Nairobi 2008.

- 32.Olivia Soule,a* Diatou Sonko. Examining access to sexual and reproductive health services andinformation for young women with disabilities in Senegal: aqualitative study n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Burke E, Kébé F, Flink I, van Reeuwijk M, le May A. A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25:43–54. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mavuso S, Maharaj P. Access to sexual and reproductive health services: Experiences and perspectives of persons with disabilities in Durban. South Africa Agenda. 2015;29:79–88. 10.1080/10130950.2015.1043713. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathabela B, Madiba S, Modjadji P. Exploring Barriers to Accessing Sexual and Reproductive Health Services among Adolescents and Young People with Physical Disabilities in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024;21:null. 10.3390/ijerph21020199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ahumuza SE, Matovu J, Ddamulira J, Muhanguzi F. Challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health services by people with physical disabilities in Kampala. Uganda Reproductive Health. 2014;11:59–59. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erskine R. Smith, Smith EN, Susan Murray, Murray SF, Aisha K. Yousafzai, Yousafzai AK, Lackson Kasonka, Kasonka L. Barriers to accessing safe motherhood and reproductive health services: the situation of women with disabilities in Lusaka Zambia. Disability and Rehabilitation 2004;26:121–7. 10.1080/09638280310001629651. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Bremer K, Cockburn L, Ruth A. Reproductive health experiences among women with physical disabilities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;108:211–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devkota HR, Murray E, Kett M, Groce N. Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal. Reproductive Health 2017;14:null. 10.1186/s12978-017-0330-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Sanju Bhattarai, Saugat Pratap KC, Sampurna Kakchapati, Shraddha Poudel, Sushil Baral, Cicely Marston. Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health rights for Persons with Disability in Nepal: a scoping review. medRxiv 2023. 10.1101/2023.04.19.23288803.

- 41.Neupane P, Adhikari S, Khanal S, Devkota S, Sharma M, Shrestha A, Timilsina A. Understanding challenges and enhancing the competency of healthcare providers for disability inclusive sexual and reproductive health services in rural Nepal. PLoS ONE. 2024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0311944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rupa Shiwakoti, Shiwakoti R, Yogendra Bahadur Gurung, Gurung YB, Yogendra Bahadur Gurung, Yogendra Bahadur Gurung, Ram Sharan Pathak, Pathak RS, Ram C. Poudel, Ram Chandra Poudel, Poudel RC, Ram Chandra Poudel, Ram Chandra Poudel, Sandesh Neupane, Neupane S, Ram Krishna Thapa, Thapa RK, Sailendra Deuja, Deuja S. Factors affecting utilization of sexual and reproductive health services among women with disabilities- A mixed-method cross-sectional study from Ilam district, Nepal. BMC Health Services Research 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-131588/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Mihoko Tanabe, Tanabe M, Yusrah Nagujjah, Nagujjah Y, Nirmal Rimal, Rimal N, Florah Bukania, Bukania F, Sandra Krause, Krause S. Intersecting Sexual and Reproductive Health and Disability in Humanitarian Settings: Risks, Needs, and Capacities of Refugees with Disabilities in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda. Sexuality and Disability. 2015;33:411–27. 10.1007/s11195-015-9419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Nguyen TV, King J, Edwards N, Pham CT, Dunne M. Maternal Healthcare Experiences of and Challenges for Women with Physical Disabilities in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Review of Qualitative Evidence. Sex Disabil. 2019;37:175–201. 10.1007/s11195-019-09564-9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazembe A, Simwaka A, Dougherty KK, Petross C, Kafulafula U, Chakhame B, Chodzaza E, Chisuse I, Kamanga M, Sun C, George M. Experiences of women with physical disabilities accessing prenatal care in low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nursing 2022;null:null. 10.1111/phn.13087. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Moses Mulumba, Mulumba M, Juliana Nantaba, Nantaba J, Claire E Brolan, Brolan CE, Ana Lorena Ruano, Ruano AL, Katie Brooker, Brooker K, Rachel Hammonds, R Hammonds, Hammonds R. Perceptions and experiences of access to public healthcare by people with disabilities and older people in Uganda. International Journal for Equity in Health 2014;13:76–76. 10.1186/s12939-014-0076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Christine Peta, Peta C. Disability is not asexuality: the childbearing experiences and aspirations of women with disability in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters 2017;25:10–9. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1331684. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Ganle J, Baatiema L, Quansah R, Danso-Appiah A. Barriers facing persons with disability in accessing sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020;15:null. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Ganle J, Otupiri E, Obeng B, Edusie AK, Ankomah A, Adanu R. Challenges Women with Disability Face in Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services in Ghana: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2016;11:null. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.John Kuumuori Ganle, Ganle JK, Easmon Otupiri, Otupiri E, Bernard Obeng, Obeng B, Anthony Kwaku Edusie, Edusie AK, Augustine Ankomah, Ankomah A, Richard Adanu, Adanu R. Challenges Women with Disability Face in Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services in Ghana: A Qualitative Study. PLOS ONE 2016;11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Janet Parsons, Parsons JA, Virginia Bond, Bond V, Stephanie Nixon, Nixon SA. “Are We Not Human?” Stories of Stigma, Disability and HIV from Lusaka, Zambia and Their Implications for Access to Health Services. PLOS ONE 2015;10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Smith EN, Murray S, Yousafzai A, Kasonka L. Barriers to accessing safe motherhood and reproductive health services: the situation of women with disabilities in Lusaka. Zambia Disability and Rehabilitation. 2004;26:121–7. 10.1080/09638280310001629651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eric Badu, Badu E, Maxwell Peprah Opoku, Opoku MP, Seth Christopher Yaw Appiah, Appiah SCY. Attitudes of health service providers: The perspective of people with disabilities in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. African Journal of Disability 2016;5:181–181. 10.4102/ajod.v5i1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Hridaya Raj Devkota, Devkota HR, Maria Kett, Maria Kett, Kett M, Nora Groce, Groce N. Societal attitude and behaviours towards women with disabilities in rural Nepal: pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2019;19:20–20. 10.1186/s12884-019-2171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Belaynesh Tefera, Tefera B, Marloes van Engen, van Engen ML, Jac van der Klink, van der Klink JJL, A. Schippers, Schippers A. The grace of motherhood: disabled women contending with societal denial of intimacy, pregnancy, and motherhood in Ethiopia. Disability & Society 2017;32:1510–33. 10.1080/09687599.2017.1361385.

- 56.Maxwell Peprah Opoku, Opoku MP, Nicole Huyser, Huyser N, Wisdom Kwadwo Mprah, Mprah WK, Eric Badu, Alupo BA, Beatrice Atim Alupo, Badu E. Sexual violence against women with disabilities in Ghana: accounts of women with disabilities from Ashanti region. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development 2016;27:91–111. 10.5463/dcid.v27i2.500.

- 57.Assarag B, Sanae EO, Rachid B. Priorities for sexual and reproductive health in Morocco as part of universal health coverage: maternal health as a national priority. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2020;28:1845426. 10.1080/26410397.2020.1845426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.G Feather 2020 Feather G Proactive versus Reactive Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights: A Comparative Case Study Analysis of Morocco and Tunisia 29 76 89 10.3224/feminapolitica.v29i2.07

- 59.Eva Burke, Burke E, Eva Burke, Fatou Kébé, Kébé F, Ilse Flink, Flink I, Miranda van Reeuwijk, van Reeuwijk M, Alex le May, le May A. A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reproductive Health Matters 2017;25:43–54. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.A. Seidu, B. Malau-Aduli, Kristin McBain-Rigg, Aduli E. O. Malau-Aduli, T. Emeto. “Nothing about us, without us”: stakeholders perceptions on strategies to improve persons with disabilities’ sexual and reproductive health outcomes in Ghana. International Journal for Equity in Health 2024. 10.1186/s12939-024-02269-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Eric Badu, Badu E, Maxwell Peprah Opoku, Opoku MP, Seth Christopher Yaw Appiah, Appiah SCY, Elvis Agyei‐Okyere, Agyei-Okyere E. Financial Access to Healthcare among Persons with Disabilities in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development 2015;26:47–64. 10.5463/dcid.v26i2.402.

- 62.Ganle J, Ofori C, Dery SKK. Testing the effect of an integrated-intervention to promote access to sexual and reproductive healthcare and rights among women with disabilities in Ghana: a quasi-experimental study protocol. Reproductive Health 2021;18:null. 10.1186/s12978-021-01253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Hameed S, Maddams A, Lowe H, Davies L, Khosla R, Shakespeare T. From words to actions: systematic review of interventions to promote sexual and reproductive health of persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5: e002903. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.A. Seidu, B. Malau-Aduli, Kristin McBain-Rigg, Aduli E. O. Malau-Aduli, T. Emeto. Sexual lives and reproductive health outcomes among persons with disabilities: a mixed-methods study in two districts of Ghana. Reproductive Health 2024. 10.1186/s12978-024-01810-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.An Nguyen, Nguyen TTA, Pranee Liamputtong, Liamputtong P, Melissa Monfries, Monfries M. Reproductive and Sexual Health of People with Physical Disabilities: A Metasynthesis. Sexuality and Disability 2016;34:3–26. 10.1007/s11195-015-9425-5.

- 66.Nguyen A. Challenges for Women with Disabilities Accessing Reproductive Health Care Around the World: A Scoping Review. Sex Disabil. 2020;38:1–18. 10.1007/s11195-020-09630-7. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mekonnen A, Bayleyegn AD, Aynalem Y, Adane T, Muluneh M, Asefa M. Level of knowledge, attitude, and practice of family planning and associated factors among disabled persons, north-shewa zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine 2020;5:null. 10.1186/s40834-020-00111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.