Abstract

This study reports for the first time on the application of microwave (MW) heating under ambient pressure reflux conditions to intensify the transesterification reaction of ethylene glycol with dimethyl carbonate (DMC) for the synthesis of ethylene carbonate (EC), a relevant industrial compound for polycarbonate products, lubricants and li‐ion batteries. Conventional heating (CH) methods often require high‐temperature autoclave systems to achieve elevated temperatures and suppress vaporization of the reactant DMC (bp ≈ 90 °C). However, these systems usually entail extended reaction times and significant process cost. It is demonstrated that application of the MW‐assisted reflux technique to the aforementioned transesterification reaction intensifies the energy transfer rate to the reactor by leveraging on the polarity of the reactive mixture and enhances phase transition of the lowest boiling point by‐product (MeOH), thereby achieving 81% EC yield in half the time required under CH reflux conditions to reach only 52% EC yield. Further, compared to CH, MW heating enables 20‐fold lower catalyst loading for comparable EC yields, 9‐fold decrease in energy consumption per mole EC, and 92% reduction in energy consumption during the mixture preheating stage.

Keywords: ethylene carbonate, microwaves, process intensification, transesterification

Microwave‐assisted heating under ambient pressure reflux conditions is applied to intensify the transesterification of ethylene glycol with dimethyl carbonate. The proposed method enhances energy efficiency and product yield compared to conventional heating, enabling lower catalyst loading, reduced process time, and significantly decreased energy consumption, demonstrating its potential as a sustainable alternative for ethylene carbonate synthesis.

1. Introduction

Cyclic carbonates, particularly five‐membered ones, such as ethylene carbonate (EC) and propylene carbonate (PC), have become increasingly significant in industrial applications due to their unique physicochemical properties, including high boiling points, low toxicity, and excellent biodegradability. EC in particular is widely utilized as electrolyte in lithium‐ion (Li‐ion) batteries, as industrial lubricant, and as precursor for the green manufacturing of aromatic bisphenol A‐based polycarbonates.[ 1 , 2 ] Given these diverse applications, the global demand for EC is rapidly expanding. This growth is particularly evident in the electronics and automotive sectors, where the increasing focus on electric vehicles and sustainable energy storage solutions creates the need for more efficient and eco‐friendly materials like EC.[ 2 ]

The industrial synthesis of EC primarily involves two methods: the phosgenation of ethylene glycol (EG) and the cycloaddition of ethylene oxide (EO) with carbon dioxide (CO2). The phosgenation method, while effective, uses toxic phosgene, thereby raising environmental and safety concerns, such as equipment corrosion and harmful byproduct formation. In contrast, the cycloaddition method, which couples EO with CO2, is more widely adopted due to its relatively greener profile. However, this process also presents challenges, as EO is a highly toxic, flammable, and corrosive gas at room temperature, requiring stringent safety measures. The method further demands high‐pressure conditions (40–60 bar) and relies on petroleum‐derived EO, complicating sustainability efforts.[ 3 , 4 ] These factors highlight the critical need for developing greener and more sustainable routes to produce EC.

In response to these challenges, the pursuit of alternative methods to synthesize EC has gained momentum, driven by the need to overcome the limitations of current industrial processes, particularly the reliance on toxic and petroleum‐derived feedstocks. Promising alternative routes include the transesterification of dimethyl carbonate (DMC) with EG, alcoholysis of urea with EG, and direct carboxylation of EG. These methods offer the advantage of utilizing EG, which can be derived from renewable sources, such as glycerol (Gly), a byproduct of biodiesel production along with the utilization of CO2 directly or indirectly, by transforming it to DMC and urea.[ 5 , 6 ] Recently, Ng et al. applied the “three‐parameter difference” method introduced by Song et al.[ 7 ] to provide a rational basis for the quantitative assessment of the three alternative EC synthesis routes.[ 4 ] This method evaluated the overall thermodynamic feasibility, greenness, and safety of the chemical reactions using Gibbs free energy, atom efficiency, and an inherent safety index. Based on these criteria, the transesterification route emerges as the most promising one.

The transesterification of DMC with EG to produce EC is a mildly endothermic reaction (ΔH = 7.18 kJ mol−1),[ 8 ] requiring elevated temperatures to achieve high yields. However, conventional approaches often rely on high‐pressure autoclave systems to mitigate the volatility of DMC (boiling point ≈90 °C), which significantly reduces the mixture's boiling point and thus the ability to operate at elevated temperature regimes. While these systems enable effective reaction progression, they are associated with increased energy demand, operational costs, and safety requirements, which limit their feasibility for sustainable and cost‐effective production.[ 9 ] Aside from the process conditions, catalyst selection plays a pivotal role in optimizing reaction efficiency and selectivity. Basic heterogeneous catalysts, such as calcium oxide (CaO), hydrotalcites, and mixed metal oxides, have demonstrated high activity and ease of recovery, making them suitable for industrial applications.[ 10 ] Recent studies have underscored the critical role of reaction temperature in conjunction with continuous methanol (MeOH) removal in shifting the reaction equilibrium toward enhanced EC formation. For instance, Selva et al. demonstrated that using a basic ionic liquid catalyst at a loading of 4% w/wEG, resulted in EC yields of 73% and 88% after 4 h of reflux conditions at 90 °C and autoclave conditions at 120 °C, respectively. Notably, under reflux conditions at 90 °C, continuous MeOH removal via distillation increased the EC yield from 73% to 94%, surpassing the yield obtained at 120 °C under high‐pressure autoclave conditions.[ 11 ] These findings suggest that with suitable catalyst selection continuous MeOH byproduct removal has the potential to act as the dominant driving force determining EC yield, as compared to elevated reaction temperatures or high‐pressure conditions.

Building on the importance of MeOH removal, microwaves (MWs) have emerged as a promising tool to facilitate separation of polar compounds from polar/nonpolar azeotropic systems and for intensification of reaction kinetics by selectively removing polar byproducts from reaction mixtures. This enhancement is attributed to the microwave‐induced relative volatility change, a phenomenon first introduced by Altman et al.[ 12 ] To verify this mechanism, Gao et al. used a customized vapor‐liquid equilibrium (VLE) device to study the ethanol (polar)/benzene (nonpolar) system, demonstrating that MWs selectively heat the polar ethanol, transferring it to the vapor phase and altering the system's VLE.[ 13 ] Furthermore, in the reactive system of the ketalization of glycerol, Filho et al. showed that due to the strong interaction of acetone and water with MW irradiation, a change in the VLE occurs increasing the concentration of acetone/water in the vapor phase. Coupling this with the addition of anhydrous acetone results in intensification of the solketal production.[ 14 ] These studies underline the potential of microwave heating (MWH) to leverage selective heating and phase‐change mechanisms for reaction intensification in reactive mixtures where a polar–nonpolar relationship exists between the system products and reactants respectively.

Based on these observations, MWH may also have the potential to intensify reactive systems involving polar reactants–polar products, where one or more of the products have a low boiling point. This case involves 1) the presence of polar compounds on both sides of the reaction, facilitating effective energy dissipation in the liquid mixture and increase in the amount of liquid vaporized as the system passes through different dynamic equilibrium states, and 2) the transfer of the low boiling point product(s) to the vapor phase, leading to enhanced reactants conversion and product yield. In this context, the present study explores the potential of MWH to intensify the ambient pressure batch transesterification of EG and DMC toward EC and MeOH compared to conventional heating (CH). The reaction was investigated under two distinct operating regimes: 1) isothermal operation at 60 °C, where all components remained in the liquid phase, and 2) reflux operation at ≈90 °C, leveraging MeOH evaporation to enhance product formation. The study systematically assesses the influence of MWH on key performance metrics, including EG conversion, EC yield, catalyst loading requirements, process time, and energy consumption. By focusing on these aspects, the study aims not only to present the merits of MW application on enablement of EC synthesis under mild operating conditions but also to indicate its broader potential for intensification of equilibrium‐limited reactions involving low‐boiling polar product compounds.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

EG (>99%) was kindly provided by Megara Resins S.A. DMC (99% purity), CaO (99.95% purity on metals basis), used as the reaction's catalyst, and dimethyl sulfoxide‐d6 (DMSO‐d6, ≥99.5% purity), used as NMR solvent, were purchased from Thermo Scientific. Methanol (MeOH, ≥99.8% purity), potassium bromide (KBr, spectroscopy grade), and diethyl ether (Et2O, ≥99% purity) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Dichloromethane (DCM, ≥99.9% purity) was supplied by Honeywell and was used as a solvent for the gas chromatography while ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm) was used as a solvent and mobile phase for high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses. Nitrogen (N2, N50 purity), which was used as purge gas, was supplied by the SOL group. All chemicals were used without further purification.

2.2. Apparatus and Synthesis Procedure

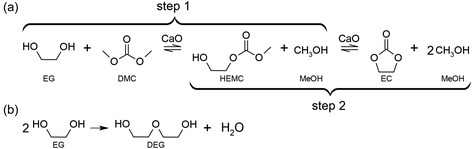

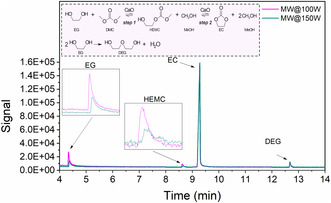

The global transesterification reaction between EG and DMC is presented in Figure 1a. CaO was selected as the catalyst based on the findings of Ochoa‐Gómez et al. the authors demonstrated high conversions and yields in the transesterification of glycerol using CaO, while industrial feasibility criteria were also met.[ 15 ] The reaction is reversible and leads to the production of EC, as the desired product, and MeOH as a byproduct. It includes the synthesis of hydroxyethyl methyl carbonate (HEMC) as an intermediate product (step 1), which further transforms to EC (step 2). Additionally, the self‐condensation of EG (Figure 1b) may take place at temperatures around ≈90 °C forming diethylene glycol (DEG) and H2O as side products.[ 16 , 17 ]

Figure 1.

a) Mechanism of the transesterification reaction between EG and DMC to produce EC and MeOH (main reaction). b) Self‐condensation of EG that forms DEG and H2O (side reaction).

2.2.1. CH

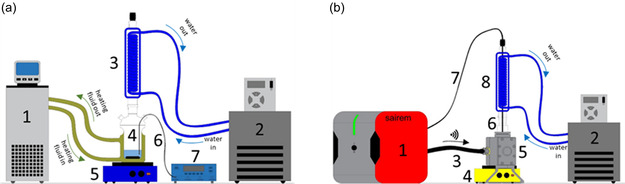

CH experiments were conducted with the setup depicted in Figure 2a. The setup comprised a 100 mL jacketed reactor with a condenser on top connected to an oil and water bath, respectively. Stirring of the reaction mixture was carried out using a magnetic stirring plate. The reaction temperature was measured using a fiber optic (FO) sensor (CEM Corporation) connected to a temperature multichannel instrument from FISO Technologies Inc.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup used for a) conventional heating: a jacketed reactor (4) with a condenser (3), placed on top of a magnetic/heating plate (5), is connected to an oil bath (1) and a water bath (2). The temperature of the reaction was measured with a fiber optic (6) connected to a temperature measurement instrument (7). b) Microwave heating: a 200 W solid state generator (1) is connected via a coaxial cable (3) to a MW cavity (5), which contains the reactor (6)—with a condenser on top (8)—connected to a water bath (2) and a magnetic plate (4) under the cavity. A fiber optic (7) is connected to the generator for temperature monitoring.

Approximately 15 g of EG were placed in the reactor and DMC was added afterward at a molar ratio (DMC:EG) of either 1.12:1 or 2.24:1. A gas line was used to purge N2 inside the reactor to create an inert atmosphere. Once the EG/DMC mixture reached the desired temperature, the purge line was removed and CaO was added at the selected concentration. A sample was retrieved at the starting temperature before adding the catalyst (CaO), to check whether there was any reaction progress.

2.2.2. MWH

The MWH experimental setup is shown in Figure 2b. The 100 mL reactor was inserted in the MW cavity, which was connected via a coaxial cable to a solid‐state generator (SSG) from Sairem Corporation (France). The SSG has a maximum output power of 200 W adjustable in 1 W steps and works at 2.45 GHz. The MW cavity is equipped with an adjustable stub for impedance matching. A condenser connected to a water bath is placed on top of the reactor, while a stirring plate beneath the MW cavity ensures adequate mixing of the liquid solution. The reaction temperature is measured with an FO from OSENSA Innovations Corporation (Canada).

The reactants, namely, EG and DMC, were introduced into the reactor at the proportional molar ratio (DMC:EG) of either 1.12:1 or 2.24:1 in correspondence to CH experiments. Like CH experiments, a N2 purge line is used to establish an inert atmosphere inside the reactor. Once the targeted reaction temperature is achieved by the selected applied output power, the purge line is removed, and the catalyst is added to the reaction mixture.

For both heating modes, the actual energy consumption was measured by a UT230B series power meter (Uni‐Trend Technology, China).

2.3. Postreaction Procedure

After completion of the reaction, the catalyst was separated via vacuum filtration. The unreacted DMC and formed MeOH were evaporated using a rotary evaporator leading to the residual reaction mixture. A sample was taken from the residual reaction mixture to be analyzed for unreacted EG and produced EC using gas chromatography. The EG conversion and EC yield were determined using Equation (1) and (2), respectively:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where is the initial mass of EG (g), is the total mass of the residual reaction mixture (g), and and are the concentrations (wt%) of EG and EC, respectively, in the residual reaction mixture. and are the molecular weights of EG (62.07 g mol−1) and EC (88.06 g mol−1), respectively.

The residual reaction mixture was washed with cold diethyl ether and kept at −10 °C for 48 h. EC was precipitated and separated from the solution under vacuum filtration.

To evaluate the reusability of CaO, the filtered catalyst was calcinated at 600 °C for 14 h and reused in two consecutive reaction cycles, with each reuse following the same recovery and post treatment process.

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Gas Chromatography (GC)

A Hewlett Packard (HP) gas chromatograph (HP 6890) equipped with a mass spectrometry detector (HP 5973) and an HP‐5MS column (Agilent Technologies) was used for quantitative analysis with DCM as the sample preparation solvent. The chromatograms obtained were analyzed with the HP Chemstation software. The program used for the analysis was the following: the oven temperature was set at 35 °C for 2 min, and then the temperature increased at a rate of 10 °C min−1 up to a final temperature of 230 °C and remained constant for 3 min. The temperature of the injector was 260 °C, while helium (He) at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1 was used as a carrier gas.

2.4.2. HPLC

An HPLC (1260 Infinity series, Agilent Technologies) equipped with a PL aquagel‐OH 20 column and coupled with a refractive index (RI) detector was used to measure MeOH concentration in reaction samples. The isocratic method was applied with ultrapure water as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1.

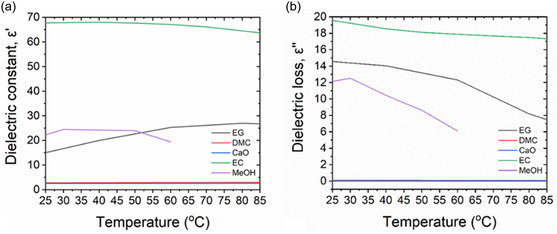

2.4.3. Dielectric Properties Measurements

Dielectric constants and dielectric loss of the reaction compounds were measured using the cavity perturbation method.[ 18 ] A network analyzer (Anritsu MS2026C) connected to a PC and controlled by a self‐written LabVIEW application was utilized. The samples were placed in a quartz tube with an internal diameter of 3 mm and a length of up to 50 mm. Measurements were conducted at a frequency of 2.45 GHz, across a temperature range of 25–85 °C.

2.4.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

A Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC was used to measure the decomposition and the melting point of the produced EC. The atmosphere of the oven and balance chamber was filled with N2 while the flow rate for the sample was 60 mL min−1. Samples of ≈10 mg were weighed in alumina crucibles and heated from 25 to 500 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

2.4.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The obtained product was qualitatively analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy using a Jasco FT/IR 6700 spectrometer applying the KBr method. Spectra were obtained with a resolution of 2 cm−1 and 32 scans per recording in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. Prior to sample analysis, a background spectrum was recorded from the cell chamber to account for ambient environmental factors and baseline variations, ensuring that only the sample's absorbance is presented in the spectra.

2.4.6. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

1H NMR and 13C NMR measurements were recorded on a Bruker Avance DRX 500 MHz operating at 500.13 MHz and 125.77 MHz for 1H and 13C measurements, respectively. Samples were measured using DMSO‐d6 in an NMR tube of 5 mm OD and 7″ length.

2.4.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

FEI Quanta Inspect SEM operating at 25 kV accelerating voltage, equipped with an EDAX Genesis energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectrometer utilized for studying catalyst morphology and elemental analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

As previously mentioned, the transesterification of EG with DMC to produce EC and MeOH is an endothermic reaction, requiring high operating temperatures to achieve high conversions and yields. However, under ambient pressure, the operating temperature is limited by the boiling point of DMC (≈90 °C). Exceeding this temperature leads to excessive DMC evaporation, reducing the availability of the reactant in the liquid phase and hindering further reaction progression. In contrast, the evaporation of MeOH (by‐product, boiling point ≈65 °C) can positively influence the reaction by facilitating its removal from the liquid phase, thereby shifting the reaction equilibrium toward product formation.

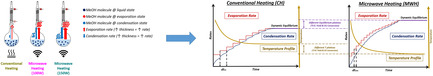

MWH has shown significant potential for intensification of equilibrium‐limited reactions by selectively heating polar byproducts, such as water or MeOH, to promote their removal via phase change.[ 12 , 19 , 20 , 21 ] In most cases, the systems studied involve the presence of a low boiling point polar product in a high boiling point nonpolar reactive mixture rendering MWs an effective energy transfer mode to selectively heat and remove the volatile polar product from the reactive mixture creating a shift in equilibrium composition.[ 12 , 21 ] According to Figure 3 , the studied system presents a polar–polar relationship between its product and reactant sides with the mixture's polarity increasing as the reaction progresses due to the transformation of the only nonpolar reactant (DMC) to the highly polar EC and MeOH. The rise in mixture's polarity translates into enhanced and continuously increased volumetric energy dissipation under MW irradiation. Combination of this effect with the presence of MeOH by‐product that has significantly lower boiling point compared to the other components can intensify MeOH mass transfer from the liquid to the vapor phase under MWH and thereby enhance liquid phase reaction rates. In this context, the study herein compares MWH and CH to the transesterification of EG and DMC to verify the presence and assess the impact of the abovementioned effect.

Figure 3.

a) Dielectric constant, ε′, and b) Dielectric loss factor, ε″, for EG, DMC, CaO, EC, and MeOH[ 30 ] as a function of temperature.

To that end, the reaction was conducted under two distinct operational regimes: 1) isothermal operation at 60 °C where the reaction proceeds entirely in the liquid phase without evaporation of reactants or products, and 2) reflux operation commencing at ≈90 °C, where the evaporation of MeOH is exploited to shift the reaction equilibrium and enhance product formation. The isothermal regime was investigated to determine the maximum attainable conversion and yield in the absence of phase‐change effects, providing a baseline for comparison. In contrast, the reflux regime aimed at determining the difference in the attainable yield and conversion values when MeOH evaporation–condensation phase change is utilized to shift the reaction equilibrium. MWH has been applied in both isothermal and reflux conditions to explore possible occurrence of any MW‐specific effects. The effect of MW power under reflux conditions was further investigated to quantify its impact on reaction metrics, process time, and energy efficiency, while the role of MWH in reducing catalyst dependency was also assessed in the context of process sustainability and operating efficiency.

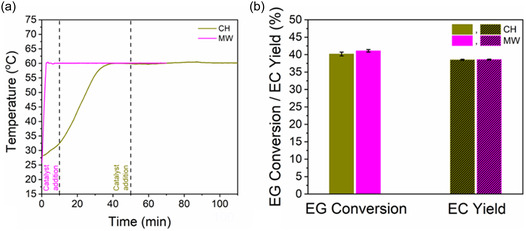

3.1. Isothermal Operation under Nonboiling Conditions: CH versus MWH

Under isothermal, nonboiling conditions, MWH achieved significantly faster temperature ramping, reaching the target reaction temperature of 60 °C 16 times faster than CH (Figure 4a). This rapid heating resulted in 94% reduction in preheating time, greatly improving process efficiency. Figure 4b shows that after 1 h of reaction time both MWH and CH resulted in nearly identical EG conversion and EC yield values. This indicates that no specific reaction rate acceleration was observed under MWH during isothermal operation. Similar findings have been reported in various organic reaction systems, where MWH and CH yield comparable results at the same reaction temperature.[ 19 , 22 , 23 ]

Figure 4.

a) Temporal temperature profile and b) comparison of EG conversion and EC yield between MWH and CH methods under isothermal conditions (reaction conditions: DMC:EG molar ratio = 2.24:1, CaO loading = 0.1% w/wEG and t R = 1 h).

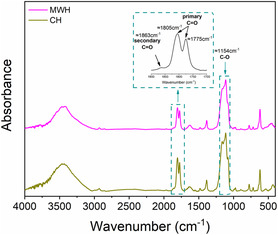

FTIR analyses were conducted to elucidate the chemical structure of the synthesized EC and investigate any structural variations arising from the applied heating source. Figure 5 presents FTIR spectra of EC samples collected at the end of the transesterification reaction using both CH and MWH. For both samples, distinct C=O group stretching peaks are observed at 1775 and 1805 cm−1, where the 1805 cm−1 peak is attributed to the primary C=O group stretching vibration, and the 1775 cm−1 peak is attributed to the overtone of the ring breathing mode. This dual‐band feature is well recognized as characteristic of pure EC.[ 24 , 25 ] Additionally, EC shows a unique skeletal stretching vibration at 1113 cm−1 and a secondary C=O group stretching band at 1863 cm−1, further confirming its structural identity.[ 3 ] Additional spectral features include bands at 1481, 1387, and 1067 cm−1, which are assigned to CH2 scissoring and wagging vibrations, as well as C—O stretching modes.[ 26 ] A characteristic triplet near 2930 cm−1 is attributed to sp 3‐hybridized C—H bonds.[ 27 ]

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of EC produced using MWH and CH.

The FTIR spectra of EC synthesized via MWH and CH showed no differences in peak positions or intensities, confirming that the chemical structure of EC was unaffected by the heating method. This observation, combined with comparable EG conversions and EC yields under isothermal conditions, indicates that the transesterification reaction mechanism and kinetics remain unchanged irrespective of the applied heating source. These results align with the prevailing understanding that the effects of MW‐assisted organic reactions are attributed primarily to purely thermal phenomena. However, as previously mentioned, despite the absence of any MW‐specific reaction effect during the isothermal experiments, MWH offered a significant advantage in the preheating rate, reducing the total process time (preheating + reaction) by 37% compared to CH. This reduction in process time directly improved the overall productivity of EC, demonstrating the potential of MWH to eliminate the heating fluid thermal inertia commonly observed in CH systems.

3.2. Reflux Operation

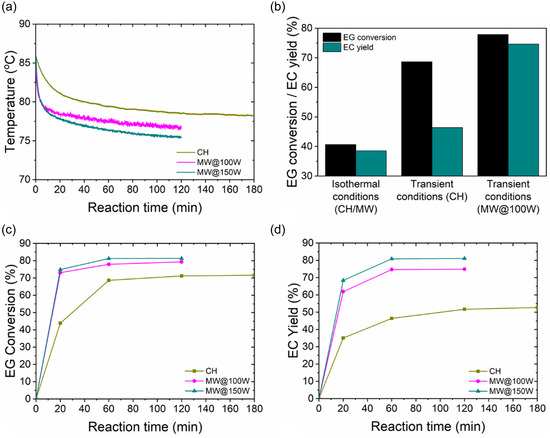

3.2.1. Temperature Dynamics, Reaction Performance, and MeOH Phase‐Change Cycle: Reflux versus Isothermal Conditions under CH and MWH

All experiments in this section were conducted under reflux conditions, starting at an initial temperature of ≈86 °C. Figure 6a,b demonstrates that operation under reflux conditions with MWH leads to faster decrease in the reaction temperature profile and a significant increase in conversion and yield, that is, 69% and 20%, respectively, compared to isothermal CH experiments. The decreasing temperature profile observed under reflux conditions can be attributed to the higher reaction progression due to both elevated operating temperatures—compared to isothermal conditions—and the introduction of MeOH phase change. As the reaction progresses, MeOH, the compound with the lowest boiling point (Table 1 ), is produced, altering the composition of the reactive mixture, lowering its overall boiling point and driving the decreasing temperature profile until the reaction reaches completion.[ 28 ] The removal of MeOH through phase‐change evaporation–condensation cycles shifts the reaction equilibrium toward product formation. Figure 6c,d presents the higher conversions and yields achieved under reflux conditions, highlighting the critical role of MeOH removal in overcoming reaction equilibrium limitations and promoting product formation.

Figure 6.

a) Temporal temperature profiles, b) comparison of EG conversion and EC yield under isothermal and transient conditions, c) temporal EG conversion, and d) EC yield profiles under CH and MWH (at 100 and 150 W) at reflux conditions (reaction conditions: DMC:EG ratio = 2.24:1, CaO loading = 0.1% w/wEG and t R = 1 h).

Table 1.

Boiling points of the compounds involved in the transesterification reaction of EG.

| Compound | Boiling point [@760 mmHg] |

|---|---|

| EG | 198 |

| DMC | 90 |

| EC | 244 |

| MeOH | 65 |

MWH, as shown in Figure 6a–d, amplifies these effects, resulting in steeper temperature declines and higher conversions and yields than the corresponding profiles obtained under CH reflux conditions. This is strongly correlated with the applied MW power, where increased power levels lead to progressively higher conversions and yields. Under CH, the reaction reached a maximum conversion of 71% and yield of 52% after 2 h, whereas MWH resulted in higher EG conversion and EC yield levels while reducing process time by 50% (≈1 h). Specifically, at 100 W, MWH elevated EG conversion and EC yield to ≈79% and ≈75%, respectively, surpassing the corresponding values attained under CH. Further increase in MW power to 150 W led to EG conversion and EC yield of ≈81%, underscoring the power‐dependent nature of MW‐driven intensification. As will be discussed in the next sections, this reaction enhancement is due to the presence of MeOH in both reaction steps (Figure 1). Figure 7 presents gas chromatographs of the residual reaction mixture after 1 h under MWH at applied output powers of 100 and 150 W. Due to the polar nature of the reactive mixture, the higher the applied power, the more MeOH is being transferred from the liquid bulk to the vapor phase. This microwave‐induced MeOH evaporation (MIME) leads both reaction steps to shift to the right. As shown in Figure 7 and Figure S1, Supporting Information, application of higher power (150 W) results in lower concentration of the intermediate HEMC, which subsequently leads to higher EG conversion (Figure 6c). Furthermore, under MWH, the HEMC yield exhibits a decreasing trend from 20 min onward, in contrast to the increasing trend observed under CH up to 60 min. This behavior indicates an accelerated reaction progression under MWH. Additionally, in both heating modes, the byproduct DEG is formed with yields up to ≈2%, as shown in Figure S2, Supporting Information, and its presence does not influence the reaction progression, unlike the intermediate product HEMC. However, by applying the purification protocol described in Section 2.3, pure EC is obtained without detectable traces of EG, HEMC, or DEG. Consequently, a new equilibrium plateau is reached at higher power levels, with EG conversion and EC yield increasing to 75% and 81% at 100 and 150 W, respectively, demonstrating the direct relationship between power input and reaction equilibrium.

Figure 7.

GC chromatograph of the residual reaction mixture.

This improved performance cause lies in the phase‐change behavior of MeOH in the reactive mixture, which is driven by its low boiling point and the high dielectric loss factors of EG, EC, and MeOH. MW irradiation promotes substantial energy dissipation throughout the reactive mixture, thus enabling MeOH vaporization and enhancement of its mass transfer into the vapor phase. More specifically, efficient thermal energy utilization under MW irradiation drives this phase transition, initiating a phase‐change cycle (PCC) that continuously removes MeOH from the liquid phase, shifting the reaction equilibrium toward greater product formation and an elevated equilibrium plateau.

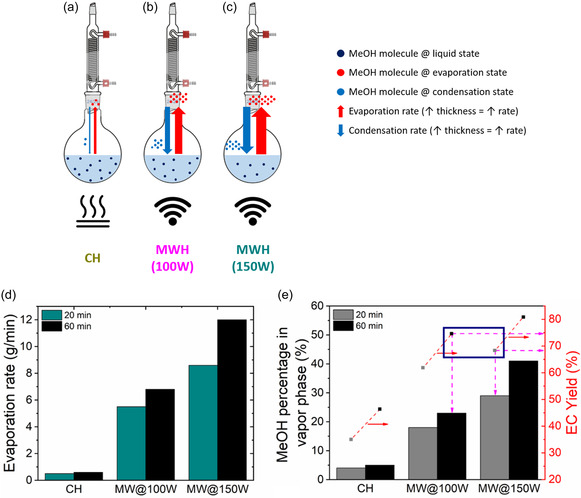

A schematic of the MeOH PCC is shown in Figure 8a–c, while Figure 8d demonstrates the MW‐induced evaporation rates at 100 and 150 W compared to the ones obtained by CH. Evaporation rates were measured by collecting an amount of vapor phase over a specified time interval in a receiving flask after condensation. As expected, increasing MW power increases the MIME effect, raising evaporation rates by 16 and 20 times at 100 and 150 W, respectively, compared to the CH reflux mode. The enhanced evaporation rates under MWH are unable to be matched by the corresponding condensation rates continuously driving the system toward unsteady state operation. Figure 8e supports this mechanism, illustrating how transitioning from CH to MWH alters MeOH's phase distribution, leading to higher MeOH vapor‐phase concentrations. Specifically, the vapor MeOH concentration increases from 4% and 5% under CH to 18% and 23% under MWH at 100 W for reaction times of 20 and 60 min, respectively. Increase in MW power to 150 W further enhances MeOH vapor phase fraction to 29% at 20 min and 41% at 60 min. This behavior verifies the existence of a MW‐induced power‐dependent PCC that enables accelerated, unsteady‐state operation that surpasses equilibrium barriers and drives the system toward higher conversion and yield values. Indeed, a close inspection of Figure 8e reveals the accelerated state of the reaction upon transitioning to MWH. Specifically, at 60 min and 100 W, the reaction has reached its EC yield plateau (≈75%), and ≈23% of the total MeOH is concentrated in the vapor phase. In contrast, at 20 min and 150 W, the reaction has not yet reached its equilibrium EC yield plateau (≈67% vs ECplateau ≈ 81%), although the MeOH vapor phase concentration fraction is ≈26% higher than in the previous case. This contradiction, between the lower yield, thus lower reaction progression, and the higher concentration of MeOH in the vapor phase, essentially represents the driving force generated by the intensified and power dependent PCCs that solely dictate the reaction progression under MWH. The abovementioned results are summarized schematically in Figure 8a–c. MWH leads to higher transfer rate of MeOH into the vapor phase (dark blue circles) and a higher total evaporation rate, as indicated by the increased thickness of the respective arrows.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the MeOH phase‐change cycle in case of a) CH, b) MWH at 100 W, and c) MWH at 150 W. d) Evaporation rates and e) MeOH percentage in vapor phase for CH, MWH at 100 W and MWH at 150 W output power (reaction conditions: DMC:EG ratio = 2.24:1 and CaO loading = 0.1% w/wEG). The square filled points in (e) represent EC yield plateau values.

3.2.2. Microwave‐Induced Methanol Evaporation (MIME): Effect on Catalyst Loading

The influence of MWH on catalyst loading was evaluated under reflux conditions and compared with literature‐reported CH processes, as summarized in Table 2 . The transesterification of EG with DMC typically requires a catalyst to achieve sufficient reaction progression under moderate conditions, as noncatalyzed systems are limited by high temperature and pressure requirements. For instance, a noncatalyzed process (entry 1) achieves 97% EG conversion and 84% EC yield after 5 h under high‐pressure conditions at 150 °C. While such reaction performance is noteworthy, operating at lower pressures and shorter reaction times creates potential for simple and more cost‐effective operation.

Table 2.

Summary of reaction conditions and corresponding EG conversions and EC yields reported in literature for the transesterification of EG with DMC.

| Entry | Type of heating | Catalyst | Catalyst loading [% w/wEG] | Reaction temperature [°C] | Reaction pressure | Reaction time [h] | DMC:EG [mol:mol] | EG conversion [%] | EC yield [%] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncatalysis | ||||||||||

| 1 | CH | – | – | 150 | Autogenous | 5 | 5 | 97 | 84 | [31] |

| Homogeneous catalysis | ||||||||||

| 2 | CH | W(CO)6 | 17 | 180 | Autogenous | 1 | 4 | 100 | 36 | [5] |

| 3 | CH | Co2(CO)8 | 17 | 180 | Autogenous | 1 | 4 | 95 | 95 | |

| 4 | CH | [P8,8,8,1] [OCO2Me] | 4 | 90 | Ambient | 4 | 2 | 88 | 73 | [11] |

| 5 | CH | [P8,8,8,1] [OCO2Me] | 4 | 120 | Autogenous | 4 | 2 | 100 | 88 | |

| 6a) | CH | [P8,8,8,1] [OCO2Me] | 4 | 90 | Ambient | 4 | 2 | 100 | 94 | |

| Heterogeneous catalysis | ||||||||||

| 7 | CH | Mg3Al0.9Ce0.1O | 1 | 150 | Autogenous | 0.7 | 4 | 42 | 41 | [3] |

| 8 | CH | Mg3Al0.9Ce0.1O | 7 | 90 | Ambient | 0.8 | 4 | 52 | 51 | |

| 9 | CH | Mg3Al0.9Ce0.1O | 7 | 150 | Autogenous | 0.8 | 2 | 79 | 78 | |

| 10 | CH | Mg3Al0.9Ce0.1O | 5 | 150 | Autogenous | 0.7 | 4 | 98 | 95 | |

| 11 | CH | KIP321p resin | 4 | 100 | Autogenous | 5 | 1 | 54 | – | [8] |

| 12 | CH | KIP321p resin | 4 | 120 | Autogenous | 5 | 1 | 61 | – | |

| 13 | CH | KIP321p resin | 4 | 100 | Autogenous | 3 | 2 | 74 | – | |

| 14 | CH | KIP321p resin | 4 | 120 | Autogenous | 5 | 1 | 33 | – | [6] |

| 15 | CH | KIP321p resin | 8 | 120 | Autogenous | 5 | 1 | 39 | – | |

| 16 | CH | KIP321p resin | 8 | 120 | Autogenous | 5 | 2 | 55 | – | |

| 17 | CH | CaO | 0.1 | 86b) | Ambient | 2 | 2 | 71 | 52 | Current work |

| 18 | CH | CaO | 2 | 86b) | Ambient | 1 | 1 | 75 | 54 | |

| 19 | MWH (100 W) | CaO | 0.1 | 86b) | Ambient | 1 | 1 | 71 | 58 | |

| 20 | MWH (150 W) | CaO | 0.1 | 86b) | Ambient | 1 | 2 | 81 | 81 | |

Continuous removal of methanol via distillation.

Starting reaction temperature.

Homogeneous catalysts, such as ionic liquids (entries 4–6), have been shown to achieve EC yields of up to 94% at 90 °C with continuous MeOH removal under ambient pressure. However, these systems demand high catalyst loadings (4% w/wEG), and their separation and reuse pose significant operational complexities and costs, limiting their scalability in industrial settings. On the other hand, heterogeneous catalysts, such as Mg3Al0.9Ce0.1O (Entries 7–10), offer advantages in terms of recovery and reuse, aligning with sustainable industrial practices. Their reaction performance, however, relies on high catalyst concentrations (up to 5% w/wEG), high pressures, and elevated temperatures (150 °C), which increase energy and material costs.

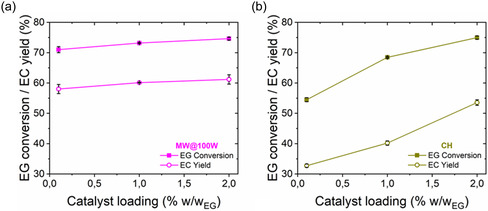

MWH has the potential to reduce catalyst dependency while maintaining high reaction performance. Specifically, 71% EG conversion and 58% EC yield at a catalyst loading of only 0.1% w/wEG (Entry 19) were achieved under ambient pressure and mild temperatures (≈90 °C) when MWH was applied. This performance contrasts with CH, where only 33% EC yield was achieved at the same catalyst loading and reaction conditions. To reach comparable yields of 54%, CH required a 20‐fold increase in catalyst concentration (2.0% w/wEG), which demonstrates a strong dependency on catalyst concentration (entry 18, Figure 9b). Again, the enhanced performance of MWH can be attributed to the MIME effect, which significantly amplifies the intensity of the PCCs creating a continuous driving force toward the product side. This mechanism enables consistent EG conversion and EC yield across a wide range of catalyst loadings, as shown in Figure 9a. In contrast, CH exhibits a strong dependence on catalyst loading, with a 64% yield increase observed between catalyst loadings of 0.1% and 2.0% w/wEG. The ability of MWH to decouple reaction performance from catalyst loading via intensified phase‐change performance highlights its effectiveness in overcoming equilibrium limitations through enhanced product‐related mass transfer phenomena.

Figure 9.

EG conversion and EC yield for a) MWH at 100 W and b) CH, respectively, with varying catalyst loadings from 0.1 to 2% w/wEG (reaction conditions: DMC:EG ratio = 1.12:1 and t R = 1 h).

When compared to literature‐reported CH processes, MWH offers distinct advantages in terms of reaction efficiency and catalyst utilization. For example, Selva et al. (entry 6) achieved a 94% EC yield at 90 °C with continuous MeOH removal using a homogeneous catalyst at 4% w/wEG. In the present study, MWH achieved comparable yields with a 40‐fold reduction in catalyst loading under similar reaction conditions. Similarly, Gao et al. (entry 16) reported 55% EG conversion after 5 h at 120 °C using an 8% w/wEG basic resin catalyst in an autoclave reactor. In contrast, application of MWH resulted in 81% conversion and yield in just 1 h under ambient pressure with only 0.1% w/wEG catalyst (entry 20). The reduced catalyst dependency observed with MWH under reflux conditions implies economic and operational benefits. Lower catalyst consumption reduces raw material costs and simplifies downstream processes, such as catalyst separation and regeneration, which are energy‐ and time‐intensive.

To further validate the effect of MWH on the synthesis of EC under reflux conditions compared to conventional autoclave operation, an additional experiment was conducted. Using a conventionally heated autoclave batch reactor, the reaction was performed at 125 °C with a catalyst loading of 0.1% w/wEG, maintaining identical process conditions (DMC:EG = 2.24 and t R = 1 h) to the MW‐assisted reflux experiments. Under these conditions, CH achieved 74% EG conversion and 58% EC yield, values lower than the 81% conversion and yield obtained with MWH at 90 °C under ambient pressure. Thus, MWH can be considered as a promising and attractive alternative for EC synthesis under milder conditions.

Catalyst Characterization

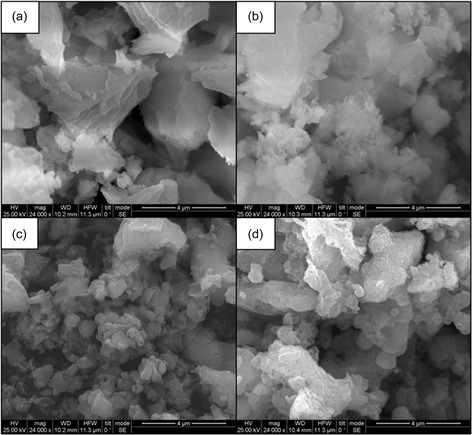

SEM images of fresh CaO (Figure 10a) show indications of calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) formation, likely due to moisture absorption. EDX analysis confirms an O:Ca atomic ratio of ≈1:1, which closely corresponds to that of pure CaO. These findings highlight the susceptibility of CaO to atmospheric moisture, emphasizing the need for precautionary measures to minimize hydration during handling and reaction steps.

Figure 10.

SEM pictures of a) pure CaO, b) postreaction CaO (without posttreatment), c) CaO dried at 110 °C for 14 h, and d) CaO calcinated at 600 °C for 14 h.

Following the catalytic reaction, the O:Ca atomic ratio increased to ≈2.2:1, indicating the formation of Ca(OH)2, likely due to interaction with water or alcohols. This transformation is clearly observed on the respective SEM micrograph (Figure 10b), where sharp stick‐like structures of Ca(OH)2 are evident. The presence of Ca(OH)2 leads to loss of O2− basic sites, which are essential for catalytic activity, thereby contributing to catalyst deactivation.

To enable the reuse of filtered CaO for consecutive reactions, a posttreatment step is required. For catalyst regeneration, two thermal treatments were applied: drying at 110 °C for 14 h and calcination at 600 °C for 14 h. The SEM images of the treated CaO samples are presented in Figure 10c,d, respectively.

As shown in Figure 10c, the dried CaO still exhibits some indications of Ca(OH)2, with an O:Ca atomic ratio of ≈1.1:1, suggesting that drying alone does not fully eliminate hydroxide species. In contrast, Figure 10d depicts a highly porous CaO structure with no detectable traces of Ca(OH)2, indicating that calcination effectively decomposed the hydroxide phase.

These results confirm that calcination at 600 °C is the most effective regeneration method, as it fully restores the porous structure and active sites of CaO, ensuring its reusability for further catalytic cycles.

Catalyst Reusability

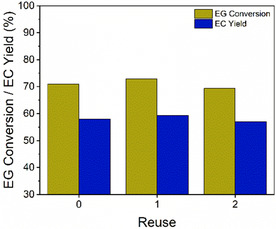

Heterogeneous catalysts are widely used in industrial applications due to their reusability and ease of separation, leading to reduction in the downstream process time and in the overall reaction costs. To evaluate the reusability of CaO under MWH, the catalyst was filtered and calcinated at 600 °C for 14 h before being reused in two consecutive identical experimental runs (MWH, CaO loading = 0.1% w/wEG, DMC:EG ratio = 1.12:1, and reaction time = 1 h), following the same recovery and thermal treatment process after each experiment.

The results, presented in Figure 11 , show that the calcinated CaO achieved similar EG conversions and EC yields across multiple runs, aligning with previous findings on the structural integrity of the catalyst. These findings indicate that CaO can be effectively regenerated and reused through calcination treatment for the transesterification of EG.

Figure 11.

Reusability test of the catalyst up to two consecutive runs (reaction conditions: CaO loading = 0.1% w/wEG, DMC:EG ratio = 1.12:1 and t R = 1 h).

In transesterification reactions, catalyst regeneration often involves energy‐intensive steps, including solvent washing, drying, and recalcination at high temperatures. While these methods are well established for catalyst regeneration, they present certain challenges. Solvent washing can cause leaching of the active sites, with its extent being determined by the washing time, drying conditions, and solvent‐to‐catalyst ratio. Additionally, catalyst loss may occur during washing due to handling difficulties, further reducing the overall efficiency. Furthermore, recalcination is a time‐consuming process that significantly contributes to high energy consumption, impacting the overall sustainability of the reaction process.[ 29 ]

Therefore, a more comprehensive study on the optimization of posttreatment steps and long‐term reusability of CaO is required to determine whether catalyst regeneration is a more viable option compared to purchasing and using fresh CaO for industrial applications. This investigation, while essential, is beyond the scope of the present study.

3.2.3. Process Efficiency: Reaction Time and Energy Consumption Analysis

Efficient production of EC via the transesterification of EG and DMC requires a careful balance between reaction time, energy consumption, and product yield. CH methods often face limitations due to slow heat transfer and high‐energy demands, prompting the need for alternative heating sources such as MWH. To evaluate the comparative process efficiency of CH and MWH, this study examined both preheating requirements and energy consumption during the reaction, highlighting the potential for MWH to intensify reaction performance.

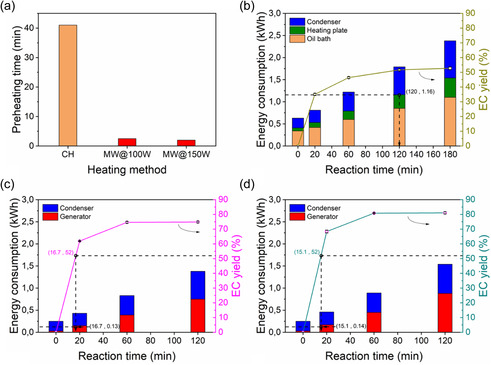

As demonstrated in the isothermal operation experiments, MWH significantly accelerated the preheating stage. Similarly, when operating in transient reflux conditions, MWH also reduced preheating time by a factor of 16 compared to CH (Figure 12a) due to faster temperature ramping. Energy requirements of each heating mode were quantified using power meters. CH includes the energy requirements of the oil bath, heating plate and condenser, while in the case of MWH, the respective requirements are of the SSG and condenser. MWH reduced the preheating energy consumption by 92% (MWH ≈ 0.038 vs CH ≈ 0.4 kWh), considering that the condenser requirements were similar for both systems (≈0.25 kWh), and therefore it is not taken into account in the energy comparison of the two heating modes.

Figure 12.

a) Preheating time for both heating modes and b–d) energy consumption and the corresponding EC yields for CH, MWH at 100 and 150 W, respectively.

Beyond preheating efficiency, MWH also improved reaction productivity. As shown in Figure 12b–d, MWH achieved the highest EC yield attainable by CH (≈52%) in 87% less total reaction time due to the MIME effect. To quantify energy efficiency, the specific energy requirement was calculated as the energy consumed per mole of EC produced (kJ molEC −1). Figure 12c,d illustrates that achieving the maximum EC yield of ≈52% with CH required significantly more energy than MWH. Specifically, MWH consumed ≈0.13 kWh, which translates to ≈9 times lower energy cost compared to CH to obtain the same level of EC yield. This significant reduction is a direct result of the volumetric heating principle of MWs and the MIME effect, which synergistically accelerate productivity while maintaining energy efficiency.

4. Conclusions

This study provides insights for the first time on the transesterification of EG with DMC to produce EC and MeOH under CH and MWH in batch systems operating at ambient pressure. Unlike previous studies that typically employ CH in autoclave conditions with elevated pressures, this work explores MWH‐assisted reflux operation as an alternative heating approach, aiming to achieve conversions and yields comparable to those attained in high‐pressure conventionally heated systems.

Under isothermal conditions, CH and MWH attained similar EG conversion and EC yield. However, MWH significantly reduced preheating time by 94% compared to CH and ultimately shortened the total process time by 37%. This advantage arises from the MW rapid volumetric heating principle, which overcomes the heat transfer limitations set by the thermal inertia of the heating fluid in conventional heated systems. Under reflux conditions, MWH enhanced reaction performance by intensifying continuous phase‐change cycles for by‐product (MeOH) removal that, in turn, generated a continuous shift of the equilibrium composition values toward ones corresponding to higher conversions. The increasing mixture's polarity, leading to high energy dissipation throughout the mixture, coupled with the MeOH low boiling point facilitated its vaporization increasing its concentration in the vapor phase from 5% with CH to 23% and 41% with MWH at 100 and 150 W, respectively. This rapid and targeted phase‐change behavior effectively overcame chemical equilibrium limitations and drove the reaction toward product formation, establishing a new equilibrium state with a 79% EG conversion and 75% EC yield in half the time required by CH to reach its maximum EG conversion and EC yield of 71% and 52%, respectively. Further increasing MW power to 150 W had minimal effect on EG conversion but notably enhanced EC yield, raising it to ≈81%, underscoring the power‐dependent nature of MW‐driven intensification.

Additionally, MWH significantly reduced catalyst dependency, enabling high conversions and yields. At a catalyst loading of 0.1% w/wEG, MWH achieved a 59% EC yield, whereas CH led to an EC yield of only 33% under identical reaction conditions. To reach a comparable ≈60% EC yield with CH, a 20‐fold increase in catalyst loading was required, highlighting the process intensification potential of MWH and its associated economic benefits related to the catalyst loading.

Besides, an energy analysis and comparison of the MW‐assisted reflux operation and CH‐assisted reflux operation showed that MWH substantially decreased energy consumption, achieving up to 92% reduction in preheating energy requirements and a 9‐fold decrease in specific energy usage per mole of EC produced compared to CH. This improvement in energy efficiency, combined with enhanced reactants conversion and product yield, renders MWH as a promising alternative energy source for intensified EC production at ambient pressure conditions.

It is finally remarked that the findings presented in this work are directly relevant to a broad class of equilibrium liquid phase reactions entailing low‐boiling point products present in polar reactive systems with reactants of higher boiling point. Batch processes involving such chemistries can be intensified by application of MWH through the introduction of power‐dependent PCCs. The concept leverages the mixture polarity to enable rapid volumetric energy transfer that enhances the evaporation rate of the most volatile product compound(s) and drives the reaction toward equilibrium states corresponding to higher reactant conversion levels that are unattainable by CH.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research has received funding from the European Union's Horizon research and innovation programs under grant agreement no. 101058279 (SIMPLI‐DEMO). This publication reflects only the authors’ view, exempting the Community from any liability. Project website: https://simpli‐demo.eu/. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Matthias Graf and Christian Ress from ICT Fraunhofer (Pfinztal, Germany) for the dielectric properties measurements. The authors are also thankful to Dr. Nikos Boukos from Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology of National Centre of Scientific Research “Demokritos” (Greece) for carrying out SEM‐EDX analyses and the discussions regarding their results.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Pyo S., Hatti‐Kaul R., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 834. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang T., Li W., Ge X., Qiu T., Wang X., Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 243. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guo F., Wang L., Cao Y., He P., Li H., Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2023, 662, 119273. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ng W. L., Minh Loy A. C., McManus D., Gupta A. K., Sarmah A. K., Bhattacharya S., ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 14287. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khusnutdinov R. I., Shchadneva N. A., Mayakova Y. Y., Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 50, 948. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao X., Wang Y., Wang R., Dai C., Chen B., Zhu J., Li X., Li H., Lei Z., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 2249. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Song Y.‐C., Ding X.‐S., Wu C.‐C., Wang Y.‐J., RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han C., Wang R., Shu C., Li X., Li H., Gao X., React. Chem. Eng. 2022, 7, 2636. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kather A., Mehrkens C., in Industrial High Pressure Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Hoboken, NJ: 2012, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Z., Gérardy R., Gauron G., Damblon C., Monbaliu J.‐C. M., React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 17 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Selva M., Caretto A., Noè M., Perosa A., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Altman E., Stefanidis G. D., van Gerven T., Stankiewicz A. I., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 10287. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao X., Li X., Zhang J., Sun J., Li H., Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 90, 213. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Filho E. G. R. T., Dall’Oglio E. L., de Sousa P. T., Ribeiro F., Marques M. Z., de Vasconcelos L. G., de Amorim M. P. N., Kuhnen C. A., Brazilian J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 691. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ochoa‐Gómez J. R., Gómez‐Jiménez‐Aberasturi O., Maestro‐Madurga B., Pesquera‐Rodríguez A., Ramírez‐López C., Lorenzo‐Ibarreta L., Torrecilla‐Soria J., Villarán‐Velasco M. C., Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2009, 366, 315. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Truitt M. J., US Patent 8,617.262 B2 2013.

- 17. Tojo M., Oonishi K., US Patent 6,346,638 B1 2002.

- 18. Rzepecka M. A., J. Microw. Power 1973, 8, 3. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kappe C. O., Pieber B., Dallinger D., Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De bruyn M., Budarin V. L., Sturm G. S. J., Stefanidis G. D., Radoiu M., Stankiewicz A., Macquarrie D. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H., Meng Y., Shu D., Zhao Z., Yang Y., Zhang J., Li X., Fan X., Gao X., React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 688. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strauss C. R., Rooney D. W., Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1340. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tzortzi I., Xiouras C., Tserpes C., Tzani A., Detsi A., Van Gerven T., Stefanidis G. D., Chem. Eng. Process. ‐ Process Intensif. 2023, 186, 109315. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikezawa Y., Nishi H., Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 3663. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Z., Huang X., Chen L., J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, A199. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lanz P., Novák P., J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, A1555. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Somerville L., Bareño J., P. Jennings , McGordon A., Lyness C., Bloom I., Electrochim. Acta 2016, 206, 70. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ochoa‐Gómez J. R., Gómez‐Jiménez‐Aberasturi O., Ramírez‐López C., Maestro‐Madurga B., Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3368. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shikhaliyev K., Okoye P. U., Hameed B. H., Energy Convers. Manage. 2018, 165, 794. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gabriel C., Gabriel S., Grant E. H., Grant E. H., Halstead B. S. J., Mingos D. M. P., Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 213. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guidi S., Calmanti R., Noè M., Perosa A., Selva M., ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 6144. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.