Abstract

The persistence of nosocomial pathogens in healthcare settings represents a challenge for cleaning and disinfection. Few studies have addressed the efficacy of chemical disinfectants against emergent and multidrug (MDR) resistant ESKAPE bacteria. The aim of this study was to quantify the in-use and off-label efficacy of three commercially available disinfectants: hydrogen-peroxide-, alcohol- and chlorine-based formulations — against twelve genomically characterized ESKAPE pathogens(ST101/258 Klebsiella pneumoniae, ST2 Acinetobacter baumannii, ST131/62 Escherichia coli, ST357 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ST1 MRSA and ST612/203 vanA-positive Enterococcus faecium) plus four reference strains, and to determine how sub-lethal exposures influence key virulence traits. Disinfectant activity (log₁₀-reduction, LR) was measured by a quantitative suspension test (EN14885) with and without 3% bovine serum albumin. Additional assays simulated real-life use (contaminated nitrile/latex gloves), early biofilm formation (crystal-violet microplate assay) and evaluated the secretion of proteases, phospholipases, lipases and haemolysins. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA or unpaired t-tests (P ≤ 0.05). All disinfectants achieved ≥ 5 LR at the manufacturer-specified concentration and contact time; however, efficacy dropped markedly when contact time was halved or concentration reduced. The hydrogen-peroxide-based disinfectant demonstrated minor differences in efficacy. Specifically, the clinical E. faecium 16 VRE strain exhibited higher MBCs compared to the reference strain (3-fold increase) (P < 0.05). A similar behavior was noticed for both clinical Pseudomonas strains that had 4-fold higher MBCs, compared to the P. aeruginosa reference strain (P < 0.05) at a 5-minute contact time. Organic soiling significantly impaired hydrogen peroxide- and chlorine-based disinfectants' activity. On artificially contaminated gloves, the label-strength alcohol-based disinfectant eradicated all strains after 60 s, whereas 30 s exposure or ≥ 25% dilution permitted recovery of up to 10⁵ CFU cm⁻². Sub-inhibitory chlorine or peroxide concentrations reduced early biofilm biomass by 40–70% (P < 0.05) and suppressed extracellular protease/phospholipase activity, while equivalent alcohol exposure had no effect. Manufacturer-recommended concentration and contact time are critical for reliable killing of MDR ESKAPE pathogens. Shortened contact or dilution—common in clinical practice—creates a survival window and may differentially select tolerant species. Chlorine and peroxide formulations additionally attenuate biofilm initiation and soluble virulence factors, suggesting a dual antimicrobial/anti-pathogenic benefit. These findings support strict compliance with label instructions and encourage formulation optimization that couples rapid killing with anti-virulence activity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04273-0.

Keywords: ESKAPE pathogens, Chemical disinfectants, Healthcare

Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and antibiotic resistance are major public health challenges. Despite worldwide efforts to develop and implement infection prevention and control (IPC) practices, the prevalence of HAIs has not significantly decreased. Each day, 8% or > 93000 patients in acute care hospitals in European countries experience HAIs [1]. The problem of HAIs is further complicated by the global dissemination of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Point Prevalence Survey (ECDC PPS) confirmed the ongoing epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Europe, with an overall increase in Klebsiella spp. resistance from 8.7 to 11.7%. However, some countries reported percentages much higher than the European average (e.g., 42.9% in Romania) [1].

Several studies show that opportunistic multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogens are able to persist for long periods of time, as well as to spread in hospital environments and among patients [2–8]. Among them, hospital-acquired Staphylococcus aureus strains were demonstrated to be enriched in virulence and disinfectant resistance genes that could facilitate both colonization and spread [9]. Acinetobacter baumannii survival is related to the viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state persistence strategy adopted to cope with hostile hospital and human host environments [10]. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VREs) harbouring the vanA gene have a greater ability to persist and disseminate in the hospital environment [11]. All these pathogens can form biofilms on different surfaces, conferring additional protection against environmental stress factors, including disinfectants [12]. Therefore, inappropriate use of disinfectants together with the presence of organic waste that can inactive disinfectants or the development of biofilms in which active concentrations of disinfectants are difficult to achieve [13], are two of the main factors leading to prolonged exposure to sublethal concentrations that may select for disinfectant-tolerant microorganisms [14, 15], potentially with cross-resistance to antibiotics [16]. Microbial virulence features may also be impacted by disinfectant sublethal concentrations. Triclosan or chlorhexidine has been shown to decrease the expression of virulence potential in S. aureus [17], Salmonella typhimurium [18], Streptococcus agalactiae and S. mutans [19, 20]. Similarly, peroxides and chlorine compounds decreased, whereas quaternary ammonium compounds induced the virulence genes expression in Listeria monocytogenes [21].

In the medical field, chemical disinfectant products are evaluated by standard protocols using susceptible reference strains (bacteria, viruses, yeasts, fungi, and spores) belonging to the main pathogenic species [22]. However, the use of bacterial isolates from environmental samples, including those from hospital surfaces, food processing locations, wastewater, mines, farms, and lakes, to test disinfectant efficiency could offer more “real-world” evidence regarding the biocide tolerance of bacteria [23]. Pidot et al. [24] reported that contemporary strains of Enterococcus faecium isolated from human infections after 2010 were approximately ten times more tolerant to killing by isopropanol (the active substance found in many alcohol-based hand disinfectants) than strains isolated between 1997 and 2010 [24]. These alcohol-tolerant strains accumulated mutations in metabolic genes, particularly in the mannose phosphotransferase system.

Given worldwide concern over increasing antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogens and the possible decrease in susceptibility to disinfectants, more studies on disinfectant efficacy against MDR pathogens are needed. The aim of this study was to evaluate the bactericidal activity of three chemical disinfectants from different groups against a collection of well-characterized ESKAPE pathogens. Additionally, we investigated how sublethal concentrations of disinfectants used routinely in the medical field influence the phenotypic expression of virulence in HA pathogens.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain collection

A total of twelve ESKAPE clinical strains were selected from a previously characterized Romanian strain collection built during the RADAR project - Selection and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes from wastewater treatment plants into the aquatic environment and clinical reservoirs, PN-III-P4-ID-PCCF-2016-0114. The bacterial strains were selected based on their clinical relevance (i.e., isolated from patients with severe, lung, urinary tract and blood infections admitted to two hospitals in Romania from 2019 to 2020 and belonging to high-risk sequence types-STs) and phenotypic resistance (multidrug-resistance) profiles (Table 1). All strains were identified via routine diagnostics with MALDI TOF MS (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany) and characterized by whole-genome sequencing. The standard test organisms used in disinfectant testing were S. aureus ATCC 6538, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442, E. hirae ATCC 10541 and Escherichia coli K12 NCTC 10538. Fresh bacterial cultures were prepared for each susceptibility test from stock cultures on tryptone soy agar (TSA) (Sharlau, Germany).

Table 1.

List of the ESKAPE strains used in this study

| Bacterial species | Laboratory code | Source | STs |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Ec 2 | Urine | 62 |

| E. coli | Ec 17 | Urine | 131 |

| E. coli | Ec K12 NCTC 10538 | Reference strain | - |

| K. pneumoniae | Kpn 13 | Endotracheal tube | 101 |

| K. pneumoniae | Kpn 159 | Central venous catheter | 258 |

| A. baumannii | Abc 110 | Tracheobronchial aspirate | 2 |

| A. baumannii | Abc 111 | Sputum | 2 |

| S. aureus | Sa 10 | Unknown | 1 |

| S. aureus | Sa 13,358 | Blood | 1 |

| S. aureus | Sa ATCC 6538 | Reference strain | - |

| P. aeruginosa | Ps 1707 | Tracheal secretion | 357 |

| P. aeruginosa | Ps 1696 | Tracheal secretion | Unknown |

| P. aeruginosa | Ps ATCC 15442 | Reference strain | - |

| E. faecium | Ef VRE 15 | Tracheal secretion | 612 |

| E. faecium | Ef VRE 16 | Tracheal secretion | 203 |

| Enterococcus hirae | Ef ATCC 10541 | Reference strain | - |

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) [25] guidelines. Bacterial suspensions prepared from 18–24-hour cultures and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland in sterile saline were inoculated onto Mueller‒Hinton agar (MHA; bioMérieux). The antibiotic-impregnated disks (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific) of ampicillin (10 µg), penicillin (10 U), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 µg), ampicillin-sulbactam (10/10 µg), amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), cefazolin (30 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), cefuroxime (30 µg), ceftaroline (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg), meropenem (10 µg), doripenem (10 µg), imipenem (10 µg), ertapenem (10 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), vancomycin (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), gentamycin (10 µg), tobramycin (10 µg), amikacin (30 µg), minocycline (30 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), daptomycin (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), linezolid (30 µg), cotrimoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), and rifampin (5 µg) were subsequently applied. The standard bacteria E. coli (ATCC 25922), P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, S. aureus ATCC 25923 and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 were used as the control strains for antibiotic susceptibility testing using the disk-diffusion method. Bacterial growth was examined after 18 ± 2 h of incubation at 35 ± 2 °C, under aerobic conditions. The diameters of the inhibition zones (in mm) were measured and interpreted with reference to the CLSI criteria [25].

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

DNA was isolated via a DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Library preparation was performed via the Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep Kit, followed by sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform (V3, 600 cycles). The raw reads were assembled via the Shovill v1.1.0 pipeline, and antibiotic resistance genes were annotated via the ABRicate tool. Molecular typing was performed via the MLST tool.

Evaluation of the ESKAPE strains susceptibility to chemical disinfectants

Chemical disinfectant products

Three commercial chemical disinfectants dedicated to medical areas with different mechanisms of action were tested against twelve clinical ESKAPE strains and four reference strains. The commercial products and their active ingredients are listed in Table 2. The disinfectant label contact time was 1 min for product A and 5 min for product B and product C. Disinfectant dilutions were prepared in water immediately before testing.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the chemical disinfectant products tested

| Disinfectant Products | Active ingredients | Concentration | Contact Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product A | 6.0% hydrogen peroxide | RTU | 5 min |

| Product B | 25% ethanol, 35% propan-1-ol | RTU | 1 min |

| Product C | sodium dichloroisocyanurate, 90% | RTU | 2–15 min |

RTU Ready-To-Use

Quantitative suspension tests

Quantitative suspension tests were conducted using a modified protocol based on the European Standard [22], adapted to a 96-well microplate format. Each clinical strain was cultivated in tryptone soy broth (TSB; Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) until reaching an optical density (OD) of 0.90 at 660 nm. Cultures were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), and bacterial suspensions were adjusted to an OD of 0.08 at 660 nm, corresponding to approximately 10⁸ CFU/mL. An aliquot of 20 µL of the bacterial suspension either without soiling or with a 3-part soiling load (3% Fraction V bovine serum albumin [BSA]; Carl Roth GmbH) was added to 180 µL of disinfectant solution and incubated at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C). The disinfectant solutions were prepared by two-fold serial dilutions in sterile distilled water immediately prior to testing. Bactericidal efficacy was assessed at two contact times: 30 s and 1 min for product A; 1 min and 5 min for products B and C, respectively. Following the treatment, 20 µL aliquots of each test mixture were transferred to 180 µL of neutralizer. The neutralizing solution consisted of TSB containing polysorbate 80 (30 g/L), lecithin (3 g/L), L-histidine (1 g/L), and sodium thiosulfate (5 g/L). Neutralization was performed at 20 ± 2 °C for 5 min, after which the mixtures were serially diluted in PBS. From each dilution, 30 µL was plated onto tryptone soy agar (TSA; Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) and incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 24 ± 2 h. The bacterial counts were assessed after incubation for 48 h, at 35 ± 2 °C. The log reductions (LRs) were calculated based on the European standard guidelines. The efficacy tests were performed in triplicate and repeated on three separate days using independently prepared bacterial cultures. In addition, the possible neutralizer’s toxicity was tested towards the test organism [26]. Briefly, bacterial suspensions were mixed with neutralizer, and after 5 min of incubation, the mixtures were spread onto TSA and incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 24 ± 2 h. Colony counts grown on each plate ranged from 100 to 300 CFU/100 µL, confirming it was not toxic to the tested bacteria.

Disinfectant efficacy testing against contaminated gloves

Nitrile and latex glove pieces (1.0 × 1.0 cm in size) were cleaned and sterilized via a UV germicidal lamp. The sterility of the glove pieces was checked after the UV treatment by incubating them in sterile growth media at 37 °C for 24–48 h. No microbial growth was observed, indicating that the glove pieces were sterile. Further the sterile hydrophobic surfaces were inoculated with 10 µL of bacterial suspension (1.5 × 109 CFU/mL) with an organic load (albumin 3%). Two glove pieces per concentration of disinfectant were used per test. Each surface was dried for 60 min were left to air-dry inside a laminar flow hood that had been turned off (Fig. 1). The contaminated glove surfaces were covered with 100 µL of the alcohol-based disinfectant. Three disinfectant concentrations: 50%, 75%, and 100%, with a constant contact time of one minute were evaluated. Additionally, to determine the effect of varying contact times on the bactericidal efficacy of the disinfectant, two contact times (30 s and 1 min), at label concentration, were assessed. After disinfectant treatment, the glove pieces were transferred to 1000 µL of neutralizer buffer and incubated for 5 min. The microorganisms were detached via a horizontal shaking device. The resulting suspensions were serially diluted and plated on TSA plates for CFU determination. The LR values of each experimental treatment was compared to the corresponding control bacterial count (control glove surfaces were exposed to PBS instead of the disinfectant).

Fig. 1.

Nitrile (upper row) and latex (lower row) glove pieces (1.0 × 1.0 cm in size) after inoculation (left panel) with microbial suspension (1.5 × 109 CFU/mL) with organic load (albumin 3%). Each surface was dried for 30–60 min under a laminar flow hood without an air stream (right panel)

Quantitative assessment of biofilm formation

Biofilm formation was measured in terms of biomass via a crystal violet staining assay. Standardized bacterial suspensions (1.0–1.5 × 108 CFU/mL) were added to TSB (1/10; vol/vol) in a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated at 37 °C ± 2 °C for 24 h. Sterile medium was used as a negative control. After incubation, the plates were emptied and gently washed with sterile PBS. The microbial biomass was fixed with ethanol for 5 min and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. The plates were emptied and washed with sterile distilled water. The crystal violet dye was released with 125 µL of 30% acetic acid for 15 min. The coloured suspensions were transferred to a new 96-well microtiter plate, and the absorbance was measured at 492 nm via a spectrophotometer (Multiskan FC, Thermo Scientific). For interpretation of the results, the strains were classified into the following categories: OD ≤ ODc = no biofilm producer, ODc = OD of the negative control; ODc < OD ≤ 2x ODc = weak biofilm producer; 2 x ODc < OD ≤ 4x ODc = moderate biofilm producer; and 4 x ODc < OD = strong biofilm producer [27].

The influence of sublethal concentrations of disinfectants on biofilm development

Bacterial strains exposed to disinfectant subinhibitory concentrations were evaluated with regards to their ability to develop biofilms. Briefly, 96-well polystyrene flat bottom microtiter plates (TPP Techno Plastic Products AG, Switzerland) were used for disinfectant dilutions, which were then inoculated with bacterial test suspensions prepared from overnight bacterial cultures. After exposure for 1 min (alcohol-based) or 5 min (hydrogen-peroxide- and chlorine-based), aliquots of 20 µL were transferred to 180 µL of neutralizing buffer and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the assay followed the steps described for biofilm formation in section "Quantitative assessment of biofilm formation". The positive control consisted of untreated bacteria, and the negative control consisted of disinfectant dilutions without bacterial culture. The strains were classified on the basis of biomass production as weak, moderate or strong biofilm producers.

Semi-quantitative evaluation of secreted enzymatic virulence factors production in ESKAPE pathogens exposed to sublethal concentrations of disinfectants

The enzymatic activities of the ESKAPE strains exposed to disinfectant subinhibitory concentrations were evaluated by spotting a 10 µL volume of bacterial exposed to disinfectant exposure, onto seven different agar plates assays supplemented with various substrata, i.e.: 1% Tween 80 (lipase); egg yolk (10%, vol/vol (lecithinase); 15% skim milk (protease); 5% sheep erythrocytes (hemolysin). All the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C ± 2 °C. The appearance of a precipitate and/or clear zone around the spot indicated the protease (caseinase) and lecithinase activity, a turbid halo was associated with lipase presence, while hemolysins induced the occurrence of clear zones around the culture spot.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments described in sections "Disinfectant efficacy testing against contaminated gloves","Quantitative assessment of biofilm formation"– "The influence of sublethal concentrations of disinfectants on biofilm development", "Semi-quantitative evaluation of secreted enzymatic virulence factors production in ESKAPE pathogens exposed to sublethal concentrations of disinfectants", were performed in triplicate and repeated on three separate days using independently prepared bacterial cultures. The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10. One factor ANOVAs tests were performed to evaluate the impact of disinfectant concentration, contact time, organic soiling on disinfectant efficacy. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare the impact of disinfectants on various bacterial strains. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Antimicrobial resistance profiles

Eleven out of the twelve selected ESKAPE strains were classified as MDR, displaying resistance to antibiotics belonging to at least three different classes (Fig. 2). The selected K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa strains were phenotypically resistant to 3rd- and 4th-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, monobactams, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin. The S. aureus strains exhibited the MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) phenotype and were resistant to tetracyclines, erythromycin and azithromycin. The E. faecium strains were resistant to vancomycin, penicillin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin and linezolid.

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of the selected ESKAPE pathogens: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and E. faecium. Each black dot represents the presence of antibiotic resistance genes retrieved by WGS analysis, while blue triangles represent the phenotypic resistance; all antibiotics tested are indicated. Aminoglyc., aminoglycoside; DAP, diaminopyrimidine; Phen., Ph., phenicols; Sul., sulphonamide; Tetra./Tet, tetracycline; AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; AK, amikacin; AZM, azithromycin; ATM, aztreonam; CTX, cefotaxime; CPT, ceftaroline; CAZ, ceftazidime; CEF, cefepime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CXM, cefuroxime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; DA, clindamycin; GEN, gentamicin; FOX, cefoxitin; CZ, cefazolin; DOR, doripenem; E, erythromycin; I, imipenem; LZD, linezolid; MERO, meropenem; RD, rifampicin; RND, multidrug efflux pumps; TET, tetracycline; TZP, piperacillin‒tazobactam; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; V, vancomycin

All selected ESKAPE pathogens were investigated for genetic determinants of phenotypic resistance via WGS. The S. aureus genomes harboured the mecA gene. Several variants of the blaSHV, blaTEM, blaVEB and blaOXA genes were detected in the genomes of the Gram-negative pathogens. Two Enterobacterales isolates harboured extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes, such as blaCTX-M-15, conferring resistance to 3rd- and 4th-generation cephalosporins. The carbapenemase genes blaPOM-1, blaOXA-846, blaOXA-10, blaOXA-23, and bla-KPC-2 were detected in four Gram-negative strains. The KPC-2 gene in K. pneumoniae 159 was associated with the fosA gene and with the qacEdelta1 antiseptic resistance gene. The clinically relevant aminoglycoside resistance genes included aadA1 and aadA2, ant(2’’)-Ia, aac(3’)IIa, aac(6’), aph(3’’)-Ib, aph(6)-Id and armA. The van genes were the most common in the E. faecium strains. Tetracycline resistance genes were detected in all the species. Genes encoding RND efflux pumps were detected in K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa strains. Half of the ESKAPE pathogens carried disinfectant genes.

Disinfectant efficacy against MDR strains

The disinfectant’s bactericidal concentrations were recorded if an LR ≥ 5 in viable counts was determined. The results are given in Table 3 and Supplemental file (Figures S1-S18). All the tested disinfectants were efficient against all the tested bacteria at the parameters recommended by the manufacturer (i.e., contact time and concentration).

Table 3.

Disinfectant bactericidal concentrations (%) obtained via quantitative suspension testing. The bactericidal concentrations were recorded if an LR ≥ 5 in viable counts was achieved

| Product A (%) | Product B (%) | Product C (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 s | 1 min | 1 min | 5 min | 1 min | 5 min | |||||||

| Bacterial strains | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | w |

| E. coli NCTC 10538 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 40 | 0.312 | 2.5 | 0.156 | 0.625 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.002 | 4 |

| E. coli 2 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 5 | 0.156 | 2.5 | 0.007 | 4 | 0.002 | 4 |

| E. coli 17 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 5 | 0.156 | 2.5 | 0.007 | 4 | 0.002 | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae 159 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.625 | 5 | 0.625 | 1.25 | 0.004 | 4 | 0.002 | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae 13 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.625 | 10 | 0.625 | 2.5 | 0.004 | 4 | 0.002 | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 15441 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 0.625 | 5 | 0.078 | 5 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa 1696 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 0.625 | 5 | 0.625 | 2.5 | 0.004 | 4 | 0.004 | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa 1707 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 40 | 0.625 | 10 | 0.625 | 10 | 0.004 | 4 | 0.004 | 4 |

| A. baumannii 111 | 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 5 | 0.312 | 5 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 4 |

| A. baumannii 110 | 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.312 | 0.625 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 4 |

| E. hirae ATCC 10541 | 80 | > 80 | 40 | 80 | 0.078 | 2.5 | 0.078 | 0.625 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 8 |

| E. faecium 15 VRE | 80 | > 80 | 40 | 80 | 0.039 | 0.62 | 0.039 | 0.312 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 8 |

| E. faecium 16 VRE | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 2.5 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 8 |

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.078 | 1.25 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 4 |

| S. aureus 10 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.156 | 1.25 | 0.015 | 8 | 0.015 | 4 |

| S. aureus 13358 | > 80 | > 80 | 80 | 80 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.156 | 0.625 | 0.004 | 8 | 0.004 | 4 |

w, with organic soiling (i.e., 3% BSA); w/o, without organic soiling

Overall, the bactericidal concentrations determined for the product A and product C disinfectant products differed only marginally among strains and species. In contrast, product B demonstrated minor differences in efficacy. Specifically, the clinical E. faecium 16 VRE strain exhibited higher MBCs compared to the reference strain (3-fold increase) (P < 0.05). Additionally, both clinical Pseudomonas strains had greater MBCs, compared to the P. aeruginosa reference strain (4-fold increase) (P < 0.05) at a 5-minute contact time.

Organic soiling had no significant influence on the efficacy of disinfectant A (P > 0.05). In contrast, organic soiling significantly affected the efficacy of product B (P = 0.0001 for 1 min contact time and P = 0.0036, for 5 min contact time) and product C (P < 0.0001). A decrease in the bactericidal values was observed when the contact time was increased from 1 to 5 min. The contact time significantly influenced the efficacy of product B (P = 0.0179 (without soiling), P = 0.0059 (with soiling) and product C (P = 0.0373 (without soiling), P = 0.0038 (with soiling).

Assessment of disinfectant efficacy on artificially contaminated gloves

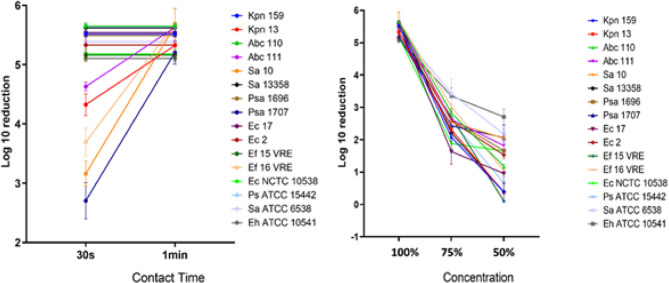

The nitril and latex glove surfaces were contaminated with individual cultures of the pathogens and reference strains. The dried glove surfaces were treated with Product A for different contact times and concentrations. The density of the untreated control was > 2.5 × 106 CFU/mL. For glove surfaces contaminated with different bacterial strains and treated with Product A at label concentrations, bacterial growth was completely eradicated (Fig. 3). In exchange, concentrations and contact times lower than the defined label-use resulted in increased recovery of bacteria (Fig. 3). When the contact time was reduced to 30 s, product A lost its efficiency against A. baumannii Abc111, K. pneumoniae Kpn13, E. faecium Ef16, S. aureus Sa10 and P. aeruginosa Psa1707.

Fig. 3.

The effect of different contact times on the bactericidal efficacy of Product A under in-use conditions (left panel). The effect of various concentrations on the bactericidal efficacy of Product A (right panel). Ec, E. coli; Ps, P. aeruginosa; Sa, S. aureus; Eh, E. hirae; Ef, E. faecium

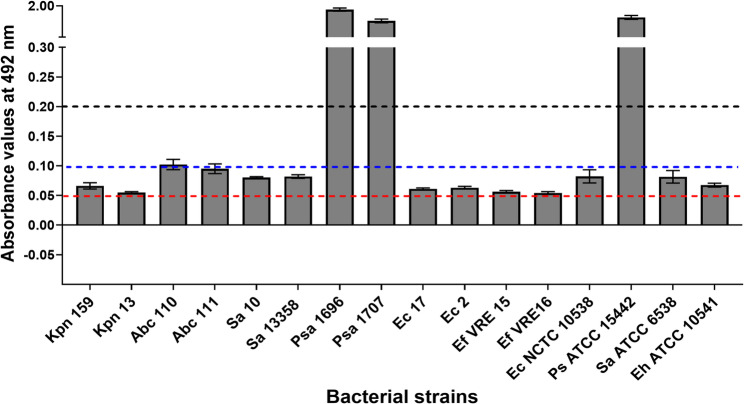

Effects of subinhibitory disinfectant concentrations on biofilm formation

The results of the quantification of biofilm formation in microtiter plates revealed that three bacterial strains were strong biofilm producers (P. aeruginosa 1696, P. aeruginosa 1707, P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442), one strain expressed a moderate phenotype (A. baumannii 110), and twelve bacterial strains (A. baumannii 111, S. aureus 10, E. coli 2, E. coli 17, E. coli NCTC 10538, K. pneumoniae 159 K. pneumoniae 13, S. aureus 10, S. aureus 13358, S. aureus ATCC 6538, E. faecium 15, E. faecium 16, E. hirae ATCC 10541) were expressing weak biofilm-positive phenotype (Fig. 4). Subinhibitory concentrations of Product A and Product C significantly decreased in vitro biofilm production in all the tested strains compared with the defined label concentrations (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). Product B did not significantly alter biofilm formation compared to the untreated control.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of biofilm formation in microtiter plates. Biofilm formation was evaluated in three independent experiments. The bars display the A492 value’s mean value together with an error bar that represents the standard deviation. The A492 values 0.05–0.1 corresponded to weak biofilm formation (red dotted line), the A492 values 0.1–0.2 corresponded to moderate biofilm production (blue dotted line), and values > 0.2 (dark dotted line) corresponded to strong biofilm formation. Ec, E. coli; Ps, P. aeruginosa; Sa, S. aureus; Eh, E. hirae; Ef, E. faecium

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of the effects of subinhibitory disinfectant concentrations on biofilm formation in microtiter plates

The impact of subinhibitory disinfectant concentrations on soluble enzyme expression

Subinhibitory disinfectant concentrations had various effects on soluble bacterial enzyme production. Product B and product C significantly inhibited the production of microbial proteases (P < 0.01) and phospholipases (P < 0.05). The alcohol-based product A did not alter the phenotypic expression of proteases, lipases, phospholipases or hemolysins (Fig. 6, Figure S19).

Fig. 6.

Phenotypic assessment of protease, lipase, lecithinase and haemolysis in different ESKAPE strains. The enzyme activity level was examined in three independent experiments. The bars show the mean values of the zones of enzymatic activity (mm), supplemented by the standard deviation, which is represented as an error bar. The color of the bars represents the bacteria treated with subinhibitory concentrations of disinfectants (no treatment: white; Product A: black; Product B: dark gray; Product C: light gray)

Discussion

Although genetically diverse, ESKAPE pathogens share common mechanisms that drive their emergence and persistence. Their widespread ability to form biofilms on both abiotic and biological surfaces further contributes to their high prevalence in clinical environments. Given their resilience and adaptability, the use of biocidal products for disinfection remains a critical component of infection prevention and control in healthcare settings. However, the growing reliance on these agents has raised concerns about the potential for increased tolerance [28]. Therefore, evaluating the susceptibility profiles of hospital-associated bacterial strains to chemical disinfectants is essential to guide the effective selection and use of disinfectants. Hence, we have assessed the efficiency of commercial chemical disinfectants under in-use and off-label conditions against twelve well-characterized ESKAPE pathogens collected from two major Romanian hospitals during 2019–2020. The bacterial strains were isolated from different sources, such as urine, blood, tracheal secretions, and sputum, and exhibited varying antibiotic resistance phenotypes, including extended beta-lactamase (ESBL) Enterobacterales, carbapenemase-resistant (CR) Enterobacterales, CR P. aeruginosa, CR A. baumannii, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium and methicillin-resistant S. aureus. These bacterial strains were genetically diverse and included clinically relevant MDR lineages, such as ST131-Ec17, ST101-Kpn13, ST258-Kpn159, ST2-Abc110, ST1-Sa10, ST612-Ef15, and ST203-Ef16 [24, 29–33].

The results showed that all three commercial disinfectants - product A (alcohol-based), product B (hydrogen peroxide-based) and product C (chlorine-based) - were effective at destroying 100% of the planktonic bacteria at the concentrations and contact times recommended by the manufacturers. Notably, the MBC values were substantially lower than the in-use concentrations. While the overall efficacy of the disinfectants was consistent across ESKAPE strains, marginal differences was observed with Product B. Specifically, the clinical isolate E. faecium VRE16 exhibited an increased MBC compared to the reference strain, with a 3-fold increase (P < 0.05). Conversely, both clinical P. aeruginosa strains showed significantly higher MBCs values to product B, at a 5-minute contact time, with a 4-fold increase compared to the type strain (P < 0.05). One possible explanation in these observations lies in species- and strain-specific differences in bacterial antioxidant defense systems, such as catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase activity, which can modulate susceptibility to oxidative stress. Additionally, differences in membrane permeability and efflux pump activity may also contribute to the observed heterogeneity in susceptibility [34].

These findings are in line with previous studies reporting microbial strains with elevated MICs or MBCs that nonetheless remain susceptible at in-use concentrations [14, 35–37]. A reduced contact time significantly affected the efficacy of all the chemical products. Product A was ineffective against 13 out of 16 tested bacterial strains when applied for 30 s under soiling conditions. While such short contact times may not fully reflect typical real-world applications, where disinfectants are often left on surfaces without neutralization, these findings offer valuable insight into the minimum exposure required for effective microbial inactivation. Short contact times appear most suitable for routine prophylactic surface disinfection in healthcare settings, where rapid turnover and frequent application are common. Therefore, understanding the lower limits of effective contact time remains important for optimizing disinfection protocols under practical conditions.

Although disinfection may be effective against bacteria in the planktonic state, a number of studies have demonstrated that certain chemical disinfectants currently in use in hospitals may not be effective against nosocomial pathogens when they are attached to surfaces or forming biofilms, failing to control this source of HAIs [38–42]. In the present study, the effects of Product C and Product A were more significant than those of Product B in reducing bacterial attachment. Product A and Product C significantly inhibited the attachment of bacteria on the plastic surface of the microtiter plate. Several other studies reported that sodium hypochlorite has a significant inhibitory effect on S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and E. faecalis biofilm development [42–47]. The proposed mechanisms of inhibition of bacterial biofilms by sodium hypochlorite include an increase in electrostatic repulsion between bacterial cells and the material surface because of its alkaline pH and the alteration of proteins in the biofilm matrix and of the major bacterial enzymes, thus irreversibly killing bacterial cells in biofilms [48]– [49]. Luther et al. [50] reported that ethanol and isopropyl alcohol exposure increases the biofilm formation of S. aureus and S. epidermidis at concentrations used in clinical settings. Significant differences in the efficacy of sodium hypochlorite and ethanol were observed against the biofilm and planktonic growth of S. aureus, the first of which demonstrated superior efficacy [46]. The results of the current studies regarding the efficacy of hydrogen peroxide against biofilms are inconsistent, some stating that it is ineffective [51, 52], while others showing that it appears to penetrate P. aeruginosa biofilms and detached them [53]. In our study, although statistically not significant from the untreated controls, product B exhibited anti-adhesion activity. Given that its active component is hydrogen peroxide, the observed anti-adhesive effect may be attributed to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS can disrupt bacterial surface structures and signalling pathways involved in initial adhesion, thereby inhibiting early stages of biofilm formation [54].

When wearing gloves, the gold standard for hand hygiene requires removing gloves, performing hand hygiene, and putting new gloves between WHO moments. However, studies have shown that decontaminating gloves with alcohol-based hand rubs during routine care is an effective alternative to glove replacement [55–58]. For instance, a randomized trial demonstrated that application of alcohol-based hand rubs to gloved hands significantly reduced microbial contamination [58]. In our study, Product A has eliminated bacteria from both latex and nitrile glove surfaces. This supports the use of alcohol-based glove disinfection during routine care to reduce microbial transmission. However, reduced concentrations or shortened contact times significantly compromised the alcohol-based disinfectant’s efficacy.

Additionally, we also showed that sublethal concentrations of disinfectants had varied effects on the phenotypic expression of soluble virulence factors. Product B and C significantly inhibited the production of proteases (P < 0.01) and phospholipases (P < 0.05), while the Product A had no measurable impact on the expression of proteases, lipases, phospholipases, or hemolysins. Supporting this, Korem et al. [59] reported only minor transcriptional changes in S. aureus exposed to 3% ethanol, primarily involving genes related to membrane lipid modification and ethanol metabolism, indicating mild cellular stress. Similarly, other studies have shown that sublethal concentrations of hydrogen peroxide and chlorine compounds can suppress the expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes [21]. These oxidizing agents exert their effects by damaging essential cellular components such as enzymes, proteins, and nucleic acids.

While our study focused on the efficacy of disinfectants at label-specified concentrations and contact times, as well as off-label use, it did not evaluate how environmental variables such as pH, temperature, and different types of organic load might affect efficacy. In real-world healthcare settings, monoculture biofilms are uncommon, and factors such as soil type, levels, and surface materials can vary significantly. Additionally, our experiments were conducted using polystyrene flat-bottom microtiter plates under static conditions, which may not accurately reflect the microbial behaviour on other surface types, such as stainless steel. Acknowledging these limitations, further research is warranted to explore the impact of additional factors, such as dry surface biofilms, and to evaluate disinfectant efficacy under more representative conditions relevant to healthcare environments.

Conclusions

In this study, we found variability in disinfectant efficacy among strains at label conditions. In addition, contact time was found to significantly affected the efficacy of the three tested disinfectants. These findings highlight the critical importance of following manufacturer guidelines, particularly with respect to recommended concentrations and contact times. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of the tested disinfectants inhibited initial early stages of biofilm formation and altered the expression of virulence markers. Further research is needed to examine the impact of disinfectants on both virulence markers expression and biofilm formation capacity to better understand the potential development of tolerance in nosocomial pathogens. Such investigations could provide valuable insights to inform the design of more effective disinfectant formulations and strengthen infection control strategies.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., M.C.C., M.M.M.; methodology, M.M.M., A.P., M.S., D.T., I.B., E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B., L.M., M.C.C.; A.P., M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.M.M., L.M., M.C.C., I.B., A.P; project administration, I.B, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Executive Agency for Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation Funding (UEFISCDI), grant number PN-III-P2-2.1-PED-2021-2115 (620 PED) and CNFIS-FDI-2025-F-0364 and the project Health Program entitled “Development of genomics research in Romania (ROGEN), Financing Contract no. 96006 / 17.12.2024, SMIS code – 324809.

Data availability

The NGS datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, BioProject PRJNA1153297 (Ec 2, Ec 17, Kpn 159, Abc 110, Abc 111, Sa 10, Sa 13358, Ps 1707, Ps 1696, Ef VRE 15, Ef VRE 16) and BioProject PRJNA579879 (Kpn13 - K. pneumoniae strain 36).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce JM. Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(2):50–4. 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces?? A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6: 130. 10.1186/1471-2334-6-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemaly RF, Simmons S, Dale C, Ghantoji SS, Rodriguez M, Gubb J, et al. The role of the healthcare environment in the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms: update on current best practices for containment. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2014;2(3–4):79–90. 10.1177/2049936114543287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dancer SJ. Controlling hospital-acquired infection: focus on the role of the environment and new technologies for decontamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;4(4):665–90. 10.1128/CMR.00020-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wißmann JE, Kirchhoff L, Brüggemann Y, Todt D, Steinmann J, Steinmann E. Persistence of pathogens on inanimate surfaces: a narrative review. Microorganisms. 2021;9: 343. 10.3390/microorganisms9020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moccia G, Motta O, Pironti C, Proto A, Capunzo M, De Caro F. An alternative approach for the decontamination of hospital settings. J Infect Public Health. 2022;13:2038–44. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takoi H, Fujita K, Hyodo H, Matsumoto M, Otani S, Gorai M, Mano Y, Saito Y, Seike M, Furuya N, Gemma A. Acinetobacter baumannii can be transferred from contaminated nitrile examination gloves to polypropylene plastic surfaces. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:1171–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chng KR, Li C, Bertrand D, et al. Cartography of opportunistic pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes in a tertiary hospital environment. Nat Med. 2020;26:941–51. 10.1038/s41591-020-0894-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.König P, Wilhelm A, Schaudinn C, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Widera M, Averhoff B. Müller V. The VBNC state: a funda-mental survival strategy of Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio. 2023;14:e02139–23. 10.1128/mbio.02139-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee AS, White E, Monahan LG, Jensen SO, Chan R, van Hal SJ. Defining the role of the environment in the emergence and persistence of VanA vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) in an intensive care unit: a molecular epidemiological study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(6):668–75. 10.1017/ice.2018.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qian W, Wang W, Zhang J, Liu M, Fu Y, Li M, Wang C. Equivalent effect of extracellular proteins and polysaccharides on biofilm formation by clinical isolates of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Biofouling. 2021;37(3):327–40. 10.1080/08927014.2021.1914021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang SR, Jung F, Tang HJ, Chen CH, Chen CC, Chou HY, Chuang YC. Desiccation and ethanol resistances of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii embedded in biofilm: the favourable antiseptic efficacy of combination chlorhex-idine gluconate and ethanol. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:770–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maillard JY. Impact of Benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride and Chloroxylenol on bacterial antimicrobial resistance. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;133(6):3322–46. 10.1111/jam.15739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo L, Wu Y, Yu T, Wang Y, Chen GQ, Tong X, et al. Evaluating method and potential risks of chlorine-resistant bacteria (CRB): a review. Water Res. 2020;188:116474. 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dijk HFG, Verbrugh HA. Ad hoc advisory committee on disinfectants of the health Council of the netherlands. Resisting disinfectants. Commun Med (Lond). 2022;2:6. 10.1038/s43856-021-00070-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bazaid AS, Forbes S, Humphreys GJ, Ledder RG, O’Cualain R, McBain AJ. Fatty acid supplementation reverses the small colony variant phenotype in triclosan-adapted Staphylococcus aureus: genetic, proteomic and phenotypic analyses. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3876. 10.1038/s41598-018-21925-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Condell O, Power KA, Händler K, Finn S, Sheridan A, Sergeant K, Renaut J, Burgess CM, Hinton JC, Nally JE, Fanning S. Comparative analysis of Salmonella susceptibility and tolerance to the biocide chlorhexidine identifies a complex cellular defense network. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:373. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balasubramanian AR, Vasudevan S, Shanmugam K, Lévesque CM, Solomon AP, Neelakantan P. Combinatorial effects of trans-cinnamaldehyde with fluoride and chlorhexidine on Streptococcus mutans. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;130(2):382–93. 10.1111/jam.14794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galice DM, Bonacorsi C, Gomes Soares VC, Gonçalves RMS, da Fonseca LM. Effect of subinhibitory concentration of chlorhexidine on Streptococcus agalactiae virulence factor expression. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28(2):143–6. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kastbjerg VG, Larsen MH, Gram L, Ingmer H. Influence of sublethal concentrations of common disinfectants on expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:303–9. 10.1128/AEM.00925-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EN 14885:2022. Chemical disinfectants and antiseptics - Application of European Standards for chemical disinfectants and antiseptic. 2022.

- 23.Coombs K, Rodriguez-Quijada C, Clevenger JO, Sauer-Budge AF. Current understanding of potential linkages between biocide tolerance and antibiotic cross-resistance. Microorganisms. 2023;11: 2000. 10.3390/microorganisms11082000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pidot SJ, Gao W, Buultjens AH, Monk IR, Guerillot R, Carter GP, Lee JYH, Lam MMC, Grayson ML, Ballard SA, Mahony AA, Grabsch EA, Kotsanas D, Korman TM, Coombs GW, Robinson JO, Silva A, Seemann T, Howden BP, Johnson PDR, Stinear TP. Increasing tolerance of hospital Enterococcus faecium to handwash alcohols. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar6115. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar6115. Gonçalves da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 32nd ed. CLSI Supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Institute; 2022.

- 26.Kawamura-Sato K, Wachino J, Kondo T, Ito H, Arakawa Y. Correlation between reduced susceptibility to disinfectants and multidrug resistance among clinical isolates of Acinetobacter species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(9):1975–83. 10.1093/jac/dkq227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepanović S, Vuković D, Hola V, Di Bonaventura G, Djukić S, Cirković I, Ruzicka F. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by Staphylococci. APMIS. 2007;602 115(8):600. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maillard JY. 2018. Resistance of Bacteria to Biocides. Microbiol Spectr. 6(2). 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0006-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lam MMC, Hamidian M. Examining the role of Acinetobacter baumannii plasmid types in disseminating antimicrobial resistance. Npj Antimicrob Resist. 2024. 10.1038/s44259-023-00019-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin MJ, Stribling W, Ong AC, Maybank R, Kwak YI, Rosado-Mendez JA, Preston LN, Lane KF, Julius M, Jones AR, Hinkle M, Waterman PE, Lesho EP, Lebreton F, Bennett JW, Mc Gann PT. A panel of diverse Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates for research and development. Microb Genom. 2023;9(5):mgen000967. 10.1099/mgen.0.000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forde BM, Roberts LW, Phan MD, et al. Population dynamics of an Escherichia coli ST131 lineage during recurrent urinary tract infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10:364. 10.1038/s41467-019-11571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Côrtes MF, Botelho AMN, Bandeira PT, Mouton W, Badiou C, Bes M, Lima NCB, Soares AER, Souza RC, Almeida LGP, Martins-Simoes P, Vasconcelos ATR, Nicolás MF, Laurent F, Planet PJ, Figueiredo AMS. Reductive evolution of virulence repertoire to drive the divergence between community- and hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of the ST1 lineage. Virulence. 2021;12(1):951–67. 10.1080/21505594.2021.1899616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Islam M, Sharon B, Abaragu A, Sistu H, Akins RL, Palmer K. Vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium from the Dallas, Texas, area is conferred predominantly on pRUM-like plasmids. mSphere. 2023;8: e00024–23. 10.1128/msphere.00024-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poole K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(9):2069–89. 10.1093/jac/dks196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vijayakumar R, Sandle T. A review on biocide reduced susceptibility due to plasmid-borne antiseptic resistance genes-special notes on pharmaceutical environmental isolates. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126(4):1011–22. 10.1111/jam.14118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stauf R, Todt D, Steinmann E, Rath PM, Gabriel H, Steinmann J, Brill FHH. In-vitro activity of active ingredients of disinfectants against drug-resistant fungi. J Hosp Infect. 2019;103(4):468–73. 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goroncy-Bermes P, Brill F, Brill H. Antimicrobial activity of wound antiseptics against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria. Wound Med. 2013;1:41–3. 10.1016/j.wndm.2013.05.004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maillard JY, Centeleghe I. 2023. How biofilm changes our understanding of cleaning and disinfection. 2023. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 12(1):95. 10.1186/s13756-023-01290-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Dettenkofer M, Block C. Hospital disinfection: efficacy and safety issues. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:320–5. 10.1097/01.qco.0000172701.75278.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simões M, Simões LC, Vieira MJ. A review of current and emergent biofilm control strategies. LWT. 2010;43:573–83. 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.12.008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bridier A, Briandet R, Thomas V, Dubois-Brissonnet F. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to disinfectants: a review. Biofouling. 2011;27:1017–32. 10.1080/08927014.2011.626899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otter JA, Vickery K, Walker JT, deLancey PE, Stoodley P, Goldenberg SD, Salkeld JAG, Chewins J, Yezli S, Edgeworth JD. Surface-attached cells, biofilms and biocide susceptibility: implications for hospital cleaning and disinfection. J Hosp Infect. 2015;89:16–27. 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Silva FC, Kimpara ET, Mancini MN, Balducci I, Jorge AO, Koga-Ito CY. Effectiveness of six different disinfectants on removing five microbial species and effects on the topographic characteristics of acrylic resin. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:627–33. 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith K, Hunter IS. Efficacy of common hospital biocides with biofilms of multidrug resistant clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:966–73. 10.1099/jmm.0.47668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez D, Ruas-Madiedo P, Martínez B, Rodríguez A, García P. Effective removal of Staphylococcal biofilms by the endolysin LysH5. PLoS One. 2014;9: e107307. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiwari S, Rajak S, Mondal DP, Biswas D. Sodium hypochlorite is more effective than 70% ethanol against biofilms of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:e37–42. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang C, Tao S, Yuan J, Li X. Effect of sodium hypochlorite on biofilm of Klebsiella pneumoniae with different drug resistance. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(8):922–8. 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lineback CB, Nkemngong CA, Wu ST, Li X, Teska PJ, Oliver HF. Hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite disinfectants are more effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms than quaternary ammonium compounds. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7: 154. 10.1186/s13756-018-0447-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fukuzaki S. Mechanisms of actions of sodium hypochlorite in cleaning and disinfection processes. Biocontrol Sci. 2006;11:147–57. 10.4265/bio.11.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luther MK, Bilida S, Mermel LA, LaPlante KL. Ethanol and isopropyl alcohol exposure increases biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(2):219–26. 10.1007/s40121-015-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tote K, Vanden Berghe D, Levecque S, Benere E, Maes L, Cos P. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants in a new resazurin microplate method for rapid efficacy testing of biocides. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:606–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart PS, Roe F, Rayner J, Elkins JG, Lewandowski Z, Ochsner UA, Hassett DJ. Effect of catalase on hydrogen peroxide penetration into Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:836–8. 10.1128/aem.66.2.836-838.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marchand P, Desrosiers D, Côté A, Touchette M. Comparative study on the efficacy of disinfectants against bacterial contamination caused by biofilm. Can J Infect Control. 2017;32:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lineback CB, Nkemngong CA, Wu ST, Li X, Teska PJ, Oliver HF. Hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite disinfectants are more effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms than quaternary ammonium compounds. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:154. 10.1186/s13756-018-0447-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogel A, Brouqui P, Boudjema S. Disinfection of gloved hands during routine care. New Microbes New Infect. 2021;3:41:100855. 10.1016/j.nmni.2021.100855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Birnbach DJ, Thiesen TC, McKenty NT, Rosen LF, Arheart KL, Fitzpatrick M, Everett-Thomas R. Targeted use of alcohol-based hand rub on gloves during task dense periods: one step closer to pathogen containment by anaesthesia providers in the operating room. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(6):1557–60. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thom KA, Rock C, Robinson GL, Reisinger HRS, Baloh J, Chasco E, Liang Y, Li S, Diekema DJ, Herwaldt LA, Johnson JK, Harris AD, Perencevich EN. Alcohol-based decontamination of gloved hands: a randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2024;45(4):467–73. 10.1017/ice.2023.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao P, Horvatin M, Niezgoda G, Weible R, Shaffer R. Effect of multiple alcohol-based hand rub applications on the tensile properties of thirteen brands of medical exam nitrile and latex gloves. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2016;13(12):905–14. 10.1080/15459624.2016.1191640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Korem M, Gov Y, Rosenberg M. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus following exposure to alcohol. Microb Pathog. 2010;48(2):74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NGS datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, BioProject PRJNA1153297 (Ec 2, Ec 17, Kpn 159, Abc 110, Abc 111, Sa 10, Sa 13358, Ps 1707, Ps 1696, Ef VRE 15, Ef VRE 16) and BioProject PRJNA579879 (Kpn13 - K. pneumoniae strain 36).