Abstract

Background

The oral cavity is a common site for fungal infections in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), yet reports on oral mycobiome alterations remain limited. This study aimed to analyze differences in mycobiome diversity and community composition in the saliva of PLWHA at different infection stages.

Methods

Non-stimulated whole saliva samples were collected from 63 HIV-infected/AIDS patients, who were divided into four groups based on the CDC staging criteria (stage 0, n = 10; stage 1, n = 13; stage 2, n = 24; stage 3, n = 16), as well as from 24 HIV-negative individuals. Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing was employed to analyze species diversity and community composition differences, and correlations at the genus level with CD4⁺ T cell counts and HIV blood viral load (BVL) were evaluated.

Results

At the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level, the alpha diversity of the mycobiome community in the HIV-positive groups exhibited a gradual decline as the disease progressed, with the lowest Shannon index in HIV stage 3 (p < 0.05 vs. other groups). At the phylum level, all groups were predominantly composed of Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota. At the genus level, Candida was the predominant genus in all groups, with its abundance increasing to varying degrees in HIV stages 1, 2, and 3 compared to the HIV-negative control group (HIV_neg), showing significant differences in stage 1 (p = 0.006 vs. HIV_neg), stage 2 (p < 0.05 vs. HIV_neg), and stage 3 (p < 0.001 vs. HIV_neg). The most pronounced increase was observed in stage 3, while non-dominant species were relatively reduced. Correlation analysis showed that Debaryomyces and Talaromyces were positively associated with CD4⁺ T cell counts. These genera may play a role in immune regulation during HIV progression and warrant further functional analysis. Whereas Penicillium showed a significant negative correlation with BVL, indicating its abundance may decrease with higher viral loads.

Conclusion

The oral fungal microecology undergoes dynamic changes with HIV progression. In stage 3, there appears to be a noticeable increase in Candida, accompanied by a relative decrease in other normally present non-dominant fungal species, potentially resulting in opportunistic fungal infections.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04285-w.

Keywords: PLWHA, Saliva, Mycobiome, CD4⁺ T cell count, Diversity

Background

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) remains a major global public health issue. According to estimates by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), by the end of 2024, there were approximately 40.8 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). That year, 1.3 million people became newly infected with HIV, and 31.6 million individuals were accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART). While ART has been effective in reducing morbidity and mortality among patients, some individuals still experience poor viral control due to various factors, leading to the development of a range of diseases [1–4]. Among these, opportunistic fungal infections continue to pose a significant concern for PLWHA [5].

The oral cavity is a common site for fungal infections in PLWHA, and the risk of infection increases gradually with the decline of immunity. The most common fungal infections include oral candidiasis and hairy leukoplakia [6, 7]. Among these, oral candidiasis can serve as an important clinical indicator for early detection of potential HIV infection by dentist [8, 9]. When the immune system is severely damaged (especially when the CD4⁺ T cell count is less than 200 cells/µL), the body can no longer effectively resist the invasion of various pathogens. In such cases, oral fungal infections can become very complicated, and other severe opportunistic infections, such as pneumocystis pneumonia, cryptococcal meningitis, histoplasmosis, and Malassezia infections, may also occur [5, 10]. Additionally, the increasing problem of antifungal drug resistance [11] complicates treatment, posing challenges in managing opportunistic infections in PLWHA. Some studies suggest that immunity compromised by HIV infection may lead to altered fungal composition, promoting the development of opportunistic fungal infections in HIV-infected individuals [10]. Therefore, monitoring the dynamic changes of fungal community composition, combined with clinical data, may provide some help for early warning and precise treatment of fungal infection in PLWHA.

Due to various limitations, most human mycobiome is nonculturable by culture-dependent methods. However, with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), our understanding of the mycobiome has greatly expanded [12]. Saliva, as an essential component of the oral environment, is an ultrafiltrate of blood. While the HIV viral load in saliva is low in HIV-infected individuals, the composition of microorganisms is diverse and complex [13, 14]. Alterations in salivary composition and function in HIV infection might play a key role in the dysbiosis of the oral microbiome [15–17]. Therefore, saliva can serve as an important medium for exploring oral microbiome, and there is no existing report on dynamic monitoring of salivary mycobiome changes at different stages of PLWHA. This study applied internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing to analyze the characterization and variation of salivary mycobiome at different stages of HIV infection course.

Materials and methods

Study participants

The study included 63 participants from the study cohort of HIV infected people in Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University. Participants were aged 18 to 60 years and had not started ART. Inclusion criteria required the absence of untreated caries, oral abscess, or significant tooth loss (≥ 8 missing teeth). Participants also had no history of systemic diseases, use of immunosuppressants or antibiotics within the past 3 months, or other major oral health issues.

According to the staging criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for monitoring cases [18], stage 0 group (n = 10), stage 1 group (n = 13), stage 2 group (n = 24), stage 3 group (n = 16) were included. Stage 0 is the early stage of HIV infection, i.e., seroconversion within 6 months or indeterminate results by western blotting; and stages 1, 2, and 3 are based on CD4⁺ T cell counts of greater than or equal to 500,200–499, and less than 200 cells/µL or opportunistic infections, respectively. Simultaneously, 24 HIV-negative subjects (control group) were included, matched by gender, age, and ethnicity. All of them were volunteers from Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University. The details of all subjects shown in Table 1. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing YouAn Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. JYKL- [2017]−30 and No. JYKL- [2022]−39).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in untreated PLWHA and control groups

| Groups | HIV_0 (n=10) |

HIV_1 (n=13) |

HIV_2 (n=24) |

HIV_3 (n=16) |

HIV_neg (n=24) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.70±8.58 | 26.54±4.83 | 31.04±9.12 | 34.88±12.15 | 32.33±7.483 | 0.157 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||

| Male | 10(100.00) | 13(100.00) | 24(100.00) | 16(100.00) | 24(100.00) | NA |

| Female | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | NA |

| Mucosal health | 10(100.00) | 13(100.00) | 24(100.00) | 13(81.25) | 24(100.00) | NA |

| Oral candidiasis | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 3(18.75) | 0(0.00) | NA |

| CD4+ T cell count, | ||||||

| cells/μL | 424.95±180.83 | 614.36±82.28 | 351.30±94.59 | 107.46±83.87 | NA | 0.000 |

| BVL | 87695.90±149661.64 | 25765.69±42248.73 | 196537.38±620729.47 | 269168.69±328645.19 | NA | 0.430 |

Abbreviations: HIV_0 = HIV stage 0 group, HIV_1 = HIV stage 1 group, HIV_2 = HIV stage 2 group, HIV_3 = HIV stage 3 group, HIV_neg = HIV-negative control group; BVL = blood viral load; NA: Not available. Data were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Sample collection

The participants were instructed to collect non-stimulated saliva from 10:00 to 13:00 and refrain from eating, drinking, or oral hygiene procedures for at least 2 h before collection. We asked the participants to spit into a 50mL sterile tube, and we then placed the tube on ice in a polystyrene plastic box after collecting approximately 5 mL saliva. Samples were delivered to the laboratory within 1 h and stored at − 80℃ until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and sequencing

Total genomic DNA of microbial communities was extracted using the FastPure Stool DNA Isolation Kit (MJYH, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fungal-specific primers targeting the ITS1F-ITS2R region were selected for PCR amplification: Forward primer: ITS1F (5’-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3’);Reverse primer: ITS2R (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’). Purified PCR products were then used to construct sequencing libraries with the NEXTFLEX Rapid DNA-Seq Kit (Bioo Scientific, Austin, Texas, USA). Finally, paired-end sequencing (PE300) was performed on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform.

Statistical analysis

Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering of samples was performed using Uparse (version 7.0.1090, http://drive5.com/uparse/). Representative sequences of OTUs at 97% similarity were taxonomically classified using the RDP Classifier Bayesian algorithm, with community composition analyzed at each taxonomic level. Alpha diversity indices (Sobs index and Shannon index) were calculated using mothur software (version 1.30.2; http://www.mothur.org/wiki/Calculators) [19], and intergroup differences in alpha diversity were assessed via Kruskal-Wallis H test. Beta diversity was evaluated through principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distances to examine microbial community structural similarities. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were employed to test significant differences in microbial community structure between sample groups. Genera with Spearman correlation coefficients |r| >0.5 and p < 0.05 were considered significantly associated with clinical indicators and selected for correlation heatmap analysis [20].

Results

Taxonomy analysis

Salivary mycobiome diversity analysis of 87 non-stimulated saliva samples was conducted using the Illumina NextSeq sequencing platform targeting the 18 S rRNA ITS gene. A total of 6,730,835 high-quality sequences were obtained, with an average of 77,365.92 sequences per sample and an average read length of 211.52 bp. Clustering these sequences resulted in 954 OTUs, yielding taxonomic classifications spanning 11 phyla, 36 classes, 87 orders, 199 families, 349 genera, and 505 species.

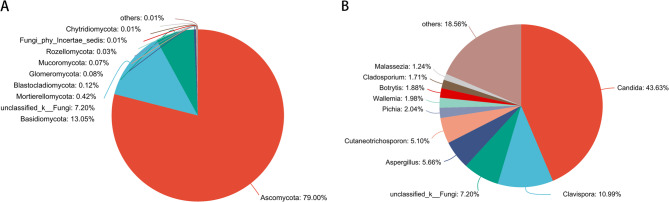

Community composition of the salivary mycobiome was predominantly represented by five phyla: Ascomycota (79.00%), Basidiomycota (13.05%), Mortierellomycota (0.42%), Blastocladiomycota (0.12%), and Glomeromycota (0.08%). At the genus level, the dominant taxa included Candida (43.63%), Clavispora (10.99%), Aspergillus (5.66%), Cutaneotrichosporon (5.10%), and Pichia (2.04%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Community analysis pieplot on phylum (A) and Genus level (B)

Alpha and beta diversity analyses of the salivary mycobiome

Alpha diversity (Fig. 2A and 2B) analysis at the OTU level showed that both the Sobs index and Shannon index exhibited a transient increasing trend in salivary mycobiome in the early stage of HIV infection (HIV stage 0) compared to the HIV-negative control group, and their index values showed a gradual decreasing trend with the development of HIV infection course. The Sobs index showed the lowest values in HIV stage 3, with statistically significant differences compared to HIV stage 0 (p<0.05 vs. stage 3) and stage 1 (p<0.05 vs. stage 3). Similarly, the Shannon index was lowest in HIV stage 3, with statistically significant differences when compared to all other groups (stage 0, p < 0.001; stages 1, 2, and HIV_neg, p < 0.05; all comparisons vs. stage 3)

Fig. 2.

Alpha and beta diversity analyses of the salivary mycobiome among the five groups HIV stage 0 (red), HIV stage 1 (blue), HIV stage 2 (green), HIV stage 3 (dark blue) and HIV-negative control (orange). *0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, **0.001 < p ≤ 0.01. *** p < 0.001. The Sobs index (A) and Shannon index (B) indicate richness and diversity in alpha-diversity at the OTU level, with statistical comparisons conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis H test. C Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and Anosim analysis revealed the differences in the salivary mycobiome among the five groups

Further analysis using PCoA in the Beta diversity analysis (Fig. 2C) revealed that the community composition of the salivary mycobiome in the HIV-negative control group was more similar to those in HIV stage 0. From HIV stages 1 to 3, there was noticeable separation along PC1, and as the disease progressed, the community composition showed increasing dispersion, suggesting dynamic changes in the mycobiome

The species composition of the salivary mycobiome

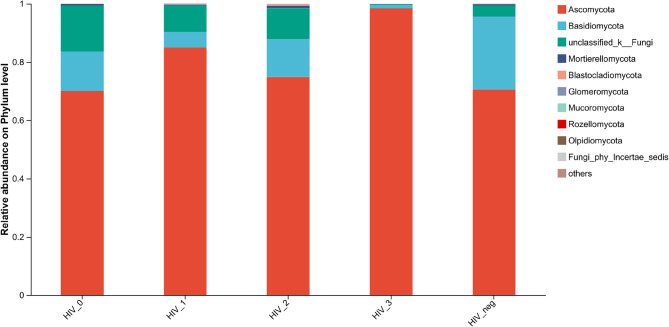

Comparison analysis of the salivary mycobiome at the phylum level among five groups

At the phylum level, distinct species compositions were observed between HIV-positive groups and the HIV-negative control group (Fig. 3). The top three dominant phyla in each group are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Notably, in HIV stage 3, only two phyla exhibited abundances exceeding 0.01%, which are listed accordingly.

Fig. 3.

Community barplot analysis of the salivary mycobiome at the phylum level among the five groups

Mycobiome communities across all groups were predominantly composed of Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota. Compared to the HIV-negative controls, Ascomycota reached its highest relative abundance in HIV stage 3 (98.42%), showing statistically significant differences (p < 0.001 vs. HIV_neg). For Basidiomycota, a significant decrease was observed in HIV stages 1–3 compared to controls (stage 1, p = 0.005; stage 2, p = 0.023; stage 3, p < 0.001; all comparisons vs. HIV_neg), except for HIV stage 0 (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Comparative analysis at the phylum level between HIV-positive groups and the HIV-negative control group (A), (B), and (C) represent comparisons of HIV stages 1, 2, and 3, respectively, with the HIV-negative control group. All pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test

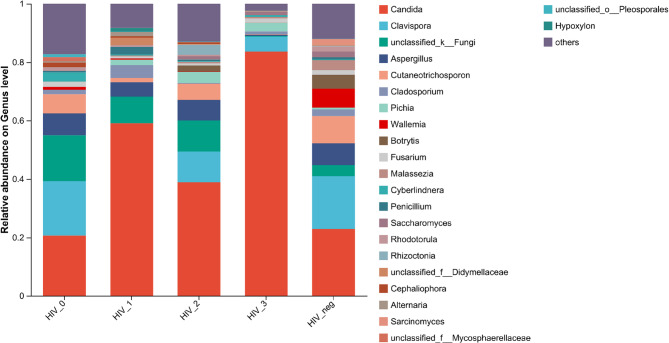

Comparison analysis of the salivary mycobiome at the Genus level among five groups

At the genus level, species composition also varied significantly between HIV-positive groups and the HIV-negative controls (Fig. 5), with the top five dominant genera Listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 5.

Community barplot analysis of the salivary mycobiome at the genus level among the five groups

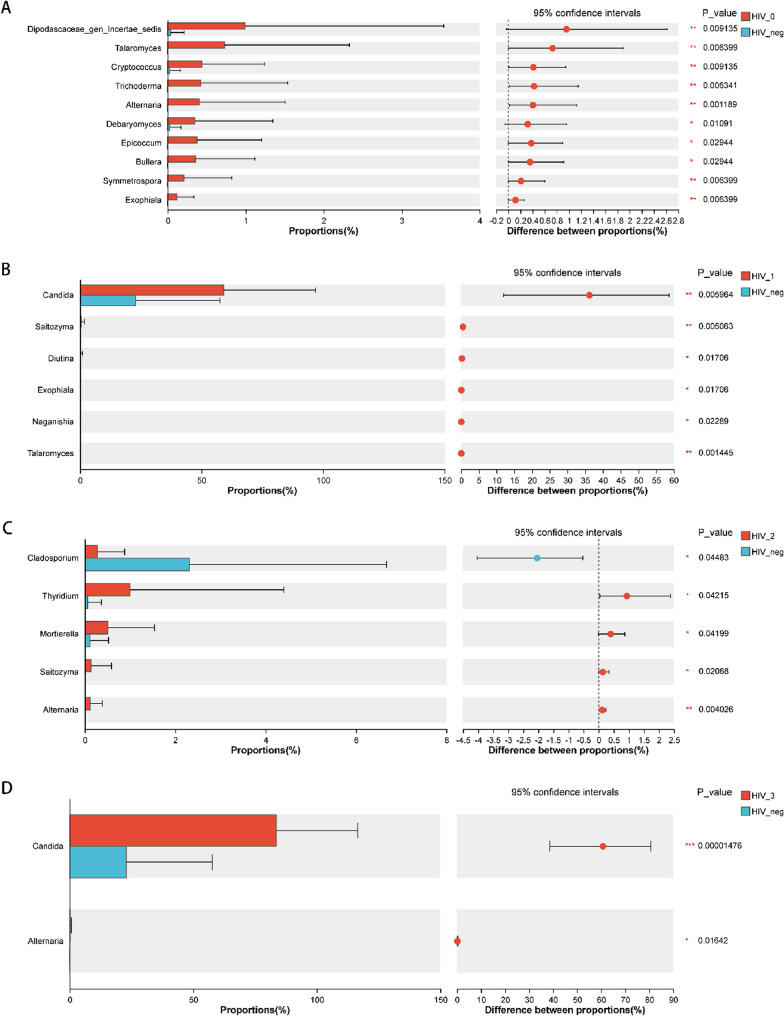

Pairwise comparisons between the HIV-negative control group and HIV stages 0–3 revealed statistically significant differences in non-dominant genera in HIV stages 0–2, particularly most pronounced in HIV stage 0. Among dominant genera, Candida consistently ranked first across all groups. Compared to controls, Candida abundance slightly decreased in HIV stage 0 but increased to varying degrees in HIV stages 1–3, with significant differences observed in stage 1 (p = 0.006 vs. HIV_neg) and stage 3 (p < 0.001 vs. HIV_neg) (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Comparative analysis at the genus level between HIV-positive groups and the HIV-negative control group (A), (B), (C), and (D) represent comparisons of HIV stages 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively, with the HIV-negative control group. All pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test

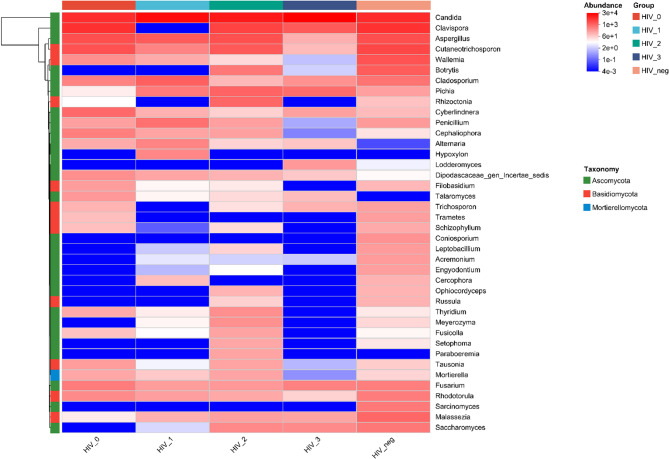

Heatmap of Genus-Level Community Composition

To further explore compositional similarities and differences, a heatmap was generated for the top 40 genera based on total abundance (Fig. 7). The heatmap demonstrated that Candida exhibited the highest abundance across all groups, while non-dominant genera showed generally lower relative abundance in HIV stage 3. Notably, Alternaria and Talaromyces were present at low abundance in HIV-negative controls and showed high abundance after HIV infection, but their levels remained relatively stable during disease progression. Conversely, Coniosporium and Sarcinomyces were abundant in controls but declined post-infection. Additionally, Wallemia and Rhodotorula exhibited progressive reductions in abundance as HIV disease advanced

Fig. 7.

Heatmap of relative abundance of species at the genus level Genera are color-coded by relative abundance; blue indicates low and red indicates high presence across groups

Correlation Analysis Between Salivary Communities and CD4⁺ T cell count/BVL

Correlation analysis of the top 50 genera revealed that Debaryomyces and Talaromyces showed positive correlations with CD4⁺ T cell counts (p < 0.05). In contrast, Penicillium was negatively correlated with blood viral load (BVL) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis of the salivary mycobiome community with CD4⁺ T cells and BVL at the genus level

The diagram shows genera with Spearman correlation coefficients |r| > 0.5 and p < 0.05, blue represents negative correlation, and red represents positive correlation, *0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, **0.001 < p ≤ 0.01. ***p < 0.001

Discussion

The oral microbiome is one of the most significant and complex microbial communities in the human body, and it represents one of the five key areas of focus in the Human Microbiome Project (along with the nasal cavity, vagina, gut, and skin) [21]. The mycobiome is an important component of the oral microbiome, yet it has been far less studied compared to bacteria. Published studies have shown that research on the oral mycobiome of HIV-infected individuals is relatively rare, with inconsistent findings [22–27]. Furthermore, these studies did not conduct further staging of HIV-infected individuals. This study is the first to use ITS sequencing to analyze the diversity of the salivary mycobiome in PLWHA at different stages.

Our study showed that alpha diversity analysis at the OTU level revealed a transient increase in the salivary mycobiome during the early stage of HIV infection (HIV stage 0) compared to the HIV-negative control group. However, as the HIV infection progressed, the index values gradually decreased, with the lowest species richness and evenness observed in HIV stage 3. A similar study by Annavajhala MK et al. [24] showed that patients with a history of AIDS had significantly lower subgingival plaque fungal alpha diversity. In contrast, Chang et al. [25] observed that the diversity and richness of salivary mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals were higher than in healthy controls. After ART, the diversity and richness of salivary mycobiome in HIV-infected patients were reduced significantly. Our study primarily highlights the dynamic changes in the salivary mycobiome following the HIV infection course. In the early stage (HIV stage 0), alpha diversity showed a slight increase, though no significant difference was observed compared to the HIV-negative control group. Additionally, several non-dominant fungal genera exhibited significantly increased abundance. A massive depletion of CD4⁺ T lymphocytes has been described in early and acute HIV infection, leading to an imbalance between the human microbiome and immune responses [28]; however, most of these findings have focused on the gut microbiota. Moreover, changes in the gut fungal community and its products have been associated with intestinal mucosal barrier damage, bacterial translocation, immune activation, persistent inflammation, and disease progression [29–31]. Our study provides preliminary evidence of early HIV infection-related alterations in the oral fungal community. This may be due to the maintenance of humoral and cellular immunity, as well as innate immune functions in the oral mucosa during this period [32]. Meanwhile, the adaptive immune response is activated, which may partially suppress viral replication [33, 34], potentially leading to a transient increase in fungal diversity. However, as the disease progresses to HIV stage 3, the significant reduction in CD4⁺ T cell counts and the disruption of the oral immune barrier [16] may lead to a severe imbalance in the oral fungal community.

Regarding species composition, our study found that at the phylum level, all groups were dominated by Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota. At the genus level, the dominant species differed significantly between HIV-negative controls and HIV-positive groups. These changes likely reflect immunological dysregulation, particularly due to declining CD4⁺ T cell counts, which weaken mucosal immunity and allow for dominance shifts in the fungal microbiome. In 2014, Mukherjee PK et al. [22] employed pyrosequencing for the first time to characterize the oral salivary mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals. They observed that in the HIV-infected group, the most common fungal genera were Candida, Epicoccum, and Alternaria, with detection rates of 92%, 33%, and 25%, whereas in the HIV-uninfected group, the predominant genera were Candida, Pichia, and Fusarium, with detection rates of 58%, 33%, and 33%, respectively. They also noted that C. albicans was the most common (58% in uninfected and 83% in HIV-infected participants). Fidel PL et al. [26] conducted ITS2 sequencing on oral rinse samples from 149 HIV-positive and 88 HIV-negative subjects, finding that the oral fungal community tended to be dominated by species of Candida, Saccharomyces, and Malassezia. Chang S et al. [25] demonstrated that Candida, Mortierella, Malassezia, Simplicillium, and Penicillium were significantly enriched in the HIV-infected group, but markedly reduced following ART. These findings indicate that there is currently no consensus on the core oral mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals, possibly due to factors such as sample type, disease stage, geographic region, and diet. Nevertheless, the aforementioned studies and other similar investigations [22, 23] consistently show that Candida predominates among the detectable fungal genera.

In the present study, Candida was also found to be the predominant genus across all groups. As shown in Fig. 6, compared with the HIV-negative control group, Candida abundance increased to varying degrees during HIV stages 1–3, with the most pronounced increase observed in HIV stage 3 (83.65%). In contrast, other non-dominant fungal species relatively decreased in stage 3. Although three cases of oral candidiasis were included in the HIV stage 3 group (Table 1), we did not exclude these samples, primarily because oral candidiasis (OC) is one of the most common oral mucosal infections among patients with HIV/AIDS [35]. The reported prevalence of Candida albicans in this population ranges from 0.9 to 83% [1]. Therefore, including these cases more closely aligns with clinical reality. Moreover, the analysis of microbial composition showed no statistically significant differences at either the phylum or genus levels, including Candida among the top 40 most abundant genera, between participants with and without oral candidiasis in the HIV stage 3 group (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). Based on these findings, we believe that the increased abundance of Candida observed in stage 3 is unlikely to be driven solely by these three individuals but rather reflects a broader fungal dysbiosis associated with advanced immunosuppression. Overall, stage 3 exhibited a noticeable decline in alpha diversity and the fewest species, with an apparent increase in the relative abundance of Candida and a reduction or lower presence of several other non-dominant fungal species. This finding suggests severe dysbiosis and high susceptibility to opportunistic oral candidiasis, a common complication in advanced HIV infection characterized by Candida overgrowth due to compromised host defenses. Previous research has shown that the pathogenicity of candidiasis is primarily mediated through biofilm formation, the yeast-to-hyphae transition, and the secretion of proteases and phospholipases, which damage host tissues, allow evasion of immune surveillance, and promote adhesion to host cells via specific adhesins—thereby enhancing its colonization and invasive capabilities and potentially leading to severe fungal infections [36, 37].

Overall, current studies on oral mycobiome have largely been confined to changes in the abundance and detection rates among different fungal genera. Some fungal genera are difficult to verify using culture-based methods, and there has been little exploration of their underlying mechanisms. However, this accumulating evidence suggests that oral microbiota may be similar to gut microbiota, and HIV infection may also promote the translocation of oral microbes, triggering systemic immune activation and chronic inflammation [24, 28, 38–41]. Furthermore, the substantial loss of CD4⁺ T cells may lead to a failure of antifungal immunity, thereby increasing the risk of opportunistic fungal infections [42].

Moreover, our genus-level community composition heatmap revealed some distinctive genera. Alternaria and Talaromyces exhibited low abundance in the HIV-negative control group, but their abundance was observed to increase following HIV infection, suggesting that these genera may be detected at any stage of HIV infection. In contrast, Coniosporium and Sarcinomyces showed reduced abundance after HIV infection. CD4⁺ T cells and BVL are important indicators for assessing patient condition, predicting clinical progression, and evaluating the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy [43]. Our correlation analyses further revealed that Debaryomyces and Talaromyces were moderately positively correlated with CD4⁺ T cells, whereas Penicillium was negatively correlated with BVL, indicating that certain oral fungal microbiota in HIV-infected individuals may be influenced by CD4⁺ T cell counts and BVL.

This study also has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, it would be more convincing to collect samples from the same HIV-positive individual at different stages of infection; however, obtaining such complete samples in practice is prohibitively difficult. Moreover, our study lacked an analysis of variables such as participants’ dietary habits and oral hygiene, which have shown inconsistent associations with the composition of the oral mycobiome in previous research [26, 44, 45]. Therefore, future research should involve larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and the inclusion of a broader range of variables. Additionally, the continued development and refinement of fungal ribosomal databases are essential to more comprehensively characterize the salivary mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals.

Conclusions

This study preliminarily analyzed the diversity and compositional differences of the salivary mycobiome communities in ART-naïve PLWHA at different stages of infection by conducting alpha diversity, beta diversity, and intergroup comparisons at both the phylum and genus levels. It was found that HIV stage 3 exhibited a significant reduction in alpha diversity, and the dominant species at the phylum and genus levels were identified across different groups. At the phylum level, all groups were dominated by Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota. At the genus level, Candida was the predominant genus in all groups and a distinct increase in HIV stage 3, while non-dominant species were reduced. These findings suggest the potential utility of salivary mycobiome profiling as a non-invasive biomarker for HIV progression and may guide future development of diagnostic or prophylactic strategies against oral fungal infections.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Weizhuo Zhang and Ye Xiao (Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd.) for assistance in the development, implementation, and analysis of this study.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- UNAIDS

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- PLWHA

People living with HIV/AIDS

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- ITS

Internal transcribed spacer

- OTU

Operational taxonomic unit

- BVL

Blood viral load

Authors' contributions

LL contributed to conception and design, data acquisition and analysis and drafted the manuscript. WD, YW, JC and ZF collected the data. YY, YL, XS, SW, and XW contributed to data analysis. QJ, and YG contributed to conception and design, data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing Institute of Hepatology Reform and Development Project-Beijing Municipal Health Commission (2025Y-KF-Q07), the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubation Programme (PX2022069).

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive database (PRJNA1245252).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing YouAn Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. JYKL- [2017]-30 and No. JYKL- [2022]-39), and was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration on medical research involving human subjects. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ying Guo, Email: crystalsean@126.com.

Qingsong Jiang, Email: qsjiang@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Patil S, Majumdar B, Sarode SC, Sarode GS, Awan KH. Oropharyngeal candidosis in HIV-Infected Patients-An update. Front Microbiol. 2018;9. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00980. :980. Published 2018 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Pólvora TLS, Nobre ÁVV, Tirapelli C, et al. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection and chronic periodontitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14(4):315–27. 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1459571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goedert JJ, Hosgood HD, Biggar RJ, Strickler HD, Rabkin CS. Screening for cancer in persons living with HIV infection. Trends Cancer. 2016;2(8):416–28. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajpai S, Pazare AR. Oral manifestations of HIV. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1(1):1–5. 10.4103/0976-237X.62510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limper AH, Adenis A, Le T, Harrison TS. Fungal infections in HIV/AIDS. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):e334–43. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moosazadeh M, Shafaroudi AM, Gorji NE, Barzegari S, Nasiri P. Prevalence of oral lesions in patients with AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published correction appears in Evid Based Dent. 2022;23(1):5. 10.1038/s41432-022-0234-2.]. Evid Based Dent. Published online November 17, 2021. doi:10.1038/s41432-021-0209-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Braz-Silva PH, Santos RT, Schussel JL, Gallottini M. Oral hairy leukoplakia diagnosis by Epstein-Barr virus in situ hybridization in liquid-based cytology. Cytopathology. 2014;25(1):21–6. 10.1111/cyt.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekatkar M, Kheur S, Gupta AA, et al. Oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients under highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Mon. 2021;67(9): 101169. 10.1016/j.disamonth.2021.101169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suryana K, Suharsono H, Antara IGPJ. Factors associated with oral candidiasis in people living with HIV/AIDS: a case control study. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2020;33–9. 10.2147/HIV.S236304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong-James D, Meintjes G, Brown GD. A neglected epidemic: fungal infections in HIV/AIDS. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(3):120–7. 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidya KM, Rao UK, Nittayananta W, Liu H, Owotade FJ. Oral mycoses and other opportunistic infections in HIV: therapy and emerging problems - a workshop report. Oral Dis. 2016;22(Suppl 1):158–65. 10.1111/odi.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui L, Morris A, Ghedin E. The human mycobiome in health and disease. Genome Med. 2013;5(7):63. 10.1186/gm467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira SM, Gonçalves LS, Torres SR, Nogueira SA, Meiller TF. Lactoferrin levels in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva of HIV-infected patients with chronic periodontitis. J Investig Clin Dent. 2015;6(1):16–24. 10.1111/jicd.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khurshid Z, Zohaib S, Najeeb S, Zafar MS, Slowey PD, Almas K. Human saliva collection devices for proteomics: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6): 846. 10.3390/ijms17060846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belstrøm D. The salivary microbiota in health and disease. J Oral Microbiol. 2020;12(1): 1723975. 10.1080/20002297.2020.1723975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heron SE, Elahi S. HIV infection and compromised mucosal immunity: oral manifestations and systemic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2017. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00241. 8:241. Published 2017 Mar 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nizamuddin I, Koulen P, McArthur CP. Contribution of HIV infection, AIDS, and antiretroviral therapy to exocrine pathogenesis in salivary and lacrimal glands. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9): 2747. 10.3390/ijms19092747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection–United states, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR–03):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537–41. 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barberán A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, Fierer N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 2012;6(2):343–51. 10.1038/ismej.2011.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human Microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449(7164):804–10. 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Retuerto M, et al. Oral mycobiome analysis of HIV-infected patients: identification of Pichia as an antagonist of opportunistic fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(3): e1003996. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Retuerto M, Tatsuoka C, Ghannoum MA, McComsey GA. Dysbiosis in the oral bacterial and fungal microbiome of HIV-infected subjects is associated with clinical and immunologic variables of HIV infection. PLoS One. 2018;13(7): e0200285. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annavajhala MK, Khan SD, Sullivan SB, et al. Oral and gut microbial diversity and immune regulation in patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy. mSphere. 2020;5(1):e00798–19. 10.1128/mSphere.00798-19. Published 2020 Feb 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang S, Guo H, Li J, et al. Comparative analysis of salivary mycobiome diversity in human immunodeficiency Virus-infected patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11: 781246. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.781246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fidel PL Jr, Thompson ZA, Lilly EA et al. Effect of HIV/HAART and Other Clinical Variables on the Oral Mycobiome Using Multivariate Analyses. mBio. 2021;12(2): e00294-21. Published 2021 Mar 23. 10.1128/mBio.00294-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Beall CJ, Lilly EA, Granada C, et al. Independent effects of HIV and antiretroviral therapy on the oral microbiome identified by multivariate analyses. mBio. 2023;14(3):e0040923. 10.1128/mbio.00409-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Su B, He QS, Wu H, Zhang T. Alterations in the oral microbiome in HIV infection: causes, effects and potential interventions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(23):2788–98. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehraj V, Ramendra R, Isnard S et al. Circulating (1→3)-β-D-glucan Is Associated With Immune Activation During Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(6):1265. 10.1093/cid/ciaa058.]. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(2):232–241.doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Yin Y, Tuohutaerbieke M, Feng C, et al. Characterization of the intestinal fungal microbiome in HIV and HCV mono-infected or co-infected patients. Viruses. 2022;14(8): 1811. 10.3390/v14081811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolling T, Hohl TM, Zhai B. Minority report: the intestinal mycobiota in systemic infections. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020;56:1–6. 10.1016/j.mib.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lü FX, Jacobson RS. Oral mucosal immunity and HIV/SIV infection. J Dent Res. 2007;86(3):216–26. 10.1177/154405910708600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robb ML, Ananworanich J. Lessons from acute HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(6):555–60. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fenwick C, Joo V, Jacquier P, et al. T-cell exhaustion in HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 2019;292(1):149–63. 10.1111/imr.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erfaninejad M, Zarei Mahmoudabadi A, Maraghi E, Hashemzadeh M, Fatahinia M. Epidemiology, prevalence, and associated factors of oral candidiasis in HIV patients from Southwest Iran in post-highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:983348. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.983348. Published 2022 Sep 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H, Hong T, Jiang Y, Whiteway M, Zhang S. Candidiasis. From cutaneous to systemic, new perspectives of potential targets and therapeutic strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023;199: 114960. 10.1016/j.addr.2023.114960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Černáková L, Rodrigues CF. Microbial interactions and immunity response in oral Candida species. Future Microbiol. 2020;15:1653–77. 10.2217/fmb-2020-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groenewegen H, Bierman WFW, Delli K, et al. Severe periodontitis is more common in HIV-infected patients. J Infect. 2019;78(3):171–7. 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tugizov SM, Herrera R, Chin-Hong P, et al. HIV-associated disruption of mucosal epithelium facilitates paracellular penetration by human papillomavirus. Virology. 2013;446(1–2):378–88. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acheampong EA, Parveen Z, Muthoga LW, et al. Molecular interactions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with primary human oral keratinocytes. J Virol. 2005;79(13):8440–53. 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8440-8453.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu RQ, Zhang DF, Tu E, Chen QM, Chen W. The mucosal immune system in the oral cavity-an orchestra of T cell diversity. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6(3):125–32. 10.1038/ijos.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Yang X, Moog C, Wu H, Su B, Zhang T. Neglected mycobiome in HIV infection: alterations, common fungal diseases and antifungal immunity. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 1015775. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1015775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blair HA. Ibalizumab. A review in multidrug-resistant HIV-1 infection. Drugs. 2020;80(2):189–96. 10.1007/s40265-020-01258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belvoncikova P, Splichalova P, Videnska P, Gardlik R. The human mycobiome: colonization, composition and the role in health and disease. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8(10):1046. 10.3390/jof8101046. Published 2022 Oct 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung MK, Chan JYK, Wong MCS, et al. Determinants and interactions of oral bacterial and fungal microbiota in healthy Chinese adults. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1):e0241021. 10.1128/spectrum.02410-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive database (PRJNA1245252).